Submitted:

17 June 2023

Posted:

20 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Dataset

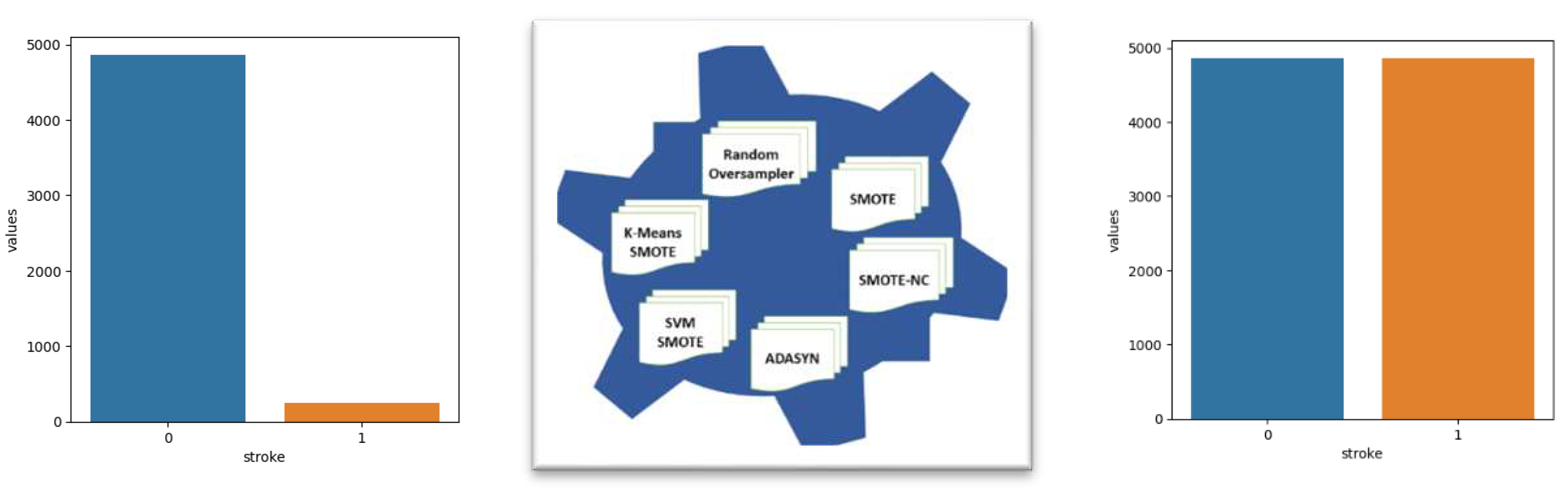

4. Methodology for Handling Imbalanced Data

- Overfitting: Imbalanced datasets can lead to overfitting, where the model performs well on the training data but poorly on unseen data. This is because the model may learn to focus on the majority class and ignore the minority class, leading to poor performance in the minority class. In other words, the model is too specific to the training data and has learned the noise and patterns that are unique to the training set rather than the general underlying patterns that are present in the data. Think of it like a student who has memorized all the answers to a specific test but does not understand the underlying concepts. If the student is given a similar test, they may do very well, but if they are given a different test with new questions, they may struggle. Similarly, in machine learning, a model can be too specific to the training data and have learned the noise and patterns that are unique to the training set, rather than the general underlying patterns that are present in the data. As a result, when the model encounters new data that is not similar to the training data, it may not perform well and make incorrect predictions.

- Biased predictions: Imbalanced datasets can lead to biased predictions, where the model is more likely to predict the majority class, even when the minority class is more likely. Biased predictions are a significant concern in machine learning and data science research. It refers to a situation where machine learning models or algorithms trained on a dataset exhibit systematic and consistent inaccuracies, due to certain biases in the data or model design. Biased predictions can have far-reaching consequences, especially when they are used to make decisions that affect people's lives, such as in healthcare, finance, hiring, and the criminal justice system. If the predictions are based on biased data or models, they can perpetuate and exacerbate existing social and economic disparities and lead to unfair or discriminatory outcomes. Biased predictions can have a significant impact on healthcare, particularly in the areas of diagnosis and treatment. For example, if a machine learning algorithm is trained on a dataset that does not include enough data from certain minority groups or regions, the algorithm may not be able to accurately predict or diagnose illnesses that are more prevalent in those populations. As a result, patients from those groups may be misdiagnosed or receive suboptimal treatment. In addition, machine learning algorithms can also perpetuate biases in healthcare decision-making, such as those related to gender, race, or socioeconomic status. For example, a model that predicts the likelihood of readmission to a hospital may use variables that are correlated with race or socioeconomic status, leading to unfair or discriminatory decisions. This can lead to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment for patients in the minority class.

- Poor performance metrics: Imbalanced datasets can lead to poor performance metrics such as accuracy, precision, and recall, which are commonly used to evaluate the performance of a model. Because these metrics are based on the overall accuracy of the model, they may not accurately reflect the model's ability to correctly predict the minority class.

- Difficulty in comparing models: Imbalanced datasets can make it difficult to compare the performance of different models, as models that achieve high accuracy on an imbalanced dataset may not perform as well on a balanced dataset.

- Oversampling: The process of increasing the number of samples from the minority class. This involves increasing the number of samples in the minority class by randomly duplicating existing samples [15]. This can help to balance the dataset, but it can also lead to overfitting if the oversampling is not done carefully.

