1. Introduction

Wildfires represent a significant environmental challenge in the 21st century, characterized by a notable increase in both frequency and intensity in recent decades. In this context, climate change is considered the primary source of global temperatures and prolonged droughts, which facilitate the ignition and swift propagation of fires. Climatic changes have altered natural fire regimes, leading to extended fire seasons and increased impacts on ecosystems and communities globally [

1,

2,

3]. Wildfires result in both immediate casualties and property damage, while also emitting significant amounts of carbon dioxide, thereby intensifying climate change. Long-term ecological consequences, such as biodiversity loss, soil degradation, and water contamination, disrupt ecosystems and affect livelihoods [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. In addition, the rising economic costs associated with firefighting, infrastructure repair, and adaptation underline the necessity for comprehensive wildfire management strategies that include prevention, mitigation, and the cumulative impacts of urban development and climate change [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The expansion of urban areas into natural landscapes has increased the risks of wildfires, particularly in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), where human activities overlap with fire-prone vegetation. Accelerated urbanisation has increased human-induced ignitions and heightened the vulnerability of individuals and infrastructure to fire hazards [

7,

14,

15,

16]. Unregulated construction and inadequate land-use planning have also led to community encroachment into high-risk areas, thereby perpetuating a cycle of vulnerability. This pattern is particularly concerning in developing regions, where limited resources often constrain mitigation and response strategies.

The Andean region, characterised by intricate topography and climate, is witnessing an increase in wildfire risks attributed to the interplay of environmental and anthropogenic factors. Ambato, located in the central highlands of Ecuador, illustrates these challenges. This city in the Andes Mountains serves as a relevant case study for examining the impact of regional factors on fire safety. The growth of urban regions into natural landscapes has heightened the risks of wildfires, especially in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), where human activities intersect with fire-prone vegetation [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Accelerated urbanisation in Andean cities has raised the probability of human-induced ignitions and increased the susceptibility of populations and infrastructure to fire hazards [

17,

18,

19,

21,

22]. Unregulated construction and inadequate land use planning, driven by socioeconomic demands, disrupt ecosystems through practices such as slash-and-burn agriculture, deforestation, and uncontrolled grazing [

7,

14,

15,

16,

23,

24]. Moreover, deficiencies in policy enforcement and constrained resources for mitigation strategies intensify vulnerability in a cyclical fashion [

13,

25,

26,

27]. The increasing complexity of wildfire risks in Ambato necessitates the integration of advanced tools such as spatial analysis and machine learning to provide critical insights for mitigation efforts.

The wildfire risk in Ambato arises from a complex interplay of biological, meteorological, and topographic factors. The grasslands, shrublands, and dry forests of the region exhibit considerable combustibility during extended dry seasons, a condition exacerbated by climate-related temperature anomalies and inconsistent precipitation patterns [

17,

19,

20]. Human activities such as agricultural deforestation and unregulated grazing destabilize ecosystems and increase fuel loads. Furthermore, prolonged droughts reduce vegetation moisture, disrupt hydrological cycles, and strain water resources critical for fire management. Seasonal winds, amplified by the steep slopes of the Andes, facilitate the spread of fire, while temperature extremes condition fuels, thereby increasing the potential for ignition. In addition, global climate change has intensified conditions in Ambato, resulting in prolonged droughts and irregular rainfall that extend fire seasons and decrease the effectiveness of conventional mitigation strategies [

17,

19,

20]. The expansion of urban areas into the wildland-urban interface has markedly increased human susceptibility to fire hazards. Informal settlements, agricultural encroachment, and the proliferation of flammable vegetation in residential landscaping practices elevate fuel loads near populated areas [

14,

24,

28]. Moreover, inadequate financial resources hinder access to essential firefighting infrastructure, including water sources, equipment, and trained personnel.

This research evaluates wildfire risk in Ambato, emphasising the interaction of environmental, meteorological, and socio-economic factors. The primary objective is to identify high-risk zones in the Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) where human activities intersect with natural landscapes, thereby increasing susceptibility to fire. This research utilises a multidisciplinary framework, incorporating geospatial analysis, climatic data, and socio-economic metrics. Spatial variables, including vegetation cover, altitude, land use patterns, and population density, were analysed alongside climatic data, such as temperature anomalies and precipitation deficits, to categorise risks into five tiers: very low, moderate, high, and very high. Multinomial logistic regression identified high-risk areas within the wildland-urban interface, where human activity intersects with fire-prone landscapes. Wildfire management policies in Ecuador often lack sufficient specificity and enforcement mechanisms, hindering effective responses. National initiatives focused on reforestation and community education frequently neglect the distinct challenges presented by the wildland–urban interface, a critical factor in wildfire risk in Ambato [

17,

19]. The inadequate enforcement of land-use planning restrictions to restrict urban expansion into high-risk zones facilitates the encroachment of settlements in fire-prone areas. Furthermore, regulations governing agricultural practices, such as the ban on slash-and-burn techniques, are often inadequate, resulting in the possibility of fire hazards.

International case studies offer significant insights for mitigating wildfire risks in areas such as Ambato. Studies conducted in Spain indicate that unregulated urban growth in fire-prone regions markedly heightens vulnerability at the wildland-urban interface (WUI). Policies that prioritise improved urban planning, enforce stricter land use regulations, and promote active community engagement have demonstrated effectiveness in minimising ignition sources and controlling fire spread [

3,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Research conducted in the United States has led the development of geospatial tools and predictive models to identify high-risk areas and optimise the allocation of firefighting resources. Initiatives such as Firewise USA underscore the significance of community preparedness, demonstrating how local efforts can strengthen wider policy frameworks for wildfire resilience [

8,

34,

35,

36]. The Andean region, encompassing Ambato, poses specific challenges attributable to its unique climatic and topographical characteristics. Andean regions like Ambato, akin to Mediterranean areas, undergo prolonged droughts that increase vegetation flammability. Furthermore, steep slopes and seasonal winds, similar to those found in the western United States, promote rapid fire spread and hinder containment efforts. The identified parallels highlight the necessity of customising global strategies, including fuel management programs, predictive mapping, and machine learning integration, to specific local contexts. The socioeconomic conditions of the Andes require cost-effective strategies, such as modernising infrastructure, investing in water storage systems, acquiring firefighting equipment, and implementing satellite-based early detection technologies [

17,

18,

21,

22]. In addition, community resilience programs, such as public education campaigns designed to mitigate anthropogenic ignition (e.g., waste burning) and training residents in fire response protocols, could provide culturally and economically sustainable solutions for Ambato and comparable areas [

17,

18,

19].

The wildfire risks in Ambato exemplify the broader challenges faced in the Andean regions, marked by the interaction of climate change, ecological degradation, and socio-economic disparities. This study introduces a scalable framework for detecting vulnerabilities and prioritizing mitigation through data-driven, context-specific approaches. Aligning local actions with global best practices, such as predictive modelling, community-centric preparedness, and adaptive land use policies, enhances resilience in Ambato and offers a replicable model for neighbouring regions. Furthermore, future research should focus on the integration of traditional ecological knowledge, particularly indigenous fire management practices, with machine learning algorithms to enhance risk prediction and optimize resource allocation. Innovations are essential in the context of escalating climatic uncertainty, requiring comprehensive, interdisciplinary approaches to safeguard ecosystems and vulnerable human populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

This study analyses historical wildfire data from Ambato to provide insights into the location, frequency, causes, and effects of previous events. This information was compiled from the Ambato Fire Department (Cuerpo de Bomberos Ambato) using public records available on their official website [

37]. These records enabled the identification of high-risk areas, ignition points, and burnt area extents. Key causes, such as waste burning, agricultural practices, and electrical malfunctions, were mapped to understand temporal and spatial wildfire trends. Additionally, seasonal patterns and the influence of extreme climatic conditions on ignition rates were assessed. Socioeconomic variables—including population density, land-use changes, and infrastructure proximity—were incorporated to analyse anthropogenic influences on wildfire occurrence. The combined use of historical datasets provides a foundational understanding of wildfire behaviour at the urban–wildland interface (WUI) in Ambato, supporting risk assessments and the development of targeted mitigation strategies [

37].

Climatic data were obtained from the Government of Tungurahua’s meteorological stations, accessible through their official website [

38]. This dataset includes temperature, precipitation, humidity, and wind speed, which are crucial parameters for assessing wildfire risks. The data were analysed to identify prolonged drought periods, temperature anomalies, and irregular precipitation patterns, which increase vegetation desiccation and fire susceptibility.

Table 1 presents the key climatic variables recorded by meteorological stations in Ambato, including relative humidity, daily precipitation, wind speed, and temperature. These variables are essential for understanding the role of climatic conditions in wildfire risk assessment, as they influence fuel moisture, fire spread potential, and ignition probability. The data allow for the detection of microclimatic variations across different areas of the city, providing valuable insights into localised wildfire hazards.

Another critical parameter for wildfire risk assessment is vegetation cover. High-resolution satellite imagery and land cover classifications were acquired from the Municipality of Ambato’s geoportal [

39]. These datasets provided essential information about vegetation composition, fuel density, and spatial distribution. To quantify vegetation health, the Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) was used, enabling the identification of areas experiencing stress or degradation, which are particularly susceptible to ignition. Additionally, spatial datasets allowed for the identification of areas with increased fuel availability, enhancing the understanding of wildfire dynamics.

Land-use data were sourced from the Municipality of Ambato’s cadastral geoportal cartographic databases [

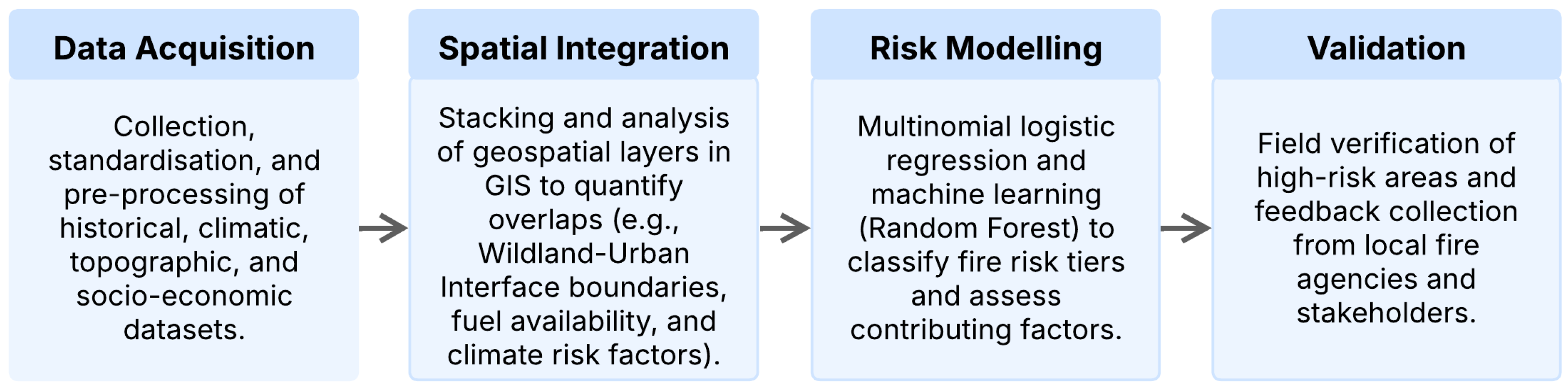

39]. These geospatial datasets classify land into agricultural zones, urban developments, and natural landscapes, which were validated through local surveys and field observations. Unregulated land-use changes—such as urban expansion into fire-prone areas and agricultural encroachment—were identified as significant contributors to wildfire vulnerability. Furthermore, the proximity of urban areas to combustible vegetation within the WUI was assessed to determine high-risk zones. The integration of land-use data into wildfire risk assessments enhances the understanding of how human activities alter natural landscapes, exacerbating wildfire hazards. The methodology followed a structured process, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

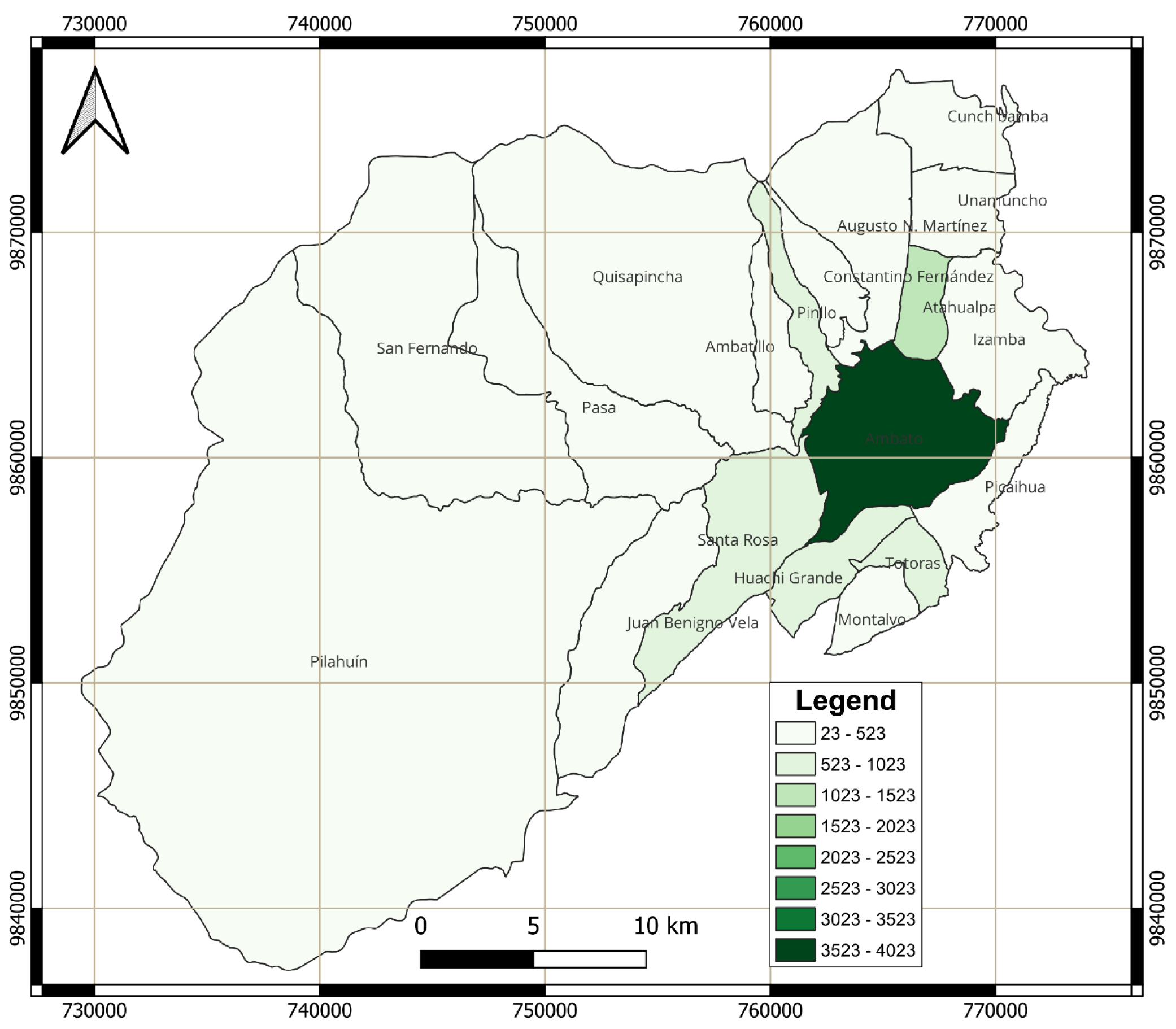

Population density was incorporated as a key variable in wildfire risk evaluation, as human activities directly influence ignition probabilities. Demographic datasets were obtained from the Municipality of Ambato’s geoportal [

39]. These data were overlaid onto land-use and vegetation maps to analyse the correlation between high-density settlements and proximity to fire-prone areas. Informal settlements within the WUI, often lacking fire prevention infrastructure, were classified as high-vulnerability zones. Integrating these demographic variables with environmental factors strengthened risk assessments and facilitated targeted mitigation strategies.

Datasets on vegetation cover, land use, and population density were unified into a geospatial framework to analyse the interplay between natural and anthropogenic factors. This integration allowed the identification of overlapping vulnerabilities, such as high-density populations adjacent to degraded vegetation or urban expansion into fire-prone areas. Geospatial analysis tools, including heat maps and risk overlays, were employed to visualise these interactions and generate actionable insights for targeted interventions [

37,

38,

39].

