1. Introduction

Healthy functional foods with rich nutritional value are ideal choice for quality lifestyle and food habits. As people are now more focusing on adopting healthier means and consuming nutritious organic foods, the concept of functional food is becoming more and more popular and gaining a lot of awareness. Besides providing high nutrition, metabolites from functional foods can help in ailments of many diseases and health problems. Especially in case of healthy ageing, mushrooms work as an anti-ageing super food which inhibits ROS accumulation with ageing [

1]. Mushrooms are a very popular healthy choice of functional food because of their low carbohydrate content, high protein and fiber. Also, many healthy food metabolites with medicinal properties, like ergosterol, polyphenol, tannin are enriched in mushrooms [

2]. According to department of agriculture, United states, mushroom is categorized in “other vegetables” and generally considered as a plant sourced food [

3,

4]. Among the many health benefits of mushroom, improving brain function and boosting memory is an interesting factor that draws attention for research study and opens new window for drug designing and therapeutic applications.

Flammulina velutipes, commonly known as “golden needle mushroom” or “enoki mushroom” is a common and widely consumed mushroom especially in Asian region [

5]. Because of its high content of fiber, minerals, polysaccharides and other healthy metabolites [

6] this mushroom became a healthy choice. Apart from its traditional food value, it is reported for some medicinal properties as well. As it has a higher content of antioxidant agents, it protects neurons from damage and boost brain function [

7,

8]. Recently neuroprotective peptide has been isolated from this mushroom, that can improve cognitive function [

9]. Neurotropic natural compounds and brain boosting agents have very high therapeutic impact in the case of memory as well as age related neurodegenerative diseases. Memory loss, neurodegeneration and cognitive dysfunction are some of the common phenomena in ageing people [

10,

11,

12] that degrade their quality of life and generate great burden on health care systems [

13,

14]. Different neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Amyotropic lateral sclerosis, Multiple sclerosis, Huntington disease are common example among ageing population affecting cognitive function and memory [

15,

16]. Besides medicine, functional foods and alternative natural therapies can help in management of cognitive dysfunction and memory loss [

17]. From previous research studies,

Flammulina velutipes mushroom is considered as a natural memory boosting and cognition-enhancing agent [

7,

9,

18]. It has been found that, polysaccharides of

Flammulina Velutipes show acetylcholinesterase inhibitory effect, which is responsible for its memory and cognition improvement effect [

8].

In the present study we evaluated the direct impact of ethanolic and methanolic extract of this mushroom on cultured neuron cells. Firstly, we performed GC-MS analysis of both types of extract to characterize the metabolites or chemicals present in the extract. We analyzed effects of both types of extract on neuron, estimated and compared their effect on neuronal growth and development, neuronal survival, and unleashed the mechanisms of its neuromodulatory effect. Our in-vitro experimental assay and in-silico molecular docking study suggested the active compound of the extract regulate neuronal growth via Trk receptors. Our analysis revealed the metabolites of the mushroom extracts function as neurotropic agent and shows neuronal growth by upregulating the NTRK signaling pathway.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals/Reagents

Media and all the supplements were bought from Invitrogen. Ethanol and methanol for extract preparation were bought from Sigma. Stigmasterol and Linalool used as positive control experiments were purchased from Sigma and Medchemexpress respectively.

2.2. Preparation of Extract

Flammulina velutipes mushroom were collected from local market and washed clean and air dried. The mushrooms were characterized by expert personnel. After cleaning and drying the mushrooms were chopped and powdered using liquid nitrogen. For preparing the extract powdered mushroom material were soaked in separate containers in ethanol and methanol, kept in a shaker for extract preparation. The powdered mushroom is filtered using filter paper. The dried concentrated extract is preserved in -200c and a working extract of 8mg/ml was prepared. 30,60,100 ug/ml doses of both extracts were used in this study.

2.3. Standardization of the Extract

Both the extracts have been characterized by using GC-MS (Gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy) to identify and quantify the active components in the extract. The agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA, USA) 7890A capillary gas chromatographic equipment was used to conduct GC-MS analysis. The mass spectrometer detector on the chromatograph was composed of 95% dimethylpolysiloxane and 5% phenyl. A Silica capillary column (film: 0.25µm) with the brand and model number HP-5MSI served as the chromatographic column. It had a 0.25 mm diameter and a length of 90 meters. The extract was injected into the GC apparatus in a fused silica capillary column in a total volume of 6 µL. The carrier gas (99.999% helium) was set to flow at a rate of 1 mL/min. The temperature of the injector was kept at 250 °C and the iron source temperature was adjusted to 280 °C. Initially, an isothermal temperature of 110 °C was maintained for 2 minutes. The temperature then rose by 10 °C/min until it reached 200 °C. The temperature then rose at a rate of 5 °C/min until it reached 280 °C. Finally, it was maintained for 9°C/min to 280 °C. The mass spectrum was collected in the mass-to-charge ratio region of 50 to 550 m/z. The ionization source was kept at a temperature of 250 °C, while the mass spectrometer quadruple (MS quad) was kept at 150 °C. The full GC-MS analysis procedure took 36 minutes to complete, which includes the time for data gathering as well as the numerous temperature ramps and holds. During the study, mass spectra of unexplained peaks were gathered. The acquired mass spectra were compared to the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) databases to determine the chemicals that were present in the extract.

2.4. Primary Hippocampal Neuronal Culture

Primary hippocampal culture was performed in time-pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (19th day), which were accommodated according to Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (NIH, Washington, DC, USA). The whole culture procedures followed the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care and were approved by the Institution Animal Care and Use Committee of Dongguk University (approval certificate number IACUC-1909-5. The fetal hippocampi were collected from the brain and dissociated neuronal cultures were prepared. The dissociated cells were seeded onto 12 mm coverslips previously coated with poly-DL-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 24-well culture plates at a density of 1.0 × 104 cells/cm2 . Medias for neuronal cells were prepared using neurobasal media supplemented with B27, glutamate and β-mercaptoethanol, kept in the incubator at 370c, with 5% CO2 and 95% air. Different concentration of extracts and/or vehicle was added to the culture plates prior to cell seeding.

