Introduction

Kawasaki’s Disease (KD) is one of the leading causes of heart disease in children in the United States [

1]. KD is a rare vasculitis disease of unknown etiology. Recently, I proposed the etiology model for KD caused by immune complexes binding Fc receptors to activate mast cells and likely platelets releasing elevated histamine and possibly serotonin levels [

2]. Of interest, higher frequencies of epilepsy adverse events (AEs) were detected for infants age 0 for specific vaccines [

3]. Infants age 0 were also observed to have the highest number of Kawasaki’s Disease (KD) AEs reported in the VAERS database [

2]. Do the etiologies for these independent observations overlap? The two standard treatments for KD patients are intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and high dose aspirin. A subset of KD patients do not respond to IVIG (IVIG non-responders). In the proposed etiology model, could an alternative pathway activation of mast cells and likely platelets via non-Fc receptor pathway(s) be associated with no response to IVIG treatments?

Associations between KD and multiple viral [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25], and a few bacterial pathogens [

13,

26,

27]. have been reported. KD has also been reported as a rare adverse event associated with vaccinations and vaccine combinations:

Hypothesis 1. Kawasaki’s Disease is caused by release of elevated histamine levels and possibly serotonin released from activated mast cells and likely platelets [

2]. One mechanism for activation is immune complexes binding to the Fc receptors on mast cells and platelets.

Hypothesis 2. Immunization can trigger Kawasaki’s Disease by either (1) direct activation of mast cells from immune responses or by (2) immune complexes of antibodies binding to vaccine antigens.

Hypothesis 3. Kawasaki’s Disease patients that do not respond to IVIG treatment may be due to (1) ongoing KD-causing pathogen infection (e.g., ongoing high KD pathogen immune complexes concentrations) or (2) KD caused by direct activation of mast cells and possibly platelets from immune responses.

Herein, the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) was retrospectively examined for elevated normalized frequencies of Kawasaki’s Disease AE for children. Safety signals were identified for children associated with multiple specific vaccines, live virus vaccines, and specific concomitant vaccine combinations.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of the VAERS database [

43] from January 1, 1990 until October 25, 2024. VAERS was searched for the Kawasaki’s Disease adverse events. The Ruby program vaers_slice4.rb [

44] was used for retrospective analysis of the VAERS data files VAERSDATA, VAERSSYMPTOMS, and VAERSVAX for the years 1990 to 2024 and NonDomestic.

For vaccine (V

name), and each adverse event (X=Kawasaki’s Disease) in VAERS, normalized AE frequencies per P=100,000 VAERS reports per category AEs can be calculated with

equation I.

