Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Proposing the concept of full-cost electricity pricing, which integrates generation marginal costs and effective transmission costs, addressing the deficiencies in the current nodal pricing system.

- Refining the transmission cost allocation mechanism using power flow tracing technology and establishing a price signal system based on the principle of “costs borne by beneficiaries.”

- Validating the model’s effectiveness in optimizing power grid resource allocation, alleviating grid congestion, and enhancing investment efficiency through case studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fundamental Concept of Full-Cost Electricity Pricing

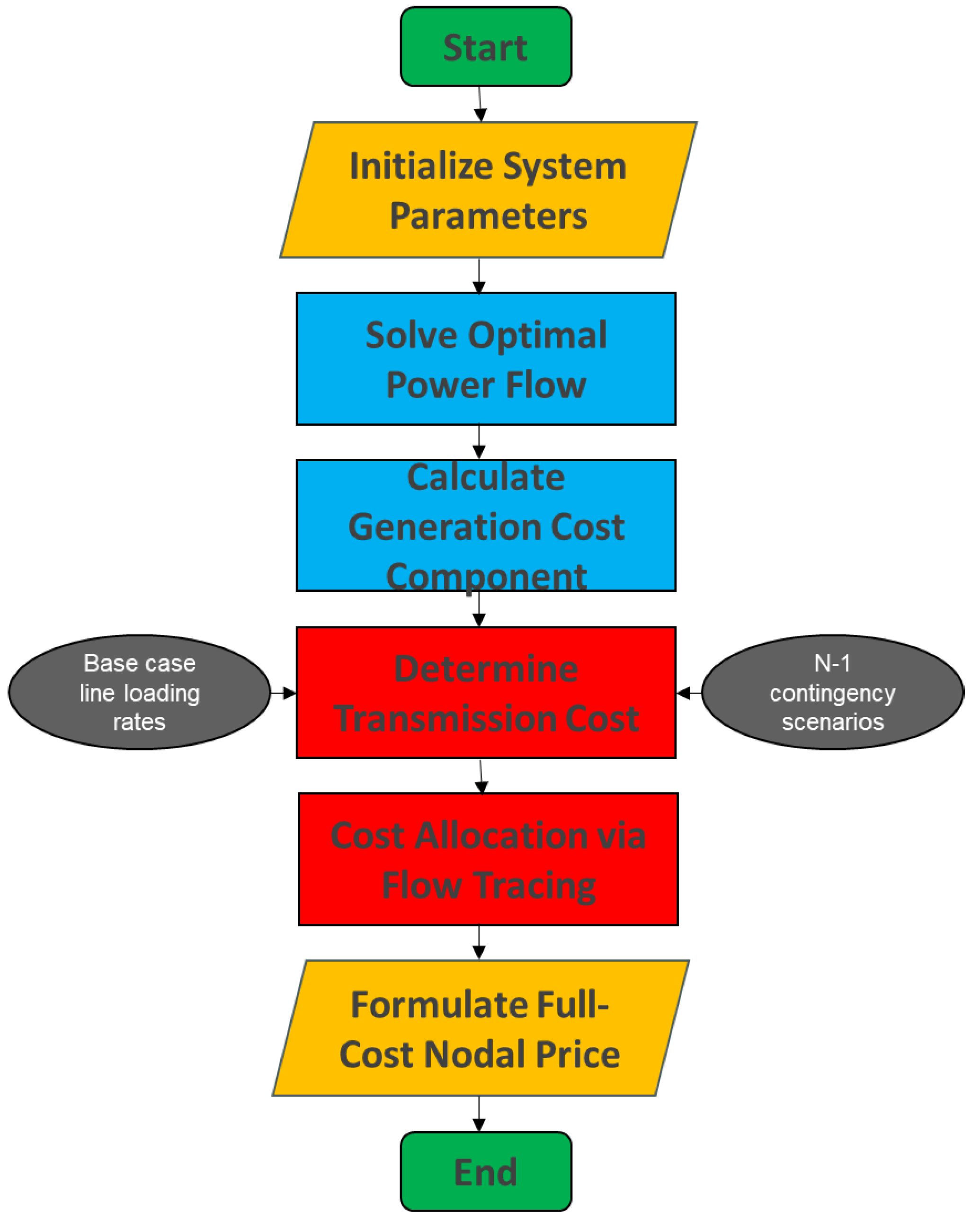

2.2. Derivation of Full-Cost Electricity Pricing Based on Power Flow Tracing Method

3. Case Study

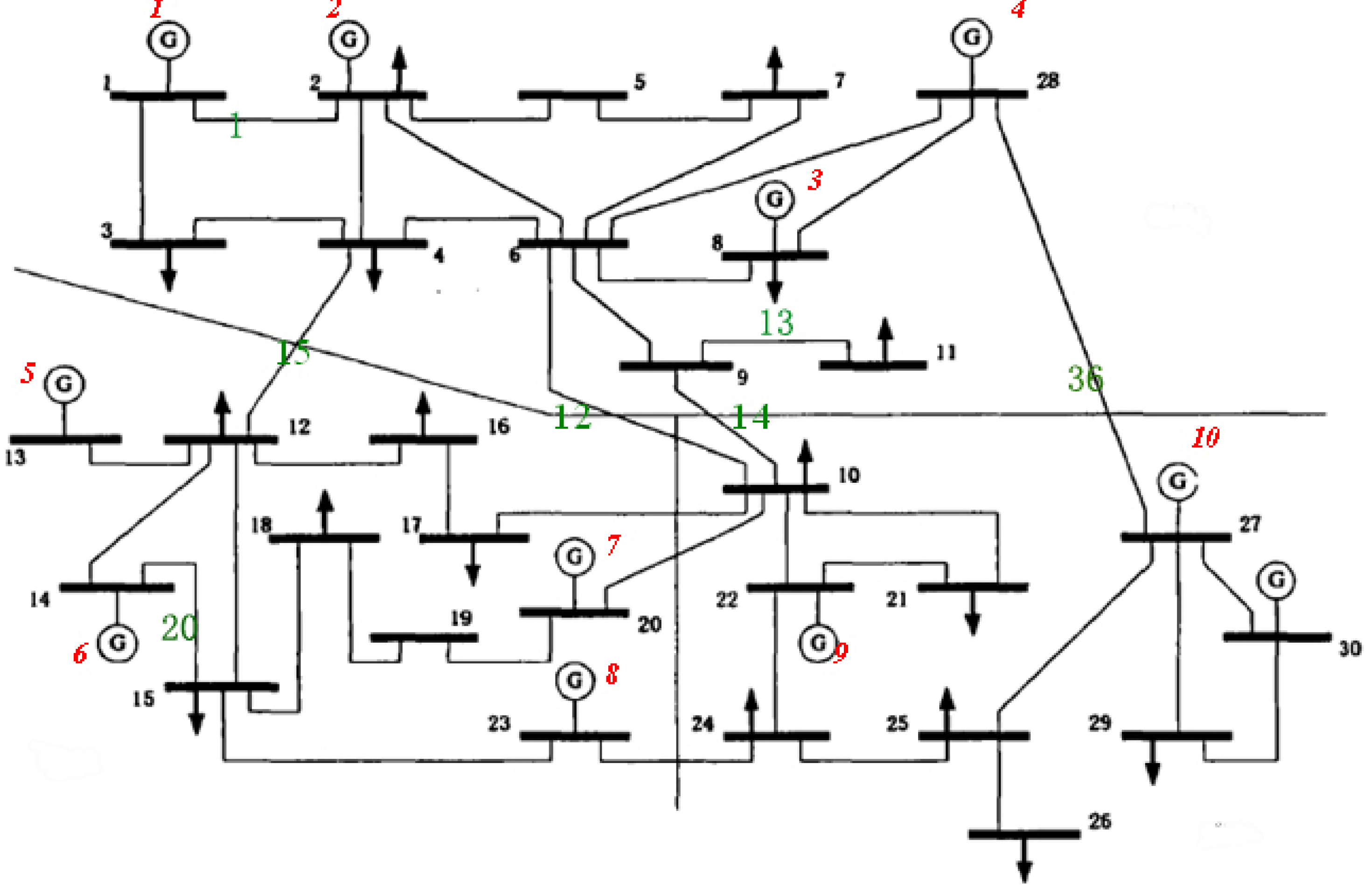

3.1. Case Study on Power Flow Tracing Model

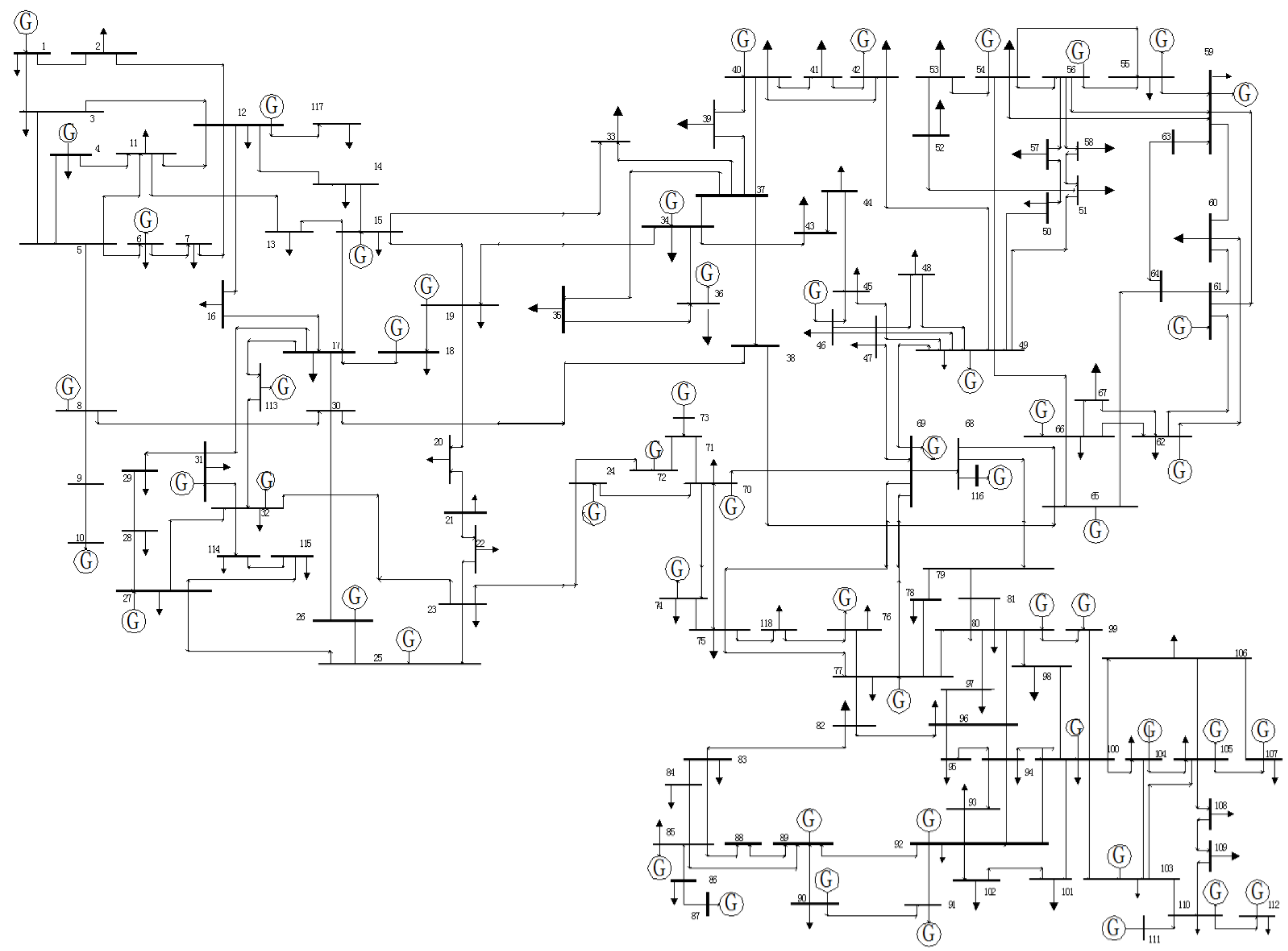

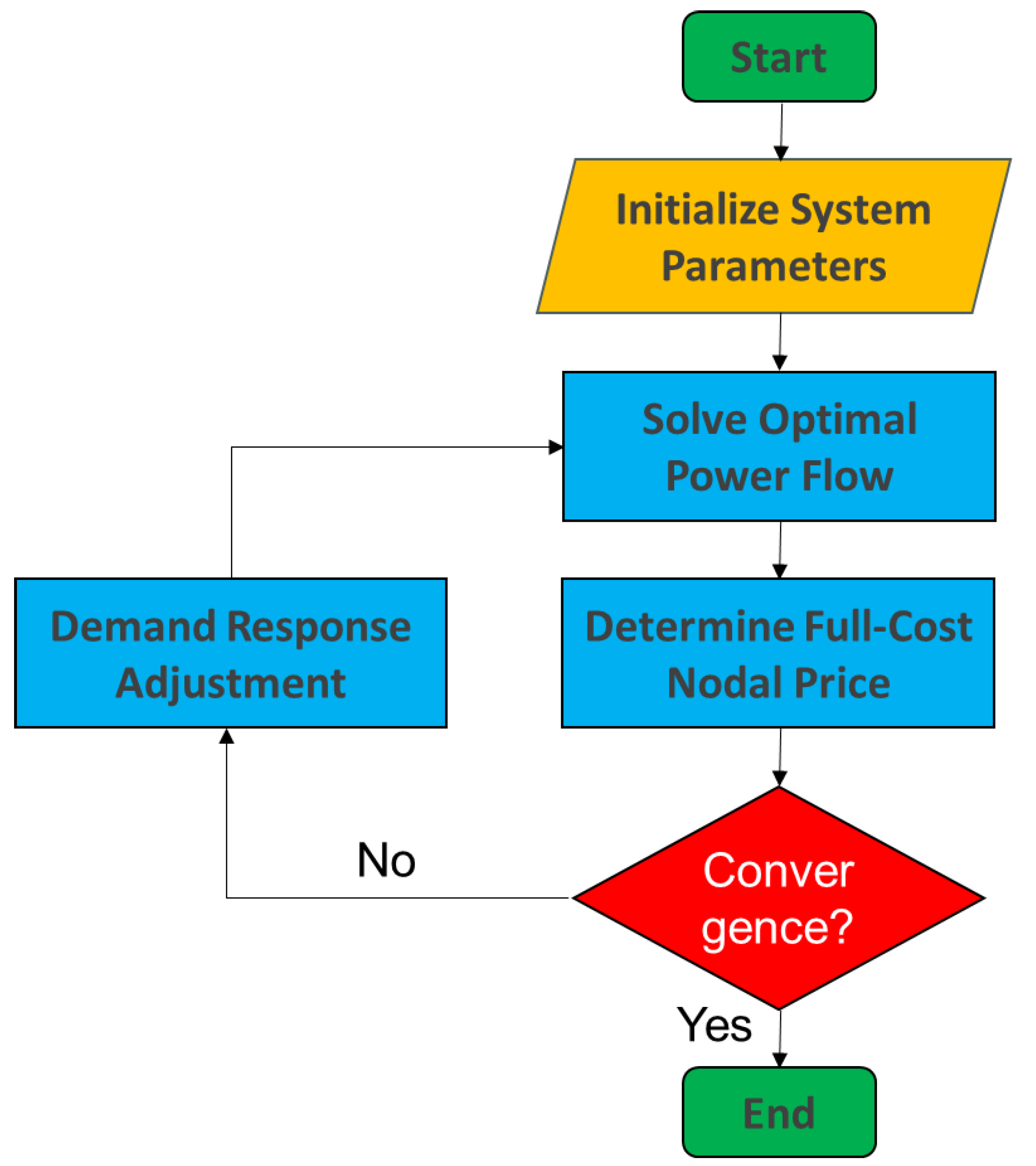

3.2. Security-Constrained Power Spot Market Based on Power Flow Tracing Method

3.2.1. Objective Function

3.2.2. Constraints

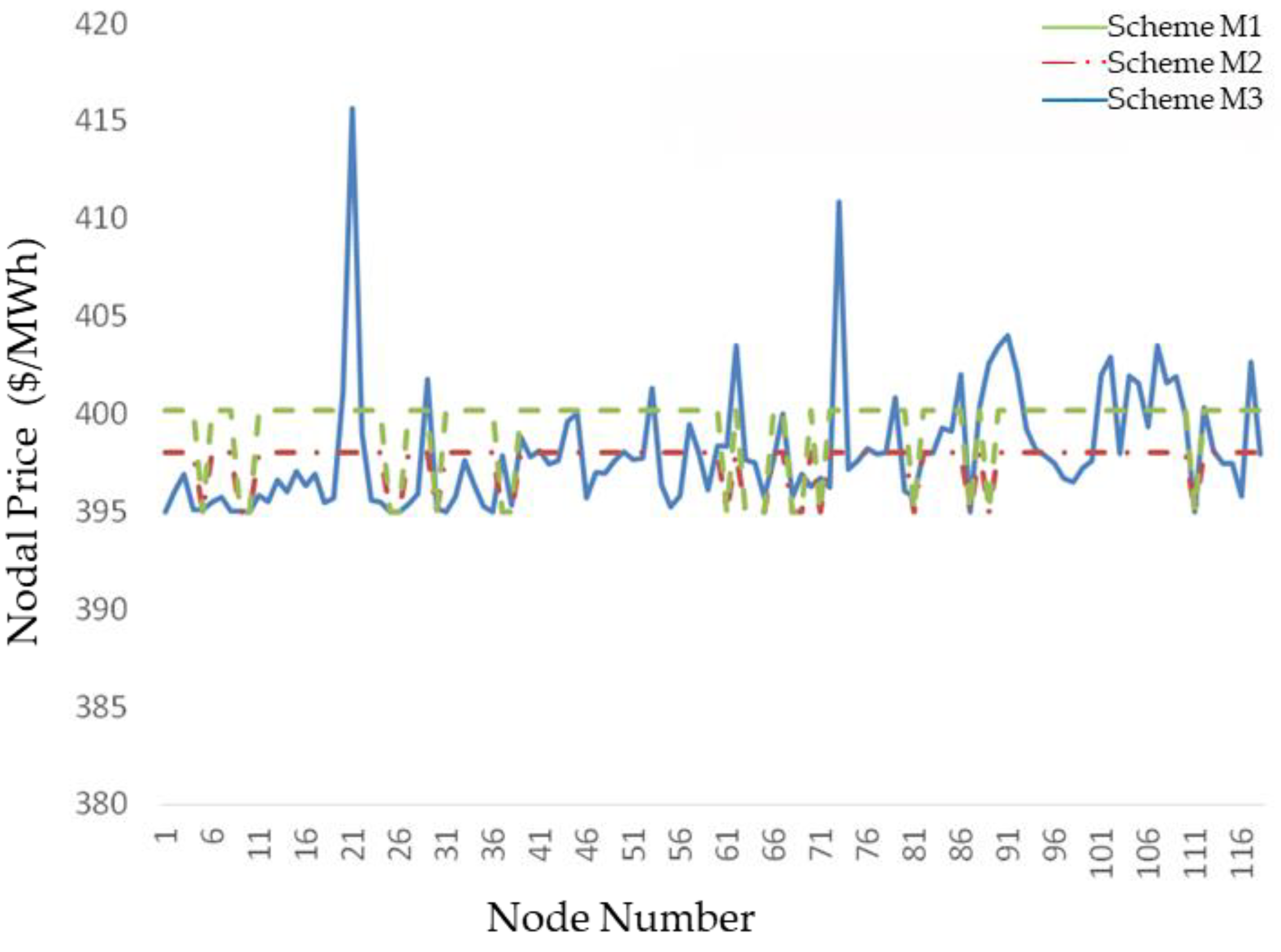

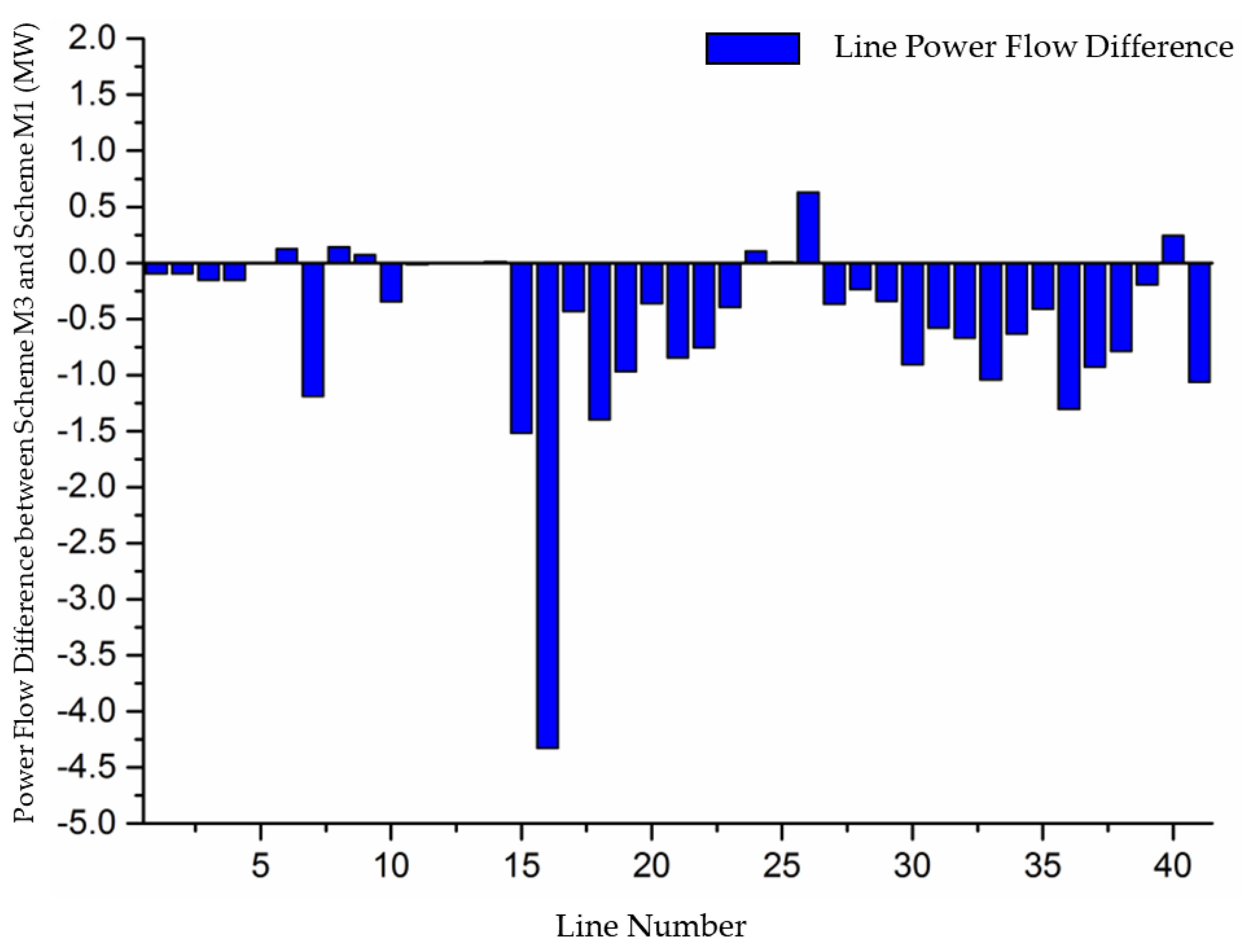

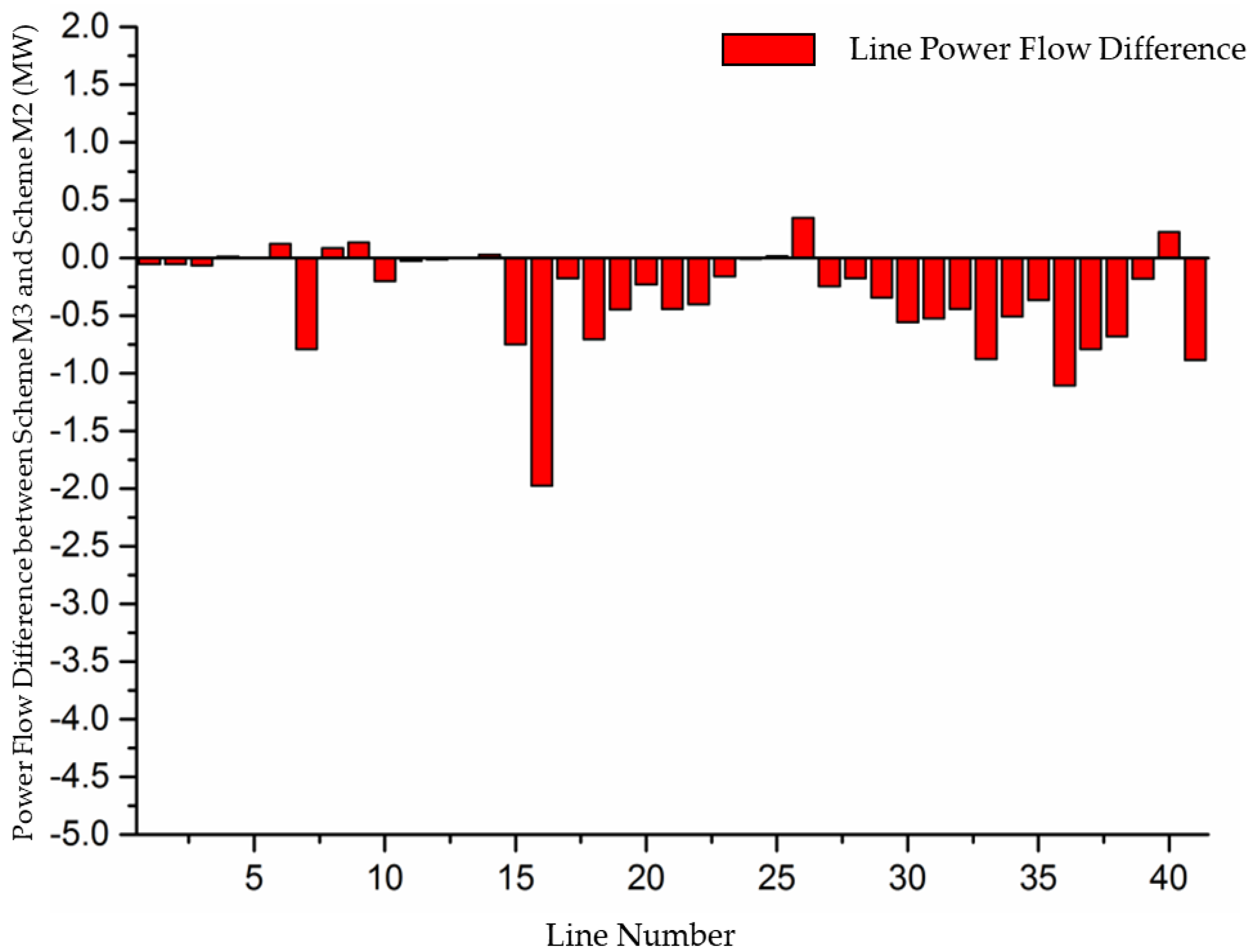

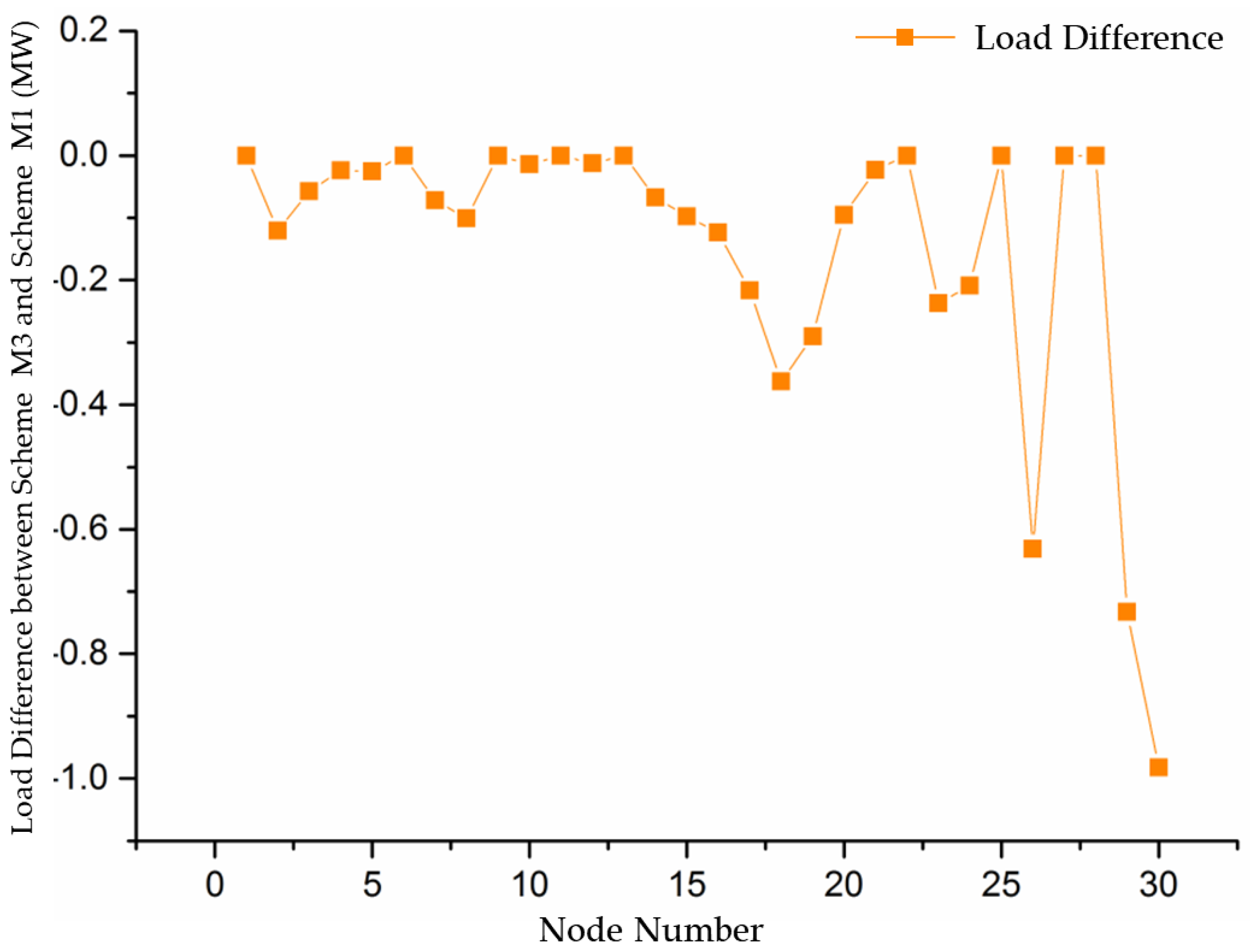

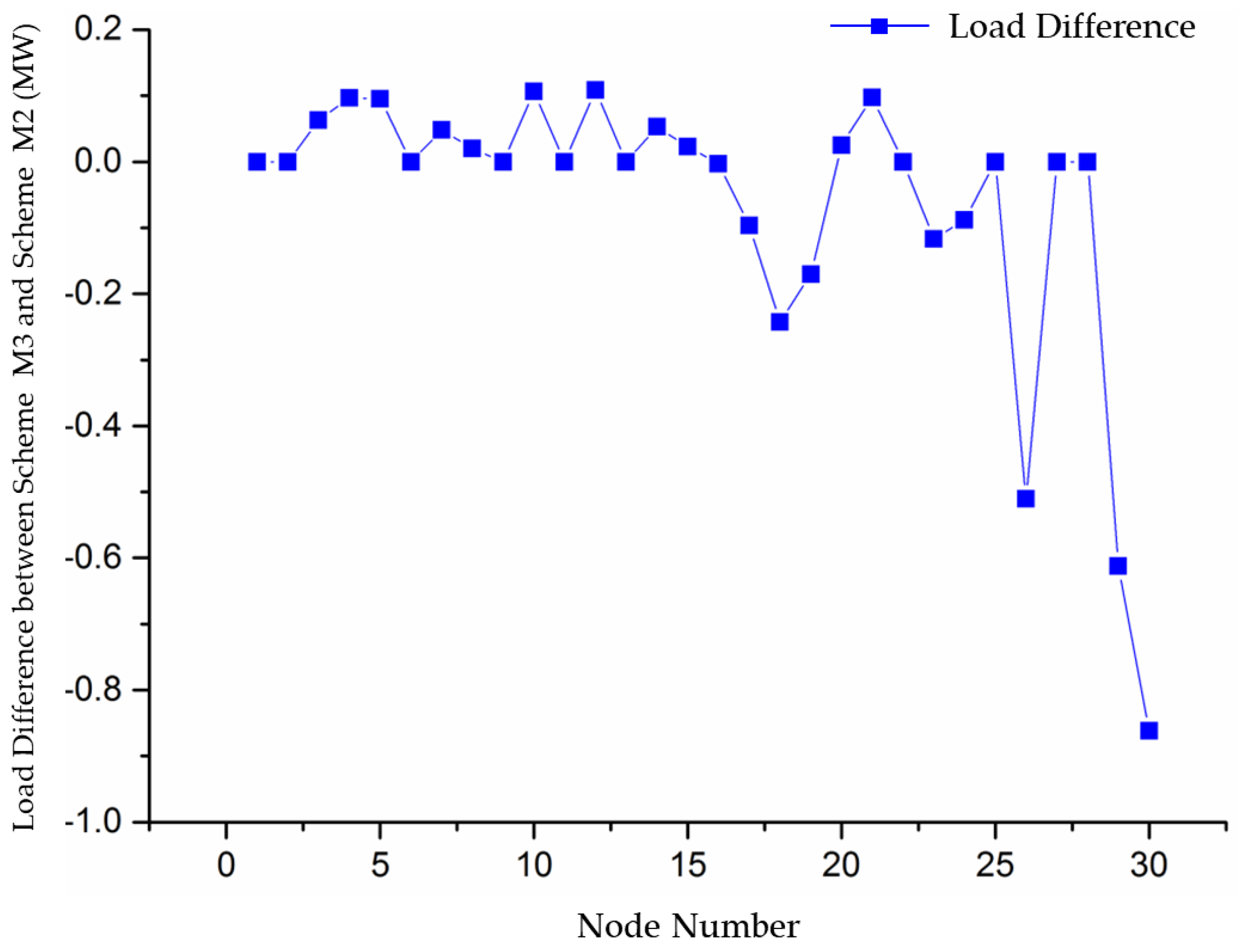

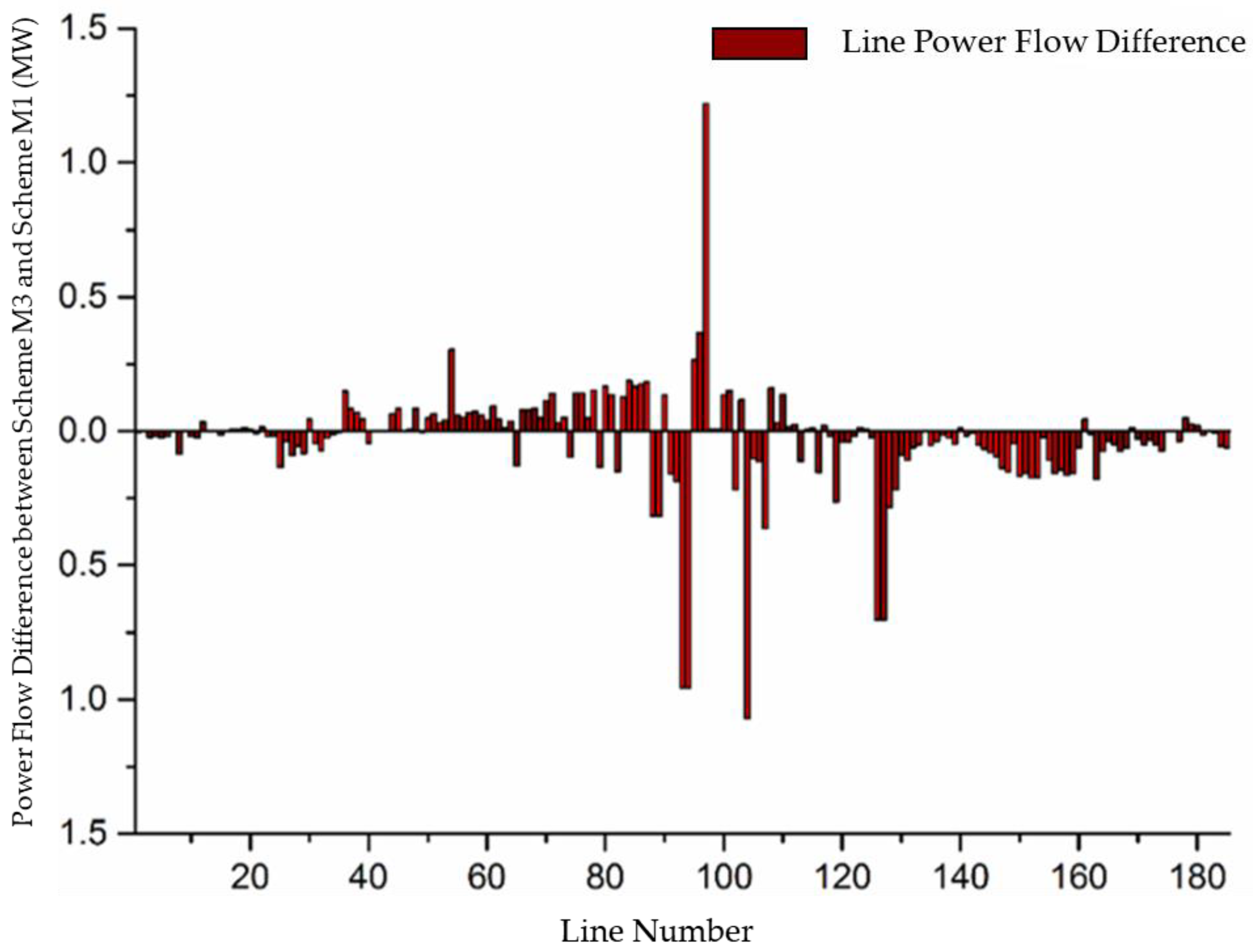