2.5. Hypoxia/Reoxygenation (H/R)-Induced Oxidative Stress

Hippocampal cells were fed every 4 days during culture by replacing 1/4 the media with fresh prewarmed serum-free neurobasal media supplemented with B27, with or without sample extract. H/R of rat hippocampal neurons was carried out as described previously [

19,

20]. Briefly, growing the cells for 10 days, cells were transferred into a modular hypoxia chamber (Modular Incubator Chamber MIC-101; Billups-Rothenberg, Inc., Del Mar, CA, USA) in 94% N2, 5% CO

2, and 1% O

2 atmosphere, and incubated at 37°C for 4 hours. To reoxygenate hypoxic cells, culture plates were placed in a normal cell incubator (95% air, 5% CO2) and reoxygenated for 3 days. Then neuronal viability was measured using trypan blue assay.

2.6. Trypan Blue Exclusion Assay for Neuronal Viability

Trypan blue exclusion assay revealed viability of neuron after treatment with different concentration of extracts and after Hypoxia/Reoxygenation test. Cells were stained with 0.4% trypan blue solution for 30 minutes and washed with DPBS solution prior to imaging. Phase contrast images of all treatment groups were taken. The dead cells will appear as dark blue; however, the viable cells appear as normal cells because they exclude the dye.

2.7. Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was carried out the same way as described in earlier works. After culturing the neurons on the coverslips for the indicated time, neurons on coverslips were washed briefly with D-PBS, fixed with a 4% paraformaldehyde and methanol fixation procedure and blocked with 1% goat serum. Neurons were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight, followed by secondary antibody incubation for 2.5 hours, and mounted on slides.

The following antibodies were used for immunostaining: primary antibodies to tubulin α-subunit (mouse monoclonal 12G10, 1:25; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, IO), ankyrin G (rabbit polyclonal H-215, 1:25; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., CA), MAP2 (mouse monoclonal clone HM-2; 1:250; Sigma, MO), Tau (rabbit polyclonal LF-PA0172; 1:100; AbFrontier, Seoul, Korea), and secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG [1:500], Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG [1:1,000], Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG [1:1,000], Molecular Probes, OR).

2.8. Image Analysis and Quantification

A Leica Research Microscope DM IRE2 equipped with I3 S, N2.1S, and Y5 filter systems (Leica Microsystems AG, Wetzlar, Germany) was used for phase-contrast and epifluorescence microscopy. Images (1,388 × 1,039 pixels) were acquired with a high-resolution CoolSNAPTM CCD camera (Photometrics Inc., Munchen, Germany) under the control of a computer using Leica FW4000 software. The digital images were processed using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 software.

Morphometric analyses and quantification were performed with an Image J (version 1.49) software with the simple neurite tracer plug-in (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD) and Sholl plug-in (

http://biology.ucsd.edu/labs/ghosh/software).

2.9. In Silico Evaluation of Neuroprotective Activity

2.9.1. Glide Molecular Docking Analysis

To extract the chemical structures of the compounds found in the GC-MS results, we used the PubChem database. The LigPrep module of the Schrödinger suite 2023-2 was harnessed to construct three-dimensional (3D) representations of these structures. By adjusting the pH to 7.0 and employing the Epik 2.2 program, the ionization states of each ligand were predicted [

21]. This study created a maximum of 32 probable conformers for each ligand, and from these, the conformer with the least energy was selected for additional analysis.

The 3D crystal structures of TrkA and TrkB bearing PDB IDs 1WWW (TrkA) and 1HCF (TrkB) were extracted from the RCSB protein databank. These structures were subsequently prepared utilizing the protein preparation module within the Schrödinger suite 2023-2 program, which involves assigning the appropriate charges, hydrogen, and bond orders to 3D structures. All hydrogen bonds within the crystal structure were optimized at neutral pH by removing irrelevant water molecules.

The procedure of minimization was carried out by utilizing the OPLS3 force field module4, taking into consideration that the structural modification should not exceed 0.30 Å of its root mean square deviation. By constructing a grid box at the reference ligand binding of the protein, the protein’s active site was set for the purpose of docking simulation. The parameters of grid generation remained at their normal settings, having a bounding box size of 14 \AA × 14 \AA × 14 \AA, and post-minimization was carried out harnessing the OPLS3 force field. Van der Waals scaling factor and charge cutoff were fixed at 1.00 and 0.25, respectively [

22]. With the aid of Schrodinger-Maestro version 9.4 [

23,

24], glide docking via extra precision (XP) was executed, where all ligands were regarded as flexible by considering the van der Waals factor (0.80) and the partial charge (0.15) and OPLS_3 force field was employed to minimize the docked complex. Following docking, for each ligand the docking pose having least Glide score were considered for further analysis [

22].

2.9.2. Binding Energy (MM-GBSA) Analysis

Next, binding free energy (MM-GBSA) analyses were carried out harnessing the Prime MM-GBSA wizard of the Schrödinger suite 2023-2 program [

25], in which an increased negative value indicates higher stability. The docking pose viewer file with the least Glide score obtained following Glide XP docking was subjected to analyses, in which the sampling minimization protocol was implemented with OPLS2005 force field as Molecular Mechanics (MM) and Generalized Born Surface Accessible (GBSA) as continuum model, maintaining the protein flexible [

26,

27,

28,

29]. The dielectric solvent model, for instance, VSGB 2.0, was employed to rectify the empirical functions of π-stacking and hydrogen bond (H-bond) interactions [

30].

