1. Introduction

The European economy has long lost its global competitiveness, falling significantly behind in the race with countries like the US, China, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and others. In recent years, we have witnessed a kind of technological catch-up in the area of key innovations (fundamental scientific discoveries) introduced in the US in the previous decade, such as e-commerce and online retailing, with the main aim of reaching as many customers as possible. The digital sector stimulates growth, creates fundamentally new types of jobs, and generates huge positive spillovers. From PCs, the internet, digital platforms, 4G/5G, IoT, smartphones, and cloud services to artificial intelligence (AI), the most significant technological breakthroughs of the last few decades have been dominated by the ICT sector. In the new environment, the development of regions and individual countries is based on a new type of economy based on information, knowledge, new technologies, and the degree of their successful implementation in the management of economic, managerial, social, and administrative processes. Therefore, we could find a direct link between the development of the ICT sector, the generation and accumulation of know-how, the diffusion of knowledge and new technologies, investments in R&D, manufacturing, and the economic development of individual countries and regions.

ICT has been the most innovative area of technology in the last few decades. Hence, it is a key endogenous and exogenous factor for regional development and should be a priority in governance programs and policies. The functions of generative AI create an opportunity to accelerate innovation in other sectors.

Since the emergence of computing and microprocessors in the mid-1970s, computers have made inroads into planning and process management, including urban and regional development. Initially in the form of GIS systems for cartography [

1], then for the implementation of information systems in databases of population numbers, education, health levels, macroeconomic indicators, and indices, and today in the form of artificial intelligence (AI, AI) [

2]. Theories and ideas about the existence of non-artificial intelligence date back only to the aftermath of World War II, often as secret military experiments.

The growth rate of IT services value added is almost twice the growth rate of the world economy, outpacing all other sectors over the past two decades, based on information in the Trade in Value Added (TiVA) dataset. These digital services disproportionately benefit lower-income groups [

3]. Value added in ICT manufacturing and ICT services is highly concentrated in high-income economies, and concentration has increased further in the last decade. China and the US account for more than half of global value added in both sectors. In addition, the six largest economies account for 80% of global value added in ICT manufacturing and 70% in ICT services. Since 2010, these shares have increased further as economies of scale and scope, network effects, and the characteristics of the ICT sector have reinforced the dominance of the world’s leading economies. Between 2000 and 2020, the intensity of IT services in the financial sector (fin-tech) has barely increased in low- and middle-income countries, while it has doubled in most high-income countries and is now a major part of credit and payment services.

2. Materials and Methods

When researching the impact of AI geographically, it is common to distinguish between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom [

4]. In such research, knowledge can be defined as an intangible asset in the form of information that helps solve a problem, and wisdom is the use of accumulated knowledge and know-how. The so-called DIKW pyramid (Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom) can be seen as a key concept in computing and AI. Many authors argue that a knowledge-based system is based on the assumptions that:

(a) the problem can be clearly defined and is well-constrained by specifying the parameters of the algorithm;

(b) the relationships between the factors or elements of the problem are known and be expressed explicitly by setting variables in the algorithm;

(c) problem-solving methods can be formulated, and

(d) experts agree with the decisions, i.e., causal relationships are clearly defined [

5].

In semantic networks [

6], reasoning is like finding a pattern. Davis et al. consider “What is knowledge representation?” from a somewhat abstract, often philosophical point of view, based on five different roles: (i) a substitute or proxy for the thing itself (intelligence-artificial intelligence), (ii) a set of ontological commitments, (iii) a fragmentary theory of intelligent reasoning (algorithms), (iv) a means for pragmatically efficient computation, and (algorithm optimization) (v) a means for human expression, i.e., i.e., a language in which we say things about the world (reality programming) [

7,

8]. In conducting the comparative analysis of the application of AI as a tool for creating regional development models, traditional scientific methods for regional geography were applied. With their help, we can correctly answer the questions thus posed in the introductory part of the scientific article. First of all, we need to clarify what is the application of AI for the development of industry in terms of labor productivity, improving the qualities and education of the workforce, respectively, and raising incomes. That is, the marginal utility of such technologies is related to the multiplier effect in the context of systems analysis.

In this study, a combination of inductive and deductive methods, centripetal methods including cartographic method as private, scientific, geographical methods, and statistical and comparative analysis as general scientific unified methods were applied to conduct regional studies. The final step of the research is correlation analysis conduction. Induction and deduction help to explore general patterns in the application of AI and specific private cases to test the truth of hypotheses stated in research problems. The authors use data from Eurostat for 2021-2023.

The petrographic method is used to identify the location of innovation generation centers and the enabling conditions in the region for technology diffusion. That method of identifying central locations focuses on the geographical and economic factors in which certain regions have environments more conducive to the deployment and use of AI. The use of cartographic and statistical methods serves to visualize and quantify the parameters of the models for the application of AI in the governance process of different regions. This allows a comparative analysis of the readiness and extent of AI implementation in different areas of spatial planning and regional development.

The main research objective is a geographical and spatial analysis of the geospatial relationships between sustainable development, and local and global innovation. In this context, the authors explore how regional development is influenced by AI adoption and technology diffusion. The main task we aim at in the context of regional geography is a broader-scaled understanding of the role of innovation from the traditional innovation literature and a reformulation of the theory of the innovation environment (the innovation milieu) developed in the late 1980s and 1990s in France by Polanyi and Granovetter, complementing the ideas of Lundvall. The impact of AI in a very short period also completely changed the concept of regional development and all localization theories, among others, environmental aspects and sustainability. To explain the new realities, Roberto Camagni presents an overview of the scientific trajectory of the GREMI approach and proposes a new conceptual perspective related to sustainability issues [

9]. It questions the validity of territorial innovation models, such as the “classical” innovation environment approach and regional innovation systems, for understanding sustainable development in the era of global markets and hypermobile factors of production and consumption.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis and Systematization of the Theory Framework

In the scientific literature, the issues of AI and its role in spatial planning have been little explored, except by Zaborovskaia and Toffler, but only at the economic level to stimulate innovation, which is used much more in urban planning when delineating economic cores [

10,

11]. In the context of regional geography, the problem of spatial organization through AI is scarce due to the lack of regional and field studies that reveal the impact of this innovation on the planning and management of spatial systems of different scales.

Despite the rapid development of AI and the expansion of the spectrum of practical applications, scientific publications and research on the impact of the technology lag compared to the generative super novel value of locational solutions to complex problems related to planning and modeling of regional development. In this line of thought, geography and economic theories experience a strong need for transformation and adaptation to the new realities in which, according to Schumpeter in

“The Theory of Creative Destruction,

” the end of the old paradigm is very near and its foundation should be reformatted or completely redefined. In the era of Kondratie

v’s sixth

“ L

” wave in economics, AI necessitates the definition of new methods and research methodologies due to the analysis properties of large databases associated with accurate forecasting [

12]. The applications of these methods will become increasingly common in modeling and programming for the development of spatial systems. They are capable of challenging the pure theories of the early 20th-century standards and basic economic regularities. This paper will discuss three important dimensions in the development and application of AI for regional policy in the form of knowledge management and diffusion between regions for policy reasoning and machine learning. The applications of the literature in this research problem can be identified mainly in the following aspects:

AI in regional policy and urban planning: create opportunities for research and studies on the applications of AI in smart cities, urban analytics, and decision-making systems in regional governance;

Technological barriers to the implementation of AI: Conducting the literature review at the beginning of the study revealed several barriers to the implementation of AI, such as a lack of statistical databases at low territorial levels (districts, municipalities, urban areas) and several other constraints to the development of digital infrastructure. Existence of regional disparities and imbalances in the readiness to implement and apply AI.

The role of innovation hubs: A review of studies and research related to theories of diffusion of innovation and how central locations (e.g., innovation hubs and hubs) stimulate regional technology diffusion and spatial diffusion. The basis of these concepts refers to the works of Feldman and Asheim & Gertler related to the geography of innovation [

13,

14]. All are directly related to the pure localization theories of Christaler, the locational theories of Hagget and Chorley, Krugman, and Fujita on the dispersion of growth factors across different scales of territorial units [

15,

16,

17,

18].

The digital age of intangible knowledge, beginning in the late twentieth century, in which the prism of time is a complex and dynamic variable in which time and space are perceived as significant processes for socio-economic geography with a territorial dimension. Undoubtedly, the intangible assets associated with AI are manifested in terms of the same two variables that reveal the dynamics of social relations. According to Bauman, these relations are characterized by polyvalence, mobility, and diversity [

19]. Diversity naturally develops competition and facilitates processes such as globalization, digitalization, and regionalization. The levels of difference and synergy between the constituent elements of systems influence the cyberspace of quantum computers and generative artificial intelligence in different ways. Consequently, they also change the environmental conditions in which AI develops and influences properties often defined as self-programming and directly on the property of

“self-organization

” of systems.

The interest in the topic is mainly driven by Castells and Toffle

r’s concepts of network societies and Polanyi and Granovette

r’s knowledge establishment through investments in specific locations with specific environmental factor conditions. These factors of localized knowledge, transformed into intangible assets and innovations, act simultaneously as an exogenous and endogenous factor of territorial development. In addition, Westlake and Haskell reveal the symptoms of the increasing circular influence of intangible asset AI on the global future [

20]. According to them, social integration takes place with the power of the links related to information and knowledge transmission that impacts the development of the region. Therefore, intangible assets and knowledge in the form of databases have a direct impact on regionality, territorial differences, and localization. As a consequence, the establishment of AI fits into the theoretical, conceptual essence of regional geography, creating conditions for the definition of new locational theories about the development of technology and know-how. New interpretations in socio-economic geography are associated with the new category of

“intangible assets (resources)

” derived from localized knowledge and the factors that condition its development (research centers, science laboratories, co-working spaces, innovation parks, ICT centers, etc.).

Nowadays, regional geographic research should focus on the search for scientific explanations of the dynamics of processes such as immaterial capitalism, artificial intelligence, circular economy, decentralization, mobility, informal economy, social networks, Internet of Things, machine learning, deep learning, etc [

21,

22,

23]. The global accumulation of localized knowledge, military, capital, or innovation potential is fundamental to the development of the world. Therefore, competition between leading countries is concentrated on the accumulation of new knowledge based on which to develop competitive advantages.