- Undersampling: This involves reducing the number of samples in the majority class by randomly removing samples. This can help to balance the dataset, but it can also lead to a loss of important information if the undersampling is not done carefully.

- Generating synthetic samples: This involves creating new samples for the minority class by combining or modifying existing samples. One popular method is called SMOTE [16](Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) which generates synthetic samples by interpolating between existing minority samples. Other methods include ADASYN (Adaptive Synthetic Sampling) that generates synthetic samples by adjusting the density of the minority class, and Borderline-SMOTE which generates synthetic samples by focusing on samples that are near the decision boundary.

- Using different loss functions: Some loss functions such as Focal Loss, Weighted Cross-Entropy loss, and Dice Loss consider the imbalance of the dataset and adjust the model's weighting of the classes during training.

- Ensemble methods: Ensemble methods like bagging and boosting can also be used to balance the dataset by combining the predictions of multiple models.

- Transfer learning: Pre-training models on a large dataset and then fine-tuning them on a smaller, imbalanced dataset can also be used to balance the dataset.

Oversample (ROS)

Oversample (SMOTE)

Oversample (SMOTENC)

Oversample (ADASYN)

Oversample (SVM SMOTE)

Oversample (K Means SMOTE)

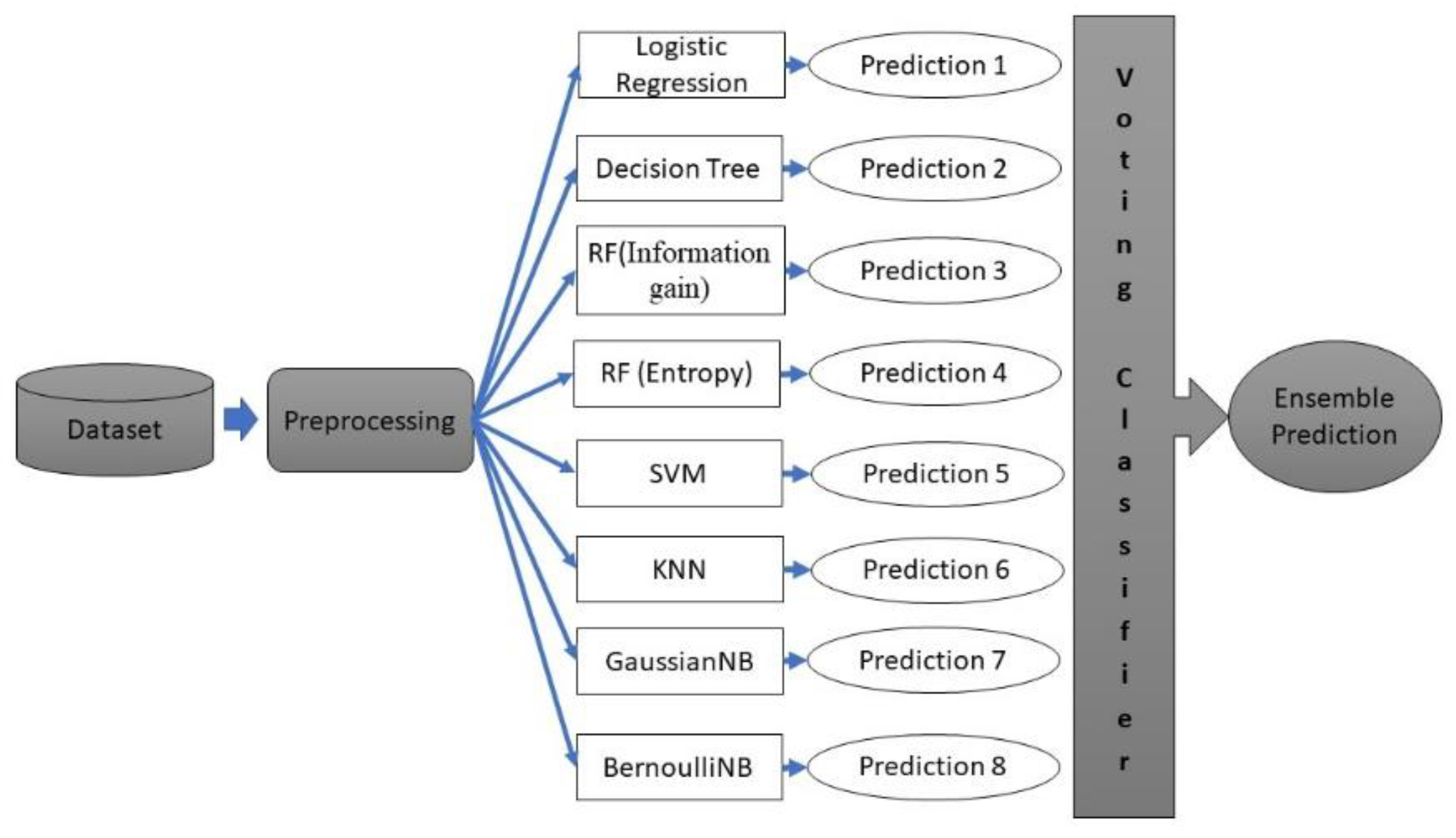

5. Process

- Missing values – Updated the null values of bmi (Body Mass Index) with the mean value.

- Drop ID Column as Stroke is not dependent on this Column.

- Label Encoding - 5 Columns are of Object Type i.e., Gender, ever_married, work_type, Residence_type and Smoking Status. Converted these categorical variables to numerical values, as most machine learning algorithms cannot handle categorical data directly.

