1. Introduction

Ultra-High-Performance Concrete (UHPC) has emerged as a significant and innovative construction material in mid-1990s [

1]. Richard and Cheyrezy made a substantial contribution to the development of UHPC through their creation of Reactive Powder Concrete (RPC), an exceptionally enhanced material that represents a major advance in the evolution of construction material [

2]. With an ever-increasing research, UHPC has led to its widespread application globally, particularly in the construction of bridges, infrastructure, and other critical structures [

3,

4,

5]. Compared with conventional concrete, UHPC exhibits ultra-high compressive strength (commonly > 120 MPa), post-cracking strength (typically > 5 MPa), and remarkable durability. These outstanding properties are primarily attributed to a low water-to-binder ratio (usually < 0.2), a high fineness of supplementary materials, a discontinuous pore structure, and a high-volume fraction of high-strength steel fibers [

6,

7,

8]. Numerous studies have shown that it is crucial to understand the mechanical responses of UHPC under different loading conditions for further investigation into its structural performance [

9], especially for the UHPC with superior bending and tensile properties [

10]. Graybeal et al. [

11] developed a direct tension testing method, which facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of the tensile response of UHPC and its implications for structural design. A comprehensive literature review reveals that extensive research has been conducted on the flexural behaviors of reinforced UHPC beams. This research has investigated a multitude of variables, including specimen size [

12,

13], compressive strength of UHPC [

14,

15,

16], reinforcement ratios of steel rebars [

6,

12,

17,

18,

19], and the types/shapes and volume fractions of steel fibers [

6,

15,

16,

20]. The findings of these studies have considerably advanced both the design optimization and structural application of UHPC beams [

6,

12,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

However, existing research regarding the flexural performance of reinforced UHPC elements is frequently based on a limited number of specimens considering a narrow range of parameter variables. Consequently, it is time-consuming and labor-intensive, and the conclusions obtained may be overestimated or insufficient to comprehensively describe the exact influence of these parameters. Furthermore, design codes and structural standards for UHPC beams remain relatively limited [

22,

23], despite some analytical methods and finite element models having been presented on the basis of some simplification assumptions with certain limitations. Therefore, additional experimental and analytical investigations are required to develop an efficient and energy-saving method to predict the flexural properties of UHPC-based structural elements [

13,

24,

25,

26].

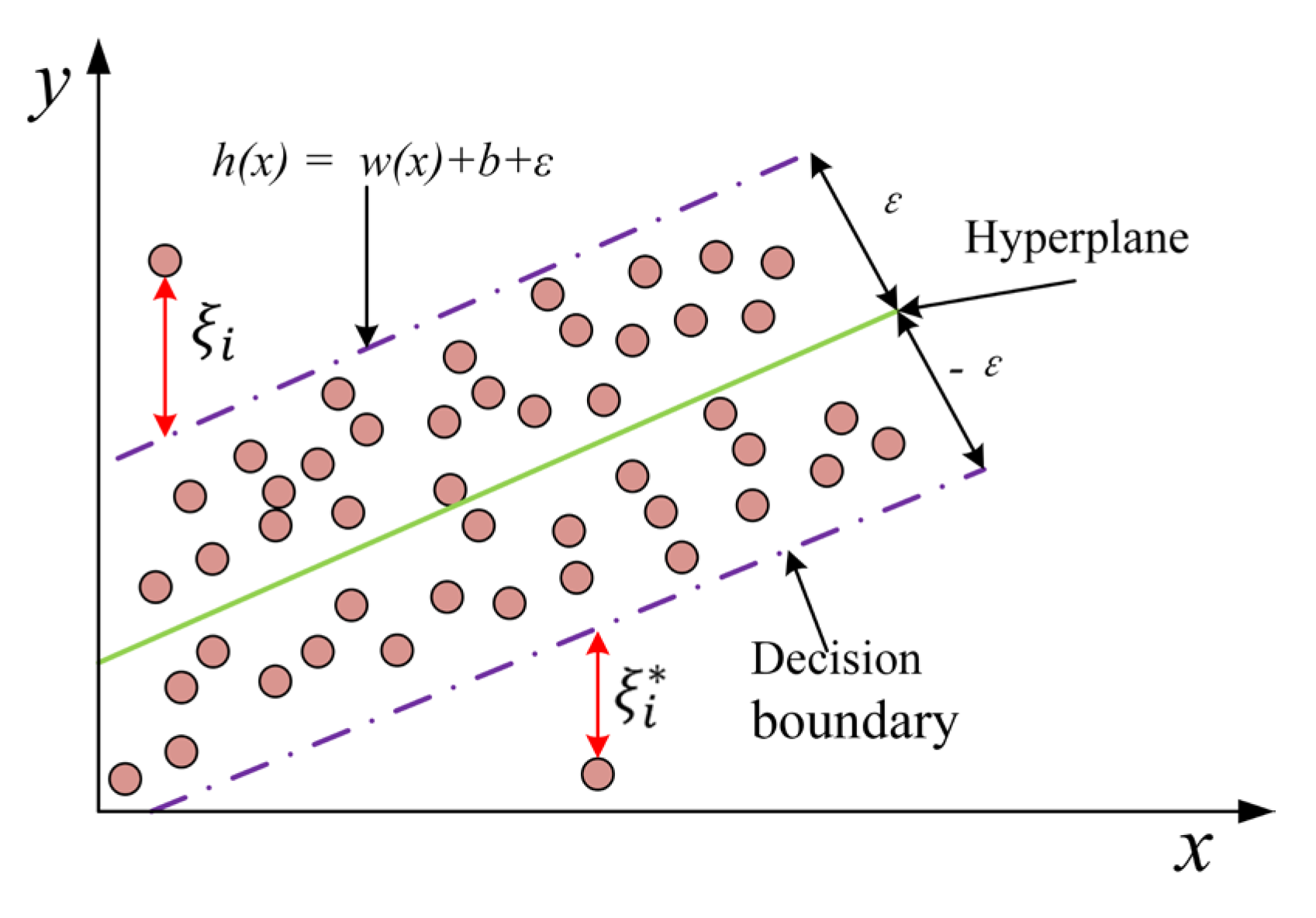

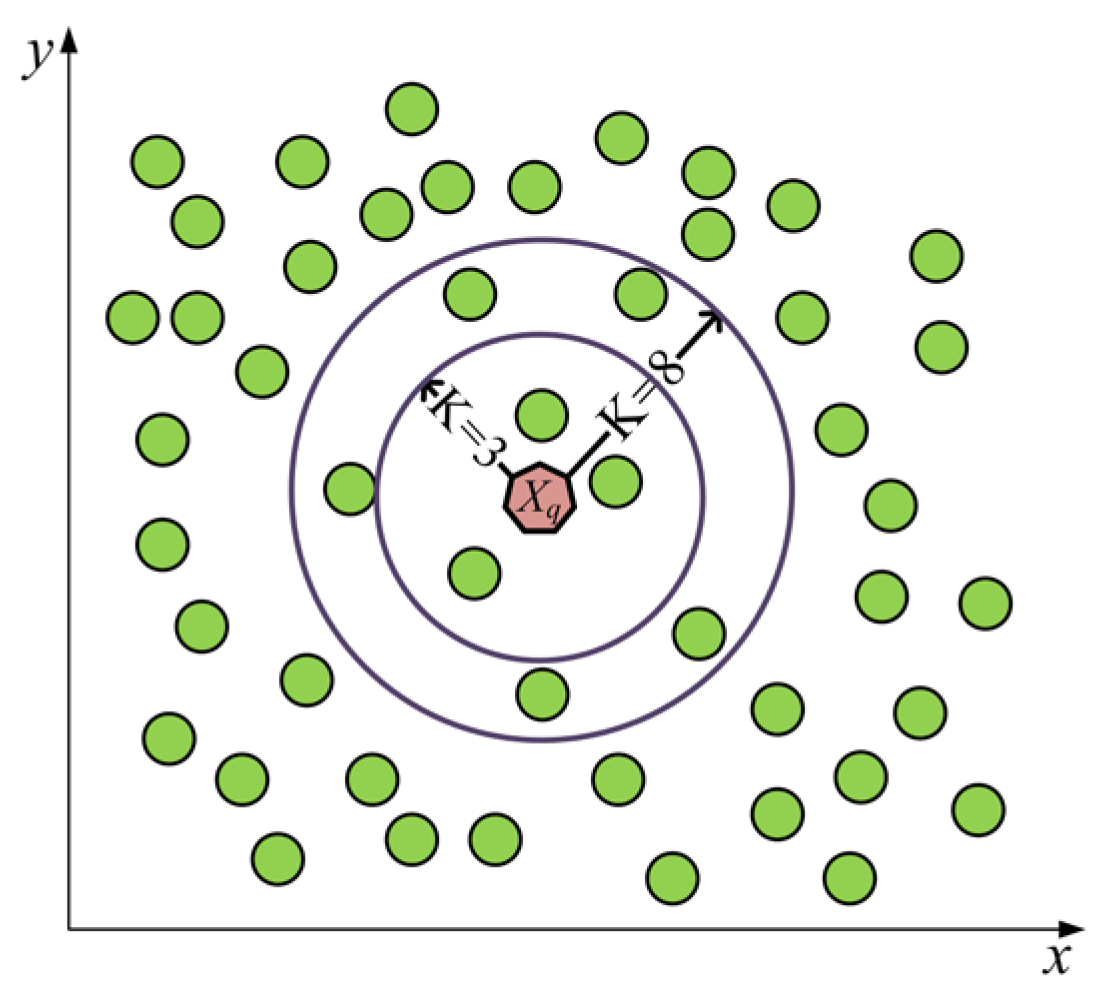

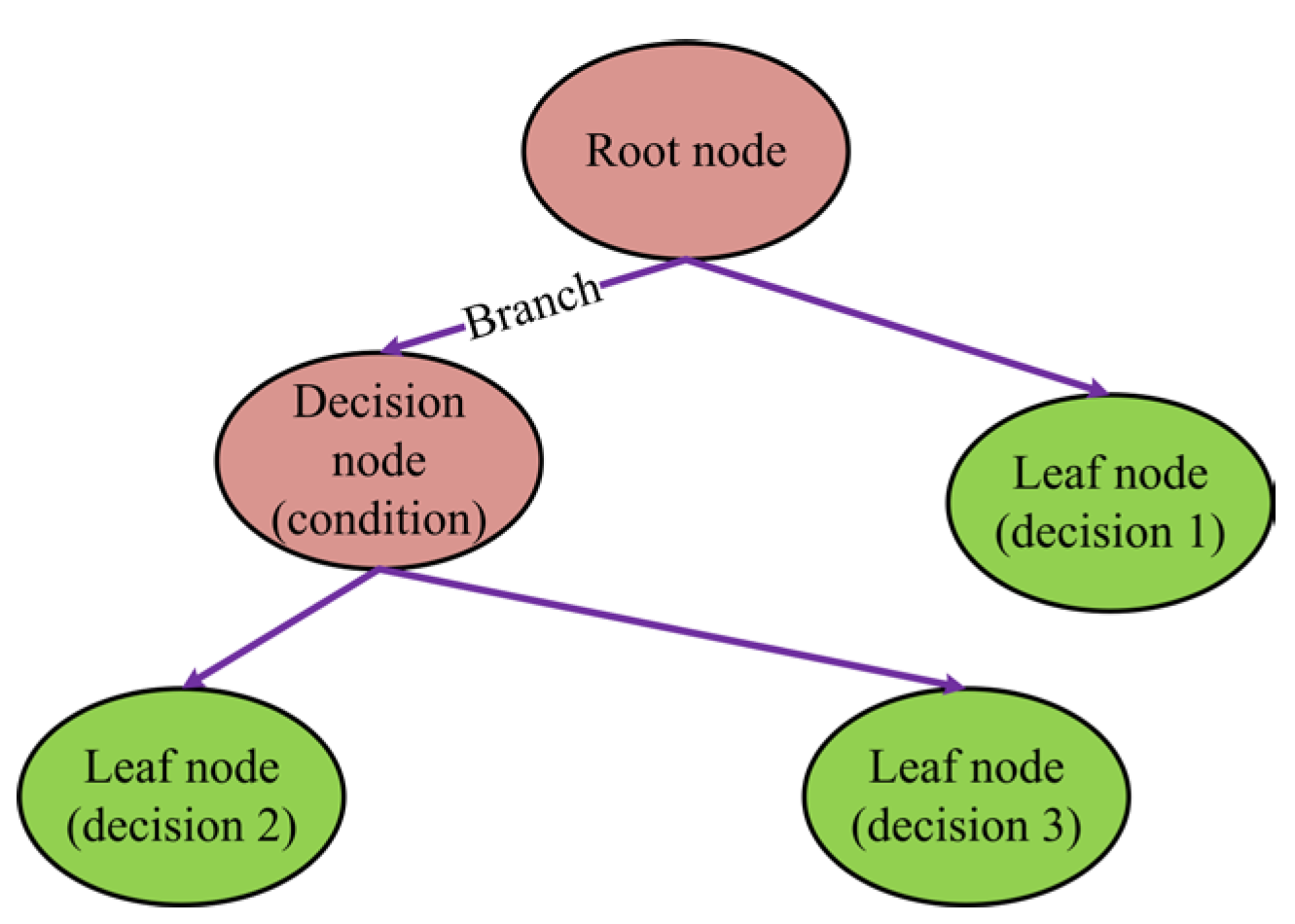

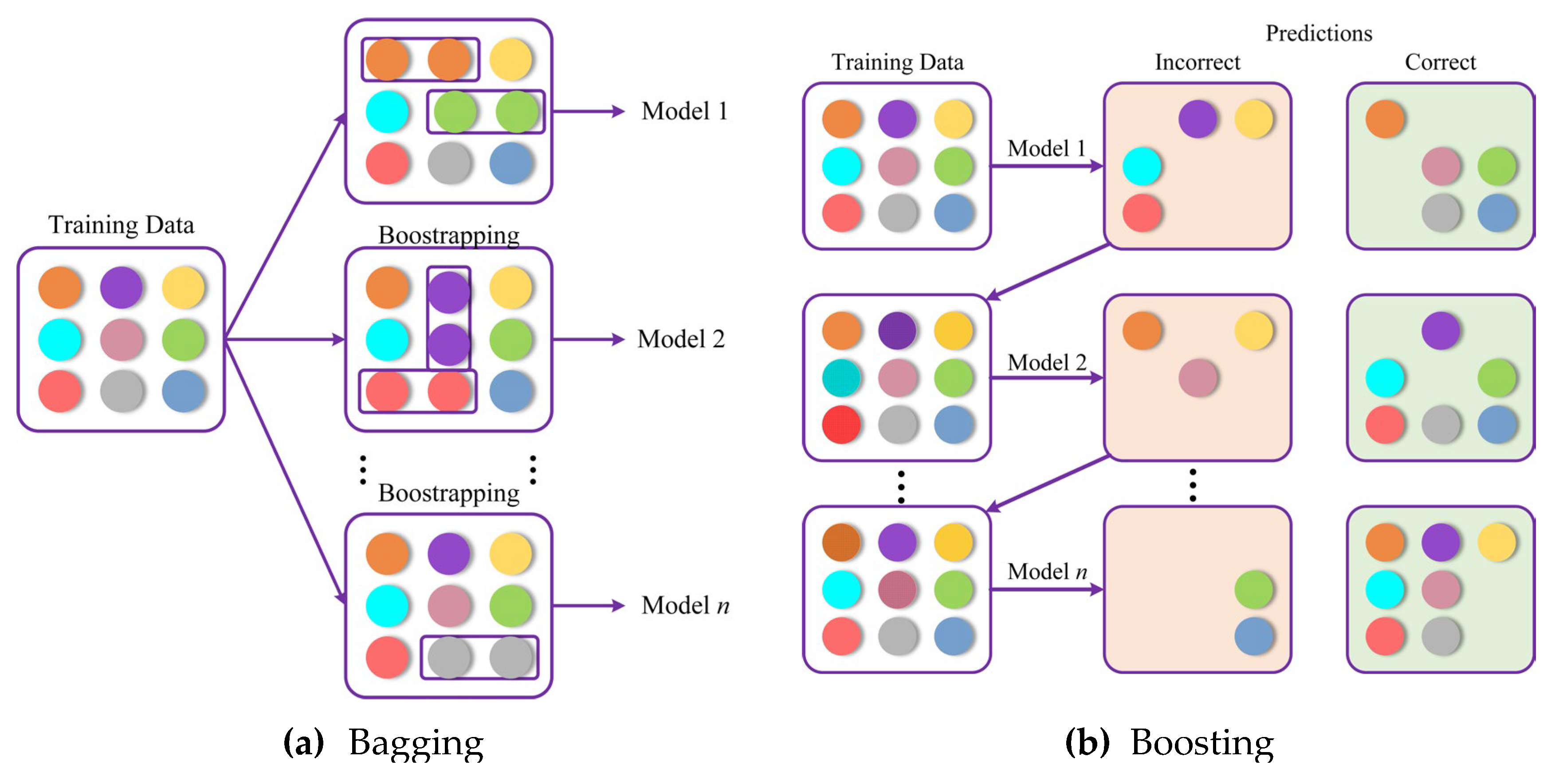

In recent years, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful and versatile tool with a wide range of applications within the field of civil engineering, particularly in the context of predicting the performance of advanced building materials such as UHPC. The application of ML provides an effective and robust platform for predicting structural response of UHPC-based elements, thereby significantly reducing the time and effort required for experimentation and modeling [

