Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

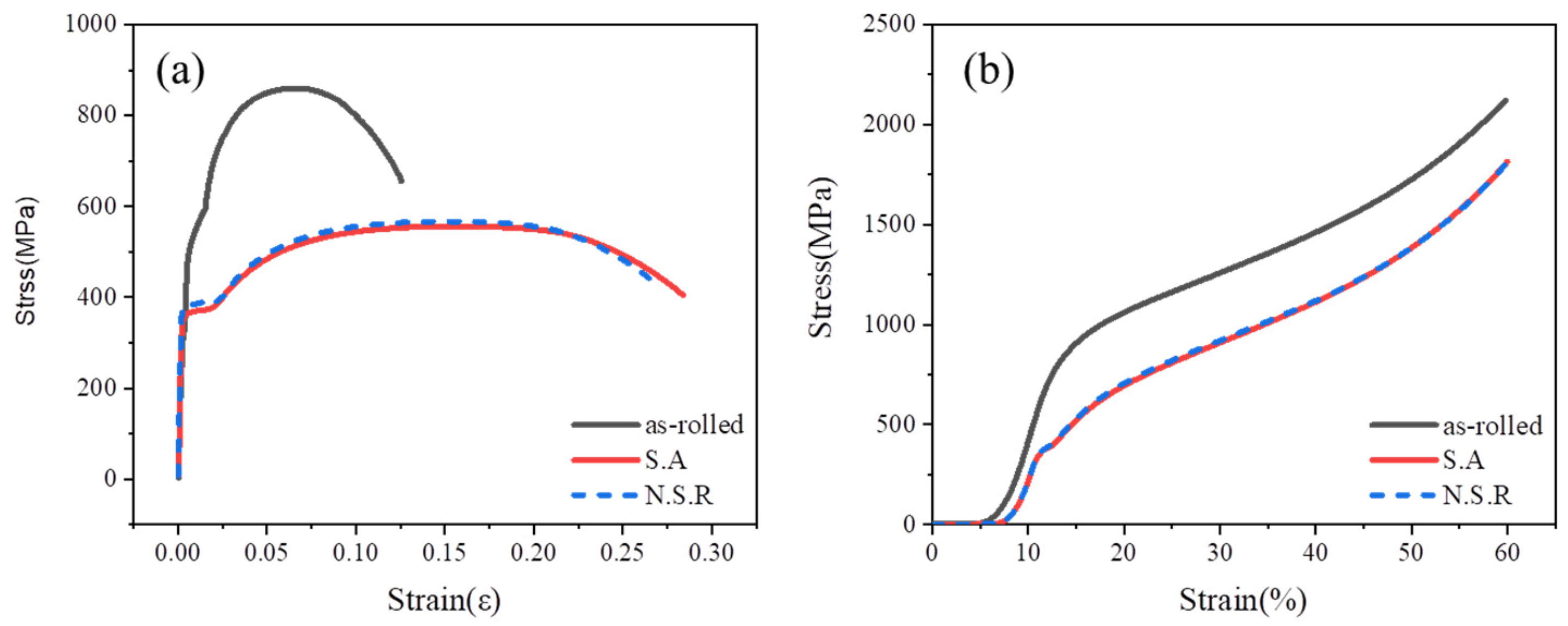

This study developed a new heat treatment method, normalizing & stress relief (N.S.R), to increase productivity compared to spheroidizing annealing (S.A). The influence of different microstructures resulting from these heat treatments was investigated in cold-forged steel. Despite a shorter heat treatment time, the mechanical properties of the N.S.R alloy were found to be similar to those of the S.A alloy. The factors influencing the mechanical properties of the experimental alloys were analyzed using the Hall-Petch equation, and the predicted values closely matched the measured strength of hy-per-eutectoid steels. The primary factors affecting mechanical properties were micro-structure and dislocation density. In the case of the S.A alloy, the microstructure exhibited lower strength due to the spherical cementite structure. In contrast, the N.S.R alloy had lower strength because of a reduced dislocation density. This was achieved by stress-relief heat treatment below the A1 temperature after phase transformation. Based on the mechanical properties, cold forging simulations showed that the effective stress during cold forging of the N.S.R alloy was similar to that of the S.A alloy.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

