Submitted:

20 November 2023

Posted:

21 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of samples and solutions

2.2. Experimental design of pretreatment process.

2.3. Experimental procedure

2.4. Analytical Methods

Water content

Oil Content

Determination of Shrinkage

Measurement of bulk density

Color

Scanning electron microscopy

Effective moisture diffusion coefficient (Deff)

Texture determination

Modeling moisture loss and oil uptake

| Number | Model equation | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | O=a.t2+b.t+c | [48] |

| 2 | O=a.tb | [48] |

| 3 | O=a.exp(-b.t)+c | [52] |

| 4 | O=(1+t)/(a.t+b) | [52] |

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Result and discussion

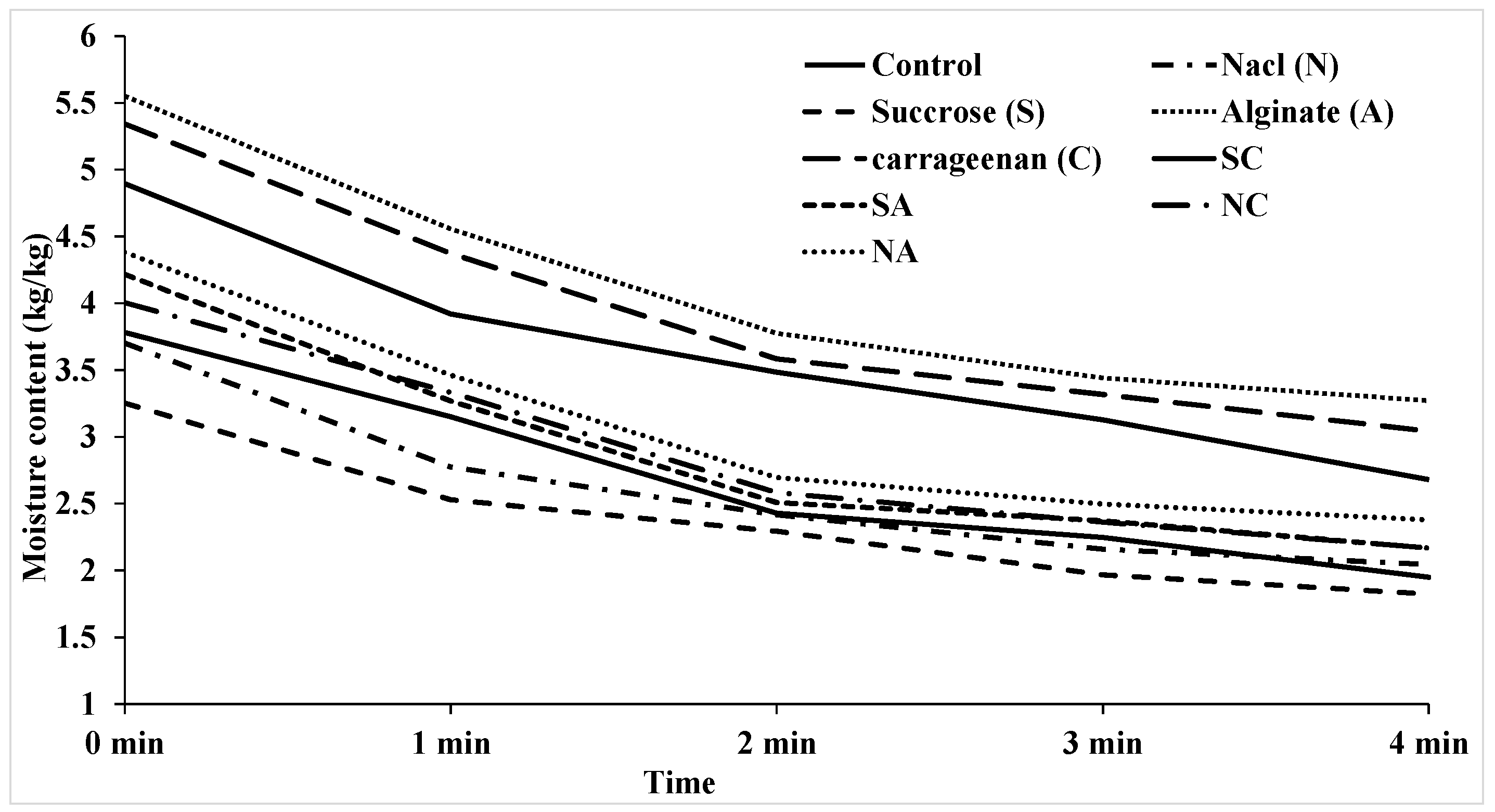

3.1 Moisture content

3.2. Effective diffusion coefficient of moisture (Deff)

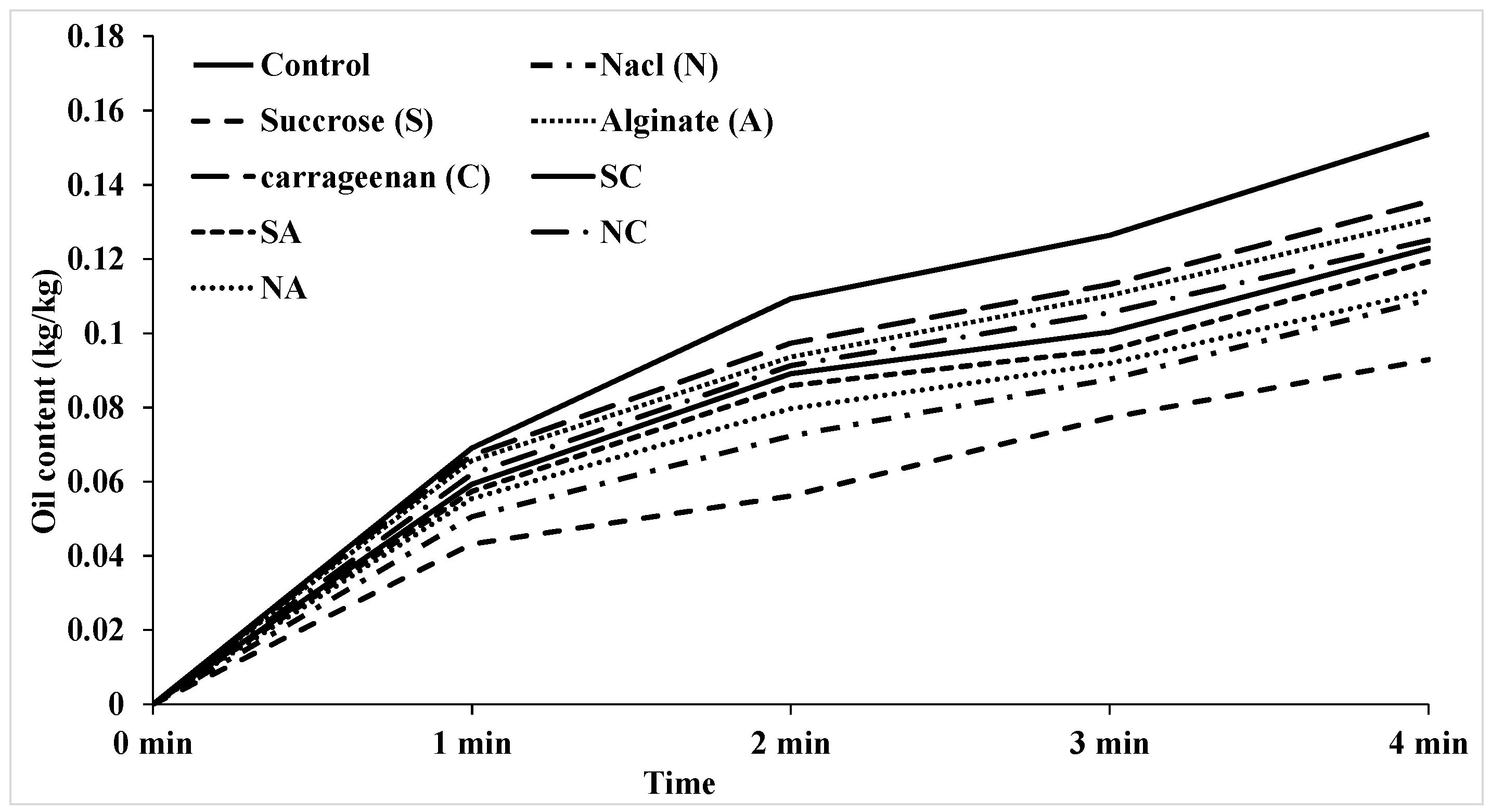

3.3. Oil uptake

3.4. Shrinkage

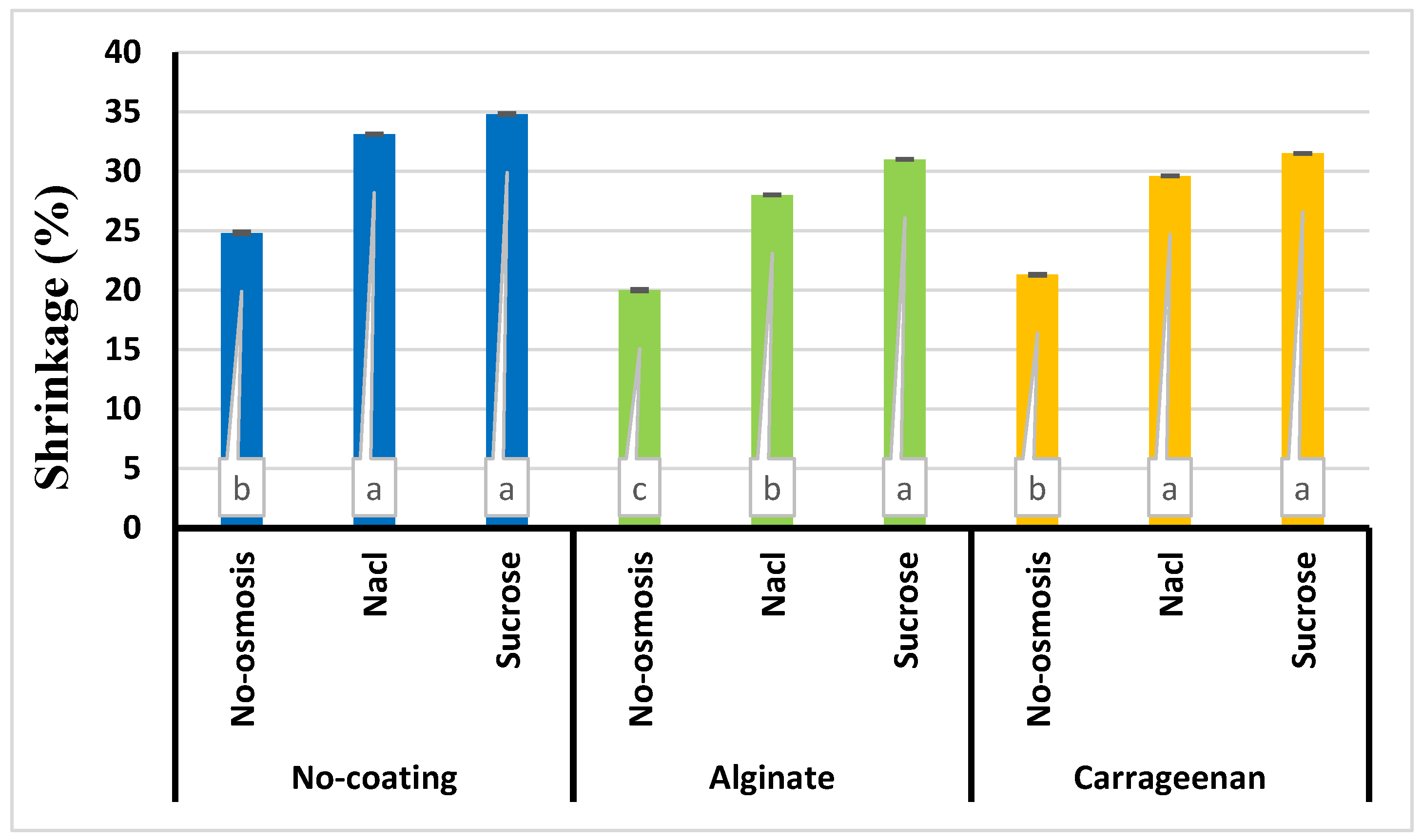

3.5. Apparent density

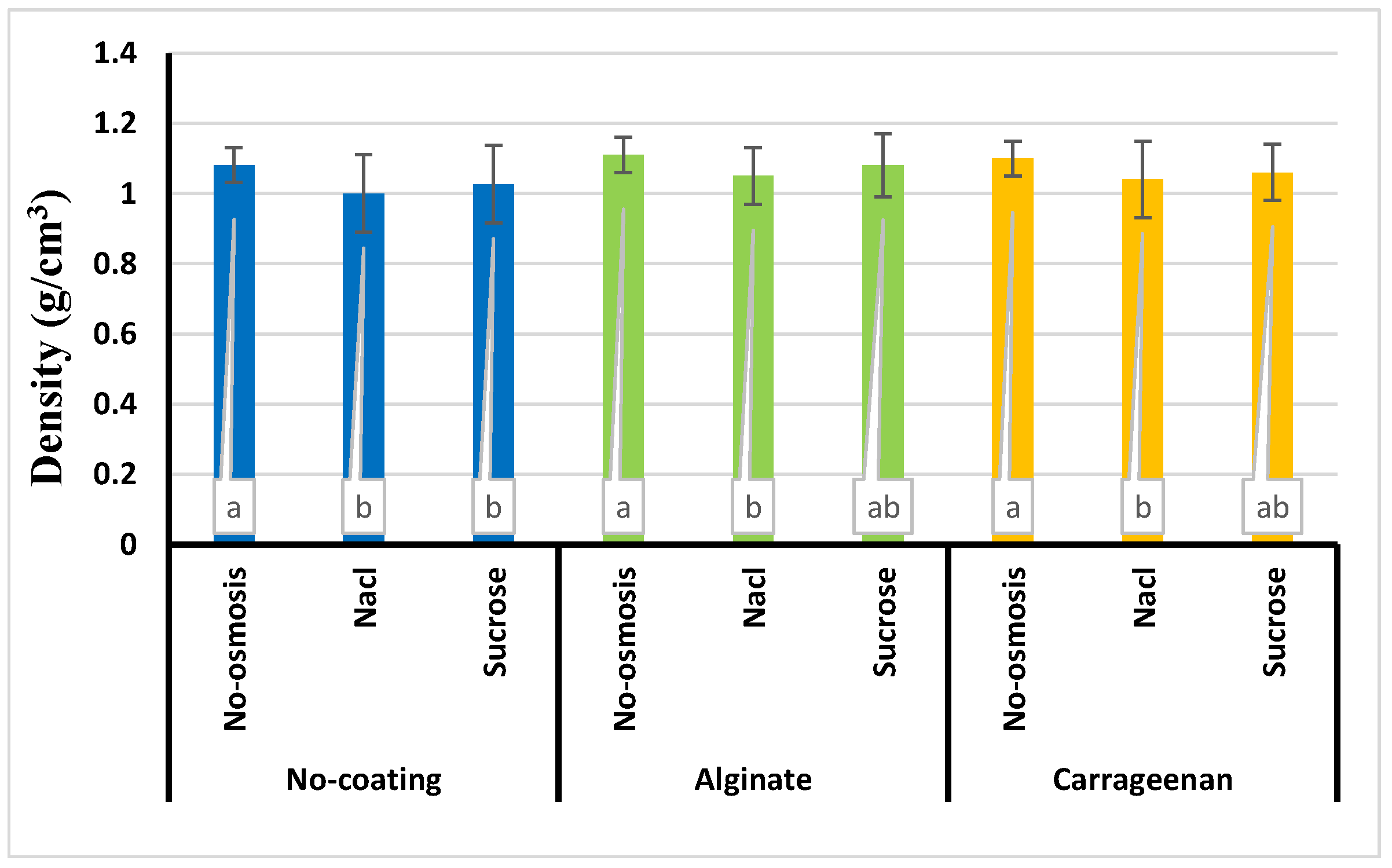

3.6. SEM

3.7. Breaking force

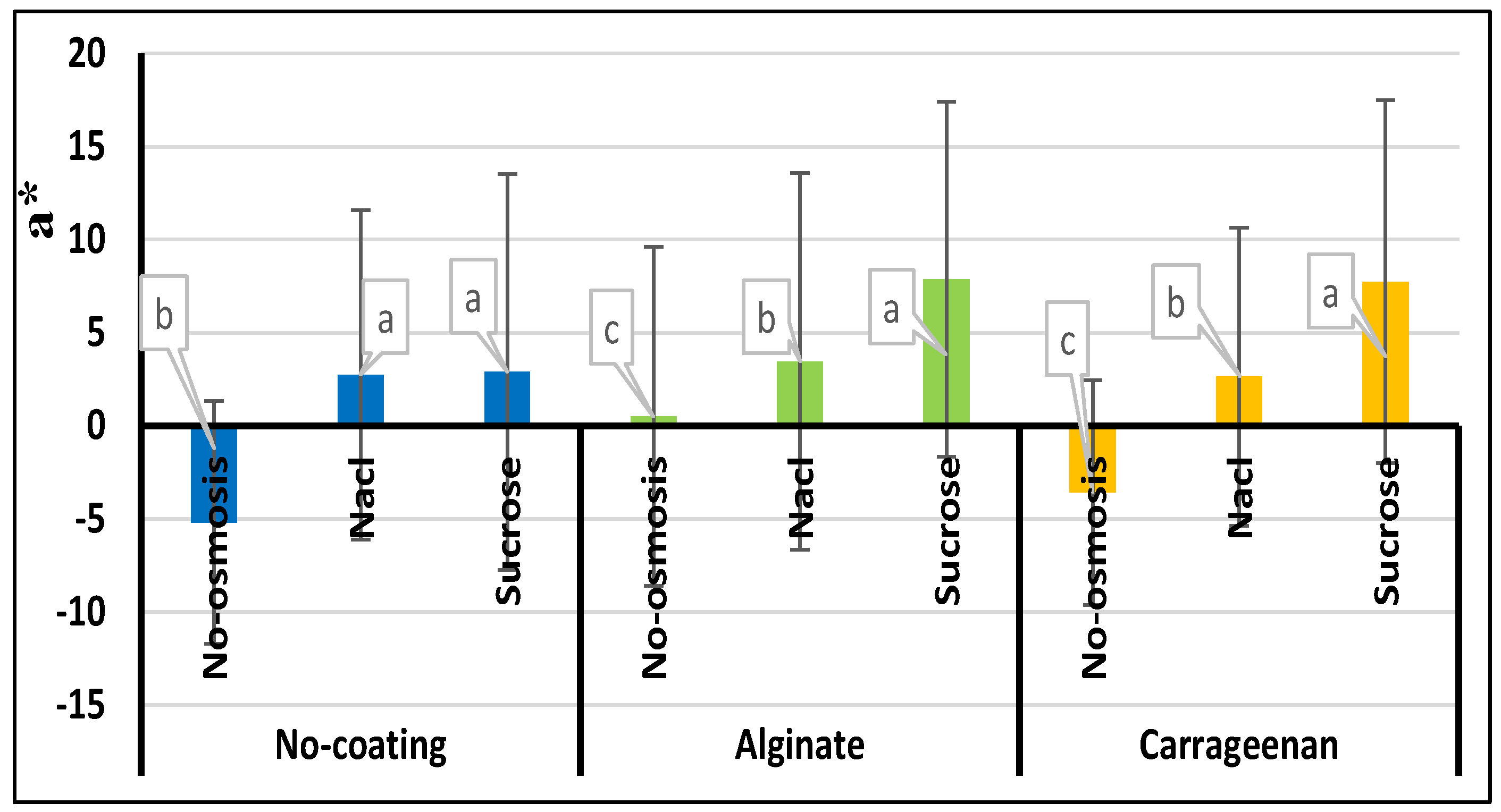

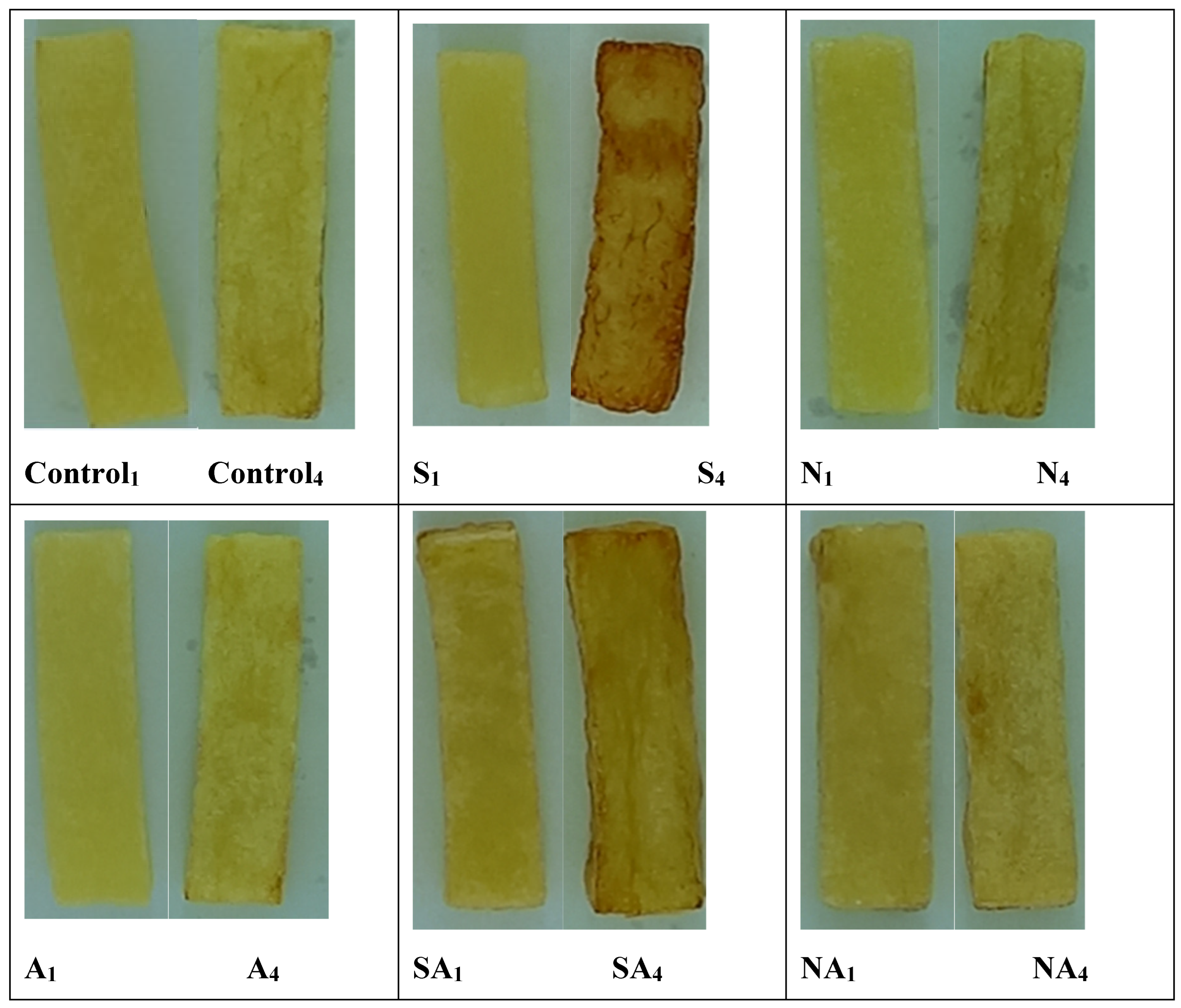

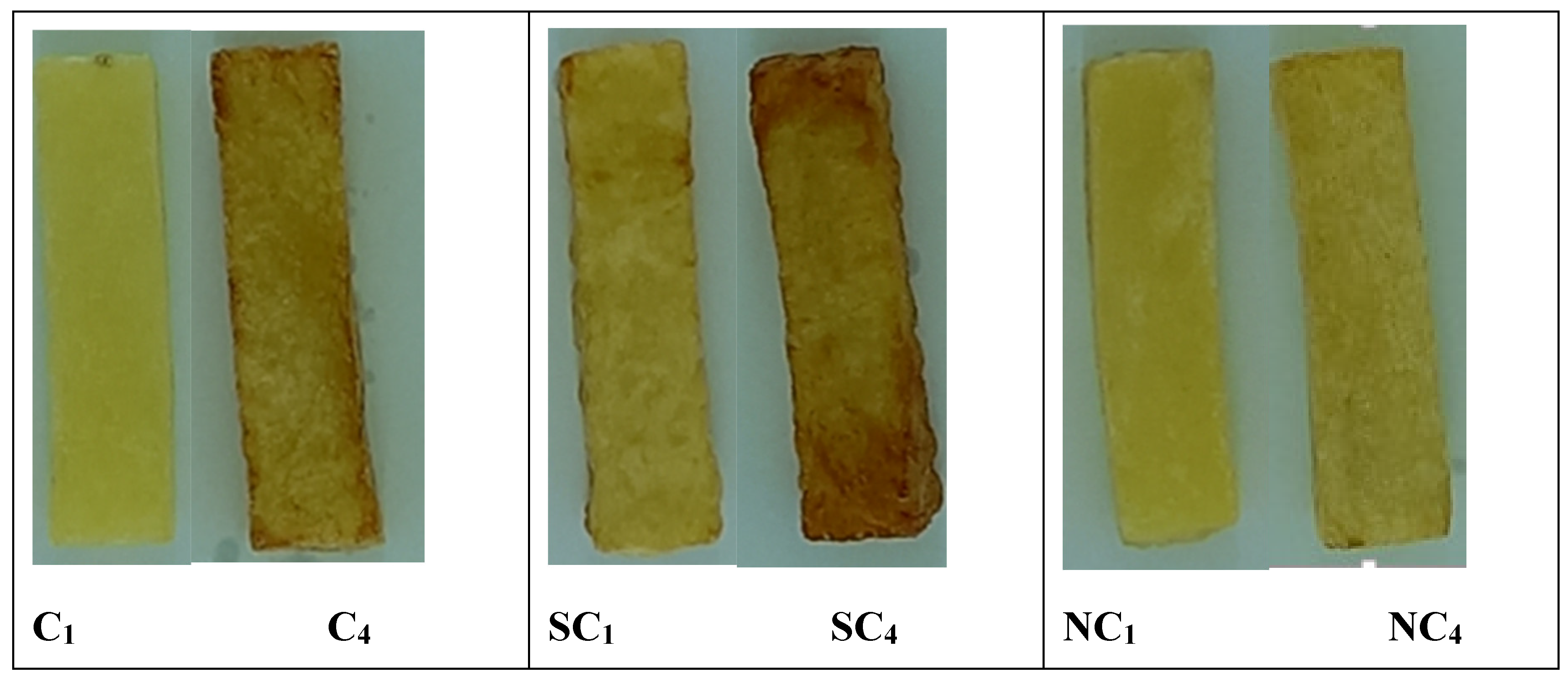

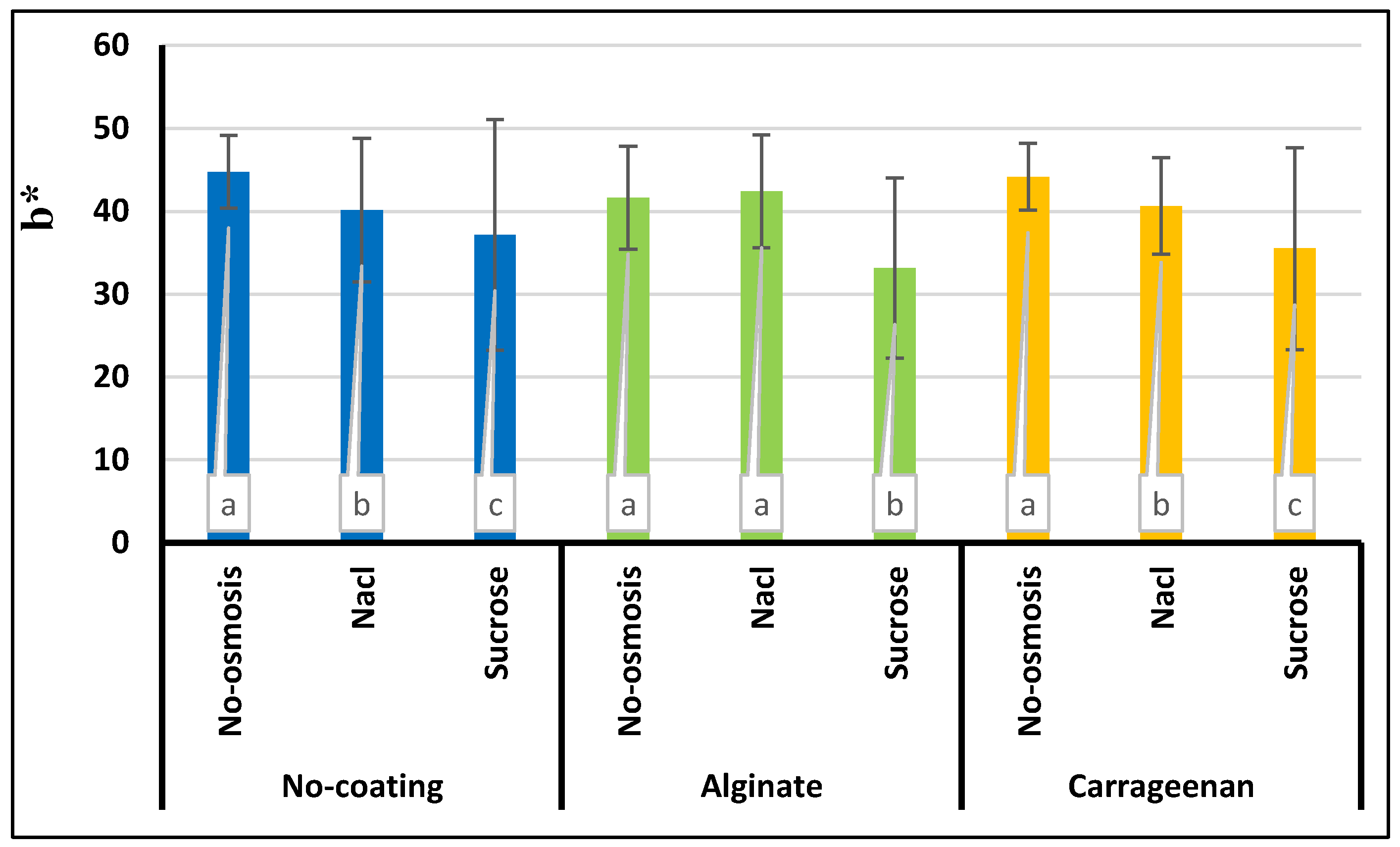

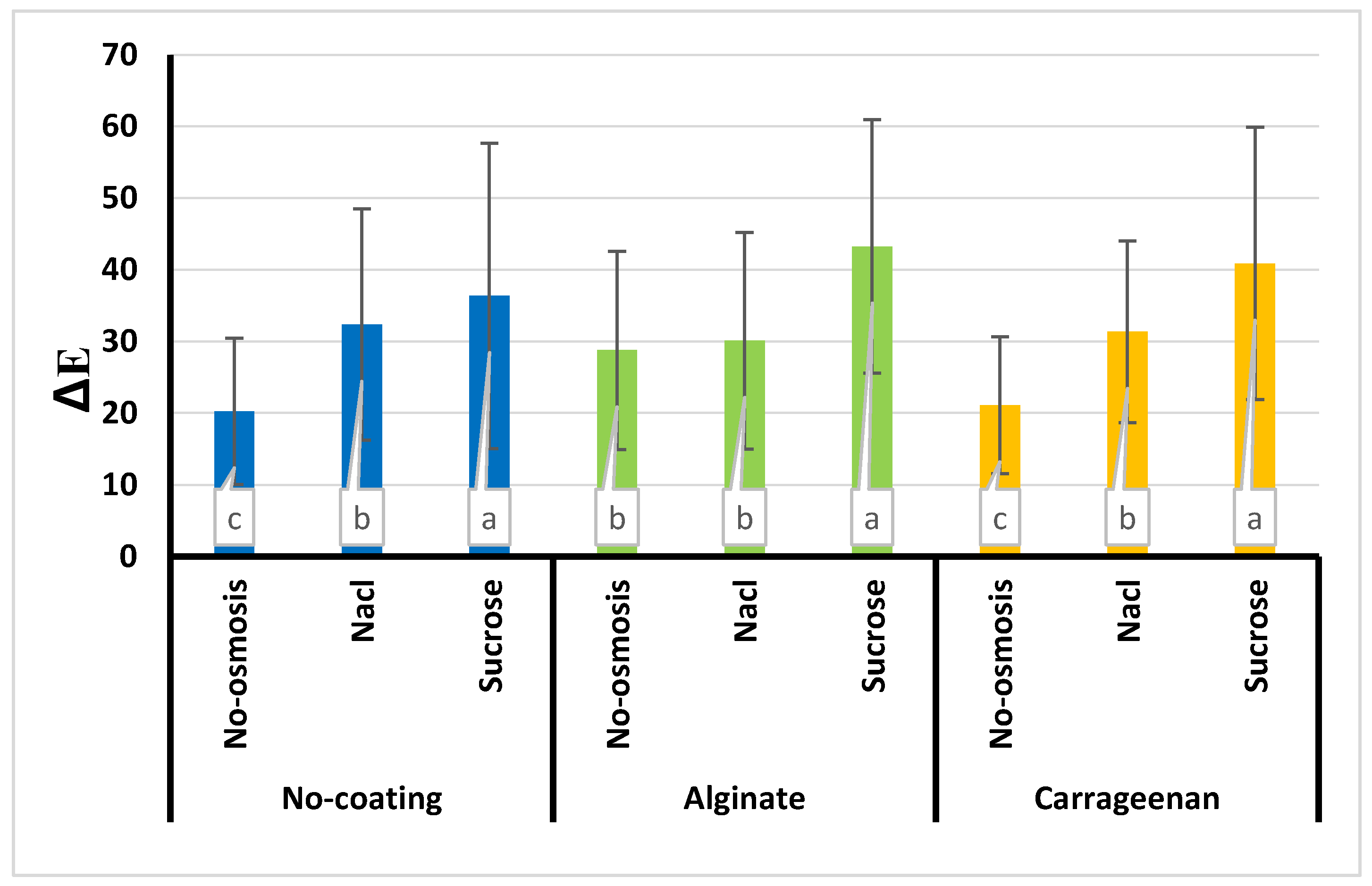

3.8. Color

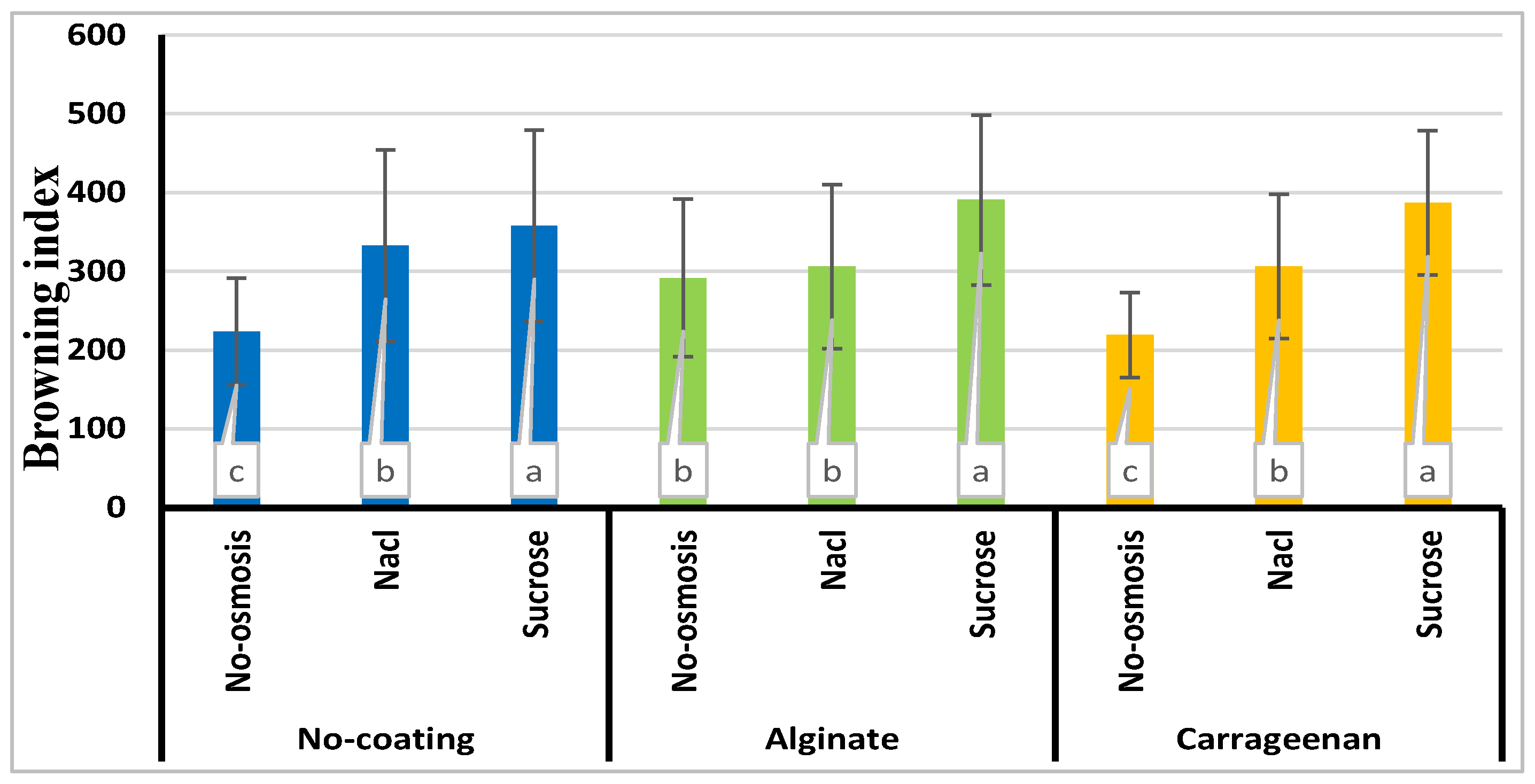

3.9. Browning index

3.10. Modeling

4. Conclusions

References

- Kurek, M.; et al. Edible coatings minimize fat uptake in deep fat fried products: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 71, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teruel, M.R.; et al. Use of vacuum-frying in chicken nugget processing. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2014, 26, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; et al. Reduction of oil uptake with osmotic dehydration and coating pre-treatment in microwave-assisted vacuum fried potato chips. Food Biosci. 2021, 39, 100825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokida, M.K.; et al. Effect of osmotic dedydration pretreatment on quality of french fries. J. Food Eng. 2001, 49, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomkun, P.; Innawong, B. Effect of pre-treatment processes on physicochemical aspects of vacuum-fried banana chips. Food Process Preserv. 2018, 42, e13687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunger, A.; et al. (2003). NaCl soaking treatment for improving the quality of French-fried potatoes. Food Res. Int. 2003, 36, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos-Marin, I.; et al. Influence of osmotic pretreatments on the quality properties of deep-fat fried green plantain. J. Food Sc. Technol. 2020, 57, 2619–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piyalungka, P.; et al. Effects of osmotic pretreatment and frying conditions on quality and storage stability of vacuum-fried pumpkin chips. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 2963–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananey-Obiri, D.; et al. Application of protein-based edible coatings for fat uptake reduction in deep-fat fried foods with an emphasis on muscle food proteins. Trends Food Sci.Technol. 2018, 80, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; et al. Oil absorption of potato slices pre-dried by three kinds of methods. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2018, 120, 1700382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, X.l.; et al. Dielectric properties of carrots affected by ultrasound treatment in water and oil medium simulated systems. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 56, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sothornvit, R. Edible coating and post-frying centrifuge step effect on quality of vacuum-fried banana chips. J. Food Eng. 2011, 107, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; et al. Effect of guar gum with glycerol coating on the properties and oil absorption of fried potato chips. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 54, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurtys, O. Food hydrocolloid edible films and coatings. Nova Science Publishers: New York, USA, 2010.

- Li, P.; et al. Analysis of quality and microstructure of freshly potato strips fried with different oils. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 133, 110038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Math, R.G.; et al. Effect of frying conditions on moisture, fat, and density of papad. J. Food Eng. 2004, 64, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokida, M.K.; Oreopoulou, V.; Maroulis, Z.B. Effect of Frying Condition on Shrinkage and Porosity of Fried Potatoes. J. Food Eng. 2000, 43, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazi, N.; Mizrahi, S.H.; Berk, Z. (1984). Heat and mass transfer in frying. In Engineering in foods, B.M. McKenna Ed.; Elsevier: New York, USA, 1984; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal, M.M. A new look at the chemistry and physics of deep fat frying. Food Technol. 1991, 45, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi, E.A.; et al. 3D computational simulation for the prediction of coupled momentum, heat and mass transfer during deep-fat frying of potato strips coated with different concentrations of alginate. J. Food Eng. 2018, 235, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghannya, J.; Abedpour, L. Influence of a three stage hybrid ultrasound–osmotic–frying process on production of low-fat fried potato strips. J. Sci. Food Agri. 2018, 98, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, A.; et al. Momentum, heat and mass transfer enhancement during deep-fat frying process of potato strips: Influence of convective oil temperature. Int. J.Therm. Sci. 2018, 134, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC, G. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. Rockville, MD: AOAC International, 2016, ISBN: 978-0-935584-87-5.

- Dehghannya, J.; et al. Shrinkage of mirabelle plum during hot air drying as influenced by ultrasound-assisted osmotic dehydration. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghannya, J.; et al. Low temperature hot air drying of potato cubes subjected to osmotic dehydration and intermittent microwave: Drying kinetics, energy consumption and product quality indexes. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 54, 929–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia, A.; et al. Evolution of mechanical and optical properties of French fries obtained by hot air-frying. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 57, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, N.; Kenari, R.E. Functionality of coatings with salep and basil seed gum for deep fried potato strips. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2016, 93, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellema, M. Mechanism and reduction of fat uptake in deep-fat fried foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2003, 14, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singthong, J.; Thongkaew, C. Using hydrocolloids to decrease oil absorption in banana chips. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 1199–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.Q.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.C.; Bhandari, B. Effects of ultrasound pretreatments on the quality of fried sweet potato (Ipomea batatas) chips during microwave-assisted vacuum frying. J. Food Process Eng. 2018, 41, e12879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhang, M.; Bhandari, B.; Guo, Z. Effect of ultrasound dielectric pretreatment on the oxidation resistance of vacuum-fried apple chips. J. Sci. Food Agri. 2018, 98, 4436–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adedeji, A.A.; Ngadi, M. Impact of freezing method, frying and storage on fat absorption kinetics and structural changes of parfried potato. J. Food Eng. 2018, 218, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, B.; Sahin, S.; Sumnu, G. Pore development, oil and moisture distribution in crust and core regions of potatoes during frying. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2016, 9, 1653–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, M.; et al. Effects of carrageenan, oil temperature and time of frying on Oil Uptake of Fried Potato Products. Iran Food Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2009, 5, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzini, Y.P.; Zandunadi, R.P. Lipid content in French fries after submission to different pre-frying methods. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2019, 17, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghannya, J.; Naghavi, E.A.; Ghanbarzadeh, B. Frying of potato strips pretreated by ultrasound-assisted air-drying. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2016, 40, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bchir, B.; Bouaziz, M.A.; Ettaib, R.; Sebii, H.; Danthine, S.; Blecker, C.; Besbes, S.; Attia, H. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted osmotic dehydration of pomegranate seeds (Punica granatum L.) using response surface methodology. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, O.D.; Mittal, G.S. Heat and moisture transfer and shrinkage simulation of deep-fat tofu frying. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Segovia, P.; Urbano-Ramos, A.M.; Fiszman, S.; Martínez Monzó, J. Effects of processing conditions on the quality of vacuum fried cassava chips (Manihot esculenta Crantz). LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 69, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobaharia, S.; Bassirib, A. Effect of processing conditions on some quality characteristics of vacuum-fried onion slices (Allium cepa L.) at various pre-frying treatments. J. Food Bioprocess Eng. 2021, 4, 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera, J.M. Why food microstructure? J. Food Eng. 2005, 67, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaiifar, A.M.; et al. Porosity development and its effect on oil uptake during frying process. J. Food Process Eng. 2010, 33, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fan, L. Effects of preliminary treatment by ultrasonic and convective air drying on the properties and oil absorption of potato chips. Ultrason Sonochem. 2021, 74, 105548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayustaningwarno, F.; Dekker, M.; Fogliano, V.; Verkerk, R. Effect of vacuum frying on quality attributes of fruits. Food Eng. Rev. 2017, 10, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; et al. Improving the energy efficiency and the quality of fried products using a novel vacuum frying assisted by combined ultrasound and microwave technology. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 50, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; et al. Edible coatings from sunflower head pectin to reduce lipid uptake in fried potato chips. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordin, K.; et al. Changes in food caused by deep fat frying-A review. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2013, 63, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Movahhed, S.; Chenarbon, H.A. Moisture content and oil uptake in potatoes (Cultivar Satina) during deep-fat frying. Potato Res. 2018, 61, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadalinejhad, S.; Dehghannya, J. Effects of ultrasound frequency and application time prior to deep-fat frying on quality aspects of fried potato strips. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 47, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, J.; Ngadi, M. Effect of batter formulation and pre-drying time ooil distribution fractions in fried batter. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 59, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaqpour, E.; Dehghannya, J.; Ghanbarzadeh, B. The effect of ultrasound and blanching on oil uptake during deep-fat frying of potato. J. Res. Innov. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 2, 323–337. [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi, E.; Dehghannya, J.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Rezaei-Mokarram, R. Empirical shrinkage modeling of potato strips pretreated with ultrasound and drying during deep-fat frying. Iranian J. Nutr. Sci. Food Technol. 2013, 8, 99–111. [Google Scholar]