27]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that ML methods have been employed to predict basic properties of UHPC such as compressive strength, flexural strength, workability, and shrinkage performance, as well as to forecast the interface bonding strength and thus develop interpretable models that optimize UHPC mix designs [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Particularly, ML techniques offer significant advantages in predicting diverse properties of UHPC under various loading conditions, which include compressive strength, flexural strength, ultimate capacity, and fracture characteristics. Moreover, ML techniques have been utilized to determine the structural performance of reinforced concrete or UHPC beams [

30,

31,

32,

33]. A gradient boosting regression tree (GBRT) was used by Fu and Feng [

29] to forecast the residual shear strength of corroded reinforced concrete beams at different service periods. Feng et al. [

32] applied an ensemble learning method to predict the shear strength of reinforced concrete deep beams, demonstrating that the ensemble ML models outperformed traditional mechanics-based models in terms of improved prediction accuracy and reduced bias. Similarly, a variety of ML algorithms, including support vector machines (SVM), artificial neural networks (ANN) and ensemble learning (EL) methods, have also been used to identify failure modes and predict shear capacity of UHPC beams under combined bending and shear forces, achieving a high prediction accuracy [

31,

32,

33].

Despite the presence of application of ML methods to predict the shear performance of UHPC beams, there is a growing interest in employing ML technologies to accurately and efficiently predict the flexural behavior of reinforced UHPC beams. However, this remains an emerging area of research, with few published studies exploring its application. Solhmirzaei et al. [

33] used support vector regression (SVR) and genetic programming to predict the flexural capacity of UHPC beams with varying cross-sectional dimensions and material properties. Ergen and Katlav [

34] explored the potential of deep learning (DL) models for predicting the flexural capacity of UHPC beams with and without steel fibers. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of ML models is largely contingent upon the quality of database acquisition, frequently challenged by the selection of input variables. It is therefore important to expand and optimize the database of reinforced UHPC beam specimens. Specifically, the selection of input parameters for the optimized database should be both comprehensive and concise to achieve more reliable and convenient predictions of the bending performance of reinforced UHPC beams. The employment of excessive input parameters is impractical for real-world design applications, while the inclusion of interrelated input parameters unnecessarily inflates the input features without adding a unique or distinct value to the ML model. Further, the versatility of ML algorithms has been shown to result in notable discrepancies in both the accuracy and efficiency of the performance predictions of reinforced UHPC specimens. A comprehensive assessment and comparison of the accuracy and efficiency of various ML models for predicting the flexural ultimate capacity of reinforced UHPC beams is a crucial gap in the current research. Moreover, in the context of machine learning, the division of the original database into training and testing sets represents a fundamental stage in the data processing. The extent to which the training set is divided affects the performance of the ML model in terms of both the accuracy of training and its capacity to generalize to new data. The optimal division ratio of training set to testing set depends on the subset size and characteristics of the database. It is necessary to analyze the model performance on varying subsets of data to ensure an efficient evaluation of both the model and the data quality. Besides statistical evaluations of ML techniques, an adequate discussion is required regarding the physical and structural principles governing reinforced UHPC beams. For practical engineering applications, the comparison of EL models with physical principles alongside statistical model evaluations is essential. Previous research has shown that the Categorical Gradient Boosting (CatBoost) model has excellent predictive stability and generalization ability [

35]. To evaluate the accuracy and reliability of EL methods, the CatBoost method is exemplified and compared with existing empirical methods and design standards [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Additionally, it could be reasonably argued that the differences between various ML algorithms can significantly affect the reliability of parameter analysis in model interpretation. Therefore, it would appear prudent to undertake further research into a comparison of different ML models. SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) offers a promising method to clarify the contributions of features to predictions and has been widely used for model interpretation [

22,

30,

35,

41]. An in-depth analysis using SHAP method should be carried out by taking account into the impact of key design parameters on performance prediction to provide valuable insights for structural design purposes. Therefore, the prediction of flexural ultimate capacity for reinforced UHPC beams using ensemble learning and SHAP methods is promising.