- Resample data for handling imbalanced data (We have used seven techniques of Oversampling as mentioned in the Methodology)

- Splitting the data for train and test

- Classification Algorithms

- 1)

- Logistic Regression: Logistic Regression [21] is a popular machine learning algorithm used for binary classification problems, where the goal is to predict a binary outcome (e.g., yes/no, true/false). It uses a logistic function to model the probability of a binary outcome based on input features. If the output of the logistic function is greater than 0.5, the prediction is the positive class, and if it is less than 0.5, the prediction is the negative class. Logistic Regression models the relationship between the dependent variable and independent variables as a logistic curve, making predictions in the form of probabilities. These probabilities can then be used as thresholds to make binary class predictions. Logistic Regression is relatively simple to implement, computationally efficient, and can handle a large number of features. The logistic regression algorithm can be extended to handle multiclass classification problems by using one-vs-all or softmax regression. It is widely used in a variety of applications, such as medical diagnosis, credit scoring, image classification, and marketing.

- 2)

- Decision Tree: A Decision Tree is a tree-based machine learning algorithm that works by recursively splitting the data into smaller subsets based on the features that provide the greatest information gain, until the data can be split no further. At each split, a decision is made based on a certain feature, and the data is divided into separate branches, with each branch representing a different outcome. The final result is a tree structure with decision rules at each internal node, and predictions at the leaves. Decision trees are simple, easy to interpret, and can handle both categorical and numerical data. They can be used for both classification and regression tasks. They can handle imbalanced data by adjusting the parameters such as the minimum number of samples required to split a node or create a leaf.

- 3)

-

Random Forest: Random Forest is an ensemble of decision trees; it creates multiple decision trees and combines their predictions to make the final decision. The idea behind this is that multiple trees can work together to overcome the limitations of a single decision tree, such as overfitting, by reducing the variance and increasing the robustness of the model. Random Forest is a powerful and versatile machine learning method that can handle both linear and non-linear relationships, missing values, and large datasets. It is widely used in many applications, such as credit scoring, medical diagnosis, and environmental monitoring.

-

In a Random Forest, information gain is a commonly used criterion for splitting the data at each node of a decision tree. Information gain measures the reduction in entropy (or uncertainty) of the target variable after a split, and the feature that provides the highest information gain is chosen as the splitting feature. The process is repeated recursively until a stopping criterion is met, such as a maximum tree depth or a minimum number of samples in a leaf node.The equation for information gain is as follows:Random forest = Entropy(parent) - (Weighted average) * Entropy(children)where:Entropy(parent) is the entropy of the target variable before the splitEntropy(children) is the entropy of the target variable in each child node after the split(Weighted average) is the weighted average of the entropy of the children, weighted by the size of each child relative to the parent node

- Entropy is a measure of the impurity or disorder of a set of data. In the context of Random Forest, entropy is often used as a criterion to split the data at each node of a decision tree. The goal of the split is to reduce the entropy of the target variable, which in turn increases the purity of the resulting subsets.

-

- 4)

- Support Vector Machine (SVM ): SVM is a supervised learning algorithm that can be used for both classification and regression tasks. SVM can handle imbalanced data by adjusting the class weight parameter, which assigns a higher weight to the minority class. The goal of SVMs is to find the optimal hyperplane that maximally separates the data points of different classes. The hyperplane is chosen such that the margin between the closest data points from each class is maximized. The data points that lie closest to the hyperplane are called support vectors, hence the name "support vector machines".

- 5)

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN): KNN is a non-parametric, instance-based learning algorithm. In KNN, the classification of a new data point is determined by the class of its K nearest neighbours in the feature space. The value of K is a hyperparameter that is chosen by the user. Typically, larger values of K result in smoother decision boundaries, while smaller values of K can capture more local details in the data. It can handle imbalanced data by adjusting the number of nearest neighbours, which controls the decision. It can be used for both classification and regression tasks. However, it has some limitations, such as its sensitivity to the choice of distance metric and the curse of dimensionality (i.e., its performance can degrade in high-dimensional spaces). Additionally, KNN requires a large amount of memory to store the entire training dataset for each prediction.

- 6)

- Gaussian Naive Bayes: GaussianNB is a probabilistic algorithm that is commonly used for classification tasks. It is a variant of the Naive Bayes algorithm that makes the assumption that the features are normally distributed, and it is called "naive" because it assumes that the features are independent of each other. It can be used for imbalanced datasets, but its performance may be affected by the degree of imbalance in the data. Like any other classification algorithm, GaussianNB can produce biased results when dealing with imbalanced data, as it is likely to be biased towards the majority class.

- 7)

- Bernoulli Naive Bayes: BernoulliNB is another variant of the Naive Bayes algorithm that is commonly used for binary classification tasks, where the features are binary variables (taking values of either 0 or 1). Bernoulli Naive Bayes is a type of Naive Bayes algorithm that is used for binary classification problems, where the input variables are binary. One of the main advantages of using Bernoulli Naive Bayes is its simplicity and efficiency. It is a fast algorithm that requires relatively little memory and can be easily trained on large datasets. Additionally, it is relatively robust to irrelevant features and noise in the data, making it a good choice for real-world applications. Another advantage of Bernoulli Naive Bayes is that it can handle high-dimensional datasets with ease. This is because it models the conditional probability of each feature given the class label separately, allowing it to handle a large number of features without requiring a large amount of training data. Overall, Bernoulli Naive Bayes is a powerful and widely-used algorithm that is particularly useful for binary classification problems, such as text classification. It is fast, efficient, and robust, making it a good choice for real-world applications with large datasets. Bernoulli Naive Bayes (BernoulliNB) can handle imbalanced data to some extent, but its performance may be limited if the dataset is severely imbalanced.

