1. Introduction

Fermented mandarin fish (

Siniperca chuatsi) and semi-dried yellow croaker (

Pseudosciaena crocea) are typical types of Chinese traditional fish products. Due to the rich nutrients and unique flavor, the two fish products have increased popularity among consumers in China [

1,

2]. The production of fermented mandarin fish involves blending mandarin fish with spices and salt, which is then subjected to spontaneous fermentation. While semi-dried yellow croaker is typically prepared by salting fresh large yellow croaker, followed by sun-drying under natural conditions until the muscle tissues attain a moisture content of 40-60%. However, the traditional production process is uncontrollable, with a complex microbial structure that readily produces harmful substances for humans, such as biogenic amines (BAs). Thus, high levels of BAs were common defects of the traditional meat products [

3].

BAs are low molecular nitrogenous compounds, produced from free amino acids by decarboxylation. These BAs will negatively affect the quality of fish products. In addition, as BAs are associated with vasoactive and psychoactive properties, their presence could be considered a potential health risk for some consumers [

4]. What’s worse, according to the previous report, BAs are difficult to be eliminated once they are formed [

5,

6]. Therefore, it is necessary to inhibit the production of BAs in food.

BAs are influenced by bacterial community, amino acids, environmental factors, processing methods, and storage conditions in food [

7]. Generally, the predominant genera in fish products were

Pseudomonas,

Vibrio and

Shewanella [

6,

8]. The strong BAs production bacteria were commonly associated with

Photobacterium phosphoreum,

Hafnia alvei,

Luminobacterium spp.,

Photobacterium phosphoreum and

Morganella morganii [

9]. These isolate species always present capabilities of multiple BAs production. However, the bacteria contribute to BA production in the two typical types of Chinese traditional fish products is not clear. Thus, the objective of the present research was to investigate the BAs and bacterial community in the two typical species of fish products using LC-MS/MS and high-throughput sequencing. The isolation, characterization and identification of BA-producing bacteria were also carried out in order to study their role in BAs production. To our best knowledge it is the first systematic study of BA-producing bacteria in these two types of aquatic products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Samples

A total of 20 specimens of fish products were randomly obtained from the local markets in Shanghai. The examined fish products were divided into 2 groups: (a) fermented mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi) samples (5 from Huangshan and 5 from Shanghai), (b) semi-dried yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea) samples (5 from Ningde and 5 from Zhoushan). To ensure the regional representativeness of the fish samples collected from each city, the samples originating from the same city were combined and promptly utilized for BAs analysis, viable cell counting and microbial assays. All the fish products were transported immediately to the laboratory using a portable refrigerator for the viable cell count and microbial assays. The rest of the fish samples were frozen at -80 °C for chemical analysis and DNA extraction.

2.2. Biogenic Amines Analysis

The BAs (CAD, TYR, TRY, HIS and PUT) were determined using HPLC–MS/MS [

10]. In brief, the BAs were extracted twice from 2 g fish samples with 40 mL 5% HClO

4. The extraction was then adjusted to pH 3 with NaOH solution and was diluted with 0.5% HClO

4 solution. 2 mL n–hexane was added for cleaning–up. Then 0.25 mL of the purified solution was diluted by 0.75 mL acetonitrile. The final mixture was analyzed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) equipped with a Shimadzu LC–30AD (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) connected to a 5500 QTRAP MS (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA). The target compounds were separated at 35 °C on a Waters XBridge

® HILIC (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 3.5 μm). The limits of detections (LODs) are in the range of 0.1–1.0 mg/kg. The intermediate level of standard solution was repeatedly detected every ten fish samples to calculate the reproducibility of the results. All the fish samples were examined with three replicates.

2.3. Total Visible Count and Microbial Community Analysis

The Total visible count (TVC) was detected using plate count agar (PCA) medium (Sangon, Shanghai, China). 25.0 g fish sample was weighed and homogenized with 225 mL of 0.85% (w/v) NaCl solution. The solution was then gradient diluted and spread on PCA medium. The TPC was determined after 2 d of incubation at 37 °C.

Total community genomic DNA extraction was performed using the Mag-Bind Soil DNA Kit (Omega, M5635-02, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. The concentration of the DNA was measured using a Qubit 4.0 (Thermo, USA) to ensure that adequate amounts of high-quality genomic DNA had been extracted. The V3–V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using primers 341F (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) and 805R (GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC). The PCR reactions were set up using 2×Hieff® Robust PCR Master Mix (Yeasen, 10105ES03, China). And the PCR products were purified with Hieff NGS™ DNA Selection Beads (Yeasen, 10105ES03, China). Sequencing was performed with the Illumina MiSeq system (Illumina MiSeq, USA). The Illumina readings were assembled using PEAR software (version 0.9.8). The effective tags were classified as operational taxonomic units (OTUs) of 97% similarity using Usearch software (version 11.0.667). The most abundant sequence was selected as the OTU representative sequence and classified taxonomically with the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP). Alpha Diversity was estimated with Mothur (version 3.8.31) to reflect microbial community diversity in the two fish products.

2.4. Bacterial Diversity Analysis by Culture-Dependent Method

2.4.1. Screening of BA-Producing Bacteria

The BA decarboxylase activity of bacteria was isolated according to the screening plate method described by Deng et al. [

11] with slight modification. The fish sample (10 g) was diluted with 90 mL of 0.85% (w/v) NaCl solution and homogenized. The homogenate was then serially diluted and spread on the Niven’s agar with the pH of 5.3 (0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% peptone, 2% agar, 0.25% phenylalanine, 0.25% tryptophan, 0.25% lysine, 0.25% tyrosine, 0.25% arginine, 0.25% histidine, 0.25% ornithine hydrochloride, 0.5% sodium chloride, 0.1% calcium carbonate, 0.005% pyridoxal 5’-phosphate and 0.006% bromocresol violet). Strains on the Niven’s agar plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Colonies with various morphologies were selected and the isolates were purified for four times. The pure colonies were inoculated and stored at -80 °C in the Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium containing glycerol (50%, v/v).

2.4.2. Identification of BA-Producing Bacteria

DNA extraction of BA-producing bacteria was performed according to the previously method of Wang et al. [

12]. The 16S rRNA gene sequencing was used to identify each BA-producing bacterium. A 25 μL amplification system, with DNA template (1 μL), 27F: AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG (1 μL), 1492R: GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT (1 μL), Tac Master Enzyme (12.5 μL) and sterile water (9.5 μL) was prepared for ordinarily PCR reaction under the conditions as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles (94 °C for 30 s, 57 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 90 s), with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR-amplified products were sequenced using 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China).

