1. Introduction

The health and wellbeing belong to major society priorities. According to surveys conducted by the European Agency for Occupational Safety and Health at Work (EU OSHA), approximately 3 out of 5 workers complain of MSDs (musculoskeletal disorders) [

1]. Statistics on the incidence of occupational diseases in Slovakia over the last 20 years show a fluctuating trend. However, the latest statistics available at the time of publication, from 2021, published by the National Centre for Health Information [

2], show an increasing trend in the occurrence of WMSDs (work-related musculoskeletal disorders), therefore attention should be paid to their elimination. The overall increase in the number of occupational diseases, compared to 2020, was 169 cases, with a total of 423 cases of occupational diseases occurring in 2021, with being the most affected workers in motor vehicle manufacturing, metal structures excluding machinery and equipment, and health care [

2]. The most common problems include pain in the neck, upper limbs, and lower back [

3]. Pain in the lower limbs is rare, which is probably due to their natural adaptation to the load, as their primary function is walking and standing, in which they bear the weight of the body [

4].

The aging of the population raises many issues and provides many opportunities. It intensifies the requirement for long-term care, healthcare, and a better-skilled workforce, and increases the demand for age-friendly environments. The most prominent studies suggest policies and practices that support life-long learning, a workforce that comprises both younger and older workers, and gradual retirement [

5]. Most of the recorded cases of occupational diseases occurred in the age group of 50-59 years, i.e., in employees with a high probability of tissue wear and tear due to long-term loading, which again points to the necessity of preventing such diseases by proper limitation of workload and work movements and positions and application of ergonomic principles in practice [

2,

6].

Ergonomics design focuses on the actual activity of operators. The methodology described in this European Standard EN 16710-2 [

7] therefore increases the effectiveness and efficiency of the machinery or system being designed; improves human working conditions; and reduces adverse effects on health, safety and performance. Applying this will raise productivity, improve work quality, reduce technical support, maintenance and training needs, and will enhance user/operator satisfaction. The risk-assessment model in document EN ISO 11228-1 [

8] allows the estimation of the risk associated with a manual material handling task. It takes into consideration the hazards (unfavourable conditions) related to manual handling tasks and the time spent performing them. The European Standard STN EN 1005-4+A1 [

9] „Machine safety. Human physical performance. Part 4: Assessment of working postures and movements when working on machinery“ provides guidance on the assessment of potential health risks associated with work only the working positions and movements of machinery, i.e., during its assembly, installation, operation, adjustment, maintenance, cleaning, repair, transport and dismantling, which must be taken into account when designing machinery or its components. This European Standard specifies the requirements for positions and movements in which there is no or minimal external force. These requirements are intended to reduce health risks for almost all healthy adult workers. Similarly, with the Industry 4.0 adaptation, workplace design approach requires risk assessment that emphasizes the interactions between the operator, the robot and, the work environment. Guidelines for the design of safe human-robot collaborative assembly are being developed and classified [

10].

The assessment of physical exposure should include three dimensions of load: level (amplitude), repetition and duration [

3]. Available methods usually focus on the assessment of working postures, while other factors as repetition and duration of postures, or muscle strength are less frequently considered [

11]. In practice, a number of methods are used to assess workload, which are selected according to the nature of the activity being performed and the relevant body part. The methods have been categorized under three main headings: (1) self-reports from workers; (2) observational methods: simpler techniques developed for systematically recording workplace exposure and advanced techniques developed for the assessment of postural variation for highly dynamic activities; (3) direct measurements using monitoring instruments that rely on sensors attached directly to the subject for the measurement of exposure variables at work [

12]. In general, REBA (Rapid Entire Body Assessment) and RULA (Rapid Upper Limb Assessment) methods are often used, as they are relatively easy, fast and do not stress the workers in any way in the work cycle and movement habits associated with the work [

13,

14]. Many of these methods have been designed based on long-term research, others have been built on the laws of biomechanics and ergonomics, and some have been developed by modifying already existing methods to obtain better sensitivity of the assessment methodology or to adapt the methodology to a specific type of work (e.g., working with loads) [

12,

15,

16].

The REBA method is mainly used for the analysis of forced postures, postures of the upper limbs (arm, forearm, wrist), trunk, neck and lower extremities. In addition, it discriminates the type of grip and muscle activity performed. It identifies five levels of risk, from negligible to very high [

17]. The RULA [

18] is a well-known method for the evaluation of the ergonomic risk as, in addition to assessing the neck, trunk, and upper limb postures, it also considers whether a working process has static or dynamic movement sequences. It is of particular assistance in fulfilling the assessment requirements of both the European Community Directive (90/270/EEC) on the minimum safety and health requirements for work with display screen equipment and the UK Guidelines on the prevention of work-related upper limb disorders [

19]. The OWAS (Ovako Working posture Analysis System method) was intended to identify the frequency and time spent in the postures adopted in each task, to study and evaluate the situation, and thus, recommends corrective actions. The OWAS identifies the most habitual back postures in workers (4 postures), arms (3 postures), legs (7 postures) and weight of the load handled (3 categories) [

20]. Another tool used to assess work postures and the resulting load on the body is the LUBA (Postural Loading on the Upper Body Assessment) system [

21], and the ULRA (Upper Limb Risk Assessment) tool is also used in practice to assess upper limb strain [

22]. NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health) methodology is used for assessing lifting actions by means of a quantitative method based on intensity, duration, frequency, and other geometrical characteristics of lifting. Authors [

23,

24] explored the machine learning (ML) feasibility to classify biomechanical risk according to the revised NIOSH lifting equation. Acceleration and angular velocity signals were collected using a wearable sensor during lifting tasks. The OCRA (Occupational repetitive action) is a commonly applied method of evaluating the musculoskeletal load of the upper limbs caused by repetitive tasks and the risk of developing MSDs [

25]. OCRA and ULRA assess the upper limb load based on body posture, exerted forces and time. However, these methods primarily differ in how they identify variables that describe posture, forces and time sequences. Authors [

26] analysed the convergence of two methods OCRA and ULRA by comparing exposure and the assessed risk of developing MSDs at 18 repetitive task workstations. Results revealed that using different methods can produce not just differences in exposure assessment but also differences in assignment to risk zones. Thus, evaluator should not rely on the output of a single risk assessment only. A method of load assessment, which is also like the NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) lifting equation, is the STRAIN Index (SI) [

27]. The values corresponding to the parameters as well as the resulting rating scale were developed based on research and biomechanical knowledge. Research conducted in years 2000 and 2002 confirmed the high accuracy of this tool in assessing the riskiness of work positions. Study [

28] focused on developing an inertial sensor-based approach to evaluate posture in industrial contexts, particularly in automotive assembly lines.

Based on the previous findings, there are many methods for evaluating working postures. However, there is a high degree of subjectivity in the risk assessment. Motion capture kinematic suits, motion sensors applied on the body can ensure the objectivity of the assessment [

29,

30,

31].

In collaboration with INRS (French National Institute for Research and Safety), TEA company has developed Captiv, an innovative data collection system to synchronize video sequences together with visual observations and sensor measurements in the application of physical load threshold values related to working positions as well as other physiological characteristics [

34].

The aim of the paper is to compare results and identify differences of the assessment of ergonomic load through the used legislative regulations in Slovakia and other standards. A series of measurements were carried out on a sample of workers at a car headlight quality control assembly workplace using the Captiv wireless sensor system. Using the Captiv software, the measured data were processed. However, during the actual evaluation of the working postures and movements at work, obstacles were discovered with some differences in the applicable standards in the field of physical load assessment. The Decree 542/2007 Coll. which is in force in the territory of the Slovak Republic and also the STN EN 1005-4+A1 standard [

9,

33], however, define the thresholds for risk positions at work with significant differences in several assessed body parts, which also affects the final evaluations of measurements. These standards were compared with the current French standards default in the Captiv system. We placed emphasis on determining whether the differences in values are statistically significant or whether the difference is negligible.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Most Important Issues Of Standards for Physical Load Assessment

In terms of issues standardized requirements (standards, laws), there is a valid legislation decree 542/2007 Coll. in Slovakia (in the next only Legislation) on details of the protection of health against physical load at work, psychological workload and sensory workload at work, and there is also a standard STN EN 1005-4+A1 [

9] (further as STN EN), standards assess the physical load at work based on the working postures of individual body segments. However, when comparing them with each other, we have concluded that in many of the limiting boundaries of the postures these standards do not coincide, which in practice means that the final evaluation of the workload also differs based on the standard used.

From

Table 1, these standards differ in several parameters, subsequently in the overall system of assessment of the individual segments. In some parameters, the variation is moderate, but for some, the difference in the threshold values for individual postures is significant. This ultimately has an impact on the final evaluation of the working postures, so we consider it appropriate to modify these thresholds in the currently used standards.

Significant variations occur in the limits of acceptable movements for the head and neck region, where the Legislation refers to head forward flexion and head backward flexion, whereas the STN EN describes only head forward flexion, but with a considerably greater range. Same, the zero axis, from which the limit values of movements are derived, does not completely coincide [

9,

32,

33].

