1. Introduction

In fact, mosquitoes, globally account for more than 17% of all infectious diseases and cause more than 700,000 deaths annually, mostly in the tropical and subtropical countries [

1]. Among numerous species (>3600) of mosquitoes worldwide,

Anopheles gambiae,

An. arabiensis,

An. culicifacies,

An. stephensi (for malaria),

Aedes aegypti,

Ae. albopictus (for dengue, chikungunya, zika), and

Culex quinquefasciatus (for human lymphatic filariasis), and

Culex vishnui group (

Culex tritaeniorhynchus,

Culex vishnui and

Culex pseudovishnui) mosquitoes, are among nearly four dozen vector mosquito species responsible for major mosquito-borne diseases (MBDs) [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Climate change, referring to long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns, is the biggest threat to individual and public health of this century [

7,

8]! Such shifts can be natural, due to changes in the solar activity like global warming, oceanic phenomena such as El Nino Southern Oscillations (ENSO) or large volcanic eruptions causing the phenomena such as tsunamis etc. At the receiving end of the catastrophic climate oscillations are the poor, malnourished, diseased human populations especially tribal and other marginalized groups inhabiting forests, mountains, islands, deserts and coastal belts [

9]. Climate disturbances over a long period generally relate to exacerbation of fulmination of mosquito-borne disease cases [

10], but in a few cases, it could be seen to distantly associate with the depletion or elimination of a cases of a particular disease [

11]. Evidence have emerged that not only many of the mosquito vectors of different diseases have altered their emerging, reproductive, resting, flight, blood-feeding and disease pathogen transmission behaviours but the consequent mosquito-borne diseases have also changed in their epidemiological trends according to the cadence of ambient temperature and precipitation, in principle. Anthropization or human being-centered activities have obviously played a major role in bringing about this shift in disease epidemiology which poses serious challenges for their elimination from the country [

12].

However, to estimate the impact of climate change, vast knowledge on direct and indirect consequences is required worldwide, which is unfortunately vague. Many studies attempted to understand the consequences through mathematical modellings and understanding the transmission dynamics of vector borne diseases [

13,

14,

15]. In this context, compiling the available records, the present study attempts to find out the shifting of the epidemiological dynamics of mosquito-borne diseases due to climate change. In addition, the study has also looked at the challenges for their elimination from India.

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic literature search was performed on the various scientific databases platforms as PubMed, Scopus for various articles on the shifting epidemiological dynamics of mosquito-borne diseases for India sub-continent. Reference inclusion criteria consisted of peer-reviewed research studies, whereas the studies that did not addressed the criteria were excluded.

3. Results

Mosquito borne diseases status of India:

In India, there are currently 420 species of mosquitoes belonging to 50 genera under 11 tribes [

16,

17] of which significantly enough only four genera (Anopheles, Aedes, Culex and Mansonia) are important medically as many of their members carry parasites to the human host [

5,

18].

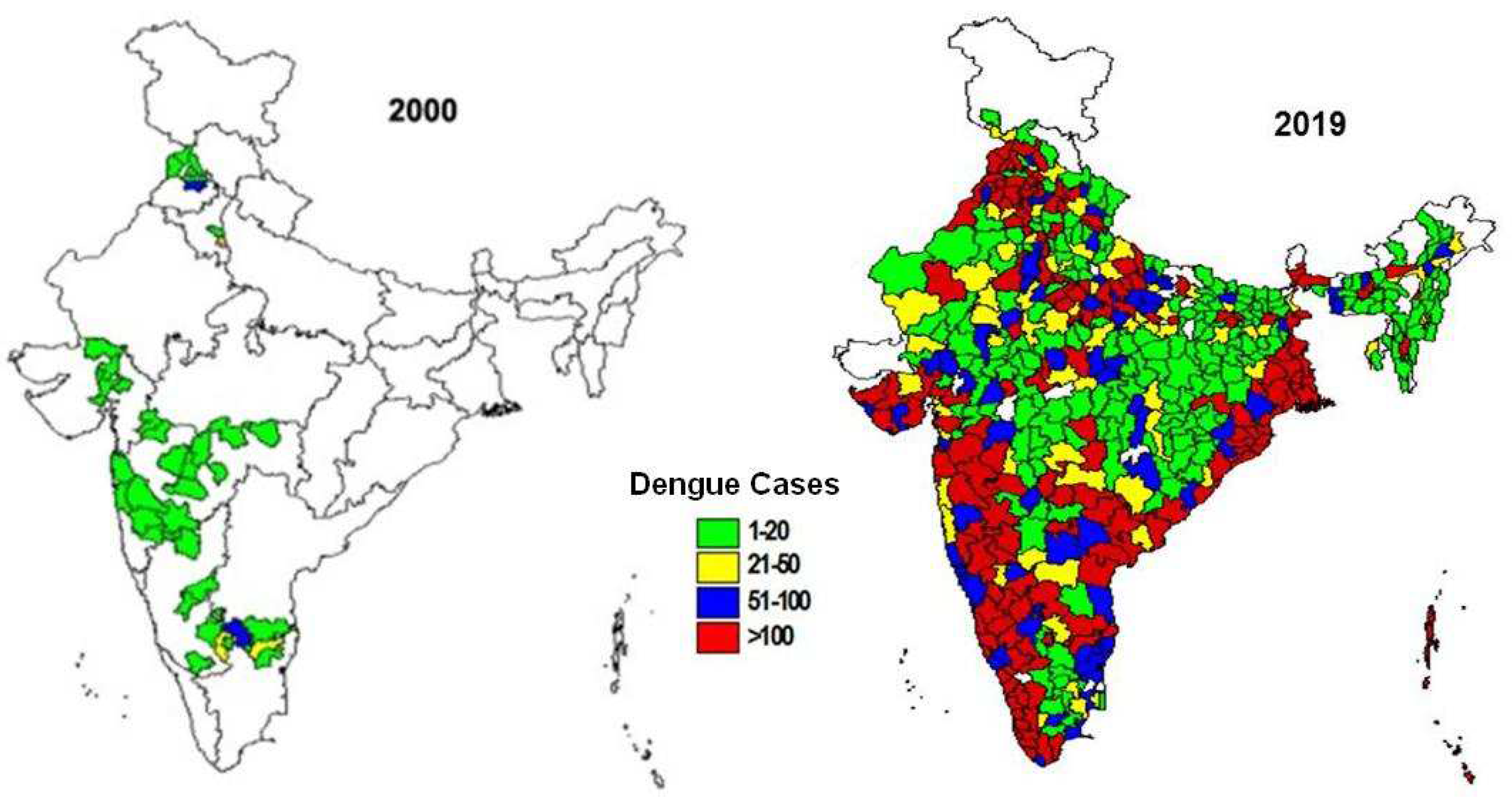

However, presently five major diseases are endemic such as, malaria, dengue, chikungunya, lymphatic filariasis and Japanese encephalitis [

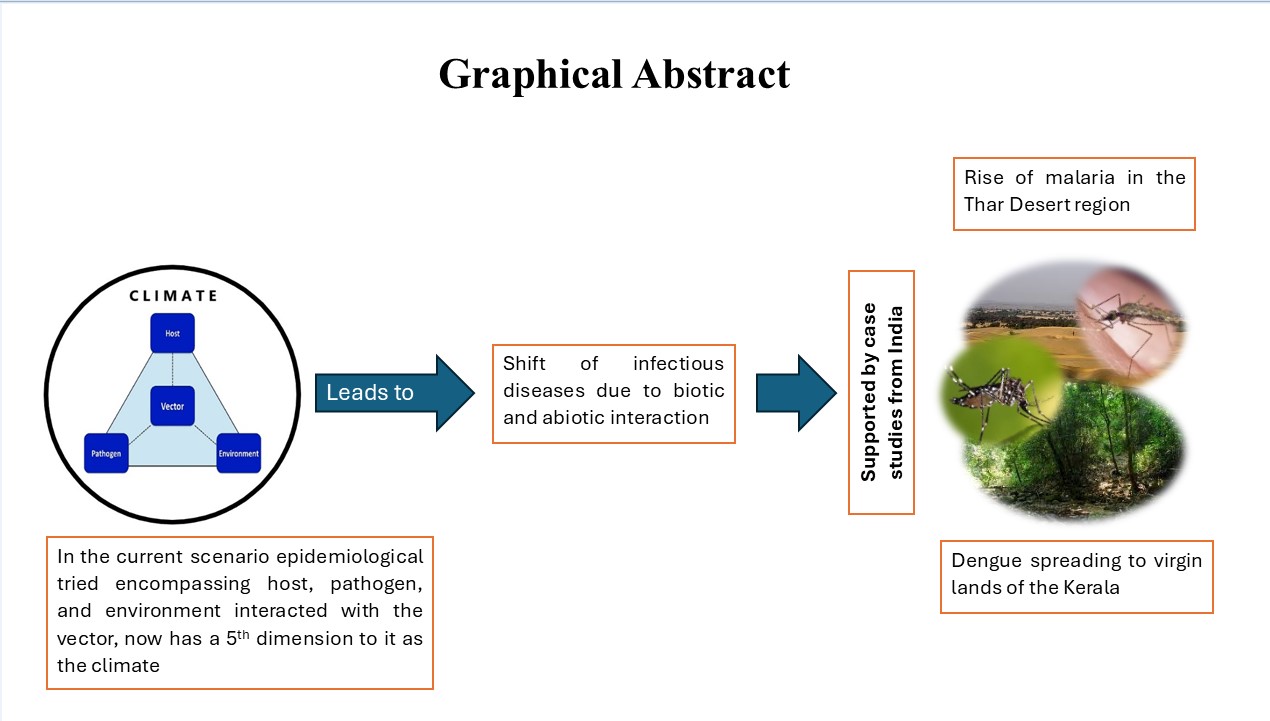

19]. Dynamics of these diseases in both time and space are significantly influenced under the impact of climate change, consequently bringing about a discernible shift in the degree of disease severity and transmission, vector biology including vectorial capacity, flight range and phenotypic plasticity, and the extent of human host-parasite interaction with the vector species, in the penetralium of the epidemiological triad of vector-borne diseases (

Figure 1).

