1. Introduction

The notion that “a rising tide floats all boats” is fading away [

1,

2]

. The idea that mere economic progress is the key to development [

3,

4] is no longer tenable. The top-down developmental approaches argued by trickle-down economic theories had a central argument that ‘economic development’ ensures national prosperity [

5]. The development programs by global agencies, therefore, adopted the trickle-down mechanisms to develop the ‘underdeveloped’ across the world—especially in Asia, Africa, and Latin America after WWII. Escobar [

6] states that since 1950s (post-WW-II), the developmental process has been more of an un-underdeveloping task in third-world countries by subjecting their societies to increasingly systematic, detailed, and comprehensive interventions.

In recent decades, a myriad of schools of thought started to view development based on the relative necessity and importance of the process for particular social and ecological contexts [

7,

8]. One such ‘un-underdeveloping’ task manifested prominently as ‘microentrepreneurship’ by poor people in rural communities with the help of NGOs. Since 2000, such an NGO-led developmental approach emerged as a popular grassroots intervention mechanism; eventually, helped create millions of community-based enterprises (CBEs), especially in the developing world [

9]. Typically, global developmental bodies, such as the UN agencies, World Bank, and other regional developmental banks, primarily follow a macro-scale top-down approach towards development. Such approaches are usually maintained at national and international scales and reflect the structural and macroeconomic agenda. It is largely unknown whether those approaches adequately address the sustainability and wellbeing issues at the community level. The question arises: can the CBEs support community-level sustainability (as they operate in the community and by the community entrepreneurs)?

The question of community-level sustainability is gaining much traction in recent decades. The global development agenda, such as Rio Declaration 1992 and UN-MDG 2000, emphasized sustainability; the contemporary Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) meant to be pursued until 2030, aiming to bring about sustainability at all levels - local to global. Scoon [

10] suggests that there are clear opportunities for the insertion of sustainability agendas in new ways into policy discourse and practice at all levels (from local to global) since addressing climate is central to those policies and planning. Nevertheless, the literature on the potential of CBEs to contribute to community-level sustainability is scant.

The CBE modality considers economic benefit as a prime goal [

11]. The benefits transcend to the societal level too, as the CBEs help empower women, contribute to social equality, and foster social capital [

12,

13]. However, the modality pays little or no attention to the ecological benefit [

14]. Evidence suggests that the CBEs have the potential to support sustainability from the bottom as grassroots organizations [

7,

15]. As developmentalism is a dynamic process, it can be presumed that redesigning the CBE modality with the inclusion of ecological objectives (alongside its economic and social contributions) might bring about sustainability at the local level. Therefore, this paper aims to argue whether a shifted microentrepreneurship modality with the inclusion of ecological objectives would result in a new framework for local sustainability.

2. Developmentalism: Shifting Focuses

Developmentalism is marked with shifting focuses over time [

16,

17]. The history of development practice shows how the debates among eighteenth and nineteenth-century philosophers became a practical pursuit during the twentieth century [

18]. The Marshall Plan, the Monroe Doctrine, and the Stalin-styled export of Soviet industrialism and communism all represented significant policies that were put into effect through interventions with ‘nations perceived as being underdeveloped’ [

19]. These policies and their funding spawned a plethora of development programs ranging from small-scale community development work to large-scale economic and political interventions [

18]. While the issues of economic, social, and political well-being were in focus, ecological issues were mainly missing in those policies or intervention strategies until recently [

7].

The modern development debates, as opposed to the more general debate about the causes of poverty and economic growth, date back to the early post-WWII period. They are closely associated with the approaches of decolonization, nation-building, national planning, and development aid over the new international economic order [

20,

21,

22]. These developmental approaches entailed many evolving theories, hypotheses, models, techniques, and empirical applications. In taking stock of those developmental approaches, Thorebcke [

7] and Shahidullah [

16] indicated their focuses in specific decades; following their summary, the table here (

Table 1) provides decade-wise excerpts (

Table 1):

During the 1950s, economic growth became the primary policy objective in the newly independent (decolonized) less developed countries adopting an ‘industrialization-first strategy.’ The strategy was advocated by a belief that economic growth and modernization would eliminate income and social inequalities. Theories that contributed to subsuming such belief by the development economists were: ‘big push’ [

23], ‘balanced growth’ [

24], ‘take-off into sustained growth’ [

25], and ‘critical minimum effort thesis’ [

26].

Building on such theoretical and conceptual developments of the 1950s, the dual economy model came into being and became more sophisticated in the 1960s. It recognized the interdependence between the functions of the modern industrial and backward agricultural sectors [

27]. However, one of the major underlying flaws of this approach was that ‘growth’ and ‘development’ were thought synonymous [

28]. The dual economy model, therefore, fuelled intense debate as anti-poverty programmes and redistribution of wealth did not go hand in hand.

