Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (i)

- What are the crucial issues in the ongoing debate on the development of electric vehicle concept?

- (ii)

- Where are the major conflicting points and focuses between sustainable economy and electric vehicles?

- (iii)

- How does the mining of metals and minerals follow current zero waste sustain-ability trends?

- (iv)

- How prediction of the magnitude of the future demand for EV batteries guides strategic decision-making in policies throughout the globe?

2. EVs in Today’s Context

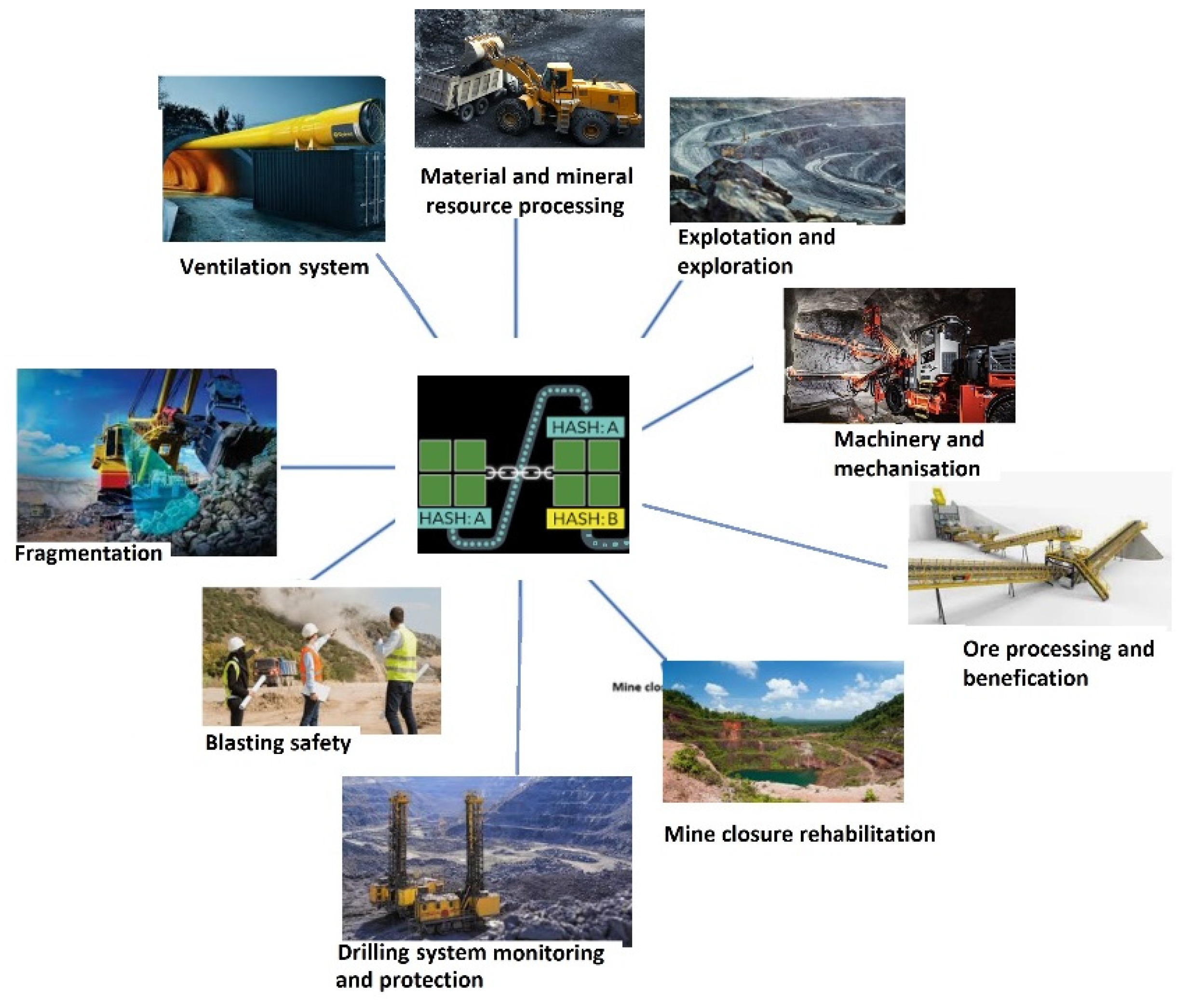

2.1. Towards Industry 4.0 and Beyond

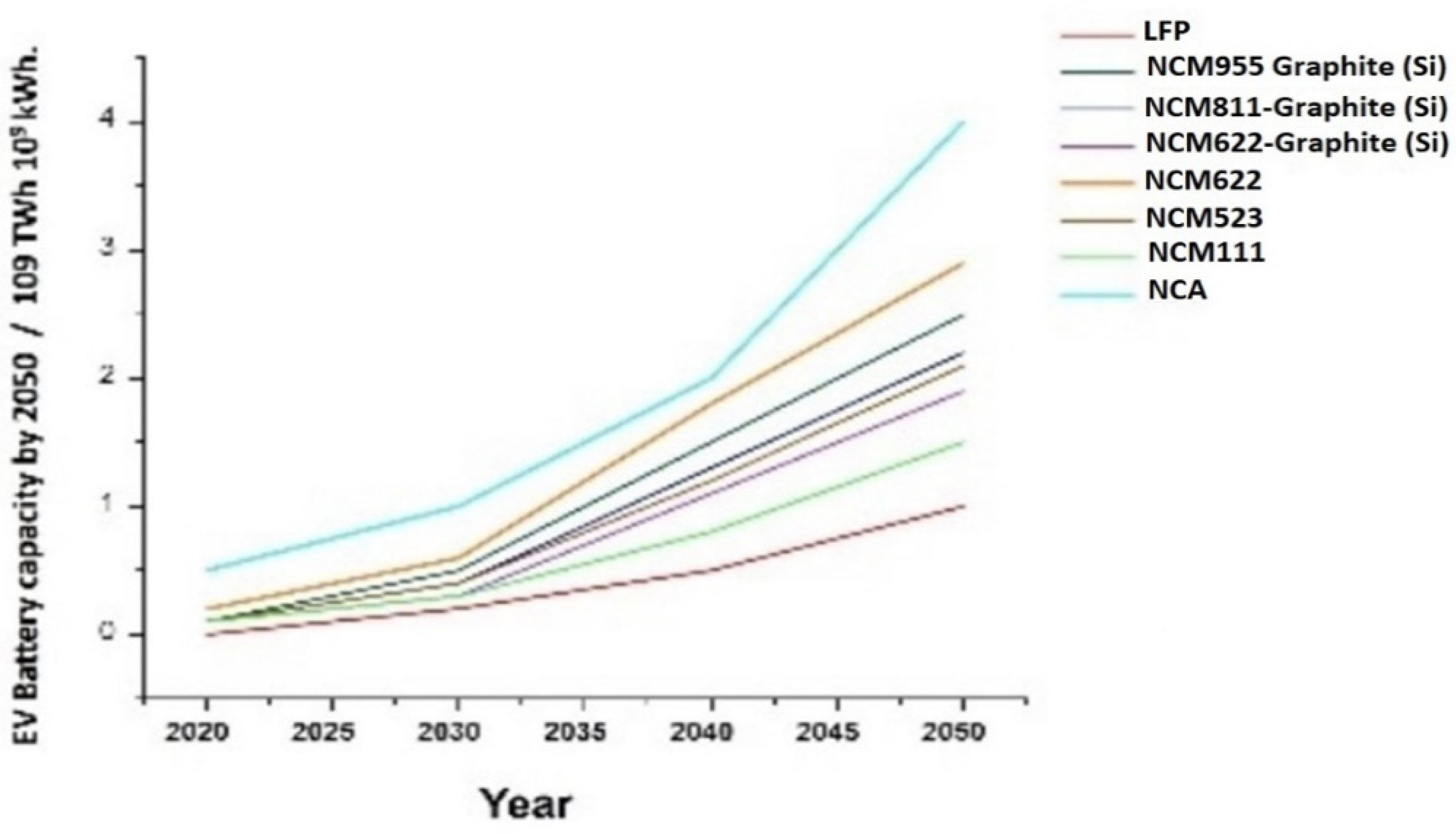

2.2. Quantifying the Future Demand for Battery Materials in the Shift to EV

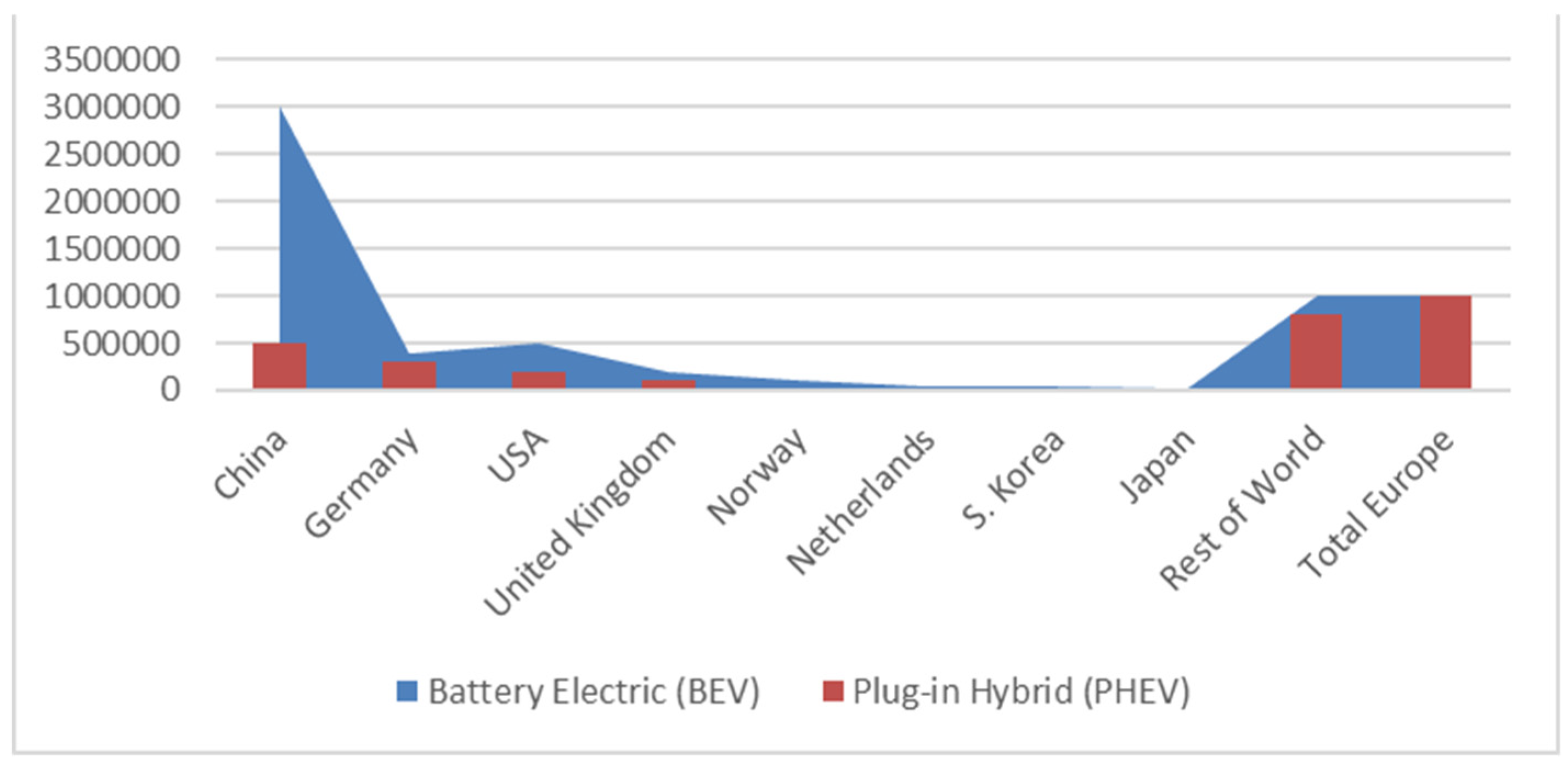

2.3. The Rise of EV: Trends in Electric Light-Duty Vehicles

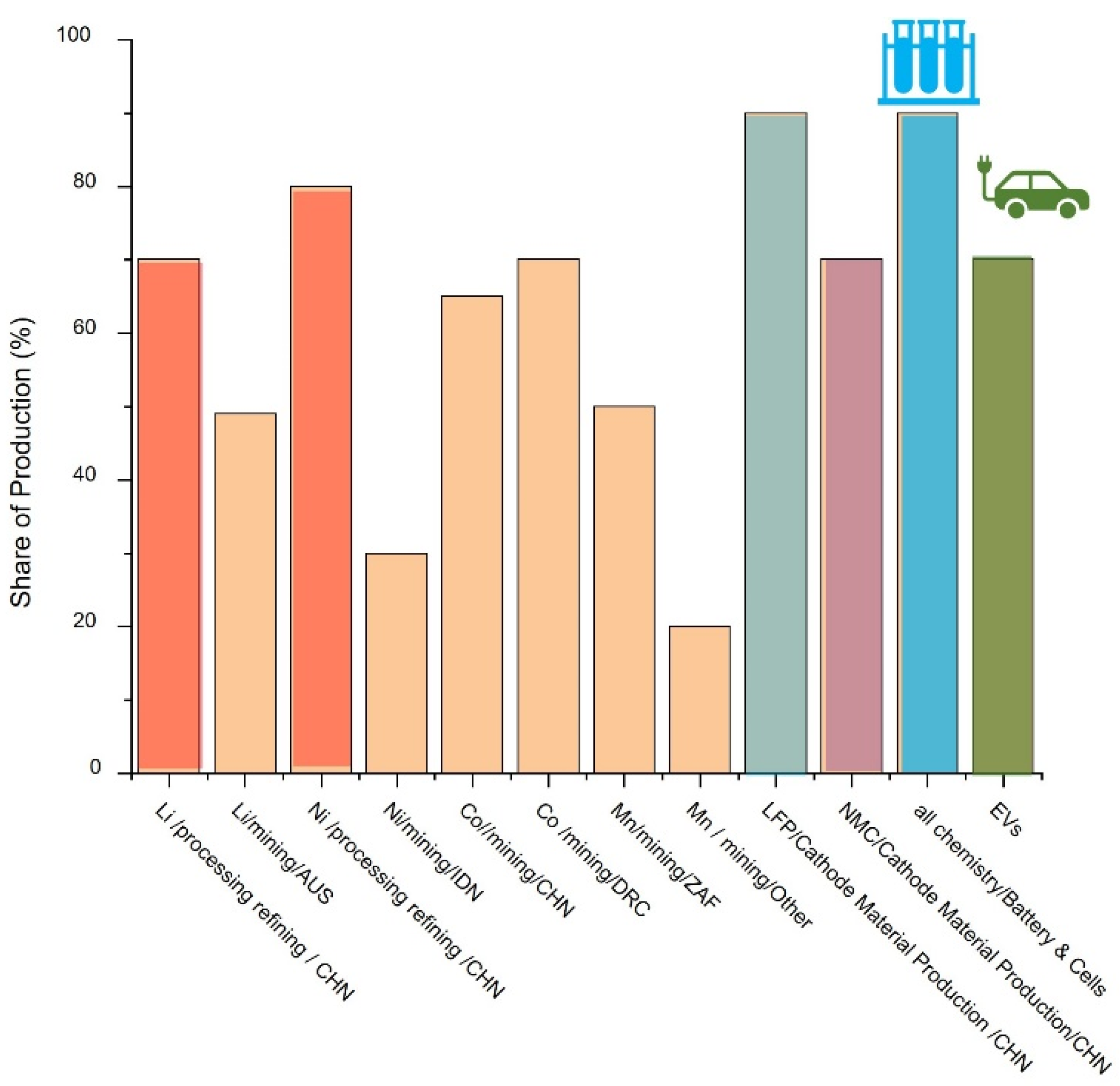

2.4. Trends in Modern Metal Mining Industry for Sustainable Transportation

2.5. Identifying the Regions with Abundant Metal Deposits Critical for EV Production

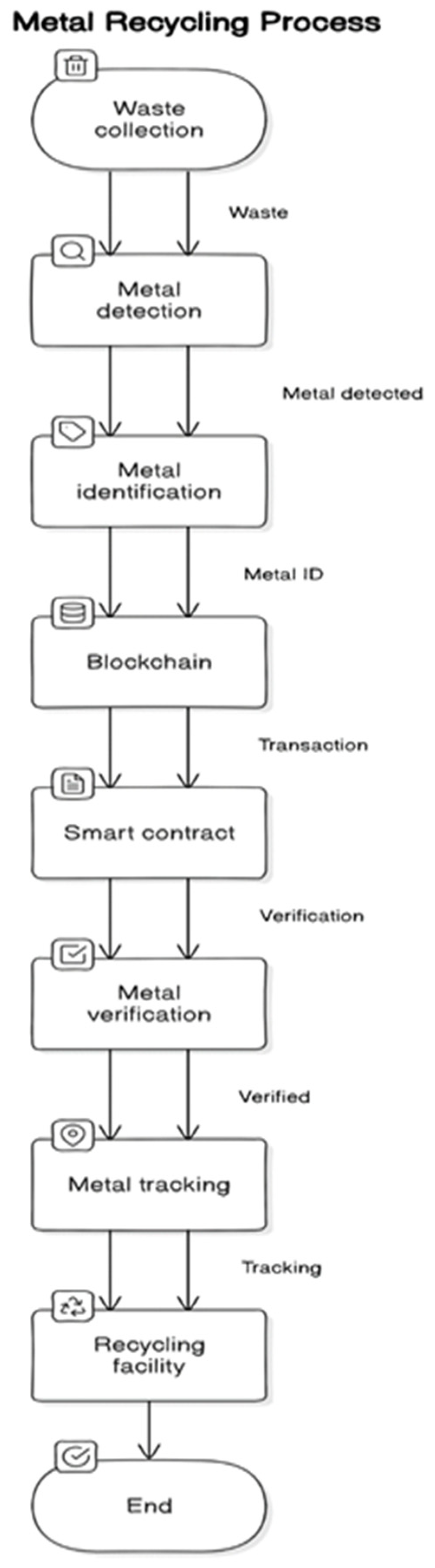

3. Blockchain Technology

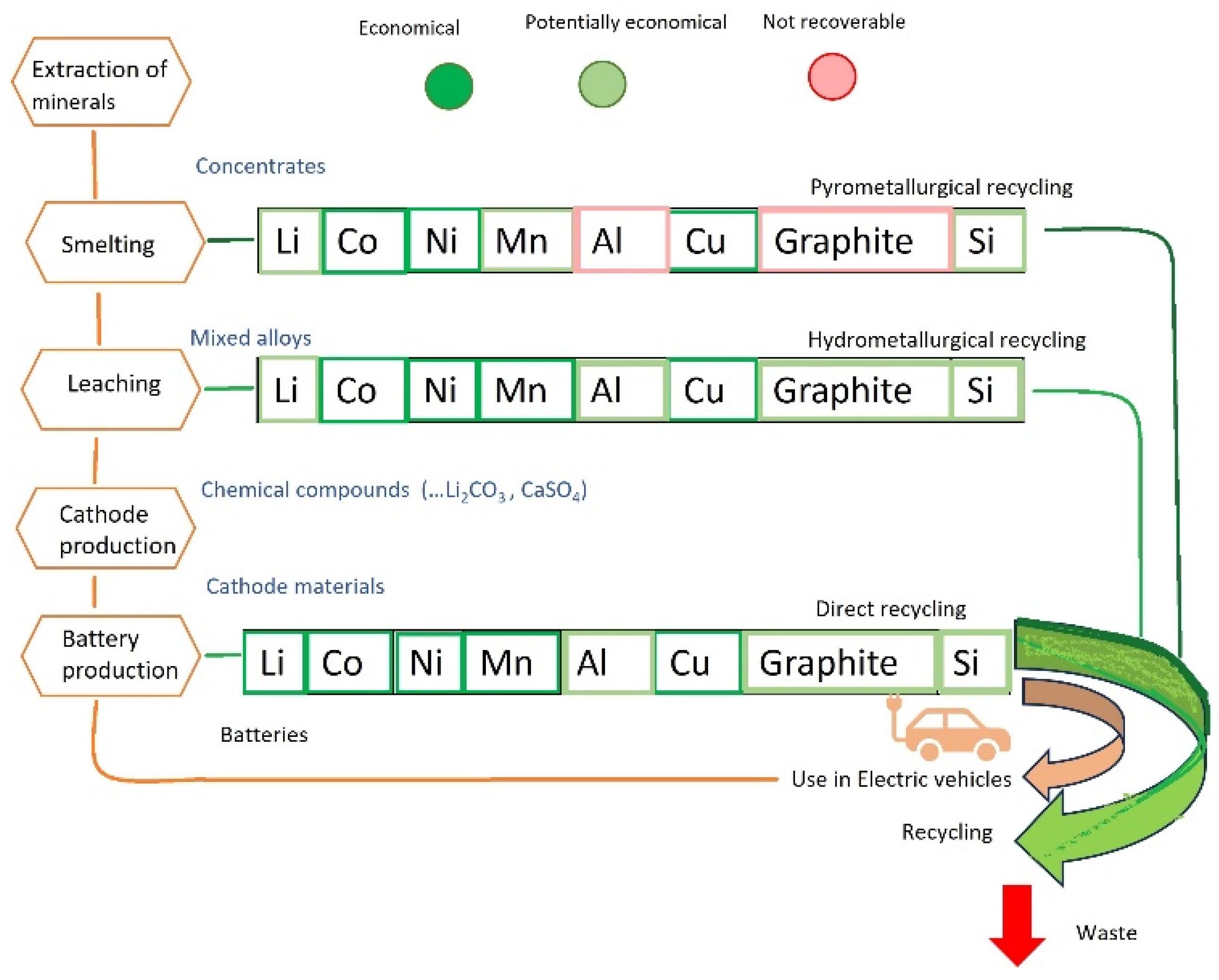

3.1. Blockchain in Metals Recycling

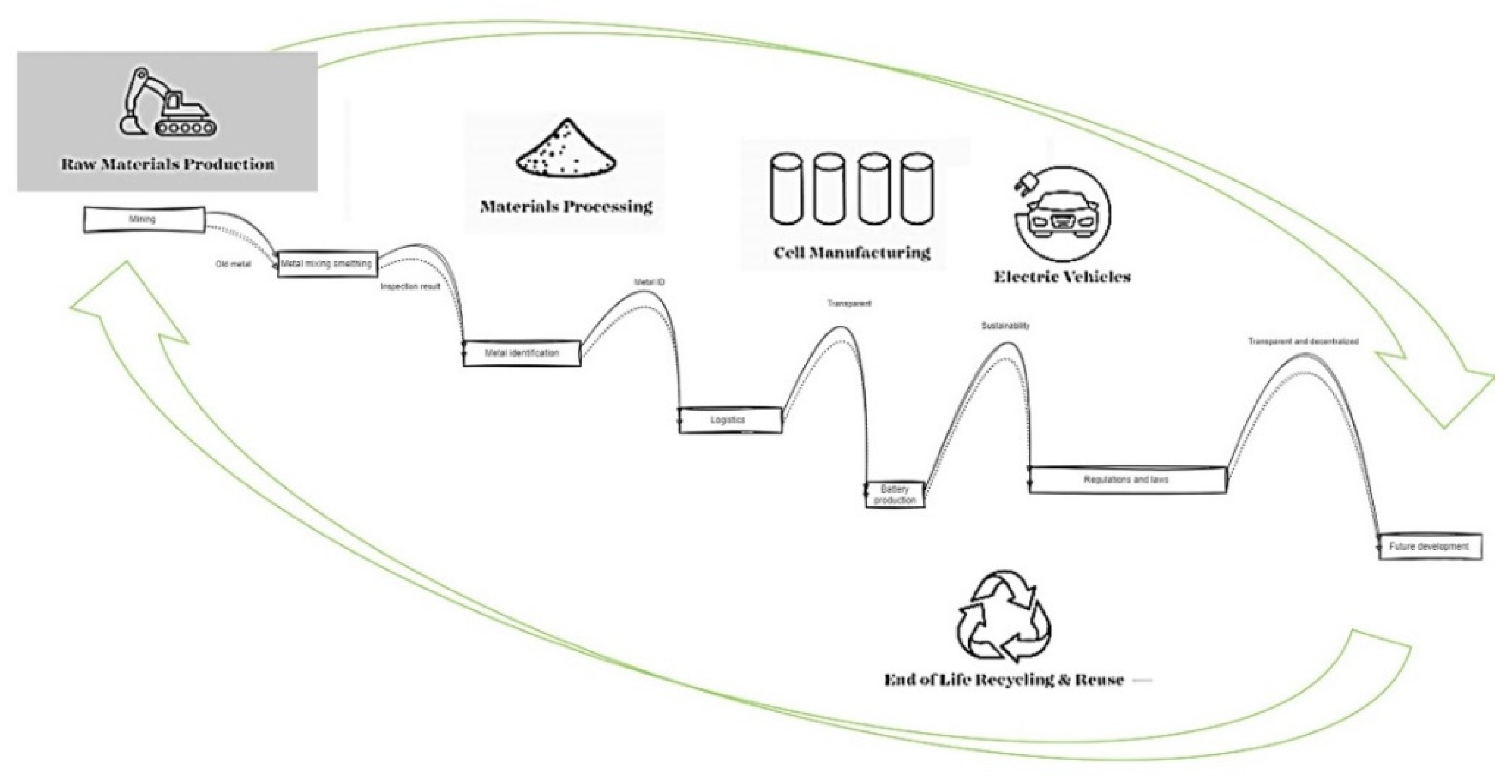

4. Electric Vehicles in Road to Sustainable Economy via Blockchain

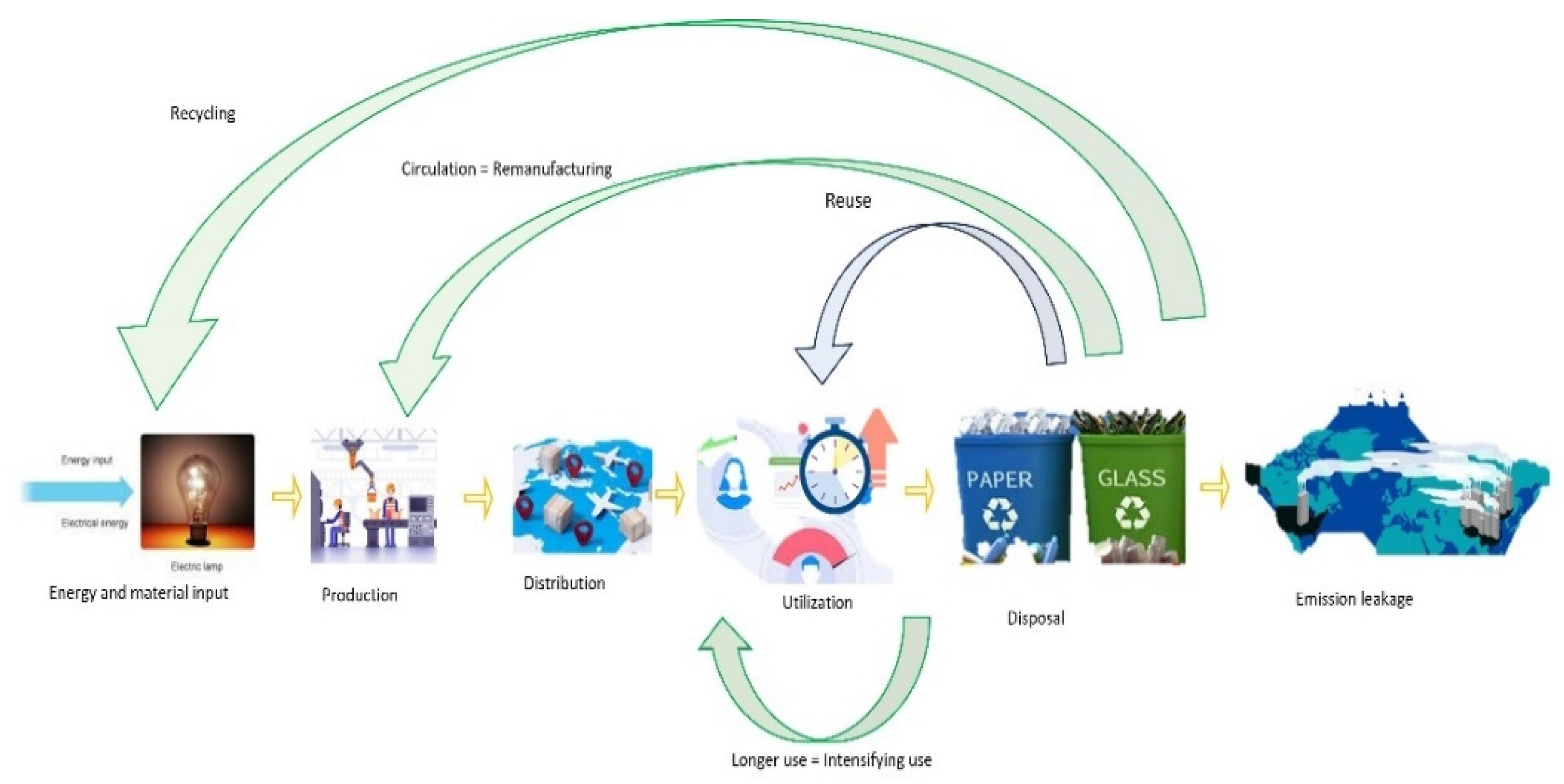

4.1. Road to Sustainable Practices in EV Production via Resource Balanced Economy

