1. Introduction

Epilepsy stands as one of the most common neurological disorders globally, characterized by recurrent and unprovoked seizures affecting approximately 50 million people worldwide [

1]. These seizures are manifestations of excessive and abnormal neuronal activity in the cortex of the brain [

2]. The impact of epilepsy extends beyond the physical and neurological—social stigmatization, psychological stress, and increased mortality rates are significant, particularly in countries with limited resources. Although pharmacological advances have been made, the available treatments are often marred by suboptimal efficacy and adverse effects, leading to an ongoing search for more effective and safer therapeutic alternatives [

3,

4].

Current antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) operate primarily through modulation of ion channels, enhancement of inhibitory mechanisms, or reduction of excitatory transmissions. Commonly used AEDs include sodium valproate, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine, among others [

5]. While these medications are effective in managing seizure activities in many patients, approximately 30% of the epileptic population remains refractory to these treatments. Additionally, the side effects associated with these drugs—ranging from mild dizziness and fatigue to severe behavioral changes, teratogenicity, and hypersensitivity reactions—complicate long-term management and impact patient quality of life [

6].

Given these challenges, there is substantial interest in exploring alternative treatments, including the use of medicinal plants. Phytomedicine offers a vast array of secondary metabolites with potential therapeutic effects. Historical and ethnobotanical leads have often guided the discovery of new drugs, with several modern medications developed from plant-based sources. For instance, galantamine, originally derived from snowdrop flowers, is now widely used in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. This underscores the potential of plant extracts and isolated natural products in contributing to the pharmacopeia of neurological disorders [

7].

Verbesina persicifolia, a perennial herb found in tropical and subtropical regions, is traditionally used in herbal medicine for its diverse pharmacological properties. Reports from various ethnomedical sources highlight its use in treating wounds, inflammations, and as a natural remedy for nervous system disorders. Preliminary studies have suggested that extracts from this plant possess anxiolytic, antidepressant, and potential anticonvulsant activities. [

8,

9,

10,

11] These activities are thought to be mediated through the modulation of neurotransmitter pathways, similar to many conventional AEDs. However, the specific components responsible for these effects and their mechanisms of action remain largely unexplored.

The zebrafish (

Danio rerio) model has emerged as a valuable tool for neurological research, including the study of epilepsy [

12,

13,

14]. The biological and physiological properties of zebrafish neurotransmitter systems show significant homology to humans, making them ideal for studying genetic and pharmacological treatments. Moreover, the optical transparency of zebrafish larvae allows for real-time monitoring of drug effects on brain activity and behavior. The PTZ-induced seizure model in zebrafish is particularly well-established, mimicking the kindling observed in human epilepsy. PTZ, a GABA receptor antagonist, induces hyperactivity followed by clonic-like seizure activity, providing a measurable phenotype that can be used to assess the efficacy of anticonvulsant agents [

15,

16,

17].

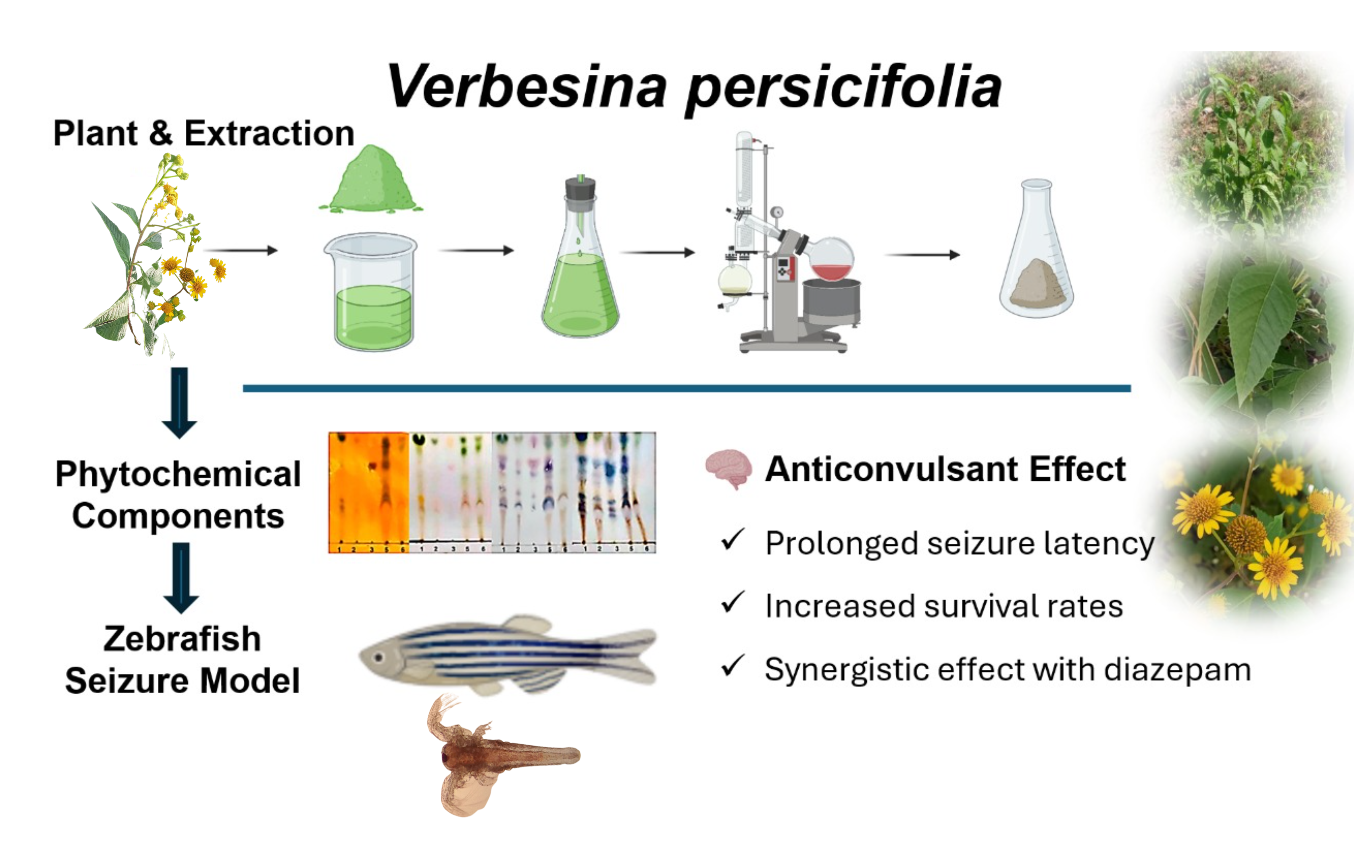

This research focuses on evaluating the anticonvulsant properties of methanolic extracts of

V. persicifolia in a PTZ-induced seizure model in zebrafish. By detailing the delay in onset of seizure-like behavior and survival rates, the study aims to establish a potential therapeutic profile for the plant extracts. Additionally, through phytochemical analysis, the research seeks to identify the active constituents within the extracts, offering insights into their mechanisms of action and potential for development into new AEDs [

18,

19]. The investigation not only broadens the understanding of

V. persicifolia's pharmacological effects but also contributes to the broader quest for more effective and tolerable treatments for epilepsy.