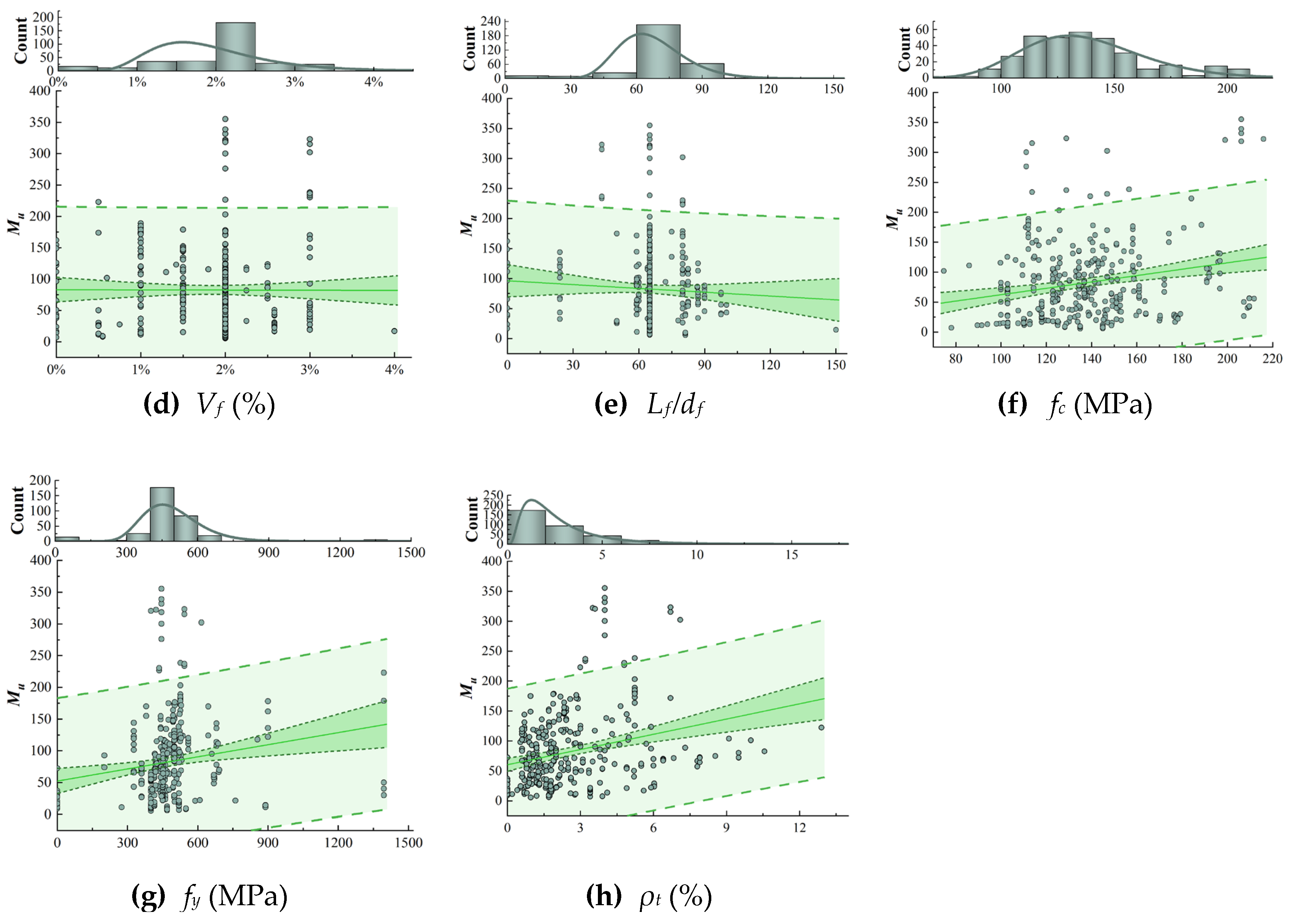

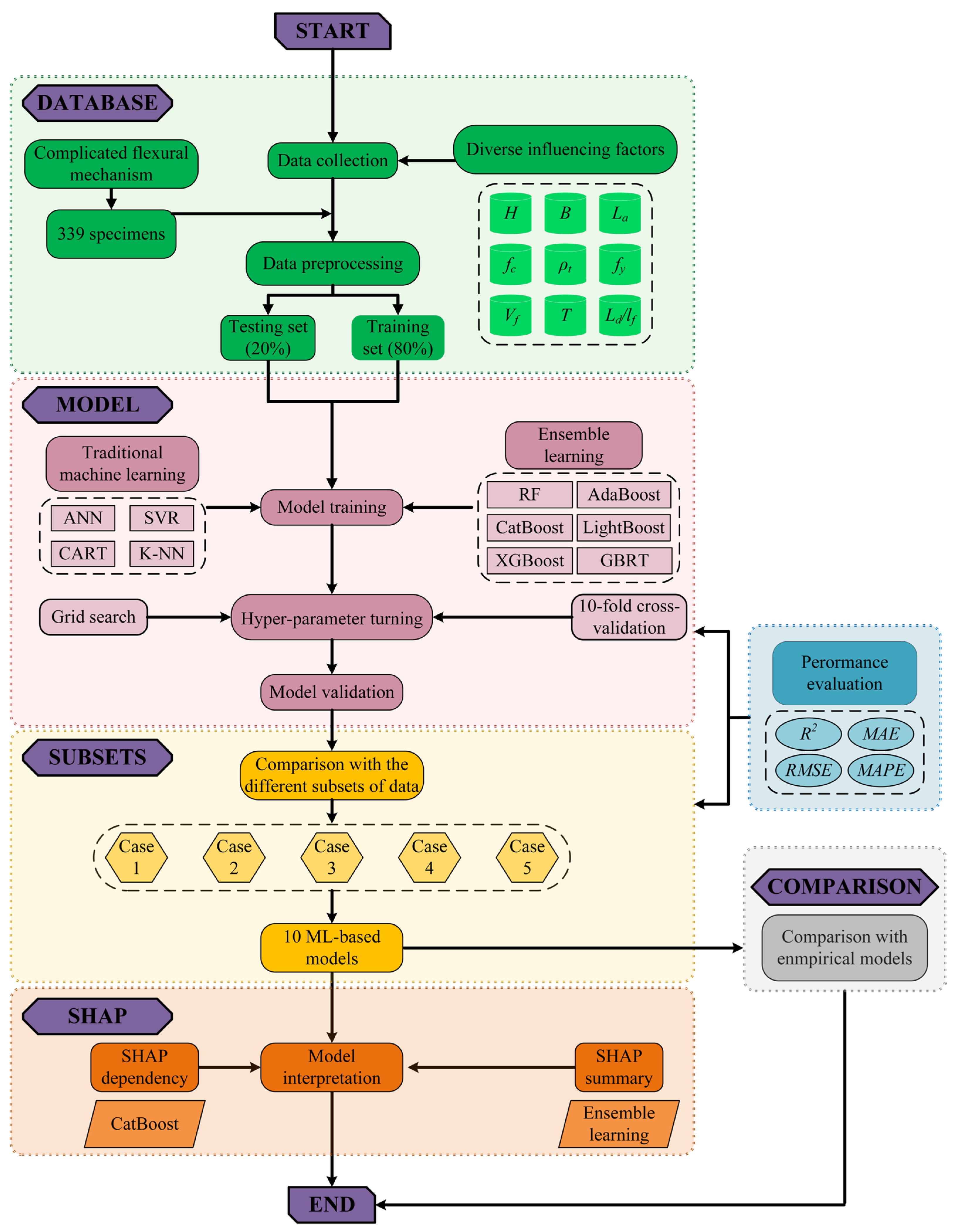

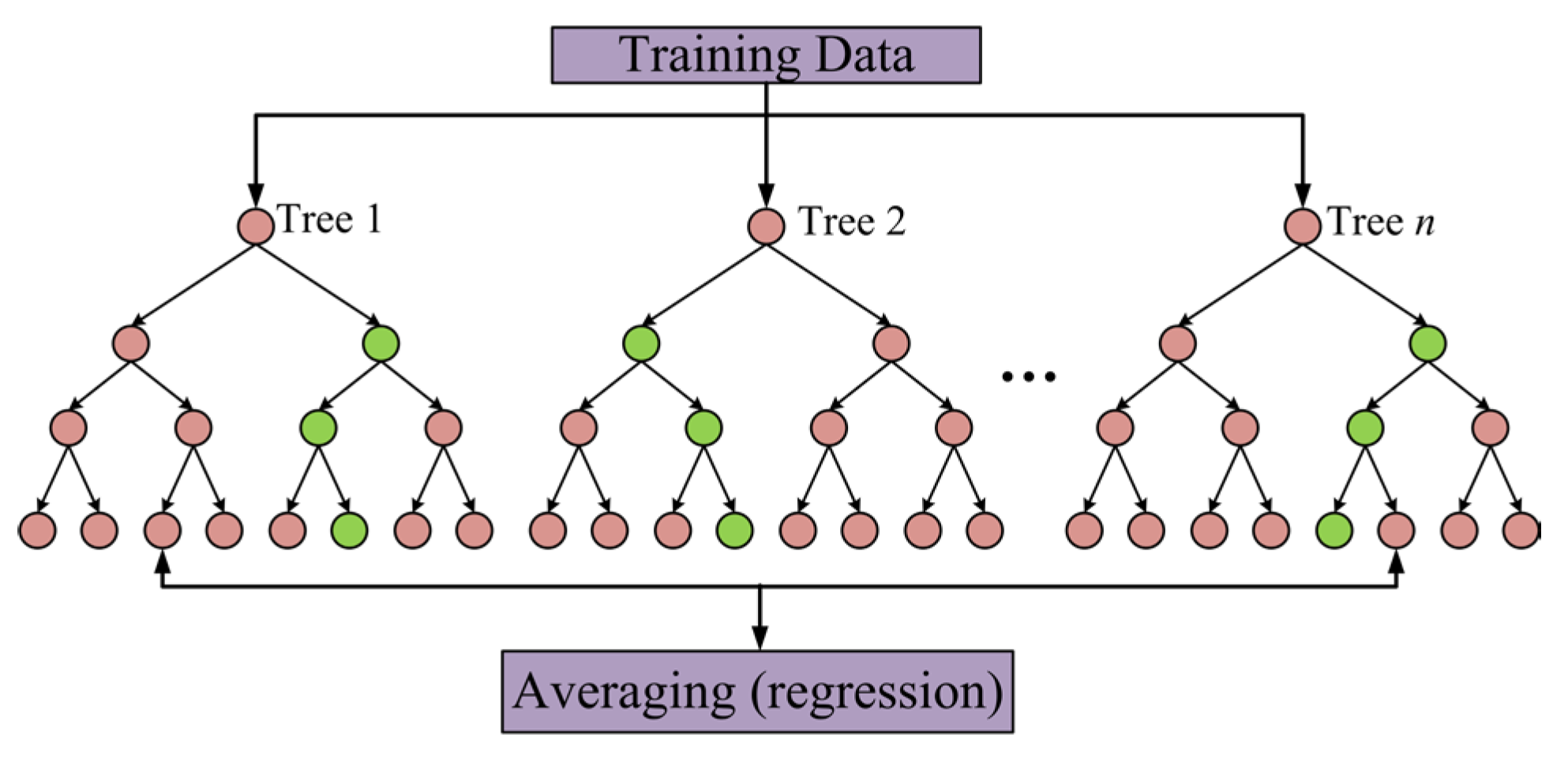

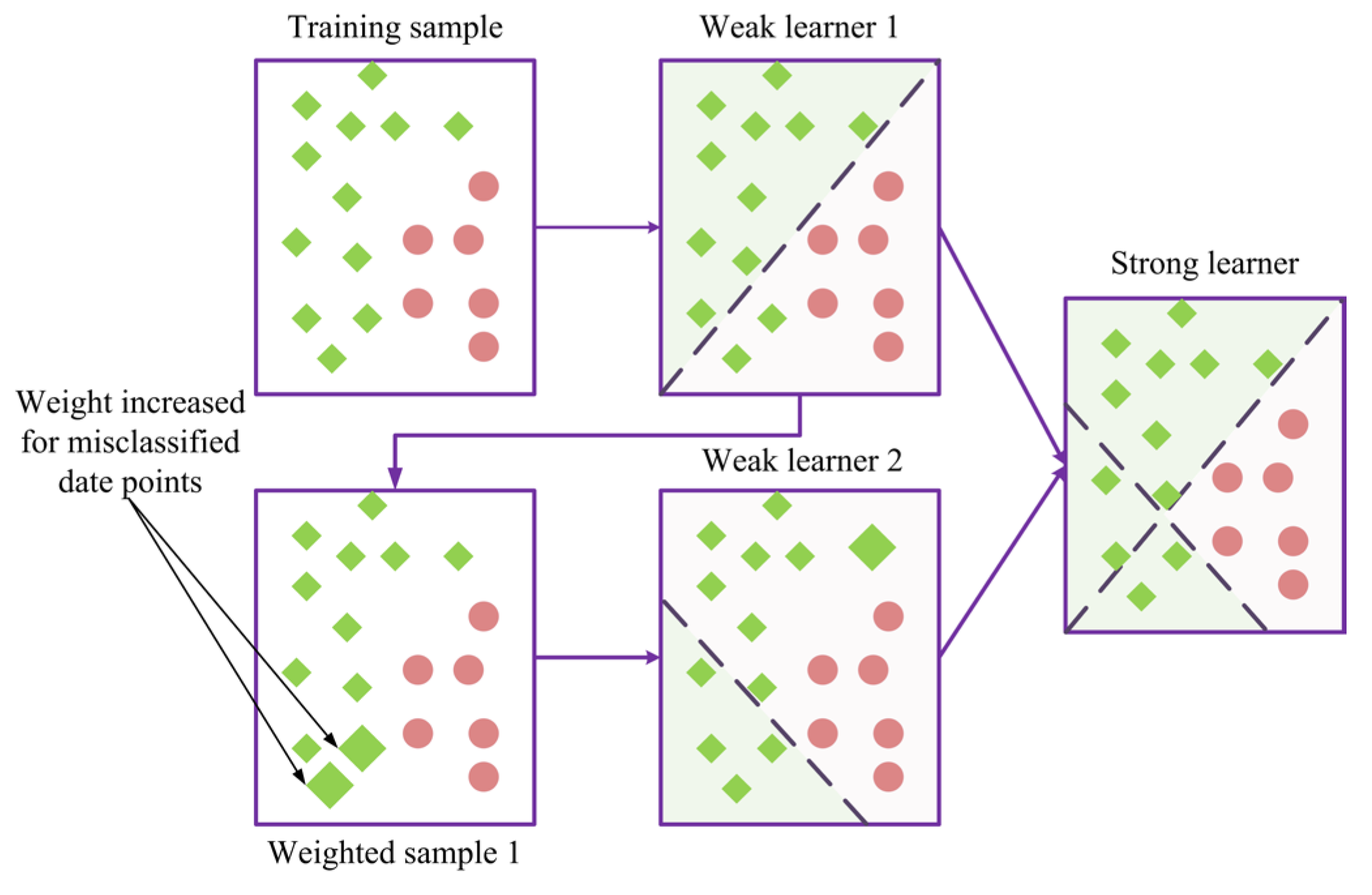

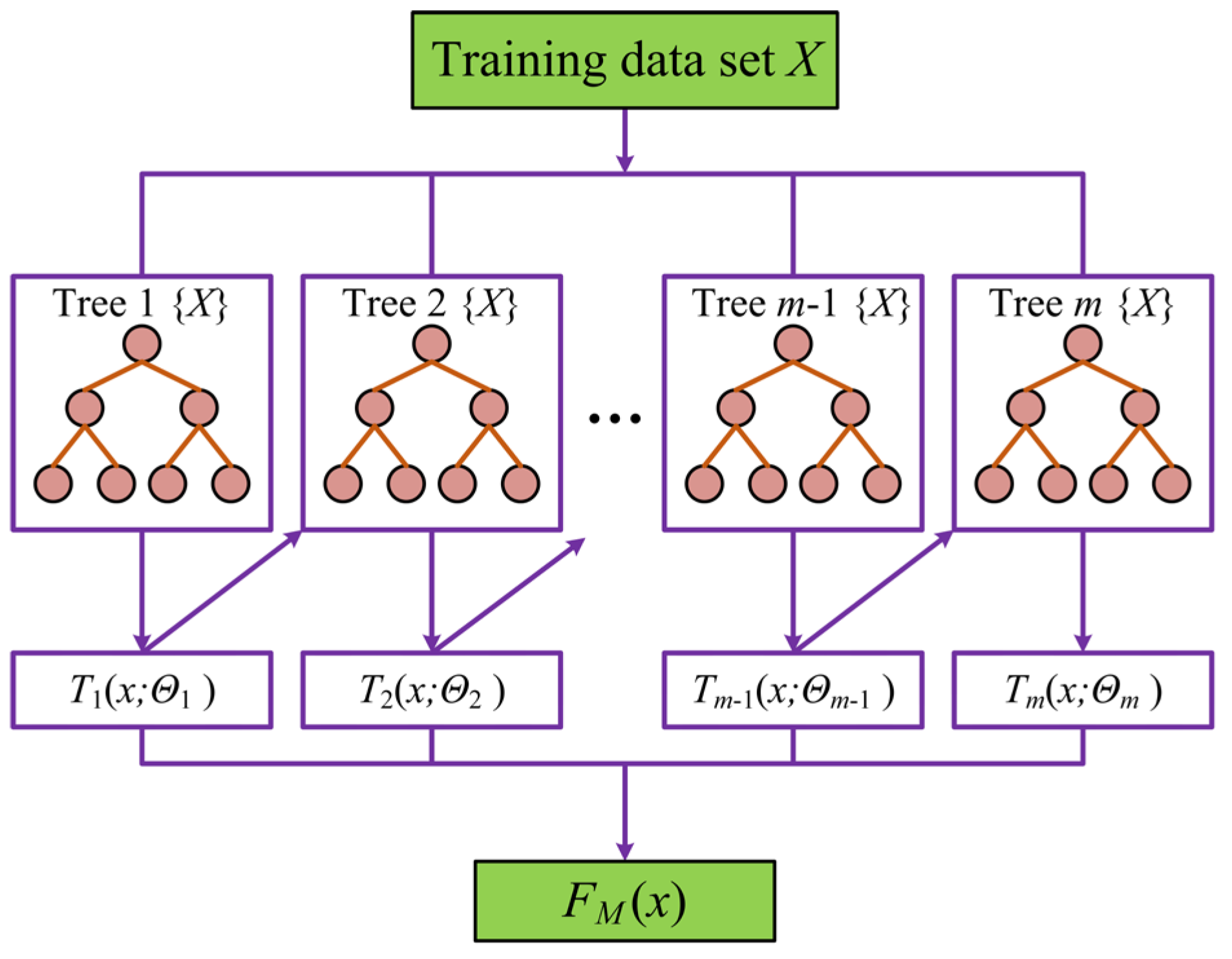

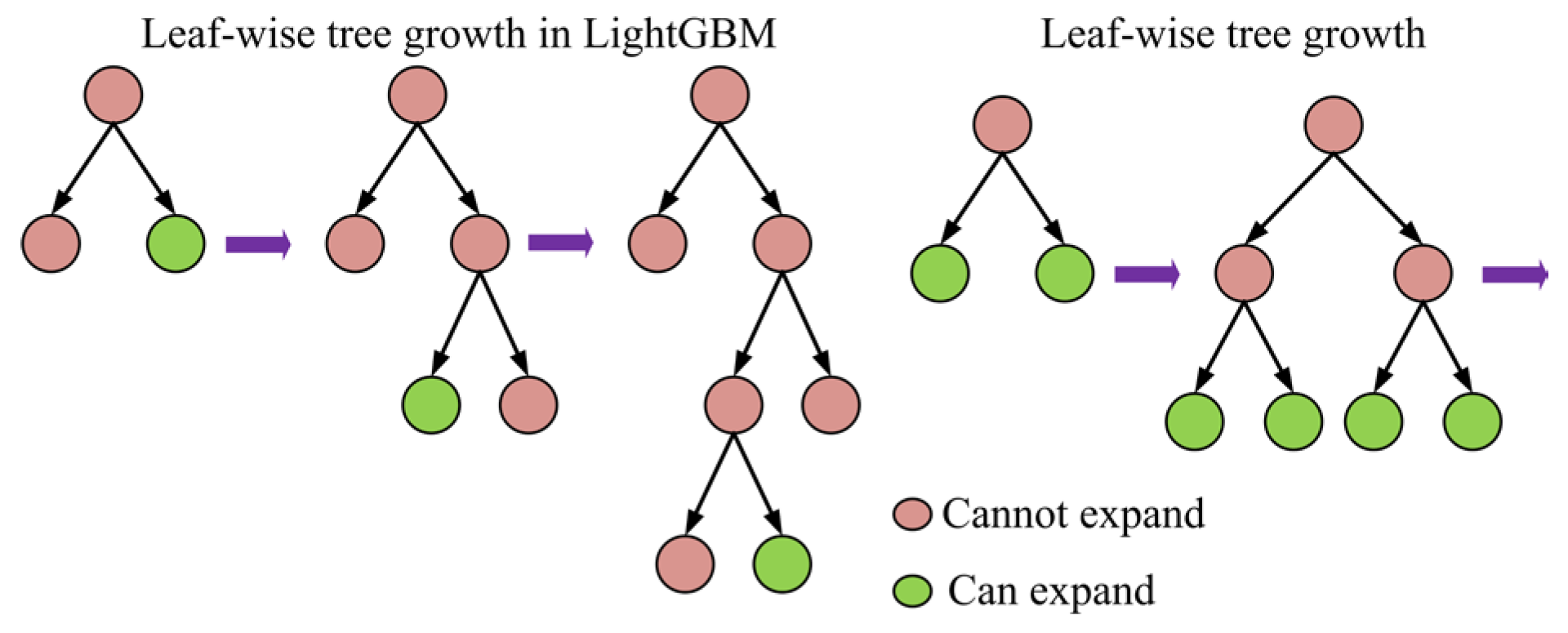

The objective of this study is to address aforementioned limitations by expanding the database and optimizing ML algorithms, thereby achieving greater accuracy and efficiency in predicting the flexural performance of reinforced UHPC beams and providing more reliable and efficient design recommendations for future applications. To be more specific, a comprehensive database containing 339 testing data of reinforced UHPC beams with various design parameters is initially established. To balance model accuracy and practical implementation, a reliable and efficient approach involving 9 input parameters is considered in this study. Furthermore, several ML algorithms are presented to develop optimized models for precisely predicting the flexural ultimate capacity (Mu) of reinforced UHPC specimens derived from the established database. Traditional models, including ANN, SVR, and K-Nearest Neighbors (K-NN), are first applied to make predictions. Additionally, ensemble learning models, such as Classification and Regression Trees (CART), Random Forest (RF), Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost), and Gradient Boosting Regression Trees (GBRT), are utilized for further optimization. To enhance prediction accuracy, advanced models like Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), CatBoost, and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) are also employed. The performance of ML models used is then evaluated using four statistical indicators to comprehensively assess and compare their prediction accuracies and capabilities for the flexural ultimate capacity of reinforced UHPC specimens. Subsequently, the sensitivity of ML models to varying data subsets is analyzed to ensure a highly efficient evaluation of ML models used and the established database. Moreover, the CatBoost model is exemplified to compare the predictions with several existing empirical formulas alongside statistical evaluations for practical engineering applications. Finally, the SHAP method is employed to interpret multiple EL models, thereby substantiating their reliability and determining the extent of influence exerted by each feature on the prediction results of the flexural capacity of reinforced UHPC beams.

2. Acquisition of the Database

The establishment of a database represents a fundamental stage in the initial process of machine learning, which involves the collection, organization and cleansing of data for model training. By conducting a comprehensive review of the published literature, an ultimate capacity database of reinforced UHPC specimens under bending loads is developed and summarized by integrating test results from diverse experimental studies in the present study (see

Table 1). The database comprises measured results of 339 UHPC-related specimens with varying design parameters sourced from 56 different experimental investigations [

12,

13,

18,

19,

20,

21,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. As previously mentioned, flexural behaviors of reinforced UHPC beams are highly dependent on the specimen geometry, the material properties of UHPC, the shape and volume fraction of steel fibers, and the amount and strength of steel rebars. In the database of

Table 1, the height (

H), width (

B) of a given cross-section and the length of shear span (

La) are considered to represent the geometrical size of the specimen. Additionally, the cylinder compressive strength of UHPC material (

ƒc) and mechanic characteristics of blended fibers including the shape, length (

Lf), diameter (

df) and volume fraction (

Vf) are involved. Furthermore, the yielding strength (

ƒy) and reinforcement ratio (

ρt) of steel rebars are also presented. A total of nine performance-sensitive parameters are incorporated as input variables into the established database, while the ultimate capacity of bending moment (

Mu) is selected as the output variable.

Table 2 provides detailed information on the statistical characteristic values of the parameters involved.

The presence of longitudinal tensile reinforcement in plain concrete beams has been proven to enhance the load-carrying capacity and stiffness of the structure. Accordingly, more than 95 percent of the flexural specimens in the database are equipped with longitudinal tensile reinforcement. Furthermore, the incorporation of steel fibers into UHPC matrix also improves its tensile strength and toughness. Consequently, 94.6% of the UHPC specimens selected in the database are blended with steel fibers, and the effects of various fiber characteristic parameters on their structural performance are explored. The inclusion of versatile steel fibers is particularly advantageous for enhancing the flexural capacity of UHPC structures. Specifically, the distribution percent of steel fiber shape of UHPC specimens included in the database is presented as follows: 79.5% of straight fibers, 2.5% of hooked-end fibers, 2.8% of corrugated fibers and 9.7% of hybrid fibers. Note that T is Steel fibers with different shapes. T is encoded as numbers to make it easier for models to process the data. Using numbers instead of words helps with calculations and analysis. Each number represents a different shape of fiber: 1 denotes straight fibers, 2 denotes corrugated fibers, 3 denotes hooked-end fibers, 4 denotes hybrid fibers, and 0 denotes specimens without steel fibers. In addition, 5.4% of the specimens without steel fibers are included, thus providing a basis for comparison in regard to the sensitivity of steel fibers. Overall, the database comprises a substantial number of experimental parameters, which may enhance the adaptability of machine learning models for training and evaluation.