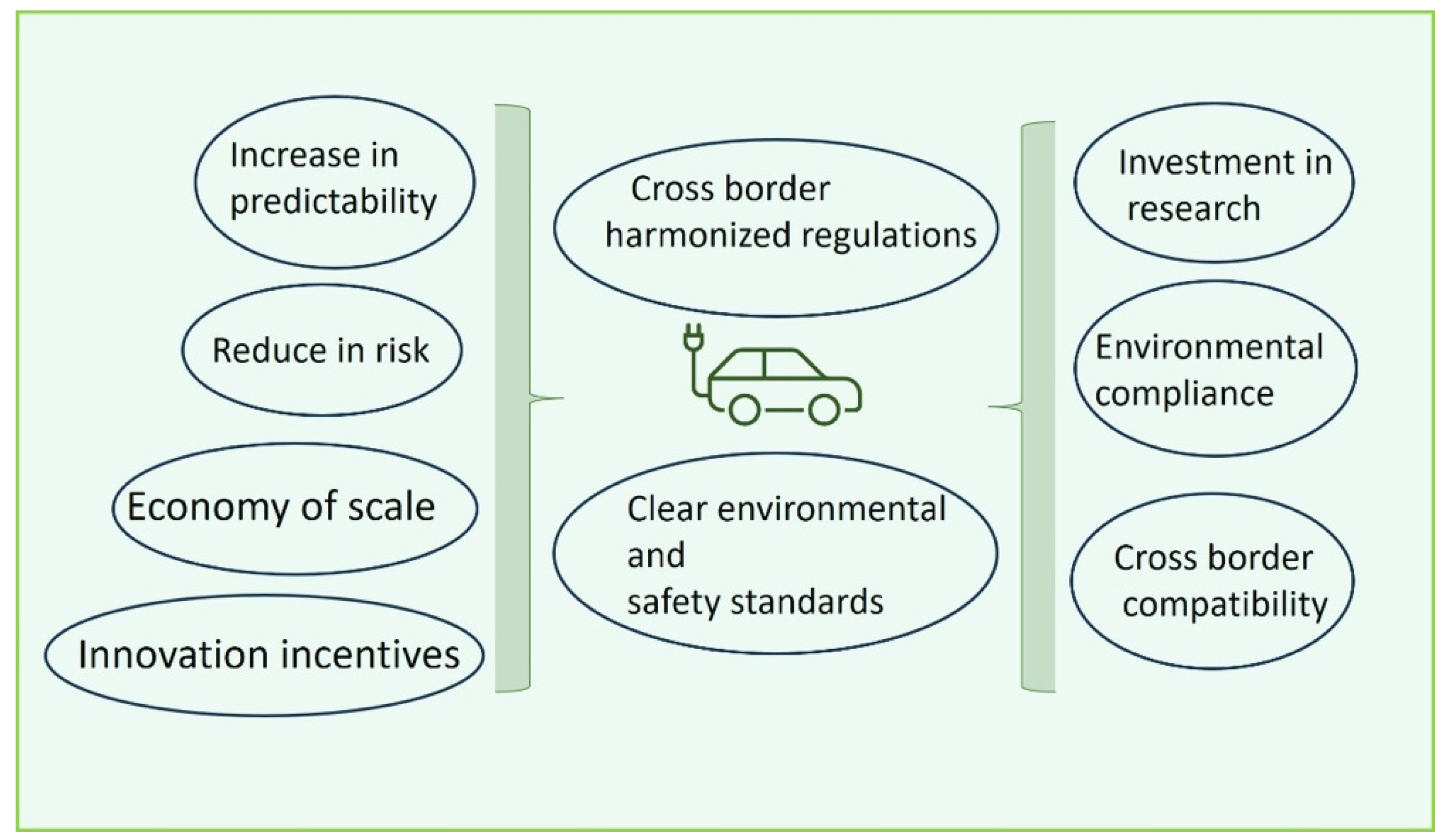

4.2. Standardization and Regulations for Sustainability of EVs

4.3. Key Challenges in International Standardization of EVs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| BEVs | Battery Electric Vehicles |

| PHEVs | Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles |

| OEMs | Original Equipment Manufacturers |

| NCA | Lithium Nickel Cobalt Aluminum Batteries |

| NCM | Lithium Nickel Cobalt Manganese Batteries |

| LIBSC | Lithium-Ion Battery Supply Chain |

| DOD | Depth Of Discharge |

| LLI | The Loss Of Lithium Inventory |

| LAM | Loss Of Active Material |

| CL | Conductivity Loss |

References

- Bibra, E. M.; Connelly, E.; Dhir, S.; Drtil, M.; Henriot, P.; Hwang, I.; Le Marois, JB.; McBain, S.; Paoli, L.; Teter, J. Global EV outlook 2022: Securing supplies for an electric future. 2022, 5, 221.

- Perišić, M.; Barceló, E.; Dimic-Misic, K.; Imani, M.; Spasojević Brkić, V. The role of bioeconomy in the future energy scenario: a state-of-the-art review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, R. F. D.; Dewulf, J.; Guinée, J.B.; Schulze, R.; Weihed, P.; Bark, G.; Drielsma, J. Towards product-oriented sustainability in the (primary) metal supply sector. Elsevier BV 2019, 145, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, F. E. K.; Furubayashi, T.; Nakata, T. Application of energy and CO2 reduction assessments