Results

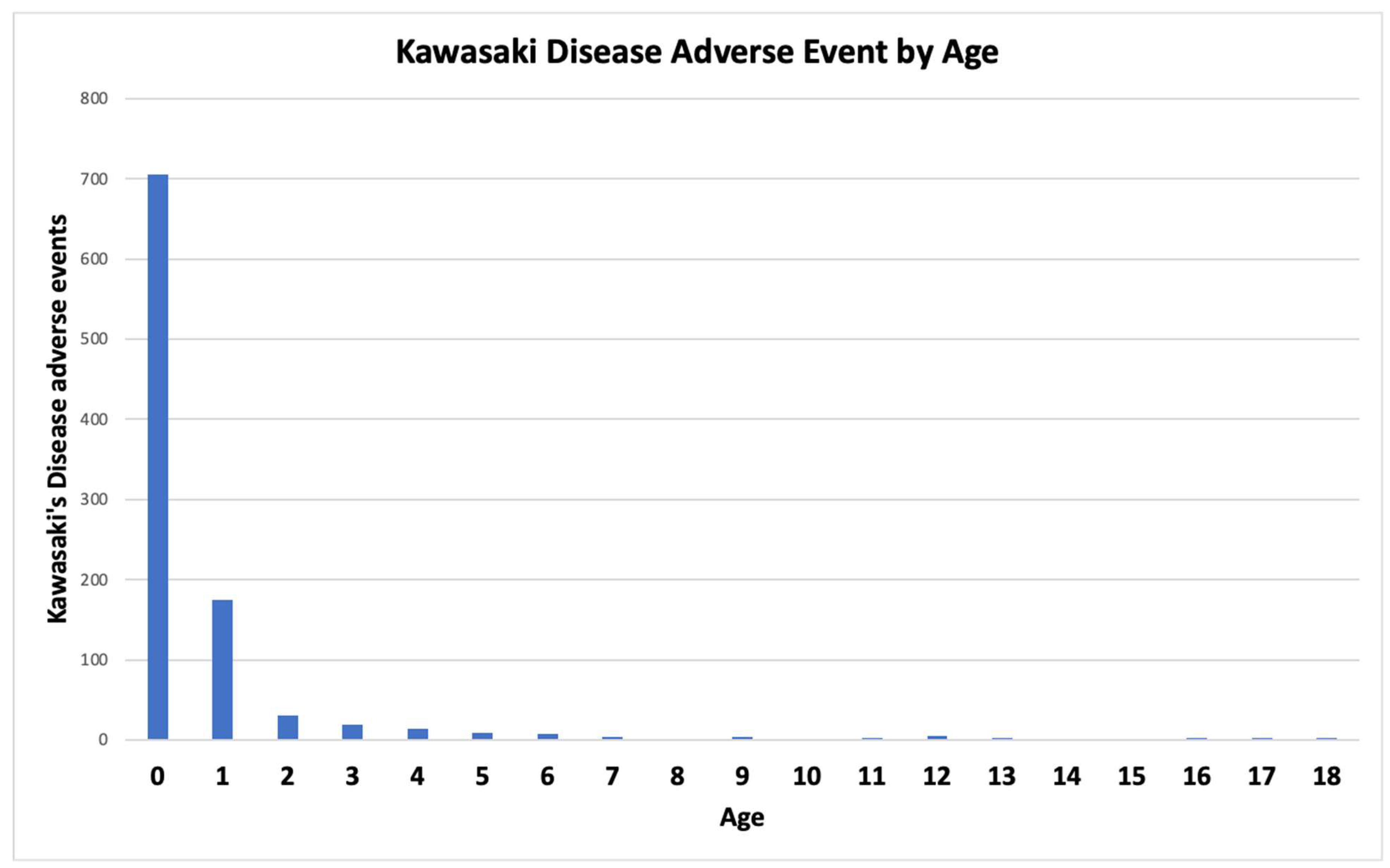

Infants age 0 represent the age group with the highest probability of developing KD followed by infants age 1 (

Figure 1). For over half of the KD adverse events in VAERS, the onset is within the first week with the highest reports within the first 48 hours (

Figure 2). The observed early onset timing is consistent with

Hypothesis 2 direct activation of mast cells and platelets while later onsets are consistent with

