Introduction

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS) is defined by neurogenic upper extremity symptoms due to compression of the neurovascular bundle exiting the thoracic outlet [

1]. 95 % of all TOS cases are neurogenic produced by impingement of the C5 to T1 nerve roots of the plexus brachialis [

2]. This impingement can occur at several sites, however the interscalene triangle due to its closely intertwined anatomy is most frequently affected [

3]. To decompress the irritated brachial plexus, a scalenectomy combined with or without a first rib resection is a common surgical intervention for patients with neurogenic TOS who underwent 4 – 6 months of conservative management without an alleviation of symptoms [

4]. Until now, there is no agreed-upon conservative management for neurogenic TOS and no technique with sufficient long-term pain relief has been described so far [

5]. In 2017, the Cochrane Library postulated that Dexamethasone as a perineural adjunct for peripheral nerve block prolongs both sensory and motor block [

6].

Dexamethasone is an anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid that is often used in clinic to treat peripheral nerve damage due to its capacity to reduce edema in neurologic tissue and alleviation of the consequences of neural inflammation [

7]. However, its mechanisms of actions are still not completely understood. It is tempting to associate the immunosuppressant and potential neurotrophic effects induced by dexamethasone with its actions at the site of nerve compression or injury, which would lead to reduced infiltration of inflammatory cells and production of inflammatory mediators. This hypothesis was investigated in 2012 by

Hongzhi et al. who found, that dexamethasone and vitamin B

12 promoted peripheral nerve repair in a rat model of sciatic nerve injury through the upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [

8]. In 2014,

Xinghong Feng et al. could demonstrate that dexamethasone enhanced sciatic nerve regeneration and function recovery in a rat model of sciatic nerve injury through neuroprotection by restricting CD3-positive cell invasion. In addition, dexamethasone upregulates the GAP-43 expression in the crushed / compressed or injured nerve after 21 days, which is mainly associated with the development and plasticity of the nervous system. H&E staining of sciatic nerves strongly supported the beneficial effect of dexamethasone in axonal regeneration due to reduced edema as well as fewer degraded myelin sheets [

9]. Previous studies also indicated that dexamethasone did not only reduce the extent of demyelination but also had the potential to enhance remyelination [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

The rational of using dexamethasone for TOS is based on its use in Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) and its well-known anti-inflammatory mechanisms [

15,

16,

17,

18].

To further investigate dexamethasone’s effect as a perineural additive, this pilot trial was conducted to evaluate the correlation between a scalene nerve block with dexamethasone perineural and pain relief. The primary aim was to assess the extent and the duration of the pain reduction that can be achieved through the procedure.

Methods

This study was questionnaire-based and has been approved by the institutional review board of the Medical University of Graz beforehand (with the registration number: EK 34-449 ex 21/22) and written informed consent has been obtained from all subjects.

Patient selection:

This pilot trial was carried out between October 2021 and January 2023 at the Division of Plastic, Aesthetic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery of the Medical University of Graz, Austria.

Patients were deemed eligible for the study, when they fulfilled the following criteria:

Clinical signs of nTOS without pathologic findings in electroneurography or imaging studies (disputed nTOS) OR

Established diagnosis of nTOS with pathologies in imaging studies (cervical rib, aberrant scalene muscle fibres, pathological flow profile of subclavian artery) as bridging therapy until surgery OR

Recurrent nTOS symptoms after prior surgery

In the first patient group, the interscalene nerve block besides pain relief was also utilized as diagnostic tool to confirm the suspected diagnosis of an nTOS, whereas in the other two groups, the nerve block was done for pain therapy only. Patients with bilateral nTOS were furthermore evaluated as two separate cases. Patients were excluded in the case of isolated vascular TOS or when there was known drug intolerance to Ropivacaine or Dexamethasone.

Prior clinical examination, electroneurography and imaging studies:

Prior to enrolment, all patients underwent a mandatory set of clinical tests and imaging studies. Clinical examination encompassed the “TOS stress test” (90° shoulder abduction, elbow and wrist extended, head tilted to the contralateral side), which was deemed positive if this provoked the typical symptoms (pain exacerbation and numbness of the affected limb). Electroneurography of the median and ulnar nerves was performed in all patients to rule out additional nerve entrapment syndromes. A plain radiograph of the cervical spine was performed to detect any bony anomalies at the level of the thoracic outlet, such as a cervical rib or enlarged transverse processes. MRI of the cervical spine was done to rule out foramen stenoses with root compression. Furthermore, all patients received high-resolution ultrasound of the brachial plexus to detect any aberrant muscle fibres or fibrous strands surrounding the neurovascular structures. When clinically indicated, additional imaging studies were carried out, i.e. an MRI in the case of a Pancoast tumour compressing the brachial plexus or a CT scan to clarify the cervicothoracic junction.