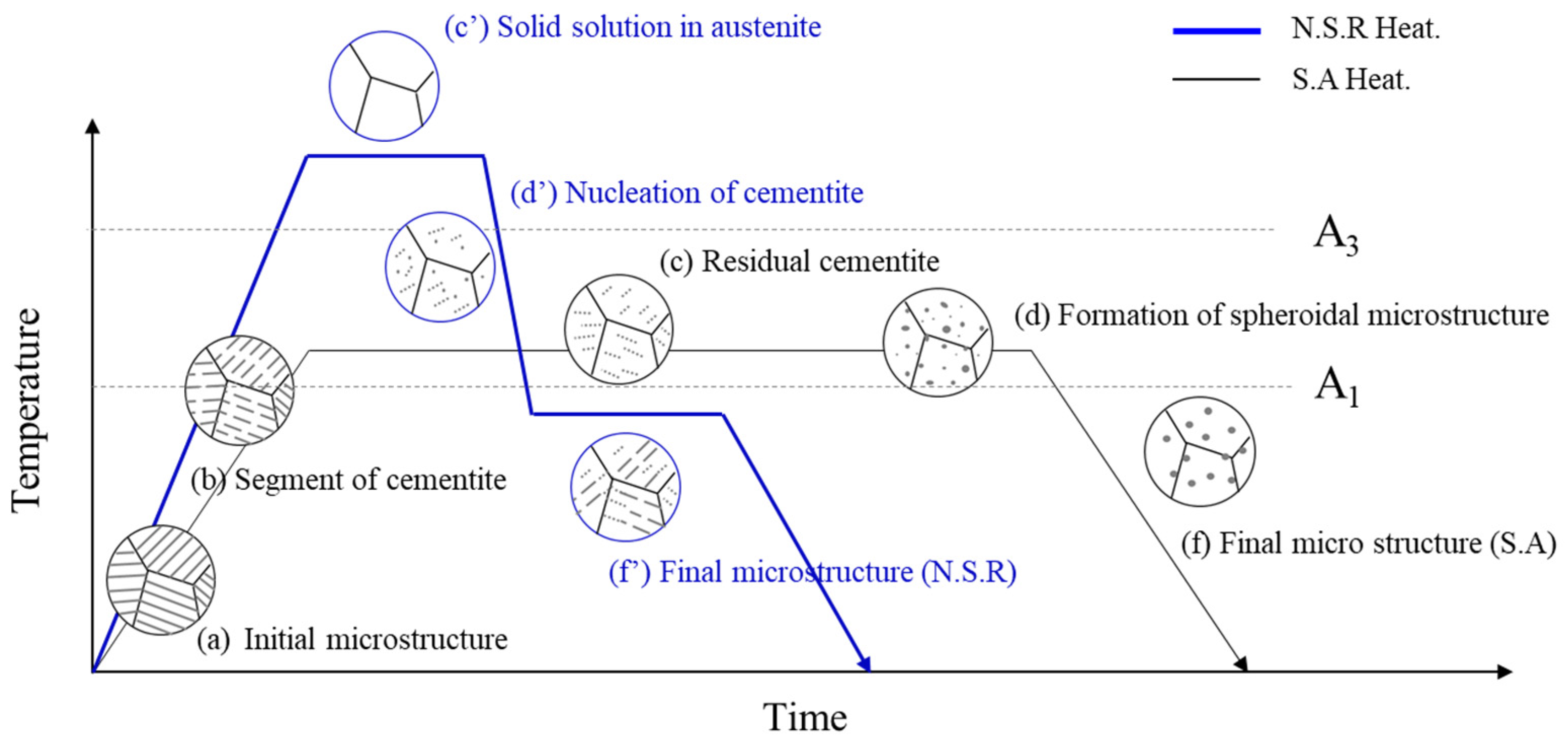

2.1. Development of N.S.R Heat Treat Ment

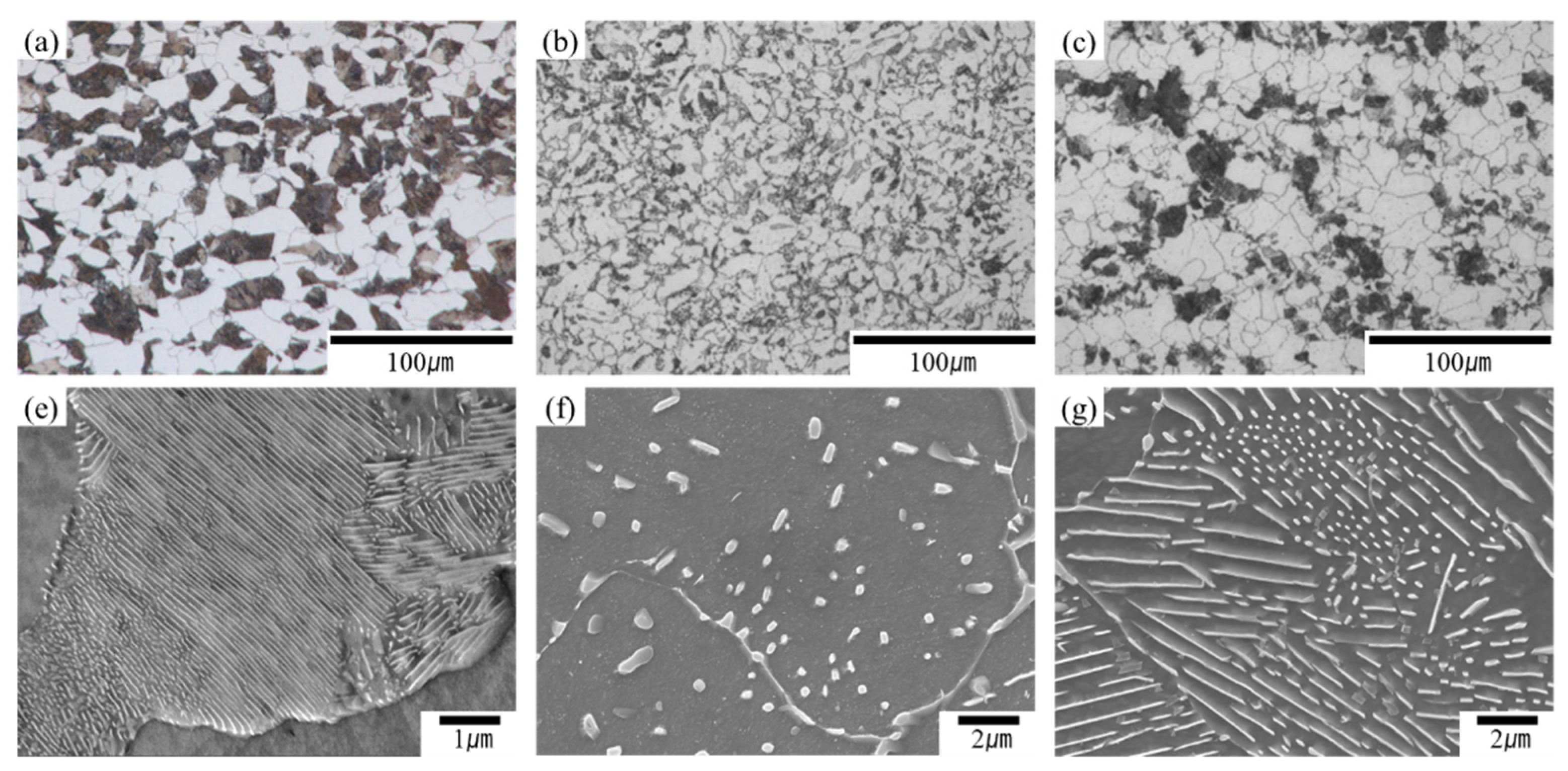

2.2. Microstructures and Mechanical Properties

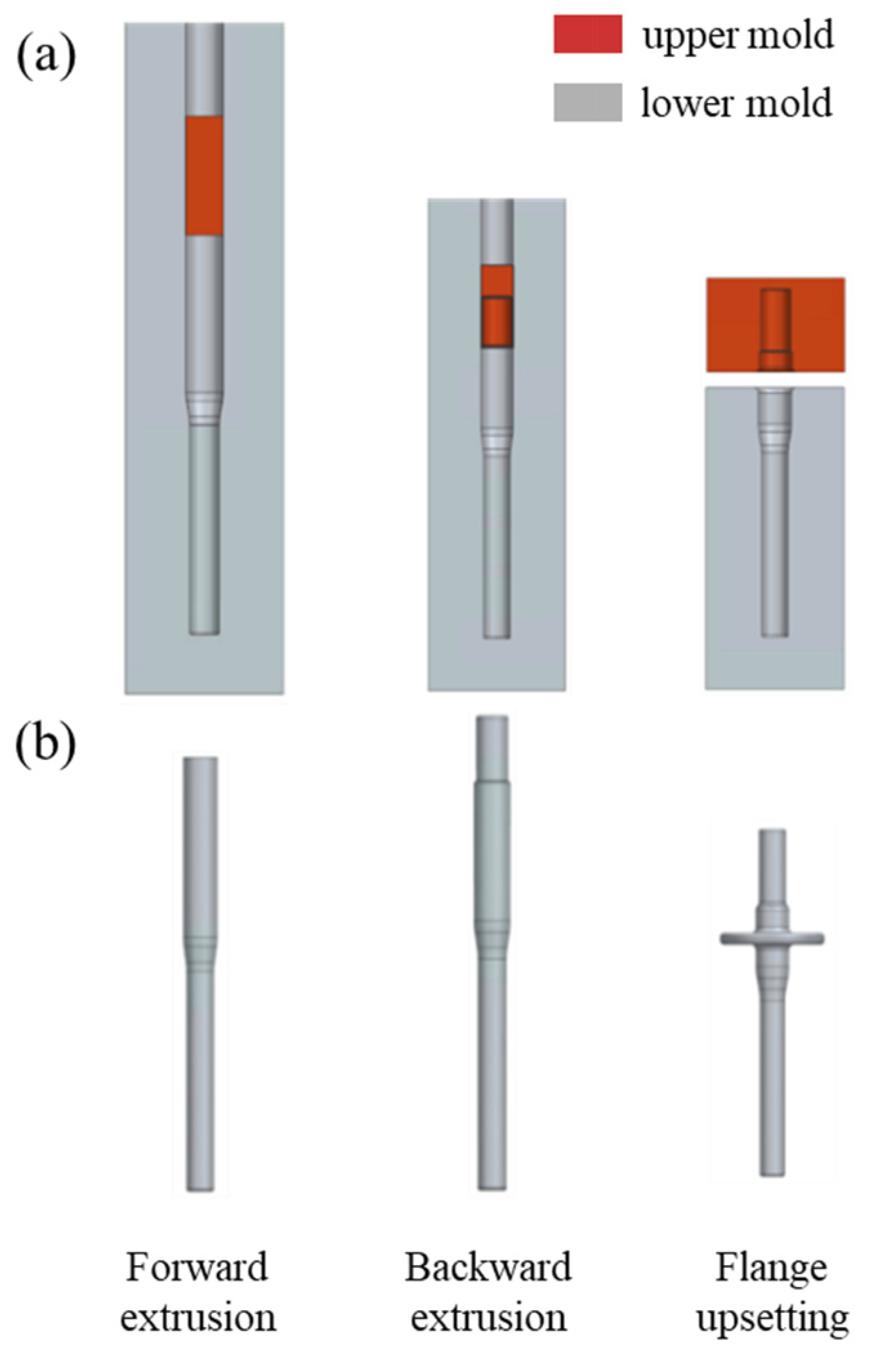

2.3. Analysis of Cold Forging Formability

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructures and Mechanical Properites

3.2. On the Strength Mechanisms

3.3. Analysis of Cold Forging Formability

4. Conclusions

References

- Chaudhury, R.; Sharma, U.; Thapliyal, P. C.; Singh, L. P. Low-CO2 emission strategies to achieve net zero target in cement sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 137466. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Ghosh, A.; Roy, A. Renewable and sustainable materials in automotive industry. Encycl. Renew. Sustain. Mater. 2020, 162–179.

- Han, Z. Y.; Zhang, M. D.; Xu, H. F.; Dong, H.; Cao, W. Q. Research and application of high performance automobile steel. Iron Steel 2016, 51(2), 1.