2.4.3. Aminogenic Capacity of BA-Producing Bacteria

The strains of BA-producing bacteria were cultured in the LB liquid media containing 0.25% ornithine hydrochloride, phenylalanine, tryptophan, lysine, tyrosine, arginine and histidine for 48 h at 30 °C. The concentrations of BAs in bacterial cultures were detected with LC–MS/MS according to the previous method [

10].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were analyzed in triplicate independently. The BAs contents and cell counts were expressed as means ± standard deviation. The statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 16.0 software (P < 0.05, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL., USA). The analysis of correlation was carried out using Pearson correlation coefficient. The analysis of BAs contents and cell counts in different fish samples were statistically performed with Wilcoxon test.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. BAs Levels and Microbial Count in Fish Products

The levels of BAs and microbial count in fish products purchased from four cities were listed in

Table 1. The results indicated that the most abundant BA detected in fish product samples was PUT (56.84 ± 5.35 mg/kg), followed by CAD (36.90 ± 2.55 mg/kg). In addition, CAD and HIS were detected in all the fish samples. However, TRY (0.91 ± 0.05 mg/kg) presented the lowest level and occurrence in the two fish products. In the case of fermented mandarin fish, 5 BAs were detected in both Huangshan and Shanghai samples, with the exception of TRY. These results of BAs in fish products were in agreement to the previous studies [

6,

13]. For the contribution of each BA to total contents in these fish samples, the fermented mandarin fish samples which had higher levels of BAs were characterized by a high contribution of PUT (52.1%) to total BAs, followed by CAD (32.5%). CAD (36.1%) presented the most prevalent BA to total levels in semi-dried yellow croaker samples. The amount of BAs and microbial count in fermented mandarin fish samples presented significantly higher than those in semi-dried yellow croaker samples (

P < 0.05).

Overall, the profile and level of BAs was distinct among the fish species and regions. The correlation was carried out using Pearson correlation coefficient. The BAs showed a significant positive correlation with microbial count (

P < 0.05). This result suggested that substrates and microbial communities in different fish products could contribute to the high BAs in fermented mandarin fish samples [

3,

7]. In this study, safe levels of HIS and TYR in the two fish products was observed [

5]. According to the previous studies, PUT and CAD can intensify the toxic effects of HIS and TYR, leading to harmful effects on human health [

3,

9]. Therefore, high levels of PUT and CAD in fermented mandarin fish products deserved more attention, as the amount of BAs could increase during storage. BAs are difficult to be eliminated once they are formed. Therefore, good hygiene and antimicrobial components could be used to reduce the health hazard of BAs formation in raw and processed food.

3.2. Alpha-Diversity in Fish Products

The diversity indices and coverage of fish samples from four different regions were detected (

Table 2). The coverages of all fish samples exceeded 0.998, indicating that sufficient microorganisms were detected in the samples. A total of 445,0096 effective sequences were clustered into 1,859 OTUs. In general, the Chao and Ace is used to estimate the richness of bacteria in samples. The Shannon and Simpson reflects the diversity of bacteria [

14,

15]. The Chao and Ace values in semi-dried yellow croaker were significantly higher than those in fermented mandarin fish (

P < 0.01), as were the Shannon and Simpson indices. The results indicated that the semi-dried yellow croaker samples exhibited higher richness and diversity of bacteria compared to the fermented mandarin fish. However, the differences in bacterial richness and diversity between regions for the same fish product not statistically significant (

P > 0.05). These results were similar to previous reports [

2,

8].