Interscalene nerve block:

The interscalene nerve block was carried out ultrasound-guided under sterile conditions. For the intervention, the patient was placed in lateral position with the affected side up and head tilted to the contralateral side. Then a 14-gauge needle was advanced into the interscalene triangle under continuous visualization and 14 ml of 7.5mg/ml Ropivacaine and 6 mg Dexamethasone were injected perineural. The correct placement of the infiltration volume around the nerve roots was then visually confirmed with ultrasound. A transient paralysis of the affected arm approximately 30 minutes after the intervention including complete sensory loss at the palm of the hand served as clinical confirmation for the correct infiltration. In all patients paralysis and sensory loss resolved 6 to 8 hours after the intervention [

19,

20]. In patients with bilateral nTOS, the intervention was carried out on two consecutive days.

Assessment of pain levels, paraesthesia, numbness and weakness:

Before the intervention the patients underwent a detailed anamnesis as well as a clinical examination. The current pain level in relaxed position (Pmin) and under stress (Pmax) was evaluated using the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NRS – 10 point Likert-scale) by asking ‘What number would you rate your pain, if zero is no pain and ten is the worst imaginable pain?’. In addition, patients were asked whether the experienced paraesthesia, numbness or weakness (yes or no) of the affected upper limb.

Quick-DASH (quick Disability of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand) Score

The Quick-DASH score is a questionnaire that assesses upper limb function in daily life. Higher scores are tantamount to higher disability. The score was assessed at baseline and at each follow-up visit. In patients with bilateral symptoms, the score was evaluated for each arm independently.

Follow-up visits:

All relevant parameters were collected at baseline, as well as 2, 6, 12, and 24 weeks after the interscalene nerve block. Each follow-up-visit also included a clinical examination to detect early signs of symptom recurrence. Patients with the first manifestation of nTOS and recurrent pain 6 weeks after the intervention were scheduled for surgery, whereas patients with ongoing symptom relief remained in the study.

Statistical Analysis

The data were expressed as median with interquartile range and analysed using the SPSS 29.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) software. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all patients’ characteristics, results of minimum and maximum pain scores as well as Quick-DASH and SF12 scores. Due to the small sample size, values were expressed as median with minimum and maximum. For inductive analysis, the Wilcoxon signed rank test and the t-test for paired samples was used and baseline values were compared to values at each follow-up visit. A value of P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

In total, 21 upper limbs (18 female, 3 male) were included into the study. The median age was 37 years (19 – 45) and the median pain anamnesis was 29 (9-120) months. In 10 cases the right and in 11 cases the left arm was affected. There were 12 cases of true and 9 of disputed nTOS. At baseline, weakness, paraesthesia and clumsiness were reported in all examined 21 arms. Between 6 and 12 weeks follow-up, a total of 12 limbs dropped out of the study due to surgery. 5 patients of them had a true nTOS and were planned for surgery right from the beginning (pain bridging). The remaining 7 patients had a disputed nTOS with pain recurrence after 6 weeks and were therefore scheduled for surgery.

Table 1 provides all relevant clinical data of the patient collective.