The advancement and dispersion of artificial intelligence create incentives in developed countries for policymakers to explore the potential of the technology to improve regional and urban planning in terms of reducing socio-economic disparities, infrastructure challenges related to locational decisions, and allocation of different types of resources. In this context, AI is used for processing geospatial databases [

24]. Distributive data processed through algorithms improves the accuracy of predictive and locational analysis [

25,

26,

27]. Thus, they are up to optimization of decisions, policies, and measures. Therefore, AI computing can serve as a tool for spatial organization and optimization of regional development by creating new governance models.

Despite process optimization, the new functionalities of applying AI in regional politics are accompanied by several obstacles, from technological limitations to ethical considerations and concerns about privacy and the individual. This study reveals the geographical distribution within the EU vis-à-vis the US and China, the technological barriers and potential solutions that AI can offer, and the role of AI in promoting and implementing sustainable regional policy.

AI-generated models represent a self-programming representation of reality. The study of dynamics in this reality reveals the spatial variations of existing processes and phenomena in self-organization by the method of evolutionary theory of geography [

28]. In this context, Spatial patterns created by AI can play a key role in clarifying several important locational and urban issues related to the design of policies for the management of regional development. These models should seek answers and infer patterns concerning the location of economic activities, population distribution and dynamics, the size and distribution of cities, and other issues with a spatial dimension, providing answers to the following questions:

“ Why, Where, and How ?

” [

28,

29].

According to Rifkin, in

“a wired world,

” geography matters more than ever. In geography today, little is said about intangible assets and AI and their impact on the organization of space. Regional dimensions of the extent of the influence of factors are important because they alert to the problems of future development [

30]. The growing of intangible capital generated by AI through accumulated knowledge serves as a hypothesis that firms (enterprises) that operate only in a particular territory(location) have fundamental strategic disadvantages and lower levels of competitive advantage, such as firms in Bulgaria and countries with similar economic profiles of developing countries with economic systems in transition [

31].

In the context of intangible assets and the diffusion of innovation, a region can be defined as smart, the result of the evolution of a learning region that absorbs know-how and technology and gradually becomes one that generates innovation and technology [

32,

33,

34]. A smart region can be defined as a spatial unit fully covered by a digitized layer of data and information on the state of the various natural, social, and economic components. Their qualitative and quantitative state has the main purpose of panning cities according to functions and implementing a regional policy that serves to manage and organize regional development. In the mentioned digital layer (layer) can be found various distributive GIS data on natural elements and large databases related to economic development. This type of data can be visualized in the form of a 3D model, in combination with the application of the Internet of Things and other blockchain technologies through artificial intelligence, various solutions can be defined in the reasoning for policy decisions relevant to the development and management of a specific territory [

35,

36,

37]. Therefore, it is necessary to point out in the text several examples related to urban planning that can have a synergetic effect in terms of components at the regional level.

Batty, in his research, links several studies on the role of AI in the governance theory of smart cities [

38]. Other authors, such as Bisen, explore the role and impact of CCTV applications as tools that help law enforcement monitor public order compliance [

39,

40]. This type of digital system can be used to organize car parking and be used for traffic management. In another aspect, collecting data on the environmental footprint of equivalent residents can serve as a tool and develop a system for waste management, disposal, and recycling. According to Kumar, there are various use cases of AI-driven technologies in the smart city, from maintaining a healthy environment to improving public transportation and safety [

41]. And adds that by using AI and machine learning algorithms, the city can implement more targeted urban planning policies through smart traffic management solutions to ensure that residents get from one point to another as safely and efficiently as possible [

42].

Geographically and regionally, Thakker et al. applied AI to flood monitoring by screening gullies and catchments associated with surface runoff distribution and drainage in key flood-prone areas [

43]. The use of these types of digital models in the development and implementation of policies related to climate change impacts and consequences is an important aspect of any flood, fire, drought, and extreme weather monitoring solution. Recently, Gao introduced the concept of Geospatial Artificial Intelligence (GeoAI), which serves to regroup all attempts to use AI not only in the fields of GIS but also in urban and regional planning by developing different models based on which to define priorities for regional policy [

44].

Sustainable innovations such as AI are characterized by a large amount of financial resources and capital costs to operate. There are a variety of business models based on AI that include supply (e.g., eco-technologies) on the one hand and demand (e.g., new needs and new forms of consumption in a region) on the other. Sustainable innovation is distinguished along four ’dimensions’: product-oriented, institution-oriented, flagship-oriented, and area-oriented innovation. These dimensions differ not only in territorial scope but also in innovation profile, focus on sustainability, purpose, actors, and mode of coordination. This framework has been used to classify the case studies in the research assignments but appears to be somewhat ad hoc and not based on a more coherent theoretical foundation. For example, the ’flagship-oriented’ dimension of innovation may have been included to integrate such cases, not because flagship orientation is a necessary dimension of sustainable innovation, which covers a very broad and heterogeneous field of topics. From AI-based models for photovoltaics and sustainable finance in Switzerland, green technology construction KIBS in Germany and China, urban renewal and redevelopment projects in Lisbon and Ile-de-France, to sustainable tourism in Alpine regions, (inter)regional networks in Rome and the Atlantic region of France, smart city operating systems in the north of Portugal, a water campus focused on sustainable water technologies in the Netherlands, to changes in regional production systems in the Basque Country and Japan. All of these share certain aspects of sustainability and involve explorations of specific local industries with the multilocational or global perspective of AI modeling. This concept is broadly applicable to the studies of territorial transformations and restructuring as well as “flagship projects” in the context of regional development sustainability. Some of these illustrate very well the new characteristics of innovation environments (milieu), namely, the global-local “anchoring” of resources and innovation, the symbolic dimension and demonstration nature of innovation, the wide diversity of actors that goes beyond the traditional “triple helix” of firms, knowledge organizations, and policy actors, which includes consumers, media, civil society, and NGOs, etc.

Most of these case studies are interesting, but they are not unified in a common theoretical scientific framework, as they are quite diverse in terms of the topics, concepts, and methodologies used. Furthermore, they relate differently to the framework and issues raised in the introduction, with some being more strongly related to others. Roberto Camani gives an excellent overview of the development of the GREMI approach, including ideas for a new environmental perspective based on new technologies and innovation.

3.2. Results

In conducting the comparative analysis of the application of AI as a tool for creating regional development models, traditional scientific methods for regional geography were applied. With their help, we can correctly answer the questions thus posed in the introductory part of the scientific article. First of all, we need to clarify what is the application of AI for the development of industry in terms of labor productivity, improving the qualities and education of the workforce, respectively, and raising incomes. That is, the marginal utility of such technologies is related to the multiplier effect in the context of systems analysis.

In terms of linear analysis, the relationship of AI to the technological specialization of regions is related to the diffusion of knowledge, innovation, and know-how that AI itself generates and represents. The abstract notion of generative AI is one step towards process autonomy in industry and economic governance. As a result, the generation of Big Data-based regional development models has greater forecast accuracy. On the other hand, the modeling and precision of goal setting becomes a higher form of political and geopolitical will to develop the territory and geospatial in the form of a self-organizing system. To reveal the role of AI in the development of territorial systems, we present the application of AI in industrial development in the aspect of technology deployment in various production processes in enterprises.

According to Eurostat, in the past year 2023, around 8% of enterprises in the EU with 10 or more employees and self-employed persons use at least one of the following types of AI [

29]:

- technologies for written language analysis (text mining);

- technologies for converting spoken language into a format readable by machine software (speech recognition);

- written or spoken language generation technologies (natural language generation);

- technologies for identifying objects or people based on images (image recognition, image processing);

- machine learning (deep learning) for big data analysis;

- technologies to automate various work processes or to support decision-making (automation of robotic processes using AI-based software);

- technologies that allow machines to physically move by observing their surroundings and making autonomous decisions based on information about their environment gathered by sensors and sensing devices.