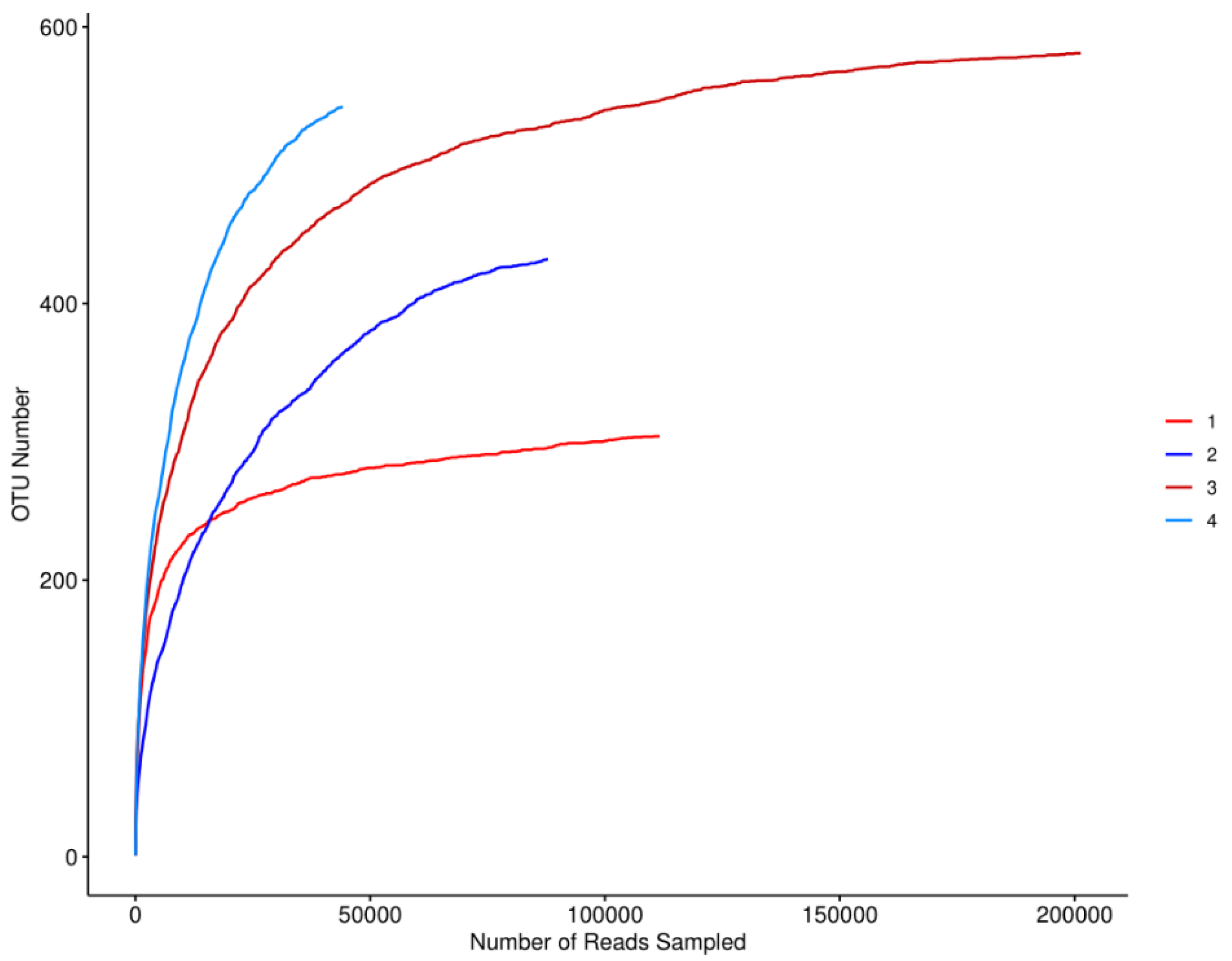

The rarefaction curves of microorganisms in fish samples from different regions were showed in

Figure 1. The curve was established using the sequencing data and the corresponding OTU number. The curves for semi-dried yellow croaker were higher than those of fermented mandarin fish, implying higher bacterial richness in semi-dried yellow croaker samples. All the rarefaction curves of microorganisms tended to be steady, which reflected a reasonableness of the amount of sequencing data.

3.3. Composition of Bacterial Community in Fish Products

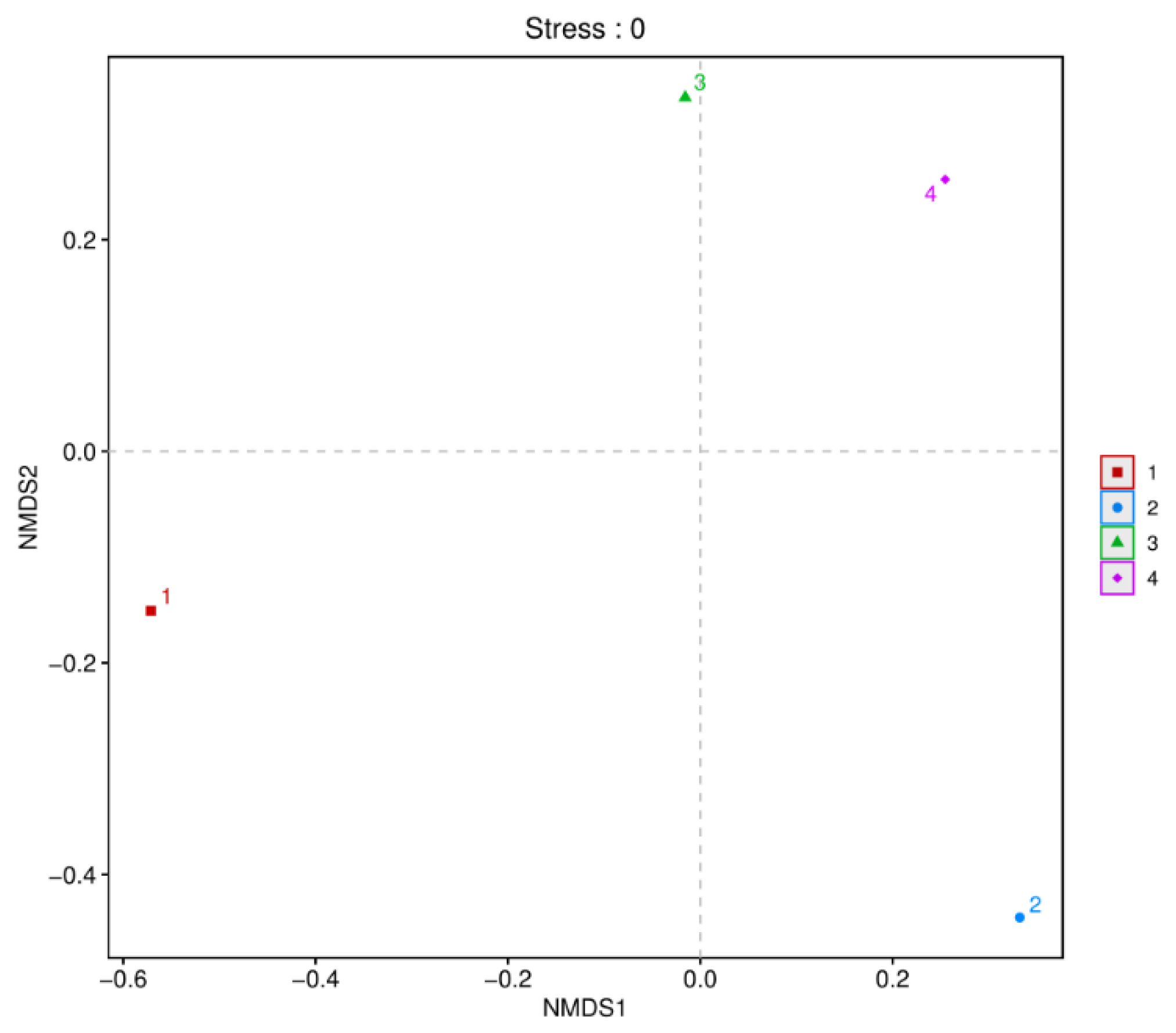

Beta diversity analysis is commonly used to describe the diversity of species composition. The dimensionality reduction technique of non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) can be used to analyze the similarity or dissimilarity between microbial samples. The distribution of samples along the continuous sorting axes (NMDS axes) can reveal general patterns of data change. This study used NMDS to identify similar or dissimilar microbial communities between the two fish products from different regions. As shown in

Figure 2, beta diversity analysis was performed based on OUT level. Significant differences in microbial communities were observed between the two fish products. The composition of the bacterial community in fermented mandarin fish samples from various regions differed, whereas semi-dried yellow croaker samples from different regions clustered more closely, demonstrating similarities in their bacterial communities.

