Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. VAERS Retrospective Analysis

2.3. AEFI Formula

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

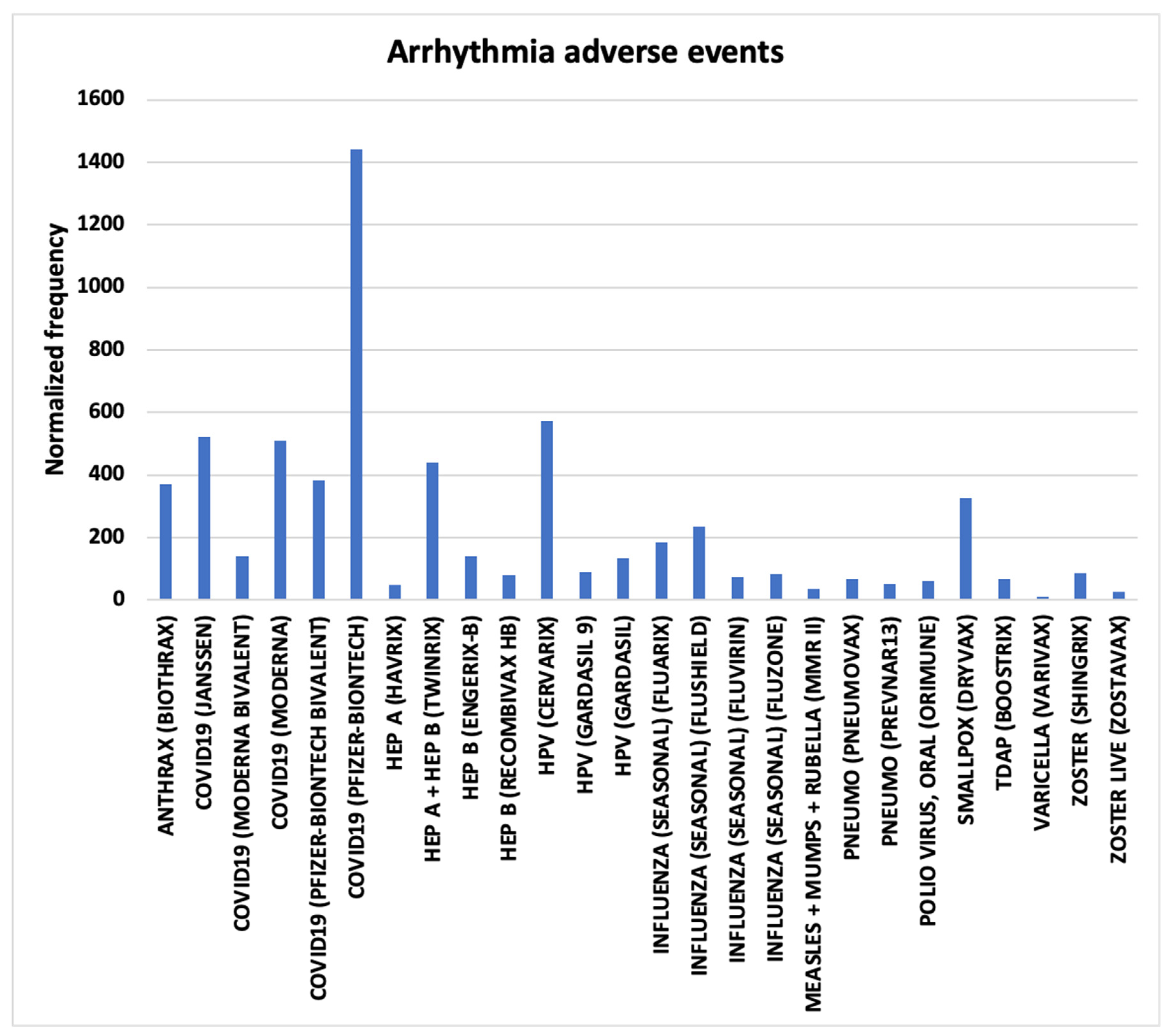

3.1. Arrhythmia AEs

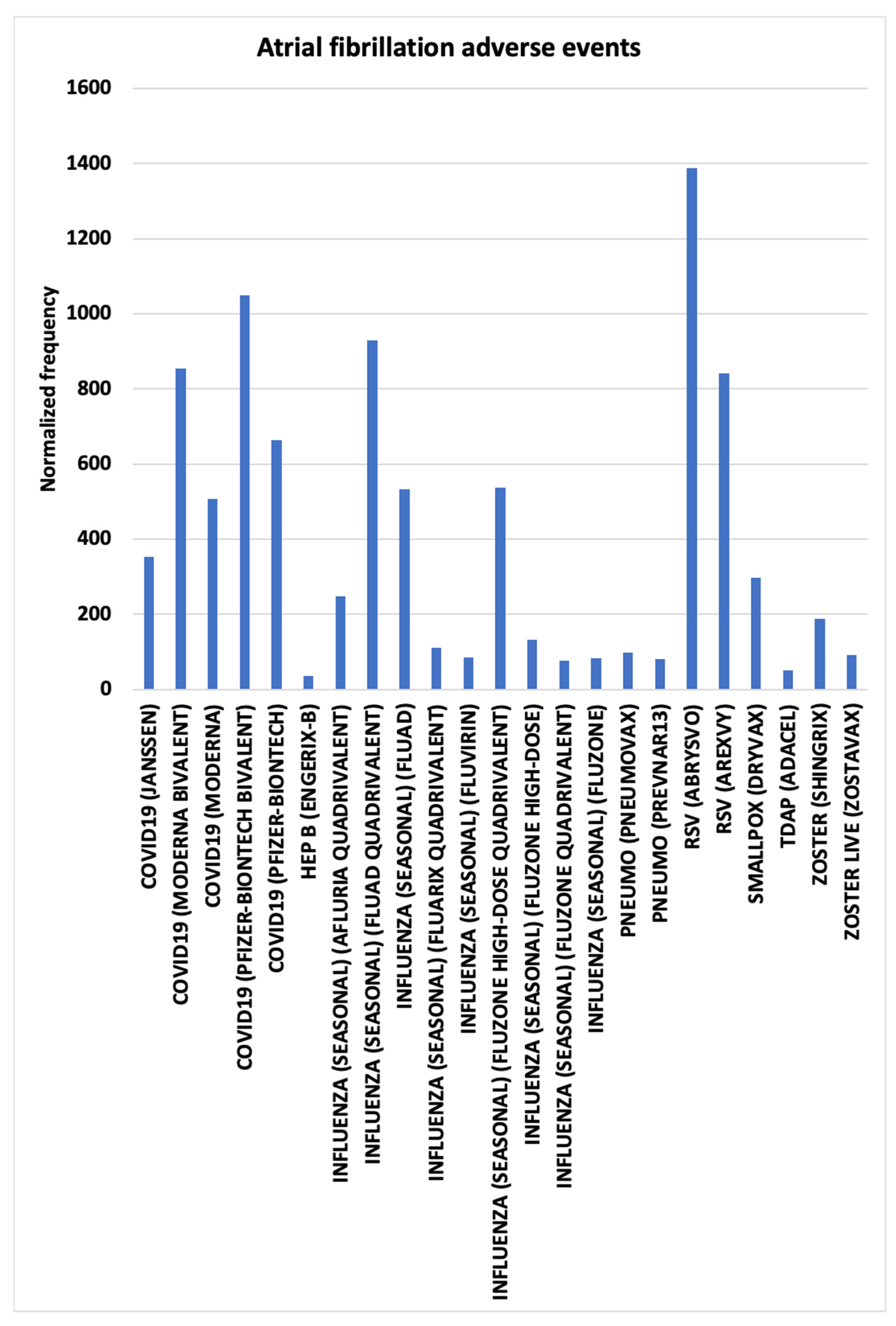

3.2. Atrial Fibrillation AEs

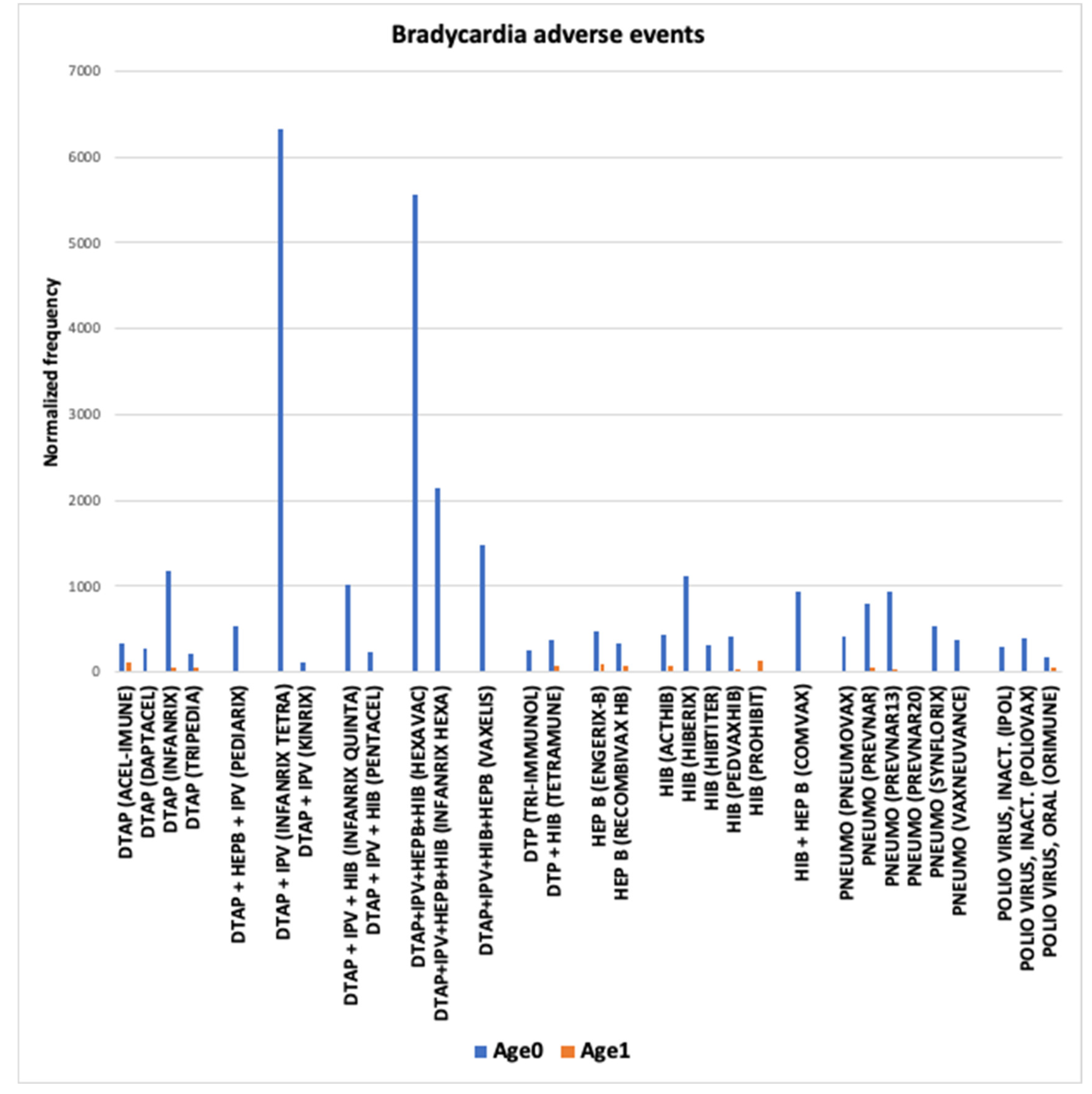

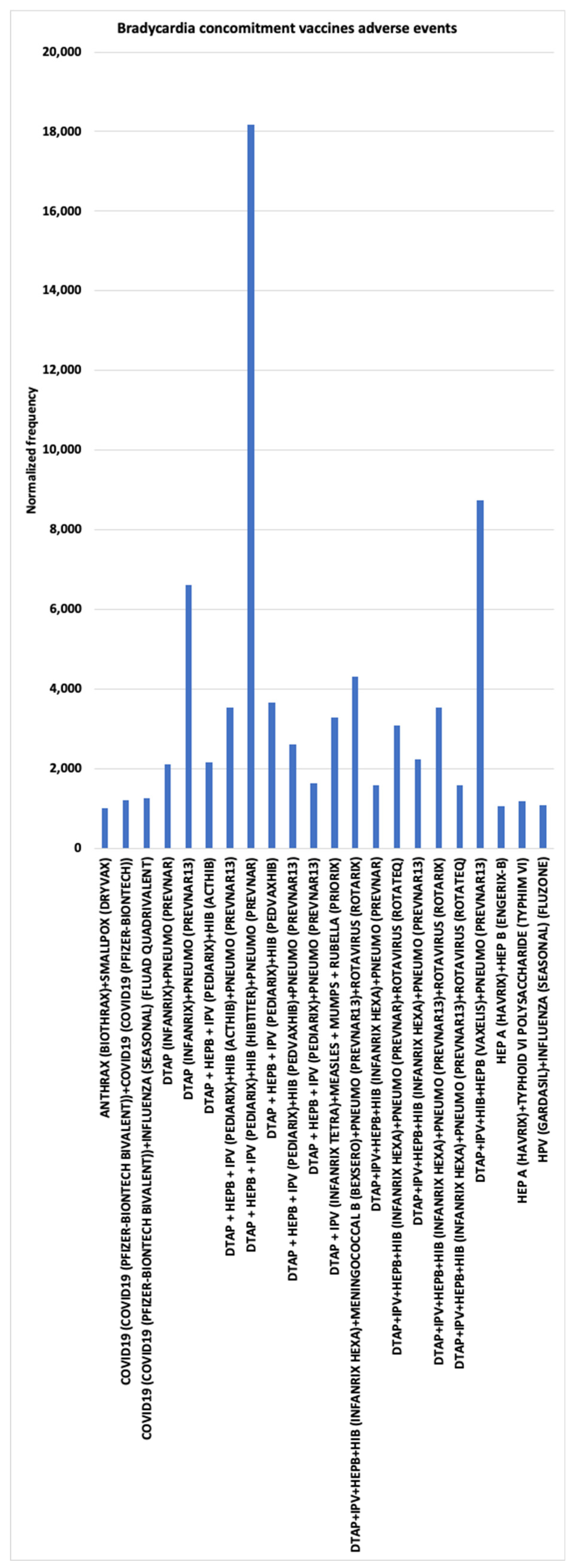

3.3. Bradycardia AEs

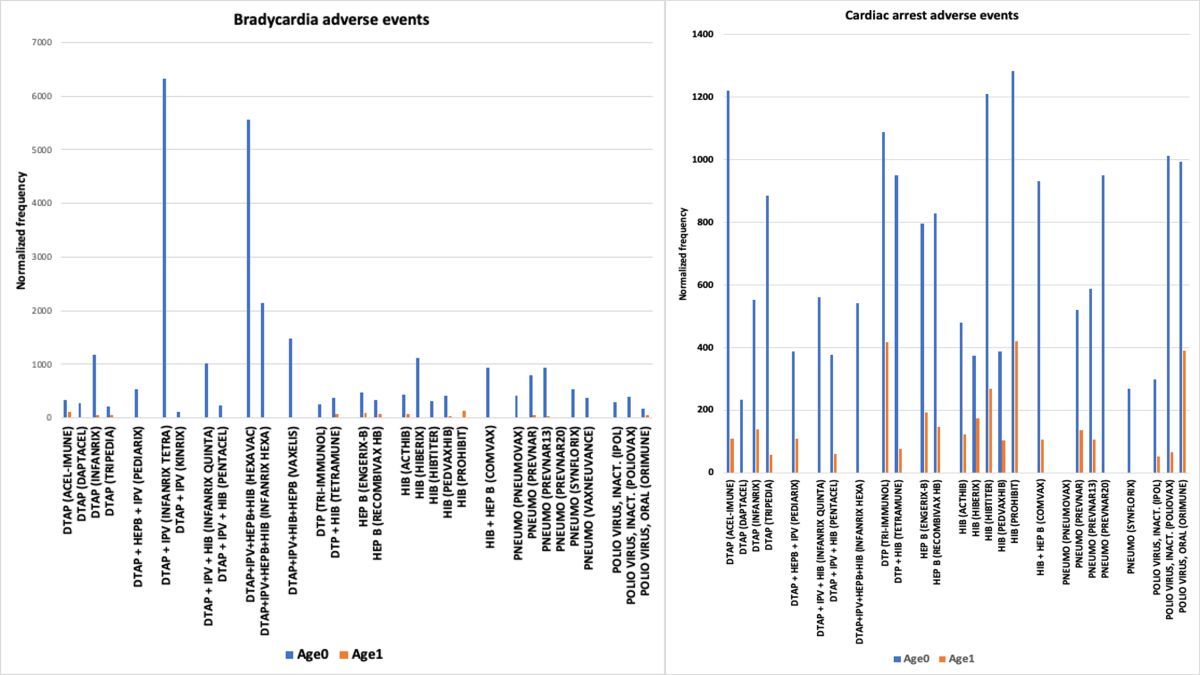

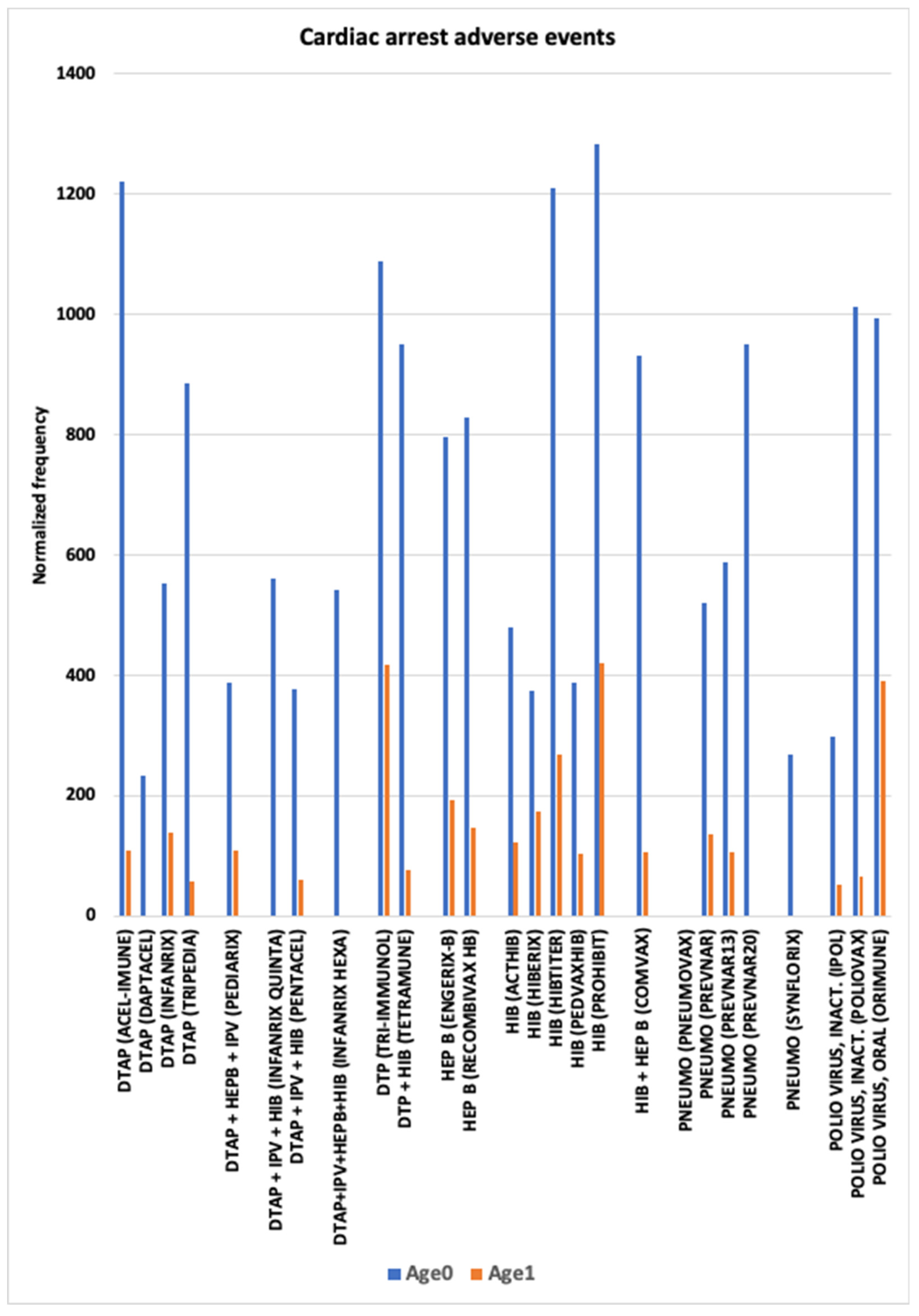

3.4. Cardiac Arrest AEs

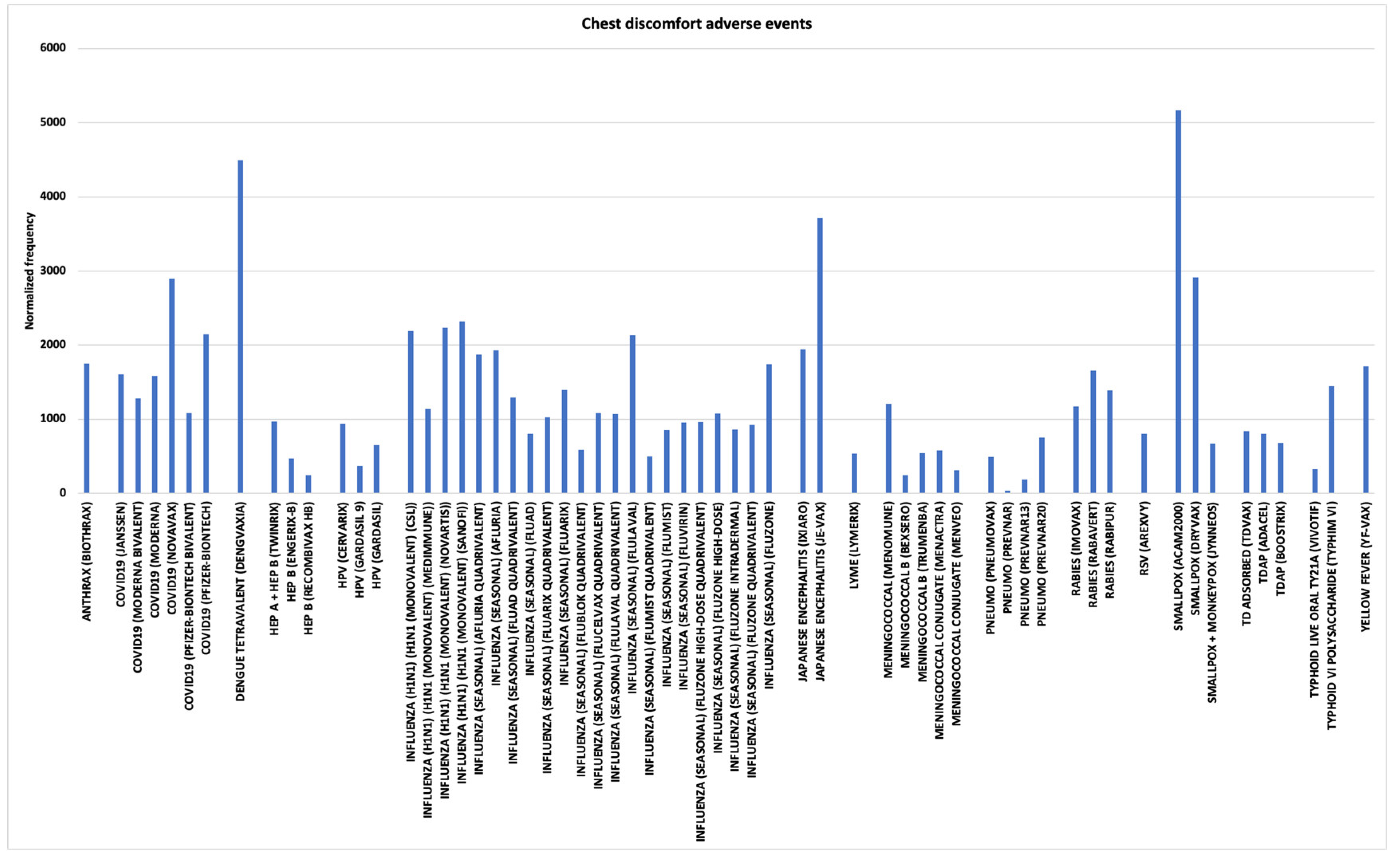

3.5. Chest Discomfort and Chest Pain AEs

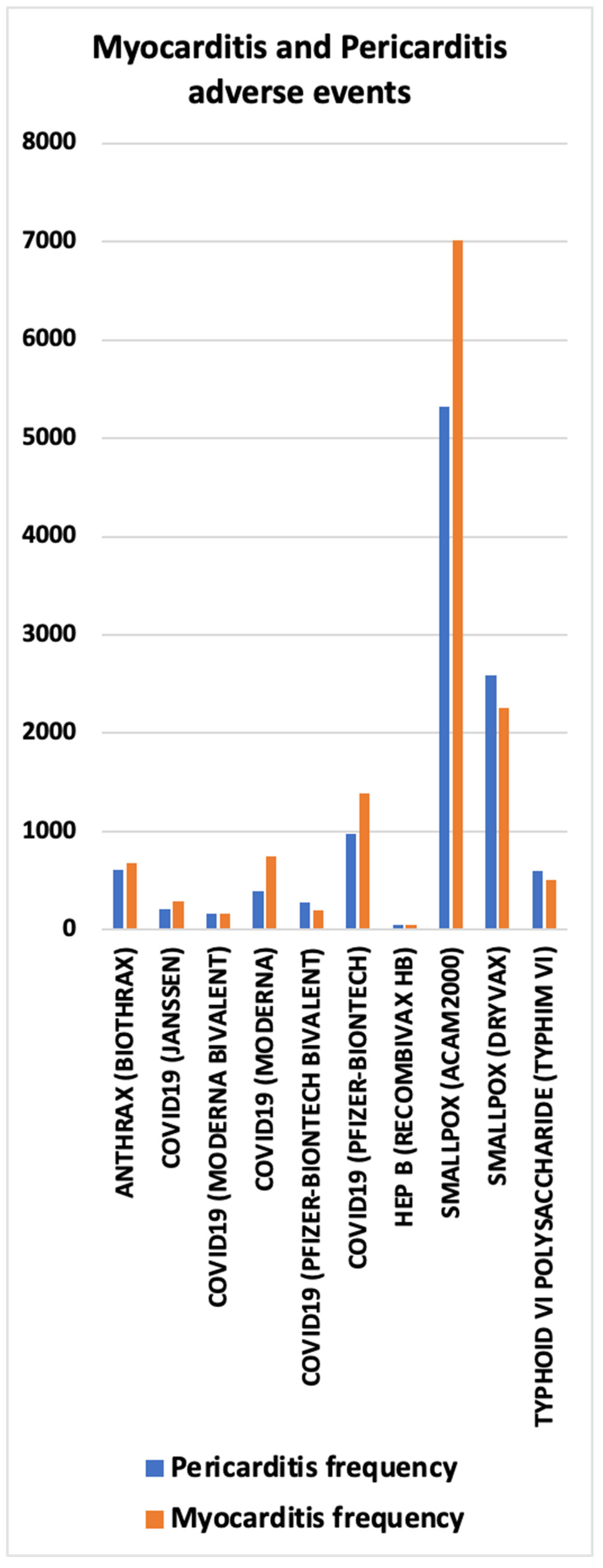

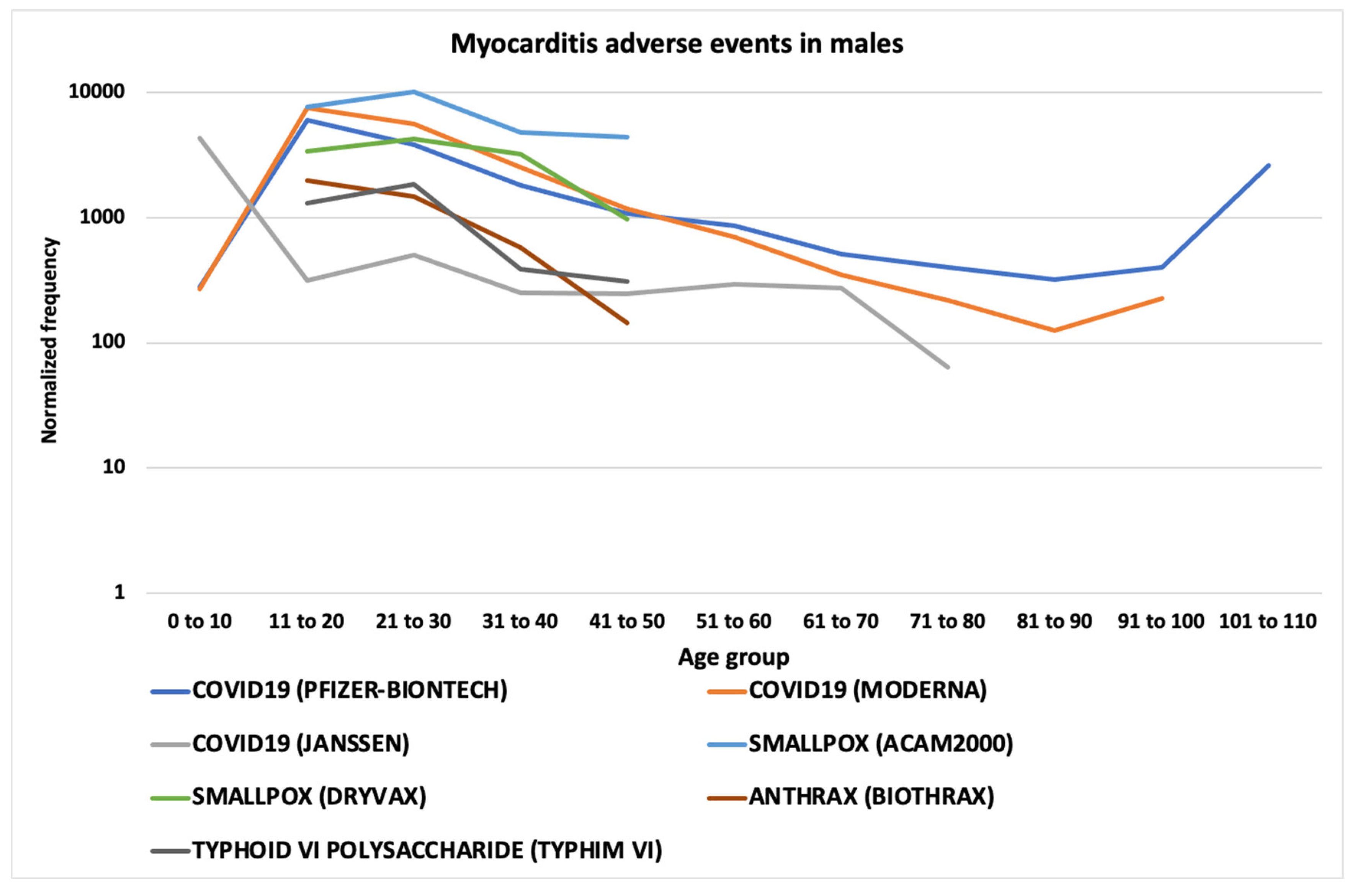

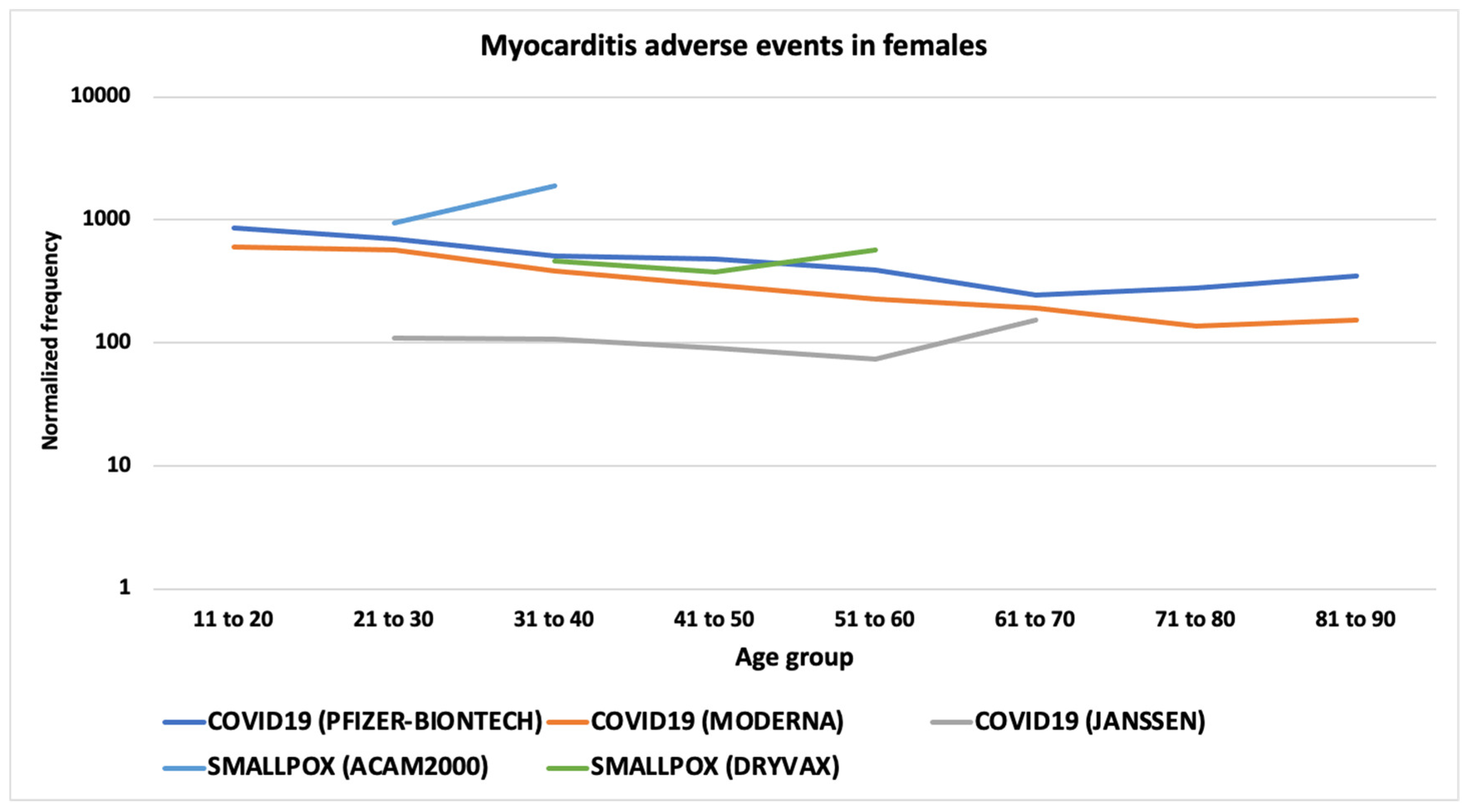

3.6. Myocarditis and Pericarditis AEs

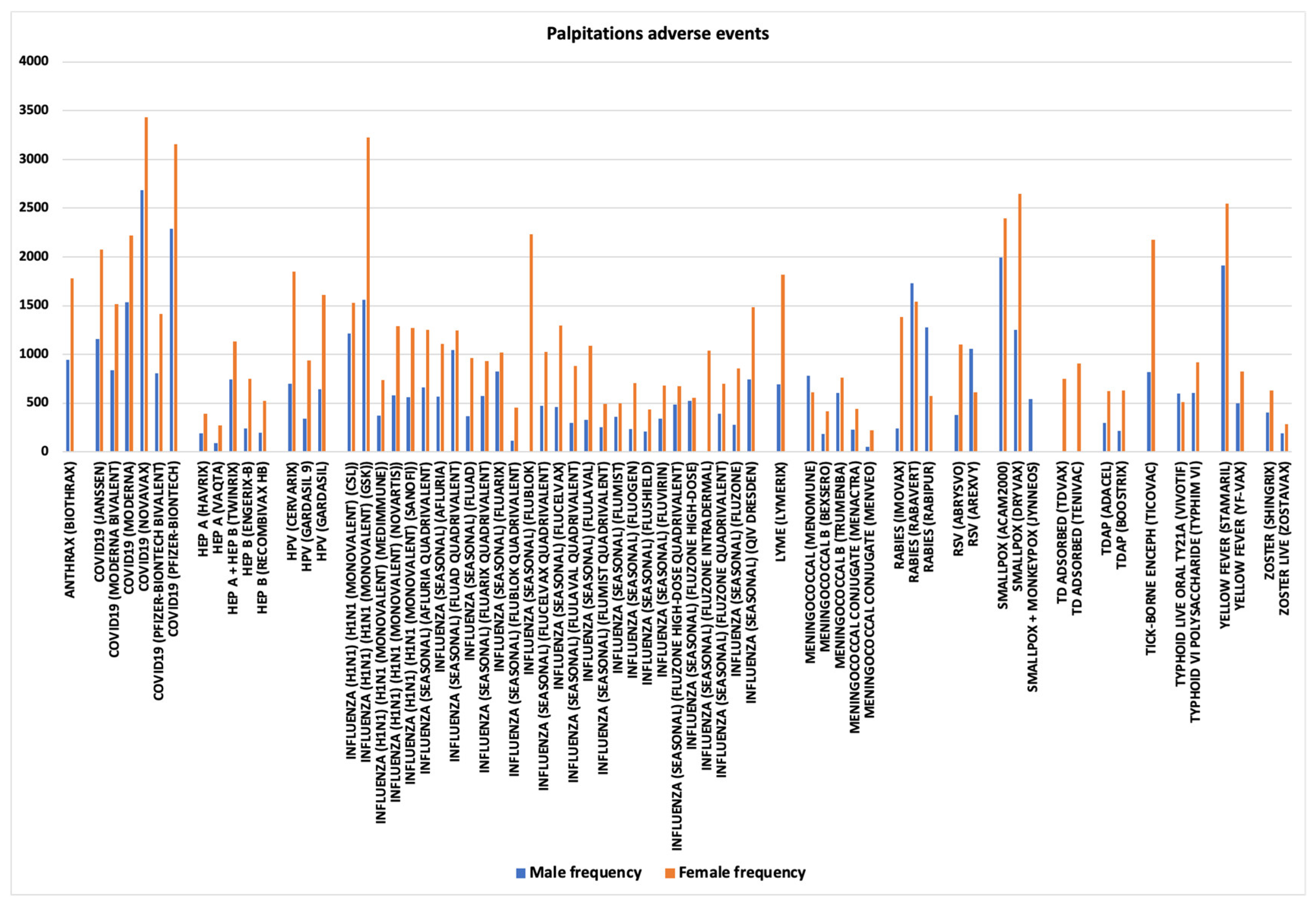

3.7. Palpitations

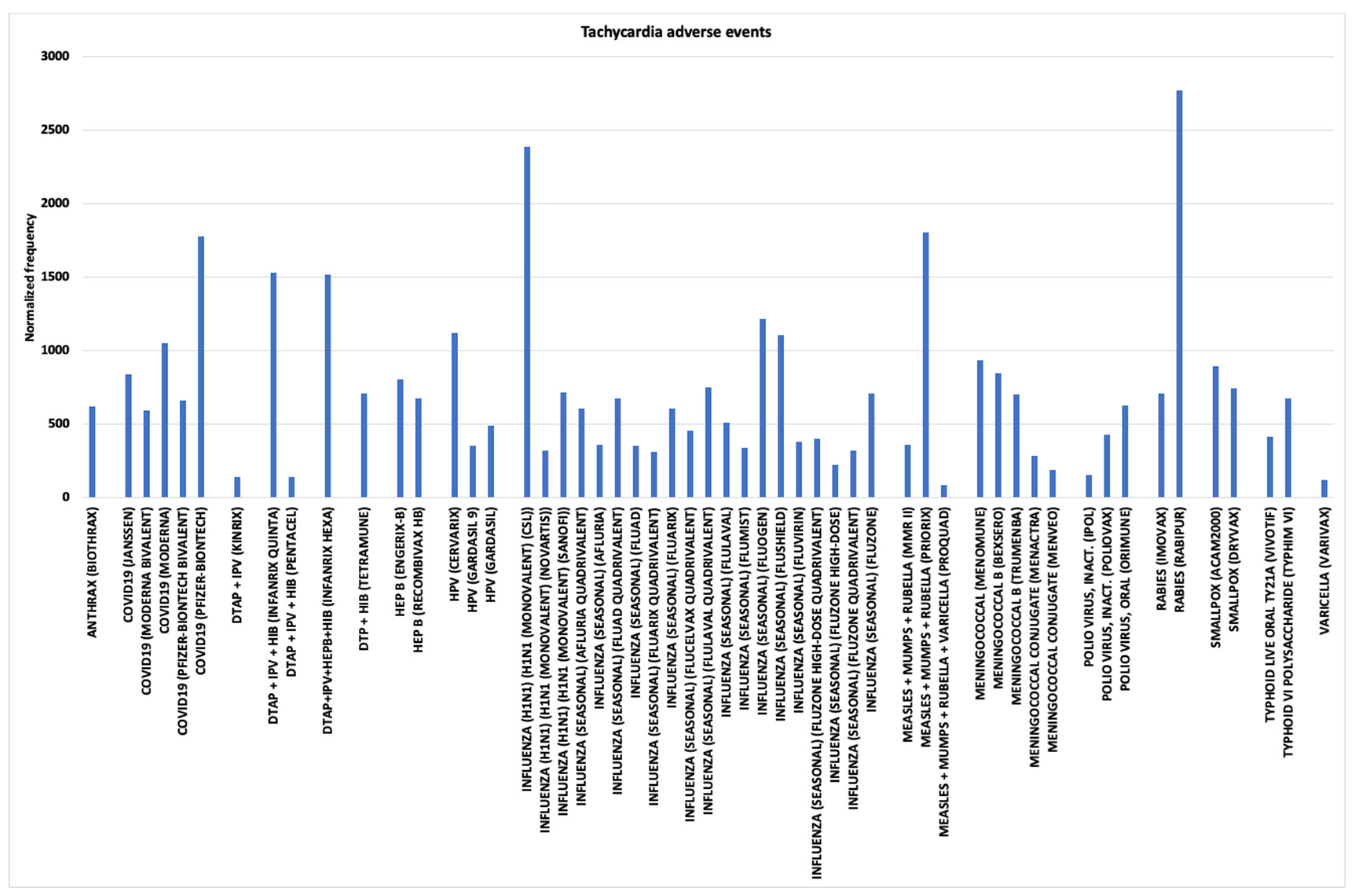

3.8. Tachycardia

4. Discussion

4.1. Immune System Signaling Molecules

4.2. Myocarditis and Pericarditis AEFIs

4.3. Cardiac AEFI Comparisons Across Vaccines