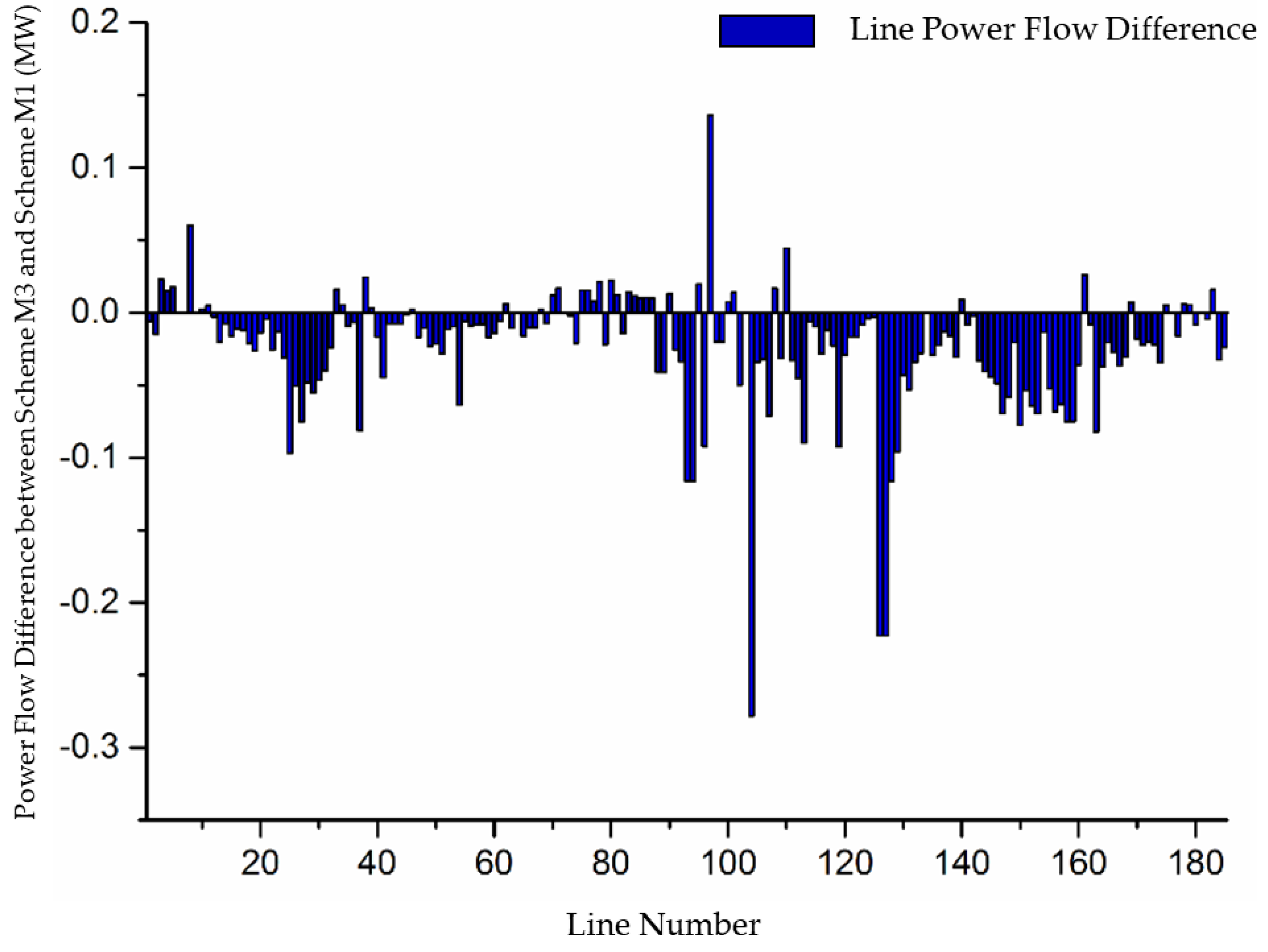

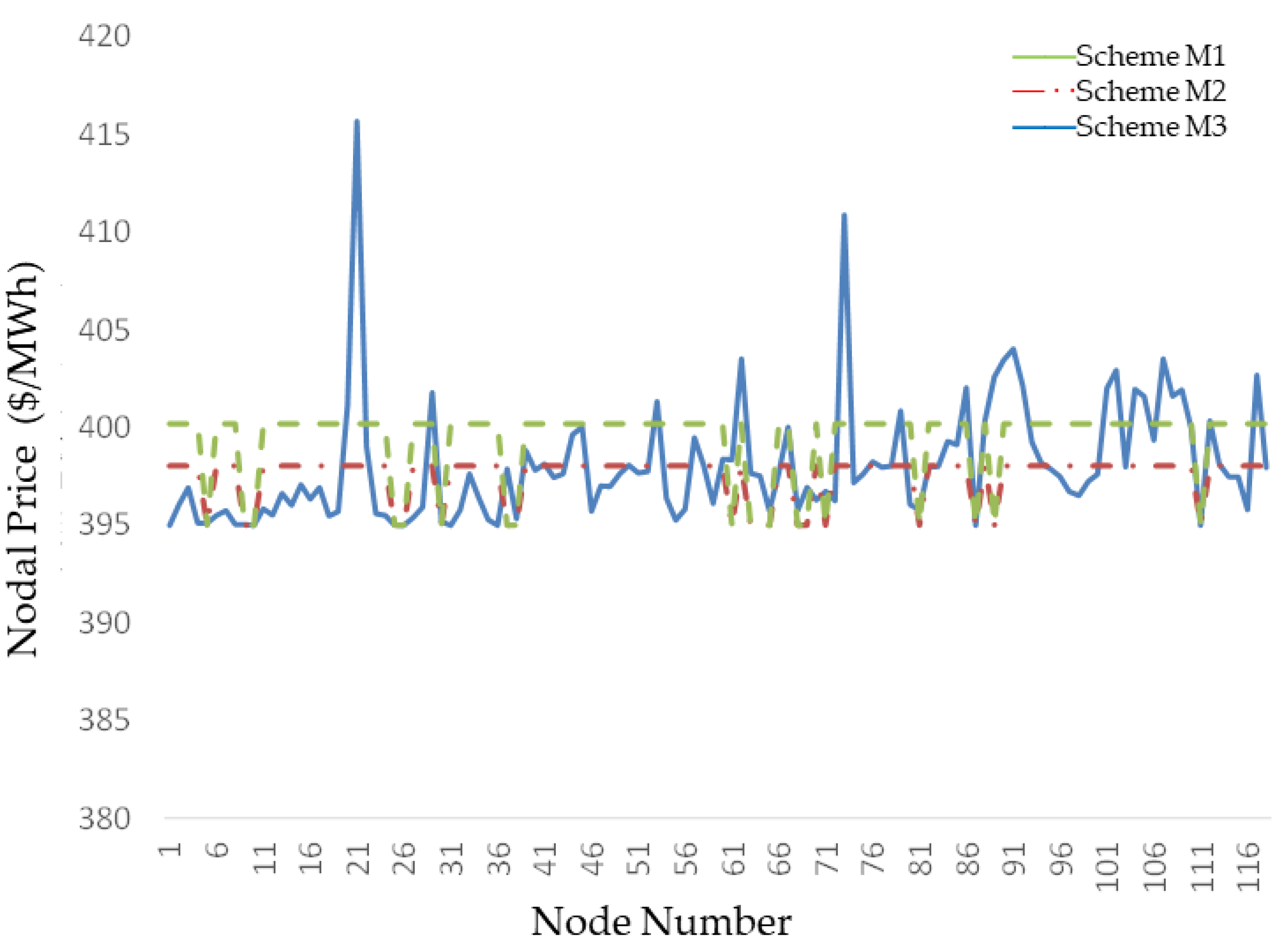

3.3. Case Study on Security-Constrained Economic Dispatch in the Power Spot Market

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

Appendix 1

| Unit ID | Capacity (MW) | Node Location | Operating Cost ($/MWh) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 1 | 380 |

| 2 | 100 | 2 | 400 |

| 3 | 100 | 5 | 370 |

| 4 | 100 | 8 | 390 |

| 5 | 140 | 11 | 350 |

| 6 | 100 | 13 | 360 |

| Line ID | Start-End Node IDs | Transmission Capacity (MW) | Reactance (p. u.) | Investment Cost ($M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-2 | 10 | 0.575 | 61.5 |

| 2 | 1-3 | 10 | 0.165 | 169.2 |