The decade of 1970s witnessed a shift in the preference (welfare) function—away from aggregate growth per se toward poverty reduction and increasing investment transfers in projects benefiting the poor [

29]

. The rising number of people in a state of poverty led to the incorporation of ‘poverty alleviation’ as one of the key development objectives other than GNP growth. Theoretical approaches such as the package approach in traditional rural areas, the role of the informal sector, rural-urban migration, underdevelopment theory, and dependency theory underpin those policies and strategies. The key intervention mechanisms were integrated rural development, comprehensive employment strategies, redistribution with growth, basic needs, reformist (asset redistribution), and radical-collectivist strategies.

The development strategies in the 1980s dealt with many macroeconomic adjustments, what was termed structural adjustment policies. The neoliberal theory of economic development came to dominance, whereby privatization and free trade were intensely promoted in the economic sphere. In the 1990s, however, good governance, the role of institutions in development-path dependency, and the endogeneity of policies and social capital were the theoretical lenses that helped resurface poverty alleviation and improved socioeconomic welfare as core agendas for underdeveloped countries.

After 2000, key objectives of the development doctrines comprised human development, and poverty reduction—addressing inequality and vulnerability. Global developmental agenda, e.g., Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), subsumed many goals. Two dominant policies, globalization as a development strategy and the search for pro-poor growth, have been adopted by most countries [

30,

31]. The political economy of development and the role of institutions reclaimed significant dominance in the theoretical sphere of development, where one of its major tenets is that ‘more equal initial income and wealth distribution is consistent with and conducive to growth’ [

16].

3. Community-Level Sustainability

Sustainability implies a system's ability to survive or persist; biologically, this means avoiding extinction and living to survive and reproduce; economically, it means avoiding major disruptions and collapses, hedging against instabilities and discontinuities [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Berkes et al. state that sustainability is maintaining the capacity of ecological systems to support social and economic systems [

36]. Therefore, it is considered a process, rather than an end product, a dynamic process that requires adaptive capacity for societies to deal with change [

35,

36]. Several important events and political actions and the subsequent outcome documents helped evolve the eventual notion of sustainability; these are: i) Stockholm Conference on the Human and Environment and the establishment of UNEP in 1972 [

37] ii) ‘Limits to Growth Report’ [

38] iii) the ‘US Global 2000 report to the president’ [

39] iv) ‘The resourceful earth’ [

40] v) ‘The World Conservation Strategy’ [

41] and most notably vi) UN Brundtland Commission Report, ‘Our Common Future’ [

42].

The aforementioned strategy and policy documents looked at the idea of sustainability as a macro-level approach where state, regional, or international bodies are the key actors in putting the sustainability process into practice. Thus, the classic notion of sustainability holds that societal, environmental, and economic objectives are mutually reinforcing, and the process is argued mainly at national and international scales. For example, the practice was more visible in the realms of multi-lateral negotiations (climate, trade, biodiversity, and other similar discourses) and policies of global organizations (UN, World Bank, and other development agencies). Escobar [

43] viewed that though sustainability appeared as a broader process of the problematization of global survival, the slogan ‘think globally, act locally’ assumes, not only that problems can be defined at a global level but also that they are equally compelling for all communities. Similarly, other scholars started to question popular discourses on globalization and sustainable development, stating that ‘since global discourses are often based on shared myths or blueprints of the world, the political prescriptions flowing from them are often inappropriate for local realities’ [

44, p. 683].

Indeed, the political and cultural difficulties in achieving sustainability at a global level justify the considerations of sustainability at the community level [

45]. By shifting the focus on sustainability to the local level, changes are seen and felt more immediately. ‘Sustainable society' or ‘a sustainable world' are meaningless to most people since they encapsulate abstraction levels irrelevant to their daily lives. Contrarily, ‘locality’ bears a significant meaning and sense to people as it is the very level of social organization where the consequences of environmental degradation or results of interventions are most keenly felt and noticeable by the stakeholders [

7]. And, of equal importance, there tends to be greater confidence in government action at the local level. Yanarella and Levine [

46] envisioned that sustainable community development would ultimately be the most effective means of demonstrating the possibility that it can be achieved also on a broader scale.

Youngberg and Harwood [

47] suggest that sustainability at the community level may demand a specific approach as the complex nature of interrelationships between nature and societies in diverse geographic locations and topographic realities would not allow for applying a ‘one size fits all’ solution. Meanwhile, the idea of community-based sustainable development as a bottom-up approach came to the forefront [

48]; scholars, e.g., Luloff and Swanson [

49], Bridger (

50), and Wilkinson [

51] underscore that sustainable development rooted in place-based communities has the advantage of flexibility as the communities differ in terms of environmental problems, natural and human resource endowments, levels of economic and social development, and physical (i.e. geological and topographical), and climatic conditions.

Bridger and Luloff [

45] see community-level sustainability as an approach that meets the economic needs of the local people, enhances and protects the local environment, and promotes more humane local societies. The UN Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) of 2005 findings strengthen the fact that people are integral parts of ecosystems, and a dynamic interaction exists between humans and the environment [

52]. The assessment finds that 15 of the 24 ecosystem services (ES) that directly contribute to human well-being are being systematically degraded, and development initiatives and their progress would not be sustained if the ES continue to degrade [

52,

53]. Future scenarios on local human-environment symbiotic relations indicate a severe and irreversible decline of these ES [

52,

54]. Therefore, it is crucial to see sustainability as a community-level approach designed with policies and practices sensitive to the opportunities and constraints inherent to the local people and the environment [

55].