India has suffered losses to the tune of INR 1200,00,00,00,000 (USD 120 bn) due to climate change induced natural calamities or disasters triggered by the climate change during past 24 years. Approximately 100 crore people have been affected by these harsh realities. These calamities are escalating year by year. In 2003 alone, 200 people had died, and 1.5 crore people were displaced due to sudden floods, avalanches, earthquakes and glacial lake outburst in Sikkim. In 2022, according to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data, 2% of the overall deaths in India were ascribed to climate change. In 2015 India faced a spate of ten major flood events. According to Central Water Commission, seven large water lakes have dried completely, six of which lie in south India. At the same time water capacity in 150 large-sized water sources have reduced to a maximum of 33% of their potential to store in 2023, due to erratic and less amount of rainfall, compared to 82% during 2022 [

20].

4. The drivers behind transmission:

4.1. Anthropization:

Humans have always changed their environments [

21]. Since 1800s, human activities or anthropization have been the main driver of climate change, primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas leading to the increased transmission of mosquito borne diseases Moreover, human activities, forest clearance eliminates the

Aedes breeding sites in tree holes, reducing yellow fever but favours the breeding of

Anopheles mosquitoes, increasing the chance of malaria disease. Human behavioral and cultural patterns, use of cisterns, pit latrines, water storage pots, cemetery urns and other human made storage containers of water potentially increasing the proliferation of

Aedes aegypti that originally breed in the tree holes of forests, thereby increasing the transmission rate of yellow fever and dengue [

14].Consequently, ever-increasing environmental intervention in the form of deforestation, irrigation and other infrastructural projects, urbanization, and pollution and its resultant impact – global climate change – is leading to the emergence of new infectious, particularly mosquito-borne, diseases. The Thar Desert in the western India and the Western Ghats in the southern India are burning examples and a perfect model as to what human intervention can do to conflagrate mosquito-borne diseases like malaria and dengue.

4.2. The climatic changes:

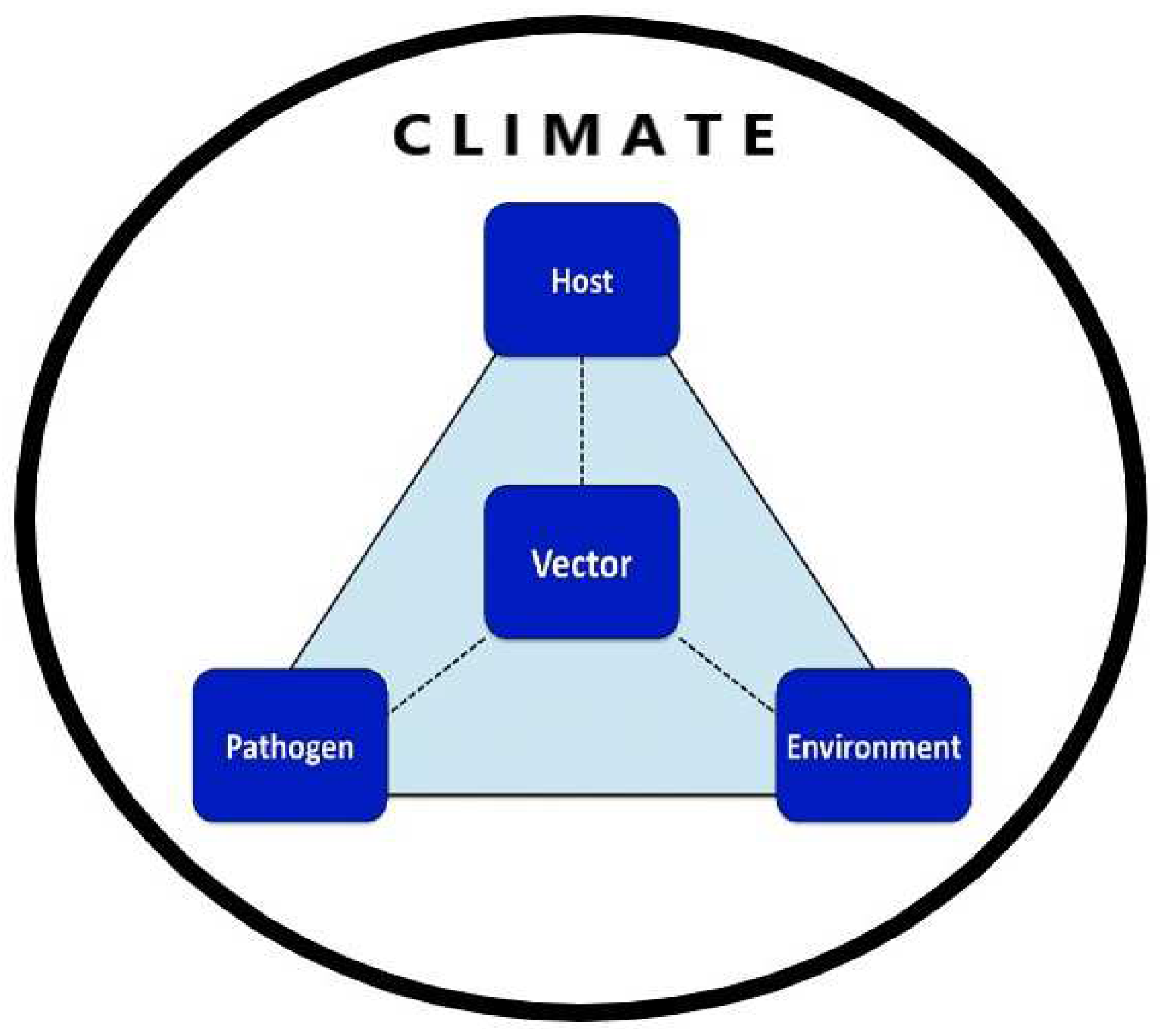

Climate change affects all three components of the epidemiological tried: humans (the host), pathogens (the causative agent), and their transmitters (the vectors)-all functionally interdependent in the presence of environment (

Figure 1) [

22,

23].

Even though by the turn of the last century the global temperature has shot up high by 1.1°C, it is currently estimated that average global temperatures will have risen by 1.0-3.5°C by 2100, increasing the likelihood of many mosquito-borne diseases. Climate, vector ecology and social economics vary from continent to continent, so a regional or national analysis is needed. The greatest effect of climate change on disease transmission is likely to be observed at the extremes of the range of temperatures at which transmission occurs. For many diseases such as, for example, malaria these lie in the range 14-18°C at the lower end and ca. 35-40°C at the upper end [

22,

24] (

Figure 2).

Temperature increase within a lower range has a significant and nonlinear effect on the extrinsic incubation period thus influencing disease transmission. On the contrary, at the higher end of the temperature continuum, transmission may cease. However, at a temperature around 30 –32°C, vectorial capacity can increase substantially owing to a reduction in the extrinsic incubation period, despite a reduction in the vector’s survival rate. Mosquito species like

Anopheles culicifacies, An. stephensi, Culex quinquefasciatus,

Aedes aegypti and

Ae. albopictus are responsible for transmission of deadly and/or debilitating vector/mosquito-borne diseases and are sensitive to temperature changes as immature stages in the aquatic environment and as adults. If water temperature rises, the larvae take a shorter time to mature and consequently there is a greater capacity to produce more offspring during the transmission period. In warmer climates, adult female mosquitoes digest blood faster and feed more frequently, thus increasing transmission intensity. Similarly, malaria parasites and viruses complete extrinsic incubation within the female mosquito in a shorter time as temperature rises, thereby increasing the proportion of infective vectors. Warming above 34°C generally has a negative impact on the survival of vectors and parasites [

22].

Another factor, in addition to the direct influence of temperature on the biology of vectors and parasites, is the precipitation. The changing precipitation patterns can also have short- and long-term effects on vector habitats. Increased precipitation has the potential to increase the number and quality of breeding sites for vectors such as mosquitoes, ticks and snails, and the density of vegetation, affecting the availability of resting sites. Rainfall, or the lack of it, also plays a crucial role in malarial and dengue epidemiology. Rainfall not only provides the medium for the aquatic stages of the malarial mosquito’s life cycle but also increase the relative humidity and hence longevity of adult mosquito. In this disease epidemiology, rainfall determines the duration of longevity of disease prevalence. The introduction of large-scale irrigation schemes has also reduced the significance of local rainfall in vector/mosquito-borne disease epidemiology to some extent. However, because a shortage of rainfall may be a limiting factor in the ability of the vector to breed, we assumed that a minimum seasonal average amount of precipitation is needed for mosquito development. Evidence for the past and current impacts of inter-annual and inter-decadal climate variability on mosquito-borne diseases suggest that these diseases will be exacerbated in future, shedding light on possible future trends [

24].

5. Climate change impact in shifting the global epidemiological dynamics of mosquito-borne diseases

In recent years both the climate change and the have been under strict scrutiny and a climate dimension has been demonstrated virtually in all vector-borne diseases [

25]. While already more than half of the world’s population is currently at risk of vector-borne diseases, an additional 4.7 billion people may be at risk of the vector-borne diseases malaria and dengue by 2070 [

26]. Dengue recorded a historic high of over 6.5 million cases in 2023, with more than 7300 dengue-related deaths. Global warming can extend the geographic spread of vectors and the disease transmission season. Increased rainfall and drought can increase the amount of standing water, creating more breeding areas for vectors. There are several other drivers for climate change each one of which may have an impact on the conflagration of the mosquito-borne diseases.

