Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

11 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

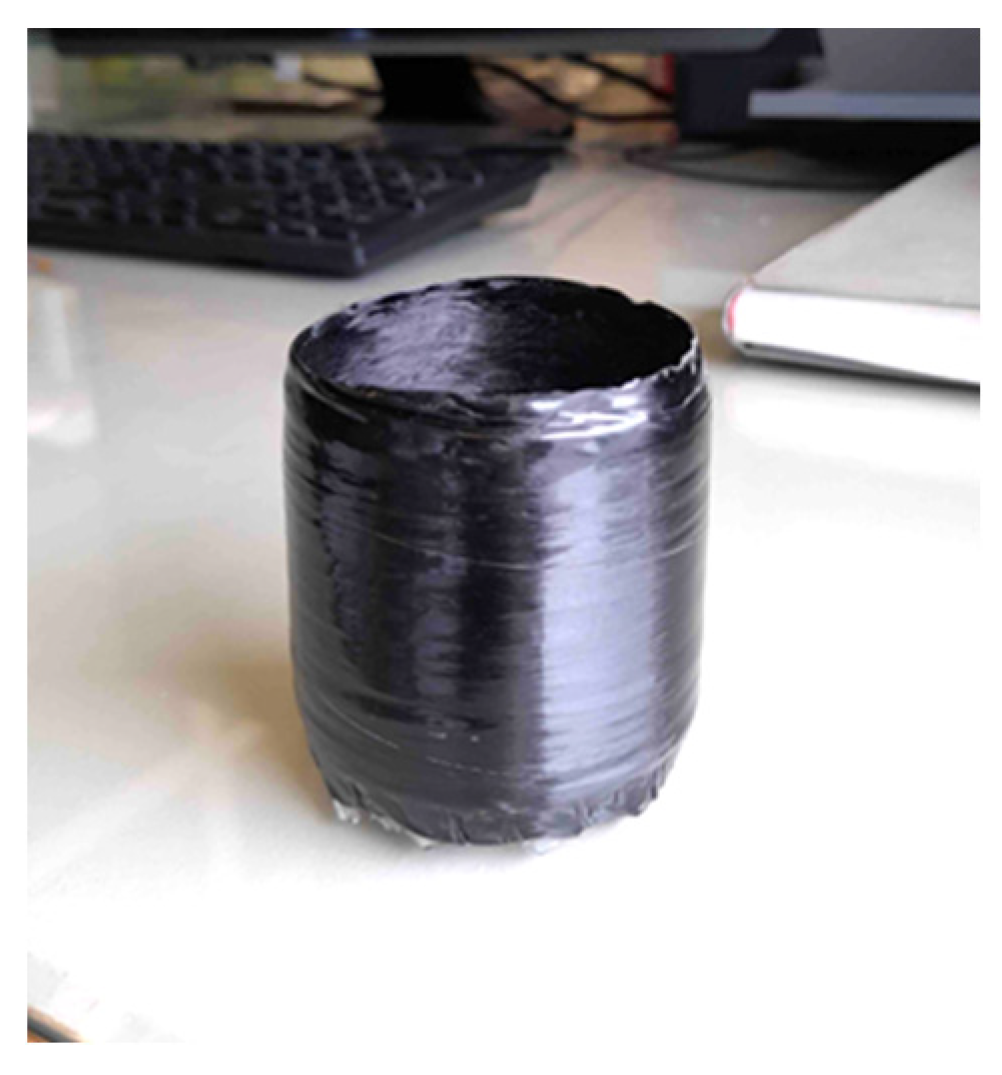

2.1. Materials

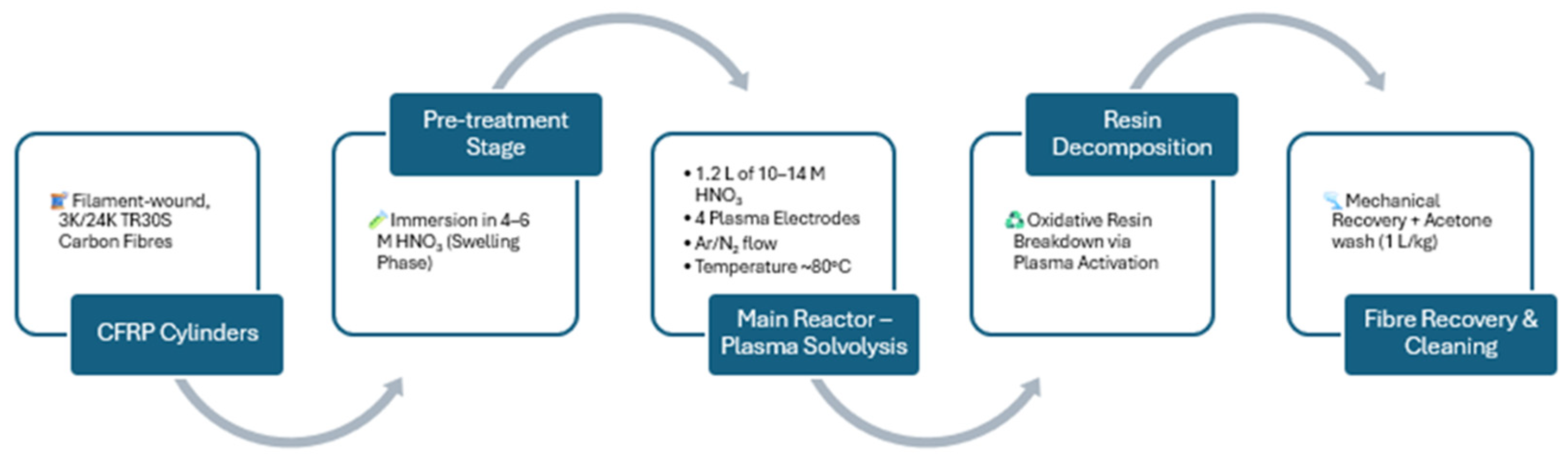

2.2. The Plasma-Assisted Solvolysis Process

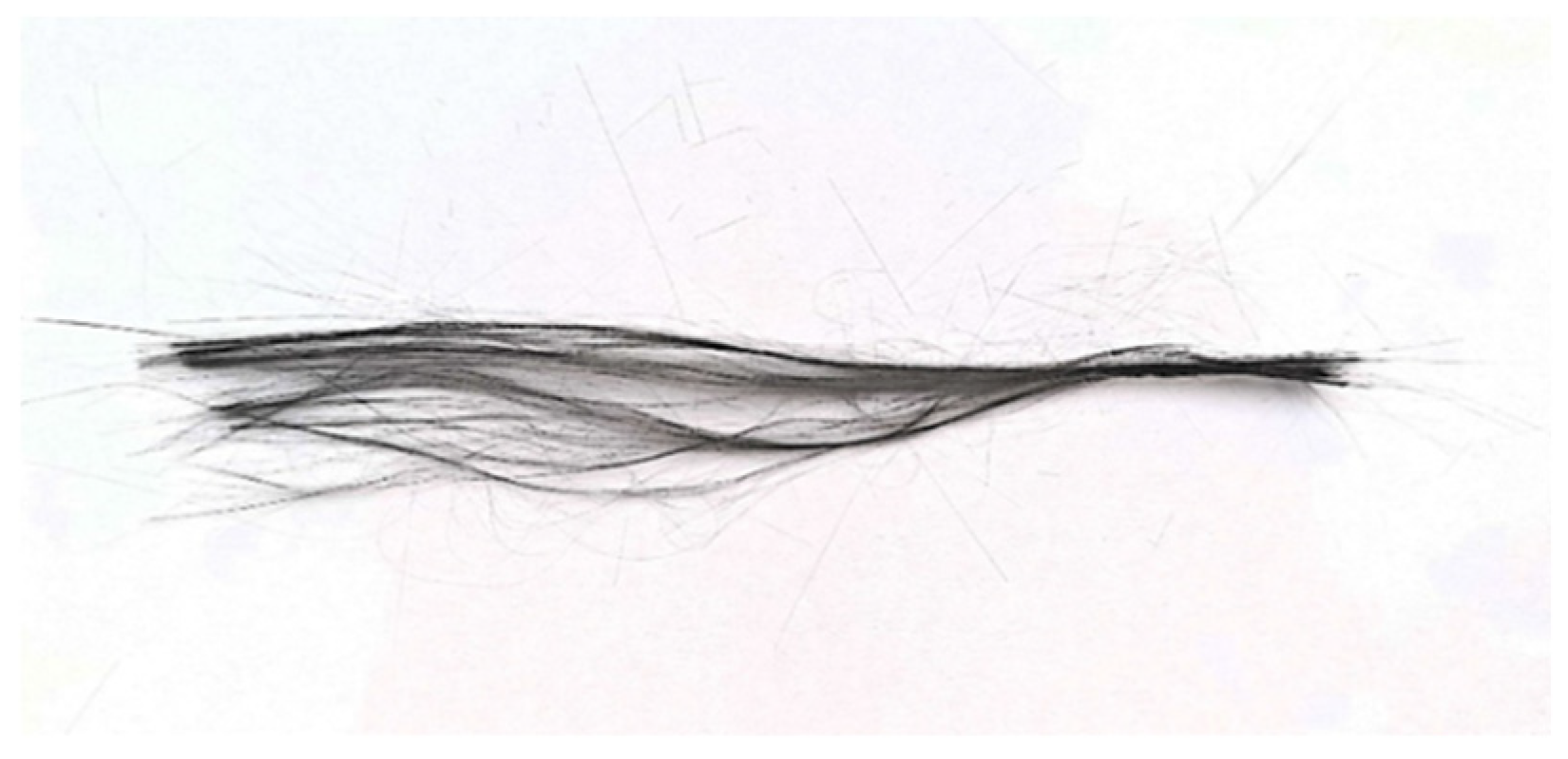

2.3. Characterization of Fibers

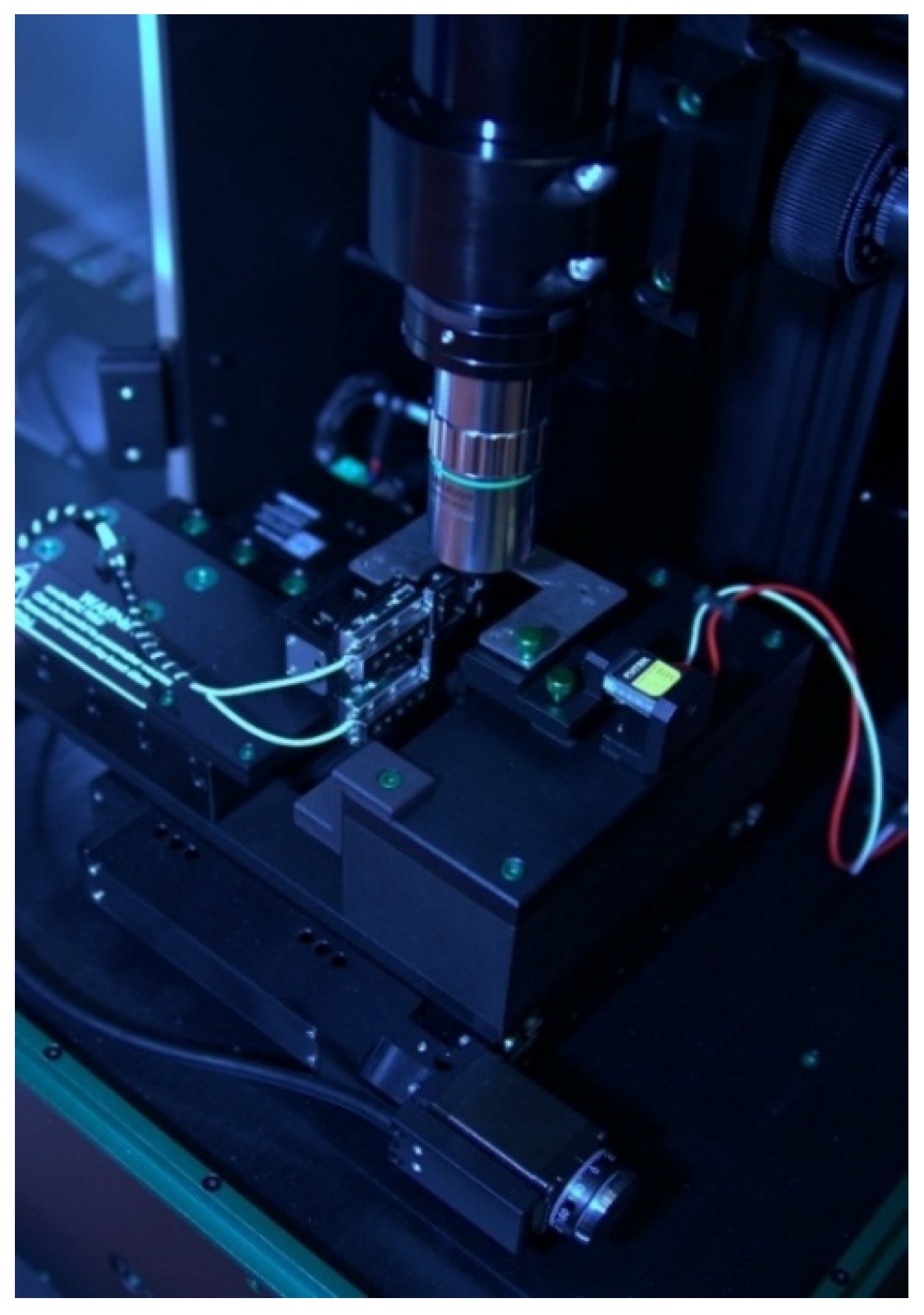

2.3.1. Single-Fiber Tension Test

- Tensile strength :

- Young’s modulus :

- Elongation at break ε:

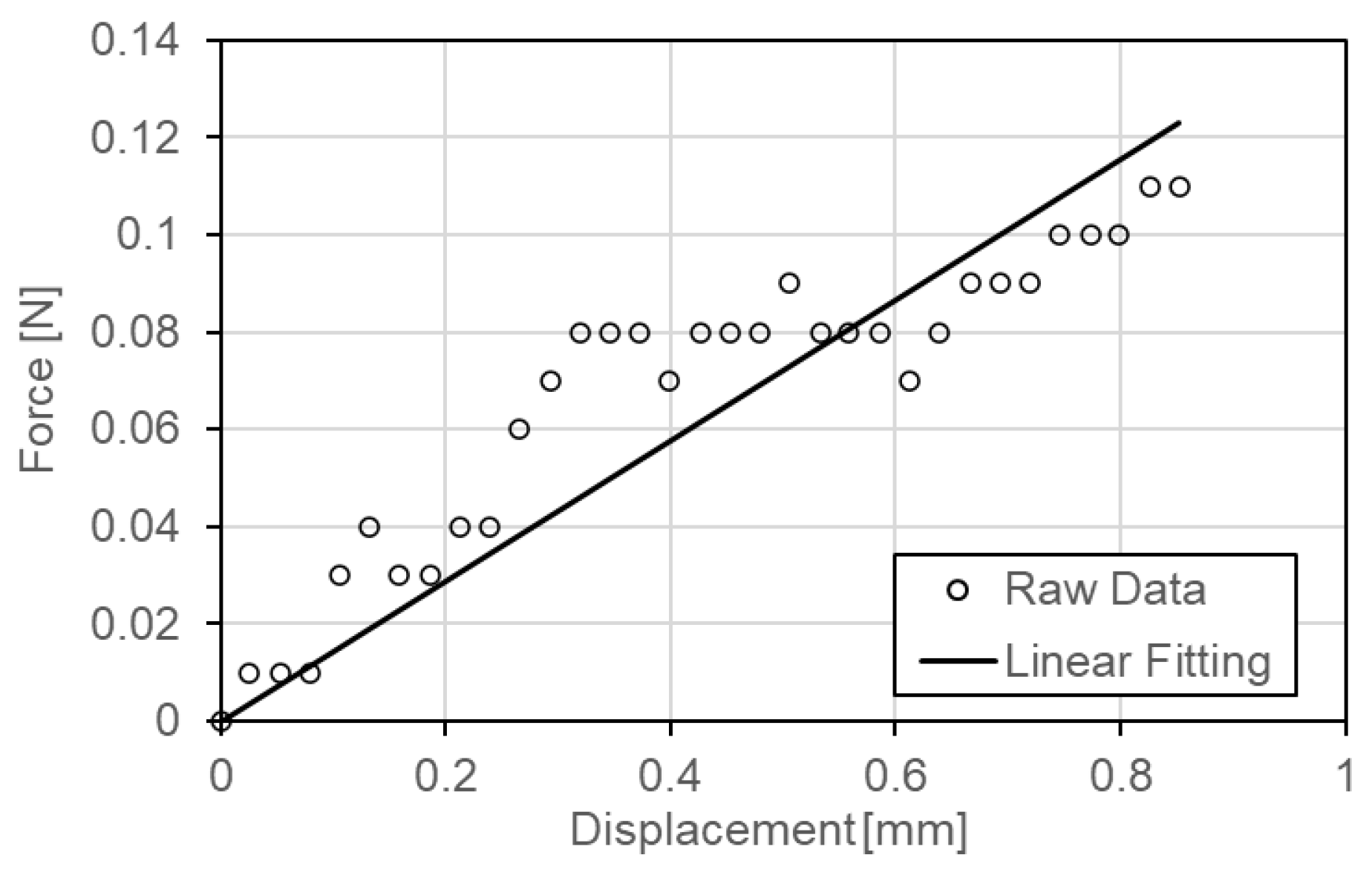

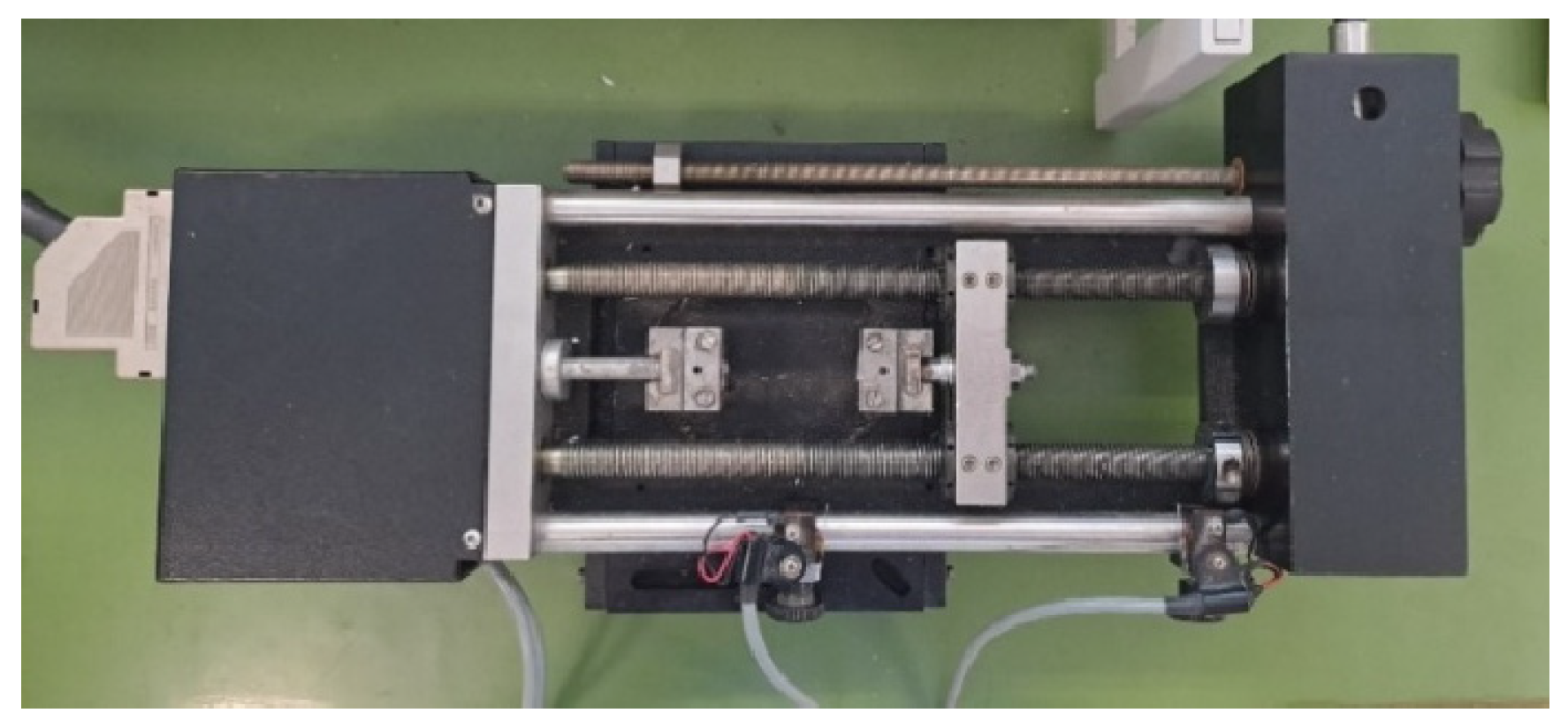

2.3.2. Microbond Test

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Statistical Analysis

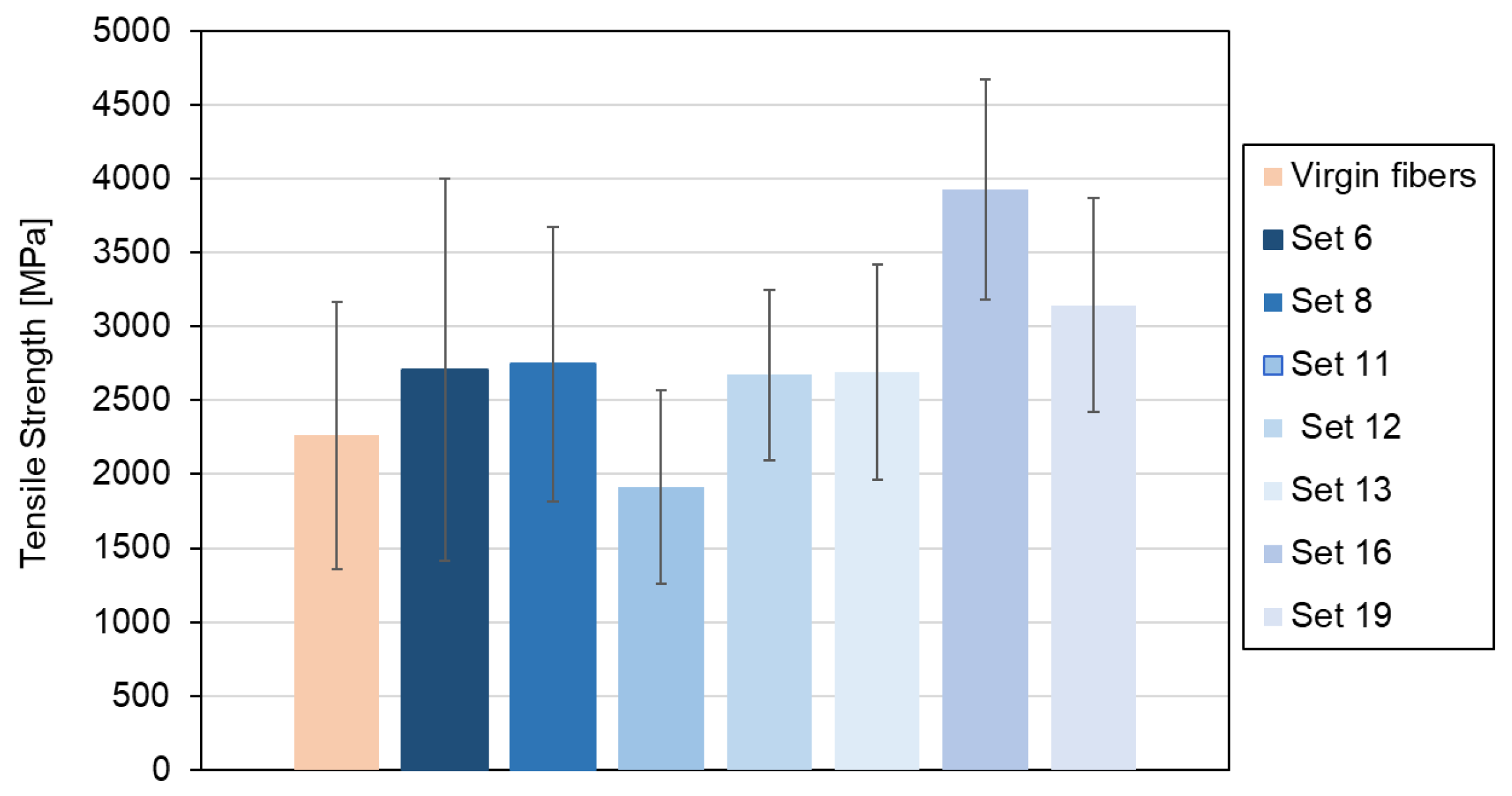

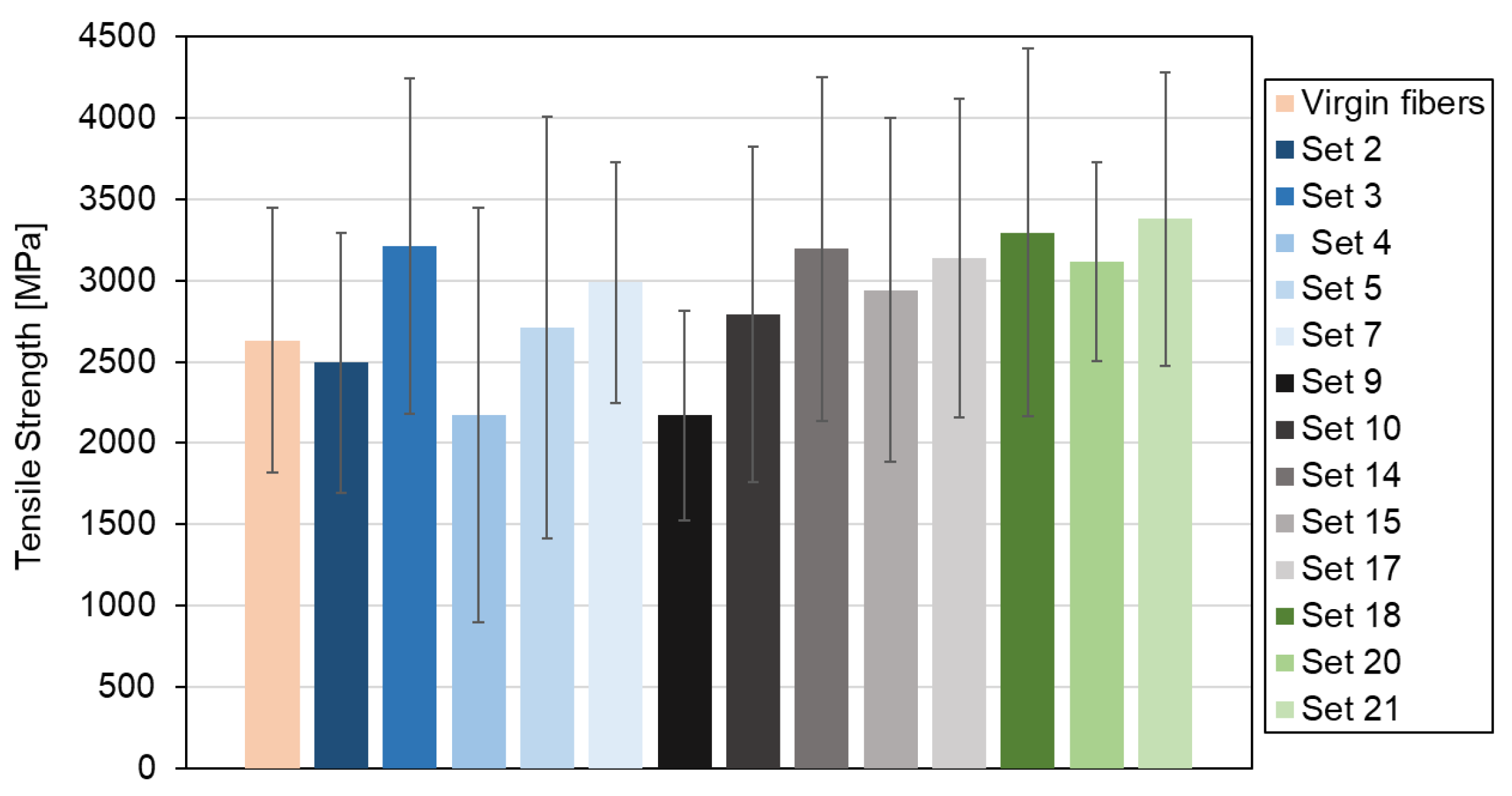

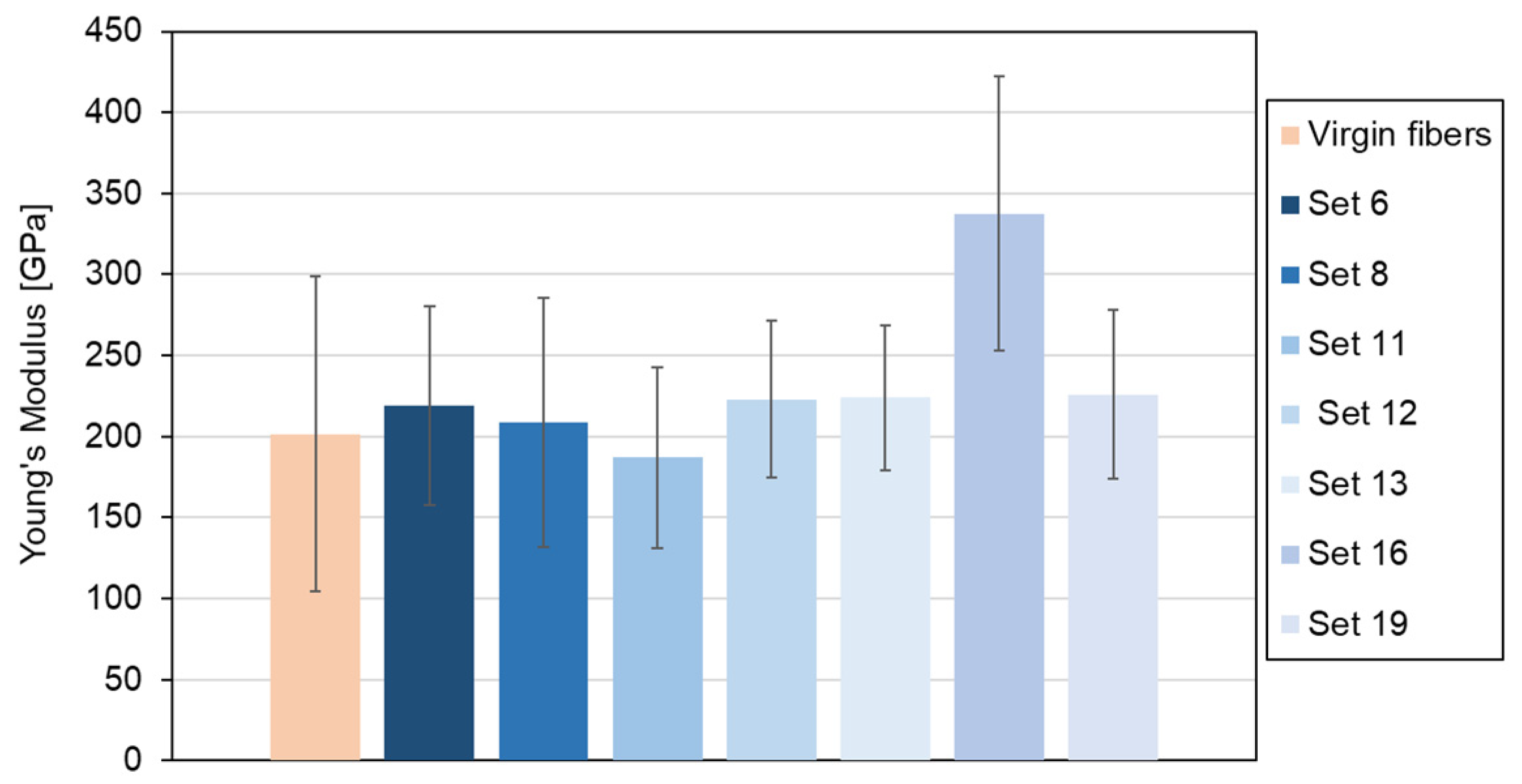

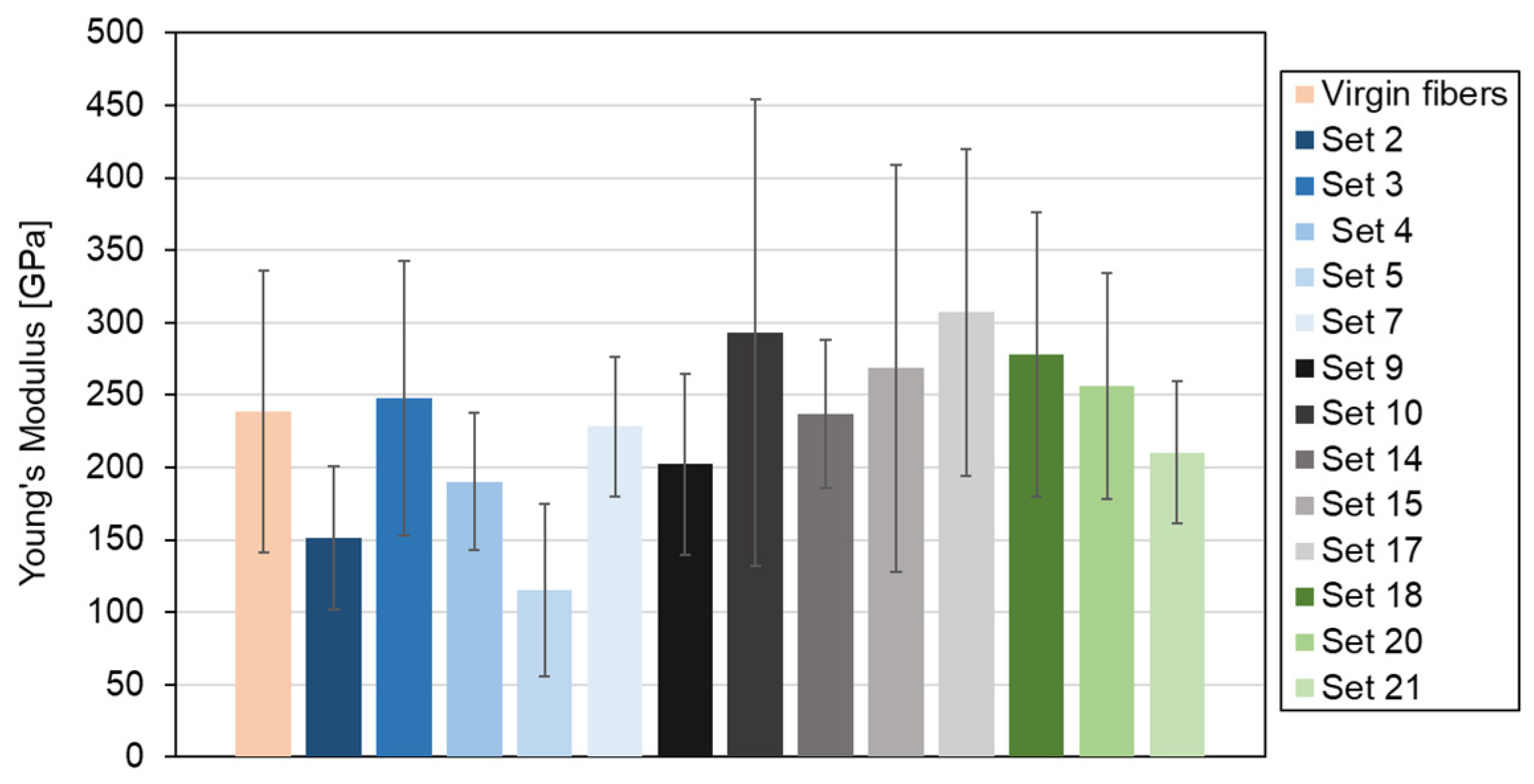

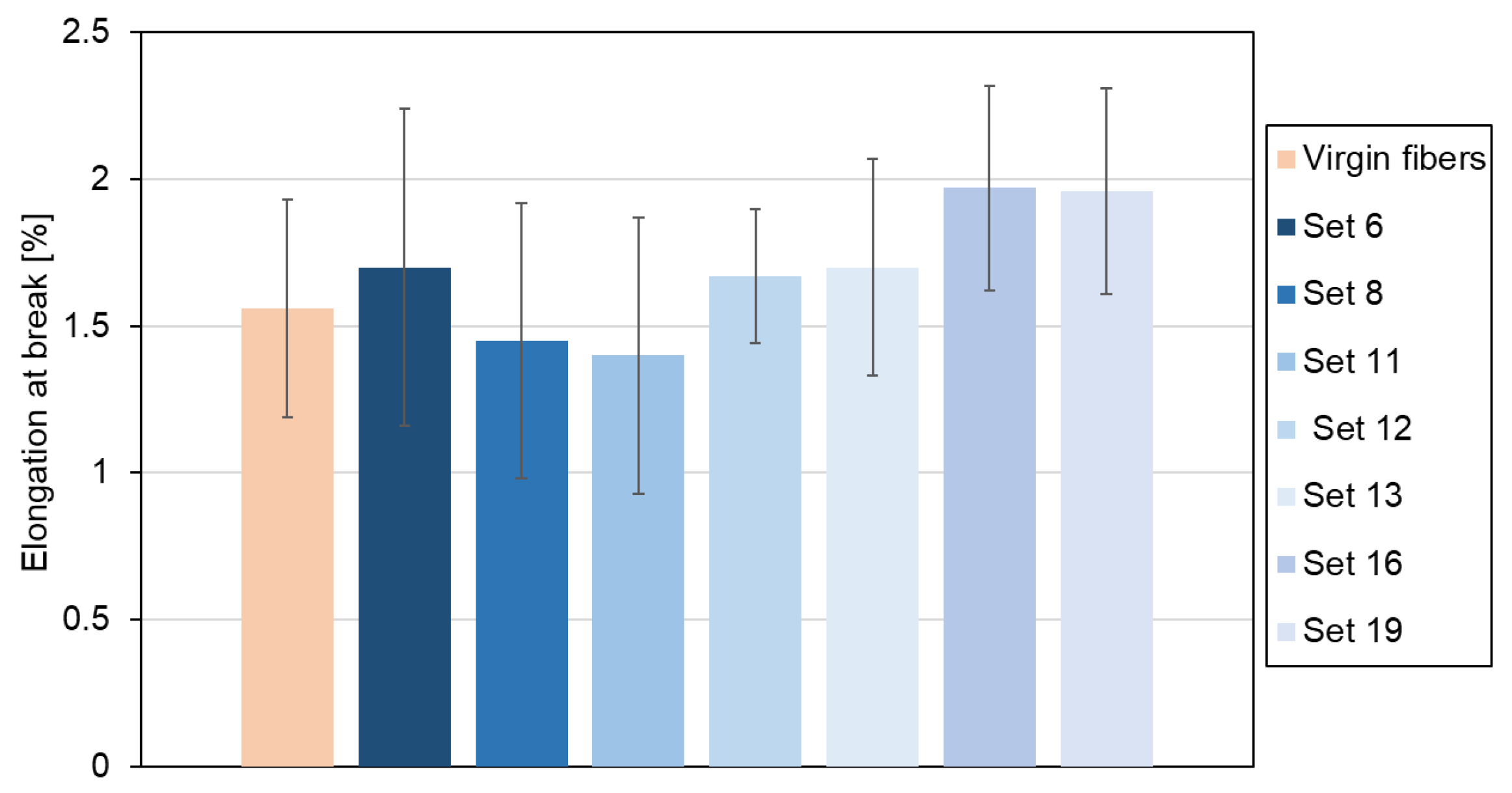

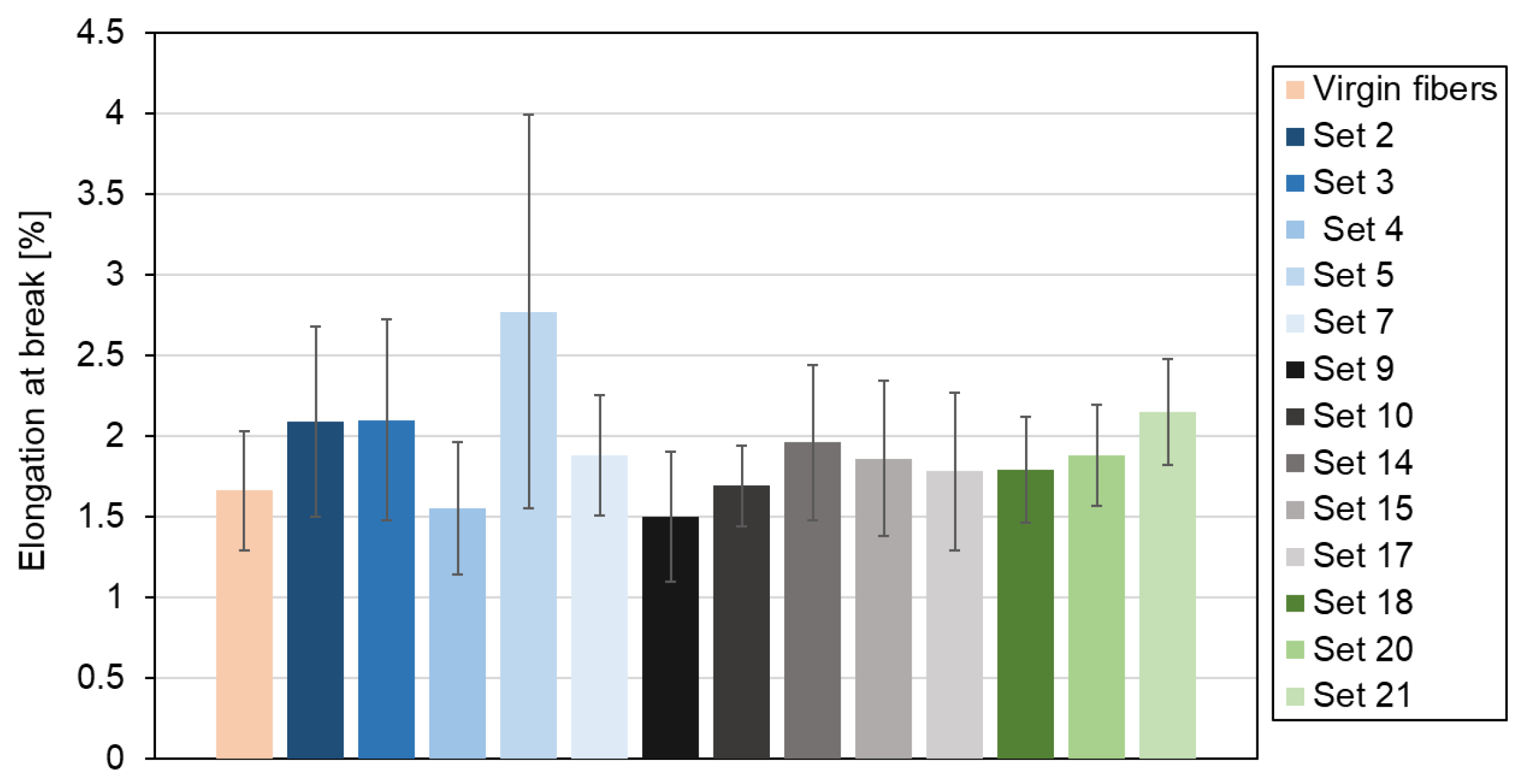

3.2. Mechanical Properties of Fibers

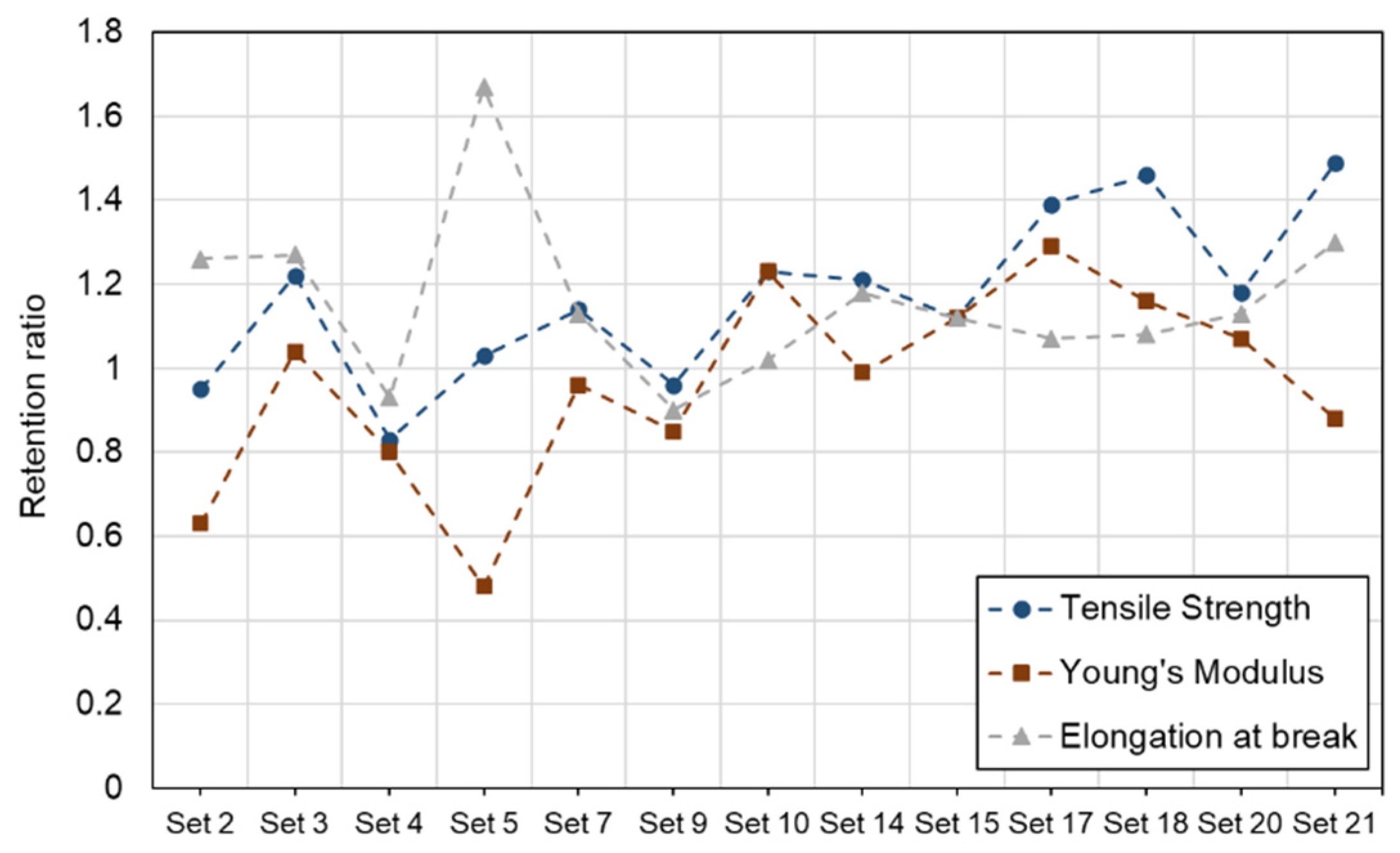

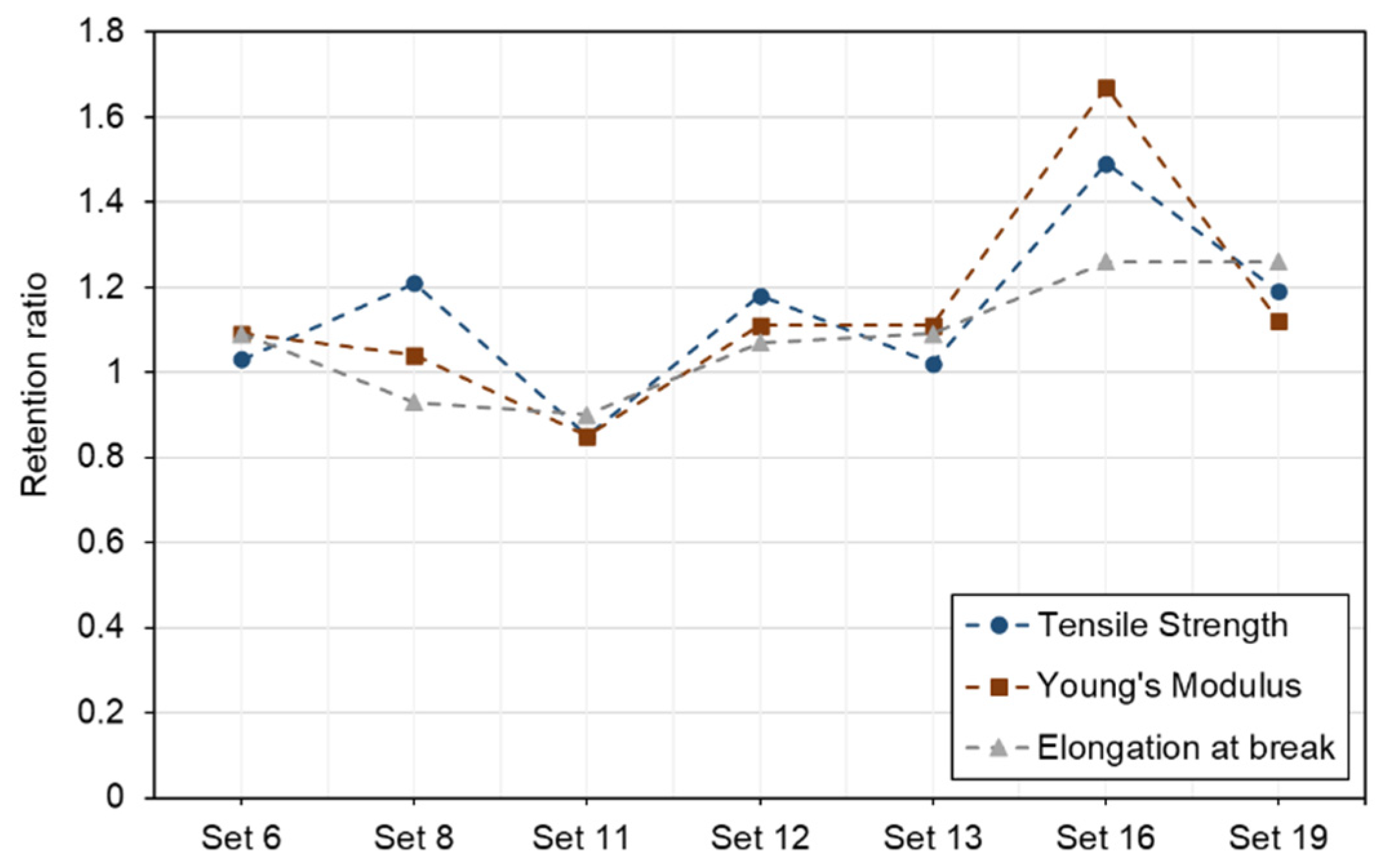

3.3. Retention Analysis

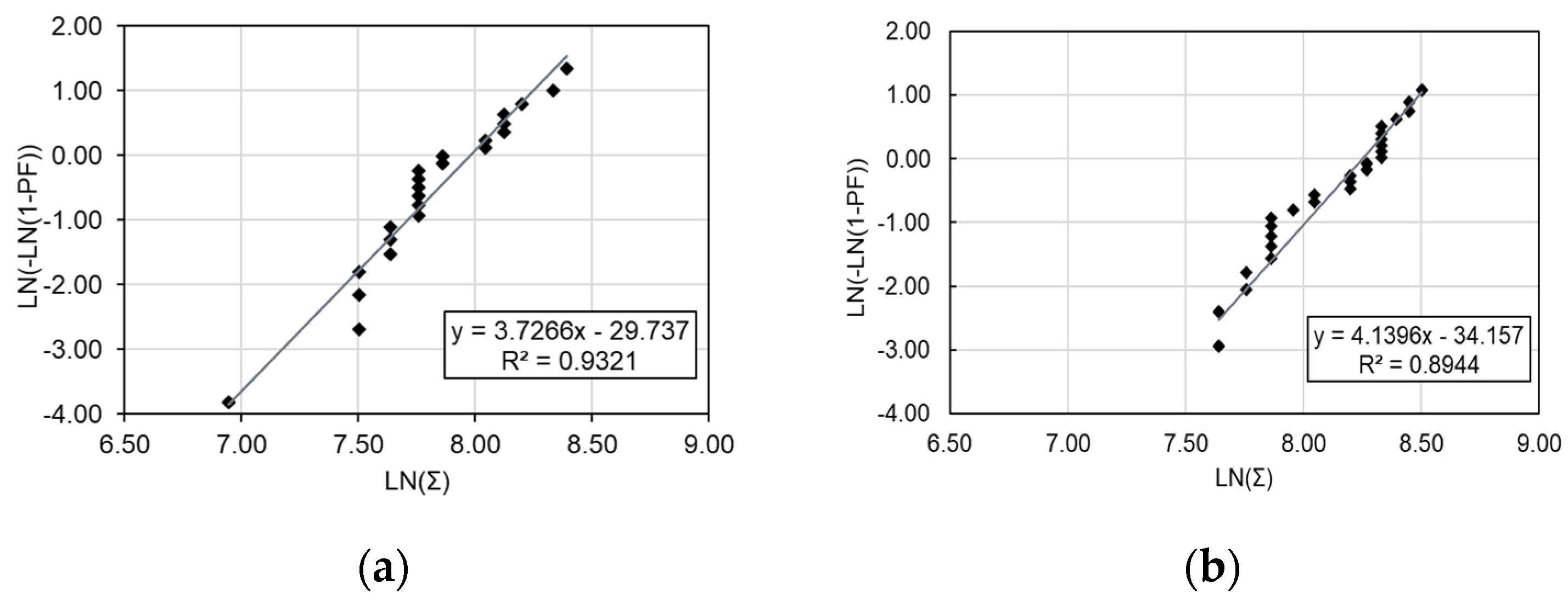

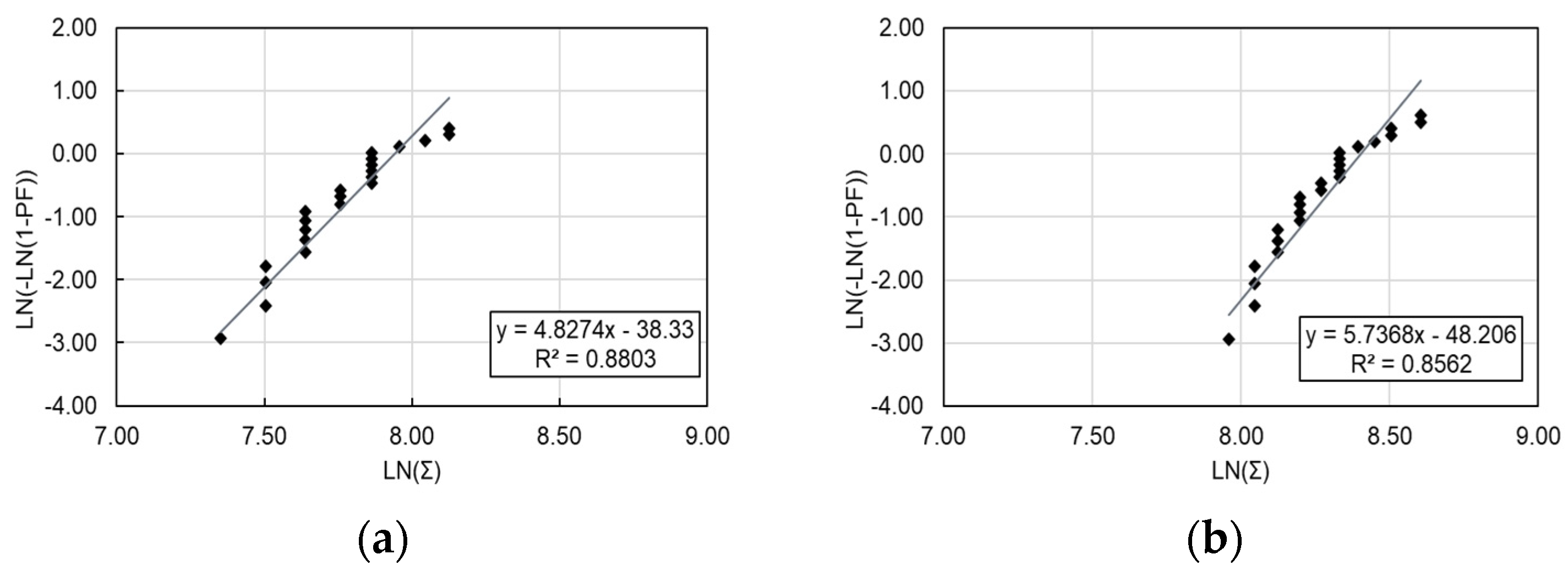

3.4. Weibull Analysis

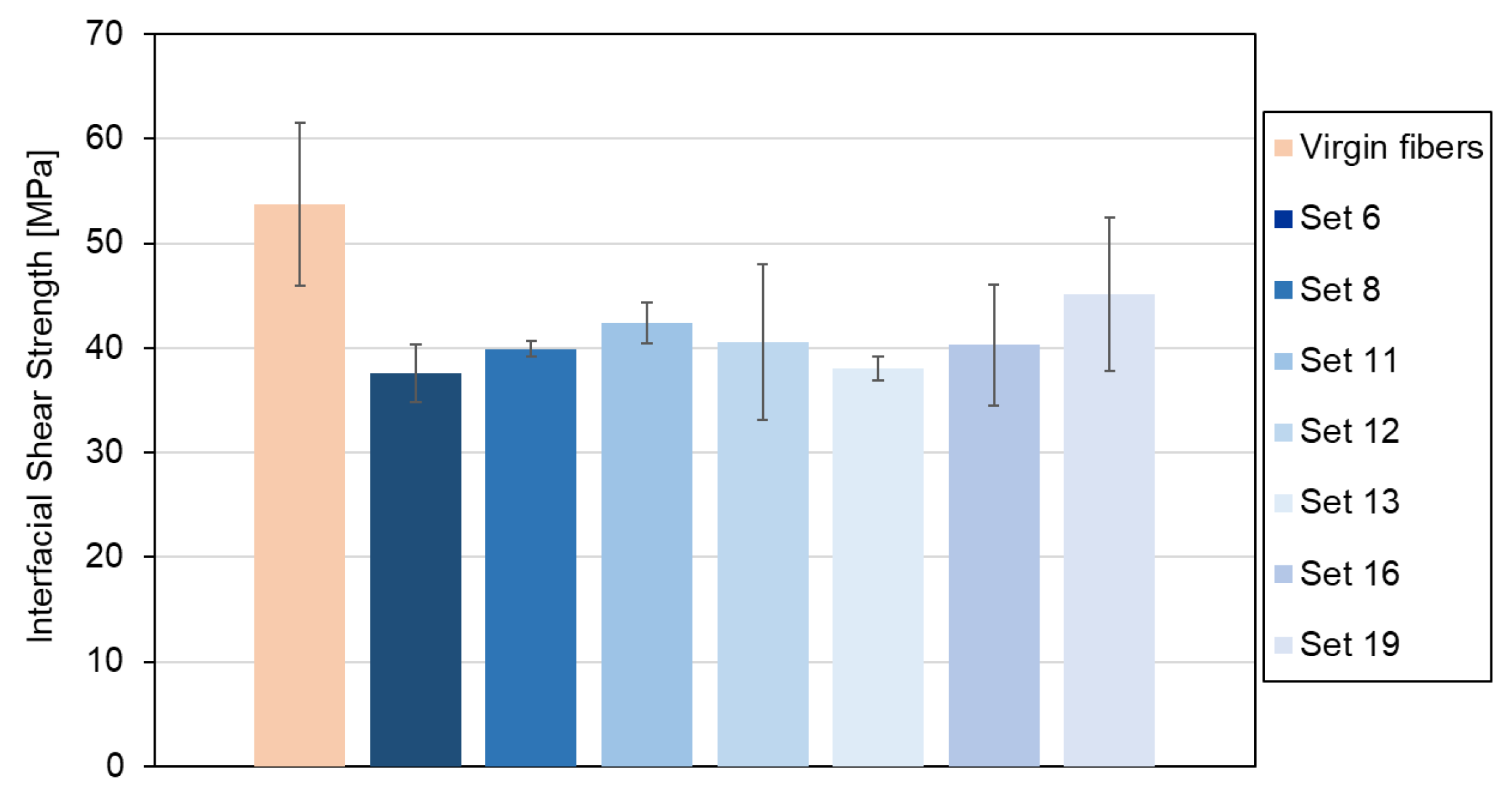

3.5. Interfacial Shear Strength