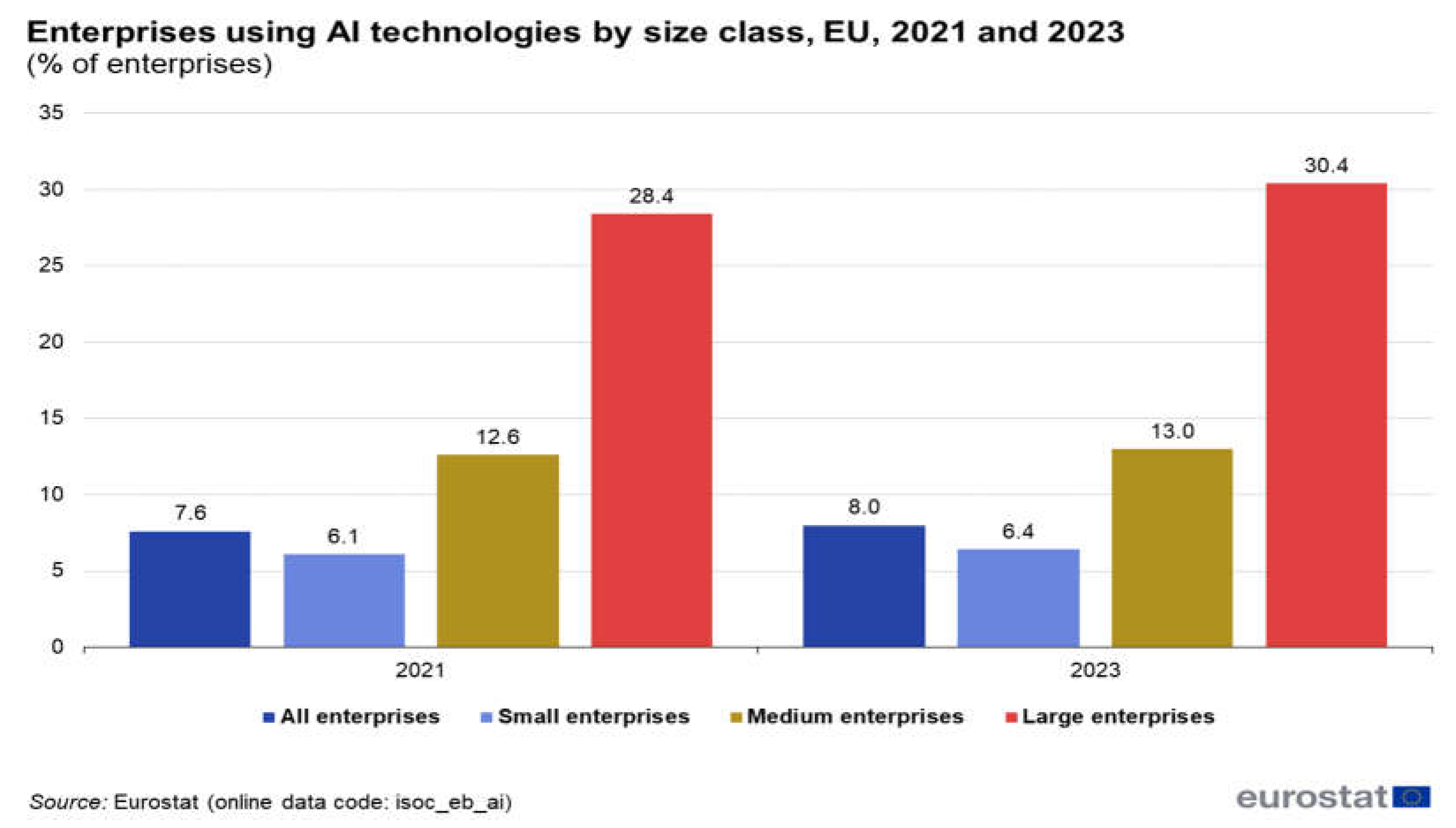

Compared to previous surveys, the use of AI-enabled technologies has increased slightly by 0.4 percentage points since 2021 (

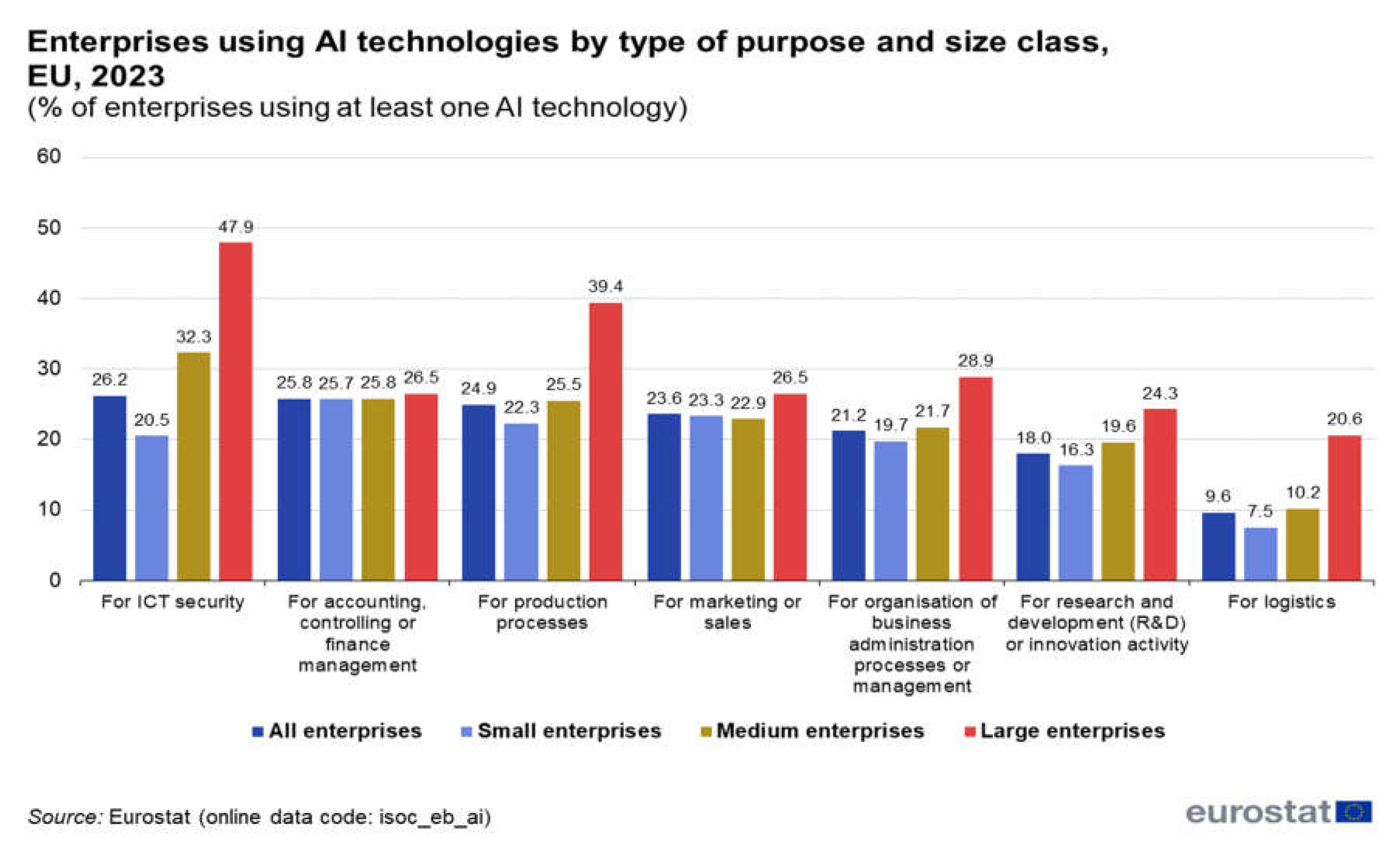

Figure 1) compared to the previous 2 years. From the analysis of the

Figure 2, large enterprises use deployed AI technologies more compared to small and medium enterprises. In 2023, 6.4% of small enterprises, 13% of medium enterprises, and 30.4% of large enterprises will use AI for various operations in production. This difference can be explained, for example, by the complexity of implementing AI technologies in the enterprise and the significant financial resource requirement to maintain such type of systems, economies of scale (i.e., enterprises with larger economies of scale may benefit more from AI due to more revenue as a result of automation and outsourcing to sub-suppliers) or cost (investments in AI and their maintenance by specialist engineers may be more affordable for large enterprises).