Global climate change is a phenomenon that is now considered strongly associated with human activities. Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, which have remained steady at 180-220 ppm for the past 420,000 years, are now close to 370 ppm and rising [

27]. Public health, particularly with reference to infectious diseases, has not escaped the global warming debate and it is a widely held view that in future global warming and climate change will more deleteriously affect infectious disease like malaria and dengue. Direct effects of the anticipated changes in global and regional temperature, precipitation, humidity and wind patterns resulting from anthropogenic climate change are the factors which have an impact on the vectors’ reproduction, development rate and longevity. These factors would be thus associated with changes in vector density. In general, the rate of development of a parasite accelerates as the temperature rises. Indirect effects of climate change would include changes in vegetation and agricultural practices which would mainly be caused by temperature changes and trends in rainfall patterns. These changes either promote or inhibit disease transmission by their association with increased or decreased vector density.

Shifts in mosquito-borne diseases epidemiology under the impact of climate change have emerged as a significant concern for global public health. Mosquito-borne diseases, such as malaria, dengue fever, Zika virus, and chikungunya, are transmitted to humans primarily through the bites of infected mosquitoes. As temperatures rise, island ecosystems are threatened submergence (e.g., Maldives) and new desertic ecosystems evolve (e.g., Aral Sea). In recent decades global distribution of

Aedes vectors and the deadly diseases transmitted by them have attracted the global attraction [

28]. The 2005 epidemic of chikungunya in India was a cause of climatic changes and other related factors thus the mosquito populations and diseases they carry are responding in complex ways. Similarly, [

29] mentioned malaria cases in Mizoram are directly related to an increase ~0.8°C rise in the minimum temperature leading to steadily increase of cases from 2007 to 2019.

This shift is evident in the intensification of infection, changes in disease seasonality, and the alteration of geographical distributions. Climate change, characterized by rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and changing ecosystems, can profoundly influence the distribution, behaviour, and prevalence of disease-carrying mosquitoes, thereby reshaping the landscape of these diseases.

6. Problem Identification

6.1. Intensification of Infection:

6.1.1. In Time (Based on disease seasonality or various mosquito-borne diseases (MBDs)):

Climate change can lead to an intensification of mosquito-borne infections in different seasons, affecting the transmission dynamics of various MBDs. Key points include:

- (i)

Extended Transmission Seasons: Warmer temperatures can prolong mosquito activity periods, extending the time window during which diseases can be transmitted. Diseases like dengue, chikungunya, and Zika, which are transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, may experience extended transmission seasons due to favourable climatic conditions. Rising temperatures contribute to the expansion of the transmission seasons for diseases like dengue. Studies in India reveal that increasing temperatures are associated with the lengthening of the dengue transmission period, leading to a greater window for disease spread.

- (ii)

Shift in Transmission Peaks: Changing climate patterns can influence the peak periods of disease transmission. For example, regions that previously experienced seasonal malaria transmission may see shifts in the timing of transmission due to altered rainfall patterns and temperature fluctuations [

31].

6.1.2. In Space (Shift in geographical distribution of MBDs in India)

Climate change is causing shifts in the geographical distribution of mosquito vectors and the diseases they transmit in India; this shift is evident in several ways:

- (i)

Expansion to New Regions: As temperatures rise, previously unsuitable areas may become suitable for mosquito breeding. Regions with cooler climates might witness an expansion of mosquito populations and the diseases they carry. Malaria’s endemic nature in the country is observed across diverse ecosystems including forests, rural plains, urban regions, coastal areas, and arid zones. The connection between ecosystems and the prevalence of vector and parasite species plays a pivotal role in malaria transmission within a region. The distribution of vector species demonstrates distinct patterns across the country, influenced by factors such as land use and the types of breeding sites available. For instance, the topography and climatic conditions in forest ecosystems not only impact vector species prevalence but also influence the longevity of these vectors 32].

- (i)

Ecosystem and species changes: An example of ecosystem changes and vector species plasticity in

Anopheles culicifacies and An. fluviatilis are species contributing malaria cases incidence other than

An. stephensi in India, and specifically, in ecosystems characterized by hills and forests,

An. fluviatilis emerges as the primary vector, while

An. culicifacies takes a secondary role. Conversely, in plain and forest-fringe regions,

An. culicifacies takes on the role of the predominant vector species whereas in certain flat areas

, An. culicifacies exclusively transmits malaria. Extensive studies on the biology and bionomics of these vectors in India consistently indicate that both

An. culicifacies and

An. fluviatilis predominantly rest indoors and exhibit indoor biting behaviour [

33]. In addition, the higher altitudes that were traditionally less hospitable to mosquito vectors could experience an increase in disease transmission as warmer temperatures allow mosquitoes to thrive at these elevations.

- (iii)

Coastal Vulnerabilities: Coastal areas may become more vulnerable to diseases like dengue and chikungunya due to rising sea level and warmer temperatures, which create conducive breeding environments for mosquitoes. Climate change is altering the landscape of mosquito-borne diseases, intensifying infection dynamics both in terms of time and space.

About 5% of mosquito species have adapted to undergo preimaginal development in brackish and saline waters. Water with salinity levels below 0.5 ppt (parts per thousand) is considered fresh, while those ranging from 0.5 to 30 ppt are brackish, and above 30 ppt are saline. A significant number of mosquitoes that can tolerate varying salinity levels play crucial roles as vectors of human diseases. The larvae of salinity-tolerant mosquitoes possess cuticles that exhibit reduced water permeability compared to their freshwater counterparts. Additionally, their pupae feature thickened and sclerotized cuticles that prevent the passage of both water and ions [

34]. The transmission of mosquito-borne diseases in coastal areas are influenced not only by global climate change, which leads to shifts in temperature, rainfall, and humidity, but also by the rising sea levels [

35,

36].

Longer transmission seasons, shifts in peak transmission periods, and expanded geographical distributions are all evident consequences. This has significant implications for public health, as new populations become exposed to diseases and health systems need to adapt to changing disease patterns. Addressing these challenges requires integrated efforts involving climate science, epidemiology, entomology, and public health to develop proactive strategies for disease prevention, surveillance, and control [

37,

38].

6.2. Possibilities of Unanticipated Emergence of New Pathogens – Adaptive Potential of Vector Mosquitoes

The adaptive potential of vector mosquitoes allows them to respond to changing environmental conditions, leading to the unanticipated emergence of new pathogens. This phenomenon has significant implications for public health, as it can lead to the spread of diseases to new regions, ecosystems, and populations. The epidemiological characteristics of dengue reveal a rising pattern in countries where the disease is endemic. Recent findings indicate that dengue is the arbovirus with the swiftest expansion on a global scale, posing a threat to approximately half a billion individuals worldwide [

39].

Here, we explore how the adaptive potential of vector mosquitoes can lead to the unanticipated emergence of new pathogens through increased distribution, the quest for new regions or ecosystems, and the diversification of breeding habitats.

6.3. Increased distribution

Vector mosquitoes are not confined to specific geographical areas. Their adaptive potential enables them to expand their distribution beyond their historical range. Climate change, urbanization, and globalization facilitate the movement of vector mosquitoes to new areas. As these mosquitoes migrate, they can encounter new hosts and environments, potentially leading to the transmission of pathogens to previously unexposed populations. For instance, the invasion of

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes to new regions has been linked to the spread of diseases like dengue and Zika. The dengue virus serves as a prominent illustration of how the interplay among swift pathogen evolution, human mobility, and evolving vector ecology has propelled its emergence [

40].

6.4. Diversifying Breeding Habitats

The adaptive potential of vector mosquitoes presents a dynamic and complex challenge in the realm of disease emergence. The unanticipated emergence of new pathogens can result from the expanded distribution of vectors, their exploration of new regions or ecosystems, and their ability to adapt to diverse breeding habitats. Addressing this challenge requires an interdisciplinary approach that combines entomology, epidemiology, ecology, and public health. Monitoring vector behaviour, understanding their adaptive responses, and anticipating potential disease shifts are essential for devising proactive strategies to mitigate the impact of unanticipated pathogen emergence and to safeguard global public health [

41].

7. Linkages of vector preponderance and disease epidemics with climatic variabilities

Climatic changes in time scales are of different kinds and intensities. The El Nino seasonal variations occupies a special place in the global weather formation, even though the ENSO (El Nino Southern Oscillations) is one of several natural variabilities. The El Nino events are linked with rainfall and temperature extremes and are a major cause of inter annual climate variability. During the 1997 El Nino event a postulation was cast for increased risk of serious drought in India, Australia, Brazil and east Africa, on one hand, and heightened the danger of torrential rains and flood in American deserts from Peru to California, and of forest fire in Indonesia. Studies have already proved a strong correlation between outbreaks of malaria and the ENSO in the Thar Desert, in northwestern India [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. In fine, therefore, it has become more than crystal clear that all the vector-borne diseases have a very strong correlation with climatic variabilities.

According to [

47] based on projected population and climate change worldwide, nearly 5-6 billion people (50-60% of the projected world population) will be at risk of dengue fever transmission compared with 3-5 billion people (35% of the population) if climate change did not happen. Based on a model developed by them, they have suggested that excessive resource consumption in rich countries should be addressed to avoid this increase in the proliferation of dengue fever.

