1. Introduction

Air pollution in China has an impact on both regional and global atmospheric air quality, and PM2.5 is one of the key air pollutants generated (Cai et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019). It is a particulate matter type that is generated during both organic and inorganic combustions (Li et al., 2021). This particulate matter type is a concern worldwide because it has been proven by many studies that it leads to health complications when inhaled(Galea et al., 2013).

As air pollution has become prominent especially in urban settings, there is an increasing demand and advocacy for urban forests establishment in order to combat air pollution (Mitchell & Devisscher, 2022; Nowak & Heisler, 2010). In the guest to deal with air pollution and climate change through urban forestry, the generation of forest wastes (especially leaves and branches) has become unavoidable (Timilsina et al., 2014). These wastes are most of the times burned intentionally or unintentionally either within the urban settlements or outside in order to keep the communities clean or generate energy for individual, family, community, or industries (Khudyakova et al., 2017; Nowak et al., 2019). These combustion processes involves both physical and chemical processes that lead to a transfer of mass and heat (Yadav & Devi, 2018). As further explained by Yadav & Devi, (2018), forest biomass burning contributes 18% of the global aggregated air pollutants emission. Mostly the combustion processes pose health issues to users and their neighbors by compromising the air quality which leads to human health implications (Jiang et al., 2024; Wu et al., 2020). Studies have proven that biomass burning increases the concentration of particulate matter in indoor and outdoor environments in both developed and developing countries(Johnston et al., 2019).

Particulate matter in smokes has become a concern(Adam et al., 2021) in which fine particulate matter (PM2.5) overshadows due to its size and chemical composition. It has been revealed that the composition of PM2.5 has effect on the risk it possess on public health (Fang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2018), and the risk magnitude is affected by the source of the elements and compounds in it (Chatoutsidou & Lazaridis, 2022). Studies on PM2.5 highly focused on inorganic sources of PM2.5 like from industries and transportation sector while biomass sources have gained less attentions (Saliba et al., 2007) though it poses significant health risks to urban settlers. A study done by (Lim et al., 2011) concluded that most of the indoor PM2.5 pollution originate from outdoor processes which includes biomass burning.

On the other hand, the composition of the PM2.5 has gained attention from researchers which is believed to have effect on the its toxicity. For example, a review done by (Jia et al., 2017) further explained that the toxicity of PM2.5 mixed compositions differs greatly from the single ingredients in mixed components. It is therefore important to know the composition of PM2.5 in order to determine its toxicity to human health in urban areas. As revealed by many studies, Pm2.5 contains both metal and none metal elements or compounds in which some are highly reactive while others reactivity are moderate. Among the most studied reactive elements present in abundance in PM2.5 are Calcium (Ca), Potassium (K) (Wang et al., 2018), Sodium (Na) and Phosphorous (P)(Ma et al., 2019; Violaki et al., 2022). These elements are highly reactive with water and carbon which makes them readily available to form compounds when released into the atmosphere. On the other hand, these elements are also among the essential elements needed by plants (de Bang et al., 2021; van Maarschalkerweerd & Husted, 2015) which makes them always available in plant cells. Most of these elements which are essential for plants and found in plant cells as trace elements are released into the environment during biomass combustion (C. Chen et al., 2019; Nzihou & Stanmore, 2013).

Though there is high concern about biomass induced toxic elements effects on both water and air, the type of biomass burning remains key factor to determine the composition of pollutants emitted (Yao et al., 2023).

In the urban settings, many tree species are used for different or similar functions. Some are used for environmental cooling (X. Chen et al., 2019), serving as wind breakers (Podhrázská et al., 2021), provide ecosystem services (Blanusa et al., 2019), and rain water interception (Zabret & Šraj, 2019). Irrespective of the function of any urban forest or tree species, the elements absorbed by urban tree species in the process of cleaning the environments or supporting their growth and functionalities can be released in different forms during combustion processes.

These elements when released during combustion processes affects the quality and purity of our environments which in turn affects the lives of both human and other living things.

This study therefore focuses on analyzing the concentrations, of Sodium (Na), Potassium (K), Phosphorous (P), and Calcium (Ca) in the combustibles [(tree species (conifers and broad-leaf, plant organs (Branches and leaves)] and PM2.5. The directions and strength of the relations that exists between the elements in the combustibles and elements in PM2.5, also the interactions of these elements with PM2.5 were assessed. The tree species which were assessed in this study are Ficus macrocarpa, Michelia x alba, Pinus Thunbergii, Platycladus Orientalis, Araucarii cunninghamii and Mangifera indica. The elements assessed in this study are essential elements needed by plants and have been proven to be constituents of fine particulate matters (PM2.5) generated during biomass combustion. Na, K, P and Ca are all reactive elements which can easily form compounds in the presence of water and/or carbon. The main objectives of this study are to assess: (1) the concentration differences of the elements Na, K, P and Ca in the combustibles (tree species and plant organs) and PM2.5; (2) the relationships that exist between these elements in the combustibles and their concentrations in PM2.5 emitted during combustion; (3) the relationships that exist amongst the elements Na, K, P and Ca within PM2.5 emitted. This will provide information that will promote the setting of innovative strategies to deal with urban forest wastes to minimize it effect on urban air quality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

This research was carried out in Fuzhou city, Fujian Province, China which is geographically located between 25° 15′–26° 39′ north latitude and 118° 08′–120° 31′ east longitude(Jin et al., 2023).

In this study, six (6) urban landscape trees common in Fuzhou urban settlements were selected in which three (3) were conifers and another three (3) were broad-leaf urban landscape tree species. These tree species are Ficus macrocarpa, Michelia x alba, Pinus Thunbergii, Platycladus Orientalis, Araucarii cunninghamii and Mangifera indica.

2.2. Sample Collection and Preparation

The samples were in June, 2024 within the urban setting of Fuzhou city from randomly selected trees of the six tree species. To avoid the effect of soil chemical composition differences and industrial pollution effects, the samples were collected from the same geographical location and away from industrial settings respectively.