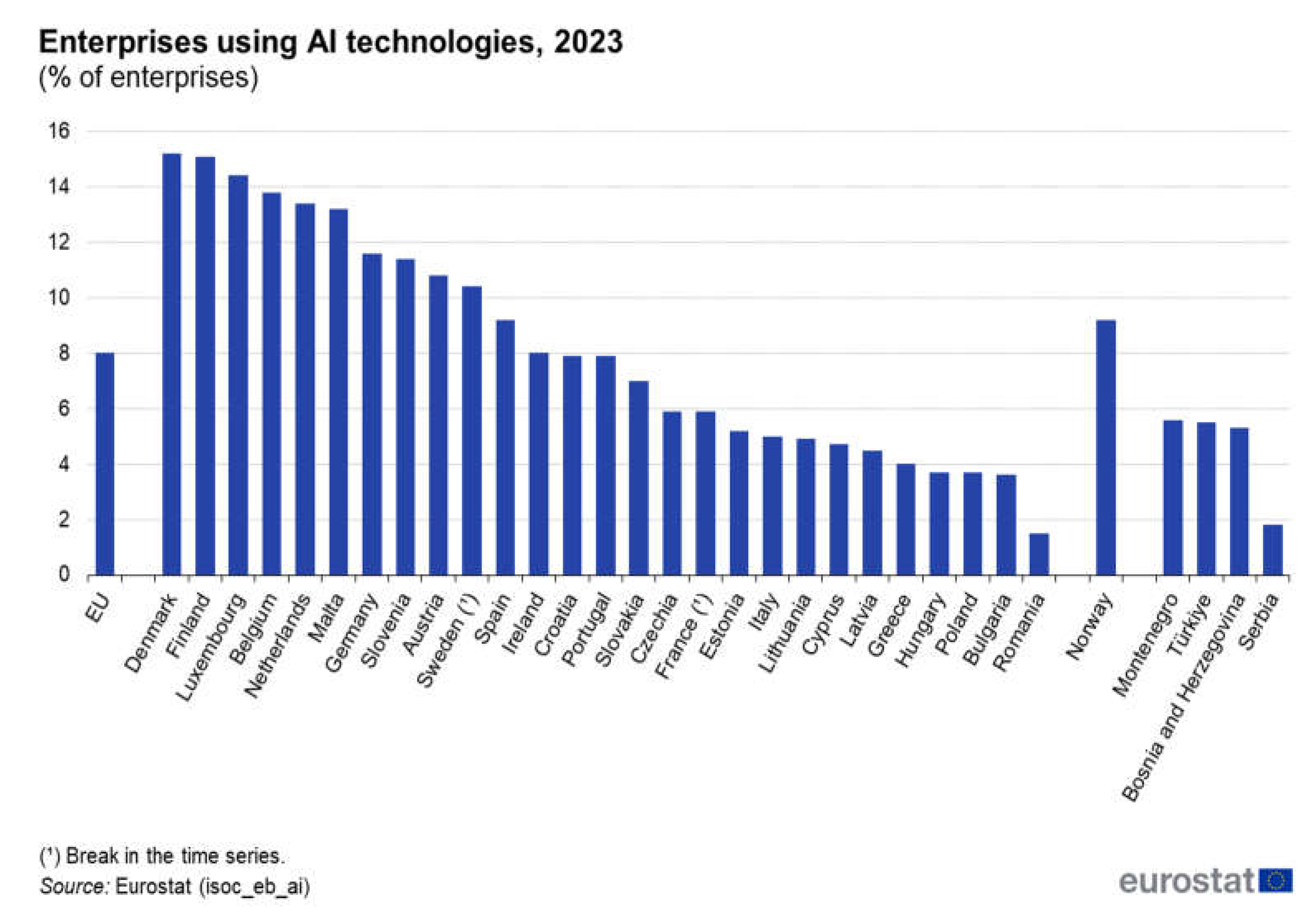

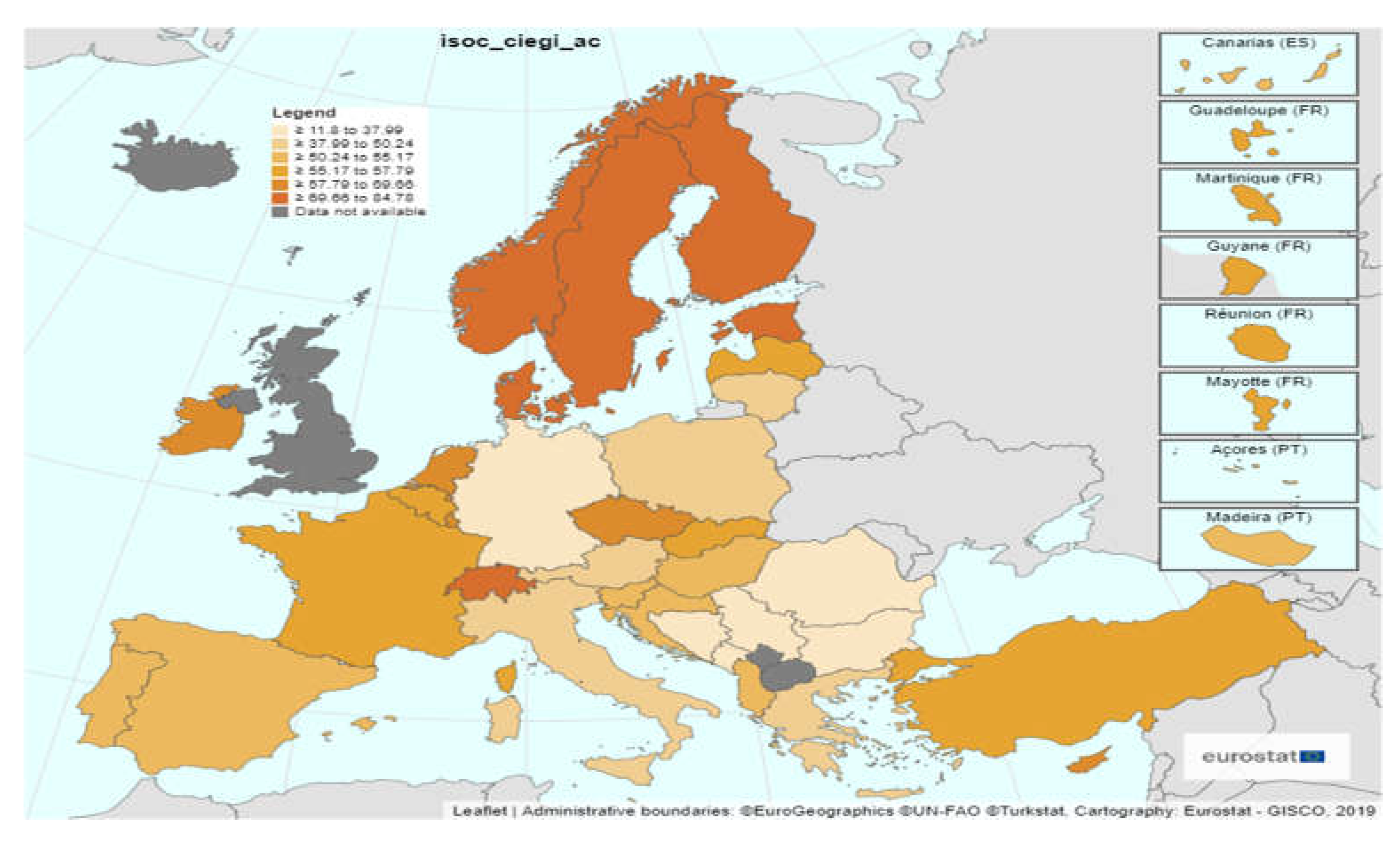

A comparative analysis of enterprises using at least one AI-enabled technology in EU countries (

Figure 2) reveals that the share of enterprises using AI ranges between 1.5% and 15.2%. The highest share of enterprises with AI is recorded in Denmark (15.2%), followed by Finland (15.1%) and Luxembourg (14.4%), while the lowest shares are recorded in Romania (1.5%), Bulgaria (3.6%) and Poland and Hungary(both 3.7%).