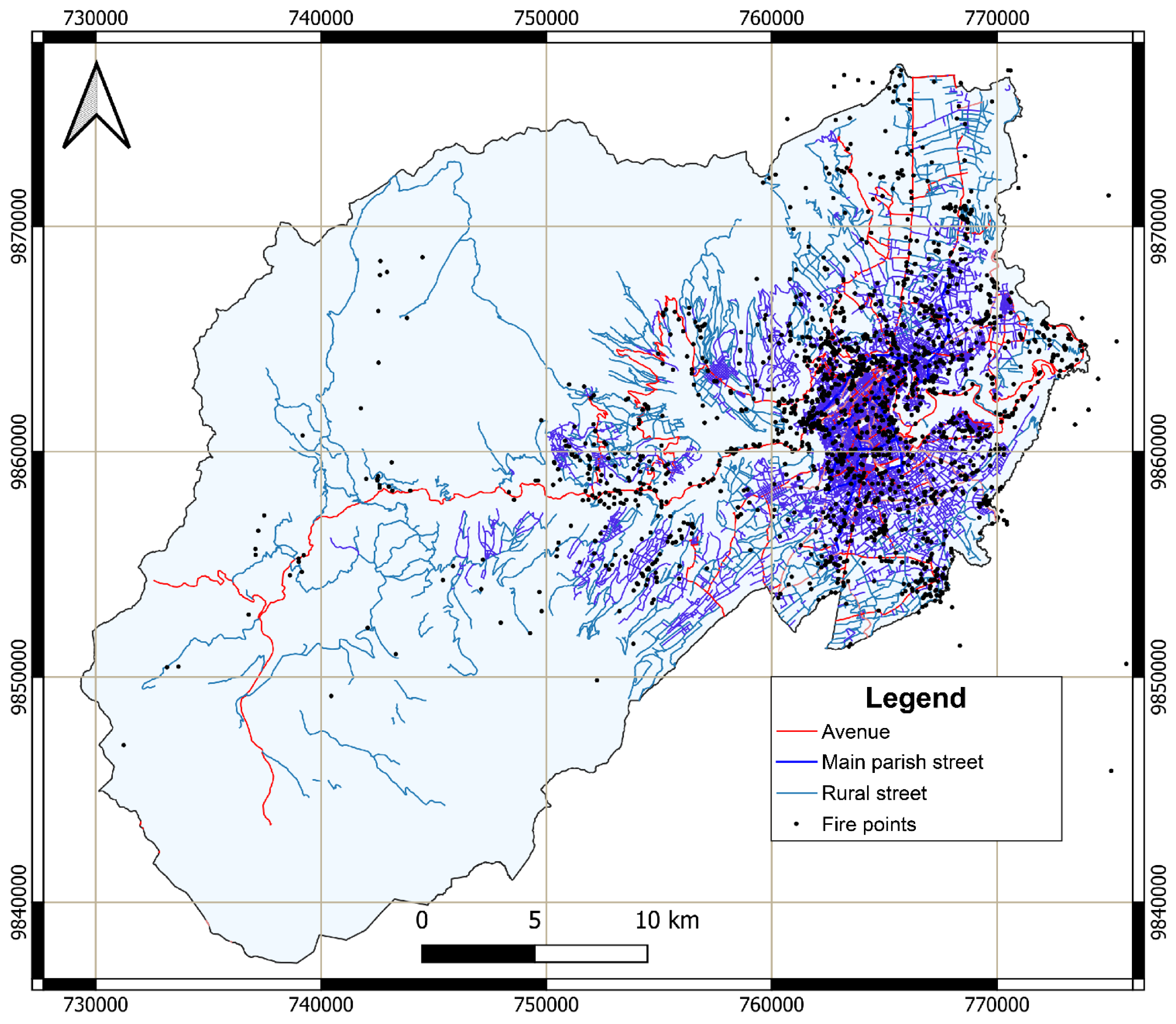

The spatial distribution of roads and potential fire ignition points, which are critical for both accessibility and wildfire prevention, is displayed in

Figure 2. Road infrastructure plays a crucial role in fire response times and evacuation planning. The analysis considered major roads, rural pathways, and their proximity to high-risk fire zones, ensuring that fire response strategies are optimised based on accessibility constraints.

2.2. Spatial and Climatic Data Processing

This study employs Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to integrate and visualise multiple data layers, including vegetation cover, land use, population density, and historical wildfire occurrences. Advanced spatial analysis techniques, such as hotspot mapping and buffer analysis, enable the identification of high-risk wildfire zones, particularly within the wildland-urban interface (WUI) [

16,

33,

40,

41]. The study applies geospatial interpolation techniques to model the interaction between climatic, environmental, and socioeconomic factors, allowing for a more precise assessment of wildfire risks and supporting targeted mitigation efforts (reference). The application of GIS ensures spatial accuracy in wildfire risk evaluation, improving planning processes and resource allocation strategies [

42,

43,

44].

Figure 1.

Methodological Process for Wildfire Risk Assessment.

Figure 1.

Methodological Process for Wildfire Risk Assessment.

To enhance the precision of risk assessments, the study segments Ambato into polygons of 1 km², capturing micro-scale variations in environmental, climatic, and socio-economic conditions. This spatial division facilitates the integration of multiple geospatial data sources, including altitude, proximity to rivers, and land-use classifications. Each polygon is characterized by attributes such as average temperature, precipitation, wind speed, vegetation cover, and population density, derived from official data sources, including meteorological records from the Government of Tungurahua, and demographic and cadastral data from the Municipality of Ambato [

38,

39]. The processed GIS data allows for the generation of thematic maps that highlight areas with increased fire susceptibility, revealing spatial correlations between climatic conditions, land-use changes, and socio-economic variables [

41,

42,

43,

44].

The segmentation approach also supports the integration of additional socio-economic factors, such as cadastral land value and infrastructure accessibility, enriching the predictive capacity of the analysis. The unified geospatial framework enhances the understanding of wildfire risk across Ambato by identifying high-vulnerability zones, particularly in informal settlements within the WUI. These areas often lack fire prevention infrastructure and are more exposed to human-driven ignition sources, reinforcing the importance of integrating demographic and environmental data in wildfire risk assessments. The combination of natural and anthropogenic variables offers a comprehensive understanding of wildfire behaviour, providing essential information for improving urban planning, emergency preparedness, and fire mitigation strategies [

14,

45,

46].

Figure 2.

Road Network and Fire Ignition Points in Ambato.

Figure 2.

Road Network and Fire Ignition Points in Ambato.

2.3. Predictive Modelling and Risk Analysis with Machine Learning

This study employs machine learning models to enhance predictive accuracy and spatial delineation of wildfire risks. Algorithms such as Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR), Random Forest (RF), and XGBoost were applied to large datasets encompassing climatic, vegetation, land-use, and socio-economic variables, identifying the most influential factors driving wildfire occurrences. These models generated risk maps that highlight vulnerable regions based on historical wildfire data and projected scenarios. Supervised learning techniques, including clustering, were utilised to detect emerging patterns in wildfire frequency and severity, improving upon traditional risk assessment methods by offering high-resolution spatial classifications. This analytical framework enhances both immediate response strategies and long-term wildfire mitigation planning [

43,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51].

To classify risk levels, Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR) (Equation 1) was employed, estimating the probability of an area belonging to a specific risk category based on key predictive variables, including humidity, temperature, precipitation, wind speed, and terrain attributes. The logistic regression function is defined as follows:

where P(y=1|X) represents the probability of an observation belonging to a wildfire risk category, given the predictor variables

, and

are the regression coefficients estimated during model training. While MLR allows for clear interpretation of individual variable contributions, its performance is limited in capturing non-linear relationships between wildfire determinants.

To improve predictive accuracy and account for complex variable interactions, ensemble models were introduced. Random Forest (RF) was employed due to its robustness in reducing overfitting by aggregating multiple decision trees trained on random samples. This approach was particularly effective in modelling the interaction between topographic features and proximity to ignition sources (roads, electrical infrastructure). In contrast, XGBoost, an optimised gradient boosting algorithm, improved predictive power by iteratively correcting model errors and applying regularisation techniques to enhance generalisation.

A multi-layered modelling approach integrating climatic, spatial, and socio-economic data was implemented for comprehensive wildfire risk assessment. GIS-enabled overlays facilitated the spatial correlation of vegetation indices (NDVI), land-use classifications, and demographic factors with wildfire occurrences, enhancing risk map generation. Machine learning models identified significant non-linear interactions between climatic, anthropogenic, and environmental variables, refining the classification of wildfire-prone regions.

The study area was segmented into 1 km² grid cells, enabling micro-scale analysis of wildfire risk. Each cell was classified into one of five risk levels—‘Very Low,’ ‘Low,’ ‘Moderate,’ ‘High,’ and ‘Very High’—based on predictive variables, including humidity, temperature, wind speed, altitude, proximity to roads, land use, and cadastral land value. This spatial segmentation ensures a high level of granularity and precision in the identification of critical wildfire zones, improving the effectiveness of risk mitigation strategies and resource allocation for fire prevention in Ambato.

2.4. Validation and Analysis

Machine learning models and simulation outputs are evaluated using historical wildfire data, comparing predicted fire occurrences with recorded events to assess model performance [

47,

48,

49]. Machine learning algorithms use metrics such as accuracy, precision, and recall evaluating their predictive capabilities, while sensitivity analyses assess the robustness of simulation models under different conditions.

Outputs from GIS, machine learning, and simulation models are integrated to generate comprehensive risk maps and scenario analyses. The results highlight the spatial distribution of risks, identifying regions where climatic, environmental, and socio-economic factors intersect, leading to increased vulnerabilities. The study also evaluates the effectiveness of proposed mitigation strategies, such as controlled burns and urban planning policies, through simulation models to predict their impact across various scenarios.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of High-Risk Areas

The thematic risk maps generated from the integration of climatic and socio-economic data identified significant high-risk zones within the urban–wildland interface of Ambato. These zones, characterised by dense vegetation cover, proximity to human settlements, and climatic conditions conducive to ignition, were predominantly located in areas with high population density and active land-use changes. By segmenting the study area into 1 km² grid cells, micro-scale variations in risk levels were visualized. The analysis classified these cells into five categories: ’Very Low’, ’Low’, ’Moderate’, ’High’, and ’Very High’. Results revealed that areas with ’Very High’ risk were concentrated near agropastoral lands and unregulated urban expansions, often correlating with zones of low precipitation and high temperature anomalies. These insights provide a detailed spatial understanding of wildfire susceptibility, enabling targeted mitigation efforts in particularly vulnerable areas.

By superimposing socio-economic data onto these risk maps, a deeper understanding of how human activities increase wildfire hazards was achieved. This geospatial analysis not only identifies high-risk locations but also stablishes direct correlations between environmental conditions and anthropogenic factors.

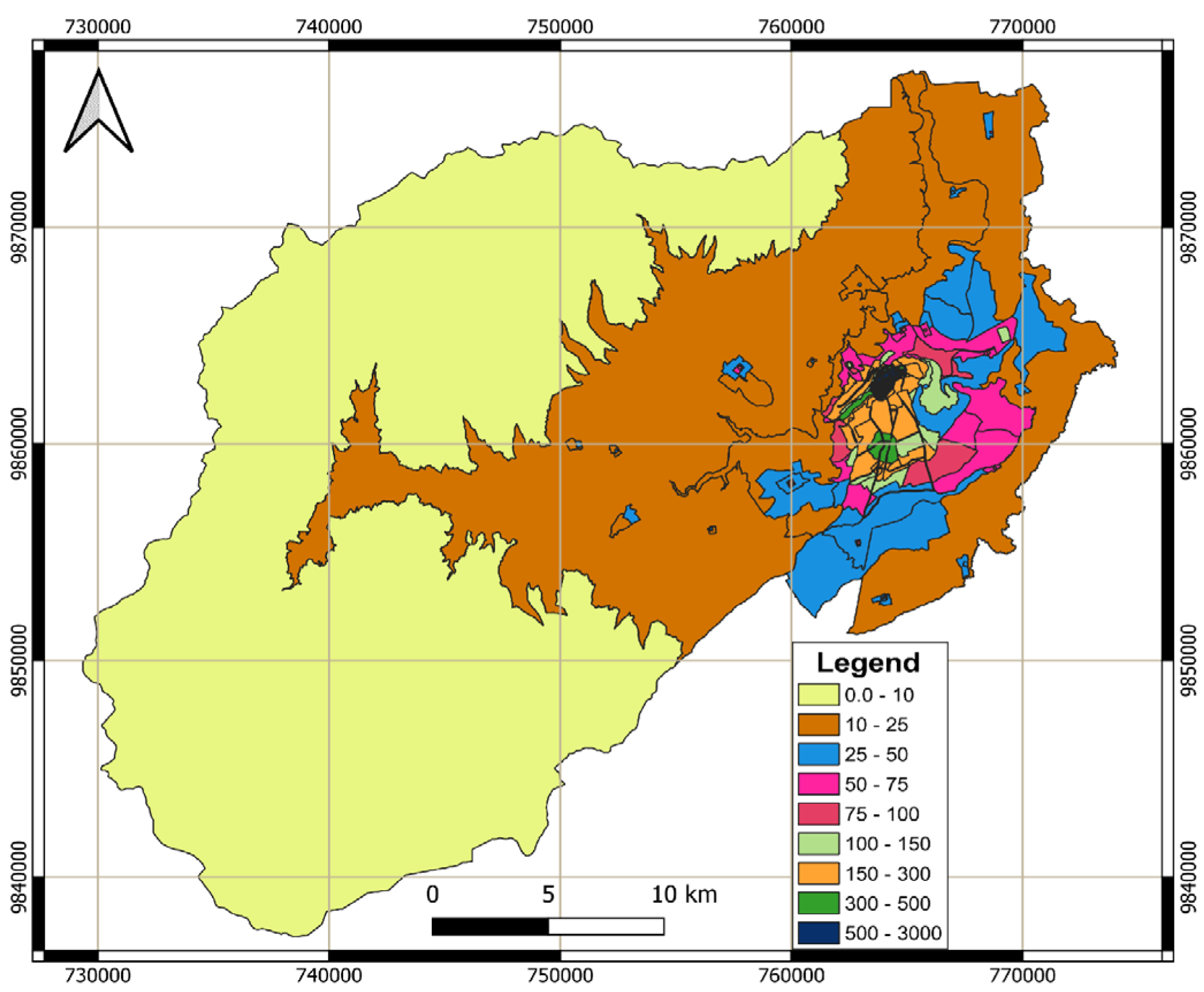

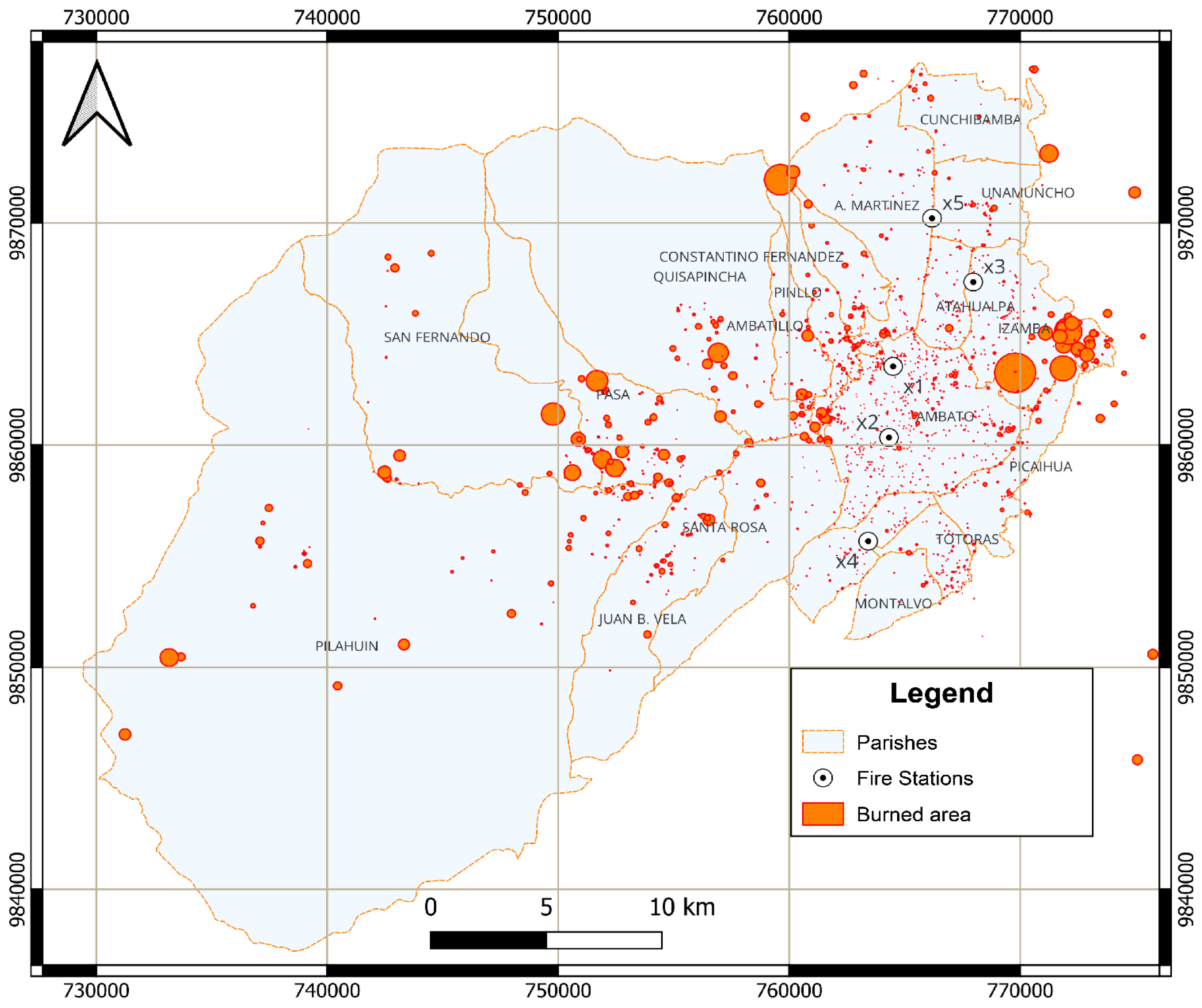

Figure 3 displays the spatial distribution of burned areas in Ambato.