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Recent Developments in the Synthesis of Composite Materials for Aerospace: Case Study - MedCrave Online Available online: https://medcraveonline.com/MSEIJ/recent-developments-in-the-synthesis-of-composite-materials-for-aerospace-case-study.html (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Lin, G.; Vaidya, U.; Wang, H. Past, Present and Future Prospective of Global Carbon Fibre Composite Developments and Applications. Composites Part B: Engineering 2023, 250, 110463. [CrossRef]

- Basri, M.H. APPLICATION OF CARBON FIBER REINFORCED PLASTICS IN AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY: A REVIEW. 2018, 1.

- High Performance Composites Market Size to Hit USD 159.35 Bn by 2034 Available online: https://www.precedenceresearch.com/high-performance-composites-market (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Composite Waste: Understanding Regulations and Finding Circular Solutions for a Growing Problem Available online: https://www.circularise.com/blogs/composite-waste-understanding-regulations-and-finding-circular-solutions-for-a-growing-problem (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Morici, E.; Dintcheva, N.Tz. Recycling of Thermoset Materials and Thermoset-Based Composites: Challenge and Opportunity. Polymers 2022, 14, 4153. [CrossRef]

- Aldosari, S.M.; AlOtaibi, B.M.; Alblalaihid, K.S.; Aldoihi, S.A.; AlOgab, K.A.; Alsaleh, S.S.; Alshamary, D.O.; Alanazi, T.H.; Aldrees, S.D.; Alshammari, B.A. Mechanical Recycling of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer in a Circular Economy. Polymers 2024, 16, 1363. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, J. A Review of Recycling Methods for Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16855. [CrossRef]