8. Climate sensitivity and mosquito-borne diseases

With regard to the mosquito-borne diseases, a dynamic shift has been witnessed over past several years. In India, most of the arthropod-borne infections have been found increasing their geographic ranges; malaria, particularly

P. falciparum-dominated malaria, has formed new foci and the Thar Desert region is the most recent classical example if its exacerbation [

22,

48], while dengue including dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS), too, has spread to hitherto nearly virgin lands of the Kerala State in South India and the Thar Desert in north-western Rajasthan. It is well documented now that global rise of temperature has induced a serious vector mosquito like

Aedes aegypti increase its altitudinal distribution range by as much as 1000 ft in the lower Himalayas in India [

49].

Some important mosquito-borne diseases like malaria, dengue and certain encephalitis are best demonstrable to have a working interaction with the environment and/or climate change.

8.1. Malaria

Malaria has been a scourge in India for times immemorial. It is estimated that by the beginning of the 20th century close to 75 million people suffered with malaria while approximately one million people had died annually due to the disease. Malaria is largely controlled in the country, but challenges of various nature continue to face the nation, and most crucial challenge is posed by the climate change which has resulted in epidemiological scenario of the disease in different parts of the country.

India contributed 1.7% of malaria cases and 1.2% deaths globally in the year 2021 [

50] and 79% of malaria cases in the South-East Asia Region (SEAR). The case load, though steady around 2 million cases annually in the late nineties, has shown a declining trend since 2002. The reported total malaria cases in 2021 are 1,61,753 and 90 deaths. The reported Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) cases declined from 11,33,005 in 1995 to 1,00,442 cases in 2021. The Pf % has gradually increased from 39% in 1995 to 63.10% in 2021. Overall, 86.2% decline in malaria cases and 76.6% decline in deaths were noted in 2021 compared to 2015 [

51].

8.1.1. Case study

The Thar Desert in western India is a glaring example as to how drastic climatic changes brought about in the region through mostly man’s own activities such as the massive Indira Gandhi Nahar Pariyojana (IGNP), world’s largest canal-based irrigation system in a desert ecosystem, could usher the deadly

Plasmodium falciparum dominated malaria in the region, in addition to the fears of plague and cutaneous leishmaniasis [

6,

11,

48].

The greatest discernible change the Thar Desert seemed to have undergone with a human interruption is the provision of extensive canalization - probably one of the world’s largest canal systems of its type in the desert ecosystem. Though, originally developed to boost the future prospects of agriculture in the virgin deserts and animal keeping through planned and sustained irrigation, nevertheless, due to multiple reasons associated with canal-water management, particularly those relating to formation of stagnant water bodies, the canal waters inadvertently became also the favorable breeding sites for a large number of vector mosquitoes [

52].

The changed physiography of the Thar Desert has also brought about an impact on another important vector-borne infection, cutaneous leishmaniasis, in respect of both the bionomics of sand fly vectors and the disease epidemiology. Interestingly, [

53] have demonstrated spread of dengue vector,

Aedes aegypti, in the interior of the typical Thar Desert environs, attributable to replacement of time-tested ’tanka’ (the underground water reservoirs) by the conduit-supplied canal water, and as a consequence the dengue vector found it convenient to breed in the discarded ’tanka’ and propagate in the desert which was struck by dengue epidemic in as latest as 2002.

The climate change in the Thar Desert has brought radical changes in its characteristic environment which became vulnerable to vector mosquitoes and the malaria parasites. It is no enigma to decipher the emergence of P. falciparum-dominated malaria in the interior of the Thar Desert supported by so many epidemics with high morbidity and mortality. A few possible interpretations were offered below:

- (i)

With the establishment of extensive canal-based irrigation in the interior parts of the Thar Desert, a far more serious vector of malaria, An. culicifacies, ushered in the xeric environments. This species being highly adaptive to new physiographic situations built up its density very fast under given circumstances of a large variety of breeding places in the IGNP area particularly the inevitable and numerous seepage water collections from the canals. What An. culicifacies lacks in its susceptibility to infection by P. falciparum, it compensates by its relatively much higher density, hence also vigorous and prodigious biting on human host

- (ii)

Anopheles stephensi, chronologically the oldest and most dominant vector of malaria in the typical sand-duned xeric environments of the Thar Desert, which traditionally bred only in the ’tanka’, the only major source of reserved potable water invariably present in every desert village and but transmitted ’desert malaria’ [

48] at a low ebb, without epidemics, shifted its breeding habits with the availability of extensive and varied breeding sites due to extensive canalization to compete with that of

An. culicifacies.

- (iii)

The massive Indira Gandhi Nahar Pariyojana, in continuation with the Ganga canal system and the Bhakra-Sirhind feeder canal system, together spanning over nearly 70 years of initiation, had attracted large labour forces from distant and often hyperendemic States like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. Such labour forces quite possibly brought along with them the parasite, possibly a resistant strain of P. falciparum, which in the non-immune population had the potential to spread and manifest fast in suitable climatic situations of IGNP-induced environment in a part of the Thar Desert. It had been pointed out that the 1994 outbreak of cerebral malaria in the Thar Desert proved fatal because the affected population had been exposed to the parasite for the first time; and

- (iv)

The resistant strain of P. falciparum inadvertently inveigled into the Thar interiors is uncontrollable by the normal regimen of the prescribed antimalarials.

8.2. Dengue fever

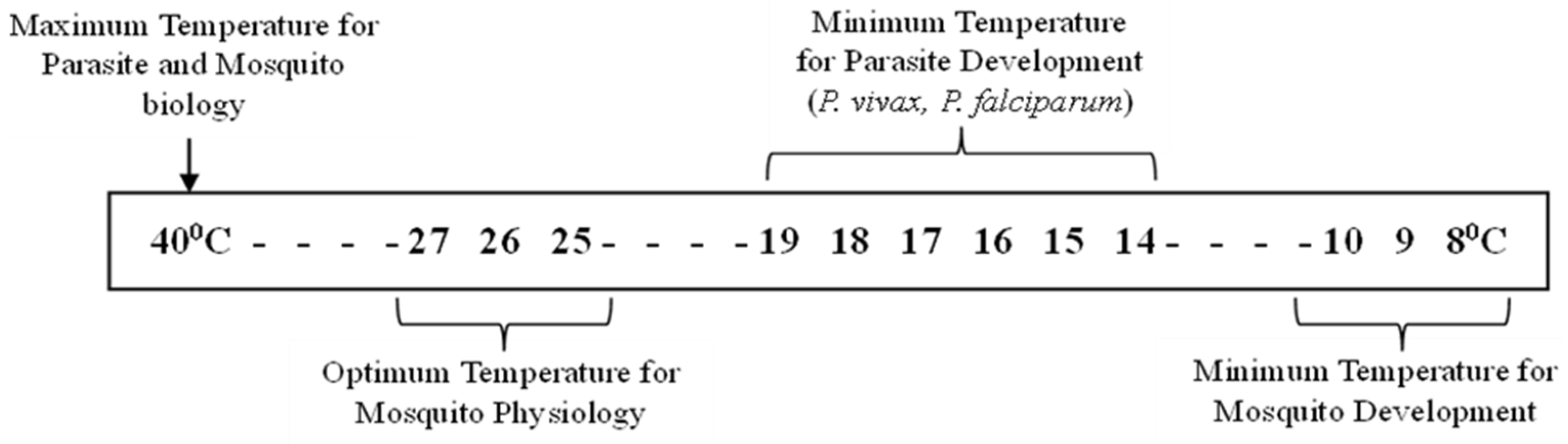

There are clear indications that an increase in ambient temperature in rather cooler areas, such as the lower outer scarps of Himalayas, has resulted in elevating the altitudinal distribution of the dengue vector, Aedes aegypti. Similarly, denudation of forest cover, comprising mainly rubber plantation supporting preponderance of another important dengue vector Ae. albopictus, in the Western Ghat region in Kerala state, coupled with the consequent increase in the average annual temperature, has obviously resulted in the vector’s spatial and temporal distribution over entire state in a short period of less than two decades.