Table 2 presents the total burned area (in hectares) per parish in Ambato between 2017 and 2023. Izamba parish was the most affected parish, with a total of 884.9 hectares burned, with 2020 being the most critical year (609 hectares burned). Similarly, the parishes of Pasa and San Fernando recorded a total of 598.2 hectares burned. In Pasa parish, the peak wildfire occurrence was in 2023, with 156.5 hectares affected, whereas in San Fernando parish, the most severe impact occurred in 2020, with 150.8 hectares burned. To evaluate potential correlations between human activities and wildfire occurrence, an additional variable was incorporated into the analysis: the number of households engaged in open waste burning. This spatial overlap suggests a plausible link between informal waste disposal and wildfire ignition, particularly in years with prolonged droughts (e.g., 2020).

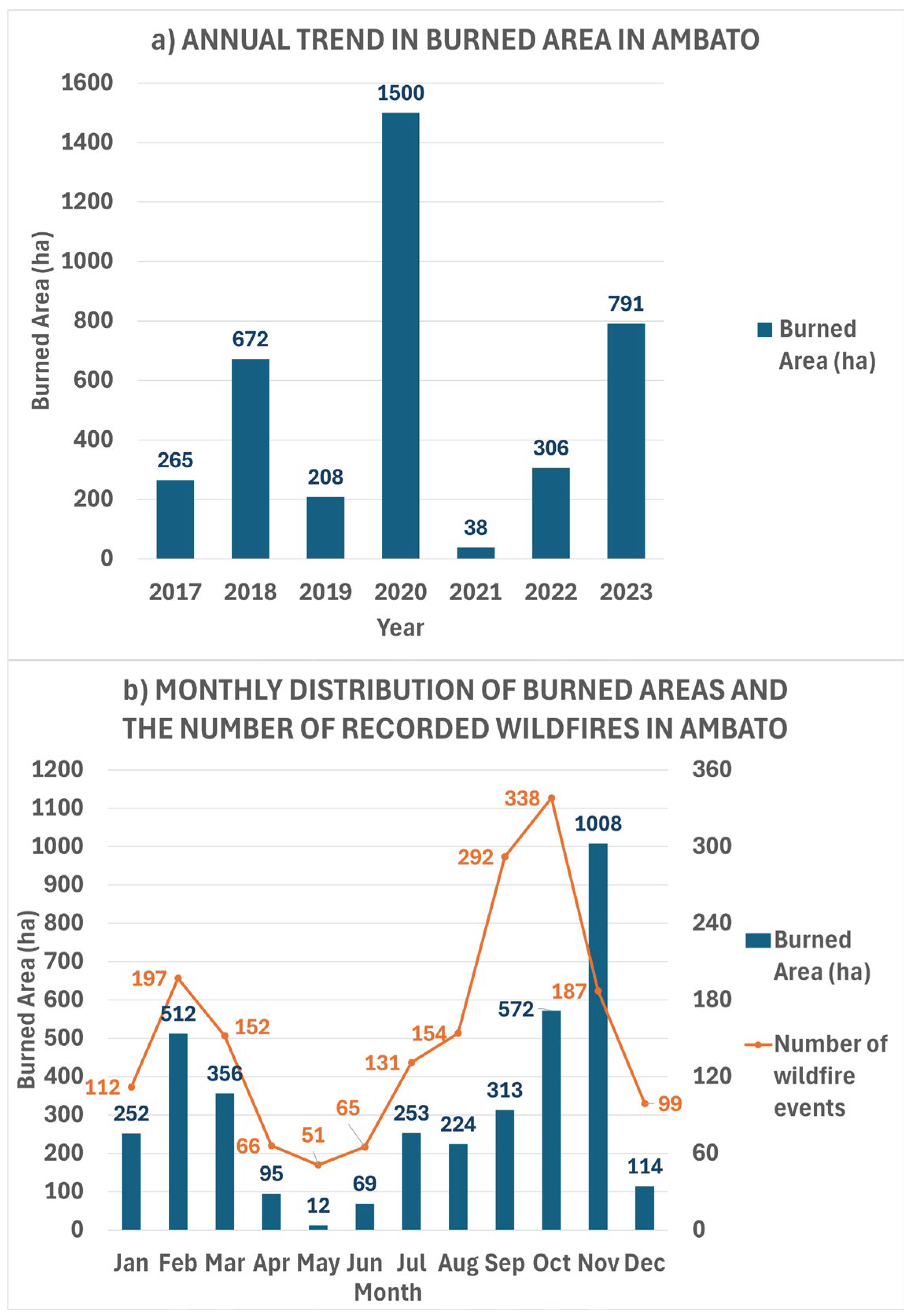

Figure 4a illustrates the annual trend in burned area, highlighting 2020 as the most severe year, with a total of 1,500 hectares burned, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic. This is followed by 2023, with 791 hectares affected. Meanwhile,

Figure 4b details the monthly distribution of burned areas and the number of recorded wildfires. November emerges as the most critical month, with 1,008 hectares burned and 187 wildfires reported, coinciding with the peak solar radiation period. October also shows high wildfire incidence, with 572 hectares affected and 338 wildfires recorded, indicating a clear seasonal pattern in wildfire occurrence.

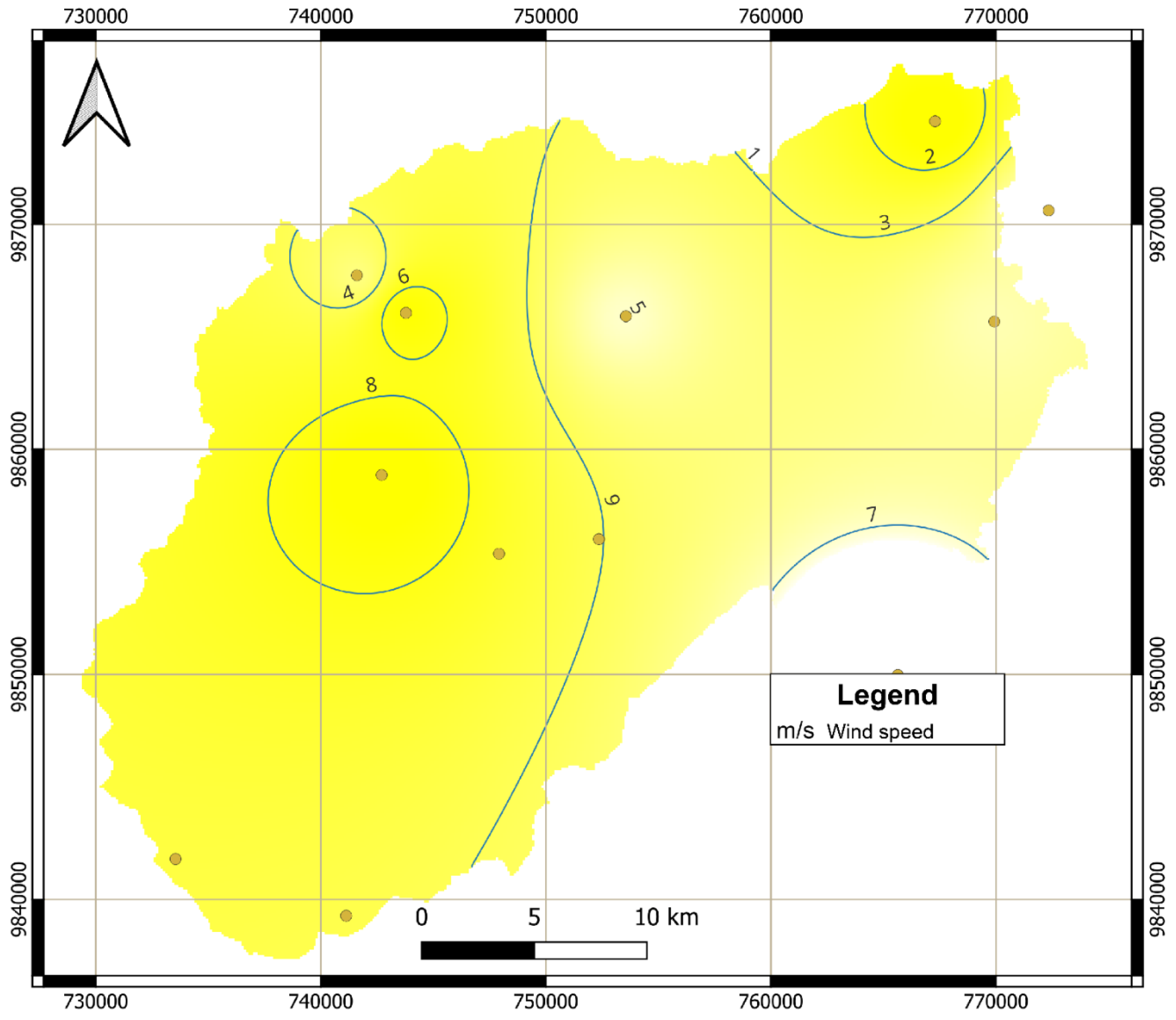

Additional thematic maps were generated to illustrate the increased wildfire risk in rapidly urbanising regions. The expansion of residential developments into natural areas disrupts ecological balance, increasing the availability of combustible materials such as organic waste and dry vegetation [

10,

15]. These maps serve as a critical tool for policymakers, allowing them to prioritise mitigation strategies in the most vulnerable areas and allocate resources effectively. Wind speed distribution was analysed to identify areas where fire spread could be accelerated. Strong winds significantly influence wildfire behaviour by intensifying flame propagation and increasing ember transport over long distances.

Figure 5 highlights wind speed variations across the city, emphasising areas particularly susceptible to rapid fire expansion.

Prolonged droughts significantly impact fuel availability and moisture retention, increasing wildfire risk in Ambato. Climatic records indicate that dry periods are becoming more frequent and extended, reducing vegetation moisture content and intensifying flammability, particularly in grasslands and shrublands.

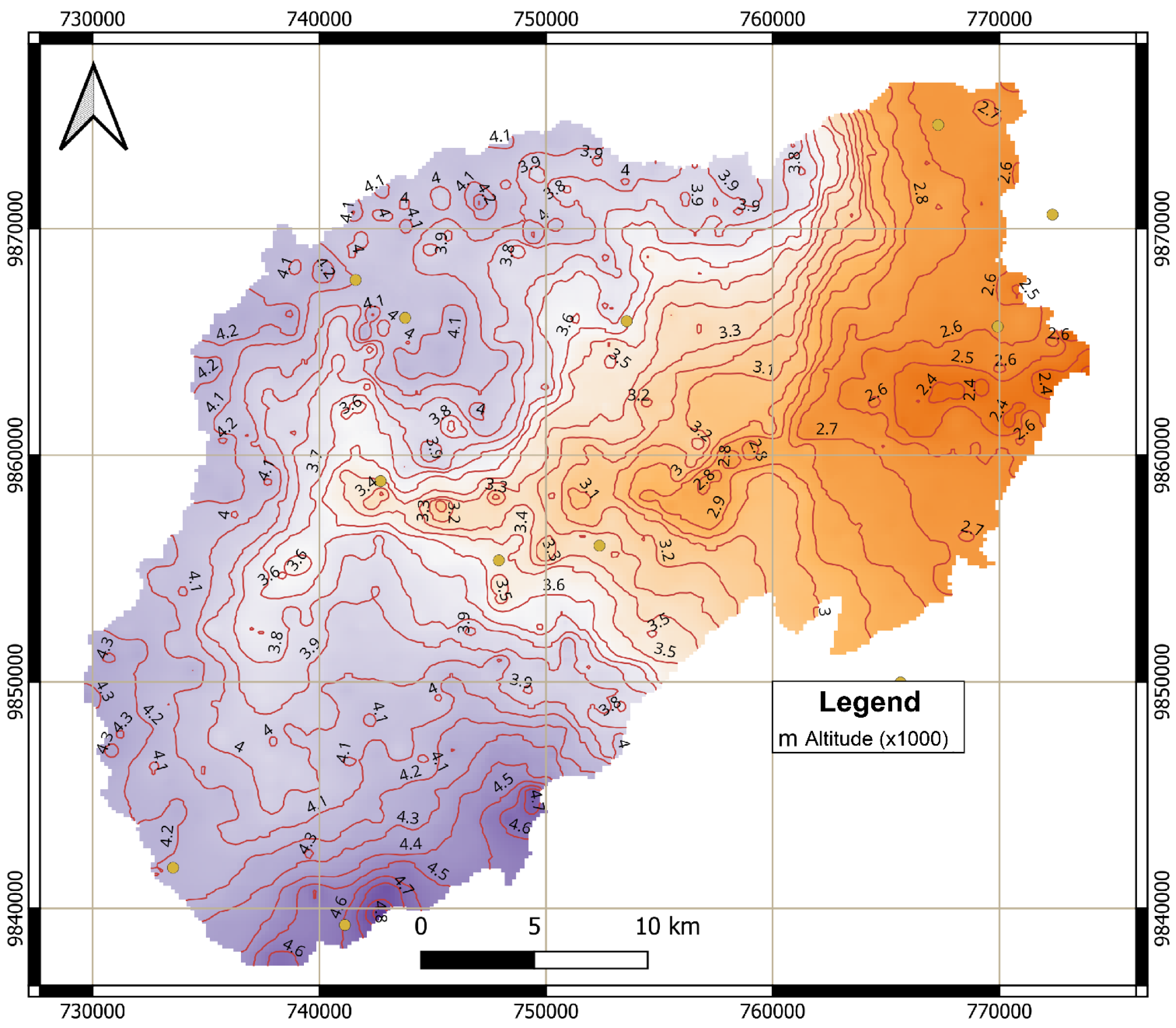

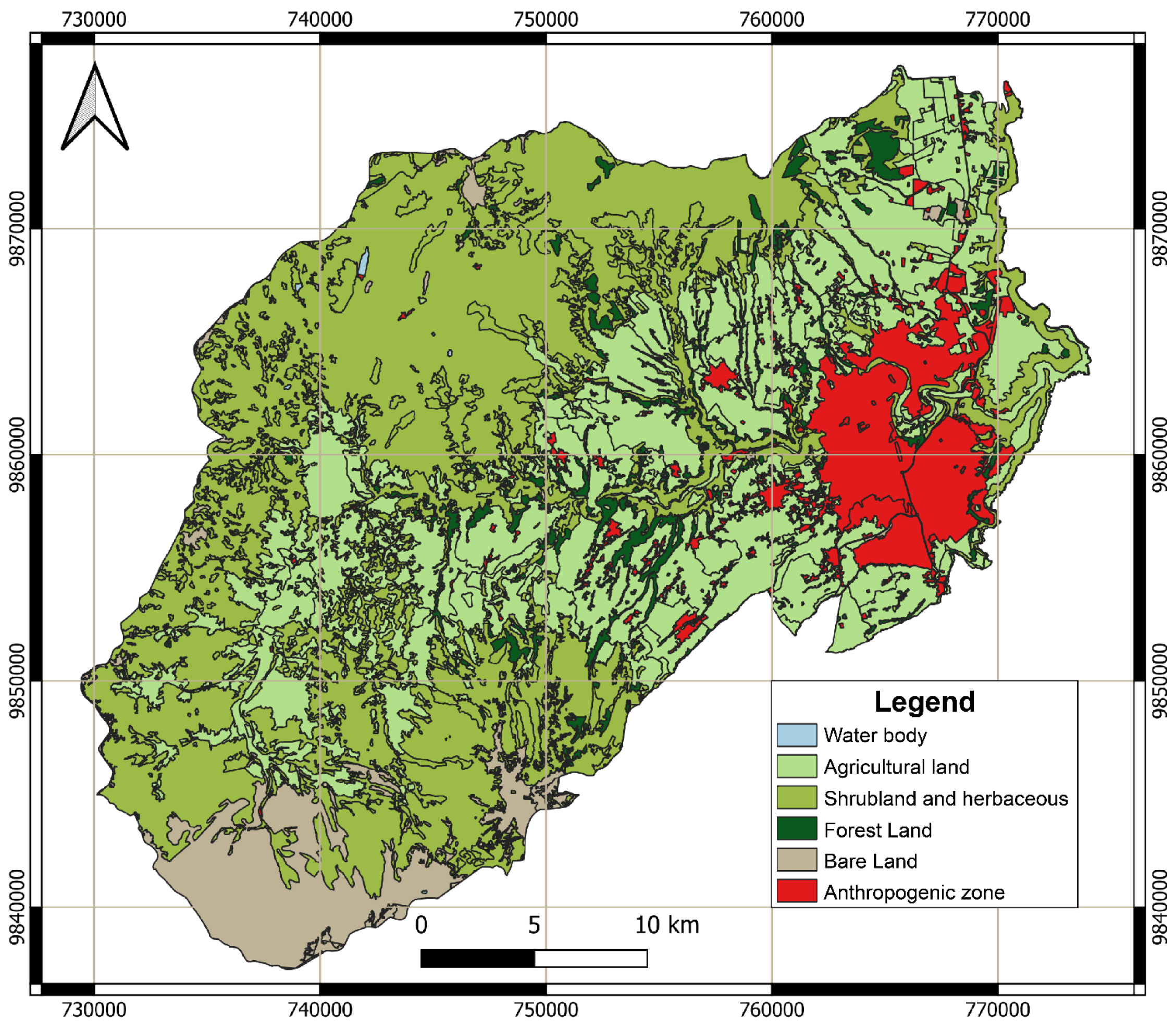

Figure 6 illustrates vegetation cover and its relationship to high-risk zones, highlighting areas with reduced moisture and increased fuel accumulation. Additionally,

Figure 7 presents the altitudinal distribution across the study area, demonstrating how elevation influences fire susceptibility by shaping local climatic conditions and fuel dynamics.

