Submitted:

11 November 2024

Posted:

12 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Object vs. Spatial Imagery

1.2. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Assessments and Measures

2.2.1. Object-Spatial Imagery and Verbal Questionnaire (OSIVQ)

2.2.2. Aptitudes in Different Domains

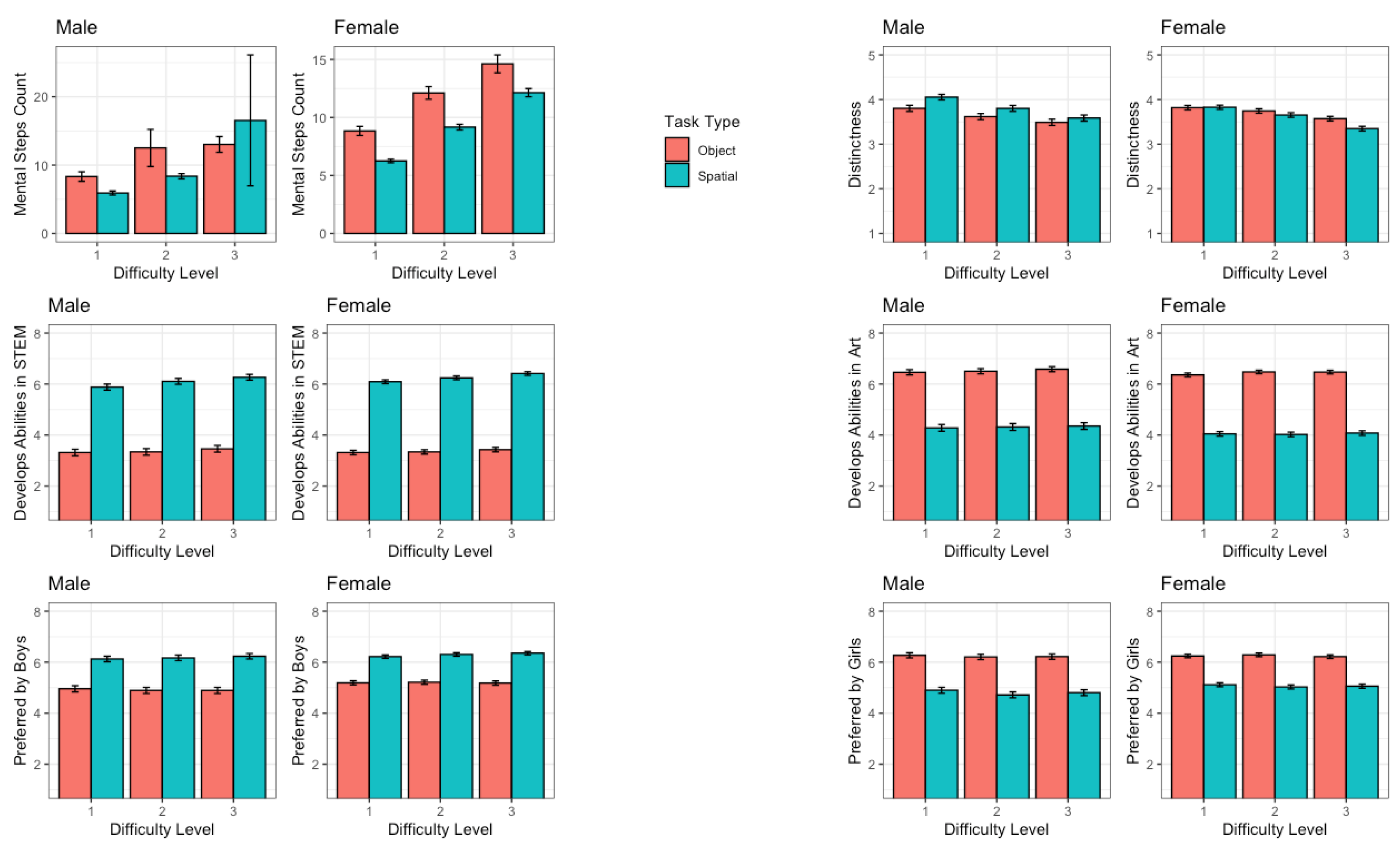

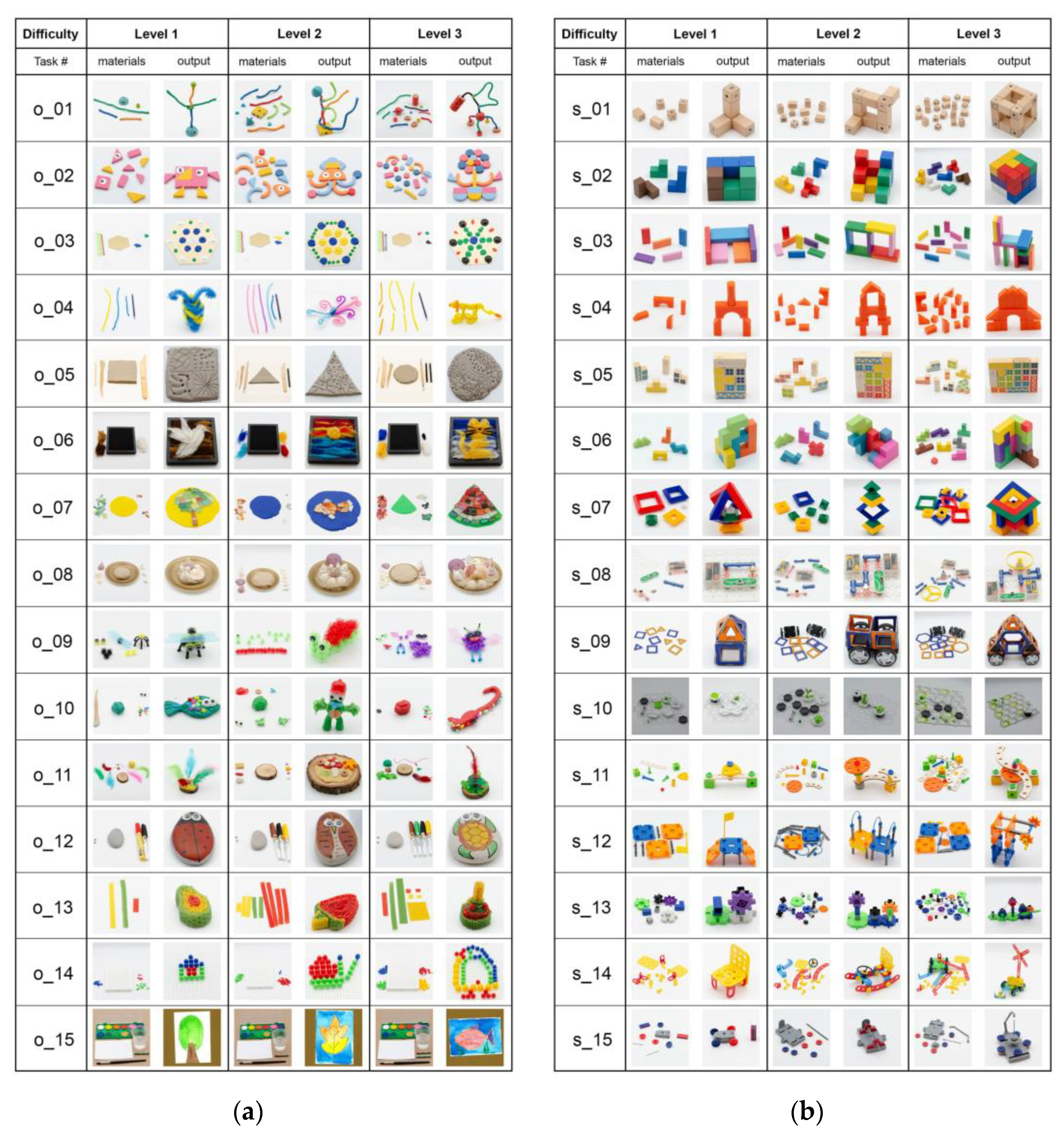

2.2.3. Imagined Assembly Tasks

3. Results

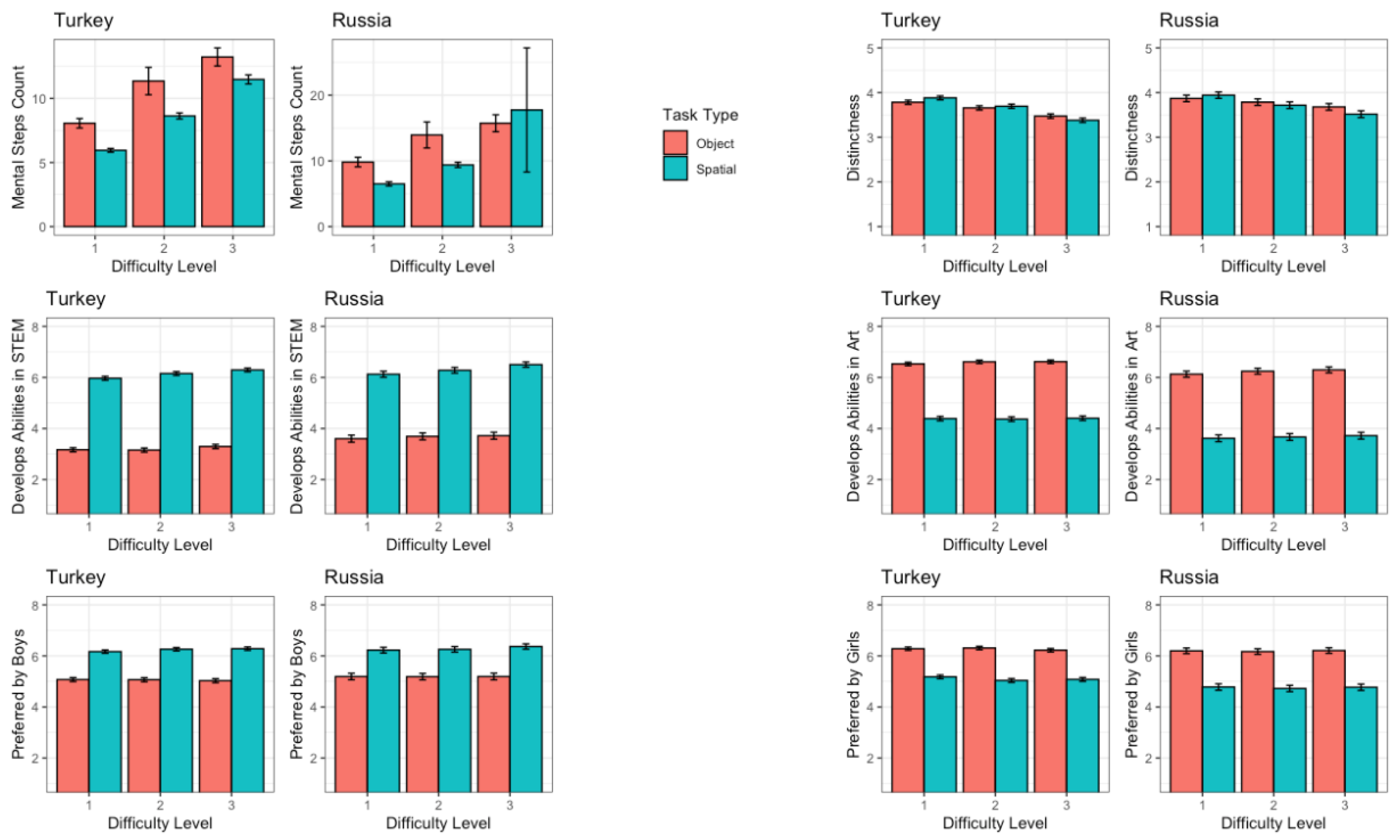

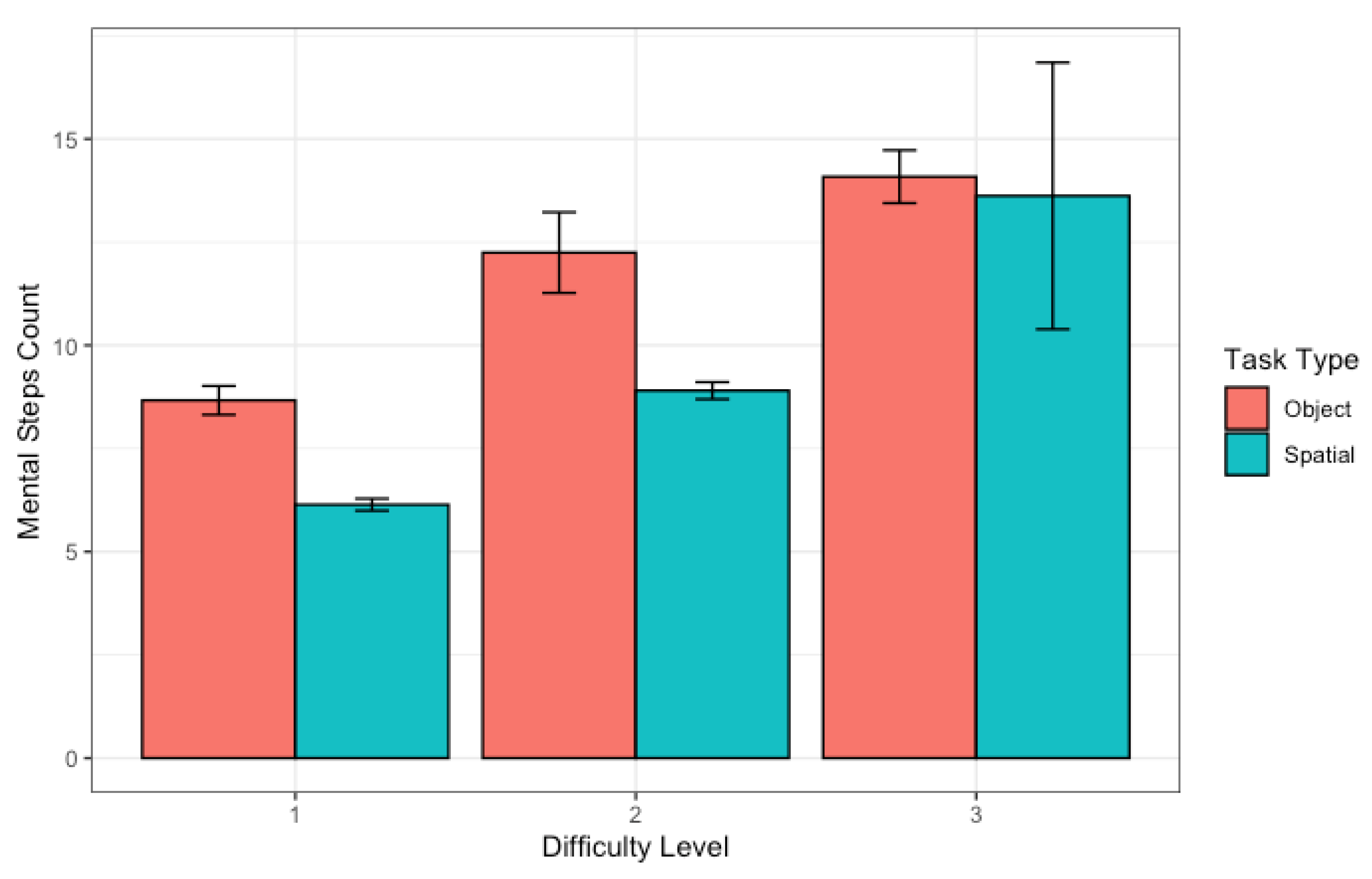

3.1. The Effects of Difficulty Level and Task Type on Cognitive Imagery Processes

3.1.1. Mental Steps Count

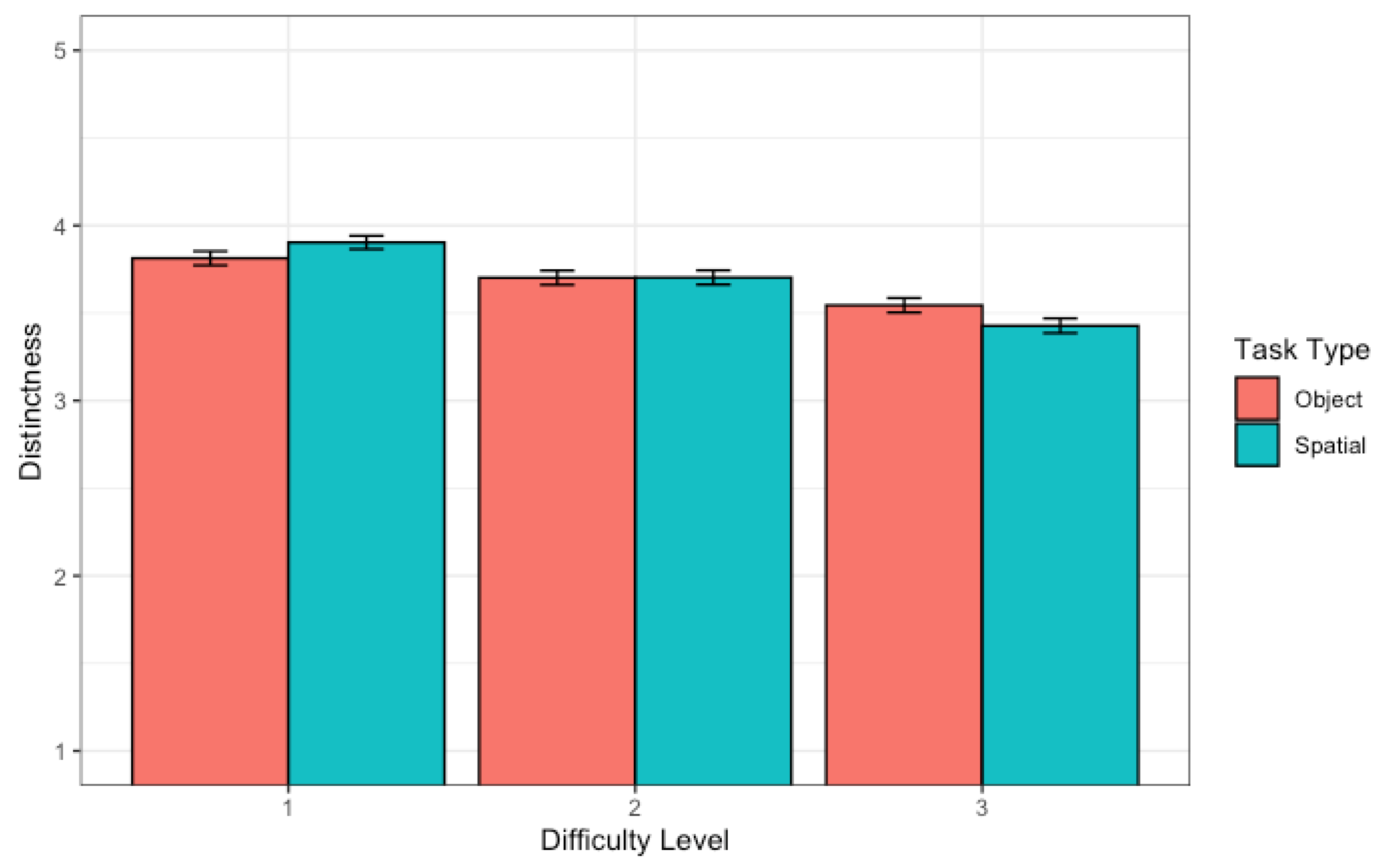

3.1.2. Imagery Distinctness

3.2. The Effects of Difficulty Level and Task Type on Educational Value and Attractiveness

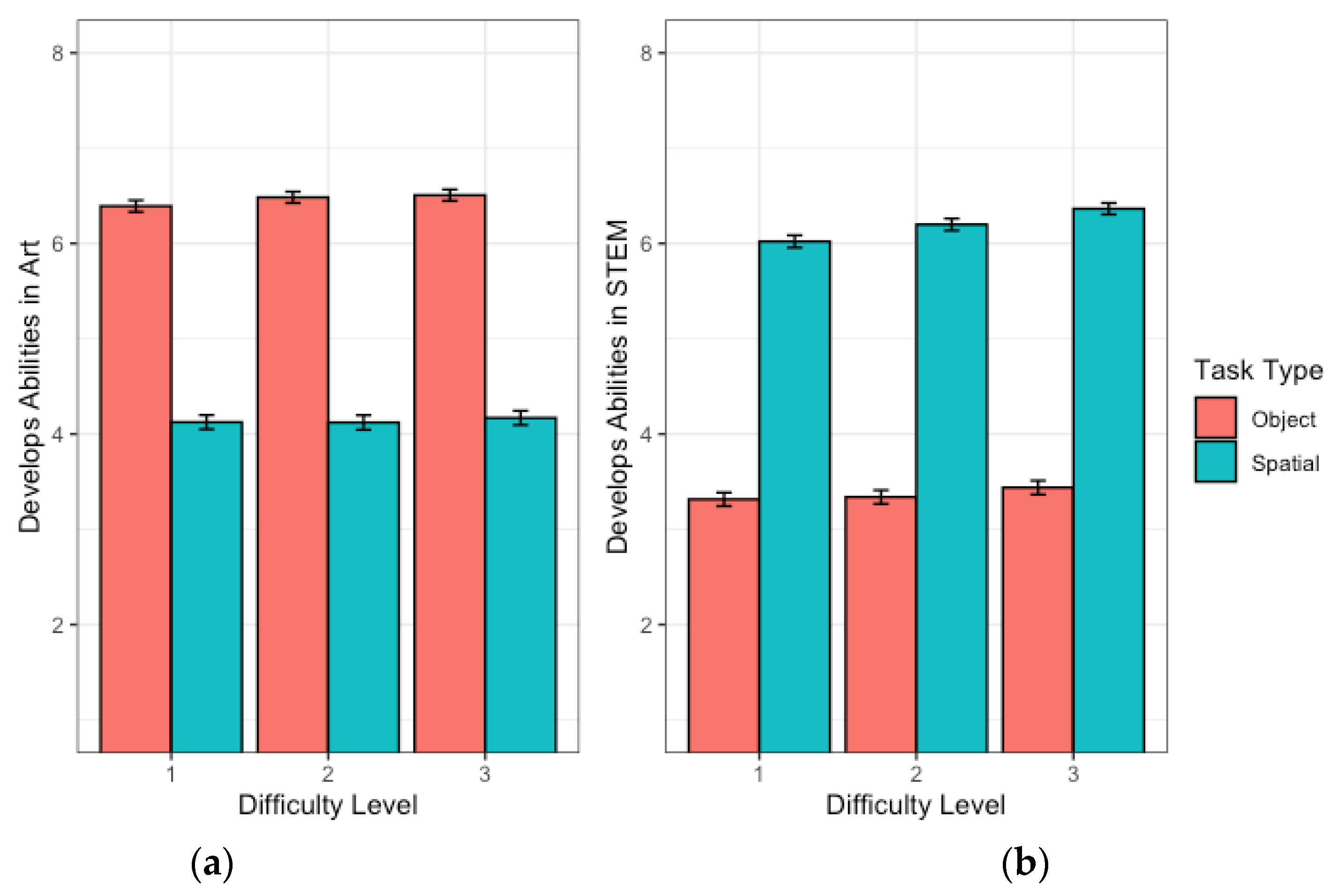

3.2.1. Educational Value in Art and STEM Domains