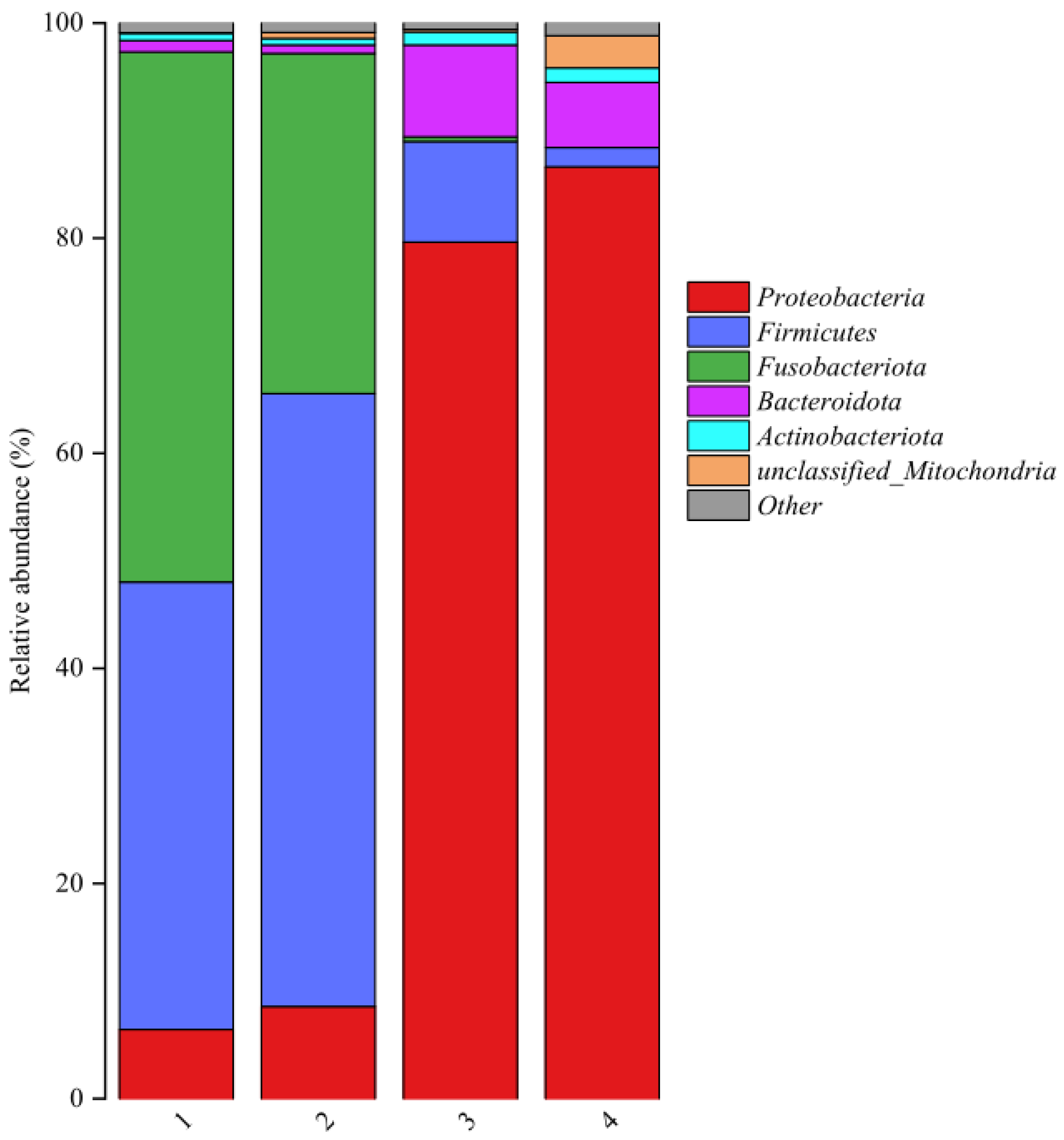

Relative abundance of bacterial communities at phylum level in fish products from different regions is shown in

Figure 3. Sequencing revealed that 6 bacteria phyla, including

Proteobacteria,

Firmicutes,

Fusobacteriota,

Bacteroidota,

Actinobacteriota, and unclassified_Mitochondria, were detected in the fish product samples. Although similar microorganisms were observed in fish product samples, notable differences emerged in their bacterial compositions.

Firmicutes,

Fusobacteriota and

Proteobacteria were the dominant phyla in fermented mandarin fish samples. This result was similar with previous literatures [

2,

15]. It has been reported that

Firmicutes and

Proteobacteria are common phyla, with 90% of the bacterial gene sequences identified belonging to these two phyla [

16].

Proteobacteria,

Firmicutes and

Bacteroidota were the major phylum in semi-dried yellow croaker samples. It has been reported that

Proteobacteria and

Firmicutes are usually observed to be the major community in marine fish [

1,

9]. The microorganisms detected in the samples likely originated from the raw materials employed in the fermentation process and could be considered as environmental microorganisms from the water, soil, and air. According to previous literature, amino acid and lipid metabolisms exhibit a close correlation with the presence of

Proteobacteria, whereas carbohydrate metabolism is intimately associated with the presence of

Firmicutes [

17].

