1. Introduction

Recent years have seen a sharp increase in demand for eco-friendly and sustainable materials due to worries about resource depletion, climate change, and environmental deterioration. High strength and durability are provided by conventional composite materials, which are frequently reinforced with synthetic fibers like carbon and glass. They do have a price, though, as they have detrimental effects on the environment, limited biodegradability, and high production energy usage. In order to provide a workable substitute with smaller environmental impacts, research has shifted its attention to creating "green" composites, which make use of natural fibers and biodegradable or bio-based matrices.

Because of their quantity and special qualities, coir fibers have garnered attention among the several types of natural fibers that are accessible. A ligno cellulose fiber made from coconut husks, coir is prized for its high lignin content, exceptional resilience, and inherent resistance to rot, dampness, and fungal invasions. Coir fibers are a viable option for reinforcement in composites because of these qualities. Coir fibers do have certain drawbacks, though, such as comparatively high stiffness and poorer mechanical qualities when compared to other natural fibers like flax or jute. In order to overcome these obstacles, scientists have looked for ways to enhance coir's ability to connect and perform better overall in composite matrices.

The creation of coir-reinforced composites in this context entails improving the fiber's interfacial bonding with the matrix by applying different treatments and adding additives. A popular method is fiber mercerization, which involves treating coir fibers with dried under sun light to enhance surface roughness and boost bonding strength. Cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL) and liquid rubber are added to the composite matrix to increase the strength and endurance of the material. By acting as toughening agents and binders, these ingredients make the material stronger and more durable.

Coir matting and the epoxy-hardener mixture are alternately positioned and squeezed to create a multi-layered structure during the construction process for these composites. Better cohesion between the coir layers and matrix is ensured by the application of CNSL and liquid rubber, which improves mechanical qualities. When compared to their untreated counterparts, the resultant coir reinforced composites have better tensile strength, flexural modulus, and impact resistance, which makes them appropriate for a variety of uses. Possible applications include furniture, packaging, construction materials, and automobile parts, where strength, durability, and sustainability are desired qualities.

In this work, treated coir matting and epoxy-hardener mixes with CNSL are layered one after the other, and compression molding is used to create coir-reinforced composites. Analyzing how these treatments affect the composite's mechanical performance under tensile loading and other circumstances is the goal. The objective of this research is to promote environmentally appropriate alternatives for a variety of businesses by integrating natural fibers with cutting-edge treatment techniques.

The coir fibers are dried for a predetermined amount of time and at a regulated concentration as part of the procedure. In addition to improving the fiber-matrix interaction, this technique alters the fiber's internal structure, raising the degree of cellulose crystallinity and decreasing the fiber's capacity to absorb moisture. As a result, dried coir fibers with have higher tensile strength and stiffness, which makes them more appropriate for structural uses. The treated coir fibers are transformed into mats that act as reinforcement layers in the creation of coir-reinforced composites. In order to create the composite, a hardener is combined with a matrix material, usually epoxy resin, in a precise ratio (in this example, 1:1.25).

Cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL) and liquid rubber are added to the matrix to improve the composite's qualities even more. The cashew industry produces CNSL, a phenolic chemical that is well-known for its binding capabilities and capacity to increase the toughness of polymer matrices. Conversely, liquid rubber serves as a toughening agent, enhancing the composite's elasticity and resistance to impact. When combined, these additives form a matrix that can efficiently disperse stress and enhance the final composite material's overall mechanical qualities.

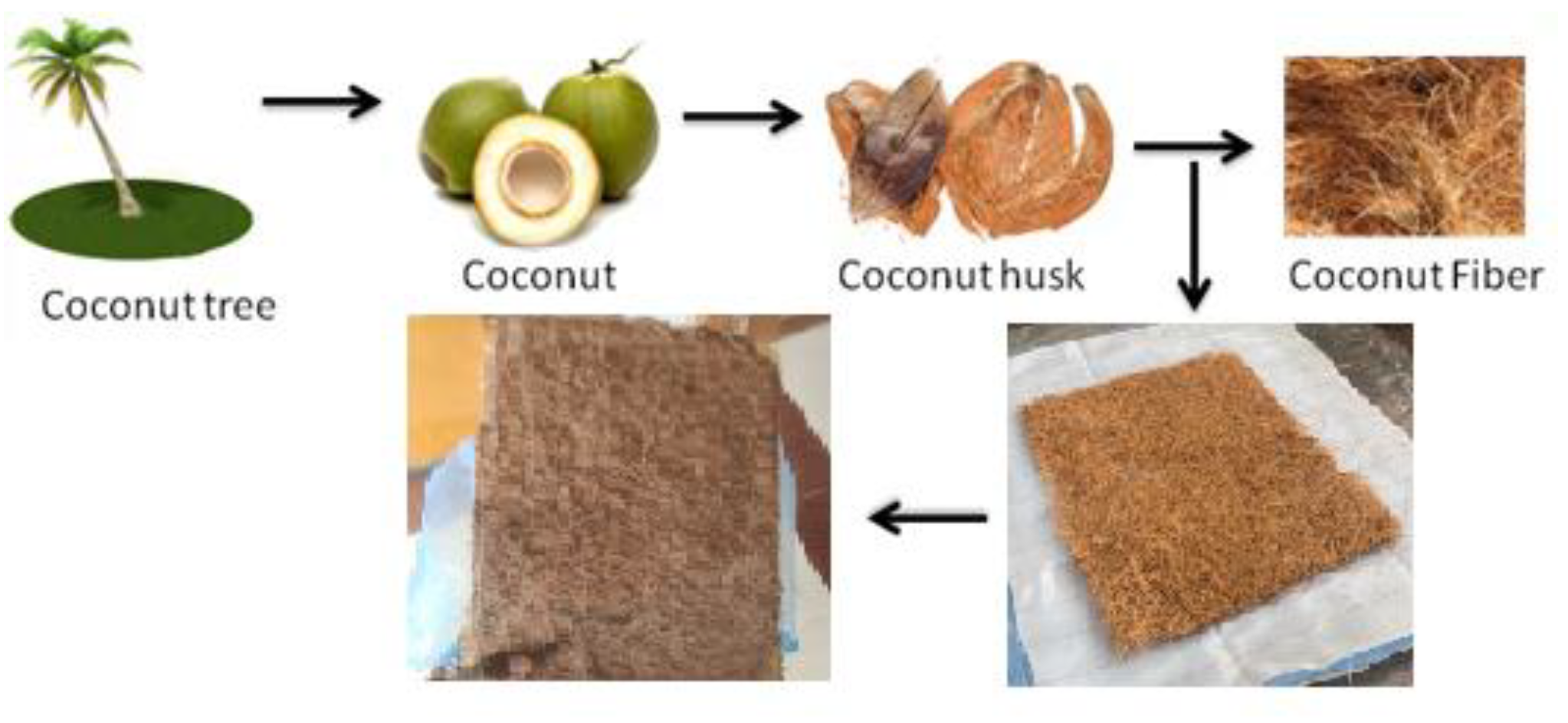

Figure 1.

Composite material.

Figure 1.

Composite material.

A methodical layering procedure utilizing dried coir mats and an epoxy-hardener matrix modified with cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL) and liquid rubber is used to create coir-reinforced composite material, this method guarantees improved mechanical qualities and environmental advantages.

A compression molding technique is used to create the composite. The coir fibers are first prepared by dried under sun light to increase their mechanical integrity and stickiness. The epoxy-hardener mixture is then placed alternately with the treated fibers in the mold to create mats. 20% CNSL is added as an additive to the epoxy-hardener system, which is carefully blended at a 1:1.25 ratio to improve toughness and durability. To guarantee consistent impregnation and bonding, the resin is meticulously injected into each layer of coir mat. Following the placement of each layer, the multilayered structure is compressed using regulated pressure to create a cohesive, dense composite with few voids.

The composite is made using a compression molding process. In order to improve the mechanical integrity and stickiness of the coir fibers, they are first dried under sunlight. After that, the dried fibers and epoxy-hardener mixture are alternately inserted into the mold to form mats. To increase toughness and durability, 20% CNSL is added as an additive to the epoxy-hardener system, which is meticulously mixed at a 1:1.25 ratio. The resin is carefully injected into every layer of coir mat to ensure uniform impregnation and bonding. After each layer is positioned, the multilayered structure is compressed with controlled pressure to produce a dense, cohesive composite with few voids.

2. Objective

Developing and evaluating a coir fiber-reinforced composite material with Cashew Nut Shell Liquid (CNSL) as an additive to improve its mechanical and thermal properties is the main goal of this research. Through fiber treatment and resin optimization, this study seeks to: • Improve Mechanical Properties: Increase tensile, flexural, and impact strength.

Examine the effectiveness of CNSL by determining how it enhances bonding and thermal stability.

• Optimize Mercerization Treatment: Examine how fiber-matrix adhesion is affected on sun dried fiber.

• Perform Mechanical and Thermal Testing: To assess structural integrity, chemical composition, and heat resistance, conduct tensile testing, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and thermal analysis.

Objectives Encourage sustainability by creating an environmentally friendly composite material that may find use in industry.

3. Methodology

In order to assess the effects of fiber treatment, CNSL addition, and fiber structure, this section describes how to prepare and characterize composite specimens.

Figure 2.

The process of treating coconut husk into fiber and composite material.

Figure 2.

The process of treating coconut husk into fiber and composite material.

3.1. Specimen Details

The composite specimens were prepared and analyzed:

Coir Fiber Composite - Coir fibers dried under sunlight to improve fiber-matrix adhesion.

Specimen were underwent fabrication, testing, and analysis to compare its mechanical strength, thermal stability, and chemical composition.

3.2. Sample Preparation

3.2.1. Composite Fabrication

Specimens were fabricated using the vacuum bagging method to ensure uniform resin impregnation and fiber wetting and one was made using compression mould.

Sun driedSpecimens:

• Coir fiber mats were layered with the epoxy-hardener mixture (1:1.25 ratio) with 20% CNSL added.

• The composite was vacuum-sealed using a 1-stage vacuum pump (ATV 118) and cured at room temperature.

• The compression Mould technique was used to enhance resin penetration and minimize voids.

3.3. Testing and Characterization

Each composite specimen was subjected to mechanical, chemical, and thermal analysis to determine how fiber treatment, CNSL addition, and sun-dried coir structure affect performance.