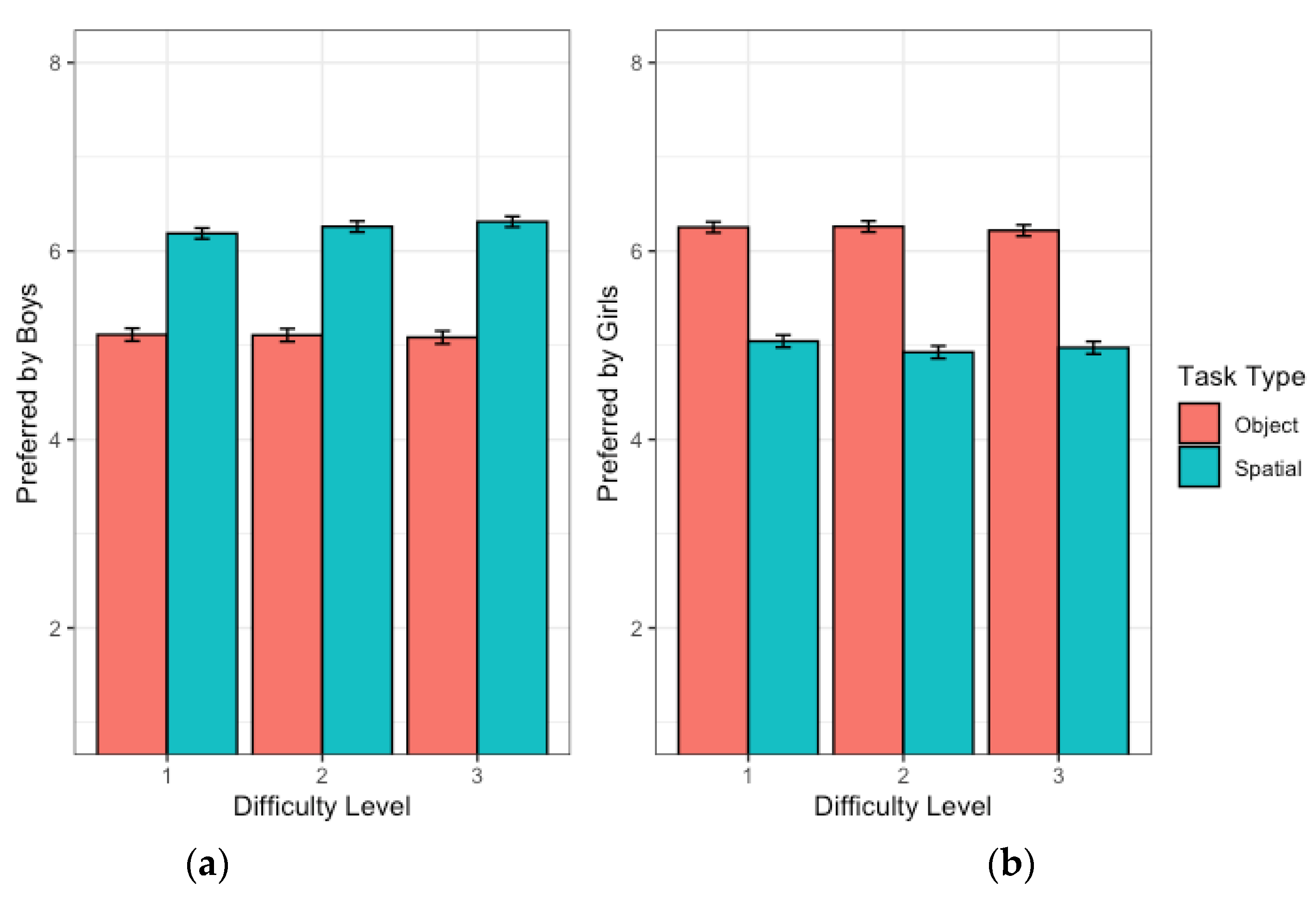

3.2.2. Attractiveness for Girls and Boys

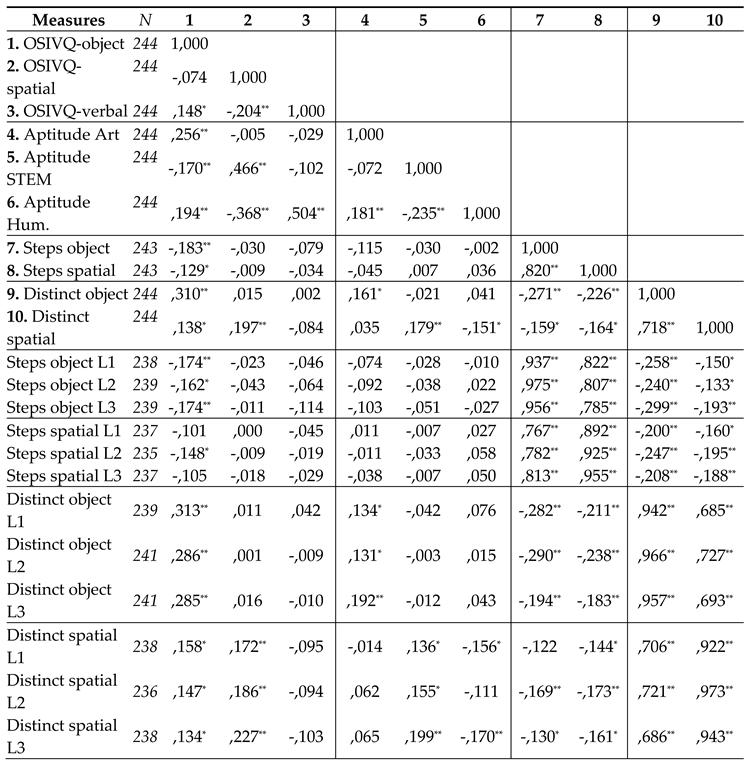

3.3. Correlations Between Individual Differences Measures and Imagined Assembly Task Cognitive Processing Measures.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influence of Task Type and Difficulty Level on Imagery Processes

4.1.1. Difficulty Level

4.1.2. Task Type

4.1.3. Difficulty Level * Task Type

4.2. Individual Differences in Imagery and Imagery Processes

4.3. Educational Value and Expected Attractiveness for Different Genders

4.4. Applications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Blazhenkova, O.; Kozhevnikov, M. Visual-Object Ability: A New Dimension of Non-Verbal Intelligence. Cognition 2010, 117, 276–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borst, G.; Kosslyn, S.M. Individual Differences in Spatial Mental Imagery. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. (Hove) 2010, 63, 2031–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Jeter, C.B.; Yang, D.; Montague, P.R.; Eagleman, D.M. Vividness of Mental Imagery: Individual Variability Can Be Measured Objectively. Vision Res. 2007, 47, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angiulli, A.; Runge, M.; Faulkner, A.; Zakizadeh, J.; Chan, A.; Morcos, S. Vividness of Visual Imagery and Incidental Recall of Verbal Cues, When Phenomenological Availability Reflects Long-Term Memory Accessibility. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, D.F. Visual Imagery Differences in the Recall of Pictures. Br. J. Psychol. 1973, 64, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeman, A. Aphantasia and Hyperphantasia: Exploring Imagery Vividness Extremes. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishkin, M.; Ungerleider, L.G.; Macko, K.A. Object Vision and Spatial Vision: Two Cortical Pathways. Trends Neurosci. 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, N.; Bosch, S.E.; van Gerven, M.A.J. Shared Neural Mechanisms of Visual Perception and Imagery. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, M.J. Is Visual Imagery Really Visual? Overlooked Evidence from Neuropsychology. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 95, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhevnikov, M.; Kosslyn, S.; Shephard, J. Spatial versus Object Visualizers: A New Characterization of Visual Cognitive Style. Mem. Cognit. 2005, 33, 710–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausburn, L.J.; Ausburn, F.B. Cognitive Styles: Some Information and Implications for Instructional Design. Educ. Commun. Technol. 