4. Community-Based Enterprises: New Developmental ‘Dispositif’

The post-2000 developmental agenda [e.g., MDG, MA, SDG] brought three elements to the forefront of developmental discourse: i) management of ES for human well-being, ii.) action at the local level, with local organizations as the key actors, and iii) enterprise development at the community level as a widely practiced developmental intervention tool [

52,

56,

57]. Unlike traditional developmentalism, enterprise development emerged as a popular intervention tool and helped create millions of micro-enterprises, especially in the developing world [

58]. The rural community-based micro-enterprise development initiative has mainly economic development and, to some extent, a social development agenda [

11,

59]. These microenterprises, as an offshoot of the microcredit movement, are perceived to be workable in easing some woes of economic and social inequalities at the bottom by creating entrepreneurial subjects, generating alternative income sources, forming social capital, and empowering women [

7,

14]. As bringing about sustainability at the community level is a more significant task, is it tenable to put these three elements together in the developmentalism discourse—especially in community-level developmentalism?

The efficacy of ‘community-based enterprise’ (CBE) as an instrument for developmentalism, especially poverty reduction, is supported by a vast body of literature, e.g., Pitt & Khandaker [

12]; Mayoux [

60]; Afrin et al. [

61]. Many authors, including Dowla [

62] and Rankin [

63], note that CBEs contribute to social capital formation at the community level. More importantly, the CBE modality is seen as a ‘bottom-up’ [

64] and gendered [

60] approach to development. However, there are scholars, e.g., Chen and Dunn [

65], Tripathi [

66], and Foose [

67], who contest the positive impact of microenterprise-oriented developmentalism and point out numerous aggravating challenges that the initiative faces. Despite such debates, the CBE modality became even more popular with the advent of NGOs being a key development partner at a community level and started to play a greater role than before since 2000 [

15]. As NGOs emerged as a crucial developmental actor with the downsizing of state-based social welfare and development functions, the proliferation of CBE occurred across the communities of developing countries, e.g., Bangladesh. Shahidullah [