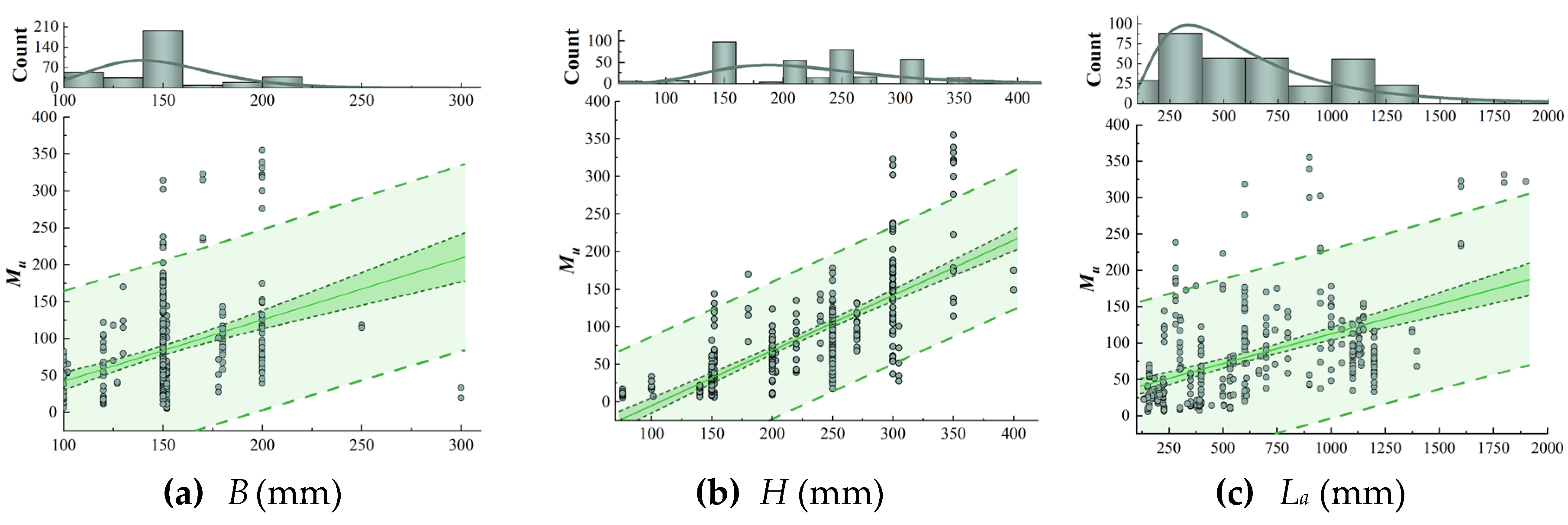

Figure 1 illustrates the frequency histograms of each parameter, as well as the dependence between the input variable and the target output variable of ultimate bending moment

Mu. It is evident that the estimation of flexural capacity

Mu for UHPC specimens is a highly intricate and challenging process. As shown in

Figure 1, an increase in the value of flexural capacity

Mu is observed with a growing parameter of

H,

B,

La,

ƒc,

ƒy, and

ρt. This trend is consistent with the fundamental principles of structural design and material properties. The regression curves for the parameters

H and

B in

Figure 1 display greater values of slopes, indicating that these parameters exert a more pronounced influence on flexural load-carrying capacity Mu. In contrast, the linear slopes of regression curves for the volume fraction

Vf and aspect ratio

Lf /df of steel fibers are approximately zero, making it challenging to assess their impact on

Mu. The relatively similar shapes of steel fibers employed in the bending tests may be responsible for the phenomenon, and additional research is required to confirm this hypothesis.

The application of simple linear regression is inadequate for clarifying the inherently complex relationship between ultimate bending moment

Mu and an individual input variable. As a result, finite element analysis methods and nonlinear numerical modeling have emerged as a significant development of prediction tools for structural evaluation, providing optimization solutions to an ever-increasing number of complicated structures. The purpose of this study is to estimate the flexural load-carrying capacity

Mu of reinforced UHPC specimens in the afore-mentioned database using several ML-based algorithms, including both traditional ML models and EL models. These methods are capable of accommodating a range of complexities, which are user-friendly to employ, and thus facilitate highly nonlinear modeling. This methodology of ML will enable the design of UHPC-based structures with reduced environmental impact and enhanced sustainability, as well as an improved accuracy and efficiency of performance prediction.

Table 1.

Summary of literature on flexural tests of UHPC beams.

Table 1.

Summary of literature on flexural tests of UHPC beams.

| Year |

Ref. |

Specimen number |

Design parameters |

Moment capacity |

Year |

Ref. |

Specimen number |

Design parameters |

Moment capacity Mu

|

| 2010 |

[18] |

10 |

ρt / fc |

83.3~131.7 |

2019 |

[48] |

5 |

Vf / fc |

118~154.5 |

| 2011 |

[49] |

7 |

H / Vf / fy /ρt |

26.6~222.9 |

2019 |

[50] |

1 |

ρt |

38.5 |

| 2011 |

[51] |

5 |

ρt / fy |

11.1~101 |

2019 |

[44] |

6 |

ρt / Vf / fy / fc |

16.7~33.9 |

| 2012 |

[52] |

10 |

ρt / fy |

32.5~144 |

2019 |

[53] |

9 |

ρt/ Vf / T / fc / (Lf /df)

|

40~88.3 |

| 2012 |

[54] |

5 |

ρt / fc |

27.6~100.8 |

2019 |

[55] |

4 |

ρt / fc |

233.6~323.2 |

| 2013 |

[56] |

4 |

Vf / fc |

23.7~29.1 |

2020 |

[57] |

9 |

ρt / Vf / fc |

53.8~116 |

| 2013 |

[58] |

4 |

ρt / (Lf /df)

|

122~178 |

2020 |

[59] |

6 |

ρt / Vf /g |

11.2~21.5 |

| 2013 |

[60] |

1 |

La |

320.4 |

2020 |

[61] |

3 |

Vf / fc |

126~152.5 |

| 2014 |

[17] |

2 |

ρt |

8.1~9.1 |

2020 |

[62] |

4 |

Vf / fc |

102~120 |

| 2015 |

[63] |

4 |

ρt / fy |

48.1~101.6 |

2020 |

[64] |

15 |

Vf / fy /ρt/ fc / La

|

7~22.1 |

| 2015 |

[47] |

5 |

ρt / (Lf /df) / T

|

39.3~56.1 |

2020 |

[65] |

4 |

Vf / fc |

35.7~38.7 |

| 2015 |

[66] |

5 |

ρt |

90.6~171.6 |

2021 |

[67] |

8 |

ρt / Vf / fy / fc |

37.1~314.5 |

| 2016 |

[21] |

4 |

ρt |

72.5~131 |

2021 |

[68] |

2 |

ρt |

58.1~61.9 |

| 2016 |

[69] |

1 |

ρt |

322 |

2021 |

[43] |

18 |

ρt |

9.1~80.2 |

| 2017 |

[70] |

6 |

Vf / fc |

15.6~19.1 |

2021 |

[71] |

12 |

ρt |

16.5~50.7 |

| 2017 |

[19] |

4 |

ρt / La |

33~118.3 |

2021 |

[72] |

6 |

Vf / fy / T/ La |

114~331.7 |

| 2017 |

[73] |

2 |

ρt / fy |

70.4~117.8 |

2021 |

[74] |

10 |

ρt / fc / La |

22.2~30.8 |

| 2017 |

[75] |

6 |

ρt / fc |

13~30.1 |

2021 |

[76] |

5 |

ρt |

28.6~82.5 |

| 2018 |

[77] |

8 |

ρt / fy |

43.3~135 |

2021 |

[78] |

13 |

ρt / Vf / T/ fc / fy |

50.8~98.7 |

| 2018 |

[20] |

8 |

ρt / Vf /T /(Lf /df)

|

37.5~134.4 |

2022 |

[6] |

8 |

ρt / T |

34.2~125.1 |

| 2018 |

[13] |

4 |

ρt / H |

6.1~12.5 |

2022 |

[79] |

4 |

ρt / fy |

40.1~58.5 |

| 2018 |

[46] |

2 |

ρt |

67.8~88.4 |

2022 |

[80] |

4 |

ρt / fy |

44.1~62 |

| 2018 |

[81] |

2 |

Vf |

148.9~174.9 |

2022 |

[42] |

4 |

ρt / fy |

79.9~170 |

| 2018 |

[45] |

14 |

ρt / fc / fy |

11.4~69.8 |

2023 |

[82] |

5 |

fy / ρt |

69~123.5 |

| 2018 |

[83] |

11 |

ρt/ Vf / fy / fc /La

|

125.5~238.3 |

2023 |

[15] |

5 |

ρt / Vf / fy / fc |

104~171.5 |

| 2018 |

[84] |

13 |

ρt |

29.9~122.2 |

2023 |

[16] |

6 |

ρt / Vf / fc |

52.8~143.4 |

| 2019 |

[12] |

5 |

ρt |

5.6~40.9 |

2023 |

[85] |

2 |

ρt |

95.1~111.6 |

| 2019 |

[86] |

4 |

ρt |

23.8~51.2 |

2023 |

[87] |

5 |

Vf / fc / ρt |

110.6~176.5 |

Table 2.

Statistical information of the parameters chosen.

Table 2.

Statistical information of the parameters chosen.

| Parameters |

Description |

Unit |

Mean |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Standard deviation |

Median |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

| H |

Height of cross section |

mm |

219.65 |

76 |

400 |

66.11 |

220 |

0.10 |

-0.70 |

| B |

Width of cross section |

mm |

148.81 |

100 |

300 |

31.09 |

150 |

0.75 |

2.73 |

| ρt |

Ratio of longitudinal reinforcement |

% |

2.68 |

0 |

16.4 |

2.23 |

1.9 |

1.91 |

5.66 |

| ƒу |

Yield strength of longitudinal reinforcement |

MPa |

477.57 |

0 |

1395 |

186.09 |

456 |

1.74 |

9.96 |

| ƒc |

Compressive strength |

MPa |

138.07 |

74.7 |

216 |

28.18 |

134.425 |

0.78 |

0.27 |

| Vƒ |

Volume fraction of steel fiber |

% |

1.81 |

0 |

4 |

0.72 |

2 |

-0.69 |

1.02 |

|

Lƒ/dƒ

|

Aspect ratio of steel fiber |

– |

64.30 |

0 |

150 |

17.97 |

65 |

-1.46 |

6.05 |

| La |

Shear span length |

mm |

627.72 |

135 |

1900 |

377.48 |

533.3 |

0.71 |

-0.28 |

| Mu |

Ultimate bending moment |

kN·m |

82.90 |

5.6 |

3552 |

67.03 |

68.18 |

1.66 |

3.42 |

Figure 1.

Dependance between the ultimate flexural capacity Mu and input variables.

Figure 1.

Dependance between the ultimate flexural capacity Mu and input variables.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Model Performance: A Comparison Across Diverse ML Algorithms

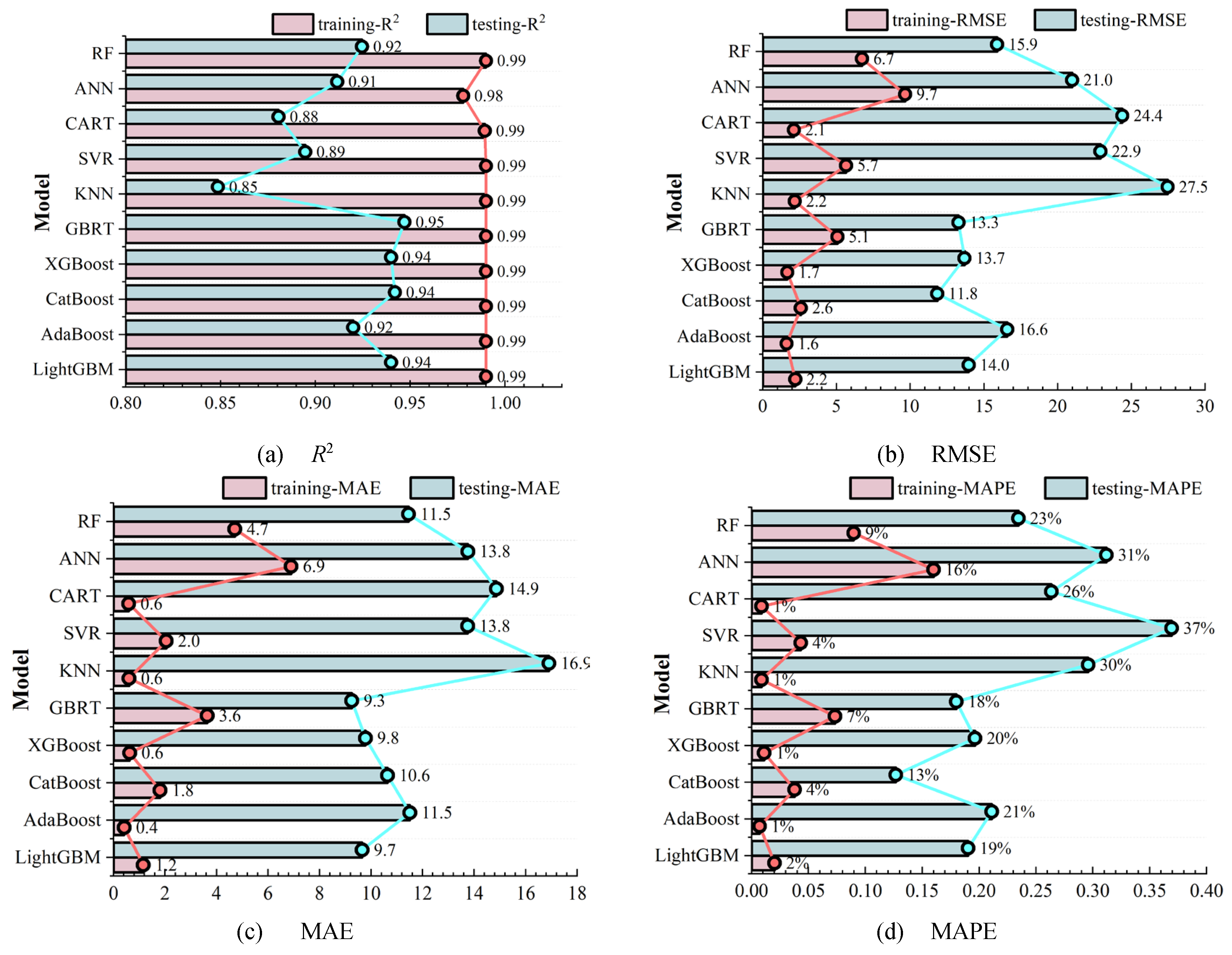

Ten different algorithms are employed to develop machine learning models based on the aforementioned database to predict the ultimate bending moment