- 8)

- Voting Classifier: The voting classifier [22] is an ensemble learning method that combines the predictions of multiple base models to make a final prediction. Voting Classifier is a type of ensemble learning technique in which multiple models (classifiers) are combined to improve the performance of the overall system. It works by aggregating the predictions of multiple base classifiers and combining them into a single prediction. The main reason for using a Voting Classifier is to improve the overall accuracy and robustness of the model. By combining multiple models, the Voting Classifier can reduce the risk of overfitting and bias that can occur when using a single model. Another advantage of using a Voting Classifier is that it can handle different types of models. For example, you can combine the predictions of a logistic regression model, a decision tree model, and a random forest model into a single prediction. This can be particularly useful when you have different types of data or when different models perform better on different subsets of the data. Overall, the Voting Classifier is a powerful technique that can help improve the accuracy and robustness of your model and is particularly useful when dealing with complex data or when you have a variety of models to choose from. In our case, we are considering combining Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest (Information Gain), Random Forest (Entropy), Support Vector Machine, K-Nearest Neighbors, Gaussian Naive Bayes, and Bernoulli Naive Bayes using a voting classifier.

- i.

- Resampling techniques: Techniques such as oversampling the minority class, undersampling the majority class, or using a combination of both, called SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique), can be used to balance the data and reduce the false negatives and false positives.

- ii.

- Change the threshold: The threshold of a classification model is the point at which predictions are classified as positive or negative. By adjusting the threshold, one can either increase the recall of the model at the expense of precision or increase the precision of the model at the expense of recall.

- iii.

- Ensemble models: Combining multiple models can help reduce false negatives and false positives by averaging their predictions and reducing the variability in their results.

- iv.

- Cost-sensitive learning: Assign different costs to different types of misclassification errors and adjust the model's learning algorithm to minimize the overall cost.

- v.

- Anomaly detection techniques: Utilizing techniques such as clustering, density-based methods and isolation forest can help in reduce false positives and false negatives.

- vi.

- Using different models: Using models such as Random Forest, XGBoost and LightGBM, can also help reduce false positives and false negatives.

- vii.

- Hyperparameter tuning: Optimizing the model's hyperparameters, such as learning rate and regularization strength, can help improve its performance and reduce false positives and false negatives.