Fresh branches (< 10 thick were used) and leaves were directly collected from the trees to avoid its contact with objects that might contaminate it and affect the final result. The samples of branches, leaves, conifers and broad-leaf tree species were placed into different labeled sample bags, closed tightly and transported to the lab. The branches and leaves were assessed in this study because these are wastes frequently generated from urban forests.

In the lab, the samples were then dried at 80 0C (Paul et al., 2024) in an Electric Constant Temperature Blast Drying oven ( Shanghai Jinghong Industry Company Ltd, DHG-9240A) until constant weights were attained.

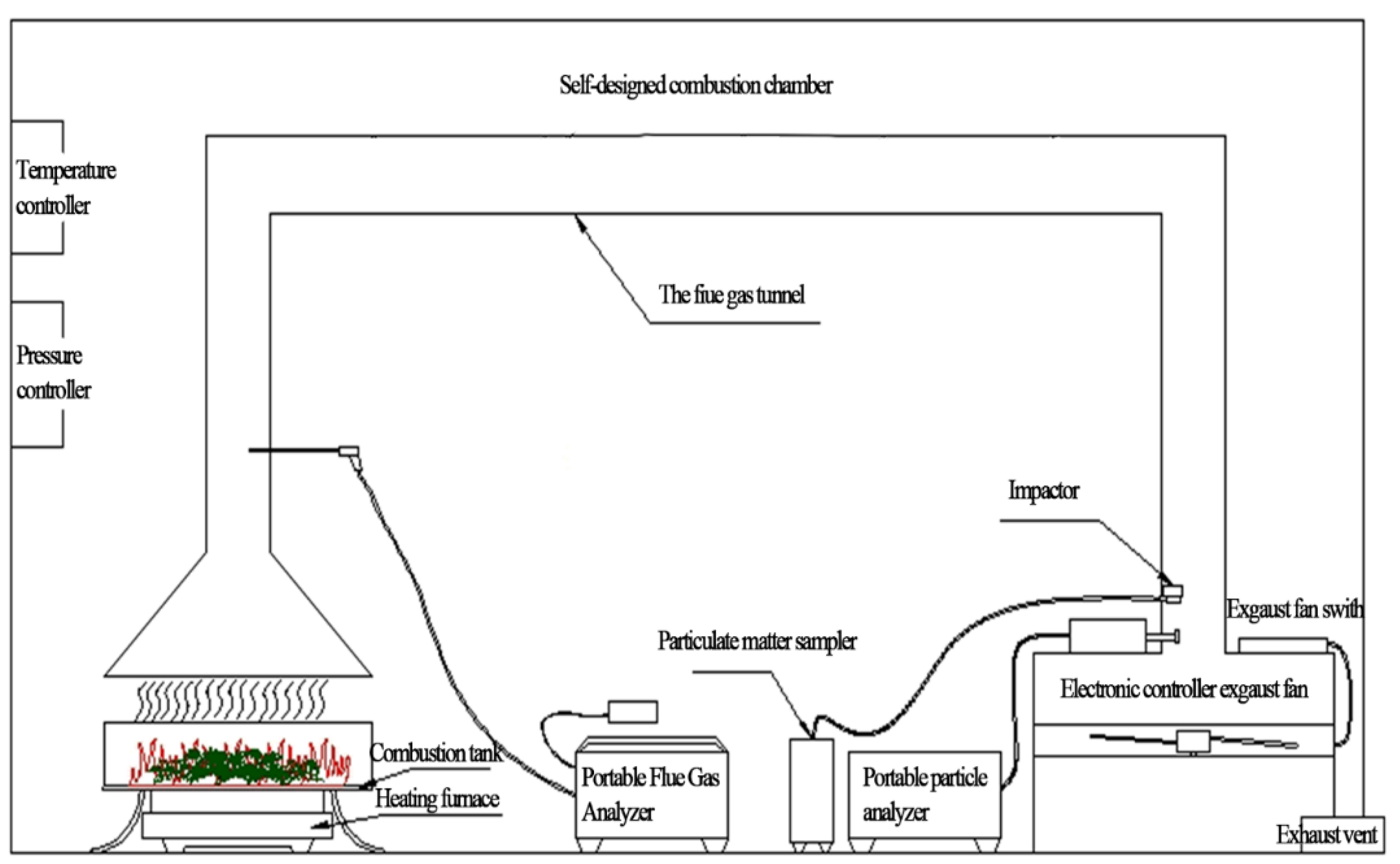

The samples meant for the concentration of the elements in the combustibles where ground using ceramic sample grinder. The samples meant for elemental concentration assessments in PM2.5 were cut into the length of about 5 cm to promote complete combustion. 25 g (weighed using PY-E627, China, Puyan with an accuracy of 0.001g) of each set of samples were simulated in a combustion chamber (

Figure 2) which was set at a temperature of 200

0C before placing the sample. Each sample was burned in flaming and sustained through the use of an oxygen pump which supplies oxygen into the combustion chamber at a rate of 20 % min

-1. Teflon-polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane filters were placed in a USA, SKC-DPS PM sampler to collect PM

2.5 during the combustion process for each sample.

2.3. Samples Testing

For elemental concentration testing in the combustibles, 0.2 g of each ground sample was used, mixed with 10 ml of 30 % Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) and 5 ml of Nitric Acid (HNO3) in a microwave digestion tube. The samples were then placed in an Advanced Microwave Digestion System for 11/2 hours and moved into a cooling chamber for 1/2 an hour. After cooling, the liquid samples were filtrated and 6-8 ml of each sample solution was used to analysis the concentration of Na, K, P and Ca using an ICP~MS Analyzer.