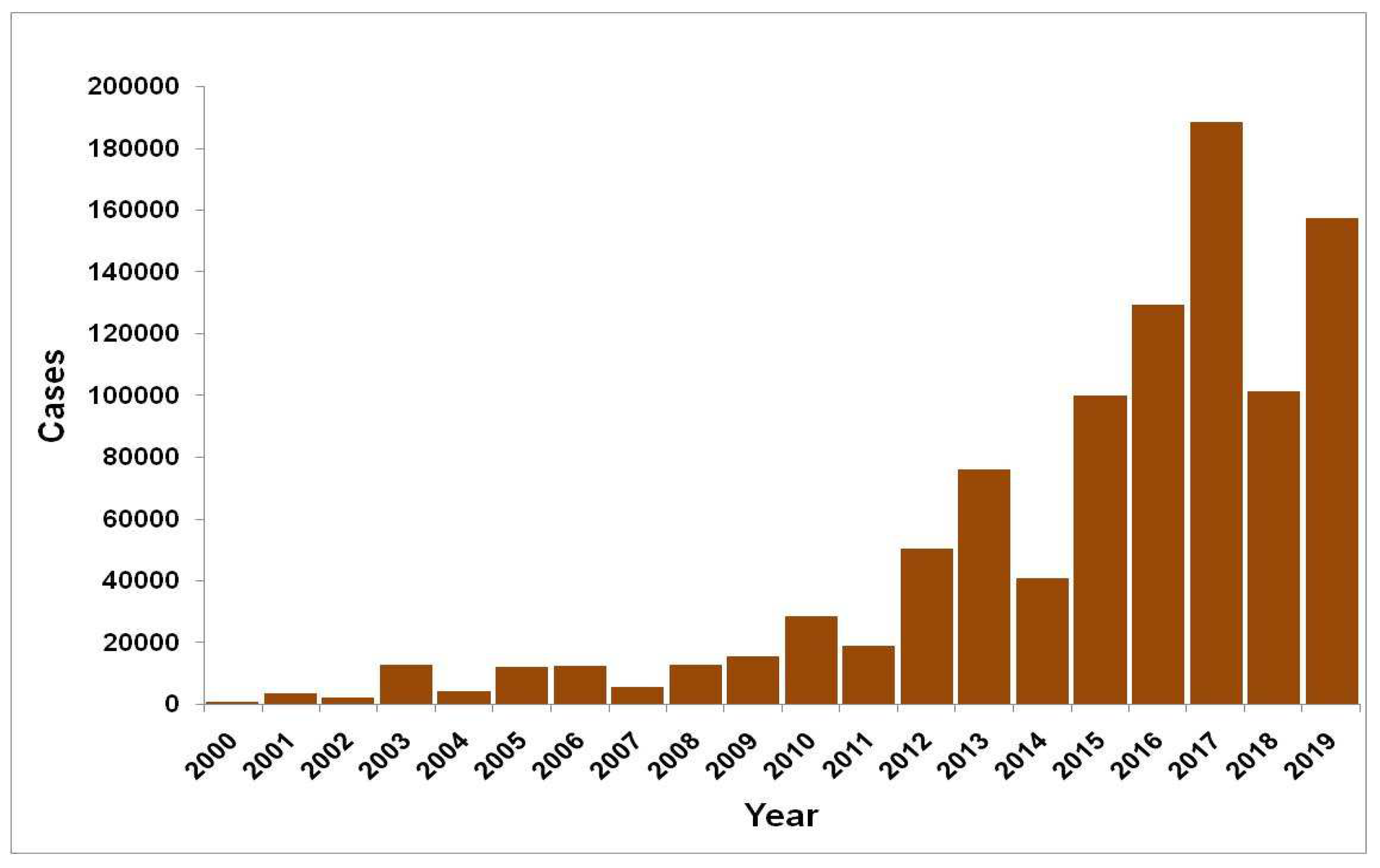

During last two decades, significant geographical spread of dengue has been observed with an increase in number of reported cases (

Figure 3). The number of states/union territories (UTs) reporting dengue cases increased from 8 in 2000 to 35 as there was an 11-folds increase in the number of dengue cases. Newer areas were reporting outbreaks every year including a few from high altitudes (like Bilaspur in Himachal Pradesh, Nainital, Dehradun in Uttarakhand from foothills of Himalayas [

54].

With the advent of 21st century repeated outbreaks of dengue were reported from many states of India as Andhra Pradesh, Delhi, Goa, Haryana, Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Puducherry, Punjab, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal, during 2003 onward culminating in 2017 (1,85,000 cases), followed by cases in 2019 (1,10, 473 cases and 86 deaths) between 1 January and 31 October 2022 only were reported (

Figure 4).

One of the best examples to demonstrate the impact of climate change on Dengue emergence is presented by the disease scenario in the Kerala state in southern India.

8.2.1. Case study: Kerala’s dengue story in the light of climate change

Kerala was a state without dengue before mid-1990s. However, for the first time, cases of dengue with some deaths were reported in 1997 [

22]. In the earlier cases presence of

Ae. aegypti (L.) was detected in these seropositive districts of Kerela, however in the later dengue infestation

Ae.

albopictus, both DEN-2 and DEN-3 serotypes were newly discovered altogether and found that

Ae. albopictus were able to transmit infection without the aid from the primary vector

Ae. aegypti and thus was a principal vector in dengue cases of Kerala [

22,

55,

56].

Therefore, it is very important to comprehend about the ecological and anthropization factors responsible to force this otherwise benign mosquito to come out of its sylvatic abode into the midst of the urban human congregation and turn up a vicious vector for the deadly dengue [

57].

A careful analysis of epidemics in Kerala illustrates that dengue most of the cases had erupted in the mountainous and sylvan environs of the Western Ghat ranges on the south-western edge of the peninsular India facing Arabian sea coast in Kerala of which it covers nearly 90% of the total landmass. Since 1950s Kerala has undergone an enormous change in respect of both its physiography/climate. Anthropogenic impacts brought about a discernible vicissitude in Kerala’s Forest cover, agricultural practices, traditional water harvesting, demography, urbanization and human mobility. Large scale deforestation has been occurring in the state since 1970s, mostly with a view to planting cash crops like rubber plantation. Kerala had an estimated forest cover of 44.45% in 1900 which, according to the recent satellite images, had reduced to 14.7% in 1983 and to a pathetic 9% at present. It is noteworthy that, along with coconut, rubber plantation occupies the largest land area in Kerala which support, among other types of phytotelmata, prodigious breeding of dengue vector,

Ae. Albopictus [

53,

57,

58,

59].

Aedes albopictus exhibiting a wide spectrum of breeding preferences with a clear-cut predilection for coconut shells/plastic cups (79.7%) deployed in collecting latex from the rubber trees.

Aedes albopictus breeding in cocoa pods (Theobroma cacao) has been widespread in Western Ghat forest fringe areas and its significance has been duly emphasized in preserving the vector density during high monsoon times when the main breeding habitats such as the latex-collecting cups tethered along the main trunk of the rubber tree are rendered unsuitable for breeding due to latter being turned upside down or covered with polythene sheets to avoid water collection in cups.

Ae. albopictus maintained two peaks of high density correlating with the two monsoon seasons. This observation was considerably substantiated by both the container larval positivity and the adult landing index for

Ae. albopictus. The container larval positivity was as high as 64.1-73.8% in June and 80-84.3% in December, the adult landing index too was correspondingly high in June (7.2-11) and December (7.1-7.8), respectively corresponding to the monsoon [

57].

Cyclic dengue epidemics in Kerala have been occurring since 2001, even though the first dengue report was brought on record from Kottayam district in 1997 with 14 cases and 4 deaths. It was followed by a more severe dengue outbreak with nearly 5-fold in 1998, again in the same district. In 2001, epidemic dengue resurged mainly in Kottayam, Idukki and Ernakulam reporting 70 cases, followed by 219 cases in 2002 with some deaths. The year 2003 experienced the severest epidemic till date yielding as many as 3546 confirmed cases (253-fold increase) and a toll of 68 human lives, spread for the first time all over the Kerala’s fourteen districts [

57].

Anthropization is often associated with the spatial and temporal distribution of Ae. albopictus in Kerala which tends to displace Ae. aegypti from its habitats. Three human activities could be reasoned and attributed to the spread of Ae. albopictus far from its original sylvatic abode in the Western Ghat in core to the coastal plains harboring congested human settlements: (i) massive deforestation during past three decades that forced Ae. albopictus to come out of its natural abode, (ii) development of human settlements along forest fringe areas where mosquito frequently fed on human blood peri-domestically and (iii) its potential for virus transportation through different modes.

8.3. Chikungunya

Chikungunya fever, caused by chikungunya virus (CHIKV), an alphavirus of Togaviridae family first described in 1952 in the Makonde Plateau, south-eastern Tanzania [

60,

61] is an arbovirus disease, which first invaded India in 1963 when a major epidemic of chikungunya fever was reported in Kolkata (West Bengal), soon followed by a wave of epidemics concurrently in 1965 in Pondicherry, Chennai (Tamil Nadu), Rajahmundry, Vishakapatnam, Kakinada (Andhra Pradesh), Sagar (Madhya Pradesh) and Nagpur (Maharashtra) and lastly in 1973 in Barsi (Maharashtra ), although thereafter, too, sporadic cases continued to be recorded especially in Maharashtra state during 1983 and 2000 [

62,

63].

After keeping quiescent for more than three decades, CHIKV re-emerged as a massive epidemic in India in 2005. Currently, just like dengue, chikungunya is also reported from every part of the country resulting in huge losses of economy and productivity. CHIKV evolution evidenced by quick mutations to form new and more viremic strains has been a significant driver for epidemics in India. Early diagnosis and disease management are keys to successful disease curtailment [

64].

Chikungunya is transmitted principally by

Aedes aegypti whereas

Aedes albopictus plays a key role in places where

Ae. aegypti is absent or in low density. Chikungunya re-emerged in an epidemic form in 2005-06 in India after 32 years. For the year 2006, the reported number of clinically suspected chikungunya fever cases was 1.39 million, whereafter keeping a low ebb in the following years. At present, chikungunya is endemic in 34 States/UTs.