This research bridges traditional herbal medicine and modern pharmacological methodologies to explore innovative solutions for epilepsy, a condition desperately in need of more diverse and accessible treatment options. By harnessing the potential of V. persicifolia, the study adds to the growing body of evidence supporting the use of medicinal plants in developing novel therapeutic agents for managing complex neurological disorders.

2. Results

The extraction of Verbesina persicifolia leaves yielded hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, and methanol fractions, which were analyzed for phytochemical composition, toxicity, and anticonvulsant activity. Bioactive compounds were identified in the extracts, and toxicity evaluation in Artemia salina was conducted alongside anticonvulsant assessment in a PTZ-induced zebrafish seizure model.

2.1. Extraction and Phytochemical Analysis of V. persicifolia

The phytochemical composition of

Verbesina persicifolia leaf extracts was analyzed across three consecutive years (2019, 2020, and 2021). Phytochemical screening of methanolic extracts confirmed the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, and steroids in all years, while saponins, tannins, quinones, and triterpenoids exhibited variability between collection years (

Table 1). These differences may be influenced by environmental factors affecting secondary metabolite biosynthesis (

Supporting Information, Figure S7 and S8).

To complement our findings, previous phytochemical studies on

V. persicifolia and related

Verbesina species have identified eudesmane sesquiterpenes, terpenoids, flavonoids, alkaloids, and essential oils.

Table 2 summarizes relevant secondary metabolites previously reported in gender

Verbesina and

V. persicifolia [

11,

20,

21].

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed to confirm the presence of these metabolites in the hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, and methanol extracts. The analysis revealed distinct bands corresponding to flavonoids, phenols, steroids, and alkaloids, with optimal separation achieved using dichloromethane/methanol (95:5) for non-polar fractions and ethyl acetate/methanol (8:2) for polar fractions. However, due to the low quality of TLC images, these figures have been provided as Supporting Information (

Figures S1 and S2).

The consistent presence of flavonoids, alkaloids, and steroids in V. persicifolia across multiple years, along with previously reported eudesmane derivatives and essential oils, confirms a stable phytochemical profile. These results provide a strong basis for subsequent pharmacological evaluations.

2.2. Toxicological Assessment in Artemia salina

The toxicity of V. persicifolia extracts was evaluated using the median lethal concentration (LC50) values, classified according to Clarkson’s toxicity scale. Extracts with LC50 > 1 mg/mL were considered non-toxic, while those within 0.5–1 mg/mL, 0.1–0.5 mg/mL, and <0.1 mg/mL were classified as low, moderate, and high toxicity, respectively.

Methanolic partitions exhibited low to non-toxic profiles, with hexane and ethyl acetate fractions showing low toxicity (LC

50 values of 0.499 mg/mL and 0.633 mg/mL, respectively), while dichloromethane and methanol fractions were non-toxic (LC

50 > 1 mg/mL) (

Table 3).

In contrast, sequentially extracted fractions demonstrated increased toxicity, particularly in the hexane (LC

50 = 0.073 mg/mL, high toxicity) and dichloromethane (LC

50 = 0.105 mg/mL, moderate toxicity) extracts. Both ethyl acetate and methanol sequential extracts exhibited moderate toxicity (LC

50 = 0.421 mg/mL) (

Table 3).

These findings confirm that methanolic partitions of V. persicifolia demonstrate a generally safe profile, whereas sequentially extracted fractions exhibit greater toxicity, particularly in non-polar extracts.

2.3. Anticonvulsant Activity in Zebrafish Model

The anticonvulsant potential of V. persicifolia extracts was assessed in PTZ-induced seizures in zebrafish. Key parameters measured included Latency IV, Whirlpool Latency, Posture Loss Latency, and survival rates. Extracts were evaluated using partition and sequential extraction methods, with the hexane fraction also tested in combination with diazepam and sodium valproate.

