Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

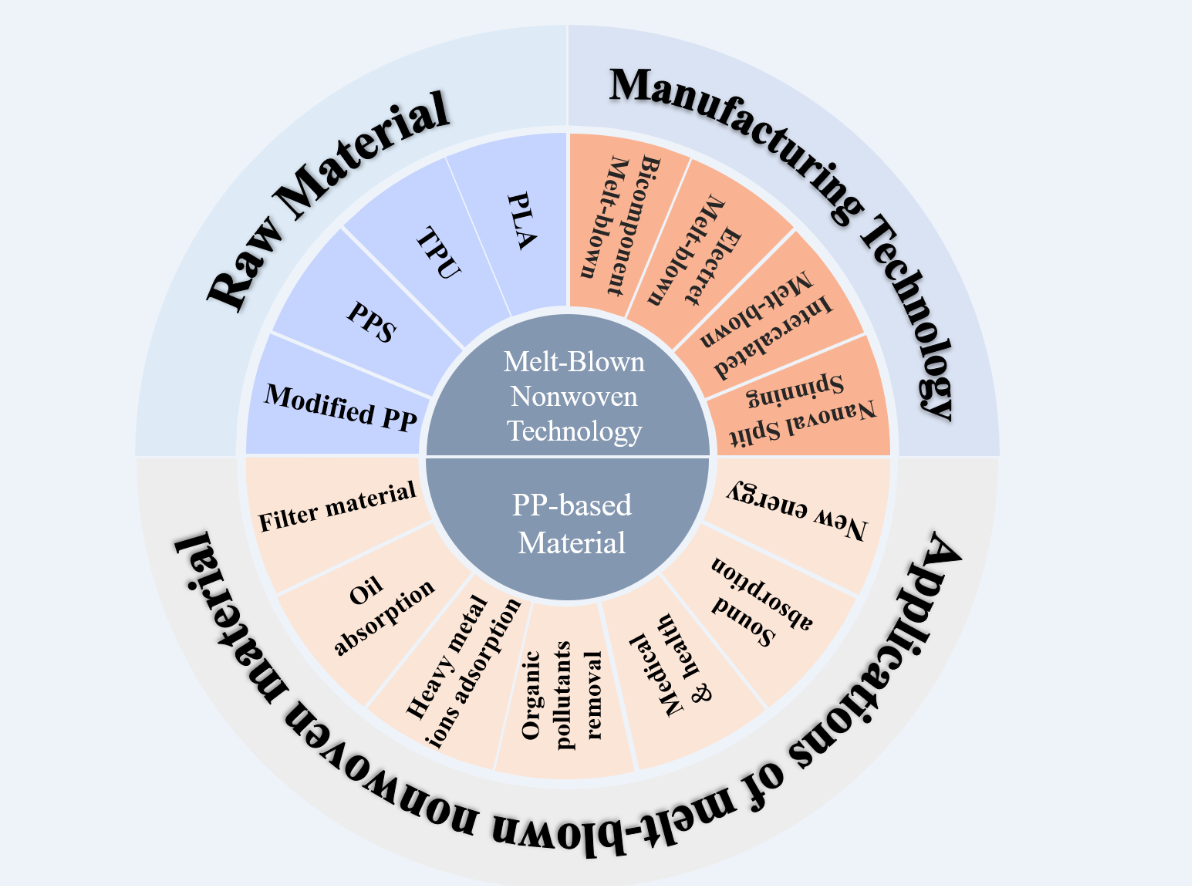

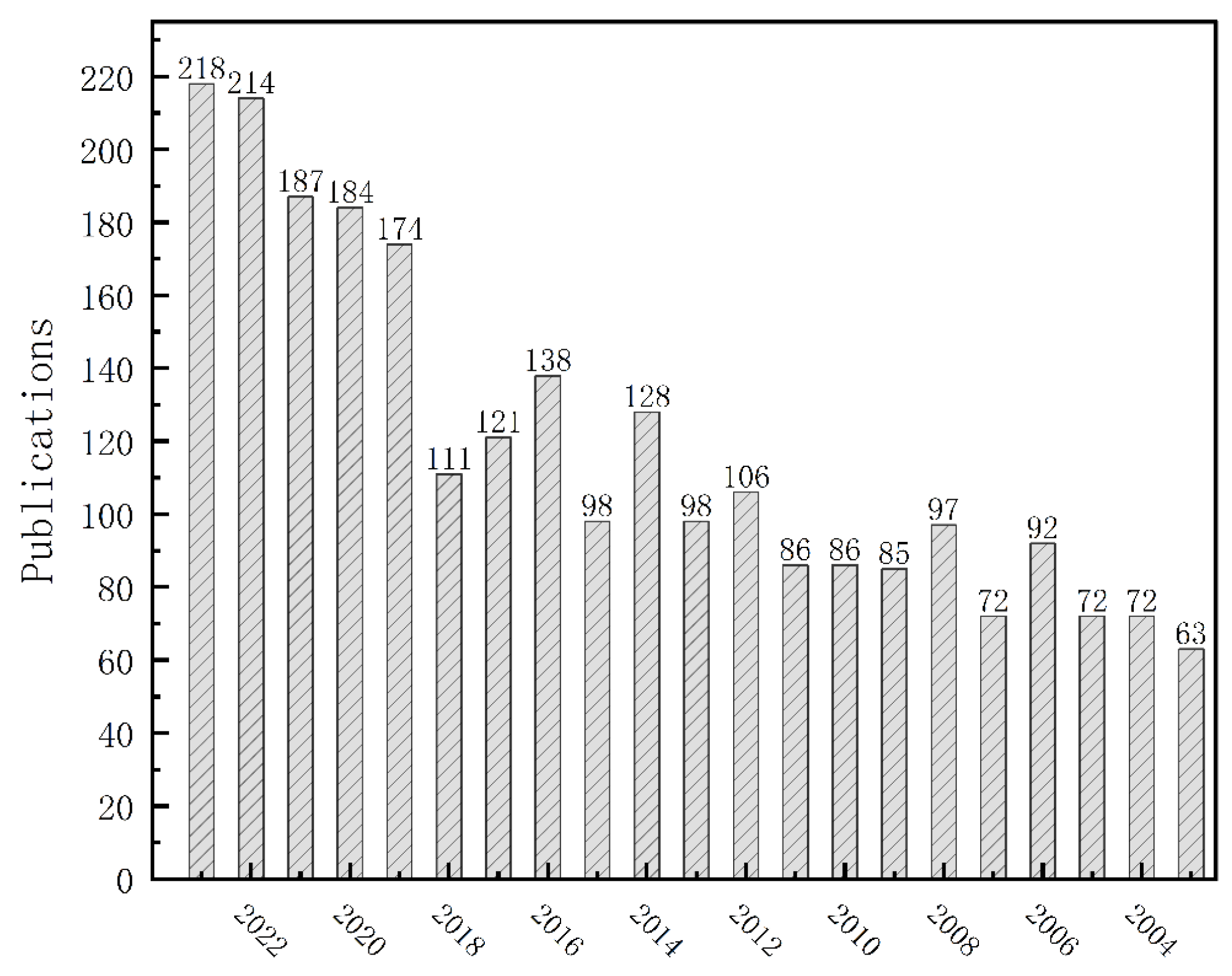

1. Introduction

2. Melt-Blown Spinning Principles and Processes Description

3. Melt-Blown Nonwoven Technology Research Progress

3.1. Development of Melt-Blown Raw Materials

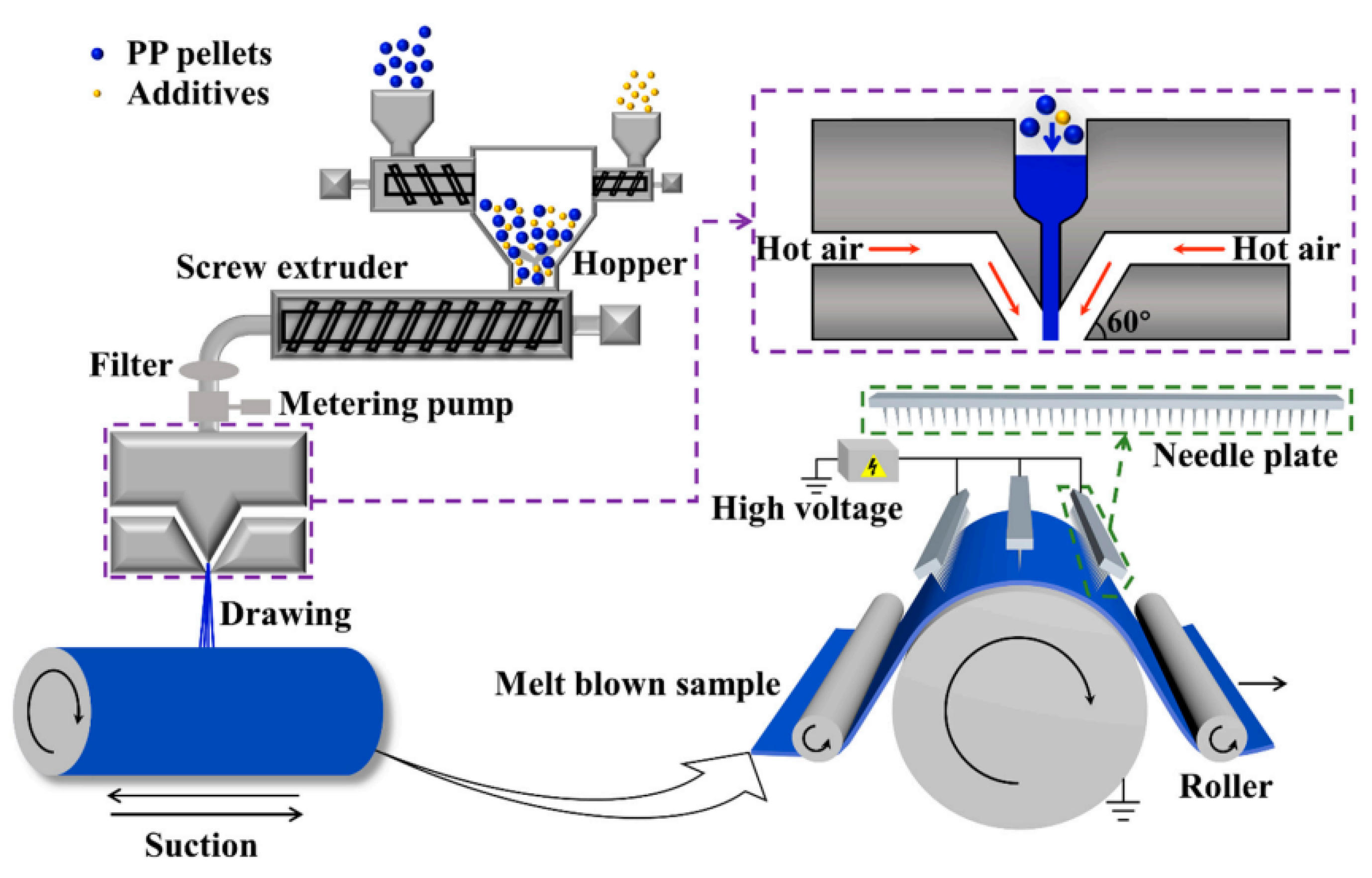

3.1.1. Modified PP

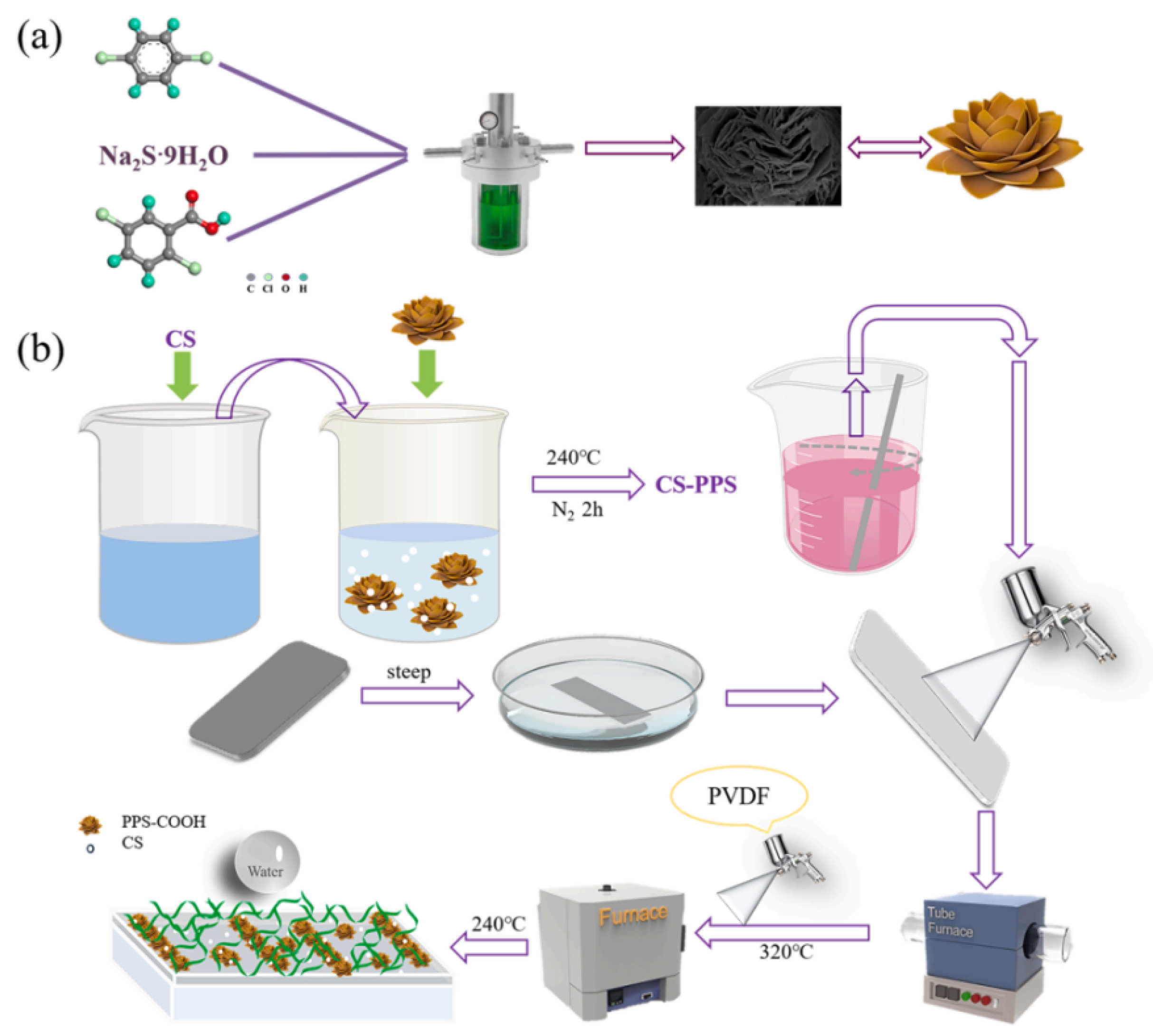

3.1.2. PPS

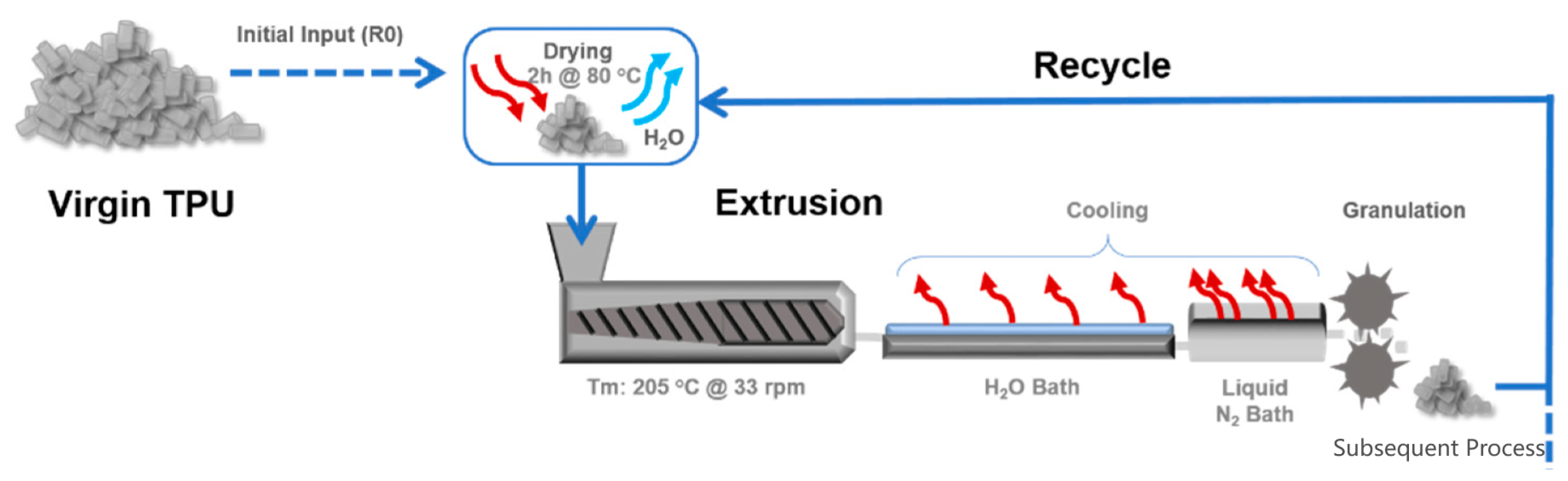

3.1.3. TPU

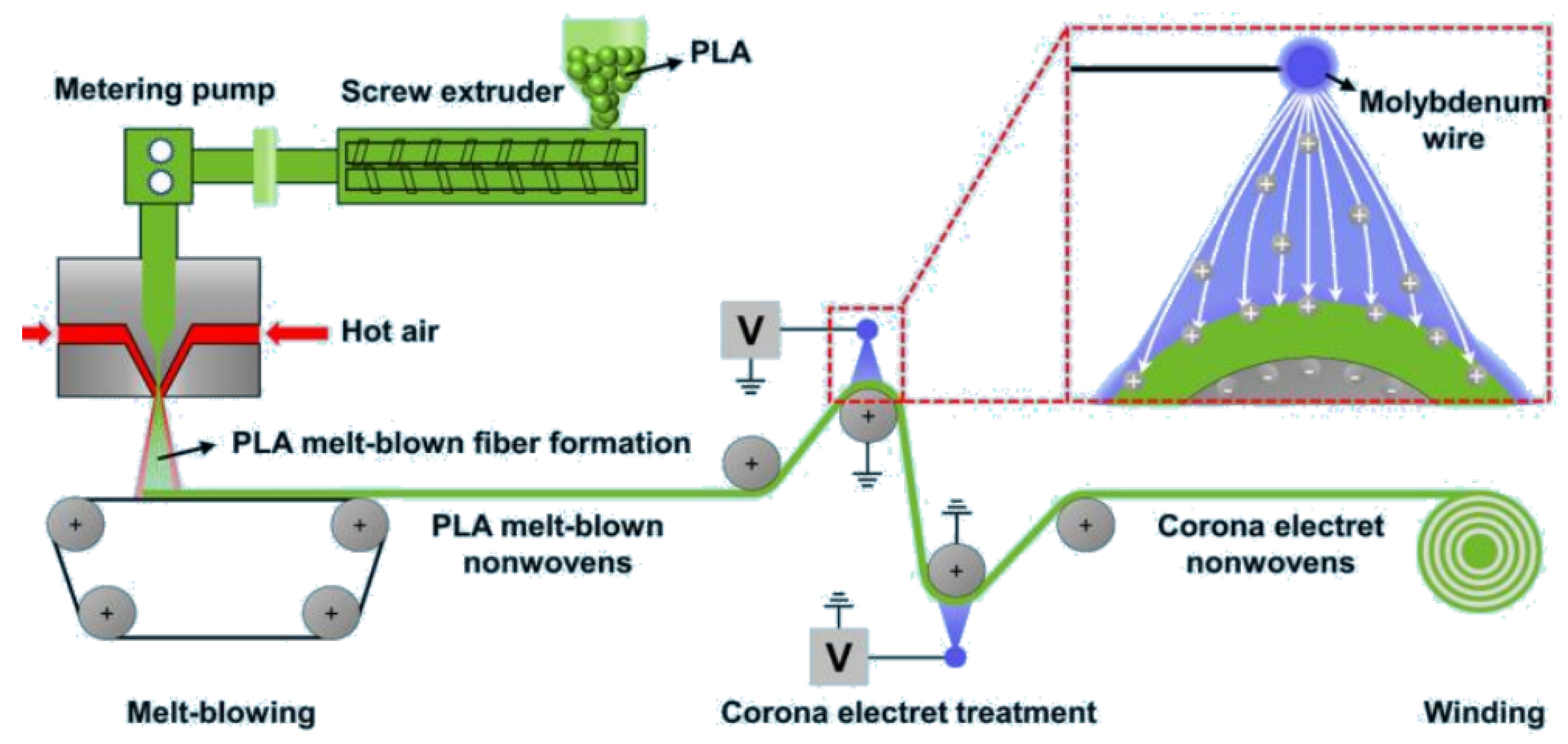

3.1.4. PLA

3.2. Development of Melt-Blown Manufacturing Technology

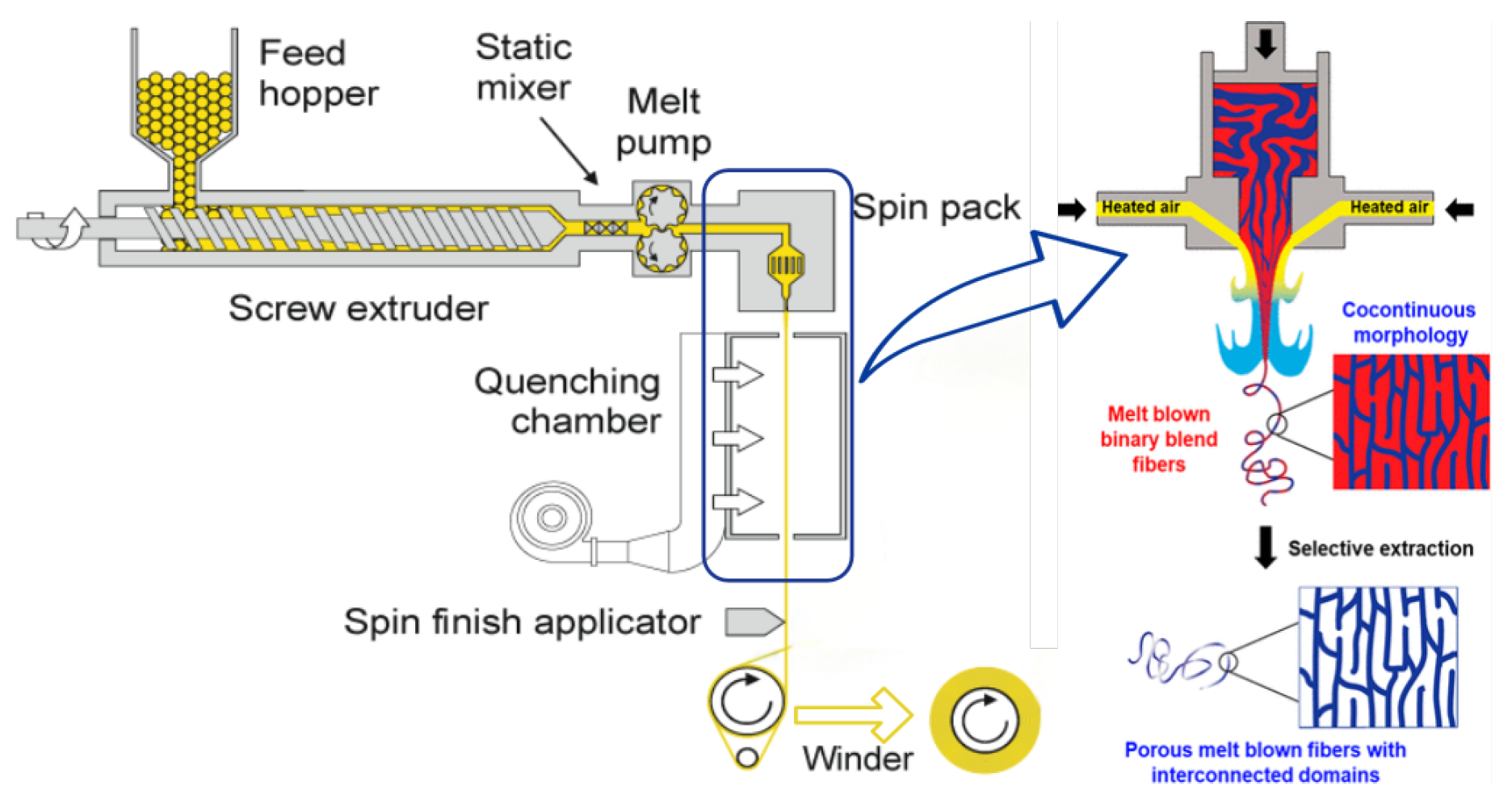

3.2.1. Bicomponent Melt-Blown Technology

3.2.2. Electret Melt-Blown Technology

3.2.3. Intercalated Melt-Blown Composite Technology

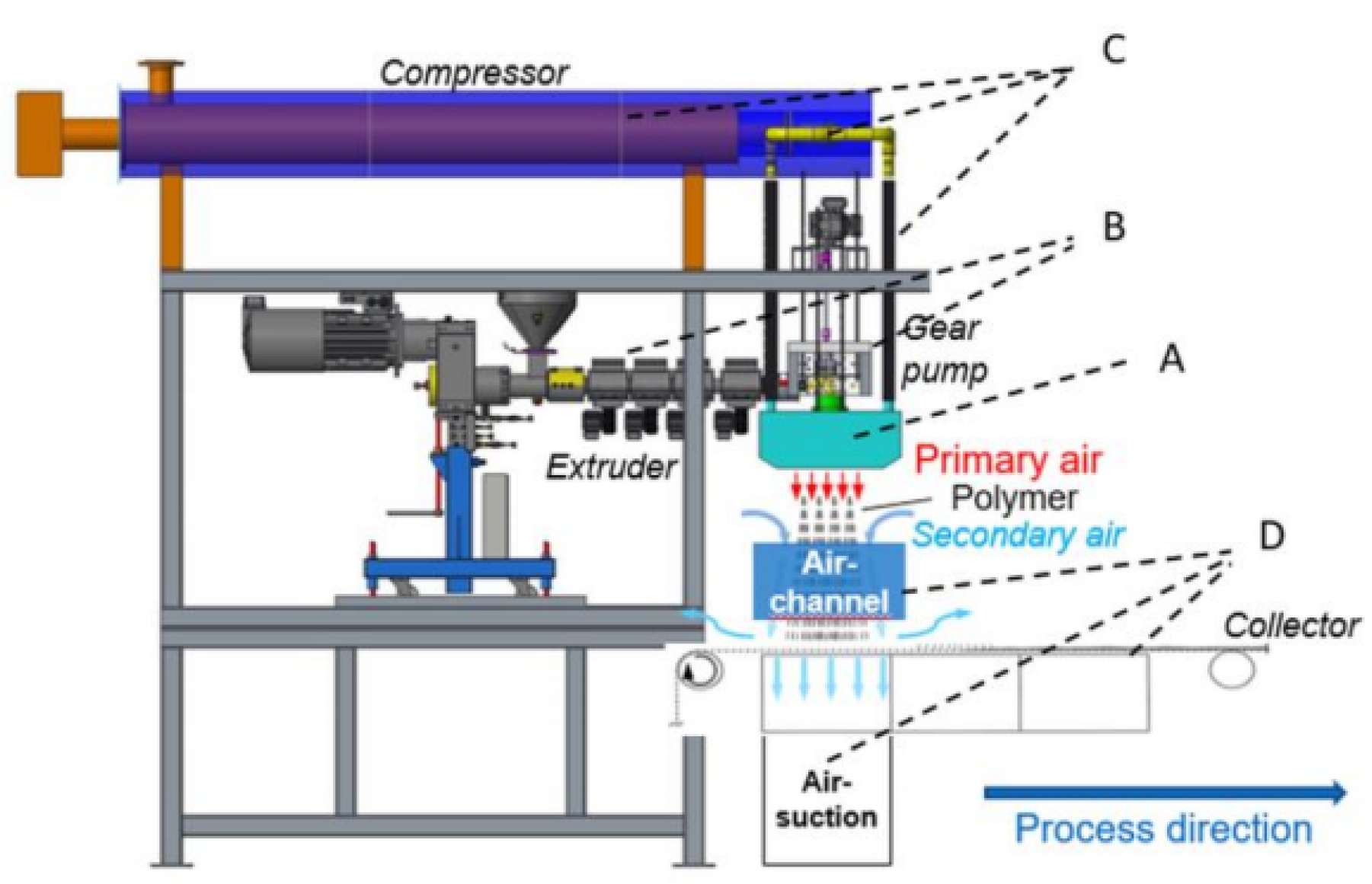

3.2.4. Nanoval Split Spinning Technology

3.3. Main Applications of PP-Based Melt-Blown Nonwoven Materials

3.3.1. Filter Materials

3.3.2. Oil Absorbent Materials

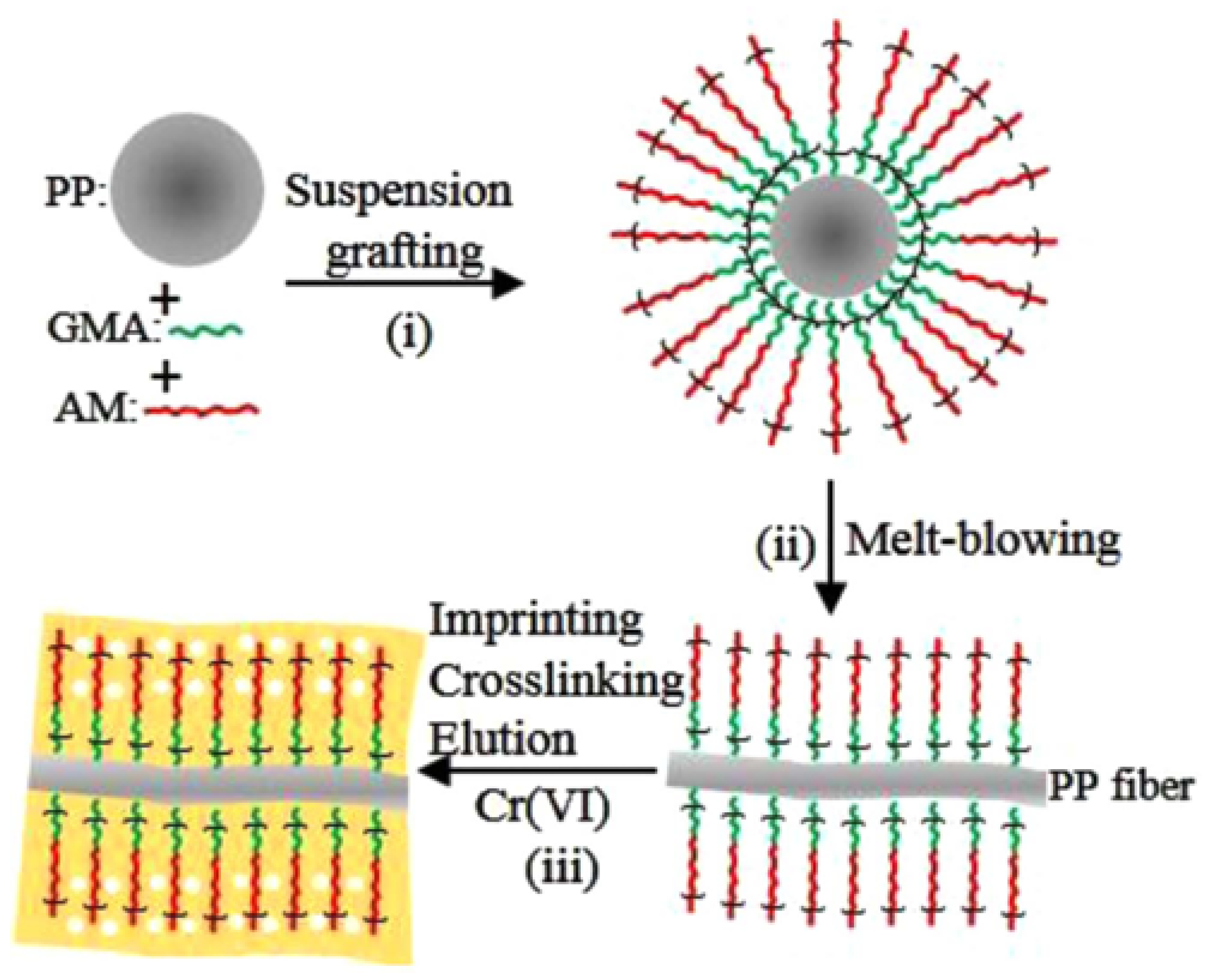

3.3.3. Heavy Metal Ions Adsorption

3.3.4. Organic Pollutant Removal

3.3.5. Medical and Health Materials

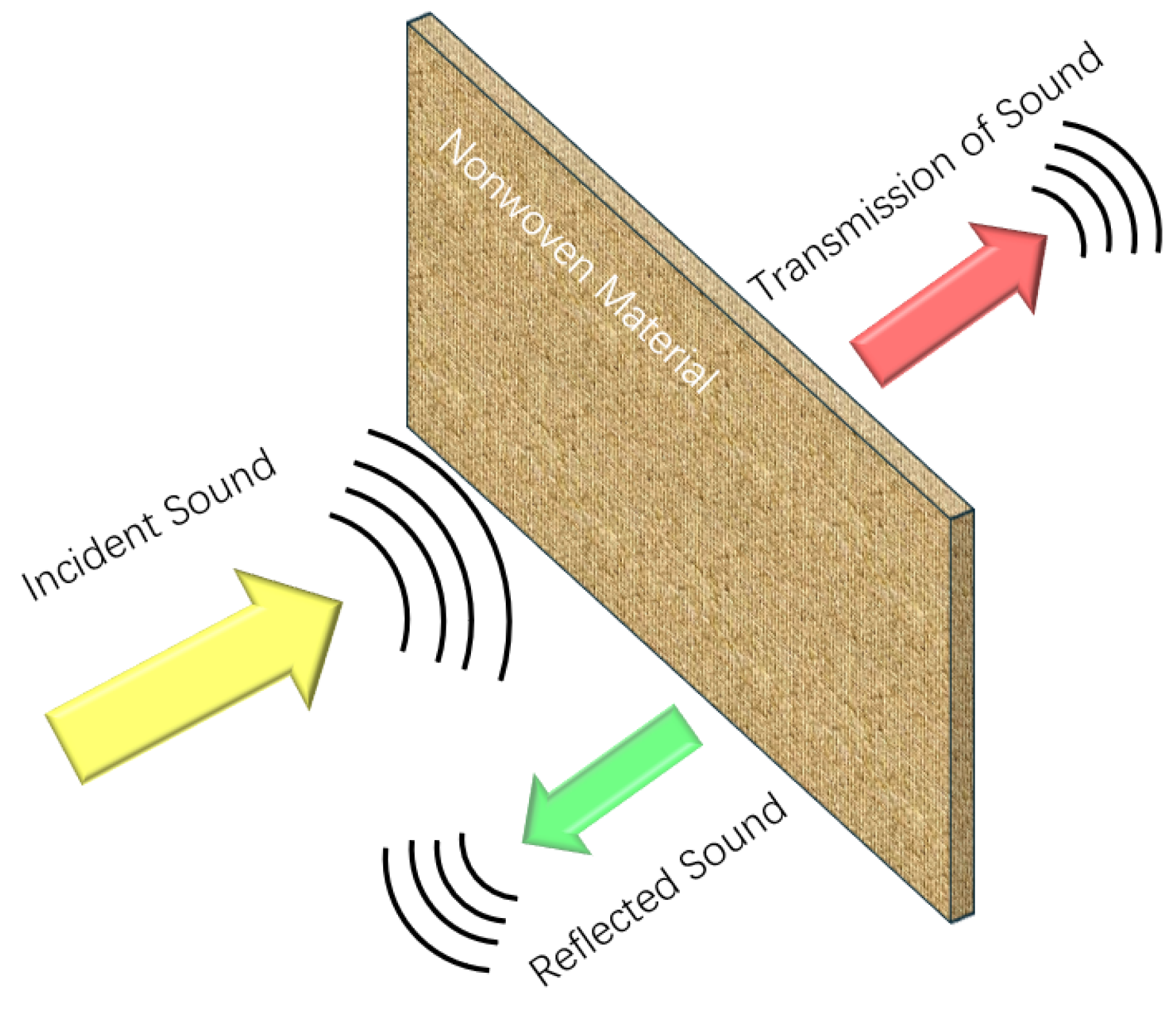

3.3.6. Sound Absorbing Materials

3.3.7. New Energy Applications

4. Summary and Future Directions

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, P.L.; Roschli, A.; Paranthaman, M.P.; Theodore, M.; Cramer, C.L.; Zangmeister, C.; Zhang, Y.P.; Urban, J.J.; Love, L. Recent developments in filtration media and respirator technology in response to COVID-19. Mrs Bulletin 2021, 46, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lu, C. Visualization analysis of big data research based on Citespace. Soft Computing 2019, 24, 8173–8186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufenus, R.; Yan, Y.R.; Dauner, M.; Kikutani, T. Melt-Spun Fibers for Textile Applications. Materials 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.W.; Han, W.L.; Wang, Y.D.; Xin, S.F.; Yang, J.R.; Zou, F.D.; Wang, X.H.; Xiao, C.F. Overview of the Fiber Dynamics during Melt Blowing. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2022, 61, 1004–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.B.; Zeng, Y.C. A Review on the Studies of Air Flow Field and Fiber Formation Process during Melt Blowing. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2019, 58, 11624–11637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, A.; Jin, K.L.; Mahanthappa, M.K.; Bates, F.S.; Ellison, C.J. Porous Fibers Templated by Melt Blowing Cocontinuous Immiscible Polymer Blends. Acs Macro Letters 2021, 10, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.Z.; Yagi, S.; Ashour, S.; Du, L.; Hoque, M.E.; Tan, L. A Review on Current Nanofiber Technologies: Electrospinning, Centrifugal Spinning, and Electro-Centrifugal Spinning. Macromolecular Materials and Engineering 2023, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Gu, H.; Cao, B. Interfacially polymerized thin-film composite membrane on UV-induced surface hydrophilic-modified polypropylene support for nanofiltration. Polymer Bulletin 2013, 71, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Li, Y.G.; Xie, D.D.; Zeng, Q.R.; Xu, H.B.; Ge, M.Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, R.; Dai, J.M.; et al. UV stabilizer intercalated layered double hydroxide to enhance the thermal and UV degradation resistance of polypropylene fiber. Polymer Testing 2023, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Chen, F.X.; Long, Y.Z.; Wu, H.; Li, Q.S.; Yu, S.X.; Wang, X.X.; Ning, X. Preparation of Polypropylene Micro and Nanofibers by Electrostatic-Assisted Melt Blown and Their Application. Polymers 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.B.; Guo, X.D.; Pei, H.B.; Liu, W.T.; Guo, W.; Fang, M.Q.; Liu, N.J.; Mo, Z.L. Polyphenylene sulfide hydrophobic composite coating with high stability, corrosion resistance and antifouling performance. Surfaces and Interfaces 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Yu, S.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, W.; Yousefzadeh, M.; Bubakir, M.M.; Li, H. Melt-electrospinning of Polyphenylene Sulfide. Fibers and Polymers 2019, 19, 2507–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, X.H.; Zhang, M.L.; Lyu, L.H.; Li, Z.H. Polyphenylene Sulfide-Based Membranes: Recent Progress and Future Perspectives. Membranes 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Xiong, S.W.; Huang, H.; Zhao, L.; Nie, K.; Chen, S.H.; Xu, J.; Yin, X.Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.X. Fabrication and application of poly (phenylene sulfide) ultrafine fiber. Reactive & Functional Polymers 2020, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wölfel, B.; Seefried, A.; Allen, V.; Kaschta, J.; Holmes, C.; Schubert, D. Recycling and Reprocessing of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Materials towards Nonwoven Processing. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Jia, H.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, J. Study on structure and property of PP/TPU melt-blown nonwovens. The Journal of The Textile Institute 2018, 110, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.C.; Zhang, Z.J.; Wei, W.; Yin, Y.Q.; Huang, C.X.; Ding, J.; Duan, Q.S. Investigation of a novel poly (lactic acid) porous material toughened by thermoplastic polyurethane. Journal of Materials Science 2022, 57, 5456–5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjmandi, R.; Yildirim, I.; Hatton, F.; Hassan, A.; Jefferies, C.; Mohamad, Z.; Othman, N. Kenaf fibers reinforced unsaturated polyester composites: A review. Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.H.; Guan, J.; Wang, X.F.; Yu, J.Y.; Ding, B. Polylactic Acid (PLA) Melt-Blown Nonwovens with Superior Mechanical Properties. Acs Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2023, 11, 4279–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Cao, Y.; Sun, H.; Han, J. The Structure and Properties of Biodegradable PLLA/PDLA for Melt-Blown Nonwovens. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 2016, 25, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabjańczyk-Wlazło, E.K.; Puszkarz, A.K.; Bednarowicz, A.; Tarzyńska, N.; Sztajnowski, S. The Influence of Surface Modification with Biopolymers on the Structure of Melt-Blown and Spun-Bonded Poly(lactic acid) Nonwovens. Materials 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Su, J.; Wang, M.; Hussain, M.; Yu, B.; Han, J. Study on dual-monomer melt-grafted poly(lactic acid) compatibilized poly(lactic acid)/polyamide 11 blends and toughened melt-blown nonwovens. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2018, 49, 748–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Li, P.X.; Wu, M.J.; Yu, X.Y.; Naito, K.; Zhang, Q.X. Halloysite nanotubes grafted polylactic acid and its composites with enhanced interfacial compatibility. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2021, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.Q.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.B.; Xiao, R. Preliminary study on fiber splitting of bicomponent meltblown fibers. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2004, 93, 2090–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.F.; Jiang, L.; Jia, H.Y.; Xing, X.L.; Sun, Z.H.; Chen, S.J.; Ma, J.W.; Jerrams, S. Study on Spinnability of PP/PU Blends and Preparation of PP/PU Bi-component Melt Blown Nonwovens. Fibers and Polymers 2019, 20, 1200–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.H.; Liu, G.H.; Chen, X.Y.; Babar, A.A.; Dong, Y.J.; Wang, X.F. Water electret charging based polypropylene/electret masterbatch composite melt-blown nonwovens with enhanced charge stability for efficient air filtration. J. Text. Inst. 2022, 113, 2128–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatihou, A.; Zouzou, N.; Dascalescu, L. Particle Collection Efficiency of Polypropylene Nonwoven Filter Media Charged by Triode Corona Discharge. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2017, 53, 3970–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Dai, Z.J.; He, B.; Ke, Q.F. The Effect of Temperature and Humidity on the Filtration Performance of Electret Melt-Blown Nonwovens. Materials 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y.; Yu, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhu, L. Study on corona charging characteristic of melt-blown polypropylene electret fabrics. Journal of Electrostatics 2023, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F.; Chen, G.J.; Zhou, Z.N.; Huang, C.L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Chen, C.; Ma, T.F.; Liu, P.P. Correlation of antibacterial performance to electrostatic field in melt-blown polypropylene electret fabrics. Journal of Electrostatics 2022, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyubaeva, P.; Zykova, A.; Podmasteriev, V.; Olkhov, A.; Popov, A.; Iordanskii, A. The Investigation of the Structure and Properties of Ozone-Sterilized Nonwoven Biopolymer Materials for Medical Applications. Polymers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planche, M.P.; Khatim, O.; Dembinski, L.; Coddet, C.; Girardot, L.; Bailly, Y. Velocities of copper droplets in the De Laval atomization process. Powder Technology 2012, 229, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, M.X.; Yao, X.H.; Lian, Z.Y.; Zhang, C.; Wei, W.J.; Huang, J. Preparation