Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

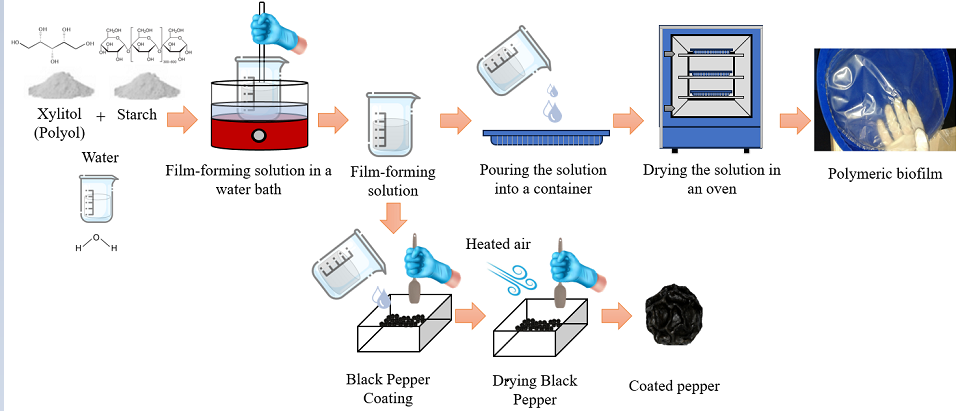

2.2. Production of Film-Forming Solution (ffs) and Biodegradable Films

2.3. Characterization of Biodegradable Films

2.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy with Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR-ATR)

