1. Introduction

Visual information contains multiple features, such as colors, shapes, and directions. Visual attention can bind multiple features into a unified object during perception, which is referred to as the binding process (Treisman and Gelade 1980, Treisman 1998).Binding representations can store in visual working memory (VWM) (Luck and Vogel 1997, Wheeler and Treisman 2002), a limited-capacity system for temporarily storing and processing visual information (Baddeley 2012, Baddeley et al. 2021). However, the mechanisms of the role of visual attention in holding bindings in VWM has not been determined.

The dual-task paradigm is commonly used to study the attentional demand in VWM (Allen et al. 2006). This paradigm introduces a secondary task that competes for visual attention in the VWM maintenance stage. Studies have examined whether holding bindings in VWM is more affected by a secondary task than holding features (Hollingworth and Maxcey-Richard 2013, Johnson et al. 2008, Shen et al. 2015). Visual attention is classified as space-based attention and object-based attention. Space-based attention refers to the system by which perceptual processing resources are devoted to a specific location and enhances the processing of all features at a specific location of the visual field (Hollingworth and Maxcey-Richard 2013), while object-based attention enhances the features at the locations that define the selected object, and can be allocated rapidly throughout the object (Cavanagh et al. 2023, Itti and Koch 2001).

A series of studies were found that spatial-based attention plays no special role in maintaining bindings in VWM, whereas object-based attention plays a crucial role in such process (Gao et al. 2017, Hollingworth and Maxcey-Richard 2013, Johnson et al. 2008, Shen et al. 2015). For instance, when a secondary task that competed the object-based attention was inserted in the VWM maintenance stage, bindings were selectively more impaired by the secondary task than features, which indicated that retaining bindings requires more object-based attention than retaining features (Shen et al. 2015). Furthermore, this role of object-based attention is robust across binding types, VWM activation states, and number of features within the bindings, suggesting that object-based attention underline a broad range of binding forms, and bound more features does not require extra object-based attention (Gao et al. 2017, He et al. 2020, Lu et al. 2019, Zhou et al. 2021). Researchers proposed that the reentrant process may be the underlying mechanism by which binding representing in VWM requires more object-based attention than features.

Furthermore, the property of binding representations modulates the degree of object-based attention requirement for bindings. In contrast to bindings of dissimilar features, holding bindings composed of similar features do not require increased object-based attention than features (Che et al. 2019). Moreover, compared to the separate bindings (e.g., color-shape bindings), the integral bindings, characterized by tightly bound perceptual characteristics that cannot be processed independently (e.g., width and height of an object), do not require more object-based attention than features (Wan et al. 2020). The reason may be that the stability of the binding representation modulates the degree of involvement of object-based attention.

The visualizer cognitive style, a typical cognitive style, characterizes two contrasting imagery abilities individuals use to acquire and process visual information (Kozhevnikov et al. 2005). Using the Object–Spatial Imagery Questionnaire (OSIQ), researchers distinct two type of visualizers: object visualizers (OVs) and spatial visualizers (SVs) (Blajenkova et al. 2006). OVs have advantages in processing images holistically, integrate them as a single perceptual unit, leading them excel in constructing pictorial objects and outperform SVs in tasks requiring the generation of high-resolution images (e.g., recognizing degraded objects). In contrast, SVs have advantages in processing images analytically, part by part, using spatial relations to arrange and analyze the components. SVs outperform OVs in representing dynamic spatial relations and transformations (e.g., mental rotation) (Kozhevnikov et al. 2005, Kozhevnikov et al. 2010). Such differences unlike strategies, is a trade-off between object and spatial visualization abilities within a limited capacity in visual attention (Kozhevnikov et al. 2010). A functional magnetic resonance imaging study showed greater neural efficiency for OVs than SVs during object imagery task (Motes et al. 2008). Moreover, due to this neural efficiency OVs are demonstrated superior performance in object VWM (Li et al. 2011).

Given that bindings in VWM are a form of object maintenance, OVs might outperform SVs in holding muti-feature bindings VWM, and OVs should invest more object-based attention than SVs. Although previous research has ascribed object-based attention a crucial role in holding bindings, the exact mechanism of how object-based attention works is not known. In the present study, we addressed this gap in knowledge by examining the role of visualizer cognitive style therein.

In Experiment 1, we investigated whether OVs outperform SVs in holding bindings in VWM. The modified delayed matching task with a long or short delay interval was used. The hypothesis is that OVs and SVs perform comparable under the short delay condition, while OVs perform better than SVs under the long delay condition. In Experiment 2, we adopted a dual-task paradigm to investigate whether visualizer cognitive style modulates the requirement of object-based attention in retaining features and bindings. The hypothesis is that compared to SVs, OVs who excel in binding maintenance within VWM would exhibit larger impairment in binding retention when object-based attention is consumed by a secondary task. In Experiment 3, we used the event-relate potential(ERP) technique to investigate how the visualizer cognitive style modulates object-based attention while holding bindings and performing the secondary task in VWM. P2 and late positive component (LPC) were used as ERP indictor during VWM encoding and the secondary task performing, respectively. P2 reflects the recruitment of attentional resources in VWM encoding (Smith 1993, Wolach and Pratt 2001).The hypothesis is that OVs would elicit lower P2 during VWM encoding under the task-present condition than the task-absent condition, compared to SVs. LPC has been linked to the effort requirement in VWM maintenance (Gunseli et al. 2014a, Gunseli et al. 2014b). The hypothesis is that OVs, would invest more effort in holding bindings when the secondary task competes object-based attention, resulting in larger LPC amplitude, compared to SVs.

2. Experiment 1: Holding bindings in VWM for object and spatial visualizers

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Revised Version of Object-Spatial Image Questionnaire

We employed the Chinese revised version of the Object-Spatial Imagery Questionnaire (OSIQ-R) by Li et al. (2011) to classify the participants as either OVs or SVs. It consists of 15 items in the object imagery scale (e.g., “When I read a novel, I can usually form a detailed and vivid image of the scene based on the description”) and 15 items in the spatial imagery scale (e.g., “I can easily imagine and mentally rotate 3-dimensional geometric figures”). Participants were instructed to rate each statement on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (total disagreement) to 5 (total agreement). Object and spatial imagery scores were computed separately by summing the ratings of the 15 items for each scale. For the present study, the Cronbach's α coefficients for the object and spatial scales were 0.78 and 0.73, indicating acceptable reliability.

2.1.2. Participants

A total of 1290 college students were tested with the OSIQ-R. OVs were defined as participants scoring in the top 30% on the object imagery scale and in the bottom 30% on the spatial imagery scale. Conversely, SVs were defined as participants scoring in the bottom 30% on the object imagery scale and in the top 30% on the spatial imagery scale. Based on the OSIQ-R scores, 123 students (Mobject-scores = 3.90, 95%CI [3.85, 3.96]; Mspatial-score = 2.35, 95%CI [2.30, 2.39]) were classified as OVs and 83 students (Mobject-scores = 2.86, 95%CI [2.80, 2.93]; Mspatial-score = 3.42, 95%CI [3.36, 3.48]) were classified as SVs. These participants were then included in the object or spatial visualizer pools, from which subjects for the three experiments were randomly selected.

The sample size for the current experiment was calculated using the G*Power (Version 3.1.9; Faul et al. 2007). Based on the previous study (Li et al. 2011, Shen et al. 2015), we predicted a large effect size (f = 0.40), the alpha level (α) = 0.05, and the statistical power (1 - β) = 0.80, leading to the minimal required sample size of 16.

Twenty OVs (13 females, 18-22 years old; Mobject-scores = 3.95, 95%CI [3.81, 4.10], Mspatial-score = 2.76, 95%CI [2.62, 2.90]) and 20 SVs (12 females, 18-20 years old; Mobject-scores = 2.40, 95%CI [2.31, 2.49]; Mspatial-score = 3.30, 95%CI [3.21, 3.39]) were randomly selected from the OVs and SVs pools in this experiment. The difference in gender was not significant between the two groups (χ2 = 1.07, p = 0.744). All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and normal color vision. Each participant was naive regarding the purpose of the study. All the participants were right-handed and had no history of neurological problems. The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology at Shandong Normal University.

2.1.3. Materials and apparatus

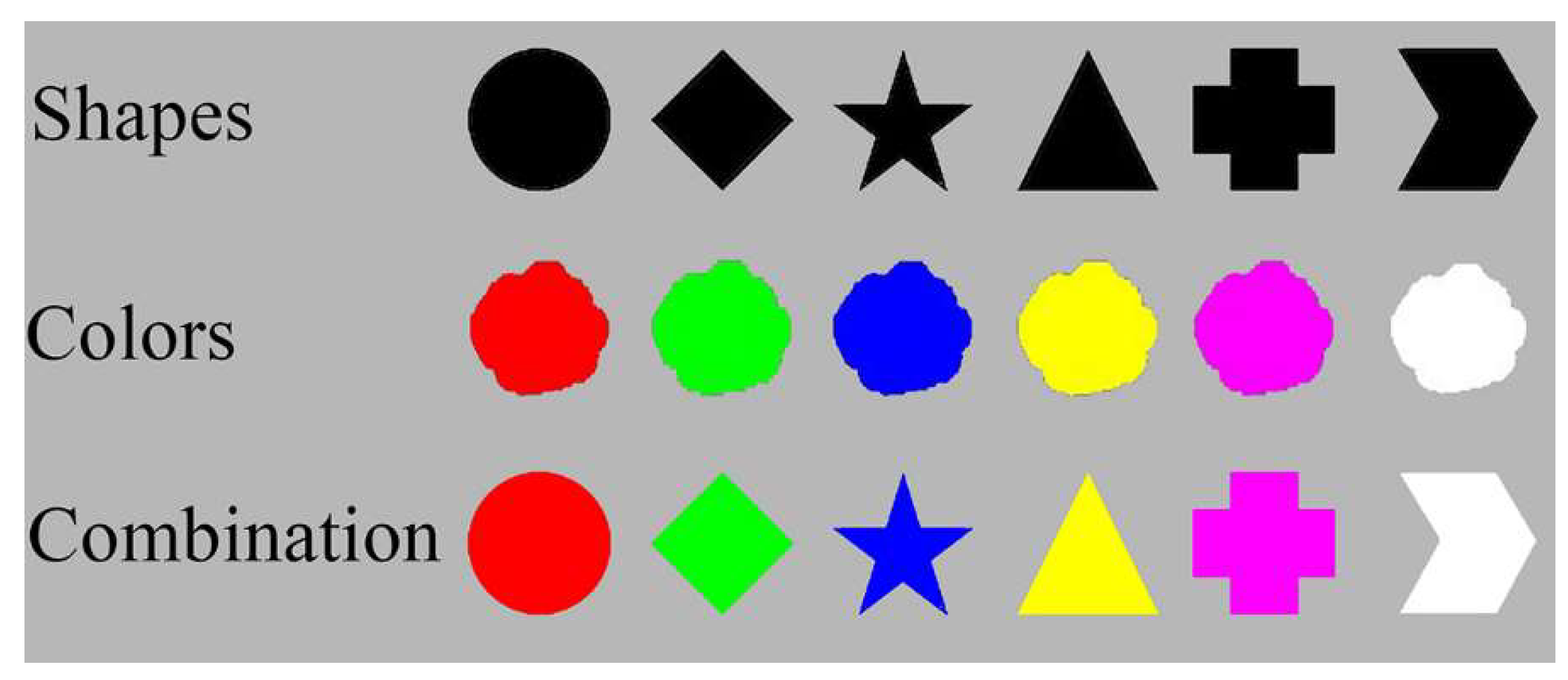

The stimuli in the present study are shown in

Figure 1. They consisted of 6 shapes (1.5°× 1.5°) and 6 colors (red: 255, 0, 0; green: 0, 255, 0; blue: 0, 0, 255; yellow: 255, 255, 0; purple: 255, 0, 255; white: 255, 255, 255). In the feature probe condition, visual shapes and color blobs were used as the stimuli. The visual shapes were filled in black (RGB: 0, 0, 0; see