4.4. Bradycardia and Cardiac Arrest in Infants Vaccinees Aged 0

4.5. Study Limitations

4.6. Study Recommendations

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). 2024. Available online: https://vaers.hhs.gov/data.html (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Cassimatis DC, Atwood JE, Engler RM, Linz PE, Grabenstein JD, Vernalis MN. Smallpox vaccination and myopericarditis: a clinical review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004, 43, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittermayer, C. Lethal Complications of Typhoid-Cholera-Vaccination (Case Report and Review of the Literature). Beitr Pathol. 1976, 158, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee S, Jo H, Lee H, et al. Global estimates on the reports of vaccine-associated myocarditis and pericarditis from 1969 to 2023: Findings with critical reanalysis from the WHO pharmacovigilance database. J Med Virol. 2024, 96, e29693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho JSY, Sia C-H, Ngiam JN, et al. A review of COVID-19 vaccination and the reported cardiac manifestations. Singapore Med J 2023, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Sangpornsuk N, Rungpradubvong V, Tokavanich N, et al. Arrhythmias after SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Patients with a Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device: A Multicenter Study. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu S-N, Chen Y-S, Hsu C-C, et al. Changes of ECG parameters after BNT162b2 vaccine in the senior high school students. Eur J Pediatr. 2023, 182, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowe J, Whitaker HJ, Andrews NJ, Miller E. Risk of cardiac arrhythmia and cardiac arrest after primary and booster COVID-19 vaccination in England: A self-controlled case series analysis. Vaccine: X. 2023, 15, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen CY, Hsieh MT, Wei CT, Lin CW. Atrial Fibrillation After mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: Case Report with Literature Review. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2023, 16, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford GA, Hargroves D, Lowe D, et al. Targeted atrial fibrillation detection in COVID-19 vaccination clinics. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2021, 7, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero R, Donniacuo M, Mascolo A, et al. COVID-19 Vaccines and Atrial Fibrillation: Analysis of the Post-Marketing Pharmacovigilance European Database. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao Y-F, Tseng W-C, Wang J-K, et al. Management of cardiovascular symptoms after Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in teenagers in the emergency department. J Formos Med Assoc. 2023, 122, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park CH, Yang J, Lee HS, Kim TH, Eun LY. Characteristics of Teenagers Presenting with Chest Pain after COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kewan T, Flores M, Mushtaq K, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of adverse events after COVID-19 vaccination. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021, 2, e12565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansanguan S, Charunwatthana P, Piyaphanee W, Dechkhajorn W, Poolcharoen A, Mansanguan C. Cardiovascular Manifestation of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine in Adolescents. Trop Med Infect Dis 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba C-F, Chen B-H, Shao L-S, et al. CMR Manifestations, Influencing Factors and Molecular Mechanism of Myocarditis Induced by COVID-19 Mrna Vaccine. RCM 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushion S, Arboleda V, Hasanain Y, Demory Beckler M, Hardigan P, Kesselman MM. Comorbidities and Symptomatology of SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2)-Related Myocarditis and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine-Related Myocarditis: A Review. Cureus. 