2.3.2. Thickness

2.3.3. Water Vapor Permeability (WVP)

2.3.4. Solubility

2.3.5. Mechanical Properties

2.4. Coating of Black Pepper Seeds

2.5. Monitoring the Stability of Black Pepper Seeds

2.5.1. Análise Microbiológica

2.5.2. Instrumental Color

2.5.3. Water Activity

2.5.4. Moisture

2.5.5. Apparent and Absolute Specific Mass

2.5.6. Particle Porosity

2.5.7. Weight of a Thousand Seeds

2.5.8. Mass Loss (%)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

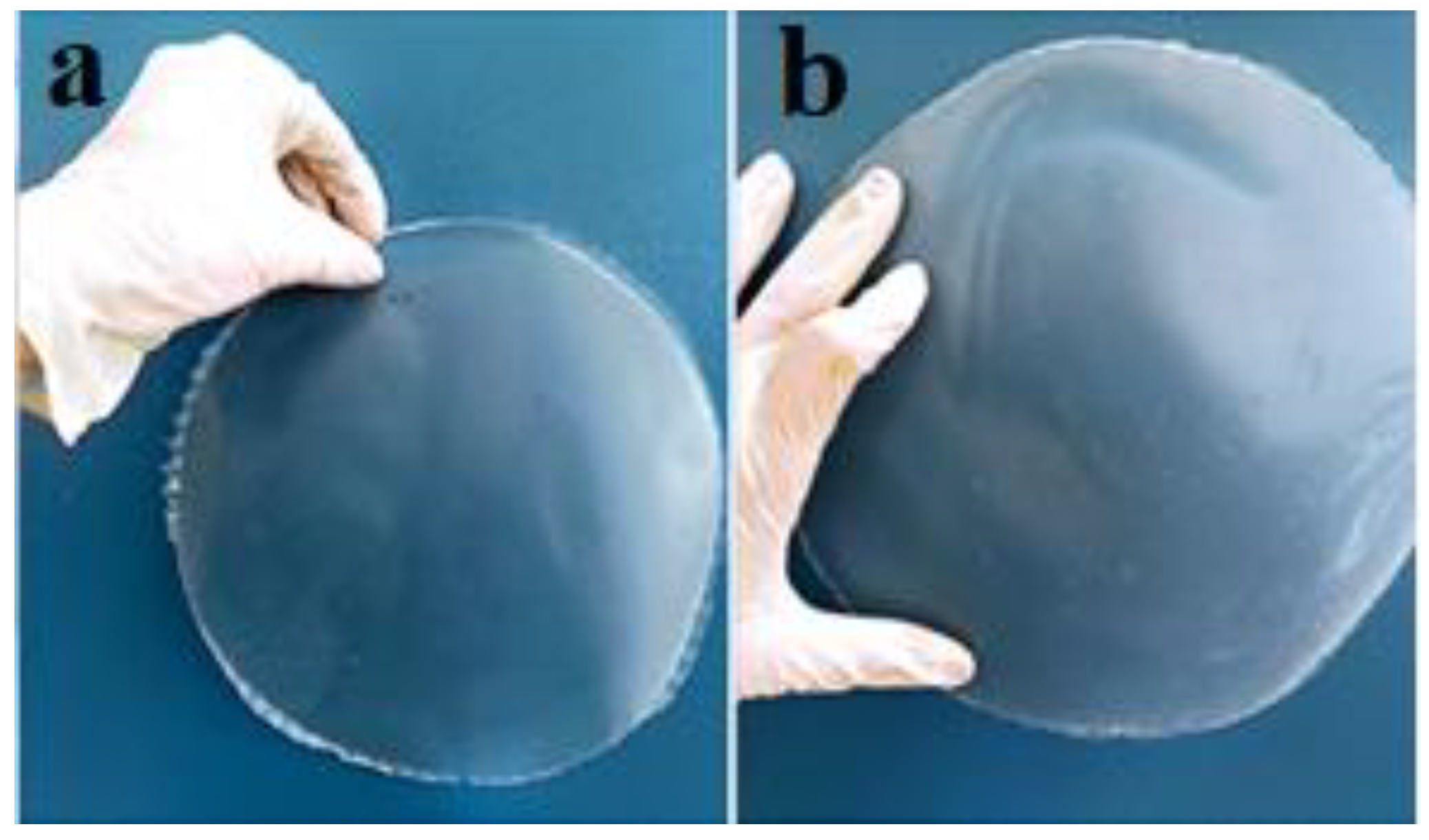

3.1. Characterization of Biodegradable Films

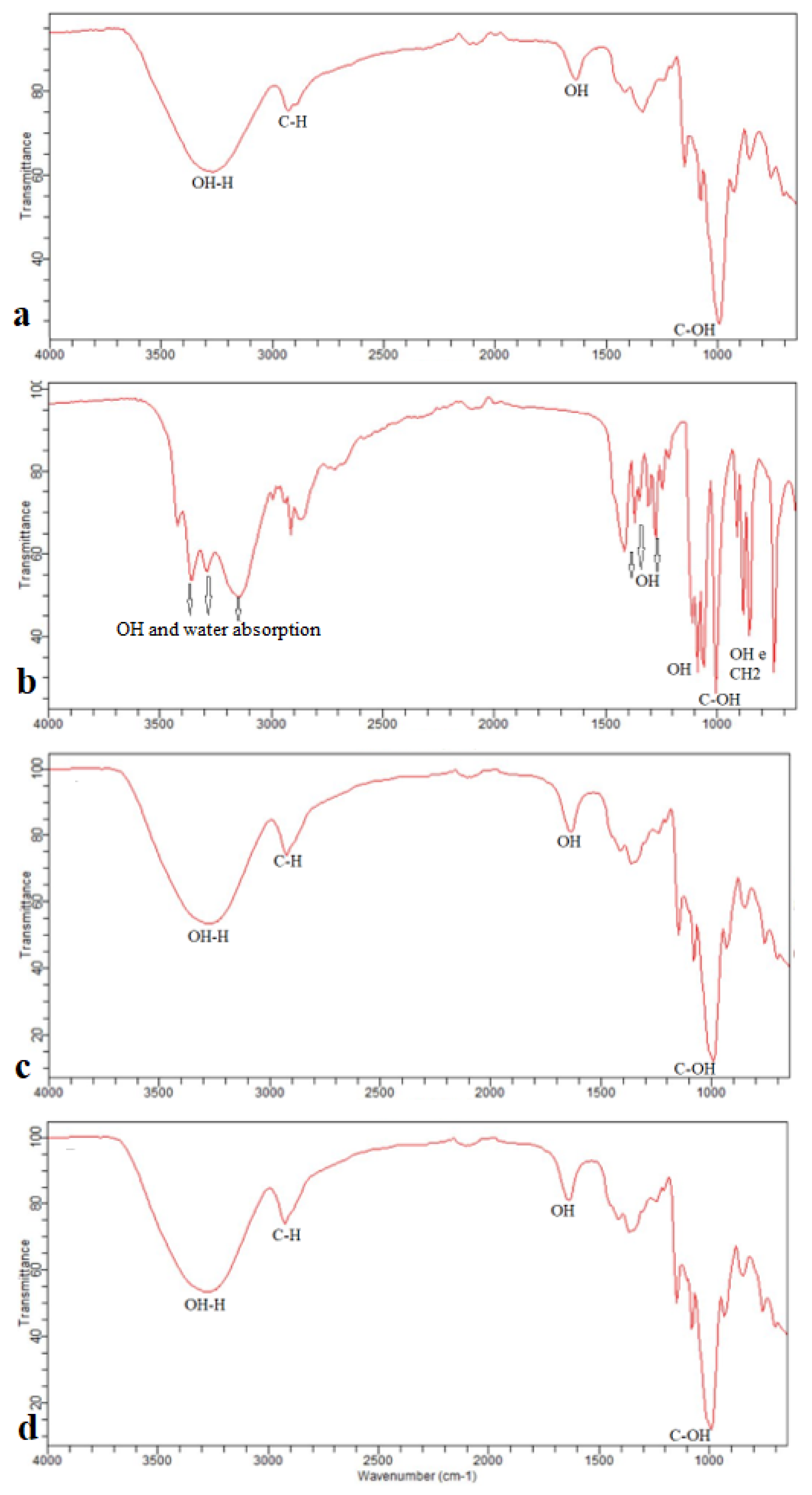

3.1.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy with Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR-ATR)