3.2. Climatic Factors

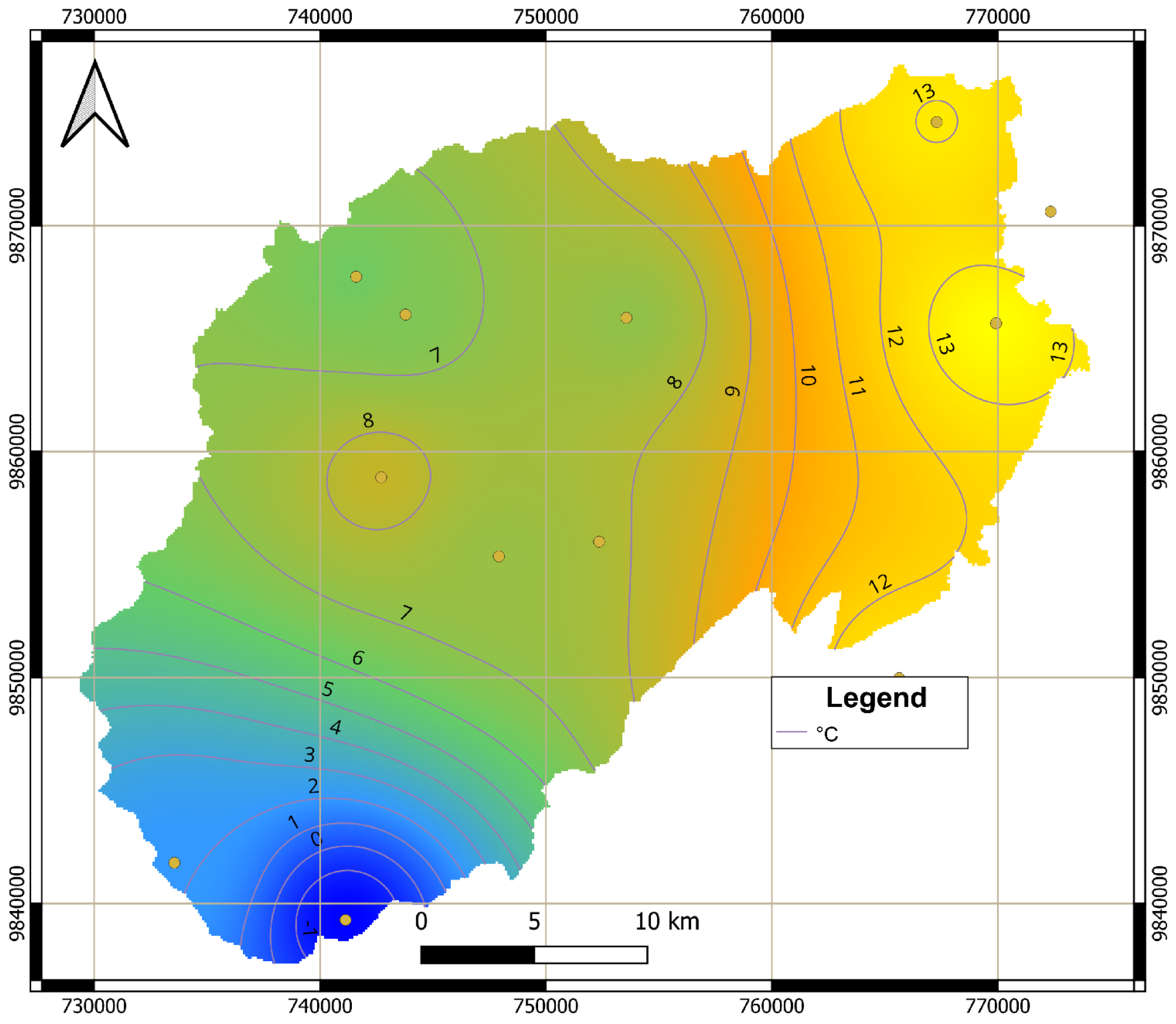

Climatic variability plays a pivotal role in shaping wildfire dynamics in Ambato, with temperature anomalies emerging as a key driver of vegetation desiccation and increased flammability. Analysis of historical temperature records reveals a persistent upward trend, with extreme heat events accelerating moisture loss in grasslands and shrublands. These conditions create highly combustible environments, particularly in regions experiencing prolonged dry spells.

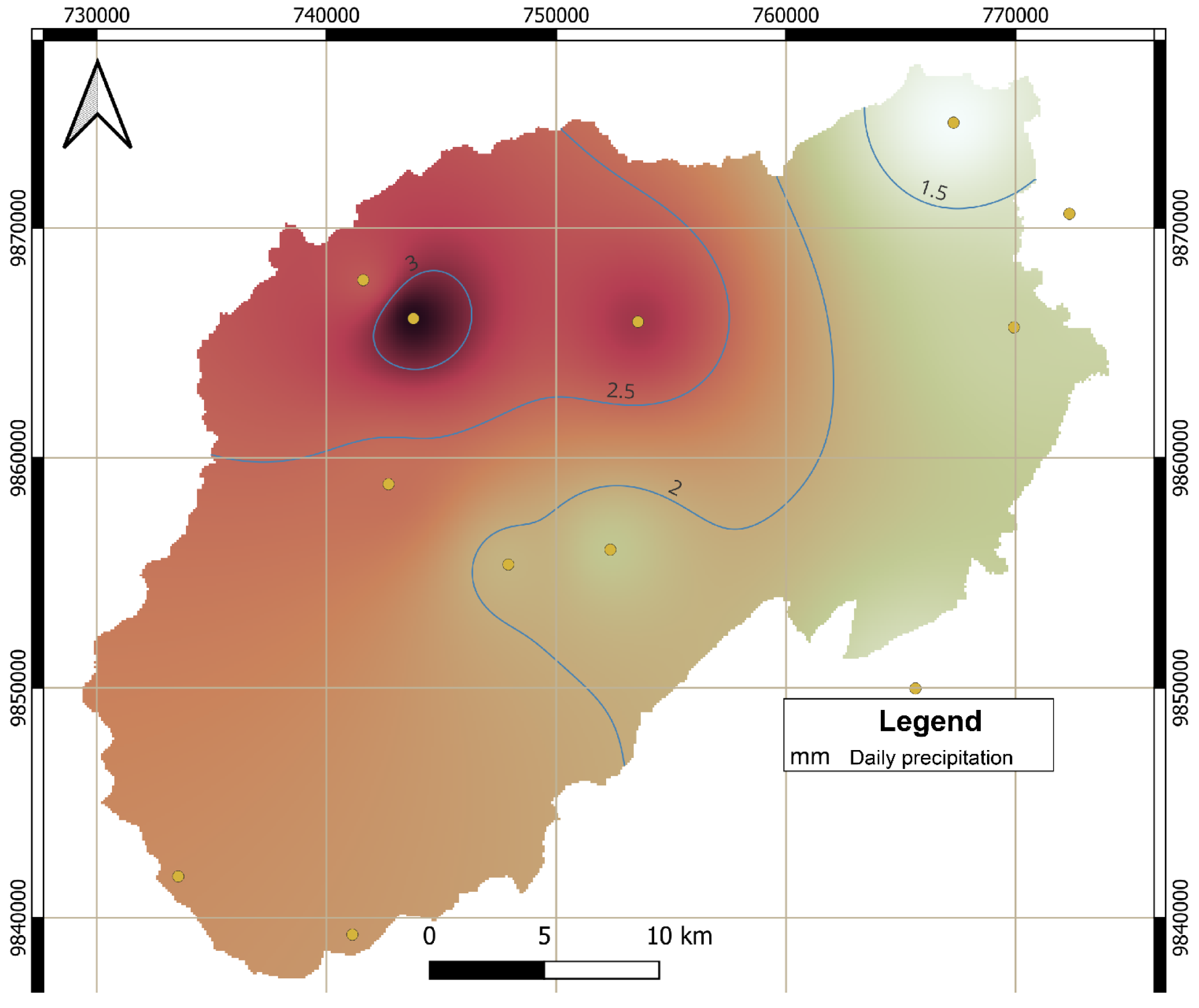

Figure 8 illustrates the spatial distribution of average temperatures across the canton, highlighting the correlation between heat-intensified fuel desiccation and wildfire-prone areas. Additionally, precipitation deficits exacerbate fire susceptibility by reducing soil moisture and delaying vegetation recovery after fire events.

Figure 9 presents the temporal distribution of rainfall patterns, demonstrating how irregular precipitation cycles contribute to fuel accumulation and prolonged drought stress, ultimately elevating wildfire risks.

Figure 7.

Altitude Map of Ambato (x1000 metres).

Figure 7.

Altitude Map of Ambato (x1000 metres).

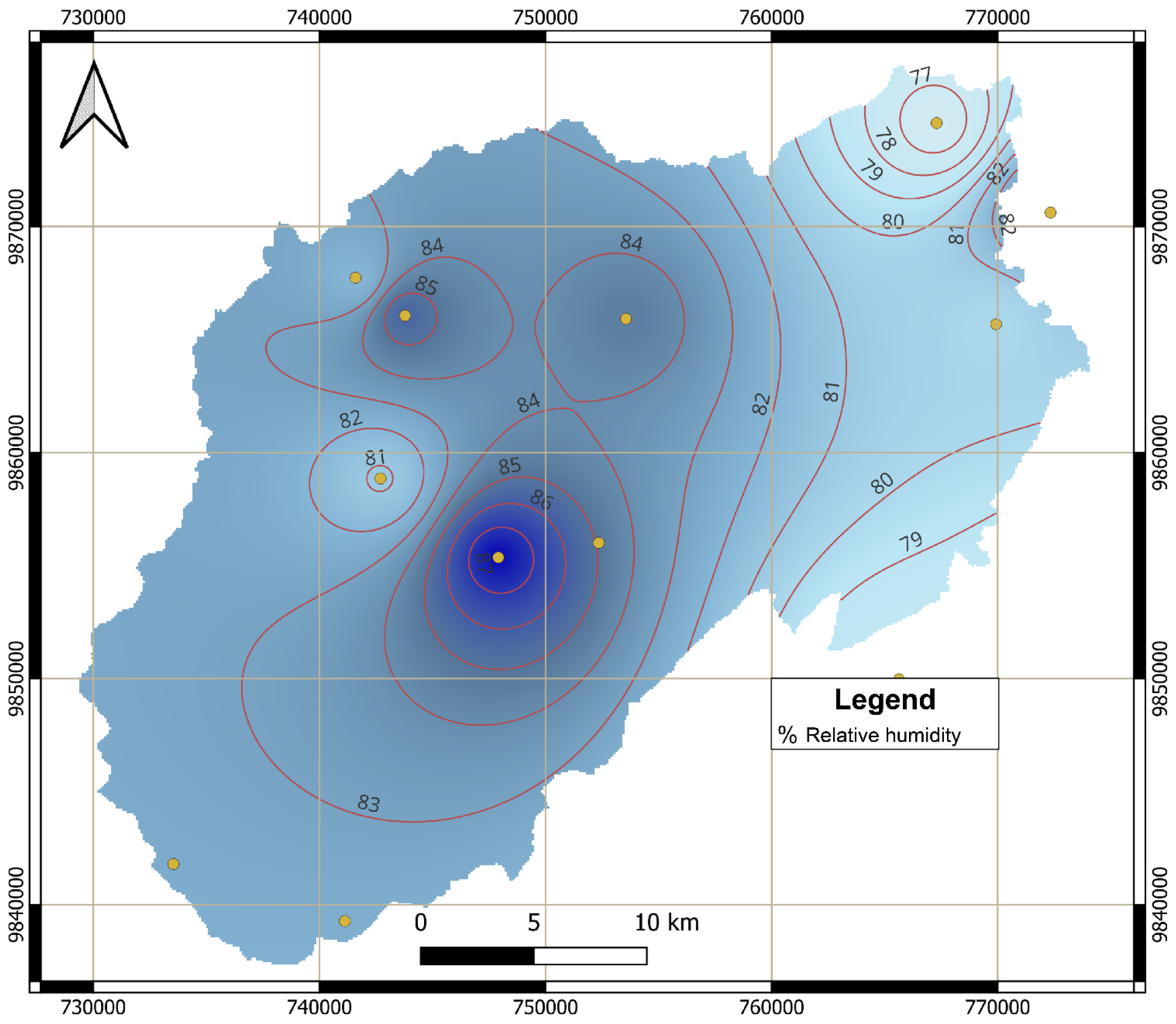

Relative humidity further influences wildfire behaviour by affecting the rate of fuel ignition and combustion. Areas exhibiting consistently low humidity levels, as depicted in

Figure 10, correspond with zones of heightened vegetation flammability, particularly within the wildland-urban interface (WUI), where human activities increase ignition potential. Steep terrains with slopes exceeding 25° present additional challenges, as seasonal winds accelerate fire spread by preheating upslope fuels. These winds, combined with drought-driven vegetation stress, create volatile conditions that complicate fire suppression efforts. The integration of climatic and spatial data enables the identification of priority intervention zones where targeted mitigation strategies—such as controlled clearing of flammable vegetation and the restoration of drought-resistant native species—can enhance ecological resilience and inform broader wildfire management frameworks, particularly for climate-sensitive mountainous regions like the Andes [

17,

18,

21,

22].

3.3. Human Factors

Wildfire frequency in Ambato exhibits strong correlations with population density and high-risk human activities. The wildland-urban interface (WUI), particularly informal settlements, experiences elevated fire incidence due to waste burning, agricultural land-clearing fires, and the unregulated use of fire for land management. Spatial analysis reveals that ignition hotspots are concentrated in densely populated areas, where flammable materials such as agricultural debris and household waste accumulate near residential zones.

Figure 11 illustrates the population density distribution, highlighting the spatial overlaps between high-density settlements and frequent ignition points.

These communities, often lacking adequate fire suppression infrastructure, are disproportionately affected during wildfire events.

Figure 11 also helps us emphasize the critical intersections between land-use practices, population density, and fire ignition sources, underscoring the urgent need for stricter regulations on open burning in the WUI. Additionally, targeted interventions such as community-led fire prevention programs, stricter land-use policies, and infrastructure improvements in informal settlements are essential to reducing human-induced wildfire risks [

7,

14,

24,

28]. Understanding these socio-environmental dynamics is crucial for developing data-driven prevention strategies, strengthening fire safety regulations, and mitigating the impact of human activities on wildfire occurrence.