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The findings of this study were reported using the standard error from the mean (S.E.M.), which was obtained from at least three unique replicates of each test, except when specified differently. With the assistance of GraphPad Prism having version 8.0.0 (San Diego, California, United States), the statistical comparisons were carried out by employing either the Student's t-test or the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), which was subsequently accompanied by Duncan's multiple comparison test. When the p-value was less than 0.05 (p-value < 0.05), it was statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Viability of Different Doses of FVME and FVEE

By performing trypan blue exclusion assay, the effect of different doses of FVME and FVEE on neuronal viability was tested. Here the numbers of live cells and dead cells were counted. The statistical analysis of the calculation showed that (

Figure 1), all doses of the extracts enhanced the viability of the neurons.

3.2. Dose Dependent Selection of FVME and FVEE Selection for Neurite Growth

From the morphological analysis performed on cultured hippocampal neuronal cells, we noticed a dose-dependent growth effect of neurons because of treatment from FVME and FVEE. Cultured neurons were allowed to grow until 3rd day, with and/or without different concentrations of FVME and FVEE. On 3rd day phase-contrast images were taken for performing analysis. We analyzed morphological parameters of neuronal growth, number of primary processes, length of the longest process, sum of all the process as represented in

Figure 1. According to all the parameters the neuron shows significant growth in extract treated condition compared to control (vehicle) condition. Based on the results we used FVME 30 µm and FVME 100 µm doses for further analysis.

However, the neuronal growth on FVME treated neurons was more significant compared to the FVVEE treated neurons. FVME treatment showed significant improvement on all three growth parameters (

Figure 2). Which implies FVME has more prominent action on neuronal growth compared to FVEE. Based on this finding, we performed further neuro-architecture analysis by treating neurons with FVME.

3.3. Early Neuronal Development by FVME and FVEE

After investigating the optimized concentration of FVME and FVEE, we applied that concentration on primary cultured neurons to investigate their impact on early development. Neuronal maturation or early development of neurons were analyzed by incubating the neurons with vehicles and the extracts in mentioned doses until 1st day and 2nd day of culture. The developmental phases of neurons were divided into three categories, lamellipodia, small process, and axonal outgrowth [

31]. Our statistical analysis showed (

Figure 2B) after treating with FVME and FVEE more neurons were transformed into the advanced developmental stage compared to vehicle treatment. During the first 24 hours both the extracts showed significant advancement in developing the neurons into minor process stage compared to vehicle. At 48 hours, the neurons development into axonal outgrowth stage have been noticed significantly by both extracts.

Neurons at 24 hours and 48 hours, with or without extract treatment were immunostained with Tau and Map2 antibody (

Figure 2A) which are axonal and dendritic markers respectively. In this experiment 100 µM dose of both FVME and FVEE have been used.

Figure 3.

Neuronal maturation at early stage of neuronal development significantly promoted by FVME and FVEE. (a) Represents neuronal growth on vehicle/FVME/FVEE treated condition at 24 hours immunostained with Map2 (neuronal marker, green) and Tau (dendritic marker, red). (b) shows different stages (lamellipodia, minor process, axonal outgrowth) of neurons. (c) shows statistical analysis of neurons on different developmental stages. (d) Represents neuronal growth on vehicle/FVME/FVEE treated condition at 48 hours immunostained with Map2 (green) and Tau (red). (e) shows different stages (lamellipodia, minor process, axonal outgrowth) of neurons. (f) shows statistical analysis of neurons on different developmental stages. Scale bar=10 µm.

Figure 3.

Neuronal maturation at early stage of neuronal development significantly promoted by FVME and FVEE. (a) Represents neuronal growth on vehicle/FVME/FVEE treated condition at 24 hours immunostained with Map2 (neuronal marker, green) and Tau (dendritic marker, red). (b) shows different stages (lamellipodia, minor process, axonal outgrowth) of neurons. (c) shows statistical analysis of neurons on different developmental stages. (d) Represents neuronal growth on vehicle/FVME/FVEE treated condition at 48 hours immunostained with Map2 (green) and Tau (red). (e) shows different stages (lamellipodia, minor process, axonal outgrowth) of neurons. (f) shows statistical analysis of neurons on different developmental stages. Scale bar=10 µm.

3.4. Axonal Development by FVME

Because the FVME showed prominent neuronal development effect, we explored the effect of FVME (100ug/ml dose) on neuronal branching by “Sholl analysis”. The morphological analysis showed that FVME significantly improved the axonal growth outcome in cells growing until the 5th day of the culture. The analysis showed FVME significantly improved axon length and axonal branching of neurons. As represented by the statistical analysis, FVME increased the number and length of primary, secondary and tertiary branching of axons significantly. Neurons immunostained with axonal marker Ankyrin G and microtubule marker tubulin are represented in

Figure 4.

For more detailed insight, we performed “Sholl analysis”, which showed FVME treatment increased axonal collateral branching which eventually improved cytoarchitecture of the neurons.

FVME treated neurons surpassed axonal intersections by 1.64 folds than that of the vehicle-treated neurons. FVME treatment showed axonal intersection up to the circle of 220 μm, while control neurons exhibited only up to 190 μm on the concentric circles of Sholl. Furthermore, FVME increased the collateral branching points by 3.04-folds than the vehicle (

Figure 4), and thus, collateral branching points for WSEE-treated neurons could be observed up to 270 μm of Sholl circle while there were none beyond 120 μm in vehicle treatment.

3.5. Dendritogenic Arborization by FVME

Dendritic branching is a crucial factor for memory storage. So next we analyzed the dendritic development after FVME extract treatment and incubation until DIV 5. The morphologic analysis showed FVME treatment helped neurons to upregulate dendrites number and branching. Firstly, the number and length of primary dendrites were significantly increased by FVME treatment. Secondly, the number and length of branches (primary and secondary) of dendrites are elevated significantly.