On the other hand, the concentrations of these elements in each sample were determined by extracting each sample in separate vials containing distilled deionized water. The vials were placed in an ultrasonic water bath and shaken with a mechanical shaker for 11/2 hour to extract the ions. The extracts were then filtered through micro-porous membranes with a pore size of 0.45 mm, and the resulting filtrates were tested for metals concentration. An ICP~MS Analyzer was also used to determine the concentration of the metals present in the aqueous extracts of the filtrate.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data collected for this study were analyzed using excel, origin 2024 Pro, and R Studio software. The data preprocessing was done in excel, elemental concentration graphs done in Origin Pro 2024, and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) done in R-Studio.

3. Results

This study was categorized into two sub-headings which are the tree species-based assessments and the tree organs-based assessments. The tree species assessed in this study are the Coniferous and Broad-leaf tree species in the urban settings, while the tree organs assessed are the branches and leaves.

3.1. Composition

3.1.1. Elemental Composition in Combustibles

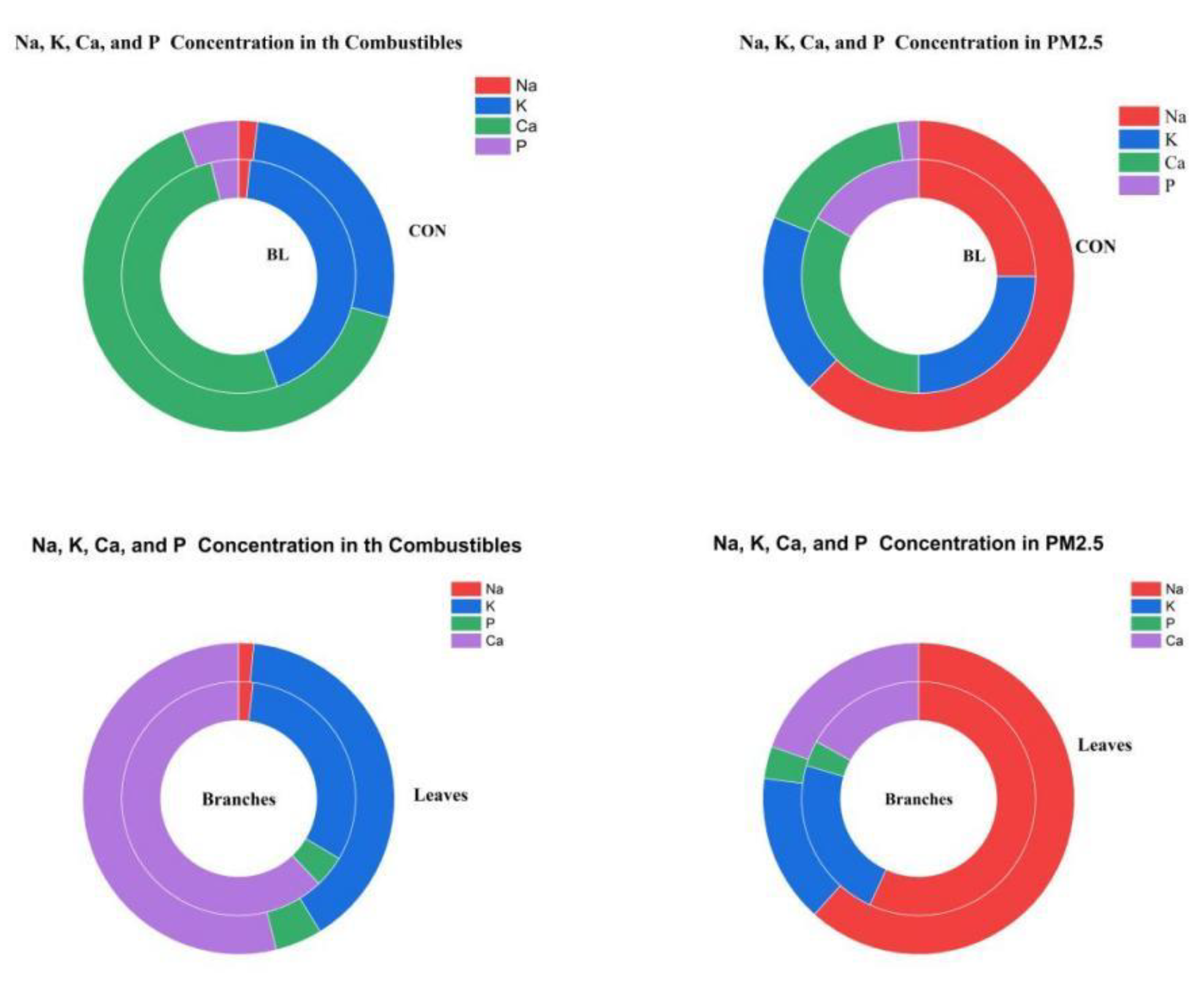

In this study as recorded in

Table 1 and

Figure 3 in this study, it was discovered that urban landscape tree species combustibles assessed had variations in the concentration of Na, K, P, and Ca. There were also variations observed in the concentrations of the elements assessed between

From the data in

Table 1,

Figure 3 it was discovered that the elemental concentration between the Conifers (CON) and broad-leaf (BL) tree species varies. Phosphorous had the highest concentration (CON = 60.56 mg/kg and BL = 65.06 mg/kg) followed by K (CON = 25 mg/kg and BL = 54.27 mg/kg). calcium (Ca) recorded the third highest concentration (CON = 5.45 mg/kg and BL = 4.82 mg/kg) followed by Na (CON = 1.83 mg/kg; BL = 2.00 mg/kg) which is the least concentrated element in both tree species. BL recorded the highest elemental concentration for all the elements studied except for Ca. P and K recording the highly concentrated elements in both tree species.

In the plants organs (Branches and Leaves) there were variations in elemental concentration which showed different trends as compared to the tree species elemental concentration. From the data (

Table 1,

Figure 3), it was revealed that the leaves had the highest elemental concentration as compared to the branches. The leaves had Na, K, P and Ca concentrations as followed: 2.03 mg/kg, 51.41 mg/kg, 6.30 mg/kg and 69.85 mg/kg while the branches recorded 1.80 mg/kg, 28.37 mg/kg, 3.97 mg/kg, and 55.78 mg/kg respectively.