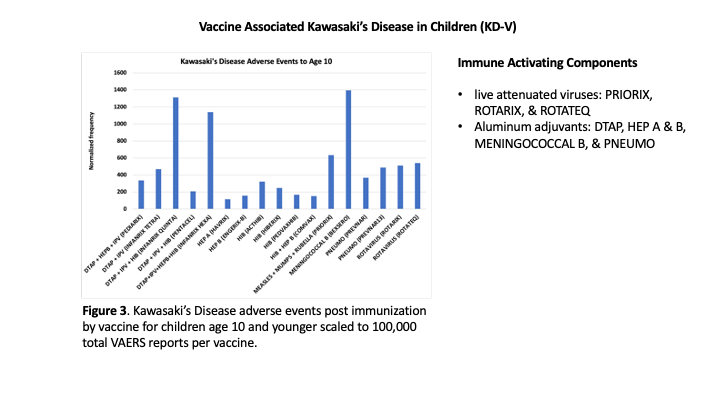

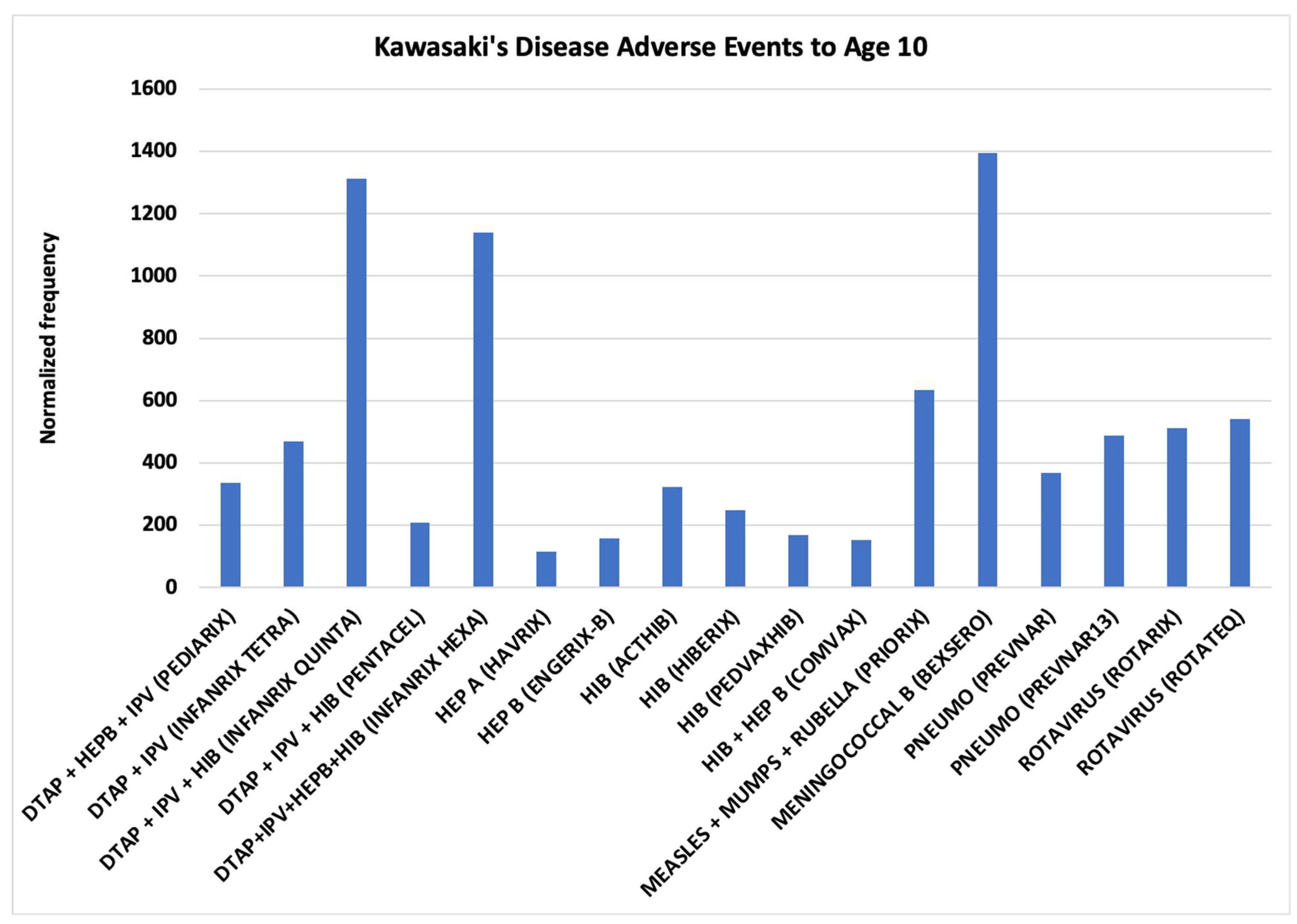

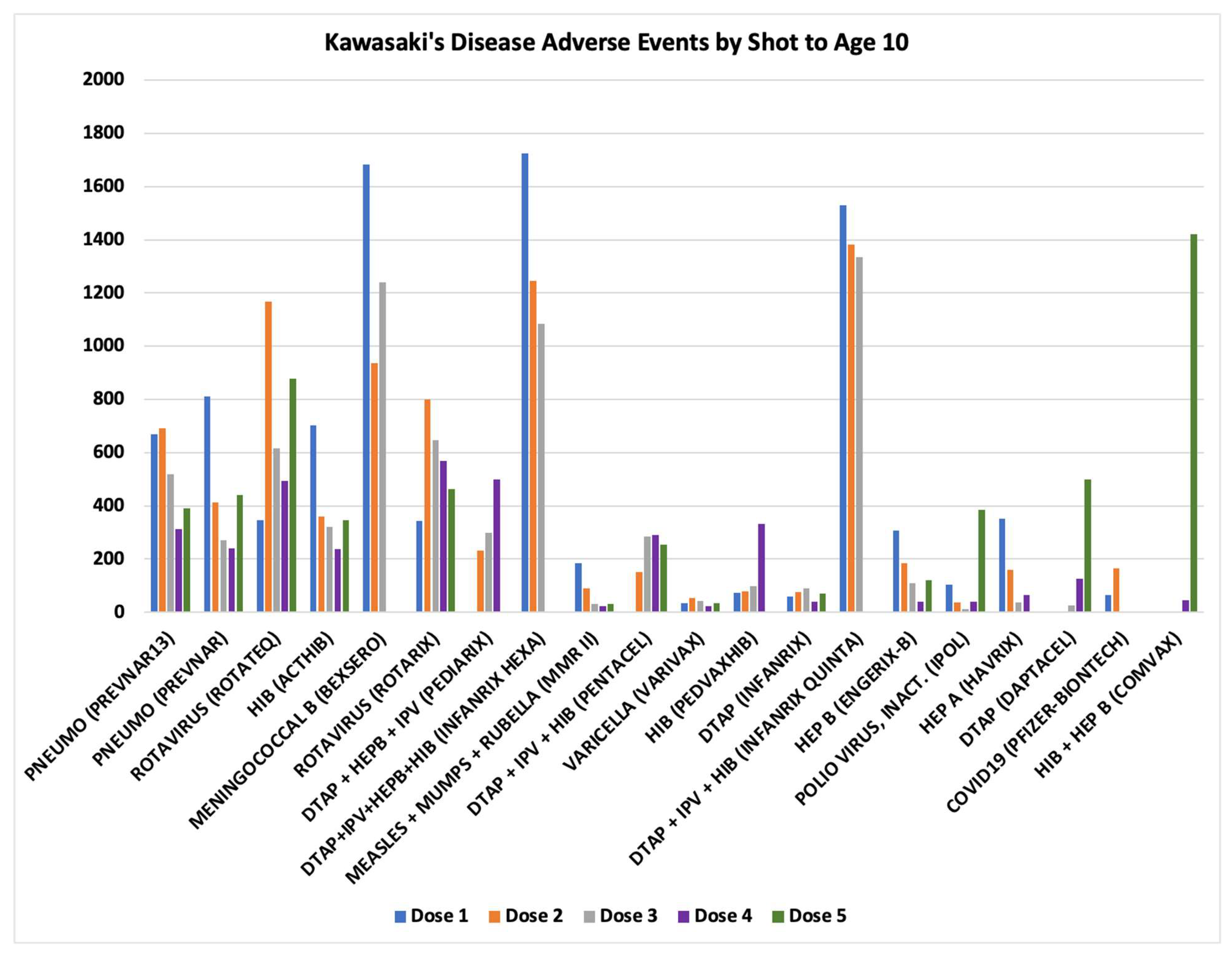

Hypothesis 1 activation of mast cells and platelets via Fc receptor activation. KD is occurring at high normalized frequencies for specific vaccines with the normalized frequency