Figure 1, top row). The color blobs were vague, irregular and noncanonically shaped circles (Shen et al. 2015; see

Figure 1, middle row). In the binding probe condition, the items were objects with a random combination of shapes and colors (see

Figure 1, bottom row). The memory array contained 3 items distributed horizontally in the center of the screen, with an inter-circle distance of no less than 2.5°. The probe was located 2.5° below the center of the screen.

The stimuli were displayed with E-prime 2.0 (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania, USA) in gray (RGB: 125, 125, 125) background on an LCD monitor with a resolution of 1024 × 768 pixels at a 60Hz refresh rate.

2.1.4. Design and procedure

A 2 (cognitive style: OVs vs. SVs) × 2 (delay: short vs. long) mixed experimental design was utilized, in which cognitive style served as a between-subjects factor, the delay served as a within-subjects factor. The delay is the time of interval between the disappearance of the memory array and the presentation of the test probe: the short delay condition is 1000ms, the long delay condition is 3000ms. There were two blocks: binding probe with short delay and a binding probe with long delay.

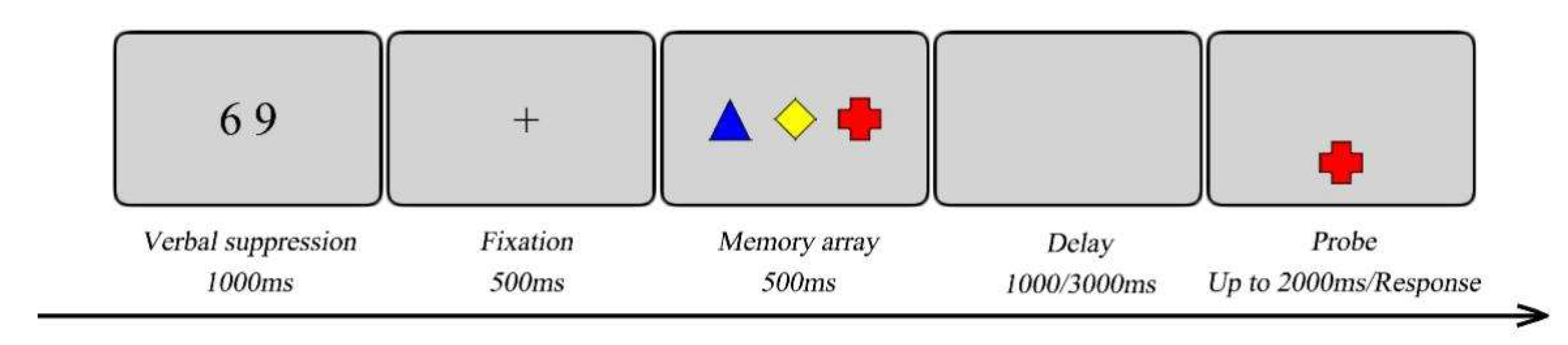

During the experiment, participants were seated in a quiet room, approximately 57cm from the screen. As shown in

Figure 2, each trial started with the presentation of two black digits for 1000ms. Participants were instructed to repeatedly articulate these two digits aloud throughout the entire trial to prevent verbal coding of the stimuli. After a 500-ms fixation on a cross in the center of the screen, the memory array was presented for 500ms. Next, a retention interval of 1000 or 3000ms (short or long delay) was presented. A probe was then presented for 2000ms in the center of the lower screen, during which the participants determined whether the color and shape combination of the probe was identical to the items presented in the memory array by pressing a response key (pressing “F” for a “yes” response or “J” for a “no” response). In 50% of the trials, the probe was one of the memory array. While in the remaining trials the probe was different from the items in the memory array, which were formed by combining two features from two randomly selected items in the memory array. Each block had 48 trials, resulting in a total of 96 trials. Participants complete 20 practice trials before each block. The order of two blocks was counterbalanced between participants. A 5 mins break was taken between blocks. The task lasted approximately 30 mins.

2.1.5. Analysis

The statistical analysis was computed with SPSS 26.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Accuracy was analyzed in using a two-way mixed, repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA).

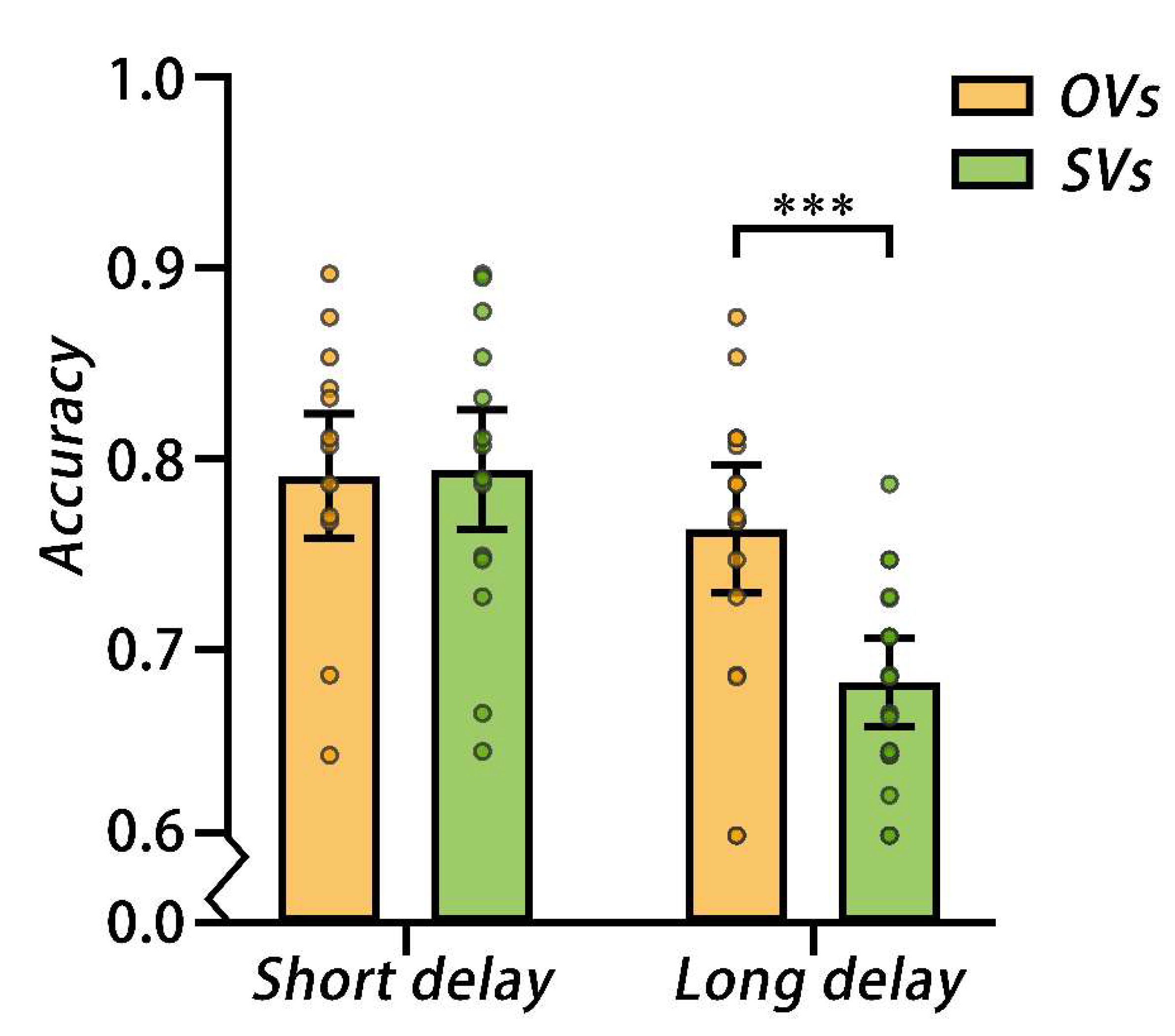

2.2. Results

A 2 cognitive style × 2 delay two-way mixed, repeated measures ANOVA on the accuracy showed that the main effect of the cognitive style was significant,

F (1, 38) = 4.94,

p = 0.032, η

p2 = 0.12). OVs (

M = 0.82, 95%CI [0.80, 0.85]) performed better than SVs (

M = 0.78, 95%CI [0.76, 0.81]). The main effect of the delay was significant,

F (1, 38) = 38.45,

p < 0.001, η

p2 = 0.50). The accuracy under the short delay condition (

M = 0.84, 95%CI [0.81, 0.86]) was better than that under the long delay condition (

M = 0.77, 95%CI [0.75, 0.79]). The interaction was significant,

F (1, 38) = 13.91,

p < 0.001, η

p2 = 0.27). A simple effect analysis showed that the accuracy for OVs was better than SVs under the long delay condition,

F (1, 38) = 16.82,

p < 0.001, η

p2 = 0.31. However, there was no significant difference in accuracy between OVs and SVs under the short delay condition,

F (1, 38) = 0.023,

p = 0.880, η

p2 = 0.001 (see

Figure 3).