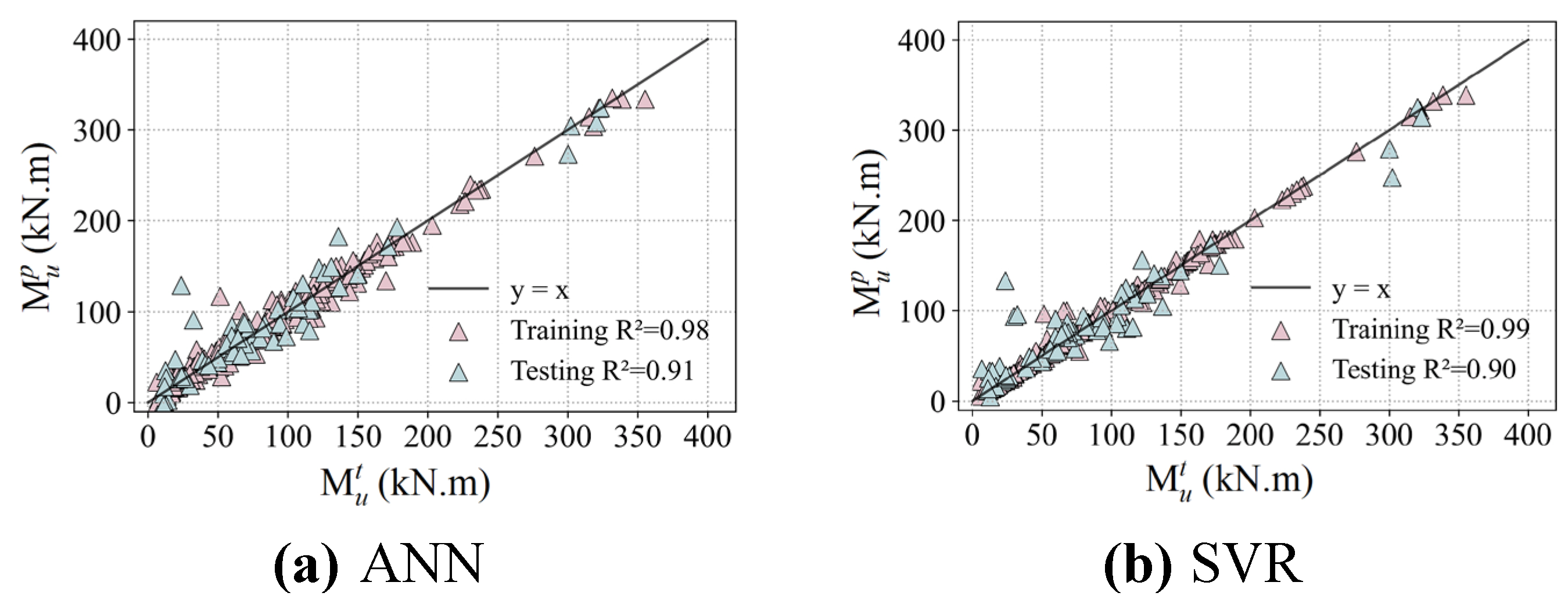

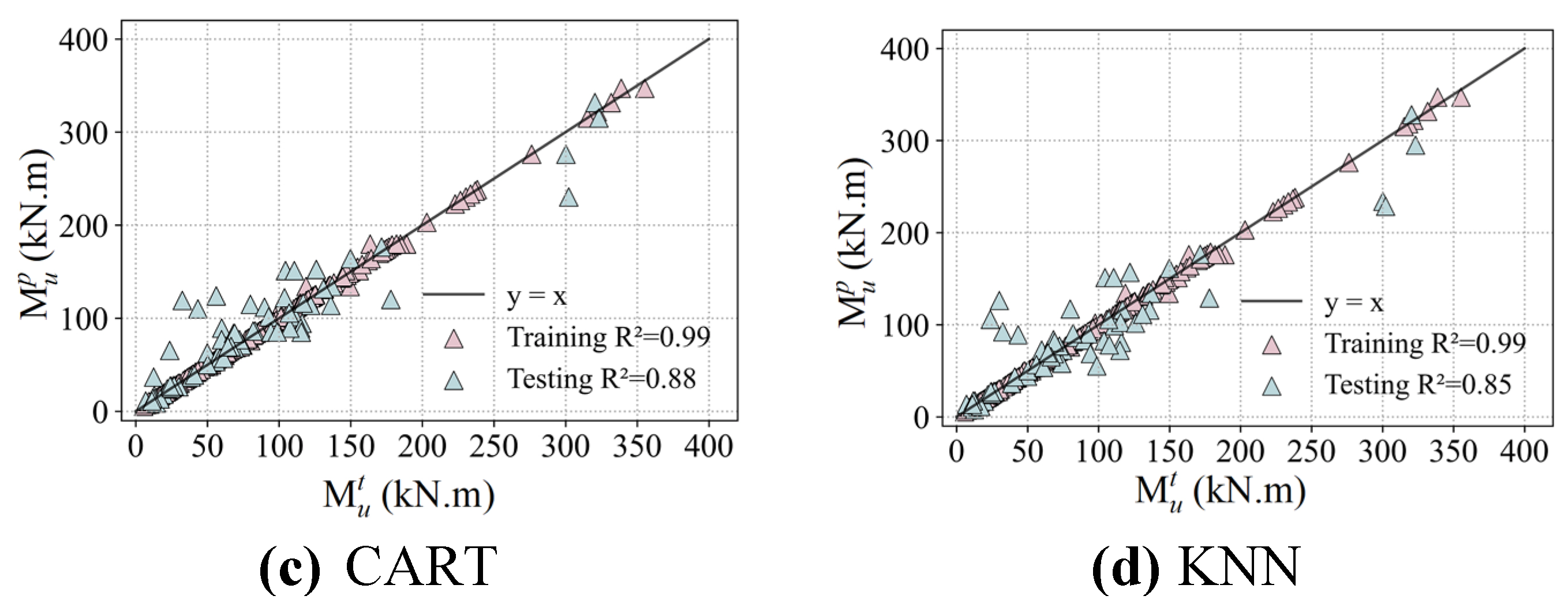

Mu of reinforced UHPC beams. The dataset has been divided into 80% for the training and 20% for the testing.

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 compare the predicted bending ultimate moments

Mup from the ML models, both traditional ML models and ensemble learning models respectively, with the corresponding tested results

Mut from the established database. The relationships between the predicted ultimate moments and the measured values follow a linear fitted law with a slope of 1.0. Detailed results of this comprehensive evaluation for the bending moment capacity of reinforced UHPC specimens using various ML-based models are presented in

Figure 15.

Figure 13.

Comparison of the predicted ultimate moments M up from the traditional machine learning models with the corresponding tested results M ut from the established database.

Figure 13.

Comparison of the predicted ultimate moments M up from the traditional machine learning models with the corresponding tested results M ut from the established database.

Figure 14.

Comparison of the predicted ultimate moments M up from the ensemble learning models with the corresponding tested results M ut from the established database.

Figure 14.

Comparison of the predicted ultimate moments M up from the ensemble learning models with the corresponding tested results M ut from the established database.

On the training set, the coefficient of determination R2 for all ML models except the ANN is greater than 0.99, highlighting their excellent fitting abilities. The ANN model still shows a commendable performance, although it has a slightly lower R2 value of 0.98. In terms of RMSE, the KNN, AdaBoost, CatBoost, and XGBoost models have relatively lower values compared to other ML models, indicating the minimized discrepancy between their predicted values and tested results, with an average error margin of approximately 2.0. This underlines their exceptional model accuracy in predicting flexural performance of reinforced UHPC beams. In contrast, higher RMSE values of 9.7 and 6.7are recorded for the ANN and GBRT models have been recorded, respectively. Despite these higher values, the model accuracy is still within an acceptable range.

Further analysis of the MAE reveals that the KNN, AdaBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM, and XGBoost models all maintain values below 2, indicating a negligible average deviation between the predicted and measured values, and thus a high degree of prediction accuracy. Moreover, the evaluation of MAPE clearly shows that the KNN, CART, AdaBoost, and XGBoost models keep the values below 1%, confirming their accurate prediction capabilities. Although the ANN model has a MAPE of 16%, indicating a reduced predictive accuracy—possibly affected by its network structure and hyperparametric settings—it nevertheless meets the fundamental predictive benchmarks.

Considering the testing set, the coefficients of determination R2 for the LightGBM, CatBoost, XGBoost, and GBRT models are all larger than 0.94, demonstrating their exceptional prediction potentials. This outstanding performance is primarily due to the inherent advantages of ensemble learning, which includes the reduction of bias and variance in predictions by combining multiple models, thereby enhancing their ability to generalize to new datasets. Conversely, the KNN model gives the lowest R2 value of 0.85 on the testing set. Its performance limitations may be related to its decision mechanism, which relies on nearest-neighbor voting or averaging. This may fail in the presence of high-dimensional data or uneven data distributions, where the concept of "nearest neighbor" may be somewhat indeterminate.

The KNN, ANN, SVR, CART and AdaBoost models present relatively high values when analyzing the three evaluation indicators of RMSE, MAE and MAPE, indicating a decrease in prediction accuracy on the testing set. The increased sensitivity of these models to the distribution of data features and the presence of noise may be responsible for this trend. In stark contrast, the GBRT and CatBoost models outperform on all three of these indicators, further underscoring the superior effectiveness of ensemble learning models in improving the accuracy of predictions. Specifically, GBRT and CatBoost develop their superiorities from the construction of multiple decision trees and the synthesis of the prediction insights of each tree to reduce potential errors inherent in singular models.

To summarize, the excellent performance of ensemble learning models such as LightGBM, CatBoost, XGBoost, and GBRT on the testing set is fundamentally related to the strategy of ensemble learning with model aggregation. Those approaches effectively reduce the bias and variance, while improving the generalization ability of the models. On the other hand, while the KNN model presents admirable results on the training set, its modest performance on the testing set highlights the importance of considering data characteristics and the compatibility of the logic of model decision with the given problem during model selection. Overall, the ten ML-based models evaluated are capable of accurately predicting the ultimate bending moment values Mu of reinforced UHPC beams, confirming the profound potentials of machine learning models to address challenging structural demands.

Figure 15.

Performance comparison of the ML-based models used.

Figure 15.

Performance comparison of the ML-based models used.

4.2. Data Subset Analysis for Model Performance and Stability

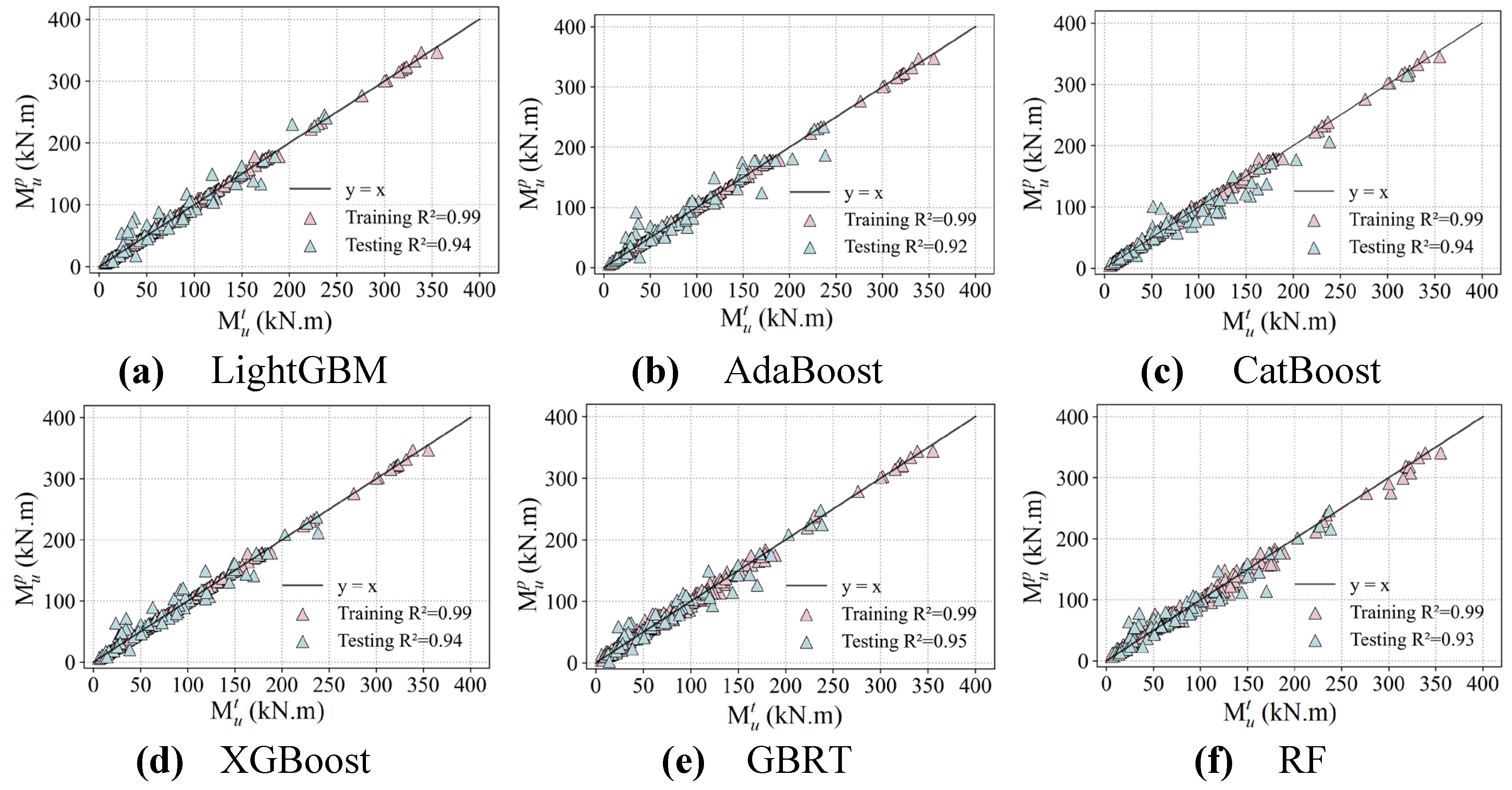

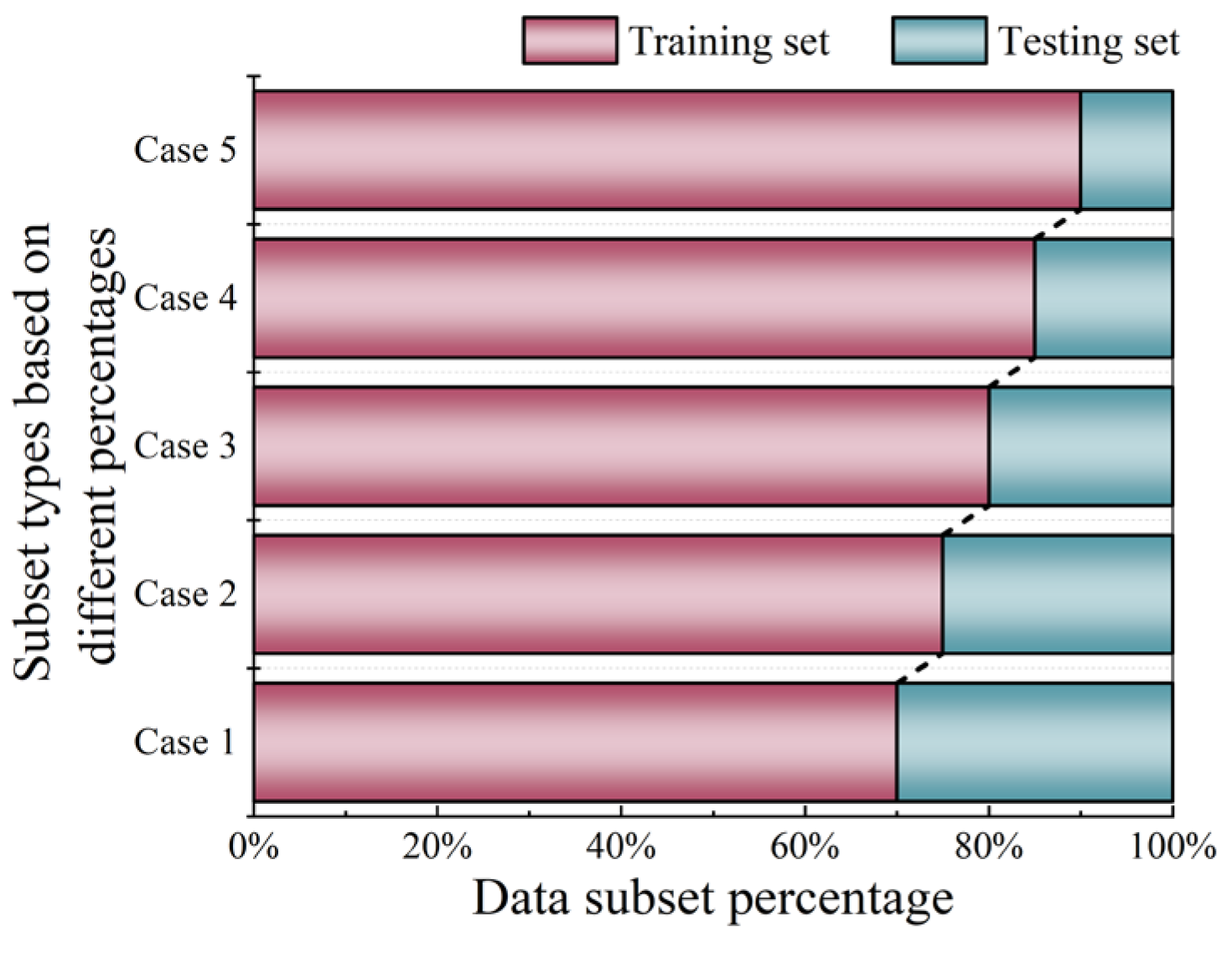

To systematically evaluate the qualities of ML-based models and database given, as well as to explore model stability, a methodical approach is taken by dividing the database previously established into subsets of varying sizes. This strategy makes it possible to examine model performance across a spectrum of dataset sizes, thereby providing insightful perspectives on how model performance varies with different dataset sizes. Based on findings from previous research and empirical evidence, five different cases of data subsets, as shown in Figure 16, have been identified for in-depth analysis.