3.1.2. Thickness, WVP, Solubility and Mechanical Properties

3.2. Monitoring the Stability of Black Pepper Seeds

3.2.1. Microbiological Analysis

3.2.2. Color

3.2.3. Apparent and Real Specific Gravity and Weight of a Thousand Seeds

3.2.4. Moisture Content, Water Activity (aw), Porosity, and Mass Loss

| Treatment | ||||

| CP | RP | CP | RP | |

| ST | Moisture (%) | aw (dimensionless) | ||

| 1º | 6.44±0.05bE | 9.72±0.02aF | 0.37±0.00bH | 0.57±0.00aD |

| 2º | 8.30±0.00bD | 10.95±0.02aBC | 0.44±0.00bG | 0.57±0.00aD |

| 3º | 10.94±0.04bA | 12.00±0.15aA | 0.49±0.00aF | 0.52±0.00aE |

| 4º | 9.69±0.34aC | 10.05±0.11aEF | 0.54±0.01aE | 0.52±0.00aE |

| 5º | 10.73±0.00bAB | 11.04±0.07aB | 0.58±0.01aD | 0.59±0.01aC |

| 6º | 10.36±0.08bB | 11.15±0.09aB | 0.60±0.00aC | 0.60±0.01aC |

| 7º | 9.76±0.29aC | 10.39±0.09aDE | 0.62±0.00aB | 0.61±0.00aB |

| 8º | 10.41±0.08aB | 10.61±0.41aCD | 0.65±0.00aA | 0.65±0.00aA |

| PC | PR | PC | PR | |

| ST | Porosidade (%) | Perda de massa (%) | ||

| 1º | 45.36±0.72aBC | 48.61±2.72aA | - | - |

| 2º | 50.99±0.90aA | 48.80±2.03aA | -5.26±0.01bF | 11.98±0.02aA |

| 3º | 45.46±0.60aBC | 47.61±0.99aA | -5.35±0.01bE | 11.93±0.04aA |

| 4º | 48.94±2.93aAB | 47.16±2.08aA | -5.68±0.03bD | 11.69±0.04aB |

| 5º | 47.41±2.75aABC | 44.64±0.31aA | -6.42±0.03bA | 11.05±0.03aD |

| 6º | 44.38±0.86aC | 46.88±0.06aA | -6.20±0.00bB | 11.29±0.01aC |

| 7º | 47.36±1.62aABC | 48.24±3.16aA | -6.45±0.04bA | 11.19±0.01aCD |

| 8º | 47.75±1.14aABC | 47.88±3.43aA | -6.01±0.01bC | 11.69±0.18aB |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pereira, G.V.S.; Pereira, G.V.S.; Neves, E.M.P.X.; Rego, J.A.R.; Brasil, D.S.B.; Lourenço, L.F.H.; Joele, M.R.S.P. Glycerol and fatty acid influences on the rheological and technological properties of composite films from residues of Cynoscion acoupa. Food Bioscience 2020, 38, 100773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.V.S.; Pereira, G.V.S.; Neves, E.M.P.X.; Albuquerque, G.A.; Rego, J.A.R.; Cardoso, D.N.P.; Brasil, D.S.B.; Joele, M.R.S.P. Effect of the Mixture of Polymers on the Rheological and Technological Properties of Composite Films of Acoupa Weakfish (Cynoscion acoupa) and Cassava Starch (Manihot esculenta C.). Food and Bioprocess Technology 2021, 14, 1199–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, L.V.; Arias, C.I.L.F.; Maniglia, B.C.; Tadini, C.C. Starch-based biodegradable plastics: methods of production, challenges and future perspectives. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 38, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.V.S.; Pereira, G.V.S.; Neves, E.M.P.X.; Oliveira, L.C.; Pena, R.S.; Calado, V.; Lourenço, L.F.H. Biodegradable films from fishing industry waste: Technological properties and hygroscopic behavior. Journal of Composite Materials, 2021; 55, 4169–4181. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G.V.S.; Pereira, G.V.S.; Oliveira, L.C.; Cardoso, D.N.P.; Calado, V.; Lourenço, L.F.H. Rheological characterization and influence of different biodegradable and edible coatings on post-harvest quality of guava. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2021, 45, e15335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, E.M.P.X.; Pereira, G.V.S.; Pereira, G.V.S.; Vieira, L.L.; Lourenço, L.F.H. Effect of polymer mixture on bioplastic development from fish waste. Boletim do Instituto de Pesca 2019, 45(4), e518.

