Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

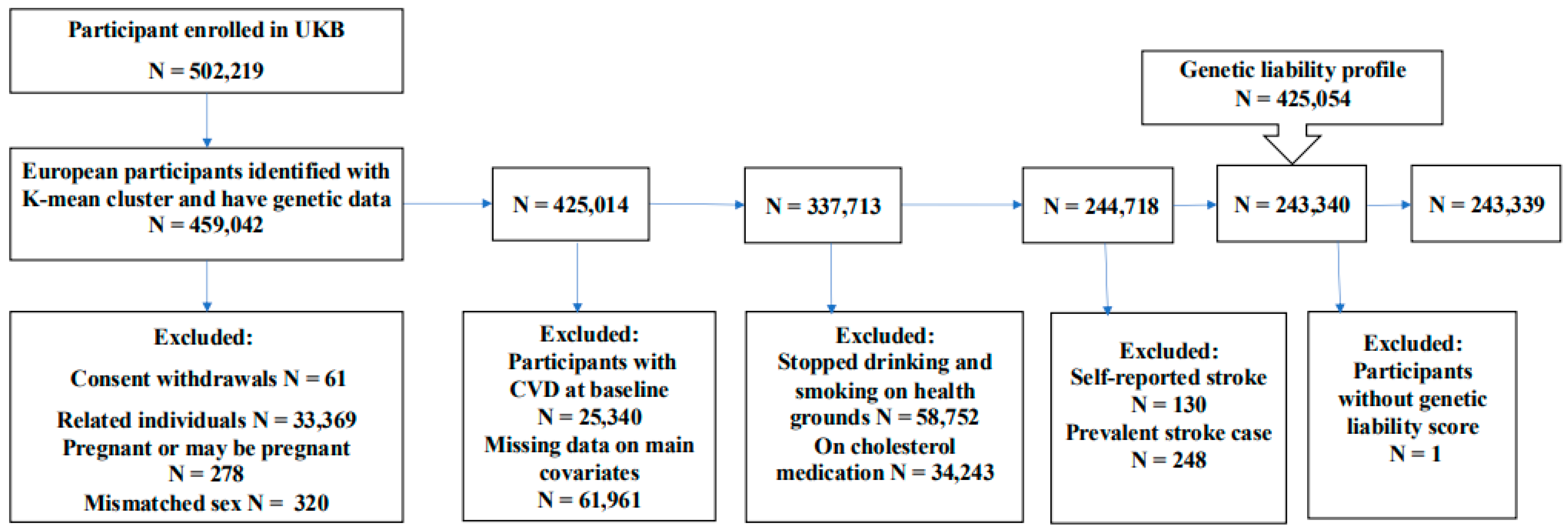

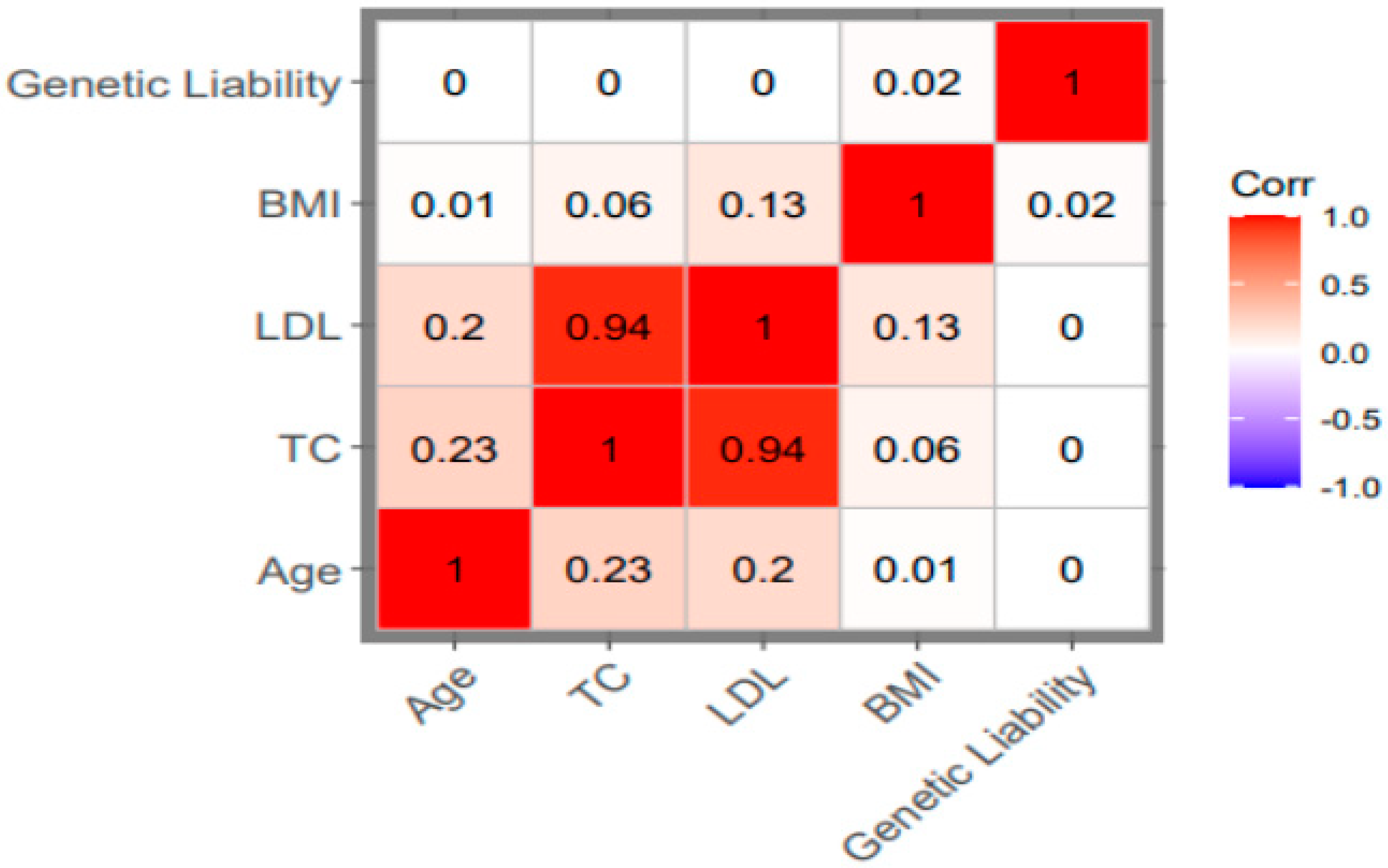

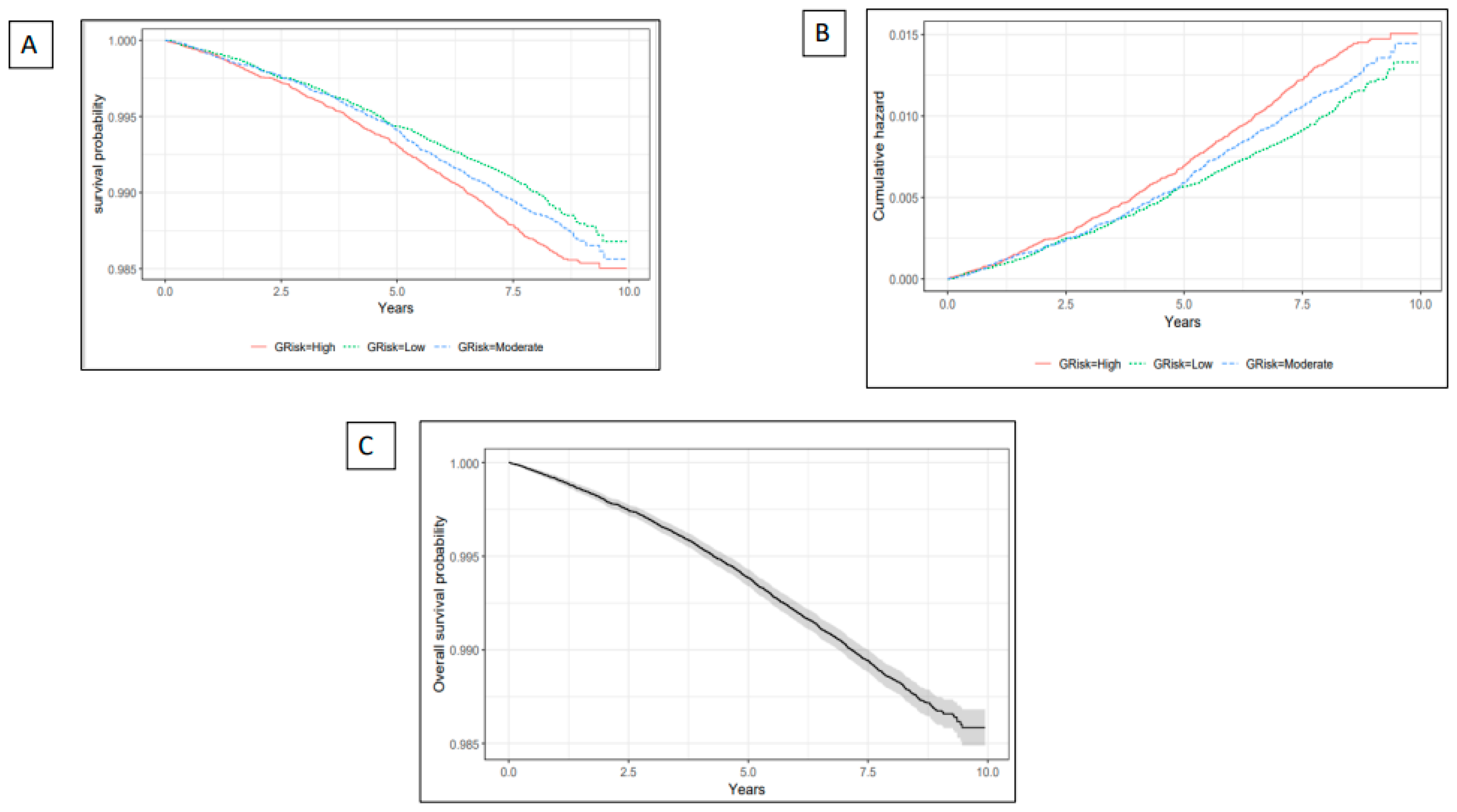

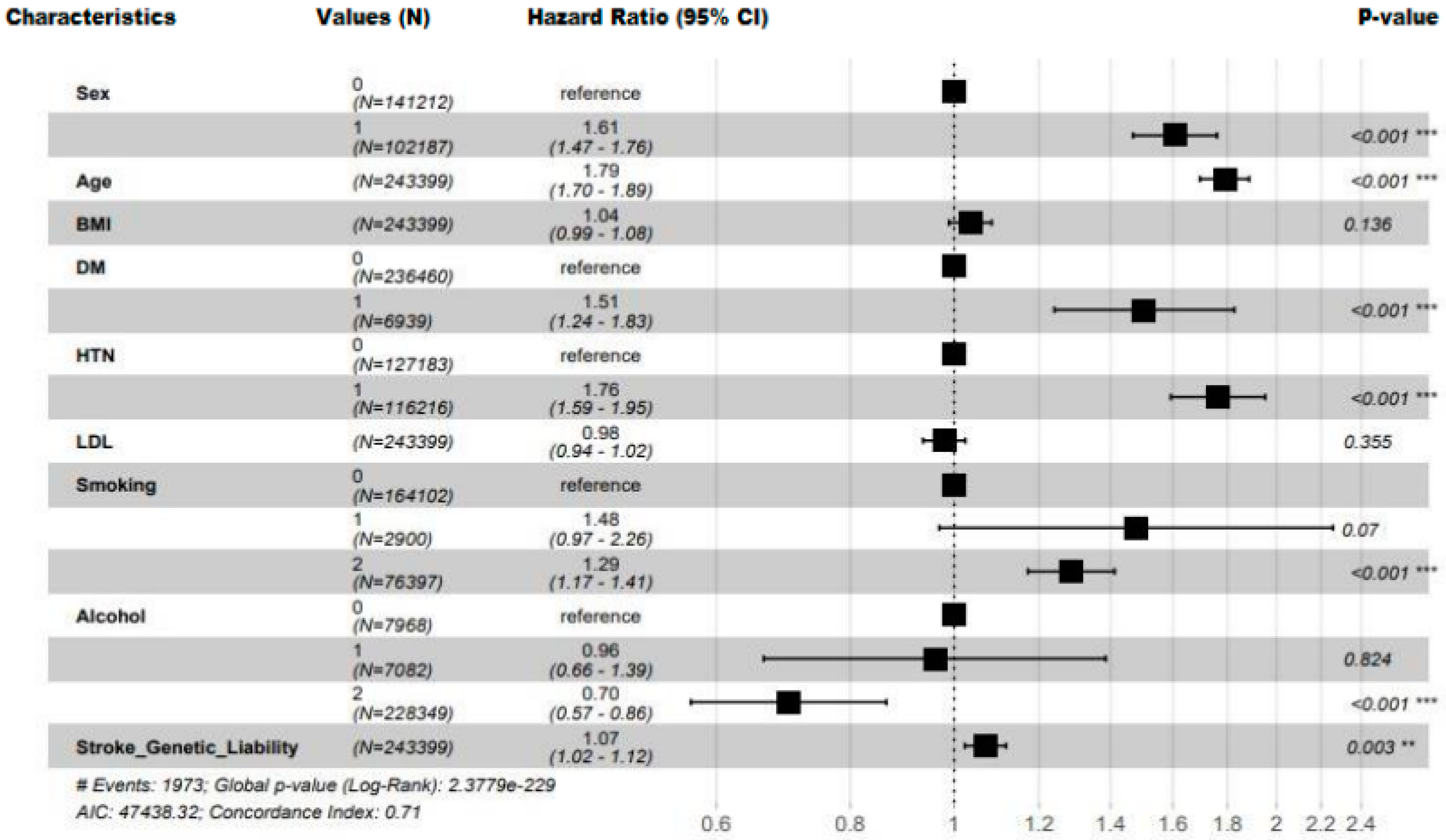

Background and objective: Stroke is one of the leading causes of mortality and long-term disability in adults over 18 years of age globally and its increasing incidence has become a global public health concern. Accurate stroke prediction is highly valuable for early intervention and treatment. Previous studies have utilized statistical and machine learning techniques to develop stroke prediction models. Only a few have included genome-wide stroke genetic liability and evaluated its predictive values. This study aimed to assess the added predictive value of genetic liability in the prediction of the risk of stroke. Materials and methods: The study included 243,339 participants of European ancestry. Stroke genetic liability was constructed using previously identified genetic variants associated with stroke by the MEGASTROKE project through genome-wide association studies (GWAS). In our study, we built four predictive models with and without stroke genetic liability in the training set: Cox proportional hazard (Coxph), Gradient boosting model (GBM), Decision tree (DT), and Random Forest (RF) to estimate time-to-event risk for stroke. We then assessed their performances in the testing set. Results: Each unit (standard deviation) increase in genetic liability increases the risk of incident stroke by 7% (HR = 1.07, 95% CI = 1.02, 1.12, P-value = 0.0030). The risk of stroke was greater in the higher genetic liability group, demonstrated by a 14 % increased