Later, Sholl analysis also revealed the improvement in dendritic arborization. FVME enhance dendritic intersection 1.63 folds compared to vehicle. Also, dendritic branching points are increased 3.5 folds compared to vehicle. Altogether, this data suggests that FVME promotes dendritic development.

3.6. FVME and FVEE Neuroprotective Effect Against H/R

To evaluate the neuroprotective effect of FVME and FVEE, we induced hypoxia mediated oxidative stress as well as cellular injury. Neurons are especially susceptible to hypoxia, as absence of oxygen cause neuronal injury, initiate neuronal death, stop neuronal function, restrict synaptic transmission [

32]. In our experiment we induced hypoxia for 4 hours and analyzed the viability by trypan blue assay after 4 days of hypoxia.

As shown in

Figure 5b FVEE increased neuronal viability compared to the vehicle treatment. FVEE in 100 µM dose significantly attenuated hypoxia mediated neuronal death. In case of FVME, all doses showed significant neuroprotective effect compared to vehicle (

Figure 5c). However, 60 µM dose showed the best neuroprotective effect based on neuronal viability. These outcomes suggest, both FVME and FVEE can provide neuroprotection against hypoxia induced brain injury or neuronal death.

Figure 5.

FVME upregulated dendritic arborization. Representative neurons traced for sholl analysis are shown in (a) and (b), for vehicle and FVME treatment respectively. (c) statistical analysis shows FVME treatment significantly increased the number and length of primary dendrites. (d) statistical analysis shows FVME significantly increased number and length of dendritic branches. Sholl analysis revealed numbers of dendritic intersection(e) and numbers of dendritic branching points (f) which are higher in case of FVME treatment.

Figure 5.

FVME upregulated dendritic arborization. Representative neurons traced for sholl analysis are shown in (a) and (b), for vehicle and FVME treatment respectively. (c) statistical analysis shows FVME treatment significantly increased the number and length of primary dendrites. (d) statistical analysis shows FVME significantly increased number and length of dendritic branches. Sholl analysis revealed numbers of dendritic intersection(e) and numbers of dendritic branching points (f) which are higher in case of FVME treatment.

Figure 6.

Neuroprotective effect of extracts (FVEE/FVME) from hypoxia mediated neuronal death. (a) represents bright-field images of trypan blue stained primary neurons grown until DIV13 in hypoxia/reoxygenation condition in the presence of vehicle or various concentrations of FVEE. (b) The statistical analysis shows various doses of FVEE improve neuronal viability, however 100 µM significantly improved neuronal viability under H/R injury. (c) represents bright-field images of trypan blue stained primary neurons grown until DIV13 in hypoxia/reoxygenation condition in the presence of vehicle or various concentrations of FVME. (d) The statistical analysis shows various doses of FVME (30, 60, 100 µM) improve neuronal viability significantly under H/R injury. The small arrow shows the dead cells in the culture. Scale Bar=20 µm.

Figure 6.

Neuroprotective effect of extracts (FVEE/FVME) from hypoxia mediated neuronal death. (a) represents bright-field images of trypan blue stained primary neurons grown until DIV13 in hypoxia/reoxygenation condition in the presence of vehicle or various concentrations of FVEE. (b) The statistical analysis shows various doses of FVEE improve neuronal viability, however 100 µM significantly improved neuronal viability under H/R injury. (c) represents bright-field images of trypan blue stained primary neurons grown until DIV13 in hypoxia/reoxygenation condition in the presence of vehicle or various concentrations of FVME. (d) The statistical analysis shows various doses of FVME (30, 60, 100 µM) improve neuronal viability significantly under H/R injury. The small arrow shows the dead cells in the culture. Scale Bar=20 µm.

3.7. Chemical Characterization of FVME and FVEE

From the GC-MS analysis of FVME and FVEE, we found 21 and 22 compounds respectively (

Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Among all these compounds “Linalool” and “DODECANE, 1-FLUORO” were common in both the extracts. GC-MS analysis of FVEE showed 0.089% of the peak area with a retention time of 9.17 min for linalool. On the other hand, linalool in FVME was represented by a peak area of 0.2335% with same retention time. As linalool is a well-established compound that is involved in treating neurodegeneration [

33,

34,

35] and have neuroprotective [

36,

37], memory boosting activity [

38], we applied linalool as a positive control. Our

Supplementary Figure S1 also showed the neuritogenic effect of “Linalool” on primary culture hippocampal neurons and its comparison with our experimental extrcts.

3.8. Mechanistic Analysis of Neurogenic Effect of FVME

To analyze the mechanistic details of FVME and FVEE, we explored the neurotropic signaling pathway. By using both NTRK1/TrkA and NTRK2/TrkB receptor inhibitors we analyzed neuronal morphological growth and found neuronal growth inhibition in the presence of the inhibitors. Here we used GW441756 and Ana 12 which are NTRK1 and NTRK2 inhibitor respectively.

Figure 5 shows neuronal growth restriction by NTRK receptor subtypes’ inhibition. Reduction in the morphological parameters (Sum of all the process, number of primary processes, length of the longest process) illustrates evidence that, FVME and FVEE exerts neurotropic action via NTRK signaling pathway. From statistical analysis, it was found that FVEE mediated neuronal growth is dependent on both NTRK1 and NTRK2 receptor as the growth is downregulated by both the inhibitors. Nevertheless, in the case of FVME, the growth parameters are mainly inhibited by Ana-12 (NTRK1 inhibitor) indicating NTRK1 receptor mediated neurotropic action. 100 µM dose of both FVME and FVEE have been used.

Figure 7.