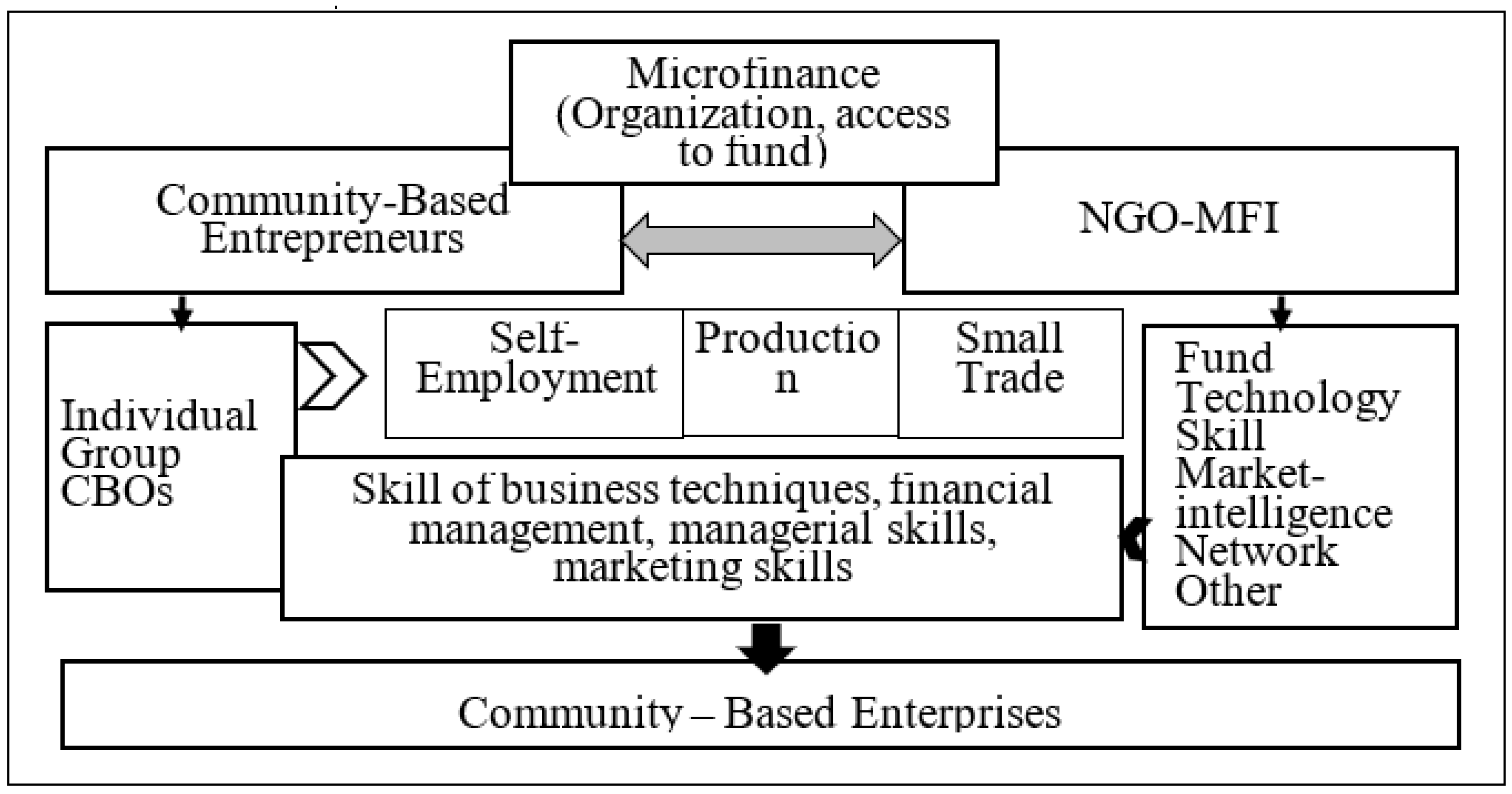

14] states that the shift, i.e., NGO being a key community-level developmental actor, signaled a dispersion of developmentalism itself. The following figure (Figure. 1.1) exhibits the actors and elements of the classic CBE model that emerged out of microcredit-based developmentalism with NGO as a key facilitator.

Figure 1.

Actors and elements of the classic CBE model.

Figure 1.

Actors and elements of the classic CBE model.

In this model, NGOs seem to have shouldered the task of ‘un-underdeveloping’ at the community level. Consequently, NGOs' wide adoption of microfinance mechanisms became a dominant developmental phenomenon. Many NGOs literally turned to be Microfinance Institutions (MFI), while many others incorporated microfinancing as a key component of their operation. Apart from offering access to funds to the community people, the qualitative changes that the shift brought are the dispersion of skills and knowledge on new and diversified ventures [14-16]. The capacity of the community entrepreneurs is further enhanced with training on production technologies, market intelligence, networks, and linkages - most of which come as a bundle with microfinance [

16]. Nonetheless, the sustainability and implications of this dispersion of developmentalism are largely unknown. There is hardly any study that can concretely establish the comprehensive efficacy of microfinance or, on the contrary, can deny its developmental benefit downright. Sen [

68] mentioned that many of the developmental achievements of post-1970 Bangladesh are the outcomes of NGO operation along with public policy—recognizing particularly the contributions of two major microfinancing organizations, BRAC and Grameen Bank, that are championing the establishment of CBEs across the globe.