| 3 | 2-4 | 15 | 0.173 | 177.7 |

| 4 | 3-4 | 20 | 0.037 | 41.9 |

| 5 | 2-5 | 5 | 0.198 | 202.3 |

| 6 | 2-6 | 10 | 0.176 | 180.3 |

| 7 | 4-6 | 15 | 0.041 | 45.4 |

| 8 | 5-7 | 10 | 0.116 | 120 |

| 9 | 6-7 | 30 | 0.082 | 86 |

| 10 | 6-8 | 30 | 0.042 | 46 |

| 11 | 6-9 | 80 | 0.205 | 212 |

| 12 | 6-10 | 15 | 0.556 | 560 |

| 13 | 9-11 | 150 | 0.208 | 212 |

| 14 | 9-10 | 80 | 0.110 | 114 |

| 15 | 4-12 | 50 | 0.256 | 260 |

| 16 | 12-13 | 150 | 0.140 | 144 |

| 17 | 12-14 | 20 | 0.256 | 259.9 |

| 18 | 12-15 | 30 | 0.130 | 134.4 |

| 19 | 12-16 | 20 | 0.198 | 202.7 |

| 20 | 14-15 | 10 | 0.199 | 203.7 |

| 21 | 16-17 | 20 | 0.192 | 196.3 |

| 22 | 15-18 | 20 | 0.219 | 222.5 |