risk (HR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.02, 1.27, P-value = 0.02) compared with the low genetic liability group. The Coxph model including genetic liability was the best-performing model for stroke prediction achieving an AUC of 69.54 (95% CI = 67.40, 71.68), NRI of 0.202 (95% CI = 0.12, 0.28; P-value = 0.000) and IDI of 1.0×10-04 (95% CI = 0.000, 3.0×10-04; P-value = 0.13) compared with the Cox model without genetic liability. Conclusion: Incorporating genetic factors in the model may provide a slight incremental value for stroke prediction beyond conventional risk factors.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Genotyping and Imputation

2.4. Definition of the Outcome

2.5. Demographics, Clinical and Lifestyle Features

2.6. Computation of Genetic Liabilities

2.7. Data Preprocessing

3. Statistical Analysis

3.1. The Relationship Between Genetic Liability and Stroke

3.2. Prediction Models Development

4. Model Performance Assessment

5. Results

5.1. Study Characteristics

5.2. The Relationship Between Genetic Liability and Stroke

5.3. Prediction Value of the Conventional Factors

| Models | AUC 95%CI | NRI (95% CI) | P-value for NRI | IDI (95% CI) | P-value for IDI | Brier Score | ICI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coxph | Model 1 | 69.43 (67.30, 71.56) |

REF | REF | REF | REF | 0.01 | 0.002 |

| Model 2 | 69.54 (67.40, 71.68) |

0.20 (0.119, 0.285) |

0.00 | 1.0×10-04 (0.000, 3.0× 10-04) |

0.14 | 0.01 |

0.002 | |

|

GBM |

Model 1 | 69.34 (67.23, 71.50) |

REF | REF | REF | REF | 0.01 |

0.001 |

| Model 2 | 69.38 (67.26, 71.50) |

-0.11 (-0.193, -0.027) |

0.01 | 0.00 (-1.0×10-04, 1.0×10-04) |