- Kaewprachu, P.; Osako, K.; Rungraeng, N.; Rawdkuen, S. Characterization of fish myofibrillar protein film incorporated with catechin-Kradon extract. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 107, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, M.I.L.; Batista-Menezes, D.; Rezende, S.C.; Santamaria-Echart, A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Vega-Baudrit, J.R. Biorefinery of Lignocellulosic and Marine Resources for Obtaining Active PVA/Chitosan/Phenol Films for Application in Intelligent Food Packaging. Polymers 2025, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, A.; Sanjay, M.R.; Suchart, S.; Jyotishkumar, P. Renewable and sustainable biobased materials: An assessment on biofibers, biofilms, biopolymers and biocomposites. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 258, 120978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peerzada, G.h.J.; Sinclair, B.J.; Perinbarajan, G.K.; Dutta, R.; Shekhawat, R.; Saikia, N.; Chidambaram, R.; Mossa, A.T. An overview on smart and active edible coatings: safety and regulations. Eur Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 1935–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barizão, C.L.; Crepaldi, M.I.; Junior, O.O.S.; Oliveira, A.C.; Martins, A.F.; Garcia, P.S.; Bonafé, E.G. Biodegradable films based on commercial κ-carrageenan and cassava starch to achieve low production costs. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 165, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colussi, R.; Pinto, V.Z.; El Halal, S.L.M.; Biduski, B.; Prietto, L.; Castilhos, D.D.; Dias, A.R.G. Acetylated rice starches films with different levels of amylose: Mechanical, water vapor barrier, thermal, and biodegradability properties. Food Chemistry 2017, 221, 1614–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongphan, P.; Panrong, T.; Harnkarnsujarit, N. Effect of different modified starches on physical, morphological, thermomechanical, barrier and biodegradation properties of cassava starch and polybutylene adipate terephthalate blend film. Food Packaging and Shelf Life, 2022, 32, 100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, T.S.; Jesus, A.L.T.; Schmiele, M.; Tribst, A.A.T.; Cristianini, M. High pressure processing (HPP) of pea starch: Effect on the gelatinization properties. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2017, 76, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.H.; Liang, C.W.; Chang, Y.H. Effect of starch source on gel properties of kappa-carrageenan-starch dispersions. Food Hydrocolloids 2016, 60, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhija, S.; Singh, S.; Riar, C.S. Analyzing the effect of whey protein concentrate and psyllium husk on various characteristics of biodegradable film from lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) rhizome starch. Food Hydrocolloids 2016, 60, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.G.A.; Silva, M.A.; Santos, L.O.; Beppu, M.M. Natural-based plasticizers and biopolymer films: a review. European Polymer Journal 2011, 47, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K.M.; Yoksan, R. Thermoplastic starch blown films with improved mechanical and barrier Properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 188(1), 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunduru, K.R.; Hogerat, R.; Ghosal, K.; Shaheen-Mualim, M.; Farah, S. Renewable polyol-based biodegradable polyesters as greener plastics for industrial applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 459, 141211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, K.; Sánchez-Leija, R.J.; Gross, R.A.; Linhardt, R.J. Review on the impact of polyols on the properties of Bio-Based polyesters. Polymers 2020, 12, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaeh, S.; Thongnuanchan, B.; Bueraheng, Y.; Das, A.; Kaus, N.H.M.; Wießner, S. The utilization of glycerol and xylitol in bio-based vitrimer-like elastomer: Toward more environmentally friendly recyclable and thermally healable cross-linked rubber. European Polymer Journal 2023, 198(17), 112422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Santos, J.; Valls, C.; Cusola, O.; Roncero, M.B. Improving filmogenic and barrier properties of nanocellulose films by addition of biodegradable plasticizers. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng 2021, 9, 9647–9660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, J.; Meervelt, L.V.; Parkin, S. Classroom experiments with artificial sweeteners: growing single crystals and simple calorimetry. Acta Crystallographica Section E Crystallographic Communications 2022, 8(9), 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culbert, S.J.; Wang, Y.M.; Fritsche, H.A.; Carr, D.; Lantin, E.; van, E.Y.S.J. Oral xylitol in American adults. Nutrition Research 1986, 6, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRASIL. Ministério Da Saúde, Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária - ANVISA. Resolução da Diretoria Colegiada - RDC Nº 239, DE 26 DE JULHO DE 2018 da ANVISA. Estabelece os aditivos alimentares e coadjuvantes de tecnologia autorizados para uso em suplementos alimentares. Diário Oficial. Brasília, DF. 2018.