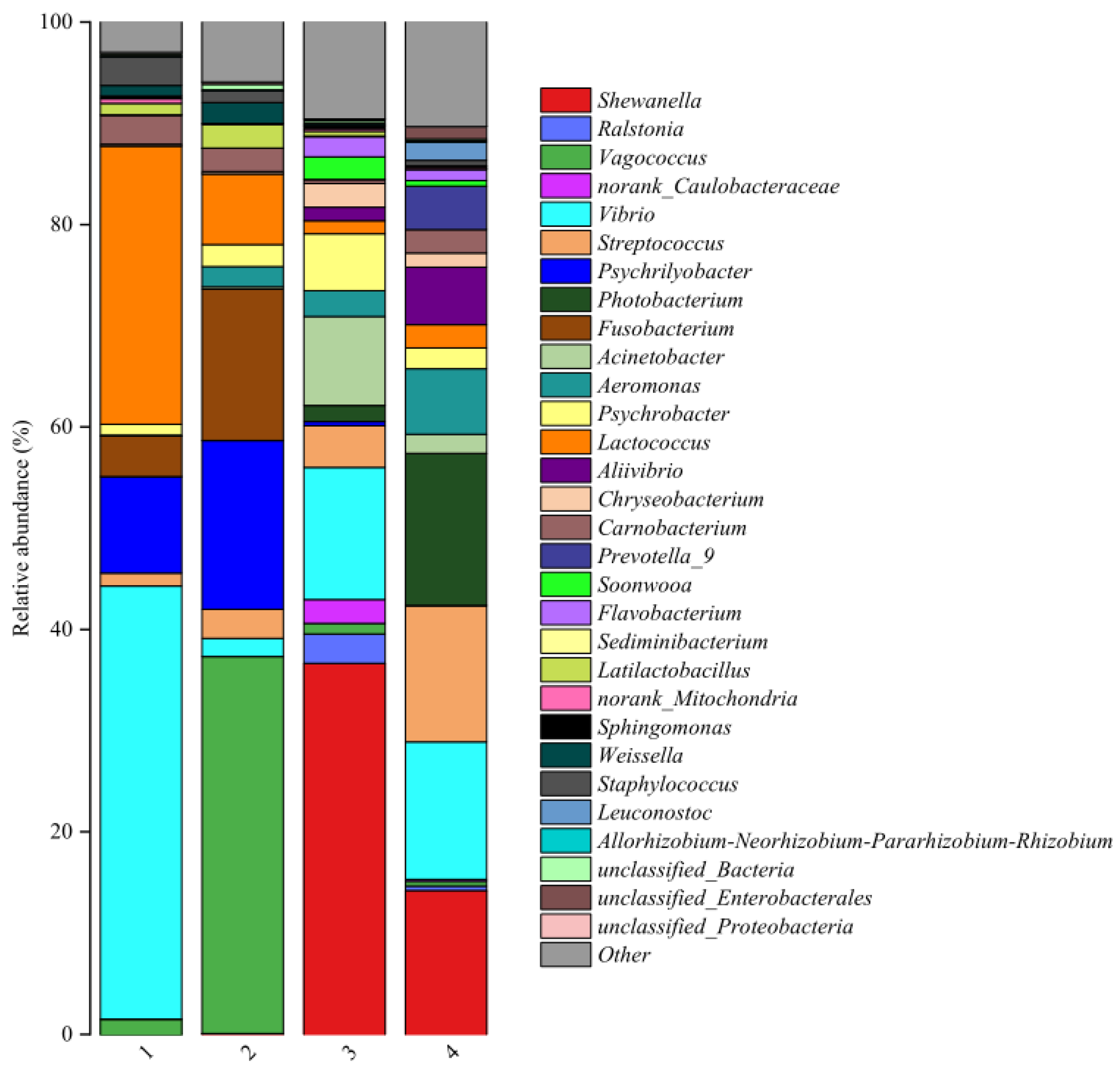

Figure 4 showed the relative abundance of bacterial communities at the genus level in the two fish products assumed from different regions and 30 bacteria genera were obtained. The microbial community at genus level was found to be similar within the same fish product from different regions, with notable differences between the two species of fish products. Moreover, the bacterial abundance was different in fish products purchased from different regions. The relative abundances of

Vibrio,

Vagococcus,

Lactococcus,

Psychrilyobacter,

Fusobacterium,

Carnobacterium,

Streptococcus,

Staphylococcus,

Latilactobacillus,

Psychrobacter,

Weissella, and

Aeromonas exceeded 2% in fermented mandarin fish samples. This result was similar with previous studies [

2,

8]. For the semi-dried yellow croaker samples, relative abundances of

Shewanella,

Vibrio,

Streptococcus,

Photobacterium,

Acinetobacter,

Aeromonas,

Psychrobacter,

Aliivibrio,

Prevotella_9,

Chryseobacterium,

Lactococcus,

Ralstonia,

Soonwooa,

Carnobacterium and

norank_Caulobacteraceae were over 2%. In addition, most of these bacteria are halotolerant or moderately halophilic, which are commonly observed in cured fish products [

18]. In the present study, high abundance of

Vibrio was found in all the fish samples, which is commonly identified as the primary cause of food spoilage. Meanwhile, it was reported that

Vibrio produced BAs in fish and fish products [

11,

19]. The microbial genera of

Shewanella,

Photobacterium,

Streptococcus and

Lactococcus have been widely found in seafood. Due to their high potential for spoilage, these genera are frequently associated with food spoilage [

20]. Moreover, these genera are considered to be the primary contributors to the formation of BAs formation from amino acids in fish. It is reported that PUT and CAD are the main BAs produced by

Shewanella baltica. The

Photobacterium sp. could produce 1000 mg/kg of HIS in fish [

21].

Streptococcus and

Lactococcus are intestinal flora of fish, which are positively related to concentrations of 2-PHE, TYR and PUT [

22,

23].

Vagococcus is considered as one of pathogens in aquaculture [

24].

Psychrilyobacter could promote the hydrolysis of alanine to produce BAs and flavor substances in fermented mandarin fish [

2].

3.4. Screening and Identification of BA-Producing Bacteria

In order to screen the BA-producing bacteria in fish products, BA-producing bacteria screening plate method was applied according to Deng et al. [

11]. After four times of purification, a total of 31 BAs-producing bacteria strains were screened from the two fish products (

Table 3). Different bacteria species can exhibit the same BA-producing characteristics and similar phenotypic characteristics [

25], therefore, it is necessary to use more reliable and precise identification method to describe the BA-producing bacteria of the fish products. The 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis was applied to identify the decarboxylase-positive isolates from the fish products.

The result showed that 7 and 9 BAs-producing bacteria strains were screened in fermented mandarin fish from Shanghai and Huangshan, respectively. BA-producing bacteria included

Lactobacillus sakei (4),

Bacillus cereus (3),

Hafnia alvei (3),

Psychrobacter faecalis (2),

Vagococcus fluvialis (1),

Aeromonas veronii (1),

Staphylococcus caprae (1) and

Lactococcus garvieae (1). The strain in fermented mandarin fish as the largest bacterial count belonged to specie

Lactobacillus sakei (4), followed by

Bacillus cereus (3),

Hafnia alvei (3). Regarding semi-dried yellow croaker samples, 7 and 10 strains of BA-producing bacteria were isolated from Ningde and Zhoushan, respectively. The bacteria species in samples included

Shewanella baltica (6),

Aeromonas veronii (3)

Ralstonia pickettii (1),

Acinetobacter johnsonii (1),

Psychrobacter faecalis (1),

Streptococcus parauberis (1),

Vibrio aphrogenes (1),

Photobacterium phosphoreum (1),

Prevotella 9 sp. (1) and

Aliivibrio salmonicida (1) were isolated. The most abundant BA-producing species in semi-dried yellow croaker samples was

Shewanella baltica (6), followed by

Aeromonas veronii (3). These results revealed that, the abundant and species of BA-producing bacteria were different in various fish products. Most of the bacteria species isolated in our study are often reported in fermented products [8,26). However, different strain species exhibit various capacities for BAs production, owing to the presence of diverse amino acid decarboxylases within these bacteria [

27,

28,

29].