| 23 | 18-19 | 10 | 0.129 | 133.2 |

| 24 | 19-20 | 5 | 0.068 | 72 |

| 25 | 10-20 | 10 | 0.209 | 213 |

| 26 | 10-17 | 5 | 0.085 | 88.5 |

| 27 | 10-21 | 30 | 0.075 | 78.9 |

| 28 | 10-22 | 20 | 0.150 | 153.9 |

| 29 | 21-22 | 5 | 0.023 | 27.6 |

| 30 | 15-23 | 20 | 0.202 | 206 |

| 31 | 22-24 | 20 | 0.179 | 183 |

| 32 | 23-24 | 20 | 0.270 | 274 |

| 33 | 24-25 | 20 | 0.330 | 333.2 |

| 34 | 25-26 | 10 | 0.380 | 384 |

| 35 | 25-27 | 10 | 0.209 | 212.7 |

| 36 | 27-28 | 20 | 0.396 | 400 |

| 37 | 27-29 | 10 | 0.415 | 419.3 |

| 38 | 27-30 | 10 | 0.603 | 606.7 |

| 39 | 29-30 | 5 | 0.453 | 457.3 |

| 40 | 8-28 | 5 | 0.200 | 204 |

| 41 | 6-28 | 20 | 0.600 | 63.9 |

References