NTRK1 and NTRK2 mediated neurodevelopment by FVME and FVEE. (a) represents neurons (DIV 3) stained with Tubulin in absence or presence of vehicle/FVME/FVEE with NTRK1 inhibitor GW441756, and NTRK2 inhibitor ANA12. (b) Statistical analysis shows that neurodevelopmental parameters (number of primary processes, length of the longest process, sum of all the processes) mediated by FVEE is inhibited by Ana12, and GW441756. FVME mediated neuronal growth parameters are predominately inhibited by Ana12. Scale bar=20 µm.

Figure 7.

NTRK1 and NTRK2 mediated neurodevelopment by FVME and FVEE. (a) represents neurons (DIV 3) stained with Tubulin in absence or presence of vehicle/FVME/FVEE with NTRK1 inhibitor GW441756, and NTRK2 inhibitor ANA12. (b) Statistical analysis shows that neurodevelopmental parameters (number of primary processes, length of the longest process, sum of all the processes) mediated by FVEE is inhibited by Ana12, and GW441756. FVME mediated neuronal growth parameters are predominately inhibited by Ana12. Scale bar=20 µm.

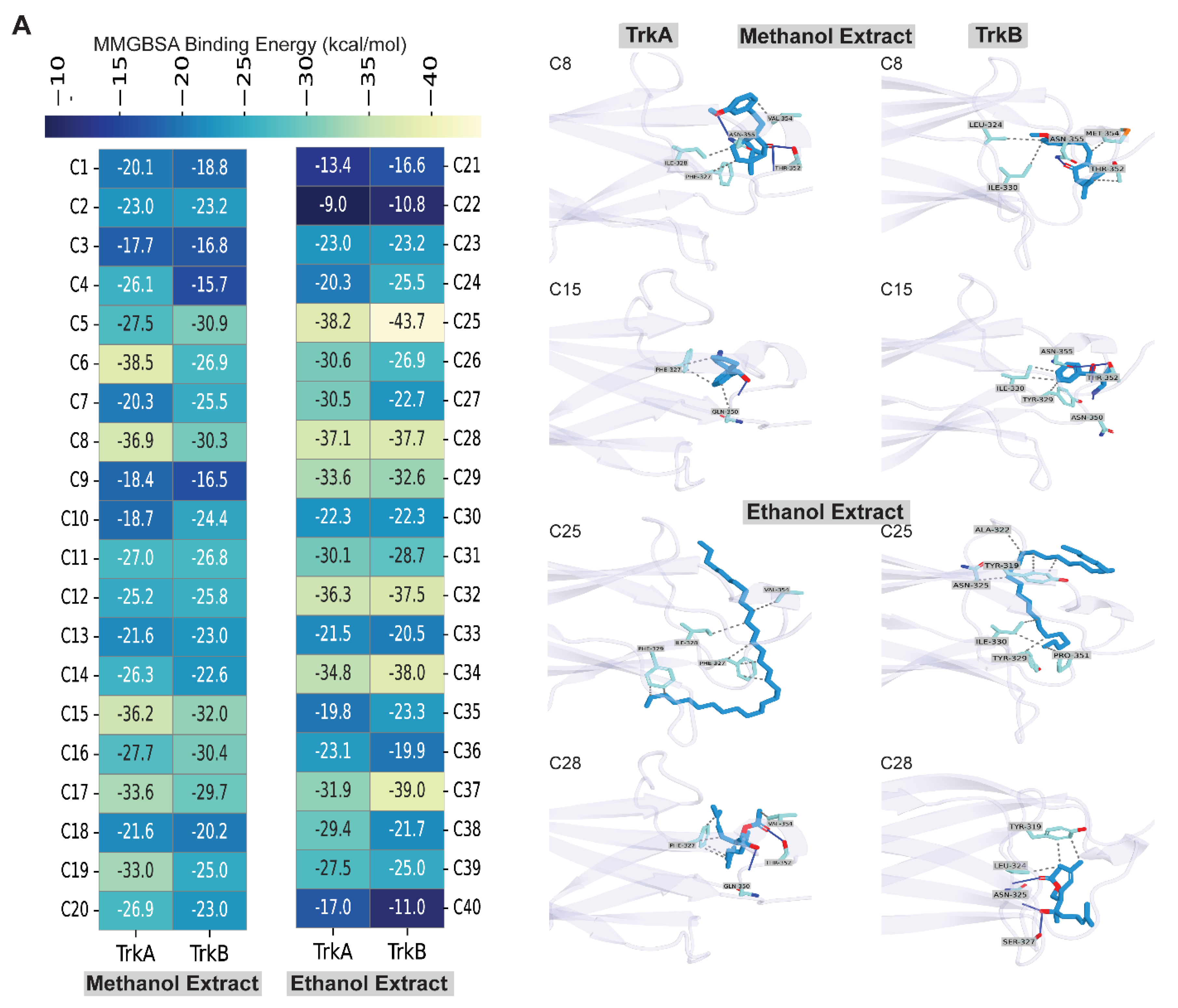

3.9. In Silico Assessment of Neuroprotective Activity

Next, we further assess the neuroprotective mechanism of the compounds identified from methanol and ethanol extracts of

Flammulina velutipes by GC-MS, utilizing two potential targets, NTRK1/TrkA and NTRK2/TrkB, with in-silico molecular interactions and binding energy analyses. At first, we conducted molecular docking using an extra precision algorithm, followed by MM-GBSA binding energy calculation, which revealed that all compounds exhibited binding energy ranging from -9 kcal/mol to -38 kcal/mol with TrkA receptor and from -10 to -43 kcal/mol with TrkB receptor. Two compounds were found common in both methanol and ethanol extracts, but their binding energies with TrkA and TrkB were notably lower (

Figure 8A). The compounds that displayed the highest binding energy were additionally studied for molecular interactions with these receptors, TrkA and TrkB.