In the case of determining the limiting movements and postures for the trunk area during static work, the STN EN and the Legislation agree in limiting the bending to 60°. For dynamic work, the range of unacceptable postures is no longer the same, with a difference of up to 40° in the limitation of bending, with a greater range permitted by the STN EN Standard. For other postures and movements of the trunk at work, the STN EN and the Slovak Legislation agree on several parameters in the area of conditionally acceptable movements, namely they allow bending with support in static work, in the performance of dynamic work they also allow bending with a frequency of less than 2/min., also bending of 60° with the same frequency [

9,

32,

33].

If we want to proceed the analysis and comparison between the Legislation and the STN EN, a rate of non-compliance is observed, here. In fact, for the delimitation of the movements of the upper and lower limbs, the Legislation and the STN EN use different parts of the limbs, for the representation of their movements, the STN EN does not even contain a chapter with a precise specification of the movements of the lower limb. For the description of the limit postures and movements of the other parts of the body, according to both the Legislation and the STN EN, a general description applies, which excludes postures close to the limit postures of the ranges of movement and uncomfortable postures [

9,

32,

33].

It is also important to note that within the standards a limb is often represented as a whole part, not specifically by single joints, for example the upper limb is represented by the upper arm. To illustrate this on example, the Decree 542/2007 Coll. uses two points to define the position of the upper limb, namely the outer edge of the clavicle and the elbow joint. However, we do not consider this assessment to be sufficient, as this principle does not consider movements in the elbow joint or in the wrist, which has been a problematic part of the body in recent years, due to the trend of a high percentage of carpal tunnel.

This raises the question of the adequacy of the Legislation and the STN EN in this respect, since each limb also contains articulations, the movements of which are more directive and more accurately measurable. It is therefore inadequate in practice to use such a representation of a limb by one part of it. The upper limb itself consists of the shoulder, elbow, and wrist joints, and likewise the lower limb consists of the articulations as the hip, knee and ankle. The movements of the individual joints cannot be represented by the movement of the whole part of the limb, which consequently makes such an assessment inappropriate. Therefore, we believe that a review of the existing standards and their possible modification is necessary to allow practical assessment of workload with reference to current standards [

9,

32,

33].

The Captiv wearable multisensory system is used to measure movement for post-processing in the form of multi-functional analysis of posture, load capacity, musculoskeletal constraints and repetitive movements and vibrations. It is a flexible, scalable measurement and analysis toolset for ergonomics, workplace analysis, occupational safety, HMI (Human-Machine Interface) prototyping, research, VR (virtual reality) and other applications [

35].

The essence of ergonomic risk assessment is to identify risk factors in the work environment that have the potential to cause damage to the musculoskeletal system, which we want to minimize as part of the prevention and protection of human health. If the input parameters for the assessment are set correctly and the correct work procedure is followed using the chosen method, there is a high probability that the resulting assessment will yield the correct conclusions.

Therefore, we focused on the evaluation of the deviations obtained by evaluating the same parameters measured with the Captiv system [

34] during our research, according to the Legislation [

32] and STN EN [

9]. The Captiv itself has pre-set threshold values [

34,

35] for acceptable, conditionally acceptable, and unacceptable postures, but these are based on French standards, which also differ from the standards valid in the Slovak Republic. The inter-comparison of these standards is summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of posture limits for unacceptable and conditionally acceptable postures among STN EN 1005-4+A1, Legislation 542/2007 Coll. SR and Captiv (FR legislation).

Table 1.

Comparison of posture limits for unacceptable and conditionally acceptable postures among STN EN 1005-4+A1, Legislation 542/2007 Coll. SR and Captiv (FR legislation).

| Segment |

Risk Level |

Type of work |

Legislation

(Coll. SR 542/2007) |

STN EN

(STN EN 1005-4) |

Captiv |

| Head and Neck |

Unacceptable |

Static |

Forward flexion without support 25° |

Forward flexion 40° |

/ |

| Extension without support |

Lateral flexion >10° |

| Lateral flexion/Rotation >15° |

Rotation >45° |

| Dynamic |

Forward flexion >25°, f≥2/min |

Forward flexion 40°, f≥2/min. |

Forward flexion ≥30° |

| Lateral flexion/Rotation 15°, f≥2/min |

Lateral flexion >10°, f≥2/min. |

Extension ≥20° |

| |

Rotation >45°, f≥2/min. |

Lateral flexion ≥20° |

| |

|

Rotation ≥30° |

| Conditionally acceptable |

Static |

Forward flexion 25-40° with back support |

/ |

/ |

| |

| Dynamic |

Forward flexion 25-40°, f=2/min |

Forward flexion 40°, f<2/min. |

Forward flexion ≥15° |

| Extension <15°, f<2/min |

Lateral flexion >10°, f<2/min. |

Extension ≥10° |

| Lateral flexion <15°, f<2/min |

Rotation >45°, f<2/min. |

Lateral flexion ≥10° |

| Rotation <15°, f<2/min |

|

Rotation ≥15° |

| Back |

Unacceptable |

Static |

Forward flexion>60° |

Forward flexion >60° |

/ |

| Extension without support/significant lateral flexion/rotation >20° |

Lateral flexion/Rotation >10° |

| Dynamic |

Forward flexion ≥60°, f≥2/min |

Forward flexion >20°, f≥2/min. |

Forward flexion ≥45° |

| Significant lateral flexion/rotation >20°, f≥2/min. |

Extension, f≥2/min. |

Extension ≥20° |

| |

Lateral flexion/Rotation >10°, f≥2/min. |

Lateral flexion ≥20° |

| |

|

Rotation ≥30° |

| Conditionally acceptable |

Static |

Forward flexion without support 40-60° |

Forward flexion with support 20-60° |

/ |

| Extension with support |

Extension with support |

| Lateral flexion/Rotation >10° a <20° |

|

| Dynamic |

Forward flexion 60°, f=2/min. |

Forward flexion >60°, f<2/min. |

Forward flexion ≥30° |

| Extension, f<2/min. |

Extension, f<2/min. |

Extension ≥10° |

| Lateral flexion right/left >20°, f<2/min. |

Lateral flexion/ Rotation >10°, f<2/min. |

Lateral flexion ≥ 10° |

| |

|

Rotation ≥15° |

| Upper limb |

Unacceptable |

Static |

Shoulder flexion >60° |

Flexion >60° |

/ |

| Awkward positions |

Extension |

| |

Abduction >60° |

| |

Adduction |

| Dynamic |

Shoulder flexion >60°, f≥2/min. |

Flexion >60°, f≥2/min |

Vertical rotation right/left ≥90° |

| Shoulder extension, f≥2/min. |

Extension, f≥2/min. |

Horizontal rotation right/left -90°/30° |

| |

Abduction >60°, f≥2/min. |

Rotation internal/external -60°/45° |

| |

Adduction, f≥2/min. |

|

| Conditionally acceptable |

Static |

Shoulder flexion 40-60° without support |

Flexion 20-60° with shoulder support |

/ |

| |

Abduction 20-60° with shoulder support |

| Dynamic |

Shoulder flexion 40-60°, f=2/min. |

Flexion >60°, Extension, f<2/min. |

Vertical rotation right/left ≥60° |

| Shoulder extension, f<2/min. |

Abduction>60°, Adduction, f<2/min |

Horizontal rotation right/left -70°/10° |

| |

Flexion 20-60°, f≥2/min. |

Rotation internal/external -40°/20° |

| |

Abduction 20-60°, f≥2/min. |

|

| Lower limb |

Unacceptable |

Static |

Extreme positions of knee/ankle |

UNDEFINED |

/ |

| Dynamic |

Movements close to range of motion limits, f≥2/min. |

Rotation internal/external 30°/-20° |

| |

Flexion/Extension 100°/-20° |

| |

Abduction/Adduction 30°/-20° |

| Conditionally acceptable |

Static |

/ |

/ |

| Dynamic |

Movements close to range of motion limits, f<2/min. |

Rotation internal/external 10°/-10° |

| |

|

Flexion/Extension 70°/-10° |

| |

|

Abduction/Adduction 20°/-10° |

| Other body segments |

|

|

Extreme positions, uncomfortable |

Extreme positions, uncomfortable |

- |

2.2. Measurement Procedure

The basic principle of the ergonomic analysis in this article is to monitor the time duration individual body segments spent (N - Neck, RS - Right Shoulder, LS - Left Shoulder, RE - Right Elbow, LE - Left Elbow, UB - Upper Back, LB - Lower Back) in a specific working posture expressed in percentages using three different methodologies (standards in Captiv, STN EN and Legislation.

The measurement plan consisted of steps:

Preparation of the used measuring tool Captiv.

Positioning of the sensors on the worker based on the activity to be performed and based on the observed location of the expected strain.

Processing the measured values of the percentage of time duration the measured body segments remain in an acceptable, conditionally acceptable, or unacceptable position, in terms of the three standards.

Evaluation of the measured values and their comparison.

Description of the findings from the processed measured and compared values.

