Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Vector-borne parasitic diseases represent a critical public health challenge in Africa, disproportionately impacting vulnerable populations and linking human, animal, and environmental health through the One Health framework. In this review we explore the epidemiology of these diseases, particularly those that are underreported and highlight the complex transmission dynamics involving domestic and wild animal hosts. Climate change, urbanization, and deforestation exacerbate the emergence and reemergence of arthropod-borne parasitic diseases like malaria, leishmaniasis, and trypanosomiasis, complicating control and disease elimination efforts. Despite progress in managing certain diseases, gaps in surveillance and funding hinder effective responses, allowing many arthropod zoonotic parasitic infections to persist unnoticed. The increased interactions between humans and wildlife, driven by environmental changes, heighten the risk of spillover events. Leveraging comprehensive data on disease prevalence, distribution, and vector ecology, coupled with a One Health approach, is essential for developing adaptive surveillance systems and sustainable control strategies. This review emphasizes the urgent need for interdisciplinary collaboration among medical professionals, veterinarians, ecologists, and policymakers to effectively address the challenges posed by vector-borne parasitic diseases in Africa, ensuring improved health outcomes for both humans and animals.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Overview on Arthropod-Borne Parasitic Diseases in Africa

2.1. Human and Non-Human Primate Malaria

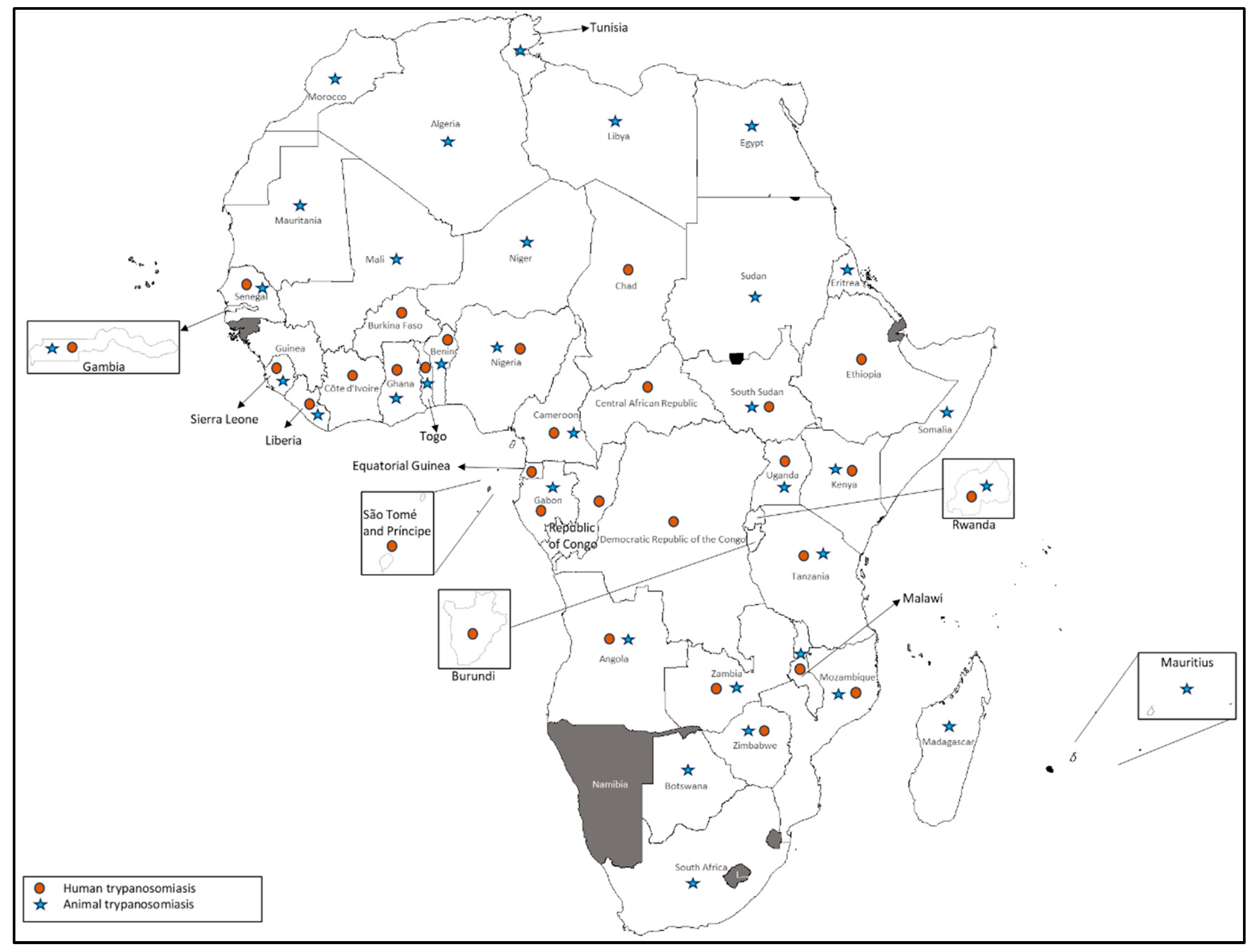

2.2. Human and Animal Trypanosomiasis

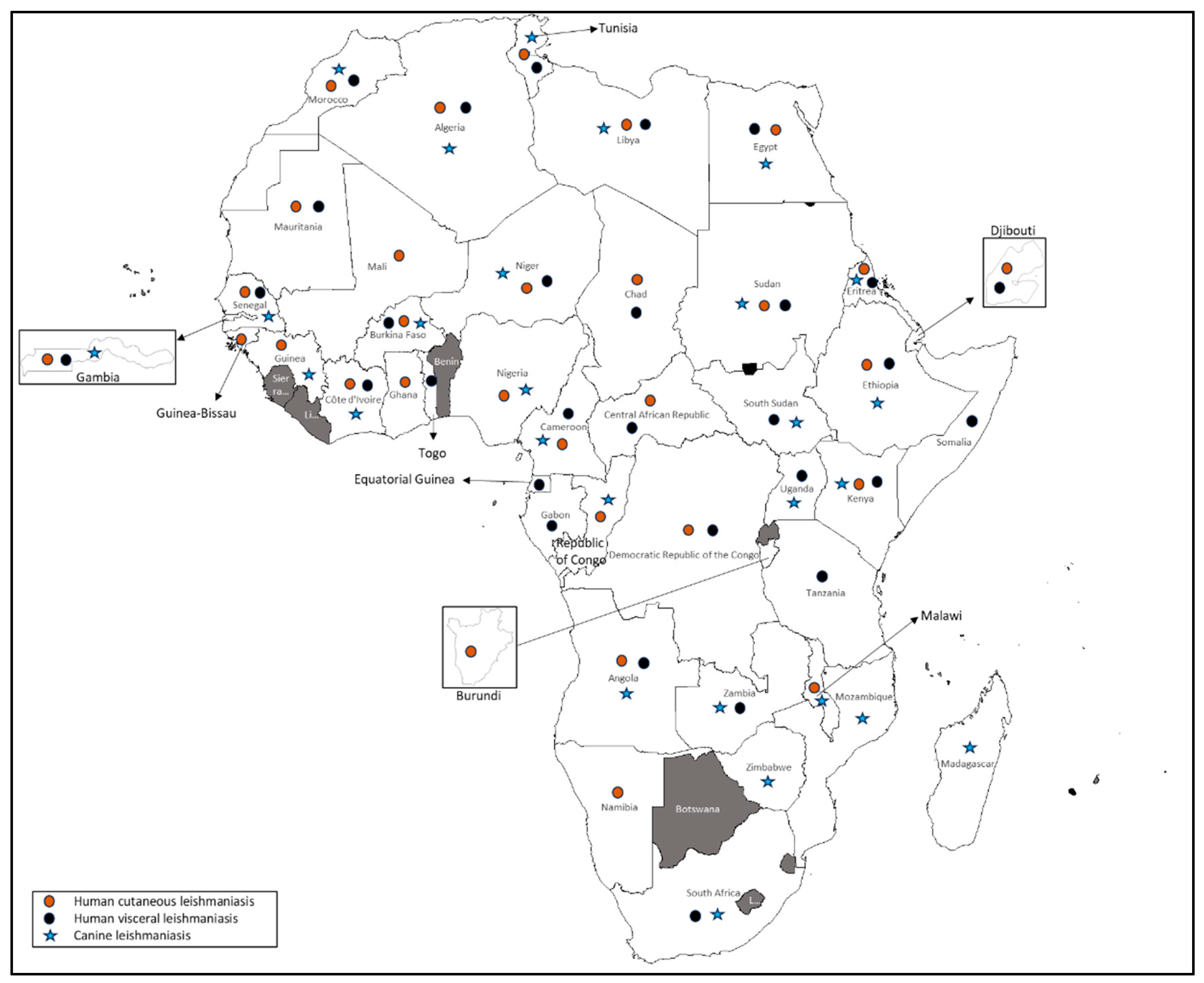

2.3. Human and Canine Leishmaniasis

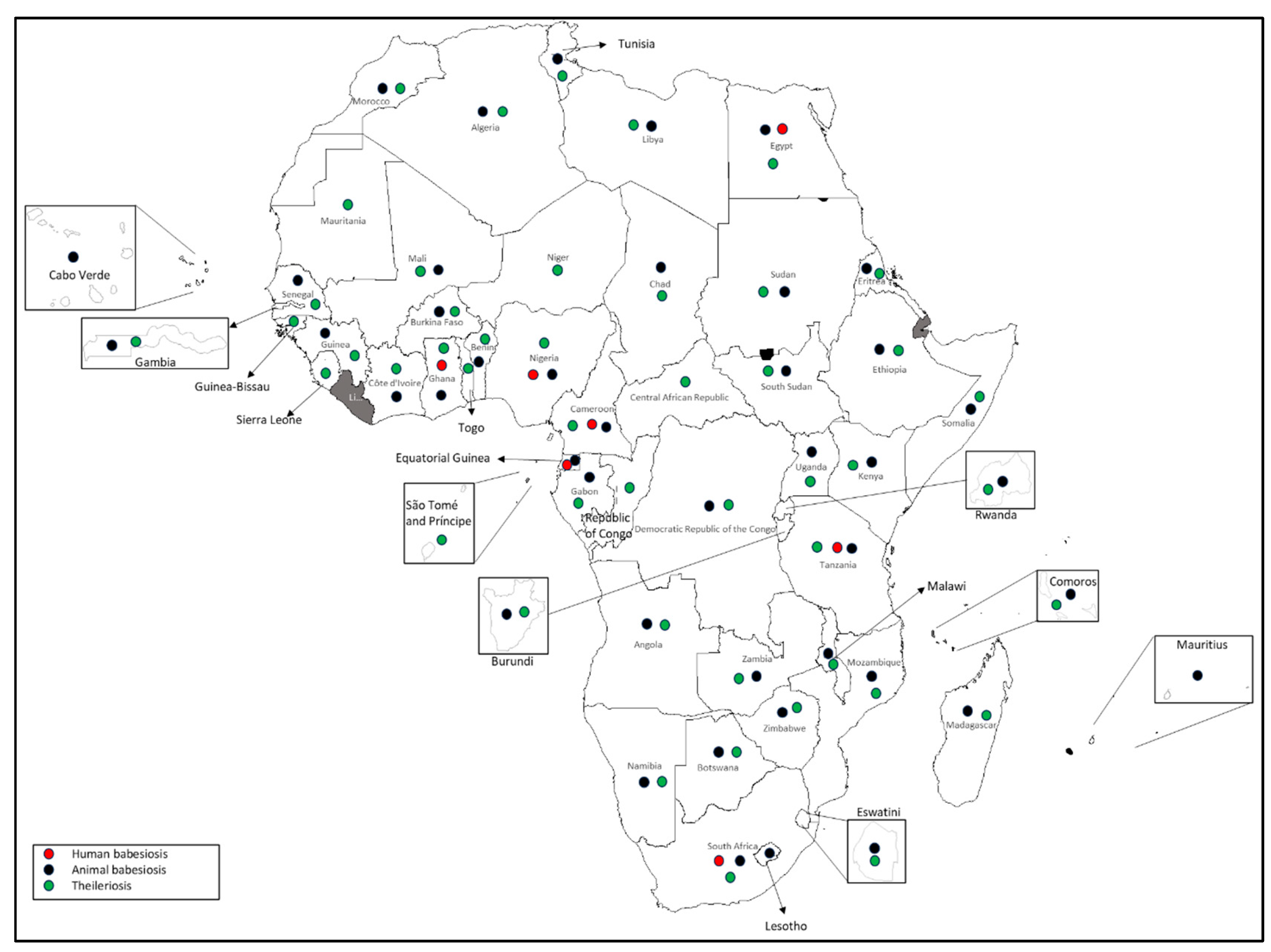

2.4. Human and Animal Babesiosis

2.5. Theileriosis

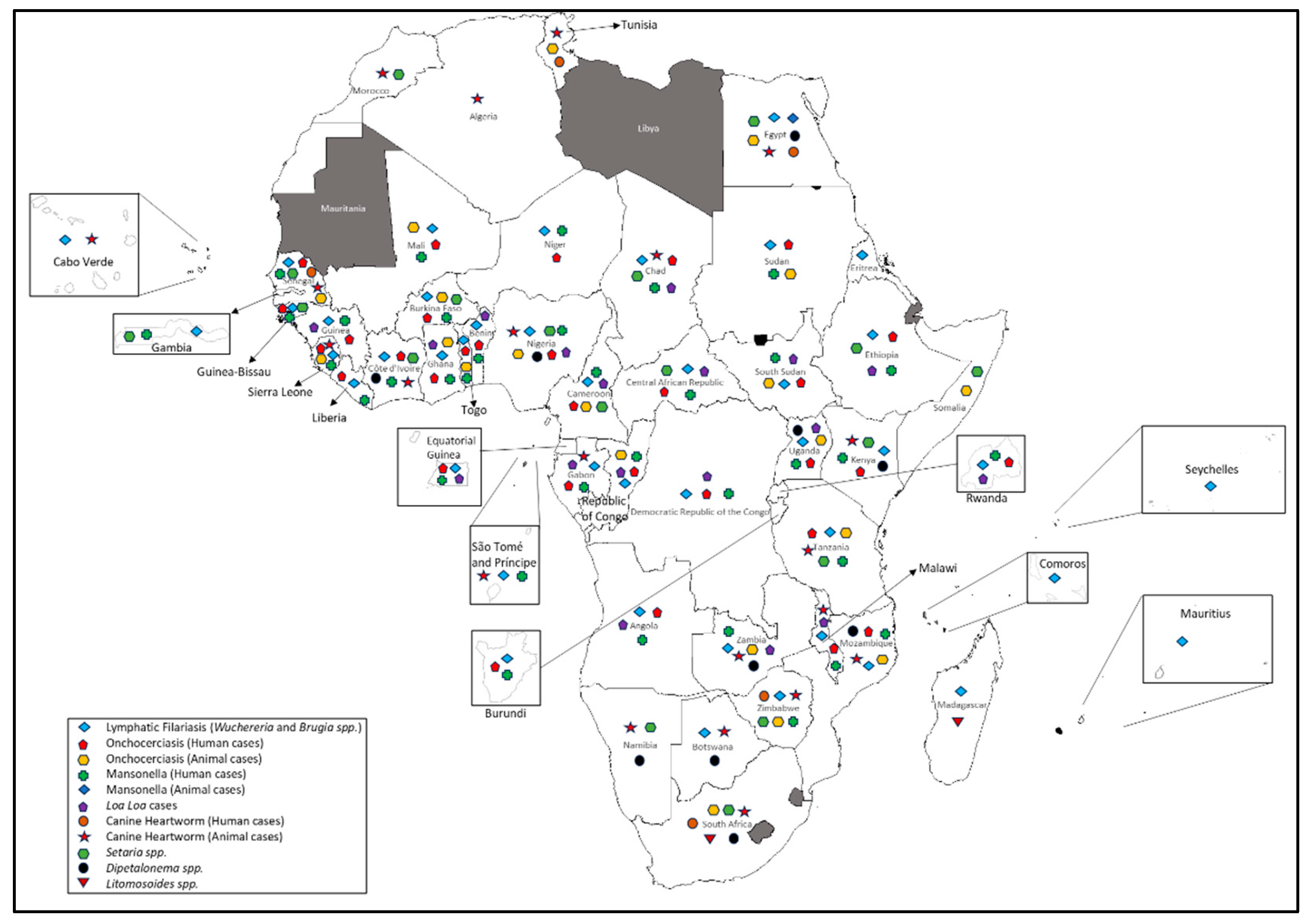

2.6. Filarial Diseases

2.6.1. Human and Animal Onchocerciasis

2.6.2. Lymphatic Filariasis

2.6.3. Loiasis

2.6.4. Mansonellosis

2.6.4. Canine Heartworm Disease

2.6.5. Other Animal Filarial Diseases

2.6.5.1. Setaria Species

2.6.5.2. Dipetalonema and Acanthocheilonema Species

2.6.5.3. Litomosoides Species

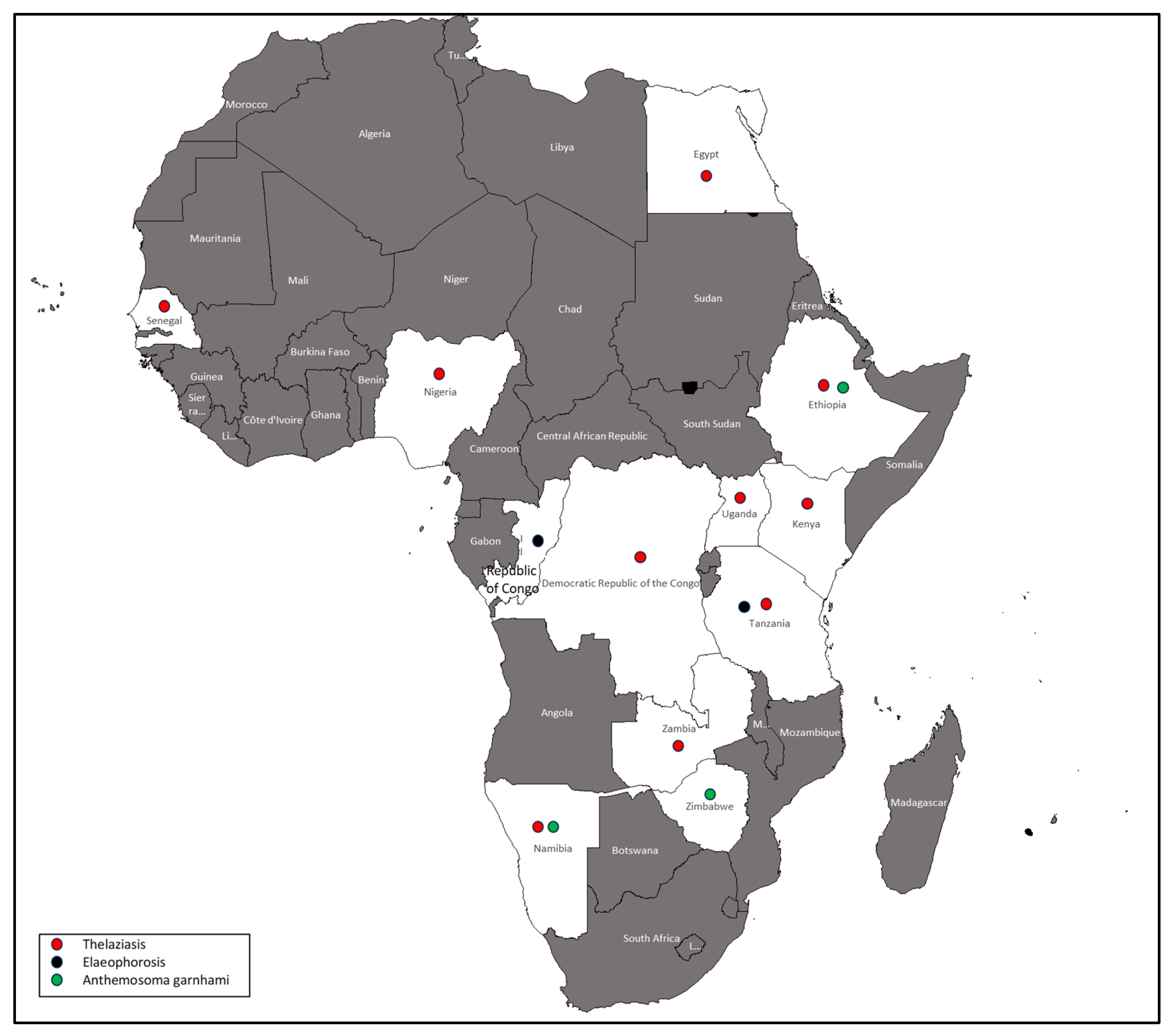

2.7. Thelaziasis

2.8. Elaeophorosis

2.9. Emerging Parasitic Disease

2.9.1. Anthemosoma garnhami

3. Current Knowledge of Prevalence and Diversity of Arthropod-Borne Parasitic Diseases in Africa and Its Implications in One Health

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAR | Central African Republic |

| CL | Cutaneous Leishmaniasis |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| DRC | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| HAT | Human African trypanosomiasis |

| IRS | indoor residual spraying |

| ITNs | insecticide-treated bed nets |

| mHealth | Mobile health |

| NHPs | non-human primates |

| SIT | sterile insect technique |

| VL | Visceral Leishmaniasis |

References

- Molyneux, D.H. Vector-Borne Parasitic Diseases--an Overview of Recent Changes. Int J Parasitol 1998, 28, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. A Global Brief on Vector-Borne Diseases; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, A.; Kuruvilla, S.; Borchert, M. Bridging the Implementation Gap between Knowledge and Action for Health. Bull World Health Organ 2004, 82, 724–731, discussion 732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bloom, D.E.; Cadarette, D. Infectious Disease Threats in the Twenty-First Century: Strengthening the Global Response. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.F.; Acevedo-Whitehouse, K.; Pedersen, A.B. The Role of Infectious Diseases in Biological Conservation. Animal Conservation 2009, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, D.H. Control of Human Parasitic Diseases: Context and Overview. Adv Parasitol 2006, 61, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, B.A.; Gubler, D.J. Disease Ecology and the Global Emergence of Zoonotic Pathogens. Environ Health Prev Med 2005, 10, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, P.J.; Cattadori, I.M.; Boag, B.; Dobson, A.P. Climate Disruption and Parasite-Host Dynamics: Patterns and Processes Associated with Warming and the Frequency of Extreme Climatic Events. J Helminthol 2006, 80, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, S. Host–Parasite Interactions and Climate Change. In Effects of Climate Change on Birds; Dunn, P.O., Møller, A.P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2019; pp. 187–198. ISBN 978-0-19-882426-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, P.T.; Valdivia, H.O.; de Oliveira, T.C.; Alves, J.M.P.; Duarte, A.M.R.C.; Cerutti-Junior, C.; Buery, J.C.; Brito, C.F.A.; de Souza, J.C.J.; Hirano, Z.M.B.; et al. Human Migration and the Spread of Malaria Parasites to the New World. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2024: Addressing Inequity in the Global Malaria Response. Geneva, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, P.; Hall, L. Malaria on the Move: Human Population Movement and Malaria Transmission. Emerging infectious diseases 2000, 6, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schantz-Dunn, J.; Nour, N.M. Malaria and Pregnancy: A Global Health Perspective. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2009, 2, 186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Mahanay, F.J.; Bashein, A.M.; EI-Buni, A.A.; Sheebah, A.; Annajar, B.B. Malaria in Illegal Immigrants in Southern Libya. Libyan Journal of Medical Sciences 2021, 5, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, R.; Antinori, S.; Meroni, L.; Menegon, M.; Severini, C. A Case of Plasmodium Malariae Recurrence: Recrudescence or Reinfection? Malaria Journal 2019, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, D.M.; Hussein, H.M.; El Gozamy, B.M.R.; Thabet, H.S.; Hassan, M.A.; Meselhey, R.A.-A. Screening of Plasmodium Parasite in Vectors and Humans in Three Villages in Aswan Governorate, Egypt. Journal of parasitic diseases 2019, 43, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saoud, M.; Ezzariga, N.; Benaissa, E.; Moustachi, A.; Lyagoubi, M.; Aoufi, S. Imported Malaria: 54 Cases Diagnosed at the Ibn Sina Hospital Center in Rabat, Morocco. Médecine et Santé Tropicales 2019, 29, 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- Nabah, K.; Mezzoug, N.; Aarab, A.; Oufdou, H.; Rharrabe, K. Epidemiological Profile of the Imported Malaria in the North Region of Morocco from 2014 to 2018. EDP Sciences 2021, 319, 01057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, K.; Siala, E.; Tchibkere, D.; Zallagua, N.; Chahed, M.; Bouratbine, A. Imported Malaria in Tunisia: Consequences on the Risk of Resurgence of the Disease. Medecine Tropicale: Revue du Corps de Sante Colonial 2010, 70, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DePina, A.J.; Stresman, G.; Barros, H.S.B.; Moreira, A.L.; Dia, A.K.; Furtado, U.D.; Faye, O.; Seck, I.; Niang, E.H.A. Updates on Malaria Epidemiology and Profile in Cabo Verde from 2010 to 2019: The Goal of Elimination. Malaria journal 2020, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboobakar, S.; Tatarskv, A.; Cohen, J.M.; Bheecarry, A.; Boolaky, P.; Gopee, N.; Moonasar, D.; Phillips, A.A.; Kahn, J.G.; Moonen, B. Eliminating Malaria and Preventing Its Reintroduction: The Mauritius Case Study. Malaria Journal 2012, 11, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovet, P.; Gédéon, J.; Louange, M.; Durasnel, P.; Aubry, P.; Gauzere, B. Health Situation and Issues in the Seychelles in 2012. Med. Sante Trop 2013, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algeria: Epidemic - 09-2024 - South Algeria Malaria and Diphtheria (2024-10-04) - Algeria | ReliefWeb. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/algeria/algeria-epidemic-09-2024-south-algeria-malaria-and-diphtheria-2024-10-04 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Sinka, M.E.; Bangs, M.J.; Manguin, S.; Rubio-Palis, Y.; Chareonviriyaphap, T.; Coetzee, M.; Mbogo, C.M.; Hemingway, J.; Patil, A.P.; Temperley, W.H. A Global Map of Dominant Malaria Vectors. Parasites & vectors 2012, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Kim Sung, L.; Matusop, A.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Shamsul, S.S.G.; Cox-Singh, J.; Thomas, A.; Conway, D.J. A Large Focus of Naturally Acquired Plasmodium Knowlesi Infections in Human Beings. Lancet 2004, 363, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalremruata, A.; Magris, M.; Vivas-Martínez, S.; Koehler, M.; Esen, M.; Kempaiah, P.; Jeyaraj, S.; Perkins, D.J.; Mordmüller, B.; Metzger, W.G. Natural Infection of Plasmodium Brasilianum in Humans: Man and Monkey Share Quartan Malaria Parasites in the Venezuelan Amazon. EBioMedicine 2015, 2, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, P.; Zalis, M.G.; de Pina-Costa, A.; Siqueira, A.M.; Júnior, C.B.; Silva, S.; Areas, A.L.L.; Pelajo-Machado, M.; de Alvarenga, D.A.M.; da Silva Santelli, A.C.F.; et al. Outbreak of Human Malaria Caused by Plasmodium Simium in the Atlantic Forest in Rio de Janeiro: A Molecular Epidemiological Investigation. Lancet Glob Health 2017, 5, e1038–e1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinton, J.; Mulligan, H. A Critical Review of the Literature relating to the Identification of the Malarial Parasites recorded from Monkeys of the Families Cercopithecidae and Colobidae. Records of the Malaria Survey of India 1932, 3, 357–380. [Google Scholar]