- Yan, S., Wang, W., Li, X. et al. Research on cross-provincial power trading strategy considering the medium and long-term trading plan. Sci Rep 14, 30137 (2024). [CrossRef]

- 2. SUN Dayan, GUAN Li, HU Chenxu, LUO Zhiqiang, WANG Delin, YU Zhao, CUI Hui, HAN Bin. Design and Exploration of Inter-provincial Power Spot Trading Mechanism[J]. Power System Technology, 2022, 46(2): 421-428. [CrossRef]

- J. Guo, Y. Niu and D. Wang, "Research on new energy direct participation in cross-provincial power trading mechanism," 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Information Technology, Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (ICIBA), Chongqing, China, 2023, pp. 86-90. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, Q. Zhao, Y.Ye, Z. Chen, Design and Empirical Research on Cross-provincial and Cross-regional Power Transmission Pricing Mechanism Adapted to Marketized Trading in China, [J]. Procedia Computer Science, 2024, 242, pp. 332-339. [CrossRef]

- Yi Chen, Han Wang, Zheng Yan, Xiaoyuan Xu, Dan Zeng, Bin Ma, A two-phase market clearing framework for inter-provincial electricity trading in Chinese power grids[J]. Sustainable Cities and Society, 2022, 85. [CrossRef]

- GE Rui, CHEN Longxiang, WANG Yiyu, LIU Dunnan. Optimization and Design of Construction Route for Electricity Market in China[J]. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2017, 41(24): 10-15.