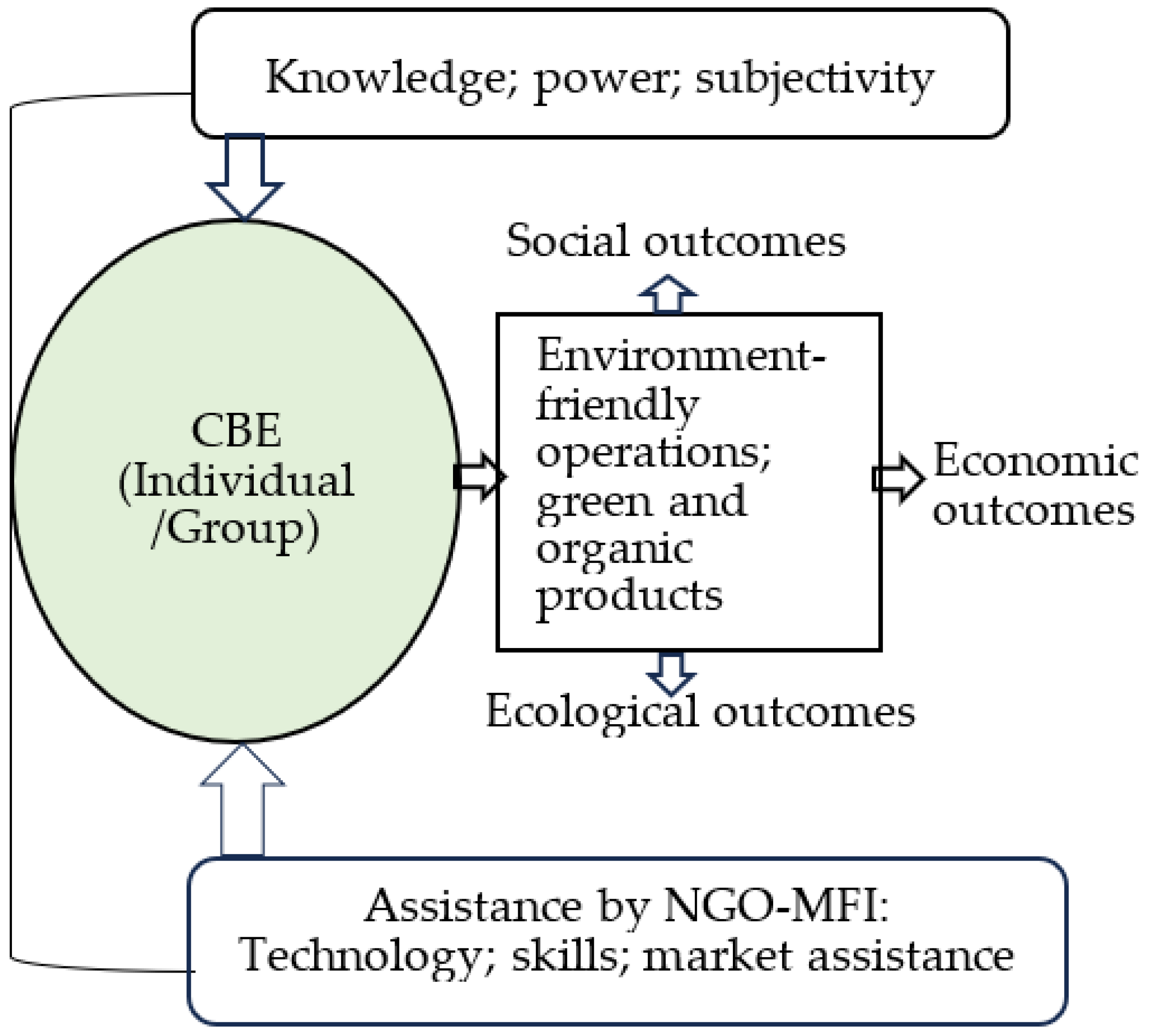

5. A Social-Ecological Model of Community-Based Entrepreneurship

The CBE modality contributes at the local level with proven economic (e.g., poverty reduction) and social (e.g., women empowerment, building social capital) outcomes – but it misses a key element, i.e., environment, to be supportive of ‘sustainability’ [

15]. The present mode of operations of most micro-enterprises has negative environmental impacts [

69] due to several reasons: their sheer numbers, ubiquitous presence, extended hours of operation, lack of supervision by regulatory and environmental agencies, low technological level, and lack of supporting infrastructure and services [

70]. However, evidence suggests that the CBEs can go green with the help of NGOs [

15]. Microenterprises that maintain sustainable production techniques, such as organic inputs, reforestation, recycling, controlled water usage, natural pesticides, solar water pumps, and other conservation measures can support sustainability [

71]. Thus, an environmental orientation of CBE modality can have dual benefits in offsetting the negative impacts and enhancing the positive contributions to ecosystem services (ES) [

15].

Against such backgrounds, a shifted CBE modality with the inclusion of ecological objectives (along with the economic and social) promises to ensure sustainability at the community level. The shift is tenable as developmentalism is a dynamic process [

16]. There might be concern about what conceptual or theoretical structure would allow accommodating such a shift. Brigg [

72] draws on Foucault's notion of ‘dispositif’ to capture the microcredit-led developmental approach in part and then to question the traditional developmentalism in place [

73]. ‘Dispositif,’ a French-loaned term that means apparatus or device or deployment – scholars used it to mean ‘social apparatus’ and ‘regime of practice’ - both of which indicate an ordering of social practices that are infused with a particular ‘strategic disposition’ [

74,

75]. The ‘dispositif’ lens considers the relationships between the various elements in that ‘strategic disposition’ in terms of relations of knowledge (discourse), power, and subjectivity [

75].

Silva Castaneda [

76] suggests that the idea of dispositif is nested as a strategic state between the disruptive and stabilizing lines; rather than focusing on the current state of play, it allows reshuffled initiatives and accompanying relations of knowledge, power, and subjectivity in their appropriate dispersion - meaning that a strategy needs not to be reduced to a particular set of relations. With this lens, a community-level sustainability dispositif based on the microfinance strategy requires a move beyond the problems surrounding critical approaches based on economic relations. As dispositif allows for a less programmatic approach by conceptualizing development as a shifting coagulation of elements that exhibit certain continuities and discontinuities with previous formation [

72] -- a reconfiguration of developmentalism through the rise of NGOs is tenable. Therefore, a shift in the existing CBE paradigm is permeable with the inclusion of ecological objectives. This shift allows NGOs to be in the dispositif locus, redeploying entrepreneurial subjectivity and institutions within the conventional microfinance scheme - thereby redirecting developmentalism toward achieving local sustainability.

NGOs can achieve this sustainability goal through environmental lending or, more particularly, ES-supportive lending to the community, group, or individual entrepreneurs. The primary operational tasks involve defining and determining green ventures, supply and adoption of green technologies, knowledge, affordability, and viability. The emphasis of the greening efforts should be to convince local entrepreneurs of the constraints of the natural environment, the high market demand for green and organic products, and the availability of technical and financial assistance from intermediary organizations. Further, to avoid the initial market distortions and inefficiency and to increase environmental awareness, NGO or intermediary assistance should consist of an aid bundle with loans and grants to increase environmental awareness and develop and diffuse environmentally friendly technologies.

Innovative entrepreneurial strategies built on local strengths can help reorder people’s relationships with local ecosystems, restore community wellbeing, and enhance local sustainability [

77]. The enterprises must be strengthened with management capacity to adopt and manage the new approach. Although this will require multiple stakeholders to work jointly toward the goal, the initial and most instrumental role must be played by the NGO-MFI as the key development partner. This conceptual schema of this modality is shown in

Figure 2.