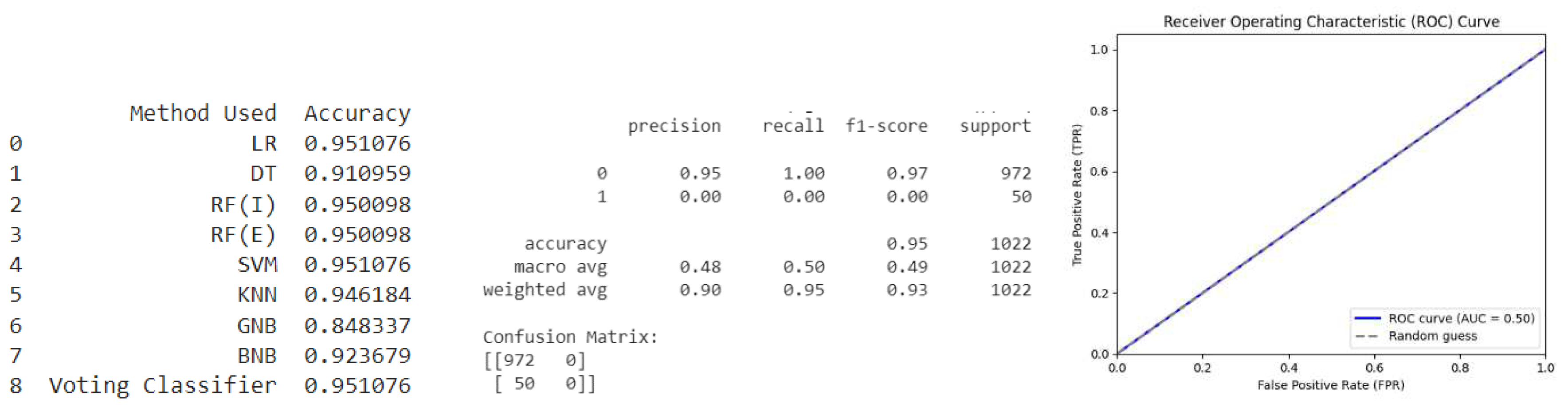

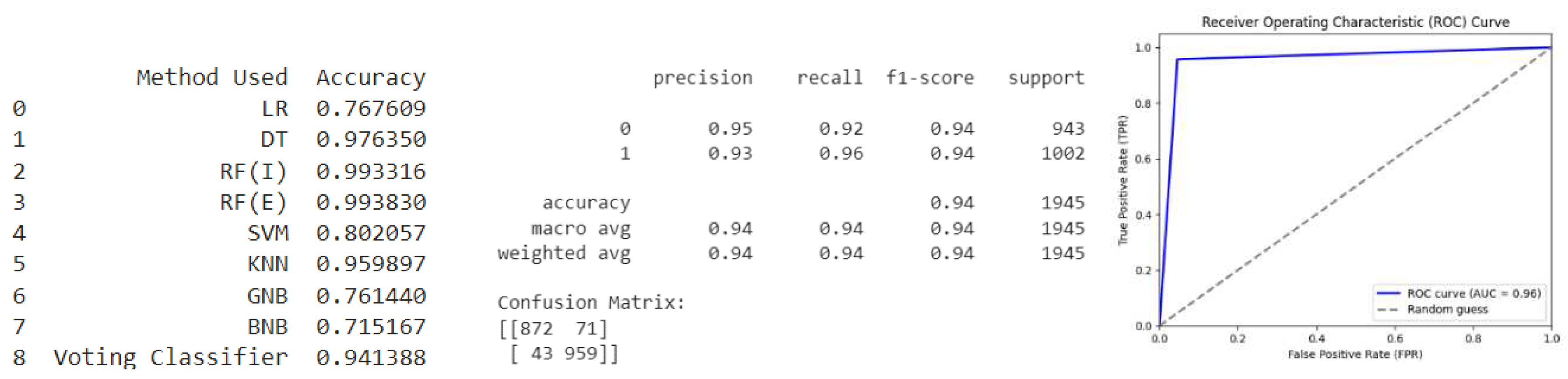

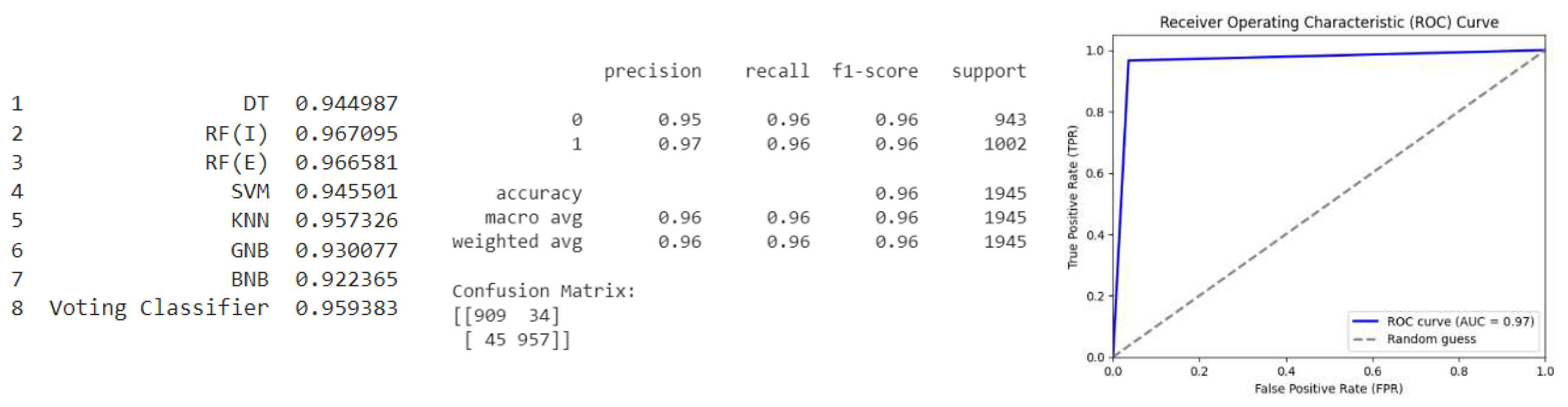

6. Results and Analysis

- Precision: In terms of all positive predictions (TP + FP), precision is the percentage of true positive predictions (TP) among all positive predictions. In other words, precision measures how often the model correctly identifies positive instances. High precision means that the model makes very few false positive predictions. This is useful when the cost of false positives is high (e.g., in medical diagnosis, predicting a condition that does not exist).

- Recall: Recall counts the percentage of accurate positive predictions (TP) among all instances of positive data (TP + false negative predictions (FN)). In other words, recall measures how often the model correctly identifies actual positive instances. High recall means that the model is able to correctly identify most of the actual positive cases. This is useful when the cost of false negatives is high (e.g., in medical diagnosis, missing a disease that exists).

- F1-score: The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, giving equal weight to both metrics. It provides a single value that summarizes the model's performance, with 1 being the best possible value and 0 being the worst possible value. The F1 score is a good metric to use when the goal is to balance precision and recall, it is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, which gives more weight to the lower value, this means that if either precision or recall is low, the F1 score will be low as well. In cases where the dataset is balanced, precision and recall have similar importance, so the F1 score is a useful metric to assess the model’s performance. However, when the dataset is imbalanced, it could be more important to have higher precision or higher recall, depending on the cost of false positives/false negatives. In those cases, it is important to consider both precision and recall as well as the F1 score. The F1 score is especially helpful when the distribution of classes in the dataset is imbalanced, which is a common scenario in many real-world applications.

- Support: Support refers to the number of instances belonging to each class in the dataset. Support is important to consider in model evaluation because it helps in providing the context for the performance metrics. For example, if the precision for a class is very high but the support is very low, it may not be very meaningful because there are only a few instances of that class. On the other hand, if the precision is high and the support is also high, it implies that the model is doing well on a larger number of instances in that class.

- Accuracy: Accuracy measures the proportion of correct predictions among all predictions made by the model.