Analysis of the binding energy of compounds found in methanol extracts revealed that all compounds exhibited binding energy with both TrkA and TrkB receptors (

Figure 8A). To select the top hits having favorable binding energy with both TrkA and TrkB, we set a threshold value of -30 kcal/mol, which was met by two compounds, having a binding energy of at least -30 kcal/mol with both TrkA and TrkB. According to

Figure 8A, the binding energies of C8 with TrkA and TrkB were -36.9 kcal/mol and -30.3 kcal/mol, respectively, whereas the binding energies of C15 were -36.2 kcal/mol and -32 kcal/mol, respectively. When we analyzed the molecular interactions of C8, we found that it made three hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) with the TrkA, with two residues Thr352 and Asn355, whereas it formed three hydrophobic interactions with Phe327, Ile328, and Val354 residues. C15 formed 1 hydrogen bond with Gln350, whereas it formed three hydrophobic interactions with Phe327 and Gln350 residues. On the other hand, with TrkB, C8 formed 1 hydrogen bond with the Asn355 residue but formed four hydrophobic interactions with Leu324, Ile330, Thr352, and Met354 residues. C15, on the other hand, formed 4 hydrogen bonds with Asn350, Thr352, and Asn355 and 4 hydrophobic interactions with Tyr329, Ile330, and Thr352.

Study of the binding energy of compounds present in ethanol extracts showed that each compound exhibited binding energy with TrkA and TrkB receptors (

Figure 8B). We adopted a cutoff value of -37 kcal/mol to identify the top hits with good binding energy with both TrkA and TrkB; two compounds met this value with a binding energy of at least -37 kcal/mol with both TrkA and TrkB. The results in

Figure 8B indicate that the binding energies of C25 with TrkA and TrkB were -38.2 kcal/mol and -43.7 kcal/mol, whereas the binding energies of C28 with TrkA and TrkB were -37.1 kcal/mol and -37.7 kcal/mol. Analysing the molecular interactions of C25 with TrkA demonstrated seven hydrophobic interactions with four residues, including Phe327, Ile328, Phe329, and Val354, whereas C28 established two hydrogen bonds with Gln350 and Thr352 residues and five hydrophobic interactions with two residues, including Phe327 and Val354. In the case of TrkB, C25 made eight hydrophobic bonds with six residues, including Tyr319, Ala322, Asn325, Tyr329, Ile330, and Pro351. In contrast, C28 created three hydrogen bonds with two Asn325 and Ser327 and three hydrophobic contacts with two residues, including Tyr319 and Leu324. Collectively, these results suggest that C8 and C15 from the methanol extract and C25 and C28 from the ethanol extract of

Flammulina velutipes have notable neuroprotective activity and can be developed as novel TrkA and TrkB agonists by assessing their neuroprotective activity using in-vivo studies.

4. Discussion

Neuroprotective and brain boosting neurotrophic compounds found from natural sources can be used as future medicinal candidates for managing neurodegeneration. Loss of neurotrophic support is a hallmark of neurite degeneration leading to neurodegenerative disorders (ND). Thus, pharmacological agents that promote neuritogenesis may offer therapeutic potential by reversing early pathological changes.

In this study, we demonstrated the efficacy of FVEE and FVME in promoting early development and differentiation of primary hippocampal neurons. From the initial viability, maturation and neuro-morphological analysis we found that FVME and FVEE initiate neuronal viability, neurite outgrowth, and network formation, indicating the presence of neuro-developmental bioactive compounds with both neurotrophic and neuroprotective properties. However, the neuromorphological analysis, early developmental analysis, and viability studies show FVME has more neurodevelopmental potential compared to FVEE.

Across early (Stages I–II) both FVME and FVEE significantly promoted neurons from early developmental phase (like lamellipodia) to mature phases (like neurons with minor processes and axonal outgrowth). As in both neuronal growth analysis and early development FVME showed more prominent action compared to FVEE, we further analyzed the effect of FVME on mature neurodevelopmental stages. In case of mature stage, axonal and dendritic extension and branching—key parameters for establishing robust neural networks. These morphological enhancements consist of improved synaptic plasticity and cognitive function [

39,

40]. According to our experimental findings, FVME significantly upregulated axonal and dendritic arborization and architecture (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

To characterize the key reason behind

Flammulina velutipes mediated neuronal growth, we performed GC-MS analysis of both ethanolic and methanolic extract. From the analysis of GC-MS, we detected 21 and 22 metabolites in FVEE and FVME respectively. Linalool was a common metabolite found in both the extracts. Linalool is a monoterpene volatile compound mostly available in aromatic plants [

41]. Also, many studies have already established linalool as a potential phytochemical for treating neuronal diseases [

35,

42,

43]. In this present work, linalool was administered to primary neurons, and its effects on neuronal growth parameters were compared to those of FVME and FVEE. Linalool elicited a significant neurotropic response, indicating that the neurotropic activity of FVME and FVEE is primarily attributable to linalool.

To validate the mechanistic role of the extracts’ neurotrophic effect, we performed molecular docking analysis of linalool with NTRK receptors, and the result reflected that linalool bind effectively with Trk receptors. Our analysis in neuronal growth and development (DIV 3) also reflected that involvement of NTRK1 and NTRK2 receptors (

Figure 5). However,

Altogether, our findings highlight the NTRK signaling pathway dependent mechanism through which FVME and FVEE promote neuronal development and survival. While TrkA/NTRK1 signaling appears to be a primary mediator, we do not exclude the possibility that the extracts also modulate additional pathways through their diverse chemical constituents.

Still, the study has certain limitations, which offer the pathways for future in-vivo and more detailed research work for understanding the mechanistic application with more certainty. Future studies should aim to characterize these secondary metabolites and delineate their roles using appropriate positive controls and targeted pathway analyses.

Figure 9.

The pictorial representation shows Flammulina velutipes modulates neuronal growth and viability in an NTRK1 derived pathway. The NTRK1 receptor is activated by the neurotrophic metabolites present in the mushroom extracts and eventually promotes neuronal maturation, neuronal morphological development, axonal and dendritic cytoarchitecture, and neuronal survival.

