1. Introduction

Modern energy systems are undergoing rapid digital transformation through IoT and smart monitoring technologies [

1]. While enabling operational optimization, this transformation exposes critical infrastructure to new security threats, including data breaches that can compromise entire energy networks [

2]. In industrial energy environments, sensitive data such as grid performance metrics and equipment status require robust protection against both external attacks and insider threats [

3]. The challenge is particularly acute in distributed energy resources (DERs) and smart grids, where cross-domain data flows create complex attack surfaces [

4].

Anonymous access control has emerged as a crucial mechanism for protecting energy system communications while maintaining operational transparency [

5]. Current approaches fall into two categories: cryptographic methods using zero-knowledge proofs [

9] and proxy-based solutions [

10]. However, these methods face significant limitations when applied to energy systems - cryptographic techniques incur excessive computational overhead for resource-constrained field devices, while proxy solutions struggle with the real-time demands of energy management systems [

6].

Recent advancements in zero-trust architectures show promise for energy applications. The software-defined perimeter (SDP) framework [

14] and steganographic authentication [

12] have demonstrated potential for secure energy data exchange. However, these solutions often fail to address the unique latency and scalability requirements of industrial energy systems [

15]. Our work bridges this gap by introducing a dual-mode authentication mechanism that adapts to both high-reliability TCP and lightweight UDP environments common in energy IoT deployments.

In 2024, Shen Q. and Shen Y. proposed a zero-trust anonymous access scheme under the SDP architecture [

16], utilizing a three-party key agreement for single-packet authentication (SPA) key distribution [

17]. The scheme improves the system’s response speed through simplifying the key distribution process, but may face bottlenecks in terms of key management and distribution efficiency when dealing with large-scale concurrent access. These studies highlight the growing importance of efficient and secure anonymous access control mechanisms for use in modern network architectures [

32]. Although these studies have made some progress in the field of anonymous access control, they still face several challenges that need to be addressed.

Overall, the above approaches face the following two challenges:

1. High performance overhead: Anonymous access through encryption requires complex encryption and decryption operations which require a large number of computing resources, resulting in increased access latency and reduced system efficiency. The forwarding of requests through a proxy server increases network latency and bandwidth consumption, especially in the case of a large number of users or high network traffic, where the performance overhead can become significant.

2.

Vulnerability to cyberattacks: Existing anonymous access control methods make it difficult to identify and block unauthorized access, and attackers can take advantage of the inadequacies of these control mechanisms to access the system disguised as a legitimate user [

18], thus stealing data or carrying out other malicious operations [

19].

This study proposes a dynamic anonymous access control method based on dual-mode single-packet authentication to address the above challenges. The method utilizes dual-mode single-packet authentication technology to complete user authentication in the anonymous access phase, dynamically assesses the user’s trust level through a trust assessment module, and ultimately decides whether to allow the user to access network resources. In particular, single-packet authentication is a network authentication technology used to complete the initialization of authentication and encrypted communication between the client and the server through a single data packet, while dual-mode single-packet authentication is an emerging network authentication technique that combines the user datagram protocol (UDP) and the TCP to complete the initialization of user authentication and the preparation for encrypted communication through a single packet.

The primary contributions of this study are as follows:

A dual-mode single-packet authentication method that reduces communication and computational overhead by 37% and 41%, respectively, is proposed.

The proposed method resists network attacks (e.g., SPA key theft, knock amplification) while ensuring user privacy and anomaly detection.

A simulation environment is built using Network Simulator 3 to evaluate the method’s performance, demonstrating its improved communication and computational efficiency.

The organization of the chapters in this paper is as follows: The first section provides an introduction. The second section describes the overall architecture of the dynamic anonymous access control method based on dual-mode single-packet authentication, as well as the anonymous access process and the trust evaluation module. The third section explains the experimental environment, the evaluation metrics, and the experimental results, as well as analyzing the communication and time overheads. The fourth section presents the conclusion.