- Poirriez, J.; Dei-Cas, E.; Landau, I. Further Description of Blood Stages of Plasmodium Petersi from Cercocebus Albigena Monkey. Folia Parasitol (Praha) 1994, 41, 168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Poirriez, J.; Baccam, D.; Dei-Cas, E.; Brogan, T.; Landau, I. Description de Plasmodium Petersi n. Sp. et Plasmodium Georgesi n. Sp., Parasites d’un Cercocebus Albigena Originaire de République Centrafricaine. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 1993, 68, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prugnolle, F.; Ollomo, B.; Durand, P.; Yalcindag, E.; Arnathau, C.; Elguero, E.; Berry, A.; Pourrut, X.; Gonzalez, J.-P.; Nkoghe, D.; et al. African Monkeys Are Infected by Plasmodium Falciparum Nonhuman Primate-Specific Strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 11948–11953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, A.A.; Freeland, D.E.; Collins, W.E.; Lal, A.A. The Evolution of Primate Malaria Parasites Based on the Gene Encoding Cytochrome b from the Linear Mitochondrial Genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 8124–8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomainen, U.; Candolin, U. Behavioural Responses to Human-Induced Environmental Change. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2011, 86, 640–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassell, J.M.; Begon, M.; Ward, M.J.; Fèvre, E.M. Urbanization and Disease Emergence: Dynamics at the Wildlife-Livestock-Human Interface. Trends Ecol Evol 2017, 32, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewara, A.; Sreenivasan, P.; Khurana, S. Primate Malaria of Human Importance. Trop Parasitol 2023, 13, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imwong, M.; Madmanee, W.; Suwannasin, K.; Kunasol, C.; Peto, T.J.; Tripura, R.; von Seidlein, L.; Nguon, C.; Davoeung, C.; Day, N.P.J.; et al. Asymptomatic Natural Human Infections With the Simian Malaria Parasites Plasmodium Cynomolgi and Plasmodium Knowlesi. J Infect Dis 2019, 219, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prugnolle, F.; Durand, P.; Neel, C.; Ollomo, B.; Ayala, F.J.; Arnathau, C.; Etienne, L.; Mpoudi-Ngole, E.; Nkoghe, D.; Leroy, E.; et al. African Great Apes Are Natural Hosts of Multiple Related Malaria Species, Including Plasmodium Falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 1458–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, S. Malaria in Chimpanzees in Sierra Leone. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology 1923, 17, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, C.; Dobson, A.P. Primate Malarias: Diversity, Distribution and Insights for Zoonotic Plasmodium. One Health 2015, 1, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagni, R.; Novara, R.; Minardi, M.L.; Frallonardo, L.; Panico, G.G.; Pallara, E.; Cotugno, S.; Ascoli Bartoli, T.; Guido, G.; De Vita, E.; et al. Human African Trypanosomiasis (Sleeping Sickness): Current Knowledge and Future Challenges. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, F.E.G. History of Sleeping Sickness (African Trypanosomiasis). Infect Dis Clin North Am 2004, 18, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, C.S.; Stone, C.M.; Steinmann, P.; Tanner, M.; Tediosi, F. Seeing beyond 2020: An Economic Evaluation of Contemporary and Emerging Strategies for Elimination of Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense. The Lancet Global Health 2017, 5, e69–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanga, C.H. Cost Effective Control of Zoonotic African Trypanosomiasis in Kenya: Analysing Underreporting Factors and Modeling Prevalence in Busia Foci. Thesis, University of Nairobi, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rock, K.S.; Stone, C.M.; Hastings, I.M.; Keeling, M.J.; Torr, S.J.; Chitnis, N. Mathematical Models of Human African Trypanosomiasis Epidemiology. Adv Parasitol 2015, 87, 53–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordani, F.; Morrison, L.J.; Rowan, T.G.; DE Koning, H.P.; Barrett, M.P. The Animal Trypanosomiases and Their Chemotherapy: A Review. Parasitology 2016, 143, 1862–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tihon, E.; Imamura, H.; Dujardin, J.; Van Den Abbeele, J.; Van den Broeck, F. Discovery and Genomic Analyses of Hybridization between Divergent Lineages of Trypanosoma Congolense, Causative Agent of Animal African Trypanosomiasis. Molecular ecology 2017, 26, 6524–6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadioli, F.A.; Barnabé, P.d.A.; Machado, R.Z.; Teixeira, M.C.A.; André, M.R.; Sampaio, P.H.; Fidélis Junior, O.L.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; Marques, L.C. First Report of Trypanosoma Vivax Outbreak in Dairy Cattle in São Paulo State, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária 2012, 21, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, J.; Mohammed, G.; Gibson, W. Trypanosoma (Nannomonas) Godfreyi Sp. Nov. from Tsetse Flies in The Gambia: Biological and Biochemical Characterization. Parasitology 1994, 109, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimpaye, H.; Njiokou, F.; Njine, T.; Njitchouang, G.; Cuny, G.; Herder, S.; Asonganyi, T.; Simo, G. Trypanosoma Vivax, T. Congolense “Forest Type” and T. Simiae: Prevalence in Domestic Animals of Sleeping Sickness Foci of Cameroon. Parasite: Journal de la Société Française de Parasitologie 2011, 18, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berriman, M.; Ghedin, E.; Hertz-Fowler, C.; Blandin, G.; Renauld, H.; Bartholomeu, D.C.; Lennard, N.J.; Caler, E.; Hamlin, N.E.; Haas, B. The Genome of the African Trypanosome Trypanosoma Brucei. science 2005, 309, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P. A Case of Infection by Trypanosoma Lewisi in a Child. 1933.

- Janssen, J.; Wijers, D. Trypanosoma Simiae at the Kenya Coast. A Correlation between Virulence and the Transmitting Species of Glossina. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology 1974, 68, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, R.; Gibson, W. Rediscovery of Trypanosoma (Pycnomonas) Suis, a Tsetse-Transmitted Trypanosome Closely Related to T. Brucei. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2015, 36, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotánková, A.; Fialová, M.; Čepička, I.; Brzoňová, J.; Svobodová, M. Trypanosomes of the Trypanosoma Theileri Group: Phylogeny and New Potential Vectors. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. Trypanosoma Uniforme-Trypanosoma Vivax Infections in Bovines and Trypanosoma Uniforme Infections in Goats and Sheep at Entebbe, Uganda. Parasitology 1949, 39, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, R.; Hecker, H.; Lun, Z.-R. Trypanosoma Evansi and T. Equiperdum: Distribution, Biology, Treatment and Phylogenetic Relationship (a Review). Veterinary parasitology 1998, 79, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boushaki, D.; Adel, A.; Dia, M.L.; Büscher, P.; Madani, H.; Brihoum, B.A.; Sadaoui, H.; Bouayed, N.; Issad, N.K. Epidemiological Investigations on Trypanosoma Evansi Infection in Dromedary Camels in the South of Algeria. Heliyon 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennoune, O.; Adili, N.; Amri, K.; Bennecib, L.; Ayachi, A. Trypanosomiasis of Camels (Camelus Dromedarius) in Algeria: First Report; Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Urmia University: Urmia, Iran, 2013; Vol. 4, p. 273. [Google Scholar]

