1. Introduction

Currently, the exponential growth of Internet of Things (IoT) networks and their applications is radically transforming various sectors, from home automation to device monitoring in Industry 4.0. This surge in connectivity brings with it a significant increase in the quantity and variety of data generated, which poses new challenges in terms of security and privacy. Defining and implementing suitable security protocols is crucial to protect these data against unauthorized access and to ensure the principle of security in IoT network architectures [

1][

2].

Due to the fact that IoT devices often include devices with limited computational and energy capacities, traditional security protocols may not be suitable or efficient for their implementation in these environments due to their high complexity. The diversity of applications and devices within IoT networks demands a flexible and adaptable approach that can meet specific security requirements. This implies not only the protection of data transmission but also security in data storage and processing, critical elements for maintaining the trust and continuous functionality of IoT applications.

Despite advances in security technologies, current protocols face significant limitations in the IoT context. Many of these protocols were not specifically designed for IoT environments and therefore may not function optimally in networks of low-power devices or with bandwidth limitations. The need for simplified configuration and management, essential for IoT devices that often lack advanced user interfaces, presents an additional challenge that can compromise security by not allowing detailed adjustments or requiring trade-offs between ease of use and security strength. Moreover, scalability is another significant problem; protocols must be able to adapt efficiently to networks that can rapidly grow in the number of devices without degrading overall system performance. Most current security protocols are not designed to efficiently handle the dynamics of a constantly expanding network, which can result in bottlenecks and failure points that compromise the security of the entire network.

In this context, Owl presents itself as a promising solution to overcome these limitations by integrating a password-authenticated key-exchange protocol. Its design focuses on efficiency and low resource demand, making it ideal for devices with limited capabilities, typical of many IoT applications. Owl allows two parties to establish a high-entropy session key based solely on a low-entropy shared secret stored through a one-way transformation, thus significantly reinforcing security in vulnerable and dynamic environments [

3].

The main goal of this article is to evaluate which IoT application protocols natively lack a key-exchange method to initiate a secure session and to determine how integration with Owl can reinforce security from the start of the communication session. By doing this, we aim to strengthen IoT application protocols to natively include defined and secure steps to establish a session through key exchange, ensuring that security is not only applied as an external layer, but is integrated into the very structure of IoT communication. The article is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the state-of-the-art in IoT security, highlighting protocol vulnerabilities and cryptographic advances.

Section 3 defines the integration criteria for Owl that assess efficiency, security, and scalability.

Section 4 presents the Owl-CoAP integration architecture, detailing key exchange and authentication mechanisms.

Section 5 explores the enhancement of entropy to enhance CoAP security.

Section 6 evaluates performance through experimental analysis, measuring computational overhead and authentication latency. Finally,

Section 7 concludes with insight into the strengthening of IoT protocols and future research directions.

2. State of the Art

The security in IoT is undergoing a transformation with the implementation of cryptographic advances designed to address emerging challenges in critical sectors such as remote healthcare and automated urban infrastructures. The evolution and adaptation of established protocols, such as MQTT and CoAP, have been fundamental in this metamorphosis, facilitating the integration of security as an intrinsic element rather than a subsequent solution. MQTT, in particular, has stood out by implementing improvements that strengthen authentication and encryption, which is vital in a landscape where efficiency and security must coexist without mutual compromise. These advances in security not only increase the resilience of systems against unauthorized access and cyber threats, but also increase confidence in the adoption of IoT technologies for applications that are essential for daily life and the well-being of individuals [

4].

The progress of MQTT in IoT security reflects the constant evolution and significant advances in cryptography in this area. In facing the challenge of protecting an increasingly complex and dispersed network, MQTT has adapted with advanced cryptographic solutions that meet the growing demands of a diversified IoT environment. In addition, the management of sessions and innovative authentication techniques based on tokens and digital certificates have increased the level of security available for IoT applications. These developments have solidified MQTT not only as an efficient medium of communication but also as a secure standard for the transmission of sensitive data in critical applications, where a security breach is not an option [

5].

Moreover, protocols such as CoAP, employing DTLS, have set a precedent in the secure management of IoT devices on a large scale. Adaptability is a distinctive characteristic of these solutions, allowing for precise implementation in various scenarios, from home networks to complex industrial systems. Zigbee, with its AES encryption and shared key schemes, along with LoRaWAN and Sigfox, which have developed security solutions specific to low-bandwidth capacity environments, reflect how security significantly varies depending on the application context. These protocols not only secure data transmission, but also reinforce the association phase and strengthen the network against unauthorized access [

6].

In the context of Industry 4.0, the implementation of native security in long-range industrial sensor network protocols is fundamental. Zigbee and LoRaWAN protocols are exemplary in this regard, having significantly advanced their cryptographic approaches [

7].

Zigbee has enriched its protocol with dynamic key renewal techniques, providing robust defense against sustained attacks while adapting to emerging threats. On the other hand, LoRaWAN has integrated unique application keys for each device, favoring an individualized encryption approach that allows for personalized and flexible security for each node in the network. These developments are not only reactive but proactive, ensuring that the network is not only resilient to current threats but also prepared to adapt to the constantly evolving needs and vulnerabilities in the industrial realm. The integration of these cryptographic capabilities into the intrinsic design of communication protocols underscores the importance of a solid and adaptable security foundation that is crucial to the success and sustainability of operations in Industry 4.0 [

8].

The convergence of protocols such as NB-IoT, CAT-LTE, and LTE-M represents a milestone in IoT security, especially with respect to their application in extensive action areas that range from monitoring critical infrastructures to intelligent resource management. NB-IoT has established itself as an effective solution for connectivity in vast areas with low bandwidth requirements, with its standard 3GPP encryption being a critical component for maintaining security in wide-reaching cellular networks. This protocol is particularly relevant in applications where signal durability and penetration are essential, such as in the monitoring of public utilities and agricultural sensors [

9].

However, CAT-LTE emerges as a favored option in environments demanding higher data transfer speeds, balancing energy efficiency with high-quality performance. The built-in security of this protocol addresses the growing concern for cyber risks in sectors such as automotive and telehealth, where data integrity can have direct implications on human safety and health [

10].

LTE-M, with its ability to provide mobility and voice communications, extends to dynamic applications such as vehicle tracking and real-time fleet management. This protocol optimizes spectrum use and connectivity on the move, with a focus on security that supports applications requiring low latency and continuous, reliable communication.

In each of these protocols, security is not an afterthought, but a primary consideration integrated from the design’s inception. The implementation of robust cryptographic standards and advanced key management has become indispensable to protect against evolving threats and support the scalability of IoT networks. These advancements in protocol security reflect a proactive and anticipatory approach, ensuring that networks are not only secure in the present but are also equipped to adapt to future challenges in an ever-changing technological landscape.

At the frontier of IoT technology, emerging cryptographic algorithms redefine security and operational efficiency in the context of Industry 4.0. Innovations such as J-PAKE, OPAQUE, and Owl are designed not only to meet current demands, but also to be flexible in the face of future challenges in a constantly changing IoT environment. These technologies represent a qualitative leap in the way secure communications are established, particularly in contexts where traditional cryptographic structures might not be applicable [

11].

J-PAKE and OPAQUE contribute advanced authentication strategies that preserve user privacy and the integrity of the process. J-PAKE, using zero-knowledge, avoids the need to transmit secret keys, maintaining security even when the communication channel’s security is not guaranteed. OPAQUE further strengthens the authentication process, ensuring that user credentials remain protected against exposure, even during the authentication process [

12].

Owl stands as a revolutionary protocol in IoT security, providing mutual authentication through a process that uses low-entropy passwords, which is fundamental in low-end devices. In the realm of PAKE protocols, Owl excels in its ability to generate high-entropy keys from these simple passwords, allowing parties to authenticate each other securely and efficiently. This technique contrasts with more computationally expensive authentication methods, such as RSA asymmetric encryption, which is less practical on devices with limited resources.

Owl provides an efficient alternative in critical scenarios by using the simpler, less demanding symmetric encryption protocol like PAKE, enhancing IoT protocol robustness and leading new standards. Its implementation improves proactive defenses and adapts to new vulnerabilities, making these protocols central to the next generation of IoT systems, securing diverse environments, from smart cities to industrial setups. As shown in

Table 1, Owl’s approach to key exchange stands out compared to other IoT security protocols, particularly those that lack native mechanisms for establishing secure sessions. By addressing these gaps, Owl enhances authentication, scalability, and overall resilience in constrained environments, providing a lightweight but robust security solution for modern IoT deployments.

3. Integration Criteria for IoT Protocols in Owl Protocol

To determine the most suitable protocol for integration with Owl, we consider the following essential criteria:

Operational Efficiency and Resource Requirements: Prefer a protocol that requires low computational complexity and is efficient in resource management, especially in IoT environments with devices with limited capabilities.

Security and Encryption Handling: The protocol’s ability to integrate robust security measures without complex reconfigurations, using mechanisms such as TLS or DTLS to ensure the protection of transmitted data.

Adaptability and Scalability: Importance of the protocol being able to handle a large number of devices and adapt to the expansion and dynamism needs of physical medium access and the IoT environment.

Now, the careful selection of protocols such as MQTT, CoAP, Zigbee, LoRa, BLE, Z-Wave, NB-IoT, LTE-M, and Sigfox for integration with advanced systems like Owl is extensively justified by their strategic adaptation to the specific demands of the IoT industry. These protocols not only stand out for their unique capabilities, but are also aligned with emerging trends and critical requirements for robustness, efficiency, and security in various industrial sectors. This alignment ensures that integration with systems like Owl is not only technically and functionally sound but also strategically advantageous, maximizing the return on investment and ensuring scalability and security in complex and evolving IoT environments.