6. Conclusions

The state of play in development efforts, can be termed ‘development dispositif,’ was mostly indoctrinated by many theories, hypotheses, strategies, and models. Nevertheless, developmentalism has always been dynamic and, to some extent, experimental by nature. Over time, development policies, especially in the post-colonial decades, have been marked by frequent changes and shifts. Development strategies expanded focus: for example, from industrialization first to balanced growth, economic development to economic and social development, GNP growth strategy to poverty alleviation, and lately from development to sustainable development.

Contemporary developmentalism is faced with the challenges of managing ecosystem services, alleviating poverty, and linking problems and actions locally. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) has explicitly brought forth the gravity and significance of managing ecosystems for achieving qualitative development or human well-being. Although arguments became more potent that the development effort needs to transcend the benefits at the community level, hardly any other intervention strategy gained as widespread popularity as the microfinance mechanisms. The CBE modality out of NGO-MFI facilitation is viewed as an approach that is entrepreneurial, bottom-up, gendered, and social capital builder. With its economic and social contributions, the strategic shift through the inclusion of ecological objectives ensures its contribution to local sustainability.

Classic developmentalism has been largely economistic rather than integrated. Its top-down and macro-scale natures are characteristically inept at effectively addressing the causes of underdevelopment at the community level. Microcredit guru Prof. Yunus [79] mentions that these development theories are half-done as still half the people globally survive with less than $2 a day.

Since dispositif enables a less programmatic approach by conceptualizing development as a coagulation of elements that exhibit certain continuities and discontinuities with previous formation, the inclusion of the EGS management principle within the microfinance strategy is permeable within the framework. With the microentrepreneurship approach being an instrument for development with household, group, or community organizations as subjects for developmentalism, unlike the traditional top-down approaches, sustainability at the community level would be ensured through the new social-ecological model of community-based entrepreneurship.

Author Contributions

I (Dr. AKM Shahidullah) am the sole author of the paper.

Funding

The research is carried out under a funded project entitled “ Green Microfinance Strategy for Entrepreneurial Transformation: Supporting Growth and Responding to Climate Change”. The author received financial support for the study from the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), UK (Grant # PEDL-ERG, 1752). The author thanks Dr. Helal Mohiuddin for his insightful comments and suggestions on the draft article.

Informed Consent Statement

N/A

Data Availability Statement

N/A

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Memorial University of Newfoundland, Grenfell campus for additional in kind and financial supports for his Community-Based Entrepreneurship’ project.

Conflicts of Interest

N/A.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBE |

Community-Based Enterprise |

| NGO |

Non-Governmental Organization |

| MFI |

Microfinance Institution |

| MDG |

Millennium Development Goals |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| MA |

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment |

References

- Bello, A. D. "Navigating Beyond Economic Growth: A Holistic Approach to Development and Equality in Public Policy—Demystifying the Axiom “A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats”. Open J. of Soc. Sci, 2024, 12, 533-573. [CrossRef]

- Hines Jr, J.R., Hoynes, H.W., & Krueger, A.B. Another look at whether a rising tide lifts all boats. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Washington, DC, 2001, Working Paper No. 8412.

- Schickele, R. Agrarian revolution and economic progress; Cornell University Press: NY, USA, 1968.

- Smith, T. Requiem or new agenda for Third World studies? World Politics, 1985, 37(4), 533-534.

- White, C. Understanding Economic Development: A Global Transition from Poverty to Prosperity?; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2009.

- Escobar, A. Encountering development: the making and unmaking of the Third World; Princeton University Press, NJ, USA, 1995.

- Shahidullah, A. K. M.; Venema, H. D.; Haque, C.E. Shifting developmentalism vis a vis community sustainability: Can Integration of ecosystem goods and services with microcredit create a local sustainability dispositif? Int’l J. of Dev. and Sust, 2013, 2(3), 1703-1722.

- Narayan-Parker, D.; Patel, R. Voices of the poor: Can anyone hear us? World Bank Publications: Washington D C., 2000.

- Waller, G. M.; Warner, W. Microcredit as a grass-roots policy for international development. Poli. Stud. J., 2001, 29(2), 267-282.

- Scoones, I. "Sustainability." Dev. in Pract., 2007, 17( 4-5), 589-596.

- Vargas, C. Community development and micro-enterprises: fostering sustainable development. Sust. Dev., 2000, 8, 11–26. [CrossRef]

- Pitt, M. M.; Khandker, S. R.; Cartwright, J. Empowering women with micro-finance. Evidence from Bangladesh. Econ. Dev. & Cult. Chng, 2006, 54(4),791–831.

- Anderson, C. L.; Locker, L.; Nugent, R. Microcredit, social capital, and common pool resources. World Dev, 2002, 30(1), 95-105.

- Shahidullah, A. K. M. Community-Based Developmental Entrepreneurship: Linking Microfinance with Ecosystem Services. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Manitoba, Canada, 2016.

- Shahidullah, A. K. M.; Haque, C. E. Environmental orientation of small enterprises: can microcredit-assisted microenterprises be “green”? Sustainability, 2014, 6(6), 3232-3251. [CrossRef]

- Thorbecke, E. The evolution of the development doctrine, 1950-2005. UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). Helsinki, Finland, 2007.