- A confusion matrix is a table that is often used to describe the performance of a classification algorithm. It is a table with four different rows and columns that reports the number of true positives (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN), and false negative (FN). The importance of a confusion matrix in model evaluation is that it allows one to see how well the model can correctly predict or classify the different classes. It also provides insights into the types of errors that the model is making, which can be useful for further improving the model. Additionally, it allows for the calculation of various performance metrics, such as precision, recall, and F1 score, which can be used to compare the performance of different models.

- i.

- The ROS (Random Over-Sampling) technique has a slightly lower accuracy of 94% compared to the baseline, but it significantly reduces false negatives to 43, resulting in a higher ROC score of 0.96. However, it comes at a cost of 72 false positives.

- ii.

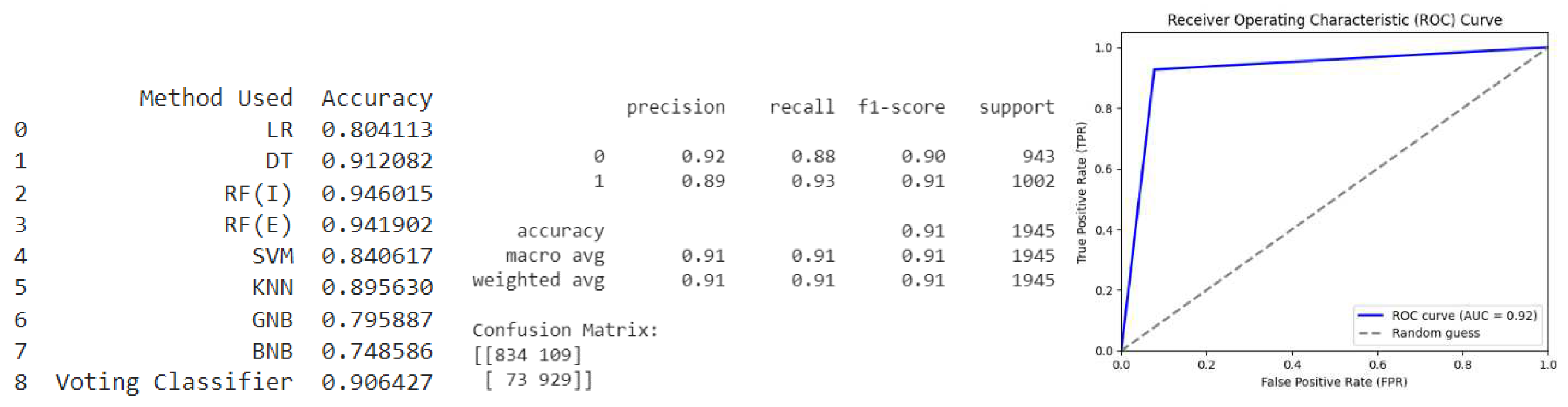

- The SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) technique has an even lower accuracy of 91% compared to the baseline, with a high number of false positives and false negatives, resulting in an ROC score of 0.92.

- iii.

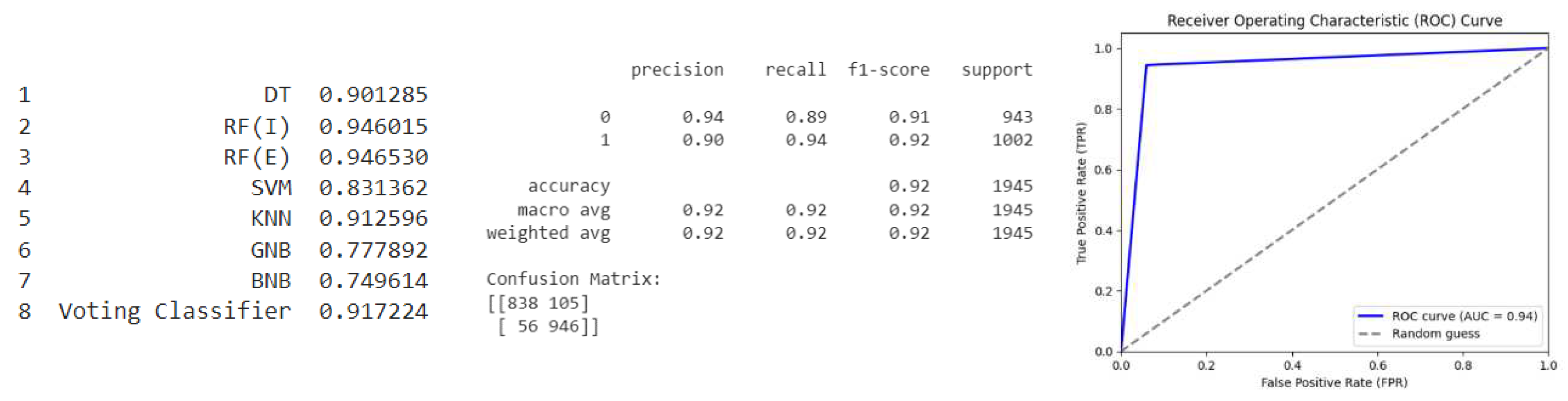

- The SMOTENC (SMOTE for Nominal and Continuous) technique has a slightly better accuracy of 92% compared to SMOTE, with a lower number of false positives and false negatives, resulting in a higher ROC score of 0.94.

- iv.