- Medkour, H.; Laidoudi, Y.; Lafri, I.; Davoust, B.; Mekroud, A.; Bitam, I.; Mediannikov, O. Canine Vector-Borne Protozoa: Molecular and Serological Investigation for Leishmania Spp., Trypanosoma Spp., Babesia Spp., and Hepatozoon Spp. in Dogs from Northern Algeria. Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports 2020, 19, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truc, P.; Grébaut, P.; Lando, A.; Makiadi Donzoau, F.; Penchenier, L.; Herder, S.; Geiger, A.; Vatunga, G.; Josenando, T. Epidemiological Aspects of the Transmission of the Parasites Causing Human African Trypanosomiasis in Angola. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology 2011, 105, 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Perich, P. Trypanosoma Rhodesiense African Human Trypanosomiasis Foci in Burundi (Vector: Glossina Morsitans). Historic and Present Aspects (Author’s Transl). Medecine Tropicale: Revue du Corps de Sante Colonial 1982, 42, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soha, S.; SouaÃ, F.; Issaka, Y.A.K.; Jacques, D.T. African Animal Trypanosomosis in Cattle in Bnin: A Review. Journal of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Health 2019, 11, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Dobigny, G.; Gauthier, P.; Houéménou, G.; Dossou, H.; Badou, S.; Etougbétché, J.; Tatard, C.; Truc, P. Spatio-Temporal Survey of Small Mammal-Borne Trypanosoma Lewisi in Cotonou, Benin, and the Potential Risk of Human Infection. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2019, 75, 103967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Losho, T.; Malau, M.; Mangate, K.; Linchwe, K.; Amanfu, W.; Motsu, T. The Resurgence of Trypanosomosis in Botswana. Journal of the South African Veterinary Association 2001, 72, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambire, R.; Lingue, K.; Courtin, F.; Sidibe, I.; Kiendrebeogo, D.; N’gouan, K.; Blé, L.; Kaba, D.; Koffi, M.; Solano, P. Human African Trypanosomiasis in Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso: Optimization of Epidemiologic Surveillance Strategies. Parasite (Paris, France) 2012, 19, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simo, G.; Mbida, J.A.M.; Eyenga, V.E.; Asonganyi, T.; Njiokou, F.; Grébaut, P. Challenges towards the Elimination of Human African Trypanosomiasis in the Sleeping Sickness Focus of Campo in Southern Cameroon. Parasites & vectors 2014, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, P.; Njiokou, F.; Mamoudou, A.; Ahmadou, T.; Mouhaman, A.; Garabed, R. Bovine Trypanosomiasis in Tsetse-Free Pastoral Zone of the Far-North Region, Cameroon. Journal of Vector Borne Diseases 2017, 54, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simarro, P.P.; Cecchi, G.; Franco, J.R.; Paone, M.; Fèvre, E.M.; Diarra, A.; Postigo, J.A.R.; Mattioli, R.C.; Jannin, J.G. Risk for Human African Trypanosomiasis, Central Africa, 2000–2009. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2011, 17, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappuis, F.; Lima, M.A.; Flevaud, L.; Ritmeijer, K. Human African Trypanosomiasis in Areas without Surveillance. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2010, 16, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourchakbe, J.; Zebaze, A.A.T.; Tagueu, S.K.; Kodindo, I.D.; Padja, A.B.; Simo, G. Diversity of Trypanosome Species in Small Ruminants, Dogs and Pigs from Three Sleeping Sickness Foci of the South of Chad. Parasitology International 2023, 96, 102772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vourchakbé, J.; Tiofack, A.A.Z.; Kante, S.T.; Barka, P.A.; Simo, G. Prevalence of Pathogenic Trypanosome Species in Naturally Infected Cattle of Three Sleeping Sickness Foci of the South of Chad. Plos one 2022, 17, e0279730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bemba, I.; Bamou, R.; Lenga, A.; Okoko, A.; Awono-Ambene, P.; Antonio-Nkondjio, C. Review of the Situation of Human African Trypanosomiasis in the Republic of Congo From the 1950s to 2020. Journal of Medical Entomology 2022, 59, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Djetchi, M.K.; Ilboudo, H.; Koffi, M.; Kaboré, J.; Kaboré, J.W.; Kaba, D.; Courtin, F.; Coulibaly, B.; Fauret, P.; Kouakou, L. The Study of Trypanosome Species Circulating in Domestic Animals in Two Human African Trypanosomiasis Foci of Cote d’Ivoire Identifies Pigs and Cattle as Potential Reservoirs of Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2017, 11, e0005993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumbala, C.; Simarro, P.P.; Cecchi, G.; Paone, M.; Franco, J.R.; Kande Betu Ku Mesu, V.; Makabuza, J.; Diarra, A.; Chansy, S.; Priotto, G. Human African Trypanosomiasis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Disease Distribution and Risk. International journal of health geographics 2015, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boodman, C.; Libman, M.; Ndao, M.; Yansouni, C.P. Case Report: Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense Human African Trypanosomiasis as the Cause of Fever in an Inpatient with Multiple Myeloma and HIV-1 Coinfection. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2019, 101, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, S.A.E.-S.; El-Adl, M.A.; Ali, M.O.; Al-Araby, M.; Omar, M.A.; El-Beskawy, M.; Sorour, S.S.; Rizk, M.A.; Elgioushy, M. Molecular Detection and Identification of Babesia Bovis and Trypanosoma Spp. in One-Humped Camel (Camelus Dromedarius) Breeds in Egypt. Veterinary world 2021, 14, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhaig, M.M.; Selim, A.; Mahmoud, M.M.; El-Gayar, E.K. Molecular Confirmation of Trypanosoma Evansi and Babesia Bigemina in Cattle from Lower Egypt. Pakistan Veterinary Journal 2016, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Cordon-Obras, C.; Rodriguez, Y.F.; Fernandez-Martinez, A.; Cano, J.; Ndong-Mabale, N.; Ncogo-Ada, P.; Ndongo-Asumu, P.; Aparicio, P.; Navarro, M.; Benito, A. Molecular Evidence of a Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense Sylvatic Cycle in the Human African Trypanosomiasis Foci of Equatorial Guinea. Frontiers in microbiology 2015, 6, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordon-Obras, C.; Berzosa, P.; Ndong-Mabale, N.; Bobuakasi, L.; Buatiche, J.; Ndongo-Asumu, P.; Benito, A.; Cano, J. Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense in Domestic Livestock of Kogo and Mbini Foci (Equatorial Guinea). Tropical Medicine & International Health 2009, 14, 535–541. [Google Scholar]

- Martoglio, F. Trypanosomiasis of the Dromedary in Eritrea. 1913.

- Domizio, G.D. A Trypanosomiasis (Gudhò) of Eritrean Dromedaries. Notes on Blood-Sucking Flies of the Colony of Eritrea. 1918.

- Gelaye, A.; Fesseha, H. Bovine Trypanosomiasis in Ethiopia: Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Its Economic Impact-a Review. Open Access Journal of Biogeneric Science and Research 2020, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, A.; Mamecha, T.; Abose, E.; Bokicho, B.; Ashole, A.; Bishaw, T.; Mariyo, A.; Bogale, B.; Terefe, H.; Tadesse, H. Reemergence of Human African Trypanosomiasis Caused by Trypanosoma Brucei Rhodesiense, Ethiopia. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2024, 30, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boundenga, L.; Mombo, I.M.; Augustin, M.-O.; Barthélémy, N.; Nzassi, P.M.; Moukodoum, N.D.; Rougeron, V.; Prugnolle, F. Molecular Identification of Trypanosome Diversity in Domestic Animals Reveals the Presence of Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense in Historical Foci of Human African Trypanosomiasis in Gabon. Pathogens 2022, 11, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iroungou, B.A.; Boundenga, L.; Guignali Mangouka, L.; Bivigou-Mboumba, B.; Nzenze, J.R.; Maganga, G.D. Human African Trypanosomiasis in Two Historical Foci of the Estuaire Province, Gabon: A Case Report. SAGE Open Medical Case Reports 2020, 8, 2050313X20959890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekloh, W.; Sunter, J.D.; Gwira, T.M. African Trypanosome Infection Patterns in Cattle in a Farm Setting in Southern Ghana. Acta tropica 2023, 237, 106721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, I.; Patel, T.; Shah, J.; Venkatesan, P. West-African Trypanosomiasis in a Returned Traveller from Ghana: An Unusual Cause of Progressive Neurological Decline. Case Reports 2014, 2014, bcr2014204451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, O.; Camara, M.; Falzon, L.C.; Ilboudo, H.; Kaboré, J.; Compaoré, C.F.A.; Fèvre, E.M.; Büscher, P.; Bucheton, B.; Lejon, V. Performance of Clinical Signs and Symptoms, Rapid and Reference Laboratory Diagnostic Tests for Diagnosis of Human African Trypanosomiasis by Passive Screening in Guinea: A Prospective Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2023, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivali, V.; Kiyong’a, A.N.; Fyfe, J.; Toye, P.; Fèvre, E.M.; Cook, E.A. Spatial Distribution of Trypanosomes in Cattle from Western Kenya. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2020, 7, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remme, J.H.; Feenstra, P.; Lever, P.; Medici, A.C.; Morel, C.M.; Noma, M.; Ramaiah, K.; Richards, F.; Seketeli, A.; Schmunis, G. Tropical Diseases Targeted for Elimination: Chagas Disease, Lymphatic Filariasis, Onchocerciasis, and Leprosy. International Journal of Biomedical and Health Sciences 2021, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, G.W.; Miller, M.J. Human Trypanosomiasis in Northeastern Liberia. 1955.

- Mehlitz, D.; Gangpala, L. Sleeping Sickness in Liberia–a Historical Review. Sierra Leone Journal of Biomedical Research 2017, 9, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mehlitz, D. Trypanosome Infections in Domestic Animals in Liberia. Tropenmedizin und Parasitologie 1979, 30, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- LIBYA, I. DETECTION OF TRYPANOSOMA EVANSI IN DROMEDARY CAMELS.

- Rasoanoro, M.; Ramasindrazana, B.; Goodman, S.M.; Rajerison, M.; Randrianarivelojosia, M. A Review of Trypanosoma Species Known from Malagasy Vertebrates. Malagasy Natiora 2019, 13, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoanoro, M.; Goodman, S.M.; Randrianarivelojosia, M.; Soarimalala, V.; Ramasindrazana, B. Trypanosoma Infection in Terrestrial Small Mammals from the Central Highlands of Madagascar.

- Simarro, P.P.; Cecchi, G.; Paone, M.; Franco, J.R.; Diarra, A.; Ruiz, J.A.; Fèvre, E.M.; Courtin, F.; Mattioli, R.C.; Jannin, J.G. The Atlas of Human African Trypanosomiasis: A Contribution to Global Mapping of Neglected Tropical Diseases. International journal of health geographics 2010, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsela, M.; Hayashida, K.; Nakao, R.; Chatanga, E.; Gaithuma, A.K.; Naoko, K.; Musaya, J.; Sugimoto, C.; Yamagishi, J. Molecular Identification of Trypanosomes in Cattle in Malawi Using PCR Methods and Nanopore Sequencing: Epidemiological Implications for the Control of Human and Animal Trypanosomiases. Parasite 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frean, J.; Sieling, W.; Pahad, H.; Shoul, E.; Blumberg, L. Clinical Management of East African Trypanosomiasis in South Africa: Lessons Learned. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2018, 75, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modibo Diakité; Brahima Sacko; Chaka Traore; Youssouf Gouro Diall; Amadou Sery; Mama Diarra; Oumar Marico; Fily Sissoko; Sekouba Bengaly Study of Bovine Trypanosomiasis in Mali: Case of the Kita Region. World J. Bio. Pharm. Health Sci. 2024, 20, 401–406. [CrossRef]

- Schwan, T.G.; Lopez, J.E.; Safronetz, D.; Anderson, J.M.; Fischer, R.J.; Maïga, O.; Sogoba, N. Fleas and Trypanosomes of Peridomestic Small Mammals in Sub-Saharan Mali. Parasites & vectors 2016, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lamine, D.M. Epidemiology of Camel Trypanosomosis Due to Trypanosoma Evansi in Mauritania and Its Control Strategies for Sustainable Livestock Production. 2009.

- Desquesnes, M.; Holzmuller, P.; Lai, D.-H.; Dargantes, A.; Lun, Z.-R.; Jittaplapong, S. Trypanosoma Evansi and Surra: A Review and Perspectives on Origin, History, Distribution, Taxonomy, Morphology, Hosts, and Pathogenic Effects. BioMed research international 2013, 2013, 194176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rami, M.; Atarhouch, T.; Bendahman, M.; Azlaf, R.; Kechna, R.; Dakkak, A. Camel Trypanosomosis in Morocco: 2. A Pilot Disease Control Trial. Veterinary parasitology 2003, 115, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, E. Prevalence of Bovine Trypanosomosis in Central Mozambique from 2002 to 2005. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 2008, 75, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TSETSE CONTROL TO ASSIST LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fishery/docs/CDrom/aquaculture/a0845t/volume2/docrep/field/383559.htm (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Tatard, C.; Garba, M.; Gauthier, P.; Hima, K.; Artige, E.; Dossou, D.; Gagaré, S.; Genson, G.; Truc, P.; Dobigny, G. Rodent-Borne Trypanosoma from Cities and Villages of Niger and Nigeria: A Special Role for the Invasive Genus Rattus? Acta Tropica 2017, 171, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odebunmi, E.; Ibeachu, C.; Chukwudi, C.U. Prevalence of Human and Animal African Trypanosomiasis in Nigeria: A Scoping Review. medRxiv 2024, 2024–04. [Google Scholar]

- Habeeb, I.F.; Chechet, G.D.; Kwaga, J.K. Molecular Identification and Prevalence of Trypanosomes in Cattle Distributed within the Jebba Axis of the River Niger, Kwara State, Nigeria. Parasites & vectors 2021, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gashururu S, R.; Maingi, N.; Githigia, S.M.; Gasana, M.N.; Odhiambo, P.O.; Getange, D.O.; Habimana, R.; Cecchi, G.; Zhao, W.; Gashumba, J. Occurrence, Diversity and Distribution of Trypanosoma Infections in Cattle around the Akagera National Park, Rwanda. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021, 15, e0009929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gashururu, R.S.; Maingi, N.; Githigia, S.M.; Getange, D.O.; Ntivuguruzwa, J.B.; Habimana, R.; Cecchi, G.; Gashumba, J.; Bargul, J.L.; Masiga, D.K. Trypanosomes Infection, Endosymbionts, and Host Preferences in Tsetse Flies (Glossina Spp.) Collected from Akagera Park Region, Rwanda: A Correlational Xenomonitoring Study. One Health 2023, 16, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo Moura Da Silva, E.L. Tropical Medicine behind Cocoa Slavery: A Campaign to Eradicate Sleeping Sickness in the Portuguese Colony of Príncipe Island, 1911-1914. Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, B.F.B. Sleeping Sickness; a Record of Four Years’ War against It in Principe, Portuguese West Africa; Baillière, Tindall and Cox, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Desquesnes, M.; Ravel, S.; Deschamps, J.-Y.; Polack, B.; Roux, F. Atypical Hyperpachymorph Trypanosoma (Nannomonas) Congolense Forest-Type in a Dog Returning from Senegal. Parasite 2012, 19, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seck, M.T.; Bouyer, J.; Sall, B.; Bengaly, Z.; Vreysen, M.J. The Prevalence of African Animal Trypanosomoses and Tsetse Presence in Western Senegal. 2010.