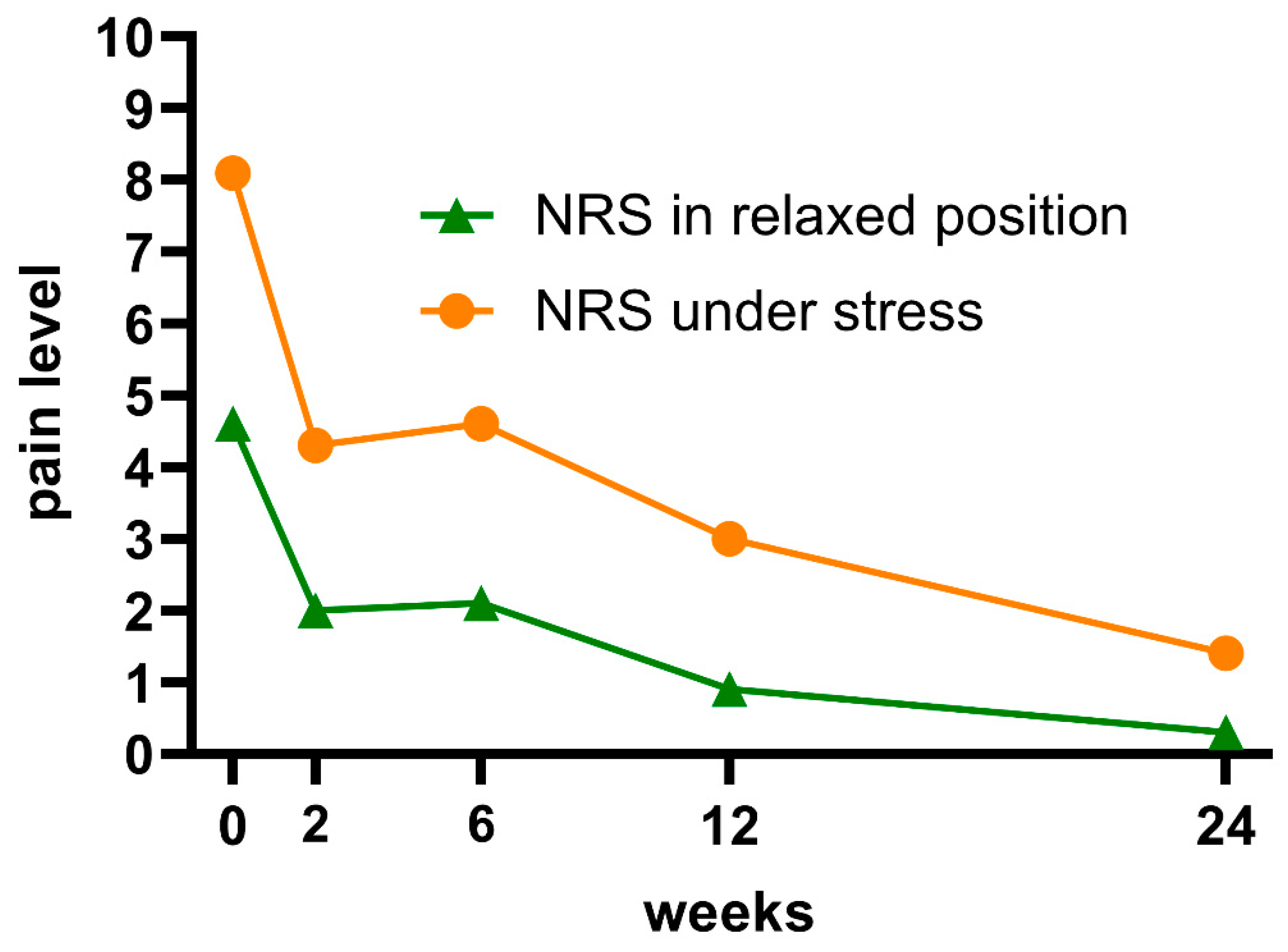

Pain levels by NRS

At baseline, the reported mean minimum pain level was 4.6 (1 – 8) and the maximum pain level was 8.1 (3 – 10).

Two weeks after the scalene nerve block, the mean minimum pain level in relaxed position was 2.0 (0 – 6) (p < 0.001, n = 21); after six weeks 2.1 (0 – 7) (p < 0.001, n = 21); after 12 weeks 0.9 (0 – 3) (p = 0.011, n = 9); after 24 weeks 0.3 (0 – 2) (p = 0.007, n = 9).

Two weeks after the scalene nerve block, the mean maximum pain level under stress was 4.3 (0 – 7) (p < 0.001, n = 21); after six weeks 4.6 (0 – 8) (p < 0.001, n = 21); after 12 weeks 3.0 (0 – 6) (p = 0.028, n = 9) and after 24 weeks 1.4 (0 – 4) (p = 0.007, n = 9).

(Figure 1 – Pain levels by NRS)