3.1. MQTT

Integration Inefficiency: Although MQTT effectively handles real-time communications, its dependence on TCP/IP and the need to handle security in multiple layers through TLS may complicate its integration with systems like Owl that require flexibility in intermittent or dynamic networks. Furthermore, the centralized broker architecture can be a bottleneck and a single point of failure, which is not ideal in critical applications that require high availability and distributed security [

27].

3.2. CoAP

Integration Challenges: CoAP itself does not define specific methods for session key exchange. Instead, CoAP can be configured to use transport-level security via DTLS or apply additional security layers such as digital certificates or preshared keys. DTLS supports various key exchange mechanisms, including RSA, ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography), and PSK (Pre-Shared Keys) [

28].

3.3. Zigbee and LoRa

Redundancy and complexity: The robust security implementation in Zigbee and LoRa, especially AES encryption and network management specific to mesh and LPWAN, may not require the advanced authentication features offered by Owl, leading to redundancy that could complicate and not improve the existing infrastructure under the link layer. This could result in additional complexity and resource overhead without clear benefits [

29,

30].

3.4. BLE and Z-Wave

Limited Security Enhancement: Since BLE and Z-Wave already have effective security mechanisms for their short-range applications and personal devices, integration with Owl may not provide significant improvements. BLE employs a pairing process that includes key exchange to establish an encrypted connection. This is done through various pairing methods such as Just Works, Passkey Entry, and Out-of-Band (OOB). Regarding Z-Wave, in its Z-Wave S2 version, it includes measures to ensure that only verified and authenticated devices can join the network, using a process called DSK (Device Specific Key) to confirm the identity of the devices during inclusion [

31,

32].

3.5. NB-IoT and LTE-M

Redundancy in Security Layers: These protocols use robust security layers provided by cellular network operators, including the use of a SIM card for authentication, specifically designed to meet telecommunications standards. The integration of Owl could duplicate these security layers, adding complexity without a proportional increase in protection or functionality, which is inefficient, especially in terms of energy consumption and network management [

33].

3.6. Sigfox

Communication Limitations: Sigfox’s architecture, oriented towards unidirectional or limited bidirectional transmission of small amounts of data, makes integration with Owl practically unfeasible. Owl, designed for secure and dynamic authentications, would require a richer bidirectional interaction that Sig fox simply cannot efficiently support[

34].

The diversity in the design of IoT protocols reflects the specificity of each for certain operational environments, from energy efficiency to geographical extension. Ideally, Owl integration should enrich existing capabilities without overburdening systems with superfluous technical complexities. This evaluation indicates that, while several protocols could benefit from integration with Owl in theory, CoAP stands out as the most optimal candidate. CoAP not only has an architecture that effectively supports Owl’s signaling but also facilitates registration and efficient management of nodes through its middleware. This protocol, characterized by its lightweight and efficient nature, and its advanced security implementation through DTLS, positions it as an ideal complement to Owl, especially in IoT applications requiring agile and robust security management [

34].

3.7. Complementarity of Owl and CoAP

Orientation towards IoT: Both Owl and CoAP are designed for IoT environments. Owl provides a secure authentication and key-establishing mechanism, while CoAP offers a lightweight application layer protocol for communication between IoT devices with limited resources. Enhanced security: Integrating Owl with CoAP could significantly enhance security in communication between IoT devices. Owl can securely handle key exchange and authentication, while CoAP, especially when combined with DTLS or OSCORE, ensures that data in transit is secured at the application or transport layer. Interoperability: Using Owl for authentication and key exchange and CoAP for regular communication between devices, the strengths of both protocols can be leveraged, thus maximizing interoperability within a diverse IoT environment.

3.8. Integration Considerations

Security Implementation: It will be crucial to correctly implement security mechanisms in both protocols. For example, ensuring that the key exchange performed by Owl and data communication through CoAP are protected against external attacks. Resource Management: Although both protocols are designed to be efficient in resource usage, integration must carefully manage system resource consumption to avoid overloading IoT devices with limited capabilities. Configuration and Management: The configuration of the integration between Owl and CoAP should be managed in a way that simplifies both initial implementation and long-term management, including the update and renewal of the key and security certificate. Rigorous Testing: It is essential to conduct thorough testing to ensure that integration is not only secure but also stable and capable of handling anticipated use scenarios without failures.

4. Integration Criteria for IoT Protocols in Owl Protocol

To determine the most suitable protocol for integration with Owl, we consider the following essential criteria:

Operational Efficiency and Resource Requirements: Prefer a protocol that requires low computational complexity and is efficient in resource management, especially in IoT environments with devices with limited capabilities.

Security and Encryption Handling: The protocol’s ability to integrate robust security measures without complex reconfigurations, using mechanisms such as TLS or DTLS to ensure the protection of transmitted data.

Adaptability and Scalability: The importance of the protocol being able to handle a large number of devices and adapt to the expansion and dynamism needs of physical medium access and the IoT environment.

By considering these criteria, protocols like MQTT, CoAP, Zigbee, LoRa, BLE, Z-Wave, NB-IoT, LTE-M, and Sigfox can be evaluated for integration with Owl. Although all of these protocols have different features, the goal is to identify the one that aligns best with the characteristics of Owl, ensuring secure, efficient, and scalable communication within IoT environments.

4.1. MQTT

MQTT effectively handles real-time communications, but its dependence on TCP/IP and its reliance on multiple security layers, such as TLS, can make integration with Owl challenging. The centralized broker architecture introduces a single point of failure, which can hinder high availability and distributed security.

4.2. CoAP

CoAP, in its current form, does not define specific methods for session key exchange. However, CoAP is often used with DTLS or OSCORE to provide secure communication. Its lightweight nature and REST-based design make it a promising candidate for Owl integration.

4.3. Zigbee and LoRa

Zigbee and LoRaWAN offer robust security implementations: AES encryption, shared key schemes, and other mesh or LPWAN security features that may make additional enhancements based on Owl redundant. These protocols already incorporate robust link layer security mechanisms, which could lead to unnecessary complexity if combined with Owl.

4.4. BLE and Z-Wave

Both BLE and Z-Wave have established security protocols tailored to short-range communication. BLE uses a pairing process with key exchange methods like Just Works and PassKey Entry, while Z-Wave S2 employs device-specific keys (DSKs). These built-in mechanisms may diminish the value of integrating Owl for these scenarios.

4.5. NB-IoT and LTE-M

These cellular-based protocols are based on operator-managed security features, including SIM-based authentication. Adding Owl could duplicate existing layers, introducing complexity without significant security benefits.

4.6. Sigfox

Sigfox’s unidirectional or limited bidirectional transmission architecture is not well-suited to Owl’s dynamic, interactive authentication processes. The limited communication capability of Sigfox devices does not align with the Owl mutual authentication and key exchange requirements.

5. OWL-CoAP Integration Architecture with Secure Provisioning

The Integration of OWL (

Owl: An Augmented Password-Authenticated Key Exchange Scheme) with CoAP (

Constrained Application Protocol) allows a secure and efficient communication solution for IoT environments, particularly for resource-constrained devices. This section details the proposed architecture divided into main components, communication flow, and an analysis of its advantages. **As shown in

Table 2, the integration relies on well-defined security components, including key provisioning, session management, protocol adaptation, and DTLS-based encryption. The structured communication flow described in

Table 3 ensures secure message transmission, while the advantages summarized in

Table 4 highlight the efficiency, security, and scalability that OWL brings to IoT networks.**

5.3. Analysis and Advantages

The integration of the OWL protocol with CoAP and DTLS provides a comprehensive security framework tailored for resource-constrained IoT environments. Using OWL’s efficient key-exchange mechanisms and CoAP’s lightweight communication model, this architecture ensures secure, scalable, and low-overhead authentication and data transmission. The modular design of CoAP, complemented by the robust encryption options offered by DTLS, facilitates seamless interoperability with existing IoT infrastructures. Through structured provisioning, efficient session management, and enhanced security measures, this integration addresses key challenges in IoT security while maintaining optimal resource utilization. This approach not only mitigates authentication vulnerabilities, but also establishes a resilient foundation for secure and efficient IoT communications.

6. Entropy Augmentation in CoAP: Enhancing Security Through Optimized Computational Efficiency

The OWL protocol (Owl: An Augmented Password-Authenticated Key Exchange Scheme) introduces advanced mechanisms to enhance entropy within the CoAP (Constrained Application Protocol) ecosystem, optimizing the balance between robust security and computational efficiency. This integration is particularly crucial in IoT and resource-constrained environments, where devices operate with limited processing capabilities, but demand strong cryptographic protections to prevent unauthorized access and data breaches. In alignment with the lightweight nature of CoAP, OWL enhances its authentication and session initiation processes while minimizing computational overhead.

During the registration phase, OWL securely interacts with CoAP to establish initial trust. The user computes and transmits the derived values based on their credentials, while the server challenges the user with a zero-knowledge proof mechanism (ZKP) to confirm possession of the secret information without exposing it. This ensures that sensitive data remain confidential, even in constrained network conditions typical of CoAP-based deployments. In the log-in phase, the protocol verifies that the generated session key corresponds to the one derived during registration, allowing secure mutual authentication within the restricted CoAP message structure.