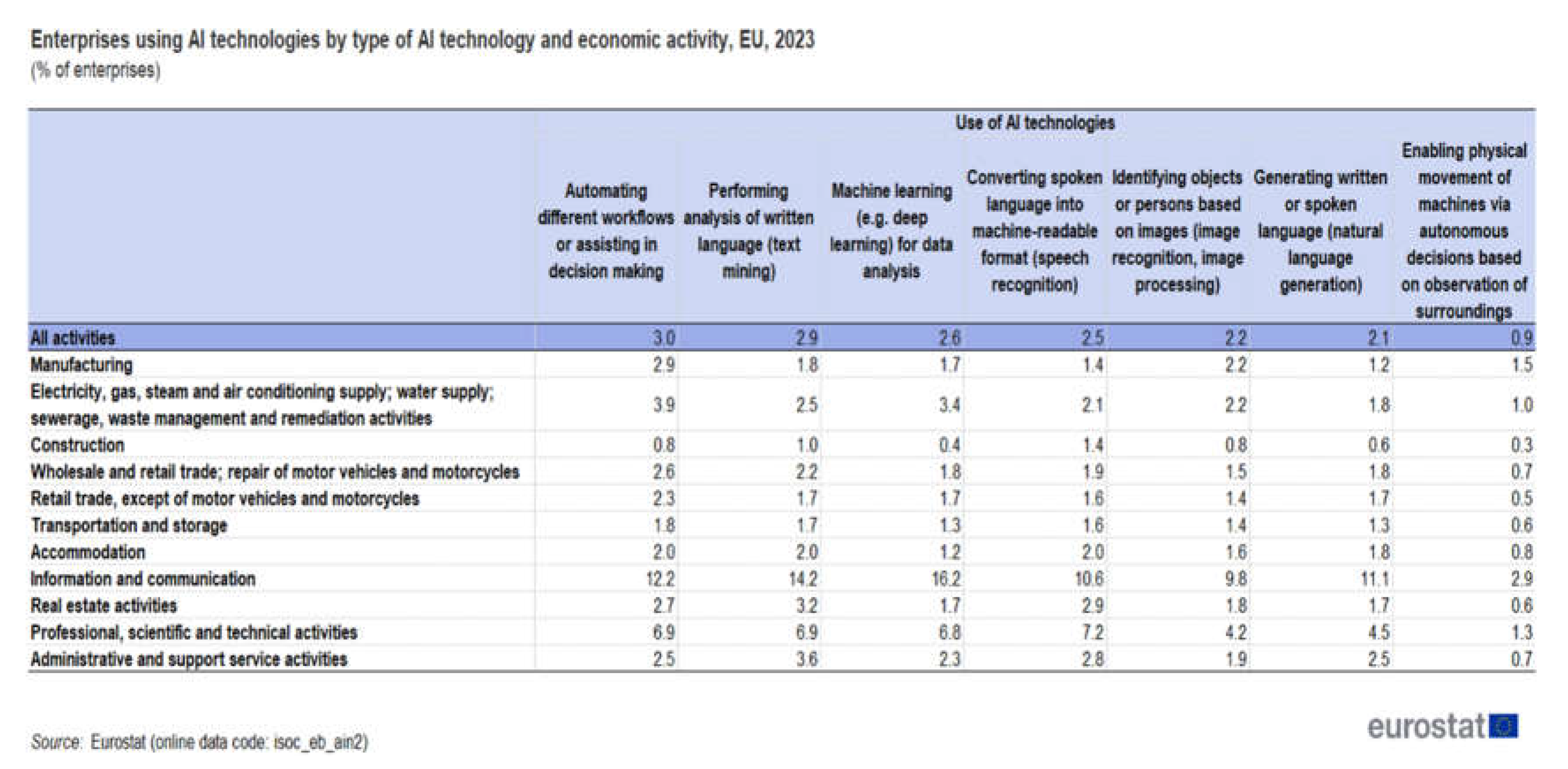

The data in the diagram (

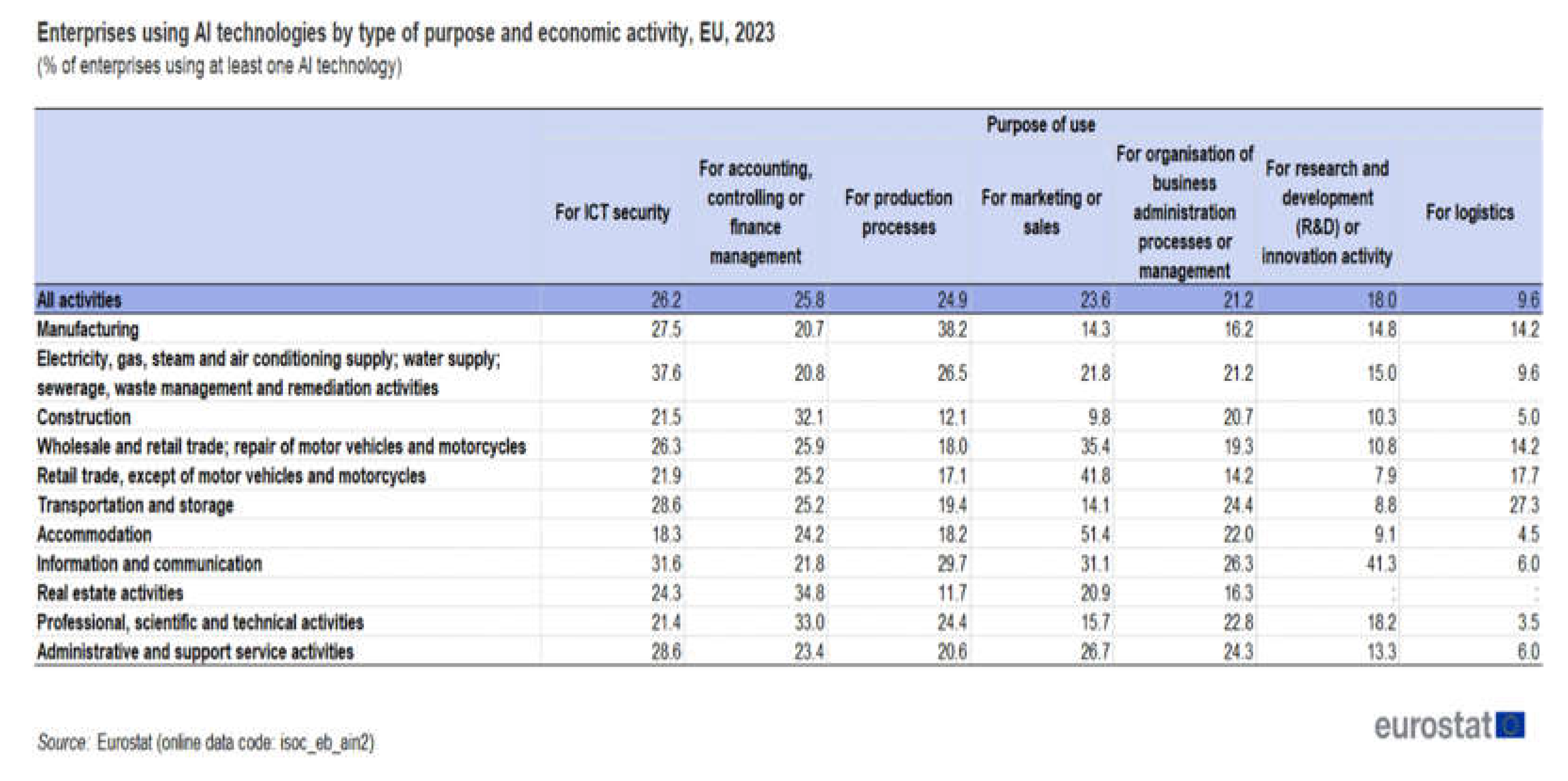

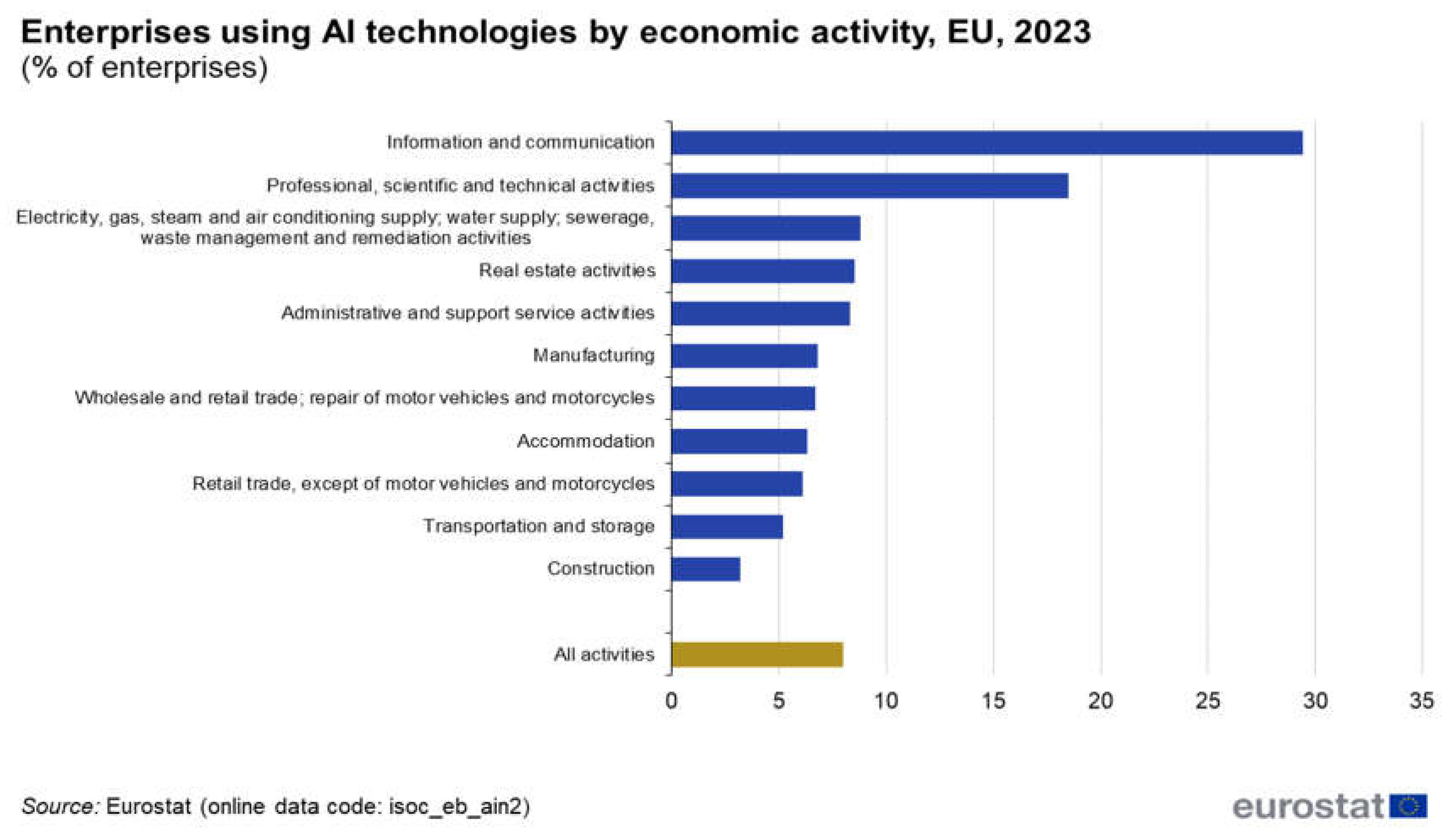

Figure 3) shows that in some economic activities, artificial intelligence is used much more than in others. Therefore, AI is still applicable only to certain activities. In 2023, the information and communication sector (with 29.4%) and professional, scientific, and technical services (with 18.5%) stand out with the highest share of enterprises using AI. In all other economic activities, the share of enterprises using AI is below 10%. This ranges from 8.8% (electricity, gas, steam, air conditioning, and water supply) to 3.2% (construction).

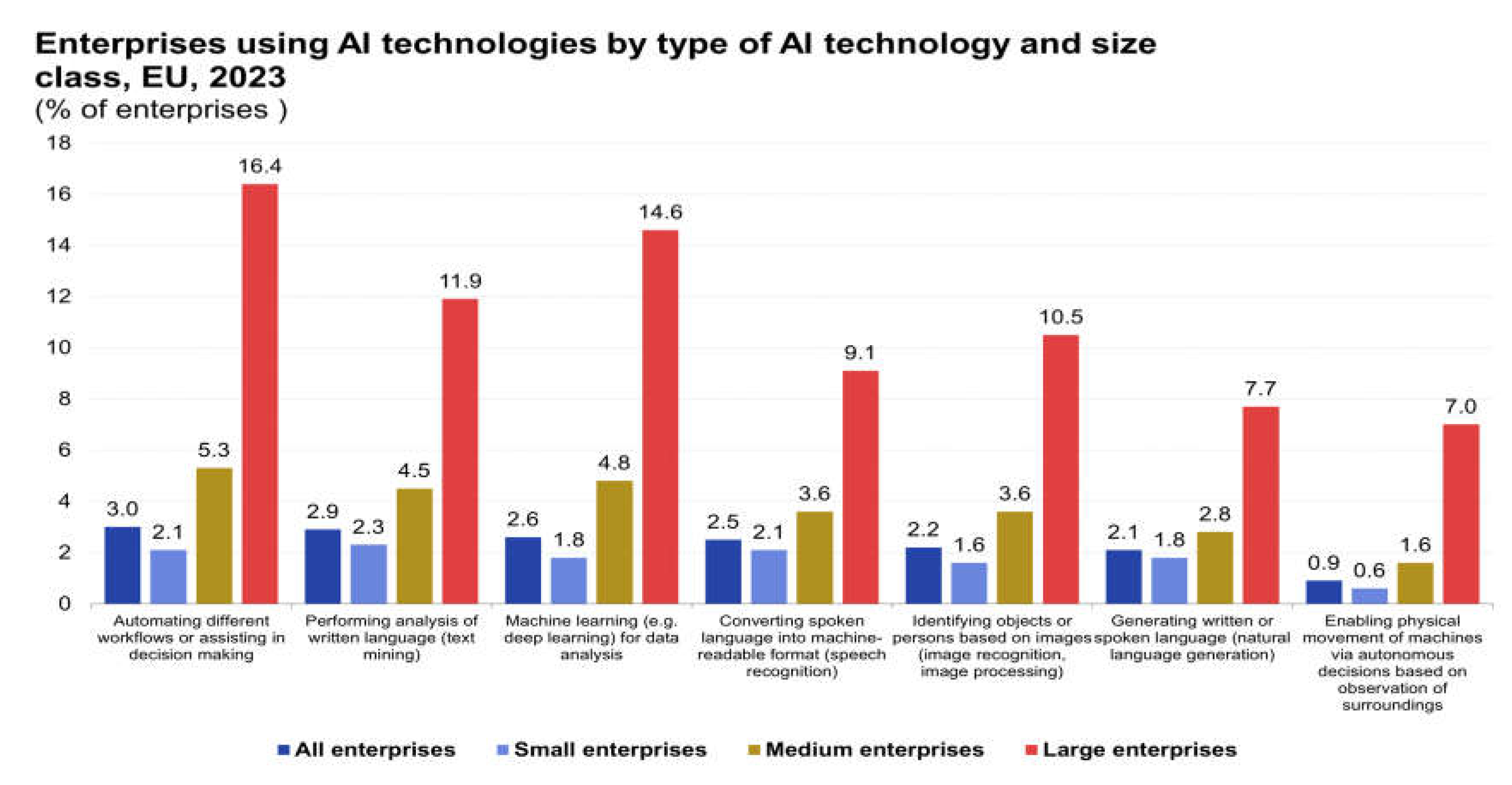

Industrial enterprises in the EU that use different types of AI technologies. It is clear from the types of AI-enabled technologies presented in

Figure 4 that there is no dominant AI-related technology. The AI technologies that are more common are mainly in the aspect of automating different work processes or supporting decision-making (e.g., AI-based software for robotic process automation). In 2023, this type of technology is used by about 3% of enterprises. The application of this type of know-how mainly consists in:

analyze written language (i.e., text mining), - 2.9% of enterprises;

machine learning technologies (e.g., deep learning) for data analysis;

technologies for converting spoken language into a machine-readable format (speech recognition);

technologies for identifying objects or persons based on images (image recognition, image processing) and ;

written or spoken language generation (natural language generation) technologies are used by between 2.6% and 2.1% of enterprises.

