Submitted:

09 September 2023

Posted:

12 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Preparation of Ethanol Extracts of P. cocos (EEPC)

2.3. Identification and analysis of chemical constituents in EEPC using UHPLC-Q-Exactive-MS/MS

2.4. Cell Culture

2.5. Cytotoxicity Test

2.6. Western Blotting

2.7. Differentiation Assay

2.8. Immunostaining

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. EEPC induces neuronal differentiation and neurite outgrowth in Neuro-2a cells

3.2. EEPC activates JNK1/2/3 during EEPC-induced neuronal differentiation

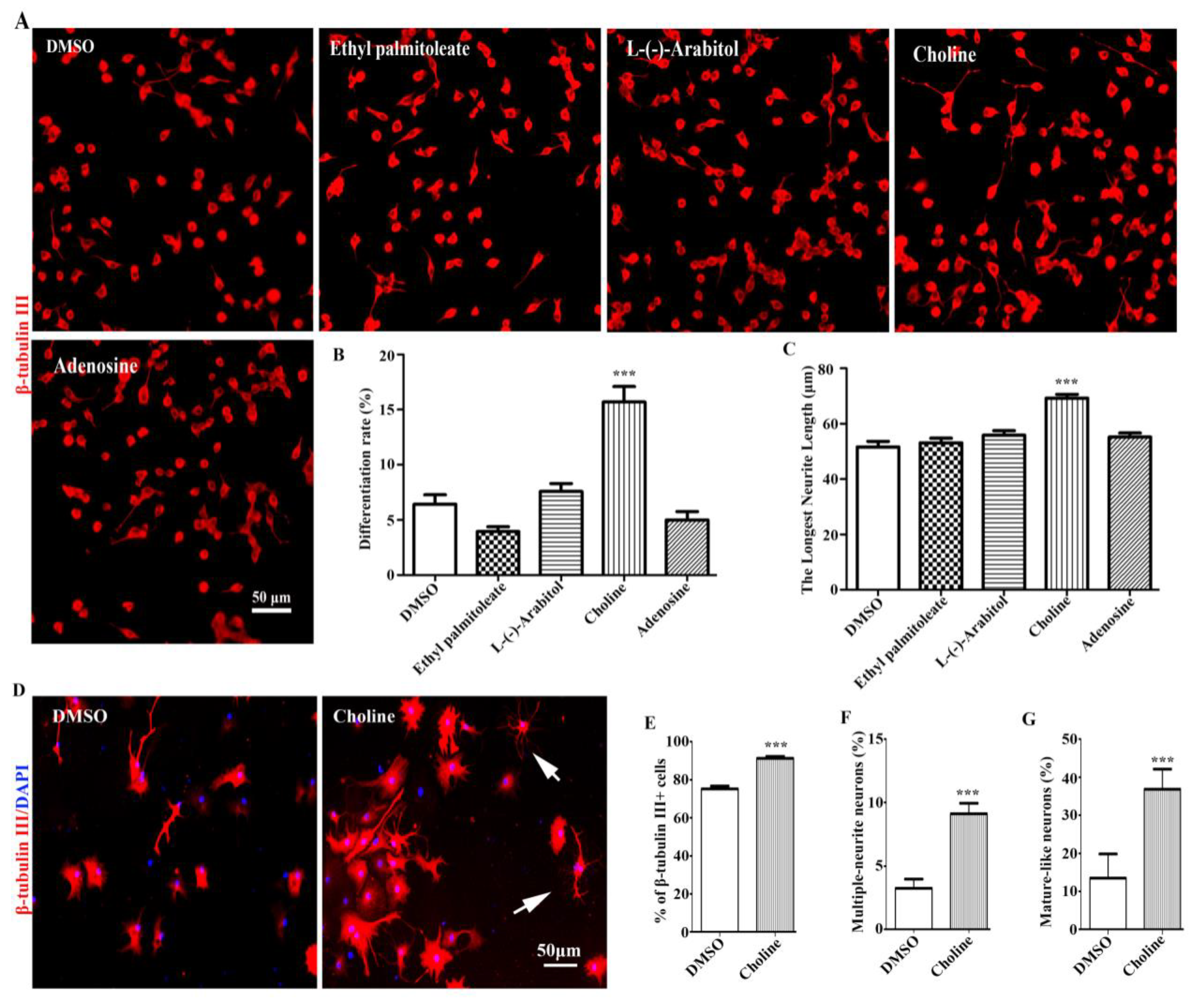

3.3. EEPC Promotes Neuronal Differentiation and Maturation of NSPCs

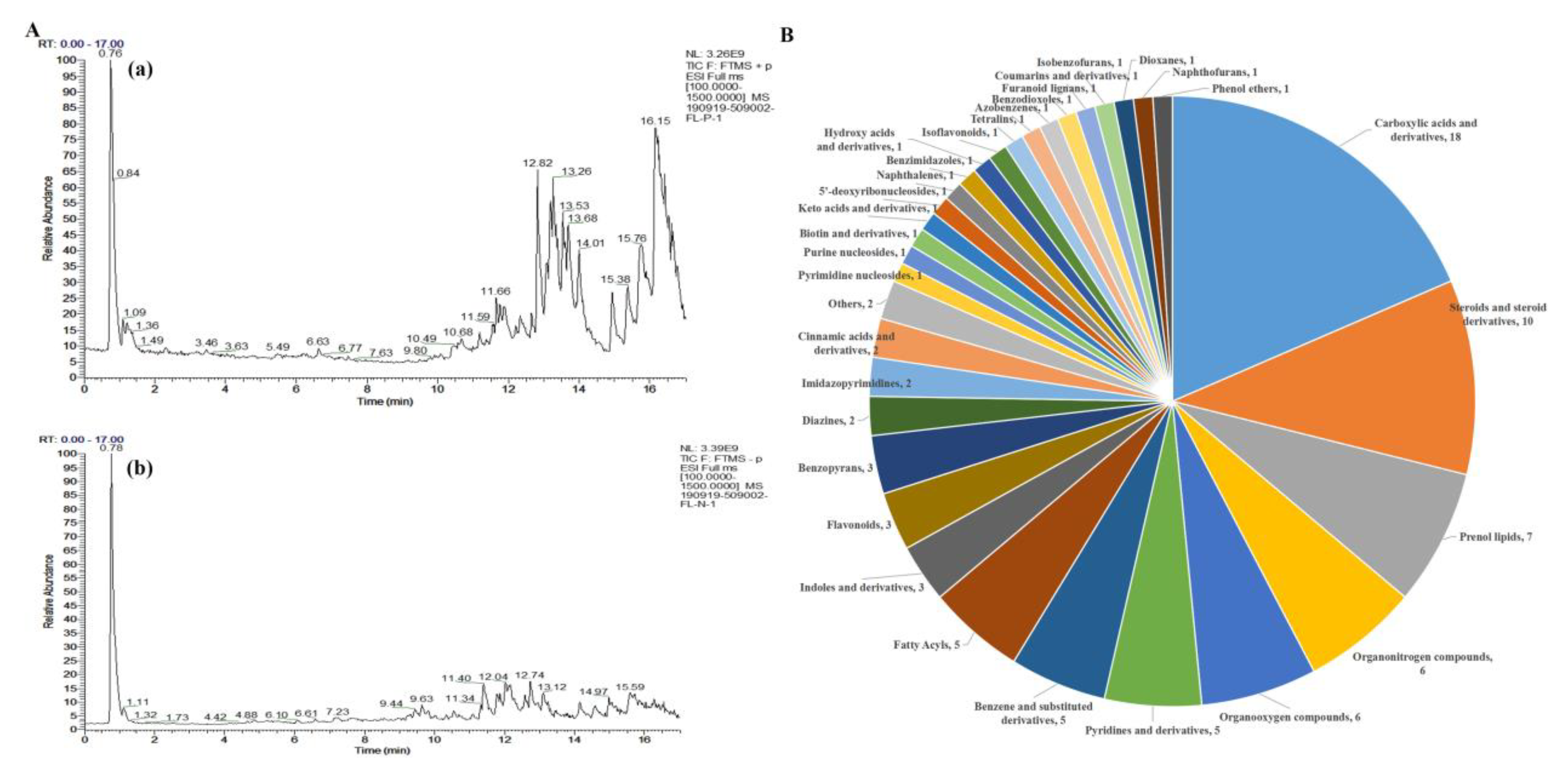

3.4. Identification of the chemical constituents of EEPC extract

3.5. Choline is identified as the major effective component of EEPC

4. Discussion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Gotz, M.; Huttner, W. B. , The cell biology of neurogenesis. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 2005, 6, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehler, M. F.; Gokhan, S. , Developmental mechanisms in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Progress in neurobiology 2001, 63, 337–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, L. M.; Huttner, W. B. , The cell biology of neural stem and progenitor cells and its significance for their proliferation versus differentiation during mammalian brain development. Current opinion in cell biology 2008, 20, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pincus, D. W.; Goodman, R. R.; Fraser, R. A.; Nedergaard, M.; Goldman, S. A. , Neural stem and progenitor cells: a strategy for gene therapy and brain repair. Neurosurgery 1998, 42, 858–867, discussion 867–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, J. W.; Shi, H. Y.; Ma, Y. M. , Neural stem cell therapy for brain disease. World journal of stem cells 2021, 13, 1278–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, X. L.; Jiang, Z. M.; Li, X. F.; Qi, Y.; Yu, J.; Yang, X. X.; Zhang, M. , Quantification of Chemical Groups and Quantitative HPLC Fingerprint of Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf. Molecules 2022, 27, 6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Bi, K.; Luo, X.; Chan, K. , The isolation, identification and determination of dehydrotumulosic acid in Poria cocos. Analytical sciences : the international journal of the Japan Society for Analytical Chemistry 2002, 18, 529–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, J. L.; Andujar, I.; Recio, M. C.; Giner, R. M. , Lanostanoids from fungi: a group of potential anticancer compounds. Journal of natural products 2012, 75, 2016–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, J. L. , Chemical constituents and pharmacological properties of Poria cocos. Planta medica 2011, 77, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. H.