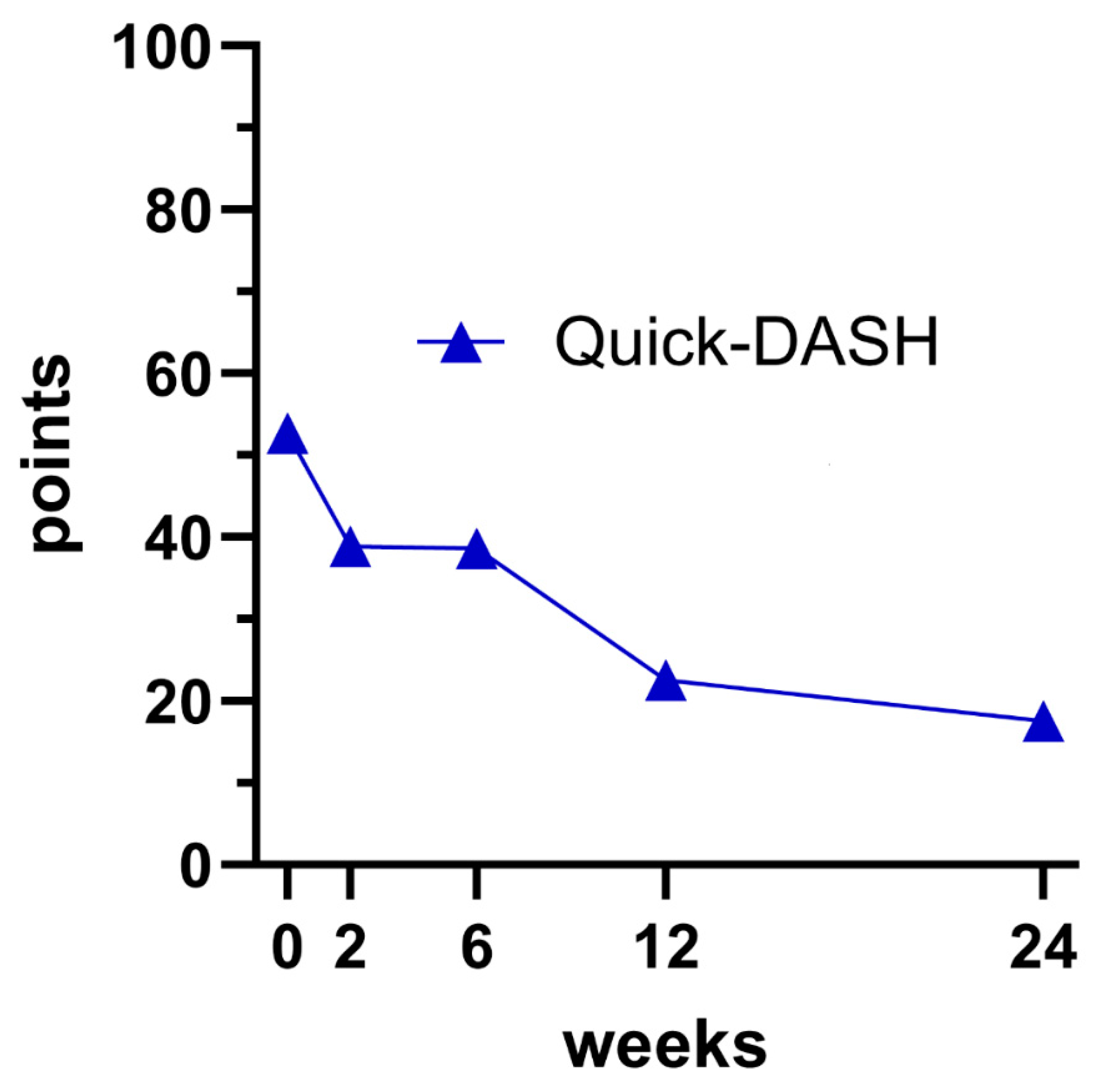

Quick-DASH

At baseline, the reported mean Quick-DASH score was 52.7 (25.0 – 86.4).

Two weeks after the scalene nerve block, the mean Quick-DASH was 38.9 (0 – 80.0) (p < 0.001, n = 21); after six weeks 38.6 (0 – 72.7) (p < 0.001, n = 21); after 12 weeks 22.5 (0 – 38.6) (p = 0.011, n = 9) and after 24 weeks 17.5 (0 – 29.5) (p = 0.008, n = 9).

(Figure 2 – Quick-DASH)

