Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is one of the leading causes of mortality. Many factors may influence the risk of mortality in patients with CHF. Therefore, predictors of mortality in patients with CHF should be clarified. Aim of the study was to determine predictors of unfavorable prognosis in patients with CHF. Methods. 591 patients (median age 71.0 (64.0-80.0) years, 339 (57.4%) men) with CHF were enrolled into the “Samara Region Registry of CHF” during 1-month period in 2022 at 60 centers. The follow-up period was 18 months. During follow-up period 198 (33.5%) patients died. Results. Prognostic factors associated with mortality in patients with CHF according to the results of multivariate analysis were age (OR 1.034, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.018-1.051, p<0.001), LVEF < 40% (OR 1.381, 95% CI 1.014-1.880, p=0.040), NYHA IV class (OR 1.932, 95% CI 1.354-2.757), p<0.001), oxygen therapy at outpatients (OR 2.668, 95% CI 1.482-4.802, p=0.001), in-hospital inotropic therapy (OR 1.463, 95% CI 0.972-2.201, p=0.068), ascites (OR 1.543, 95% CI 0.982-2.425, p=0.06), gender (male) (OR 1.354, 95% CI 0.971-1.887, p=0.074). Previous cardiovascular surgery had an inverse relationship with the probability of death (OR 0.481, 95% CI 0.322-0.718, p<0.001). Conclusions. Predictors of mortality in patients with CHF during 18-months follow-up were age, LVEF<40%, NYHA IV class of CHF, oxygen therapy in outpatient, in-hospital inotropic therapy, ascites and male gender. Previous cardiovascular surgery had favourable effect on mortality in these patients.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