For password updates, the protocol incorporates enhanced security measures tailored to the lightweight requirements of CoAP. The process begins with the user initiating a password change request authenticated through their current credentials. The server issues a new ZKP-based challenge, ensuring that the user still possesses the original secret without transmitting it over the network. The user computes a new password-derived value locally, using the existing salt and cryptographic hash functions, and securely transmits it to the server. The server validates the new credentials against the existing parameters and, upon successful verification, updates its stored values while securely invalidating the old ones. This process ensures that password updates are resistant to interception, replay attacks, and computational inefficiencies.

Each of these phases, registration, login, and password updates, will be further detailed, with a focus on their interaction with CoAP and their reliance on cryptographic techniques such as hashing and zero-knowledge proofs. The seamless integration of the OWL protocol with CoAP ensures a secure, efficient and lightweight solution for authentication in constrained environments, reinforcing the integrity and confidentiality of user credentials.

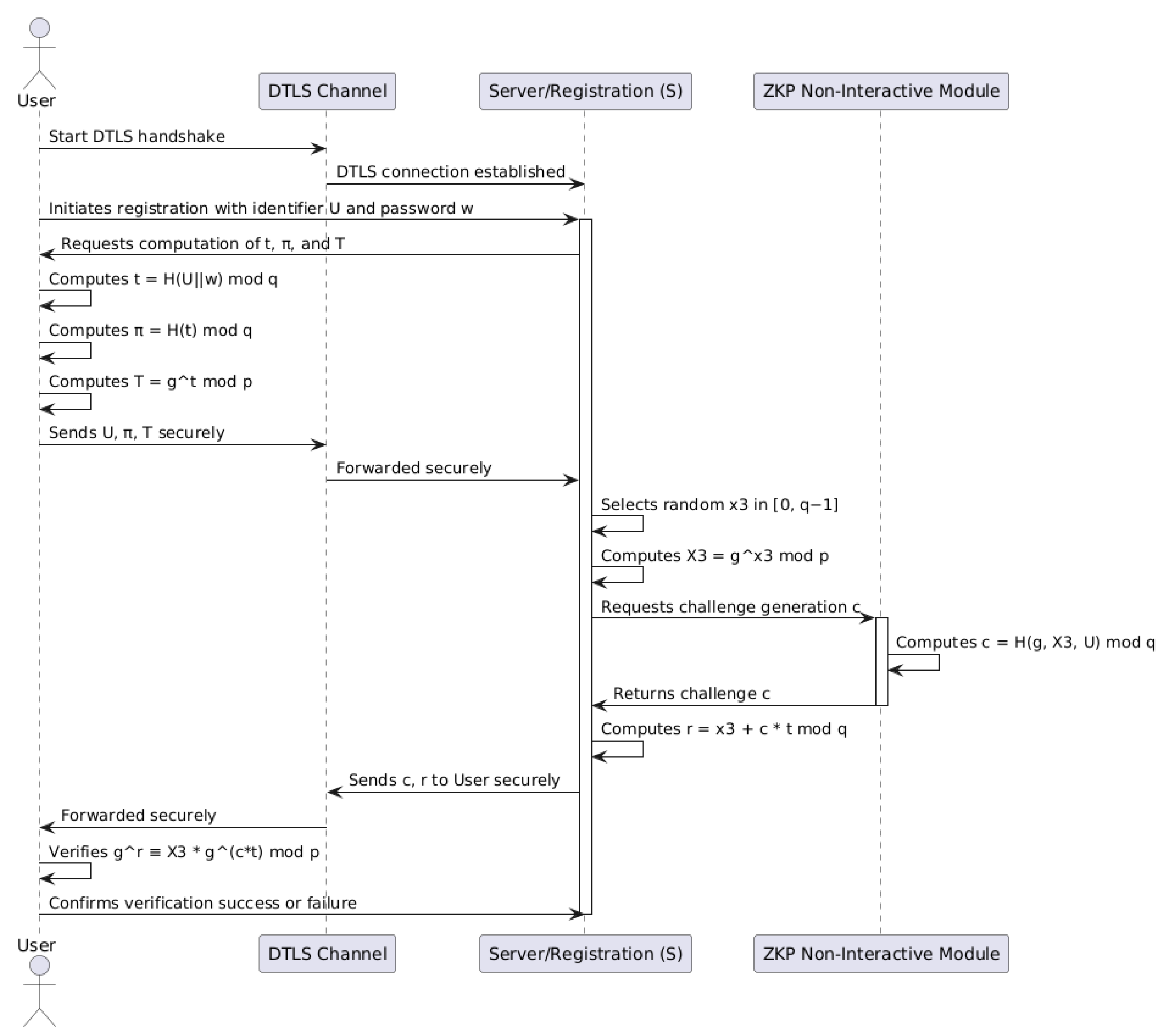

6.1. OWL Registration Process with DTLS in CoAP

The OWL protocol, when integrated with DTLS, provides a robust framework for secure authentication in CoAP-based systems, particularly in IoT environments with constrained devices. During the registration process, the OWL leverages cryptographic hash functions to derive intermediate values from weak passwords provided by users. The process begins by computing:

where

H is a secure hash function,

U is the user identifier, and

w is the password. This is followed by the following computation:

enhancing resistance to dictionary attacks. Finally, the verifier is securely stored on the server as:

These steps effectively increase the entropy of authentication parameters while maintaining compatibility with constrained devices, a critical feature of CoAP.

The interaction between the client and the server during the registration and session establishment is further secured by DTLS, which provides encryption for transmitted data and protects against eavesdropping and tampering. For example, the server generates an ephemeral private key

and computes its corresponding public key:

To authenticate the client without exposing sensitive data, the server issues a Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP) challenge

c, calculated as:

The client responds by calculating:

allowing both parties to verify the relationship:

This process ensures mutual authentication while preserving the confidentiality of private keys. See

Figure 1.

In addition, OWL employs ephemeral private keys (

) and their corresponding public keys (

) to establish secure session keys. Zero-Knowledge Proofs (

) are used to verify the ownership of these keys without revealing their values. During the session key agreement phase, the value

is calculated using contributions from both the user and server keys:

ensuring that the derived session key reflects the input of both parties. A ZKP associated with

, denoted as:

Validates its correctness without exposing private keys.

The integration of OWL with DTLS enhances CoAP by providing secure, high-entropy session keys derived from passwords and preconfigured materials. DTLS ensures the confidentiality and integrity of transmitted data, complementing OWL’s ability to prevent identity spoofing attacks. Moreover, the lightweight operations of OWL, optimized for multiplicative groups and elliptic curves, make it particularly suitable for real-time applications in the Internet of Things (IoT).

The transcript of all messages exchanged during a session, secured by DTLS, guarantees consistency between the client and the server, reducing the risk of communication discrepancies. This log includes key parameters such as public keys, challenges, responses, and session details, providing a comprehensive record to verify session integrity.

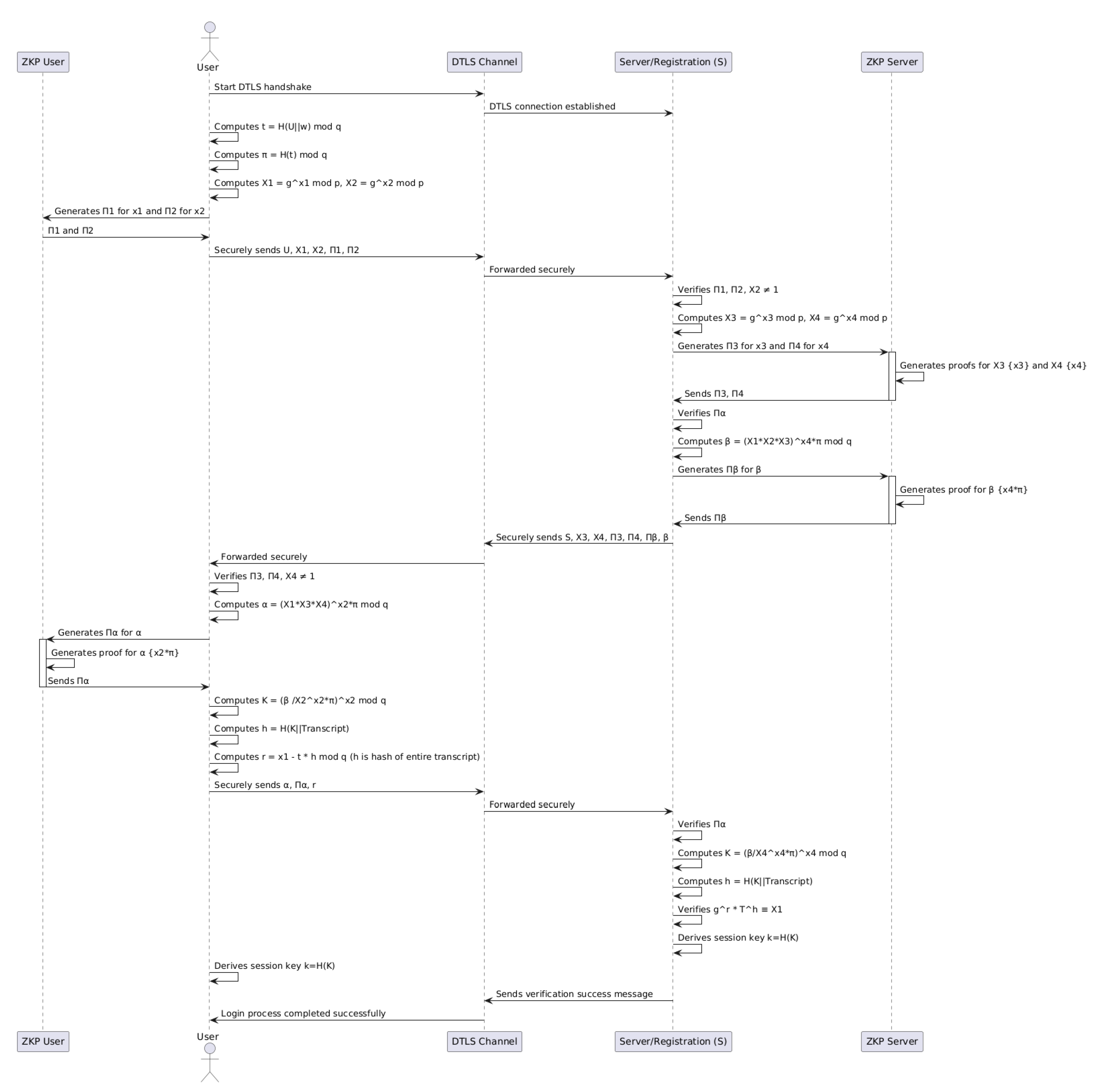

6.2. OWL Login Process with DTLS in CoAP

The OWL protocol, combined with DTLS, ensures robust mutual authentication and secure session establishment within CoAP-based systems. This integration is particularly advantageous in IoT environments where constrained devices require efficient yet secure communication protocols. The following outline the main steps of the log-in process.