0.61 | 0.01 |

0.001 | |

|

DT |

Model 1 |

67.58 (65.46, 69.70) |

REF | REF | REF | REF | 0.01 |

0.001 |

| Model 2 | 67.58 (65.46, 69.70) |

0.00 (0.00, 0.00) |

NaN | 0.00 (0.000, 0.000) |

NaN | 0.01 |

0.001 |

|

|

RF |

Model 1 | 65.62 (63.48, 67.75) |

REF | REF | REF | REF | 0.01 |

0.003 |

| Model 2 | 65.35 (63.18, 67.52) |

0.17 (0.087, 0.249) |

5.0×10-05 | 0.00 (-7.0×10-04, 8.0×10-04) |

0.98 | 0.01 |

0.003 |

5.4. Prediction Value of Genetic Liability

6. Discussion

Main Findings

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G, Ahmed M, Aksut B, Alam T, Alam K, Alla F, Alvis-Guzman N, Amrock S, Ansari H, Ärnlöv J, Asayesh H, Atey TM, Avila-Burgos L, Awasthi A, Banerjee A, Barac A, Bärnighausen T, Barregard L, Bedi N, Belay Ketema E, Bennett D, Berhe G, Bhutta Z, Bitew S, Carapetis J, Carrero JJ, Malta DC, Castañeda-Orjuela CA, Castillo-Rivas J, Catalá-López F, Choi JY, Christensen H, Cirillo M, Cooper L, Criqui M, Cundiff D, Damasceno A, Dandona L, Dandona R, Davletov K, Dharmaratne S, Dorairaj P, Dubey M, Ehrenkranz R, El Sayed Zaki M, Faraon E, Esteghamati A, Farid T, Farvid M, Feigin V, Ding EL, Fowkes G, Gebrehiwot T, Gillum R, Gold A, Gona P, Gupta R, Habtewold TD, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hailu T, Hailu GB, Hankey G, Hassen HY, Abate KH, Havmoeller R, Hay SI, Horino M, Hotez PJ, Jacobsen K, James S, Javanbakht M, Jeemon P, John D, Jonas J, Kalkonde Y, Karimkhani C, Kasaeian A, Khader Y, Khan A, Khang YH, Khera S, Khoja AT, Khubchandani J, Kim D, Kolte D, Kosen S, Krohn KJ, Kumar GA, Kwan GF, Lal DK, Larsson A, Linn S, Lopez A, Lotufo PA, El Razek H: Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017, 70(1).