Five workers aged 23 to 45 years participated in the measurement. A series of measurements were carried out on a sample of workers at a headlight (HDL) quality control assembly station. During the work activity, the worker performed the following work operations: took the label from the printer and stuck it on the HDL; removed the HDL from the pallet and put it on the Xpert table; checked the light according to the test instructions; the OK light put in the box and sent it to the Q-gate (NIO part put away in the red box). Work was done in standing position. The nature of the work is rather static, with a semi-dynamic component of movement when picking and putting away the part. The microclimatic conditions at the time of measurement were as follows: atmospheric pressure 1012 hPa, air temperature 22 ˚C, humidity 53%.

The measured joints, according to the standards, were: neck, back (axis: pelvis - vertebral segment T2), left shoulder, right shoulder, left forearm, right forearm. For proper 3D visualization, the subject was equipped with a sensor on the back (for upper body tracking) and on the lumbar region of the sacrum (for lower back and hip tracking). To measure the physical load for the ergonomic risk assessment of work postures, 7 motion IMU sensors were used in relation to the frequency and length of work movements. Sensor’s placement (

Figure 1) on Avatar in Captiv was chosen according to measured joints for results in upper body part: N - Neck, RS - Right Shoulder, LS - Left Shoulder, RE - Right Elbow, LE - Left Elbow, UB - Upper Back, LB - Lower Back. The sensor located in the UB provides information about the position of the neck. Measured body segments and their labelling are explained in

Table 2.

The thresholds were determined by three standards, Legislation, STN EN and INRIS standards built into the Captiv system, which are part of the evaluation and sorting of the collected data according to the time duration spent in each position.

2.3. Statistical Testing

Basic statistical methods were used to analyse the measured data on the percentage of time duration each body segment remained in the acceptable, conditionally acceptable and unacceptable positions: descriptive statistics and statistical hypothesis testing methods.

In statistical hypothesis testing, the decision to reject or accept the null hypothesis is made using the p-value. If the p-value is less than the specified significance level α, the null hypothesis is rejected in favour of the alternative hypothesis. If the p-value is equal to or greater than the chosen significance level α, then we do not reject the null hypothesis.

Paired

t-test was used to compare the resulting values. The condition of normality is also a prerequisite for use. In practice, two main tools are used to assess normality: graphical representation of data and visual assessment of normality (e.g., histogram, Q-Q plot, P-P plot), or testing using statistical tests (e.g., Shapiro-Wilk normality test, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Anderson-Darling test, etc.) [

36]. To assess normality, we use the Shapiro-Wilk normality test, which is the most used normality test for small to medium range up to 2000. We test the null hypothesis: “the sample distribution is normally distributed” against the alternative hypothesis “the sample distribution is not normally distributed”. For data assessment, the statistical software R was used. R is an official part of the Free Software Foundation’s GNU project and can be downloaded as open-source software for statistical calculations.

For the evaluation, we used the differentiation of the values of the measured percentages on the different stressed body parts by means of three different evaluation methods. We calculate the difference in each working position (acceptable, conditionally acceptable, unacceptable) at each measurement point for each respondent according to the formula:

where

represents the percentage in the corresponding working posture obtained by a given method,

determines the

k-th measurement part of the run,

n is the number of measurements stressed body parts and

r is the respondent’s order,

. The difference represents how much the proportion in a given area increased (

) or decreased (

) for

.

3. Results of Ergonomic Risk Assessment with Different Standards and Their Limits

The aim of the experimental research was:

to measure the time duration of individual body segments in a specific working posture for 5 workers using three assessment methods,

to determine the time duration of individual body segments in acceptable (green), conditionally acceptable (orange), unacceptable (red) working postures,

determine the difference between three methods: Legislation (L), STN EN (S) and Captiv system (C).

To determine the degree of physical load, we monitored the time duration of individual body segments in working postures expressed as a percentage during the work activity. Load assessment was performed with five respondents. Basic information about the respondents assessed is presented in

Table 3.

Measurements were made for each respondent three times, and the measured mean value was used in the evaluation. For illustration, we provide a graphical representation of the measured values with evaluation according to the limit values of the Captiv, Legislation and STN EN standard in the case of respondent Resp1. The graphs at

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the percentage of time duration in acceptable (G - Green area), conditionally acceptable (O - Orange area) and unacceptable work posture (R - Red area) of the total duration of work task in terms of the three different methods for physical load assessment (L - Legislation, C - Captiv, S – STN EN).