4. Mechanical Testing

4.1. Tensile Strength Test

Assessing the coir fiber reinforced composite's strength and stiffness under tensile stress was the aim of the tensile test. A Standard Universal Testing Machine (UTM) was used for the test, guaranteeing accurate and consistent measurements. Because the elimination of lignin and hemicellulose improved fiber-matrix adhesion, it was anticipated that the dried composite would have a better tensile strength. Furthermore, because of improved load distribution and improved fiber bonding, which aids in preventing deformation under applied stress, it was expected that the sun-dried fiber composite would exhibit superior tensile qualities.

4.2. Flexural Strength Test

Determining the composite's structural stiffness and assessing its resistance to bending forces were the goals of the flexural test. To ensure precise measurement of the material's resistance to bending stress, the test was carried out on a flexural testing equipment with a three-point bending configuration. Sun dried fiber composite was predicted to have the highest flexural strength. This is because composite's fiber network improves load distribution and delays premature breakdown under bending stress.

4.3. Impact Strength Test

Assessing the composite's capacity to absorb and release energy under abrupt loading circumstances was the aim of the impact test. A standardized impact testing apparatus was used for the test, guaranteeing an accurate assessment of the material's toughness. Since the sun-dried fiber composite's organized fiber arrangement improves energy dissipation and resistance to abrupt forces, it was anticipated that it would have the maximum impact strength. However, because of their unstructured fiber alignment, which may result in inefficient energy absorption and a higher risk of brittle failure, the sun dried fiber composites were expected to have lower impact resistance.

4.4. Chemical Analysis.

4.4.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Finding chemical changes in coir fibers and assessing resin-fiber interactions in the composite were the goals of the FTIR investigation. By identifying the material's functional groups, this method sheds light on modifications brought about by fiber arrangement and sun dried fiber composite material. In order to verify the effective elimination of surface contaminants and enhanced fiber reactivity, it was anticipated that the composite would show diminished peaks corresponding to lignin and hemicellulose. Furthermore, the structured fiber arrangement of the sun-dried fiber composite may affect the epoxy resin's penetration and distribution, which could alter the material's overall chemical interactions and result in unique resin-fiber bonding properties.

4.5. Microstructural Analysis.

4.5.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Observing fiber-matrix bonding and assessing the microstructural integrity of the coir fiber-reinforced composite were the goals of the SEM investigation. The internal structure of the composite, including void development, fiber pull-out, and adhesion quality, is revealed by this examination. Poor adhesion, with evident fiber pull-out and gaps at the fiber-matrix interface, suggesting weak bonding, was anticipated for the untreated composite. However, since the removal of lignin and hemicellulose results in a rougher fiber surface that improves mechanical bonding, it was expected that the sun dried fiber composite material would exhibit better fiber-matrix interaction. Furthermore, it was anticipated that the sun-dried coir composite would exhibit tightly packed fibers with few vacancies, enhancing the material's mechanical performance and load transfer.

4.6. Thermal Analysis.

4.6.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

The purpose of the TGA analysis was to evaluate the composite's heat stability and degradation behavior. Because hemicellulose and lignin were eliminated, it was anticipated that sun dried composites would exhibit greater heat stability than untreated samples. Since the sun-dried composite's organized fiber arrangement improves stability and slows degradation, it was expected to offer superior heat resistance.

5. Development of Coconut Fibre Impregnated Composite Material

5.1. Materials and Methods

Araldite AW106 epoxy resin combined with CNSL at 15 weight percent and 20 weight percent concentrations was used to create bio-based epoxy matrices for the composite specimens. In order to improve flexibility, impact strength, and thermal resistance while advancing environmental sustainability, CNSL was added as a reactive bio-based addition.

For composite applications, the epoxy-CNSL blends were mixed with HV 953 hardener at a 1:1.25 hardener to resin ratio to guarantee ideal curing, striking a balance between mechanical strength and flexibility. The composite specimens were then created using these matrices:

Random sun dried coir fiber composite – Processed using vacuum bagging.

5.2. Coir Fiber Preparation and Treatment

Before being fabricated, coir fibers, which serve as reinforcement in the composite, go through many cleaning and preparation steps:

Cleaning Procedure: To get rid of dust, debris, and undesirable surface contaminants, fibers are thoroughly cleaned with distilled water. This removes any bonding obstacles, improving fiber-matrix adhesion.

Drying: To guarantee sufficient moisture removal, which is essential for successful resin impregnation, washed fibers are sun-dried for 24 to 48 hours.

Mercerization Treatment: To chemically alter their surface, a subset of fibers are sun dried fiber composite material. The fiber surface is roughened, lignin and hemicellulose are eliminated, cellulose exposure is increased, and interfacial bonding with the epoxy matrix is enhanced. Post-Treatment Neutralization: Before being used to create composites, mercerized fibers are thoroughly rinsed with distilled water to get rid of extra alkali and allowed to dry outdoors.

5.3. Composite Fabrication Process:

Three different coir-based composite specimens were fabricated using vacuum bagging for sun dried specimens, and compression molding for the sun-dried specimen:

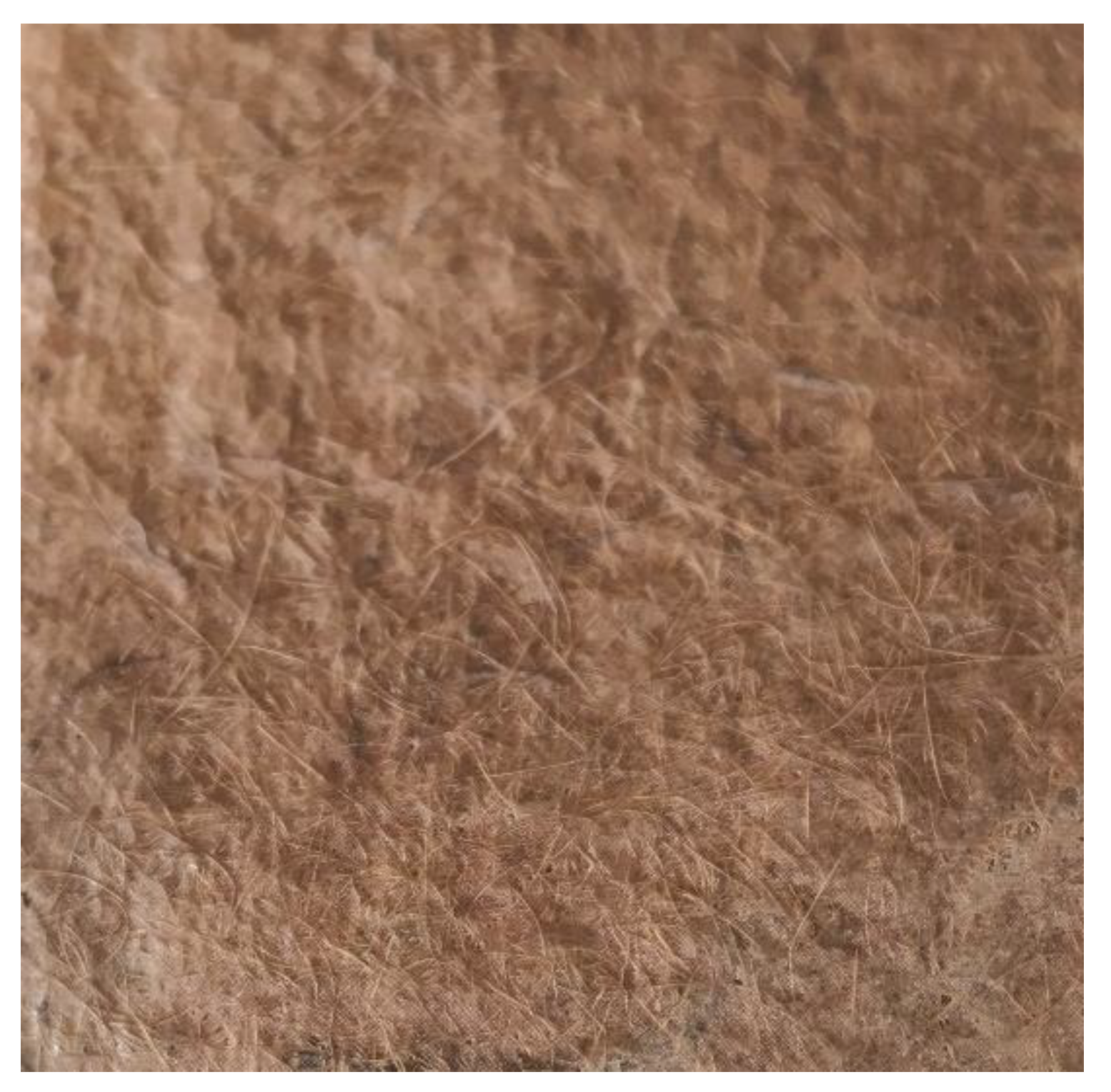

Figure 3.

Sun dried coir composite material.

Figure 3.

Sun dried coir composite material.

Randomly Arranged Coir Fiber Composite (sun dried– Vacuum Bagging):

Coir fibers were distributed in a random, non-woven fashion inside the mold. The CNSL epoxy resin was applied, ensuring fiber saturation. The vacuum bagging process was used to remove excess air and promote resin infiltration. The composite was cured under vacuum to achieve optimal polymerization.

COMPOSITION OF MATERIALS USED:

Table 1.

Composition of Materials Used.

Table 1.

Composition of Materials Used.

| Sample No |

Fiber Type |

Fiber Tretment |

Fiber Arrangement |

Fiber Weight(g) |

Epoxy Resin(g) |

CNSL(g) |

Hardener(g) |

Total Weight(g) |

| Treated coir |

Coir Fiber |

NA-OH Treated |

Random |

70 |

250 |

37.5 |

230 |

587.5 |

5.4. Vacuum Bagging Process:

• Fiber Preparation: The fibers were cleaned and placed on the top of vaccum bagging sheets.

• Layering: Coir fiber mats and CNSL-epoxy resin were alternately layered inside the mold.

• Bagging: A vacuum bag was placed over the fibers, and air was removed using a vacuum pump (ATV 118).

• Pressure Application:The vacuum pressure ensured resin penetration into fibers, reducing void formation.

• Curing: The composite was left under vacuum for a specified curing time to complete polymerization.

• Demolding: After curing, the composite was removed, and post-curing analysis was conducted.

Figure 4.

Placement of coir fiber mat on the peel ply sheet.

Figure 4.

Placement of coir fiber mat on the peel ply sheet.

Figure 5.

Application of resin (Epoxy+CNSL) onto the coir fiber mat.

Figure 5.

Application of resin (Epoxy+CNSL) onto the coir fiber mat.

Figure 6.

Placement of next coir fiber mat.

Figure 6.

Placement of next coir fiber mat.

Figure 7.

Placement of peel ply fabric over the resin -impregnated fiber mat.

Figure 7.