- Krishnamurthi R, Ikeda T, Feigin V: Global, Regional and Country-Specific Burden of Ischaemic Stroke, Intracerebral Haemorrhage and Subarachnoid Haemorrhage: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Neuroepidemiology 2020, 54(2):171–179. [CrossRef]

- Dhamoon MS, Tai W, Boden-Albala B, Rundek T, Paik MC, Sacco RL, Elkind MSV: Risk of Myocardial Infarction or Vascular Death After First Ischemic Stroke: The Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke 2007, 38(6):1752–1758. [CrossRef]

- DHAMOON MS, SCIACCA RR, RUNDEK T, SACCO RL, ELKIND MSV: Recurrent stroke and cardiac risks after first ischemic stroke : The Northern Manhattan study. Neurology 2006, 66(5):641–646. [CrossRef]

- Kyme C: After ischemic stroke, patients are at higher risk of recurrent stroke than of cardiac events. Nature clinical practice cardiovascular medicine 2005, 2(9):436. [CrossRef]

- Engstad T, Viitanen M, Arnesen E: Predictors of Death Among Long-Term Stroke Survivors. Stroke 2003, 34(12):2876–2880. [CrossRef]

- King D, Wittenberg R, Patel A, Quayyum Z, Berdunov V, Knapp M: The future incidence, prevalence and costs of stroke in the UK. Age and ageing 2020, 49(2):277–282. [CrossRef]

- Boehme AK, Esenwa C, Elkind MSV: Stroke Risk Factors, Genetics, and Prevention. Circulation Research 2017, 120(3):472–495. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Floyd J, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Mackey RH, Matsushita K, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Thiagarajan RR, Reeves MJ, Ritchey M, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sasson C, Towfighi A, Tsao CW, Turner MB, Virani SS, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P: Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 135(10):e146–e603. [CrossRef]

- Bak S, Gaist D, Sindrup SH, Skytthe A, Christensen K: Genetic Liability in Stroke: A Long-Term Follow-Up Study of Danish Twins. Stroke 2002, 33(3):769–774. [CrossRef]

- Malik R, Chauhan G, Traylor M, Okada Y, Giese AK, Laan S, Chong M, Adams H, Ago T, Almgren P, Amouyel P, Bevan S, Boncoraglio GB, Brown RD, Butterworth AS, Carrera C, Carty CL, Cole JW, Correa A, Danesh J, DeStefano AL, den Hoed M, Engelter ST, Gottesman RF, Haessler J, Harris TB, Hassan A, Havulinna AS, Heckbert SR, Holliday EG, Hyacinth HI, Ikram A, Ingelsson E, Jimenez-Conde J, Kanai M, Kissela BM, Kleindorfer DO, Kooperberg C, Kubo M, Langefeld CD, Langenberg C, Lee JM, Lemmens R, Leys D, Lewis CM, Lin WY, Lorentzen E, Magnusson PK, Meschia JF, Mosley TH, Ninomiya T, Psaty BM, Pulit SL, Rexrode KM, Rice K, Ridker PM, Rothwell PM, Rotter JI, Sacco RL, Sakaue S, Salomaa V, Schmidt R, Schminke U, Tanislav C, Thijs V, Thorsteinsdottir U, Trompet S, Duijn C, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Wilson JG, Yang Q, Yusuf S, Bis JC, Pastinen T, Schadt EE, Koplev S, Civelek M, Smith NL, Lubitz SA, Ellinor PT, Kooner JS, Kato N, He J, Chambers JC, Johnson AD, Sanghera DK, Melander O, Jern C, Strbian D, Longstreth WT, Hata J, Woo D, Rosand J, Pare G, Worrall BB, Kittner SJ, Fornage M, Markus HS, Kamatani Y, Dichgans M: Multiancestry genome-wide association study of 520,000 subjects identifies 32 loci associated with stroke and stroke subtypes. Nature Genetics 2018, 50(4):524–+. [CrossRef]

- Malik R, Rannikmäe K, Traylor M, Georgakis MK, Sargurupremraj M, Markus HS, Hopewell JC, Debette S, Sudlow CLM, Dichgans M: Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 3 novel loci associated with stroke. Annals of neurology 2018, 84(6):934–939. [CrossRef]

- American Heart Association News: New tool brings big changes to cardiovascular disease predictions. Premium Official News 2023.

- Elias MF, Sullivan LM, D'Agostino RB, Elias PK, Beiser A, Au R, Seshadri S, DeCarli C, Wolf PA: Framingham Stroke Risk Profile and Lowered Cognitive Performance. Stroke 2004, 35(2):404–409. [CrossRef]

- Bohr A, Memarzadeh K: The rise of artificial intelligence in healthcare applications. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare 2020, :25–60. [CrossRef]

- Knowles JW, Ashley EA: Cardiovascular disease: The rise of the genetic risk score. PLoS medicine 2018, 15(3):e1002546. [CrossRef]

- Traylor M, MSc, Farrall M, FRCPath, Holliday EG, PhD, Sudlow C, FRCP, Hopewell JC, PhD, Cheng Y, PhD, Fornage M, PhD, Ikram MA, MD, Malik R, PhD, Bevan S, PhD, Thorsteinsdottir U, PhD, Nalls MA, PhD, Longstreth W, MD, Wiggins KL, MS, Yadav S, MSc, Parati EA, MD, DeStefano AL, PhD, Worrall BB, MD, Kittner SJ, MD, Khan MS, MSc, Reiner AP, MD, Helgadottir A, MD, Achterberg S, PhD, Fernandez-Cadenas I, PhD, Abboud S, MD, Schmidt R, MD, Walters M, MD, Chen W, PhD, Ringelstein EB, MD, O'Donnell M, MD, Ho WK, PhD, Pera J, MD, Lemmens R, MD, Norrving B, MD, Higgins P, MRCP, Benn M, MD, Sale M, PhD, Kuhlenbäumer G, MD, Doney ASF, PhD, Vicente AM, PhD, Delavaran H, MD, Algra A, MD, Davies G, PhD, Oliveira SA, PhD, Palmer CNA, PhD, Deary I, PhD, Schmidt H, MD, Pandolfo M, MD, Montaner J, MD, Carty C, PhD, de Bakker PIW, PhD, Kostulas K, MD, Ferro JM, MD, van Zuydam NR, MSc, Valdimarsson E, MD, Nordestgaard BG, MD, Lindgren A, MD, Thijs V, MD, Slowik A, MD, Saleheen D, MD, Paré G, MD, Berger K, MD, Thorleifsson G, PhD, Hofman A, MD, Mosley TH, PhD, Mitchell BD, PhD, Furie K, MD, Clarke R, FRCP, Levi C, MD, Seshadri S, MD, Gschwendtner A, MD, Boncoraglio GB, MD, Sharma P, PhD, Bis JC, PhD, Gretarsdottir S, PhD, Psaty BM, Rothwell PM, FMedSci, Rosand J, MD, Meschia JF, MD, Stefansson K, MD, Dichgans M, MD, Markus HS, Dr: Genetic risk factors for ischaemic stroke and its subtypes (the METASTROKE Collaboration): a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet neurology 2012, 11(11):951–962. [CrossRef]