- FAN Yuqi, DING Tao, SUN Yuge, HE Yuankang, WANG Caixia, WANG Yongqing, CHEN Tian'en, LIU Jian. Review and Cogitation for Worldwide Spot Market Development to Promote Renewable Energy Accommodation[J]. Proceedings of the CSEE, 2021, 41(5): 1729-1751. [CrossRef]

- ZOU Peng, CHEN Qixin, XIA Qing, et al. Logical Analysis of Electricity Spot Market Design in Foreign Countries and Enlightenment and Policy Suggestions for China[J]. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2014, 38(13):18-27. [CrossRef]

- CHEN Qixin, FANG Xichen, GUO Hongye, WANG Xuanyuan, YANG Zhenglin, CAO Rongzhang, XIA Qing. Progress and Key Issues for Construction of Electricity Spot Market[J]. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2021, 45(6): 3-15.

- CHENG Haihua, ZHENG Yaxian, GEN Jian, WU Han, TANG Honghai, LYU Qiaozhen. Path Optimization Model of Trans-regional and Trans-provincial Electricity Trade Based on Expand Network Flow[J]. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2016, 40(9): 129-134.

- Alvaro Baillo, Mariano Ventosa, Michel Rivier etal. Optimal Offering Strategies for Generation Companies Operating in Electricity Spot Markets[J] . IEEE Transactions on Power Systems: A Publication of the Power Engineering Society,2004,19(2):745-753.

- Victor Joel E. Franciso. Strategic Bidding and Scheduling in Reserve Co-optimized Based Electricity Spot Markets[C]. TENCON 2010 - 2010 IEEE Region 10 Conference, Japan,2010:592-597.

- Rocio Herranz, Antonio Munoz San Roque, Jose Villar, Optimal Demand-Side Bidding Strategiesin Electricity Spot Markets[J]. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems,2012,27(3):1204-1213.

- F.S. Wen and A.K. David. Optimally coordinated bidding strategies in energy and ancillary service markets[J]. IEE Proceedings - Generation, Transmission and Distribution,2002,149(3):331-339.

- ANG Bin,XIA Ye,XIA Qing,et al. Security constraint economic dispatch of AC/DC interconnected power grid based on Benders decomposition method [J]. Proceedings of the CSEE,2016,36(6) :1588-1595.

- XU Dan,CAI Zhi,ZHOU Jingyang. A fast solution method for large-scale security constraint dispatch based on heuristic linear.

- BAO Minglei, DING Yi, SHAO Changzheng, SONG Yonghua. Review of Nordic Electricity Market and Its Suggestions for China[J]. Proceedings of the CSEE, 2017, 37(17): 4881-4892,5207. [CrossRef]

- BUCHHOLZA W, DIPPLB L, EICHENSEER M. Subsidizing renewables as part of taking leadership in international climate policy: the German case[J]. Energy Policy, 2019, 129: 765-773. [CrossRef]

- S. Dai, Z. Cai, Q. Li and Q. Ding, "Analysis and Design of Inter-provincial Electricity Spot Market Model in China," 2021 IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Computer Applications (ICPECA), Shenyang, China, 2021, pp. 355-360. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., Aslam, S., Keerio, M.U., Mirsaeidi, S., Mugheri, N.H., Ismail, M., Abbas, G., & Othmen, S. Optimal solution of multiobjective stable environmental economic power dispatch problem considering probabilistic wind and solar PV generation. Heliyon 2024, 10(20). [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y. Optimal Economic Scheduling Method for Power Systems Based on Whole-System-Cost Electricity Price. Energies 2023, 16, 7944. [CrossRef]

| Scheme | Total Generation Cost ($) | Total Transmission Cost ($) | Total Consumption Cost ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 87799.84 | 8363.00 | 96162.84 |

| M2 | 86888.47 | 4157.00 | 91045.46 |

| M3 | 86180.01 | 3960.53 | 90140.54 |

| Scheme | Total Load (MW) |

|---|---|

| M1 | 244.38 |

| M2 | 241.85 |

| M3 | 239.88 |

| Node Number | Scheme M1 ($/MWh) | Scheme M2 ($/MWh) | Scheme M3 ($/MWh) | Node Number | Scheme M1 ($/MWh) | Scheme M2 ($/MWh) | Scheme M3 ($/MWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 357.48 | 357.48 | 383.79 | 16 | 394.37 | 377.33 | 377.77 |

| 2 | 391.10 | 374.07 | 374.15 | 17 | 394.51 | 377.48 | 391.26 |

| 3 | 393.43 | 376.40 | 367.42 | 18 | 394.41 | 377.37 | 411.99 |

| 4 | 393.83 | 376.80 | 363.03 | 19 | 394.46 | 377.43 | 401.74 |

| 5 | 404.22 | 387.19 | 373.59 | 20 | 394.48 | 377.46 | 373.89 |

| 6 | 360.62 | 360.62 | 369.38 | 21 | 394.57 | 377.54 | 363.63 |

| 7 | 398.73 | 381.70 | 374.80 | 22 | 360.34 | 360.35 | 370.58 |

| 8 | 394.84 | 377.81 | 374.98 | 23 | 394.41 | 377.38 | 394.07 |

| 9 | 360.45 | 360.45 | 360.88 | 24 | 394.54 | 377.50 | 390.14 |

| 10 | 394.58 | 377.54 | 362.37 | 25 | 360.42 | 360.42 | 405.59 |

| 11 | 360.45 | 360.45 | 360.44 | 26 | 394.64 | 377.61 | 450.58 |

| 12 | 394.22 | 377.19 | 361.73 | 27 | 360.49 | 360.49 | 423.21 |

| 13 | 360.00 | 360.00 | 360.00 | 28 | 360.61 | 360.41 | 376.65 |

| 14 | 394.27 | 377.24 | 369.71 | 29 | 394.71 | 377.67 | 465.14 |

| 15 | 394.31 | 377.28 | 374.04 | 30 | 394.71 | 377.67 | 500.79 |

| Scheme | Total Generation Cost ($) | Total Transmission Cost ($) | Total Consumption Cost ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 152885.8 | 20600.7 | 173486.5 |

| M2 | 151803.5 | 13056 | 164859.5 |

| M3 | 151794.6 | 12044 | 163838.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).