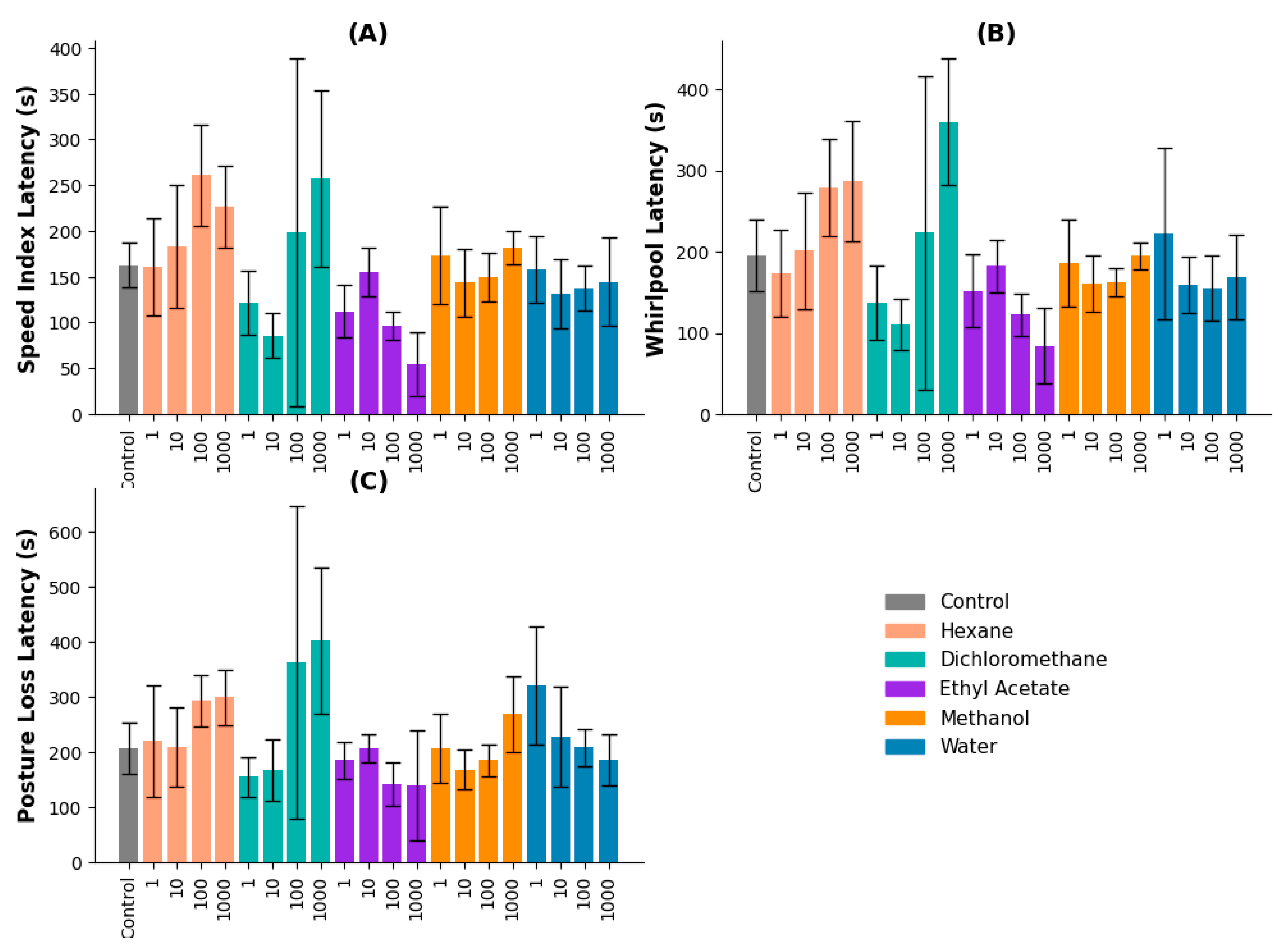

2.3.1. Partition Method

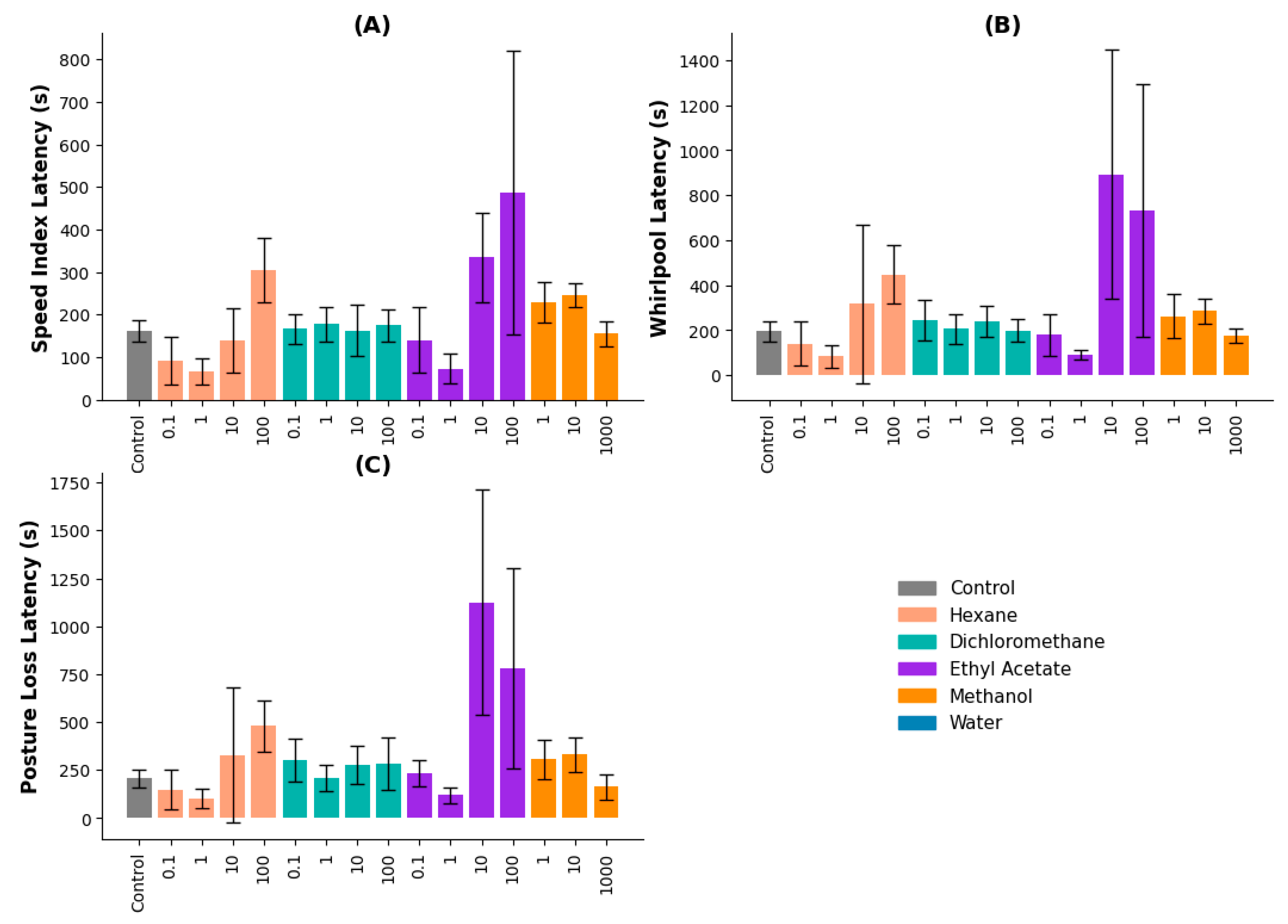

The partition method was used to investigate the anticonvulsant effects of different solvent extracts (hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, methanol, and water).

Speed Index Latency: The hexane and dichloromethane extracts showed increased latency compared to the control group. The hexane extract at 100 µg/mL had the longest latency (260.8 seconds), although it was not statistically significant (

p = 0.374). The dichloromethane extract at 1000 µg/mL significantly differed from lower concentrations (

p ≤ 0.05 for 10 and 1 µg/mL) (

Figure 1A).

Whirlpool Latency: The dichloromethane extract at 1000 µg/mL significantly prolonged whirlpool latency compared to the control (

p = 0.003). Higher concentrations (100 and 1000 µg/mL) resulted in increased latency compared to 1 µg/mL (

p ≤ 0.05) (

Figure 1B).

Posture Loss Latency: The dichloromethane extract at 1000 µg/mL had the highest latency (402.33 seconds), significantly differing from the control and lower concentrations (

p ≤ 0.05). However, higher concentrations correlated with reduced survival rates (

Figure 1C).

2.3.2. Sequential Method

The sequential extraction method was applied to further evaluate anticonvulsant activity using hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, methanol, and water fractions.

Speed Index Latency: The ethyl acetate extract had the strongest effect, with 10 and 100 µg/mL producing latencies of 334.67 and 486.67 seconds, respectively. These values were significantly higher than the control and lower concentrations (

p ≤ 0.05). The hexane extract at 100 µg/mL also showed significant effects (

p = 0.026 vs. 0.1 µg/mL,

p = 0.006 vs. 1 µg/mL) (

Figure 2A).

Whirlpool Latency: The ethyl acetate extract at 10 and 100 µg/mL significantly increased latency times (892.33 and 732.33 seconds, respectively). Both concentrations differed significantly from the control and lower doses (

p = 0.003). Hexane and dichloromethane extracts did not show significant effects (

Figure 2B).

Posture Loss Latency: The ethyl acetate extract at 10 and 100 µg/mL exhibited the longest latencies, indicating a dose-dependent effect (

p ≤ 0.05). Other extracts did not produce significant differences across concentrations (

Figure 2C).