6.2.1. User Initialization

The user computes the following values:

where

U is the username, and

w is the password.

enhancing resistance to dictionary attacks.

Public keys are computed as:

based on ephemeral private keys

and

.

The user generates Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKP) and to prove ownership of and without revealing them. The user sends to the server, encrypted and secured using DTLS.

6.2.2. Server Validation

The server decrypts the data using DTLS and verifies the received ZKPs

and

, ensuring

. The server generates its own ephemeral public keys:

based on its private keys

and

. The server produces ZKPs

and

to prove ownership of

and

.

The server calculates a shared value for session key establishment:

and generates

, a ZKP to validate

.

6.2.3. Server Sends Validation Data

The server sends to the user over a secure DTLS channel.

6.2.4. User Validation and Key Computation

The user verifies

and

, ensuring

. The user computes:

as the session key.

where the transcript includes all messages exchanged.

a response value based on the session hash.

The user generates , a ZKP to prove the correctness of , and sends to the server through DTLS.

6.2.5. Server Key Validation and Session Establishment

The server verifies

and computes:

as the session key.

The server verifies:

confirming the user response.

Both the user and the server compute:

the final shared session key.

The integration of DTLS into the OWL login process ensures encrypted message exchanges, further enhancing confidentiality and integrity. See

Figure 2.

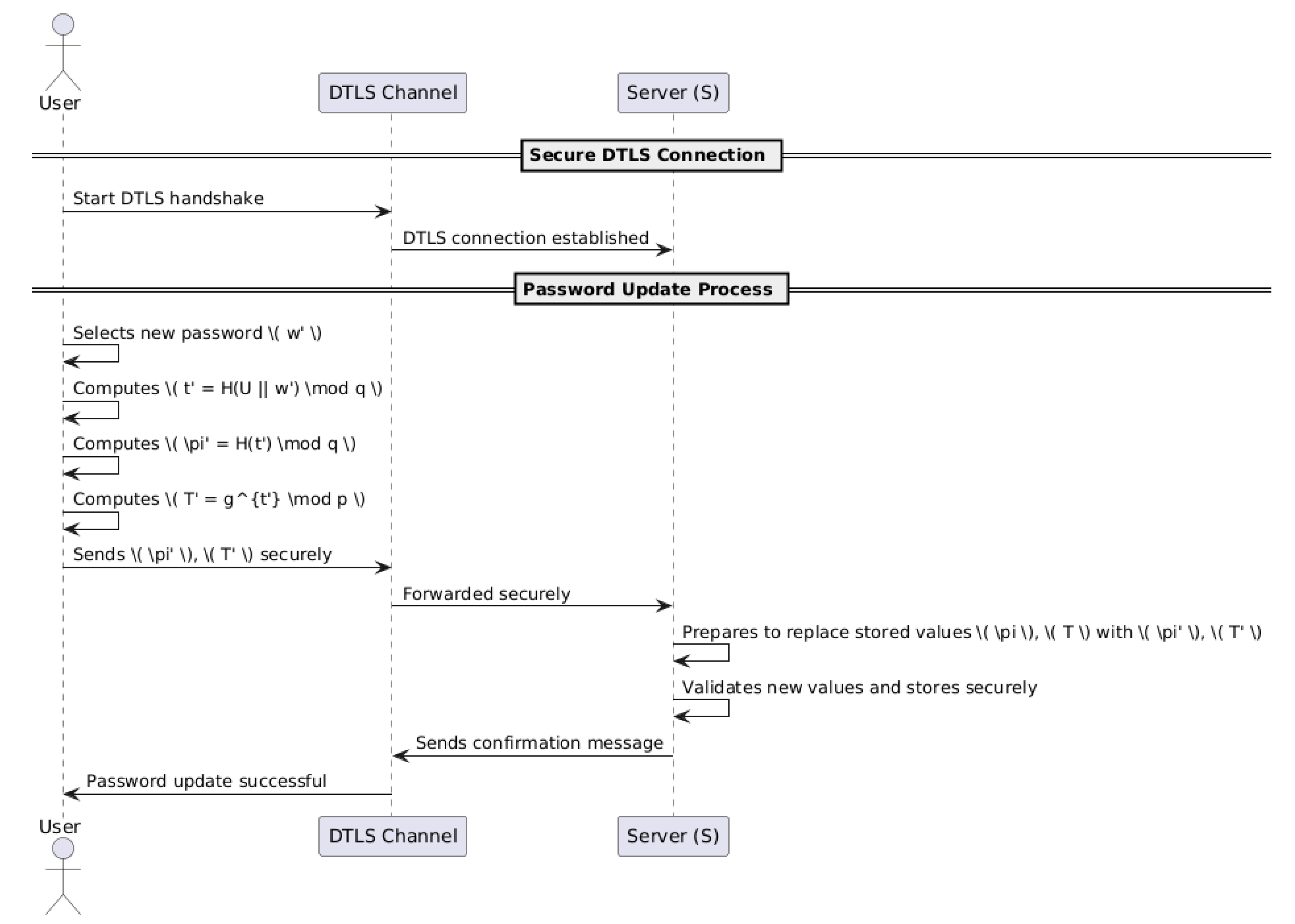

6.3. Password Update in the OWL Protocol with DTLS Integration

The OWL protocol provides a secure and efficient mechanism for updating user passwords while preserving the integrity of the authentication process. When integrated with DTLS in CoAP-based systems, the password update process ensures that sensitive information remains encrypted and protected throughout the update, adding an additional layer of security.

6.3.1. Password Update Process

User Operations:

The user selects a new password

. Using cryptographic hash functions, the user computes:

where

H is a secure hash function and

U is the user’s identifier.

enhancing protection against dictionary attacks.

The user computes the verification value:

which will be used for future authentication attempts.

The user securely transmits and to the server over a DTLS-encrypted channel.

Server Preparation: The server decrypts and verifies the received

and

using DTLS to ensure integrity and authenticity. The server then replaces the existing values

and

T with

and

, securely storing the updated credentials for future authentication. See

Figure 3.

6.3.2. Security Implications

The password update process, reinforced with DTLS, ensures that:

Sensitive information, such as the new password , is never transmitted or stored in plaintext.

All computations are performed using cryptographic hash functions, enhancing resistance to attacks such as eavesdropping or replay attacks.

The updated values and are seamlessly integrated into the existing authentication framework, maintaining compatibility with the security guarantees of the protocol.

DTLS encrypts the communication channel, ensuring confidentiality and integrity during the password update process.

This mechanism highlights the flexibility and robustness of the OWL protocol in adapting to dynamic credential updates, making it a secure solution for resource-constrained IoT devices in CoAP-based environments.

7. Experimental Design

To rigorously evaluate the performance of the **OWL-CoAP integration** proposed within IoT environments, a **comprehensive experimental design** was developed to compare it with **traditional security approaches**. The evaluation focused on four key performance metrics: **computational efficiency, communication overhead, authentication latency, and security robustness**. These metrics were analyzed at multiple levels to account for varying operational conditions and device capabilities.

To ensure **validity and reliability** of the results, several critical statistical considerations were incorporated into the experimental design, including **normality, randomization, and homoscedasticity** (homogeneity of variances). The assumption of normality was verified to confirm that the collected data followed a **Gaussian distribution**, ensuring the appropriateness of parametric statistical tests. Randomization was applied throughout the experiment to minimize bias and external influences, ensuring a fair comparison between **OWL-CoAP and conventional protocols**. Furthermore, homoscedasticity was assessed to confirm that variance levels remained consistent between different experimental groups, enhancing the **statistical significance** of the observed differences.

These methodological safeguards were implemented to provide a **robust assessment** of the performance differences between the evaluated protocols. **As detailed in

Table 5, the study examines the impact of key factors such as key size, encryption methods, protocol types, and attack resilience on the selected performance metrics. This structured approach enables a comprehensive comparison of OWL-CoAP with alternative security mechanisms, offering valuable insights into its effectiveness and adaptability for various IoT deployment scenarios**.

7.1. Experimental Setup

The experimental environment consists of the following elements:

Software Environment: The simulation is implemented in Python using the aiocoap library for CoAP communication.

Security Configuration: The server operates over **DTLS on port 5684**, supporting both **unidirectional and bidirectional DTLS authentication**.

Network Simulation: Network conditions, including **latency, bandwidth, and packet loss**, are emulated using Mininet and Linux Traffic Control (tc).