2. Methodology

2.1. Overall Architecture

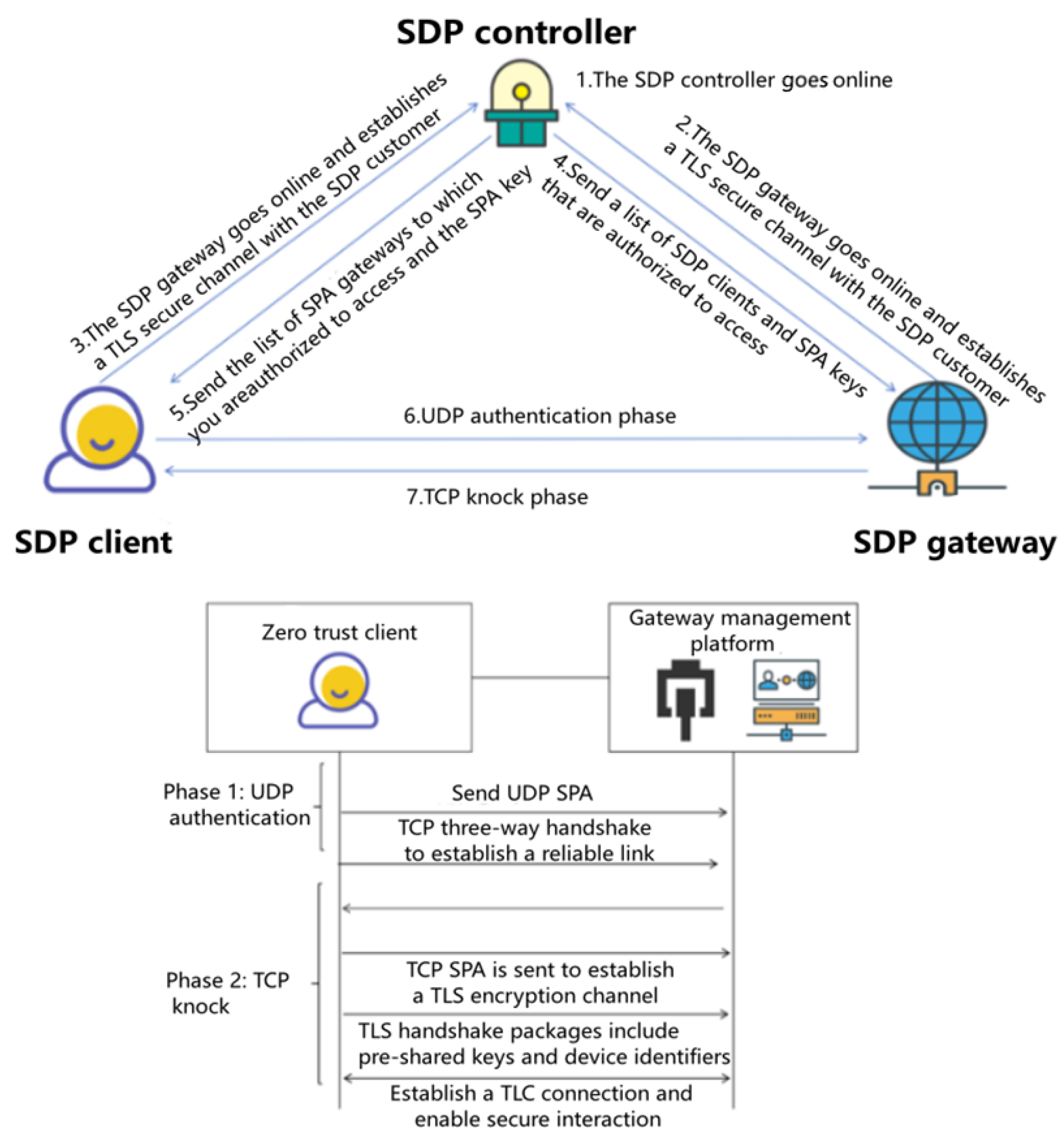

The dynamic anonymous access control method based on dual-mode single-packet authentication is composed of a two-way anonymous access module, a dual-mode single-packet authentication module, and a trust evaluation module. The dual-mode single-packet authentication module is deployed in the anonymous access step to resolve external attacks and protect the privacy of visitors [

20], while the trust evaluation module is deployed for access control. The trust evaluation module is deployed in the anonymous access step, which mainly addresses the problem regarding whether to grant a subject access to the object [

21], and includes four main steps: System establishment, system registration, anonymous access, and trust evaluation. The SDP architecture diagram is shown [

22] in

Figure 1.

First, during system establishment, both the SDP controller and the gateway are brought online. The controller is responsible for generating and sharing key negotiation parameters, while the gateway pre-calculates keys and sets up an index table for authorized clients. Following that, in the system registration phase, the SDP client initiates contact with the controller by sending its key negotiation parameters. In response, the controller creates an access list and issues certificates. Meanwhile, the client must verify the authenticity of these credentials to ensure secure communications. Moving on to anonymous access, in this stage, the gateway becomes ready to accept connections from clients who wish to remain unidentified. These clients go through a registration process and obtain the necessary credentials. Subsequently, they establish a secure channel using single-packet authentication, which includes UDP authentication and the TCP knocking phase, thus safeguarding the confidentiality of their interactions. Finally, in trust evaluation, various factors such as access success rates and user behaviors are taken into account, and direct trust values are calculated using fuzzy logic. Historical data are then combined with these values to derive a comprehensive trust score. This score is compared with a pre-defined threshold to determine whether or not to grant access rights, thus maintaining strict control over network security. In comparison to traditional two-packet methods, the single-packet approach offers several advantages: reduced attack surface, enhanced efficiency, and improved security. Specifically, through limiting the number of packets transmitted, attackers have fewer opportunities to intercept or manipulate data. In addition, combining processes into a single packet reduces latency and resource consumption, leading to faster and more efficient communication. Finally, the use of advanced cryptographic methods and dynamic trust evaluations makes it more difficult for attackers to compromise the authentication process.

2.2. Anonymous Access

The anonymous access phase mainly includes three steps: Launching the SDP gateway, SDP client online, and dual-mode single-packet authentication and access.

2.2.1. Launching the SDP Gateway

The SDP gateway performs the following four steps to interact with the SDP controller to go online: First, the private key is randomly selected and the SPA key agreement parameters are calculated. Second, the key agreement parameters are sent to the SDP controller, following which the SDP controller queries the list to generate a list of SPA key agreement parameters containing all SDP clients with access rights and sends it to the SDP gateway. Finally, the SPA key is pre-computed for all the parameters in the SPA key agreement parameter list, and the index table is established [

23].

2.2.2. Online SDP Client

The SDP client performs the following three steps to interact with the SDP controller: first, it randomly selects the private key, calculates the SPA key agreement parameters, and sends the SPA key agreement parameters to the SDP controller. Let

x denote the private key selected by the SPA client. The corresponding public key

X is computed as

where

g is a generator of the multiplicative group modulo

p, and

p is a large prime number. The SPA client then computes the SPA key agreement parameters, including

X and other necessary values, and sends them to the SDP controller. Secondly, the SDP controller generates the SDP gateway information accessible to the SDP client through the SPA key negotiation parameter list and access permission list of the SDP client, and generates the authorized access list. The SDP controller generates the linked certificate information and executes the signature algorithm to create the certificate. Finally, the SDP controller sends the link certificate information, the credentials, and the authorized access list to the SDP client, and the client executes the signing. To secure the SPA key index table, we employ advanced encryption algorithms to encrypt the table, ensuring that unauthorized access renders the data unreadable without the proper decryption keys. Additionally, we implement strict access controls to limit access and modifications to authorized personnel only. The specifics of the encryption process are not elaborated upon in this document.

The name validation algorithm verifies the validity of the credentials [

24].