Technologies that allow machines to physically move by monitoring the environment and making autonomous decisions (e.g., autonomous vehicles) are used by less than 1% of enterprises (0.9%). Although not all industries use a predominant AI technology,

Figure 4 shows a different situation relative to the size of enterprises, in particular large enterprises. The most commonly used AI technologies are those that automate various work processes or support decision-making, with 16.4% of industries, followed by machine learning for data analytics (14.6%). The least used AI technologies are those that enable the physical movement of machines through autonomous decisions based on environmental monitoring (7.0%).

Table 1 presents the different types of AI technologies according to economic activities. In the information and telecommunication technology sector, the highest share of enterprises using AI is recorded. The most commonly used technologies are machine learning for data analysis (16.2%), followed by text mining (14.2%). In professional, scientific, and technical services, speech recognition is slightly more commonly used than other AI technologies (7.2%), followed by text mining and AI technologies that automate various workflows or support decision-making (both 6.9%). In all other activities, the share of enterprises using specific AI technologies ranged from less than 1% to 3.9%.

Industry in the EU mainly uses AI software or systems for various purposes and technological operations. In 2023, a total of 26.2% of enterprises use AI technologies in the form of software or other types of ICT security systems (e.g., using machine learning to detect and prevent cyber-attacks), and another 25.8% for accounting, control, or financial management. Software or systems with embedded AI for logistics are used by at least only 9.6% of enterprises using AI technologies (

Figure 5). The purposes for which enterprises use AI-enabled software and systems vary according to their scale, technological readiness, and specialization.

The largest difference between small and large enterprises is recorded for those using software or AI systems for ICT security (47.9% of large enterprises, 20.5% of small enterprises), followed by those using them for production processes (39.4% of large enterprises, 22.3% of small enterprises) and those using them for logistics (20.6% of large enterprises, 7.5% of small enterprises. Enterprises adopt and adapt technology for different purposes depending on the economic activity. In the manufacturing sector, software or systems with AI are mainly used for production processes (38.2%), while software or systems with AI are mainly used for ICT security in the energy, gas, and water supply sectors (37.6%) and in the information and communication sector (31.6%).

Figure 6.

Enterprises using AI by type of use and size of enterprise in the EU.

Figure 6.

Enterprises using AI by type of use and size of enterprise in the EU.

The main use of AI is in the form of research and development (R&D) or innovation activities in the information and communication sector (41.3%). In such cases, enterprises use AI software or systems mainly for marketing or sales in the hospitality sector (51.4%) and in the retail sector (41.8%).

Table 2.

Enterprises using AI by type and economic activity at the EU level.

Table 2.

Enterprises using AI by type and economic activity at the EU level.