Placement of peel ply fabric over the resin -impregnated fiber mat.

Figure 8.

Placement of knitted infusion mesh to allow proper air evacuation.

Figure 8.

Placement of knitted infusion mesh to allow proper air evacuation.

Figure 9.

Vacuum bagging setup being sealed for the process.

Figure 9.

Vacuum bagging setup being sealed for the process.

Figure 10.

Application of vacuum to remove excess air and compress layers.

Figure 10.

Application of vacuum to remove excess air and compress layers.

Figure 11.

Final Vacuum-sealed setup ensuring proper resin infiltration and curing.

Figure 11.

Final Vacuum-sealed setup ensuring proper resin infiltration and curing.

5.4.1. Controlled Curing Conditions

• Temperature & Pressure Control: Curing was conducted under room temperature (avg 23-28°C) and pressure conditions, ensuring complete polymerization.

• Resin Infiltration Optimization: Uniform pressure across the mold eliminated air voids and ensured dense composite formation.

5.4.2. Importance of Curing Time

• Shorter curing times lead to incomplete polymerization, weakening the composite.

• Excessive curing causes thermal stress, affecting durability.

• Optimized curing conditions provide the best balance of mechanical performance

6. Testings

Importance of Mechanical and Thermal Testing in Coir Fiber-Reinforced Composites

Mechanical and thermal testing are crucial for determining the strength, longevity, and suitability of coir fiber-reinforced composites for real-world uses. These experiments help evaluate the effects of fiber treatment, CNSL composition, and fabrication techniques on composite performance. Below is a description of the importance of each exam.

6.1. Importance of Tensile Testing (ASTM D3039)

Tensile testing determines how much stress a material can bear before breaking when stretched. Because fiber-reinforced composites are used in load-bearing applications, this is very crucial.

Determines Strength in Tensile: Assessing the composite's resistance to pulling forces is crucial for applications involving structural loads.Fiber Treatment's Effect: explains how applying sun dried enhances fiber matrix adherence, which raises tensile strength.

The Effect of CNSL on Resin Behavior Since CNSL-modified epoxy increases flexibility, tensile testing helps determine if a higher CNSL concentration improves or detracts from tensile performance.

Predicting Structural Reliability: Ensures that the composite can withstand expected operational stresses in automotive, aerospace, and construction applications.and material stability.

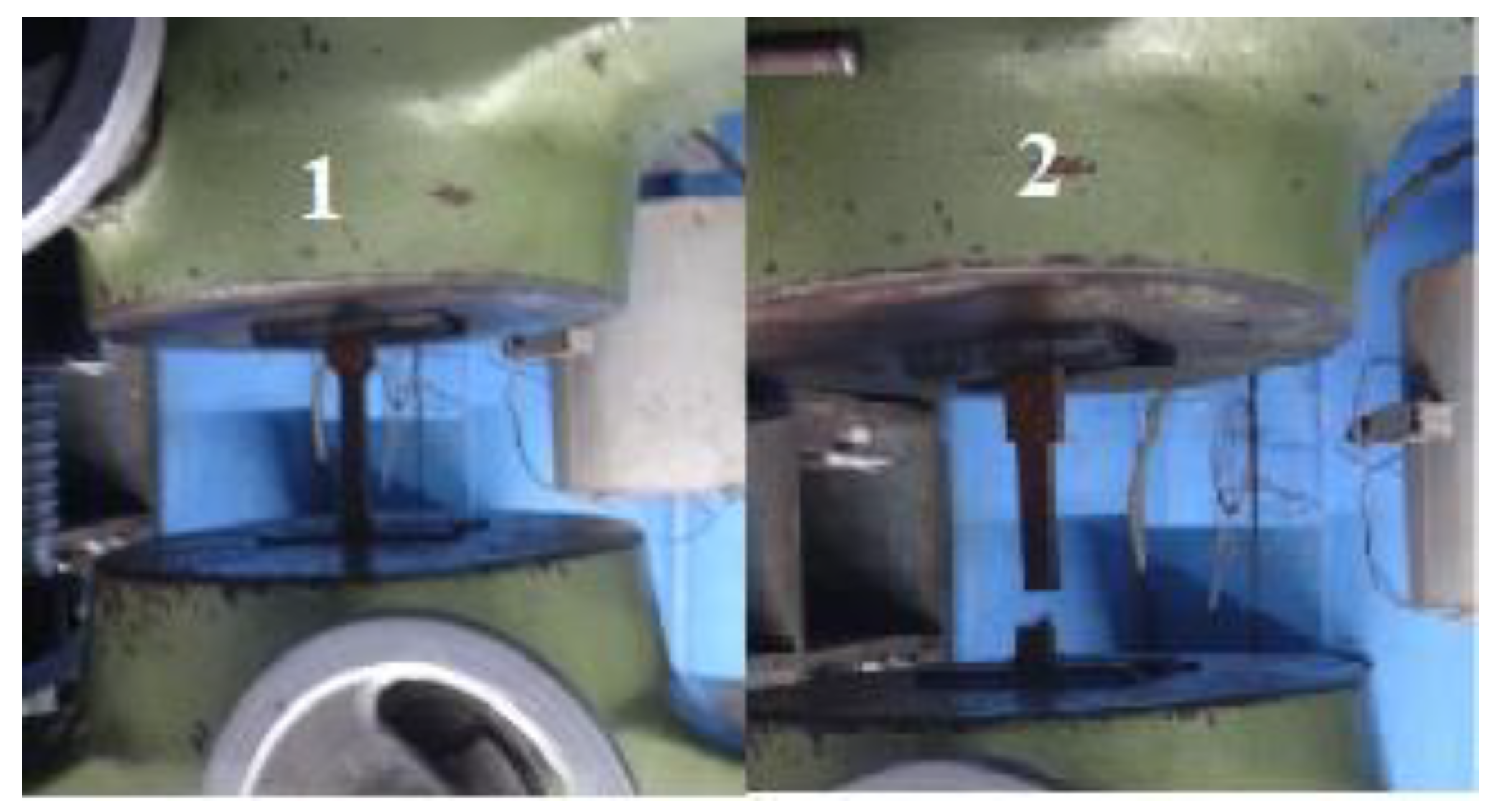

Figure 12.

Tensile Testing, 1.Before applying tensile load and 2. After applying load.

Figure 12.

Tensile Testing, 1.Before applying tensile load and 2. After applying load.

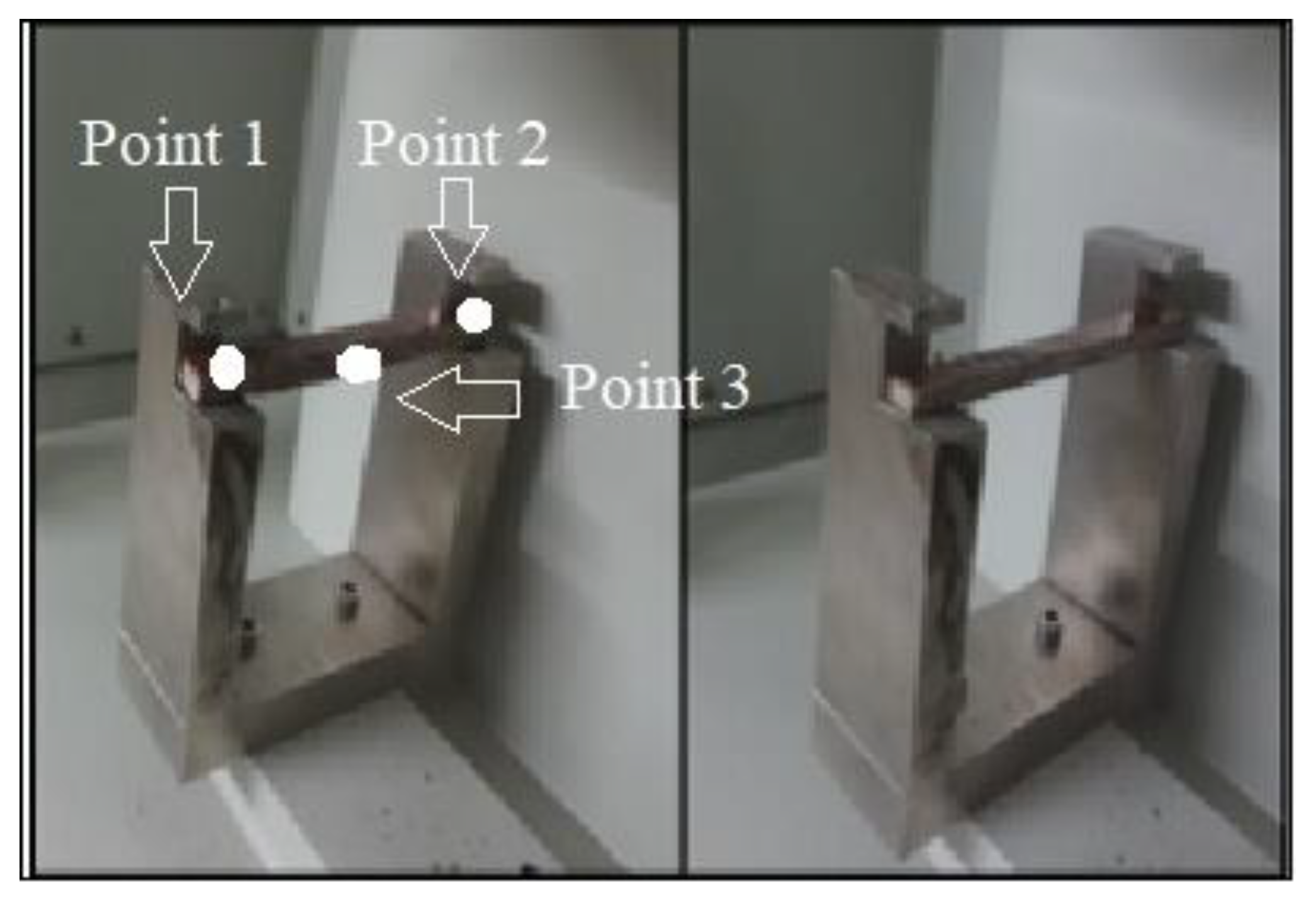

6.2. Importance of Flexural Testing (ASTM D7264)

Flexural testing determines the stiffness and bending resistance of the composite material by applying a force at the center while the material is supported at both ends (Three-Point Bending Test).

• Evaluates Composite Rigidity: Measures the flexural modulus, which indicates how much the material bends under load.

• Importance in Structural Components: Essential for materials used in beams, panels, and furniture, where bending resistance is crucial.