Figure 16.

Identification of data subsets for in-depth analysis.

Figure 16.

Identification of data subsets for in-depth analysis.

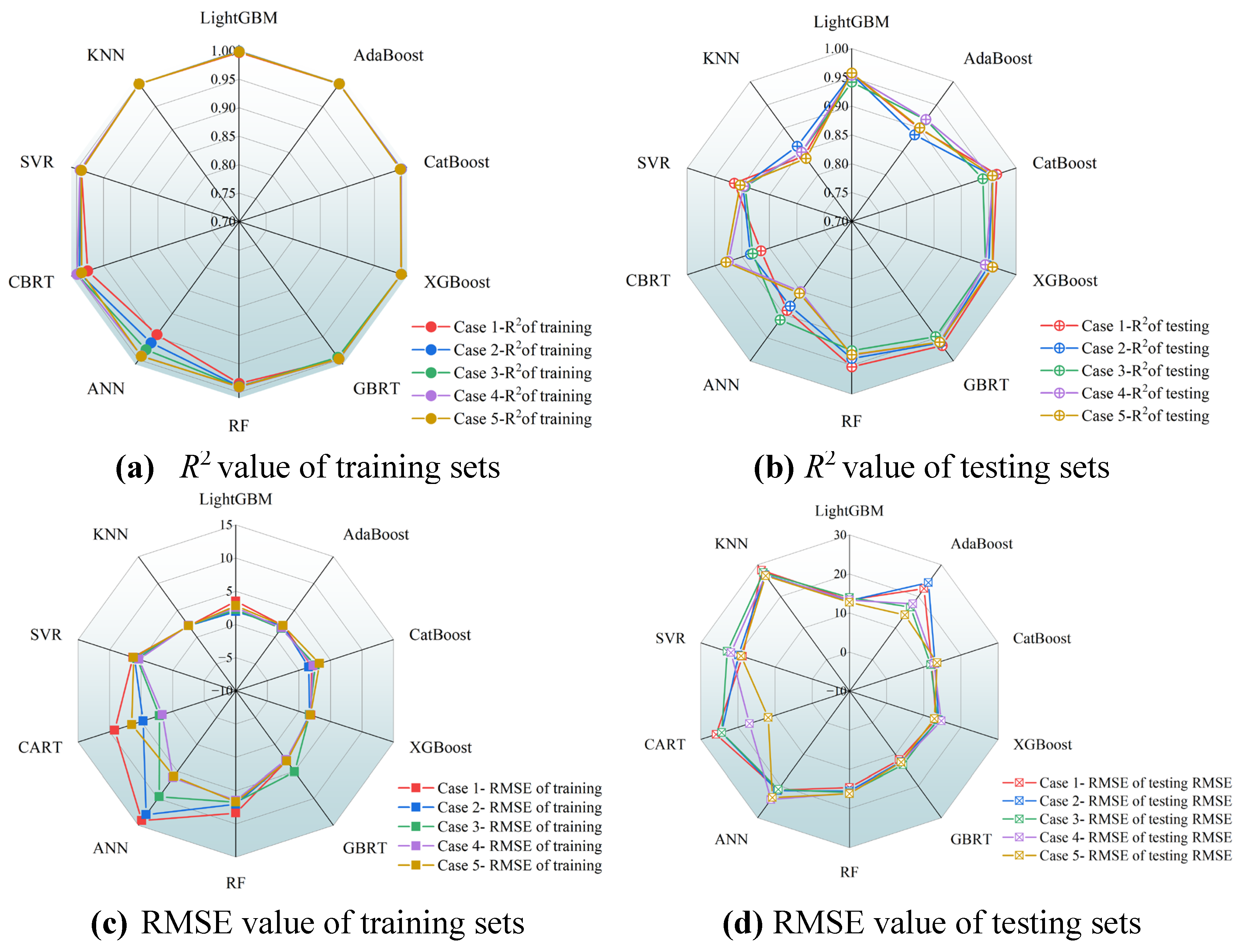

Figure 17 presents a comparative analysis of model performances with various cases of data subsets. An examination of the coefficient of determination R2 for all models reveals that, across different cases of data subsets, the R2 values associated with the training set are predominantly greater than 0.98, while those R2-values of the testing set are generally larger than 0.9. These results underscore the overall robust performance of ML models. Nevertheless, the ensemble learning models exhibit relatively superior performance compared to the counterparts of traditional ML models. Specifically, the CatBoost model achieves the highest R2-value of 0.97 on the testing set at the case 1, and reaches a maximum R2-value of 0.96for testing set at the case 2. For the third to the fifth case of data subsets, the R2-value of testing sets peak at 0.94, 0.96and 0.96 with the ensemble models of GBRT, CatBoost and GBRT, respectively.

This analysis highlights the superior performances of ensemble learning models over traditional ML models in most cases, and explains the variance in model effectiveness when dealing with data subsets of different divisions. The sustained high R2-values of ensemble learning models across a variety of data subset configurations can be attributed to their elaborate structures and algorithms, which are able to capture data correlations and patterns in a more effective way. As a result, the accuracy of predictions is improved. Furthermore, integrated models enhance the prediction accuracy by combining several weak learners or regressors. This strategy is especially beneficial when dealing with large and diverse data sets. On the contrary, due to the relatively simple algorithmic structure, traditional ML models may be unable to fully represent the intricacies of data relationships, which impacts to some extent their overall performance.

To conduct a thorough evaluation of model performance, three statistical performance indicators of ML models including RMSE, MAE and MAPE are discussed here. When evaluating the training set, a majority of ML models show exceptional and consistent proficiency across these performance indicators. Nonetheless, the KNN models demonstrate suboptimal performance under various cases of data subsets, especially for Case 1. It could be attributed to the fact that the KNN models encounter a deficit in training sample size within the data subset division for the case 1. This leads to an overfitting of training data with details and noise thereby decreasing their generalization abilities. Moreover, the MAE for most of the models is around 10, suggesting a mean absolute deviation of approximately 10 units between model predictions and measured results.

Having analyzed the model performance with statistical indicators, it becomes evident that CatBoost and GBRT models significantly outperform the traditional ML models. The KNN, AdaBoost, SVR, and ANN models display inferior performance in various data subset arrangements. For instance, in the fourth case of data subsets, the ANN model registers a dramatically high MAPE of 41%, suggesting an insufficient prediction accuracy. This may be due to the model not being trained on a sufficiently diverse or large dataset, which may have resulted in inadequate generalization to unseen data. However, in the fifth cases of data subsets, the MAPE values decrease to approximately 18%, revealing a reduction in the average percentage deviation between the prediction values and measured results to about 18%. The significant variation in MAPE values highlights the pronounced differences in the adaptability of diverse models to specific data subsets. It therefore emphasizes the need to consider the sensitivity and adaptability of a model to varying data subsets during the model selection and optimization process.

An in-depth evaluation of the ensemble learning models reveals that the second case is found to be the most effective and efficient database division strategy across all of data subset cases. To be more specific, 75% of the database is allocated to the training set, while the remaining 25% of the data served as the testing set. In contrast, the optimal data subset configuration for traditional ML models is identified in the case 3, where the data distribution percentages of the training set and testing set are 80% and 20%, respectively. The findings underscore the considerable influence of data division ratios on model effectiveness. Further investigation reveals that among ensemble learning algorithms, the CatBoost and GBRT models present a remarkable consistency with a varying data subset configuration. On the front of traditional ML models, the CART model stands out for its stability and robustness. Notably, the CatBoost model is distinguished by its superior division strategy of data subsets, considering both model efficiency and stability of data acquisition.

Figure 17.

The performance indicators of ML models are compared with measured data from experiments with different data subsets.

Figure 17.

The performance indicators of ML models are compared with measured data from experiments with different data subsets.

The insights gained from this analysis not only reveal the subtle differences in how each model will perform under different data subset distributions, but also provide critical guidance for future model selection and optimization efforts. The foregoing analysis highlights the critical importance of proper data acquisition in improving model performance. Specifically, in the context of ensemble learning models, the selection of an appropriate data subset configuration is of paramount importance for the realization of peak performance. Furthermore, the model stability plays a crucial role in determining how well it performs. Therefore, the effects of data configuration and model stability should be properly considered during the model selection and optimization phases to ensure optimal model functionality in real-world applications.

4.3. Comparison with Existing Empirical Equations

Given the increasing utilization of UHPC-based materials in civil engineering, a multitude of standards and guidelines have emerged worldwide to facilitate the design of UHPC structures [

36,

37,

38,

39]. The prevailing standards in the field, the French standard NF P 18-710 [

36] and Swiss recommendation SIA 2052 [

37], provide guidelines for the design of UHPC-based structures. However, these standards face limitations in terms of their practical application and accuracy precision. The French standard emphasizes strain-based failure criteria, requiring iterative calculations without explicitly defined formulas, whereas the Swiss recommendation simplifies compressive stress distribution and applies a reduction factor to tensile contributions. The existing empirical formulas are presented in

Table 6, with symbol definitions available in the referenced literature, respectively. Similarly, the US design guides of ACI 544.4R-18 [

38] and FHWA HIF-13-032 [

39], which are based on the equilibrium and strain compatibility, fail to fully capture the nonlinear behavior of UHPC element. The calculation model proposed by Li et al. [

40] is derived from experiments and incorporates UHPC’s tensile contribution with an assumption of uniform stress distribution, thereby reducing its applicability under varying reinforcement ratios. For reference, the key formulas for these empirical methods are presented in

Table 6. Despite the prevalence of existing empirical or code-based methods, numerous studies reveal that the empirical formulas provided for estimating the flexural capacity of reinforced UHPC beams frequently exhibit excessive conservatism, resulting in significant discrepancies between predicted values and experimental observations [

12,

13]. This study aims to demonstrate the superior predictability of the CatBoost model by comparing its model performance with several widely recognized models based on empirical formulas.

Table 6.

Calculation formulas of flexural capacity of reinforced UHPC-based beams.

Table 6.

Calculation formulas of flexural capacity of reinforced UHPC-based beams.

| Empirical equations |

Formula Expression |

| Swiss Recommendation SIA 2052 [37] |

|

| ACI 544.4R-18 [38] |

|

| FHWA HIF-13-032 [39] |

|

| Reference [40] |

|

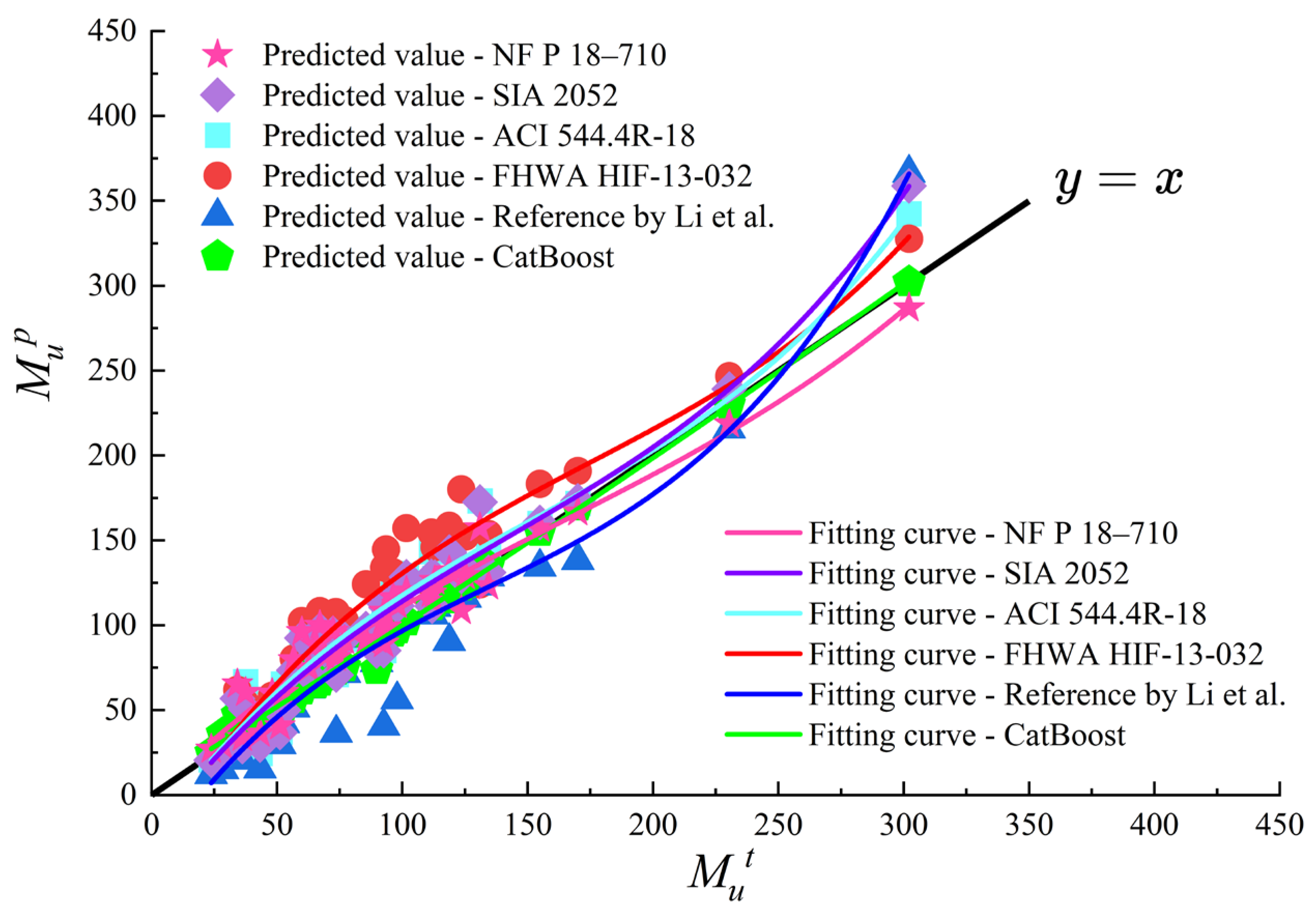

As shown in Table 7, the comparison results reveal that the CatBoost model significantly outperforms the five representative empirical formulas in predicting the flexural capacity of UHPC beams. Empirical design models such as the NF P 18–710 and SIA 2052 provide standardized approaches to the design of UHPC beam; however, they frequently rely on simplified assumptions about material behaviors, such as strain distributions or reduction factors, leading to conservative or inconsistent predictions. For instance, an examination of the calculation method proposed by Li et al. reveals an average predicted-to-measured flexural capacity ratio of 0.916, thus indicating a tendency to underestimate flexural capacity in practical applications. Conversely, the CatBoost model achieves a mean predicted-to-measured flexural capacity ratio of 1.022, the closest to 1, thereby signifying a higher degree of agreement with actual values.