Evaluation Tools: Data collection and monitoring are performed using **Wireshark**, custom Python scripts, and statistical analysis in **Matplotlib and Pandas**.

ThingsBoard Integration: The simulated IoT devices securely communicate with a ThingsBoard server running a **CoAP DTLS endpoint**.

7.1.1. Security Configuration and Certificate Management

To enable secure CoAP communication with **DTLS**, the ThingsBoard instance is configured with **valid ECDSA certificates** stored in PEM format. The following configurations were applied:

export COAP_DTLS_ENABLED=true

export COAP_DTLS_CREDENTIALS_TYPE=PEM

export COAP_DTLS_PEM_CERT=server.pem

export COAP_DTLS_PEM_KEY=server_key.pem

export COAP_DTLS_PEM_KEY_PASSWORD=secret

export COAP_DTLS_BIND_PORT=5684

For testing purposes, self-signed ECDSA certificates were generated using the following commands:

openssl ecparam -out server_key.pem -name secp256r1 -genkey

openssl req -new -key server_key.pem -x509 -nodes -days 365 -out server.pem -subj "/CN=localhost"

Note: While self-signed certificates are useful for testing, it is recommended to use a ** certificate from a trusted Certificate Authority (CA) for production deployments**.

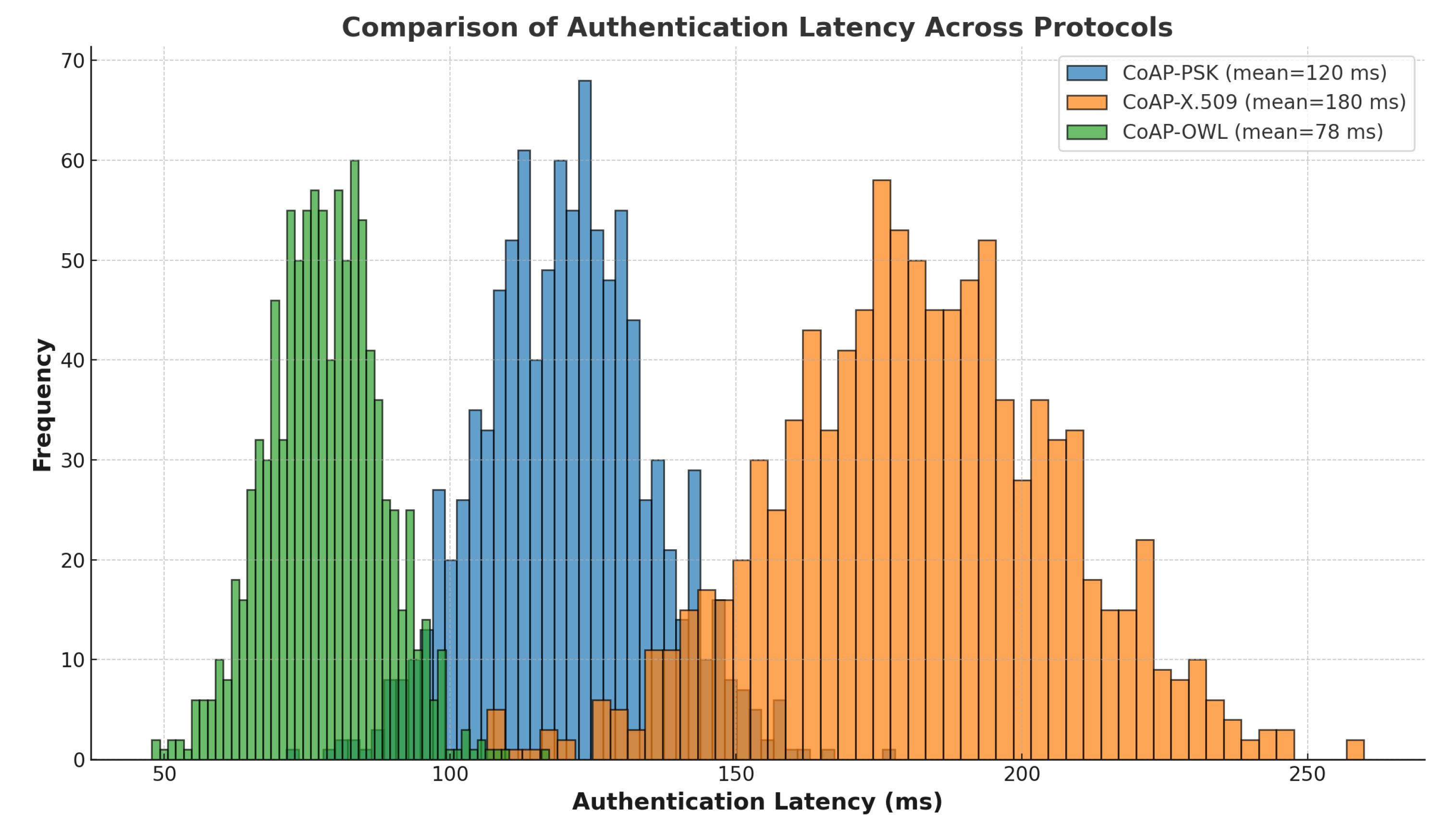

7.2. Authentication Latency

Authentication latency is a critical factor in IoT security. In this study, a comparative analysis was performed on the authentication latency of the **CoAP-PSK, CoAP-X.509, and CoAP-OWL** protocols. The latency data were generated through simulations using a **normal distribution** with predefined mean and standard deviation values for each protocol.

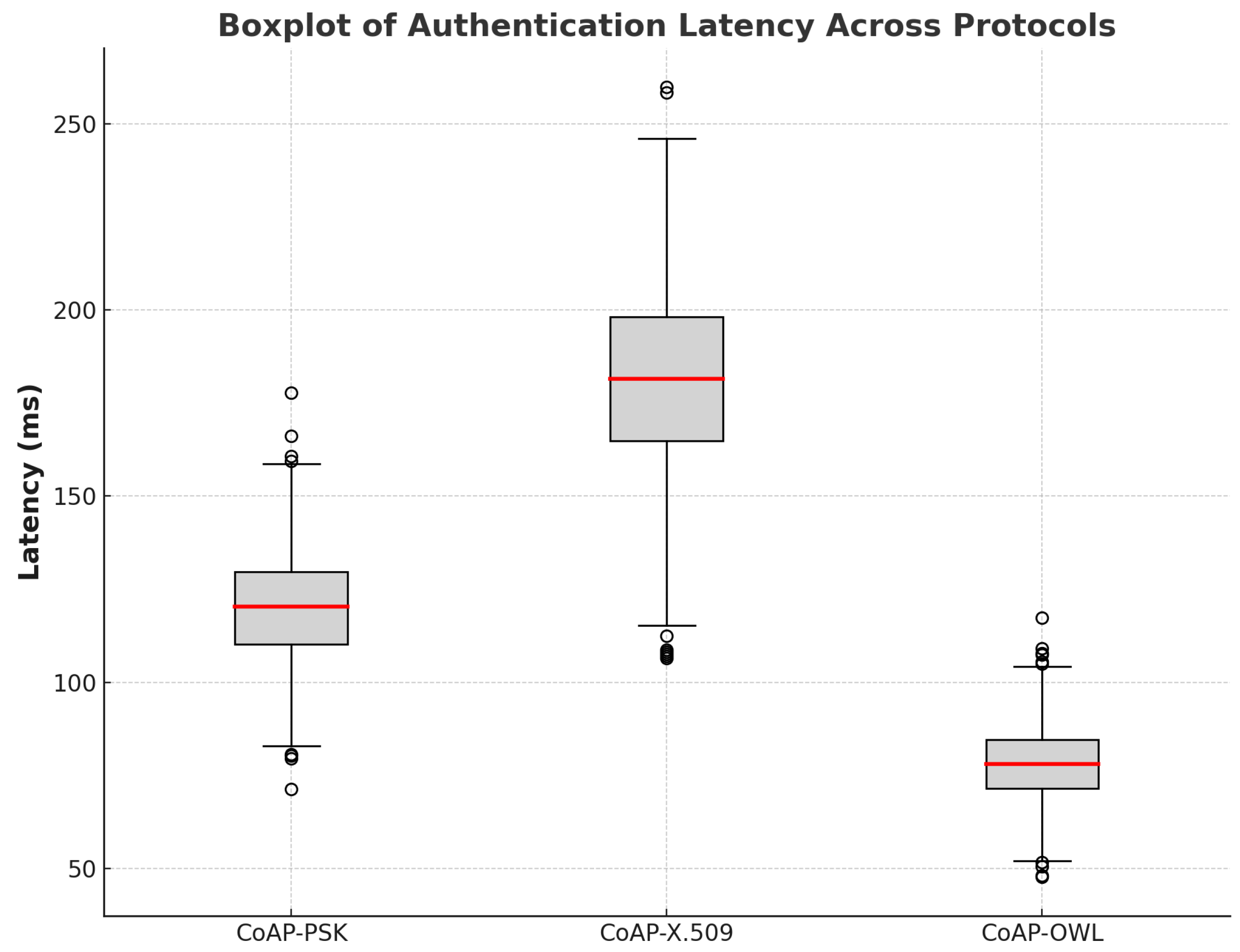

Figure 4 presents the histogram of authentication latency, highlighting significant differences in performance between the evaluated protocols. **CoAP-OWL demonstrates the lowest average latency**, making it the most efficient solution for **IoT environments that require rapid authentication**. In contrast, **CoAP-X.509 exhibits the highest latency**, reflecting the additional processing time associated with **certificate-based authentication**. **CoAP-PSK falls between the two**, offering a **moderate trade-off between speed and security**.