higher than 400 per 100K VAERS reports for eight vaccines for children age 10 or younger (

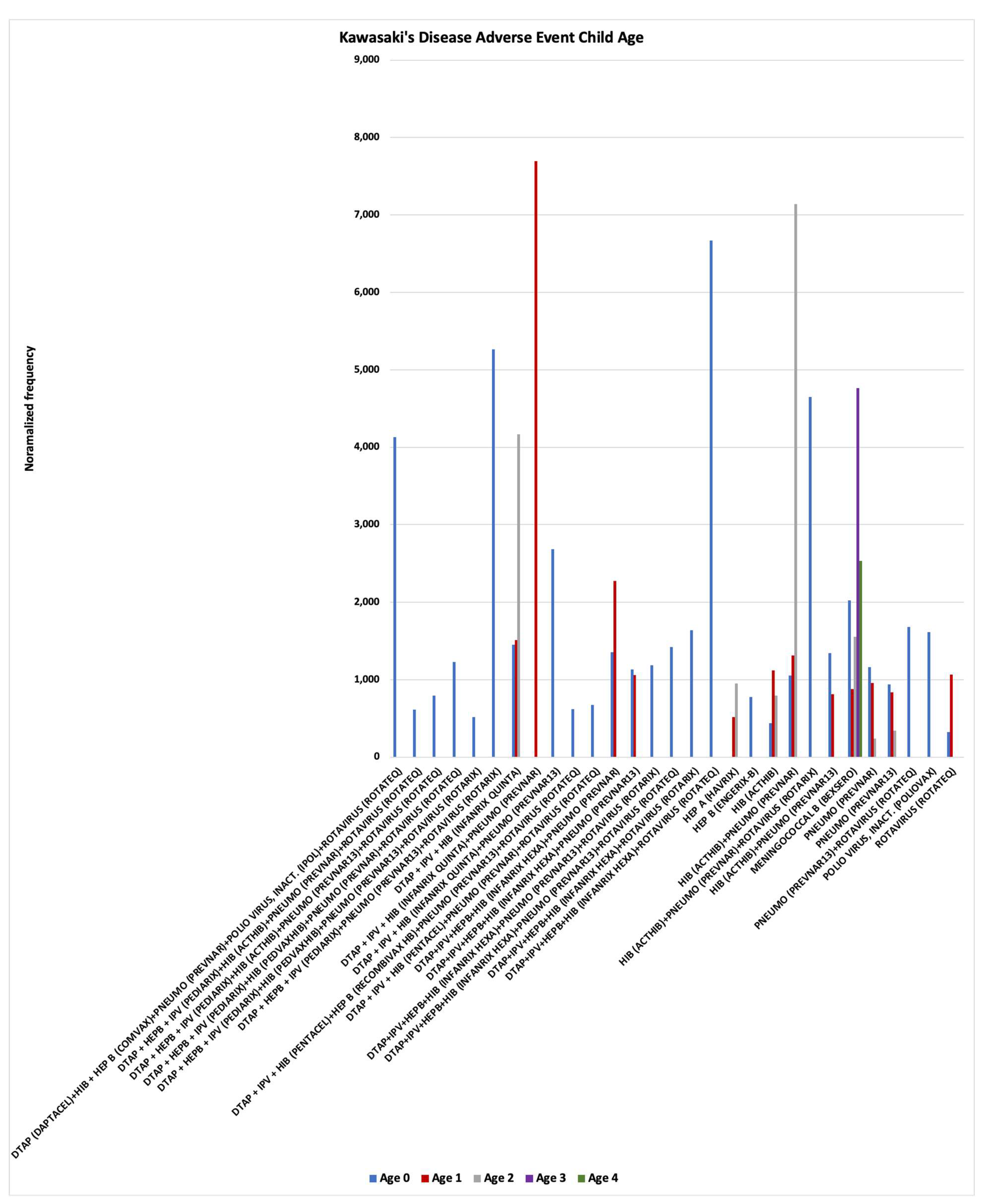

Figure 3). Vaccines are often concomitantly administered together to children with normalized frequencies exhibiting either additive risks or much higher synergy risks (