References

- Gerber, Y.; Weston, S.A.; Redfield, M.M.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Manemann, S.M.; Jiang, R.; Killian, J.M.; Roger, V.L. A Contemporary Appraisal of the Heart Failure Epidemic in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2000 to 2010. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczurek-Wasilewicz, W.; Gąsior, M.; Skrzypek, M.; Kurkiewicz, K.; Szyguła-Jurkiewicz, B. Predictors of one-year mortality in ambulatory patients with advanced heart failure awaiting heart transplantation. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2021, 132, 16151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahim, A.; Hourqueig, M.; Lund, L.H.; Savarese, G.; Oger, E.; Venkateshvaran, A.; Benson, L.; Daubert, J.; Linde, C.; Donal, E.; et al. Long-term outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Predictors of cardiac and non-cardiac mortality. ESC Hear. Fail. 2023, 10, 1835–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, C.W.; Lyass, A.; Enserro, D.; Larson, M.G.; Ho, J.E.; Kizer, J.R.; Gottdiener, J.S.; Psaty, B.M.; Vasan, R.S. Temporal Trends in the Incidence of and Mortality Associated With Heart Failure With Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC: Hear. Fail. 2018, 6, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chioncel, O.; Lainscak, M.; Seferovic, P.M.; Anker, S.D.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Harjola, V.; Parissis, J.; Laroche, C.; Piepoli, M.F.; Fonseca, C.; et al. Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2017, 19, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergaro, G.; Ghionzoli, N.; Innocenti, L.; Taddei, C.; Giannoni, A.; Valleggi, A.; Borrelli, C.; Senni, M.; Passino, C.; Emdin, M. Noncardiac Versus Cardiac Mortality in Heart Failure With Preserved, Midrange, and Reduced Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2019, 8, e013441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocock, S.J.; Ariti, C.A.; McMurray, J.J.; Maggioni, A.; Køber, L.; Squire, I.B.; Swedberg, K.; Dobson, J.; Poppe, K.K.; Whalley, G.A.; et al. Predicting survival in heart failure: a risk score based on 39 372 patients from 30 studies. Eur. Hear. J. 2012, 34, 1404–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassus, J.P.; Siirilä-Waris, K.; Nieminen, M.S.; Tolonen, J.; Tarvasmäki, T.; Peuhkurinen, K.; Melin, J.; Pulkki, K.; Harjola, V.-P. Long-term survival after hospitalization for acute heart failure — Differences in prognosis of acutely decompensated chronic and new-onset acute heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012, 168, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, C.; Peveri, G.; Cani, D.; Latta, F.; Bonelli, A.; Tomasoni, D.; Sbolli, M.; Ravera, A.; Carubelli, V.; Saccani, N.; et al. In-hospital and long-term mortality for acute heart failure: analysis at the time of admission to the emergency department. ESC Hear. Fail. 2020, 7, 2650–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, R.; Kajimoto, K.; Oka, T.; Sugiura, R.; Okada, H.; Kamishima, K.; Hirata, T.; Sato, N. Association of New York Heart Association functional class IV symptoms at admission and clinical features with outcomes in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure syndromes. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 230, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nader, V.; Matta, A.; Kang, R.; Deney, A.; Azar, R.; Rouzaud-Laborde, C.; Kunduzova, O.; Itier, R.; Fournier, P.; Galinier, M.; et al. Mortality rate after coronary revascularization in heart failure patients with coronary artery disease. ESC Hear. Fail. 2023, 10, 2656–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iaconelli, A.; Pellicori, P.; Dolce, P.; Busti, M.; Ruggio, A.; Aspromonte, N.; D'Amario, D.; Galli, M.; Princi, G.; Caiazzo, E.; et al. Coronary revascularization for heart failure with coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2023, 25, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Rull, J.L.; Bielsa, S.; Conde-Martel, A.; Aramburu-Bodas, O.; Llacer, P.; Quesada, M.A.; Suarez-Pedreira, I.; Manzano, L.; Barquero, M.M.-P.; Porcel, J.M. Pleural effusions in acute decompensated heart failure: Prevalence and prognostic implications. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 52, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davutoglu, V.; Yildirim, C.; Kucukaslan, H.; Yuce, M.; Sari, I.; Tarakcioglu, M.; Akcay, M.; Cakici, M.; Ceylan, N.; Al, B. Prognostic value of pleural effusion, CA-125 and NT-proBNP in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Kardiol Pol. 2010, 68, 771–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gray, A.; Goodacre, S.; Newby, D.E.; Masson, M.; Sampson, F.; Nicholl, J. Noninvasive Ventilation in Acute Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berbenetz, N.; Wang, Y.; Brown, J.; Godfrey, C.; Ahmad, M.; Vital, F.M.; Lambiase, P.; Banerjee, A.; Bakhai, A.; Chong, M. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (CPAP or bilevel NPPV) for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, CD005351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.S.P.; Arnott, C.; Beale, A.L.; Chandramouli, C.; Hilfiker-Kleiner, D.; Kaye, D.M.; Ky, B.; Santema, B.T.; Sliwa, K.; Voors, A.A. Sex differences in heart failure. Eur Heart J 2019, 40, 3859–3868c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khariton, Y.; Nassif, M.E.; Thomas, L.; Fonarow, G.C.; Mi, X.; DeVore, A.D.; Duffy, C.; Sharma, P.P.; Albert, N.M.; Patterson, J.H.; et al. Health Status Disparities by Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status in Outpatients With Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol HF 2018, 6, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, V.L.; Weston, S.A.; Redfield, M.M.; Hellermann-Homan, J.P.; Killian, J.; Yawn, B.P.; Jacobsen, S.J. Trends in Heart Failure Incidence and Survival in a Community-Based Population. JAMA 2004, 292, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicator | n=591 | |