2.2.3. Dual-Mode Single-Packet Authentication Access

Dual-mode single-packet authentication access mainly includes two phases: the UDP authentication phase and the TCP knocking phase.

The UDP authentication phase is mainly a secure communication process between the client and the SDP controller, which can be divided into four key steps: Sending the knock packet, encryption, verification, and the SDP gateway updating the firewall rules to allow legitimate access based on the verification results. First, the client sends the knock packet to the SDP controller, which contains the user security code, device identification, timestamp, random number, and host medium access control (MAC) value. To ascertain the integrity and confidentiality of data transmission, the user security code is encrypted using the SM3 hash algorithm, and the device identification is processed using the SM4 hash algorithm [

25]. Second, after receiving the SPA packet transmitted by the network card, the SDP gateway needs to undergo multiple verifications to verify the validity of its data. Finally, when the SPA package is verified, the SDP gateway updates the local firewall rules to open TCP port access rights for legitimate users and the device source IP, and sets a fixed time window. The purpose of setting this window is to prevent the port from being exposed to potential amplification attacks for a long time. From the perspective of user experience, the main factors to be considered when setting the time window are the network link delay and user authentication time, as the TCP knock packet may not be received if the window is too short, thus affecting the user experience [

26].

The TCP knocking phase can be divided into five key steps: TCP connection establishment, TLS handshake preparation, SPA token transfer, server-side SPA token authentication, and authentication result processing. First, the client and the SDP gateway establish a connection using the TCP three-way handshake procedure. Second, the client prepares the TLS handshake request and adds the SPA token in the TLS field, such that the data packet carries the dynamic token, and the TLS handshake packet may also contain information such as the user’s pre-shared key and the device identity. Then, the client sends the TLS handshake request containing the SPA token to the SDP gateway [

27]. Upon receiving the TLS handshake request, the SDP gateway extracts the SPA token from the extended field of the TLS handshake packet and verifies it, which typically includes verifying that the token is valid. Finally, for the authentication result, if the SPA token authentication is successful, the SDP gateway and the client complete the TLS handshake process and establish an encrypted communication channel. If the SPA token authentication fails, the SDP gateway disconnects the TCP connection with the client [

28].

During the UDP authentication phase, the client generates and sends a knock packet, which contains the user security code, device identifier, timestamp, random number, and host MAC value. The specific steps are as follows:

The client encrypts the user security code using the SM3 hash algorithm and processes the device identifier using the SM4 hash algorithm.

The client packages the encrypted user security code, processed device identifier, timestamp, random number, and host MAC value into a knock packet and sends it to the SDP gateway.

Upon receiving the knock packet, the SDP gateway performs multiple verifications, including checking the validity of the timestamp, the uniqueness of the random number, and the correctness of the device identifier.

If the knock packet passes verification, the SDP gateway updates the local firewall rules to open TCP port access and sets a fixed time window.

During the TCP knocking phase, the client establishes a TCP connection with the SDP gateway and performs a TLS handshake. The specific steps are as follows:

The client establishes a connection with the SDP gateway using the TCP three-way handshake procedure.

The client prepares the TLS handshake request and adds the SPA token in the TLS field. The TLS handshake packet also contains the user’s pre-shared key and device identity information.

The client sends the TLS handshake request containing the SPA token to the SDP gateway.

Upon receiving the TLS handshake request, the SDP gateway extracts the SPA token from the extended field of the TLS handshake packet and verifies its validity.

If the SPA token verification is successful, the SDP gateway completes the TLS handshake process with the client and establishes an encrypted communication channel. If the verification fails, the SDP gateway terminates the TCP connection with the client.

The entire process ensures that, before communication can be established from the client to the SDP gateway, the SPA token is first authenticated; therefore, the TLS handshake and data transfer are performed only after successful authentication, thus improving security in communications.