Figure 4). Higher synergy KD normalized frequencies are consistent with

Hypothesis 2 direct activation of mast cells and platelets. To fully vaccinate children for a pathogen, some vaccines have multiple doses that are administered consecutively according to recommended dose schedules [

45]. KD normalized frequencies for vaccines with multiple doses are shown in

Figure 5. Vaccines with similar normalized frequencies for multiple doses are consistent with

Hypothesis 2 direct activation of mast cells (e.g., Pneumo (PREVNAR13), Rotavirus (ROTATEQ), etc.). Vaccines with low normalized frequencies for initial doses with much higher normalized frequencies for later doses are consistent with

Hypothesis 2 activation of mast cells by immune complexes binding to Fc receptors (e.g., HIB (PEDVAXHIB), DTaP (DAPTACEL), HIB+HEP B (COMVAX)) (

Figure 5).

Nine vaccines had more than 200 VAERS reports but no KD reports for infants age 0: COVID19 (MODERNA BIVALENT), COVID19 (MODERNA), COVID19 (PFIZER-BIONTECH), HEP A (VAQTA), HIB (PEDVAXHIB), INFLUENZA (SEASONAL) (FLUZONE QUADRIVALENT), INFLUENZA (SEASONAL) (FLUZONE), PNEUMO (PNEUMOVAX), and VARICELLA (VARIVAX). These vaccines had no or few KD adverse events for infants age 1 (1 – MODERNA, 1 – VAQTA, and 3 – VARIVAX). Comparing the vaccine excipients and potential manufacturing contaminants (e.g., endotoxins) between these vaccines and those with higher normalized frequencies (

Figure 2) may enable identification of causative components for triggering KD in vaccinees in addition to the high dosage level factor for younger children identified herein. Candidate components include

live viruses and

aluminum compounds (

Table 1). Note that possible manufacturing contaminants (e.g., endotoxins) cannot be eliminated.

Discussion

While KD is observed in individuals of all ages, infants less than one year of age predominate in KD following immunization (

Figure 1); this KD age association pattern is consistent with infant vaccine dosages levels being too high. For identified vaccines, adjusting vaccine dosage to child body size will likely reduce KD in young children. Likewise, reducing the infectious units in live attenuated virus vaccines will likely reduce associated KD risks. For KD following immunization, onset is fairly rapid (majority cases reported in 48 to 72 hours of immunization –

Figure 2). This rapid onset of KD AEFI favors

Hypothesis 2 direct activation of mast cells from immune responses and not activation by Fc receptor binding of immune complexes. KD AEFIs are occurring following immunization with specific vaccines (

Figure 3) and not others (e.g., influenza for matched age infants) and specific concomitant vaccine combinations (

Figure 4). Possible causative factors include vaccine dosage level per body weight, combined dosage levels of components for specific concomitant vaccine combinations (i.e., not one but multiple adjuvants with increased levels for common components like aluminum, etc., see

Table 1), and also including possible manufacturing contamination (e.g., endotoxins) triggering KD AEFIs. Examining the vaccine components for the vaccines listed in

Figure 3, the following candidate causative components are identified: (1)

live attenuated viruses (PRIORIX, ROTARIX, and ROTATEQ) and (2)

aluminum compounds (11 vaccines) (

Table 1). Concomitant administration of these candidate agents likely causes increased risk levels in infants that are either

additive or

synergistic (levels much higher than the sum of the individual vaccine risk levels); both additive and synergy KD AEFI risks are observed (

Figure 4). Note that Meningococcal B (BEXSERO) has high KD normalized frequencies for children age 0 to 4 (

Figure 4). For multi-dose vaccines, similar risk levels for each of multiple doses is consistent with direct innate immune activation (

Figure 5). KD risk levels that only appear after multiple doses are consistent with immune complex activation of Fc receptors on mast cells and likely platelets (

Figure 5) (

Hypothesis 1).

Hypothesis 4: Over activation of immune responses is causing KD AEFIs (KD-V) in children. With lack of dose adjustment based on child’s body size (age), KD AEFIs can result (

Figure 1) for specific vaccines, live attenuated viral vaccines with infectious units not adjusted for child body size, and multiple specific concomitant vaccine combinations (including increased concentrations of adjuvant components – e.g., aluminum).