2.3. Discussion

In Experiment 1, we investigated the color-shape binding VWM performances of OVs and SVs by manipulating varying the delays between the memory array and the probe. The results showed that OVs and SVs performed comparable under the short delay condition, whereas OVs performed better than SVs in holding bindings in VWM under the long delay condition. Which suggests that OVs have more advantages in long-term holding bindings VWM than SVs, consistent with our hypothesis. Studies have revealed that holding bindings in VWM requires more object-based attention than holding features (Gao et al. 2017, Shen et al. 2015, Zhou et al. 2021). Object-based attention play a crucial role in holding bindings in VWM. Does OVs invest more object-based attention in maintaining bindings in VWM than SVs? To examine this issue, we conducted Experiment 2.

3. Experiment 2: Do Object Visualizers and Spatial Visualizers Invest Different Amount of Object-Based Attention in Holding Bindings in VWM?

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

The chosen parameters of G*Power were the same as in Experiment 1, leading to the minimal required sample size of 12.

Twenty OVs (12 females, 18-20 years old; Mobject-scores = 3.88, 95%CI [3.72, 4.04], Mspatial-score = 2.29, 95%CI [2.17, 2.42]) and 20 SVs (8 females, 18-20 years old; Mobject-scores = 2.70, 95%CI [2.54, 2.86]; Mspatial-score = 3.36, 95%CI [3.23, 3.48]) were randomly selected from the OVs and SVs pools in this experiment. The difference in gender was not significant between the two groups (χ2 = 1.61, p = 0.206).

3.1.2 Materials and apparatus

The stimuli used in the memory array and probe was same as Experiment 1. The secondary task was a feature report task (Matsukura and Vecera 2009). The box-line stimuli consisted of two superimposed objects: a box (0.67° width) with a gap and a tilted line. The box was either short (0.67°) or tall (1.14°) and had a gap (0.20° width) centered either on the left or right. The line (1.53° long) was dashed or dotted and tilted 8° to the left or right. The box-line stimulus was followed by a visual mask that was 1.62° in width and 2.10° in height. There were four feature report questions related to the box or the line: (1) box height (short vs. tall), (2) box gap orientation (left vs. right), (3) line type (dashed vs. dotted), and (4) line tilting (left vs. right).

The apparatus and software were the same as those used in Experiment 1.

3.1.3. Design and procedure

A 2 (cognitive style: OVs vs. SVs) × 2 (secondary task: task-present vs. task-absent) × 2 (probe: feature vs. binding) mixed experimental design was utilized, in which cognitive style served as a between-subjects factor and the secondary task and the probe served as within-subjects factor. The secondary task is whether the participants were required to remember the box-line stimuli, and answered the following two questions. The probe is the types of stimuli that participants were required to remember and detect: for the feature probe condition, the stimuli are the colors or the shapes, which were presented separately; for the binding probe condition, the stimuli are the combination of the colors and shapes. Thus, there were 6 blocks: a color feature probe with the secondary task, a color feature probe without the secondary task, a shape feature probe with the secondary task, a shape feature probe without the secondary task, a binding probe with the secondary task, and a binding probe without the secondary task.

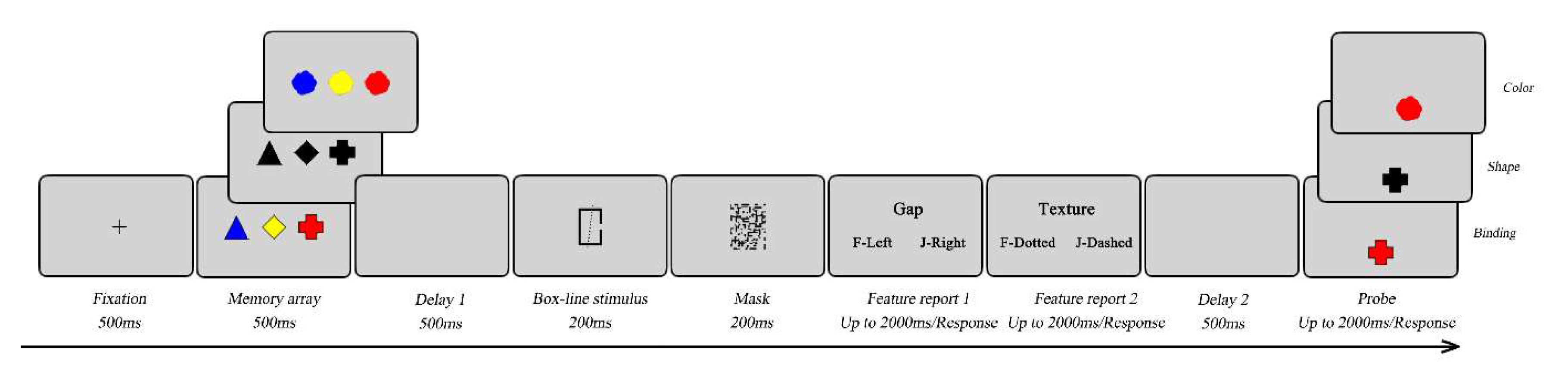

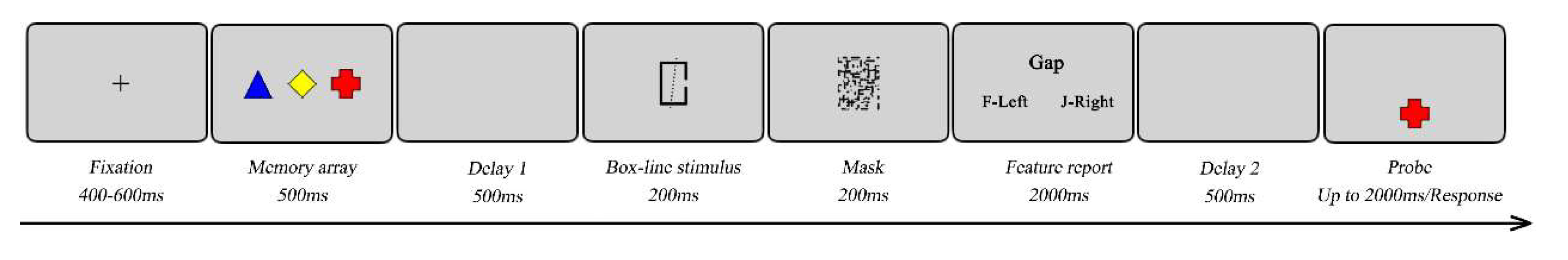

During the experiment, participants were seated in a quiet room approximately 57 cm from the screen. As shown in

Figure 4, each trial started with a fixation cross for 500ms in the center of the screen. Then, the memory array was presented for 500ms. Next, after a 500ms delay, a box-line stimulus was presented for 200ms, followed by a 200ms visual mask. Two questions were then sequentially presented. Under the task-present condition, participants were instructed to remember the box-line stimulus and report two box-line features by pressing “F” or “J” based on the presented alternatives. The first question was about the box, and the second was about the line (see above). Under the task-absent condition, participants were instructed to ignore the questions by pressing the “spacebar” on the keyboard. The feature probe screens lasted a maximum of 2000ms. Once participants made a response by pressing the corresponding key on the keyboard, the procedure immediately continued to the next step. After another 500ms delay, a probe was presented for 2000ms in the lower center of the screen. Under the feature probe condition, participants were introduced to determine whether the color or the shape was identical to the memory array by pressing a response key (pressing “F” for a “yes” response or “J” for a “no” response). In 50% of the trials, the probe was one of the memory array. While in the remaining trials, the probe was a new feature or shape that was not appeared in the memory array. Under the binding conditions, the settings were identical to those in Experiment 1.Each block contained 48 trials, resulting in a total of 288 trials. Participants complete 20 practice trials before each block. The order of six blocks was counterbalanced between participants. A 5mins break was taken between blocks. The task lasted approximately 70mins.

3.1.4. Analysis

The accuracy was analyzed in using a three-way mixed, repeated measures ANOVA. Furthermore, we calculated the difference between the task-absent and task-present condition as the cost of consuming object-based attention by the secondary task. Cost was analyzed by a planned contrasts in using the paired samples or the independent samples t-tests for interactions according to the conditions.

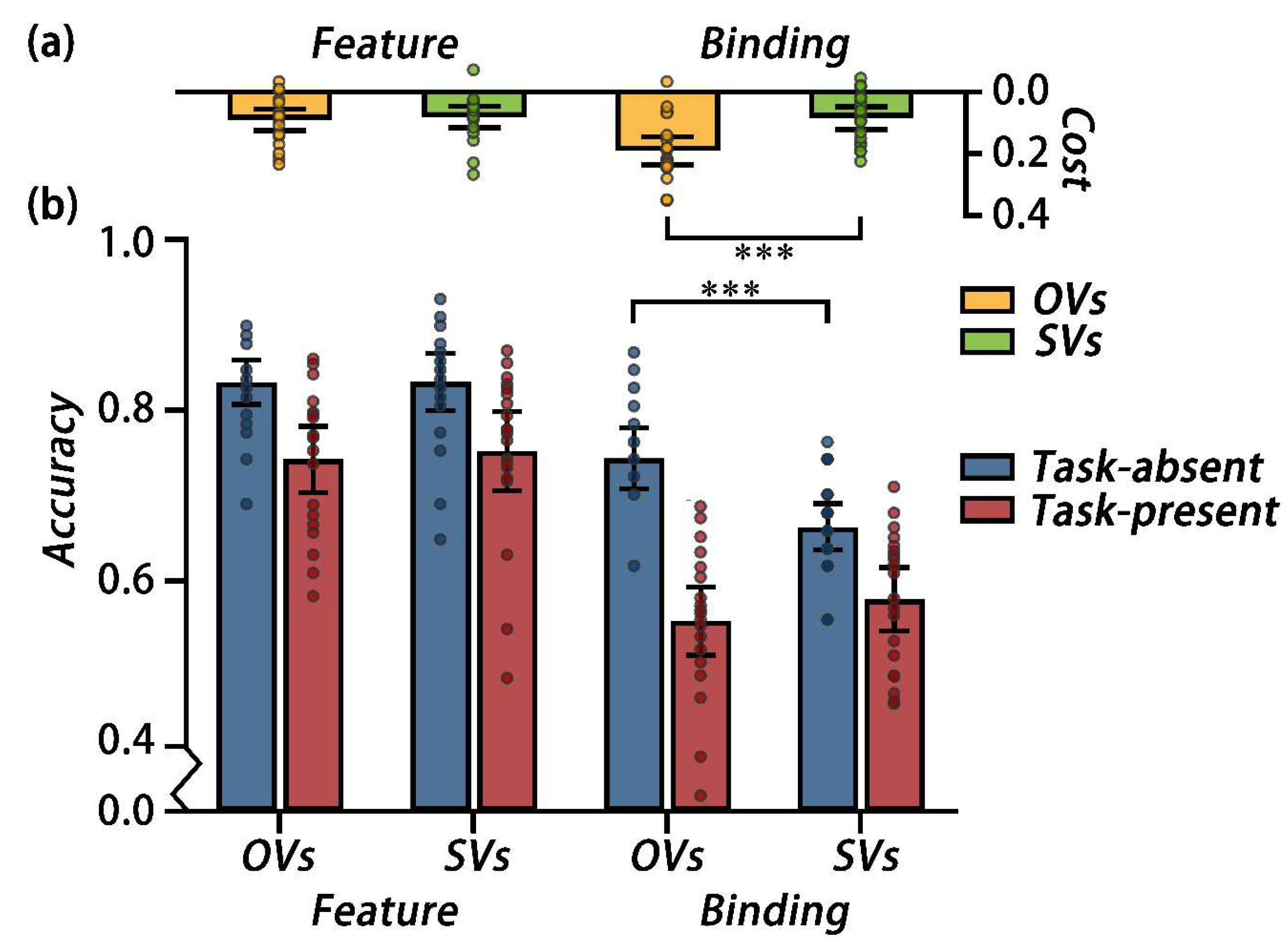

3.2. Results

The accuracy of the secondary tasks across conditions in Experiment 2 and 3 was above 80%. There was no significant effect on both probe type and cognitive styles for accuracy and reaction time (RT) of the secondary tasks (see the