- Hassan, B.; Chatha, S.A.S.; Hussain, A.I.; Zia, K.M.; Akhtar, N. Recent advances on polysaccharides, lipids and protein based edible films and coatings: a review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 109, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maherani, B.; Harich, M.; Salmieri, S.; Lacroix, M. Antibacterial properties of combined non-thermal treatments based on bioactive edible coating, ozonation, and gamma irradiation on ready-to-eat frozen green peppers: evaluation of their freshness and sensory qualities. Eur. Food Res. Technol, 2019, 245, 1095–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvano, F.; Corona, O.; Pham, P.L.; Cinquanta, L.; Pollon, M.; Bambina, P.; Farina, V.; Albanese, D. Effect of alginate-based coating charged with hydroxyapatite and quercetin on colour, firmness, sugars and volatile compounds of fresh cut papaya during cold storage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2022, 248, 2833–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podshivalov, A.; Zakharova, M.; Glazacheva, E.; Uspenskaya, M. Gelatin/potato starch edible biocomposite films: Correlation between morphology and physical properties. Carbohydrate Polymers 2017, 157, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogendrarajah, P.; Deschuyffeleer, N.; Jacxsens, L.; Sneyers, P.J.; Maene, P.; Saeger, S.; Devlieghere, F.; Meulenaer, B. Mycological quality and mycotoxin contamination of Sri Lankan peppers (Piper nigrum L.) and subsequent exposure assessment. Food Control 2014, 41, 219-230.

- Abukawsar, M.M.; Saleh-e-In, M.M.; Ahsan, M.A.; Rahim, M.M.; Bhuiyan, M.N.H.; Roy, S.K.; Ghosh, A.; Naher, S. Chemical, pharmacological and nutritional quality assessment of black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) seed cultivars, J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, e12590.

- Rehman, A.; Mehmood, M.H.; Haneef, M.; Gilani, A.H.; Ilyas, M.; Siddiqui, B.S.; Ahmed, M. Potential of black pepper as a functional food for treatment of airways disorders, J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasleem, F.; Azhar, I.; Ali, S.N.; Perveen, S.; Mahmood, Z.A. Analgesic and antiinflammatory activities of Piper nigrum L. , Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014, 7, S461–S468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G. V. S. , Pereira, G. V. S., Araujo, E. F. de, Xavier, E. M. P., Joele, M. R. S. P., & Lourenço, L. de F. H. (2019a). Optimized process to produce biodegradable films with myofibrillar proteins from fish byproducts. de F. H. ( 21, 100364.

- Fan, R.; Qin, X.W.; Hu, R.S.; Hu, L.S.; Wu, B.D.; Hao, C.Y. Studies on the chemical and flavour qualities of white pepper (Piper nigrum L.) derived from grafted and non-grafted plants. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 2601–2610.

- Öz Pereira ogul, F.; Küley, E.; Küley, F.; Kulawik, P.; Rocha, J.M. Impact of sumac, cumin, black pepper and red pepper extracts in the development of foodborne pathogens and formation of biogenic amines. Eur Food Res Technol 2022, 248, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar]

- Rego, J.A.R.; Brasil, C.M.L.; Brasil, D.S.B.; Cruz, J.N.; Costa, C.M.L.; Santana, E.B.; Furtado, S.V.; Lopes, A.S. Characterization and Evaluation of Filmogenic, Polymeric, and Biofilm Suspension Properties of Cassava Starch Base (Manihot esculenta Crantz) Plasticized with Polyols. Brazilian Journal of Development 2020, 6, 50417–50442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G. V. S., Pereira, G. V. S., Neves, E. M. P. X., Joele, M. R. S. P., Lima, C. L. S., & Lourenço, L. de F. H. (2019b). Effect of adding fatty acids and surfactant on the functional properties of biodegradable films prepared with myofibrillar proteins from acoupa weakfish (Cynoscion acoupa). Food Science and Technology, 39(1), 287–294.

- Zavareze, E.R.; Halal, S.L.M.; Silva, R.M.; Dias, A.R.G.; Prentice-Hernández, C. Mechanical, barrier and morphological properties of biodegradable films based on muscle and waste proteins from the whitemouth croaker (Micropogonias Furnieri). Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2014, 38(4), 1973–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfat, Y.A.; Benjakul, S.; Prodpran, T.; Osako, K. Development and characterisation of blend films based on fish protein isolate and fish skin gelatin. Food Hydrocolloids 2014, 39, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontard, N.; Duchez, C.; Cuq, J.L.; Guilbert, S. Edible composite films of wheat gluten and lipids: Water vapour permeability and other physical properties. International Journal of Food Science & Technology.