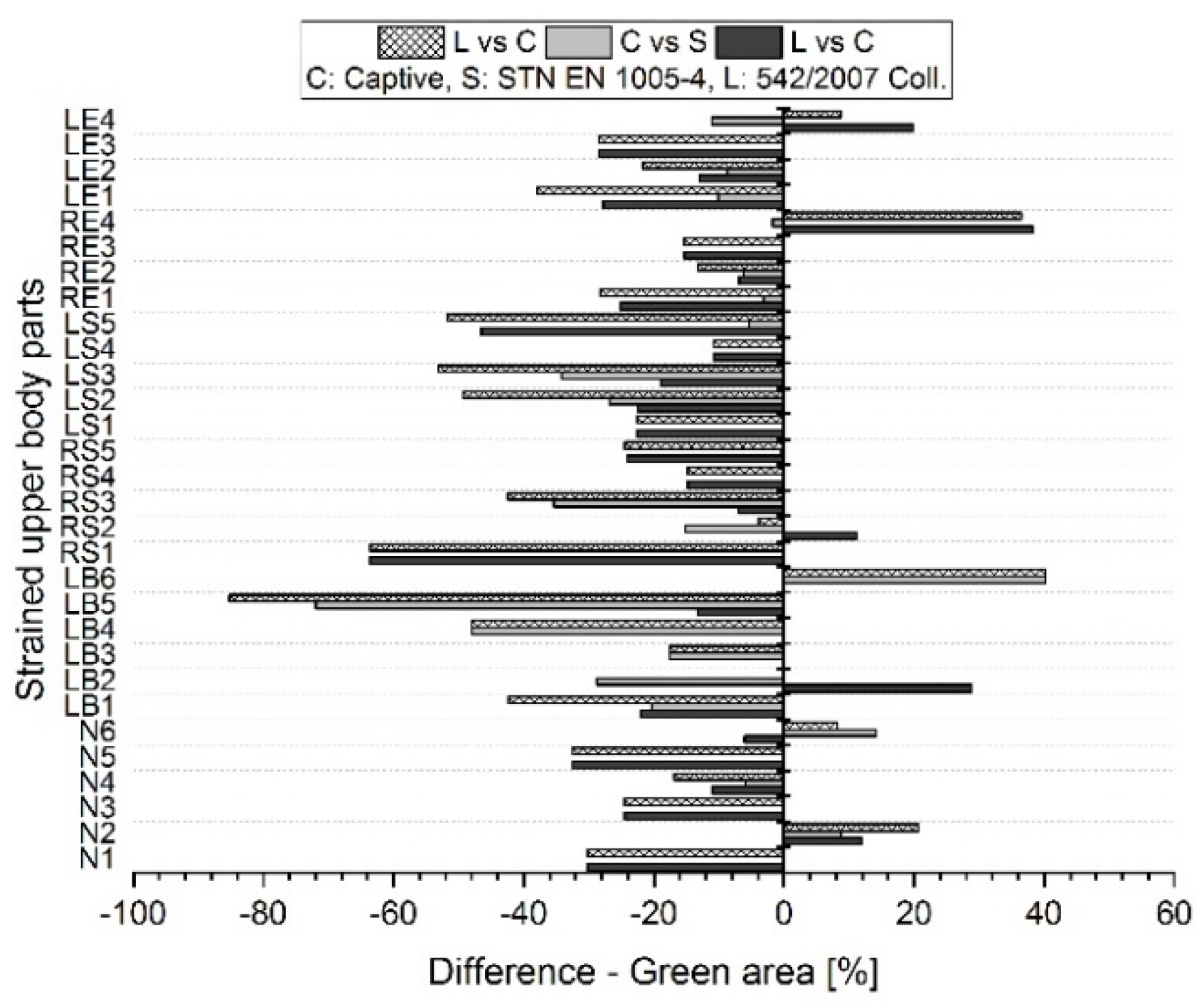

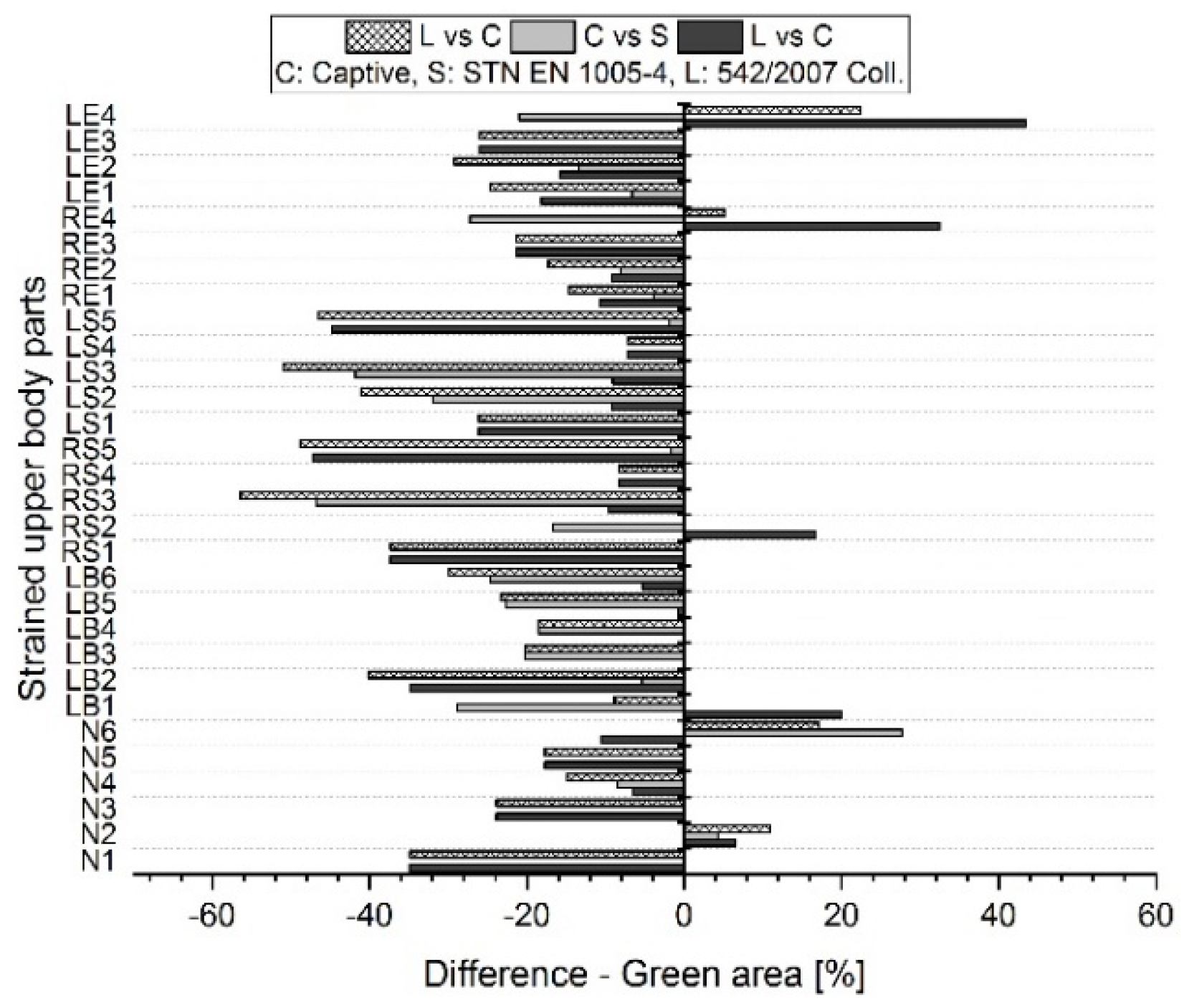

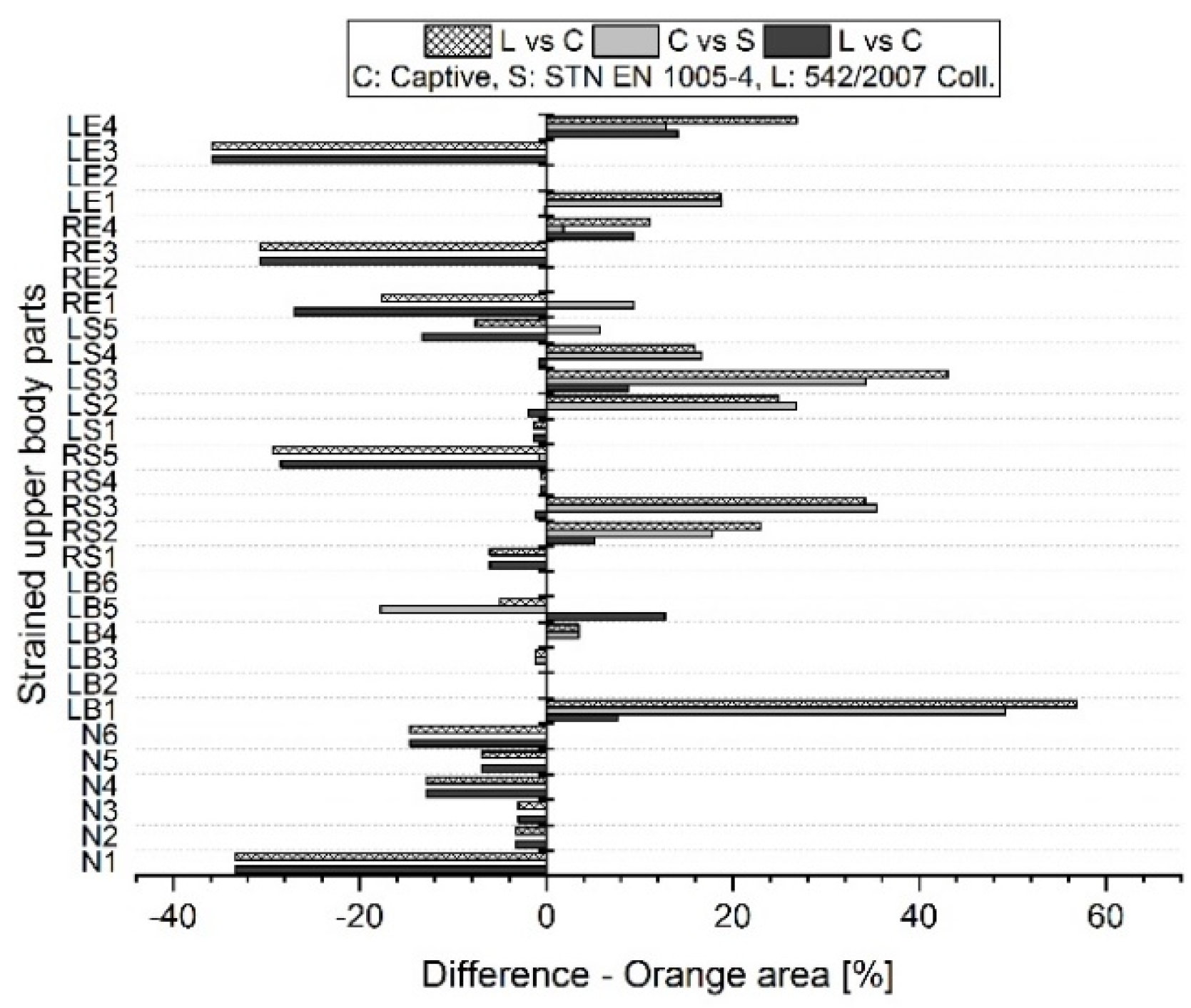

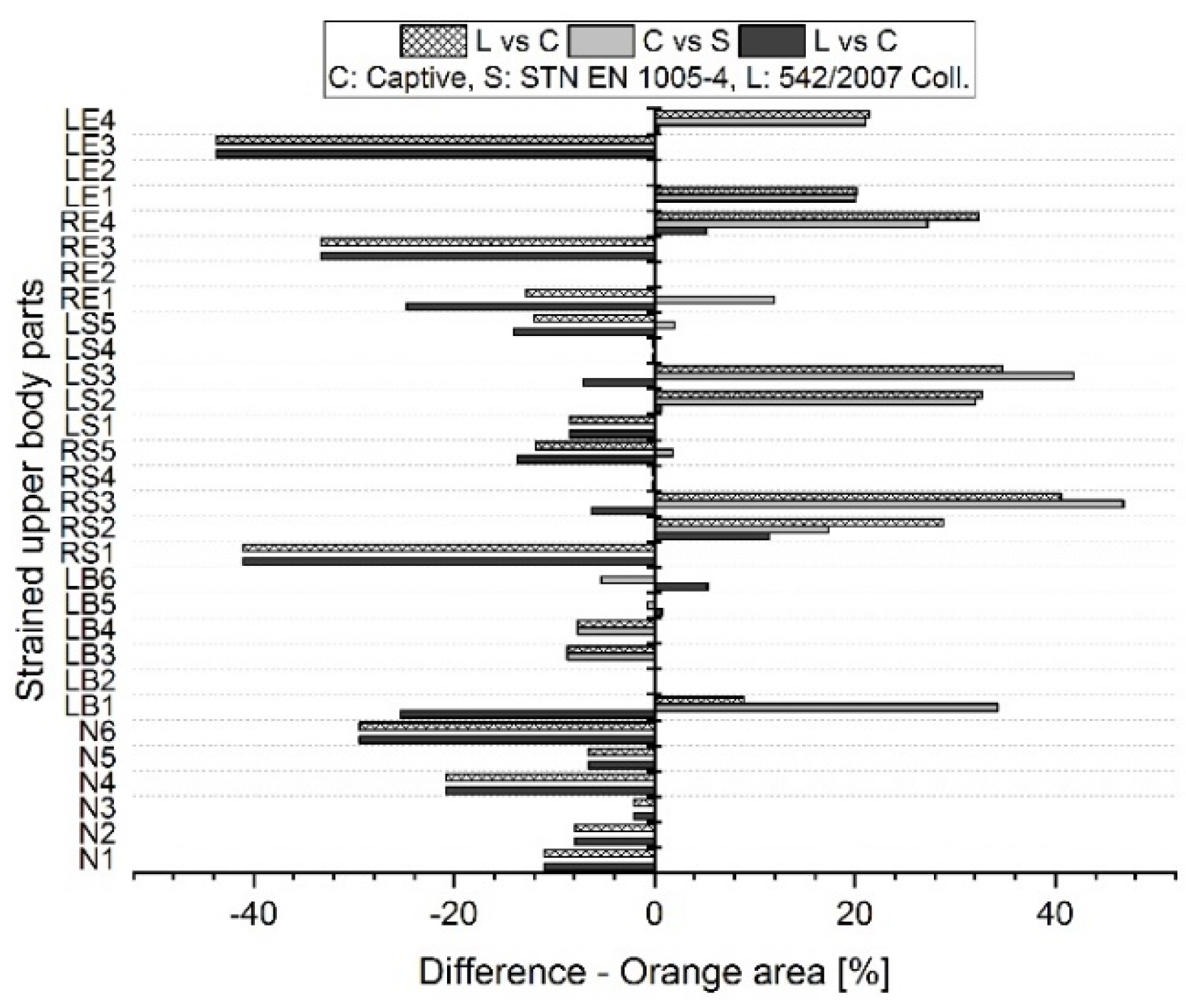

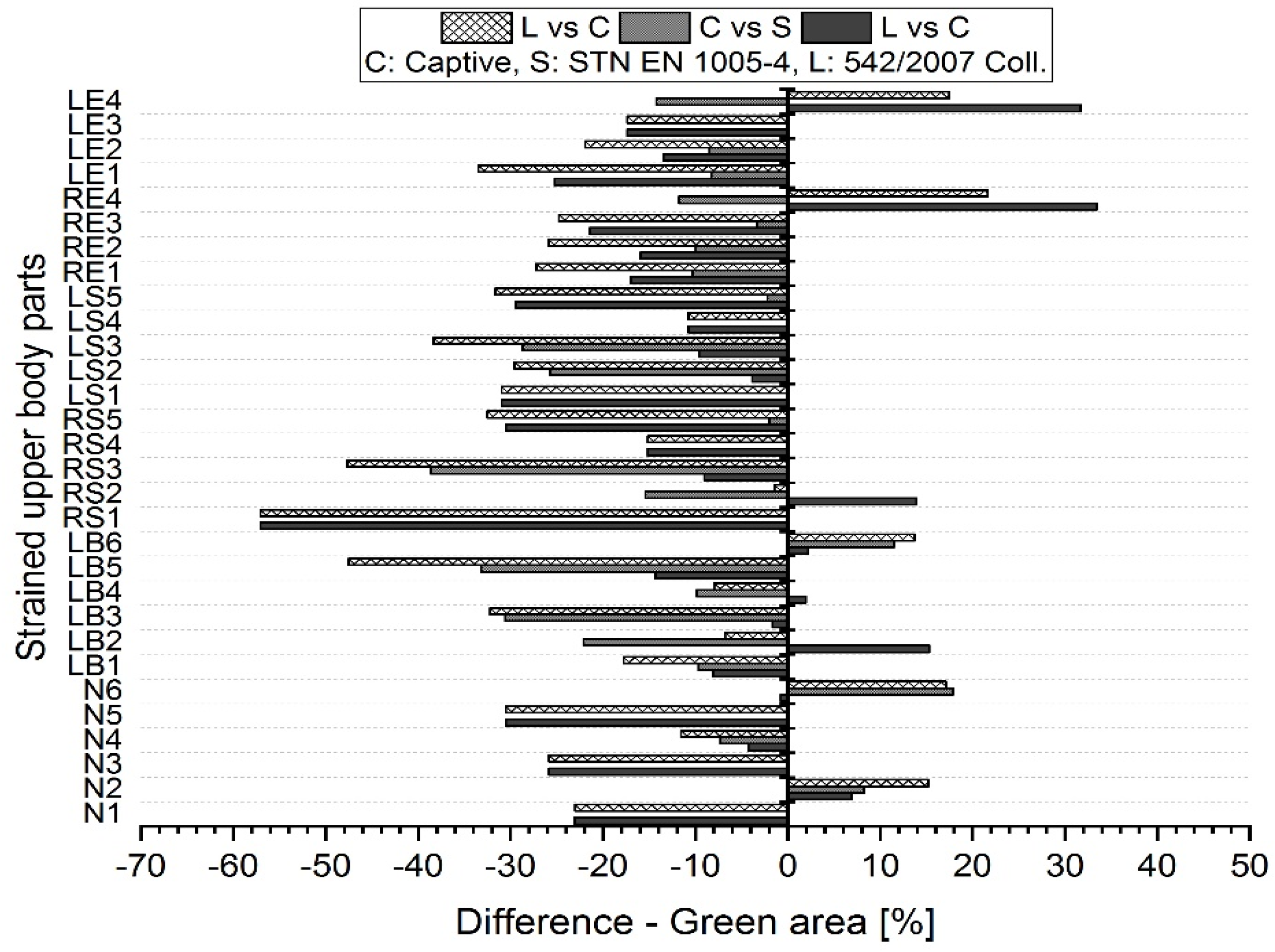

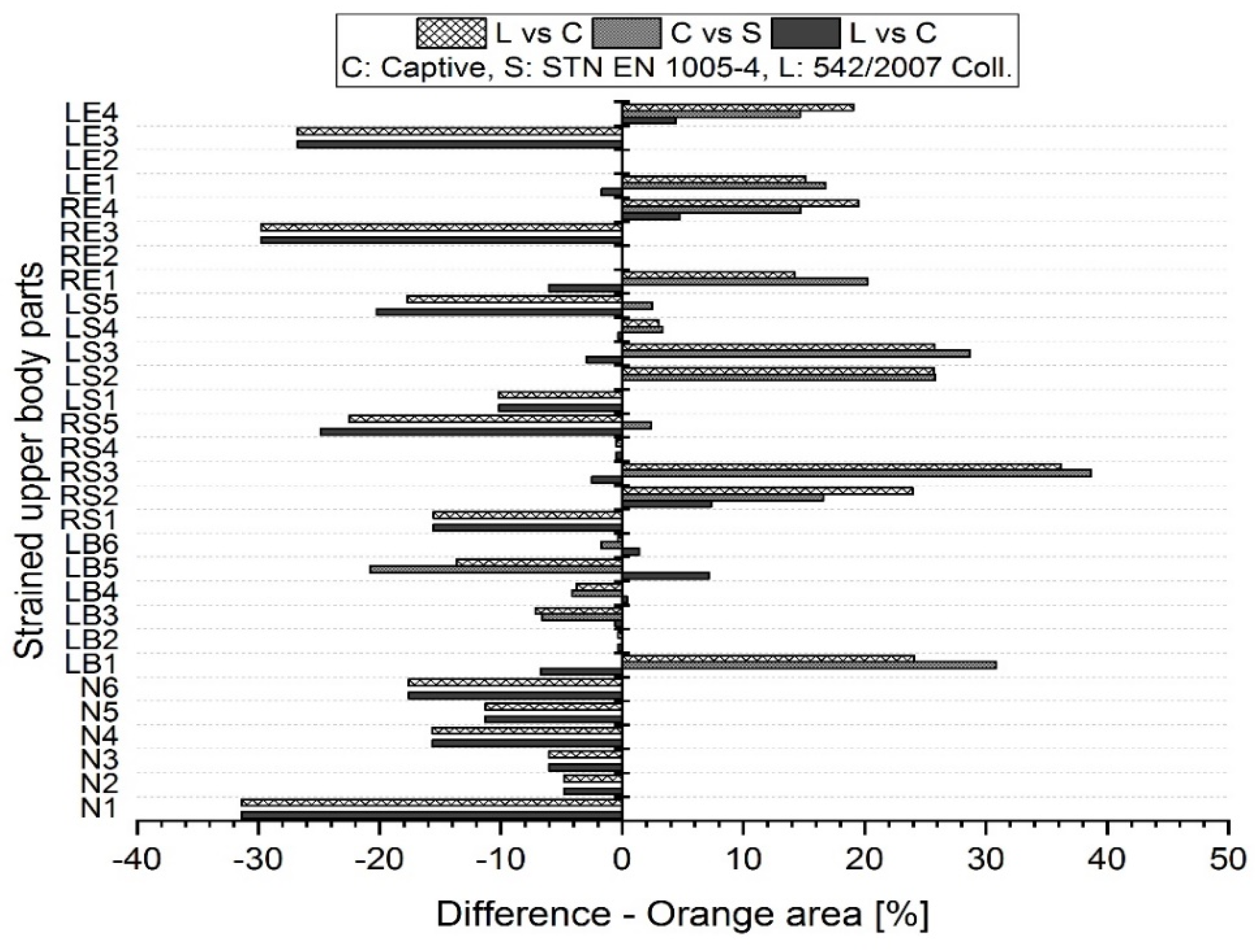

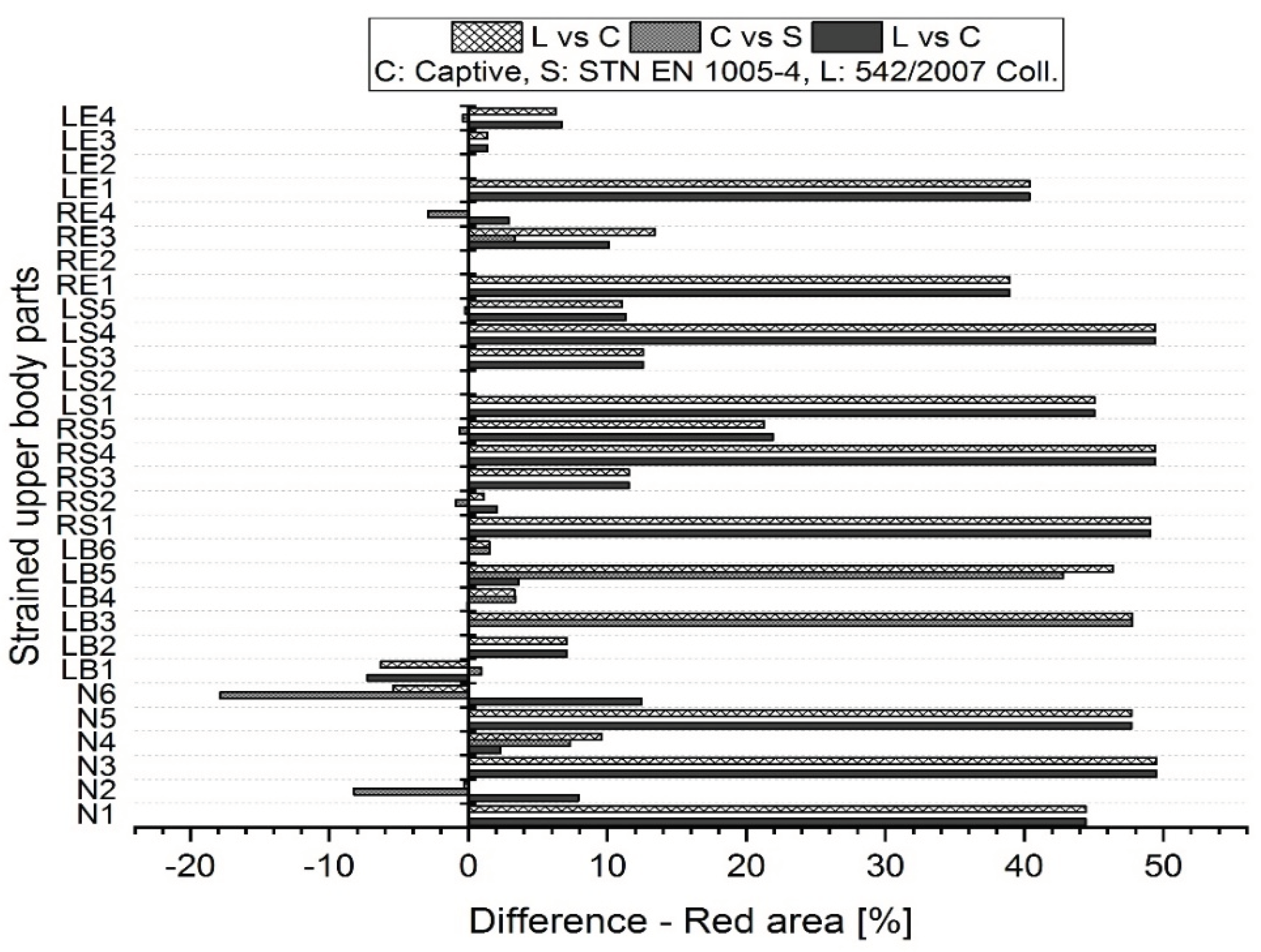

The results analysis shows that the obtained values of the percentages of time duration in acceptable, conditionally acceptable and unacceptable working postures differ in terms of the threshold values or assessment methods used (see Formula (1)). Graphical representations of the differences for the first two respondents are shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

It shows that when comparing the Legislation and Captiv methods, the Captiv method significantly reduces the percentage in an acceptable position in most of the stressed body parts (). On the other hand, it significantly increases the percentage in the unacceptable position in most of the stressed body parts for each respondent (). The comparison between the Legislation and STN EN, or Captiv and STN EN methods is analogous.

The resulting mean differences

at each location of the stressed body part in each position are graphically shown in

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13.

In the next step, we test the equality of the means of the percentage of time duration the segments spend in each position out of the total work activity using a paired t-test. The null hypothesis is “the means of the different groups are the same” and the alternative hypothesis is “At least one sample mean is not equal to the others”.

The prerequisite for using the paired t-test is to verify normality. Verification of normality of the measured values is realized by the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. For each type of panel, we test “The null hypothesis is that sample distribution is normal”. If the p-value is less than the α significance level, the null hypothesis is rejected, and the distribution is non-normal. Since for each sample set the p-value > α, we do not reject the null hypothesis of normality for each underlying set. In our case, all samples follow a normal distribution. The resulting table of paired t-test for Resp1 in the Green work domain for Legislation vs Captiv (L vs C), Captiv vs STN EN (C vs S), and Legislation vs STN EN (L vs S) is shown in

Table 4.