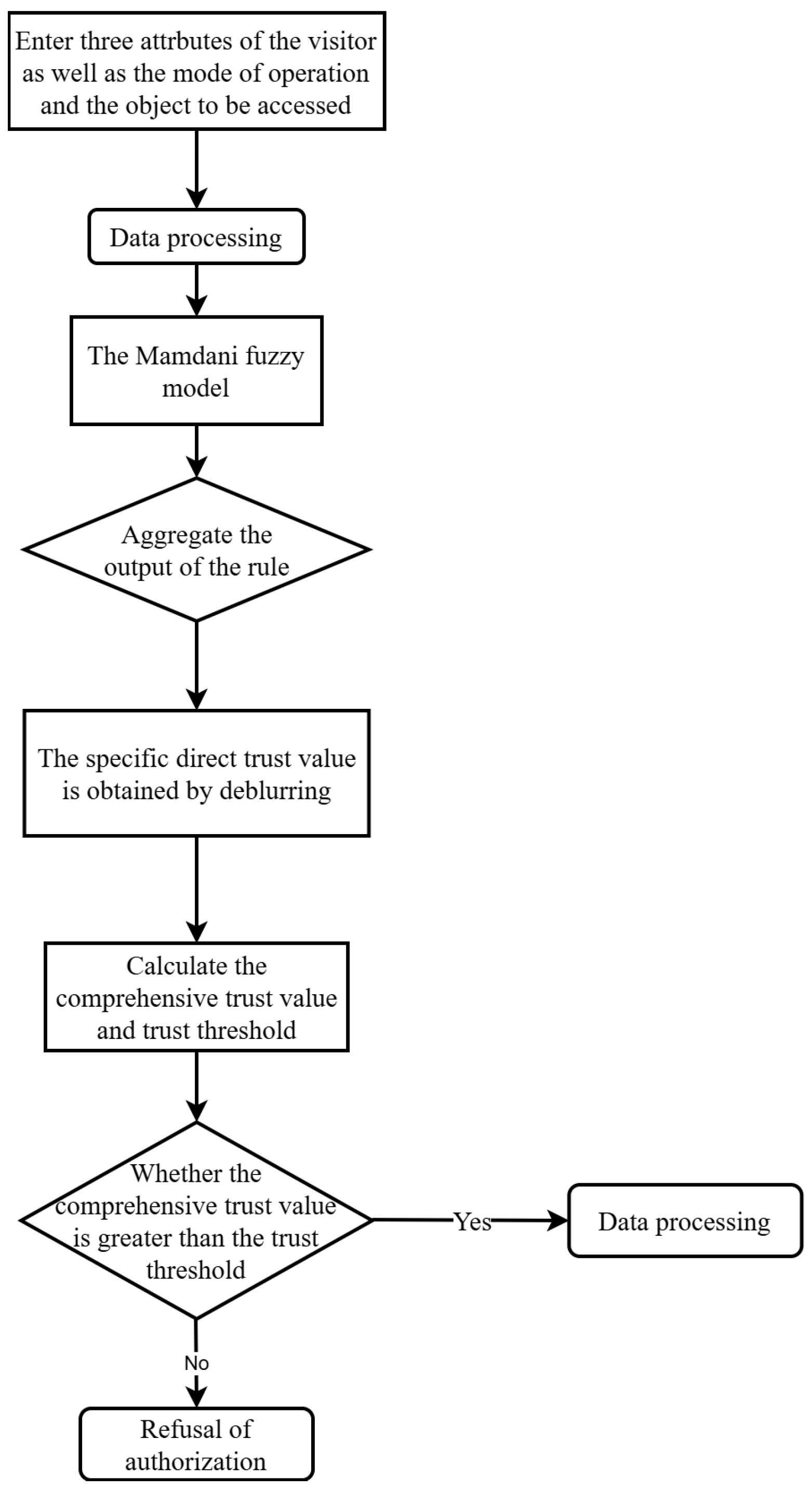

2.3. Trust Evaluation

Trust evaluation mainly includes five steps: Data processing, specifying fuzzy rules, fuzzy calculation, defuzzification, and calculating and comparing the comprehensive trust value and trust threshold. The flow chart is shown in

Figure 2 [

29].

During the data processing phase, the system calculates fuzzy sets based on the access success rate, the proportion of normal user behavior, and the proportion of trusted requests. The specific steps are as follows:

Calculate the access success rate A, the proportion of normal user behavior B, and the proportion of trusted requests C.

Input A, B, and C into the membership function (see below) to calculate the fuzzy set for each attribute.

During the fuzzy rule phase, the system performs inference based on a pre-defined fuzzy rule table. The specific steps are as follows:

Construct a fuzzy rule table with rules in the format “If A is high and B is medium, then the trust level is high.”

Based on the current attribute values, search for matching fuzzy rules and calculate the output for each rule.

During the fuzzy calculation phase, the system aggregates the matching fuzzy rules. The specific steps are as follows:

For each matching fuzzy rule, calculate its output fuzzy set.

Use the maximum method or weighted average method to aggregate all output fuzzy sets into a comprehensive fuzzy set.

During the defuzzification phase, the system calculates the comprehensive trust value. The specific steps are as follows:

Use the centroid method to calculate the centroid of the comprehensive fuzzy set, obtaining the direct trust value .

Based on historical trust values and the current trust value, calculate the comprehensive trust value .

2.3.1. Data Processing

According to the access success rate, the proportion of normal user behaviors, and the proportion of trusted requests, these three attribute values are brought into the membership function to calculate the fuzzy set of the three attributes. The membership function is defined as follows:

This equation defines a piecewise function f(x) that describes different behaviors across various intervals. Specifically, f(x) increases linearly from 0 to 1 as x moves from a to b, represented by the expression . Within the interval [b,c], the function remains constant at its maximum value of 1. As x transitions from c to d, the function decreases linearly back to 0, described by . Outside the range [a,d] (i.e., when x<a or x>d), the function value is zero. This function is typically used in fuzzy logic to model membership degrees, where it captures the gradual transition between different states, such as "low," "medium," and "high," and allows for a smooth representation of uncertainty or ambiguity in real-world data.

2.3.2. Specify Fuzzy Rules

Having identified the risk and its associated measures, the next logical step is to specify how the risk varies in response to various factors. To this end, a series of fuzzy rules are constructed to explain the relationships between indicators at different levels of risk. These fuzzy rules describe in detail how the access success rate, the proportion of abnormal user behaviors, the proportion of trusted requests, and the trust degree affect and determine each other [

30].

In this study, the Mamdani fuzzy model is adopted for fuzzy reasoning, which is an ideal choice for handling complex logical relationships due to its advantages in terms of intuitive rule expression, suitability for multi-factor reasoning, and the strong interpretability of its outputs. The rules of the Mamdani model are structured in an "If–Then" format, allowing the antecedents and consequents of fuzzy sets to intuitively express complex logical relationships, making it suitable for scenarios that require comprehensive decision making with multiple factors, such as trust assessment. Furthermore, the fuzzy set output by the model can be converted into specific numerical values through defuzzification methods (e.g., the centroid method), which facilitates subsequent decision making. Therefore, through utilizing the Mamdani model, it is possible to integrate multiple factors, dynamically assess user trust levels, and make reasonable authorization decisions based on the assessment outcomes.

2.3.3. Fuzzy Calculation

In the fuzzification process, each attribute is converted from a percentage to a membership degree of a fuzzy set according to the fuzzy set and membership function. Then, fuzzy operations can be carried out. After fuzzifying the input data, all the rules that meet the current condition are searched for in the previously constructed rule table. For each rule that meets the condition, we use fuzzy logic operators to calculate the membership degree of the confidence under that rule. After these calculations, a membership value representing the credibility is obtained as the output.

The aggregation of rule outputs is then performed, which is a process involving unifying the fuzzy sets generated by multiple rules into a single fuzzy set. The fuzzy sets derived from each rule (i.e., the membership functions) are aggregated to form a comprehensive fuzzy set. The input of the aggregation process is the membership function calculated by each rule, and the output is a comprehensive fuzzy set of the outcome variable (i.e., confidence degree).