- Ateeq, M. A State of Art Review on Recycling and Remanufacturing of the Carbon Fiber from Carbon Fiber Polymer Composite. Composites Part C: Open Access 2023, 12, 100412. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A.M.; Kneissl, L.M.; Nunes, S.; Emami, N. Recycled Carbon Fibers as an Alternative Reinforcement in UHMWPE Composite. Circular Economy within Polymer Tribology. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2022, 34, e00510. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Xu, L.; Shang, X.; Shen, Z.; Fu, R.; Li, W.; Guo, L. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties and Pyrolysis Products of Carbon Fibers Recycled by Microwave Pyrolysis. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 13529–13537. [CrossRef]

- Alguacil, M.C.; Umeki, K.; You, S.; Joffe, R. Evolution of Carbon Fiber Properties during Repetitive Recycling via Pyrolysis and Partial Oxidation. Carbon Trends 2025, 18, 100438. [CrossRef]

- Charitidis J. Panagiotis Recycling of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Composites-A Review. IJARSCT 2024, 431–445. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sibari, R.; Chakraborty, S.; Baz, S.; Gresser, G.T.; Benner, W.; Brämer, T.; Steuernagel, L.; Ionescu, E.; Deubener, J.; et al. Epoxy-Based Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Plastics Recycling via Solvolysis with Non-Oxidizing Methanesulfonic Acid. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 2024, 96, 987–997. [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Chacko, R.; Varughese, S. An Efficient Method of Recycling of CFRP Waste Using Peracetic Acid. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1564–1571. [CrossRef]

- Torkaman, N.F.; Bremser, W.; Wilhelm, R. Catalytic Recycling of Thermoset Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymers. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 7668–7682. [CrossRef]

- Sakai, A.; Kurniawan, W.; Kubouchi, M. Chemical Recycling of CFRP in an Environmentally Friendly Approach. Polymers 2024, 16, 143. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Oh, D.; Ju, Y.; Goh, M. Energy-Efficient Chemical Recycling of CFRP and Analysis of the Interfacial Shear Strength on Recovered Carbon Fiber. Waste Management 2024, 187, 134–144. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; An, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y. Environment-Friendly Recycling of CFRP Composites via Gentle Solvent System at Atmospheric Pressure. Composites Science and Technology 2022, 224, 109461. [CrossRef]