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. D.; Duan, Y. T.; Sun, M. J.; Huang, J. J.; Peng, D. Y.; Yu, N. J.; Wang, Y. Y.; Zhang, Y. , Poria cocos polysaccharide prevents alcohol-induced hepatic injury and inflammation by repressing oxidative stress and gut leakiness. Frontiers in nutrition 2022, 9, 963598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C. L.; Paul, C. R.; Day, C. H.; Chang, R. L.; Kuo, C. H.; Ho, T. J.; Hsieh, D. J.; Viswanadha, V. P.; Kuo, W. W.; Huang, C. Y. , Poria cocos (Fuling) targets TGFbeta/Smad7 associated collagen accumulation and enhances Nrf2-antioxidant mechanism to exert anti-skin aging effects in human dermal fibroblasts. Environmental toxicology 2021, 36, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Li, S. L.; Gong, L.; Wang, J. L.; Li, Y. Z.; Wu, Z. H. , The effects of an herbal medicine Bu-Wang-San on learning and memory of ovariectomized female rat. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2008, 117, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Duan, X.; Cheng, X.; Cheng, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, P.; Su, S.; Duan, J. A.; Dong, T. T.; Tsim, K. W.; Huang, F. , Kai-Xin-San, a standardized traditional Chinese medicine formula, up-regulates the expressions of synaptic proteins on hippocampus of chronic mild stress induced depressive rats and primary cultured rat hippocampal neuron. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2016, 193, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J. P.; Feng, L.; Zhang, M. H.; Ma, D. Y.; Wang, S. Y.; Gu, J.; Fu, Q.; Qu, R.; Ma, S. P. , Neuroprotective effect of Liuwei Dihuang decoction on cognition deficits of diabetic encephalopathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2013, 150, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z. J.; Wang, X. H.; Ma, J.; Song, Y. H.; Liang, M.; Lin, S. X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, A. Z.; Li, F.; Hua, Q. , The prescriptions from Shenghui soup enhanced neurite growth and GAP-43 expression level in PC12 cells. BMC complementary and alternative medicine 2016, 16, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia Jiang, Jie Xie, Zhaotun Hu, Xiaoliang Xiang, Ethanol extract of Poria cocos induces apoptosis and differentiation in Neuro-2a neuroblastoma cells. Bangladesh Journal of Pharmacology 2022, 17, 9. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Zhuang, X.; Li, S.; Shi, L. , Arhgef1 is expressed in cortical neural progenitor cells and regulates neurite outgrowth of newly differentiated neurons. Neuroscience letters 2017, 638, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waetzig, V.; Herdegen, T. , The concerted signaling of ERK1/2 and JNKs is essential for PC12 cell neuritogenesis and converges at the level of target proteins. Molecular and cellular neurosciences 2003, 24, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepien, T. , Neurogenesis in neurodegenerative diseases in the adult human brain. Postepy psychiatrii neurologii 2021, 30, 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Peretto, P.; Bonfanti, L. , Adult neurogenesis 20 years later: physiological function vs. brain repair. Frontiers in neuroscience 2015, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L.; Cataudella, T.; Cattaneo, E. , Neural stem cells: a pharmacological tool for brain diseases? Pharmacological research 2003, 47, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K. A.; Kim, J. A.; Kim, S.; Joo, Y.; Shin, K. Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, H. S.; Suh, Y. H. , Therapeutic potentials of neural stem cells treated with fluoxetine in Alzheimer's disease. Neurochemistry international 2012, 61, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grochowski, C.; Radzikowska, E.; Maciejewski, R. , Neural stem cell therapy-Brief review. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery 2018, 173, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, J. D.; Ming, G. L.; Song, H. , Adult neurogenesis as a potential therapy for neurodegenerative diseases. Discovery medicine 2006, 6, 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, S.; Phukan, B. C.; Dutta, A.; Paul, R.; Bhattacharya, P.; Manivasagam, T.; Thenmozhi, A. J.; Babu, C. S.; Essa, M. M.; Borah, A. , Natural Products and Their Therapeutic Effect on Autism Spectrum Disorder. Advances in neurobiology 2020, 24, 601–614. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. W.; Tian, S. J.; de Barry, J.; Luu, B. , Panaxadiol glycosides that induce neuronal differentiation in neurosphere stem cells. Journal of natural products 2007, 70, 1329–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. R.; Kim, J. Y.; Lee, Y.; Chun, H. J.; Choi, Y. W.; Shin, H. K.; Choi, B. T.; Kim, C. M.; Lee, J. , PMC-12, a traditional herbal medicine, enhances learning memory and hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. Neuroscience letters 2016, 617, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Gao, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. , Effects of Dangshen Yuanzhi Powder on learning ability and gut microflora in rats with memory disorder. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2022, 296, 115410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Liu, J.; Li, N.; Liu, M.; Luo, Z.; Li, H. , Traditional Chinese Medicine Shenmayizhi Decoction Ameliorates Memory and Cognitive Impairment Induced by Multiple Cerebral Infarctions. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM 2021, 2021, 6648455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J. M.; Li, S. Y.; He, W. , [Effects of one Chinese herbs on improving cognitive function and memory of Alzheimer's disease mouse models]. Zhongguo Zhong yao za zhi = Zhongguo zhongyao zazhi = China journal of Chinese materia medica 2003, 28, 751–754. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K. J.; Chen, Y. F.; Tsai, H. Y.; Wu, C. R.; Wood, W. G. , Guizhi-Fuling-Wan, a Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine, Ameliorates Memory Deficits and Neuronal Apoptosis in the Streptozotocin-Induced Hyperglycemic Rodents via the Decrease of Bax/Bcl2 Ratio and Caspase-3 Expression. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM 2012, 2012, 656150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, L.; Li, P.; Zhao, J.; Duan, J. , Antidepressant and immunosuppressive activities of two polysaccharides from Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf. International journal of biological macromolecules 2018, 120 Pt B, 1696–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Q.; Di, X.; Bian, B.; Li, K.; Guo, J. , Neuroprotective Effects of Poria cocos (Agaricomycetes) Essential Oil on Abeta1-40-Induced Learning and Memory Deficit in Rats. International journal of medicinal mushrooms 2022, 24, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Tang, G.; Yang, J.; Ding, J.; Lin, H.; Xiang, X. , Synthesis of some new acylhydrazone compounds containing the 1,2,4-triazole structure and their neuritogenic activities in Neuro-2a cells. RSC advances 2020, 10, 18927–18935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, C. B. , An introduction to the nutrition and metabolism of choline. Central nervous system agents in medicinal chemistry 2012, 12, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, E.; Obeid, R. , Choline, Neurological Development and Brain Function: A Systematic Review Focusing on the First 1000 Days. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudill, M. A. , Pre- and postnatal health: evidence of increased choline needs. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2010, 110, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, T. W.; von Hohenberg, W. C.; Kaus, O. R.; Lanier, L. M.; Georgieff, M. K. , Choline Supplementation Partially Restores Dendrite Structural Complexity in Developing Iron-Deficient Mouse Hippocampal Neurons. The Journal of nutrition 2022, 152, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tees, R. C. , The influences of rearing environment and neonatal choline dietary supplementation on spatial learning and memory in adult rats. Behavioural brain research 1999, 105, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudd, A. T.; Getty, C. M.; Sutton, B. P.; Dilger, R. N. , Perinatal choline deficiency delays brain development and alters metabolite concentrations in the young pig. Nutritional neuroscience 2016, 19, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez, R.; Ash, J. A.; Powers, B. E.; Kelley, C. M.; Strawderman, M.; Luscher, Z. I.; Ginsberg, S. D.; Mufson, E. J.; Strupp, B. J. , Maternal choline supplementation improves spatial learning and adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Neurobiology of disease 2013, 58, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blusztajn, J. K.; Mellott, T. J. , Choline nutrition programs brain development via DNA and histone methylation. Central nervous system agents in medicinal chemistry 2012, 12, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Nagakura, T.; Uchino, H.; Inazu, M.; Yamanaka, T. , Functional Expression of Choline Transporters in Human Neural Stem Cells and Its Link to Cell Proliferation, Cell Viability, and Neurite Outgrowth. Cells 2021, 10, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NO. | Name | Formula | Class | M.W. | RT [min] | Relative proportion (1%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Choline | C5 H13NO | Organonitrogen compounds | 103.09982 | 0.769 | 17.75 |