Appendix A for details).

A 2 cognitive style × 2 secondary task × 2 probe three-way mixed, repeated measures ANOVA on the accuracy was conducted. The main effect of the secondary task was significant, F (1, 38) = 132.30, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.78. Participants performed better under the task-absent condition (M = 0.84, 95%CI [0.82, 0.86]) than under the task-present condition (M = 0.73, 95%CI [0.70, 0.75]). The main effect of the probe was significant, F (1, 38) = 240.85, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.86, showing that the performance under the feature probe condition (M = 0.86, 95%CI [0.84, 0.88]) was better than that under the binding probe condition (M = 0.71, 95%CI [0.69, 0.72]). The main effect of the cognitive style was not significant (MOVs = 0.79, 95%CI [0.76, 0.81] vs. MSVs = 0.78, 95%CI [0.75, 0.80]), F (1, 38) =0.38, p = 0.541, ηp2 = 0.01.

The interaction between the cognitive style and the secondary task was significant, F (1, 38) = 8.77, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.19. A simple effect analysis showed that the OVs (M = 0.86, 95%CI [0.83, 0.88]) performed better than SVs (M = 0.82, 95%CI [0.79, 0.84]) under the task-absent condition, F (1, 38) = 5.55, p = 0.024, ηp2 = 0.13; while they performed comparable under the task-present condition (MOVs = 0.72, 95%CI [0.68, 0.75] vs. MSVs = 0.74, 95%CI [0.70, 0.77]), F (1, 38) = 0.55, p = 0.462, ηp2 = 0.01. The interaction between the secondary task and the probe was significant, F (1, 38) = 9.26, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.20. A simple effect analysis showed that for feature probe condition, the accuracy under the task-absent condition(M = 0.90, 95%CI [0.88, 0.92]) is better than that under the task-present condition (M = 0.82, 95%CI [0.79, 0.85]), F (1, 38) = 52.54, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.58; for the binding probe condition, the accuracy under the task-absent condition(M = 0.82, 95%CI [0.79, 0.85]) is better than that under task-present condition (M = 0.64, 95%CI [0.61, 0.66]), F (1, 38) = 96.96, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.72. Furthermore, the costs under the different probe conditions were analyzed by a planned contrasts in using a paired samples t-tests. Result showed that the cost under the binding probe condition (M = 0.14, 95%CI [0.11, 0.17]) was larger than the feature probe condition (M = 0.09, 95%CI [0.06, 0.11]), t(39) = 2.80, p = 0.008, Cohen’s d = 0.90. The interaction effect between the cognitive style and the probe was not significant, F (1, 38) = 2.62, p = 0.114, ηp2 = 0.06.

The three-way interaction was significant,

F (1, 38) = 7.97,

p = 0.008, η

p2 = 0.17. A simple-simple effect analysis showed that under the task-absent condition, the OVs performed better than the SVs under the binding condition,

F (1, 38) = 14.08,

p < 0.001, η

p2 = 0.27, but not under the feature condition,

F (1, 38) = 0.001,

p = 0.980, η

p2 = 0.00. Under the task-present condition, the OVs and SVs performed comparable in both feature and binding probe condition,

F (1, 38) = 0.96,

p = 0.335, η

p2 = 0.03 (see

Figure 5b).

To further examine the effect of the secondary task, we conducted two independent samples

t-tests on the costs under the different probe conditions for OVs and SVs, respectively. Under the feature condition, the costs were comparable for OVs and SVs,

t(38) = 0.38,

p = 0.703, Cohen’s

d = 0.12. While under the binding condition, the cost was larger for OVs than SVs,

t(38) = 3.79,

p < 0.001, Cohen’s

d = 1.23 (see

Figure 5a).

3.3. Discussion

In Experiment 2, we investigated whether OVs and SVs invest different amount of object-based attention in holding bindings in VWM. During the maintenance of features and bindings in VWM, participants reported two questions about the box-line stimuli in the secondary task, which consumed object-based attention. A three-way interaction was found. By taking the difference between the VWM performance with and without the secondary task, we analysis the cost of consuming object-based attention. Result shows that OVs have larger cost than SVs when holding bindings, while OVs and SVs have comparable costs when holding features. Which consist with our hypothesis. What is the exact mechanism underlying how OVs and SVs modulate the object-based attention when holding bindings in VWM? In Experiment 3, we explored this issue using ERP technology.

4. Experiment 3: How Object and Spatial Visualizers Hold Bindings in VWM? Evidence from ERP

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants

The chosen parameters of G*Power were the same as in Experiment 1, leading to the minimal required sample size of 16.

Forty students were randomly selected from the remaining OVs and SVs. Five participants were excluded due to insufficient artifact-free trials of electroencephalography (EEG) recordings (n = 3) or due to malfunctioning of the EEG recorder (n = 2), leaving 18 OVs (13 females, 18-21 years old; Mobject-scores = 3.81, 95%CI [3.66, 3.96]; Mspatial-score = 2.33, 95%CI [2.19, 2.47]) and 17 SVs (8 females, 18-22 years old; Mobject-scores = 3.81, 95%CI [3.66, 3.96]; Mspatial-score = 2.33, 95%CI [2.19, 2.47]) for whom the data were analyzed. The two groups did not differ in gender (χ2 = 2.31, p = 0.129).

4.1.2. Materials and apparatus

The stimuli, apparatus and software were the same as those used in Experiment 2.

4.1.3. Design and procedure

A 2 (cognitive style: OVs vs. SVs) × 2 (secondary task: task-present vs. task-absent) mixed design was utilized, in which cognitive style served as a between-subjects factor and the secondary task served as a within-subjects factor. There were two blocks: binding probe with the secondary task-absent or -present.

Participants were seated in a quiet room approximately 57 cm from the screen. The procedure was the modified from the Experiment 2 binding probe condition (see

Figure 6), the modifications are as follows. First, the fixation varying in duration between 400ms and 600ms to avoid the anticipation effect. Second, the durations of the feature report question and the probe were fixed at 2000ms to equate the duration of each trial for the analysis. Third, to exclude the factor that SVs may have lower object VWM capacity leading to have less amount of disruption by the secondary task, the number of feature report questions in the secondary task was reduced to one, which was randomly selected from the two options (i.e., either the box or the line). The remaining settings were identical to those in the binding probe condition in Experiment 1. Each block contained 50 trials and was presented twice, resulting in a total of 200 trials. Participants complete 20 practice trials before each block. The order of six blocks was counterbalanced between participants. A 10mins break was taken between the blocks. The task lasted approximately 60mins.

4.1.4. Behavioral analysis

The accuracy was analyzed in using a two-way mixed, repeated measures ANOVA.

4.1.5. Electroencephalogram recording and analysis

Recording. EEG signals were recorded by 64-channel Ag/AgCl electrodes that were mounted in an elastic cap (NeuroScan, El Paso, Texas, USA) according to the 10–20 system, with the reference on the left mastoid and a ground electrode on the medial frontal aspect. A vertical electrooculogram (VEOG) was recorded from electrodes located 1cm below and above the left eye. The horizontal EOG (HEOG) was recorded as the left versus the right orbital rim. VEOG was used to detect blink artifacts, and HEOG was used to detect horizontal eye movement artifacts. The impedances of all electrodes were maintained at less than 5kΩ. The signals were digitized at 1000Hz.

Preprocessing. Offline analysis was conducted using the EEGLAB toolbox in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). The data were first down-sampled to 500Hz to save storage space and filtered with an IIR Butterworth filter with a 0.5–30Hz bandpass. The data were subsequently re-referenced to the 1/2 voltage value of the right mastoid and were epoched from -200ms to 3000ms around the onset of the memory array. Epochs with incorrect behavioral responses (both the VWM task and the secondary task) or with excessive noise were excluded. Epochs were baseline-normalized using the whole epoch as the baseline to improve independent component analysis (ICA; Groppe et al. 2009). Through visual inspection of the ICA results, we identified components that captured eye blinks and horizontal eye movements. These components were removed from the EEG data; on average, 2.43 ± 0.24 independent components were removed. The post-ICA epochs were baseline-corrected and underwent automatic artifact rejection based on a threshold of ±100 μV for the time range of -200–3000ms to discard epochs contaminated by residual artifacts. This led to the removal of approximately 3.35% of trials per participant. After data processing, participants with a remaining number of trials per condition lower than 40 were excluded from the analysis.