Because the p-value is below the significance level (p-value<α), we reject the null hypothesis of means equality. The results show that there are statistically significant differences between the values. The complete results of the 45 paired tests in all areas (green, orange, red) for Respondent 1 are in

Table 5 and

Table 6. If the

p-value is less than the significance level, we can assume that the differences are significant (SD in the table).

The results of the testing show that there are statistically significant differences between the values measured by the L and C methods in all areas (Green, Orange, Red) and for all surveyed respondents. There are significant differences (SD) between the C and S methods in the Green and Orange areas. For the comparison between methods L and S, there are significant differences (SD) in the Green and Red areas. There are no significant differences between methods C and S in the Red (N) area. In the case of the comparison between methods L and S, there are no significant differences in the Orange (N) area.

Table 7 shows the summary results. The first respondent Resp1 was summed up to 67.46% of the total duration of work activity in the acceptable position (green area) and 20.86% in the conditionally acceptable position (orange area) according to the L method. Only 11.68% of the total duration of work activity was in the unacceptable position (red area). In terms of the C method, Resp1 respondent was up to 45.44% of the total duration of work activity in the unacceptable position. For the S assessment method, it is even up to 51.88% of the total duration of work activity. There are similar differences for the other respondents.

Analysis of the results shows that respondents were in an acceptable position for approximately 63% of the total duration of the work activity in terms of the L method. Using the C method, approximately 44% of the total duration of work activity is in an acceptable position. The least favourable rating is for the S method, respondents are only 27% of the total duration of work activity in an acceptable position, which is 2.33 times less than the L method.

4. Discussion

In our research, we did not attempt to decide on the correctness of either method. We intend to continue this research and extend measurements with more workers and types of provided work by different professions. The main aim was to highlight the need for refinement of existing methodologies, not only in terms of aligning national and European standards, but also in terms of refining and unifying biomechanical models. These demands increased international research cooperation. Based on our observation, we found that the Captiv standards allow a wider analysis (whole body) for WMSDs risk assessment, while the Slovak legislation and STN EN is more suitable and accurate for assessing the ergonomic risk of upper limb.