of Polypropylene Chelating Fibers by Quenching Pretreatment and Suspension Grafting and Their Pb Adsorption Ability. Fibers and Polymers 2014, 15, 2238–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.X.; Zhang, H.F.; Hou, J.; Wang, Y.X.; Deng, C.; Huang, C.; Jin, X.Y. Multi-Layered, Corona Charged Melt Blown Nonwovens as High Performance PM Air Filters. Polymers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Li, R.; Wang, J.; Wu, C. Study on Intercalated Melt-blown Nonwovens Based on Product Performance Control Mechanism. Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology 2023, 69, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, Y.; Molnár, K. A review of processing strategies to generate melt-blown nano/microfiber mats for high-efficiency filtration applications. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2022, 51, 137s–180s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaiah, G.B.; Mekonnen, S.; Solomon, E.; Melese, B.; Rao, K.P. Evaluation of contact angle of water proof coated fabric made from melt-blown polyester non-woven and acrylic polymeric materials. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2021, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E. Research on Performance Control of Intercalated Melt-blown Nonwoven Materials. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2023, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhnemann, T.; Schnebele, J.; Arne, W.; Windschiegl, I. Nanoval Technology—An Intermediate Process between Meltblown and Spunbond. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.M.; Li, R.Z.; Wu, M.L.; Yang, P.F. Preparation of alkali-modified amino-functionalized magnetic loofah biochar and its adsorption properties for uranyl ions. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry 2023, 332, 3079–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H.; Bhoi, P.R. An overview of non-biodegradable bioplastics. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.J.; Zhu, J.; Yan, J.Q.; Su, J.F.; Gao, Y.F.; Zhang, X.; Ke, Q.F.; Parsons, G.N. An Advanced Dual-Function MnO2-Fabric Air Filter Combining Catalytic Oxidation of Formaldehyde and High-Efficiency Fine Particulate Matter Removal. Advanced Functional Materials 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Yeom, B.Y.; Wilkie, A.; Pourdeyhimi, B.; Khan, S.A. Fabrication of nanofiber meltblown membranes and their filtration properties. Journal of Membrane Science 2013, 427, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgórski, A.; Bałazy, A.; Gradoń, L. Application of nanofibers to improve the filtration efficiency of the most penetrating aerosol particles in fibrous filters. Chemical Engineering Science 2006, 61, 6804–6815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Dai, Z.; Huang, C.; Ke, Q.; Gu, L. Preparation and Filtration Performance of PTFE Membrane/Bi-component Melt-Blown Nonwoven Composite Filter Material. Journal of Donghua University(Natural Science Edition) 2018, 44, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.; Shibahara, K.; Bhuiyan, A.H.; Nakane, K. Preparation and characterization of polypropylene nanofibrous membrane for the filtration of textile wastewater. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2022, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhen, Q.; Yan, Y.; Guan, X.; Liu, R.; Liu, Y. Polypropylene/polyester composite micro/nano-fabrics with linear valley-like surface structure for high oil absorption. Materials Letters 2020, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassod, A.; Abedalwafa, M.A.; Xu, G.B. Evaluation of polypropylene melt blown nonwoven as the interceptor for oil. Environmental Technology 2021, 42, 2784–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.L.; Chen, H.N.; Luo, Z.W.; Lian, Z.Y.; Wei, W. Selective Removal of Pb(II) Ions from Aqueous Solutions by Acrylic Acid/Acrylamide Comonomer Grafted Polypropylene Fibers. Fibers and Polymers 2017, 18, 1459–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolovic, S.S.; Kiralj, A.I.; Sokolovic, D.S.; Jokic, A.I. Application of waste polypropylene bags as filter media in coalescers for oily water treatment. Hemijska Industrija 2019, 73, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Long, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Jiao, F. MnOx-mineralized oxidized-polypropylene membranes for highly efficient oil/water separation. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xiao, C.; Xu, N. Evaluation of polypropylene and poly (butylmethacrylate-co-hydroxyethylmethacrylate) nonwoven material as oil absorbent. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2012, 20, 4137–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Hu, J.J.; Wang, G.F.; Cui, J.Q.; Zhang, Y.F.; Zhen, Q. Facile Preparation of Hydrophobic PLA/PBE Micro-Nanofiber Fabrics via the Melt-Blown Process for High-Efficacy Oil/Water Separation. Polymers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.S.; Zhao, T.; Li, C.T.; Pan, H.W.; Tan, Z.Y.; Yang, H.L.; Zhang, H.L. Preparation and characterization of biodegradable polylactic acid/poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) melt-blown nonwovens for oil-water separation. Colloid. Polym. Sci. 2024, 302, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.N.; Guo, M.L.; Yao, X.H.; Luo, Z.W.; Dong, K.; Lian, Z.Y.; Wei, W.J. Green and Efficient Synthesis of an Adsorbent Fiber by Plasma-induced Grafting of Glycidyl Methacrylate and Its Cd(II) Adsorption Performance. Fibers and Polymers 2018, 19, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jia, J.; Liu, J.a.; Liang, X. Hg selective adsorption on polypropylene-based hollow fiber grafted with polyacrylamide. Adsorption Science & Technology 2017, 36, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffar, A.; Carreau, P.J.; Ajji, A.; Kamal, M.R. Development of polypropylene microporous hydrophilic membranes by blending with PP-g-MA and PP-g-AA. Journal of Membrane Science 2014, 462, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhao, C.; Bai, M.; Li, T. Study of Graft Copolymerization on Polypropylene Fiber and Its Adsorption Behaviors. Journal of Shenyang Institute of Chemical Technology 2010, 24, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.W.; Li, L.; Guo, M.L.; Jiang, H.; Geng, W.H.; Wei, W.J.; Lian, Z.Y. Water-solid Suspension Grafting of Dual Monomers on Polypropylene to Prepare Ion-imprinted Fibers for Selective Adsorption of Cr(VI). Fibers and Polymers 2020, 21, 2729–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.W.; Chen, H.N.; Xu, J.J.; Guo, M.L.; Lian, Z.Y.; Wei, W.J.; Zhang, B.H. Surface grafting of styrene on polypropylene by argon plasma and its adsorption and regeneration of BTX. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2018, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.Y.; Xu, Y.Y.; Zuo, J.; Qian, H.; Luo, Z.W.; Wei, W.J. Preparation of PP-g-(AA-MAH) Fibers Using Suspension Grafting and Melt-Blown Spinning and its Adsorption for Aniline. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bing, L.; Yongchun, D. Coordination Kinetics of Different Carboxylic Fiber with Fe3+ and Catalytic Degradation Performance of Their Fe3+ Complexes. Chem. J. Chin. Univ.-Chin. 2014, 35, 1761–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, L.; Nowak, B.; Jackiewicz-Zagórska, A.; Glofit-Szymczak, R.L.; Górny, R.L. Functionalized zinc oxide nanorods - polypropylene nonwoven composite with high biological and photocatalytic activity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H.; Sun, H.; Wang, J.Q.; Yu, B. Preparation of TiO2/MIL-88B(Fe)/polypropylene composite melt-blown nonwovens and study on dye degradation properties. Journal of Textile Research 2020, 41, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellweg, D.; Lepper, P.M.; Nowak, D.; Köhnlein, T.; Olgemöller, U.; Pfeifer, M. Stellungnahme der DGP zur Auswirkung von Mund-Nasenmasken auf den Eigen- und Fremdschutz bei aerogen übertragbaren Infektionen in der Bevölkerung. Pneumologie 2020, 74, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čepič, G.; Gorjanc, D.Š. Influence of the Web Formation of a Basic Layer of Medical Textiles on Their Functionality. Polymers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gericke, A.; Venkataraman, M.; Militky, J.; Steyn, H.; Vermaas, J. Unmasking the Mask: Investigating the Role of Physical Properties in the Efficacy of Fabric Masks to Prevent the Spread of the COVID-19 Virus. Materials 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubacka, A.; Ferrer, M.; Cerrada, M.L.; Serrano, C.; Sánchez-Chaves, M.; Fernández-García, M.; de Andrés, A.; Riobóo, R.J.J.; Fernández-Martín, F.; Fernández-García, M. Boosting TiO2-anatase antimicrobial activity: Polymer-oxide thin films. Applied Catalysis B-Environmental 2009, 89, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.H.; Hwang, Y.H.; Yi, S.C. Antibacterial properties of padded PP/PE nonwovens incorporating nano-sized silver colloids. Journal of Materials Science 2005, 40, 5413–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wisuthiphaet, N.; Bolt, H.; Nitin, N.; Zhao, Q.H.; Wang, D.; Pourdeyhimi, B.; Grondin, P.; Sun, G. N-Halamine Polypropylene Nonwoven Fabrics with Rechargeable Antibacterial and Antiviral Functions for Medical Applications. Acs Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2021, 7, 2329–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Song, M.; Sui, D.; Duan, S.; Xu, F.