Figure 5 provides a box plot visualization of latency dispersion between protocols. CoAP-OWL shows minimal variation, indicating consistent authentication times, while CoAP-X.509 reveals significant variability, attributed to complex cryptographic operations. CoAP-PSK exhibits moderate dispersion, suggesting stable but slightly variable authentication times compared to CoAP-OWL.

Table 6 summarizes the statistical results, including the mean latency and standard deviation for each protocol. CoAP-OWL achieves the best performance, with an average latency of 78.06 ms and the lowest standard deviation, reinforcing its suitability for time-sensitive IoT applications. CoAP-PSK, with a mean latency of 120.29 ms, provides a reasonable balance, whereas CoAP-X.509 incurs a significant overhead with an average latency of 181.77 ms.

The results highlight that CoAP-OWL not only offers lower latency but also provides a more predictable and reliable authentication process. Its lightweight design and efficient cryptographic approach make it an optimal choice for IoT deployments where responsiveness and resource efficiency are paramount. The CoAP-PSK protocol presents a viable alternative for scenarios where moderate security and authentication speed are required. In contrast, CoAP-X.509, while offering robust security, may not be suitable for applications with stringent latency requirements due to its computational complexity.

These findings underscore the importance of selecting an appropriate authentication mechanism based on the specific needs of the IoT application. The CoAP-OWL protocol stands out as the most effective solution to achieve secure and efficient communication in constrained environments, contributing to the overall resilience and performance of IoT ecosystems.

8. Computational Overhead

To evaluate the computational overhead of the OWL-DTLS and DTLS-X.509 protocols, we performed a simulation that focused on three critical metrics: computational complexity, energy consumption, and network overhead. The results provide insights into the suitability of these protocols for resource-constrained IoT environments by analyzing their performance across different key sizes, ranging from 1 to 500 bits, with 1000 iterations per key size to ensure statistical significance. The complexity models were derived considering key factors such as computational efficiency, security mechanisms, and protocol design.

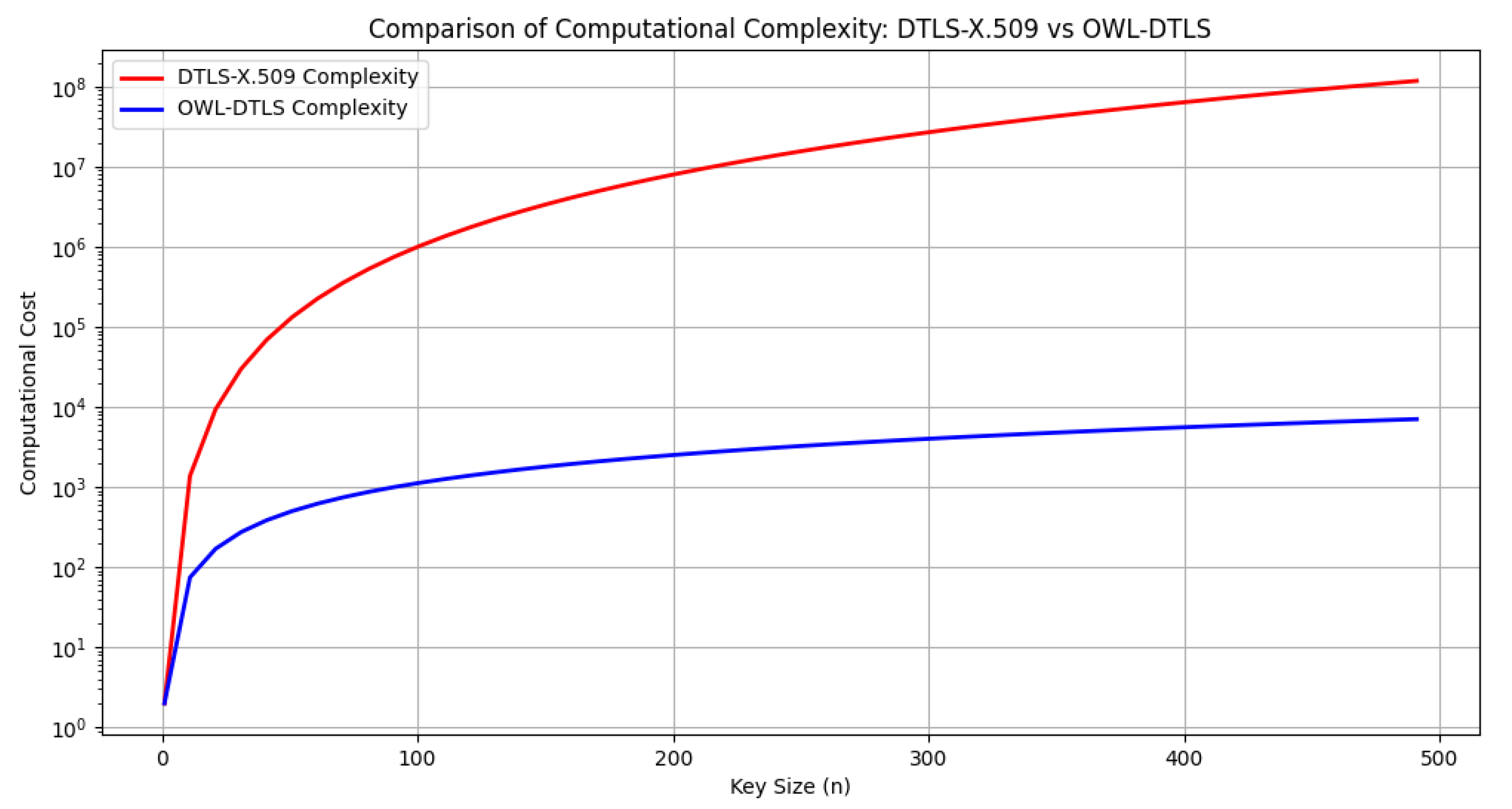

The following is a comparison of the computational complexity between the DTLS-X.509 and OWL-DTLS protocols, highlighting the advantages that OWL-DTLS offers in terms of performance and security. Although DTLS-X.509 relies on asymmetric cryptography with high computational cost, OWL-DTLS adopts more efficient techniques, such as password-authenticated key exchange (PAKE), which optimizes authentication and session establishment.

Table 7 presents a detailed comparison of both protocols, illustrating key differences in terms of key generation, verification, handshake complexity, encryption overhead, and attack resilience.

In general, OWL-DTLS offers a significant reduction in computational complexity, resulting in lower resource consumption and shorter processing times. Optimization of verification and handshake operations contributes to faster and more efficient authentication, while its design, based on robust passwords, provides better resilience against attacks, overcoming the limitations of DTLS-X.509 in environments with high security and efficiency requirements. The simulation results for computational cost, illustrated in

Figure 6, demonstrate that OWL-DTLS consistently outperforms DTLS-X.509 by reducing complexity, making it more suitable for low-resource devices. As summarized in

Table 7, OWL-DTLS achieves this efficiency by reducing the complexity of key generation, minimizing handshake overhead, and eliminating the need for certificate validation, making it a more practical solution for constrained IoT environments.