2.3.4. Defuzzification

The final output is determined by calculating the center of gravity of the region bounded by the membership function curve and the abscissa. The combined fuzzy set is used as the input, followed by the computation of the centroid of the region bounded by the membership functions and the abscissa. The formula below describes how to calculate the direct trust value

, which is a single, continuous numerical value capable of being directly used in subsequent decisions or system responses.

where

v represents the variable and

u(v) denotes the membership function of

v. The integral range spans from 0 to 1, and the final result is multiplied by 100 to obtain a single continuous numerical value that can be directly used in subsequent decisions or system responses.

2.3.5. Calculate and Compare the Comprehensive Trust Value and Trust Threshold

The overall trustworthiness score is then determined. The comprehensive trust value is computed by integrating historical dimension data and assigning weights to the immediate trust assessment and that from the previous visit. The formula for calculating the comprehensive trust value

for request

i is as follows:

where

Ti is the time of this request,

Tj is the time of the last request,

DTi represents the direct trust level determined by the controller for this particular request,

CTj is the computed overall trust value at the last request

Tj,

is the Gaussian decay function, and the Gaussian time decay function is designed to measure the reference value

of the request.

Next, the trust threshold

Tth is calculated based on the confidentiality and integrity of the target resource and the request type of the visitor. This considers both the operation dimension and the object dimension, and the calculation formula is as follows:

where

Opcon refers to the confidentiality of the customer’s access to the target,

Obcon refers to the completeness of the customer’s access to the target, and Op represents the impact factor of different operations on resources. The impact factors for different operations are detailed in

Table 1.

Finally, if the calculated aggregated trust value exceeds the trust threshold, the gateway grants access permissions; otherwise, the authorization [

31] is denied.

2.4. Limitations and Constraints

In the proposed dynamic anonymous access control method, although it shows improvements in terms of communication and computational efficiency, it is important to clarify the assumptions on which the method is based, as well as its limitations: 1. The system assumes that the SDP gateway and SDP controller are always online and available for executing authentication tasks. If these critical components experience downtime or failures, the entire access control process may be affected or even interrupted. 2. The dual-mode single-packet authentication method we propose is suitable for network environments that support both UDP and TCP. If the network environment restricts either of these protocols, the method may require corresponding adjustments or modifications to be applicable. Despite these assumptions and limitations, the proposed method offers a robust and efficient solution in the field of dynamic anonymous access control, particularly for environments where user privacy and system security are of paramount importance.

3. Experiments and Results

3.1. Experimental Environment

To evaluate the practical effect of the proposed scheme, this research used the standard network communication protocol module built into the Network Simulator 3 platform to develop a simulation environment for interaction, simulating a terminal server running SPA, accessing gateway server, and a controller running SDP. The configuration of the specific experimental environment is detailed in

Table 2.

3.2. Experimental Evaluation Metrics

In order to evaluate the experimental results, this study assessed the communication and computation overheads.

The main communication overhead of the proposed scheme mainly comes from the software-defined perimeter controller distributing SPA key agreement parameters to the software-defined perimeter client and the software-defined perimeter gateway, and the software-defined perimeter client authenticating with the software-defined perimeter gateway using a single packet. The specific calculation formula is shown in Eq. (6):

where

represents the length of the SPA data packet,

represents the output length of the hash algorithm,

represents the length of the

TL digital certificate,

represents the length of the SPA key,

represents the length of the SPA key agreement parameters,

represents the length of the specified signature credential,

represents the number of additive group members, and

represents the length of the identity identification.

The computational overhead of the proposed scheme mainly derives from the calculation of the SPA key and the generation and verification of specified signature credentials. The calculation formulas are shown in Eqs. (7)–(9):

where

Tbp stands for bilinear mapping,

Tenc stands for the asymmetric encryption algorithm,

Tdec stands for the asymmetric decryption algorithm,

Ts stands for the signature algorithm,

Tv stands for the signature verification algorithm,

Ted stands for the symmetric encryption and decryption algorithm, and

Th stands for the hash algorithm. Eq. (7) denotes the additional computational cost necessary for SDP controller authentication, Eq. (8) denotes the additional computational cost necessary for SDP gateway authentication, and Eq. (9) represents the computational overhead required for SDP client authentication.