- Limpan, N.; Prodpran, T.; Benjakul, S.; Prasarpran, S. Influences of degree of hydrolysis and molecular Weight of poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) on properties of fish myofibrillar protein/PVA blend films. Food Hydrocolloids 2012, 29(1), 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salfinger, Y.; Tortorello, L.M. Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Foods, 5º ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- BRASIL. Ministério Da Saúde, Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária - ANVISA. Instrução Normativa - IN Nº 161, DE 1º DE JULHO DE 2022 da ANVISA. Estabelece os padrões microbiológicos dos alimentos. Diário Oficial. Brasília, DF. 2022.

- AOAC. Association of Official Analytical Chemists International. Official Methods of Analysis, 1999.

- Paul, W.; Clyde, O. Analytical methods in fine particle technology. Micromeritics Instrument Corp.: Norcross, Ga.,1997; pp. 301.

- McCABE, W.L.; Smith, J.C.; Harriot, T.P. Unit Operations of Chemical Engineering, 5º ed.; McGraw-Hill International Editions: Nova York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- BRASIL. Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. Regras para análise de sementes. Secretaria de Defesa Agropecuária. – Brasília: Mapa/ACS, 2009, p. 399.

- Martucci, J.F.; Ruseckaite, R.A. Biodegradation behavior of three-layer sheets based on gelatin and poly (lactic acid) buried under indoor soil conditions. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2015, 116, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewprachu, P.; Osako, K.; Rungraeng, N.; Rawdkuen, S. Characterization of fish myofibrillar protein film incorporated with catechin-Kradon extract. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 107, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriner, R.L.; Fuson, R.C. Identificação Sistemática de Compostos Orgânicos. Publisher Guanabara Dois S.A.: Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil, 1993.

- Cao, C.; Shen, M.; Hu, J.; Qi, J.; Xie, P.; Zhou, Y. Comparative study on the structure-properties relationships of native and debranched rice starch. CyTA - J Food.

- Monroy, Y.; Cabezas, D.M.; Rivero, S.; García, M.A. Structural analysis and adhesive capacity of cassava starch modified with NaOH:urea mixtures. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 2023, 126, 103470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kong, W.; Cai, X. Solvent-free preparation and performance of novel xylitol based solid-solid phase change materials for thermal energy storage, Energy and Building, 2018, 158, 37-42.

- Rusianto, T.; Yuniwati, M.; Wibowo, H.; Akrowiah, L. Biodegradable plastic from Taro tuber (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) and Chitosan. Saudi Journal of Engineering Technology 2019, 4, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Júnior, J.E.M.; Rocha, M.V.P. Development of a purification process via crystallization of xylitol produced for bioprocess using a hemicellulosic hydrolysate from the cashew apple bagasse as feedstock. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering 2021, 44, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Nickerson, M.T. Effect of plasticizer-type and genipin on the mechanical, optical, and water vapor barrier properties of canola protein isolate-based edible films. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2014, 238, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadsai, S.; Janmanee, R.; Sam-Ang, P.; Nuanchawee, Y.; Rakitikul, W.; Mankhong, W.; Likittrakulwong, W.; Ninjiaranai, P. Influence of Cross-linking Concentration on the Properties of Biodegradable Modified Cassava Starch-Based Films for Packaging Applications, Polymers 2024, 16, 1647.

- Chantawee, K. ; Riyajan. S.A. Effect of glycerol on the physical properties of carboxylated styrene-butadiene rubber/cassava starch blend films. Journal of Polymers and the Environment.