2022, 14, e24084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal M, Ray I, Mascarenhas D, Kunal S, Sachdeva RA, Ish P. Myocarditis post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a systematic review. QJM. 2023, 116, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botham SJ, Isaacs D, Henderson-Smart DJ. Incidence of apnoea and bradycardia in preterm infants following DTPw and Hib immunization: A prospective study. J Paediatr Child Health. 1997, 33, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen S, Cloete Y, Hassan K, Buss P. Adverse events following vaccination in premature infants. Acta Paediatr. 2001, 90, 916–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Robinson JL, Spady DW. Frequency of apnea, bradycardia, and desaturations following first diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis-inactivated polio-Haemophilus influenzae type B immunization in hospitalized preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 2006, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack MH, Schapira C, Thwaites RJ, Andrews N, Schapira D. Acellular pertussis and meningococcal C vaccines: cardio-respiratory events in preterm infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2003, 162, 436–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMeo SD, Raman SR, Hornik CP, Wilson CC, Clark R, Smith PB. Adverse Events After Routine Immunization of Extremely Low-Birth-Weight Infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knuf M, Charkaluk M-L, The Nguyen PN, et al. Penta- and hexavalent vaccination of extremely and very-to-moderate preterm infants born at less than 34 weeks and/or under 1500 g: A systematic literature review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023, 19, 2191575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedDRA. Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Archives, 2024. Available from: www.meddra.org [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 1].