for end-of-life vehicles recycling in Japan. Applied Energy 2019, 237, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barceló, E.; Dimić-Mišić, K.; Imani, M.; Spasojević Brkić, V.; Hummel, M.; Gane, P. Regulatory paradigm and challenge for blockchain integration of decentralized systems: Example—renewable energy grids. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaustad, G.; Krystofik, M.; Bustamante, M.; Badami, K. Circular economy strategies for mitigating critical material supply issues. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2018, 135, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, C.; Crawford, A. Green conflict minerals: The fuels of conflict in the transition to a low-carbon economy. International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2018, 279-304.

- Clausen, E.; Sörensen, A. Required and desired: breakthroughs for future-proofing miner-al and metal extraction. Mineral Economics 2022, 35, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurani, K. S. The state of electric vehicle markets, 2017: Growth faces an attention gap, (Policy Brief) 2019. [CrossRef]

- Mahrez, Z.; Sabir, E.; Badidi, E.; Saad, W.; Sadik, M. Smart urban mobility: When mobility systems meet smart data. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 23, 6222–6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishdad-Bozorgi, P.; Yoon, J H.; Dass, N. Blockchain-based Information Sharing: A New Opportunity for Construction Supply Chains.2020. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Abrantes, B. F. Blockchain Technology and the Future of Accounting and Auditing Services. In Essentials on Dynamic Capabilities for a Contemporary World: Recent Advances and Case Studies. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023, 169-190.

- Ghobakhloo, M. Industry 4. 0, digitization, and opportunities for sustainability. Journal of cleaner production 2020, 252, 119869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarenko, Y.; Garafonova, O.; Маргасoва, В.Г.; Ткаленкo, Н. Digital Transformation in the Mining Sector: Exploring Global Technology Trends and Managerial Issues. EDP Sciences 2021, 315, 04006–04006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Multi-angle Analysis of Electric Vehicles Battery Recycling and Utilization. IOP Publishing 2022, 1011, 012027–012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmers, E.; Marx, P. Electric cars: technical characteristics and environmental im-pacts. Springer Science+Business Media 2012, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kiziroglou, M.E.; Boyle, D. E.; Yeatman, E. M.; Cilliers, J. Opportunities for Sensing Systems in Mining. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers 2017, 13, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravishankar, B.; Kulkarni, P. When Block Chain and AI Integrates. In 2020 Internation-al Conference on Mainstreaming Block Chain Implementation (ICOMBI),2020, 1-4.

- Sánchez, F.; Hartlieb, P. Innovation in the Mining Industry: Technological Trends and a Case Study of the Challenges of Disruptive Innovation. Springer Science+Business Media 2020, 37, 1385–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnewold, L.; Lottermoser, B G. Identification of digital technologies and digitalisation trends in the mining industry. Elsevier BV 2020, 30, 747–757. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Song, X.; Liu, L.; Yin, J.; Wang, Y.; Lan, D. Recent Advances in Blockchain and Artificial Intelligence Integration: Feasibility Analysis, Research Issues, Applications, Challenges, and Future Work. Hindawi Publishing Corporation, 2021, 1-15.

- Filipović, D.; Trolle, A. B. The term structure of interbank risk. Journal of Financial Economics 2013, 109, 707–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanmathi, C.; Farouk, A.; Alhammad, S. M.; Mangayarkarasi, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Kasyapa, M. S. The Role of Blockchain in Transforming Industries Beyond Finance. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, S. Analysis on the Impact of Blockchain Technology on the Ac-counting Profession. In 7th International Conference on Economy, Management, Law and Education (EMLE 2021) Atlantis Press., 2021, 10-14.