3.4. Socioeconomic Vulnerabilities and Fire Risk

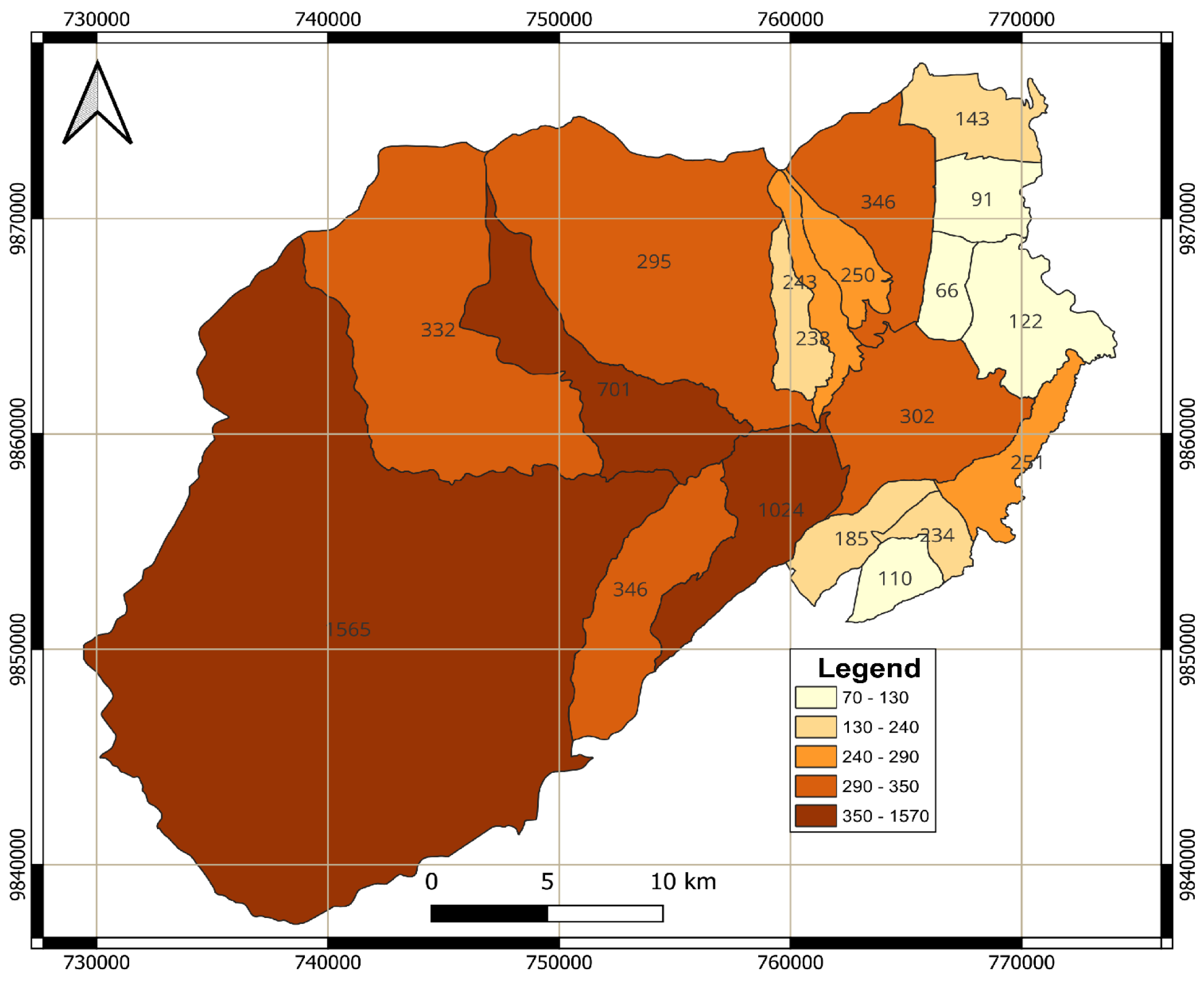

The integration of socioeconomic data with environmental and spatial datasets highlights the compounded vulnerabilities affecting Ambato’s population.

Figure 12 presents the cadastral land value distribution, illustrating economic disparities that directly influence resource allocation for wildfire prevention and mitigation. Marginalized communities in low-value cadastral zones often receive fewer resources, limiting their capacity to implement fire-resistant measures and preparedness initiatives. Additionally,

Figure 13 depicts the prevalence of household waste burning, a major ignition source in high-risk areas. The widespread use of open burning for waste disposal, particularly in lower-income neighbourhoods, exacerbates fire hazards in the wildland-urban interface (WUI) [

24,

33,

40,

41].

Public awareness also emerged as a significant challenge. Surveys reveal that residents in fire-prone areas often lack knowledge of fire safety protocols, with existing educational initiatives failing to address gaps among marginalized groups. Socioeconomic inequalities further amplify these issues, as low-income households are less likely to adopt fire-safe practices such as maintaining defensible spaces or using non-flammable building materials. These findings emphasize the necessity for targeted interventions that ensure equitable resource allocation, prioritize high-risk communities in firefighting investments, and expand multilingual outreach programs to improve fire safety awareness [

10,

12,

27]. Moreover, strengthening land-use policies to limit urban encroachment into fire-prone ecosystems is essential in mitigating fire risks, particularly in the WUI.

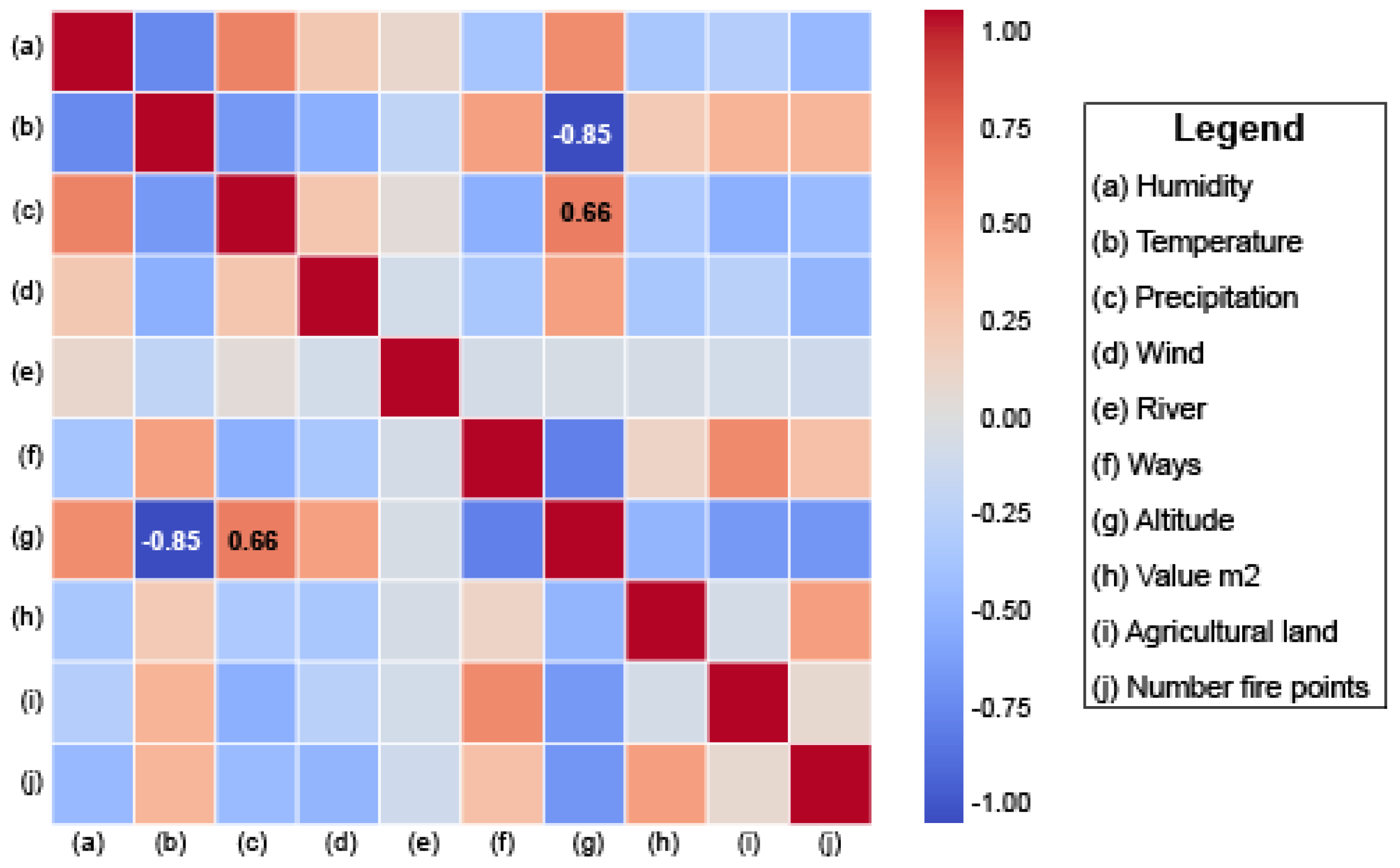

3.5. Data Correlation Analysis

The correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships between wildfire occurrences and key environmental and socio-economic variables, offering insights into the factors influencing fire dynamics. Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients were employed to assess both linear dependencies and monotonic associations between variables.

Figure 14 presents a Pearson correlation heatmap, visually illustrating the strength and direction of these relationships. In this representation, values approaching 1 indicate a strong positive correlation, while values near -1 suggest a strong inverse relationship.

The analysis reveals that land value per square meter (0.51) correlates positively with wildfire frequency, suggesting that areas with higher land costs, likely due to greater urbanisation and human activity, experience more fire incidents. Mean altitude (-0.52) exhibits a negative correlation with wildfire occurrence, indicating that fires are less frequent at higher elevations, possibly due to differences in vegetation type and climatic conditions. Additional significant correlations include mean temperature (0.40), proximity to roads (0.33), and mean humidity (-0.33), underscoring their impact on wildfire risk. These findings highlight the complex interplay between socio-economic and environmental factors in shaping wildfire behaviour in Ambato.

Figure 11.

Population Density in Ambato.

Figure 11.

Population Density in Ambato.

Figure 12.

Cadastral Land Value per Square Meter in Ambato ($ per sqm).

Figure 12.

Cadastral Land Value per Square Meter in Ambato ($ per sqm).

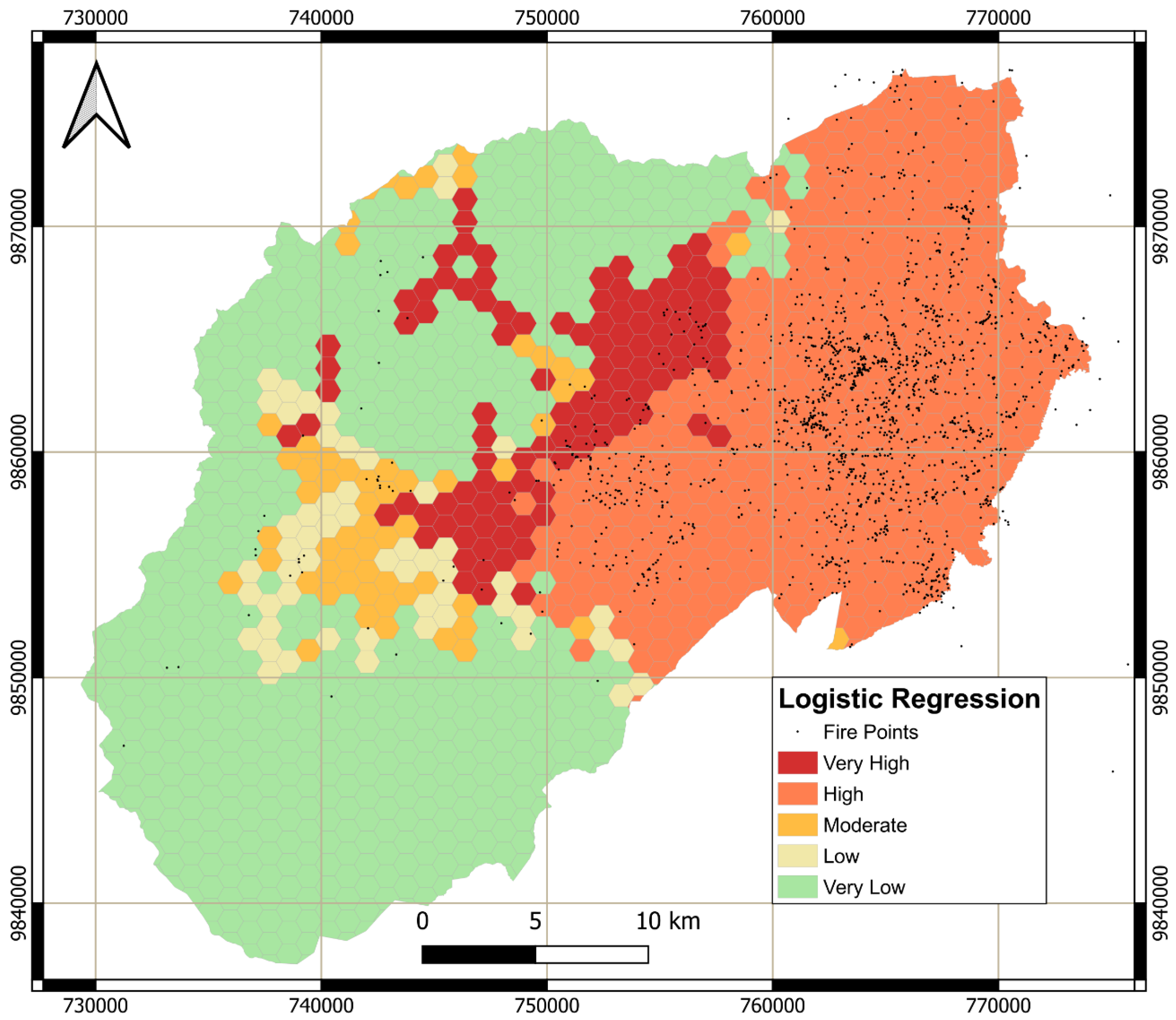

3.6. Model Predictions

3.6.1. Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR)

The predictive modelling using Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR) provided a probabilistic classification of wildfire risk across the study area. The model achieved an accuracy of 76.04%, demonstrating its reliability in predicting “Moderate,” “High,” and “Very High” risk areas. The regression coefficients revealed significant predictors, including temperature anomalies, which were positively correlated with higher risk levels, and altitude, which was negatively associated with “Very High” risk areas. Simulated scenarios under variable climatic conditions highlighted that increased wind speeds and reduced precipitation significantly shifted risk distribution toward higher categories. These predictive insights enable the identification of priority areas for immediate intervention and long-term planning [

32,

43,

45,

48,

52,

53]. According to the model, fire spreads rapidly through grasslands and shrublands under severe drought and strong wind conditions, making containment extremely difficult. The surrounding geography of Ambato, with steep slopes, exacerbates fire dynamics by facilitating rapid uphill spread and increasing the fire’s area of influence. Conversely, scenarios with moderate wind speeds and higher vegetation moisture levels show reduced fire spread, emphasizing the importance of proactive fuel management techniques, such as controlled burns, to mitigate risks.

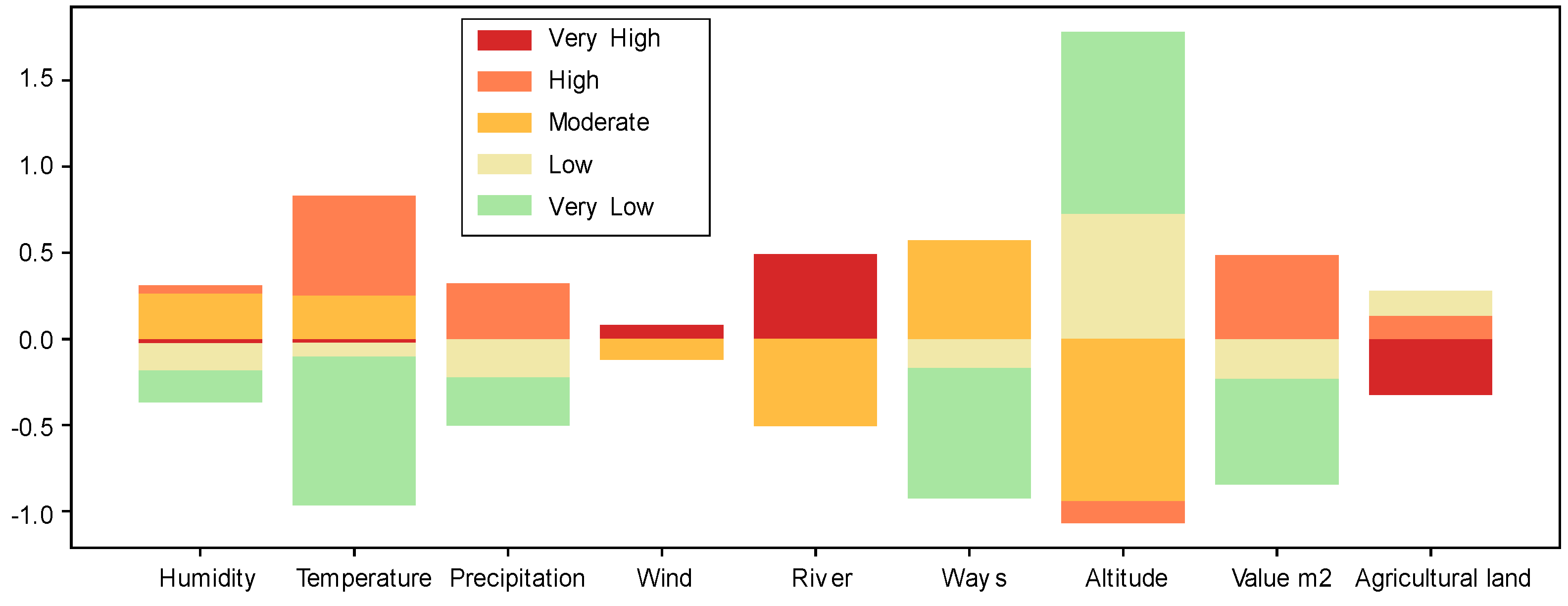

The MLR model allowed for a detailed analysis of each variable’s influence on wildfire risk classification.