- Patre, R.; Rani, M.; Zafar, S. Insights into Environmental Sustainability of Microwave Assisted Chemical Recycling of CFRP Waste Using Life Cycle Assessment. Waste Management Bulletin 2025, 3, 100194. [CrossRef]

- Henry, L.; Schneller, A.; Doerfler, J.; Mueller, W.M.; Aymonier, C.; Horn, S. Semi-Continuous Flow Recycling Method for Carbon Fibre Reinforced Thermoset Polymers by near- and Supercritical Solvolysis. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2016, 133, 264–274. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Pickering, S.; Lester, E.; Turner, T.; Wong, K.; Warrior, N. Characterisation of Carbon Fibres Recycled from Carbon Fibre/Epoxy Resin Composites Using Supercritical n-Propanol. Composites Science and Technology 2009, 69, 192–198. [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Li, J.; Ding, J. Chemical Recycling of Carbon Fibre/Epoxy Composites in a Mixed Solution of Peroxide Hydrogen and N,N-Dimethylformamide. Composites Science and Technology 2013, 82, 54–59. [CrossRef]

- Pei, C.; Chen, P.; Kong, S.-C.; Wu, J.; Zhu, J.-H.; Xing, F. Recyclable Separation and Recovery of Carbon Fibers from CFRP Composites: Optimization and Mechanism. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, 278, 119591. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Lu, C.; Jing, D.; Chang, C.; Liu, N.; Hou, X. Recycling of Carbon Fibers in Epoxy Resin Composites Using Supercritical 1-Propanol. New Carbon Materials 2016, 31, 46–54. [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Yin, G.; Wada, M.; Kitaoka, S.; Wei, H.; Ohsawa, I.; Takahashi, J. INFLUENCE OF RECYCLING PROCESS ON THE TENSILE PROPERTY OF CARBON FIBER. 2017.

- Sokoli, H.U.; Beauson, J.; Simonsen, M.E.; Fraisse, A.; Brøndsted, P.; Søgaard, E.G. Optimized Process for Recovery of Glass- and Carbon Fibers with Retained Mechanical Properties by Means of near- and Supercritical Fluids. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2017, 124, 80–89. [CrossRef]

- Vogiantzi, C.; Tserpes, K. A Preliminary Investigation on a Water- and Acetone-Based Solvolysis Recycling Process for CFRPs. Materials 2024, 17, 1102. [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Varughese, S. A Novel Sonochemical Approach for Enhanced Recovery of Carbon Fiber from CFRP Waste Using Mild Acid–Peroxide Mixture. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 2080–2087. [CrossRef]

- Bruggeman, P.J.; Kushner, M.J.; Locke, B.R.; Gardeniers, J.G.E.; Graham, W.G.; Graves, D.B.; Hofman-Caris, R.C.H.M.; Maric, D.; Reid, J.P.; Ceriani, E.; et al. Plasma–Liquid Interactions: A Review and Roadmap. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2016, 25, 053002. [CrossRef]

- Marinis, D.; Farsari, E.; Alexandridou, C.; Amanatides, E.; Mataras, D. Chemical Recovery of Carbon Fibers from Composites via Plasma Assisted Solvolysis. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2024, 2692, 012017. [CrossRef]

- Marinis, D.; Farsari, E.; Amanatides, E. Dissolution Kinetics in Plasma-Enhanced Nitric Acid Solvolysis of CFRCs. Materials 2025, 18, 4242. [CrossRef]

- Δέσμη ανθρακονημάτων 3Κ, 1.80 kg, 5 km Available online: https://www.fibermax.eu/el-gr/anthrakoyfasmata/nimata/nimata-provoli-olon/desmi-anthrakonimaton-3k-1-kg-5-km.html (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- SR 1700 - System for Manufacturing Composite Structures. Sicomin.

- Marinis, D.; Markatos, D.; Farsari, E.; Amanatides, E.; Mataras, D.; Pantelakis, S. A Novel Plasma-Enhanced Solvolysis as Alternative for Recycling Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 2836. [CrossRef]

- C28 Committee ASTM International. Test Method for Tensile Strength and Youngs Modulus of Fibers. [CrossRef]

- Laurikainen, P.; Kakkonen, M.; Von Essen, M.; Tanhuanpää, O.; Kallio, P.; Sarlin, E. Identification and Compensation of Error Sources in the Microbond Test Utilising a Reliable High-Throughput Device. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2020, 137, 105988. [CrossRef]

- Borkar, A.; Hendlmeier, A.; Simon, Z.; Randall, J.D.; Stojcevski, F.; Henderson, L.C. A Comparison of Mechanical Properties of Recycled High-density Polyethylene/Waste Carbon Fiber via Injection Molding and 3D Printing. Polymer Composites 2022, 43, 2408–2418. [CrossRef]

- Rahimizadeh, A.; Tahir, M.; Fayazbakhsh, K.; Lessard, L. Tensile Properties and Interfacial Shear Strength of Recycled Fibers from Wind Turbine Waste. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2020, 131, 105786. [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Wada, M.; Ohsawa, I.; Kitaoka, S.; Takahashi, J. Influence of Treatment with Superheated Steam on Tensile Properties of Carbon Fiber. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2018, 107, 555–560. [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Yim, Y.-J.; Bae, J.-S.; Seo, M.-K. Interfacial Interlocking of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites: A Short Review. Polymers 2025, 17, 267. [CrossRef]

- Sakai, A.; Kurniawan, W.; Kubouchi, M. Recycled Carbon Fibers with Improved Physical Properties Recovered from CFRP by Nitric Acid. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 3957. [CrossRef]

| Tensile properties | Units | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Modulus of elasticity | MPa | 3400 |

| Maximum resistance | MPa | 90 |

| Resistance at break | MPa | 87 |

| Elongation at maximum resistance | % | 4.2 |

| Elongation at break | % | 5.1 |

| Sample ID | Solvolysis Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma heads | Plasma Power input (W) | Plasma Gas Mixture | Flow (L/min) | HNO3 Concentration (M) | Composite/HNO3 ratio (g/mol) | Time (h) | |

| Set 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Set 2 | 1 | 800 | N2 | 4 | 14.4 | 2 | 5.5 |

| Set 3 | 1 | 800 | N2 | 4 | 14.4 | 2.1 | 4.5 |

| Set 4 | 1 | 800 | N2 | 4 | 14.4 | 4.4 | 4.3 |

| Set 5 | 1 | 800 | N2 | 4 | 14.4 | 6.2 | 5.2 |

| Set 6 | 1 | 800 | N2 | 4 | 14.4 | 9.4 | 5.3 |

| Set 7 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 14.4 | 2.1 | 18 |

| Set 8 | 4 | 1680 | N2/Ar | 1/3 | 14.4 | 2.2 | 4.1 |

| Set 9 | 4 | 1680 | N2/Ar | 1/3 | 12 | 2.7 | 4.5 |

| Set 10 | 4 | 1680 | N2/Ar | 1/3 | 10 | 3.3 | 6 |

| Set 11 | 4 | 1680 | N2/Ar | 1/3 | 8 | 4 | 6 |

| Set 12 | 4 | 1200 | N2/Ar | 1/4 | 14.4 | 1.9 | 6 |

| Set 13 | 4 | 460 | N2/Ar | 1/4 | 14.4 | 1.9 | 6 |

| Set 14 | 4 | 800 | N2/Ar | 1/4 | 14.4 | 1.9 | 6 |

| Set 15 | 4 | 1200 | N2/Ar | 1/4 | 14.4 | 1.9 | 6 |

| Set 16 | 4 | 800 | N2/Ar | 1/4 | 12 | 2.3 | 6 |

| Set 17 | 4 | 1200 | N2/Ar | 1/4 | 12 | 2.3 | 6 |

| Set 18 | 4 | 1600 | N2/Ar | 1/4 | 12 | 2.3 | 6 |

| Set 19 | 4 | 800 | N2/Ar | 1/4 | 10 | 2.7 | 6 |

| Set 20 | 4 | 1200 | N2/Ar | 1/4 | 10 | 2.7 | 6 |

| Set 21 | 4 | 1600 | N2/Ar | 1/4 | 10 | 2.7 | 6 |

| Fiber Type | Set | Shape factor | Scale factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3K fiber tow | Virgin | 4.83 | 2795.64 |

| Set 6 | 3.06 | 3021.74 | |

| Set 8 | 1.83 | 3654.35 | |

| Set 11 | 3.39 | 2137.65 | |

| Set 12 | 4.59 | 3100.18 | |

| Set 13 | 4.32 | 2899.29 | |

| Set 16 | 5.74 | 4442.42 | |

| Set 19 | 4.79 | 3442.83 | |

| 24K fiber tow | Virgin | 3.73 | 2920.94 |

| Set 2 | 3.24 | 2805.79 | |

| Set 3 | 3.08 | 3960.58 | |

| Set 4 | 3.43 | 2494.89 | |

| Set 5 | 2.50 | 3050.85 | |

| Set 7 | 3.95 | 3453.69 | |

| Set 9 | 3.57 | 2656.16 | |

| Set 10 | 2.99 | 3141.17 | |

| Set 14 | 4.16 | 3736.71 | |

| Set 15 | 2.87 | 3635.88 | |

| Set 17 | 3.22 | 3857.46 | |

| Set 18 | 2.97 | 4022.52 | |

| Set 20 | 5.47 | 3565.86 | |

| Set 21 | 4.14 | 3832.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).