- Adhikari, B.; Chaudhary, D.S.; Clerfeuille, E. Effect of plasticisers in the moisture migration behaviour of low-amylose starch films during drying. Drying Technology 2010, 28, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscat, D.; Adhikari, B.; Adhikari, R.; Chaudhary, D.S. Comparative study of film forming behaviour of low and high amylose starches using glycerol and xylitol as plasticizers. Journal of Food Engineering 2012, 109(2), 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizam, N.H.M.; Rawi, N.F.M.; Ramle, S.F.M.; Aziz, A.A.; Abdullah, C.K.; Rashedic, A.; Kassim, M.H.M. Physical, thermal, mechanical, antimicrobial and physicochemical properties of starch based film containing aloe vera: a review. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021, 15, 1572–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Velazquez, G.; Gutierrez, M.C.; Rangel-Vargas, E.; Castro-Rosas, J. Aguirre-Loredo, R.Y. Effect of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical properties of biodegradable starch films. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 239, 122027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellá, M.C.G.; Silva, O.A.; Pellá, M.G.; Beneton, A.G.; Caetano, J.; Simões, M.R.; Dragunski, D.C. Effect of gelatin and casein additions on starch edible biodegradable films for fruit surface coating. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 25764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.C.; Benze, R.; Ferrão, E.S.; Ditchfield, C.; Coelho, A.C.V.; Tadini, C.C. Cassava starch biodegradable films: influence of glycerol and clay nanoparticles content on tensile and barrier properties and glass transition temperature. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewprachu, P.; Osako, K.; Tongdeesoontorn, W.; Rawdkuen, S. The effects of microbial transglutaminase on the properties of fish myofibrillar protein film. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2017, 12, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Dai, B.; Hu, S.; Hong, R.; Xie, H.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, G. Preparation, reinforcement and properties of thermoplastic starch film by film blowing. Food Hydrocolloids 2020, 108, 106006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junlapong, K.; Boonsuk, P.; Chaibundit, C.; Chantarak, S. Highly water resistant cassava starch/poly (vinyl alcohol) films. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 137, 521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Forssell, P.; Mikkilä, J.; Suortti, T.; Seppälä, J.; Poutanen, K. Plasticization of barley starch with glycerol and water. Journal of Macromolecular Science: Pure and Applied Chemistry.

- Enrione, J.I.; Hill, S.E.; Mitchell, J.R. Sorption and Diffusional Studies of Extruded Waxy Maize Starch-Glycerol Systems. Starch 2007, 59(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, S.E.; Moberg, K.; Amin, K.N.; Wright, M.; Newkirk, J.J.; Ponder, M.A.; Acuff, G.R.; Dickson, J.S. Processes to preserve spice and herb quality and sensory integrity during pathogen inactivation. Journal of Food Science 2017, 82(5), 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertwig, C.; Reineke, K.; Ehlbeck, J.; Knorr, D.; Schlüter, O. Decontamination of whole black pepper using different cold atmospheric pressure plasma applications. Food Control. 2015, 55, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, T.M.F.; Pcolo, M. P.; Maradini Filho, A. M.; Silva, M. B.; Oliveira, M. V.; Santos Junior, A. C.; Martins, L. F.; & Santos, Y.I.C. ; & Santos, Y.I.C. Qualidade de pimenta-do-reino obtida de propriedades rurais do norte do Espírito Santo. Avanços em Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mokrzycki, W.S.; Tatol, M. Colour difference E-A survey. Machine Graphics and Vision 2011, 20(4), 383–411. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Verma, T.; Irmak, S.; Subbiah, J. Effect of storage on microbial reductions after gaseous chlorine dioxide treatment of black peppercorns, cumin seeds, and dried basil leaves. Food Control 2023, 148, 109627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.; Junqueira, V.C.A.; Silveira, N.F.A.; Taniwaki, M.H.; Gomes, R.A.R.; Okazaki, M.M.; Iamanaka, B.T. Manual de Métodos de Análise Microbiológica de Alimentos e água, 6º ed.; Editora Blucher: São Paulo, SP, Brasil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mata, M.E.R.M.C.; Duarte, M.E.M.; Duarte, M.E.M. Porosidade intergranular de produtos agrícolas. Revista Brasileira de Produtos Agroindustriais 2002, 4(1), 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.C.; Costa, E.; Cardoso, E.D.; Binotti, F.F.S.; Jorge, M.H. Propriedades físicas de sementes de baru em função da secagem. Revista de Agricultura Neotropical 2014, 1(1), 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.Á.; Guimarães, R.M.; Rosa, S.D.V.F. Processamento de sementes pós-colheita. Informe Agropecuário.

- Murmu, S.B.; Mishra, H.N. Optimization of the arabic gum based edible coating formulations with sodium caseinate and tulsi extract for guava. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2017, 80, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Thickness (mm) | WVP (g.mm/m2.d.kPa) | Solubility (%) | TS (MPa) | E (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 0.100±0.00a | 2.71±0.13b | 3.05±0.11b | 22.43±0,31a | 8.27±00.31b |

| CX | 0.101±0.00a | 10.84±0.18a | 24.23±0.64a | 4.17±0,18b | 52.67±1.88a |

| Microorganisms | CP | RP |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli NMP/g | Absence | Absence |