|---|---|---|

| Men, n (%) | 339 (57.4) | |

| Age, years | 71.0 (64.0-80.0) | |

| NYHA class | III, n (%) | 506 (85.6) |

| IV, n (%) | 85 (14.4) | |

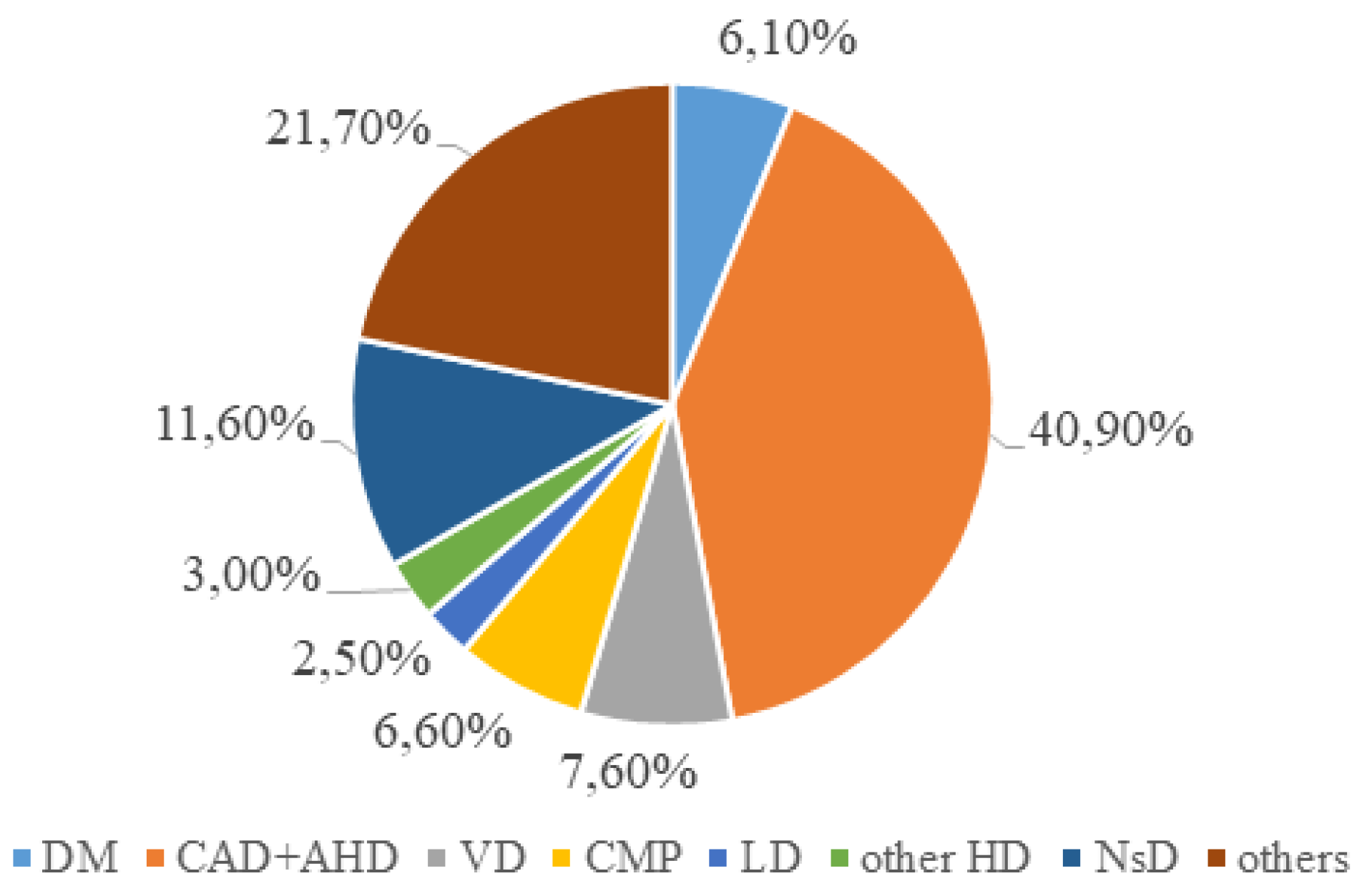

| CAD, including previous MI, n (%) | 381 (64.5) | |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 53 (9,0) | |

| Valvular pathology, n (%) | 19 (3,2) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 9 (1.5) | |