| 2 | L-Glutamic acid | C5H9NO4 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives | 147.05274 | 0.79 | 1.14 |

| 3 | N,N-Diethylethanolamine | C6H15NO | Organonitrogen compounds | 117.11529 | 0.797 | 2.20 |

| 4 | Betaine | C5H11NO2 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives | 117.0789 | 0.809 | 1.82 |

| 5 | Trigonelline | C7H7NO2 | Pyridines and derivatives | 137.04733 | 0.813 | 2.46 |

| 6 | L-(-)-Arabitol | C5H12O5 | Organooxygen compounds | 152.06812 | 0.82 | 6.51 |

| 7 | Cytosine | C4H5N3O | Diazines | 111.0433 | 0.837 | 1.81 |

| 8 | Cytidine | C9H13N3O5 | Pyrimidine nucleosides | 243.0849 | 0.84 | 1.01 |

| 9 | Adenosine | C10H13 N5O4 | Purine nucleosides | 267.09604 | 1.243 | 7.23 |

| 10 | Acetophenone | C8H8O | Organooxygen compounds | 120.05739 | 1.321 | 1.14 |

| 11 | Leucine | C6H13NO2 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives | 131.0944 | 1.36 | 2.53 |

| 12 | L-Phenylalanine | C9H11NO2 | Carboxylic acids and derivatives | 165.07866 | 2.292 | 1.50 |

| 13 | Phenylacetylene | C8H6 | Benzene and substituted derivatives | 102.0469 | 2.292 | 1.46 |

| 14 | Picolinic acid | C6H5NO2 | Pyridines and derivatives | 123.03191 | 3.231 | 1.02 |

| 15 | Triphenylphosphine oxide | C18H15OP | Benzene and substituted derivatives | 278.0851 | 10.705 | 3.17 |

| 16 | 2-Amino-1,3,4-octadecanetriol | C18H39NO3 | Organonitrogen compounds | 317.29191 | 11.185 | 3.17 |

| 17 | (3β,5ξ,9ξ)-3,6,19-Trihydroxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid | C30H48O5 | Prenol lipids | 488.34864 | 11.697 | 9.67 |

| 18 | Bis(4-ethylbenzylidene)sorbitol | C24H30O6 | Dioxanes | 414.20291 | 11.918 | 2.50 |

| 19 | 18-β-Glycyrrhetinic acid | C30H46O4 | Prenol lipids | 470.33821 | 13.044 | 1.05 |

| 20 | Ethyl palmitoleate | C18H34O2 | Fatty Acyls | 282.25502 | 14.152 | 5.42 |

| 21 | 3-Acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid | C32H48O5 | Prenol lipids | 512.34893 | 14.93 | 2.90 |

| 22 | 4-Methoxycinnamic acid | C10H10O3 | Cinnamic acids and derivatives | 178.06257 | 16.726 | 1.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).