- Zhironkin, S.; Szurgacz, D. Mining technologies innovative development: economic and sustainable outlook. Energies 2021, 14, 8590–8590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Salazar, J.; Tavares, L M.Sustainability in the Minerals Industry: Seeking a Consensus on Its Meaning. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 2018,10, 1429-1429.

- O’Fairchea llaigh, C. Social Equity and Large Mining Projects: Voluntary Industry Initiatives, Public Regulation and Community Development Agreements. Springer Science+Business Media 2014, 132, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Batterham, R. The mine of the future – Even more sustainable. Elsevier BV 2017, 107, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F P. Mining industry and sustainable development: time for change. Wiley-Blackwell 2017, 6, 61–77.

- Jennings, Clinton. An integrated “Mine to Mill” automation methodology applied to Sanbrado.2022, sear.unisq.edu.au/51872/12.

- Zhironkin, Sergey; Dawid, Szurgacz. Mining technologies innovative development: economic and sustainable outlook. Energies 2021, 14, 8590.

- Fortier, S. M.; Nassar, N. T.; Lederer, G. W.; Brainard, J.; Gambogi, J.; McCullough, E. A. Draft critical mineral list—Summary of methodology and background information—US Geological Survey technical input document in response to Secretarial Order No. 3359 (No. 2018-1021). US Geological Survey. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Crundwell, F. K.; Du Preez, N. B.; Knights, B. D. H. Production of cobalt from copper-cobalt ores on the African Copperbelt–An overview. Minerals Engineering 2020, 156, 106450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Penelope K., Ulrich Stimming, and Alpha A. Lee. Impedance-based forecasting of lithium-ion battery performance amid uneven usage. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 4806. [CrossRef]

- Scrosati, B.; Garche, J. Lithium batteries: Status, prospects and future. Journal of power sources 2010, 195, 2419–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubi, G.; Dufo-López, R.; Carvalho, M.; Pasaoglu, G. The lithium-ion battery: State of the art and future perspectives. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 2018, 89, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatipamula, S.; Malaarachchi, C.; Alam, M. R.; Khan, M. W.; Babarao, R.; Mahmood, N. Non-aqueous rechargeable aluminum-ion batteries (RABs): recent progress and future perspectives. Microstructures 2024, 4, N–A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, K.; Dutta, S.; Alessi, D. S.; Rinklebe, J.; Ok, Y. S.; Tsang, D. C. Recycling of lithium iron phosphate batteries: Status, technologies, challenges, and prospects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 163, 112515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.; Wang, C.; Wang, L. Y.; Strunz, K. Electric vehicle battery technologies. In Electric vehicle integration into modern power networks. New York, NY: Springer New York. 2012, 15-56.

- Konarov, A.; Myung, S. T.; Sun, Y. K. Cathode materials for future electric vehicles and energy storage systems. ACS Energy Letters 2017, 2, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koech, A. K.; Mwandila, G.; Mulolani, F.; Mwaanga, P. Lithium-ion battery fundamentals and exploration of cathode materials: A review. South African Journal of Chemical Engineering 2024, 50, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandhu, K.C.; Litoriya, R.; Lowanshi, P.; Jindal, M.; Chouhan, L.; Jain, S. Making drug supply chain secure traceable and efficient: a Blockchain and smart contract based imple-mentation. Springer Science+Business Media 2022, 82, 23541–23568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.M.; Sung, J.; Park, T. Applications of Blockchain to Improve Supply Chain Traceability. Elsevier BV 2019, 162, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyten, S.; Büscher, J.; Driesen, J.; Leemput, N.; Geth, F.; Roy, J. V. Standardization of conductive AC charging infrastructure for electric vehicles. 2013, 1-4.

- Khaleel, M.; Nassar, Y.; El-Khozondar, H. J.; Elmnifi, M.; Rajab, Z.; Yaghoubi, E.; Yaghoubi, E. Electric vehicles in China, Europe, and the United States: Current trend and market comparison. Int. J. Electr. Eng. and Sustain., 2024,1-20.

- Graham, J. D.; Belton, K. B.; Xia, S. How China beat the US in electric vehicle manu-facturing. Issues in Science and Technology 2021, 37, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Razmjoo, A.; Ghazanfari, A.; Jahangiri, M.; Franklin, E.; Denai, M.; Marzband, M.; Maheri, A. A comprehensive study on the expansion of electric vehicles in Europe. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 11656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatawneh, A.; Torok, A. A predictive modeling framework for forecasting cumulative sales of euro-compliant, battery-electric and autonomous vehicles. Decision Analytics Jour-nal, 2024,100483.

- Yu, R.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z. Research on Forecasting Sales of Pure Electric Vehicles in China Based on the Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average–Gray Relational Analysis–Support Vector Regression Model. Systems 2024, 12, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Feng, K.; Wang, P.; Yang, Y.; Sun, L.; Yang, F.; Chen, W.Q.; Li, J. China’s electric vehicle and climate ambitions jeopardized by surging critical material prices. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.; Hao, X.; Lin, Z.; Wang, H.; Bouchard, J.; He, X.Z.; Wu, J.; Zheng, R. Lv.; La-Clair, T. J. Light-duty plug-in electric vehicles in China: An overview on the market and its comparisons to the United States. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 112, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudet, A.; Larouche, F.; Amouzegar, K.; Bouchard, P.; Zaghib, K. Key challenges and opportunities for recycling electric vehicle battery materials. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niri, A. J.; Poelzer, G. A.; Zhang, S. E.; Rosenkranz, J.; Pettersson, M.; Ghorbani, Y. Sustainability challenges throughout the electric vehicle battery value chain. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 191, 114176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holroyd, Carin. “Corporate social responsibility, Indigenous Peoples and mining in Scandinavia.” Local Communities and the Mining Industry. Routledge, 2023. 103-122.

- Yang, A.; Liu, C.; Yang, D.; Lu, C. Electric vehicle adoption in a mature market: A case study of Norway. Journal of Transport Geography 2023, 106, 103489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, G.; Pode, G.; Diouf, B.; Pode, R. Sustainable Decarbonization of Road Transport: Policies, Current Status, and Challenges of Electric Vehicles. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzola, P.; Paoli, L.; Teter, J. Trends in the Global Vehicle Fleet: Managing the SUV shift and the EV transition.2023, COI: 20.500.12592/mctpg1.

- Mohammadi, F.; Saif, M. A comprehensive overview of electric vehicle batteries market. e-Prime-Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy 2023, 3, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, I.; Hall, D. Battery electric and plug-in hybrid vehicle uptake in European cities. Working paper 2023, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Muratalla, V. O.; Ramírez-Márquez, C.; Lira-Barragán, L. F.; Ponce-Ortega, J. M. (2024). Review of Lithium as a Strategic Resource for Electric Vehicle Battery Production: Availability, Extraction, and Future Prospects. Resources, 13(11), 148.

- Antony Jose, S.; Dworkin, L.; Montano, S.; Noack, W. C.; Rusche, N.; Williams, D.; Menezes, P. L. Pathways to Circular Economy for Electric Vehicle Batteries. Recycling 2024, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostovski, J. K. How a Battery and Key Metals Shortage Could Halt the Growth of the Electric Vehicle Market. In Global Energy Transition and Sustainable Development Challenges, Vol 2. Scenarios, Materials, and Technology, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland 2024, 125-140.

- Mancini, L.; Sala, S. Social impact assessment in the mining sector: Review and comparison of indicators frameworks. Elsevier BV 2018, 57, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudd, G M. Sustainable/responsible mining and ethical issues related to the Sustainable Development Goals. Geological Society of London 2020, 508, 187–199.

- Leon, E M.; Miller, S E. An applied analysis of the recyclability of electric vehicle battery packs. Elsevier BV 2020, 157, 104593–104593.