The onset data (

Figure 2) and multiple dose results (

Figure 5) support models of activation of mast cells and likely platelets by (1) direct innate immune responses supporting

Hypothesis 2 and (2) immune complex activation of Fc receptors supporting

Hypothesis 1. Treatments of KD patients by IVIG in the context of direct innate immune response activations is predicted to appear as IVIG non-responders. And, relevant to

Hypothesis 1, IVIG treatment should act as competitive antibodies for Fc receptor binding that reduces activation for the alternative activation pathway; but, for ongoing infections (including live vaccines), IVIG treatment may appear as non-responsive because of ongoing creation of immune complexes. If the proposed KD etiology models are correct, then additional adjunctive treatments including mast cell stabilizers, anti-histamines, and possibly serotonin antagonists may reduce KD symptoms; institutional review board (IRB) approved targeted clinical studies (e.g., case series) are suggested (perhaps focusing on IVIG non-responders).

Study Limitations

The VAERS database collects only a small subset of AEs experienced by vaccinees. Any reporting biases or exclusion of AEs would perturb the normalized frequencies presented herein. The AEFI normalized frequencies estimated for vaccinees with any AEs and do not include asymptomatic individuals; population AEFI normalized frequencies can be calculated by increasing the population size (P) to include the population fraction of asymptomatic vaccinees.

Study Recommendations

The age associated risk levels observed for KD AEFIs is consistent with vaccine dose levels being too high in younger children. Causative factors, including aluminum adjuvants and possible manufacturing contaminants (e.g., endotoxins) are also candidates for further research. In agreement with Tomljenovic and Shaw’s conclusion [

46], a more rigorous evaluation of aluminum adjuvant safety is warranted. Understanding the etiology of how KD is developing in children will provide the foundation for avoidance of KD AEFIs in current and future vaccines. Components of current vaccines can be compared between vaccines with higher AE frequencies and with those with no AEs for the identifying possible causative components. Characterization of vaccine lots to identify or exclude potential manufacturing contaminations with techniques like mass spectrometry is suggested. The data herein, supports adjusting vaccine dosage to child body weight and the development of alternatives to live virus infant vaccines. Given the current CDC recommendations for concomitant administration of multiple vaccines [

45], the maximum allowable aluminum amount per vaccine needs to be lowered to account for the youngest infants. Consideration of risks versus benefits for vaccinating children younger than 5 years of age with MENINGOCOCCAL B (BEXSERO) is advised (

Figure 4). To minimize risk of KD, live virus vaccines should not be concomitantly administered with vaccines containing aluminum adjuvants (

Table 1). Likewise, concomitant administration of multiple aluminum adjuvanted vaccines

(Table 1) should be counterindicated (without adjustment for total aluminum dosing by child age/weight). Avoidance of concomitant administration of vaccines in infants aged 0 with higher KD normalized frequencies (

Figure 4) is strongly recommended:

DTAP (DAPTACEL) & HIB + HEP B (COMVAX) & PNEUMO (PREVNAR) & POLIO VIRUS, INACT. (IPOL) & ROTAVIRUS (ROTATEQ)

DTAP + HEPB + IPV (PEDIARIX) & PNEUMO (PREVNAR13) & ROTAVIRUS (ROTARIX)

DTAP + IPV + HIB (INFANRIX QUINTA) & PNEUMO (PREVNAR13)

DTAP+IPV+HEPB+HIB (INFANRIX HEXA) & ROTAVIRUS (ROTATEQ)

HIB (ACTHIB) & PNEUMO (PREVNAR) & ROTAVIRUS (ROTARIX)

Conclusions

Kawasaki’s Disease associated with vaccinations (KD-V) appear to share overlaps with the etiology with epilepsy AEFI. Infants aged 0 and 1 appear to have high risk levels for live virus vaccines, specific vaccines (dosage level too high for child body size), and specific concomitant vaccine combinations (additive dosage levels too high for child body size). Concomitant administration of these vaccines results in additive or synergy risk levels and is recommended against (counter indicated). Alternatives to live virus vaccines for infants is strongly recommended. Over activation of immune responses by vaccine dosage levels for specific vaccines, live vaccines (infectious units not adjusted for body size), and specific concomitant vaccine combinations are likely causing Kawasaki’s Disease AEFIs (KD-V).

Author Contributions

DOR: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. The author has read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Distribution Statement: A. Approved for public release. Distribution is unlimited. This material is based upon work supported by the Department of the Air Force under Air Force Contract [No. FA8702-15-D-0001]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Air Force. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data

Kawasaki’s Disease adverse events summary results from VAERS are available as Supplemental Data.