- Marangos, J. What happened to the Washington Consensus? The evolution of international development policy. The J. of Soc-eco, 2009, 38(1), 197-208. [CrossRef]

- Larrison, C.R. A comparison of top-down and bottom-up community development interventions in rural Mexico: Practical and theoretical implications for community development programmes. Government Document Reports of the Findings of a Field Research Project, 2000.

- Moore, D. Development discourse as hegemony: Towards an ideological history—1945–1995. In Debating development discourse: Institutional and popular perspectives, Moore D.D., Schmitz, G.G. Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK; 1995, pp. 1-53.

- McNeill, J.R. Something new under the sun: An environmental history of the twentieth-century world. Norton & Company: NY, USA, 2000.

- Berger, M. T. From nation-building to state-building: The geopolitics of development, the nation-state system and the changing global order. Third World Qtrly., 2006, 27(1), 5-25. [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.E. From Marshall Plan to debt crisis: Foreign aid and development choices in the world economy. Univ of California Press: CA, USA, 2024 (15).

- Sachs, J.D.; Warner, A.M. The big push, natural resource booms and growth. J. of dev. Econ. 1999, 59(1), 43-76. [CrossRef]

- Nurkse, R. The Theory of Development and the Idea of Balanced Growth. In Developing the Underdeveloped Countries; Mountjoy, A.B., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1971; pp. 115–128.

- Rostow, W.; Baker, Jr.; Rex, G. Baker Jr, eds. The economics of take-off into sustained growth. Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1963; pp. 1–83.

- Leibenstein, H. Economic backwardness and economic growth. Wiley: New York, USA, 1957.

- Fei, J.C.H.; Ranis, G. Development of the labor surplus economy. Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1964. [CrossRef]

- Corbridge, S. Thinking about development. Regional Studies, 1998, 32(8), 790-791.

- Chenery, H.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Duloy, J.H.; Bell, C.L.G.; Jolly, R. Redistribution with growth; policies to improve income distribution in developing countries in the context of economic growth. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1974.

- White, H. Pro-poor growth in a globalized economy. J of Int’l Dev., 2001, 13(5), 549-570. [CrossRef]

- Nissanke, M. Pro-poor Globalisation: An Elusive Concept or a Realistic Perspective’. Inaugural Lecture Series. SOAS, University of London, London, 2007.

- Constanza, R.; Patten, B.C. Defining and predicting sustainability. Ecol. Econ., 1995 (15), 193–196.

- Kuhlman, T.; John, F. What is sustainability? Sustainability, 2010, 2(11), 3436-3448.

- Spangenberg, J. H. Economic sustainability of the economy: concepts and indicators. Int’l J. of Sust. Dev., 2005, 8(1-2), 47-64. [CrossRef]

- Shiva, V. Recovering the real meaning of sustainability. In The Environment in Question: Ethics and Global Issues, 1st Ed.; Cooper, D., Palmer, J.A.E. Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993; pp. 187-193.

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. (eds.). Navigating social-ecological systems: building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 393.

- Handl, G. "Declaration of the United Nations conference on the human environment (Stockholm Declaration), 1972 and the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, 1992." United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law, 2012, 11(6), 1-11.

- Meadows, D; Jorgan R. The limits to growth: the 30-year update. Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012.

- Barney, G. O. The Global 2000 Report to the President of the US: Entering the 21st Century: The Technical Report. Elsevier, 2013 (2).

- Stroup, R. L.; Jane, S. S. The Resourceful Earth. The Intercollegiate Review, 1985, 20(3), 63-65.

- World Wildlife Fund. World conservation strategy: Living resource conservation for sustainable development. IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1980, Vol 1.

- Brundtland, G. H. Our common future—Call for action. Environmental conservation, 1987, 14(4), 291-294.

- Escobar, A. Construction nature: Elements for a poststructuralist political ecology. Futures, 1996, 28 (4), 325-343.

- Adger, W.N.; Benjaminsen, T.A.; Brown, K.; Svarstad, H. Advancing a political ecology of global environmental discourses. Dev. and chng., 2001, 32(4), 681-715.

- Bridger, J.C.; Luloff, A.E. Toward an interactional approach to sustainable community development. J. of rur. studs., 1999, 15(4), 377-387. [CrossRef]

- Yanarella, E.J.; Levine, R.S. Does sustainable development lead to sustainability? Futures, 1992, 24(8), 759-774. [CrossRef]

-

Youngberg, G.; Harwood, R. Sustainable farming systems: needs and opportunities. Amecn. J. of Alt. Agri., 1989, 4 (3-4), 89-90. [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Common-property resources: Ecology and community-based sustainable development. Belhaven Press: London, 1989.

- Luloff A.E.; Swanson, L.E. Community agency and disaffection: enhancing collective resources. In Investing in people: The human capital needs of rural America; Beaulieu, L.J. , Mulkey, D. eds., Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995; pp. 351-372.

- Bridger, J.C. Power, discourse and community: the case of land use. Doctoral thesis, Penn State University, University Park, PA, USA, 1994.