- Abraham G, Rutten-Jacobs L, Inouye M: Risk Prediction Using Polygenic Risk Scores for Prevention of Stroke and Other Cardiovascular Diseases. Stroke 2021, 52(9):2983–2991. [CrossRef]

- Gschwendtner A, Dichgans M: Genetics of ischemic stroke. Nervenarzt 2013, 84(2):166. [CrossRef]

- Della-Morte D, Guadagni F, Palmirotta R, Testa G, Caso V, Paciaroni M, Abete P, Rengo F, Ferroni P, Sacco RL, Rundek T: Genetics of ischemic stroke, stroke-related risk factors, stroke precursors and treatments. Pharmacogenomics 2012, 13(5):595–613. [CrossRef]

- Malik R, Hachiya T, Jürgenson T, Namba S, Kamanu FK, Le Grand Q, He Y, Georgakis MK, Krebs K, Vaura FC, Lin K, Winsvold BS, Srinivasasainagendra V, Chong MR, Akinyemi R, Jee YH, Abedi V, Nygaard M, Leonard HL, Knol MJ, Lewis AJ, Ago T, Amouyel P, Armstrong ND, Bartz TM, Bordes C, Børte S, Cain A, Ridker PM, Chen Z, Cole JW, de Jager PL, de Cid R, Endres M, Ferreira LE, Geerlings MI, Gudnason V, Hata J, Ho Y, Havulinna AS, Hopewell JC, Hyacinth HI, Inouye M, Kittner SJ, Kumar A, Lacaze P, Li J, Mitchell BD, Mosley TH, Nordestgaard BG, Okada Y, Onland-Moret NC, Ovbiagele B, Peters A, Sabatine MS, Saleheen D, Sandset EC, Salomaa V, Shimizu A, Sloane KL, Tanno K, Torres-Aguila NP, Trégouët D, Trompet S, Tuladhar AM, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Vibo R, Wiggins KL, Wilson PWF, Yang Q, Yoon K, Ninomiya T, Grabe HJ, Strbian D, Kim YJ, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Ikram MA, Rundek T, Lathrop GM, Riaz M, Simonsick EM, Prasad K, Frikke-Schmidt R, Liman T, Haeusler KG, Heuschmann PU, Longstreth WT, Paré G, Damrauer SM, Chasman DI, Rotter JI, Anderson CD, Zwart J, Niiranen TJ, Fornage M, Liaw Y, Fernández-Cadenas I, Walters RG, Ruff CT, Milani L: Stroke genetics informs drug discovery and risk prediction across ancestries. Nature 2022, 611(7934):115–123. [CrossRef]

- Myserlis EP, Georgakis MK, Demel SL, Sekar P, Chung J, Malik R, Hyacinth HI, Comeau ME, Falcone GJ, Langefeld CD, Rosand J, Woo D, Anderson CD: A Genomic Risk Score Identifies Individuals at High Risk for Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke 2023, 54(4):973–982. [CrossRef]

- Rutten-Jacobs LC, Larsson SC, Malik R, Rannikmäe K, Sudlow CL, Dichgans M, Markus HS, Traylor M: Genetic risk, incident stroke, and the benefits of adhering to a healthy lifestyle: cohort study of 306 473 UK Biobank participants. BMJ 2018, 363:k4168–k4168. [CrossRef]

- Yang S, Sun Z, Sun D, Yu C, Guo Y, Sun D, Pang Y, Pei P, Yang L, Millwood IY, Walters RG, Chen Y, Du H, Lu Y, Burgess S, Avery D, Clarke R, Chen J, Chen Z, Li L, Lv J: Associations of polygenic risk scores with risks of stroke and its subtypes in Chinese. Stroke and vascular neurology 2024, 9(4):399–406. [CrossRef]

- Abraham G, Malik R, Yonova-Doing E, Salim A, Wang T, Danesh J, Butterworth AS, Howson JMM, Inouye M, Dichgans M: Genomic risk score offers predictive performance comparable to clinical risk factors for ischaemic stroke. Nature Communications 2019, 10(1):5819. [CrossRef]

- Verbaas C, Fornage M, Bis JC, Choi SH, Psaty BM, Meigs JB, Rao M, Nalls M, Fontes JD, O'Donnell CJ, Kathiresan S, Ehret GB, Fox CS, Malik R, Dichgans M, Schmidt H, Lahti J, Heckbert SR, Lumley T, Rice K, Rotter JI, Taylor KD, Folsom AR, Boerwinkle E, Rosamond WD, Shahar E, Gottesman RF, Koudstaal P, Amin N, Wieberdink R, Dehghan A, Hofman B, Uitterlinden A, DeStefano AL, Debette S, Xue LT, Beiser A, Wolf PA, DeCarli C, Ikram A, Seshai S, Mosley TH, Longstreth WT, Duijn C, Launer LJ: Predicting Stroke Through Genetic Risk Functions The CHARGE Risk Score Project. Stroke (1970) 2014, 45(2):403–412. [CrossRef]

- HUNT All-In Stroke, CADISP group, International Consortium for Blood Pressure, International Headache Genetics Consortium, International Stroke Genetics Consortium (ISGC) Intracranial Aneurysm Working Group: Genetic Risk Score for Intracranial Aneurysms: Prediction of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Role in Clinical Heterogeneity. 2023,. [CrossRef]