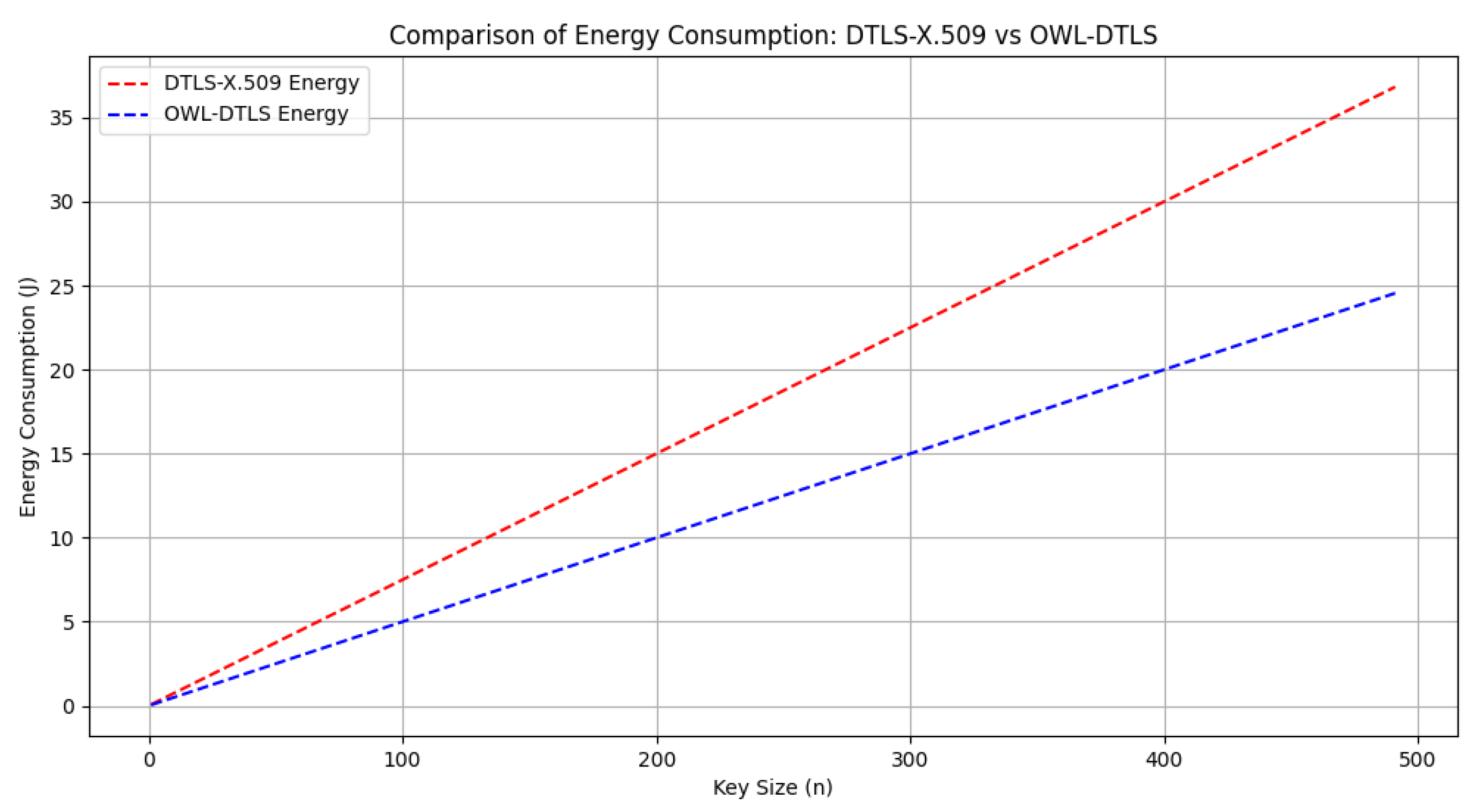

In terms of energy consumption,

Figure 7 indicates that OWL-DTLS consumes

20% less energy compared to DTLS-X.509 across all key sizes, mainly due to the simplified cryptographic operations and reduced handshake complexity. The base energy consumption for OWL-DTLS is calculated at

Joules, whereas DTLS-X.509 incurs additional penalties due to the certificate verification process.

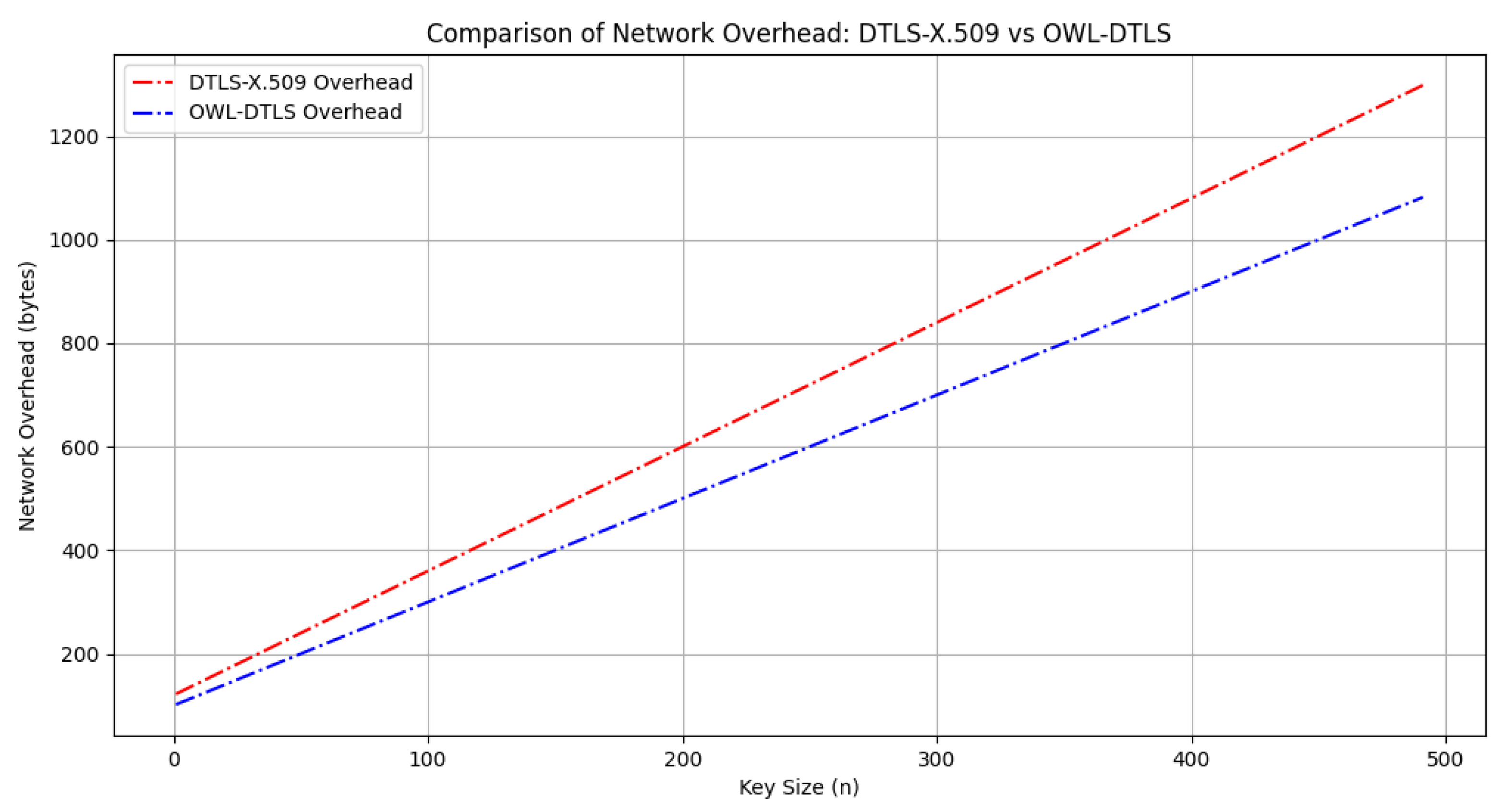

Regarding network overhead, the analysis presented in

Figure 8 demonstrates that OWL-DTLS introduces significantly lower overhead, with an average reduction of

18% compared to DTLS-X.509. The improved efficiency of OWL-DTLS allows for reduced message sizes and fewer data exchanges, which is crucial in IoT scenarios where bandwidth is a limiting factor.

Table 8 summarizes a sample of the simulation results for both protocols:

The findings confirm that OWL-DTLS is a more efficient alternative for IoT applications due to its lower computational complexity, reduced energy consumption, and minimal network overhead. This makes OWL-DTLS an attractive solution for enhancing the security of constrained IoT environments while ensuring optimal performance.

9. Discussion

The experimental results provide a detailed perspective on the computational efficiency and communication performance of OWL-DTLS compared to DTLS-X.509. The data collected from the simulations demonstrate a clear reduction in computational overhead, energy consumption, and network resource usage, which are critical factors for IoT deployments in constrained environments.

The computational complexity analysis, shown in

Figure 6, indicates that OWL-DTLS requires significantly fewer processing resources compared to DTLS-X.509. The simplified cryptographic operations and the use of PAKE-based authentication mechanisms contribute to reducing the overall processing burden. These reductions are particularly evident as key sizes increase, demonstrating the ability of OWL-DTLS to scale efficiently without introducing excessive computational demands.

Energy consumption is another critical aspect addressed in the experimental evaluation. As illustrated in

Figure 7, OWL-DTLS consistently consumes less power compared to DTLS-X.509. This efficiency is attributed to the streamlined key exchange and authentication processes, which reduce the need for repetitive cryptographic operations. Lower energy requirements make OWL-DTLS a viable solution for battery-powered IoT devices operating in remote or resource-constrained environments.

The evaluation of network overhead, depicted in

Figure 8, highlights the efficiency of OWL-DTLS in minimizing data transmission overhead. The results indicate an approximate 18% reduction in communication overhead compared to DTLS-X.509. This improvement stems from OWL-DTLS’s ability to optimize message exchanges and reduce redundant data transmissions, which is particularly beneficial in low-bandwidth IoT networks.

Despite these positive observations, several challenges persist. One of the primary concerns is the scalability of OWL-DTLS in large-scale IoT networks. As the number of connected devices increases, the management of authentication sessions and key distribution becomes increasingly complex. Efficient handling of these elements is crucial to maintaining performance and avoiding potential bottlenecks in high-density deployments.

Another area of interest is the adaptability of OWL-DTLS to different IoT communication protocols and network architectures. Given the diversity of IoT ecosystems, interoperability with existing protocols such as MQTT, CoAP, and LoRaWAN remains an ongoing area of exploration. Ensuring seamless integration without compromising security or performance is a key consideration for practical implementation.

Furthermore, while OWL-DTLS exhibits lower processing and energy costs, the trade-offs between security and performance need to be continuously assessed. Ensuring that reduced complexity does not compromise the robustness of the authentication process is essential to maintain the integrity of IoT communications, particularly in applications with stringent security requirements.

In general, the analysis of the experimental data underscores the potential advantages and areas for further optimization in the deployment of OWL-DTLS for IoT environments. Future evaluations should focus on dynamic testing scenarios, varying network loads, and real-world deployments to further validate the performance metrics observed in controlled simulations.

10. Conclusions

The integration of the OWL password-authenticated key exchange protocol with the Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP) and the Datagram Transport Layer Security (DTLS) offers a compelling solution to the evolving security challenges in IoT ecosystems. The experimental results highlight the superior performance of OWL in terms of computational efficiency, energy consumption, and network overhead compared to traditional DTLS-X.509 implementations. The lightweight design of OWL, which leverages password-based authentication and zero-knowledge proofs, makes it particularly well suited for resource-constrained IoT devices, reducing processing overhead while maintaining robust security guarantees.

The comparative analysis underscores the ability of OWL to achieve a significant reduction in computational complexity, as evidenced by lower energy consumption and communication overhead. These improvements directly translate into extended device lifespan, reduced latency, and improved scalability for large-scale IoT deployments. In particular, OWL’s streamlined cryptographic operations, such as efficient key derivation and verification, contribute to its reduced energy footprint, making it a viable alternative for battery-powered and energy-sensitive environments.