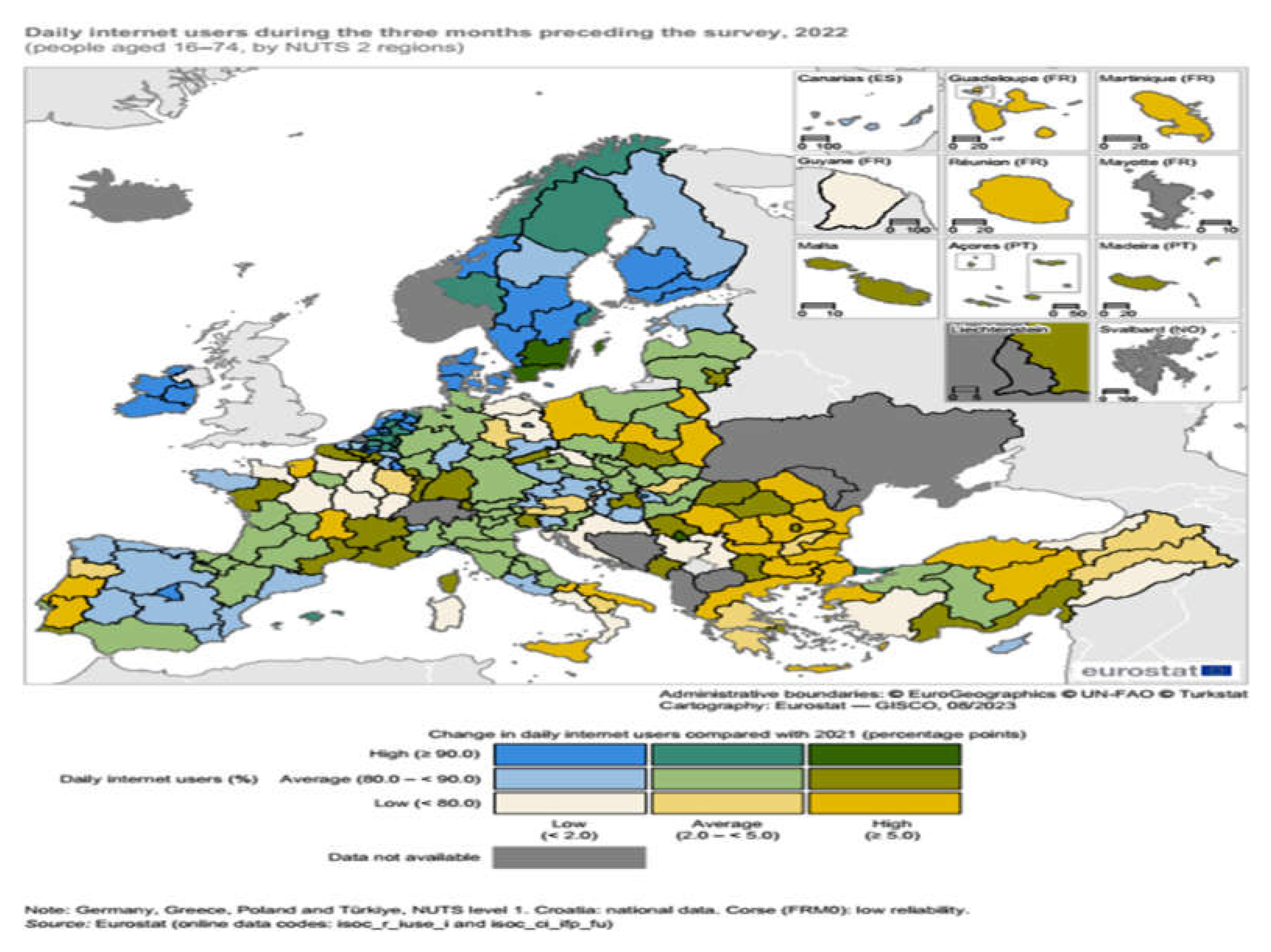

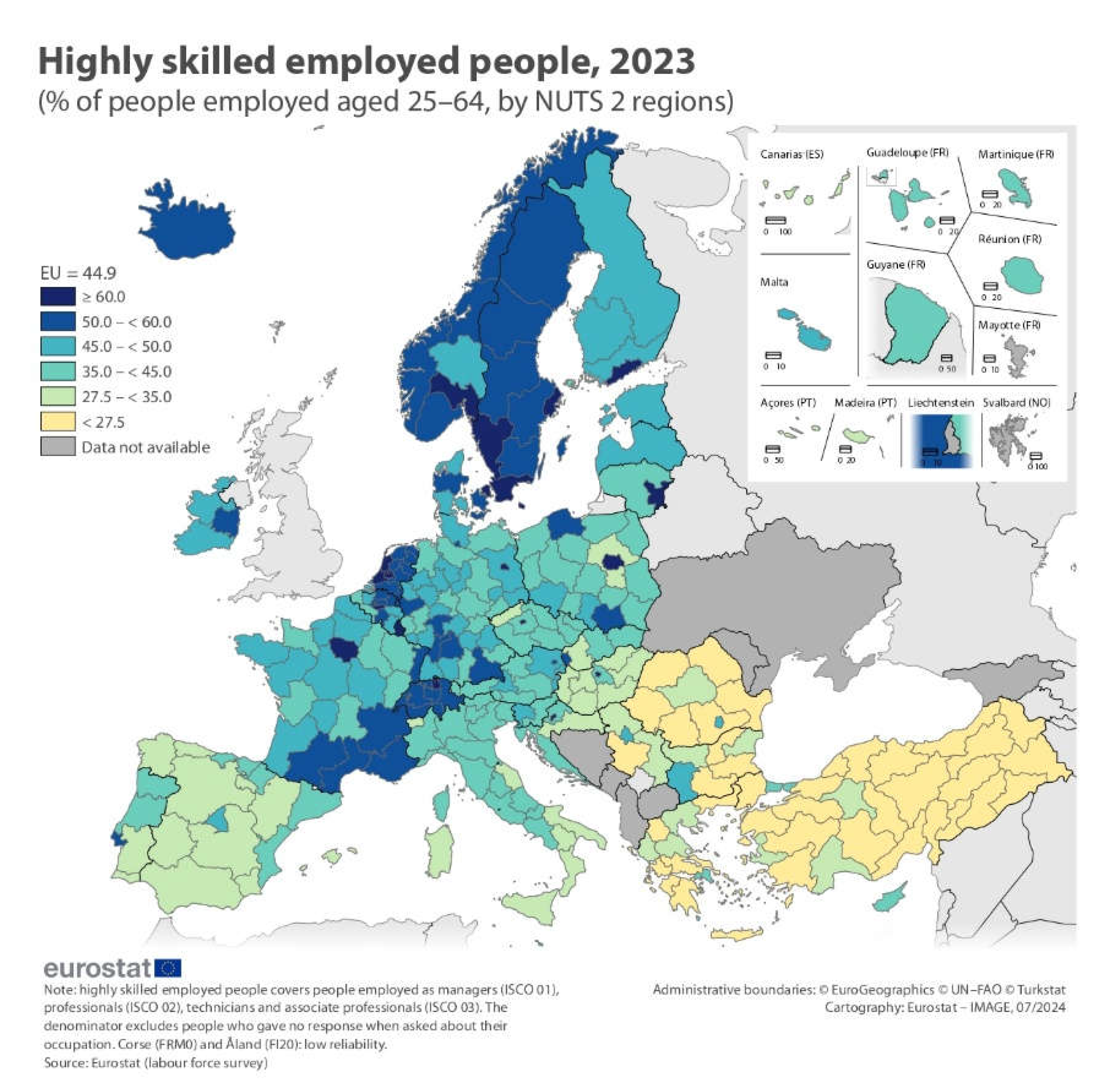

The technological level of European countries is not only expressed in the share of companies using new technologies and artificial intelligence but also in the percentage of highly educated people in the population of European countries. In

Figure 7 we see the countries that have a higher share of highly skilled employees. Logically, these countries use more innovation, new technologies, and artificial intelligence, which is reflected in the gross domestic product increases.

3.3. Correlation Analysis

Based on the spatial and economic analyses, the authors apply correlation analysis to examine the relationship between the gross domestic product produced in European countries and the share of the ICT sector on the one hand. On the other hand, the authors examine the relationship between the GDP produced and the level of education of the European population.

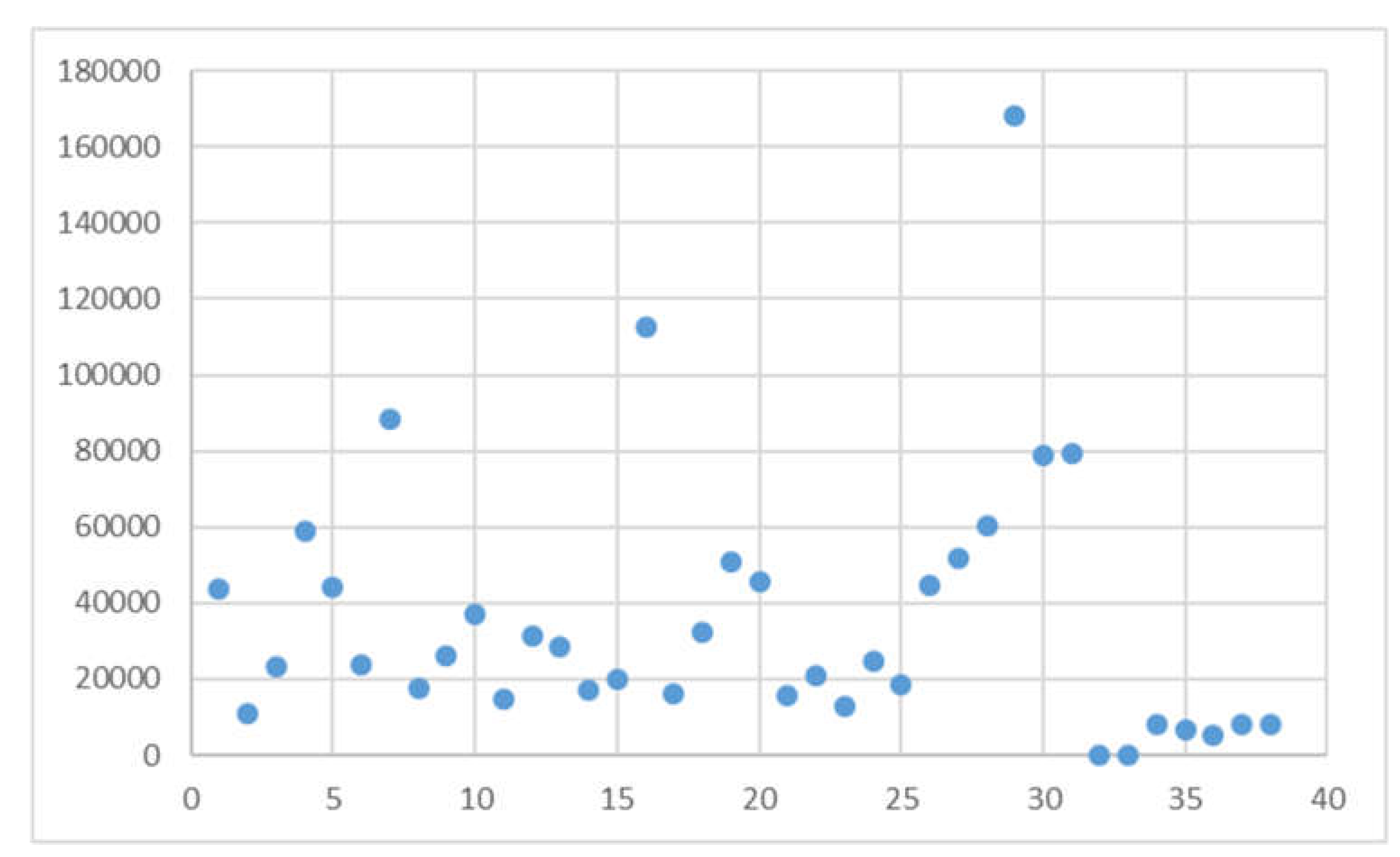

In

Figure 8 we see that there is a moderate relationship between the share of the ICT sector and the GDP produced. We can see that the share of this sector is small and this does not have a strong impact on the economic development of European countries. These results show that the deployment of artificial intelligence is still at a low level. Also, the technological level has a significant impact on the development of countries.

Figure 9 plots the degree of correlation between the level of education of the European population and the GDP produced in 2023. We can see that there is a correlation. The more educated the population is the more technological a European country can be and produce a higher GDP.

4. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

Today, people rely more and more on AI for many administrative procedures. In a governance and policy context, the development of e-government and e-administrative services offers a wide range of benefits to governments and the form of systems management, as well as to citizens, including greater efficiency and more timely services. One benefit, for example, is that it enables citizens to receive information from public authorities and administrative services at any time. According to the EU’s Digital Decade targets, by 2030, all key public services for businesses and citizens should be digitized and fully online. In 2023, 45% of EU citizens who used the internet in the previous 12 months used it to get information from public authorities’ websites, for example, on services, benefits, rights, laws, and opening hours. This share varies considerably between EU countries. In 16 EU countries, more than 50% of people have used such websites to get information, with Finland (83%), Denmark (73%) and Sweden (71%) leading this group. People of all ages use public authorities’ websites to get information. In the EU, however, the proportion is highest among 25-64-year-olds (47%), followed by 16-24-year-olds (40%) and 65-74-year-olds (36%).

Although some of the most tech-savvy countries are part of the EU or located on the European continent, Europe is generally lagging in the area of breakthrough (fundamental) digital technologies (

Figure 10). These technologies drive growth over the long horizon, pay dividends on capital expenditure for convergence between regions, and can be an indicator of the effectiveness of cohesion policy. Around 70% of foundational AI models have been developed in the US since 2017, and just three US “hyperscalers” account for over 65% of the global and European cloud market. Europe’s largest cloud operator accounts for just 2% of the EU market. On the other hand, quantum computing is poised to be the next big innovation, given the fact that some of the world’s top ten technology companies in terms of investment in quantum technology are based in the US and four in China. None of them are based in the EU, despite the technological advantages of the Netherlands, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Estonia.

Table 3.

Top 10 innovative economies in the world according to the Global Innovation Index 2024. [

46].

Table 3.

Top 10 innovative economies in the world according to the Global Innovation Index 2024. [

46].

| Location |

The 10 most innovative economies globally |

| 1 |

Switzerland |

| 2 |

Sweden |

| 3 |

USA |

| 4 |

Singapore |

| 5 |

United Kingdom |

| 6 |

South Korea |

| 7 |

Finland |

| 8 |

Netherlands |

| 9 |

Germany |

| 20 |

Denmark |

The lack of a targeted EU-level strategy on cloud computing is widening the inequality gap in terms of competitive technological advantage. This is determined by the nature of the technology, which needs continuous investment, economies of scale, and a large volume of skilled human resources. However, there are many reasons why Europe should not give up on developing its domestic technology sector, in particular, supercomputing and AI. First, EU companies must maintain a position in areas where technological sovereignty is required, such as security and encryption (sovereign cloud solutions). Second, the underdeveloped technology sector limits innovation performance in a wide range of related industries, such as pharmaceuticals, energy, automotive, circular economy, and defense. Third, artificial intelligence - and, in particular, generative artificial intelligence. It is an emerging technology in which EU companies and regional growth centers still have the opportunity to score a leading position in selected segments. For example, Europe leads in autonomous robotics, where around 22% of global activity takes place, and in AI services, where around 17% of activity takes place. However, innovative digital companies generally fail to scale up in Europe and attract funding, which translates into a huge funding gap later on between the EU and the US. In fact, in the EU, no company with a market capitalization of more than EUR 100 billion has been created from scratch in the last forty years, whereas in the US, all six companies with a valuation of more than EUR 1 trillion (Google, Amazon, Meta, Apple, X, NVidia) have been created in this period.

The limitations thus described are the result of the lack of a regional policy that takes into account the evolution of technology. This type of policy should be aimed at building regional scientific hubs and centers, stimulating scientific and educational institutions, and strengthening interaction between regional and local actors in the regional development process. This is why modern regional policy must make full use of AI in the process of resolving regional inequalities, overcoming the technological gap, and increasing European competitiveness.