1978, 26, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazhenkova, O.; Kanero, J.; Duman, I.; Umitli, O. Read and Imagine: Visual Imagery Experience Evoked by First versus Second Language. Psychol. Rep. 2023, 332941231158059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhevnikov, M.; Motes, M.A.; Hegarty, M. Spatial Visualization in Physics Problem Solving. Cogn. Sci. 2007, 31, 549–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGee, M.G. Human Spatial Abilities: Psychometric Studies and Environmental, Genetic, Hormonal, and Neurological Influences. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 889–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphreys, L.G.; Lubinski, D.; Yao, G. Utility of Predicting Group Membership and the Role of Spatial Visualization in Becoming an Engineer, Physical Scientist, or Artist. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passolunghi, M.C.; Mammarella, I.C. Selective Spatial Working Memory Impairment in a Group of Children with Mathematics Learning Disabilities and Poor Problem-Solving Skills. J. Learn. Disabil. 2012, 45, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, M.; Waller, D.A. Individual Differences in Spatial Abilities. In The Cambridge Handbook of Visuospatial Thinking; Shah, P., Miyake, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyer, D.; Jansen, P. Motor Expertise and Performance in Spatial Tasks: A Meta-Analysis. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2017, 54, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhevnikov, M.; Kozhevnikov, M.; Yu, C.J.; Blazhenkova, O. Creativity, Visualization Abilities, and Visual Cognitive Style. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 83 Pt 2, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazhenkova, O.; Kozhevnikov, M. Types of Creativity and Visualization in Teams of Different Educational Specialization. Creat. Res. J. 2016, 28, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazhenkova, O.; Kozhevnikov, M. Creative Processes during a Collaborative Drawing Task in Teams of Different Specializations. Creat. Educ. 2020, 11, 1751–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, B.T.; Schunn, C.D. The Role and Impact of Mental Simulation in Design. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2009, 23, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, J.J. Analogical reasoning via imagery: The role of transformations and simulations. https://srri.umass.edu/sites/srri/files/Clement-Analogy-Imagery/index.pdf (accessed 2024-11-09).