Table 7.

Performance of the empirical method and the CatBoost model.

Table 7.

Performance of the empirical method and the CatBoost model.

| Models |

|

Quantitative performance |

| Min |

Max |

Mean |

R2

|

RMSE |

MAE |

MAPE |

| NF P 18–710 |

0.796 |

1.911 |

1.146 |

0.914 |

15.724 |

12.871 |

18.606% |

| SIA 2052 |

0.680 |

1.665 |

1.121 |

0.879 |

18.674 |

14.787 |

19.190% |

| ACI 544.4R-18 |

0.565 |

1.781 |

1.156 |

0.863 |

19.929 |

16.574 |

22.557% |

| FHWA HIF-13-032 |

0.775 |

1.809 |

1.257 |

0.711 |

28.923 |

24.251 |

29.534% |

| Reference [40] |

0.358 |

1.244 |

0.916 |

0.851 |

20.781 |

15.471 |

19.309% |

| CatBoost |

0.823 |

1.382 |

1.022 |

0.993 |

4.396 |

2.055 |

3.704% |

In terms of quantitative performance, the CatBoost model demonstrates superior performance, attaining an R² value of 0.993. This indicates its superior predictive accuracy and fitting capability compared to the existing empirical methods. For example, the recommendation SIA 2052 and the method presented by Li et al. exhibit R² values of 0.925 and 0.851, respectively; while the FHWA method a significantly lower R² value of 0.711. Furthermore, the CatBoost model demonstrates the lowest RMSE value of 4.396, MAE value of 2.055 and MAPE value of 3.704%, exhibiting a substantial improvement in performance compared to empirical methods such as the ACI 544 and FHWA models. These models exhibit significantly higher RMSE values of 19.929 and 28.923, respectively. These findings underscore the efficacy of the CatBoost model in minimizing prediction errors and ensuring consistent accuracy across diverse datasets.

As illustrated in Figure 18 the predicted data points with the CatBoost model are closely distributed around the baseline , suggesting that the model demonstrates reliable and robust performance. The polynomial fitting curve (green) of the CatBoost model exhibits a strong alignment with the observed values and provides a reliable representation of the underlying data. In contrast, traditional empirical models demonstrate notable deficiencies. Specifically, the ACI 544 and the FHWA method exhibit substantial deviations between their curves and the observed values, with a greater degree of scattered data points. It is important to note that the FHWA method, with a high RMSE of 28.923, experiences significant challenges in accurately capturing the complex mechanical behavior of UHPC. Similarly, while the NFP 18–710 model exhibits marginal enhancements, its computational process is complex and its applicability limited. The ACI 544 model, conversely, excessively simplifies the tensile zone contribution of steel fiber-reinforced concrete, resulting in significant prediction errors. These limitations further underscore the advantages of data-driven approaches.

Overall, the CatBoost model demonstrates superior performance in terms of predictive accuracy in comparison to empirical methods. Its enhanced applicability and adaptability are particularly notable, as it is capable of incorporating complex feature interactions and producing highly reliable results, which makes it an invaluable tool for practical engineering applications. The employment of data-driven methodologies by the CatBoost model presents a promising alternative to existing empirical methods, thereby paving the way for enhanced accuracy and efficiency in the field of UHPC structural design.

Figure 18.

Comparison between the empirical methods and the CatBoost model.

Figure 18.

Comparison between the empirical methods and the CatBoost model.

5. Model Interpretation

Advanced machine learning models, such as deep learning, are often considered "black boxes" because of the complexity and nonlinear nature of the models involved that makes it difficult to interpret their decision-making processes. The lack of transparency can have a negative impact on confidence in model predictions.

While techniques such as Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) and Interpretive Decision Trees provide a degree of interpretability, they are limited. A Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) has a potential to address these challenges by clarifying the contribution of features to model predictions. SHAP has been widely adopted for model interpretation, since it enhances transparency and credibility through consistency, local interpretability and model independence [

35,

41,

101,

102]. The explanatory model of SHAP, g(a′), is defined as

where ф0 is the baseline value of the model, usually the average of all sample predictions; фz is the SHAP value of the feature z, which indicates the contribution of the feature z to the prediction; a′z is a binary indicator for the feature z, indicating whether feature z is in the explanatory model.

5.1. Analysis of Feature Importance Using SHAP

In exploratory analysis of ML models, reliance on the SHAP interpretation for a single model alone may not adequately capture the delicate effects of features on predictions. This limitation arises from the varying dependencies and interactions that different models have with the same set of characteristic parameters. To gain a deeper and more accurate understanding of feature significance and their influence on predictions, it is essential to perform a SHAP analysis with multiple models.

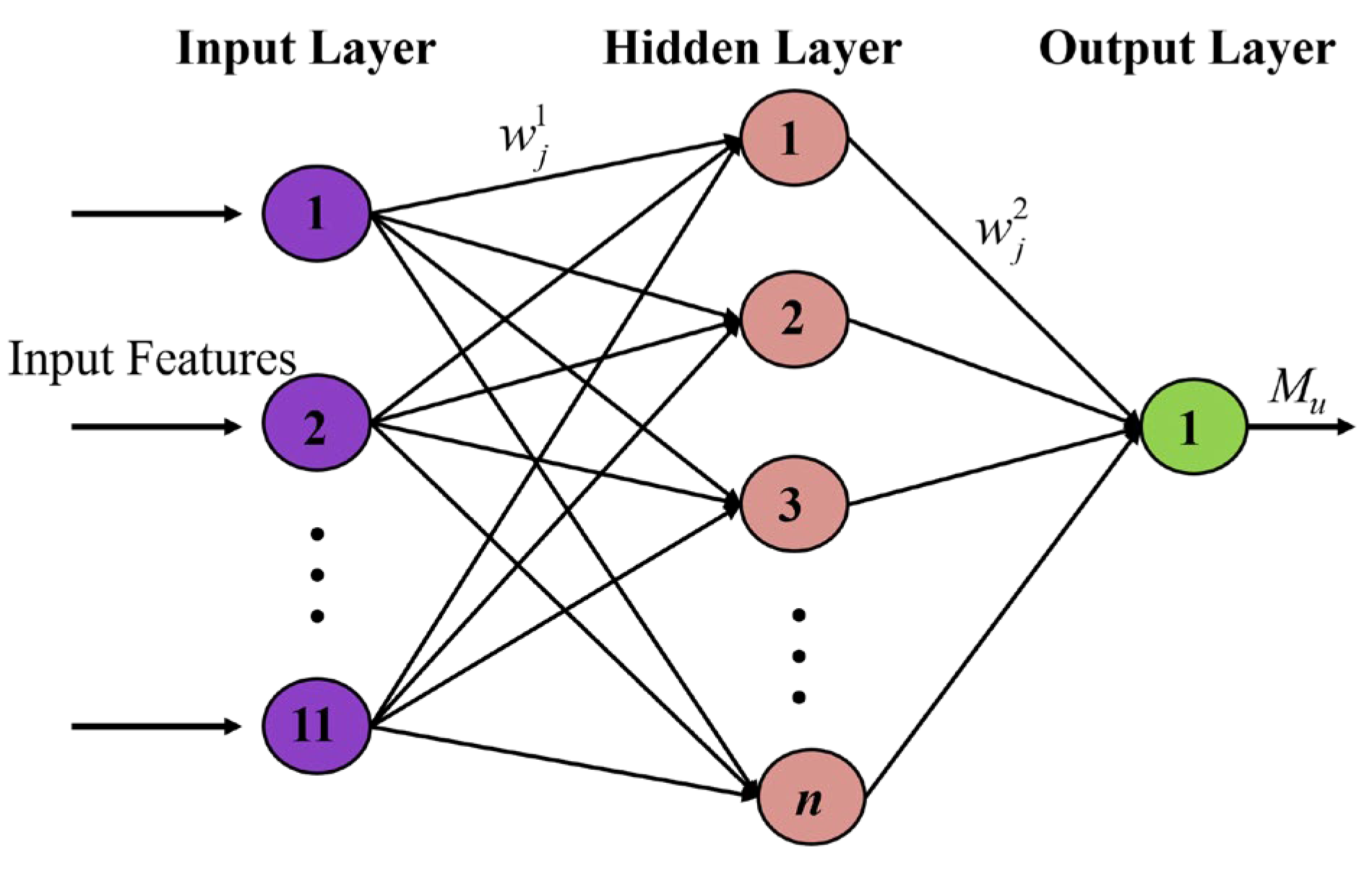

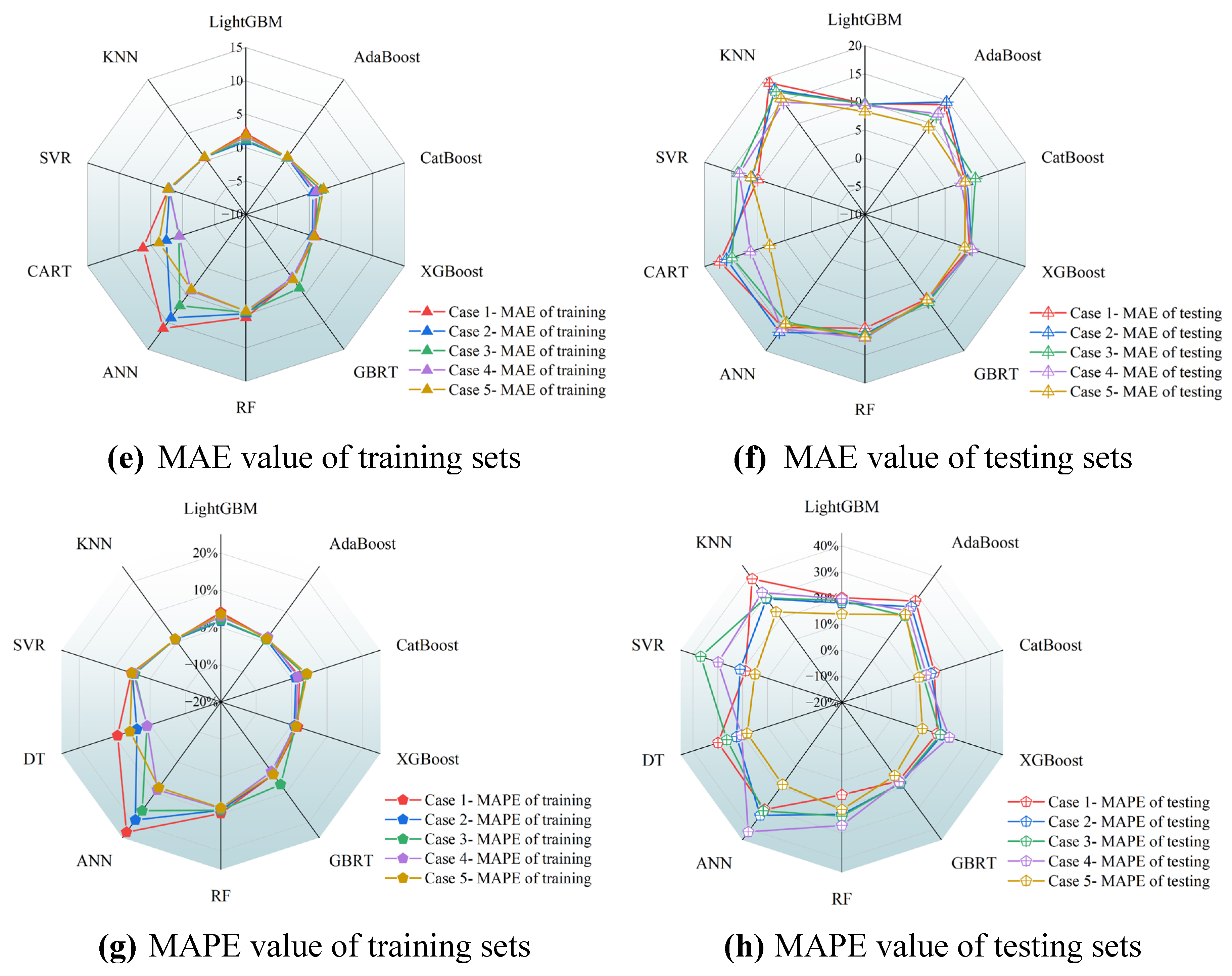

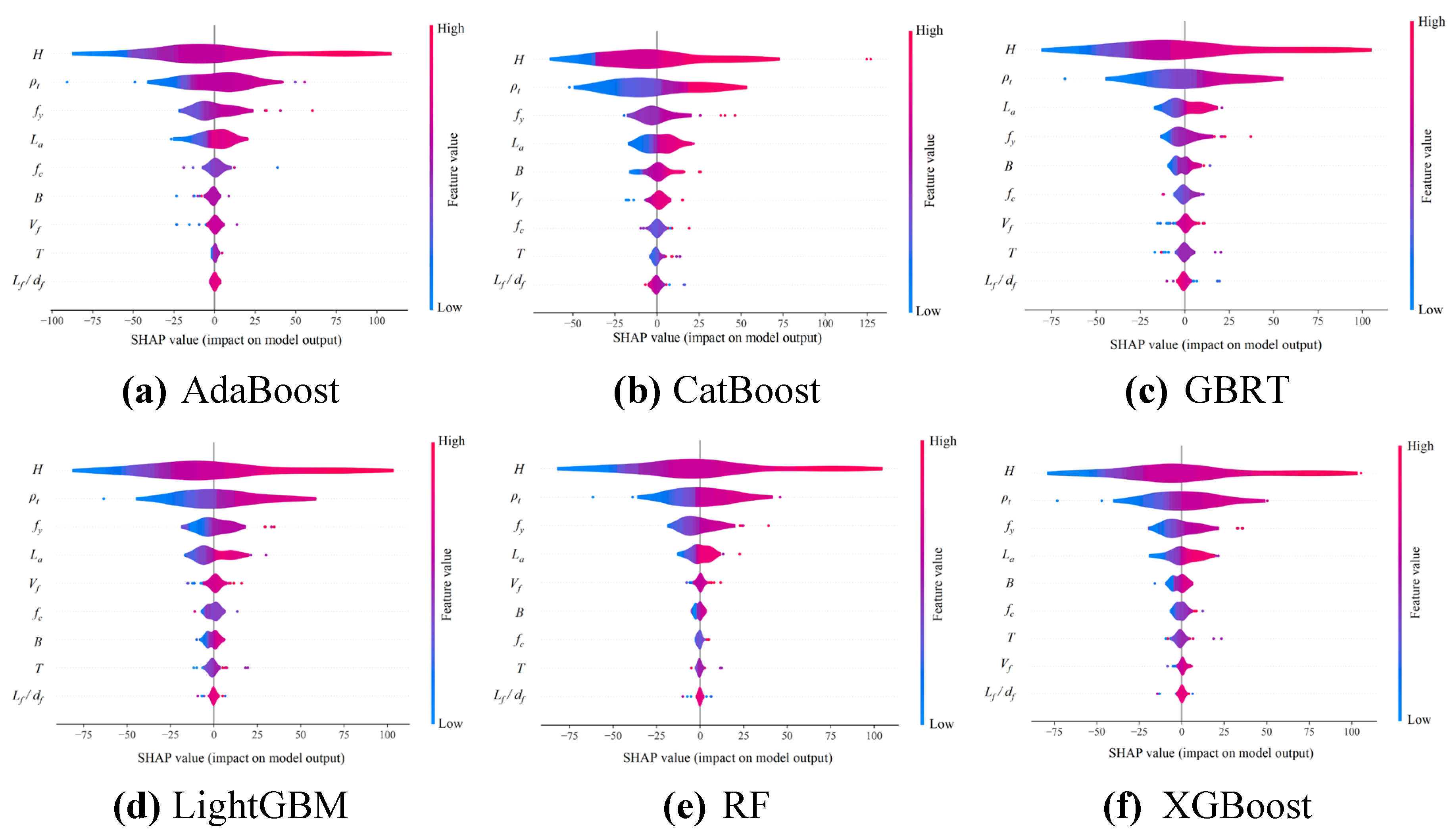

Taking advantages of the global interpretability and powerful visualization capabilities offered by SHAP, a global feature importance analysis across six ensemble learning models is conducted. To illustrate the impact and importance of each feature on model output, Figure 19 presents the SHAP values for each ensemble learning model. In this figure, the horizontal axis displays the SHAP values, which indicates the extent to which each feature affects the prediction accuracy of the model. Meanwhile, the vertical axis enumerates the features in order of importance, with a color gradient from blue to red representing the progression from lower to higher feature values. It is evident to note that there are marked discrepancies in how features rank in importance and the direction in which they affect different models.