So, there are total differences when the branches and trees of tree species are burned together and when these plant organs are burned independently. P and K recorded to be the first and second highly concentrated elements in the tree species when the combustibles are assessed in bulk while Ca and K were the first and second highly concentrated elements in the combustibles when the branches and leaves are burnt independently. Na on the other hand remained to be low in concentration in both the tree species and organs-based assessments.

3.1.2. Elemental Composition in PM2.5

The concentration of the four assessed elements (Na, K, P and Ca) in PM2.5 were also assessed in order to reveal the emission rate of these elements from the same combustibles of the tree species (CON and BL) and plant organs (Branches and Leaves).

In PM2.5 released from CON, Na, K, P and Ca had 0.86 mg/kg, 0.26mg/kg, 0.23mg/kg and 0.03mg/kg respectively which highlighted Na as highly concentrated element in it. BL PM2.5 had 0.03mg/kg, 0.03mg/kg, 0.04mg/kg and 0.14mg/kg for Na, K, P, and Ca respectively. Na and K had the same level of concentrations in PM2.5 from BL while Ca recorded the highest concentration which is different from the scenario observed in CON PM2.5.

Elemental concentration in the PM2.5 released form the plant organs showed variations where the branches recorded the highest (Na = 0.46mg/kg) and the leaves recorded the least (P = 0.02mg/kg). In the branches, K, P and Ca had 0.19mg/kg, 0.03mg/kg, and 0.14mg/kg respectively. The leaves borne PM2.5 elemental concentration showed different trend although Na (0.42mg/kg) and P (0.02mg/kg) maintained their ranks as the elements with the highest and lowest concentrations respectively. Ca (0.13mg/kg) was recorded as the second highest element concentration while K (0.11mg/kg) recording as the third highest in the PM2.5 from the leaves.

3.2. Elemental Emission Efficiency

In the PM.5 emitted by the tree species (

Table 1); it was observed that Na was efficiently emitted from both conifers and broad-leaf tree species followed by K and Ca respectively as compared to the other elements. 44.99% and 1.5% of the total Na concentration in conifers and broad-leaf tree species were released respectively. 0.55% and 0.41% of Ca total concentration in conifers and broad-leaf tree species were emitted. From the total concentration of K and P (conifers = 1.02% & 0.38%; BL = 0.06% & 0.06% respectively) were released during combustion. These variations showed the role that tree species can play in elemental composition in PM2.5 during biomass combustion processes in urban areas.

A similar scenario was also observed in the emission of the total concentration of these elements in the plant organs (Branches and Leaves) assessed independently. In PM2.5 emitted from the branches during combustion, Na, K, P and Ca released 25.5%, 0.67%, 0.76% and 0.25% of their total concentrations in branches respectively. The leaves also had similar trend with different concentrations. Na (20.69%) recorded the highest followed by P (0.32%), K (0.21%), and Ca (0.19%).

This trend revealed that Na was efficiently released followed by P as compared to the other elements. In overall, Na was efficiently emitted during the combustion processes of both the tree species (CON and BL) and plant organs (Branches and Leaves) as compared to the other elements.

3.3. Structural Equation Modeling to Understand the Direction and Strength of the Underlying Relationships of the Elements.