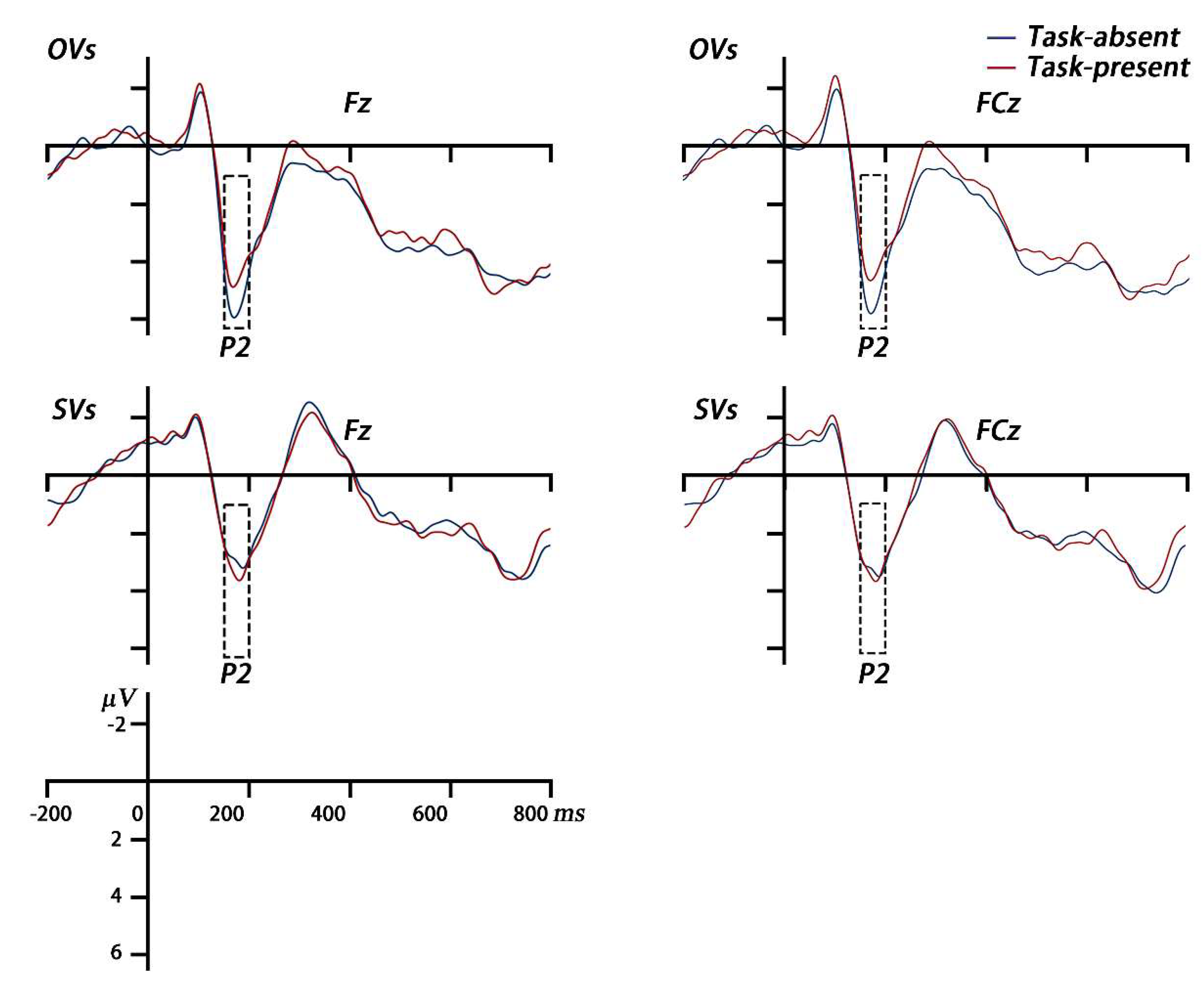

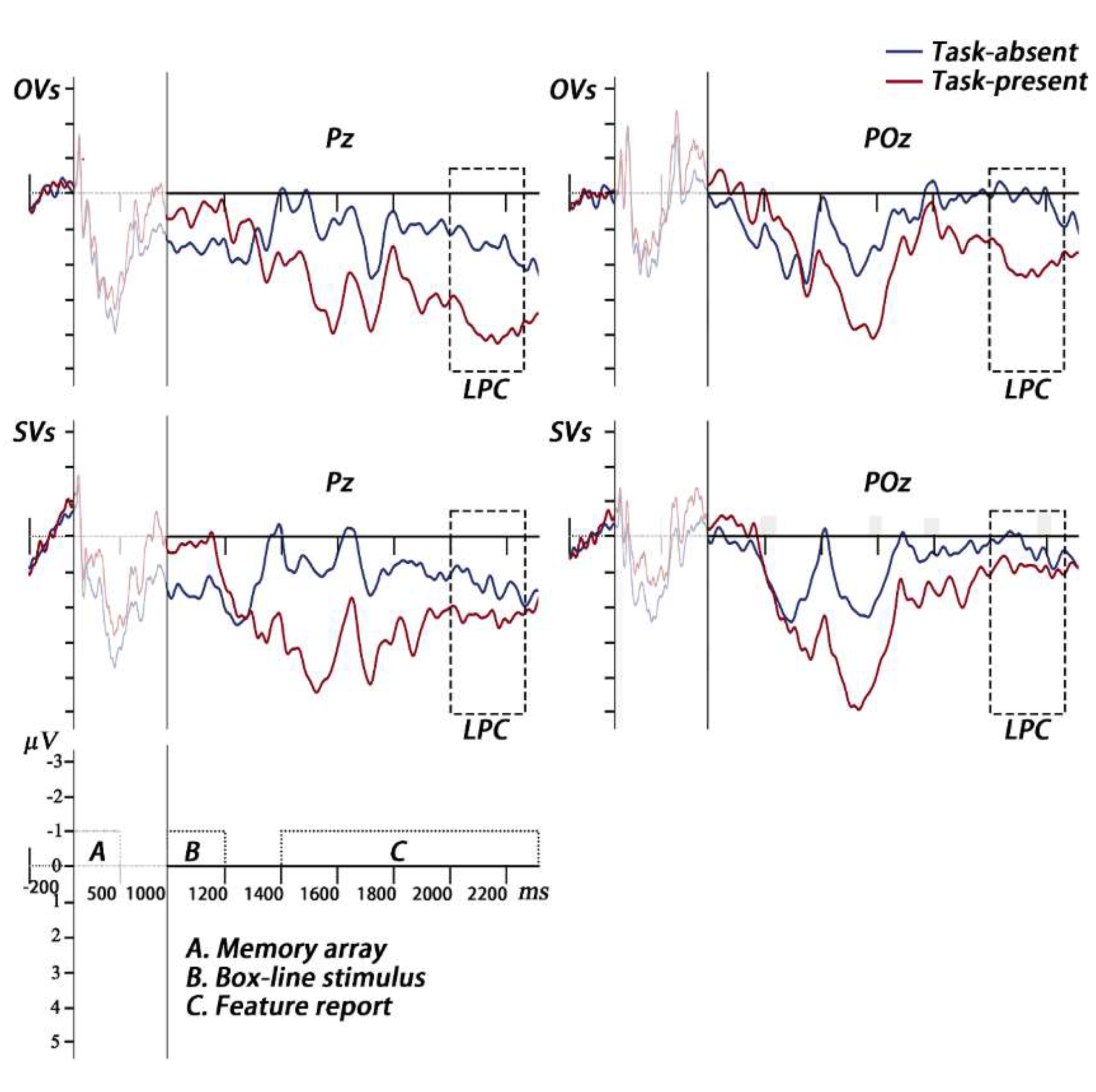

ERP analysis. The epochs were baseline-corrected using a period from -200ms to 0ms relative to the onset of the memory array and averaged for each condition to obtain grand average waveforms. Based on the previous studies and the timing of grand average ERPs, the mean amplitude of P2 was calculated at the electrode sites of Fz and FCz at 160–200ms (Pinal et al. 2015, Wolach and Pratt 2001). And the mean amplitude of LPC was calculated at the electrode sites of Pz and POz at 2000–2250ms during the secondary task period, that is, 1000–1250ms after the presentation of the feature report task (Gunseli et al. 2014a, Gunseli et al. 2014b). The mean amplitudes of P2 and LPC were analyzed in using a two-way mixed repeated measures ANOVA.

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Behavioral results

A 2 cognitive style × 2 secondary task two-way mixed, repeated measures ANOVA on the accuracy was conducted. The main effect of the secondary task was significant, F (1, 33) = 139.12, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.81, showing that the performance was better in the task-absent condition (M = 0.78, 95%CI [0.76, 0.81]) than in the task-present condition (M = 0.67, 95%CI [0.65, 0.70]). The main effect of the cognitive style was marginal significant, F (1, 33) = 3.55, p = 0.068, ηp2 = 0.10, showing that OVs (MOVs = 0.75, 95%CI [0.72, 0.78]) performed better than SVs (MSVs = 0.71, 95%CI [0.68, 0.74]). The interaction was marginal significant, F (1, 33) = 3.21, p = 0.082, ηp2 = 0.09. A simple effect analysis showed that the OVs (M = 0.81, 95%CI [0.78, 0.85]) performed better than SVs (M = 0.75, 95%CI [0.72, 0.79]) under the task-absent condition, F (1, 33) = 5.17, p = 0.030, ηp2 = 0.14; while they performed comparable under the task-present condition (MOVs = 0.69, 95%CI [0.66, 0.72] vs. MSVs = 0.66, 95%CI [0.63, 0.69]), F (1, 33) = 1.22, p = 0.277, ηp2 = 0.04. We conducted an independent samples t-tests on the costs, showing that the cost was marginal larger for OVs (M = 0.13, 95%CI [0.10, 0.15]) than SVs (M = 0.09, 95%CI [0.07, 0.12]), t(33) = 1.79, p = 0.082, Cohen’s d = 0.62.

4.2.3 ERP results

P2. A 2 cognitive style × 2 secondary task two-way mixed, repeated measures ANOVA on the P2 amplitude was conducted. The main effect of the secondary task was not significant (

Mtask-absent = 4.30μV, 95%CI [3.08, 5.52] vs.

Mtask-present = 2.91μV, 95%CI [2.67, 5.15]),

F (1, 33) = 1.79,

p = 0.190, η

p2 = 0.05. The main effect of the cognitive style was not significant (

MOVs = 4.89μV, 95%CI [3.22, 6.56] vs.