- Ricke, DO. VAERS-Tools; 2024. Available from: https://github.com/doricke/VAERS-Tools [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 1].

- Chi Square Calculator for 2x2. Social Science Statistics, 2024. Available from: https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/chisquare/ [Last accessed on 2024 Jul 1].

- Dahan S, Segal Y, Dagan A, Shoenfeld Y, Eldar M. Cardiac arrest following HPV Vaccination. Clin Res Trials. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin LB, Dempsey TT, Weinstock LB. Post-HPV-Vaccination Mast Cell Activation Syndrome: Possible Vaccine-Triggered Escalation of Undiagnosed Pre-Existing Mast Cell Disease? Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonker LM, Swank Z, Bartsch YC, et al. Circulating Spike Protein Detected in Post–COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine Myocarditis. Circulation. 2023, 147, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt B, Kamat I, Hotez PJ. Myocarditis With COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines. Circulation. 2021, 144, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami A, Villeneuve PJ, Farrell PJ, et al. Myocarditis and Pericarditis Post-mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination: Insights from a Pharmacovigilance Perspective. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levick SP, Meléndez GC, Plante E, McLarty JL, Brower GL, Janicki JS. Cardiac mast cells: the centrepiece in adverse myocardial remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2011, 89, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. JYNNEOS FDA package insert, 2024. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/131078/download [Last accessed on 2024 Aug 28].

- Virzì GM, Clementi A, Brocca A, Ronco C. Endotoxin Effects on Cardiac and Renal Functions and Cardiorenal Syndromes. Blood Purif. 2017, 44, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suffredini Anthony F, Fromm Robert E, Parker Margaret M, et al. The Cardiovascular Response of Normal Humans to the Administration of Endotoxin. N Engl J Med. 1989, 321, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielska A, Matyjek M, Kwiatkowska K. TLR4 and CD14 trafficking and its influence on LPS-induced pro-inflammatory signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021, 78, 1233–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale HH, Laidlaw PP. The physiological action of β-iminazolylethylamine. J Physiol. 1910, 41, 318–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff AA, Levi R. Histamine and cardiac arrhythmias. Circ Res. 1986, 58, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maintz L, Novak N. Histamine and histamine intolerance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007, 85, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fremont-Smith M, Gherlone N, Smith N, Tisdall P, Ricke DO. Models for COVID-19 Early Cardiac Pathology Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Int J Infect Dis 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikenes K, Farstad M, Nordrehaug JE. Serotonin Is Associated with Coronary Artery Disease and Cardiac Events. Circulation. 1999, 100, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golino P, Piscione F, Willerson JT, et al. Divergent Effects of Serotonin on Coronary-Artery Dimensions and Blood Flow in Patients with Coronary Atherosclerosis and Control Patients. N Engl J Med. 1991, 324, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio E, Carrabba M, Milligan R, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein disrupts human cardiac pericytes function through CD147 receptor-mediated signalling: a potential non-infective mechanism of COVID-19 microvascular disease. Clin Sci. 2021, 135, 2667–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilioni I, Theoharides TC. Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Stimulates Secretion of Chymase, Tryptase, and IL-1β from Human Mast Cells, Augmented by IL-33. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Robles JP, Zamora M, Adan-Castro E, Siqueiros-Marquez L, Martinez de la Escalera G, Clapp C. The spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 induces endothelial inflammation through integrin α5β1 and NF-κB signaling. J Biol Chem. 2022/03/01/ 2022, 298, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricke, DO. Epilepsy adverse events post vaccination. Explor Neurosci. 2024, 3, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley MF, Reifler LM, Glanz JM, et al. Association Between Aluminum Exposure From Vaccines Before Age 24 Months and Persistent Asthma at Age 24 to 59 Months. Acad Pediatr. 2023, 23, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomljenovic L, Shaw CA. Do aluminum vaccine adjuvants contribute to the rising prevalence of autism? J Inorg Biochem. 2011, 105, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons-Weiler J, Ricketson R. Reconsideration of the immunotherapeutic pediatric safe dose levels of aluminum. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2018, 48, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarland G, La Joie E, Thomas P, Lyons-Weiler J. Acute exposure and chronic retention of aluminum in three vaccine schedules and effects of genetic and environmental variation. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2020, 58, 126444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccine Excipient Summary, 2024. Available from: https://canvax.ca/sites/default/files/2020-03/USCDC_VaccineExcipientSummary_2020.pdf [Last accessed on 2025 Jan 6].

- Shoenfeld Y, Agmon-Levin N. ‘ASIA’ – Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants. J Autoimmun. 2011, 36, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricke, DO. Two Different Antibody-Dependent Enhancement (ADE) Risks for SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).