3.3. Experimental Results

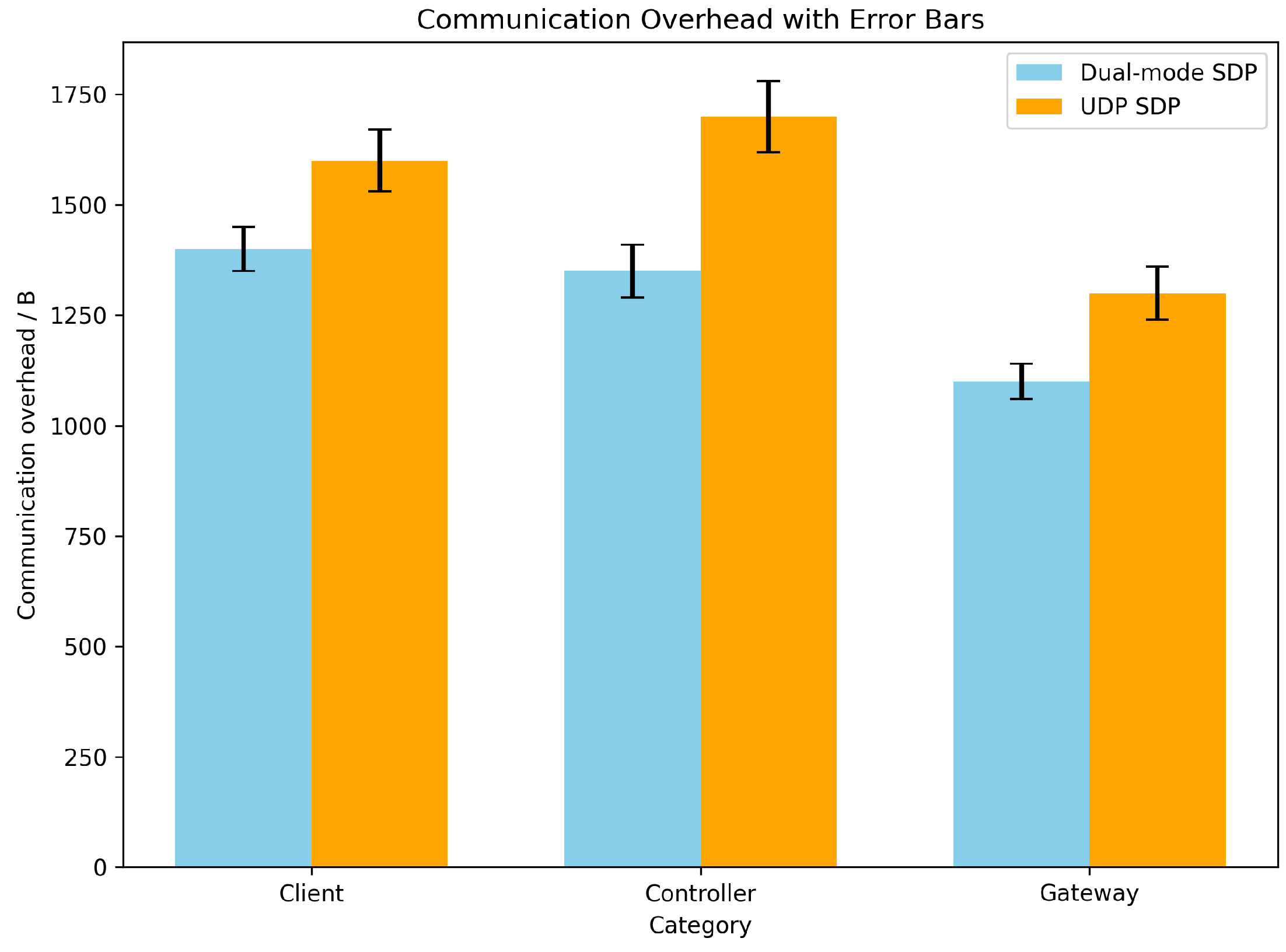

3.3.1. Analysis of Communication Overhead Results

First, Network Simulator 3 was used to evaluate the communication overheads associated with SDP client, SDP controller, and SDP gateway authentication after a complete authentication process. Under the same experimental conditions, the proposed scheme was compared with the UDP-based SDP scheme, and the experimental results are presented in the following figure.

Figure 3.

Communication overhead results.

Figure 3.

Communication overhead results.

The traditional UDP SDP scheme requires one-to-one correspondence between the authentication information and knock information during authentication. If the IP address in the SPA knock packet is in the SNAT environment, the returned information cannot be associated with the real access terminal, which will generate additional communication overhead. In the proposed scheme, UDP and TCP are combined, and the SPA knock packet sent contains more abundant information, allowing a connection for each TCP to be accurately established and the knock action to be completed, thus improving the accuracy of access authentication. The outcomes of the experiments indicate that the communication overhead of the proposed scheme to perform a complete dual-mode single-packet access authentication is 2764B, while the communication overhead of the UDP-based SDP scheme to perform a complete single-mode single-packet access authentication is 4362B. Compared with the UDP-based SDP scheme, the communication overhead required by the proposed scheme is reduced by 37%.