MSVs = 3.32μV, 95%CI [1.60, 5.03]),

F (1, 33) = 1.80,

p = 0.189, η

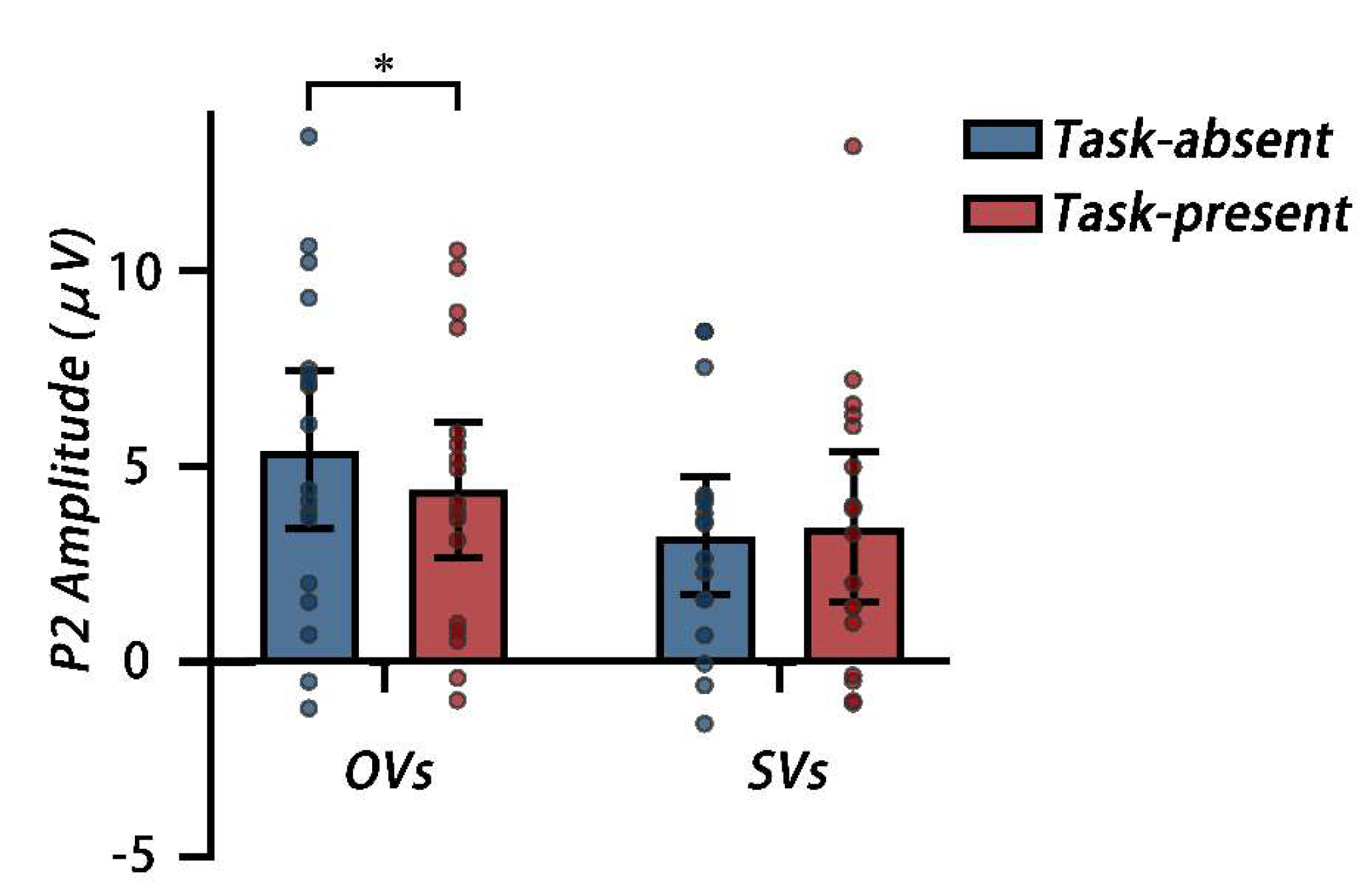

p2 = 0.05. The interaction was significant,

F (1, 33) = 4.60,

p = 0.039, η

p2 = 0.12. A simple effect analysis showed that for OVs, the P2 amplitude was lower under the task-present condition than that under the task-absent condition,

F (1, 33) = 6.24,

p = 0.018, η

p2 = 0.16. For SVs, no difference was observed between task-absent and -present conditions,

F (1, 33) = 0.32,

p = 0.578, η

p2 = 0.01(see

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

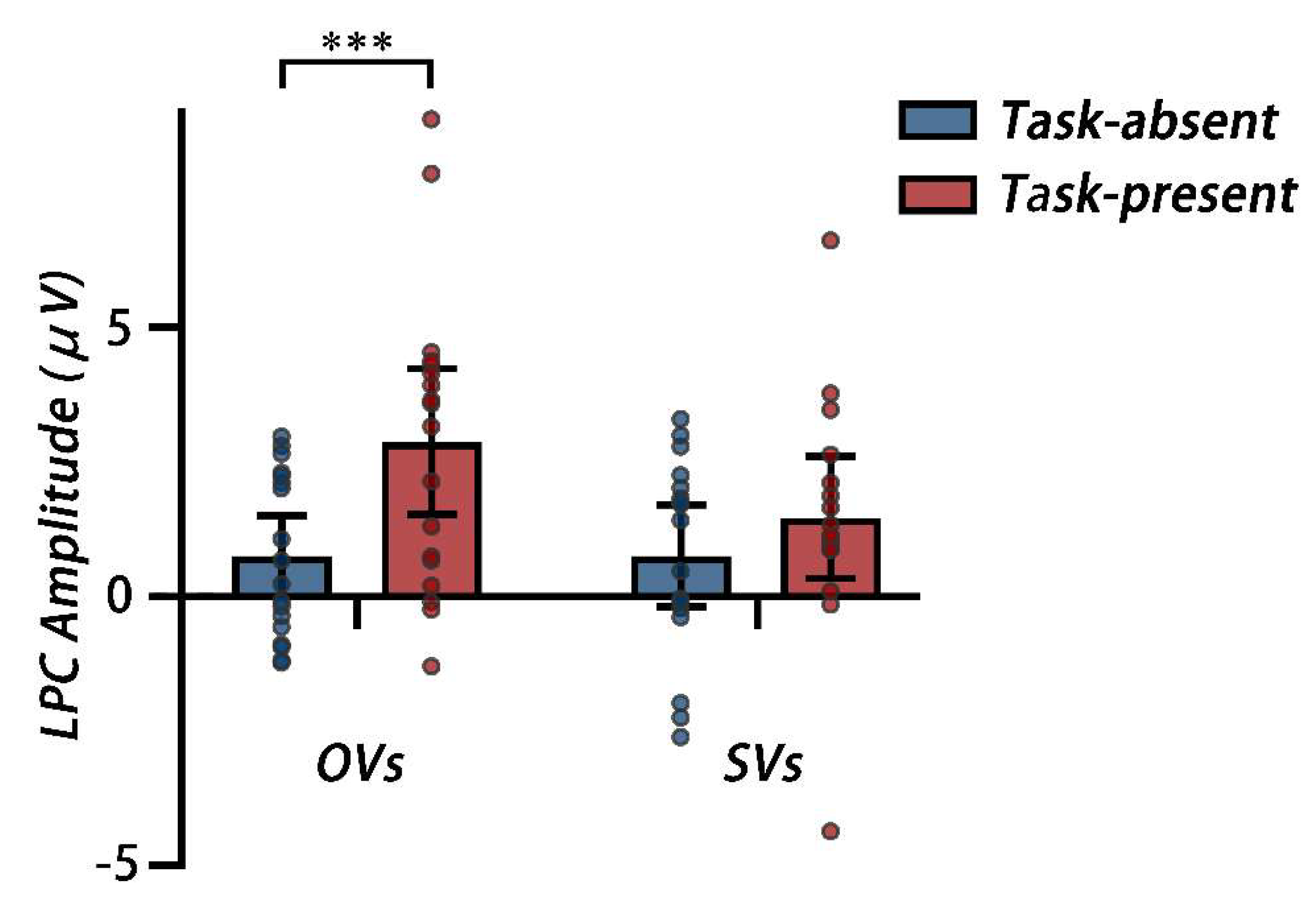

LPC. A 2 cognitive style × 2 secondary task two-way mixed, repeated measures ANOVA on the LPC amplitude was conducted. The main effect of the secondary task was significant,

F (1, 33) = 18.58,

p < 0.001, η

p2 = 0.36, showing that the LPC amplitude under the task-present condition (

M = 2.18μV, 95%CI [1.32, 3.04]) was larger than those under the task-absent condition (

M = 0.76μV, 95%CI [0.18, 1.34]). The main effect of the cognitive style was not significant (

MOVs = 1.82μV, 95%CI [0.91, 2.74] vs.

MSVs = 1.12μV, 95%CI [1.18, 2.06]),

F (1, 33) = 1.20,

p = 0.281, η

p2 = 0.03. The interaction between was significant,

F (1, 33) = 4.66,

p = 0.038, η

p2 = 0.12. A simple effect analysis showed that for OVs, the LPC amplitude was larger under the task-present condition than under the task-absent condition,

F (1, 33) = 21.54,

p < 0.001, η

p2 = 0.40; for SVs, no difference was observed between the two conditions,

F (1, 33) = 2.25,

p = 0.143, η

p2 = 0.06 (see

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

4.3. Discussion

In Experiment 3, we investigated how OVs and SVs allocate object-based attention when holding bindings in VWM. Participants reported one question of the box or the line in the secondary task during the maintenance of bindings in VWM. ERP was recorded during the VWM encoding and the secondary task performing. Behavioral result showed that the cost of consuming object-based attention for OVs was marginal larger than that of SVs. The ERP results showed that when holding bindings in VWM, compared to under the task-absent condition, OVs evoked lower P2 during VWM encoding and larger LPC during the secondary task performing under the task-present condition; while SVs evoked equal P2s and LPCs under both conditions. The divergent neural patterns between OVs and SVs suggest the differences in how they engage resources when maintaining bindings in VWM.

5. General discussion

In the present study, we explored whether the visualizer cognitive style modulates the role of object-based attention in maintaining bindings in VWM. Behavioral results showed that, compared to SVs, OVs showed advantage in holding binding representations, and had a larger cost from the secondary task consuming object-based attention in maintaining bindings compared to maintaining features. ERP results showed that, compared to SVs, OVs elicited lower P2 during VWM encoding and larger LPC during the secondary task performing in the task-present condition than task-absent condition.

5.1. Visual Cognitive Style Modulates the Role of Object-based Attention in Holding Bindings in VWM

Previous studies have found that holding bindings in VWM requires more object-based attention than holding features, which highlighting a crucial role for object-based attention in binding maintenance in VWM (Che et al. 2019, Gao et al. 2017, He et al. 2020, Lu et al. 2019, Shen et al. 2015, Wan et al. 2020, Zhou et al. 2021). In the present study, we found that when confronted with task-consuming object-based attention, OVs incurred larger cost of consuming object-based attention in holding bindings in VWM than SVs did, while OVs and SVs showed comparable cost in holding features. These results indicate that the visualizer cognitive style modulates the demand for object-based attention while holding bindings in VWM.