5. Conclusions

This contribution presents our approach towards advanced monitoring and assessment system for ergonomic improvements, addressing the high incidence of MSDs in Slovak industry, especially during assembly operations in the automotive industry. Ergonomic assessment of physical worker activity with wireless multisensory system Captiv, especially working postures capturing, can help in prevention of MSDs disorders. Captiv system belongs to advanced methods for direct measurements using monitoring instruments that rely on sensors attached directly to the subject for the measurement of exposure variables at work. Captiv is an innovative data collection system to synchronize video sequences together with visual observations and sensor measurements in the application of physical load threshold values related to working positions as well as other physiological characteristics. Such quantitative data sensing reduces the subjectivity and refines the ergonomic risk assessment.

We used Captiv system in our study for physical load assessment at the car light quality control workplace, which is the part of machinery production line. Collected data were analysed by three methods: legislation Decree 542/2007 Coll. in Slovakia (Legislative), standard STN EN 1005-4+A1 (STN EN), Captiv INRIS France based standards. Both, Legislative and STN EN assess the physical load at work based on the working postures of individual body segments. However, these valid rules do not coincide in many parameters in the field of workload assessment. They differ in the threshold values determining different motion sequences – acceptable, unacceptable, and conditionally acceptable positions. Further, often the motion is related to the whole limb not considering movements and positions of particular smaller segments/joints. Therefore, complications arise when trying to research and evaluate ergonomic risk (physical load) due to inconsistency of current rules. The range of acceptable values pre-set in the Captiv system also varies. Therefore, we compared Slovak requirements (Legislative and STN EN) with its threshold values used for workload assessment.