3.5. Aminogenic Capacity of BA-Producing Bacteria

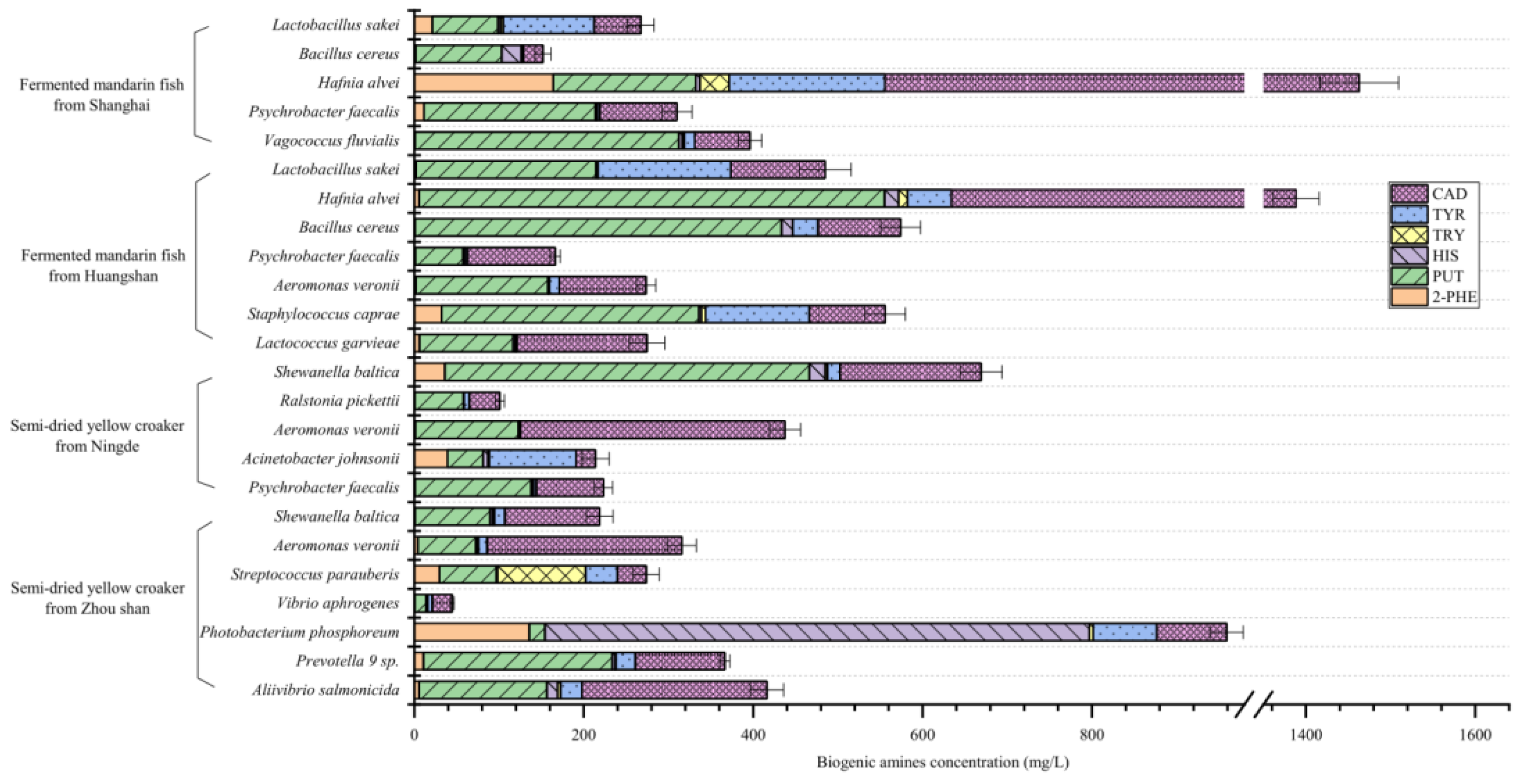

The capacity of each BA-producing bacteria specie was assessed by the presence of BAs in the LB liquid media. In this study, all the microorganisms were capable of producing multiple BAs, albeit with significantly varying capacities (

Figure 5). The largest amount of BA produced by bacteria was PUT ranging from 13.33 to 549.43 mg/L (mean = 170.83 mg/L), and CAD ranging from 22.95 to 907.60 mg/L (mean = 165.67 mg/L), followed by TYR ranging from 1.37 to 183.66 mg/L (mean = 41.81 mg/L) and HIS ranging from ND to 642.54 mg/L (mean = 34.88 mg/L). Among all the 31 strains, 31 produced PUT, CAD and TYR, 30 produced HIS, 29 produced 2-PHE, and 26 produced TRY.

In fermented mandarin fish,

Hafnia alvei was able to form up to 907.60 mg/L CAD, 549.43 mg/L PUT, 183.66 mg/L TYR, 16.54 mg/L HIS, 164.13 mg/L 2-PHE and 1463.06 mg/L total BAs. In this study,

Hafnia alvei produced the most abundant of CAD, PUT, TYR and 2-PHE, which was also detected as HIS producer in food. Lavizzari et al. [

30] reported that, this bacterium could produce more than 1000 mg/L HIS. Ding et al. [

26] described its capability to generate CAD, PUT and HIS. Li et al. [

31] reported that

Hafnia alvei produced abundant PUT and CAD in turbot flesh.

In the present study,

Lactobacillus sakei was the most frequently identified bacterium in fermented mandarin fish. It is generally reported in aquatic products, particularly fermented fish, exhibiting a remarkable TYR and PUT producing capacity [

32]. In recent years,

Lactobacillus sakei was used to inhibit BAs formation in fish products during processing [

27,

33,

34].

Bacillus cereus produced a high level of PUT (432.49 mg/L) and HIS (22.98 mg/L) isolated from fermented mandarin fish.

Bacillus cereus is usually regarded as a saprophytic bacterium, which is frequently detected in fermented food products as a BAs producer [

35]. In addition, because of a strong capable of catabolizing meat components,

Bacillus cereus can also produce flavor-rich metabolites during fermentation [

36]. The isolates of

Vagococcus fluvialis,

Psychrobacter faecalis,

Aeromonas veronii,

Staphylococcus caprae,

Lactococcus garvieae mainly produce PUT and CAD in this study. These BA-producing bacteria might also contribute to the unique flavor formation of fermented mandarin fish [

2,

8].

For semi-dried yellow croaker,

Shewanella baltica was the most frequently identified bacterium in the present study. This species has often been reported as powerful PUT-producing microorganisms, which is present in aquatic products [

37]. Indeed, PUT and CAD producing stains of

Shewanella baltica have been isolated in several seafood species, such as large yellow croaker, mussel, shrimp, golden pomfret, and horse mackerel [

38]. Bao et al. [

39] reported that, up to more than 1000 mg/L PUT was produced by these bacteria.