OVs and SVs have different visual processing styles. OVs tend to encode multiple parts of an object as a single unit and process information holistically; whereas SVs focus on discrete parts of an object and process information analytically (for review, see Kozhevnikov & Blazhenkova, 2013). According to the integrated competition model (Duncan et al. 1997), when an individual directs object-based attention to a feature of a multiple-feature object, activity in the neural regions dealing with that feature will first be enhanced and then spread to neural regions dealing with the other features within that object. Accordingly, less object-based attention may induce lower neural activity dealing with features of object, leading to an unstable VWM representation. In the present study, compared to SVs, OVs who process information holistically can more easily integrate multi-features into one object, depending more on object-based attention (e.g., Hu et al. 2020). Therefore, when performing the secondary task, OVs invest more object-based attention and their neural activity in processing multiple-feature objects was reduced, relative to that of the SVs.

OVs and SVs differ in the relative efficiency of the neural pathways responsible for processing bindings. It was demonstrated that OVs have greater efficiency in the ventral pathway in object-related tasks compared to SVs (Motes et al. 2008). The ventral pathway is responsible for object processing and to be relatively more involved in object-based attention (Cavanagh et al. 2023, Cohen and Frank 2015). In the present study, participants completed a VWM task requiring holding features or bindings while performing a secondary task necessitating object-based attention. OVs with greater efficiency in the ventral pathway tend to adjust their resources investment more flexibly according to the requirement of object-based attention, compared to SVs. Therefore, OVs had a larger cost in holding bindings than features in VWM depending on whether or not the secondary task consumed object-based attention; while SVs with lower efficiency in the ventral pathway had equal costs in holding features and bindings between the tasks that did or did not consume object-based attention.

5.2 On-Demand Resources of Object-based Attention in Holding Bindings

In Experiment 3, participants were required to complete a binding VWM task with or without a secondary task. The P2 was recorded during the presentation of the memory items. Results showed that OVs elicited a lower P2 during VWM encoding under the task-present condition than the task-absent condition, whereas SVs elicited equal P2s across conditions. P2 serves as a neural marker of attentional allocation in VWM (Smith 1993, Wolach and Pratt 2001). In Smith’s (1993) study, participants were required to remember words in a ‘study-phase’ and then judge whether or not those words had been previously studied in a ‘test-phase’. During the ‘study-phase’, the P2 was larger for words that were correctly recognized during the ‘test-phase’ compared to those that were not recognized. Researcher proposed that P2 might be involved with the engagement of attentional or working memory resources. In another study (Wolach & Pratt, 2001), participants were sequentially presented with two memory digits and two distractors. P2 was recorded during the presentation of both memory digits and distractors. The memory digits elicited larger P2 than the distractors. The larger P2 indicated the increased attention allocation to the memory digits than the distractors in working memory. Thus, in our study, the lower P2 indicates that OVs allocated attenuated attention during binding VWM encoding under the task-present condition than under the task-absent condition. Moreover, given that object-based attention contributes to the encoding of binding representations in VWM (Cohen and Frank 2015, Schoenfeld et al. 2014), our finding suggests that, compared to the task-absent condition, OVs allocated less object-based attention when encoding bindings with a secondary task in VWM; whereas SVs allocate equivalent object-based attention across both conditions. This reduced allocation of object-based attention resources during VWM encoding may enable OVs to conserve more attention resources for subsequent tasks during VWM maintenance, compared to SVs.

As for LPC, some studies point to a relationship between LPC and the effort required to perform working memory tasks (Cavanagh et al. 2023, Cohen and Frank 2015, Gunseli et al. 2014a, Gunseli et al. 2014b, Ruchkin et al. 1990). In one study (Gunseli et al. 2014a), participants were required to maintain VWM representations for the subsequent simple search task (target color different from distractors) and difficult search task (target color same as distractors). Larger LPC was evoked in the difficult search task than simple search task, indicates that LPC indexes the effort invested in the VWM maintenance. In the present study, participants required to complete a secondary task while retaining bindings. The secondary task increased the overall task difficulty and the demand of object-based attention, competed for limited resources with the binding maintaining process. OVs invested more effort in maintaining bindings when performing the secondary task, manifested as a larger LPC. While SVs invested consistent effort in binding maintenance, regardless of the presence or absence of the secondary task, manifested as similar LPCs across the task conditions.

Taken together, these findings suggest that, compared to SVs, OVs can more flexibly adjust their object-based attention investment in binding VWM and their effort to allocate relevant object-based attention in performing the secondary task according to the task demand. This demonstrates a voluntary way for individuals to modulate the object-based attention during binding VWM, such on-demand resources constitute the mechanism underlying the role of object-based attention in retaining bindings in VWM. The theory of object-based attention in retaining bindings in VWM is further elucidated as an on-demand resources when allocating such attention.

In general, our results reveal that object-based attentional investment in holding bindings in VWM is modulated by the visualizer cognitive style, with OVs having a larger investment compared with SVs. The mechanism underlying this modulation is based on the allocation of on-demand resources to meet the task requirements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Li, R. Z., Zhang, Q. and Li, S. X.; methodology, Li, R. Z., Zhang, Q. and Li, S. X.; software, Li, S. X.; validation, Li, R. Z., Wei, F. L., Zhang, Q. and Li, S. X.; formal analysis, Li, R. Z.; investigation, Li, R. Z. and Wei, F. L.; resources, Li, S. X.; data curation, Li, R. Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Li, R. Z.; writing—review and editing, Li, R. Z., Hyönä, J., Zhang, Q. and Li, S. X.; visualization, Li, R. Z.; supervision, Li, S. X.; project administration, Zhang, Q. and Li, S. X.; funding acquisition, Zhang, Q. and Li, S. X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

National Science and Technology Innovation 2030 Major Project of China, grant number 2021ZD0203800. National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 32100844.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology at Shandong Normal University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VWM |

Visual working memory |

| OV |

Object visualizer |

| SV |

Spatial visualizer |

| OSIQ |

Object–Spatial Imagery Questionnaire |

| OSIQ-R |

Chinese revised version of the Object-Spatial Imagery Questionnaire |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| RT |

Reaction time |

| LPC |

Late positive component |

| ERP |

Event-relate potential |

| EEG |

Electroencephalography |

| VEOG |

Vertical electrooculogram |

| HEOG |

Horizontal electrooculogram |

| ICA |

Independent component analysis |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Performance of the Secondary Tasks

For Experiment 2, the accuracy and RT data were analyzed using a two-way mixed, repeated measures ANOVA. The cognitive style (OVs vs. SVs) was the between-subjects factor and the probe type (feature vs. binding) was the within-subjects factor. For the RT data, only trials with correct responses and within three standard deviations from the mean were analyzed. For Experiment 3, the accuracy and RT data were analyzed using an independent-samples t-test between OVs and SVs.

The accuracy and RT of the secondary task in Experiments 2 and 3 are shown in

Table A1. For Experiment 2, the main effect of the cognitive style and the probe type was not significant in accuracy (

p1 = 0.509;

p2 = 0.867) or RT (

p1 = 0.621;

p2 = 0.694). The interaction of the cognitive style and the probe tyle was not significant, neither for accuracy (

p = 0.686) nor RT (

p = 0.220). For Experiment 3, no significant difference was observed between OVs and SVs in accuracy (

p = 0.744) or RT (

p = 0.794). The results suggest that the secondary task exerts a similar effect on both the cognitive styles and the probe type.

Table A1.

Accuracy and RT of the secondary task in each probe condition in Experiment 2 and 3.

Table A1.

Accuracy and RT of the secondary task in each probe condition in Experiment 2 and 3.

| Exp. |

Probe Type |

Accuracy [95% CI] |

|

RT (ms) [95% CI] |

| OVs |

SVs |

|

OVs |

SVs |

| 2 |

Feature |

0.86 [0.83, 0.89] |

0.85 [0.82, 0.88] |

|

1019 [968, 1070] |

988 [937, 1039] |

| Binding |

0.83 [0.78, 0.88] |

0.86 [0.82, 0.91] |

|

1015 [952, 1078] |

998 [934, 1061] |

| 3 |

Binding |

0.84 [0.79, 0.88] |

0.83 [0.78, 0.88] |

|

1049 [988, 1109] |

1037 [975, 1100] |

References

- (Allen et al. 2006) Allen, R. J., A. D. Baddeley, and G. J Hitch. 2006. Is the binding of visual features in working memory resource-demanding? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 135: 298-313. [CrossRef]

- (Baddeley 2012) Baddeley, A. D. 2012. Working memory: theories, models, and controversies. Annual Review of Psychology 63: 1-29. [CrossRef]

- (Baddeley et al. 2021) Baddeley, Alan D, Graham Hitch, and Richard Allen. 2021. A multicomponent model of working memory. Working memory: State of the science: 10-43. [CrossRef]

- (Blajenkova et al. 2006) Blajenkova, O., M. Kozhevnikov, and M. A. Motes. 2006. Object-spatial imagery: a new self-report imagery questionnaire. Applied Cognitive Psychology 20: 239–63. [CrossRef]

- (Cavanagh et al. 2023) Cavanagh, P., G. P. Caplovitz, T. K. Lytchenko, M. R. Maechler, P. U. Tse, and D. L. Sheinberg. 2023. The Architecture of Object-Based Attention. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 30: 1643–67. [CrossRef]

- (Che et al. 2019) Che, X. W., X. W. Ding, X. L. Ling, H. L. Wang, Y. Y. Gu, and S. X. Li. 2019. Does maintaining bindings in visual working memory require more attention than maintaining features? Memory 27: 729-38. [CrossRef]

- (Cohen and Frank 2015) Cohen, Elias H, and Tong Frank. 2015. Neural mechanisms of object-based attention. Cerebral Cortex, 25: 1080-92. [CrossRef]

- (Duncan et al. 1997) Duncan, J., G. Humphreys, and R. Ward. 1997. Competitive brain activity in visual attention. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 7: 255-61. [CrossRef]

- (Faul et al. 2007) Faul, F., E. Erdfelder, A. G. Lang, and A. Buchner. 2007. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior research methods: 175-91. [CrossRef]

- (Gao et al. 2017) Gao, Z. F., F. Wu, F. F. Qiu, K. F. He, Y. Yang, and M. W. Shen. 2017. Bindings in working memory: the role of object-based attention. Attention Perception and Psychophysics 79: 533-52. [CrossRef]