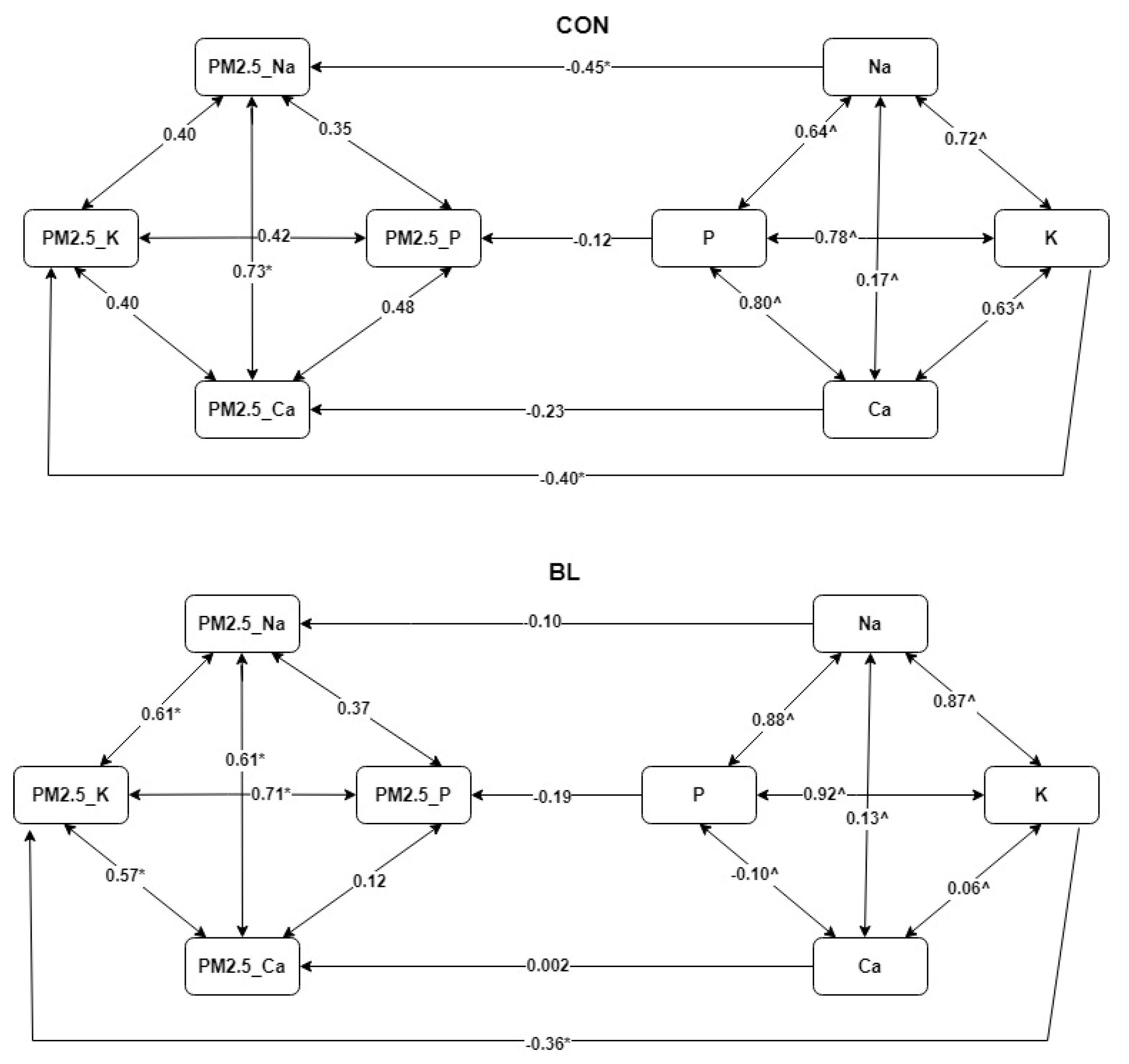

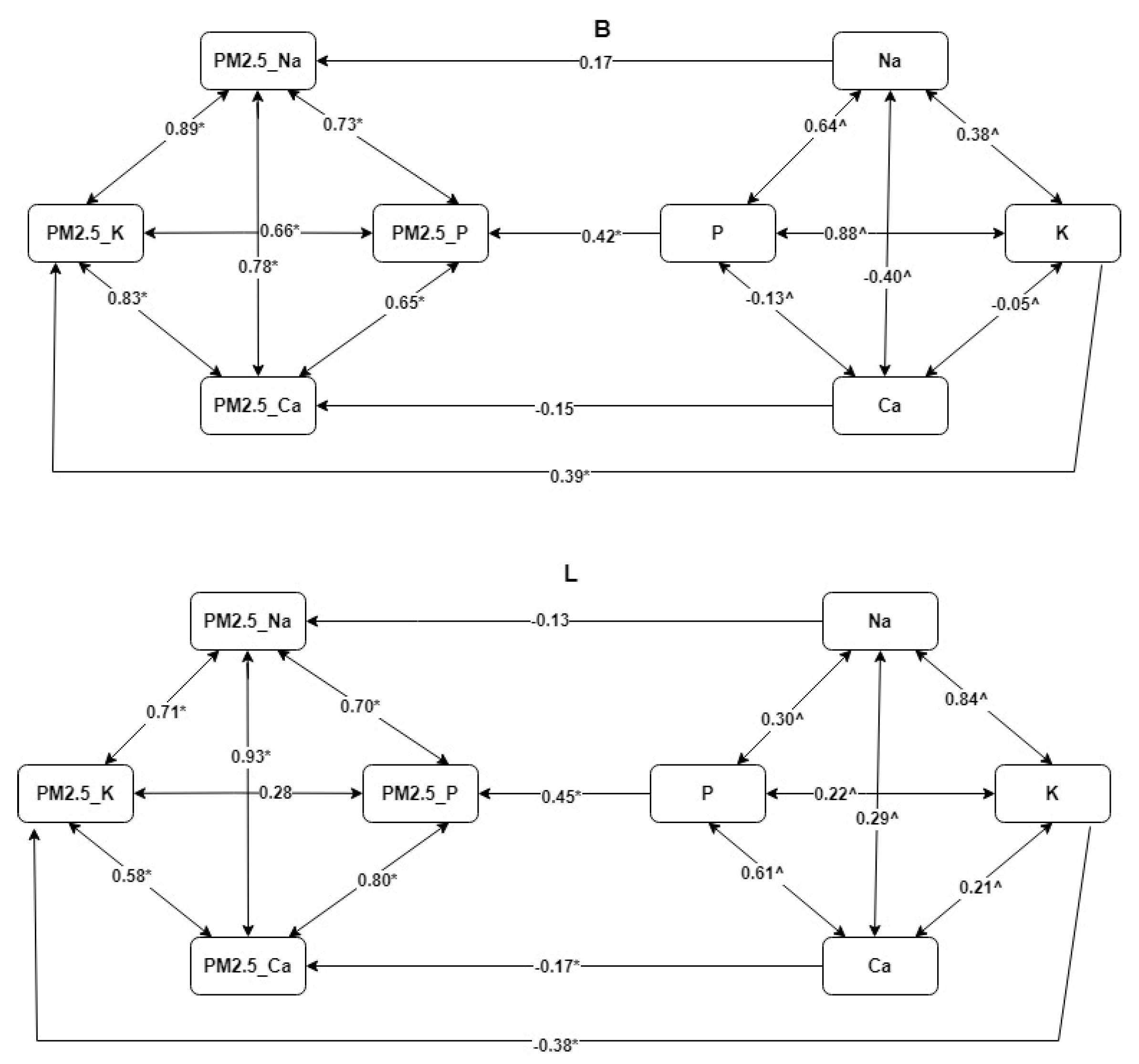

In the structural equation model (SEM) Pathway Analysis results (

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5;

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), the level at which the elements in the combustibles affected the concentration of the same elements in the PM2.5 emitted and the interaction of these elements were observed. This revealed the direction and magnitude of the relationship that existed between the elements in the combustibles and PM2.5, and how these elements correlated. In this study, the standardized estimates (std.all) were used to assess the direction and strength of the relationship that exist amongst the elements and the p-value used to validate the significance of the correlations.

3.3.1. The Relationships of Elements in the Combustibles (Tree Species and Plant Organs) with Their Concentration in PM2.5.