Figure 9.

The pictorial representation shows Flammulina velutipes modulates neuronal growth and viability in an NTRK1 derived pathway. The NTRK1 receptor is activated by the neurotrophic metabolites present in the mushroom extracts and eventually promotes neuronal maturation, neuronal morphological development, axonal and dendritic cytoarchitecture, and neuronal survival.

5. Conclusions

In this present work, we experimentally proved the role of methanolic and ethanolic extract of Flammulina velutipes mushroom as a neurotrophic agent. Our in-vitro analysis revealed both extracts of Flammulina velutipes mushroom have significant neuronal developmental and neuro-protective effect that can be useful in treatment of neurodegenerative and memory related disorders. Altogether, this mushroom has potential to be used as a medicinal agent in an NTRK dependent signaling pathway. Additional neuro-morphological and in-silico molecular docking analysis also proved bioactive metabolites of these extracts interact with NTRK1 subtype of the receptor. Altogether these findings suggest that Flammulina velutipes mushroom should be studied more and analyzed mechanistically for future drug designing for neurodegenerative diseases and dementia.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and R.D.; methodology, S.M.; software, R.D.; B.A. validation, S.M., R.D. and B.A.; formal analysis, K.M.; investigation, X.X.; resources, K.M.; I.S.M.; data curation, S.M.; R.D.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, R.D.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, R.D.; I.S.M.; K.M.; project administration, S.M.; R.D.; I.S.M.; funding acquisition, I.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (NRF-2021R1A2C1008564 to I.S.M.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Animal handling was performed based on the guidelines provided by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Dongguk University, College of Medicine, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Luo, J.; Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. Unlocking the Power: New Insights into the Anti-Aging Properties of Mushrooms. J Fungi (Basel) 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Nanda, P.K.; Dandapat, P.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Gullón, P.; Sivaraman, G.K.; McClements, D.J.; Gullón, B.; Lorenzo, J.M. Edible Mushrooms as Functional Ingredients for Development of Healthier and More Sustainable Muscle Foods: A Flexitarian Approach. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.W.; Hoskin, R.T.; Komarnytsky, S.; Moncada, M. Mushrooms as Functional and Nutritious Food Ingredients for Multiple Applications. ACS Food Science & Technology 2022, 2, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Fulgoni Iii, V.L. Nutritional impact of adding a serving of mushrooms to USDA Food Patterns – a dietary modeling analysis. Food & Nutrition Research 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Hoo, P.C.; Tan, L.T.; Pusparajah, P.; Khan, T.M.; Lee, L.H.; Goh, B.H.; Chan, K.G. Golden Needle Mushroom: A Culinary Medicine with Evidenced-Based Biological Activities and Health Promoting Properties. Front Pharmacol 2016, 7, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Cui, L. Identification of Secondary Metabolites in Flammulina velutipes by UPLC-Q-Exactive-Orbitrap MS. Journal of Food Quality 2021, 2021, 4103952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yu, J.; Zhao, L.; Ma, N.; Fang, Y.; Pei, F.; Mariga, A.M.; Hu, Q. Polysaccharides from Flammulina velutipes improve scopolamine-induced impairment of learning and memory of rats. Journal of Functional Foods 2015, 18, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Fang, Y.; Liang, J.; Hu, Q. Optimization of ultrasonic extraction of Flammulina velutipes polysaccharides and evaluation of its acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. Food Research International 2011, 44, 1269–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, L.; Ma, G.; Ma, N.; Zhang, J.; Ji, Y.; Liu, L. A novel neuroprotective peptide YVYAETY identified and screened from Flammulina velutipes protein hydrolysates attenuates scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment in mice. Food Funct 2024, 15, 6082–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.; Zaudig, M. Mild cognitive impairment in older people. The Lancet 2002, 360, 1963–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, G.W. What we need to know about age related memory loss. BMJ 2002, 324, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R. Research into ageing and older people. Journal of Nursing Management 2008, 16, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Willis, R.; Feng, Z. Factors influencing quality of life of elderly people with dementia and care implications: A systematic review. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 2016, 66, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holopainen, A.; Siltanen, H.; Pohjanvuori, A.; Mäkisalo-Ropponen, M.; Okkonen, E. Factors Associated with the Quality of Life of People with Dementia and with Quality of Life-Improving Interventions: Scoping Review. Dementia 2017, 18, 1507–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orme, T.; Hernandez, D.; Ross, O.A.; Kun-Rodrigues, C.; Darwent, L.; Shepherd, C.E.; Parkkinen, L.; Ansorge, O.; Clark, L.; Honig, L.S.; et al. Analysis of neurodegenerative disease-causing genes in dementia with Lewy bodies. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 2020, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birajdar, S.V.; Mulchandani, M.; Mazahir, F.; Yadav, A.K. Chapter 1 - Dementia and neurodegenerative disorder: An introduction. In Nanomedicine-Based Approaches for the Treatment of Dementia; Gupta, U., Kesharwani, P., Eds.; Academic Press, 2023; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, R.-Z.; Luo, H.-M.; Liu, Y.-P.; Wang, S.-S.; Hou, Y.-J.; Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Lv, H.-L.; Tao, X.-Y.; Jing, Z.-H.; et al. Food Functional Factors in Alzheimer’s Disease Intervention: Current Research Progress. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, X.; Jin, G.; Zhang, Y. Cognitive-enhancing effect of polysaccharides from Flammulina velutipes on Alzheimer's disease by compatibilizing with ginsenosides. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 112, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ding, A.-s.; Wu, L.-y.; Ma, Z.-m.; Fan, M. [Establishment of the model of oxygen-glucose deprivation in vitro rat hippocampal neurons]. Zhongguo Ying Yong Sheng Li Xue Za Zhi 2003, 19, 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Mohibbullah, M.; Hannan, M.A.; Choi, J.-Y.; Bhuiyan, M.M.H.; Hong, Y.-K.; Choi, J.-S.; Choi, I.S.; Moon, I.S. The Edible Marine Alga Gracilariopsis chorda Alleviates Hypoxia/Reoxygenation-Induced Oxidative Stress in Cultured Hippocampal Neurons. Journal of Medicinal Food 2015, 18, 960–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju Dash, S.M.Z.H., Md. Rezaul Karim, Mohammad Shah Hafez Kabir, Mohammed Munawar Hossain, Md. Junaid, Ashekul Islam, Arkajyoti Paul, Mohammad Arfad Khan. In silico analysis of indole-3-carbinol and its metabolite DIM as EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in platinum resistant ovarian cancer vis a vis ADME/T property analysis; ssue: 11: 2015; Volume Volume: 5, pp. 073-078.