- Human African Trypanosomiasis (Sleeping Sickness). Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/human-african-trypanosomiasis (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Sudarshi, D.; Lawrence, S.; Pickrell, W.O.; Eligar, V.; Walters, R.; Quaderi, S.; Walker, A.; Capewell, P.; Clucas, C.; Vincent, A. Human African Trypanosomiasis Presenting at Least 29 Years after Infection—What Can This Teach Us about the Pathogenesis and Control of This Neglected Tropical Disease? PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2014, 8, e3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorward, D.C.; Payne, A. Deforestation, the Decline of the Horse, and the Spread of the Tsetse Fly and Trypanosomiasis (Nagana) in Nineteenth Century Sierra Leone. The Journal of African History 1975, 16, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan-Kadle, A.A.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Nyingilili, H.S.; Yusuf, A.A.; Vieira, R.F. Parasitological and Molecular Detection of Trypanosoma Spp. in Cattle, Goats and Sheep in Somalia. Parasitology 2020, 147, 1786–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latif, A.A.; Ntantiso, L.; De Beer, C. African Animal Trypanosomosis (Nagana) in Northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Strategic Treatment of Cattle on a Farm in Endemic Area. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 2019, 86, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Postigo, J.A.; Franco, J.R.; Lado, M.; Simarro, P.P. Human African Trypanosomiasis in South Sudan: How Can We Prevent a New Epidemic? PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2012, 6, e1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archibald, R. A Trypanosome of Cattle in the Southern Sudan. Journal of Comparative Pathology and Therapeutics 1912, 25, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossaad, E.; Ismail, A.A.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Musinguzi, P.; Angara, T.E.; Xuan, X.; Inoue, N.; Suganuma, K. Prevalence of Different Trypanosomes in Livestock in Blue Nile and West Kordofan States, Sudan. Acta Tropica 2020, 203, 105302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, L.C.; Kaare, M.T.; Welburn, S.C.; Picozzi, K. Domestic Pigs as Potential Reservoirs of Human and Animal Trypanosomiasis in Northern Tanzania. Parasites & Vectors 2013, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kargbo, A.; Ebiloma, G.U.; Ibrahim, Y.K.E.; Chechet, G.D.; Jeng, M.; Balogun, E.O. Epizootiology and Molecular Identification of Trypanosome Species in Livestock Ruminants in The Gambia. Acta Parasitologica 2022, 67, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, M. The Epidemiology of Human Trypanosomiasis in British West Africa: II.—The Gambia. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology 1953, 47, 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Tchamdja, E.; Kulo, A.; Vitouley, H.; Batawui, K.; Bankolé, A.; Adomefa, K.; Cecchi, G.; Hoppenheit, A.; Clausen, P.; De Deken, R. Cattle Breeding, Trypanosomosis Prevalence and Drug Resistance in Northern Togo. Veterinary parasitology 2017, 236, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaki, E.; Dao, B.; Dayo, G.; Alfa, E.; N’Feide, T. Trypanosomoses Animales Dans La Plaine de Mô Au Togo. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences 2014, 8, 2462–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjeibi, M.R.; Hamida, T.B.; Dalgatova, Z.; Mahjoub, T.; Rejeb, A.; Dridi, W.; Gharbi, M. First Report of Surra (Trypanosoma Evansi Infection) in a Tunisian Dog. Parasite 2015, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmi, R.; Dhibi, M.; Ben Said, M.; Ben Yahia, H.; Abdelaali, H.; Ameur, H.; Baccouche, S.; Gritli, A.; Mhadhbi, M. Evidence of Natural Infections with Trypanosoma, Anaplasma and Babesia Spp. in Military Livestock from Tunisia. 2019.

- Muhanguzi, D.; Mugenyi, A.; Bigirwa, G.; Kamusiime, M.; Kitibwa, A.; Akurut, G.G.; Ochwo, S.; Amanyire, W.; Okech, S.G.; Hattendorf, J. African Animal Trypanosomiasis as a Constraint to Livestock Health and Production in Karamoja Region: A Detailed Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment. BMC veterinary research 2017, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katakura, K.; Lubinga, C.; Chitambo, H.; Tada, Y. Detection of Trypanosoma Congolense and T. Brucei Subspecies in Cattle in Zambia by Polymerase Chain Reaction from Blood Collected on a Filter Paper. Parasitology research 1997, 83, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsidzira, L.; Fana, G.T. Pitfalls in the Diagnosis of Trypanosomiasis in Low Endemic Countries: A Case Report. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2010, 4, e823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shereni, W.; Neves, L.; Argilés, R.; Nyakupinda, L.; Cecchi, G. An Atlas of Tsetse and Animal African Trypanosomiasis in Zimbabwe. Parasites & vectors 2021, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Steverding, D. The History of Leishmaniasis. Parasit Vectors 2017, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Griensven, J.; Diro, E. Visceral Leishmaniasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2012, 26, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reithinger, R.; Dujardin, J.-C.; Louzir, H.; Pirmez, C.; Alexander, B.; Brooker, S. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis 2007, 7, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, C.V.; Craft, N. Cutaneous and Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis. Dermatologic Therapy 2009, 22, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijlstra, E.E.; Musa, A.M.; Khalil, E.A.G.; el-Hassan, I.M.; el-Hassan, A.M. Post-Kala-Azar Dermal Leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis 2003, 3, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adel, A.; Boughoufalah, A.; Saegerman, C.; De Deken, R.; Bouchene, Z.; Soukehal, A.; Berkvens, D.; Boelaert, M. Epidemiology of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Algeria: An Update. PLoS One 2014, 9, e99207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Status of Endemicity of Visceral Leishmaniasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/status-of-endemicity-of-visceral-leishmaniasis (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Pratlong, F.; Debord, T.; Garnotel, E.; Garrabe, E.; Marty, P.; Raphenon, G.; Dedet, J. First Identification of the Causative Agent of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Djibouti: Leishmania Donovani. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology 2005, 99, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, M.; Puente, S.; Gutierrez-Solar, B.; Martinez, P.; Alvar, J. Visceral Leishmaniasis in Angola Due to Leishmania (Leishmania) Infantum. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 1994, 50, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, L.; Sirol, J.; Le Vourch, C.; Labegorre, J.; Cochevelou, D. Sudanese Kala-Azar in West Africa (Author’s Transl). Medecine Tropicale: Revue Du Corps de Sante Colonial 1978, 38, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cagnard, V.; Lindrec, A. A Case of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Bangui, Central African Republic. Medecine Tropicale: Revue du Corps de Sante Colonial 1969, 29, 531–535. [Google Scholar]

- Eholié, S.; Tanon, A.; Folquet-Amorissani, M.; Doukouré, B.; Adoubryn, K.; Yattara, A.; Bissagnéné, E. Three New Cases of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Côte d’Ivoire. Bulletin de La Societe de Pathologie Exotique (1990) 2008, 101, 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ketema, H.; Weldegebreal, F.; Gemechu, A.; Gobena, T. Seroprevalence of Visceral Leishmaniasis and Its Associated Factors among Asymptomatic Pastoral Community of Dire District, Borena Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10, 917536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tournier, E. Note Sur Un Cas de Kala-Azar Infantile Observé Au Gabon. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 1920, 13, 175–176. [Google Scholar]

- Marlet, M.; Sang, D.; Ritmeijer, K.; Muga, R.; Onsongo, J.; Davidson, R. Emergence or Re-Emergence of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Areas of Somalia, Northeastern Kenya, and South-Eastern Ethiopia in 2000–2001. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2003, 97, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.; Ruiz-Postigo, J.A.; Pita, J.; Lado, M.; Ben-Ismail, R.; Argaw, D.; Alvar, J. Visceral Leishmaniasis Outbreak in South Sudan 2009–2012: Epidemiological Assessment and Impact of a Multisectoral Response. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2014, 8, e2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, N.S.; Osman, H.A.; Muneer, M.S.; Samy, A.M.; Ahmed, A.; Mohammed, A.O.; Siddig, E.E.; Abdel Hamid, M.M.; Ali, M.S.; Omer, R.A.; et al. Identifying Asymptomatic Leishmania Infections in Non-Endemic Villages in Gedaref State, Sudan. BMC Res Notes 2019, 12, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conteh, S.; Desjeux, P. Leishmaniasis in The Gambia. I. A Case of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis and a Case of Visceral Leishmaniasis. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1983, 77, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Campos, E.P.; Amedomé, A.A. Kala-Azar in Togo-West African. Presentation of a Clinic Case. Revista Do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo 1979, 21, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Naik, K.; Hira, P.; Bhagwandeen, S.; Egere, J.; Versey, A. Kala-Azar in Zambia: First Report of Two Cases. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1976, 70, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squarre, D.; Chambaro, H.M.; Hayashida, K.; Moonga, L.C.; Qiu, Y.; Goto, Y.; Oparaocha, E.; Mumba, C.; Muleya, W.; Bwalya, P. Autochthonous Leishmania Infantum in Dogs, Zambia, 2021. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2022, 28, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihoubi, I.; Picot, S.; Hafirassou, N.; de Monbrison, F. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania Tropica in Algeria. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2008, 102, 1157–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, C.; Imbert, P.; Darie, H.; Simon, F.; Gros, P.; Debord, T.; Roue, R. Liposomal Amphotericin B Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Contracted in Djibouti and Resistant to Meglumine Antimoniate. Bulletin de la Societe de Pathologie Exotique (1990) 2003, 96, 209–211. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, S.; Pereira, A.; Vasconcelos, J.; Paixão, J.P.; Quivinja, J.; Afonso, J.D.M.; Cristóvão, J.M.; Campino, L. PO 8505 Leishmaniasis in Angola–an Emerging Disease? 2019.

- Montalvo, A.M.; Fraga, J.; Blanco, O.; González, D.; Monzote, L.; Soong, L.; Capó, V. Imported Leishmaniasis Cases in Cuba (2006–2016): What Have We Learned. Tropical Diseases, Travel Medicine and Vaccines 2018, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zida, A.; Sawadogo, P.; Guiguemdé, K.; Soulama, I.; Chanolle, T.; Traoré, S.; Sangaré, I.; Bamba, S. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Burkina Faso: Epidemiological Evolution of a Vector-Borne Disease Locally Called “Ouaga 2000 Disease”: A Minireview. Nigerian Journal of Parasitology 2023, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngouateu, O.B.; Kollo, P.; Ravel, C.; Dereure, J.; Kamtchouing, P.; Same-Ekobo, A.; von Stebut, E.; Maurer, M.; Dondji, B. Clinical Features and Epidemiology of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis and Leishmania Major/HIV Co-Infection in Cameroon: Results of a Large Cross-Sectional Study. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2012, 106, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassa-Kelembho, E.; Kobangue, L.; Huerre, M.; Morvan, J. First Cases of Imported Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Bangui Central African Republic: Efficacy of Metronidazole. Medecine Tropicale: Revue du Corps de Sante Colonial 2003, 63, 597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Nmci, M.-D.; Lg, F.; Mg, P.; Dk, D.; Ym, B.; Ki, O.; D, K.; E, Z.; L, K. Epidemiological, Clinical and Treatment Profile of Leishmaniasisin Birao, Central African Republic. CDOAJ 2025, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demba Kodindo, I.; Baïndaou, G.; Tchonfinet, M.; Ngamada, F.; Ndjékoundadé, A.; Moussa Djibrine, M.; Mahmout Nahor, N.; Kérah Hinzoumbé, C.; Saada, D.; Seydou, D. Retrospective Study of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in the District Hospital of Am Timan, Chad. Bulletin de la Société de pathologie exotique 2015, 108, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molecular-Diagnosis-of-the-First-Cases-of--Emleishmania-Tropicaem-Cutaneous--Leishmaniasis-in-Elementary-School--Pupils-.Pdf.