The emission from the coniferous tree species (CON) showed negative connection in the release of elements in the combustibles into PM2.5 emitted but all were insignificant except for Na and K

(Table 2,

Figure 4). The emission of Na, P, K, and Ca to PM2.5 from CON were estimated at a rate of -0.45, -0.12, -0.23, and -0.40 respectively. In the PM2.5 from the broad-leaf tree species (BL), the elements in the combustibles had negative connection to the emission of the same elements in PM2.5 except for Ca, estimated at 0.002 (

Table 3,

Figure 4). The emission of these elements during the combustion process were not statistically significant except for K with an estimate of -0.36. The estimated values for the contribution of Na and P in the combustibles to Na and P in PM2.5 were -0.10 and -0.19 respectively. Different trends were observed in the effects of the elements concentration in the combustibles to the elements in PM2.5 for the plant organs (Branches and Leaves) assessed in this study (

Table 4 and

Table 5;

Figure 5). The link between the elements in the branches and PM2.5 were positive except for Ca (-0.15) which was not statistically significant. Na, P, and K recorded 0.17, 0.42, and 0.39 estimated release in any increase in these elements in the combustibles but P and K relation to counterpart in PM2.5 were significant. The leaves had different trend from the branches in which only P to PM2.5 P relationship was positive and also statistically significant at an estimated increase of 0.45. The rest of the elements had negative estimation where Na, Ca, and K had -0.13, -0.17 and -0.38 respectively and only Na was not statistically significant.

3.3.2. The Relationships of Elements Within the PM2.5 Emitted from the Combustibles (Tree Species and Plant Organs)

The interactions of the elements within the PM2.5 emitted from the combustibles (tree species and plant organs) were further assessed which revealed the direction and strength of their relationships (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). In the PM2.5 from the confers (

Figure 4:

CON), elements positively influenced one another but only the effect of Na to Ca (0.73) was statistically significant vice versa. The weakest interaction recorded for conifers is between Na and P (0.35) after K and Ca (0.40) which is had the same estimated strength with K and Na relationship. The second strongest relationship was between P and Ca (0.48) followed by P and K (0.42) relationship. The broad-leaf tree species had different trend with more statistically significant relationships (

Figure 4:

BL). The strongest relationship was recorded between K and P (0.71) followed by Na and Ca relationship having the same strength with Na and K relationship (0.61). The weakest relationship existed between K & Ca (0.57) after P & Na (0.37) and P & Ca (0.12) relationships.

In the PM2.5 emitted from the plant organs (

Figure 5); different relationship strengths were observed. In PM2.5 from the branches all the elements had statistically significant relationship to one another. Na & K presence in the PM2.5 from the branches strongly influenced each other with an estimated strength of 0.89 followed by K & Ca relationship with an estimate of 0.83 (

Figure 5:

B). The weakest was observed between P & Ca (0.65) followed by relationships between P & K (0.66), Na & P (0.73) and Na & Ca (0.78). In the PM2.5 from the leaves as compared to PM2.5 from the branches, the relationships differ with one insignificant relationship which is between P & K (0.28) though all the relationship were positive (

Figure 5:

L). The strongest relationship was between Na & Ca (0.93) followed by P & Ca (0.80), Na & K (0.71), Na & P (0.70), and K & Ca (0.58) relationships.

4. Discussion

This study presents a detailed assessment of the elemental composition of combustibles from coniferous and broad-leaf tree species in urban settings, with a focus on sodium (Na), potassium (K), phosphorus (P), and calcium (Ca). The findings show distinct variations in the elemental concentrations of these elements between tree species and plant organs (branches and leaves), as well as their influence on PM2.5 emissions.

The study found that broad-leaf trees consistently exhibited higher concentrations of Na, K, and P compared to conifers, with the notable exception of Ca, where conifers demonstrated a slightly higher concentration. This aligns with previous research indicating that broad-leaf species often have greater nutrient accumulations due to their higher growth rates and leaf surface area, which facilitate nutrient uptake from the soil. A study done by (Zhang et al., 2020), explained the ability of conifers and broadleaf tree species differences in partitioning nutrients confirming our findings regarding K and P concentrations. When the organs were assessed, the leaves generally contained higher concentrations of all assessed elements compared to branches, which is consistent with findings from (Vogt et al., 1987; Zhao et al., 2019). Their work suggested that leaves, being the primary site for photosynthesis, accumulate higher nutrient concentrations. The differences between branches and leaves emphasize the critical role that plant organ type plays in elemental profiles and combustion outcomes.

The results reveal that Na was the most efficiently emitted element from both conifers and broad-leaf tree species though more efficient in conifers, suggesting species-specific combustion dynamics. This resilience in elemental emissions during combustion has been noted by (Chatoutsidou & Lazaridis, 2022), who emphasized the influence of source on the elemental makeup of particulate emissions. From trees’ organs (branches and leaves), there were variations in PM2.5 elemental concentrations from branches compared to leaves, particularly for Na and P. The elements concentration in the PM2.5 emitted during combustion for both the tree species and trees’ organs did not reflect substantial link with the concentration of elements in the combustibles. This affirm that there are underlying factors and relationships that further influenced the concentration of these elements in PM2.5, this was also mentioned by (Tao et al., 2013).

In comparison, the emission efficiency from the branches and leaves based on the concentration of the elements in the combustibles, the emission from the branches were more efficient as compared to the leaves. These differences are in line with the study done by (Jia et al., 2017) Which highlighted that the source of PM2.5 has greater role to play in determining its chemical composition. The study uniquely evaluated the emission efficiency of each element during combustion, highlighting that Na and P exhibited the highest rates of emission from both tree species and plant organs, promoting a deeper understanding of combustion dynamics. This resonates with the work by (Neville & Sarofim, 1985; van Eyk et al., 2011), where Na's volatility during combustion processes was emphasized, reinforcing findings in this study.