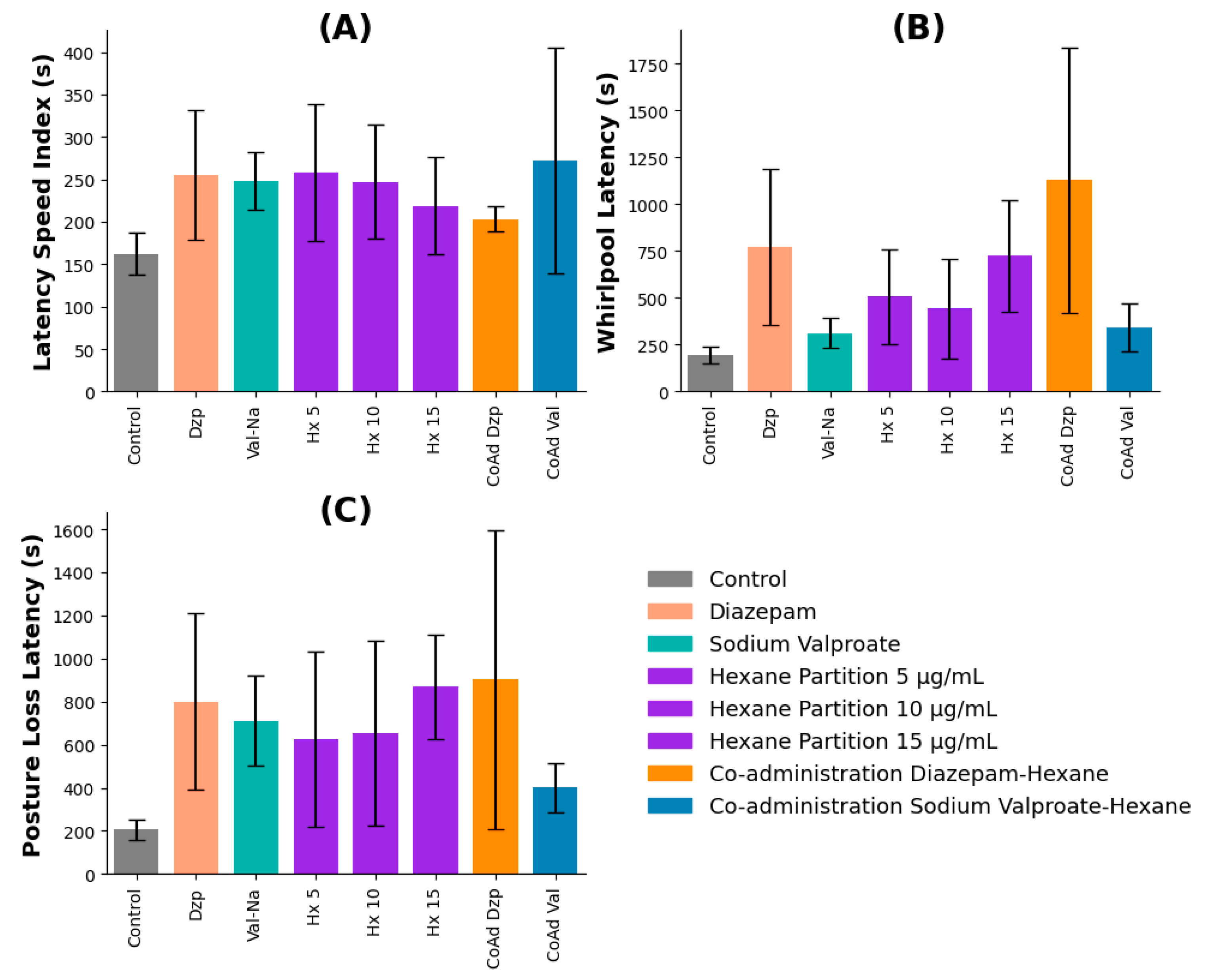

2.4. Co-administration with Pharmacological Controls

The hexane partition extract of V. persicifolia was co-administered with standard anticonvulsant drugs diazepam (Dzp) and sodium valproate (Val-Na) to evaluate potential synergistic effects. Behavioral parameters recorded included Latency IV, Whirlpool Latency, and Posture Loss Latency.

Speed Index Latency: No statistically significant differences were observed between the control, pharmacological controls, and co-administration groups (p > 0.05). However, the hexane + diazepam combination exhibited a slight, though non-significant, increase in latency compared to diazepam alone, suggesting a possible additive effect (Figure 3A).

Whirlpool Latency: Significant interactions were observed between treatments. Hexane extract (5, 10, and 15 µg/mL), diazepam, and their co-administration all significantly increased latency compared to the control. Co-administration with diazepam resulted in a nearly threefold increase in latency compared to sodium valproate (p ≤ 0.05), indicating a potential enhancement of anticonvulsant effects (Figure 3B).

Posture Loss Latency: Co-administration of hexane extract with diazepam significantly increased posture loss latency, whereas co-administration with sodium valproate did not yield a comparable effect. These findings indicate that the diazepam-hexane extract combination may provide a greater anticonvulsant effect than sodium valproate (Figure 3C).

Figure 6.

Latency metrics for zebrafish treated with V. persicifolia hexane extract in combination with pharmacological controls. (A) Speed Index Latency, (B) Whirlpool Latency, and (C) Posture Loss.

Figure 6.

Latency metrics for zebrafish treated with V. persicifolia hexane extract in combination with pharmacological controls. (A) Speed Index Latency, (B) Whirlpool Latency, and (C) Posture Loss.