Results of differences between standards in the ergonomic risk assessment of work positions must be further researched. Comparison of the values for upper limb, whether unacceptable or conditionally acceptable, is difficult as the form or the specific segment/joint according to which the assessment was made, does not match. In defining the movements of the back, the Legislation coincides with the Standard in defining the unacceptable forward flexion, the conditionally acceptable ranges of both forward flexion and extension. The STN EN agrees with the Captiv system in defining the angle of lateral flexion. Limits in Slovak legislation, in contrast to default limits used in Captiv, distinguish static and dynamic type of work, too. The analysis of the assessment shows that the determination of the time duration of the individual stressed parts in the different work areas (green, orange, red) is also influenced by the choice of the assessment methodology (C, L, S). In the future, it would also be advisable to consider the degree of tolerance of differences that would be acceptable for the final assessment of the worker’s physical load. Analysis of the results shows that respondents were in an acceptable position for approximately 63% of the total duration of the work activity in terms of the L method, approximately 44% of the total duration of work activity is in an acceptable position using C method. The least favourable rating is for the S method, respondents are only 27% of the total duration of work activity in an acceptable position.

Practical application: Captiv assessment standards allow a wider analysis for workplace with incidence of MSDs for the whole-body, and the Slovak Legislation and the STN EN standards we recommend using in the assessment of upper extremities. We do not recommend using Legislation and STN EN standard for the assessment of lower extremities.

Simultaneously, we want to consider possible measures, as one of the priority solutions is to test the suitability of exoskeleton implementation, as supporting technical devices in strenuous work, within the ergonomic prevention projects. To select the right exoskeleton, it is essential to evaluate the work process and the physical load, eventually mental load that accompanies the particular work task.

Even for supporting this research, we need to objectify noticed positives and shortcomings in Slovak legislation. There is a need for uniform standards for ergonomic risk assessment of body posture, not forgetting a more detailed description of the threshold values of the individual body segments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.O., D.P., M.A., H.P., L.S.; methodology, D.O.; validation, D.O. and H.P.; formal analysis, D.P., D.O.; investigation, D.P., D.O.; resources, D.O. and D.P.; data curation, D.O. and M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.O., M.A., D.P.,; writing—review and editing, D.O., L.S.; visualization, M.A. and D.O.; supervision, H.P.; project administration, D.O. and H.P.; funding acquisition: H.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Technical University of Kosice (protocol code 8268/2021/R-OLP and date of approval 13.12.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions eg privacy or ethical. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to measurement in private industrial sector.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge for the support by the Slovak Agency Supporting Research and Development APVV-19-0367. This publication is the result of the project implementation Research and development of intelligent traumatological external fixation systems manufactured by digitalization methods and additive manufacturing technology (Acronym: SMARTfix), ITMS2014+: 313011BWQ1 supported by the Operational Programme Integrated Infrastructure funded by the European Regional Development Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kok, J.; Vroonhof, P.; Snijders, J.; Roullis, G.; Clarke (Panteia), M.; Peereboom, K.; Dorst, P.; Isusi, I. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: prevalence, costs and demographics in the EU. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, 2019. ISSN: 1831-9343. [CrossRef]

- National Health Information Centre (NCZI). Occupational disease or threat of occupational disease. Available online: https://www.nczisk.sk/statisticke_vystupy/tematicke_statisticke_vystupy/choroby_povolania_alebo_ohrozenia_chorobou_povolania/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Grooten, J.W.A.; Elin, J. Observational Methods for Assessing Ergonomic Risks for Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders. Journal of Revista Ciencias de la Salud 2018, 18, 8–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Breloff, S.P.; Dai, F.; Sinsel, E.W.; Warren, C.M.; Carey, R.E.; Wu, J.Z. Effects of working posture and roof slope on activation of lower limb muscles during shingle installation. Journal of Ergonomics 2020, 63, 1182–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakovic Husic, J.; Melero, F.J.; Barakovic, S.; Lameski, P.; Zdravevski, E.; Maresova, P.; Krejcar, O.; Chorbev, I.; Garcia, N.M.; Trajkovik, V. Aging at Work: A Review of Recent Trends and Future Directions. Journal of Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 7659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejer, R.; Ruhe, A. What is the prevalence of musculoskeletal problems in the elderly population in developed countries? A systematic critical literature review. Journal of Chiropr Man Therap 2012, 20, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Standard EN 16710-2. Ergonomics methods Part 2: A methodology for work analysis to support design.

- European Standard EN ISO 11228-1. Ergonomics. Manual handling. Part 1: Lifting, lowering and carrying.

- Standard STN EN 1005-4+A1:2009. Safety of machinery. Human physical performance. Part 4: Evaluation of working postures and movements in relation to machinery.

- Gualtieri, L.; Rauch, E.; Vidoni, R. Development and validation of guidelines for safety in human-robot collaborative assembly systems. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2022, 163, 107801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makovicka Osvaldova, L.; Sventekova, E.; Maly, S.; Dlugos, I. A Review of Relevant Regulations, Requirements and Assessment Methods Concerning Physical Load in Workplaces in the Slovak Republic. Journal of Safety 2021, 1, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, G.C. Ergonomic methods for assessing exposure to risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Journal of Occupational Medicine 2005, 55, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Afari, M.F.; Li, H.; Chan, A.H.S.; Seo, J.; Anwer, S.; Mi, H.Y.; Wu, Z.; Wong, A.Y.L. A science mapping-based review of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among construction workers. Journal of Safety Research 2023, 85, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hita-Gutiérrez, M.; Gómez-Galán, M.; Díaz-Pérez, M.; Callejón-Ferre, Á.J. An Overview of REBA Method Applications in the World. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakaraparthi, V.N.; Vishwanathan, K.; Gadhavi, B.; Reddy, R.S.; Tedla, J.S.; Alshahrani, M.S.; Dixit, S.; Gular, K.; Zaman, G.S.; Gannamaneni, V.K.; et al. Clinical Application of Rapid Upper Limb Assessment and Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire in Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Bibliometric Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, D. Systematic Comparison of OWAS, RULA, and REBA Based on a Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hignett, S.; McAtamney, L. Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA). Journal of Applied Ergonomics 2000, 31, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAtamney, L.E.; Corlett, N. RULA: a survey method for the investigation of work-related upper limb disorders. Applied Ergonomics 1993, 24, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karhu, O.; Kansi, P.; Kuorinka, I. Correcting working postures in industry: A practical method for analysis. Journal of Applied Ergonomics 1977, 8, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Galán, M.; Pérez-Alonso, J.; Callejón-Ferre, Á. J.; López-Martínez, J. Musculoskeletal disorders: OWAS review. Journal of Industrial health 2017, 55, 314–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, D.; Karwowski, W. LUBA: an assessment technique for postural loading on the upper body based on joint motion discomfort and maximum holding time. Journal of Applied Ergonomics 2001, 32, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman-Liu, D. Repetitive task indicator as a tool for assessment of upper limb musculoskeletal load induced by repetitive task. Journal of Ergonomics 2007, 50, 1740–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donisi, L.; Cesarelli, G.; Coccia, A.; Panigazzi, M.; Capodaglio, E.M.; D’Addio, G. Work-Related Risk Assessment According to the Revised NIOSH Lifting Equation: A Preliminary Study Using a Wearable Inertial Sensor and Machine Learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, T.R.; Putz-Anderson, V.; Garg, A.; Fine, L.J. Revised NIOSH equation for the design and evaluation of manual lifting tasks. Journal of Ergonomics 1993, 36, 749–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman-Liu, D.; Groborz, A.; Tokarskai, T. Comparison of risk assessment procedures used in OCRA and ULRA methods. Ergonomics 2013, 56, 1584–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Occhipinti, E. OCRA: a concise index for the assessment of exposure to repetitive movements of the upper limbs. Journal of Ergonomics 1998, 41, 1290–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, A.; Moore, J.S.; Kapellusch, J.M. The strain index to analyze jobs for risk of distal upper extremity disorders: Model validation. IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Singapur, Singapur, 2.-4. January 2008. 20 January. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.L.; Folgado, D. Posture Risk Assessment in an Automotive Assembly Line Using Inertial Sensors. Applied research 2022, 10, 83221–83235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybnikar, F.; Kacerova, I.; Horejsí, P.; Simon, M. Ergonomics Evaluation Using Motion Capture Technology-Literature Review. Journal of Applied Science 2023, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, M.; Simon, M.; Rybnikar, F.; Kacerova, I.; Kleinova, J.; Vranek, P. Managing Risks and Risk Assessment in Ergonomics-A Case Study. In book: Research and Innovation Forum 2022, pp.683-697. [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, S.M.; Da Silva, A.F.; Santos, C., P. Smart Vest for Real-Time Postural Biofeedback and Ergonomic Risk Assessment. IEEE Access 2017, 8, 107583–107592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Regulation No. 542/2007 of 16 August 2007 on the details of health protection against physical strain at work, psychological workload and sensory strain at work. Available online: https://www.epi.sk/zz/2007-542. (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Onofrejova, D.; Balazikova, M.; Porubcanova, D. Legislative support for prevention and evaluation of ergonomic risks. Journal of Actual issues of work safety 2022, 35, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Monod, H.; Kapitaniak, B. Ergonomie. Collections des Abrégés de Médecine, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Masson, Paris. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Onofrejova, D.; Balazikova, M.; Kotianova, Z.; Glatz, J.; Vaskovicova, K. Ergonomic Assessment of Physical Load In Slovak Industry Using Wearable Technologies. Journal of Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrejiova, M.; Kimakova, Z. Basics of mathematical statistics, 1.st ed.; Technical University of Kosice: Kosice, Slovakia, 2022; p. 318. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Sensors Placement on Avatar in Captiv: N – Neck, RS – Right Shoulder, LS – Left Shoulder, RE – Right Elbow, LE – Left Elbow, UB – Upper Back, LB – Lower Back.