To further understand the relationships direction and strength that exist among the elements between combustibles and PM2.5 and also with PM2.5, SEM analysis was done. This analysis revealed complex relationships between elemental concentrations in combustibles and PM2.5 emissions, showcasing both positive and negative correlations. The negative relationships for the elements in the combustibles and those in the PM2.5 suggested that increased concentrations in combustibles cannot necessarily lead to proportional elemental increases in PM2.5. This could potentially be linked to the complex interactions observed within the PM2.5 and also the chemical interactions of these elements during combustion could be another cause. The was more statistically significant relationships among PM2.5 elements from broad-leaf trees compared to conifers. From the plant organs, the branches had more significant values but the strongest relationship was recorded in PM2.5 from the leaves. This emphasized the importance of species and organ-specific biochemical behaviors during combustion, a theme echoed in previous literature which claimed variability in elemental interactions according to species types (Sardans et al., 2016) and organ types (Wang et al., 2019).

5. Conclusions

As revealed in this study, distinct differences in elemental concentrations between tree species, with broad-leaf trees showcasing consistently higher levels of Na, K, and P compared to conifers, while conifers recorded higher levels of Ca. This distinction underscores the inherent biological differences between species, particularly their physiological traits that enhance nutrients accumulation. The result further highlighted the Leaves with higher concentrations of all studied elements, confirming their role as vital sites for photosynthesis and nutrient storage.

Notably, Na was found to be the most efficiently emitted element from both conifers and broad-leaf trees though more efficient in conifers, indicating species-specific combustion and elemental release dynamics. The variability in PM2.5 elemental concentrations emitted from branches compared to leaves suggests complexities in how these emissions relate to the initial concentrations in combustibles.

Furthermore, the SEM analysis elucidated the intricate relationships among the elemental concentrations in combustibles and their corresponding concentrations in PM2.5 emitted. It illustrated that the concentrations of elements in combustibles is not the only factor that determines their concentration in PM2.5 emitted, highlighting the influence of underlying biochemical interactions during combustion processes. It was particularly noted that broad-leaf trees exhibited more statistically significant relationships in PM2.5 elemental composition compared to conifers, emphasizing the need to consider both tree species and organ characteristics when dealing with urban biomass-based PM2.5 elemental composition and toxicity.

The highlighted findings in this study underscore the importance of understanding the elemental dynamics and interactions during combustion of urban forests wastes with different tree species, plant organs combustibles and PM2.5 emitted. To develop robust strategies for urban forests with different tree species and plant organs litters management, better understandings are needed on the underlying relationships that exist between elements in the combustibles & PM2.5, and within PM2.5 emitted.

Funding

The study was financially supported by the grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 32171807).

References

- Adam, M. G. , Tran, P. T. M., Bolan, N., & Balasubramanian, R. Biomass burning-derived airborne particulate matter in Southeast Asia: A critical review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 407, 124760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanusa, T. , Garratt, M., Cathcart-James, M., Hunt, L., & Cameron, R. W. Urban hedges: A review of plant species and cultivars for ecosystem service delivery in north-west Europe. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2019, 44, 126391. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S. , Wang, Y., Zhao, B., Wang, S., Chang, X., & Hao, J. The impact of the “Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan” on PM2.5 concentrations in Jing-Jin-Ji region during 2012–2020. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 580, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatoutsidou, S. E. , & Lazaridis, M. Mass concentrations and elemental analysis of PM2. 5 and PM10 in a coastal Mediterranean site: A holistic approach to identify contributing sources and varying factors. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 838, 155980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, C. , Luo, Z., & Yu, C. Release and transformation mechanisms of trace elements during biomass combustion. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2019, 380, 120857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, X. , Zhao, P., Hu, Y., Ouyang, L., Zhu, L., & Ni, G. Canopy transpiration and its cooling effect of three urban tree species in a subtropical city- Guangzhou, China. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2019, 43, 126368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bang, T. C. , Husted, S., Laursen, K. H., Persson, D. P., & Schjoerring, J. K. The molecular–physiological functions of mineral macronutrients and their consequences for deficiency symptoms in plants. New Phytologist 2021, 229, 2446–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J. , Gao, Y., Zhang, M., Jiang, Q., Chen, C., Gao, X., Liu, Y., Dong, H., Tang, S., & Li, T. Personal PM2. 5 elemental components, decline of lung function, and the role of DNA methylation on inflammation-related genes in older adults: results and implications of the BAPE study. Environmental science & technology 2022, 56, 15990–16000. [Google Scholar]

- Galea, K. S. , Hurley, J. F., Cowie, H., Shafrir, A. L., Sánchez Jiménez, A., Semple, S., Ayres, J. G., & Coggins, M. Using PM2. 5 concentrations to estimate the health burden from solid fuel combustion, with application to Irish and Scottish homes. Environmental Health 2013, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.-Y. , Wang, Q., & Liu, T. Toxicity Research of PM2.5 Compositions In Vitro. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2017, 14, 232. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, K. , Xing, R., Luo, Z., Huang, W., Yi, F., Men, Y., Zhao, N., Chang, Z., Zhao, J., Pan, B., & Shen, G. Pollutant emissions from biomass burning: A review on emission characteristics, environmental impacts, and research perspectives. Particuology 2024, 85, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B. , Geng, J., Ke, S., & Pan, H. Analysis of spatial variation of street landscape greening and influencing factors: an example from Fuzhou city, China. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 21767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, H. J. , Mueller, W., Steinle, S., Vardoulakis, S., Tantrakarnapa, K., Loh, M., & Cherrie, J. W. How Harmful Is Particulate Matter Emitted from Biomass Burning? A Thailand Perspective. Current Pollution Reports 2019, 5, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudyakova, G. I. , Danilova, D. A., & Khasanov, R. R. The use of urban wood waste as an energy resource. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2017, 72, 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. , Cheng, T., Shi, S., Guo, H., Wu, Y., Lei, M., Zuo, X., Wang, W., & Han, Z. Evaluating the impacts of burning biomass on PM2.5 regional transport under various emission conditions. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 793, 148481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.-M. , Jeong, J.-H., Lee, J.-H., Moon, J.-H., Chung, Y.-S., & Kim, K.-H. The analysis of PM2.5 and associated elements and their indoor/outdoor pollution status in an urban area. Indoor Air 2011, 21, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. , Tigabu, M., Guo, X., Zheng, W., Guo, L., & Guo, F. Water-Soluble Inorganic Ions in Fine Particulate Emission During Forest Fires in Chinese Boreal and Subtropical Forests: An Indoor Experiment. Forests 2019, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M. G. E. , & Devisscher, T. Strong relationships between urbanization, landscape structure, and ecosystem service multifunctionality in urban forest fragments. Landscape and Urban Planning 2022, 228, 104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, M. , & Sarofim, A. F. The fate of sodium during pulverized coal combustion. Fuel 1985, 64, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D. , & Heisler, G. Air quality effects of urban trees and parks. Research Series Monograph. Ashburn, VA: National Recreation and Parks Association Research Series Monograph. 2010, 44, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, D. J. , Greenfield, E. J., & Ash, R. M. Annual biomass loss and potential value of urban tree waste in the United States. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2019, 46, 126469. [Google Scholar]