• Fiber-Matrix Adhesion Assessment: A strong fiber-matrix bond increases The material's resistance to deformation. Poor bonding leads to premature failure.

• Effect of sun-dried Fiber Arrangements:

Figure 13.

Flexural Testing, This corresponds to the three-point bending test used to evaluate the flexural strength.

Figure 13.

Flexural Testing, This corresponds to the three-point bending test used to evaluate the flexural strength.

Figure 14.

Impact Testing. The impact strength test is used to ascertain how well the composite material absorbs energy when subjected to abrupt loads.

Figure 14.

Impact Testing. The impact strength test is used to ascertain how well the composite material absorbs energy when subjected to abrupt loads.

Impact testing evaluates the composite's capacity to absorb energy under abrupt loads, like falls or crashes.

Determines Toughness and Brittleness: Essential for predicting how the composite will perform under accidental impacts.

• Effect of CNSL on Impact Resistance: Since CNSL increases flexibility and energy absorption, impact testing helps assess how CNSL-modified composites compare to conventional epoxy composites.

• Applications in Safety-Critical Areas: Important for helmets, crash-resistant materials, and protective enclosures.

• Influence of Fiber Arrangement: sun-dried fiber composites are expected to exhibit better energy absorption arranged composites.

6.3. Importance of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

FTIR spectroscopy helps in understanding the interactions between fiber and resin, particularly after treatment with sun dried fiber material and CNSL modification.

• Confirms Functional Group Changes: Determines whether sun dried fiber material treatment successfully removed lignin and hemicellulose , making the fiber more reactive.

• Identifies Chemical Bonds in CNSL-Epoxy Composites: Ensures that CNSL is well incorporated into the resin without causing degradation.

• Predicts Long-Term Durability: Identifies potential chemical weaknesses that could lead to failure over time.

6.4. Importance of Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

The Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) technique is used to evaluate the thermal stability and decomposition behaviour of the coir fiber-reinforced composite. It helps determine how the material responds to heat, making it essential for assessing its durability in high temperature applications.

Key Applications in Composite Analysis:

• Evaluates Heat Resistance: Determines the onset degradation temperature, indicating when the composite starts to break down.

• Effect of CNSL on Thermal Properties: Since CNSL can enhance heat resistance, TGA verifies whether CNSL-modified epoxy composites exhibit improved thermal stability.

• Applications in High-Temperature Environments: Ensures the composite’s suitability for aerospace, automotive, and industrial applications, where materials must withstand extreme heat.

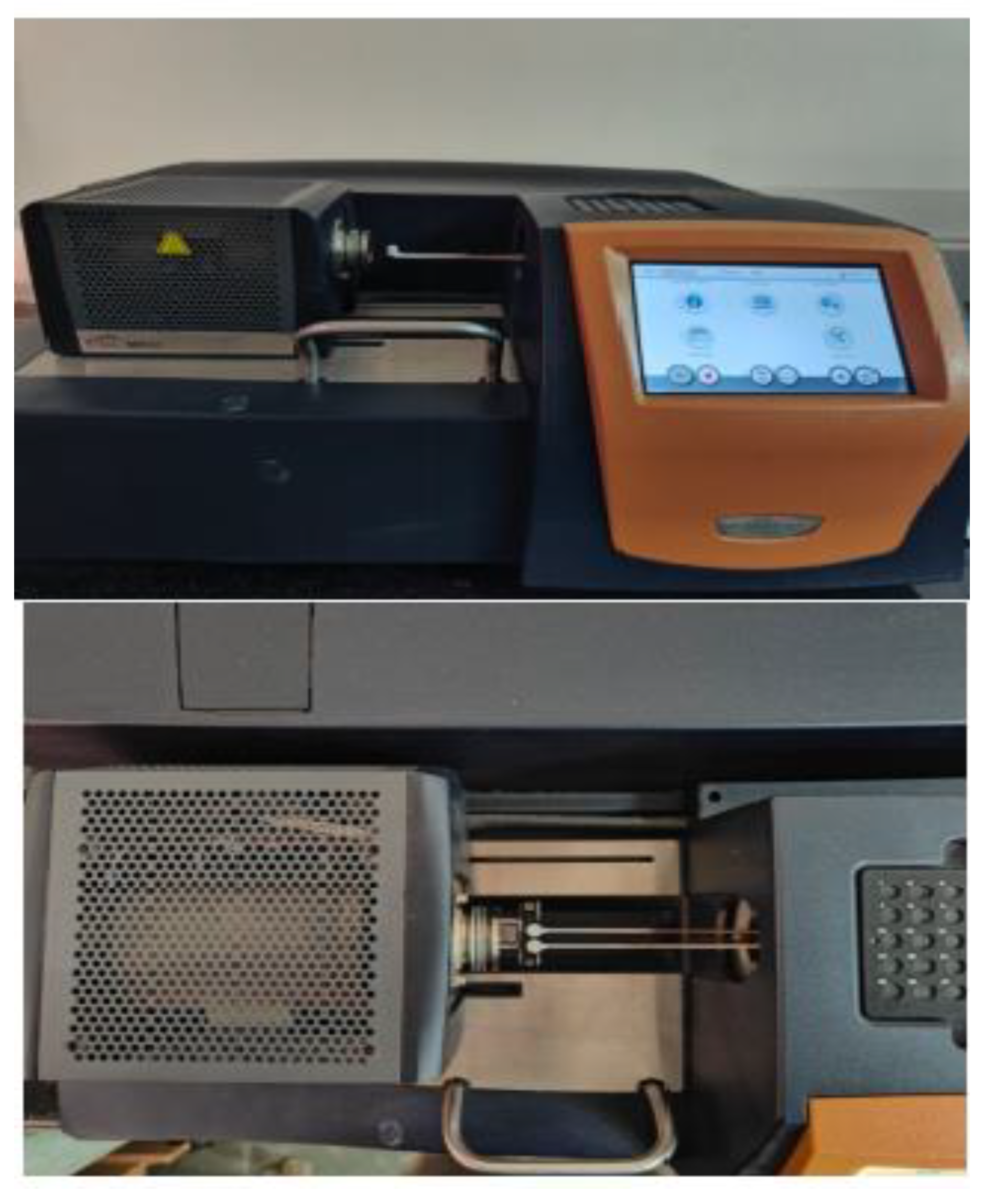

Machine Used: TA SDT 650 TGA-DSC Analyzer

• Temperature Range: Ambient to 800°C, enabling analysis of decomposition behaviour at different heat levels.

• Heating Rate: Adjustable from 0.1 to 100°C/min, allowing controlled heating for precise thermal studies.

According to metal standards, the calorimetric accuracy is ±2%, guaranteeing high-precision findings.

Figure 15.

Thermogravimetric Analyser (TGA)Setup.

Figure 15.

Thermogravimetric Analyser (TGA)Setup.

Sample Weight Capacity: Up to 200 mg, making it ideal for small-scale composite analysis.

Vacuum Capability: Operates under 50 μTorr, reducing oxidation effects and improving accuracy.

Weighing Accuracy: ±0.5%, ensuring precise measurement of weight loss during decomposition.

The TA SDT 650 TGA-DSC Analyzer provides detailed insights into the thermal stability and behaviour of the composite, confirming its performance in real-world high-temperature conditions.