Despite these advantages, the integration of OWL with CoAP and DTLS presents critical challenges that require further attention. The scalability of the protocol in dense IoT networks, where thousands of devices need to authenticate and communicate securely, remains an open area of research. Effective session management, key distribution strategies, and protocol optimization are necessary to ensure that performance scales without deterioration in security. Furthermore, interoperability remains a crucial concern, as IoT ecosystems consist of heterogeneous devices employing various communication protocols. Ensuring seamless integration with existing IoT standards such as MQTT, Zigbee, and LoRa while maintaining security consistency across platforms is imperative for widespread adoption.

Another notable challenge lies in balancing security with performance. Although OWL excels in reducing computational costs and energy consumption, its implementation must carefully consider potential trade-offs in security strength, particularly in high-risk environments requiring stronger cryptographic assurances. The exploration of hybrid approaches that combine OWL efficiency with complementary security measures such as post-quantum cryptographic primitives may provide a promising path forward.

Future efforts should focus on refining OWL deployment strategies in real-world IoT environments, optimizing its implementation for diverse use cases such as industrial automation, healthcare monitoring, and smart city infrastructure. Further testing under varying network conditions and load scenarios will be critical in validating the robustness and resilience of the OWL-CoAP-DTLS integration. In addition, improvements in the provisioning process, including dynamic key updates and automated certificate management, will play a pivotal role in streamlining the onboarding and lifecycle management of secure devices.

The integration of the OWL protocol with CoAP and DTLS marks a significant step forward in IoT security, offering an optimal balance between robust authentication, computational efficiency, and resource conservation. By addressing the remaining challenges through continued research and technological advancements, OWL has the potential to redefine secure communication frameworks for IoT, driving enhanced resilience, scalability, and operational efficiency across a wide range of applications.

References

- Rivera-Julio, Y. Design of a telemedicine ubiquitous architecture based on the smart device mhealth Arduino 4G; Vol. 657, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Julio, Y.E.R. Design ubiquitous architecture for telemedicine based on mhealth Arduino 4G LTE. 2016 IEEE 18th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services, Healthcom 2016. [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Bag, S.; Chen, L.; Van Oorschot, P.C. Owl: An Augmented Password-Authenticated Key Exchange Scheme. Technical report.

- Laaroussi, Z.; Novo, O. A performance analysis of the security communication in CoAP and MQTT. 2021 IEEE 18th Annual Consumer Communications and Networking Conference, CCNC 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bhawiyuga, A.; Wardhana, A.; Amron, K.; Kirana, A.P. Platform for integrating internet of things based smart healthcare system and blockchain network. Proceedings - 2019 6th NAFOSTED Conference on Information and Computer Science, NICS 2019, 2019; 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, N.; Ramli, K.; Suryanegara, M.; Suryanto, Y. Potential Development of AES 128-bit Key Generation for LoRaWAN Security. 2019 2nd International Conference on Communication Engineering and Technology, ICCET 2019, 2019; 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davani, Z.A.; Manaf, A.A. Enhancing key management of ZigBee network by steganography method. 2013 2nd International Conference on Informatics and Applications, ICIA 2013, 2013; 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.; Miranda, R.N.; Cruz, P.M.; Mendonca, H.S. Multi-Protocol LoRaWAN/Wi-Fi Sensor Node Performance Assessment for Industry 4.0 Energy Monitoring. Proceedings of the 2019 9th IEEE-APS Topical Conference on Antennas and Propagation in Wireless Communications, APWC 2019, 2019; 403, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, I.R.; Vukobratović, D. Five Years of 3GPP NB-IoT Technology: What Are the Main Use Cases? 2024 23rd International Symposium INFOTEH-JAHORINA (INFOTEH), 2024; 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardašević, G.; Katzis, K.; Bajić, D.; Berbakov, L. Emerging Wireless Sensor Networks and Internet of Things Technologies—Foundations of Smart Healthcare. Sensors 2020, Vol. 20, Page 3619 2020, 20, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Gong, G.; He, J.; Nguyen, K.; Wang, H. PAKEs: New Framework, New Techniques and More Efficient Lattice-Based Constructions in the Standard Model. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2020; 12110 LNCS, 396–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Hu, W. Provably Secure Asymmetric PAKE Protocol for Protecting IoT Access. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 7071–7078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, N.; Muraoka, K.; Okuyama, T.; Suyama, S.; Okumura, Y.; Asai, T.; Matsumura, Y. 28 GHz-Band Experimental Trial at 283 km/h Using the Shinkansen for 5G Evolution. 2020 IEEE 91st Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Spring), 2020, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Kitao, K.; Benjebbour, A.; Imai, T.; Kishiyama, Y.; Inomata, M.; Okumura, Y. 5G System Evaluation Tool. 2018 IEEE International Workshop on Electromagnetics:Applications and Student Innovation Competition (iWEM), 2018, pp. 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Aluigi, L.; Orecchini, G.; Larcher, L. A 28 GHz Scalable Beamforming System for 5G Automotive Connectivity: an Integrated Patch Antenna and Power Amplifier Solution. 2018 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Workshop Series on 5G Hardware and System Technologies (IMWS-5G), 2018, pp. 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Shinjo, S.; Nakatani, K.; Kamioka, J.; Komaru, R.; Noto, H.; Nakamizo, H.; Yamaguchi, S.; Uchida, S.; Okazaki, A.; Yamanaka, K. A 28GHz-band highly integrated GaAs RF frontend Module for Massive MIMO in 5G. 2018 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Workshop Series on 5G Hardware and System Technologies (IMWS-5G), 2018, pp. 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Jayaprasanna, M.C.; Soundharya, V.A.; Suhana, M.; Sujatha, S. A block chain based management system for detecting counterfeit product in supply chain. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Communication Technologies and Virtual Mobile Networks, ICICV 2021, 2021; 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, A.G. -binomial coefficients. 2006; 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Eppen, G.; Gould, F.; Schmidt, C.; Moore, J.H.; Weatherford, L.R. "Optimización no lineal" 2000. pp. 358– 359.

- Qdo, R.; Ri, V.L.V.; Ojrulwkpv, R.; Edfk, O.H.R.; Ulw, P.; Eudqnr, H.G.X.; Furdwld, P.; Hgx, U.L.W.; Djdu, P.; Ulw, F.; Wkh, J.; Ri, S.; Surfhvvhv, I.; Ghfhswlyh, R.U. &rpsdudwlyh $qdo\vlv ri %orfnfkdlq &rqvhqvxv $ojrulwkpv / 0 . 2018, 1545–1550. [Google Scholar]

- Otoo, E.J.; Wang, H.; Nimako, G. 2016 IEEE 18th International Conference on High Performance Computing and Communications ; IEEE 14th International Conference on Smart City ; IEEE 2nd International Conference on Data Science and Systems Multidimensional Sparse Array Storage for Data Anal. 2016, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.h.; Yi, H.; Mak, P.i.; Yin, J.; Martins, R.P. 24.4 A 0.18V 382μW Bluetooth Low-Energy (BLE) Receiver with 1.33nW Sleep Power for Energy-Harvesting Applications in 28nm CMOS 2017. 1, 414–416.

- Board, I. 41. LE910 Interface.

- Libelium Comunicaciones Distribuidas, S.L. 4G + GPS Shield for Arduino – LE910 - (4G / 3G / GPRS / GSM / GPS / LTE / WCDMA / HSPA+), 2016.

- Khan, A.H.; Qadeer, M.A.; Ansari, J.A.; Waheed, S. 4G as a Next Generation Wireless Network. 2009 International Conference on Future Computer and Communication 2009, pp. 334–338. [CrossRef]

- Dahlman, E.; Parkvall, S.; Sköld, J. 4G: LTE/LTE-Advanced for Mobile Broadband; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 103–119.

- Su, W.T.; Chen, W.C.; Chen, C.C. An extensible and transparent thing-to-thing security enhancement for MQTT protocol in IoT environment. Global IoT Summit, GIoTS 2019 - Proceedings 2019. [CrossRef]

- Suleymanov, E.; Kirdan, E.; Pahl, M.O. Securing CoAP with DTLS and OSCORE. 2022 6th Cyber Security in Networking Conference, CSNet 2022 2022. [CrossRef]

- Seller, O. LoRaWAN Security. Journal of ICT Standardization 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, J.; Zhang, B.; Kim, J.; Shin, Y. An Enhanced Trust Center Based Authentication in ZigBee Networks. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 2009, 5576 LNCS, 471–484. [CrossRef]

- Bhawiyuga, A.; Data, M.; Warda, A. Architectural design of token based authentication of MQTT protocol in constrained IoT device. Proceeding of 2017 11th International Conference on Telecommunication Systems Services and Applications, TSSA 2017 2017, 2018-January, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Unwala, I.; Taqvi, Z.; Lu, J. IoT security: ZWave and thread. IEEE Green Technologies Conference 2018, 2018-April, 176–182. [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Lai, M. Research on NB-IOT Device Access Security Solutions. 2023 3rd International Conference on Electronic Information Engineering and Computer, EIECT 2023 2023, pp. 419–424. [CrossRef]

- Grané, M.; Martínez, J.D.; Arnaud, A.; Puyol, R.; Miguez, M. A Sensor Network Using SigFox for Temperature and Humidity Monitoring in the Livestock Industry. 2024 IEEE 15th Latin America Symposium on Circuits and Systems (LASCAS). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).