Photobacterium phosphoreum were the most powerful HIS (642.54 mg/L) producers, which aligns with previous studies [

37,

40].

Photobacterium is widespread in marine water, which is often isolated from seafood. Bjornsdottir-Butler et al. [

41] reported that,

Photobacterium phosphoreum produced the largest amount of HIS of all the

Photobacterium species studied. In our study, the

Photobacterium phosphoreum isolated from semi-dried yellow croaker could produce a high level of 2-PHE. Therefore, strains identified from different fish showed differences in the BA-producing capacity.

Acinetobacter johnsonii is commonly isolated from aquatic products, such as carp and sea bream [

42]. In this study,

Acinetobacter johnsonii present strong TYR (102.58 mg/L) generating capability. According to Wang et al. [

12], this species isolated from grass carp had moderate TYR producing capability.

Streptococcus parauberis produced up to 103.81 mg/L TRY, which also generated amino acids and flavor in fermented soybean products [

43]. Other isolates in semi-dried yellow croaker identified as

Ralstonia pickettii,

Aeromonas veronii,

Psychrobacter faecalis,

Vibrio aphrogenes,

Prevotella 9 sp., and

Aliivibrio salmonicida were all CAD and PUT producing strains as other authors reported [

26,

37].

These findings suggests that the BA-producing ability of these bacteria in the two fish products might pose a risk of BAs accumulation during storage. However, BA-producing microorganisms were probably not the primary cause of the high levels of BAs in fish products, as the presence of BAs is also influenced by the food substrate and environment [

4,

23].

4. Conclusions

The study reported on the bacterial community and its relationship with the production of BAs in two typical types of fish products in China. The amount of BAs was distinct among the fish species and regions. Both PUT and CAD were the most abundant BAs detected in fish product samples. All the microorganisms isolated from the two fish products produced multiple BAs. Corresponding to the BAs contents in the samples, the aminogenic bacteria mainly produced PUT and CAD. The strain in fermented mandarin fish as the largest bacterial count belonged to specie Lactobacillus sakei (mainly produced TYR and PUT), followed by Bacillus cereus (mainly produced PUT and HIS) and Hafnia alvei (mainly produced CAD, PUT, TYR and 2-PHE). The most abundant BA-producing species in semi-dried yellow croaker samples was Shewanella baltica (mainly produced PUT), followed by Aeromonas veronii (mainly produced CAD). Photobacterium phosphoreum produced the largest amount of HIS. The abundant, species and capability of BA-producing bacteria were different in various fish products. Further study is need to focus on developing potential starter cultures in the reduction of BA accumulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z.; methodology, X.Z. and H.C.; software, D.P.; validation, M.J. and C.W.; formal analysis, H.Z.; investigation, X.Z.; resources, X.Z. and L.L.; data curation, W.K.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, H.C.; supervision, X.Z.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Central Public–interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, ECSFR, CAFS (No. 2022TD02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mao, J.; Fu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Yuan, Y.; Chai, T.; Chen, Y. Flavor characteristics of semi-dried yellow croaker (Pseudosciaena crocea) with KCl and ultrasound under sodium-reduced conditions before and after low temperature vacuum heating. Food Chem. 2023, 426, 2023, 136574. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Li, L.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, X.; Wei, Y.; Huang, H. Comparison of the microbial community and flavor compounds in fermented mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi): Three typical types of Chinese fermented mandarin fish products. Food Res. Int. 2021, 144, 110365. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, C.; He, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Ho, C. Research advances on biogenic amines in traditional fermented foods: Emphasis on formation mechanism, detection and control methods. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134911. [CrossRef]

- Jaguey-Hernández, Y.; Aguilar-Arteaga, K.; Ojeda-Ramirez, D.; Añorve-Morga, J.; González-Olivares, L.G.; Castañeda-Ovando, A. Biogenic amines levels in food processing: Efforts for their control in foodstuffs. Food Res. Int. 2021, 144, 110341. [CrossRef]

- FDA. FDA and EPA safety levels in regulations and guidance. In Department of Health and Human Services, 4nd ed.; Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Office of Seafood, Fish and Fishery Products Hazards and Controls, Appendix 5: Florida, 2020; pp. A5–7.

- Tian, X.; Gao, P.; Xu, Y.; Xia, W.; Jiang, Q. Reduction of biogenic amines accumulation with improved flavor of low-salt fermented bream (Parabramis pekinensis) by two-stage fermentation with different temperature. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101438. [CrossRef]

- Dabadé, D.S.; Jacxsens, L.; Miclotte, L.; Abatih, E.; Devlieghere, F.; De Meulenaer, B. Survey of multiple biogenic amines and correlation to microbiological quality and free amino acids in foods. Food Control 2021, 120, 107497. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; Lv, J.; Sun, Z.; Xu, W.; Ji, C.; Liang, H.; Li, S.; Yu, C.; Lin, X. Microbial succession and the changes of flavor and aroma in Chouguiyu, a traditional Chinese fermented fish. Food Biosci. 2020, 37, 100725. [CrossRef]

- Halász, A.; Baráth, Á.; Simon-Sarkadi, L.; Holzapfel, W. Biogenic amines and their production by microorganisms in food. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1994, 5 (2), 42–49. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fang, C.; Huang, D.; Yang, G.; Tang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Kong, K.; Cao, P.; Cai, Y. Determination of 8 biogenic amines in aquatic products and their derived products by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry without derivatization. Food Chem. 2021, 361, 130044. [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Wu, G.; Zhou, L.; Chen, X.; Guo, L.; Luo, S.; Yin, Q. Microbial contribution to 14 biogenic amines accumulation in refrigerated raw and deep-fried hairtails (Trichiurus lepturus). Food Chem. 2024, 443, 138509. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Luo, Y.; Huang, H.; Xu, Q. Microbial succession of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) filets during storage at 4°C and its contribution to biogenic amines' formation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 190, 66–71. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Li, L.; Yang, L.; Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Y. Novel insight into physicochemical and flavor formation in naturally fermented tilapia sausage based on microbial metabolic network. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110122. [CrossRef]