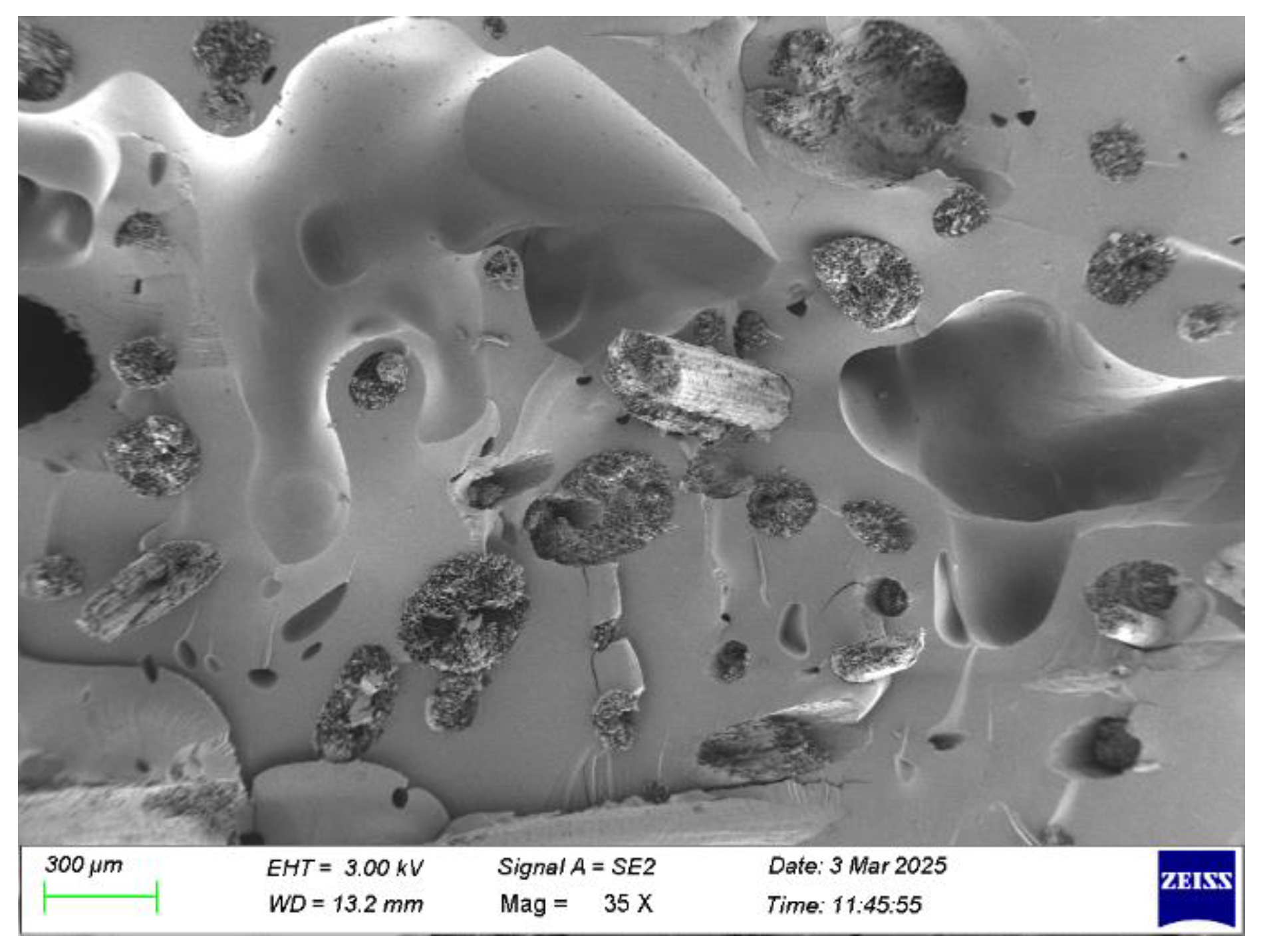

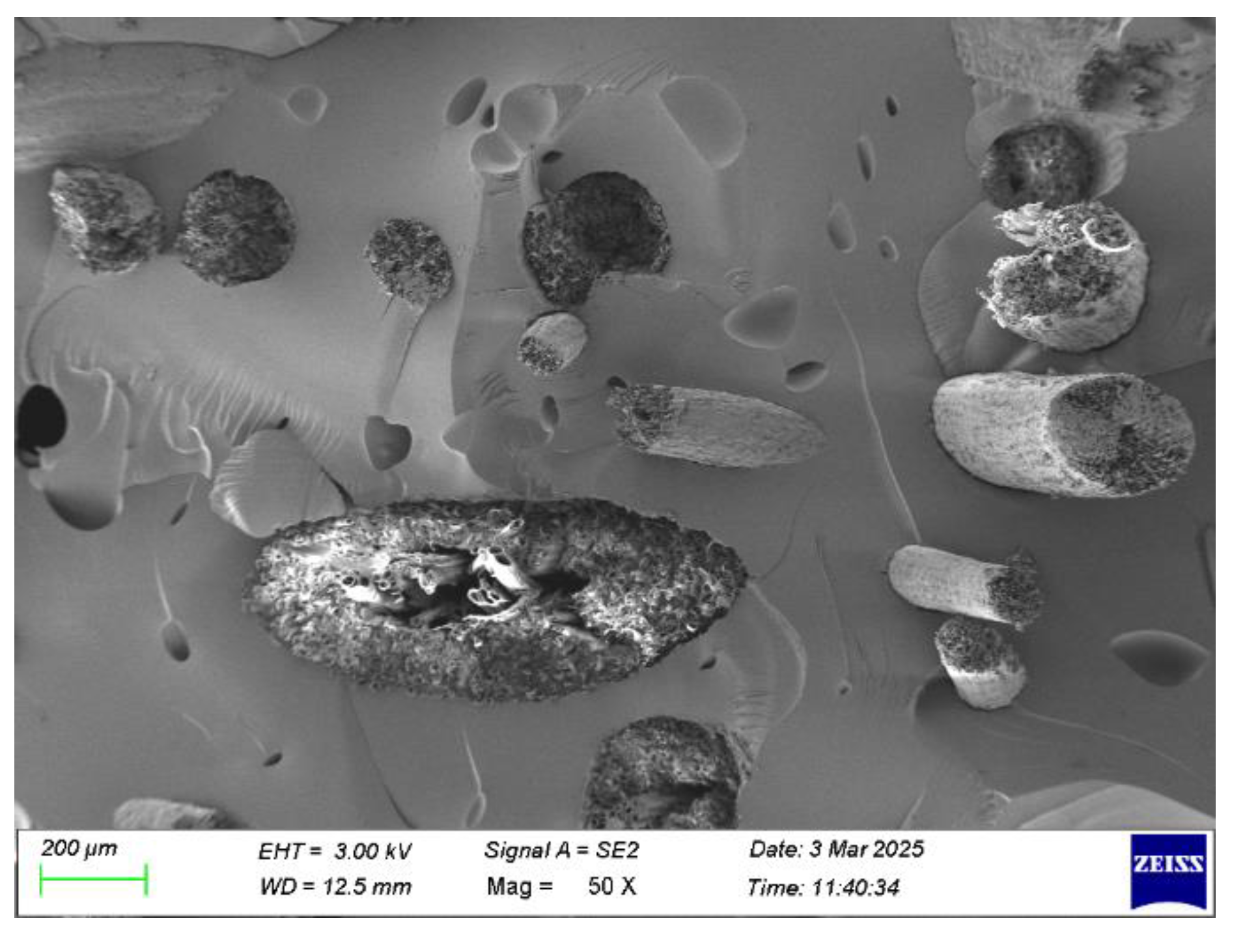

6.5. Importance of Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

The Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) is a crucial tool for analysing the fiber-matrix bonding and failure mechanisms in the composite. It provides high-resolution imaging that reveals microscopic surface structures, defects, and interfacial adhesion.

Key Applications in Composite Analysis:

• Observes Fiber Pull-Out and Void Formation: Assesses whether sun dried fiber composite material treatment improved fiber-matrix adhesion by reducing fiber debonding.

• Confirms Uniform Resin Distribution: Ensures that vacuum bagging and compression molding successfully minimized void content, leading to enhanced mechanical properties.

• Predicts Mechanical Failure Modes: Identifies whether failure occurs due to fiber breakage, delamination, or matrix cracking, helping in material optimization.

Supports Quality Control: Ensures consistent composite performance by analyzing surface and cross-sectional morphology, detecting defects that could affect durability.

Machine Used: Zeiss Sigma SEM

• Electron Source: Schottky thermal field emitter for high-resolution imaging.

• Accelerating Voltage Range: 0.2 to 30 kV, adjustable for different material types.

• Detectors: Includes in-lens secondary electron, backscattered electron, and variable pressure detectors for comprehensive imaging.

• Resolution: 2.8 nm at 1 kV, 1.5 nm at 15 kV, providing fine structural details.

Figure 16.

Scanning Electron Microscope(SEM).

Figure 16.

Scanning Electron Microscope(SEM).

7. Results & Discussion

TEST RESULTS OF TENSILE, FLEXURAL AND CHARPY IMPACT STRENGTH OF THE SPECIMENS

Figure 17.

Tested composite material.

Figure 17.

Tested composite material.

Detailed Discussion of Findings

The experimental findings offer a thorough comprehension of how CNSL alteration, fiber arrangement, and chemical treatment affect the mechanical and thermal characteristics of composites reinforced with coir fibers.

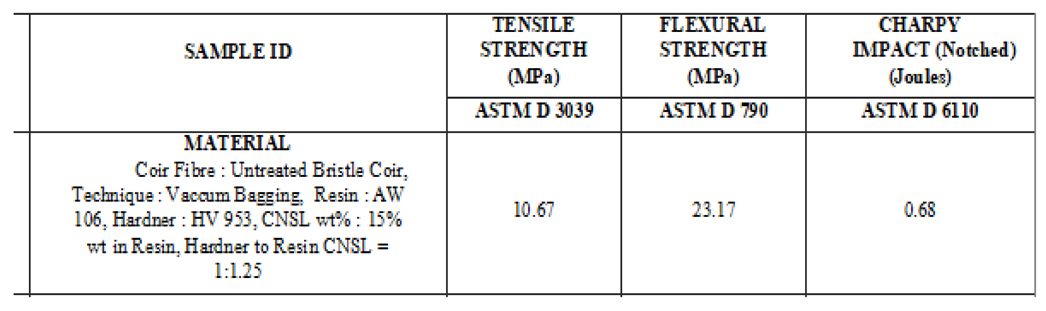

Table 2.

Test results of tensile, flexural and impact strength of the specimen.

Table 2.

Test results of tensile, flexural and impact strength of the specimen.

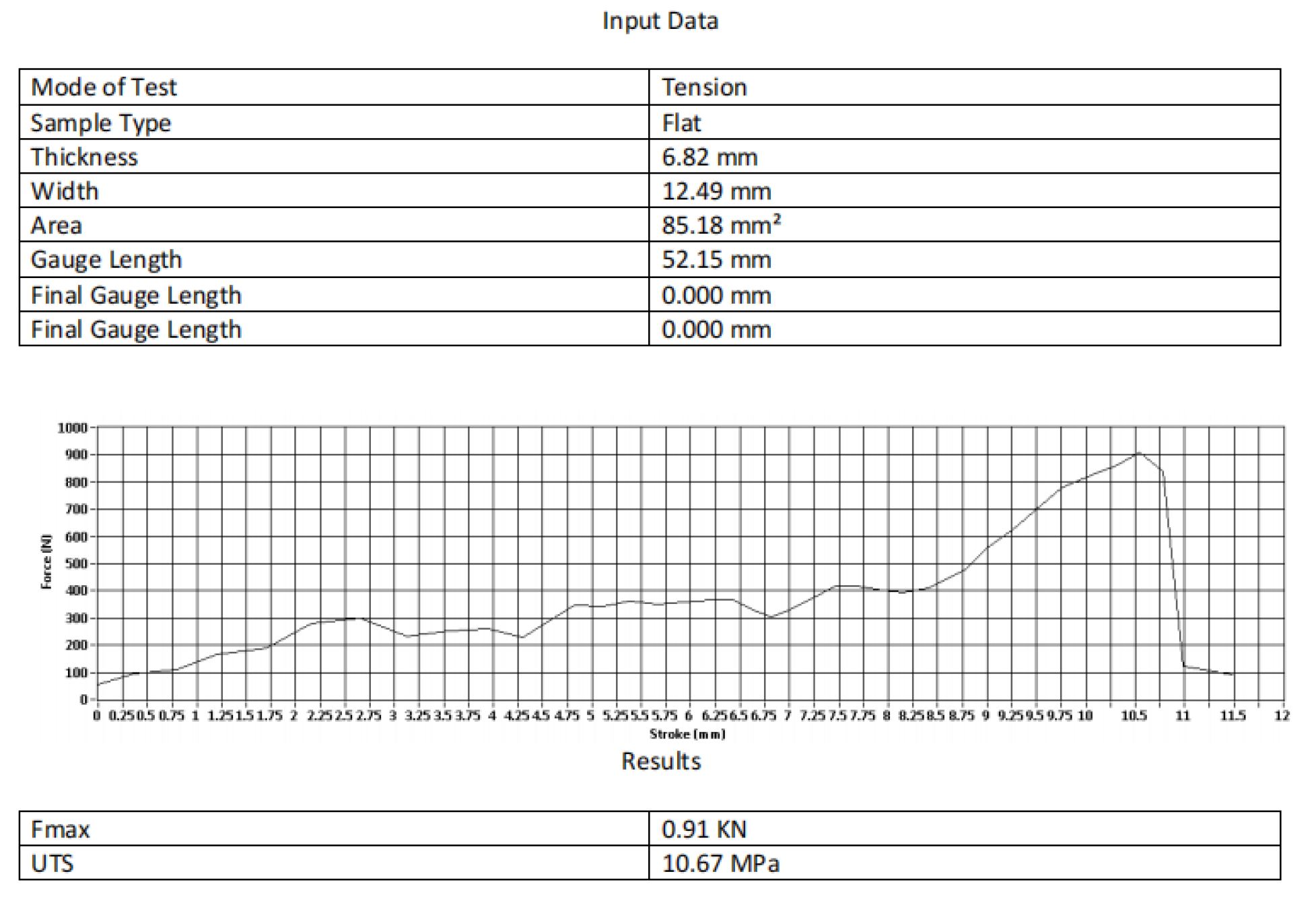

7.1. Tensile Strength

• Sun dried random fiber composites recorded a tensile strength of 10.67 MPa. This shows better arranged fibers do provide uniform load distribution, leading to good fiber-matrix bonding.