From Figure 19, the SHAP analysis for five models highlights the reinforcement ratio of longitudinal rebars ρt, the yielding strength of reinforcement fy, and the beam height H as the most important features, each of which contributes positively to the prediction results. In contrast, the GBRT model emphasizes the beam height H, reinforcement ratio ρt, and the length of shear span La as critical, demonstrating the inherent variability in feature prioritization between different models. These observations highlight the critical role of longitudinal reinforcement ratio ρt in predicting the ultimate bending moment Mu of reinforced UHPC beams, consistent with its recognized importance in the enhancement of steel rebars for reinforced concrete beams. Despite of a limited tensile strength of concrete-based materials, the longitudinal reinforcements in UHPC beams overcome the limitation by providing essential tensile strength to negative bending moments. The steel reinforcement in UHPC beams effectively carries the tensile load during bending, while the lower section of the beam is longitudinally under tension.

Moreover, several features such as the beam height H, and the beam width B—attribute representatives of the cross-sectional properties of UHPC beams—are highlighted. This emphasizes the critical role of cross-sectional characteristics in determining the flexural performance UHPC beams. The feature B is highly significant in the CatBoost, XGBoost, and GBRT models, but it is of much less importance in the LightGBM model, where its influence is ranked remarkably lower. This discrepancy suggests that feature importance ratings vary due to the unique mechanisms that each model utilizes to process features. For the six ensemble learning models, the yielding strength of reinforcement fy and the length of shear span La show more consistency in both importance and direction of impact. The SHAP values for these features are more concentrated, which is an indication of a more uniform influence on the prediction results. It is noteworthy that the yielding strength of reinforcement fy is recognized in the classical formulations, while the influence of shear span length La is absent in the design specifications. This discrepancy indicates that traditional empirical formulas may not fully capture the complexity associated with flexural capacity prediction Mu for reinforced UHPC beams.

Figure 19.

SHAP summary plots of the six ensemble learning models.

Figure 19.

SHAP summary plots of the six ensemble learning models.

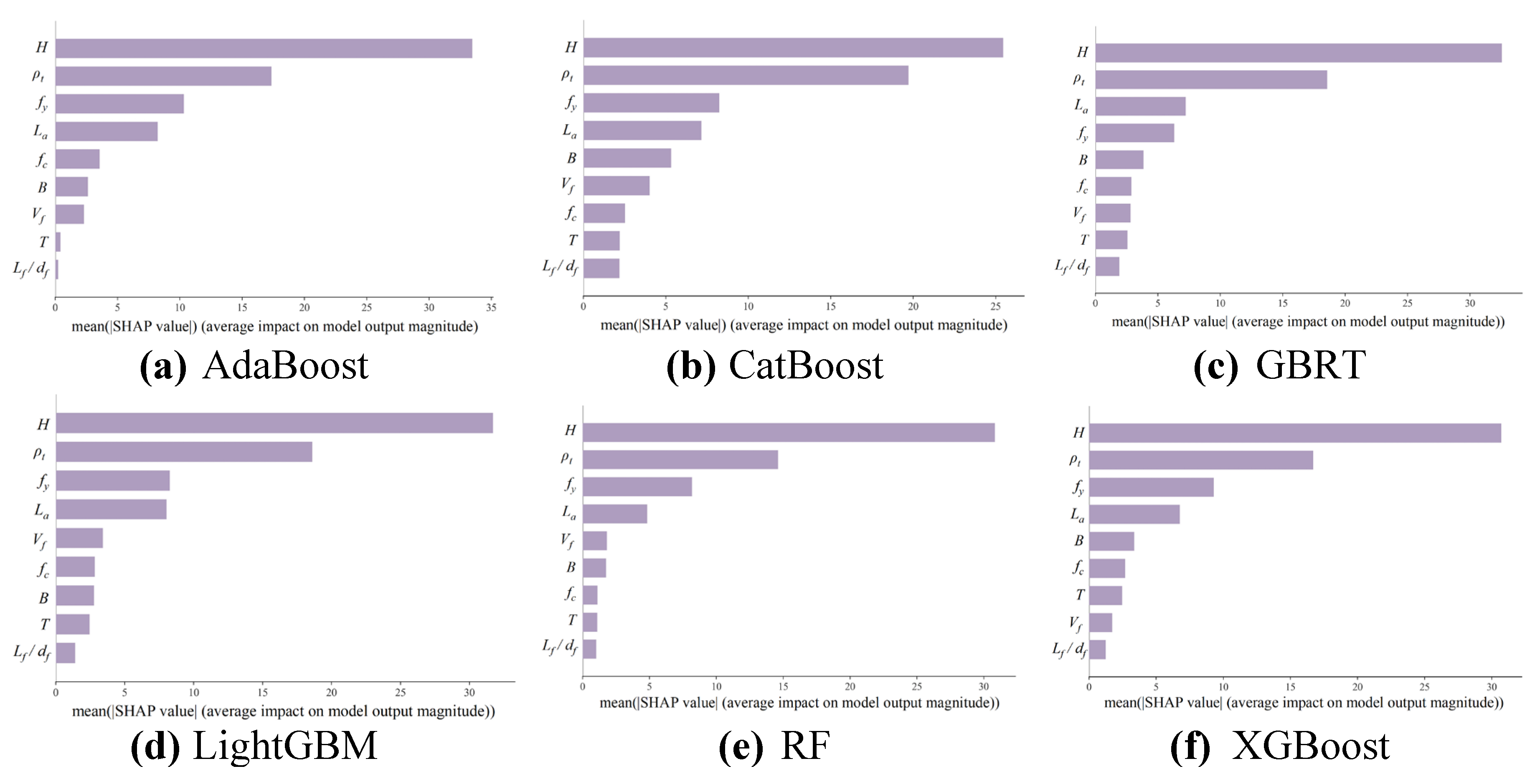

Figure 20 presents the SHAP bar plot for the six ensemble learning models, illustrating the average impact magnitude of each feature on the predictions of those models. The CatBoost model features a relatively more uniform distribution of SHAP values across all features, suggesting a balanced consideration in the decision-making process without excessive dependence on specific features. This equilibrium potentially contributes to the superior performance and stability of the model, explaining its consistent performance across various data subsets among ten ML models analyzed. In contrast, the SHAP bar plots for other ensemble learning models reveal that some features have significantly higher SHAP values, indicating a stronger reliance on particular features, such as in the AdaBoost, RF, and XGBoost models. This dependency might result in fluctuating model performance across different data subsets.

While an interpretation of SHAP values for a single model may not fully delve into the importance and impact of features on predictions, the analysis of SHAP interpretations across multiple models provides a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of feature importance and interactions. This approach facilitates model selection, optimization, and interpretation analysis with a solid theoretical foundation and practical insights.

The purpose of key feature interpretation is to clarify the explanation of how the importance of features varies across different models and how SHAP analysis can provide deeper insights into model behavior and feature impact, thereby supporting more informed decision making in predictive modelling.

Figure 20.

Feature importance of the six ensemble learning models based on SHAP.

Figure 20.

Feature importance of the six ensemble learning models based on SHAP.

5.2. Key Feature Interpretation

The improvement of the transparency and interpretability of ML models is essential for the understanding of their decision processes. To assess the influence of features in the CatBoost model, visualization techniques are applied. A uniform distribution of SHAP values across features suggests a balanced influence, which leads to a focused analysis of the top five most influential features. This approach highlights the key features that drive the predictions of the model [

101]. Feature normalization, achieved by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation, is used to ensure uniform scaling, stabilize the model and accelerate convergence.

where X is the raw data, μ is the mean, σ is the standard deviation, andis the normalized data. The objective of this normalization process is to neutralize the scaling differences among various features, thereby enhancing the stability of the model during its training phase and allowing for faster convergence of the algorithm.

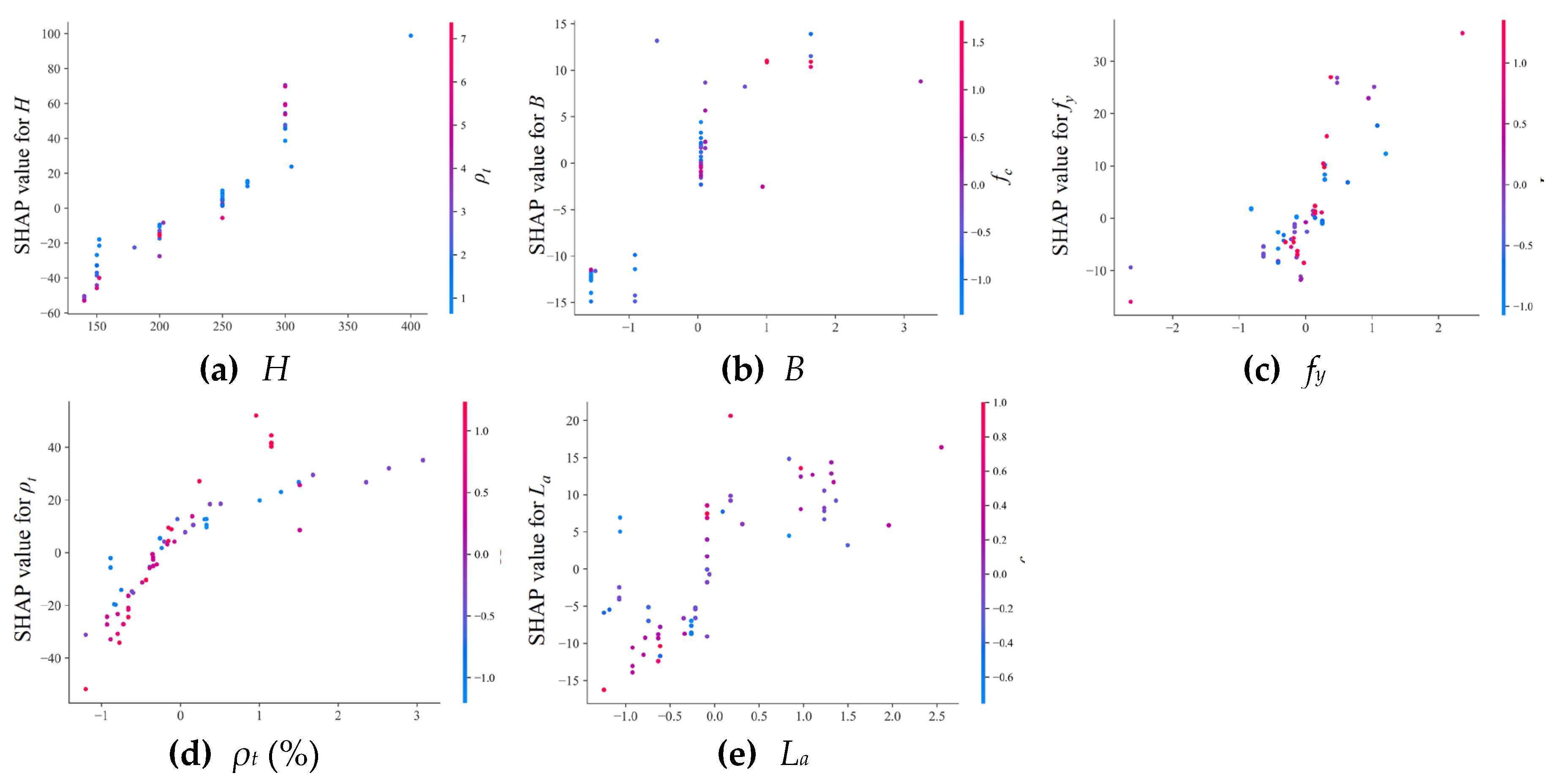

The normalized SHAP values of the CatBoost model are represented in Figure 21. The analysis of normalized SHAP value reveals a prevailing trend that increases in the eigenvalues of H, ρt, B, and La are associated with increases in the normalized SHAP values. This pattern suggests that increased eigenvalues of these features substantially increase flexural ultimate capacity Mu, as reflected in the greater SHAP values. This notable positive correlation, particularly evident for parameters of H, ρt, B, and La, highlights their considerable influence on Mu. Nevertheless, the feature fy shows a clearly nonlinear relationship with flexural ultimate capacity Mu. It is attributed to the ability of the CatBoost model to capture the intricate interactions and nonlinear dynamics between the features. In the context of reinforced concrete beams, the steel reinforcement and the surrounding concrete work together to resist bending moments. The nonlinear influence of fy is partly due to the complex stress-strain behavior of concrete, in particular its tendency to crack in tension and its ultimate compressive strength limit. An observed increase in the variability of normalized SHAP values for the yielding strength of reinforcement fy deviating from zero—especially towards positive values—suggests a pronounced influence of reinforcement strength fy on flexural ultimate capacity Mu in these regions. Deviating from a straightforward linear relationship, the contribution of fy in increasing flexural ultimate capacity Mu is further evaluated by the distribution and depth of steel reinforcements within the concrete cross-section. As such, the feature of yielding strength of reinforcement fy, especially in certain regions, deserves a more in-depth analysis.

An interesting observation from Figure 21(d) is the prevalence of more red dots at higher values of ρt, which suggests a simultaneous increase in H values in these areas, potentially amplifying their influence on flexural ultimate capacity Mu. Thus, when evaluating the effect of ρt on flexural ultimate capacity Mu, it is crucial to consider the interactions with other features. The increases in the values of La, and H are significantly beneficial to flexural ultimate capacity Mu, while the effect of fy is nonlinear and more pronounced in certain regions. Furthermore, the interaction of H with high values of ρt deserves special attention. These findings allow for a deeper understanding of how each feature contributes to Mu, thus laying a foundation for more accurate model optimization and feature engineering strategies.

Figure 21.

SHAP dependency plots for 5 critical features in the CatBoost model.

Figure 21.

SHAP dependency plots for 5 critical features in the CatBoost model.