- MALIK R, BEVAN S, DE STEFANO AL, FORNAGE M, PSATY BM, IKRAM MA, LAUNER LJ, VAN DUIJN CM, SHARMA P, MITCHELL BD, ROSAND J, MESCHIA JF, NALLS MA, LEVI C, ROTHWELL PM, SUDLOW C, MARKUS HS, SESHADRI S, DICHGANS M, HOLLIDAY EG, DEVAN WJ, CHENG Y, IBRAHIM-VERBAAS CA, VERHAAREN BFJ, BIS JC, JOON AY: Multilocus Genetic Risk Score Associates With Ischemic Stroke in Case–Control and Prospective Cohort Studies. Stroke 2014, 45(2):394–402. [CrossRef]

- Hachiya T, Hata J, Hirakawa Y, Yoshida D, Furuta Y, Kitazono T, Shimizu A, Ninomiya T: Genome-Wide Polygenic Score and the Risk of Ischemic Stroke in a Prospective Cohort: The Hisayama Study. Stroke (1970) 2020, 51(3):759–765. [CrossRef]

- Hachiya T, Kamatani Y, Takahashi A, Hata J, Furukawa R, Shiwa Y, Yamaji T, Hara M, Tanno K, Ohmomo H, Ono K, Takashima N, Matsuda K, Wakai K, Sawada N, Iwasaki M, Yamagishi K, Ago T, Ninomiya T, Fukushima A, Hozawa A, Minegishi N, Satoh M, Endo R, Sasaki M, Sakata K, Kobayashi S, Ogasawara K, Nakamura M, Hitomi J, Kita Y, Tanaka K, Iso H, Kitazono T, Kubo M, Tanaka H, Tsugane S, Kiyohara Y, Yamamoto M, Sobue K, Shimizu A: Genetic Predisposition to Ischemic Stroke: A Polygenic Risk Score. Stroke (1970) 2017, 48(2):253–258. [CrossRef]

- Lynch CM, Abdollahi B, Fuqua JD, de Carlo AR, Bartholomai JA, Balgemann RN, van Berkel VH, Frieboes HB: Prediction of lung cancer patient survival via supervised machine learning classification techniques. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2017, 108:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Chun M, Clarke R, Cairns BJ, Clifton D, Bennett D, Chen Y, Guo Y, Pei P, Lv J, Yu C, Yang L, Li L, Chen Z, Zhu T: Stroke risk prediction using machine learning: a prospective cohort study of 0.5 million Chinese adults. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2021, 28(8):1719–1727. [CrossRef]

- MacCarthy G, Pazoki R: Using Machine Learning to Evaluate the Value of Genetic Liabilities in the Classification of Hypertension within the UK Biobank. Journal of clinical medicine 2024, 13(10):2955. [CrossRef]

- Schjerven FE, Ingeström EML, Steinsland I, Lindseth F: Development of risk models of incident hypertension using machine learning on the HUNT study data. 2024,. [CrossRef]

- Wongvibulsin S, Wu KC, Zeger SL: Clinical risk prediction with random forests for survival, longitudinal, and multivariate (RF-SLAM) data analysis. BMC Medical research methodology 2019, 20(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Zhang L, Niu M, Li R, Tu R, Liu X, Hou J, Mao Z, Wang Z, Wang C: Genetic Risk Score Increased Discriminant Efficiency of Predictive Models for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Using Machine Learning: Cohort Study. Frontiers in Public Health 2021, 9:606711. [CrossRef]

- Datema FR, Moya A, Krause P, Bäck T, Willmes L, Langeveld T, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Blom HM: Novel head and neck cancer survival analysis approach: Random survival forests versus cox proportional hazards regression. Head & neck 2012, 34(1):50–58. [CrossRef]

- Qiu X, Gao J, Yang J, Hu J, Hu W, Kong L, Lu JJ: A Comparison Study of Machine Learning (Random Survival Forest) and Classic Statistic (Cox Proportional Hazards) for Predicting Progression in High-Grade Glioma after Proton and Carbon Ion Radiotherapy. Frontiers in oncology 2020, 10:551420. [CrossRef]

- Xu L, Cai L, Zhu Z, Chen G: Comparison of the cox regression to machine learning in predicting the survival of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. BMC endocrine disorders 2023, 23(1):129. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou A, Harding D, Slabaugh G, Marouli E, Deloukas P: Prediction of atrial fibrillation and stroke using machine learning models in UK Biobank. Heliyon 2024, 10(7):e28034. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Deng Y, Tan Y, Zhou M, Jiang Y, Liu B: A comparison of random survival forest and Cox regression for prediction of mortality in patients with hemorrhagic stroke. BMC medical informatics and decision making 2023, 23(1):1–215. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Chung J, Yeh Y, Lou S, Lin H, Lin C, Hsien H, Hung K, Yeh SJ, Shi H: Predicting 30-Day Readmission for Stroke Using Machine Learning Algorithms: A Prospective Cohort Study. Frontiers in neurology 2022, 13:875491. [CrossRef]

- Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, Downey P, Elliott P, Green J, Landray M, Liu B, Matthews P, Ong G, Pell J, Silman A, Young A, Sprosen T, Peakman T, Collins R: UK Biobank: An Open Access Resource for Identifying the Causes of a Wide Range of Complex Diseases of Middle and Old Age. PLoS medicine 2015, 12(3):e1001779. [CrossRef]

- Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott L, Sharp K, Motyer A, Vukcevic D, Delaneau O, O'connell J, Cortes A, Welsh S, Mcvean G, Leslie S, Donnelly P, Marchini J: Genome-wide genetic data on ~500,000 UK biobank participants. bioRxiv 2017. [CrossRef]

- Welsh S, Peakman T, Sheard S, Almond R: Comparison of DNA quantification methodology used in the DNA extraction protocol for the UK Biobank cohort. BMC Genomics 2017, 18(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, Motyer A, Vukcevic D, Delaneau O, O'Connell J, Cortes A, Welsh S, Young A, Effingham M, McVean G, Leslie S, Allen N, Donnelly P, Marchini J: The Uk biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 2018, 562(7726):203–209. [CrossRef]

- Wtchg (, Oxford ), Delaneau O: UK Biobank Phasing and Imputation Documentation Contributors to UK Biobank Phasing and Imputation. Claire Bycroft 2015.