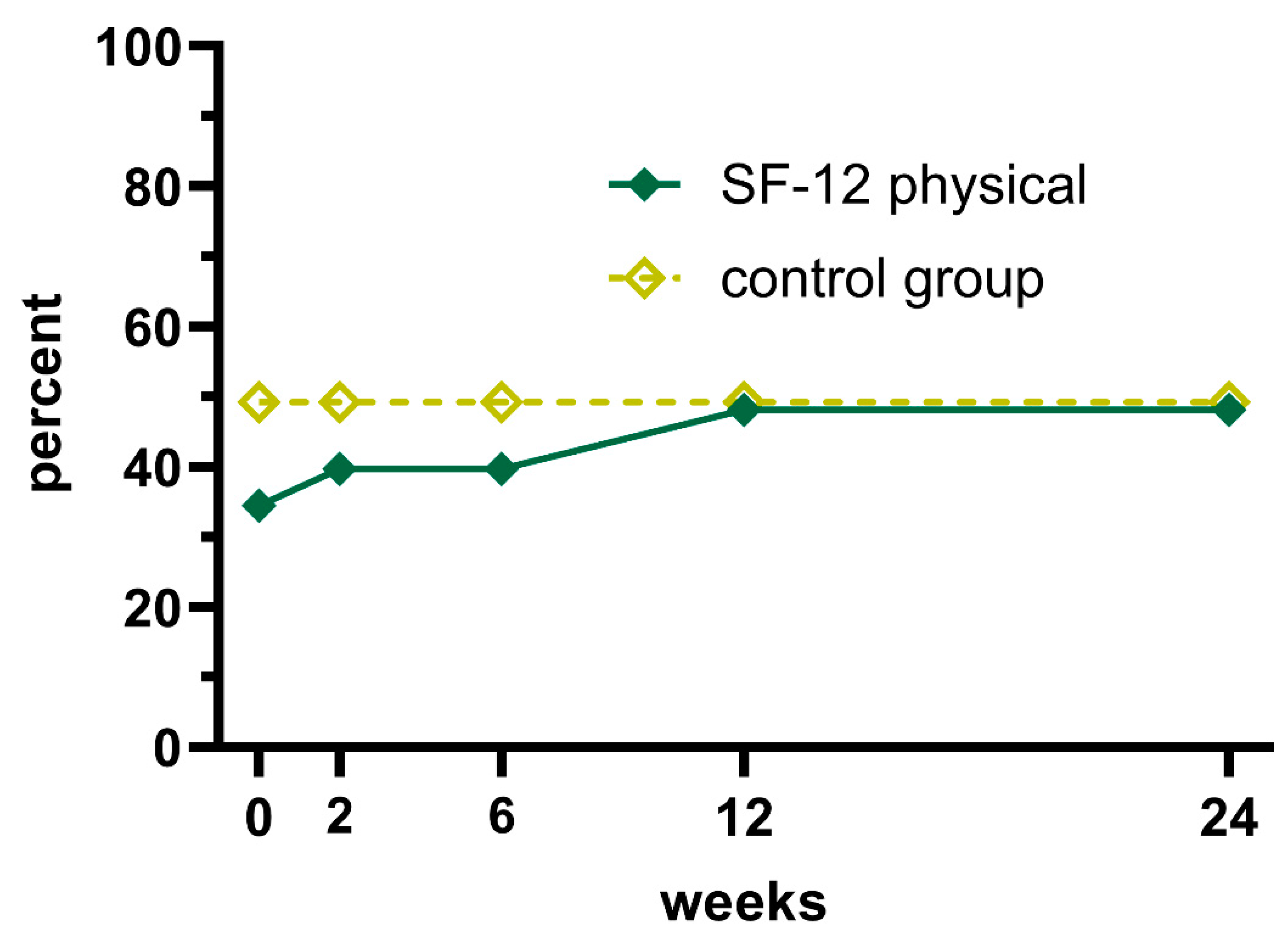

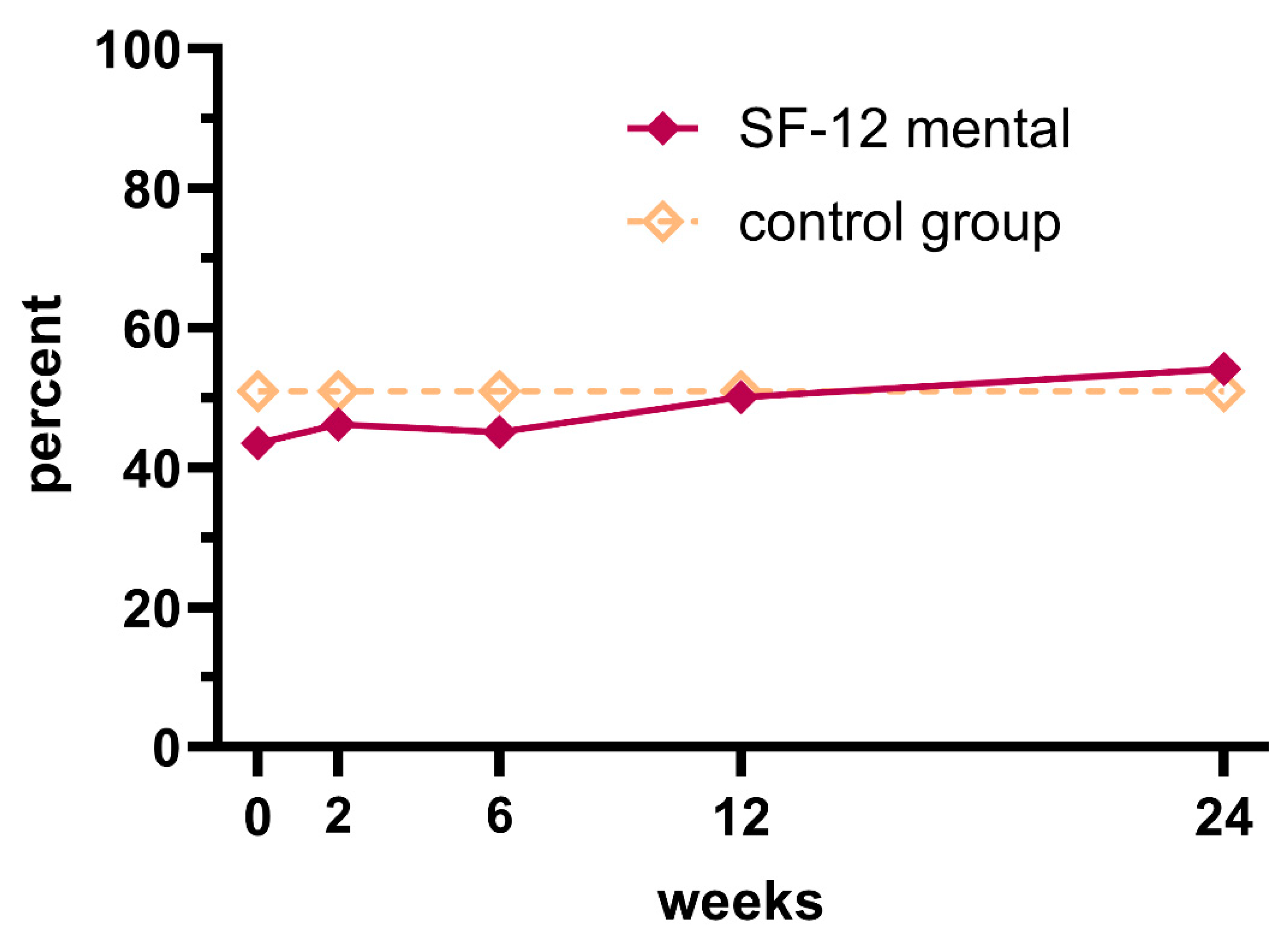

SF-12

At baseline, the reported mean physical SF-12 score was 34.4 (18.2 – 46.9) and the mean mental SF-12 score was 43.5 (31.7 – 59.8).