- Nzihou, A. , & Stanmore, B. The fate of heavy metals during combustion and gasification of contaminated biomass—a brief review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2013, 256, 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, V. , Pandey, R., M, S., & Mukherjee, P. (2024). Sample collection and digestion methods for elemental analysis of plant. [CrossRef]

- Podhrázská, J. , Kučera, J., Doubrava, D., & Doležal, P. Functions of windbreaks in the landscape ecological network and methods of their evaluation. Forests 2021, 12, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Saliba, N. A. , Kouyoumdjian, H., & Roumié, M. Effect of local and long-range transport emissions on the elemental composition of PM10–2.5 and PM2.5 in Beirut. Atmospheric Environment 2007, 41, 6497–6509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardans, J. , Alonso, R., Carnicer, J., Fernández-Martínez, M., Vivanco, M. G., & Peñuelas, J. Factors influencing the foliar elemental composition and stoichiometry in forest trees in Spain. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 2016, 18, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J. , Zhang, L., Engling, G., Zhang, R., Yang, Y., Cao, J., Zhu, C., Wang, Q., & Luo, L. Chemical composition of PM2.5 in an urban environment in Chengdu, China: Importance of springtime dust storms and biomass burning. Atmospheric Research 2013, 122, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, N. , Staudhammer, C. L., Escobedo, F. J., & Lawrence, A. Tree biomass, wood waste yield, and carbon storage changes in an urban forest. Landscape and Urban Planning 2014, 127, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eyk, P. J. , Ashman, P. J., & Nathan, G. J. Mechanism and kinetics of sodium release from brown coal char particles during combustion. Combustion and Flame 2011, 158, 2512–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Maarschalkerweerd, M. , & Husted, S. Recent developments in fast spectroscopy for plant mineral analysis [Review]. Frontiers in Plant Science. [CrossRef]

- Violaki, K. , Tsiodra, I., Nenes, A., Tsagkaraki, M., Kouvarakis, G., Zarmpas, P., Florou, K., Panagiotopoulos, C., Ingall, E., Weber, R., & Mihalopoulos, N. Water soluble reactive phosphate (SRP) in atmospheric particles over East Mediterranean: The importance of dust and biomass burning events. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 830, 154263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, K. , Dahlgren, R., Ugolini, F., Zabowski, D., Moore, E., & Zasoski, R. Aluminum, Fe, Ca, Mg, K, Mn, Cu, Zn and P in above- and belowground biomass. I. Abies amabilis and Tsuga mertensiana. Biogeochemistry 1987, 4, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Qiao, B., Zhang, L., Yang, F., & Jiang, X. Characteristics and sources of trace elements in PM2.5 in two megacities in Sichuan Basin of southwest China. Environmental Pollution 2018, 242, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. , Wang, J., Wang, L., Zhang, H., Guo, Z., Geoff Wang, G., Smith, W. K., & Wu, T. Does stoichiometric homeostasis differ among tree organs and with tree age? Forest Ecology and Management 2019, 453, 117637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. , Kong, S., Wu, F., Cheng, Y., Zheng, S., Qin, S., Liu, X., Yan, Q., Zheng, H., Zheng, M., Yan, Y., Liu, D., Ding, S., Zhao, D., Shen, G., Zhao, T., & Qi, S. The moving of high emission for biomass burning in China: View from multi-year emission estimation and human-driven forces. Environment International 2020, 142, 105812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, I. , & Devi, N. (2018). Biomass Burning, Regional Air Quality, and Climate Change. In. [CrossRef]

- Yao, W. , Zhao, Y., Chen, R., Wang, M., Song, W., & Yu, D. Emissions of Toxic Substances from Biomass Burning: A Review of Methods and Technical Influencing Factors. Processes 2023, 11, 853. [Google Scholar]

- Zabret, K. , & Šraj, M. Rainfall interception by urban trees and their impact on potential surface runoff. CLEAN–Soil, Air, Water 2019, 47, 1800327. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. , Wu, L., Fang, X., Li, F., Yang, Z., Wang, T., Mao, H., & Wei, E. Elemental Composition and Health Risk Assessment of PM10 and PM2.5 in the Roadside Microenvironment in Tianjin, China. Aerosol and Air Quality Research 2018, 18, 1817–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. , Yajun, C., Hao, G.-Y., Ma, K., Bongers, F., & Sterck, F. Conifer and broadleaved trees differ in branch allometry but maintain similar functional balances. Conifer and broadleaved trees differ in branch allometry but maintain similar functional balances. Tree Physiology 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. , Zheng, Y., Tong, D., Shao, M., Wang, S., Zhang, Y., Xu, X., Wang, J., He, H., & Liu, W. Drivers of improved PM2. 5 air quality in China from 2013 to 2017. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 24463–24469. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H. , He, N., Xu, L., Zhang, X., Wang, Q., Wang, B., & Yu, G. Variation in the nitrogen concentration of the leaf, branch, trunk, and root in vegetation in China. Ecological Indicators 2019, 96, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).