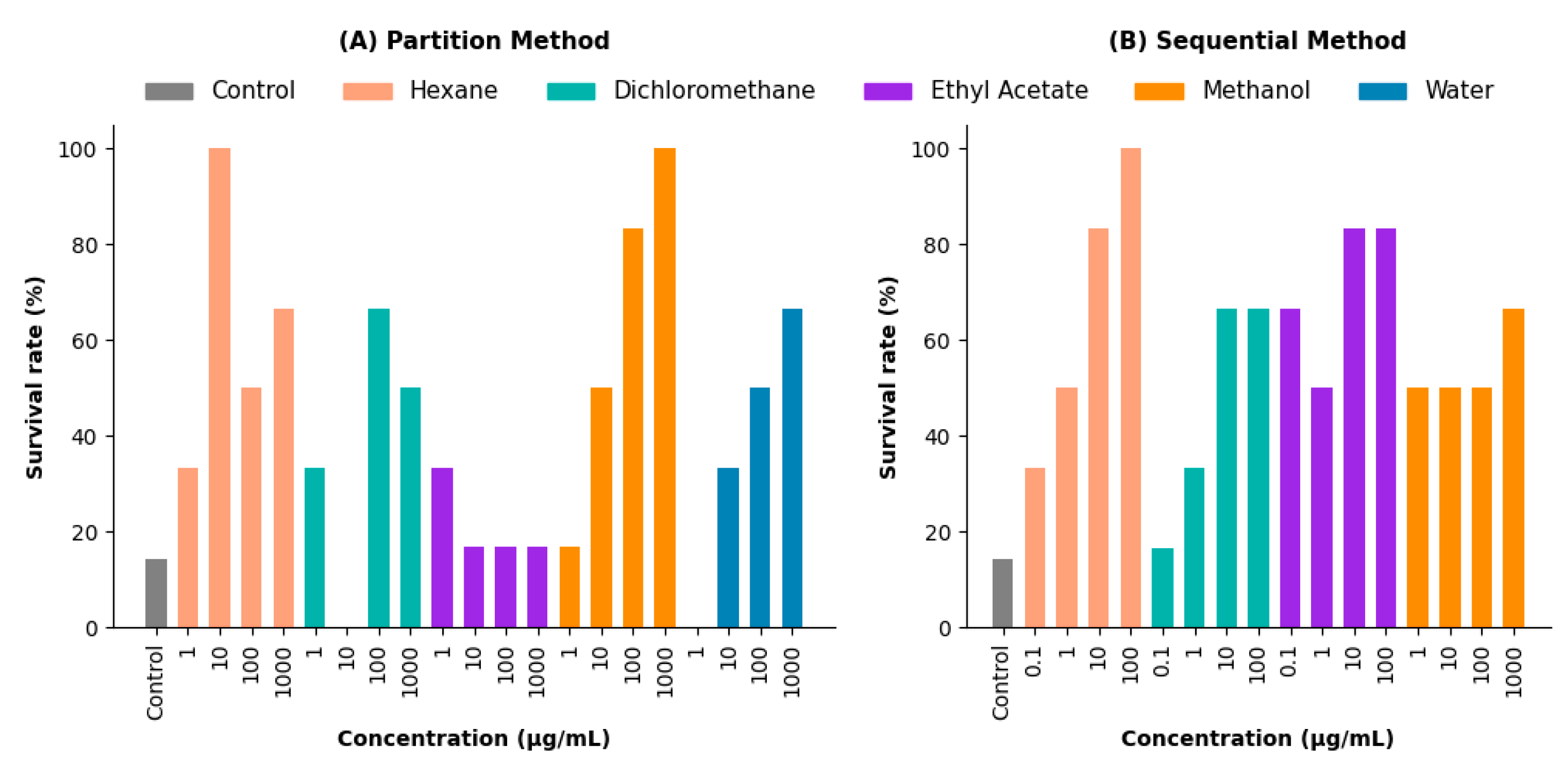

2.5. Survival Rate

The survival rates of zebrafish exposed to V. persicifolia extracts were analyzed across different experimental conditions (Figure 4).

Partition Method: The hexane extract showed the highest survival rate, reaching 100% at 1000 µg/mL. The dichloromethane extract exhibited a dose-dependent increase, with survival reaching 65% at 100 and 1000 µg/mL. In contrast, the ethyl acetate extract maintained a stable survival rate of approximately 85% across all concentrations (Figure 4A).

Sequential Method: The hexane extract attained 100% survival at 100 µg/mL, whereas other extracts, such as methanol, exhibited lower survival rates, with a maximum of 60% across all concentrations (Figure 4B).

Co-administration Assays: Diazepam, sodium valproate, and hexane extract (including co-administration treatments) achieved 100% survival, while the control group exhibited only 14.28% survival.

Figure 7.

Survival rates (%) of V. persicifolia extracts in zebrafish under different extraction methods. (A) Partition Method: Survival rates for hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, methanol, and water extracts across concentrations (1, 10, 100, and 1000 µg/mL). (B) Sequential Method: Survival rates for the same solvents across concentrations (0.1, 1, 10, 100, and 1000 µg/mL).

Figure 7.

Survival rates (%) of V. persicifolia extracts in zebrafish under different extraction methods. (A) Partition Method: Survival rates for hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, methanol, and water extracts across concentrations (1, 10, 100, and 1000 µg/mL). (B) Sequential Method: Survival rates for the same solvents across concentrations (0.1, 1, 10, 100, and 1000 µg/mL).

3. Discussion

This study demonstrates the anticonvulsant potential of V. persicifolia leaf extracts, particularly ethyl acetate and hexane fractions, in a PTZ-induced zebrafish seizure model. The results suggest that key phytochemicals, including flavonoids, alkaloids, and steroids, play a significant role in seizure modulation. This section discusses the implications of these findings, potential mechanisms of action, and the relevance of V. persicifolia as a candidate for novel anticonvulsant development.

3.1. Phytochemical Contributions to Anticonvulsant Activity

Phytochemical screening confirmed the presence of flavonoids, alkaloids, and steroids in

V. persicifolia extracts, all of which have well-documented neuropharmacological properties. Flavonoids are known to interact with γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, enhancing GABAergic transmission, which may contribute to the anticonvulsant effects observed in the ethyl acetate fraction [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Similarly, alkaloids have been reported to modulate neurotransmitter systems, either by acting as GABA agonists or by inhibiting excitatory pathways, further supporting their role in seizure suppression [

27,

28,

29]. Steroids have also been implicated in central nervous system excitability, suggesting their possible contribution to the observed anticonvulsant activity.

The increases in convulsion latency and survival rates observed in this study suggest that these phytochemicals contribute to both the enhancement of inhibitory neurotransmission and the reduction of excitatory signaling. This aligns with established models of seizure modulation, where balancing excitatory and inhibitory pathways is crucial for effective seizure control. These findings are consistent with studies on other

Verbesina species, such as

V. encelioides [

30] and

V. crocata [

31] which contain related bioactive compounds with neuroactive properties. The presence of similar metabolites in

V. persicifolia reinforces its potential as a candidate for further anticonvulsant research.

3.2. Efficacy of Extracts in Reducing Seizure Parameters

The ethyl acetate fraction showed the most substantial effect, delaying convulsion onset and reducing severe seizure behaviors. This fraction likely contains non-polar flavonoids and other bioactive compounds, which may improve blood-brain barrier permeability, enhancing CNS modulation.

The hexane fraction also demonstrated potent anticonvulsant effects, achieving 100% survival at 10 µg/mL, further supporting its therapeutic potential. This aligns with previous findings indicating that non-polar compounds exhibit stronger neuroactive effects, likely due to higher bioavailability in the CNS [

32].

Together, these data suggest that the seizure-modulating activity of V. persicifolia fractions results from a combination of inhibitory neurotransmission enhancement and excitatory pathway suppression. This aligns with established seizure control mechanisms, making these extracts promising candidates for further research in anticonvulsant drug development.

3.3. Synergistic Effects in Co-administration with Standard Anticonvulsants

The co-administration experiments demonstrated that the hexane fraction of

V. persicifolia significantly enhanced seizure latency and survival rates when combined with diazepam, suggesting a potential synergistic interaction. Diazepam is a well-established anticonvulsant that potentiates GABAergic activity by binding to GABA

A receptors, increasing inhibitory neurotransmission and reducing seizure susceptibility [

33]. The observed enhancement in anticonvulsant effects when

V. persicifolia hexane extract was co-administered with diazepam suggests that compounds within the extract may either further potentiate GABA

A receptor activity or modulate additional pathways involved in seizure control.

Compared to sodium valproate, the combination of hexane extract and diazepam resulted in a nearly threefold increase in seizure latency, highlighting a greater efficacy in delaying convulsions. This effect suggests that the hexane fraction may contain bioactive compounds capable of amplifying GABAergic signaling, reducing neuronal excitability, or enhancing diazepam's action at lower doses. The ability to use lower doses of standard anticonvulsants while maintaining efficacy is particularly relevant in epilepsy management, as it could help mitigate the side effects associated with long-term use of conventional drugs.

Similar synergistic effects have been observed in other plant-derived compounds, where phytochemicals enhance the therapeutic action of conventional drugs by either increasing bioavailability, potentiating receptor interactions, or modulating secondary signaling pathways. The observed interaction between V. persicifolia extracts and diazepam aligns with these findings, reinforcing the potential of plant-derived compounds as adjunct therapies in epilepsy management. Further research is needed to isolate the specific active constituents responsible for this synergy and to elucidate their precise mechanisms of action within the central nervous system.