| Salmonella sp/25g | Absence | Absence |

| Molds and yeast (CFU/g) | 1.6 x 103 | 1.4 x 103 |

| Treatments | ||||

| CP | RP | CP | RP | |

| ST | L* | a* | ||

| 1º | 26.34±0.26aB | 21.38±0.28bD | 0.93±0.07aBC | 0.93±0.08aC |

| 2º | 19.66±0.54aD | 18.84±0.22aE | 0.38±0.03bD | 0.74±0.02aD |

| 3º | 25.77±0.95aB | 25.35±0.43aA | 0.94±0.07bBC | 1.93±0.04aA |

| 4º | 26.29±0.71aB | 23.45±0.41bB | 1.04±0.14bAB | 1.32±0.08aB |

| 5º | 24.06±0.91aC | 22.30±0.57bC | 0.83±0.05bC | 1.26±0.19aB |

| 6º | 28.39±0.85aA | 21.49±0.93bCD | 1.01±0.02aAB | 1.00±0.09aC |

| 7º | 25.49±0.68aB | 22.06±0.41bCD | 1.08±0.08bA | 1.86±0.07aA |

| ST | b* | C* | ||

| 1º | 10.67±0.33aAB | 11.03±0.10aBC | 11.66±0.27aA | 10.43±0.66bBC |

| 2º | 9.85±0.30bBC | 10.65±0.25aC | 10.19±0.27aBC | 10.08±0.33aC |

| 3º | 10.19±0.63bABC | 11.74±0.32aAB | 11.15±0.47aAB | 11.02±0.36aAB |

| 4º | 11.11±0.81aA | 11.74±0.79aAB | 11.37±0.90aA | 11.08±0.17aAB |

| 5º | 9.63±0.07bC | 10.45±0.41aC | 9.74±0.15aC | 9.97±0.16aC |

| 6º | 10.46±0.82aABC | 10.25±0.40bC | 11.91±0.88aA | 10.28±0.42bBC |

| 7º | 11.08±0.18bA | 12.34±0.63aA | 11.68±0.48aA | 11.58±0.87aA |

| PC | PR | PC | PR | |

| ST | hº | ΔE | ||

| 1º | 84.79±0.71aB | 86.54±1.26aA | - | - |

| 2º | 86.73±0.57aA | 86.96±0.95aA | 6.59±0.14aA | 2.86±0.05bB |

| 3º | 82.62±0.25aD | 83.44±0.45aBC | 1.35±0.63bD | 3.76±0.36aA |

| 4º | 82.98±0.72aCD | 82.60±0.48aCD | 0.76±0.06bE | 2.60±0.27aB |

| 5º | 84.15±0.61aBC | 84.12±1.13aB | 2.04±0.07aC | 0.97±0.06bD |

| 6º | 84.86±0.66aB | 86.20±0.64aA | 2.71±0.22aB | 1.05±0.06bD |

| 7º | 81.30±1.14aE | 81.74±0.24aD | 1.36±0.00bD | 1.52±0.00aC |

| Treatments | ||||

| CP | RP | CP | RP | |

| ST | Apparent specific gravity (g/ml) | Actual specific gravity (g/ml) | ||

| 1º | 0.53±0.00aC | 0.53±0.00aB | 0.97±0.00bC | 1.08±0.02aA |

| 2º | 0.53±0.00aBC | 0.53±0.00aAB | 1.09±0.01aA | 1.04±0.02aAB |

| 3º | 0.54±0.00aAB | 0.53±0.00bAB | 1.01±0.03aABC | 1.01±0.02aAB |

| 4º | 0.54±0.00aAB | 0.54±0.00aA | 1.05±0.04aAB | 1.02±0.03aAB |

| 5º | 0.54±0.00aAB | 0.54±0.00aAB | 1.02±0.04aABC | 0.97±0.02aB |

| 6º | 0.54±0.00aA | 0.54±0.00aAB | 0.97±0.01aBC | 1.01±0.00aAB |

| 7º | 0.53±0.00aC | 0.53±0.00aB | 1.00±0.02aBC | 1.02±0.06aAB |

| 8º | 0.54±0.00aAB | 0.53±0.00aAB | 1.03±0.02aABC | 1.02±0.05aAB |

| PC | PR | |||

| ST | Weight of a thousand seeds (g) | |||

| 1º | 43.63±0.23bA | 46.96±0.20aA | - | - |

| 2º | 43.14±0.24bA | 44.84±0.20aBC | - | - |

| 3º | 42.98±0.11aA | 43.80±0.15aCD | - | - |

| 4º | 41.72±0.14bB | 44.04±0.14aCD | - | - |

| 5º | 42.83±0.17aAB | 44.14±0.24aCD | - | - |

| 6º | 43.52±0.17bA | 45.53±0.20aB | - | - |

| 7º | 43.62±0.18bA | 45.57±0.25aB | - | - |

| 8º | 43.33±0.20aA | 43.42±0.12aD | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).