- Wang, C. Y.; Yang, J.; Chang, Y.; Cao, W. Q.; Dong, H. Development trend and challenge of advanced high strength automobile steels. Iron Steel 2019, 54(2), 1.

- McKelvey, S. A.; Fatemi, A. Surface finish effect on fatigue behavior of forged steel. Int. J. Fatigue 2012, 36(1), 130–145. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Qin, Y.; Chen, J. G.; Choy, C. M. A forging method for reducing process steps in the forming of automotive fasteners. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2018, 137, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Bilbao, O.; Loizaga, I.; Alonso, J.; Girot, F.; Torregaray, A. 42CrMo4 steel flow behavior characterization for high temperature closed dies hot forging in automotive components applications. Heliyon 2023, 9(11), e22256. [CrossRef]

- Douthit, T. J.; Van Tyne, C. J. The effect of nitrogen on the cold forging properties of 1020 steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2005, 160(3), 335–347. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, J. M.; Hosford, W. F. Spheroidization cycles for medium carbon steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2002, 33, 1255–1261. [CrossRef]

- Onodera, S.; Sawai, K. Current cold-forging techniques for the manufacture of complex precision near-net-shapes. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1992, 35, 385–396. [CrossRef]

- Karadeniz, E. Influence of different initial microstructure on the process of spheroidization in cold forging. Mater. Des. 2008, 29(1), 251–256. [CrossRef]

- Kada, O.; Fujita, T.; Hashimura, M. Development of Advanced Analysis System for the Production of Parts with Bar and Wire Rod. Nippon Steel Technical Report 2013, No. 103, pp. 121–126.