Figure 15 depicts the regression coefficients, demonstrating how different environmental and socio-economic factors contribute to the probability of wildfire occurrence. Notably, the “Very High” risk category exhibits a direct relationship with altitude, reinforcing the role of topography in wildfire susceptibility. Following the application of the Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR) algorithm, a wildfire risk map was generated, as shown in

Figure 16. The results indicate that areas with a “High” probability of wildfire are primarily located in the urban zone, characterized by lower altitude, situated on the right side of the map. In contrast, zones classified as “Very High” risk are concentrated along the main inter-parish connection road between Pasa and San Fernando, suggesting higher exposure to wildfire hazards in this strategic area. Additionally, the highest-altitude zones of Ambato exhibit a “Very Low” wildfire risk, highlighting the role of altitude and climatic factors in reducing fire susceptibility.

Figure 13.

Household Waste Burning in Ambato.

Figure 13.

Household Waste Burning in Ambato.

Figure 14.

Correlation Heatmap of Environmental and Socioeconomic Factors Influencing Wildfire Occurrence in Ambato.

Figure 14.

Correlation Heatmap of Environmental and Socioeconomic Factors Influencing Wildfire Occurrence in Ambato.

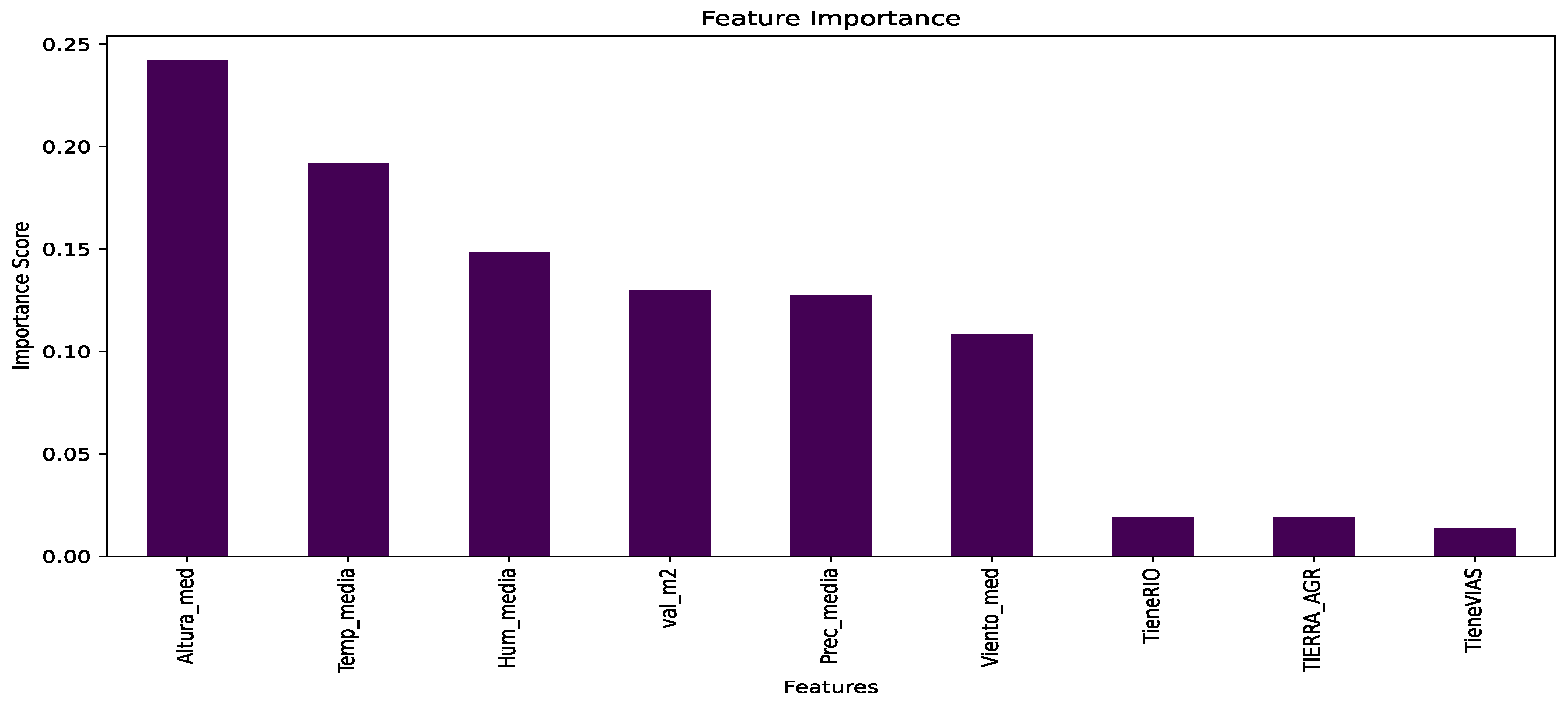

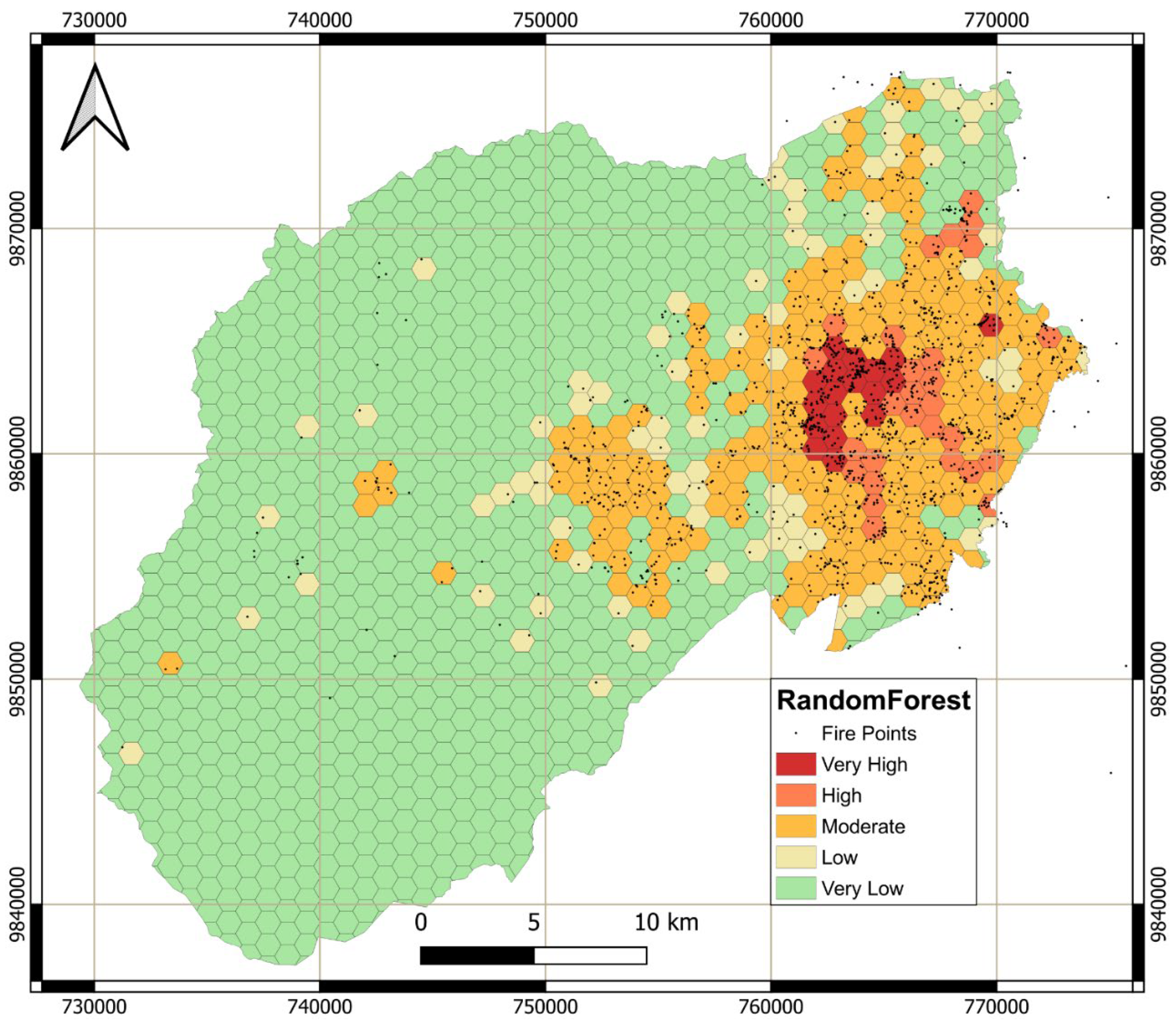

3.6.2. Random Forest

The Random Forest model was applied to assess the significance of various environmental and socio-economic variables in wildfire prediction. As illustrated in

Figure 17, mean altitude and mean temperature emerged as the most influential factors, reinforcing the role of topography and climatic conditions in fire risk dynamics. The model achieved an accuracy of 0.776, enabling the generation of a detailed wildfire risk map for Ambato. The spatial distribution of wildfire susceptibility, shown in

Figure 18, highlights that “Very Low” risk areas are predominantly located in high-altitude páramo ecosystems with sparse vegetation and minimal human activity. Meanwhile, “Low” to “Moderate” risk zones extend toward the urban periphery, correlating with transitional land-use areas. The highest risk levels, classified as “Very High,” are concentrated in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), where urban expansion, increased population density, and rising temperatures significantly amplify wildfire hazards.

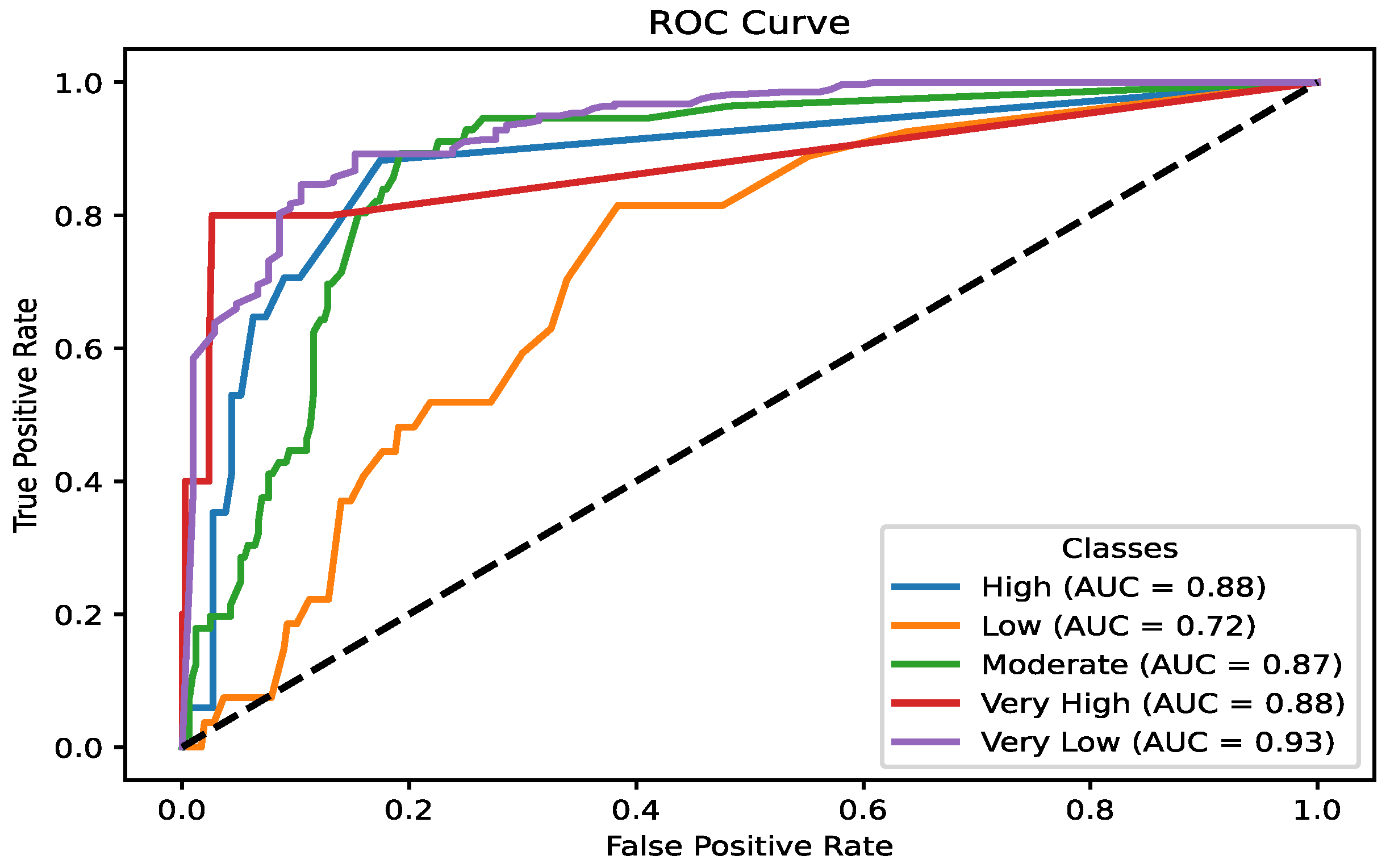

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, presented in

Figure 19, was conducted to evaluate the classification performance of the Random Forest model across different wildfire risk levels (Very Low, Low, Moderate, High, and Very High). The Area Under the Curve (AUC) values indicate strong classification capability, with all categories achieving an AUC score above 0.7. The best-performing classes include Very Low (0.93), High (0.88), and Very High (0.88), demonstrating the model’s accuracy in distinguishing these risk levels. Conversely, the “Low” risk class had the lowest AUC value (0.72), suggesting a degree of misclassification and potential confusion with adjacent risk categories. Refining the model—through improved feature selection, resampling techniques, or hyperparameter tuning—could enhance the distinction between risk classes and further improve overall predictive performance [

50,

51,

53,

54].

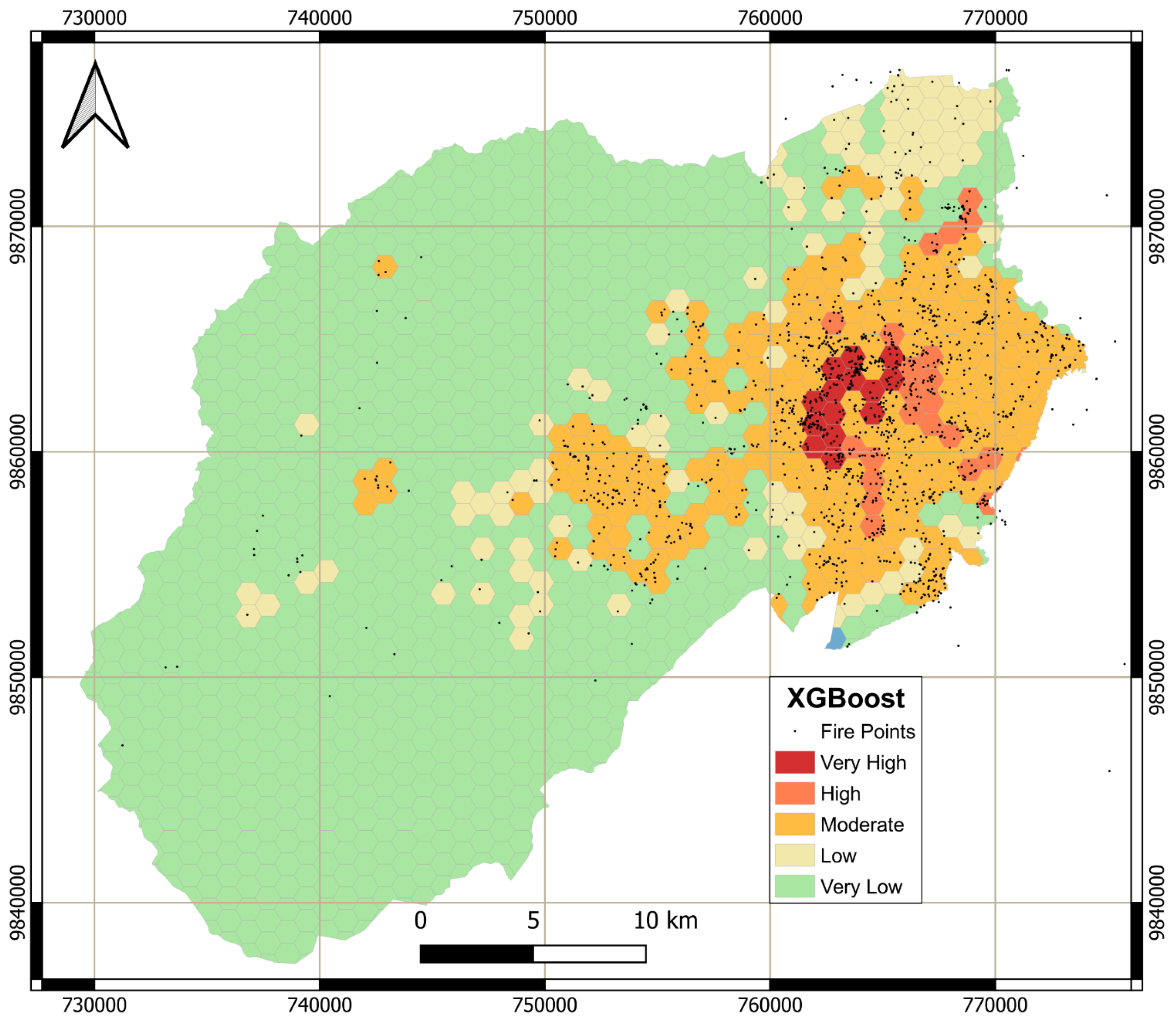

3.6.3. XGBoost

The XGBoost model achieved an accuracy of 0.765, demonstrating strong capabilities in wildfire risk classification. The generated risk distribution closely aligns with the results obtained from the Random Forest model. “Very Low” risk areas dominate most of Ambato’s landscape, particularly in high-altitude regions with sparse vegetation and minimal human influence. Conversely, “Very High” risk zones are concentrated near the city center, where urban expansion and proximity to combustible materials significantly increase wildfire vulnerability.