Two weeks after the scalene nerve block the mean physical SF-12 score was 39.7 (26.9 – 56.9) (p = 0.019, n = 21); after six weeks 39.7 (26.9 – 56.8) (p = 0.039, n = 21); after 12 weeks 48.2 (39.0 – 56.6) (p = 0.021, n = 9) and after 24 weeks 51.0 (39.9 – 56.6) (p = 0.034, n = 9).

(Figure 3 – physical SF-12)

Two weeks after the scalene nerve block the mean mental SF-12 score was 46.2 (28.3 – 61.3) (p = 0.258, n = 22); after six weeks 45.1 (29.0 – 60.6) (p = 0.986, n = 22); after 12 weeks 58.0 (32.8 – 60.8) (p = 0.593, n = 9) and after 24 weeks 55.9 (40.5 – 60.8) (p = 0.026, n = 9).

(Figure 4 – mental SF-12)

Key findings

The median minimum pain level was reduced by 54.3 % after 6 weeks (n = 21) and by 93.5 % after 24 weeks (n = 9).

The median maximum pain level was reduced by 43,2 % after 6 weeks (n = 21) and by 82.7 % after 24 weeks (n = 9).

The median Quick-DASH score was reduced by 26.8 % after 6 weeks (n = 21) by 66.8 % after 24 weeks (n = 9).

The median physical SF-12 score was increased by 15.4 % after 6 weeks (n = 21) and by 39.8 % after 24 weeks (n = 9).

The median mental SF-12 score was increased by 3.7 % after 6 weeks (n = 21) and by 24.1 % after 24 weeks (n = 9).

Discussion

A scalene nerve block was performed in 21 upper limbs with true and disputed nTOS. Detailed examination of the pain level showed a significant pain reduction in the whole trial period (24 weeks), even in every single week. The initial mean value of the minimum pain (Pmin0) was reduced by 93.5 % after 24 weeks (Pmin24). Reflecting that, the initial mean value of the maximum pain (Pmax0) was also reduced by 82.7 % after 24 weeks (Pmax24). These results are in line with the studies, which verified that interscalene brachial plexus blocks with dexamethasone perineural decrease significantly opioid consumptions and the incidence of rebound pain after shoulder surgery [

22,

23]. Other studies verified a significant pain reduction in patients with radiculopathy after selective nerve root blocks with dexamethasone as an adjunct [

24,

25]. A case report of Sung Joon Chung et al. reported a patient who underwent deep tissue massage which concluded in an acute cervical radiculopathy due to C5 and C6 nerve root compression and inflammatory reactions around it. Hence, the patient got an ultrasound - guided C5 and C6 nerve root block twice, with 0.25 % lidocaine and 20 mg dexamethasone. After 24 weeks, the patient’s shoulder and wrist strength had recovered significantly [

26]. Studies investigating CTS and local injections with dexamethasone also demonstrated a significant pain reduction [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Another important finding of this study was the improvement of DASH-Scores over time. We were able to demonstrate that perceived impairment of the affected upper limb decreased significantly in patients with long-lasting effect greater than 12 weeks of the scalene nerve block. To underline these results, a study from

Diner et al. showed a significant re-gain of function of the upper extremity and improvement of DASH-Scores after 12 weeks in patients who underwent TOS-surgery with decompression of the brachial plexus [

27]. In addition, a study from

Ammi et al. evaluated the quality of life after TOS surgery with 3, 6 and 12 months follow-ups using the Quick-DASH and SF-12 questionnaire. The improvement of DASH became statistically significant at 3, 6 and 12 months which is in line with the results of our study [

28].

Furthermore, health related quality of life improved significantly on the SF-12 physical scale from two weeks after the nerve block onwards. The effect was less evident on the mental scale of the SF-12, where significant results were only seen 24 weeks after the infiltration after more than half of the study population dropped out. A study from

Al Rstum et al. demonstrated the same tendencies with the mental scale of the SF-12, which did not improve over the time after TOS-surgery. However, the physical scale of the SF-12 improved linearly with time from surgery regardless of etiology of TOS [

29]. Another study from

Chang et al. showed the same tendencies of the quality of life after TOS-surgery, evaluated with the SF-12 questionnaire 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after surgery [

30]. In 2012,

Rochlin et al. investigated the quality of life after TOS-surgery with the mean follow-up of 44.7 months and concluded that there is no significant difference in the SF-12 scores comparing the long-term and short-term follow-up. Regarding their results, patient factors, particularly comorbidities and opioid use, are more significant relevant for the long-term quality of life than a preoperative scalene nerve block [

31].