7.2. Flexural Strength

• Sun dried random fiber composites followed closely with a flexural strength of 23.17 MPa, indicating that vacuum bagging ensured good resin penetration, which contributed to the material’s ability to withstand bending forces.

7.3. Impact Strength

• Sun dried random fiber composites had an impact strength of 0.68 J. This fiber network effectively distribute impact energy, leading to fiber-matrix bonding.

7.4. Results of Ftir Analysis

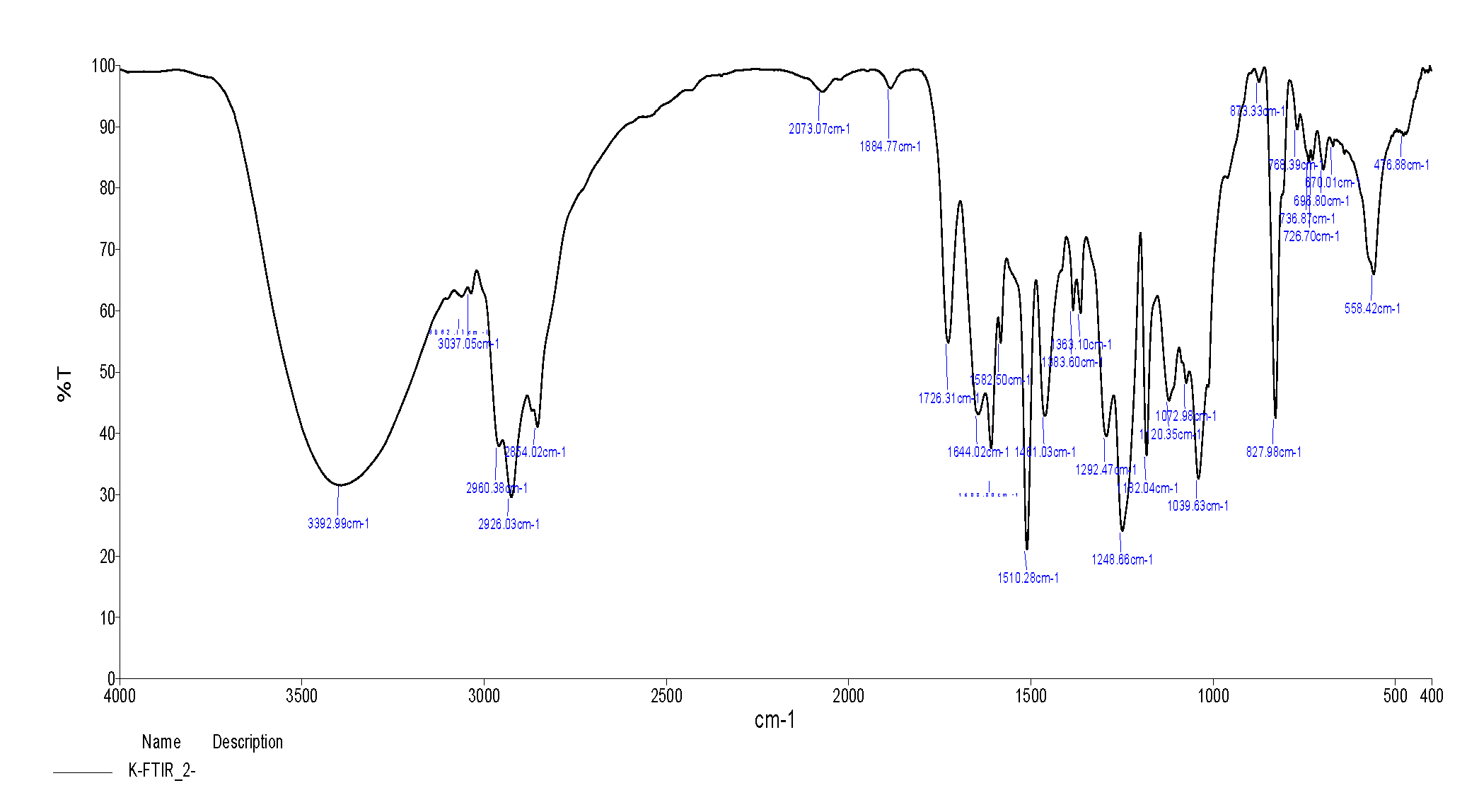

FTIR Analysis

Figure 18.

FTIR Specimen of Coir Composite.

Figure 18.

FTIR Specimen of Coir Composite.

FTIR spectra confirmed successful sun dried fiber composite material, as peaks corresponding to lignin and hemicellulose reduced in intensity. This indicates effective removal of non-cellulosic components, which enhances fiber-matrix bonding.

CNSL-modified epoxy composites showed additional ester and hydroxyl groups, confirming improved interaction between the resin and fibers. This suggests that CNSL acted as a compatibilizer, enhancing adhesion at the fiber-matrix interface.

Treated composites exhibited stronger functional group peaks, indicating better chemical bonding between the fiber and matrix. However, excessive surface modification might have reduced mechanical strength.

Sun driedCoir Composite

• O-H Stretch (3432 cm⁻¹): Strong peak indicating the presence of hydroxyl groups from cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin.

• C-H Stretch (2925, 2854 cm⁻¹): Represents aliphatic -CH₂ and -CH₃ groups, typically from lignin and hemicellulose.

• C=O Stretch (1643 cm⁻¹): Associated with carbonyl groups in lignin and hemicellulose.

• Aromatic Ring Vibrations (1510, 1461 cm⁻¹): Indicates lignin presence.

• C-O Stretch (1248, 1038 cm⁻¹): Corresponds to cellulose and hemicellulose structures.

• The structural differences confirm that alkali treatment improves fiber-matrix bonding, while CNSL enhances cross-linking, leading to a more stable composite.

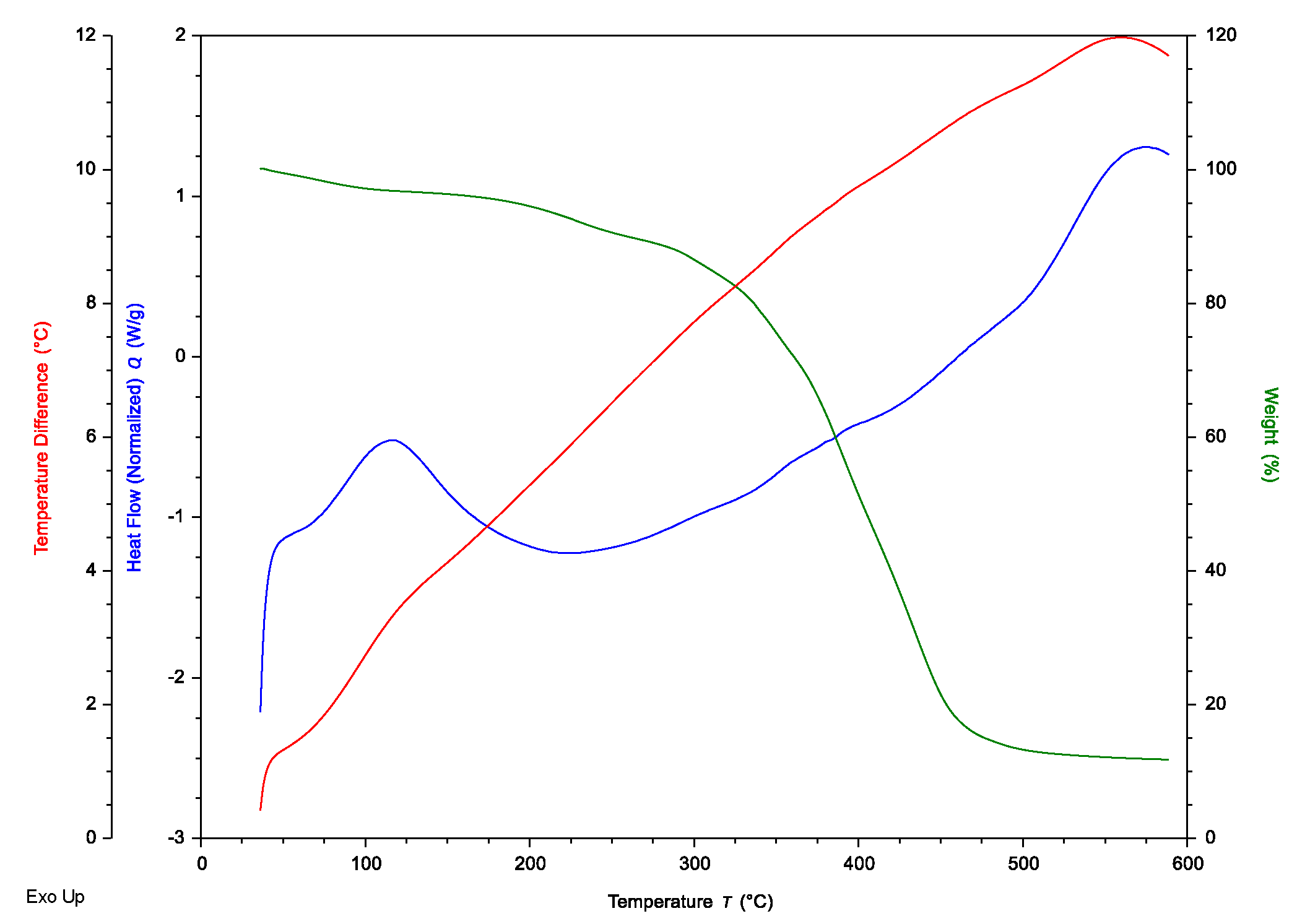

7.5. Results of TGA Analysis:

Graph Interpretation

Each graph consists of three key thermal parameters:

• Green Line: Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) - represents weight loss (%) with increasing temperature.

• Red Line: Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) - shows temperature differences, indicating phase transitions.

• Blue Line: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) - represents heat flow changes, indicating exothermic and endothermic reactions.

Figure 19.

TGA Analysis of Coir Composite.