Figure 20 presents the wildfire risk map generated using the XGBoost model, highlighting critical areas requiring targeted mitigation strategies.

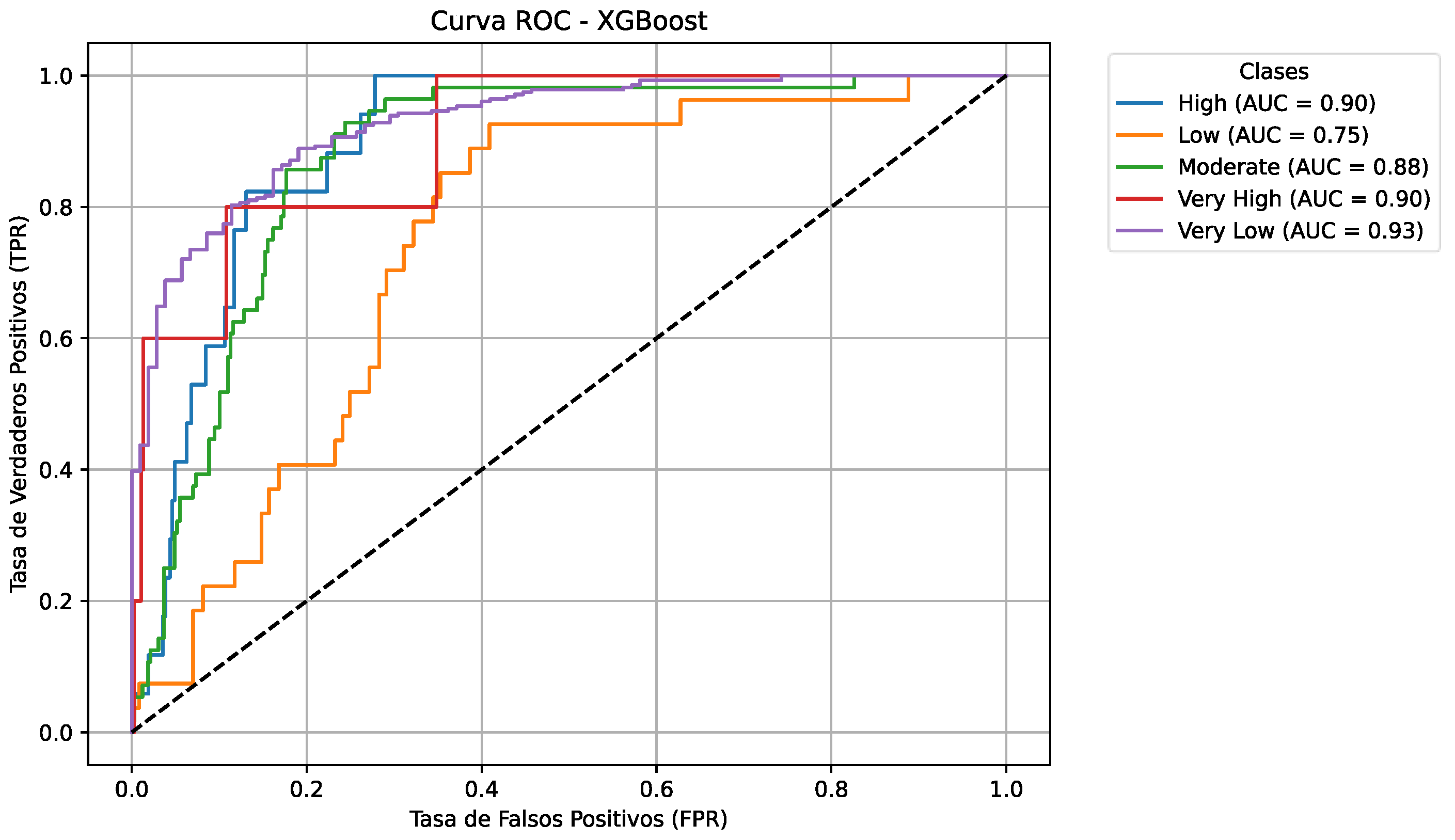

The ROC curve analysis further evaluates the performance of the XGBoost model across different wildfire risk categories. The results indicate that “Very Low,” “High,” and “Very High” risk classes exhibit strong discrimination capabilities, with AUC values above 0.85. The “Moderate” category achieves an AUC of 0.88, demonstrating acceptable predictive performance. However, the “Low” category records the lowest precision (AUC = 0.75), suggesting greater difficulty in distinguishing low-risk wildfire occurrences from other classes.

Figure 21 illustrates the ROC curve analysis, highlighting areas for potential model refinement. To improve classification accuracy, adjustments in feature selection and classification thresholds are recommended, particularly for enhancing the differentiation of low-risk wildfire zones and reducing misclassification errors [

43,

48,

50,

53,

54].

Figure 17.

Variable Importance in the Random Forest Wildfire Prediction Model.

Figure 17.

Variable Importance in the Random Forest Wildfire Prediction Model.

Figure 18.

Wildfire Risk Map of Ambato Based on Random Forest Classification.

Figure 18.

Wildfire Risk Map of Ambato Based on Random Forest Classification.

Figure 19.

ROC Curve Analysis for the Random Forest Model.

Figure 19.

ROC Curve Analysis for the Random Forest Model.

4. Discussion

The results illustrate the complex interplay between climatic, ecological, and human factors that drive wildfire risk in Ambato. It was demonstrated that climatic variables, such as temperature anomalies, prolonged droughts, and wind dynamics, exacerbate fuel desiccation and ignition susceptibility, while ecological factors, such as vegetation cover and altitude, further influence fire behaviour. Human activities, including waste burning and urban expansion, amplify these risks by introducing ignition sources into high-risk areas. The segmentation of the city into 1 km² polygons provides granular information, allowing for the identification of micro-scale risk patterns that align with other similar studies [

6,

25,

55].

Figure 20.

Wildfire Risk Map of Ambato Based on XGBoost Classification.

Figure 20.

Wildfire Risk Map of Ambato Based on XGBoost Classification.

Figure 21.

ROC Curve Analysis for the XGBoost Model.

Figure 21.

ROC Curve Analysis for the XGBoost Model.

The practical implications of this study highlight the need for targeted interventions at both local and regional levels. Moreover, thematic maps provide practical information for urban planning, particularly in regulating land use to prevent urban expansion into fire-prone zones. The integration of socioeconomic variables into risk assessments further underscores the importance of community-based strategies, such as public awareness campaigns and training programs, to mitigate anthropogenic ignition sources. These findings align with international best practices and demonstrate the value of combining data-driven approaches with local knowledge to effectively address wildfire risks [

6,

56,

57].

The findings from Ambato contribute to broader discussions on wildfire management in climate-vulnerable regions. The study employs a multi-layered methodology that integrates ecological, socioeconomic, and climatic assessments, offering a reproducible framework adaptable to other regions facing similar hazards. This research highlights the need for proactive, data-driven interventions by identifying the interconnected vulnerabilities of high-altitude ecosystems and urban-wildland interfaces. The findings indicate the benefits of integrating local strategies, such as community-based fire management and reforestation efforts, with international best practices, including controlled burns and predictive modelling [

5,

6,

11,

58].

The integration of thematic maps, predictive models, and socioeconomic data provides a solid framework for policy development. For example, land-use regulations based on spatial risk assessments can limit urban expansion into high-risk areas, reducing the exposure of vulnerable populations. Community education and engagement strategies must complement these policies, fostering a culture of fire prevention and preparedness. The segmentation approach used in this study offers a scalable methodology that can be adapted to other Andean regions, supporting broader initiatives in wildfire management and climate resilience. The use of machine learning in this context further enhances the predictive capacity of risk models, providing policymakers with a dynamic tool to prioritize interventions and optimize resource allocation [

5,

6,

11,

17,

18,

58].

Three classification models were used in this research: Multinomial Logistic Regression (MLR), Random Forest, and XGBoost. MLR relies on the linear relationship between variables to determine the probability of belonging to a specific category, leveraging global patterns in the data. Random Forest and XGBoost employ decision trees that iteratively divide the dataset based on the most relevant features, optimizing predictions by combining multiple trees and reducing overfitting. These approaches have been widely used in previous studies due to their ability to model complex relationships and enhance classification accuracy [

41,

43,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

53,

54].

The maps generated by these models show significant differences in the spatial distribution of wildfire risk. The MLR model indicates a higher prevalence of “High” risk areas on the right side of the map, with “Very Low” risk areas concentrated on the left. It identifies Ambatillo, Pasa, and San Fernando parishes as the highest-risk zones. Conversely, Random Forest and XGBoost classify “Very High” risk areas primarily in urban zones, where wildfires occur frequently but have lower spread potential. These models assign “Very Low” risk to most of the territory, reflecting a wider distribution of low-risk zones.

Authorities responsible for territorial management must select the most suitable model based on their specific needs. The MLR-based map is particularly useful for analysing fire frequency in specific areas, as it provides a direct estimate of fire probability per polygon. Meanwhile, the Random Forest and XGBoost models may be more appropriate for strategic decision-making, offering a more detailed and conservative risk assessment that is crucial for policy formulation. Since all three models exhibit similar accuracy scores—76.04% (MLR), 77.6% (Random Forest), and 76.5% (XGBoost)—the choice of model should align with the specific objectives of wildfire risk assessment and mitigation strategies [

13,

25,

26,

27,

59,

60,

61].

4.1. Mitigation Strategies and Policy Recommendations

Investments in firefighting resources, including modern fire trucks, protective equipment, and strategically placed water reservoirs, are essential for improving emergency response capacity in rural and high-risk areas. Enhancing fire station networks in underserved regions would significantly reduce response times. Additionally, establishing a centralized command centre equipped with GIS tools and simulation software would improve strategic planning and resource allocation for wildfire management [

5,

8,

29,

62,

63,

64,

65].

In addition, cooperation between national agencies and neighbouring municipalities can strengthen wildfire mitigation efforts. Shared resources, such as predictive modelling platforms and satellite monitoring systems, enhance data accuracy and provide a broader perspective on fire threats. Establishing regional training programs for emergency response teams and firefighters ensures uniform preparedness standards. Moreover, promoting ecological and economic sustainability through land management policies, such as buffer zone development and agroforestry initiatives, can further reduce wildfire risk [

45,

66,

67].

The findings emphasize the necessity of stringent land-use regulations to mitigate wildfire risks in Ambato. Enhanced zoning policies should limit urban expansion into high-risk peripheral zones where combustible vegetation poses significant threats to residential areas. Key regulatory measures include the establishment of fire-resistant buffer zones and firebreaks between natural landscapes and urban developments, as well as strict agricultural restrictions that prohibit slash-and-burn practices near urban peripheries. Rigorous enforcement mechanisms should be implemented to ensure compliance, particularly in informal settlements experiencing rapid and unregulated growth [

13,

17,

19,

25,

26,

59,

60,

61]. The proposed mitigation strategies are summarized in

Table 3, outlining key interventions in infrastructure, policy enforcement, community engagement, and resource allocation.

Public awareness campaigns must prioritize culturally accessible and demographically inclusive programs to reduce fire risks. These initiatives should focus on educating high-risk communities about safe waste disposal and fire prevention measures, integrating fire safety education into school curricula, and training local community leaders through workshops to foster shared responsibility in wildfire management.

Strengthening emergency response capabilities requires structured training programs, including controlled burns, evacuation drills, and specialized equipment handling for both firefighters and volunteers. The development of community fire brigades, supported by government initiatives, can help address infrastructure gaps in rural and underserved areas. Additionally, incorporating traditional land management practices into modern fire mitigation strategies ensures cultural relevance and enhances local engagement in wildfire risk reduction [

17,

18,

19].

A holistic strategy combining regulatory, educational, and capacity-building initiatives is essential for sustainable wildfire management. Local governments must collaborate with national and international agencies to develop frameworks that address both immediate threats and long-term resilience. Prioritizing ecosystem restoration and community participation establishes a sustainable model for wildfire management in the Andes. Furthermore, strengthening intersectoral collaboration ensures that wildfire mitigation strategies are scalable and adaptable, addressing both local vulnerabilities and regional challenges [

17,

18,

19].

4.2. Study Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the robustness of the analytical framework, certain limitations were identified throughout the study. Data constraints, such as temporal and spatial inconsistencies in historical wildfire and climate records, restricted the ability to conduct high-resolution dynamic analyses at the local scale. Additionally, outdated vegetation maps may fail to capture recent land-use changes driven by urban expansion or agricultural activities, potentially affecting the accuracy of fuel load assessments.

Methodologically, the accuracy of GIS-based spatial analyses and machine learning models heavily depends on the quality of input data and computational resources. While these models provide valuable predictive insights, they may not fully account for real-world complexities, such as abrupt climatic shifts or unpredictable human behaviours. Furthermore, socioeconomic data obtained from surveys and local reports may introduce bias, as self-reported information can underrepresent the true vulnerabilities of certain communities.

To address these challenges, future research should integrate high-resolution, real-time satellite and ground sensor data to improve spatial and temporal accuracy in wildfire risk assessments. Longitudinal studies should be conducted to evaluate the long-term efficacy of mitigation strategies, particularly in high-risk zones. Additionally, expanding the range of socioeconomic indicators—such as household resilience capacity, access to emergency resources, and social adaptation strategies—will help reduce biases and enhance the understanding of human factors influencing wildfire susceptibility.

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the intricate interplay of climatic, ecological, and human factors exacerbating wildfire risks in Ambato. By segmenting the canton into 1 km² grid cells, micro-scale risk variations were identified, emphasizing the critical role of localized drivers. Key findings reveal that prolonged droughts, elevated temperatures, and wind dynamics significantly increase vegetation desiccation and ignition susceptibility. Additionally, roads and unregulated land-use changes amplify risks, particularly in urbanizing peripheries where the wildland-urban interface (WUI) is expanding. The integration of thematic maps, predictive models, and socio-economic data provides a robust framework for pinpointing high-risk zones and designing targeted interventions. These insights enhance the understanding of wildfire dynamics in the Andean context while offering scalable solutions for fire-prone regions globally.

This research contributes to wildfire management by integrating geospatial tools, machine learning models (Multinomial Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and XGBoost), and socio-economic assessments. The classification of risk into actionable tiers (Very Low to Very High) enables precise resource allocation and evidence-based policy-making. Thematic maps visually delineate risk hotspots, guiding land-use planning to mitigate urban encroachment into fire-prone ecosystems. The methodological approach presents a scalable template adaptable to regions facing similar socio-environmental challenges, marking a significant advancement in data-driven wildfire mitigation strategies.

Critically, this study highlights the necessity of embedding socio-economic factors—such as population density, community awareness, and cultural practices—into risk assessments. This holistic approach aligns technical recommendations with local realities, ensuring that proposed strategies are both effective and contextually appropriate. Machine learning models and simulation tools further enhance predictive accuracy, empowering policymakers to evaluate long-term intervention impacts. These contributions bridge science, policy, and practice, establishing a sustainable wildfire management model for the Andes and beyond.