As the drop-out group of 12 patients 6 weeks after infiltration constitutes more than half of the initial study population, we would like to give more insight into this group. First of all, 6 patients out of 12 had an objective anatomical compression of the plexus brachialis (e.g. an accessory cervical rib or an enlarged transverse processus) and were either way scheduled for surgery. Thus the scalene nerve block was meant to be a pain bridging in the first place. The remaining 6 patients (without an objective finding) had a pain recurrence after 6 weeks and were also scheduled for surgery. This could be explained by anatomical abnormalities (e.g. strong ligaments) which can not be visualised but still compress the plexus brachialis constantly. Another potential factor, which could distinguish these patients from the study-finishers (n = 9) is the long pain anamnesis with 84 months (12-120) (

Table 1) and a CRPS II as a secondary diagnosis. Furthermore, the drop-out group had a minimum pain level after 6 weeks with 3.0 (0 – 7) and a maximum pain level with 6.0 (3 – 8). In comparison, the study-finishers had a minimum pain level after 6 weeks with 0.9 (0 – 4) and a maximum pain level with 2.8 (0 – 6). These results show a significant difference between the drop-out group and the study-finishers.

Taking all these findings into consideration, it is likely that a scalene nerve block with dexamethasone perineural leads to pain relief in our patients with nTOS. While all patients experienced a short-term pain relief, some patients even experienced a long-lasting effect after the scalene nerve block. Based on the findings of this pilot trial, it seems as if the scalene nerve block could even represent a definitive therapy for some patients with nTOS, whereas some patients might only experience short-term symptom alleviation.

Strengths and limitations

We assume that this is the first study that demonstrates the pain-reducing effect of dexamethasone perineural as an adjunct in a plexus brachialis block in patients with nTOS.

The strengths of this pilot trial are the prospectively collected data, a large patient collective (n = 21) for this rare peripheral neuropathy as well as the significant results even after a drop-out of about 50 % of the patients between the 6- and 12-week follow-up.

Limitation of this study is the absence of a control group and hence no randomization protocol. However, due to the many variations of symptomatic TOS, a much larger patient collective would be necessary. Furthermore, the number of dropper-outs was fairly high. This was on the one hand due to patients being scheduled for surgery in the first place and on the other due to a recurrence of symptoms as early as six weeks infiltration.

Conclusion

The scalene nerve block with Ropivacaine and Dexamethasone seems to be an effective short-term pain therapy in patients with nTOS, irrespective of evident anatomic anomalies. In addition, the nerve block might constitute an effective long-term pain therapy in some patients with disputed nTOS. Furthermore, the scalene nerve block seems to be a feasible method to verify the diagnosis of nTOS in disputed cases aiding in decision making for and against surgical decompression of the thoracic outlet.

Author contributions

W.G. conceived the study and supervised the project. L.M. W. examined the patients prior and after the intervention, analysed the data and took the lead in writing. C.S. aided in the examination of patients and provided critical feedback. A.F. performed the intervention on the patients. All authors provided feedback and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Hooper TL, Denton J, McGalliard MK, Brismée JM, Sizer PS. Thoracic outlet syndrome: A controversial clinical condition. Part 1: Anatomy, and clinical examination/diagnosis. Vol. 18, Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy. 2010.

- Jones MR, Prabhakar A, Viswanath O, Urits I, Green JB, Kendrick JB, et al. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Pain Ther. 2019;8(1). [CrossRef]

- Stewman C, Vitanzo PC, Harwood MI. Neurologic thoracic outlet syndrome: Summarizing a complex history and evolution. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2014;13(2).

- Burt BM. Thoracic outlet syndrome for thoracic surgeons. Vol. 156, Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2018.

- Vanti C, Natalini L, Romeo A, Tosarelli D, Pillastrini P. Conservative treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome: A review of the literature. Vol. 43, Europa Medicophysica. 2007.

- Pehora C, Pearson AME, Kaushal A, Crawford MW, Johnston B. Dexamethasone as an adjuvant to peripheral nerve block. Vol. 2017, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017.

- Sehmbi H, Brull R, Ceballos KR, Shah UJ, Martin J, Tobias A, et al. Perineural and intravenous dexamethasone and dexmedetomidine: network meta-analysis of adjunctive effects on supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Vol. 76, Anaesthesia. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sun H, Yang T, Li Q, Zhu Z, Wang L, Bai G, et al. Dexamethasone and vitamin B12 synergistically promote peripheral nerve regeneration in rats by upregulating the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8(5). [CrossRef]

- Feng X, Yuan W. Dexamethasone enhanced functional recovery after sciatic nerve crush injury in rats. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015. [CrossRef]

- Allodi I, Udina E, Navarro X. Specificity of peripheral nerve regeneration: Interactions at the axon level. Vol. 98, Progress in Neurobiology. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Steinman L. Elaborat[1] L. Steinman, ‘Elaborate interactions between the immune and nervous systems’, Nature Immunology, vol. 5, no. 6. 2004, doi: 10.1038/ni1078.e interactions between the immune and nervous systems. Vol. 5, Nature Immunology. 2004.