- (Groppe et al. 2009) Groppe, D. M., S. Makeig, and M. Kutas. 2009. Identifying reliable independent components via split-half comparisons. Neuroimage 45: 1199-211. [CrossRef]

- (Gunseli et al. 2014a) Gunseli, E., M. Meeter, and C. N. Olivers. 2014a. Is a search template an ordinary working memory? Comparing electrophysiological markers of working memory maintenance for visual search and recognition. Neuropsychologia 60: 29-38. [CrossRef]

- (Gunseli et al. 2014b) Gunseli, E., C. N. Olivers, and M. Meeter. 2014b. Effects of search difficulty on the selection, maintenance, and learning of attentional templates. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 26: 2042-5. [CrossRef]

- (He et al. 2020) He, K. F., J. F. Li, F. Wu, X. Y. Wan, Z. F. Gao, and M. W. Shen. 2020. Object-based attention in retaining binding in working memory: Influence of activation states of working memory. Memory and Cognition 48: 957-71. [CrossRef]

- (Hollingworth and Maxcey-Richard 2013) Hollingworth, A., and A. M. Maxcey-Richard. 2013. Selective maintenance in visual working memory does not require sustained visual attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 39: 1047-58. [CrossRef]

- (Hu et al. 2020) Hu, S. S., M. Y. Liu, Y. H. Wang, and J. J. Zhao. 2020. Wholist-analytic cognitive styles modulate object-based attentional selection. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 73: 1596-604. [CrossRef]

- (Itti and Koch 2001) Itti, L. , and C. Koch. 2001. Computational modelling of visual attention. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2: 194-203. [CrossRef]

- (Johnson et al. 2008) Johnson, J. S., A. Hollingworth, and S. J. Luck. 2008. The role of attention in the maintenance of feature bindings in visual short-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 34: 41-55. [CrossRef]

- (Kozhevnikov et al. 2005) Kozhevnikov, M., S. Kosslyn, and J. Shephard. 2005. Spatial versus object visualizers: a new characterization of visual cognitive style. Memory and Cognition 33: 710-26. [CrossRef]

- (Kozhevnikov and Blazhenkova 2013) Kozhevnikov, M., and O. Blazhenkova. 2013. Individual Differences in Object Versus Spatial Imagery: From Neural Correlates to Real-World Applications. Kozhevnikov, M., & Blazhenkova, O. (2013). Individual differences in object versus spatial imagery: from neural correlates to real-world applications. In Multisensory imagery (pp. 299-318). Springer, New York, NY.: 299-318. [CrossRef]

- (Kozhevnikov et al. 2010) Kozhevnikov, Maria, Olesya Blazhenkova, and M Becker. 2010. Trade-off in object versus spatial visualization abilities: restriction in the development of visual-processing resources. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 17: 29-35. [CrossRef]

- (Li et al. 2011) Li, S. X., D. Z. Gong, S. W. Jia, W. X. Zhang, and Y. G. Ma. 2011. Object and spatial visualizers have different object-processing patterns: behavioral and ERP evidence. Neuroreport 22: 860-64. [CrossRef]

- (Lu et al. 2019) Lu, X. Q., X. C. Ma, Y. F. Zhao, Z. F. Gao, and M. W. Shen. 2019. Retaining event files in working memory requires extra object-based attention than the constituent elements. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 72: 2225-39. [CrossRef]

- (Luck and Vogel 1997) Luck, S. J. , and E. K. Vogel. 1997. The capacity of visual working memory for features and conjunctions. Nature, 390: 279-81. [CrossRef]

- (Matsukura and Vecera 2009) Matsukura, M. , and S. P. Vecera. 2009. Interference between object-based attention and object-based memory. Psychon Bull Rev, 16: 529-36. [CrossRef]

- (Motes et al. 2008) Motes, M. A., R. Malach, and M. Kozhevnikov. 2008. Object-processing neural efficiency differentiates object from spatial visualizers. Neuroreport 19: 1727-31. [CrossRef]

- (Pinal et al. 2015) Pinal, Diego, Montserrat Zurrón, and Fernando Díaz. 2015. Age-related changes in brain activity are specific for high order cognitive processes during successful encoding of information in working memory. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 7: 75. [CrossRef]

- (Ruchkin et al. 1990) Ruchkin, D. S., R. Johnson, H. Canoune, and W. Ritter. 1990. Short-term memory storage and retention: an event-related brain potential study. Electroencephalography and clinical Neurophysiology 76: 419-39. [CrossRef]

- (Schoenfeld et al. 2014) Schoenfeld, Mircea A, Hopf Jens-Max, Merkel Christian, Heinze Hans-Jochen, and Steven A Hillyard. 2014. Object-based attention involves the sequential activation of feature-specific cortical modules. Nature Neuroscience 17: 619-24. [CrossRef]

- (Shen, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. (Shen et al. 2015) Shen, M. W., X. Huang, and Z. F. Gao. 2015. Object-based attention underlies the rehearsal of feature binding in visual working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 41: 479-93. [CrossRef]

- (Smith 1993) Smith, Michael E. 1993. Neurophysiological manifestations of recollective experience during recognition memory judgments. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 5: 1-13. [CrossRef]

- (Treisman and Gelade 1980) Treisman, A. , and G. Gelade. 1980. A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognitive Psychology, 12: 97-136. [CrossRef]

- (Treisman 1998) Treisman, A. 1998. Feature binding, attention and object perception. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 353: 1295-306. [CrossRef]

- (Wan et al. 2020) Wan, X. Y., Y. Zhou, F. Wu, K. F. He, M. W. Shen, and Z. F. Gao. 2020. The role of attention in retaining the binding of integral features in working memory. Journal of vision 20: 16. [CrossRef]

- (Wheeler and Treisman 2002) Wheeler, Mary E., and Anne M. Treisman. 2002. Binding in short-term visual memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 131: 48-64. [CrossRef]

- (Wolach and Pratt 2001) Wolach, Irit, and Hillel Pratt. 2001. The mode of short-term memory encoding as indicated by event-related potentials in a memory scanning task with distractions. Clinical Neurophysiology 112: 186-97. [CrossRef]

- (Zhou et al. 2021) Zhou, Y., F. Wu, X. Y. Wan, M. W. Shen, and Z. F. Gao. 2021. Does the presence of more features in a bound representation in working memory require extra object-based attention? Memory and Cognition 49: 1583-99. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The shapes and colors used in the current study. In the feature condition, the stimuli were the shapes in black (top row), or colored noncanonical “blobs,” as shown in the middle row. In the binding condition, the stimuli were color-shape combinations, as shown in the bottom row.

Figure 1.

The shapes and colors used in the current study. In the feature condition, the stimuli were the shapes in black (top row), or colored noncanonical “blobs,” as shown in the middle row. In the binding condition, the stimuli were color-shape combinations, as shown in the bottom row.

Figure 2.

A schematic illustration of a trial in Experiment 1. Here a trial is presented with the probe present in the memory array.

Figure 2.

A schematic illustration of a trial in Experiment 1. Here a trial is presented with the probe present in the memory array.

Figure 3.

The mean accuracy for Experiment 1, error bars represent the 95%CIs, each dot corresponds to the data of an individual participant. OVs = object visualizers; SVs = spatial visualizers; *** p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

The mean accuracy for Experiment 1, error bars represent the 95%CIs, each dot corresponds to the data of an individual participant. OVs = object visualizers; SVs = spatial visualizers; *** p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

A schematic illustration of a trial used in Experiment 2. The figure depicts the trials of the feature and the binding probe conditions, in which a secondary task was used. Here a trial is presented with the probe present in the memory array.

Figure 4.

A schematic illustration of a trial used in Experiment 2. The figure depicts the trials of the feature and the binding probe conditions, in which a secondary task was used. Here a trial is presented with the probe present in the memory array.

Figure 5.

The mean accuracy for Experiment 2, each dot corresponds to the data of an individual participant. (a) The cost of the secondary task. The cost was calculated as the difference between the task-absent and task-present conditions (task-absent minus task-present). (b) Response accuracy in each condition for OVs and SVs. Error bars represent the 95%CIs, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

The mean accuracy for Experiment 2, each dot corresponds to the data of an individual participant. (a) The cost of the secondary task. The cost was calculated as the difference between the task-absent and task-present conditions (task-absent minus task-present). (b) Response accuracy in each condition for OVs and SVs. Error bars represent the 95%CIs, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 6.

A schematic illustration of a trial used in Experiment 3. Here a trial is presented with the probe present in the memory array.

Figure 6.

A schematic illustration of a trial used in Experiment 3. Here a trial is presented with the probe present in the memory array.

Figure 7.

The grand-averaged waveforms during VWM encoding. Averaged P2 waveforms for OVs and SVs in the task-absent and task-present conditions are shown at the Fz and FCz electrode sites. The rectangles show the time windows (from 160ms to 200ms after the onset of the memory array) used for the statistical analyses.

Figure 7.

The grand-averaged waveforms during VWM encoding. Averaged P2 waveforms for OVs and SVs in the task-absent and task-present conditions are shown at the Fz and FCz electrode sites. The rectangles show the time windows (from 160ms to 200ms after the onset of the memory array) used for the statistical analyses.

Figure 8.

Mean P2 amplitudes from 160ms to 200ms after the memory array onset across the Fz and FCz electrode sites for the task-absent and task-present conditions, each dot corresponds to the data of an individual participant. * p < 0.05.

Figure 8.

Mean P2 amplitudes from 160ms to 200ms after the memory array onset across the Fz and FCz electrode sites for the task-absent and task-present conditions, each dot corresponds to the data of an individual participant. * p < 0.05.

Figure 9.

The grand-averaged waveforms during the secondary task performing. Averaged LPC waveforms for object and spatial visualizers in the task-absent and task-present conditions are shown at the Pz and POz electrode sites. The rectangles show the time windows (from 2000ms to 2250ms after the onset of the memory array) used for the statistical analyses.

Figure 9.

The grand-averaged waveforms during the secondary task performing. Averaged LPC waveforms for object and spatial visualizers in the task-absent and task-present conditions are shown at the Pz and POz electrode sites. The rectangles show the time windows (from 2000ms to 2250ms after the onset of the memory array) used for the statistical analyses.

Figure 10.

Mean LPC amplitudes from 2000ms to 2250ms after the memory array onset across the Pz and POz electrode sites for the task-absent and task-present conditions, each dot corresponds to the data of an individual participant. *** p < 0.001.

Figure 10.

Mean LPC amplitudes from 2000ms to 2250ms after the memory array onset across the Pz and POz electrode sites for the task-absent and task-present conditions, each dot corresponds to the data of an individual participant. *** p < 0.001.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).