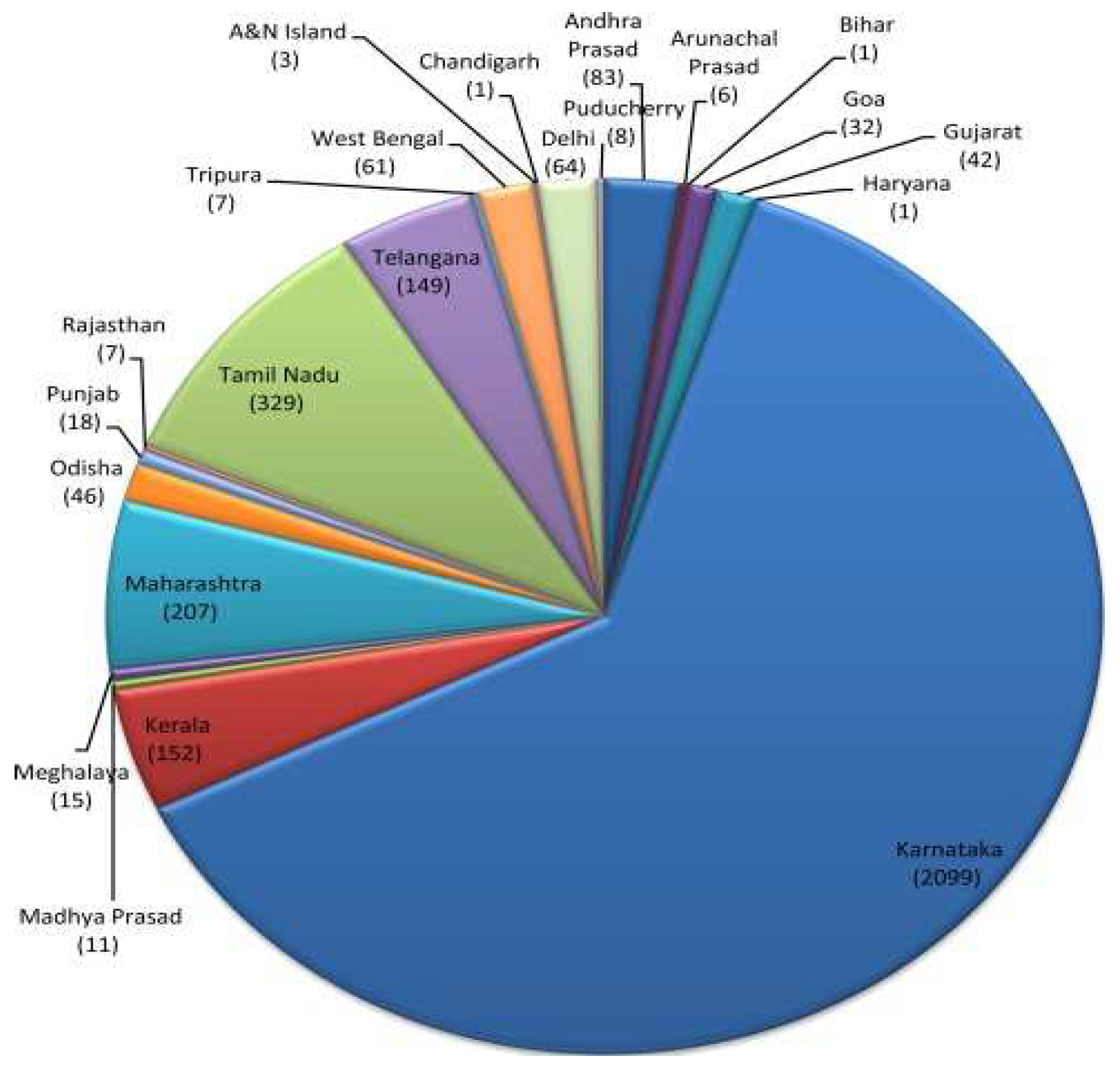

Figure 5 offers chikungunya disease burden in the country for the year 2015 [

65].

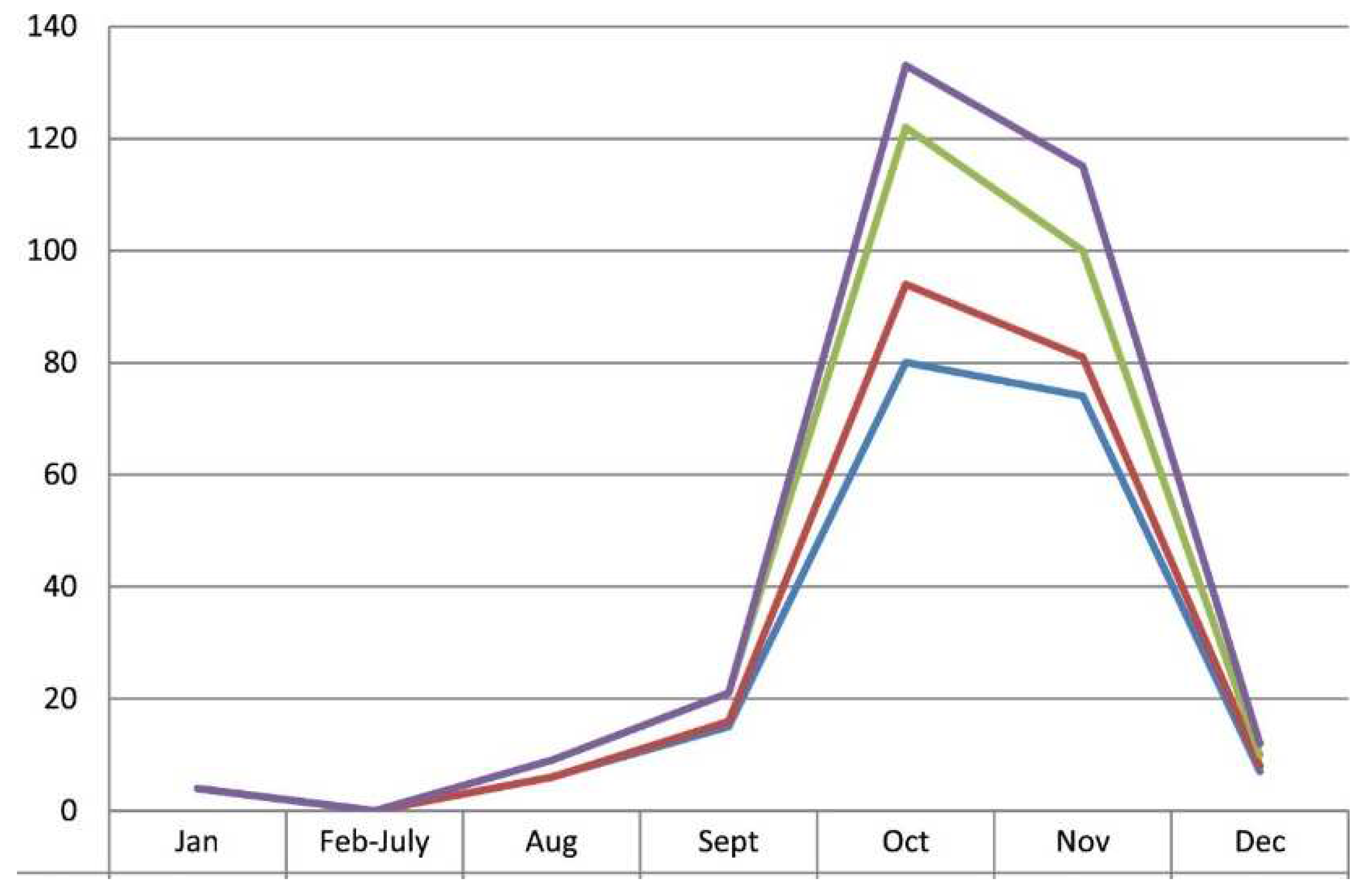

Like dengue, chikungunya is also very much seasonal, reporting maximum cases during rainy months of October-November, albeit stray cases throughout the year

Figure 6 [

65]. The seasonality months during rainy season may vary from region to region in India.

Aedes aegypti and Ae.

albopictus are the dominant vectors of chikungunya in India as well as universally. Starting with urban outbreaks, chikungunya virus transmission has invaded rural environments, too in the country [

18,

23,

66,

67].

Aedes albopictus has posed serious threats of chikungunya transmission in certain geographical regions such as Kerala and other southern states [

68,

69].

8.4. Lymphatic Filariasis (LF)

After malaria, it is the second most significant vector-borne illness in India [

70], accounting for over 40% of the world’s disease burden [

71].

Culex quinquefasciatus is responsible for the transmission of the nematode parasite

Wuchereria bancrofti, which accounts for 95% of all cases of lymphatic filariasis in India. There are three separate phases of LF clinically: (i) Asymptomatic microfilaraemia; (ii) Adenolymphangitis (ADL), an acute phase; and (iii) the chronic condition, which includes hydrocele in men and swelling of the lower and upper limbs in people of any gender [

72].

Nonetheless, this illness is widespread in both rural and urban areas, and despite the disease’s lifetime morbidity, there are few antifilarial treatments available. However, India’s history with LF is long, dating back to the sixth century BC [

73]. An important milestone in the fight against disease was the establishment of the National Filaria Control Programme (NFCP) in 1995 [

74]. But in 2000, the World Health Organization adopted the Global Programme to Eliminate LF (GPELF), which marked a paradigm shift.

Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) was administered as part of an annual mass drug administration (MDA) plan with the aim of breaking the chain of transmission. The National Program to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (NLEP) in India later implemented yearly MDA with DEC in 2004. This was followed by a two-drug regimen combining DEC and albendazole. By 2017, this program has successfully eradicated LF from previously endemic districts. However, new issues such as medication non-compliance, logistical difficulties, and a high rate of persistent transmission still exist.

Therefore, India implemented a triple drug regimen the year, adding ivermectin to the other two ongoing medications that provide more extensive antifilarial actions [

75]. Currently, India must contend with a new threat-the climate change in the fight against lymphatic filariasis (LF) transmission in India, even though great efforts have been made to eradicate the illness [

76].

9. Government initiatives

There are multiple disease-specific programmes that are directed, managed and executed via single vehicle using dedicated health workers (referred as vertical, stand-alone, categorical, or free-standing) whereas other programmes as integrated (also identified as horizontal) aim to tackle the complete health problems on a wider front and on a longer-term basis through the creation of permanent multifunctional healthcare delivery institutions. Globally several disease control programmes like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFTAM), Roll Back Malaria (RBM) and Expanded Programme of Immunization (EPI) are vertical programmes focused on malaria and other preventable diseases respectively [

77].