- Sacks DB, Arnold M, Bakris GL, Bruns DE, Horvath AR, Kirkman MS, Lernmark A, Metzger BE, Nathan DM: Guidelines and Recommendations for Laboratory Analysis in the Diagnosis and Management of Diabetes Mellitus. Clinical chemistry (Baltimore, Md.) 2011, 57(6):e1–e47. [CrossRef]

- Flack JM, Adekola B: Blood pressure and the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines. Trends in cardiovascular medicine 2020, 30(3):160–164. [CrossRef]

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo J, Joseph L, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright J, Jackson T, Roccella EJ, and the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee: The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 Report. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2003, 289(19):2560–2571. [CrossRef]

- Pazoki R, Dehghan A, Evangelou E, Warren H, Gao H, Caulfield M, Elliott P, Tzoulaki I: Genetic Predisposition to High Blood Pressure and Lifestyle Factors: Associations With Midlife Blood Pressure Levels and Cardiovascular Events. Circulation (New York, N.Y.) 2018, 137(7):653–661. [CrossRef]

- Malik R, Chauhan G, Traylor M, Sargurupremraj M, Okada Y, Mishra A, Rutten-Jacobs L, Giese AK, van Der Laan SW, Gretarsdottir S, Anderson CD, Chong M, Adams HHH, Ago T, Almgren P, Amouyel P, Ay H, Bartz TM, Benavente OR, Bevan S, Boncoraglio GB, Brown RD, Jr, Butterworth AS, Carrera C, Carty CL, Chasman DI, Chen WM, Cole JW, Correa A, Cotlarciuc I, Cruchaga C, Danesh J, de Bakker PIW, Destefano AL, den Hoed M, Duan Q, Engelter ST, Falcone GJ, Gottesman RF, Grewal RP, Gudnason V, Gustafsson S, Haessler J, Harris TB, Hassan A, Havulinna AS, Heckbert SR, Holliday EG, Howard G, Hsu FC, Hyacinth HI, Ikram MA, Ingelsson E, Irvin MR, Jian X, Jimenez-Conde J, Johnson JA, Jukema JW, Kanai M, Keene KL, Kissela BM, Kleindorfer DO, Kooperberg C, Kubo M, Lange LA, Langefeld CD, Langenberg C, Launer LJ, Lee JM, Lemmens R, Leys D, Lewis CM, Lin WY, Lindgren AG, Lorentzen E, Magnusson PK, Maguire J, Manichaikul A, Mcardle PF, Meschia JF, Mitchell BD, Mosley TH, Nalls MA, Ninomiya T, O'Donnell MJ, Psaty BM, Pulit SL, Rannikmae K, Reiner AP, Rexrode KM, Rice K, Rich SS, Ridker PM, Rost NS, Rothwell PM, Rotter JI, Rundek T, Sacco RL, Sakaue S, Sale MM: Multiancestry genome-wide association study of 520,000 subjects identifies 32 loci associated with stroke and stroke subtypes. Nature genetics 2018, 50(4):524–537. [CrossRef]

- Marees AT, de Kluiver H, Stringer S, Vorspan F, Curis E, Marie-Claire C, Derks EM: A tutorial on conducting genome-wide association studies: Quality control and statistical analysis. International journal of methods in psychiatric research 2018, 27(2):e1608–n/a. [CrossRef]

- Chang CC: Data management and summary statistics with PLINK. Methods in molecular biology 2020, 2090:49–65. [CrossRef]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PIW, Daly MJ, Sham PC: PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. American journal of human genetics 2007, 81(3):559–575. [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team: R : a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http 2010,.

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS: Using multivariate statistics: 6th ed. ed. Boston [u.a.]: Pearson; 2013.

- Dormann CF, Elith J, Bacher S, Buchmann C, Carl G, Carré G, Marquéz JRG, Gruber B, Lafourcade B, Leitão PJ, Münkemüller T, McClean C, Osborne PE, Reineking B, Schröder B, Skidmore AK, Zurell D, Lautenbach S: Collinearity: a review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 2013, 36(1):27–46. [CrossRef]

- Deo SV, Deo V, Sundaram V: Survival analysis—part 2: Cox proportional hazards model. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021, 37(2):229–233. [CrossRef]

- Abd ElHafeez S, D’Arrigo G, Leonardis D, Fusaro M, Tripepi G, Roumeliotis S: Methods to Analyze Time-to-Event Data: The Cox Regression Analysis. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2021, 2021(1):1302811. [CrossRef]

- Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman JH: Theœ elements of statistical learning: 2. ed., corrected at 5. print. ed. New York [u.a.]: Springer; 2011. [CrossRef]

- Breiman L: Random Forests. Machine learning 2001, 45(1):5–32. [CrossRef]

- PLATT J: Probabilistic outputs for support vector machines and comparisons to regularized likelihood methods. Advances in Largin Margin Classifiers 2000.

- Huang Y, Li W, Macheret F, Gabriel RA, Ohno-Machado L: A tutorial on calibration measurements and calibration models for clinical prediction models. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2020, 27(4):621–633. [CrossRef]

- Van Calster B, Nieboer D, Vergouwe Y, De Cock B, Pencina MJ, Steyerberg EW: A calibration hierarchy for risk models was defined: from utopia to empirical data. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2016, 74:167–176. [CrossRef]

- Miller TD, Askew JW: Net reclassification improvement and integrated discrimination improvement: new standards for evaluating the incremental value of stress imaging for risk assessment. Circulation. Cardiovascular imaging 2013, 6(4):496–498. [CrossRef]

- McKearnan SB, Wolfson J, Vock DM, Vazquez-Benitez G, O’Connor PJ: Performance of the Net Reclassification Improvement for Nonnested Models and a Novel Percentile-Based Alternative. American journal of epidemiology 2018, 187(6):1327–1335. [CrossRef]

- Pencina MJ, D'Agostino Sr RB, Steyerberg EW: Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Statistics in medicine 2011, 30(1):11–21. [CrossRef]

- Steyerberg E, Vickers A, Cook N, Gerds T, Gonen M, Obuchowski N, Pencina M, Kattan M: Assessing the performance of prediction models: A framework for traditional and novel measures. 2010, :. [CrossRef]

- Clark K, Fu W, Liu C, Ho P, Wang H, Lee W, Chou S, Wang L, Tzeng J: The prediction of Alzheimer's disease through multi-trait genetic modeling. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2023, 15:1168638. [CrossRef]