- Wilkinson, K.P. The community in rural America. Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1991.

- MA. (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: synthesis. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment(MA); Island Press: Washington D.C., USA.

- World Resources Institute. World Resources, 2005: The Wealth of the Poor: Managing Ecosystems to Fight Poverty. Vol. 11. World Resources Institute, 2005. Washington, DC, 2005. http://pdf.wri.org/wrr05_lores.pdf [accessed 3 Feb 2025].

- Brauman, K.; Daily, G.; Duarte, T.; & Harold, A. The nature and value of ecosystem services: an overview highlighting hydrological services. Annl. Rev. of Env. and Res., 2007, 32, 67-98. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G. A. Community resilience, policy corridors and the policy challenge. Land use pol., 2013, 31, 298-310.

- Hazlewood, P.; Greg, M. Ecosystems, Climate Change and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). World Resource Institute (WRI): Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.wri.org/publication/ecosystems-climate-change-millennium-development-goals. [accessed 1 Feb 2025].

- Torri, M. Community-based Enterprises: A Promising Basis towards an Alternative Entrepreneurial Model for Sustainability Enhancing Livelihoods and Promoting Socio-economic Development in Rural India. J. of Small Bus. & Entr., 2010, 23(2), 237-248. [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H., P.; and Barbara, A., K. Community-based enterprises: propositions and cases. An Entrl. Bona., 2002, 17-20.

- Mustapa, W.; Al Mamun, A.; Ibrahim, M. Development initiatives, micro-enterprise performance and sustainability. Int’l J. of Fin. Stud., 2018, 6(3), 74. [CrossRef]

- Mayoux, L. Women’s empowerment versus sustainability? In Women and credit. researching the past, refiguring the future; Beverly L., Ruth P, Gail C. (eds.); Berg: New York: Berg, 2002.

- Afrin, S; Nazrul, I; Shahid, U., A. Microcredit and rural women entrepreneurship development in Bangladesh: a multivariate model. J. of Bus. & Mgmt, 2010, 16(1), 9-36.

- Dowla, A. In credit we trust: Building social capital by Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. The J. of Soc-Eco, 2006, 35(1), 102-122. [CrossRef]

- Rankin, K. Social capital, microfinance, and politics of development. Fam Econ, 2002, 8(1), 1-24.

- Narayanaswami, K. Microfinance and the Human Condition: A Bottom-Up Approach towards Promoting Freedom and Development. Social Sciences, 2010, 102-104.

- Chen, M.A.; Dunn, E. Household economic portfolios. Management Systems International: Washington, D.C., 1996.

- Tripathi, S. Micro-credit won’t make poverty history. The Guardian, 17 October, 2006.

- Foose, L. The double bottom line: evaluating social performance in microfinance. MicroBanking Bulletin, 2008, 17 (Autumn), 12–16.

- Sen, A.K. Quality of life: India vs. China. The New York Review of Books, 2011, 58, 44-47. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2011/05/12/quality-life-india-vs-china/ [accessed Feb 2, 2025].

- Alves, J. L. S.,; de Medeiros, D. D. Eco-efficiency in micro-enterprises and small firms: a case study in the automotive services sector. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2015, 108, 595-602.

- Hall, J.; Collins, L.; Israel, E.; Wenner, M.. The missing bottom line: microfinance and the environment. Green microfinance LLC, document prepared for The SEEP Network Social Performance Working Group Social Performance MAP, 2008. http://www.microfinancegateway.org/p/site/m/template.rc/1.9.34581/, [accessed Feb 12, 2025].

- Shahidullah, A. K. M.; Haque, C. E. Green microfinance strategy for entrepreneurial transformation: validating a pattern towards sustainability. Enterprise Development & Microfinance, 2015, 26(4), 325-342. [CrossRef]

- Brigg, M. Empowering NGOs: The microcredit movement through Foucault's notion of dispositif. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 2001, 26(3), 233-258. [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Power/knowledge: selected interviews and other writings 1972 –1977, ed., C. Gordon. Pantheon: NY, USA, 1980.

- Villadsen, K. Doing without state and civil society as universals: 'dispositifs' of care beyond the classic sector divide. Journal of Civil Society, 2008, 4(3), 171-191. [CrossRef]

- Deleuze, G. What is a Dispositif? In Michel Foucault philosopher, ed., Amstrong, T.J.; Harvester Wheatsheaf: NY, USA, 1982.

- Silva-Castaneda, L. A; Nathalie, T. Sustainability standards and certification: looking through the lens of Foucault's dispositif. Global networks, 2016, 16(4), 490-510.

- Escobar, A. Imagining a post-development era? Critical thought, development and social movements. Social Text, 1992, 31(32), 20-56. [CrossRef]

- Shahidullah, A. K. M.; Choudhury, M. U. I.; Haque, C.E. Ecosystem changes and community wellbeing: social-ecological innovations in enhancing resilience of wetlands communities in Bangladesh. Local Env. 2020, 25(11-12), 967-984. [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M. Creating a world without poverty: social business and the future of capitalism. Public Affairs: NY, USA, 2007.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).