5. Conclusions

This study attempts to determine the impact and potential of AI for the development of European regions. The authors consider the development and deployment of AI as a contemporary tool of regional policy. In this way, regional disparities can be bridged, urban planning can be optimized, and the technology gap can be reduced both within the EU and between the EU and the world’s most innovative economies. However, significant obstacles remain, especially for regions that lack a robust digital infrastructure. Policy interventions should focus on digital inclusion, fostering innovation hubs, and resourcing the implementation of AI. Future research could explore the longitudinal impacts of AI-based policies in different regional contexts and assess the social and ethical considerations associated with AI in public policy.

Based on the study, the authors reach important and interesting conclusions and results. The analyses show that the countries with the highest innovation index in the EU (i.e., those that spend more on R&D and implementation of new technologies) are the European countries that are characterized by the highest share of industries using AI in their economic activity. These same countries have the highest share of ICT industries in their economies. Territorial and geographical analysis of the distribution of technology industries in European countries and the use of AI shows that there is a clear concentration, which affects the economic growth and development of countries. As we know, high-tech industries are characterized by high added value. Such countries are Scandinavian (Denmark, Finland, Sweden), France, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, and outside the EU but in Europe, the UK. The diffusion of know-how, knowledge, new technologies, and AI has no well-defined patterns according to which it spreads territorially. But at the same time, geographical distribution is linked to investment activity, and this process can be managed within European countries and regions. Regional policy can play this role, which relates directly to the smart specialization strategy for EU regions.

The potential for using AI on the farm is huge. In this sense, countries can incorporate the development and deployment of AI into regional development strategies. In this study, the authors have attempted to demonstrate not just the role of AI in the development of states but that it can be seen as a contemporary tool of regional policy. In this regard, a major conclusion that emerges is that the limitations in the volume and spatial levels of data, the lack of digital infrastructure, and the high costs of implementation in some European regions are major obstacles hindering the integration of AI in regional policy, urban planning, and resource management.

AI is a promising and useful tool to address various locational problems in urbanism, such as reducing congestion through traffic management systems, waste management systems, mobile urban mobility services, and more efficient integration of urban transport systems and social services. On a wider territorial scale, technology can be applied to improve resource allocation in terms of recycling, sustainability in energy, and resource conservation. On the other hand, the digitalization of administration leads to the improvement of social services and the successful integration of horizontal policies that act on localities. However, to the previous conclusion, performance varies significantly across regions due to regional differences in terms of technological readiness, availability of capital expenditure, intangible resources (knowledge and software), and human capital.

Considering AI as a regional policy tool, central locations or innovation hubs have the potential to play a key role in advancing policies that stimulate the development of innovation, STEM centers, technology parks, and R&D based on planning and location choice through the use of AI-based models. Areas with existing high-level technological infrastructure and human capital availability benefit more readily from the deployment of AI and its application to regional development management, which strengthens the role of central locations with technological competitive advantage in the diffusion of technology impulses and diffusion.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, NTS; Methodology, NTS; Formal Analysis, NTS, MZ.; Investigation, MZ.; Resources, NTS.; Data Analysis, NTS, MZ.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, NTS.

References

- Baxter, RS. Computer and statistical techniques for planners. Methuen Press, 1976, p. 336.

- Laurini, R. Information systems for urban planning: a hypermedia cooperative approach. Taylor and Francis, 2001, p. 308.

- Brynjolfsson, E; Li, D.; Raymond, L. Generative AI at work. No. w31161. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023.

- Ackoff, L. From data to wisdom. Journal of Applied Systems Analysis, 1989, 16, no. 1, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Han, SY; Kim, TJ. Intelligent urban information systems: review and prospects. In: Kim TJ, Wiggins LL, Wright JR (eds) Expert systems: applications to urban planning. Springer, New York, 1990, pp 241-261.

- Sowa, J. F. Conceptual structures: information processing in mind and machine. Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.. 1984.

- Davis, F. D. User acceptance of information technology: system characteristics, user perceptions and behavioral impacts. International journal of man-machine studies, 1993, 38(3), 475-487.

- Laurini, R. Geographic knowledge infrastructure for territorial intelligence and smart cities. ISTE-Wiley. 2017, p.250.

- Camagni, R. Territorial capital and regional development: theoretical insights and appropriate policies. In Handbook of regional growth and development theories. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019. pp. 124-148.

- Zaborovskaia, O.; Babskova, O. The concept of knowledge management in the region as a basis of estimation of conditions of innovative activity. Machines. Technologies. Materials. 2018, 12, no. 9, 355–357. [Google Scholar]

- Toffler, A. The third wave. New York: Morrow, 1980, 544.

-

Schumpeter, Joseph A. Essays: On entrepreneurs, innovations, business cycles and the evolution of capitalism. Routledge, 2017.

- Feldman, Maryann P. “The new economics of innovation, spillovers and agglomeration: Areview of empirical studies.” Economics of innovation and new technology, 1999, 8, no. 1–2, 5-25.

- Asheim, B.; Gertler, M. Regional innovation systems and the geographical foundations of innovation.” 2005, 291-317.

- Christaller, Walter. “Beiträge zu einer Geographie des Fremdenverkehrs (Contributions to a Geography of the Tourist Trade).” Erdkunde, 1955, 1-19.

- Chorley, J.; Kennedy, B. Physical geography: a systems approach. 1971.

- Krugman, Paul. “The role of geography in development.” International regional science review, 1999, 22, no. 2, 142–161.

- Fujita, et.al. The Spatial Economy: Cities, Regions and International trade. Cambridge, 1999.

- Bauman, Z. “On glocalization: Or globalization for some, localization for some others.” Thesis Eleven, 1998, 54, no. 1, 37-49.

- Haskel, J.; Westlake, S. Capitalism Without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy. Princeton University Press, 2018.

- Harvey, D. Explanation in Geography. London: Edward Arnold, 1969.

- Badar, M.; Rahman, S. Machine learning approaches in smart cities. In: Studies in computational intelligence, MIDATASMART, 2020. Springer (in press).

- Bokolo, A. A case-based reasoning recommender system for sustainable smart city development. AI & society, 2021, 36, no. 1, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucetta, Z.; El Fazziki, A.; El Adnani, M. A Deep-Learning-Based Road Deterioration Notification and Road Condition Monitoring Framework. International Journal of Intelligent Engineering & Systems, 2021, 14, no 3. [Google Scholar]

- Laurini, R. Geographic knowledge infrastructure for territorial intelligence and smart cities.”, 2017.

- Abdelhameed, I.; Mirjalili, S. Mohammed El-Said, Sherif SM Ghoneim, Mosleh M. Al-Harthi, Tarek F. Ibrahim, and El-Sayed M. El-Kenawy. “Wind speed ensemble forecasting based on deep learning using adaptive dynamic optimization algorithm.” IEEE Access 9, 2021,125787-125804.

- Harbola, S.; Volker Coors, V. Deep learning model for wind forecasting: Classification analyses for temporal meteorological data. PFG–Journal of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Geoinformation Science, 2022, 90, no. 2, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Yang, Yi, Chen, J. Weichao Li, Zhisheng Huang, Wenyue Zhang, and Ling Peng. “Disaster prediction knowledge graph based on multi-source spatio-temporal information.” Remote Sensing,14, no. 5, 1214.

- Harvey, D. The right to the city.” In The city reader, 2015, Routledge, pp. 314-322.

- Antonelli, C. The economics of localized technological change and industrial dynamics. Vol. 3. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- Rifkin, J. The zero marginal cost society: The internet of things, the collaborative commons, and the eclipse of capitalism. Macmillan, 2014.

- Porter, M. Competitive advantage of nations: creating and sustaining superior performance. simon and schuster, 2011.

- Golubchikov, O.; Thornbush, M. Artificial intelligence and robotics in smart city strategies and planned smart development. Smart Cities, 2020, 3, no 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, R.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Corchado, J. Smart Technologies for Sustainable Urban and Regional Development. Sustainability, 2024, 16, no 3, 1171. [Google Scholar]

- He, B.; Bhatti, U. Smart cities and smart networks: AI applications in urban geography and industrial communication.” International Journal of High Speed Electronics and Systems, 2024, 2440122.

- Alahi, M.; Eshrat, E.; Sukkuea, A.; Tina, F.; Nag, A. Wattanapong Kurdthongmee, Korakot Suwannarat, and Subhas Chandra Mukhopadhyay. “Integration of IoT-enabled technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) for smart city scenario: recent advancements and future trends.”, 2023, Sensors 23, no. 11, 5206.

- Rashid, M.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Corchado, J. Smart Technologies for Sustainable Urban and Regional Development. Sustainability, 2024, 16, no 3, 1171. [Google Scholar]

- Szpilko, D.; Naharro, F.; Lăzăroiu, G.; Nica, E.; Gallegos, A. Artificial intelligence in the smart city—a literature review. Engineering Management in Production and Services, 2023, 15, no. 4, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. Inventing future cities. MIT press, 2018.

- Batty, M. Artificial intelligence and smart cities. Environment and Planning, Urban Analytics and City Science. 2018, 45, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisen, V. How AI can be used in smart cities: applications role & challenge.” Retrieved from Medium: https://medium. com/ vsinghbisen/how-ai-can-be-used-in-smart-cities-applications-role-challenge-8641fb52a1dd, 2020.

- Kumar, S.; Kochmann, D. What machine learning can do for computational solid mechanics.” In Current trends and open problems in computational mechanics, 2022, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 275-285.

- Ullah, Z.; Al-Turjman, F.; Mostarda, L.; Gagliardi, R. Applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in smart cities. Computer Communications, 2020, 154, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakker, D.; Mishra, B.; Abdullatif, A.; Mazumdar, S.; Simpson, S. Explainable artificial intelligence for developing smart cities solutions. Smart Cities, 2020, 3, no. 4, 1353–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S. Geospatial artificial intelligence (GeoAI). Vol. 10. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/digitalisation-2024.

- Available online: https://www.wipo.int/en/web/global-innovation-index/2024/index.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).