In 1947, at India’s independence, 22% of the country’s population was estimated to suffer from malaria with 75 million cases and 0.8 million deaths due to malaria annually. To combat devastating effects of malaria, the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) was launched in 1953 built around three key activities – insecticidal residual spray (IRS) with DDT; monitoring and surveillance of cases; and treatment of patients. Malaria related morbidity and mortality in India were rapidly brought down within a few years. Encouraged by the programme’s success, it was converted to National Malaria Eradication Programme (NMEP) in 1958. Following a massive resurgence of malaria in 1976, the Modified Plan of Operations (MPO) was launched in 1977 with a three-pronged strategy: early diagnosis and prompt treatment, vector control and IEC/BCC with community participation. To combat malaria in high transmission areas of the country, an Enhanced Malaria Control Project (EMCP) was launched with additional support from the World Bank in 1997 and Intensified Malaria Control Project (IMCP) with support of the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM) in 2005.

The malaria control programme and other vector-borne diseases control programmes, namely, kala-azar, dengue, lymphatic filariasis, Japanese encephalitis and chikungunya were integrated under the umbrella programme for prevention and control of vector-borne diseases. The programme was named as National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP) and launched in December 2003. Since 2005, NVBDCP has been implemented under the overarching umbrella of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) which has now been subsumed under the National Health Mission (NHM), incorporating the National Urban Health Mission (NUHM) as well. The Government of India also has 18 Regional Offices for Health and Family Welfare (ROHFW), located in 18 states covering one or more states under their jurisdiction. These ROHFWs play a critical role in monitoring of NVBDCP activities in the respective States. Every State has a Vector-Borne Diseases Control Unit under its State Department of Health and Family Welfare, headed by the State Programme Officer. Each State has a State Health Society and District Health Societies at the State and District levels through which funds are disbursed. At the district level, the vector-borne diseases programme including malaria is managed by the District Vector Borne Disease Control Officer (DVBDCO).

10. Discussion

Environment, particularly the climatic variability, plays an inevitably indispensable role in regulating the dynamics of several vector borne diseases [

78]. Most vector-borne diseases exhibit a distinct seasonal pattern, which clearly suggests that they are weather sensitive. The significance of environment in shaping the biology of these diseases can be amply gauged from the fact that the entire gamut of development, behaviour and survival of arthropod vectors as well as the intensity of the diseases they transmit, is strongly influenced by climatic factors.

Climate and environment are of course, not the only factors that influence the outbreak and spread of diseases; social and economic factors also are important. Surveillance programs and testing and control measures - such as monitoring for dead birds and eliminating mosquito breeding areas - can make a difference. However, it is certain that climate change provides opportunities for diseases, particularly the mosquito-borne ones and those of water-borne nature, to extend their range. Human activities and be-haviour, such as housing conditions, are also crucial to determining whether transmission to humans will occur. The location of homes in relation to the breeding sites, the structure of buildings, the material used to build them, and the daily patterns of human behaviour, such as the social life, work, rest and recreation, can all be important.

Even though there is no panacea available to completely revert the consequences of the climatic variability such as the onset of vector-borne diseases like malaria, dengue, Japanese encephalitis and filariasis, all of which prevail in India, nevertheless a complete scientific understanding of weather events and development of appropriate early warning tools may certainly still do a good help and save several lives. However, the use of climate forecast information in public health arena not only requires greater scientific understanding of climate-health symptoms, but also a paradigmatic shift in thinking from response to preparedness and mitigation. Therefore, to offer useful insight into causality and ultimately to integrate climate tools into public health policy and decision making, research must be strongly interdisciplinary amongst at least, so to say, climatology, disease epidemiology, medical entomology, sociology, and geography, but not to forget in the least the administration and political support for the cause in reference. On any level, be it regional (like that of the Thar Desert), national or international, a concerted research effort involving various agencies, organizations and the private sectors is a must.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, B.T. and M.S.; methodology, B.T. and A.A.; resources, B.T., A.A, S.S.; data curation, A.A., K.C. and B.T.; writing—original draft preparation, B.T.; writing—review and editing, A.A.; K.C.; B.T.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would also like to thank our Reckitt’s colleagues, Abhinandan, Shanthakumar S.P. and COP28 Reckitt team members for their support throughout the process of development of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- World health statistics. Monitoring Health for the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). World Health Organization: Geneva, 2022; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Sinka, M.E.; Bangs, M.J.; Manguin, S.; Rubio-Palis, Y.; Chareonviriyaphap, T.; Coetzee, M.; Mbogo, C.M.; Hemingway, J.; Patil, A.P.; Temperley, W.H.; et. al. A global map of dominant malaria vectors. Parasit. Vectors. 2012, 5, 69. [CrossRef]

- Colon-Gonzalez, F. J.; Sewe, M. O.; Tompkins, A. M.; Sjodin, H.; Casallas, A.; Rocklov, J.; Lowe, R. Projecting the risk of mosquito-borne diseases in a warmer and more populated world: a multi-model, multi-scenario intercomparison modelling study. Lancet Planet Health. 2021, 5, e404-e414. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, B.K. Control of malaria vectors of India. Indian Rev. Life Sci. 1992, 12, 211-238.

- Tyagi, B.K. Distribution of arthropod vector-borne communicable diseases and control of their vectors in India. Indian Rev. Life Sci. 1994, 14, 223-243.

- Tyagi, B.K. Desert malaria: An emerging malaria paradigm and its global impact on disease elimination. Springer-Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 416.

- WMO consolidated data shows. https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/2021-one- of-seven-warmest-years-record-wmo-consolidated-data-shows (accessed on April 18, 2022).

- Romanello, M.; Claudia Di, N.; Paul, D.; Carole, G.; Harry, K.; Pete Lampard et al. The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. The Lancet. 2022, 400, 1619-1654. [CrossRef]

- Dogra, N.; Srivastava, S. Climate Change and Disease Dynamics in India. The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI): New Delhi, India, 2012; pp. 437.

- Tyagi, B.K. Malaria in the Thar Desert. ICMR Bulletin, ICMR: New Delhi, India, 1995; 25, pp. 85-91.

- Tyagi, B.K. Dracunculiasis eradication in India, with special reference to the Thar Desert (Rajasthan). In: Helminthology in India, Editor M.L. Sood, International Books Distributors: Dehradun, India, 2001; pp. 543-555.

- Dhiman, R.C.; Pahwa, S.; Dhillon, G.P.; Dash, A.P. Climate change and threat of vector-borne diseases in India: are we prepared? Parasitol Res. 2010, 106, 763-773. [CrossRef]

- Martens, W. J.; Niessen, L. W.; Rotmans, J.; Jetten, T. H.; McMichael, A. J. Potential impact of global climate change on malaria risk. Environ health perspect. 1995, 103, 458-464. [CrossRef]

- Reiter, P. Climate change and mosquito-borne disease. Environ health perspect. 2001, 109, 141-161. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, Z. Dynamic analysis of a stochastic vector-borne model with direct transmission and media coverage. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 9128-9151. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, B.K.; Munirathinam, A.; Venkatesh, A. A catalogue of Indian mosquitoes. International Jnt. J. Mosq. Res.. 2015, 2, 50-97.

- Tyagi, B.K. Future Implications of Desert Malaria in Global Elimination Campaign. In Desert Malaria: An Emerging Malaria Paradigm and Its Global Impact on Disease Elimination, Springer: 2023; 365-372.

- Tyagi, B.K. Vector-Borne Diseases: Epidemiology and Control, 1st ed.; Scientific Publishers: 2008; pp. 298.

- NCVBDC. Annual Malaria Report. 2023. Available at: https://ncvbdc.mohfw.gov.in/WriteReadData/l892s/27392814281649745736.pdf.

- https://www.business-standard.com/india-news/tipping-point-climate-disasters-have-cost-india-over-120-bn-since-2000-124042501124_1.html.

- Dubos, R. The Wooing of the Earth (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1980); David Harvey, “The Nature of Environment”. The Socialist Register 1993, 1980; pp. 26.

- Tyagi, B.K. Medical Entomology: A handbook of medically important insects and other arthropods, Scientific Publishers: India, 2003; pp. 262.

- Tyagi, B.K.; Hiriyan, J. 2004. Breeding of dengue vector Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus) in rural Thar Desert, north-western Rajathan, India. Dengue Bulletin, WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia: 2004; 28, 220-222.

- Githeko, A.K.; Lindsay, S.W.; Confalonieri, U.E.; Patz, J.A. Climate change and vector-borne diseases: a regional analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, World Health Organization: 2000; 78, pp. 1136-1147.

- McMichael, A.J.; Kovats, R.S. Climate change and climate variability: Adaptations to reduce adverse health impacts. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2000, 61, 49-64. [CrossRef]

- Brady, O.J.; Gething, P.W.; Bhatt, S.; Messina, J.P.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hoen, A.G.; Moyes, C.L.; Farlow, A.W.; Scott, T.W.; Hay, S.I. Refining the Global Spatial Limits of Dengue Virus Transmission by Evidence-Based Consensus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.. 2012, 6, e1760. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of working group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Houghton, J.T., Y. Ding, D.J. Griggs, M. Noguer, P.J. van der Linden, X. Dai, K. Maskell, and C.A. Johnson (eds.). Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 881.

- Ryan, S.J.; Carlson, C.J.; Mordecai, E.A.; Johnson, L.R. Global expansion and redistribution of Aedes-borne virus transmission risk with climate change. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.. 2019, 13, e0007213. [CrossRef]

- Karuppusamy, B.; Sarma, D.K.; Lalmalsawma, P.; Pautu, L.; Karmodiya, K.; Nina, P.B. Effect of climate change and deforestation on vector borne diseases in the North-Eastern Indian state of Mizoram bordering Myanmar. JCCH. 2021, 2, 100015. [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Singh, A.K.; Khan, D.N.; Pandey, M.; Kumar, R.; Garg, R.; Jain, A. Trend of Japanese encephalitis in Uttar Pradesh, India from 2011 to 2013. Epidemiol. Infect.. 2016, 144, 363-370. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Gangare, V.; Singh, P.; Dhiman, R. C. Shift in potential malaria transmission areas in India, using the fuzzy-based climate suitability malaria transmission (FCSMT) model under changing climatic conditions. IJERPH. 2019, 16, 3474. [CrossRef]

- Subbarao, S.K.; Nanda, N.; Rahi, M.; Raghavendra, K. Biology and bionomics of malaria vectors in India: existing information and what more needs to be known for strategizing elimination of malaria. Malar. J.. 2019, 18, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Nanda, N.; Yadav, R.S.; Sarala K.; Subbarao, H.J.; Sharma, V.P. Studies on Anopheles fluviatilis and Anopheles culicifacies sibling species in relation to malaria in forested hilly and deforested riverine ecosystems in northern Orissa, India. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2000, 16, 199-205. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11081646/.