3.4. Toxicity and Safety Profile

Toxicity evaluation in Artemia salina revealed that methanolic fractions exhibited low to moderate toxicity, aligning with established safety thresholds for medicinal plant extracts. However, sequentially extracted fractions (hexane and ethyl acetate) exhibited higher toxicity, likely due to increased concentrations of secondary metabolites such as terpenes and alkaloids, which are known to be cytotoxic at higher doses.

Complementary cytotoxicity tests using chicken embryo fibroblasts (AlamarBlue and MTT assays) showed that lower concentrations (0.1–1 µg/mL) were non-toxic, while higher doses exhibited moderate cytotoxic effects. This suggests that dose optimization is necessary, but within defined therapeutic ranges, V. persicifolia extracts may have a favorable safety profile for further pharmacological development.

3.5. Implications and Future Directions

The promising results from this study reinforce the potential of V. persicifolia as a therapeutic agent for seizure management, particularly when used in combination with standard anticonvulsants. The observed anticonvulsant activity of its hexane and ethyl acetate fractions suggests the presence of bioactive compounds that modulate seizure pathways, likely through GABAergic enhancement and inhibition of excitatory neurotransmission. These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting the role of medicinal plants in neurological disorders and highlight the importance of further research to fully characterize their pharmacological properties.

Future studies should focus on the isolation and structural characterization of the active constituents responsible for the anticonvulsant effects observed in this study. Advanced analytical techniques, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, could be employed to identify specific flavonoids, alkaloids, and other secondary metabolites involved in seizure modulation. Additionally, mechanistic studies should investigate how these compounds interact with neurotransmitter receptors and ion channels within the central nervous system to better understand their mode of action.

Beyond phytochemical characterization, in vivo studies using rodent models could provide further insights into the long-term efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of V. persicifolia extracts. Evaluating different dosages and administration routes will be critical in determining their clinical potential. Furthermore, exploring the potential for V. persicifolia as an adjunct therapy to conventional antiepileptic drugs could offer new treatment options, particularly for drug-resistant epilepsy cases.

The increasing interest in plant-based therapies, especially in regions with limited access to conventional epilepsy treatments, underscores the importance of integrating traditional medicine with modern pharmacological approaches. Given its promising anticonvulsant activity and favorable safety profile at lower doses, V. persicifolia represents a strong candidate for further drug development. Expanding research efforts in this area could lead to new, more accessible, and potentially safer alternatives for managing epilepsy and other neurological disorders.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material Collection

V. persicifolia leaves were collected annually in September from 2019 to 2021 in Arroyo del Potrero, municipality of Martínez de la Torre, Veracruz, Mexico, at coordinates 20°08’43.0’’N 97°03’56.1’’W. The collected material was carefully inspected to remove any damaged or yellowed leaves before processing. The leaves were air-dried in the shade with frequent turning to prevent excess moisture accumulation and potential degradation of secondary metabolites. Once fully dried, the plant material was finely ground using a mechanical grinder and stored under vacuum-sealed conditions to prevent oxidation and contamination before extraction.

For botanical authentication, a voucher specimen (Boucher V. persicifolia D.C.-AAM-002-XAL) was deposited at the National Herbarium of the Instituto Nacional de Ecología (INECOL), Mexico, where its identity was confirmed. This ensured accurate taxonomic classification and consistency across different collection years.

4.2. Preparation of Extracts

Two extraction methods were employed to isolate bioactive compounds from V. persicifolia leaves. In the sequential maceration method, 100 g of finely ground plant material was macerated in hexane for 21 days in amber flasks, with solvent decantation occurring every seven days. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure using a BUCHI R-210 rotary evaporator, and the same process was subsequently performed with dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, and methanol, resulting in four distinct solvent fractions.

For the partitioning method, an initial methanolic extract was prepared by macerating 350 g of plant material in methanol for 21 days. After filtration, the extract was concentrated under reduced pressure, and partitions were created using hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, and water. This method was adapted from [

34,

35] to optimize solvent fractionation and ensure efficient separation of bioactive metabolites.

4.3. Phytochemical Screening

The methanolic extracts from each collection year were subjected to phytochemical screening to identify the presence of secondary metabolite families such as alkaloids, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, and steroids. This analysis was based on colorimetric reactions, adapted from [

36]

4.4. Toxicological Evaluation in Artemia salina

The toxicity of

V. persicifolia extracts was evaluated using the brine shrimp lethality assay (BSLA) with

Artemia salina nauplii, following established methodologies [

37,

38]. Approximately 350 mg of

A. salina cysts were hatched in 2 L of artificial seawater (3% NaCl solution) under controlled conditions, including constant aeration, temperature (24–29 °C), and continuous light exposure. After 48 hours, the hatched nauplii were transferred to experimental test wells containing various concentrations of

V. persicifolia methanolic extracts (1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.1, and 0.05 mg/mL) prepared in 3% saline solution.

After 24 hours of exposure, the number of surviving nauplii was recorded, and mortality rates were determined. The median lethal concentration (LC50) was calculated using Probit analysis with 95% confidence intervals, employing IBM SPSS Statistics 29 for statistical analysis.

4.5. Anticonvulsant Activity in Zebrafish Model

The anticonvulsant potential of V. persicifolia extracts was evaluated in adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) using a pentylenetetrazol (PTZ)-induced seizure model. Zebrafish were pre-treated by immersion in tanks containing different extract concentrations for 30 minutes before seizure induction. Methanolic extracts were tested at 1, 10, 100, and 1000 µg/mL, while partitioned fractions were evaluated at 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 µg/mL.

Following pre-treatment, zebrafish were transferred to a 10 mM PTZ solution to induce convulsions. Behavioral responses were recorded and classified into three distinct seizure stages: stage I (increased swimming activity), stage II (whirlpool swimming), and stage III (clonus-like convulsions with loss of posture). Survival rates were monitored post-exposure to assess potential neuroprotective effects of the extracts. This protocol was adapted from [

15,

39].

4.6. Co-administration with Pharmacological Controls

To evaluate potential synergistic anticonvulsant effects, the hexane fractions of V. persicifolia, which demonstrated significant activity in the zebrafish seizure model, were co-administered with diazepam and sodium valproate. Both pharmacological controls were obtained from commercially available tablets and prepared by dissolving diazepam in methanol and sodium valproate in ethyl acetate to ensure solubility and bioavailability.

Following pre-treatment with

V. persicifolia hexane extracts, zebrafish were exposed to diazepam or sodium valproate, and key seizure parameters, including convulsion latency, seizure severity, and survival rates, were recorded. The experimental design followed methodologies adapted from [

40].

4.7. Statistical Analysis

All data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 29 and GraphPad Prism 8. Results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The median lethal concentration (LC50) values for Artemia salina toxicity assays were determined using Probit analysis, with 95% confidence intervals calculated to assess dose-dependent toxicity.