| Number | Model equation | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | MR=a.exp(-b*t)+c | [36] |

| 2 | MR=a.t2+b*t+c | [17] |

| 3 | MR=exp(-a*t) | [17] |

| 4 | MR=1/(a*t+b) | [48] |

| Treatment | Moisture content (kg/kg) | Deff ×10-8 (m2/s) | Oil uptake (kg/kg) | Shrinkage (%) | Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 3.62c±0.79 | 3.46a±0.30 | 0.091a±0.05 | 0.24e±0.14 | 1.08abc±0.05 |

| C | 3.93b±0.87 | 3.41ab±0.16 | 0.082b±0.04 | 0.21f±0.11 | 1.10ab±0.05 |

| A | 4.11a±0.86 | 3.26abc±0.84 | 0.080bc±0.05 | 0.20f±0.11 | 1.11a±0.05 |

| S | 2.37g±0.56 | 2.06e±0.55 | 0.053g±0.03 | 0.34a±0.10 | 1.02ef±0.11 |

| SC | 2.71f±0.79 | 2.58cde±0.14 | 0.074cd±0.04 | 0.31bc±0.07 | 1.06bcd±0.09 |

| SA | 2.90e±0.70 | 2.78abcde±0.80 | 0.071de±0.04 | 0.31bcd±0.06 | 1.08abc±0.08 |

| N | 2.61f±0.66 | 2.15de±0.10 | 0.063f±0.03 | 0.33ab±0.08 | 1.00f±0.11 |

| NC | 2.89e±0.78 | 2.68bcde±0.15 | 0.076cd±0.04 | 0.29cd±0.06 | 1.04def±0.08 |

| NA | 3.08d±0.70 | 2.85abcd±0.47 | 0.067ef±0.04 | 0.28d±0.06 | 1.05cde±0.11 |

| Treatment | a* | b* | L* | ∆E | BI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | -5.21e±0.01 | 44.74a±1.5 | 43.87a±7.96 | 20.27e±1.00 | 223.47e±20.54 |

| C | -3.59d±0.03 | 44.17e±2.4 | 43.52a±7.24 | 21.11e±0.90 | 219.52e±32.65 |

| A | 0.51c±0.001 | 41.62b±1.6 | 37.90b±10.96 | 28.78d±1.50 | 291.79d±19.45 |

| S | 2.90b±0.01 | 37.18e±1.00 | 32.40d±12.30 | 36.38b±1.20 | 357.77b±30.33 |

| SC | 7.74a±0.02 | 35.50f±1.10 | 29.52e±13.66 | 40.88a±2.30 | 386.57a±20.66 |

| SA | 7.76a±0.04 | 33.14g±2.30 | 27.26f±12.30 | 43.26a±2.00 | 390.54a±41.32 |

| N | 2.73b±0.01 | 40.17d±2.00 | 35.46c±12.77 | 32.36c±1.70 | 332.76c±22.41 |

| NC | 2.64b±0.01 | 40.62d±2.03 | 36.06bc±9.35 | 31.36d±2.90 | 306.03d±36.78 |

| NA | 3.45b±0.02 | 42.38b±1.02 | 37.92b±10.72 | 30.10d±2.06 | 306.16d±48.59 |

| treatment | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | |

| Control | 0.990 | 0.015 | 0.985 | 0.018 | 0.979 | 0.026 | 0.990 | 0.014 |

| C | 0.996 | 0.009 | 0.995 | 0.010 | 0.962 | 0.034 | 0.985 | 0.019 |

| A | 0.996 | 0.008 | 0.998 | 0.005 | 0.955 | 0.036 | 0.980 | 0.021 |

| S | 0.989 | 0.015 | 0.983 | 0.019 | 0.957 | 0.038 | 0.978 | 0.022 |

| SC | 0.988 | 0.019 | 0.989 | 0.018 | 0.976 | 0.028 | 0.986 | 0.020 |

| SA | 0.992 | 0.015 | 0.991 | 0.016 | 0.940 | 0.049 | 0.974 | 0.029 |

| N | 0.998 | 0.015 | 0.988 | 0.017 | 0.929 | 0.052 | 0.965 | 0.030 |

| NC | 0.988 | 0.018 | 0.991 | 0.015 | 0.965 | 0.033 | 0.983 | 0.021 |

| NA | 0.991 | 0.015 | 0.995 | 0.011 | 0.937 | 0.048 | 0.970 | 0.029 |

| treatment | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | |

| Control | 0.988 | 0.0057 | 0.996 | 0.0030 | 0.994 | 0.0039 | 0.929 | 0.0158 |

| C | 0.982 | 0.0061 | 0.998 | 0.0018 | 0.992 | 0.0039 | 0.919 | 0.0147 |

| A | 0.982 | 0.0059 | 0.999 | 0.0013 | 0.993 | 0.0037 | 0.919 | 0.0143 |

| S | 0.980 | 0.0045 | 0.993 | 0.0025 | 0.984 | 0.0039 | 0.939 | 0.0086 |

| SC | 0.980 | 0.0058 | 0.994 | 0.0055 | 0.991 | 0.0040 | 0.918 | 0.0134 |

| SA | 0.976 | 0.0062 | 0.994 | 0.0031 | 0.987 | 0.0045 | 0.918 | 0.0129 |

| N | 0.982 | 0.0049 | 0.997 | 0.0019 | 0.989 | 0.0038 | 0.934 | 0.0106 |

| NC | 0.984 | 0.0054 | 0.998 | 0.0017 | 0.994 | 0.0032 | 0.918 | 0.0139 |

| NA | 0.979 | 0.0054 | 0.997 | 0.0018 | 0.991 | 0.0036 | 0.918 | 0.0121 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).