- Diabaté, A.; Fukaura, R.; Terashima-Murase, C.; Vagamon, B.; Yotsu, R.R. Case Report: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis-A Hidden Disease in Côte d’Ivoire. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2024, 111, 950–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpia Elenge, D. From Burden of the Disease to the Access to Care for Treatment: Case of Leishmaniasis in the Democratic Republic of Congo; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Samy, A.M.; Doha, S.A.; Kenawy, M.A. Ecology of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Sinai: Linking Parasites, Vectors and Hosts. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2014, 109, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanger, P.; Kötter, I.; Raible, A.; Gelanew, T.; Schönian, G.; Kremsner, P.G. Case Report: Successful Treatment of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania Aethiopica with Liposomal Amphothericin B in an Immunocompromised Traveler Returning from Eritrea. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2011, 84, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Henten, S.; Adriaensen, W.; Fikre, H.; Akuffo, H.; Diro, E.; Hailu, A.; Van der Auwera, G.; van Griensven, J. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Due to Leishmania Aethiopica. EClinicalMedicine 2018, 6, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akuffo, R.; Sanchez, C.; Chicharro, C.; Carrillo, E.; Attram, N.; Mosore, M.-T.; Yeboah, C.; Kotey, N.K.; Boakye, D.; Ruiz-Postigo, J.-A. Detection of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Three Communities of Oti Region, Ghana. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021, 15, e0009416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, D.; Wilson, M.; Kweku, M. A Review of Leishmaniasis in West Africa. Ghana Medical Journal 2005, 39, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbatani, S.; Calzado, A.I.; Feero, A.; Goudlaby, A.L.; Borghl, V.; Zanchetta, C.; Varnler, O. Atypical Leishmaniasis in an HIV-2-Seropositive Patient from Guinea-Bissau. Aids 1991, 5, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngere, I.; Gufu Boru, W.; Isack, A.; Muiruri, J.; Obonyo, M.; Matendechero, S.; Gura, Z. Burden and Risk Factors of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in a Peri-Urban Settlement in Kenya, 2016. PloS one 2020, 15, e0227697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amro, A.; Gashout, A.; Al-Dwibe, H.; Zahangir Alam, M.; Annajar, B.; Hamarsheh, O.; Shubar, H.; Schönian, G. First Molecular Epidemiological Study of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Libya. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2012, 6, e1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pharoah, P.; Ponnighaus, J.; Chavula, D.; Lucas, S. Two Cases of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Malawi. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1993, 87, 668–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, C.; Doumbia, S.; Keita, S.; Sethi, A. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Mali. Dermatologic clinics 2011, 29, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Status of Endemicity of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/status-of-endemicity-of-cutaneous-leishmaniasis (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Kahime, K.; Boussaa, S.; Laamrani-El Idrissi, A.; Nhammi, H.; Boumezzough, A. Epidemiological Study on Acute Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Morocco. Journal of Acute Disease 2016, 5, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madede, B.; Maphosa, T.; Greyling, K.; Engelbrecht, J.; Kairinos, N. An Unexpected Encounter: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Wound Care. Wound Healing Southern Africa 2024, 17, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Develoux, M.; Blanc, L.; Garba, S.; Mamoudou, H.D.; Warter, A.; Ravisse, P. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Niger. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 1990, 43, 29–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukar, A.; Denue, B.A.; Gadzama, G.B.; Ngadda, H.A. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Literature Review and Report of Two Cases from Communities Devastated by Insurgency in North-East Nigeria. Global J Med Public Health 2015, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Diadie, S.; Diatta, B.; Ndiaye, M.; Seck, N.; Diallo, S.; Niang, S.; Dieng, M. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Senegal: A Series of 38 Cases at the Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital in Dakar. Medecine Et Sante Tropicales 2018, 28, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.; Gordon, W.; Emms, M. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Southern Africa. 1979.

- Grove, S. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in South West Africa. South African Medical Journal 1970, 44, 206–207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elamin, E.; Guizani, I.; Guerbouj, S.; Gramiccia, M.; El Hassan, A.; Di Muccio, T.; Taha, M.; Mukhtar, M. Identification of Leishmania Donovani as a Cause of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Sudan. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2008, 102, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashford, R.W. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: Strategies for Prevention. Clinics in Dermatology 1999, 17, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousslimi, N.; Aoun, K.; Ben-Abda, I.; Ben-Alaya-Bouafif, N.; Raouane, M.; Bouratbine, A. Epidemiologic and Clinical Features of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Southeastern Tunisia. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2010, 83, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentongo, E.; Ddumba, E.; Amandua, J.; Owor, R. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Uganda: Report of the First Case at Mulago National Referral and Teaching Hospital. 2012.

- Alvar, J.; Cañavate, C.; Molina, R.; Moreno, J.; Nieto, J. Canine Leishmaniasis. Adv Parasitol 2004, 57, 1–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touhami, N.A.K.; Ouchene, N.; Ouchetati, I.; Naghib, I. Animal Leishmaniasis in Algeria: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2023, 93, 101930. [Google Scholar]

- Vilhena, H.; Granada, S.; Oliveira, A.C.; Schallig, H.D.; Nachum-Biala, Y.; Cardoso, L.; Baneth, G. Serological and Molecular Survey of Leishmania Infection in Dogs from Luanda, Angola. Parasites & vectors 2014, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sangare, I.; Dabiré, R.; Guiguemdé, R.; Fournet, F.; Price, H.; Djibougou, A.; Yaméogo, B.; Drabo, F.; Diabaté, A.; Banuls, A. First Detection of Leishmania Infantum in Domestic Dogs from Burkina Faso (West Africa). Research Journal of Parasitology 2016, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, I.; Forestier, C.-L.; Peeters, M.; Delaporte, E.; Raoult, D.; Bittar, F. Wild Gorillas as a Potential Reservoir of Leishmania Major. The Journal of infectious diseases 2015, 211, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, R. African Leishmaniasis. Central African Journal of Medicine 1956, 2, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Medkour, H.; Laidoudi, Y.; Athias, E.; Bouam, A.; Dizoé, S.; Davoust, B.; Mediannikov, O. Molecular and Serological Detection of Animal and Human Vector-Borne Pathogens in the Blood of Dogs from Côte d’Ivoire. Comparative immunology, microbiology and infectious diseases 2020, 69, 101412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selim, A.; Shoulah, S.; Abdelhady, A.; Alouffi, A.; Alraey, Y.; Al-Salem, W.S. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Canine Leishmaniasis in Egypt. Veterinary Sciences 2021, 8, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremedhin, E.Z.; Sarba, E.J.; Tola, G.K.; Endalew, S.S.; Marami, L.M.; Melkamsew, A.T.; Presti, V.D.M.L.; Vitale, M. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Toxoplasma Gondii and Leishmania Spp. Infections in Apparently Healthy Dogs in West Shewa Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. BMC Veterinary Research 2021, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saf’ianova, V.; Goncharov, D.; Emel’ianova, L. The Serological Examination of the Population for Leishmaniasis and the Detection of Leishmania in Rodents in the Republic of Guinea. Meditsinskaia Parazitologiia i Parazitarnye Bolezni 1992, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.O.; Mutinga, J.M.; Rodgers, M.R. Leishmaniasis in a Domestic Goat in Kenya. Molecular and cellular probes 5, 319–325. [CrossRef]

- Postigo, J.A.R. Leishmaniasis in the World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Region. International journal of antimicrobial agents 36 Suppl 1, S62–S65. [CrossRef]

- Buck, G.; Courdurier, J.; Dorel, R.; Quesnel, J. First Case of Canine Leishmaniasis in Madagascar. 1951.

- Johansson, S. General Health Conditions in the Dog Population of Lilongwe. 2016.

- Echchakery, M.; Chicharro, C.; Boussaa, S.; Nieto, J.; Carrillo, E.; Sheila, O.; Moreno, J.; Boumezzough, A. Molecular Detection of Leishmania Infantum and Leishmania Tropica in Rodent Species from Endemic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Areas in Morocco. Parasites & vectors 2017, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mouhdi, K.; Boussaa, S.; Chahlaoui, A.; Fekhaoui, M. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Canine Leishmaniasis in Morocco: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Parasitic Diseases 2022, 46, 967–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; UNEP United Nations Environment Programme; World Organisation for Animal Health. One Health Joint Plan of Action (2022‒2026): Working Together for the Health of Humans, Animals, Plants and the Environment; World Health Organization, 2022; ISBN 92-4-005913-X. [Google Scholar]

- Adediran, O.A.; Kolapo, T.U.; Uwalaka, E.C. Seroprevalence of Canine Leishmaniasis in Kwara, Oyo and Ogun States of Nigeria. Journal of Parasitic Diseases 2016, 40, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, B.; Banuls, A.-L.; Bucheton, B.; Dione, M.; Bassanganam, O.; Hide, M.; Dereure, J.; Choisy, M.; Ndiaye, J.; Konate, O. Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania Infantum in Senegal: Risk of Emergence in Humans? Microbes and Infection 2010, 12, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Lugt, J. , Carlyon, JF** &. De Waal, DT*** Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in a Sheep. Journal of the South African Veterinary Association 1992, 63, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sixl, W.; Sebek, Z.; Reinthaler, F.; Mascher, F. Investigations of Wild Animals as Leishmania Reservoir in South Sudan. Journal of Hygiene, Epidemiology, Microbiology, and Immunology 1987, 31, 483–485. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dereure, J.; El-Safi, S.H.; Bucheton, B.; Boni, M.; Kheir, M.M.; Davoust, B.; Pratlong, F.; Feugier, E.; Lambert, M.; Dessein, A. Visceral Leishmaniasis in Eastern Sudan: Parasite Identification in Humans and Dogs; Host-Parasite Relationships. Microbes and infection 2003, 5, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjeux, P.; Bryan, J.H.; Martin-Saxton, P. Leishmaniasis in The Gambia. 2. A Study of Possible Vectors and Animal Reservoirs, with the First Report of a Case of Canine Leishmaniasis in The Gambia. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1983, 77, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chargui, N.; Haouas, N.; Gorcii, M.; Messaidi, F.A.; Zribi, M.; Babba, H. Increase of Canine Leishmaniasis in a Previously Low-Endemicity Area in Tunisia. Parasite 2007, 14, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, U. A Probable Case of Equine Leishmaniasis. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1926, 19, 411–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwangamoi, O.; Busayi, R.; Courtney, S. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in a Calf in Zimbabwe. 1995.