- Aregbe, A.Y.; Mu, T.; Sun, H. Effect of different pretreatment on the microbial diversity of fermented potato revealed by high-throughput sequencing. Food Chem. 2019, 290, 125–134. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Eun, J. Shotgun metagenomics approach reveals the bacterial community and metabolic pathways in commercial hongeo product, a traditional Korean fermented skate product. Food Res. Int. 2020, 131, 109030. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T.; Whitman, W.B.; Coleman, D.C.; Jin, S.H.; Wang, H.C.; Chiu, C.Y. Soil bacterial communities at the treeline in subtropical alpine areas. CATENA 2021, 201, 105205. [CrossRef]

- Bhutia, M.O.; Thapa, N.; Shangpliang, H.N.J.; Tamang, J.P. Metataxonomic profiling of bacterial communities and their predictive functional profiles in traditionally preserved meat products of Sikkim state in India. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110002. [CrossRef]

- Bhutia, M.O.; Thapa, N.; Shangpliang, H.N.J.; Tamang, J.P. High-throughput sequence analysis of bacterial communities and their predictive functionalities in traditionally preserved fish products of Sikkim, India. Food Res. Int. 2020, 143, 109885. [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Li, Y. Biogenic amines are important indices for characterizing the freshness and hygienic quality of aquatic products: A review. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 194, 115793. [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Zhai, D.; Yang, H. Changes of metabolite profiles of fish models inoculated with Shewanella baltica during spoilage. Food Control 2021, 123, 107697. [CrossRef]

- Dalgaard, P.; Madsen, H.L.; Samieian, N.; Emborg, J. Biogenic amine formation and microbial spoilage in chilled garfish (Belone belone belone)–effect of modified atmosphere packaging and previous frozen storage. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 101(1), 80–95. [CrossRef]

- Belleggia, L.; Osimani A. Fermented fish and fermented fish-based products, an ever-growing source of microbial diversity: A literature review. Food Res. Int. 2023, 172, 113112. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Han, X.; Han, B.; Deng, H.; Wu, T.; Zhao, X.; Huang, W.; Zhan, J.; You, L. Survey of the biogenic amines in craft beer from the Chinese market and the analysis of the formation regularity during beer fermentation. Food Chem. 2023, 405, Part A, 134861. [CrossRef]

- Saticioglu, I.B.; Yardimci, B.; Altun, S.; Duman, M. A comprehensive perspective on a Vagococcus salmoninarum outbreak in rainbow trout broodstock. Aquaculture 2021, 545, 737224. [CrossRef]

- Henríquez-Aedo, K.; Durán, D.; Garcia, A.; Hengst, M.B.; Aranda, M. Identification of biogenic amines-producing lactic acid bacteria isolated from spontaneous malolactic fermentation of chilean red wines. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 68, 183e189. [CrossRef]

- Ding, A.; Zhu, M.; Qian, X.; Li, J.; Xiong, G.; Shi, L.; Wu, W.; Wang, L. Identification of amine-producing bacterium (APB) in Chinese fermented mandarin fish (Chouguiyu) by high-throughput sequencing and culture-dependent methods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 133, 106368. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Lu, S.. The importance of amine-degrading enzymes on the biogenic amine degradation in fermented foods: a review. Process Biochem. 2020, 99, 331–339. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.A.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. The problem of biogenic amines in fermented foods and the use of potential biogenic amine-degrading microorganisms as a solution. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 39(2), 146–155. [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Yang, Q.; Wan, W.; Zhu, Q.; Zeng, X. Physicochemical properties and adaptability of amine-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolated from traditional Chinese fermented fish (Suan yu). Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130885. [CrossRef]

- Lavizzari, T.; Breccia, M.; Bover-Cid, S.; Vidal-Carou, M.C.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T. Histamine, cadaverine, and putrescine produced in vitro by Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonadaceae isolated from spinach. J. Food Prot. 2010, 73 (2), 385–389. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Bi, J.; Hao, H.; Hou, H. The role and the determination of the LuxI protein binding targets in the formation of biogenic amines in Hafnia alvei H4. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 426, 110928. [CrossRef]

- Benkerroum, N. Biogenic amines in dairy products: origin, incidence, and control means. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15(4), 801–826. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lin, X.; Liang, H.; Zhang, S.; Ji, C. Lactobacillus strains inhibit biogenic amine formation in salted mackerel (Scomberomorus niphonius). LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 155, 112851. [CrossRef]

- Wunderlichová, L.; Buňková, L.; Koutný, M.; Jančová, P.; Buňka, B. Formation, Degradation, and Detoxification of Putrescine by Foodborne Bacteria: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13 (5), 1012–1030. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Chang, H.C. Assessment of Bacillus subtilis SN7 as a starter culture for Cheonggukjang, a Korean traditional fermented soybean food, and its capability to control Bacillus cereus in Cheonggukjang. Food Control 2017, 73, Part B, 946–953. [CrossRef]

- Shan, K.; Yao, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, T.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, M.; Ke, W.; He, H.; Li, C. Effect of probiotic Bacillus cereus DM423 on the flavor formation of fermented sausage. Food Res. Int. 2023, 172, 113210. [CrossRef]

- Lerfall, J.; Shumilina, E.; Jakobsen, A.N. The significance of Shewanella sp. strain HSO12, Photobacterium phosphoreum strain HS254 and packaging gas composition in quality deterioration of fresh saithe fillets. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 154, 112636. [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Hai, Y.; Le, Y.; Ran, X.; Yang, H. Metabolic and enzymatic changes of Shewanella baltica in golden pomfret broths during spoilage. Food Control 2023, 144, 109341. [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Wang, F.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, L.; Wang, Y. Ornithine Decarboxylation System of Shewanella baltica Regulates Putrescine Production and Acid Resistance. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84(2), 303–309. [CrossRef]

- Bjornsdottir-Butler, K.; May, S.; Hayes, M.; Abraham, A.; Benner Jr, R.A. Characterization of a novel enzyme from Photobacterium phosphoreum with histidine decarboxylase activity. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 334(2), 108815. [CrossRef]

- Bjornsdottir-Butler, K.; Abraham, A.; Harper, A.; Dunlap, P.V.; Benner, R.A. Biogenic amine production by and phylogenetic analysis of 23 Photobacterium species. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81(8), 1264–1274. [CrossRef]

- Kämpfer, P. Acinetobacter. In Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology, Batt, C.A. Tortorello, M.L. Eds.; Second edition Academic Press: Oxford, 2014; pp. 11–17.

- Guan, T.; Fu, S.; Wu, X.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y. Bioturbation effect of artificial inoculation on the flavor metabolites and bacterial communities in the Chinese Mao-tofu fermentation. Food Chem.: X 2024, 21, 101133. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).