For seizure latency, severity scores, and survival rates in the zebrafish model, normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and homogeneity of variance was assessed with Levene’s test. If assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were met, parametric tests such as one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test were used for multiple comparisons. In cases where data did not meet normality assumptions, non-parametric alternatives such as the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc correction were applied. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the anticonvulsant potential of Verbesina persicifolia leaf extracts, with the ethyl acetate and hexane fractions demonstrating significant efficacy in prolonging seizure latency and improving survival rates in a PTZ-induced zebrafish seizure model. Phytochemical analysis suggests that flavonoids and alkaloids contribute to these effects by modulating GABAergic and excitatory neurotransmission pathways. The observed synergistic interaction between the hexane fraction and diazepam indicates that V. persicifolia could serve as an adjunct therapy alongside conventional anticonvulsants, potentially reducing the required doses of standard drugs and minimizing associated side effects. Toxicological assessments using Artemia salina and chicken embryo fibroblast assays confirmed a favorable safety profile at therapeutic concentrations, although a concentration-dependent increase in toxicity was observed at higher doses, particularly in non-polar fractions. This study support V. persicifolia as a promising candidate for anticonvulsant drug discovery, warranting further research to isolate its active constituents, elucidate precise mechanisms of action, and validate its efficacy and safety in advanced preclinical models. The study reinforces the potential of plant-derived compounds as viable alternatives or complements to existing therapies for neurological disorders.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Morphological characteristics of

V. persicifolia; Figure S2: GPS recording and plant material selection during collection; Figure S3: Leaf drying process for extraction; Figure S4: Dried

V. persicifolia leaves before grinding; Figure S5: Amber glass containers filled with dried plant material for maceration; Figure S6: Methanolic extract before and after drying process; Figure S7: TLC analysis of hexane and dichloromethane fractions; Figure S8: TLC analysis of methanol and aqueous fractions; Figure S9: Zebrafish in PTZ-induced seizure model setup; Figure S10: Graphical representation of partition method latency metrics; Figure S11: Graphical representation of sequential method latency metrics; Figure S12: Graphical representation of co-administration latency metrics. Table S1: Summary statistics for the partition method, including normality and ANOVA results; Table S2: One-way ANOVA test statistics for the partition method; Table S3: Tukey HSD post-hoc test results for Speed Index Latency (partition method); Table S4: Tukey HSD post-hoc test results for Whirlpool Latency (partition method); Table S5: Tukey HSD post-hoc test results for Posture Loss Latency (partition method); Table S6: Summary statistics for the sequential method, including normality and ANOVA results; Table S7: One-way ANOVA test statistics for the sequential method; Table S8: Tukey HSD post-hoc test results for Speed Index Latency (sequential method); Table S9: Tukey HSD post-hoc test results for Whirlpool Latency (sequential method); Table S10: Tukey HSD post-hoc test results for Posture Loss Latency (sequential method); Table S11: Summary statistics for the co-administration study, including normality and ANOVA results; Table S12: One-way ANOVA test statistics for Speed Index Latency (co-administration); Table S13: Mann-Whitney U test results for Whirlpool Latency (co-administration); Table S14: Mann-Whitney U test results for Posture Loss Latency (co-administration).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.R.R.-M.; M.V.S.-V.; methodology, C.A.L.-R.; S.G.-P.; software, J.Z.-L.; validation, T.J.P.; formal analysis, T.J.P.; investigation, C.A.L.-R.; resources, F.R.R.-M.; M.V.S.-V.; F.H.-R.; data curation, J.Z.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.J.P.; writing—review and editing, C.A.L.-R.; S.G.-P.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, F.R.R.-M.; project administration, F.R.R.-M.; funding acquisition, F.R.R.-M.; J.L.O.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

C.A.L-R. thanks SECIHTI of Mexico for its Ph.D. scholarship [744624]. T.J. P. acknowledges SECIHTI for the postdoctoral fellowship [MOD.ORD.10/2023-I1200/331/2023].

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are included in the article and its Supporting Information files.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank SECIHTI for economical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Organization, W. H. Epilepsy 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy.