Figure 1.

Sensors Placement on Avatar in Captiv: N – Neck, RS – Right Shoulder, LS – Left Shoulder, RE – Right Elbow, LE – Left Elbow, UB – Upper Back, LB – Lower Back.

Figure 2.

Percentage of body segments in planes of motion: neck, lower back - stressed body parts I (Resp1). The evaluation processed by three methods: L, S, C. The example shows the processed result of one respondent.

Figure 2.

Percentage of body segments in planes of motion: neck, lower back - stressed body parts I (Resp1). The evaluation processed by three methods: L, S, C. The example shows the processed result of one respondent.

Figure 3.

Percentage of body segments in planes of motion: left shoulder, right shoulder - stressed body parts II (Resp1). The evaluation processed by three methods: L, S, C. The example shows the processed result of one respondent.

Figure 3.

Percentage of body segments in planes of motion: left shoulder, right shoulder - stressed body parts II (Resp1). The evaluation processed by three methods: L, S, C. The example shows the processed result of one respondent.

Figure 4.

Percentage of body segments in planes of motion: left elbow, right elbow - stressed body parts III (Resp1). The evaluation processed by three methods: L, S, C. The ex-ample shows the processed result of one respondent.

Figure 4.

Percentage of body segments in planes of motion: left elbow, right elbow - stressed body parts III (Resp1). The evaluation processed by three methods: L, S, C. The ex-ample shows the processed result of one respondent.

Figure 5.

Differences in particular methods - Green area (Respondent 1).

Figure 5.

Differences in particular methods - Green area (Respondent 1).

Figure 6.

Differences in particular methods - Green area (Respondent 2).

Figure 6.

Differences in particular methods - Green area (Respondent 2).

Figure 7.

Differences in particular methods - Orange area (Respondent 1).

Figure 7.

Differences in particular methods - Orange area (Respondent 1).

Figure 8.

Differences in particular methods - Orange area (Respondent 2).

Figure 8.

Differences in particular methods - Orange area (Respondent 2).

Figure 9.

Differences in particular methods - Red area (Respondent 1).

Figure 9.

Differences in particular methods - Red area (Respondent 1).

Figure 10.

Differences in particular methods - Red area (Respondent 2).

Figure 10.

Differences in particular methods - Red area (Respondent 2).

Figure 11.

Resulting differences between assessment methods - Green area.

Figure 11.

Resulting differences between assessment methods - Green area.

Figure 12.

Resulting differences between assessment methods - Orange area.

Figure 12.

Resulting differences between assessment methods - Orange area.

Figure 13.

Resulting differences between assessment methods – Red area.

Figure 13.

Resulting differences between assessment methods – Red area.

Table 2.

Measured body segments and their labelling.

Table 2.

Measured body segments and their labelling.

| Joint |

Movement |

Label |

Joint |

Movement |

Label |

| Neck |

flexion |

N1 |

Lower back |

forward flexion |

LB1 |

| |

extension |

N2 |

|

extension |

LB2 |

| |

lateral flexion right |

N3 |

|

lateral flexion right |

LB3 |

| |

lateral flexion left |

N4 |

|

lateral flexion left |

LB4 |

| |

rotation right |

N5 |

|

rotation right |

LB5 |

| |

rotation left |

N6 |

|

rotation left |

LB6 |

| Right shoulder |

rotation external/ |

RS1 |

Left shoulder |

rotation external/ |

LS1 |

| |

rotation internal |

RS2 |

|

rotation internal |

LS2 |

| |

vertical rotation |

RS3 |

|

vertical rotation |

LS3 |

| |

horizontal rotation external/ |

RS4 |

|

horizontal rotation external/ |

LS4 |

| |

horizontal rotation internal |

RS5 |

|

horizontal rotation internal |

LS5 |

| Right elbow |

flexion/ |

RE1 |

Left elbow |

flexion/ |

LE1 |

| |

extension |

RE2 |

|

extension |

LE2 |

| |

rotation external |

RE3 |

|

rotation external |

LE3 |

| |

rotation internal |

RE4 |

|

rotation internal |

LE4 |

Table 3.

Basic characteristics of respondents.

Table 3.

Basic characteristics of respondents.

| Respondent |

Gender |

Age |

Weight [kg] |

Height [m] |

BMI |

| Proband1 |

F |

23 |

76 |

1,68 |

26,93 |

| Proband2 |

F |

45 |

52 |

1,68 |

18,42 |

| Proband3 |

F |

45 |

81 |

1,68 |

28,70 |

| Proband4 |

M |

46 |

76 |

1,77 |

24,26 |

| Proband5 |

M |

45 |

86 |

1,85 |

25,13 |

Table 4.

Paired t-test result, Green area, Resp1 (α=0.05).

Table 4.

Paired t-test result, Green area, Resp1 (α=0.05).

| Results |

Legislation /Captiv |

Captiv/STN EN |

Legislation/STN EN |

| t-stat |

4.160 |

6.847 |

3.371 |

| p-value |

0.0008 |

0.000005 |

0.0042 |

| Conclusion |

H0 rejected |

H0 rejected |

H0 rejected |

Table 5.

Complete testing results – Respondent I, Respondent II, Respondent III (α=0.05).

Table 5.

Complete testing results – Respondent I, Respondent II, Respondent III (α=0.05).

| Area |

Respondent I |

Respondent II |

Respondent III |

| L vs C |

C vs S |

L vs S |

L vs C |

C vs S |

L vs S |

L vs C |

C vs S |

L vs S |

| Green |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p-value |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.004 |

0.080 |

<0.001 |

| Conclusion |

SD |

SD |

SD |

SD |

SD |

SD |

SD |

N |

SD |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Orange |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p-value |

0.016 |

0.007 |

0.659 |

<0.001 |

0.006 |

0.672 |

0.014 |

0.362 |

0.401 |

| Conclusion |

SD |

SD |

N |

SD |

SD |

N |

SD |

N |

N |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Red |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p-value |

<0.001 |

0.275 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.323 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.372 |

<0.001 |

| Conclusion |

SD |

N |

SD |

SD |

N |

SD |

SD |

N |

SD |

Table 6.

Complete testing results – Respondent IV, Respondent V (α=0.05).

Table 6.

Complete testing results – Respondent IV, Respondent V (α=0.05).

| Area |

Respondent IV |

Respondent V |

| L vs C |

C vs S |

L vs S |

L vs C |

C vs S |

L vs S |

| Green |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p-value |

0.060 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.001 |

0.002 |

<0.001 |

| Conclusion |

N |

SD |

SD |

SD |

SD |

SD |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Orange |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p-value |

<0.001 |

0.006 |

0.469 |

0.020 |

0.003 |

0.798 |

| Conclusion |

SD |

SD |

N |

SD |

SD |

N |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Red |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| p-value |

<0.001 |

0.216 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.405 |

<0.001 |

| Conclusion |

SD |

N |

SD |

SD |

N |

SD |

Table 7.

Percentage weight of total time respondents spend in risk zones in the job.

Table 7.

Percentage weight of total time respondents spend in risk zones in the job.

| Respondent |

Percentage weight of total work activity respondents spend in risk zones in the job [%] |

| Legislation |

Captiv |

STN EN |

| Green |

Orange |

Red |

Green |

Orange |

Red |

Green |

Orange |

Red |

| Resp1 |

67.46 |

20.86 |

11.68 |

43.91 |

10.65 |

45.44 |

25.04 |

23.08 |

51.88 |

| Resp2 |

62.76 |

25.07 |

12.17 |

43.04 |

8.06 |

48.90 |

23.18 |

22.67 |

54.15 |

| Resp3 |

57.20 |

24.30 |

18.50 |

37.78 |

11.68 |

50.54 |

28.27 |

17.78 |

53.94 |

| Resp4 |

59.36 |

23.30 |

17.34 |

46.09 |

6.97 |

46.94 |

28.01 |

18.82 |

53.17 |

| Resp5 |

68.49 |

18.98 |

12.53 |

47.59 |

9.42 |

42.99 |

33.54 |

20.44 |

46.02 |

| Average |

63.05 |

22.50 |

17.92 |

43.68 |

9.36 |

46.96 |

27.61 |

20.56 |

51.83 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).