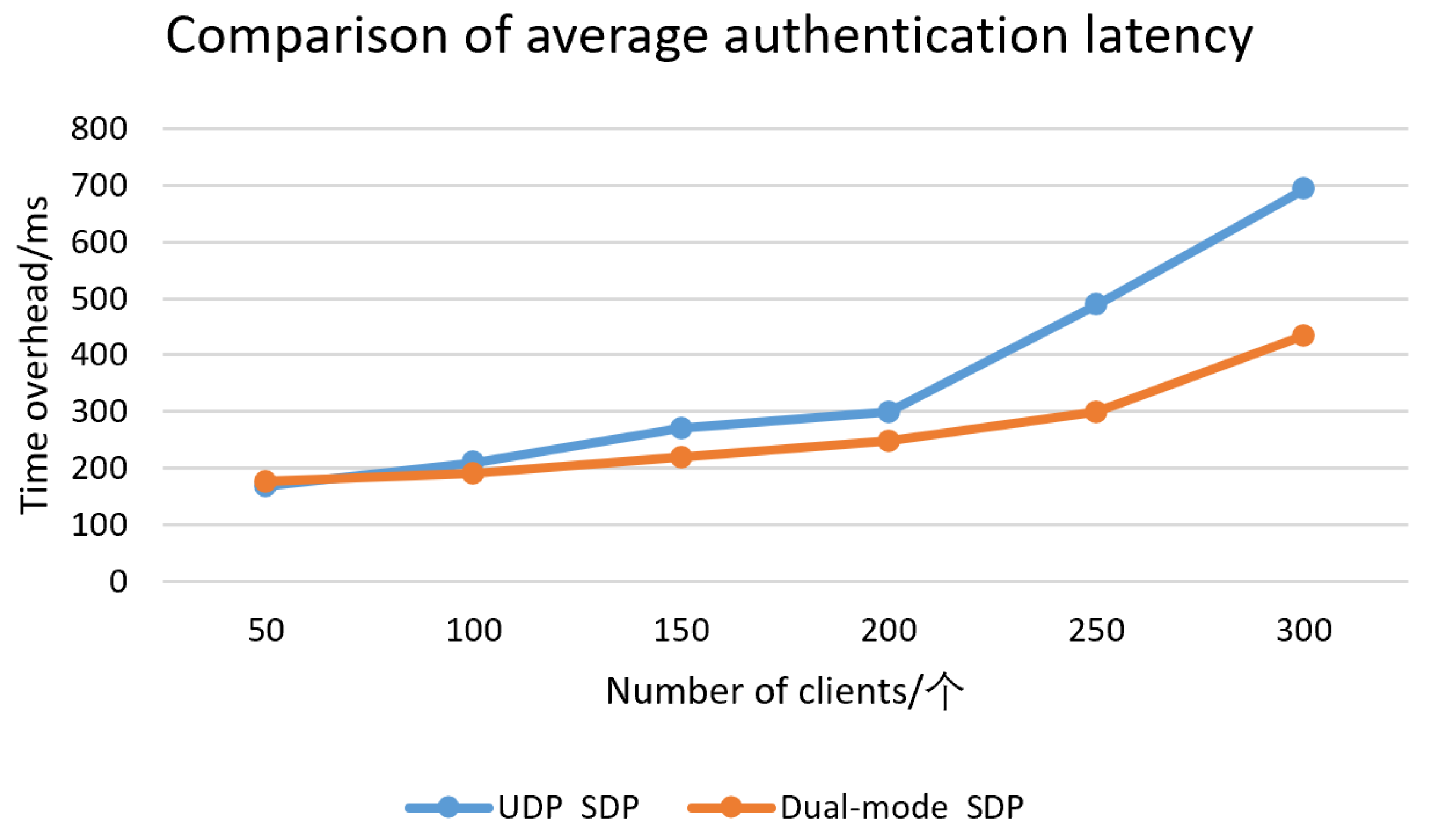

3.3.2. Analysis of Time Cost Results

To assess the effectiveness of our approach, we used the average authentication delay from the initiation of authentication request to the completion of anonymous authentication as a performance index, and developed a simulation environment based on Network Simulator 3. The environment was initialized with different numbers of clients and gateways, and the fundamental settings for the experimental parameters are presented in

Table 3.

The number of SDP clients and gateways in the experiment was set to simulate different network scales. The number of clients ranged from 50 to 500, representing small- to medium-sized enterprise networks, while the number of gateways ranged from 5 to 50, reflecting the typical ratio of clients to gateways in such environments.

This experiment assumed that the SDP gateway and SDP client were online, and simulated the behavior of dual-mode single-packet access authentication. The number of SDP clients was set to 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 500, and the corresponding number of SDP gateways was 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 50, respectively. In order to make the experiment closer to the real environment, the access frequency was randomly accessed according to the preset number. The network data transmission rate was set to 4 Mbps. The average authentication latency comparison is shown in

Figure 4.

The dual-mode SPA initially involves both UDP and TCP phases, which adds extra processing steps and potential delays when compared to the simpler UDP-based SPA. This added complexity can result in higher latency and reduced throughput, especially when there are fewer clients. In such cases, the system may not fully leverage the advantages of the dual-mode approach. However, the benefits of dual-mode SPA—such as improved security and efficiency—become evident under higher client loads, where the system can better manage and distribute resources.

The figure shows that, as the number of SDP clients increases, the access frequency also rises, leading to more frequent requests from the SDP gateway to the controller. The scheme adopted by the SDP gateway in this method has enhanced pre-computation capabilities, thus reducing the time overhead. The experimental results revealed a 37% reduction in communication overhead and a 41% reduction in time overhead, when compared to the UDP-based SDP scheme. In particular, with 500 SDP clients and 50 SDP gateways, the time overhead of the proposed scheme was 783 ms, whereas the time overhead of the UDP-based SDP scheme was 1324 ms, representing a 41% reduction in time overhead compared to the UDP-based SDP scheme.

3.4. Comparison with QUIC Technology

Quick UDP internet connections (QUIC) is a transport protocol based on UDP proposed by Google, which combines the reliability of TCP and the efficiency of UDP. This protocol supports multiplexing and fast connection establishment, making it suitable for high-latency and high-loss network environments. QUIC is widely used in the field of anonymous access control, especially in the context of zero-trust architecture. QUIC’s core advantages lie in its low latency and security. Through reducing the number of handshakes (0-RTT or 1-RTT), QUIC reduces the connection establishment time. QUIC has built-in encryption and supports forward secrecy, mitigating man-in-the-middle and replay attacks.

Through the adoption of dual-mode single-packet authentication, the proposed scheme integrates authentication and encrypted communication into a single packet. In contrast, the QUIC protocol requires additional handshake processes to establish a connection and performs multiple data transmissions and re-transmissions to ensure the reliability and security of connections. Compared to the QUIC scheme, which necessitates extra handshake and data transmission procedures, the proposed approach reduces the communication overhead.

The proposed scheme allows users to complete the authentication process and access network resources more quickly, thus enhancing the user experience. In contrast, the QUIC scheme necessitates additional handshake and data transmission procedures, as well as complex encryption and decryption operations, resulting in a relatively lower access efficiency.

Compared to the QUIC scheme, this approach boasts clear advantages in terms of communication overhead and access efficiency. It is particularly well suited for scenarios requiring anonymous access control, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud computing, smart cities, and more. This scheme efficiently protects user privacy and enhances system security.

4. Conclusions

Zero-trust security applications face challenges due to diverse network risks, making user identity authentication and privacy protection crucial. The proposed dynamic anonymous access control method based on dual-mode single-packet authentication was shown to perform well, providing improved security compared to existing SDP schemes. It reduces the communication and computational overheads, thus improving access efficiency. However, the fuzzy logic design has some imperfections, which will be addressed in future research through refining the fuzzy rules and integrating other security mechanisms (e.g., anomaly detection), in order to enhance resilience against advanced attacks.

Despite these improvements, potential vulnerabilities remain. The system relies on the availability of the SDP gateway and controller, and their failure could interrupt the access control process. Additionally, the method requires both UDP and TCP support; as such, restrictions on either protocol may limit its applicability.