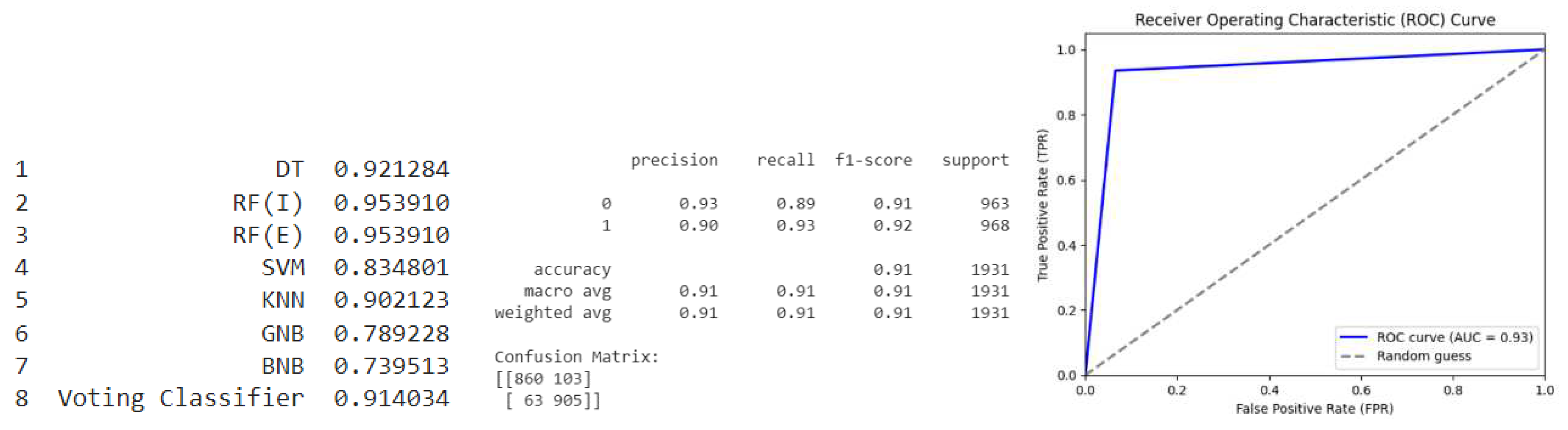

- The ADASYN (Adaptive Synthetic) technique has a similar performance to SMOTENC, with an accuracy of 91%, a moderate number of false positives and false negatives, and an ROC score of 0.93.

- v.

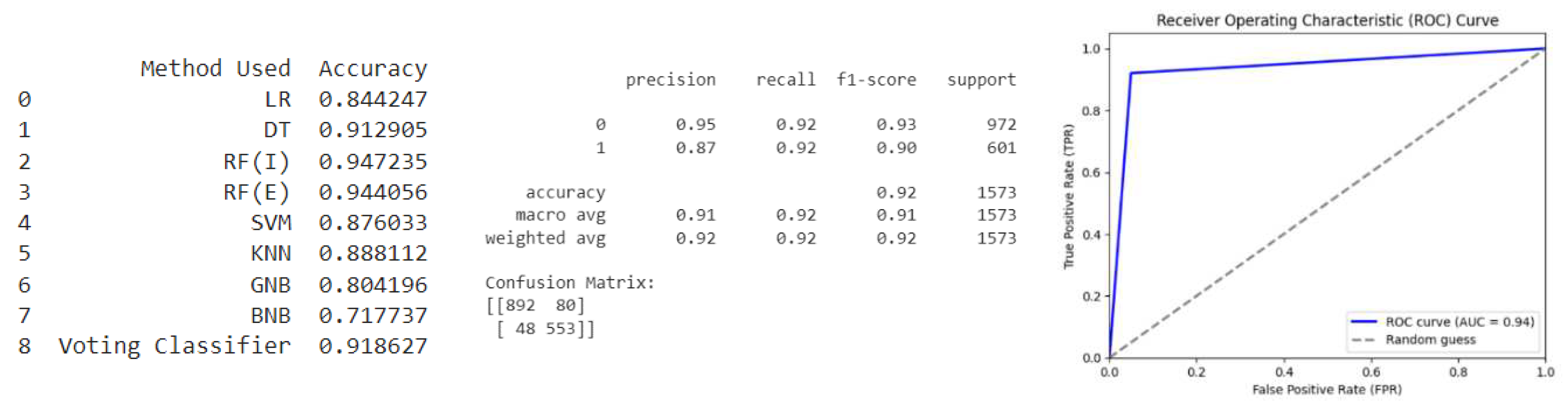

- The SVM SMOTE (Support Vector Machine SMOTE) technique has a similar performance to SMOTENC and ADASYN, with an accuracy of 92%, a low number of false positives and false negatives, and an ROC score of 0.94.

- vi.

- The K Means SMOTE technique has the highest accuracy of 96% among all techniques, with a low number of false positives and false negatives, resulting in the highest ROC score of 0.97.

- Limited specificity of diagnostic tests: Some diagnostic tests may have a lower specificity, which means they may detect a disease even when it is not present. This can lead to false negatives or positives.

- Disease manifestation: Some diseases may have a very non-specific presentation, making it difficult to differentiate from other conditions.

- Limited access to medical facilities: In some locations, patients may not have access to advanced medical facilities or experienced medical professionals, which can lead to false negatives or positives.

- Limited availability of diagnostic tests: Some diagnostic tests may not be widely available, especially in resource-limited settings, which can lead to false negatives or positives.

- Patient's characteristics: Some patient's characteristics, such as age, sex, or other underlying medical conditions, can affect the diagnostic test's results, leading to false negatives or positives.