- Dubey, J.; Bwangamoi, O.; Courtney, S.; Fritz, D. Leishmania-like Protozoan Associated with Dermatitis in Cattle. The Journal of parasitology 1998, 865–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Fang, C.; Liu, C.; Yin, M.; Xu, W.; Li, Y.; Yan, X.; Shen, Y.; Cao, J.; Sun, J. Why Is Babesia Not Killed by Artemisinin like Plasmodium? Parasites & Vectors 2023, 16, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Zintl, A.; Mulcahy, G.; Skerrett, H.E.; Taylor, S.M.; Gray, J.S. Babesia Divergens, a Bovine Blood Parasite of Veterinary and Zoonotic Importance. Clinical microbiology reviews 2003, 16, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.D.; Sajid, M.S.; Pascoe, E.L.; Foley, J.E. Detection of Babesia Odocoilei in Humans with Babesiosis Symptoms. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Lonardi, S.; Liang, Q.; Vydyam, P.; Khabirova, E.; Fang, T.; Gihaz, S.; Thekkiniath, J.; Munshi, M.; Abel, S. Babesia Duncani Multi-Omics Identifies Virulence Factors and Drug Targets. Nature microbiology 2023, 8, 845–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Vydyam, P.; Fang, T.; Estrada, K.; Gonzalez, L.M.; Grande, R.; Kumar, M.; Chakravarty, S.; Berry, V.; Ranwez, V. Insights into the Evolution, Virulence and Speciation of Babesia MO1 and Babesia Divergens through Multiomics Analyses. Emerging microbes & infections 2024, 13, 2386136. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, W.C.; Norimine, J.; Knowles, D.P.; Goff, W.L. Immune Control of Babesia Bovis Infection. Veterinary parasitology 2006, 138, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, C.; Buening, G.; Green, T.; Carson, C. In Vitro Cultivation of Babesia Bigemina. American journal of veterinary research 1985, 46, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, A.; Guitian, F.; Pallas, E.; Gestal, J.; Olmeda, A.; Habela, M.; Telford Iii, S.; Spielman, A. Theileria (Babesia) Equi and Babesia Caballi Infections in Horses in Galicia, Spain. Tropical Animal Health and Production 2005, 37, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farwell, G.; LeGrand, E.; Cobb, C. Clinical Observations on Babesia Gibsoni and Babesia Canis Infections in Dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 1982, 180, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.-H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Song, B.G.; Roh, J.Y.; Cho, C.R.; Kim, C.-N.; Um, T.-H.; Kwak, Y.G.; Cho, S.-H.; Lee, S.-E. Detection and Characterization of an Emerging Type of Babesia Sp. Similar to Babesia Motasi for the First Case of Human Babesiosis and Ticks in Korea. Emerging microbes & infections 2019, 8, 869–878. [Google Scholar]

- Yabsley, M.J.; Work, T.M.; Rameyer, R.A. Molecular Phylogeny of Babesia Poelea from Brown Boobies (Sula Leucogaster) from Johnston Atoll, Central Pacific. Journal of Parasitology 2006, 92, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabsley, M.J.; Vanstreels, R.E.; Shock, B.C.; Purdee, M.; Horne, E.C.; Peirce, M.A.; Parsons, N.J. Molecular Characterization of Babesia Peircei and Babesia Ugwidiensis Provides Insight into the Evolution and Host Specificity of Avian Piroplasmids. International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife 2017, 6, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabsley, M.J.; Greiner, E.; Tseng, F.S.; Garner, M.M.; Nordhausen, R.W.; Ziccardi, M.H.; Borjesson, D.L.; Zabolotzky, S. Description of Novel Babesia Species and Associated Lesions from Common Murres (Uria Aalge) from California. Journal of Parasitology 2009, 95, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedhoff, K.T. Transmission of Babesia. In Babesiosis of domestic animals and man; CRC Press, 2018; pp. 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, K.L.; Rice, N.A. Human Coinfection with Borrelia Burgdorferi and Babesia Microti in the United States. Journal of parasitology research 2015, 2015, 587131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, J.M.; Telford, S.R.; Robbins, G.K. Treatment of Refractory Babesia Microti Infection with Atovaquone-Proguanil in an HIV-Infected Patient: Case Report. Clinical infectious diseases 2007, 45, 1588–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, P.J. Babesiosis Diagnosis and Treatment. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 2003, 3, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.P.; Hunfeld, K.-P.; Krause, P.J. Management Strategies for Human Babesiosis. Expert review of anti-infective therapy 2020, 18, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiouani, A.; Azzag, N.; Tennah, S.; Ghalmi, F. Infection with Babesia Canis in Dogs in the Algiers Region: Parasitological and Serological Study. Veterinary World 2020, 13, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomar, A.M.; Molina, I.; Bocanegra, C.; Portillo, A.; Salvador, F.; Moreno, M.; Oteo, J.A. Old Zoonotic Agents and Novel Variants of Tick-Borne Microorganisms from Benguela (Angola), July 2017. Parasites & Vectors 2022, 15, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Nyabongo, L.; Kanduma, E.G.; Bishop, R.P.; Machuka, E.; Njeri, A.; Bimenyimana, A.V.; Nkundwanayo, C.; Odongo, D.O.; Pelle, R. Prevalence of Tick-Transmitted Pathogens in Cattle Reveals That Theileria Parva, Babesia Bigemina and Anaplasma Marginale Are Endemic in Burundi. Parasites & Vectors 2021, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Adehan, S.B.; Biguezoton, A.; Dossoumou, A.; Assogba, M.N.; Adehan, R.; Adakal, H.; Mensah, G.A.; Madder, M. Blood Survey of Babesia Spp and Theileria Spp in Monos Cattle, Benin. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2016, 11, 1266–1272. [Google Scholar]

- McDermid, K.R.; Snyman, A.; Verreynne, F.J.; Carroll, J.P.; Penzhorn, B.L.; Yabsley, M.J. Surveillance for Viral and Parasitic Pathogens in a Vulnerable African Lion (Panthera Leo) Population in the Northern Tuli Game Reserve, Botswana. Journal of wildlife diseases 2017, 53, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringo, A.E.; Moumouni, P.F.A.; Thekisoe, O.; Suzuki, H.; Xuan, X. Molecular Detection of Selected Tick-Borne Hemo-Parasites in Small Ruminants from Seno and Oudalan Provinces, Burkina Faso. The Journal of Protozoology Research 2023, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Checa, R.; Peteiro, L.; Pérez-Hernando, B.; de la Morena, M.; Cano, L.; López-Suárez, P.; Barrera, J.P.; Estévez-Sánchez, E.; Sarquis, J.; Fernández-Cebrián, B. High Serological and Molecular Prevalence of Ehrlichia Canis and Other Vector-Borne Pathogens in Dogs from Boa Vista Island, Cape Verde. Parasites & Vectors 2024, 17, 374. [Google Scholar]

- Mbitkebeyo, R.C.P.; Manchang, K.T.; Raï, C.; Tasse, G.C. Prevalence and Distribution of Tick-Borne Hemoparasites in Cattle from the Noun and Ndé Divisions of the West Region, Cameroon. Open Journal of Veterinary Medicine 2024, 14, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, E.; Garrett, K.B.; Grunert, R.K.; Bryan, J.A.; Sidouin, M.; Oaukou, P.T.; Ngandolo, B.N.R.; Yabsley, M.J.; Cleveland, C.A. Surveillance of Tick-Borne Pathogens in Domestic Dogs from Chad, Africa. BMC Veterinary Research 2024, 20, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, F.; Moutroifi, Y.; Peba, B.; Ali, M.; Moindjie, Y.; Ruget, A.-S.; Abdouroihamane, S.; Kassim, A.M.; Soulé, M.; Charafouddine, O. Tick-Borne Diseases in the Union of the Comoros Are a Hindrance to Livestock Development: Circulation and Associated Risk Factors. Ticks and tick-borne diseases 2020, 11, 101283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, R.; Kouassi, P.; Achi, Y.L.; Dosso, M.; Kgomotso, P. Detection and Distribution of Anaplasma Marginale, Babesia Bovis, and Theileria Annulata in Côte d’Ivoire. Journal of Parasitology and Vector Biology 2023, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ilunga, A.K.; Inkale, C.B.; Kilara, T.; Woto, I.; Kabengele, G.K.; Bongenya, B.I.; Buassa, B.B.; Nyembue, D.T.; Kabengele, B.O.; Kamangu, E.N. Blood Safety in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Literature Review. Open Journal of Blood Diseases 2023, 13, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menshawy, S.M. A Review on Bovine Babesiosis in Egypt. Egyptian Veterinary Medical Society of Parasitology Journal (EVMSPJ) 2020, 16, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, E.P. Misdiagnosis of Babesiosis as Malaria, Equatorial Guinea, 2014. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, G. Bovine Anaplasmosis in Eritrea. 1936.

- Ledger, K.J.; Beati, L.; Wisely, S.M. Survey of Ticks and Tick-Borne Rickettsial and Protozoan Pathogens in Eswatini. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesseha, H.; Mathewos, M.; Eshetu, E.; Tefera, B. Babesiosis in Cattle and Ixodid Tick Distribution in Dasenech and Salamago Districts, Southern Ethiopia. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenguele, M.; Meye, B.; Ndong, T.; Mickala, P. Prevalence of Haemoparasites among Blood Donors Attending the Regional Hospital Center of Franceville (Southern Gabon). J Infect Dis Epidemiol 2022, 8, 270. [Google Scholar]

- Makouloutou-Nzassi, P.; Nze-Nkogue, C.; Makanga, B.K.; Longo-Pendy, N.M.; Bourobou, J.A.B.; Nso, B.C.B.B.; Akomo-Okoue, E.F.; Mbazoghe-Engo, C.-C.; Bangueboussa, F.; Sevidzem, S.L. Occurrence of Multiple Infections of Rodents with Parasites and Bacteria in the Sibang Arboretum, Libreville, Gabon. Veterinary World 2024, 17, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimako-Boateng, M.; Boakye, O.; Bediako, O.; Asare, D.; Emikpe, B. Prevalence of Haemoparasites and Effects on Blood Parameters of Horses in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. Nigerian Journal of Parasitology 2022, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassone, L.; Pagani, P.; De Meneghi, D. Detection of Babesia Caballi in Amblyomma Variegatum Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) Collected from Cattle in the Republic of Guinea. Parassitologia 2005, 47, 247. [Google Scholar]

- Githaka, N.W.; Bishop, R.P.; Šlapeta, J.; Emery, D.; Nguu, E.K.; Kanduma, E.G. Molecular Survey of Babesia Parasites in Kenya: First Detailed Report on Occurrence of Babesia Bovis in Cattle. Parasites & Vectors 2022, 15, 161. [Google Scholar]

- Mahlobo, S.I.; Zishiri, O.T. A Descriptive Study of Parasites Detected in Ticks of Domestic Animals in Lesotho. Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports 2021, 25, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EZELDIN, N. Incidence of Theileriosis, Babesiosis and Anaplasmosis in Cattle in Tripoli-Libya. Veterinary Medical Journal (Giza) 2008, 56, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ranaivoson, H.C.; Héraud, J.-M.; Goethert, H.K.; Telford, S.R.; Rabetafika, L.; Brook, C.E. Babesial Infection in the Madagascan Flying Fox, Pteropus Rufus É. Geoffroy, 1803. Parasites & Vectors 2019, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chatanga, E.; Maganga, E.; Mohamed, W.M.A.; Ogata, S.; Pandey, G.S.; Abdelbaset, A.E.; Hayashida, K.; Sugimoto, C.; Katakura, K.; Nonaka, N. High Infection Rate of Tick-Borne Protozoan and Rickettsial Pathogens of Cattle in Malawi and the Development of a Multiplex PCR for Babesia and Theileria Species Identification. Acta tropica 2022, 231, 106413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakite, M.; SACKO, B.; Sidibe, F.; Bengaly, S.; Sidibe, S. Study of the Prevalence of Bovine Babesiosis with Babesia Bovis and Babesia Bigemina Isolated in the Livestock of Bamako and Its Peri-Urban Area between 2018 and 2023. 2024.

- Lee, G.K.C.; Ignace, J.A.E.; Robertson, I.D.; Irwin, P.J. Canine Vector-Borne Infections in Mauritius. Parasites & vectors 2015, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rhalem, A.; Sahibi, H.; Lasri, S.; Johnson, W.C.; Kappmeyer, L.S.; Hamidouch, A.; Knowles, D.P.; Goff, W.L. Validation of a Competitive Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for Diagnosing Babesia Equi Infections of Moroccan Origin and Its Use in Determining the Seroprevalence of B. Equi in Morocco. Journal of veterinary diagnostic investigation 2001, 13, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, T.M.; Pedro, O.C.; Caldeira, R.A.; do Rosário, V.E.; Neves, L.; Domingos, A. Detection of Bovine Babesiosis in Mozambique by a Novel Seminested Hot-Start PCR Method. Veterinary Parasitology 2008, 153, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheus, E.K.; Oosthuizen, J.; Mbajiorgu, C.A.; Oguttu, J.W. Prevalence of Babesiosis in Sanga Cattle in the Ohangwena Region of Namibia. Indian Journal of Animal Research 2019, 53, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogo, N.; Lawal, A.; Okubanjo, O.; Kamani, J.; Ajayi, O. Current Status of Canine Babesiosis and the Situation in Nigeria: A Review. Nigerian Veterinary Journal 2011, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Bazarusanga, T. The Epidemiology of Theileriosis in Rwanda and Implications for Control. 2008.

- Paling, R.; Mpangala, C.; Luttikhuizen, B.; Sibomana, G. Exposure of Ankole and Crossbred Cattle to Theileriosis in Rwanda. Tropical animal health and production 1991, 23, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueye, A.; Mbengue, M.; Diouf, A. Ticks and Hemoparasitic Diseases in Cattle in Senegal. IV. The Southern Sudan Area. Revue d’elevage et de medecine veterinaire des pays tropicaux 1990, 42, 517–528. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, M. Nuttallia França, 1909 (Babesiidae) Preoccupied by Nuttallia Dall, 1898 (Psammobiidae): A Re-Appraisal of the Taxonomic Position of the Avian Piroplasms. International Journal for Parasitology 1975, 5, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.A.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Mohamed, R.H.; Aden, H.H. Preliminary Assessment of Goat Piroplasmosis in Benadir Region, Somalia. 2013.