| Others, n (%) | 111 (18.8) | |

| Hospitalization within 1 year, n (%) | 513 (86.8) | |

| LVEF < 40%, n (%) | 229 (37.1) | |

| LBBB, n (%) | 108 (17.5) | |

| VT, n (%) | 55 (8.9) | |

| AF, n (%) | 125 (21.2) | |

| SpO2, % | 97 (96;97) | |

| Cancer, n (%) | 46 (7.4) | |

| Previous heart surgery, n (%) | 160 (25.9) | |

| Indicator | n=591 |

|---|---|

| Pleural effusion, n (%) | 270 (43.7) |

| Ascites, n (%) | 67 (10.8) |

| SBP < 100 mmHg, n (%) | 160 (27.1) |

| Inotropic therapy during hospital stay, n (%) | 84 (13.6) |

| Heart transplant waiting list, n (%) | 12 (1.9) |

| Inotropic therapy on outpatient level, n (%) | 54 (8.7) |

| Oxygen therapy on outpatient level, n (%) | 25 (4,0) |

| Opioid analgesics therapy on outpatient level, n (%) | 5 (0.8) |

| Predialysis or dialysis (CKD stage 4-5, GFR less than 30 ml/min/m2), n (%) | 23 (3.7) |

| Indicators | Group 1 (n=198) |

Group 2 (n=393) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males, n (%) | 110 (55.6%) | 229 (58.3%) | 0.529 | |

| Age, years | 75.0 (66.0;83.0) | 71.0 (64.0;78.0) | 0.001 | |

| NYHA class | III, n (%) | 152 (76.8%) | 354 (90.1%) |

<0.001 |

| IV, n (%) | 46 (23.2%) | 39 (9.9%) | ||

| LVEF <40%, n (%) | 87 (43.9%) | 142 (36.1%) | 0.062 | |

| LBBB, n (%) | 43 (21.7%) | 65 (16.5%) | 0.117 | |

| VT, n (%) | 17 (8.6%) | 38 (9.7%) | 0.669 | |

| SpO2, % | 96.5(96.0;98.0) | 97.0(96.0;98.0) | 0.338 | |

| Implantable devices, n (%) | 19 (9.6%) | 39 (10.1%) | 0.869 | |

| Pleural effusion, n (%) | 108 (54.8%) | 162 (41.3%) | 0.002 | |

| Ascites, n (%) | 28 (14.1%) | 39 (9.9%) | 0.130 | |

| SP < 120 mm Hg | 59 (29.8%) | 101 (25.8%) | 0.298 | |

| Previous cardiovascular surgery, n (%) | 37 (18.8%) | 122 (31.7%) | 0.001 | |

| Inotropic therapy during hospital stay, n (%) | 38 (19.2%) | 46 (11.7%) | 0.014 | |

| Heart transplant waiting list, n (%) |

3 (1.5%) | 9 (2.3%) | 0.759 | |

| Inotropic therapy at outpatient department, n (%) | 24 (12.2%) | 30 (7.7%) | 0.072 | |

| Oxygen therapy at outpatient department, n (%) | 15 (7.6%) | 10 (2.6%) | 0.008 | |

| Opioids at outpatient department, n (%) | 3 (1.5%) | 2 (0.5%) | 0.340 | |

| Predialysis or dialysis (CKD stage 4-5, GFR < 30 ml/min/m2), n (%) | 6 (3.0%) | 17 (4.3%) | 0.506 | |

| Cancer, n (%) | 19 (9.6%) | 27 (6.9%) | 0.250 | |

| Predictors | Multivariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| OR; 95% CI | p-value | |

| Age | 1.034; 1.018-1.051 | <0.001 |

| LVEF < 40% | 1.381; 1.014-1.880 | 0.040 |

| NYHA IV class | 1.932; 1.354-2.757 | <0.001 |

| Inotropic therapy during hospital stay | 1.463; 0.972-2.201 | 0.068 |

| Oxygen therapy | 2.668; 1.482-4.802 | 0.001 |

| Previous cardiovascular surgery | 0.481; 0.322-0.718 | <0.001 |

| Ascites | 1.543; 0.982-2.425 | 0.060 |

| Gender | 1.354; 0.971-1.887 | 0.074 |

| Follow-up periods, months | Basic risk values h0(t) |

|---|---|

| 3 | 0,1% |

| 6 | 0,2% |

| 9 | 0,2% |

| 12 | 0,3% |

| 18 | 0,3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).