Future research should expand the scope of analysis across the Andean corridor to account for diverse climatic, ecological, and socio-economic conditions. This regional approach would facilitate the identification of common vulnerabilities and coordinated, scalable strategies. Real-time monitoring through satellite imagery, ground-based sensors, and IoT networks should be prioritized to track vegetation moisture, temperature anomalies, and ignition points, enabling proactive decision-making and adaptive response protocols. Additionally, community-centred approaches must be strengthened by prioritizing local empowerment through education, training, and participatory governance, integrating traditional land management practices with scientific knowledge to ensure culturally relevant risk reduction. Finally, intersectoral collaboration should be reinforced, fostering partnerships between local governments, national agencies, and international organizations to align local needs with global best practices. Addressing these priorities will establish a comprehensive and adaptive wildfire management framework in the Andes—one that balances ecological sustainability with socio-economic resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation was performed by A.H., B.P.-B., and L-F.C.; methodology was carried out by A.H., B.P.-B., and L-F.C.; data processing was conducted by B.P.-B. and V.N.; software was developed by A.H., B.P.-B., and V.N.; validation was provided by L-F.C., and V.N.; writing—original draft preparation was revised by A.H. and B.P.-B.; writing—review and editing was prepared by B.P.-B., A.H., L-F.C., and V.N.; visualisation was analysed by A.H., B.P.-B., and V.N.; supervision was conducted by A.H. and L-F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the Universidad Técnica de Ambato for its financial support through the Research and Development Direction (DIDE) for funding this research under Project ID PFICM30: “Caracterización del comportamiento frente al fuego de materiales de construcción utilizados en obra civil”. Additionally, B.P.-B. would also like to acknowledge the Universidad Técnica de Ambato for the financial support received via its doctorate mobility programme (Award No. 1886-CU-P-2018, Resolución HCU).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Cuerpo de Bomberos de Ambato, the Gobierno Provincial de Tungurahua, and the Municipio de Ambato for providing access to critical wildfire records, meteorological data, and geospatial information that contributed to this research. Their publicly available datasets and institutional efforts in fire risk management were fundamental to the study’s development. In addition, the authors acknowledge the continuous support of the “Gestión de Recursos Naturales e Infraestructura Sustentable” (GeReNIS) research group at Universidad Técnica de Ambato.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Synolakis, C.E.; Karagiannis, G.M. Wildfire Risk Management in the Era of Climate Change. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lewis, D.J. Wildfires and Climate Change Have Lowered the Economic Value of Western U.S. Forests by Altering Risk Expectations. J Env. Econ Manag. 2024, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Schriek, T.; Varotsos, K. V.; Karali, A.; Giannakopoulos, C. Wildfire Burnt Area and Associated Greenhouse Gas Emissions under Future Climate Change Scenarios in the Mediterranean: Developing a Robust Estimation Approach. Fire 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, J.A.; Clark, J.; Boustras, G. Governing Wildfires: Toward a Systematic Analytical Framework. Ecol. Soc. 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaverde Canosa, I.; Ford, J.; Paavola, J.; Burnasheva, D. Community Risk and Resilience to Wildfires: Rethinking the Complex Human–Climate–Fire Relationship in High-Latitude Regions. Sustain. (Switz. ) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaverde Canosa, I.; Ford, J.; Paavola, J.; Burnasheva, D. Community Risk and Resilience to Wildfires: Rethinking the Complex Human–Climate–Fire Relationship in High-Latitude Regions. Sustain. (Switz. ) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiciulyte, S.; Rivero-Villar, A.; Guibrunet, L. Emerging Risks of Wildfires at the Wildland-Urban Interface in Mexico. Fire Technol 2023, 59, 983–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, J.K.; Bradley, B.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Chelsea Nagy, R.; Fusco, E.J.; Mahood, A.L. Human-Started Wildfires Expand the Fire Niche across the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 2946–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhs, J.W.; Parvania, M.; Shahidehpour, M. Wildfire Risk Mitigation: A Paradigm Shift in Power Systems Planning and Operation. IEEE Open Access J. Power Energy 2020, 7, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiewicz, A.M.; Paveglio, T.B. Preparing for Wildfire Evacuation and Alternatives: Exploring Influences on Residents’ Intended Evacuation Behaviors and Mitigations. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, N.; Mahler, P.; Beverly, J.L. Optimizing Fuel Treatments for Community Wildfire Mitigation Planning. J Env. Manag. 2024, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byerly, H.; Meldrum, J.R.; Brenkert-Smith, H.; Champ, P.; Gomez, J.; Falk, L.; Barth, C. Developing Behavioral and Evidence-Based Programs for Wildfire Risk Mitigation. Fire 2020, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misal, H.; Varela, E.; Voulgarakis, A.; Rovithakis, A.; Grillakis, M.; Kountouris, Y. Assessing Public Preferences for a Wildfire Mitigation Policy in Crete, Greece. Policy Econ 2023, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.T.; Baik, J.; Echeverri Figueroa, V.; Rini, D.; Moritz, M.A.; Roberts, D.A.; Sweeney, S.H.; Carvalho, L.M.V.; Jones, C. Developing Effective Wildfire Risk Mitigation Plans for the Wildland Urban Interface. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2023, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozumder, P.; Helton, R.; Berrens, R.P. Provision of a Wildfire Risk Map: Informing Residents in the Wildland Urban Interface. Risk Anal. 2009, 29, 1588–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Este, M.; Giannico, V.; Lafortezza, R.; Sanesi, G.; Elia, M. The Wildland-Urban Interface Map of Italy: A Nationwide Dataset for Wildfire Risk Management. Data Brief 2021, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Muñoz, P.; Cabrera-García, S.; Jácome-Aguirre, G. A Multicriteria Geographic Information System Analysis of Wildfire Susceptibility in the Andean Region: A Case Study in Ibarra, Ecuador. Fire 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Zubieta, R.; Ccanchi, Y.; Martínez, A.; Paucar, Y.; Alvarez, S.; Loayza, J.; Ayala, F. Seasonal Effects of Wildfires on the Physical and Chemical Properties of Soil in Andean Grassland Ecosystems in Cusco, Peru: Pending Challenges. Fire 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, F.; Morante-Carballo, F.; González, A.; Bravo-Montero, Lady; Benavidez-Silva, C.; Tedim, F. Assessment of Forest Fire Severity for a Management Conceptual Model: Case Study in Vilcabamba, Ecuador. Forests 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, P. Management Conflicts in the Ambato River Watershed, Tungurahua Province, Ecuador. Mt Res Dev 2002, 22, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, A.; Ferreira, J.; Escada, M.; Reis, J.; Leite, C.; Andrade, D.; Spínola, J.; Soares, M.; Anderson, L. Fire Exposure Index as a Tool for Guiding Prevention and Management. Front Phys 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira Barbosa, M.L.; Haddad, I.; da Silva Nascimento, A.L.; Máximo da Silva, G.; Moura da Veiga, R.; Hoffmann, T.B.; Rosane de Souza, A.; Dalagnol, R.; Susin Streher, A.; Souza Pereira, F.R.; et al. Compound Impact of Land Use and Extreme Climate on the 2020 Fire Record of the Brazilian Pantanal. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2022, 31, 1960–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moratalla, A.Z.; Baeriswyl, S. Metodología Para El Desarrollo Del Mapa Vulnerabilidad Urbana Frente a Incendios Forestales En La Región Del Biobío y Ñuble;

- Gonzalez, S.; Ghermandi, L. How to Define the Wildland-Urban Interface? Methods and Limitations: Towards a Unified Protocol. Front Env. Sci 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chas-Amil, M.L.; Prestemon, J.P.; McClean, C.J.; Touza, J. Human-Ignited Wildfire Patterns and Responses to Policy Shifts. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 56, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roengtam, S.; Agustiyara, A. Collaborative Governance for Forest Land Use Policy Implementation and Development. Cogent Soc Sci 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadas, M.J.; Leal, M.; Soares, F.; Novais, A.; Ribeiro, P.F.; Schmidt, L.; Delicado, A.; Moreira, F.; Bergonse, R.; Oliveira, S.; et al. Wildfire Mitigation and Adaptation: Two Locally Independent Actions Supported by Different Policy Domains. Land Use Policy 2023, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsopoulos, I.; Mallinis, G.; Arianoutsou, M. Wildfire Risk Assessment in a Typical Mediterranean Wildland–Urban Interface of Greece. Env. Manag. 2014, 55, 900–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasilla, D.F.; García-Codron, J.C.; Carracedo, V.; Diego, C. Circulation Patterns, Wildfire Risk and Wildfire Occurrence at Continental Spain. Phys. Chem. Earth 2010, 35, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Diego, J.; Fernández, M.; Rúa, A.; Kline, J.D. Examining Socioeconomic Factors Associated with Wildfire Occurrence and Burned Area in Galicia (Spain) Using Spatial and Temporal Data. Fire Ecol. 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trucchia, A.; Meschi, G.; Fiorucci, P.; Provenzale, A.; Tonini, M.; Pernice, U. Wildfire Hazard Mapping in the Eastern Mediterranean Landscape. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2023, 32, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Zúñiga-Antón, M.; Alcasena, F.; Gelabert, P.; Vega-Garcia, C. Integrating Geospatial Wildfire Models to Delineate Landscape Management Zones and Inform Decision-Making in Mediterranean Areas. Saf Sci 2022, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampekis, S.; Sakellariou, S.; Palaiologou, P.; Arabatzis, G.; Kantartzis, A.; Malesios, C.; Stergiadou, A.; Fafalis, D.; Tsiaras, E. Building Wildland–Urban Interface Zone Resilience through Performance-Based Wildfire Engineering. A Holistic Theoretical Framework. EuroMediterr J Env. Integr 2023, 8, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.; Driscoll, A.; Heft-Neal, S.; Xue, J.; Burney, J.; Wara, M. The Changing Risk and Burden of Wildfire in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, T.N.; Mueller, S.E. Climate Influences on Future Fire Severity: A Synthesis of Climate-Fire Interactions and Impacts on Fire Regimes, High-Severity Fire, and Forests in the Western United States. Fire Ecology 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Fire Protection Association How to Become a Firewise USA Site.

- Ambato Fire Department Database of Fires in Ambato. 2023.

- Honorable Gobierno Provincial de Tungurahua Red Hidrometeorológica de Tungurahua, Geoportal Available online: https://rrnn.tungurahua.gob.ec/.

- Gobierno Autónomo Descentralizado de Ambato Geoportal Servicios Virtuales Available online: https://geoambato-gadma.opendata.arcgis.com/.

- Mahamed, M.; Wittenberg, L.; Kutiel, H.; Brook, A. Fire Risk Assessment on Wildland–Urban Interface and Adjoined Urban Areas: Estimation Vegetation Ignitability by Artificial Neural Network. Fire 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, E.; Kocer, A.; Yilmaz, İ.; Akçal, A.N.; Akpinar, K. Assessing Fire Risk in Wildland–Urban Interface Regions Using a Machine Learning Method and GIS Data: The Example of Istanbul’s European Side. Fire 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, T.; Theruvil Sayed, B.; Majdi, A.; Zhou, J.; Sagban, R.; Band, S.S.; Mosavi, A. An Integrated GIS-Based Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines-Cat Swarm Optimization for Improving the Accuracy of Wildfire Susceptibility Mapping. Geocarto Int 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, D.; Ma, H.; Lin, R.; Zhang, F. Modeling Forest Fire Spread Using Machine Learning-Based Cellular Automata in a GIS Environment. Forests 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.S.; Park, S.D.; Kim, G. Applicability Comparison of GIS-Based RUSLE and SEMMA for Risk Assessment of Soil Erosion in Wildfire Watersheds. Remote Sens (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, M.R.; Cunha, N.S.; Pena, S.B.; Müller, A. FIRELAN—An Ecologically Based Planning Model towards a Fire Resilient and Sustainable Landscape. A Case Study in Center Region of Portugal. Sustain. (Switz. ) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascoli, D.; Plana, E.; Oggioni, S.D.; Tomao, A.; Colonico, M.; Corona, P.; Giannino, F.; Moreno, M.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Kaoukis, K.; et al. Fire-Smart Solutions for Sustainable Wildfire Risk Prevention: Bottom-up Initiatives Meet Top-down Policies under EU Green Deal. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Feng, Z.; Sun, L.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, B.; Chen, Y. Mapping China’s Forest Fire Risks with Machine Learning. Forests 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Wang, S.; Wu, T.; Gao, X.; Liang, T. Optimized Machine Learning Model for Fire Consequence Prediction. Fire 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghim, S.; Mehrabi, M. Wildfire Assessment Using Machine Learning Algorithms in Different Regions. Fire Ecol. 2024, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghim, S.; Mehrabi, M. Wildfire Assessment Using Machine Learning Algorithms in Different Regions. Fire Ecol. 2024, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perello, N.; Meschi, G.; Trucchia, A.; D’Andrea, M.; Baghino, F.; Esposti, S.D.; Fiorucci, P. Machine Learning-Driven Dynamic Maps Supporting Wildfire Risk Management. In Proceedings of the IFAC-PapersOnLine. Elsevier B.V., June 1 2024; Vol. 58, pp. 67–72.

- Dorph, A.; Marshall, E.; Parkins, K.A.; Penman, T.D. Modelling Ignition Probability for Human- and Lightning-Caused Wildfires in Victoria, Australia. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 3487–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, A.M.K.; Boer, M.M.; Cunningham, C.X.; Nolan, R.H.; Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Williamson, G.J. Modeling the Probability of Dry Lightning-Induced Wildfires in Tasmania: A Machine Learning Approach. Geophys Res Lett 2024, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaee, M.; Easterday, K.; Klausmeyer, K. Integrating Hydrological Parameters in Wildfire Risk Assessment: A Machine Learning Approach for Mapping Wildfire Probability. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P.; Menezes, I.C.; Miranda, A.I. A Human Behavior Wildfire Ignition Probability Index for Application to Mainland Portugal. Fire 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, A.S.R.; Ramos, R.M.; Sano, E.E.; Libonati, R.; Santos, F.L.M.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Giongo, M.; da Franca, R.R.; Laranja, R.E. de P. Implementation of Fire Policies in Brazil: An Assessment of Fire Dynamics in Brazilian Savanna. Sustain. (Switz. ) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T.; Bradshaw, S.D.; Dixon, K.W.; Zylstra, P. Wildfire Risk Management across Diverse Bioregions in a Changing Climate. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2022, 13, 2405–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erni, S.; Wang, X.; Swystun, T.; Taylor, S.W.; Parisien, M.A.; Robinne, F.N.; Eddy, B.; Oliver, J.; Armitage, B.; Flannigan, M.D. Mapping Wildfire Hazard, Vulnerability, and Risk to Canadian Communities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huidobro, G.; Giessen, L.; Burns, S.L. And It Burns, Burns, Burns, the Ring-of-Fire: Reviewing and Harmonizing Terminology on Wildfire Management and Policy. Environ Sci Policy 2024, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Huidobro, G.; Lopes, L.F.; Ganteaume, A.; Ascoli, D.; Colaco, C.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Giannaros, T.M.; Gazzard, R.; Boustras, G.; et al. A Global Outlook on Increasing Wildfire Risk: Current Policy Situation and Future Pathways. Trees For. People 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Huidobro, G.; Lopes, L.F.; Ganteaume, A.; Ascoli, D.; Colaco, C.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Giannaros, T.M.; Gazzard, R.; Boustras, G.; et al. A Global Outlook on Increasing Wildfire Risk: Current Policy Situation and Future Pathways. Trees For. People 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Park, J.; Eem, S.; Kwag, S. Methodology for Generating Wildfire Hazard Map for Safety Assessment of Off-Site Power Systems against Wildfires. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Rocha, J.; Sá, A. Wildfire Risk Modeling. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestas, J.D.; Smith, J.T.; Allred, B.W.; Naugle, D.E.; Jones, M.O.; O’Connor, C.; Boyd, C.S.; Davies, K.W.; Crist, M.R.; Olsen, A.C. Using Dynamic, Fuels-Based Fire Probability Maps to Reduce Large Wildfires in the Great Basin. Rangel Ecol Manag 2023, 89, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Guo, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, R.; Li, X. Wildfire Risks under a Changing Climate: Synthesized Assessments of Wildfire Risks over Southwestern China. Front Env. Sci 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sil, Â.; Azevedo, J.C.; Fernandes, P.M.; Honrado, J.P. Will Fire-Smart Landscape Management Buffer the Effects of Climate and Land-Use Changes on Fire Regimes? Ecol Process 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagra, P.E.; Cesca, E.; Alvarez, L.M.; Delgado, S.; Villalba, R. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Forest Fires in the Central Monte: Relationships with Regional Climate. Ecol Process 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).