- Wray NR, Goddard ME: Multi-locus models of genetic risk of disease. Genome medicine 2010, 2(2):10. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Namba S, Lopera E, Kerminen S, Kanai M, Zhou W, Bhatta L, Awadalla P, Hveem K, Lo Faro V, Mägi R, Sanna S, Smoller JW, Uzunovic J, Rasheed H, Tsuo K, Hirbo JB, Bhattacharya A, Zhao H, Surakka I, Wolford BN, Läll K, Favé M, Chapman SB, Karjalainen J, Kurki M, Mutaamba M, Partanen JJ, Chavan S, Chen T, Daya M, Ding Y, Graham SE, Ingold N, Johnson R, Laisk T, Lin K, Lv J, Millwood IY, Pandit A, Preuss MH, Thorsteinsdottir U, Zawistowski M, Zhong X, Campbell A, Douville NJ, Finer S, Griffiths CJ, Marioni RE, Nomdo J, Patil S, Richmond A, Straub P, Vanderwerff B, Barnes KC, Chen Z, Chen C, Smith GD, Finucane HK, Franke L, Gamazon ER, Ganna A, Gaunt TR, Ge T, Huffman J, MacGregor S, Matsuda K, Olsen CM, Porteous DJ, Shavit JA, Trembath RC, Vonk JM, Whiteman D, Wicks SJ, Wijmenga C, Wright J, Zhou X, Cox NJ, Geschwind DH, Hayward C, Kenny EE, Lin Y, Martin HC, Walters RG, Zöllner S, Martin AR, Willer CJ, Daly MJ, Neale BM, Okada Y, Hirbo J: Global Biobank analyses provide lessons for developing polygenic risk scores across diverse cohorts. Cell genomics 2023, 3(1):100241. [CrossRef]

- Cárcel-Márquez J, Muiño E, Gallego-Fabrega C, Cullell N, Lledós M, Llucià-Carol L, Sobrino T, Campos F, Castillo J, Freijo M, Arenillas JF, Obach V, Álvarez-Sabín J, Molina CA, Ribó M, Jiménez-Conde J, Roquer J, Muñoz-Narbona L, Lopez-Cancio E, Millán M, Diaz-Navarro R, Vives-Bauza C, Serrano-Heras G, Segura T, Ibañez L, Heitsch L, Delgado P, Dhar R, Krupinski J, Delgado-Mederos R, Prats-Sánchez L, Camps-Renom P, Blay N, Sumoy L, de Cid R, Montaner J, Cruchaga C, Lee J, Martí-Fàbregas J, Férnandez-Cadenas I: A Polygenic Risk Score Based on a Cardioembolic Stroke Multitrait Analysis Improves a Clinical Prediction Model for This Stroke Subtype. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine 2022, 9:940696. [CrossRef]

- Jung KJ, Hwang S, Lee S, Kim HC, Jee SH: Traditional and Genetic Risk Score and Stroke Risk Prediction in Korea. Korean circulation journal 2018, 48(8):731–740. [CrossRef]

- Du M, Haag DG, Lynch JW, Mittinty MN: Comparison of the Tree-Based Machine Learning Algorithms to Cox Regression in Predicting the Survival of Oral and Pharyngeal Cancers: Analyses Based on SEER Database. Cancers 2020, 12(10):2802. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Overall (N=243,399) |

Non-event (N=241,426) |

Stroke event (N=1973) |

HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM, Yes; n (%) | 6939 (2.9%) | 6826 (2.8%) | 113 (5.7%) | 2.08(1.72, 2.51) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, Yes; n (%) | 116216 (47.7%) | 114840 (47.6%) | 1376 (69.7%) | 2.52(1.29, 2.78) | <0.001 |

| Sex, Male; n (%) | 102187 (42.0%) | 101107 (41.9%) | 1080 (54.7%) | 1.67 (1.53, 1.83) | <0.001 |

| Age (Years), Mean (SD) | 55.4 (7.98) | 55.4 (7.98) | 60.0 (7.14) | 1.93 (1.83, 2.03) | <0.0001 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m^2), Mean (SD) | 26.8 (4.57) | 26.8 (4.57) | 27.4 (4.83) | 1.12 (1.08, 1.17) | <0.001 |

| Total Cholesterol (mmol/l), Mean (SD) | 5.91 (1.06) | 5.91 (1.06) | 5.94 (1.09) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.07) | 0.30* |

| LDL (mmol/l), Mean (SD) | 4.68 (2.37) | 4.67 (2.36) | 5.03 (2.51) | 1.03 (1.03, 1.12) | 0.002 |

| Smoking | |||||

| Current; n (%) | 76397 (31.4%) | 75647 (31.3%) | 750 (38.0%) | REF | REF |

| Previous; n(%) | 2900 (1.2%) | 2855 (1.2%) | 45 (2.3%) | 1.58 (1.17, 2.13) | 0.003 |

| Never; n (%) | 164102 (67.4%) | 162924 67.5%) | 1178 (59.7%) | 0.73 (0.67, 0.80) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol | |||||

| Current; n(%) | 228349 (93.8%) | 226556(93.8%) | 1793 (90.9%) | REF | REF |

| Previous; n(%) | 7082 (2.9%) | 6996 (2.9%) | 86 (4.4%) | 1.55 (1.25, 1.93) | <0.001 |

| Never; n (%) | 7968 (3.3%) | 7874 (3.3%) | 94 (4.8%) | 1.50 (1.22, 1.85) | <0.001 |

| Genetic liability Level | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

HR (95% CI) |

P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| Moderate Risk | 1.06(0.95, 1.18) | 0.31 | 1.06(0.95, 1.18) | 0.31 | 1.05 (0.94, 1.17) | 0.04 | 1.05(0.94, 1.17) | 0.40 |

| High Risk | 1.15(1.03, 1.28) | 0.01 | 1.16(1.04, 1.30) | 0.01 | 1.14(1.02, 1.27) | 0.02 | 1.14(1.02, 1.27) | 0.02 |

| Genetic liability (continuous) | 1.08(1.03, 1.13) | <0.001 |

1.08(1.03,1.13) | <0.001 | 1.07(1.03, 1.12) | 0.002 | 1.07(1.02, 1.12) | 0.003 |

| Characteristics | chisq | df | P-value |

| Sex | 0.42 | 1 | 0.52 |

| Age | 0.82 | 1 | 0.37 |

| BMI | 7.49 | 1 | 0.01 |

| DM | 0.08 | 1 | 0.78 |

| HTN | 0.14 | 1 | 0.71 |

| LDL | 0.36 | 1 | 0.55 |

| Smoking | 1.40 | 1 | 0.24 |

| Alcohol | 0.12 | 1 | 0.73 |

| SGL | 2.48 | 1 | 0.12 |

| GLOBAL | 13.43 | 9 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).