Future work should focus on strengthening the SDP gateway and controller infrastructure, enhancing the accuracy of user behavior data, and adapting the method to environments with restricted protocol support. Further research on the security of single-packet authentication (SPA) keys and certificates is also necessary. In conclusion, while the proposed method offers an efficient solution for dynamic anonymous access control, addressing these limitations is expected to further improve its adaptability and robustness in diverse network environments.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Project No. 2022YFB3104300).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

- Mekala, S.H.; Baig, Z.; Anwar, A.; et al. Cybersecurity for Industrial IoT (IIoT): Threats, countermeasures, challenges and future directions. Comput Commun. 2023, 208, 294–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Q.G.; Feng, G.; et al. A survey on attack detection, estimation and control of industrial cyber–physical systems. ISA Trans. 2021, 116, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serror, M.; Hack, S.; Henze, M.; et al. Challenges and opportunities in securing the industrial internet of things. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2020, 17, 2985–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, R.; Zeng, S.; Wang, Z.; et al. A comprehensive survey on blockchain in industrial internet of things: Motivations, research progresses, and future challenges. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2022, 24, 88–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, P.; Sib, a.M. Emerging trends and future directions of the industrial internet of things. In: From Internet of Things to Internet of Intelligence, 2024; 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Keb, e.V.R.; Awad, A.I. Industrial internet of things ecosystems security and digital forensics: achievements, open challenges, and future directions. ACM Comput Surv. 2024, 56, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, P.; Sangeetha, M.; Bhaskar, V. Blockchain for IoT access control, security and privacy: a review. Wirel Pers Commun. 2021, 117(3), 1815–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamanig, D.; Mir, O.; Mayrhofer, R. Threshold delegatable anonymous credentials with controlled and fine-grained delegation. IEEE Trans Dependable Secur Comput. 2023, 21, 2312–2326. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, T.; Zhang, Z.; Jing, C. Privacy-Preserving Educational Credentials Management Based on Decentralized Identity and Zero-Knowledge Proof. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Science and Education; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 243–255. [Google Scholar]

- De Santis, A.; Ferrara, A.L.; Masucci, B.; et al. An Information-Theoretic Approach to Anonymous Access Control. In: 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT), IEEE, 2024; 3326–3331. [Google Scholar]

- Paulraj, D.; Neelak, a.S.; Prakash, M.; et al. Admission control policy and key agreement based on anonymous identity in cloud computing. J Cloud Comput. 2023, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCusatis, C.; Liengtiraphan, P.; Sager, A.; et al. Implementing zero trust cloud networks with transport access control and first packet authentication. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Smart Cloud (SmartCloud), New York, USA; Pagination: 5–10.

- Eidle, D.; Ni, S.Y.; DeCusatis, C.; et al. Autonomic security for zero trust networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE 8th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), New York, USA; Pagination: 288–293.

- Yang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yang, Y.; et al. A survey of information extraction based on deep learning. Appl Sci. 2022, 12, 9691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, M.; Battaglioni, M.; Chiaraluce, F.; et al. A new path to code-based signatures via identification schemes with restricted errors. arXiv arXiv:2008.06403, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Shen, Y. Endpoint security reinforcement via integrated zero-trust systems: A collaborative approach. Comput Secur. 2024, 136, 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Xie, X.; Wang, Z.; Feng, J.; Han, G.; Zhang, W. ZT-Access: A combining zero trust access control with attribute-based encryption scheme against compromised devices in power IoT environments. Ad Hoc Netw. 2023, 145, 103161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, Z.; et al. Flowgananomaly: Flow-based anomaly network intrusion detection with adversarial learning. Chin J Electron. 2024, 33, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Chen, B.; Tan, Z.; et al. AHAC: Advanced Network-Hiding Access Control Framework. Appl Sci. 2024, 14, 5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, M.; et al. A novel network flow feature scaling method based on cloud-edge collaboration. In: Proceedings of the IEEE 22nd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Location of Conference, Country, 2023; Pagination: 1947–1953.

- Wang, Z.X.; Li, Z.Y.; Fu, M.Y.; et al. Network traffic classification based on federated semi-supervised learning. J Syst Archit. 2024, 149, 103091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, N.F.; Shah, S.W.; Shaghaghi, A.; et al. Zero trust architecture (zta): A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access. 2022, 10, 57143–57179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; et al. Privacy-aware traffic flow prediction based on multi-party sensor data with zero trust in smart city. ACM Trans Internet Technol. 2023, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, W.; Buchanan, W.J.; Ahmad, J. An authentication protocol based on chaos and zero knowledge proof. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 99, 3065–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Guo, J.; Yuan, H.; et al. Zero-Trust Security Authentication Based on SPA and Endogenous Security Architecture. Electronics. 2023, 12, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, K.; Arshad, J.; Chaudhry, S.A.; et al. An enhanced anonymous identity-based key agreement protocol for smart grid advanced metering infrastructure. Int J Commun Syst. 2019, 32, e4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Ma, C.; Cheng, K. Privacy-preserving authentication scheme based on zero trust architecture. Dig Commun Netw. 2024, 10(5), 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yan, L.; Lü, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, W.; Xuan, J. Research on Zero-trust Security Protection Technology of Power IoT based on Blockchain. J Phys: Conf Ser. 2021, 1769, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Qiao, S.; Zhao, J.; et al. A security awareness and protection system for 5G smart healthcare based on zero-trust architecture. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 10248–10263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Pang, J.; Cheng, K.; et al. Multiauthority traceable ring signature scheme for smart grid based on blockchain. Wirel Commun Mob Comput. 2021, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; et al. A universal designated multi verifiers content extraction signature scheme. Int J Comput Sci Eng. 2020, 21, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, M.; Wang, P.; et al. Multi-ARCL: Multimodal adaptive relay-based distributed continual learning for encrypted traffic classification. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 2025, 201, 105083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).