Figure 19.

TGA Analysis of Coir Composite.

Graph 1 - Sun driedCoir Composite

Initial Decomposition (~100-150°C): A small weight loss due to the evaporation of moisture and volatile compounds.

• Major Weight Loss (250-400°C): Significant decomposition of hemicellulose and partial degradation of lignin.

• Secondary Decomposition (~450-600°C): Lignin undergoes slow degradation, indicating its thermal stability.

• Final Residue (~600°C onwards): Some char formation, suggesting incomplete combustion.

• Observation: Higher degradation rate and lower thermal

• Observation: The composite structure with CNSL/epoxy contributes to a more thermally stable material, showing controlled decomposition.

7.6. Results of Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

•Sun dried random fiber composites showed visible fiber pull-out and but good bonding. The random orientation created less gaps in the composite, leading to good load transfer and withstand failure.

Figure 20.

SEM micrograph of Resin, CNSL, Fiber Interfaces.

Figure 20.

SEM micrograph of Resin, CNSL, Fiber Interfaces.

Figure 21.

SEM Analysis of Coir Composite.

Figure 21.

SEM Analysis of Coir Composite.

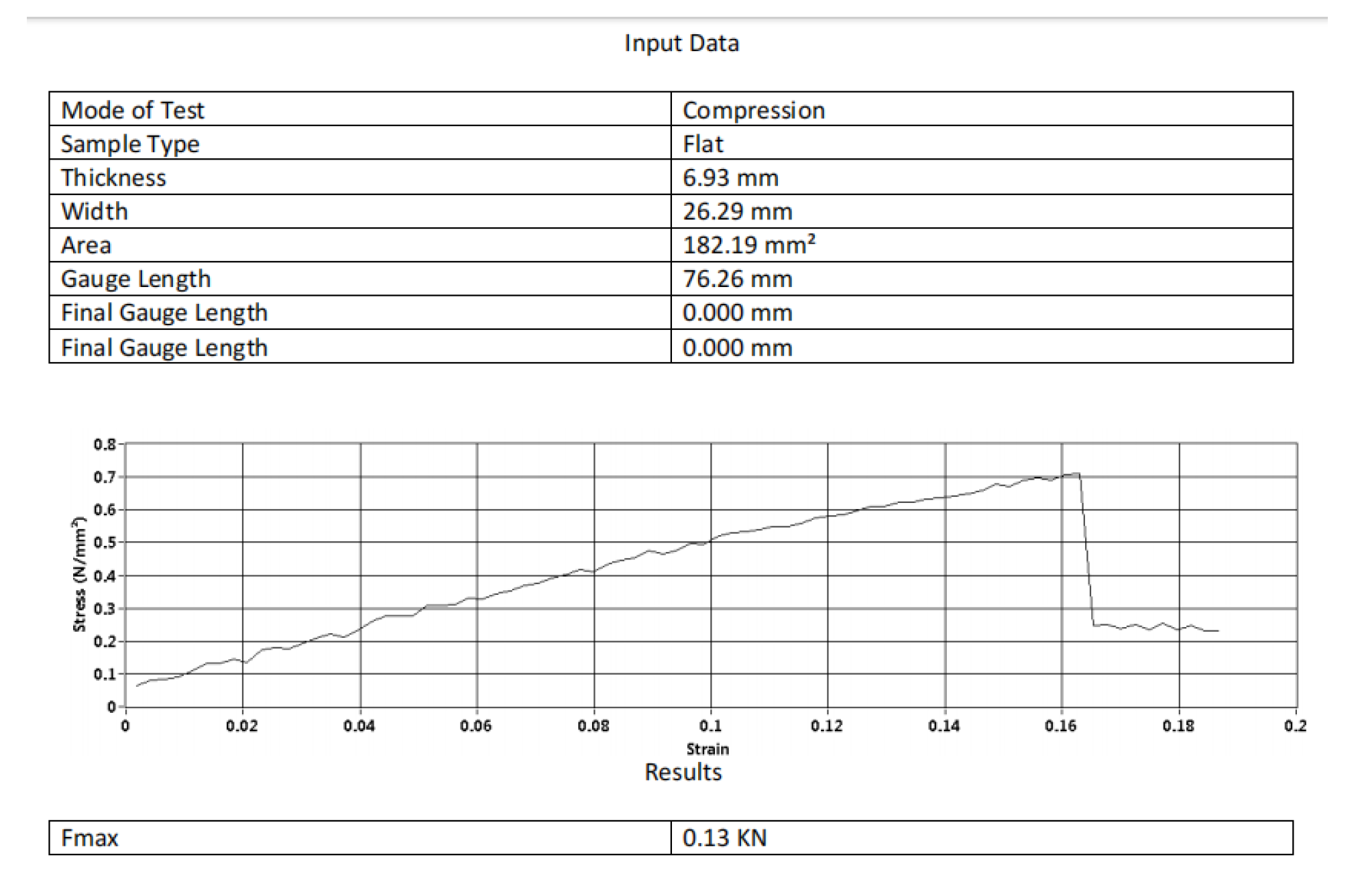

7.7. Results Stress - Strain Analysis

Overall Discussion of Findings

• Fiber arrangement plays a dominant role in mechanical performance, with fibers significantly enhancing tensile, flexural, and impact strength.

• Sun dried improved fiber-matrix bonding chemically, but it did not enhance mechanical properties, as excessive modification weakened fiber strength.

• CNSL-modified epoxy improved impact resistance and thermal stability, making it a viable alternative to conventional synthetic resins.

• Vacuum bagging ensured good resin penetration, reducing void formation and improving composite integrity.

Figure 22.

Sun Dried Coir Mat (Compression).

Figure 22.

Sun Dried Coir Mat (Compression).

Figure 23.

Sun Dried Coir Mat (Tension).

Figure 23.

Sun Dried Coir Mat (Tension).

Based on the experimental analysis, the results show that Material(Sun dried coir fiber Composite) performed better in thermal analysis, FTIR analysis, and stress-strain behavior:

1. Thermal Stability (TGA Analysis) -Sun dried material

• Material shows superior thermal stability.

• The temperature-to-weight ratio indicates that sun dried coir has better resistance to thermal degradation, meaning it retains its structure at higher temperatures.

2. FTIR Analysis - Stronger Chemical Bonding

• Alcohol (C-O) (3230-3550 cm⁻¹) and Acid (O-H) (2500-3300 cm⁻¹) groups in Material appear at higher wave numbers, suggesting enhanced chemical modifications due to sun dried fiber composite material treatment.

• The Carbonyl (C=O) peak (1670-1750 cm⁻¹) is sharper and more intense, which indicates better polymer-fiber interaction and improved bonding in the matrix.

3. Stress-Strain Curve - Higher Load Withstanding Capability

• Material sustained a higher load of 1.10 kN, showing it can absorb more stress before failure.

• This suggests that chemical treatment improved fiber-matrix adhesion, leading to better stress distribution and mechanical performance.

4. Morphology & Polymer Distribution

• SEM images indicate that this material has a more uniform polymer distribution and reduced voids, contributing to its enhanced mechanical strength.

• Material (Dried Coir Composite) performed best in thermal and chemical stability.

• It also showed higher load-bearing capacity in mechanical testing, making it a strong contender for applications requiring thermal and structural stability.

8. Conclusions

Green composites' advantages for the environment and mechanical performance continue to highlight their significance as sustainable materials with potential uses in a variety of industries. The production and planned testing of coir fiber reinforced green composites (CFRGC) using cashew nut shell liquid (CNSL) blended epoxy as the matrix and coir fibers as reinforcement—more precisely, at a 20 weight percent CNSL composition—are the main focus of this work. For assessment, two main variations have been created: Sun dried CFRGC with 20 weight percent CNSL and treated CFRGC with 20 weight percent CNSL, in which the treated fibers are mercerized using dried fiber.

The goal of the mechanical testing, which includes tensile and flexural evaluations, is to give a thorough grasp of how chemical treatment affects the coir fibers. It is anticipated that chemical treatment will improve fiber-matrix adhesion, which could result in better flexural and tensile strength. Better stress transfer between the fibers and the matrix, less fiber pullout, and stronger interfacial bonding would all contribute to this improvement.

The ultimate tensile strength and tensile modulus will be evaluated by the planned tensile tests, providing information on the composite's resistance to axial loading. Flexural testing, on the other hand, will assess the material's ability to tolerate bending pressures, indicating how well it might function in structural applications where flexural stress is common.

The study aims to determine the mechanical characteristics and maximize the performance of CFRGC by concentrating on the 20 weight percent CNSL composition. The anticipated results of these tests should demonstrate the potential of treated coir fiber composites as an eco-friendly, high-performance material that can be used in environmentally sustainable products, automobile parts, and building components.

This research will contribute to a deeper understanding of green composite behavior under mechanical loads, guiding future innovations in coir-based materials and their applications in various sectors. By investigating the combined effects of CNSL and fiber treatment, this work aligns with the broader goals of enhancing the sustainability and mechanical efficiency of modern composite materials.

References

- R. Kirubakaran, D. Nagarajan, S. Sudhakar, R. Sathiyamurthy, "Characterization of Raw and Alkali-Treated Natural Cellulosic Fibers," International Journal of Biological Macromolecules (2020).

- Mohamad Hafiz Mamat, Mohd Sapuan Salit, Ekhlas S. Azaman, Siti Fatimah I. Ismail, "Properties of Polyurethane Foam/Coconut Coir Fiber as a Core Material in Sandwich Composites," Composites Part B: Engineering (2019).

- M. Boopalan, M. Niranjanaa, M.J. Umapathy, "Effects of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Coir Fiber and Its Applications in Composites—A Review," Journal of Natural Fibers (2016).

- K. Hasan, P.G. Horváth, M. Bak, T. Alpár, "A State-of-the-Art Study on Coir Fiber- Reinforced Biocomposites," RSC Advances (2021).

- Balaji, R. Purushothaman, B. Karthikeyan, "Epoxy/Cashew Nut Shell Liquid Hybrid Polymer Composite Reinforced with Banana Fiber: Mechanical and Thermal Properties," Journal of Polymer Research (2018).

- Diksha Saxena, Vishal Kumar Sandhwar, "Thermo-Mechanical Properties of Pretreated Coir Fiber and Fibrous Chips Reinforced Tri-Layered Biocomposites," AIP Conference Proceedings (2022).

- G. Koronis, A. Silva, M. Fontul, "Green Composites: A Review of Adequate Materials for Automotive Applications," Composites B Engineering, 44(1) (2013) 120–127.