- Oosthuizen, M.C.; Zweygarth, E.; Collins, N.E.; Troskie, M.; Penzhorn, B.L. Identification of a Novel Babesia Sp. from a Sable Antelope (Hippotragus Niger Harris, 1838). Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2008, 46, 2247–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, R. , * Huchzermeyer, FW,** Bennett, GF* & Brassy, JJ*** Babesia Peircei Sp. Nov. from the Jackass Penguin. African Zoology 1993, 28, 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kivaria, F.M.; Kapaga, A.M.; Mbassa, G.K.; Mtui, P.F.; Wani, R.J. Epidemiological Perspectives of Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases in South Sudan: Cross-Sectional Survey Results. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 2012, 79, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, H.; Antunes, S.; Galindo, R.C.; do Rosário, V.E.; De la Fuente, J.; Domingos, A.; El Hussein, A.M. Prevalence and Genetic Diversity of Babesia and Anaplasma Species in Cattle in Sudan. Veterinary parasitology 2011, 181, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloch, E.M.; Kasubi, M.; Levin, A.; Mrango, Z.; Weaver, J.; Munoz, B.; West, S.K. Babesia Microti and Malaria Infection in Africa: A Pilot Serosurvey in Kilosa District, Tanzania. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2018, 99, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coultous, R.M.; McDonald, M.; Raftery, A.G.; Shiels, B.R.; Sutton, D.G.; Weir, W. Analysis of Theileria Equi Diversity in The Gambia Using a Novel Genotyping Method. Transboundary and emerging diseases 2020, 67, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjeibi, M.R.; Gharbi, M.; Mhadhbi, M.; Mabrouk, W.; Ayari, B.; Nasfi, I.; Jedidi, M.; Sassi, L.; Rekik, M.; Darghouth, M.A. Prevalence of Piroplasms in Small Ruminants in North-West Tunisia and the First Genetic Characterisation of Babesia Ovis in Africa. Parasite 2014, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhanguzi, D.; Matovu, E.; Waiswa, C. Prevalence and Characterization of Theileria and Babesia Species in Cattle under Different Husbandry Systems in Western Uganda. Int. J. Anim. Vet. Adv 2010, 2, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nalubamba, K.S.; Hankanga, C.; Mudenda, N.B.; Masuku, M. The Epidemiology of Canine Babesia Infections in Zambia. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2011, 99, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wray, K.; Musuka, G.; Trees, A.; Jongejan, F.; Smeenk, I.; Kelly, P. Babesia Bovis and B. Bigemina DNA Detected in Cattle and Ticks from Zimbabwe by Polymerase Chain Reaction. Journal of the South African Veterinary Association 2000, 71, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yongabi, K.A.; Chia-Garba, M. Incidence of Babessia Infections Causing Pyrexia of Unknown Origin (PUO) amongst HIV/AIDS Patients in Cameroon.

- Michael, S.; Morsy, T.; Montasser, M. A Case of Human Babesiosis (Preliminary Case Report in Egypt). 1987.

- Rodriguez, O.; Isabel, M.; Dias, R.; Rodriguez, P. Report on Infection with Babesia Bovis (Babes, 1888) in the Human Population of the Popular Republic of Mozambique. Rev. Cub. Cienc. Vet 1984, 15, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.M.; Mohammed, Y.; Jiya, N.M.; Jibrin, B.; Zainu, S.M.; Legbo, J.F.; Abubakar, F.; Jimoh, A.K. Fatal Human Babesiosis in a Nine-Year Old Nigerian Girl. 2020.

- Bush, J.; Isaäcson, M.; Mohamed, A.; Potgieter, F.; Waal, D. de Human Babesiosis-a Preliminary Report of 2 Suspected Cases in Southern Africa. 1990.

- Owusu, I.A. Detection of Zoonotic Babesia Species in Greater Accra, Ghana. 2015.

- Bishop, R.; Musoke, A.; Morzaria, S.; Gardner, M.; Nene, V. Theileria: Intracellular Protozoan Parasites of Wild and Domestic Ruminants Transmitted by Ixodid Ticks. Parasitology 2004, 129, S271–S283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nene, V.; Kiara, H.; Lacasta, A.; Pelle, R.; Svitek, N.; Steinaa, L. The Biology of Theileria Parva and Control of East Coast Fever–Current Status and Future Trends. Ticks and tick-borne diseases 2016, 7, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, N.; Ayaz, S.; Gul, I.; Adnan, M.; Shams, S.; Akbar, N. Tropical Theileriosis and East Coast Fever in Cattle: Present, Past and Future Perspective. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci 2015, 4, 1000–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Surve, A.A.; Hwang, J.Y.; Manian, S.; Onono, J.O.; Yoder, J. Economics of East Coast Fever: A Literature Review. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2023, 10, 1239110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gachohi, J.; Skilton, R.; Hansen, F.; Ngumi, P.; Kitala, P. Epidemiology of East Coast Fever (Theileria Parva Infection) in Kenya: Past, Present and the Future. Parasites & Vectors 2012, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nuttall, P.A. Climate Change Impacts on Ticks and Tick-Borne Infections. Biologia 2022, 77, 1503–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamyingkird, K.; Sayed-Ahmed, M.Z.; Rizk, M.A. Treatment of Tick-Borne Diseases: Current Status, Challenges, and Global Perspectives. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2024, 15, 1366988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeroual, F.; Saidani, K.; Righi, S.; Simion, V.E.; Mellah, A.; Kourtel, S.; Benakhla, A. An Overview on Tropical Theileriosis in Algeria. Romanian Journal of Veterinary Medicine & Pharmacology 2022, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kubelová, M.; Mazancová, J.; Široký, P. Theileria, Babesia, and Anaplasma Detected by PCR in Ruminant Herds at Bié Province, Angola. Parasite 2012, 19, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, A.S.; Zannou, O.M.; Biguezoton, A.S.; Kouassi, P.Y.; Belem, A.; Farougou, S.; Oosthuizen, M.; Saegerman, C.; Lempereur, L. Cattle Ticks and Associated Tick-Borne Pathogens in Burkina Faso and Benin: Apparent Northern Spread of Rhipicephalus Microplus in Benin and First Evidence of Theileria Velifera and Theileria Annulata. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases 2021, 12, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binta, M.; Losho, T.; Allsopp, B.; Mushi, E. Isolation of Theileria Taurotragi and Theileria Mutans from Cattle in Botswana. Veterinary parasitology 1998, 77, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuhaire, D.K.; Muleya, W.; Mbao, V.; Niyongabo, J.; Nyabongo, L.; Nsanganiyumwami, D.; Salt, J.; Namangala, B.; Musoke, A.J. Molecular Characterization and Population Genetics of Theileria Parva in Burundi’s Unvaccinated Cattle: Towards the Introduction of East Coast Fever Vaccine. Plos one 2021, 16, e0251500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silatsa, B.A.; Simo, G.; Githaka, N.; Kamga, R.; Oumarou, F.; Keambou Tiambo, C.; Machuka, E.; Domelevo, J.; Odongo, D.; Bishop, R. First Detection of Theileria Parva in Cattle from Cameroon in the Absence of the Main Tick Vector Rhipicephalus Appendiculatus. Transboundary and emerging diseases 2020, 67, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uilenberg, G. Existence of Haematoxenus Veliferus (Sporozoa, Theileriidae) in Central African Republic [and Chad]. Presence of Haematoxenus Sp. in African Buffalo. 1970.

- De Deken, R.; Martin, V.; Saido, A.; Madder, M.; Brandt, J.; Geysen, D. An Outbreak of East Coast Fever on the Comoros: A Consequence of the Import of Immunised Cattle from Tanzania? Veterinary Parasitology 2007, 143, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amzati, G.S.; Djikeng, A.; Odongo, D.O.; Nimpaye, H.; Sibeko, K.P.; Muhigwa, J.-B.B.; Madder, M.; Kirschvink, N.; Marcotty, T. Genetic and Antigenic Variation of the Bovine Tick-Borne Pathogen Theileria Parva in the Great Lakes Region of Central Africa. Parasites & vectors 2019, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Norval, R.A.I.; Perry, B.D.; Young, A. The Epidemiology of Theileriosis in Africa; ILRI (aka ILCA and ILRAD), 1992; ISBN 0-12-521740-4. [Google Scholar]

- Carpano, M. A Piroplasm of the Parvum Type (Genus Theileria) in a Gazelle in Eritrea. 1913.

- Gebrekidan, H.; Hailu, A.; Kassahun, A.; Rohoušová, I.; Maia, C.; Talmi-Frank, D.; Warburg, A.; Baneth, G. Theileria Infection in Domestic Ruminants in Northern Ethiopia. Veterinary Parasitology 2014, 200, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangombi, J.B.; N’dilimabaka, N.; Lekana-Douki, J.-B.; Banga, O.; Maghendji-Nzondo, S.; Bourgarel, M.; Leroy, E.; Fenollar, F.; Mediannikov, O. First Investigation of Pathogenic Bacteria, Protozoa and Viruses in Rodents and Shrews in Context of Forest-Savannah-Urban Areas Interface in the City of Franceville (Gabon). PloS one 2021, 16, e0248244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo, S.O.; Bentil, R.E.; Baako, B.O.A.; Addae, C.A.; Behene, E.; Asoala, V.; Mate, S.; Oduro, D.; Dunford, J.C.; Larbi, J.A. First Record of Babesia and Theileria Parasites in Ticks from Kassena-Nankana, Ghana. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 2023, 37, 878–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diallo, T.; Singla, L.; Sumbria, D.; Kaur, P.; Bal, M. Conventional and Molecular Diagnosis of Haemo-Protozoan Infections in Cattle and Equids from Republic of Guinea and India. Indian Journal of Animal Research 2018, 52, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, F.; Crespo, M.; Dias, J. Some Ectoparasites and Protozoans in Bovines from the Republic of Guinea Bissau. 1998.

- King’ori, E.; Obanda, V.; Chiyo, P.I.; Soriguer, R.C.; Morrondo, P.; Angelone, S. Molecular Identification of Ehrlichia, Anaplasma, Babesia and Theileria in African Elephants and Their Ticks. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0226083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uilenberg, G. Haematoxenus Veliferus, Hématozoaire Des Bovins à Madagascar: Note Complémentaire. 1965.

- Wymann, M.N. Calf Mortality and Parasitism in Periurban Livestock Production in Mali. 2005.

- d’Oliveira, C.; Van der Weide, M.; Jacquiet, P.; Jongejan, F. Detection of Theileria Annulata by the PCR in Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) Collected from Cattle in Mauritania. Experimental & applied acarology 1997, 21, 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- Spitalska, E.; Riddell, M.; Heyne, H.; Sparagano, O.A. Prevalence of Theileriosis in Red Hartebeest (Alcelaphus Buselaphus Caama) in Namibia. Parasitology Research 2005, 97, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipeolu, O. Prevalence of Theileria Schizonts in the Domestic Ruminants in Nigeria and the Identification and Bionomics of the Vector. Springer, 1981; pp. 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- David, O.-F.S.; Goria, K.P.; Abraham, D.G.A. Haemoparasite Fauna of Domestic Animals in Plateau State, North Central Nigeria. Bayero Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 2018, 11, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malbrant, R. Piroplasmoses in the French Congo. 1938.

- Addah, L. Pathological Constraints to the Improvement of Dairy Production Potential in Tick-Infested Tropical Areas: The Case of Sao Tome and Principe. 1987.

- Gueye, A.; Mbengue, M.; Diouf, A. Présence de Theileria Velifera Au Sénégal. Revue d’élevage et de médecine vétérinaire des pays tropicaux 1987, 40, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabs-Garnon, L.; Foley, V. Caprine Theileriasis in Sierra Leone: First Recorded Cases. 1974.

- Matjila, P.T.; Leisewitz, A.; Oosthuizen, M.; Jongejan, F.; Penzhorn, B. Detection of a Theileria Species in Dogs in South Africa. Veterinary Parasitology 2008, 157, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abaker, I.A.; Salih, D.A.; El Haj, L.M.; Ahmed, R.E.; Osman, M.M.; Ali, A.M. Prevalence of Theileria Annulata in Dairy Cattle in Nyala, South Darfur State, Sudan. Veterinary world 2017, 10, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]