-J. A natural polysaccharide-based antibacterial functionalization strategy for liquid and air filtration membranes. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2022, 10, 2471–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenteno, A.; Lieberwirth, I.; Catalina, F.; Corrales, T.; Guerrero, S.; Vasco, D.A.; Zapata, P.A. Study of the effect of the incorporation of TiO2 nanotubes on the mechanical and photodegradation properties of polyethylenes. Composites Part B-Engineering 2017, 112, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, I.; Armbruster, F.; Polak, D.; Kaur, S.; Hussy, S.; Thiem, T.; Gerhardts, A.; Szwast, M. Antibacterial, Antifungal, and Antibiotic Adsorption Properties of Graphene-Modified Nonwoven Materials for Application in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Processes 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura Alcaraz, M.P.; Bonet-Aracil, M.; Julià Sanchís, E.; Segura Alcaraz, J.G.; Seguí, I.M. Textiles in architectural acoustic conditioning: a review. The Journal of The Textile Institute 2021, 113, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz, E.; Borysiak, S.; Paukszta, D. Polypropylene-lignocellulosic material composites as promising sound absorbing materials. Polimery 2009, 54, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivri, Ç.; Haji, A. Surface Coating of Needle-Punched Nonwovens with Meltblown Nonwovens to Improve Acoustic Properties. Coatings 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L.; Bao, W.; Shi, L.; Zuo, B.Q.; Gao, W.D. General regression neural network for prediction of sound absorption coefficients of sandwich structure nonwoven absorbers. Applied Acoustics 2014, 76, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, P.; Azimian, M.; Wiegmann, A.; Zarrebini, M. Experimental and computational analysis of sound absorption behavior in needled nonwovens. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2018, 426, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, A.B.; Pal, R.; Ghosh, A.K. Foam processability of polypropylene/sisal fiber composites having near-critical fiber length for acoustic absorption properties. Polymer Composites 2024, 45, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, G.; Messiry, M.E. Effect of microfiber layers on acoustical absorptive properties of nonwoven fabrics. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2019, 50, 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L.; Liu, X.J.; Xu, Y.; Bao, W. The acoustic characteristics of dual-layered porous nonwovens: a theoretical and experimental analysis. J. Text. Inst. 2014, 105, 1084–U1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.H.; Shao, X.F.; Li, X.C.; Zhang, B.; Yan, X. A low-cost and environmental-friendly microperforated structure based on jute fiber and polypropylene for sound absorption. Journal of Polymer Research 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.H.; Li, X.C.; Yan, X. Mechanical and Acoustic Properties of Jute Fiber-Reinforced Polypropylene Composites. Acs Omega 2021, 6, 31154–31160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.X.; Hou, Q.X.; Liu, W.; Liang, Z.H.; Wang, B.; Zhang, H.L. Wet-Laid Formation and Strength Enhancement of Alkaline Battery Separators Using Polypropylene Fibers and Polyethylene/Polypropylene Bicomponent Fibers as Raw Materials. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2017, 56, 7739–7746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Niu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, G. Suppressing the Shuttle Effect in Lithium-Sulfur Batteries by a UiO-66-Modified Polypropylene Separator. Acs Omega 2019, 4, 10328–10335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.D.; Zhu, H.Q.; Yang, L.Z.; Wang, X.W.; Liu, Z.W.; Chen, Q. Plasma Modified Polypropylene Membranes as the Lithium-Ion Battery Separators. Plasma Science & Technology 2016, 18, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.D.; Xue, N.X.; Xie, J.Y.; Xu, R.J.; Lei, C.H. Separator Aging and Performance Degradation Caused by Battery Expansion: Cyclic Compression Test Simulation of Polypropylene Separator. Journal of the Electrochemical Society 2021, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.Y.; Zhang, Z.J.; Wei, J.K.; Jing, Y.D.; Guo, W.; Xie, Z.Z.; Qu, D.Y.; Liu, D.; Tang, H.L.; Li, J.S. A synergistic modification of polypropylene separator toward stable lithium-sulfur battery. Journal of Membrane Science 2020, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Wang, J.Y.; Song, Z.H.; Li, C.M.; Wang, W.K.; Wang, A.B.; Huang, Y.Q. Multifunctional Asymmetric Separator Constructed by Polyacrylonitrile-Derived Nanofibers for Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces 2023, 15, 51241–51251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghim, M.H.; Nahvibayani, A.; Eqra, R. Mechanical properties of heat-treated polypropylene separators for Lithium-ion batteries. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2022, 62, 3049–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.L.; Yang, F.; Xiang, M.; Cao, Y.; Wu, T. Development of Multilayer Polypropylene Separators for Lithium-Ion Batteries via an Industrial Process. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2021, 60, 11611–11620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicy, K.; Kalarikkal, N.; Stephen, A.M.; Rouxel, D.; Thomas, S. Facile fabrication of microporous polypropylene membrane separator for lithium-ion batteries. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2020, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.N.; Tian, W.; Li, D.D.; Quan, L.J.; Zhu, C.Y. The high performances of SiO2-coated melt-blown non-woven fabric for lithium-ion battery separator. J. Text. Inst. 2018, 109, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiso, S.; Petrecca, M.J.; Williams, A.H.; Christopher, J.; Velev, O.D.; Pourdeyhimi, B.; Fedkiw, P.S. Structure-Performance Relationships of Li-Ion Battery Fiber-Based Separators. Acs Applied Polymer Materials 2022, 4, 3676–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).