- Zochodne DW. The microenvironment of injured and regenerating peripheral nerves. Vol. 9, Muscle & nerve. Supplement. 2000.

- Zhu TS, Glaser M. Neuroprotection and enhancement of remyelination by estradiol and dexamethasone in cocultures of rat DRG neurons and Schwann cells. Brain Res. 2008;1206. [CrossRef]

- Modrak M, Talukder MAH, Gurgenashvili K, Noble M, Elfar JC. Peripheral nerve injury and myelination: Potential therapeutic strategies. Vol. 98, Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wang PH, Tsai CL, Lee JS, Wu KC, Cheng KI, Jou IM. Effects of topical corticosteroids on the sciatic nerve: An experimental study to adduce the safety in treating carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2011;36(3). [CrossRef]

- Amirjani N, Ashworth NL, Watt MJ, Gordon T, Chan KM. Corticosteroid iontophoresis to treat carpal tunnel syndrome: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Muscle Nerve. 2009;39(5). [CrossRef]

- Mathew MM, Gaur R, Gonnade N, Asthana SS, Ghuleliya R. Efficacy of Ultrasound-Guided Particulate Versus Nonparticulate Steroid Injection in Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: An Open-Label Randomized Control Trial. Cureus. 2022; [CrossRef]

- Hussain J, Saqib M, Khan N, Khan S, Jan F, Iqbal MS. Frequency of Local Treatment in Carpal Tunnel Syndrome during Pregnancy. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2021;15(7). [CrossRef]

- Renes SH, Spoormans HH, Gielen MJ, Rettig HC, Van Geffen GJ. Hemidiaphragmatic paresis can be avoided in ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34(6). [CrossRef]

- Renes SH, Rettig HC, Gielen MJ, Wilder-Smith OH, Van Geffen GJ. Ultrasound-guided low-dose interscalene brachial plexus block reduces the incidence of hemidiaphragmatic paresis. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34(5). [CrossRef]

- Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998 Nov;51(11):1171–8.

- Woo JH, Lee HJ, Oh HW, Lee JW, Baik HJ, Kim YJ. Perineural dexamethasone reduces rebound pain after ropivacaine single injection interscalene block for arthroscopic shoulder surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2021;46(11). [CrossRef]

- Morita S, Oizumi N, Suenaga N, Yoshioka C, Yamane S, Tanaka Y. Dexamethasone added to levobupivacaine prolongs the duration of interscalene brachial plexus block and decreases rebound pain after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(9). [CrossRef]

- Shahien R, Beiruti Wiegler K, Dekel L, Sharabi-Nov A, Abu Saleh S. Retrospective study assessing the efficacy of i.v. dexamethasone, SNRB, and nonsteroidal treatment for radiculopathy. Med U S. 2022;101(28).

- Balakrishnamoorthy R, Horgan I, Perez S, Steele MC, Keijzers GB. Does a single dose of intravenous dexamethasone reduce Symptoms in Emergency department patients with low Back pain and RAdiculopathy (SEBRA)? A double-blind randomised controlled trial. Emerg Med J. 2015;32(7). [CrossRef]

- Chung SJ, Soh Y. Acute cervical radiculopathy after anterior scalene muscle massage: A case report. Med U S. 2023;102(15). [CrossRef]

- Diner C, Mathieu L, Vandendries C, Oberlin C, Belkheyar Z. Elective brachial plexus decompression in neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2023 Feb;42(1):9–14. [CrossRef]

- Ammi M, Hersant J, Henni S, Daligault M, Papon X, Abraham P, et al. Evaluation of Quality of Life after Surgical Treatment of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 2022 Sep;85:276–83. [CrossRef]

- Al Rstum Z, Tanaka A, Sandhu HK, Miller CC, Saqib NU, Besho JM, et al. Differences in quality of life outcomes after paraclavicular decompression for thoracic outlet syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2020 Oct;72(4):1421–6. [CrossRef]

- Chang DC, Rotellini-Coltvet LA, Mukherjee D, De Leon R, Freischlag JA. Surgical intervention for thoracic outlet syndrome improves patient’s quality of life. J Vasc Surg. 2009 Mar;49(3):630–7. [CrossRef]

- Rochlin DH, Gilson MM, Likes KC, Graf E, Ford N, Christo PJ, et al. Quality-of-life scores in neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome patients undergoing first rib resection and scalenectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2013 Feb;57(2):436–43. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).