- Ramasamy, R.; Jude, P.J.; Veluppillai, T.; Eswaramohan, T.; Surendran, S.N. Biological differences between brackish and fresh water-derived Aedes aegypti from two locations in the Jaffna Peninsula of Sri Lanka and the implications for arboviral disease transmission. PLOS One. 2014, 9, e104977. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, T.J. Physiology of osmoregulation in mosquitoes. Annu. Rev. of Entomol.. 1987, 32, 439-462. [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, R.; Surendran, S.N.; Jude, P.J.; Dharshini, S.; Vinobaba, M. Larval development of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in peri-urban brackish water and its implications for transmission of arboviral diseases. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.. 2011, 5, e1369. [CrossRef]

- Rocklov, J.; Dubrow, R. Climate change: An enduring challenge for vector-borne disease prevention and control. Nat. Immunol.. 2020, 21, 479-483. [CrossRef]

- Fouque, F.; Reeder, J.C. Impact of past and on-going changes on climate and weather on vector-borne diseases transmission: A look at the evidence. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2019, 8, 51. [CrossRef]

- Brady, O.J.; Smith, D.L.; Scott, T.W.; Hay, S.I. Dengue disease outbreak definitions are implicitly variable. Epidemics. 2015, 11, 92-102. [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, L.; Scott, T.W.; Gubler, D.J. Consequences of the expanding global distribution of Aedes albopictus for dengue virus transmission. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.. 2010, 4, e646. [CrossRef]

- Chathuranga, W.G.D.; Weeraratne, T.C.; Abeysundara, S.P.; Karunaratne, S.H.P.P.; de Silva, W.A.P.P. Breeding site selection and co-existing patterns of tropical mosquitoes. Med Vet Entomol. 2023, 37, 550-561. [CrossRef]

- Bouma, M.J.; Van der Kaay, H.J. Epidemic malaria in India and the El Nino Southern Oscillation. Lancet. 1994, 344, 1638-1639. [CrossRef]

- Bouma, M.J.; Van Der Kaay, H.J. Epidemic malaria in India’s Thar Desert. Lancet. 1995, 373, 132-133. [CrossRef]

- Bouma, M.J.; van der Kaay, H.J. The El Nino Southern Oscillation and the historic malaria epidemics in the Indian subcontinent and Sri Lanka: An early warning system for future epidemics. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 1996, 1, 86-96. [CrossRef]

- Bouma, M.J.; Poveda, G.; Rojas, W.; Chavasse, D.; Quinones, M.; Cox, J.; Patz, J. Predicting high-risk years for malaria in Colombia using parameters of El Nino Southern Oscillation. TM & IH. 1997, 2, 1122-1127. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, B.K. Vector-Borne Diseases of the Thar Desert. Abstract Paper. Man in Desert-Medical Problems, CME-99: Jodhpur, Military Hospital, 1999; pp. 3.

- Hales, S.; de Wet, N.; Maindonald, J.; Woodward, A. Potential effect of population and climate changes on global distribution of dengue fever: An empirical model. The Lancet. 2002, 360, 830-834. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, B.K. Malaria in the Thar Desert: Facts, figures and future, Agrobios: Jodhpur, India, 2002; pp. 165.

- Mutheneni, S.R.; Morse, A.P.; Caminade, C.; Upadhyayula, S.M. Dengue burden in India: Recent trends and importance of climatic parameters, Emerg. Emerging microbes and infections. 2017, 6, e70. [CrossRef]

- World health statistics. Monitoring Health for the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). World Health Organization, Geneva, 2022; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- NCVBDC. Annual Malaria Report. 2023. Available at: https://ncvbdc.mohfw.gov.in/WriteReadData/l892s/27392814281649745736.pdf, (2021).

- Tyagi, B.K.; Chaudhary, R.C. Outbreak of falciparum malaria in the Thar Desert (India), with particular emphasis on physiographic changes brought about by extensive canalization and their impact on vector density and dissemination. J. Arid Environ.. 1997, 36, 541-555. https://colab.ws/articles/10.1006%2Fjare.1996.0188#.

- Hiriyan, J.; Tyagi, B.K. Cocoa pod (Theobroma cacao)-A potential breeding habitat of Aedes albopictus in dengue sensitive Kerala state, India. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc.. 2004, 20, 323-325. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15532938/.

- Baruah, K.; Arora, N.; Sharma, H.; Katewa, A. Dengue in India: Temporal and spatial expansion in last two decades. JOMAPH. 2021, 1, 15-32.

- Tyagi, B.K. The invincible deadly mosquitoes: India’s Health and Economy Enemy No. 1, Scientific Publishers: India, 2004; pp. 266.

- Tyagi, B.K. Dengue and climate change: Kerala-An eye opener. Central Entomology Laboratory, Madurai, 8th International Symposium on Vectors & Vector Borne Diseases (Central Theme: Tropical Diseases and Health), Madurai, 2006; pp. 160.

- Tyagi, B.K.; Hiriyan, J. Breeding of dengue vector Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus) in rural Thar Desert, north-western Rajasthan, India. Dengue Bulletin, 2006; 28, pp. 220-222.

- Sumodan, P.K. Potential of rubber plantations as breeding source for Aedes albopictus in Kerala, India. Dengue Bulletin, 2003; 27, pp. 197-198.

- Sumodan, P.K. Unconventional breeding habitats of Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse) related to agriculture crops in Kerala, India: A review. Int. J. Mosq. Res.. 2019, 6, 113-115.

- Lumsden, W.H. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952-53. II. General description and epidemiology. TRSTMH. 1955, 49, 33-57. [CrossRef]

- Weinbren, M.P.; Haddow, A.J.; Williams, M.C. The occurrence of Chikungunya virus in Uganda. I. Isolation from mosquitoes. TRSTMH. 1958, 52, 253-257. [CrossRef]

- Sudeep, A.B.; Parashar, D. Chikungunya: an overview. J. Biosci. 2008, 33, 443-449. [CrossRef]

- Translational Research Consortia (TRC) for Chikungunya Virus in India. Current status of chikungunya in India. Front. Microbiol.. 2021, 12, 695173. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet. 2012, 380, 219-229. [CrossRef]

- Dinkar, A.; Singh, J.; Prakash, P.; Das, A.; Nath, G. Hidden burden of chikungunya in North India. A prospective study in a tertiary care center. J. Infect. Public Health. 2018, 1, 586-591. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, B.K. Emergence of dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever in Kerala state (South India), impact of climate change on Aedes albopictus Skuse as the sole vector. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2007a, 12, 127.

- Tyagi, B.K. Chikungunya in India. Bulletin de la Societe de Pathologie Exotique, 2007b; 100, pp. 321.

- Kaur, P.; Ponniah, M.; Murhekar, M.V.; Ramachandran, V.; Ramachandran, R.; Raju, H.K.; Perumal, V.; Mishra, A.C.; Gupte, M.D. Chikungunya outbreak, South India, 2006. Emerg. Infect. Dis.. 2008, 14, 1623-1625. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.P.; Abidha, S.; Perumal, V.; Shanmugavelu, S.; Kalianna, G.K.; Jacob, M.; Varakilparambil, T.J.; Purushothaman, J. Chikungunya virus outbreak in Kerala, India. A seroprevalence study. MIOC. 2011, 106, 912-916. [CrossRef]

- Ramaiah, K.D.; Das, P.K.; Michael, E.; Guyatt, H.L. The economic burden of lymphatic filariasis in India. Parasitol. today. 2000, 16, 251-253. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, B.K. Lymphatic filariasis: epidemiology, treatment and prevention-the Indian perspective, Springer: 2018; pp. 314.

- Ramaiah, K.D.; Kumar, K.V.; Ramu, K. Knowledge and beliefs about transmission, prevention and control of lymphatic filariasis in rural areas of South India. TM & IH. 1996, 1, 433-438. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P. Lymphatic Filariasis in India: A Journey towards Elimination. JOCD. 2020, 52, 17-21. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7696-3845.

- Babu, S.; Nutman, T.B. Immunopathogenesis of lymphatic filarial disease. In Seminars in immunopathology, Springer-Verlag: Germany, 2012; 34, pp. 847-861.

- Weil, G.J.; Jacobson, J.A.; King, J.D. A triple-drug treatment regimen to accelerate elimination of lymphatic filariasis: From conception to delivery. Int. Health. 2021, 13, S60-S64. [CrossRef]

- Roswati, S.; Ahmad, S.; Eke, M.; Ramadhan, T. A Systematic literature (Impact of Climate Change on Filariasis). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci.. 2021, 755, 012083. [CrossRef]

- https://www.who.int/management/district/services/WhenDoVerticalProgrammesPlaceHealthSystems.pdf.

- Gubler, D.J.; Reiter, P.; Ebi, K.L.; Yap, W.; Nasci, R.; Patz, J.A. Climate variability and change in the United States: Potential impacts on vector- and rodent-borne diseases. Environ. health perspect.. 2001, 109, 223-233. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).