- Banerjee, K.; Gupta, U.; Gupta, S.; Wadhwa, G.; Gabrani, R.; Sharma, S.K.; Jain, C.K. Molecular docking of glucosamine-6-phosphate synthase in Rhizopus oryzae. Bioinformation 2011, 7, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repasky, M.P.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; et al. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J Med Chem 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Repasky, M.P.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Halgren, T.A.; Sanschagrin, P.C.; Mainz, D.T. Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein-ligand complexes. J Med Chem 2006, 49, 6177–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, B.; Umamaheswari, A.; Puratchikody, A.; Velmurugan, D. Selection of an improved HDAC8 inhibitor through structure-based drug design. Bioinformation 2011, 7, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, F.; Liu, L.; Lei, B.H.; Dong, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.; Pan, S. Li3AlSiO5: the first aluminosilicate as a potential deep-ultraviolet nonlinear optical crystal with the quaternary diamond-like structure. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2016, 18, 4362–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Li, N.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Characterization of domain-peptide interaction interface: prediction of SH3 domain-mediated protein-protein interaction network in yeast by generic structure-based models. J Proteome Res 2012, 11, 2982–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Li, Y.; Tian, S.; Xu, L.; Hou, T. Assessing the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 4. Accuracies of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methodologies evaluated by various simulation protocols using PDBbind data set. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2014, 16, 16719–16729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Li, Y.; Shen, M.; Tian, S.; Xu, L.; Pan, P.; Guan, Y.; Hou, T. Assessing the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 5. Improved docking performance using high solute dielectric constant MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA rescoring. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2014, 16, 22035–22045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Abel, R.; Zhu, K.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, S.; Friesner, R.A. The VSGB 2.0 model: a next generation energy model for high resolution protein structure modeling. Proteins 2011, 79, 2794–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, S.; Munni, Y.A.; Dash, R.; Sultana, A.; Moon, I.S. Unveiling the effect of Withania somnifera on neuronal cytoarchitecture and synaptogenesis: A combined in vitro and network pharmacology approach. Phytotherapy Research 2022, 36, 2524–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieber, K. Hypoxia and Neuronal Function under in Vitro Conditions. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 1999, 82, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabogal-Guáqueta, A.M.; Osorio, E.; Cardona-Gómez, G.P. Linalool reverses neuropathological and behavioral impairments in old triple transgenic Alzheimer's mice. Neuropharmacology 2016, 102, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.; Shin, M.; Park, Y.; Choi, B.; Jang, S.; Lim, C.; Yun, H.S.; Lee, I.-S.; Won, S.-Y.; Cho, K.S. Linalool Alleviates Aβ42-Induced Neurodegeneration via Suppressing ROS Production and Inflammation in Fly and Rat Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2021, 2021, 8887716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.H.; Hsu, H.T.; Lin, C.C.; An, L.M.; Lee, C.H.; Ko, H.H.; Lin, C.L.; Lo, Y.C. Linalool, a Fragrance Compound in Plants, Protects Dopaminergic Neurons and Improves Motor Function and Skeletal Muscle Strength in Experimental Models of Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandur, E.; Major, B.; Rák, T.; Sipos, K.; Csutak, A.; Horváth, G. Linalool and Geraniol Defend Neurons from Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Iron Accumulation in In Vitro Parkinson’s Models. Antioxidants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.-H.; Hsu, H.-T.; Lin, C.-C.; An, L.-M.; Lee, C.-H.; Ko, H.-H.; Lin, C.-L.; Lo, Y.-C. Linalool, a Fragrance Compound in Plants, Protects Dopaminergic Neurons and Improves Motor Function and Skeletal Muscle Strength in Experimental Models of Parkinson’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.K.; Jung, A.N.; Jung, Y.S. Linalool Ameliorates Memory Loss and Behavioral Impairment Induced by REM-Sleep Deprivation through the Serotonergic Pathway. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2018, 26, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanoue, V.; Cooper, H.M. Branching mechanisms shaping dendrite architecture. Developmental Biology 2019, 451, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, R.; Ascoli, G.A. Quantitative investigations of axonal and dendritic arbors: development, structure, function, and pathology. Neuroscientist 2015, 21, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mączka, W.; Duda-Madej, A.; Grabarczyk, M.; Wińska, K. Natural Compounds in the Battle against Microorganisms—Linalool. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satou, T.; Kamagata, M.; Nakashima, S.; Mori, K.; Yoshinari, M. Effects of Inhaled Linalool on the Autonomic Nervous System in Awake Mice. Natural Product Communications 2024, 19, 1934578X241232273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Chang, S.-T.; Liao, V.H.-C. Potential anti-Parkinsonian's effect of S-(+)-linalool from Cinnamomum osmophloeum ct. linalool leaves are associated with mitochondrial regulation via gas-1, nuo-1, and mev-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Phytotherapy Research 2022, 36, 3325–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).