- Kersh, J.; Casey, B.M.; Young, J.M. Research Spatial Skills Block Building Girls Boys. Contemporary Perspectives Mathematics Early Childhood Education.

- Brosnan, M.J. Spatial Ability in Children’s Play with Lego Blocks. Percept. Mot. Skills 1998, 87, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldera, Y.M.; Culp, A.M.; O’Brien, M.; Truglio, R.T.; Alvarez, M.; Huston, A.C. Children’s Play Preferences, Construction Play with Blocks, and Visual-Spatial Skills: Are They Related? Int. J. Behav. Dev. 1999, 23, 855–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, S.C.; Ratliff, K.R.; Huttenlocher, J.; Cannon, J. Early Puzzle Play: A Predictor of Preschoolers’ Spatial Transformation Skill. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprafkin, J.; Swift, C.; Hess, R. The Changing Image of Television. Prev. Hum. Serv. 1983, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, M.; Héroux, G. Visuo-spatial Play Experience: Forerunner of Visuo-spatial Achievement in Preadolescent and Adolescent Boys and Girls? Infant Child Dev. 2004, 13, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazhenkova, O.; Booth, R.W. Individual Differences in Visualization and Childhood Play Preferences. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAvinue, L.P.; Robertson, I.H. Measuring Visual Imagery Ability: A Review. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 2007, 26, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazhenkova, O.; Kozhevnikov, M. The New Object-Spatial-Verbal Cognitive Style Model: Theory and Measurement. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2009, 23, 638–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazhenkova, O. Vividness of Object and Spatial Imagery. Percept. Mot. Skills 2016, 122, 490–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazhenkova, O. (2024, July 15). Visual-object and visual-spatial play. Retrieved from osf.io/6nuzg.

- Blazhenkova, O.; Asilkefeli, E.; Kotov, A.; Kotova, T.; Bostancı, E.; Roshchina, V. Interrelations between Mothers’ and Children’s Abilities, Learning Interests, and Play in Object and Spatial Visual Domains, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zacks, J.M.; Swallow, K.M. Event Segmentation. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Yakov, A.; Henson, R.N. The Hippocampal Film Editor: Sensitivity and Specificity to Event Boundaries in Continuous Experience. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 10057–10068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepard, R.N.; Metzler, J. Mental Rotation of Three-Dimensional Objects. Science 1971, 171, 701–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceja, C.R.; Franconeri, S.L. Difficulty Limits of Visual Mental Imagery. Cognition 2023, 236, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, R.; Pearson, J. The Perceptual and Phenomenal Capacity of Mental Imagery. Cognition 2017, 162, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, S.C.; Engelhard, I.M.; van den Hout, M.A. The Effects of Eye Movements on Emotional Memories: Using an Objective Measure of Cognitive Load. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2016, 7, 30122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazhenkova, O.; Kotov, A.A.; Kotova, T. How People Estimate the Prevalence of Aphantasia and Hyperphantasia in the Population. PsyArXiv, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Blazhenkova, O.; Becker, M.; Kozhevnikov, M. Object–Spatial Imagery and Verbal Cognitive Styles in Children and Adolescents: Developmental Trajectories in Relation to Ability. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2011, 21, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyer, D.; Voyer, S.; Bryden, M.P. Magnitude of Sex Differences in Spatial Abilities: A Meta-Analysis and Consideration of Critical Variables. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbin, L.A.; Connor, J.M. Sex-Typing of Children’s Play Preferences and Patterns of Cognitive Performance. J. Genet. Psychol. 1979, 134, 315–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A.; Gore, J.; Holmes, K.; Smith, M.; Fray, L. Parental Influences on Those Seeking a Career in STEM: The Primacy of Gender. International Journal of Gender, Science, and Technology 2018, 10, 308–328. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton-Smith, B.; Rosenberg, B.G. Impulsivity and Sex Preference. J. Genet. Psychol. 1961, 98, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, B. Gender, Toys and Learning. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2010, 36, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussey, K.; Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Gender Development and Differentiation. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 106, 676–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langlois, J.H.; Downs, A.C. Mothers, Fathers, and Peers as Socialization Agents of Sex-Typed Play Behaviors in Young Children. Child Dev. 1980, 51, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boe, J.L.; Woods, R.J. Parents’ Influence on Infants’ Gender-Typed Toy Preferences. Sex Roles 2018, 79, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).