- Harper, G.; Sommerville, R.; Kendrick, E.; Driscoll, L L.; Slater, P R.; Stolkin, R.; Wal-ton, A.; Christensen, P.; Heidrich, O.; Lambert, S.; Abbott, A.P.; Ryder, K.S.; Gaines, L.; Anderson, P. A. Recycling lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles. Nature Portfolio 2019, 575, 75–86.

- Nordqvist, A., Wimmer, M., Grynienko, M. Gravity flow research at the Kiruna sublevel caving mine during the last decade and an outlook into the future. In MassMin 2020: Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference Exhibition on Mass Mining 2020, 505-518.

- Yin, J. Z.; Shi, A.; Yin, H.; Li, K.; Chao, Y. Global lithium product applications, mineral resources, markets and related issues. Global lithium product applications, mineral re-sources, markets and related 2024, 1, 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps-Barber, Z.; Trench, A.; Groves, D. I. Recent pegmatite-hosted spodumene discoveries in Western Australia: insights for lithium exploration in Australia and globally. Applied Earth Science 2022, 131, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, N. Externalized costs of electric automobility: social-ecological conflicts of lithium extraction in Chile (No. 144/2020). Working Paper. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Winjobi, O.; Kelly, J. C.; Dai, Q. Life-cycle analysis, by global region, of automotive lithium-ion nickel manganese cobalt batteries of varying nickel content. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2022, 32, e00415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lei, C.; He, P.; Li, J.; He, Z.; Cheng, Yi. Past, present and future of high-nickel materials. Nano Energy 2024, 119, 109070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A. L.; Fuchs, E. R.; Karplus, V. J.; Michalek, J. J. Electric vehicle battery chemistry affects supply chain disruption vulnerabilities. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, O. B.; Adiraju, V. A.; Lucht, B. L. Lithium cyano tris (2, 2, 2-trifluoroethyl) borate as a multifunctional electrolyte additive for high-performance lithium metal batteries. ACS Energy Letters 2021, 6, 3851–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, E.; Sörensen, A. Required and desired: breakthroughs for future-proofing min-eral and metal extraction. Springer Science+Business Media 2022, 35, 521–537. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, J.; Qi, W.; Chen, S. Fluoroethylene carbonate as an electrolyte additive for improving interfacial stability of high-voltage LiNi 0. 6 Co 0.2 Mn 0.2 O 2 cathode. Ionics 2019, 25, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Chengjian, X.; Qiang, D.; Gaines, L.; Hu, M.; Arnold, T.; Bernhard, S. Reply to: Concerns about global phosphorus demand for lithium-iron-phosphate batteries in the light electric vehicle sector. Communications Materials,2022, 3. [CrossRef]

- De Putter, T. “Cobalt means conflict”–Congolese cobalt, a critical element in lithium-ion batteries. In Paper presented at the meeting of the Section of Technical Sciences held on 2019, 65, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bernards, N. Child labour, cobalt and the London Metal Exchange: Fetish, fixing and the limits of financialization. Economy and Society 2021, 50, 542–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Deady, E. Graphite resources, and their potential to support battery supply chains, in Africa. British Geological Survey Open Report OR/21/039. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ramji, A.; Dayemo, K. Releasing the Pressure: Understanding Upstream Graphite Value Chains and Implications for Supply Diversification.2024, 30pp. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, J.; Cai, W. The Geological Characteristics, Resource Potential, and Development Status of Manganese Deposits in Africa. Minerals 2024, 14, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruko, R. O.; Edokpayi, J. N.; Msagati, T. A.; Tavengwa, N. T.; Ogola, H. J.; Ijoma, G.; Odiyo, J. O. Investigating the chromium status, heavy metal contamination, and ecological risk assessment via tannery waste disposal in sub-Saharan Africa (Kenya and South Africa). Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 42135–42149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwitwa, J.; German, L.; Muimba-Kankolongo, A.; Puntodewo, A. Governance and sustainability challenges in landscapes shaped by mining: Mining-forestry linkages and impacts in the Copper Belt of Zambia and the DR Congo. Forest policy and economics 2012, 25, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, K.; Deady, E.; Shaw, R. Lithium resources, and their potential to support battery supply chains, in Africa. British Geological Survey, (OR/21/037)2021.

- Umair, S.; Björklund, A.; Petersen, E. E. Social impact assessment of informal recycling of electronic ICT waste in Pakistan using UNEP SETAC guidelines. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2015, 95, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billy, R. G.; Müller, D. B. Aluminium use in passenger cars poses systemic challenges for recycling and GHG emissions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2023, 190, 106827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Elliott, R.; Nguyen-Tien, V. The EV revolution: The road ahead for critical raw materials demand. Elsevier BV 2020, 280, 115072–115072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, A.; Wu, C.; Rasmussen, K D.; Lee, S.; Lundhaug, M.; Müller, D. B.; Tan, J.; Keiding, J. K.;Liu, L.; Dai, T.; Wang, A.;Liu, G. Battery technology and recycling alone will not save the electric mobility transition from future cobalt shortages. Nature Portfolio, 2022,13. [CrossRef]

- Poole, C. J. M.; Basu, S. Systematic Review: Occupational illness in the waste and recycling sector. Occupational Medicine 2017, 67, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. A review on the industrial chain of recycling critical metals from electric vehicle batteries: Current status, challenges, and policy recommendations. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 204, 114806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, J.; Petranikova, M.; Meeus, M.; Gamarra, J. D.; Younesi, R.; Winter, M.; Nowak, S. Recycling of lithium-ion batteries—current state of the art, circular economy, and next generation recycling. Advanced energy materials 2022, 12, 2102917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Lu, Q. Design and Implementation of Data Sharing Traceability System Based on Blockchain Smart Contract. Hindawi Publishing Corporation, 2021, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Babaei, A.; Khedmati, M.; Jokar, M.R.A.; Tirkolaee, E.B. Designing an integrated blockchain-enabled supply chain network under uncertainty. Nature Portfolio, 2023,13(1). [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wakefield, R.; Lyu, S.; Jayasuriya, S.; Han, F.; Yi, X.; Yang, X.; Amarasinghe, G.; Chen, J. Public and private blockchain in construction business process and in-formation integration. Elsevier BV 2020, 118, 103276–103276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, N.; Eckhardt, A.; Jong, A. W.D. Understanding decentralized autonomous organizations from the inside. Springer Science+Business Media, 2023,33(1). [CrossRef]

- Leavins, J. R.; Ramaswamy, V. Improving Internal Control Over Fixed Assets with BLOCKCHAIN. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, P.; Ericsson, M.; Steinbach, V. Breakthrough technologies and innovations along the mineral raw materials supply chain — towards a sustainable and secure supply. Springer Science+Business Media 2022, 35, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difrancesco, R.M.; Meena, P.; Kumar, G. How blockchain technology improves sustain-able supply chain processes: a practical guide. Springer Science+Business Media 2022, 16, 620–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, U.; Joshi, B.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Hydrometallurgical Routes to Close the Loop of Electric Vehicle (EV) Lithium-Ion Batteries (LIBs) Value Chain: A Review. Springer Science+Business Media 2023, 9, 950–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sermpinis, T.; Sermpinis, C. Traceability Decentralization in Supply Chain Management Using Blockchain Technologies. Cornell University. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sauer, P C.; Seuring, S. Sustainable supply chain management for minerals. Elsevier BV, 2017, 151, 235-249. [CrossRef]