- Human error: False negatives or positives can also occur due to human error, such as misinterpreting test results or not conducting the test properly.

7. Conclusion

References

- NPCDCS, “Guidelines for prevention and management of stroke,” Natl. Program. Prev. Control Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovasc. Dis. Stroke (NPCDCS), Gov. India Guidel. Prev. B. C. V, Silva, D. A. De, Macleod, M. R., Coutts, S. B., Schwamm, L. H., Davis, S. M., D, no. 61, pp. 1–16, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Khurana, M. Gourie-Devi, S. Sharma, and S. Kushwaha, “Burden of Stroke in India during 1960 to 2018: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Community Based Surveys,” Neurol. India, vol. 69, no. 3, pp. 547–559, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Dritsas and M. Trigka, “Stroke Risk Prediction with Machine Learning Techniques,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 13, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. I. Shoily, T. Islam, S. Jannat, S. A. Tanna, T. M. Alif, and R. R. Ema, “Detection of Stroke Disease using Machine Learning Algorithms,” 2019 10th Int. Conf. Comput. Commun. Netw. Technol. ICCCNT 2019, pp. 1–6, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Tazin, M. N. Alam, N. N. Dola, M. S. Bari, S. Bourouis, and M. Monirujjaman Khan, “Stroke Disease Detection and Prediction Using Robust Learning Approaches,” J. Healthc. Eng., vol. 2021, pp. 1–12, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Sailasya and G. L. A. Kumari, “Analyzing the Performance of Stroke Prediction using ML Classification Algorithms,” Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl., vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 539–545, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, D. Bian, J. Yu, H. Mao, M. Li, and D. Zhao, “Using machine learning models to classify stroke risk level based on national screening data ∗,” Proc. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. EMBS, vol. 2, pp. 1386–1390, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang et al., “Research Progress of Deep Learning in the Diagnosis and Prevention of Stroke,” Biomed Res. Int., vol. 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Khosla, Y. Cao, C. C. Y. Lin, H. K. Chiu, J. Hu, and H. Lee, “An integrated machine learning approach to stroke prediction,” Proc. ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min., pp. 183–191, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Fedesoriano, “Stroke Prediction Dataset,” Kaggle, 2021. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/fedesoriano/stroke-prediction-dataset (accessed Apr. 14, 2023).

- G. M. Weiss, “Foundations of imbalanced learning,” in Imbalanced Learning: Foundations, Algorithms, and Applications, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2013, pp. 13–41. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, A. K. C. Wong, and M. S. Kamel, “Classification of imbalanced data: A review,” Int. J. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell., vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 687–719, 2009. [CrossRef]

- “Over-sampling methods.” https://imbalanced-learn.org/dev/references/over_sampling.html (accessed Apr. 14, 2023).

- “Under-sampling methods,” imbalanced-learn Dev., 2022, Accessed: Apr. 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://imbalanced-learn.org/dev/references/under_sampling.html.

- R. Mohammed, J. Rawashdeh, and M. Abdullah, “Machine Learning with Oversampling and Undersampling Techniques: Overview Study and Experimental Results,” 2020 11th Int. Conf. Inf. Commun. Syst. ICICS 2020, pp. 243–248, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. V. Chawla, K. W. Bowyer, L. O. Hall, and W. P. Kegelmeyer, “SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique Nitesh,” J. Artif. Intell. Res., vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 321–357, 2002. [CrossRef]

- G. LemaˆıtreLemaˆıtre, F. Nogueira, and C. K. Aridas char, “Imbalanced-learn: A Python Toolbox to Tackle the Curse of Imbalanced Datasets in Machine Learning,” J. Mach. Learn. Res., vol. 18, pp. 1–5, 2017, Accessed: Apr. 16, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://jmlr.org/papers/v18/16-365.html.

- H. He, Y. Bai, E. A. Garcia, and S. Li, “ADASYN: Adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning,” in Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, 2008, pp. 1322–1328. [CrossRef]

- H. Sain and S. W. Purnami, “Combine Sampling Support Vector Machine for Imbalanced Data Classification,” in Procedia Computer Science, 2015, vol. 72, pp. 59–66. [CrossRef]

- F. Last, G. Douzas, and F. Bacao, “Oversampling for Imbalanced Learning Based on K-Means and SMOTE,” 2017. [CrossRef]

- “Logistic Regression.” https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/multivariate-logistic-regression-analysis (accessed Apr. 16, 2023).

- “Voting Classifier.” https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.ensemble.VotingClassifier.html (accessed Apr. 16, 2023).

- D. Kanellopoulos, S. Kotsiantis, and P. Pintelas, “Handling imbalanced datasets: A review Cite this paper Related papers Handling imbalanced datasets: A review,” GESTS Int. Trans. Comput. Sci. Eng., vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 25–36, 2006.

| Oversampling Techniques | Accuracy | False Positive | False Negative | ROC |

| Baseline | 95 | 0 | 50 | 0.5 |

| ROS | 94 | 72 | 43 | 0.96 |

| SMOTE | 91 | 109 | 73 | 0.92 |

| SMOTENC | 92 | 105 | 56 | 0.94 |

| ADASYN | 91 | 103 | 63 | 0.93 |

| SVM SMOTE | 92 | 80 | 48 | 0.94 |

| K Means SMOTE | 96 | 34 | 45 | 0.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).