Acknowledgments

MedDRA® trademark is registered by ICH.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Taubert KA, Rowley AH, Shulman ST. Nationwide survey of Kawasaki disease and acute rheumatic fever. J Pediatr. 1991;119:279-82. [CrossRef]

- Ricke DO, Smith N. VAERS Vasculitis Adverse Events Retrospective Study: Etiology Model of Immune Complexes Activating Fc Receptors in Kawasaki Disease and Multisystem Inflammatory Syndromes. Life. 2024;14. [CrossRef]

- Ricke DO. Epilepsy adverse events post vaccination. Explor Neurosci. 2024;3:508-19. [CrossRef]

- Embil JA, McFarlane ES, Murphy DM, Krause VW, Stewart HB. Adenovirus type 2 isolated from a patient with fatal Kawasaki disease. Can Med Assoc J. 1985;132:1400-.

- Chang L-Y, Lu C-Y, Shao P-L, Lee P-I, Lin M-T, Fan T-Y, et al. Viral infections associated with Kawasaki disease. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113:148-54. [CrossRef]

- Catalano-Pons C, Giraud C, Rozenberg F, Meritet JF, Lebon P, Gendrel D. Detection of human bocavirus in children with Kawasaki disease. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:1220-2. [CrossRef]

- Shirato K, Imada Y, Kawase M, Nakagaki K, Matsuyama S, Taguchi F. Possible involvement of infection with human coronavirus 229E, but not NL63, in Kawasaki disease. J Med Virol. 2014;86:2146-53. [CrossRef]

- Esper F, Weibel C, Ferguson D, Landry ML, Kahn JS. Evidence of a Novel Human Coronavirus That Is Associated with Respiratory Tract Disease in Infants and Young Children. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:492-8. [CrossRef]

- Catalano-Pons C, Quartier P, Leruez-Ville M, Kaguelidou F, Gendrel D, Lenoir G, et al. Primary Cytomegalovirus Infection, Atypical Kawasaki Disease, and Coronary Aneurysms in 2 Infants. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:e53-e6. [CrossRef]

- Jagadeesh A, Krishnamurthy S, Mahadevan S. Kawasaki Disease in a 2-year-old Child with Dengue Fever. Indian J Pediatr. 2016;83:602-3. [CrossRef]

- Sopontammarak S, Promphan W, Roymanee S, Phetpisan S. Positive Serology for Dengue Viral Infection in Pediatric Patients With Kawasaki Disease in Southern Thailand. Circ J. 2008;72:1492-4. [CrossRef]

- Weng K-P, Cheng-Chung Wei J, Hung Y-M, Huang S-H, Chien K-J, Lin C-C, et al. Enterovirus Infection and Subsequent Risk of Kawasaki Disease: A Population-based Cohort Study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37. [CrossRef]

- Kikuta H, Nakanishi M, Ishikawa N, Konno M, Matsumoto S. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus sequences in patients with Kawasaki disease by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Intervirology. 1992;33:1-5. [CrossRef]

- Okano M, Luka J, Thiele GM, Sakiyama Y, Matsumoto S, Purtilo DT. Human herpesvirus 6 infection and Kawasaki disease. J Clin microbiol. 1989;27:2379-80. [CrossRef]

- Okano M. Kawasaki Disease and Human Lymphotropic Virus Infection. Curr Med Res Opin. 1999;15:129-34. [CrossRef]

- Joshi AV, Jones KDJ, Buckley A-M, Coren ME, Kampmann B. Kawasaki disease coincident with influenza A H1N1/09 infection. Pediatr Int. 2011;53:e1-e2.

- Whitby D, Hoad JG, Tizard EJ, Dillon MJ, Weber JN, Weiss RA, et al. Isolation of measles virus from child with Kawasaki disease. Lancet. 1991;338:1215.

- Holm JM, Hansen LK, Oxhøj H. Kawasaki disease associated with parvovirus B19 infection. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:633-4.

- Nigro G, Krzysztofiak A, Porcaro MA, Mango T, Zerbini M, Gentilomi G, et al. Active or recent parvovirus B19 infection in children with Kawasaki disease. Lancet. 1994;343:1260-1. [CrossRef]

- Keim D, Keller E, Hirsch M. Mucocutaneous Lymph-Node Syndrome and Parainfluenza 2 Virus Infection. Lancet. 1977;310:303. [CrossRef]

- Kim GB, Park S, Kwon BS, Han JW, Park YW, Hong YM. Evaluation of the Temporal Association between Kawasaki Disease and Viral Infections in South Korea. Korean Circ J. 2014;44:250-4. [CrossRef]

- Matsuno S, Utagawa E, Sugiura A. Association of Rotavirus Infection with Kawasaki Syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:177-. [CrossRef]

- Ogboli MI, Parslew R, Verbov J, Smyth R. Kawasaki disease associated with varicella: a rare association. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:1136-52. [CrossRef]