- H. Singh, J.I.P. Singh, S. Singh, V. Dhawan, S.K. Tiwari, "A Brief Review of Jute Fibre and Its Composites," Materials Today: Proceedings, 5(14, Part 2) (2018) 28427– 28437.

- L.Y. Mwaikambo, M.P. Ansell, "Hemp Fibre Reinforced Cashew Nut Shell Liquid Composites," Composites Science and Technology, 63(9) (2003) 1297–1305.

- V. Mittal, R. Saini, S. Sinha, "Natural Fiber-Mediated Epoxy Composites – A Review," Composites B Engineering, 99 (2016) 425–435.

- Libo Yan, Shen Su, Nawawi Chouw,“Microstructure, flexural properties and durability of coir fibre reinforced concrete beams externally strengthened with flax FRP composite:Composites Part B 80 (2015) 343e354.

- Ivan Malashin, Vadim Tynchenko, Andrei Gantimurov, Vladimir Nelyub and Aleksei Borodulin, A Multi-Objective Optimization of Neural Networks for Predicting the Physical Properties of Textile Polymer Composite Materials.

- Khrystyna Berladir, Katarzyna Antosz, Vitalii Ivanov and Zuzana Mital’ová, Machine Learning-Driven Prediction of Composite Materials Properties Based on Experimental Testing Data. Polymers 2025, 17, 694.

- Madina E. Isametova , Rollan Nussipali , Nikita V. Martyushev , Boris V. Malozyomov, Egor A. Efremenkov and Aysen Isametov, Mathematical Modeling of the Reliability of Polymer Composite Materials, Mathematics 2022, 10, 3978.

- Bin Liu, Lei Zhang, Anyu Liu, C. Guedes Soares, Integrated design method of marine C/GFRP hat-stiffened panels towards ultimate strength optimisation, Ocean Engineering 317 (2025) 120052.

- Yujie Rong, Pengyan Zhao, Tong Shen, Jingjing Gao, Shaofeng Zhou, Jin Huang,Guizhe Zhao, Yaqing Liu, Mechanical and tribological properties of basalt fiber fabric reinforced polyamide 6 composite laminates with interfacial enhancement by electrostatic self-assembly of graphene oxide, Journal of Materials Research and Technology 27 (2023) 7795–7806.

- Fazal Ur Rehman, Manzar Zahra, Ali H. Reshak, Iqra Qayyum, Aoun Raza, Zeshan Zada, Shafqat Zada, Muhammad M. Ramli, Development of nanosized ZnO-PVA-based polymer composite films for performance efficiency optimisation of organic solar cells, Eur. Phys. J. Plus (2022) 137:1105.

- Abideen Temitayo Oyewo, Oluleke Olugbemiga Oluwole, Olusegun Olufemi Ajide, Temidayo Emmanuel Omoniyi, Murid Hussain, Banana pseudo stem fiber, hybrid composites and applications: A review, Hybrid Advances 4 (2023) 100101.

- Sylvain Caillo, The future of cardanol as small giant for biobased aromatic polymers and additives, European Polymer Journal 193 (2023) 112096.

- Hassan Alshahrani, V.R. Arun Prakash, Mechanical, fatigue and DMA behaviour of high content cellulosic corn husk fibre and orange peel biochar epoxy biocomposite: A greener material for cleaner production, Journal of Cleaner Production 374 (2022) 133931.

- Poonam Sharmaa, Vivek Kumar Gaurb,c, Ranjna Sirohid, Christian Larrochee, Sang Hyoun Kimf, Ashok Pandey, Valorization of cashew nut processing residues for industrial applications, Industrial Crops & Products 152 (2020) 112550.

- Ibrahim Lawan, Hariharan Arumugam, Napatsorn Jantapanya, T. Lakshmikandhan, Cheol-Hee Ahn, Alagar Muthukaruppan, Sarawut Rimdusit, Development of cashew apple bagasse based bio-composites for high-performance applications with the concept of zero waste production, Journal of Cleaner Production 427 (2023) 139270.

- Vishnu Prasada,*, Ajil Joya, G. Venkatachalama, S.Narayanana, S.Rajakumarb, Finite Element analysis of jute and banana fibre reinforced hybrid polymer matrix composite and optimization of design parameters using ANOVA technique, Procedia Engineering 97 ( 2014 ) 1116 – 1125.

- Mira chares Subasha, Sankar Karthikumar, S. Nabisha Begum, C. Manjula, Optimization studies on decolourization of non-edible cashew oil for industrial application, Cleaner and Circular Bioeconomy 1 (2022) 100006.

- Mohd. Khalid Zafeer, K. Mohd. Khalid Zafeer, K. Subrahmanya Bhat, Valorisation of agro-waste cashew nut husk (Testa) for different value-added products, Sustainable Chemistry for Climate Action 2 (2023) 100014.

- Abideen Temitayo Oyewo, Oluleke Olugbemiga Oluwole, Olusegun Olufemi Ajide, Temidayo Emmanuel Omoniyi, Murid Hussain, Banana pseudo stem fiber, hybrid composites and applications: A review, Hybrid Advances 4 (2023) 100101.

- Souvik Das a, Palash Das b, Narayan Ch. Das b,∗, Debasish Das a,∗, An investigation on sisal fiber reinforced carboxylate nitrile butadiene rubber composites, Next Research 2 (2025) 100450.

- Nithesh Naik a, B. Shivamurthy a,, B.H.S. Thimappa b, Amogh Govil a, Pranshul Gupta a, Ritesh Patra a, Enhancing the mechanical properties of jute fiber reinforced green composites varying cashew nut shell liquid composition and using mercerizing process, Materials Today: Proceedings.

- Sayed Mohammad Belal a, Md Sayed Anwar b, Md Shariful Islam a,*, Md Arifuzzaman a, Md Abdullah Al Bari, Numerical study on the design of flax/bamboo fiber reinforced hybrid composites under bending load, Hybrid Advances 4 (2023) 100112.

- Olajesu Olanrewaju a,b,*, Isiaka Oluwole Oladele b,c, Samson Oluwagbenga Adelani c,d, Recent advances in natural fiber reinforced metal/ceramic/polymer composites: An overview of the structure-property relationship for engineering applications, Hybrid Advances 8 (2025) 100378.

- Adewale George Adeniyi a,*, Sulyman Age Abdulkareem a, Kingsley O. Iwuozor b, Ashraf M.M. Abdelbacki c, Mubarak A. Amoloye a, Ebuka Chizitere Emenike b, Femi Joy Bamigbola a, Ifeoluwa Peter Oyekunle d, Production and characterization of rubberized plantain fibre-reinforced polystyrene composites, Materials Chemistry and Physics 334 (2025) 130426.

- Tonni Agustiono Kurniawan a,*, Fatima Batool b, Ayesha Mohyuddin b,*, Hui Hwang Goh c, Mohd Hafiz Dzarfan Othman d, Faissal Aziz e,*, Abdelkader Anouzla f, Hussein E. Al-Hazmi g, Kit Wayne Chew h, Chitosan-coated coconut shell composite: A solution for treatment of Cr (III)-contaminated tannery wastewater, Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 166 (2025) 105478.

- Md. Ahtesham Akhter a, Dipayan Mondal a,*, Arup Kumar Debnath a, Md. Ashraful Islam a, Md. Sanaul Rabbi b, Evaluation of mechanical and thermal performance of jute and coconut fiber-reinforced epoxy composites with rice husk ash for wall insulation applications, Heliyon 11 (2025) e42211.

- Akhyar Akhyar a,b,*, Masri Ibrahim a, Zulfan a, Muhammad Rizal a, Ahmad Riza a, Ahmad Farhan c, Iqbal d, Muhammad Bahi e, Aminurf, Ully Muzakir g, The effect of differences in fiber sizes on the cutting force during the drilling process of natural fiber-reinforced polymer composites, Results in Engineering 24 (2024) 103128.

- Easwara Prasad G La, Keerthi Gowda B Sb *, Velmurugan Rc, A Study on Impact Strength Characteristics of Coir Polyester Composites, Procedia Engineering 173 ( 2017 ) 771 – 777.

- Hamid Essabir a, Radouane Boujmal b, Mohammed Ouadi Bensalahb, Denis Rodriguec, Rachid Bouhfida, Abou el kacem Qaiss a,∗, Mechanical and thermal properties of hybrid composites: Oil-palm fiber/clay reinforced high density polyethylene, Mechanics of Materials 98 (2016) 36–43.

- Muhammad Yasir Khalid a, Ans Al Rashid b,*, Zia Ullah Arif a, Waqas Ahmed a, Hassan Arshad a, Asad Ali Zaidi c, Natural fiber reinforced composites: Sustainable materials for emerging applications, Results in Engineering 11 (2021) 100263.

- H. Essabir a, M.O. Bensalahb, D. Rodriguec, R. Bouhfida, A. Qaiss a,∗, Structural, mechanical and thermal properties of bio-based hybrid composites from waste coir residues: Fibers and shell particles, Mechanics of Materials 93 (2016) 134–144.

- Nutenki Shravan Kumar a, Tanya Buddi a, A. Anitha Lakshmi a, K.V. Durga Rajesh b, Synthesis and evaluation of mechanical properties for coconut fiber composites- A review, Materials Today: Proceedings 44 (2021) 2482–2487.

- Rosni Binti Yusoff a, Hitoshi Takagi b,∗, Antonio Norio Nakagaito b, Tensile and flexural properties of polylactic acid-based hybrid green composites reinforced by kenaf, bamboo and coir fibers, Industrial Crops and Products 94 (2016) 562–573.

- Arya Widnyanaa, I Gde Riana, I Wayan Suratab, Tjokorda Gde Tirta Nindhiab,*, Tensile Properties of coconut Coir single fiber with alkali treatment and reinforcement effect on unsaturated polyester polymer, Materials Today: Proceedings 22 (2020) 300–305.

- P. Sruthi a,b, M. Madhava Naidu a,b,*, Cashew nut (Anacardium occidentale L.) testa as a potential source of bioactive compounds: A review on its functional properties and valorization, Food Chemistry Advances 3 (2023) 100390.

- Majid Mohammadi a, Ebrahim Taban b,**, Wei Hong Tan c, Nazli Bin Che Din d, Azma Putra e, Umberto Berardi f, Recent progress in natural fiber reinforced composite as sound absorber material, Journal of Building Engineering 84 (2024) 108514.

- Tatiana Zhiltsova 1,2 , Andreia Costa 3 and Mónica S. A. Oliveira 1,2, Assessment of Long-Term Water Absorption on Thermal, Morphological, and Mechanical Properties of Polypropylene-Based Composites with Agro-Waste Fillers, J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 288.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).