- Alza, V. A. Spheroidizing in steels: Processes, mechanisms, kinetic and microstructure—A review. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2021, 18(3), 63–81.

- Hwang, H.; De Cooman, B. C. Influence of the initial microstructure on the spheroidization of SAE 52100 bearing steel. Steel Res. Int. 2016, 87(1), 112–125.

- Vander Voort, G. F.; Roosz, A. Measurement of the interlamellar spacing of pearlite. Metallography 1984, 17(1), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.S.; Ku, T.W. Process Modification and Numerical Simulation for an Outer Race of a CV Joint using Multi-Stage Cold Forging. Transactions of Materials Processing 2014, 23( 4), 211–219. [CrossRef]

- Anand, L.; Gurland, J. Effect of internal boundaries on the yield strengths of spheroidized steels. Metall. Trans. A 1976, 7, 191–197. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, S.; Ramisetti, N. K.; Misra, R. D. K.; Mannering, T.; Panda, D.; Jansto, S. Effect of cooling rate on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Nb-microalloyed steels.Mater. Des., 2007, 460, 335-343. [CrossRef]

- Hall, E. O. Variation of hardness of metals with grain size. Nature 1954, 173(4411), 948–949. [CrossRef]

- O'Donnelly, B. E.; Baker, T. N. Strengthening in low carbon pearlitic steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1986, 84, 131–135. [CrossRef]

- O'Donnelly, B. E.; Reuben, R. L.; Baker, T. N. Quantitative assessment of strengthening parameters in ferrite-pearlite steels from microstructural measurements. Metals Technol. 1984, 11(1), 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, W. B. The effect of grain size on the stress-strain relationship in low-carbon steel. ASM Trans. Quart. 1966, 59(4), 824–846.

- Mintz, B. Importance of ky (Hall-Petch slope) in determining strength of steels. Metals Technol. 1984, 11(1), 265–272.

- Anand, L.; Gurland, J. Effect of internal boundaries on the yield strengths of spheroidized steels. Metall. Trans. A 1976, 7, 191–197. [CrossRef]

- Hall, E. O. The deformation and ageing of mild steel: III discussion of results. Proc. Phys. Soc. Sect. B 1951, 64(9), 747. [CrossRef]

- Dolzhenko, A.; Pydrin, A.; Gaidar, S.; Kaibyshev, R.; Belyakov, A. Microstructure and strengthening mechanisms in an HSLA steel subjected to Tempforming. Metals 2021, 12(1), 48. [CrossRef]

- Ray, K. K.; Mondal, D. The effect of interlamellar spacing on strength of pearlite in annealed eutectoid and hypoeutectoid plain carbon steels. Acta Metallurgica et Materialia 1991, 39(10), 2201–2208. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Timokhina, I.; Pereloma, E. Clustering, nano-scale precipitation and strengthening of steels. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 118, 100764. [CrossRef]

- Modi, O. P.; Desmukh, N.; Mondal, D. P.; Jha, A. K.; Yegneswaran, A. H.; Khaira, H. K. Effect of interlamellar spacing on the mechanical properties of 0.65% C steel. Mater. Charact. 2001, 46(5), 347–352. [CrossRef]

- Speich, G. R.; Schwoeble, A. J.; Leslie, W. C. Elastic constants of binary iron-base alloys. Metall. Trans. 1972, 3, 2031–2037. [CrossRef]

| Chemical composition | C | Si | Mn | Cr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCR420 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.80 | 1.20 |

| Properties | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Young's modulus | GPa | 210 |

| Poisson's ratio | - | 0.3 |

| Density | g/cm3 | 7.85 |

| Thermal expansion coefficient | 1/℃ | 1.2E-05 |

| Mecahnical properties |

Tensile Properties | Compressive Stress (MPa) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y.S1 (MPa) |

U.T.S2 (MPa) |

Elongation (%) |

20% | 40% | 60% | |

| as-rolled | 565 | 842 | 17% | 1,170 | 1,520 | 2,119 |

| S.A | 362 | 556 | 30% | 805 | 1,169 | 1,810 |

| N.S.R | 382 | 567 | 28% | 810 | 1,174 | 1,815 |

| Ky | as-rolled | S.A | N.S.R |

| unit : MPa/㎛1/2 | 601 | 411 | 430 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).