- Gaustad, G.; Krystofik, M.; Bustamante, M L.;Badami, K. Circular economy strategies for mitigating critical material supply issues. Elsevier BV, 2018,135, 24-33. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Mukhuty, S.; Kumar, V.; Kazançoğlu, Y. Blockchain technology and the circular economy: Implications for sustainability and social responsibility. Elsevier BV 2021, 293, 126130–126130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, S. Application of Blockchain Technology in Agricultural Water Rights Trade Management. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute 2022, 14, 7017–7017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noudeng, V.; Quan, N. V.; Xuan, T. D. A Future Perspective on Waste Management of Lithium-Ion Batteries for Electric Vehicles in Lao PDR: Current Status and Challenges. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute 2022, 19, 16169–16169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, A. The Geopolitical Risk and Strategic Uncertainty of Green Growth after the Ukraine Invasion: How the Circular Economy Can Decrease the Market Power of and Re-source Dependency on Critical Minerals. Springer Nature 2022, 3, 1099–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjaafar, S.; Chen, X.; Taneri, N.; Wan, G. A Permissioned Blockchain Business Model for Green Sourcing. RELX Group (Netherlands). 2021. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Thomas, H. R.; Francis, R. W.; Lum, K. R.; Wang, J.; Liang, B. A review of processes and technologies for the recycling of lithium-ion secondary batteries. Journal of Power Sources 2008, 177, 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Geng, F.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Y.; He, L.; Cheng, S. A Social Governance Scheme Based on Blockchain. IOP Publishing 2020, 1621, 012103–012103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutsey, N. Integrating electric vehicles within US and European efficiency regulations. International Council on Clean Transportation 2017, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, R.; Tang, J. H. C. G.; Yang, X.; Meng, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhuge, C. Investigating the factors influencing the electric vehicle market share: A comparative study of the European Union and United States. Applied Energy 2024, 355, 122327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiyan, S. P.; Pratap, C. B.; Stonier, A. A.; Peter, G.; Sherine, A.; Praghash, K.; Gan-ji, V. Comprehensive assessment of electric vehicle development, deployment, and policy initiatives to reduce GHG emissions: opportunities and challenges. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 53614–53639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florini, A. The International Energy Agency in global energy governance. Global Poli-cy 2011, 2, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, H. S.; Rahman, M. M.; Li, S.; Tan, C. W. Electric vehicles standards, charging infrastructure, and impact on grid integration: A technological review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 120, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguesa, J. A.; Torres-Sanz, V.; Garrido, P.; Martinez, F. J.; Marquez-Barja, J. M. A review on electric vehicles: Technologies and challenges. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 372–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetta, A.V. B.; Krümpel, V.; Cullen, E. Transparency with Blockchain and Physical Tracking Technologies: Enabling Traceability in Raw Material Supply Chains. 2021, 5, 1. [CrossRef]

- Green, J. M.; Hartman, B.; Glowacki, P. F. A system-based view of the standards and certification landscape for electric vehicles. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2016, 8, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.P.A.; Pyke, D. F.; Steenhof, P.A. Electric vehicles: The role and importance of standards in an emerging market. Elsevier BV 2010, 38, 3797–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzò, S.; Nasca, A. The environmental impact of electric vehicles: A novel life cycle-based evaluation framework and its applications to multi-country scenarios. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 315, 128005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, U.; Joshi, B.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Hydrometallurgical Routes to Close the Loop of Electric Vehicle (EV) Lithium-Ion Batteries (LIBs) Value Chain: A Review. Springer Science+Business Media 2023, 9, 950–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Lim, W.M.; Sivarajah, U.; Kaur, J. Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain Integration in Business: Trends from a Bibliometric-Content Analysis. Springer Science+Business Media 2022, 25, 871–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Qin, P.; Li, K.; Zhao, Z. A review of the state of health for lithium-ion batteries: Research status and suggestions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 261, 120813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Mikkili, S. Advancements in EV international standards: Charging, safety and grid integration with challenges and impacts. International Journal of Green Energy 2024, 21, 2672–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Label | Composition (%) | Explanation |

| NCM | NCM 622 | 60/20/20 (Ni/Co/Mn) | Cathode 60% Ni, 20% Co, 20% Mn |

| NCM 523 | 50/20/30 (Ni/Co/Mn) | Cathode 50% Ni, 20% Co, 30% Mn | |

| NCM 111 | 10/10/10 (Ni/Mn/Co) | Cathode Ni, Mn, Co (1:1:1 ratio). | |

| NCM 622-GL | 60/20/20 (Ni/Mn/Co) | Cathode NCM 622 with graphite layer. | |

| NCM 811-GL | 80/10/10 (Ni/Co/Mn) | Cathode 80% Ni, 10% Co, 10% Mn with graphite layer | |

| NCM 955-GL | 90/5/5 (Ni/Mn/Co) | Cathode 90% Ni, 5% Co, 5% Mn with graphite layer | |

| Other | NCA | Li, Ni, Co, Al | Specific weight ratios of Lithium, Nickel, Cobalt, and Aluminum as cathode. |

| LFP | Li-Fe phosphate battery | Lithium Iron Phosphate as cathode. | |

| Graphite (Si) | Graphite anode + Si | Anode is graphite with silicon to enhance performance. | |

| Li-S | Li-S battery | Cathode of Li and S. | |

| Li- | Air lithium-air battery | Lithium used as the anode and Oxygen from the air as the cathode material. |

| Important aspects | Essential Features | Characteristics and explanation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ensuring safety and performance | Consistency in quality within whole production cycle | Standardized manufacturing ensures EV components meet performance and safety standards, safe handling of hazardous materials like lithium-ion batteries to protect workers and the environment. |

| 2. | Facilitating recycling | Materials recovery efficiency with reduction of waste | Battery design standards enable efficient disassembly and extraction of valuable metals like lithium, cobalt, and nickel. |

| 3. | Environmental sustainability | Reducing emissions and managing hazardous materials | Regulations promote environmentally responsible EV production and ensure safe disposal or reuse of toxic substances. |

| 4. | Global compatibility | Regional harmonization with universal production and charging infrastructure. | Cross-border standardization ensures global compatibility, reducing trade barriers, infrastructure costs, and simplifying recycling and repairs. |

| 5. | Promotion of innovation | Intensified research aids in establishing new manufacturing standards |

Regulations set targets for battery efficiency, recycling, and emissions, while standardization ensures fair competition and sustainability |

| 6. | Economic benefits | Decrease in production costs benefits market stability | Standardized components reduce manufacturing costs, while regulations boost market stability and long-term investment in EV production and recycling. |

| 7 | Consumer confidence | Transparency in the transport and production establishes trust in the recycling process. |

Standardized labels and certifications inform consumers on environmental impact and safety, while regulations ensure responsible EV recycling. |

| 8 | Critical material availability | Efficient use of scarce resources with sustainable sourcing | Recycling regulations reduce reliance on mining, while ethical sourcing prevents child labor and environmental harm. |

| Category | Number | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | ISO 26262 | Functional safety for automotive systems, focusing on risk management in electrical and electronic systems. |

| IEC 62133 | Safety requirements for portable sealed secondary cells and batteries, ensuring safe operation, handling, and protection from hazards. | |

| Euro NCAP / NHTSA | Vehicle crashworthiness and occupant safety standards, including specific guidelines for EVs. | |

| Charging | IEC 62196 | Specifies physical connectors and protocols for EV charging to ensure global interoperability. |

| CHAdeMO, CCS, Tesla Supercharger | Charging protocols define communication between vehicles and charging stations for fast charging and compatibility. | |

| Environmental and Emission | EU Battery Directive (2006/66/EC) | Ensures proper battery recycling and disposal to minimize environmental impact. |

| U.S. EPA Energy Efficiency Standards | Regulations ensuring EVs meet energy efficiency targets to reduce overall energy consumption. | |

| Management Standards | ISO 9001 | Quality management system standards ensure consistency and quality in manufacturing processes. |

| ISO 14001 | Environmental management standards to reduce ecological impact in manufacturing. | |

| ISO 15118 | Defines communication standards between EVs and charging stations to enable smart charging and grid integration. | |

| Performance Standards | Range and Charging Time Standards | Defines the acceptable range of vehicles on a single charge and the time required for charging. |

| Thermal Management Standards | Sets guidelines for battery cooling and heating systems to maintain optimal battery performance in varying temperatures. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).