- Fisher, R. S.; Cross, J. H.; D'Souza, C.; French, J. A.; Haut, S. R.; Higurashi, N.; Hirsch, E.; Jansen, F. E.; Lagae, L.; Moshe, S. L.; Peltola, J.; Roulet Perez, E.; Scheffer, I. E.; Schulze-Bonhage, A.; Somerville, E.; Sperling, M.; Yacubian, E. M.; Zuberi, S. M. Instruction manual for the ILAE 2017 operational classification of seizure types. Epilepsia 2017, 58(4), 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanner, A. M.; Bicchi, M. M. Antiseizure Medications for Adults With Epilepsy: A Review. JAMA 2022, 327(13), 1269–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Sha, L.; Xia, Y.; Ortyl, T. C.; Tian, X.; Chen, L. Advances in Epilepsy: Mechanisms, Clinical Trials, and Drug Therapies. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 66(7), 4434–4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodie, M. J.; Besag, F.; Ettinger, A. B.; Mula, M.; Gobbi, G.; Comai, S.; Aldenkamp, A. P.; Steinhoff, B. J. Epilepsy, Antiepileptic Drugs, and Aggression: An Evidence-Based Review. Pharmacological Reviews 2016, 68(3), 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Brodie, M. J.; Ding, D.; Kwan, P. Editorial: Epidemiology of epilepsy and seizures. Front Epidemiol 2023, 3, 1273163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakol, S.; Royer, J.; Lowe, A. J.; Bonilha, L.; Tracy, J. I.; Jackson, G. D.; Duncan, J. S.; Bernasconi, A.; Bernasconi, N.; Bernhardt, B. C. Neuroimaging and connectomics of drug-resistant epilepsy at multiple scales: From focal lesions to macroscale networks. Epilepsia 2019, 60(4), 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. D., G.; Sheng, c. Structural Simplification of Natural Products. Chem Rev 2019, 119(6), 4180–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, M. Á. M.; Oliva, v.E.; Cruz, M.M.; García, G.M.; Olazcoaga, G.T.; León, A.W. Catálogo de plantas útiles de la sierra norte de Puebla, México. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Barradas, C. Cruz-Morales, G. E., & González-Gándara, C., Plantas de uso medicinal de la Reserva Ecológica “Sierra de Otontepec”, municipio de Chontla, Veracruz, México. CienciaUAT, 2015; 9, 2, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Olguín Guerrero, M. C.; Saavedra Vélez, M. V.; López Rosas, C. A.; Camacho Pernas, M. Á.; Ramos Morales, F. R.; Alcántara López, M. G. Huichín (Verbesina persicifolia DC), planta medicinal con potencial farmacológico. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 2024; 5, 5, 13461–13477. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amora, M.; Galgani, A.; Marchese, M.; Tantussi, F.; Faraguna, U.; De Angelis, F.; Giorgi, F. S. Zebrafish as an Innovative Tool for Epilepsy Modeling: State of the Art and Potential Future Directions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(9), 7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartner, S.; Eisen, J. S.; Farmer, S. F.; Guillemin, K. J.; Kent, M. L.; Sanders, G. E. The Zebrafish in Biomedical Research: Biology, Husbandry, Diseases, and Research Applications. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Copmans, D.; Partoens, M.; Hunyadi, B.; Luyten, W.; de Witte, P. Zebrafish-Based Screening of Antiseizure Plants Used in Traditional Chinese Medicine: Magnolia officinalis Extract and Its Constituents Magnolol and Honokiol Exhibit Potent Anticonvulsant Activity in a Therapy-Resistant Epilepsy Model. ACS Chem Neurosci 2020, 11(5), 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussulini, B. H.; Leite, C. E.; Zenki, K. C.; Moro, L.; Baggio, S.; Rico, E. P.; Rosemberg, D. B.; Dias, R. D.; Souza, T. M.; Calcagnotto, M. E.; Campos, M. M.; Battastini, A. M.; de Oliveira, D. L. Seizures induced by pentylenetetrazole in the adult zebrafish: a detailed behavioral characterization. PLoS One 2013, 8(1), e54515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samokhina, E.; Samokhin, A. Neuropathological profile of the pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) kindling model. Int J Neurosci 2018, 128(11), 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Hernandez, B. A.; Del Valle-Mojica, L. M.; Ortiz, J. G. Valerenic acid and Valeriana officinalis extracts delay onset of Pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-Induced seizures in adult Danio rerio (Zebrafish). BMC Complement Altern Med 2015, 15, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, H.; Ramezani, M.; Shafaei, H.; Taghiabadi, E. Anticonvulsant effect of Berberis integerrima L. root extracts in mice. J Acupunct Meridian Stud 2013, 6(1), 12–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardari, S.; Amiri, M.; Rahimi, H.; Kamalinejad, M.; Narenjkar, J.; Sayyah, M. Anticonvulsant effect of Cicer arietinum seed in animal models of epilepsy: introduction of an active molecule with novel chemical structure. Iran Biomed J 2015, 19(1), 45–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dalla Via, L.; Mejia, M.; Garcia-Argaez, A. N.; Braga, A.; Toninello, A.; Martinez-Vazquez, M. Anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative evaluation of 4beta-cinnamoyloxy,1beta,3alpha-dihydroxyeudesm-7,8-ene from Verbesina persicifolia and derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem 2015, 23(17), 5816–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakupovic, J.; Ellmauerer, E.; Jia, Y.; Bohlmann, F.; Dominguez, X. A.; Hirschmann, G. S. Further eudesmane derivatives from verbesina species. Planta Med 1987, 53(1), 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copmans, D.; Orellana-Paucar, A. M.; Steurs, G.; Zhang, Y.; Ny, A.; Foubert, K.; Exarchou, V.; Siekierska, A.; Kim, Y.; De Borggraeve, W.; Dehaen, W.; Pieters, L.; de Witte, P. A. M. Methylated flavonoids as anti-seizure agents: Naringenin 4',7-dimethyl ether attenuates epileptic seizures in zebrafish and mouse models. Neurochem Int 2018, 112, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, A. K.; Saaby, L. Flavonoids and the CNS. Molecules 2011, 16(2), 1471–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, G. A. Flavonoid nutraceuticals and ionotropic receptors for the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. Neurochem Int 2015, 89, 120–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucher, N. J.; Carles, M. C. A pharmacological basis of herbal medicines for epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2015, 52 (Pt B), 308–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieoczym, D. S., K.; Gawel, K.; Esguerra, C.V.W.; Wlaz, P.E. Anticonvulsant Activity of Pterostilbene in Zebrafish and Mouse Acute Seizure Tests. Neurochem Res 2019, 44(5), 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, A. F.; de Andrade, J. P.; Bevilaqua, L. R.; de Souza, M. M.; Izquierdo, I.; Henriques, A. T.; Zuanazzi, J. A. Anxiolytic-, antidepressant- and anticonvulsant-like effects of the alkaloid montanine isolated from Hippeastrum vittatum. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2006, 85(1), 148–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, N. M.; Al-Sayed, E.; El-Shazly, M.; Nasser Singab, A. Alkaloids of genus Erythrina: An updated review. Nat Prod Res 2020, 34(13), 1891–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Punia, J. K.; Bladen, C.; Zamponi, G. W.; Goel, R. K. Anticonvulsant mechanisms of piperine, a piperidine alkaloid. Channels (Austin) 2015, 9(5), 317–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glennie, C. W.; Jain, S.C. Flavonol 3, 7-diglycosides of Verbesina encelioides. Phytochemistry 1980, 19, 157–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bores, A. M.; Alvarez-Santos, N.; Lopez-Villafranco, M. E.; Jacquez-Rios, M. P.; Aguilar-Rodriguez, S.; Grego-Valencia, D.; Espinosa-Gonzalez, A. M.; Estrella-Parra, E. A.; Hernandez-Delgado, C. T.; Serrano-Parrales, R.; Gonzalez-Valle, M. D. R.; Benitez-Flores, J. D. C. Verbesina crocata: A pharmacognostic study for the treatment of wound healing. Saudi J Biol Sci 2020, 27(11), 3113–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xing, S.; Liao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, W.; Sun, H. Strategies for Structural Modification of Small Molecules to Improve Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration: A Recent Perspective. J Med Chem 2021, 64(18), 13152–13173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcaterra, N. E.; Barrow, J. C. Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Diazepam (Valium). ACS Chemical Neuroscience 2014, 5(4), 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinpelu, L. A.; Akanmu, M. A.; Obuotor, E. M. Mechanism of Anticonvulsant Effects of Ethanol Leaf Extract and Fractions of Milicia excelsa (Moraceae) in Mice. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International 2018, 23(4), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaimon, L. A.; Anise, E. O.; Obuotor, E. M.; Samuel, T. A.; Moshood, A. I.; Olajide, M.; Fatoke, T. In vitro antidiabetic potentials, antioxidant activities and phytochemical profile of african black pepper (Piper guineense). Clinical Phytoscience, 2020; 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cseke, L. J.; Kirakosyan, A.; Kaufman, P. B.; Warber, S.; Duke, J. A.; Brielmann, H. L. Natural Products from Plants. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ntungwe, N. E.; Dominguez-Martin, E. M.; Roberto, A.; Tavares, J.; Isca, V. M. S.; Pereira, P.; Cebola, M. J.; Rijo, P. Artemia species: An Important Tool to Screen General Toxicity Samples. Curr Pharm Des 2020, 26(24), 2892–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, M. R.; Jovanova, B.; Panovska, T.K. Toxicological evaluation of the plant products using Brine Shrimp (Artemia salina L.) model. Macedonian Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 2014; 60, 01, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, E. R.; Lima-Rezende, C. A.; Schneider, S. E.; Garbinato, C.; Pedroso, J.; Decui, L.; Aguiar, G. P. S.; Muller, L. G.; Oliveira, J. V.; Siebel, A. M. Micronized Resveratrol Shows Anticonvulsant Properties in Pentylenetetrazole-Induced Seizure Model in Adult Zebrafish. Neurochem Res 2021, 46(2), 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, D.; Kim, Y. H.; Lee, H.; Lee, C. J. Improvement of pentylenetetrazol-induced learning deficits by valproic acid in the adult zebrafish. Eur J Pharmacol, 2010; 643, (2-3), 225–231. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).