- Kossiva L, Papadopoulos M, Lagona E, Papadopoulos G, Athanassaki C. Myocardial infarction in a 35-day-old infant with incomplete Kawasaki disease and chicken pox. Cardiol Young. 2010;20:567-70. [CrossRef]

- Thissen JB, Isshiki M, Jaing C, Nagao Y, Lebron Aldea D, Allen JE, et al. A novel variant of torque teno virus 7 identified in patients with Kawasaki disease. PloS One. 2018;13:e0209683-e. [CrossRef]

- Hall M, Hoyt L, Ferrieri P, Schlievert PM, Jenson HB. Kawasaki Syndrome-Like Illness Associated with Infection Caused by Enterotoxin B-Secreting Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:586-9. [CrossRef]

- Shinomiya N, Takeda T, Kuratsuji T, Takagi K, Kosaka T, Tatsuzawa O, et al. Variant Streptococcus sanguis as an etiological agent of Kawasaki disease. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1987;250:571-2.

- Banday AZ, Patra PK, Jindal AK. Kawasaki disease – when Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) lymphadenitis blooms again and the vaccination site peels off! Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:e233-e4.

- Alsager K, Khatri Vadlamudi N, Jadavji T, Bettinger JA, Constantinescu C, Vaudry W, et al. Kawasaki disease following immunization reported to the Canadian Immunization Monitoring Program ACTive (IMPACT) from 2013 to 2018. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18:2088215. [CrossRef]

- Hall GC, Tulloh RMR, Tulloh LE. The incidence of Kawasaki disease after vaccination within the UK pre-school National Immunisation Programme: an observational THIN database study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25:1331-6. [CrossRef]

- Ece I, Akbayram S, Demiroren K, Uner A. Is Kawasaki Disease a Side Effect of Vaccination as Well? J Vaccines Vaccin. 2014;5.

- Chang A, Islam S. Kawasaki disease and vasculitis associated with immunization. Pediatr Int. 2018;60:613-7. [CrossRef]

- Miron D, Fink D, Hashkes PJ. Kawasaki disease in an infant following immunisation with hepatitis B vaccine. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22:461-3. [CrossRef]

- Jeong SW, Kim DH, Han MY, Cha SH, Yoon KL. An infant presenting with Kawasaki disease following immunization for influenza: A case report. Biomed Rep. 2018;8:301-3. [CrossRef]

- Kraszewska-Głomba B, Kuchar E, Szenborn L. Three episodes of Kawasaki disease including one after the Pneumo 23 vaccine in a child with a family history of Kawasaki disease. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115:885-6. [CrossRef]

- Shimada S, Watanabe T, Sato S. A Patient with Kawasaki Disease Following Influenza Vaccinations. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34. [CrossRef]

- Yin S, Liubao P, Chongqing T, Xiaomin W. The first case of Kawasaki disease in a 20-month old baby following immunization with rotavirus vaccine and hepatitis A vaccine in China: A case report. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:2740-3. [CrossRef]

- Matsubara D, Minami T, Seki M, Tamura D, Yamagata T. Occurrence of Kawasaki disease after simultaneous immunization. Pediatr Int. 2019;61:1171-3. [CrossRef]

- Huang W-T, Juan Y-C, Liu C-H, Yang Y-Y, Chan KA. Intussusception and Kawasaki disease after rotavirus vaccination in Taiwanese infants. Vaccine. 2020;38:6299-303. [CrossRef]

- Showers CR, Maurer JM, Khakshour D, Shukla M. Case of adult-onset Kawasaki disease and multisystem inflammatory syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15:e249094.

- Peralta-Amaro AL, Tejada-Ruiz MI, Rivera-Alvarado KL, Cobos-Quevedo OD, Romero-Hernández P, Macías-Arroyo W, et al. Atypical Kawasaki Disease after COVID-19 Vaccination: A New Form of Adverse Event Following Immunization. Vaccines. 2022;10. [CrossRef]

- Schmöeller D, Keiserman MW, Staub HL, Velho FP, de Fátima Grohe M. Yellow Fever Vaccination and Kawasaki Disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28. [CrossRef]

- VAERS. VAERS Data Sets 2024 [cited 2024 June 28, 2024]. Available from: https://vaers.hhs.gov/data/datasets.html.

- Ricke DO. VAERS-Tools 2022 [cited 2024 July 1, 2024]. Available from: https://github.com/doricke/VAERS-Tools.

- CDC. Child and Adolescent Immunization Schedule by Age 2024 [cited 2024 June 28, 2024]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/child-adolescent.html.

- Tomljenovic L, Shaw CA. Do aluminum vaccine adjuvants contribute to the rising prevalence of autism? J Inorg Biochem. 2011;105:1489-99.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).