Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

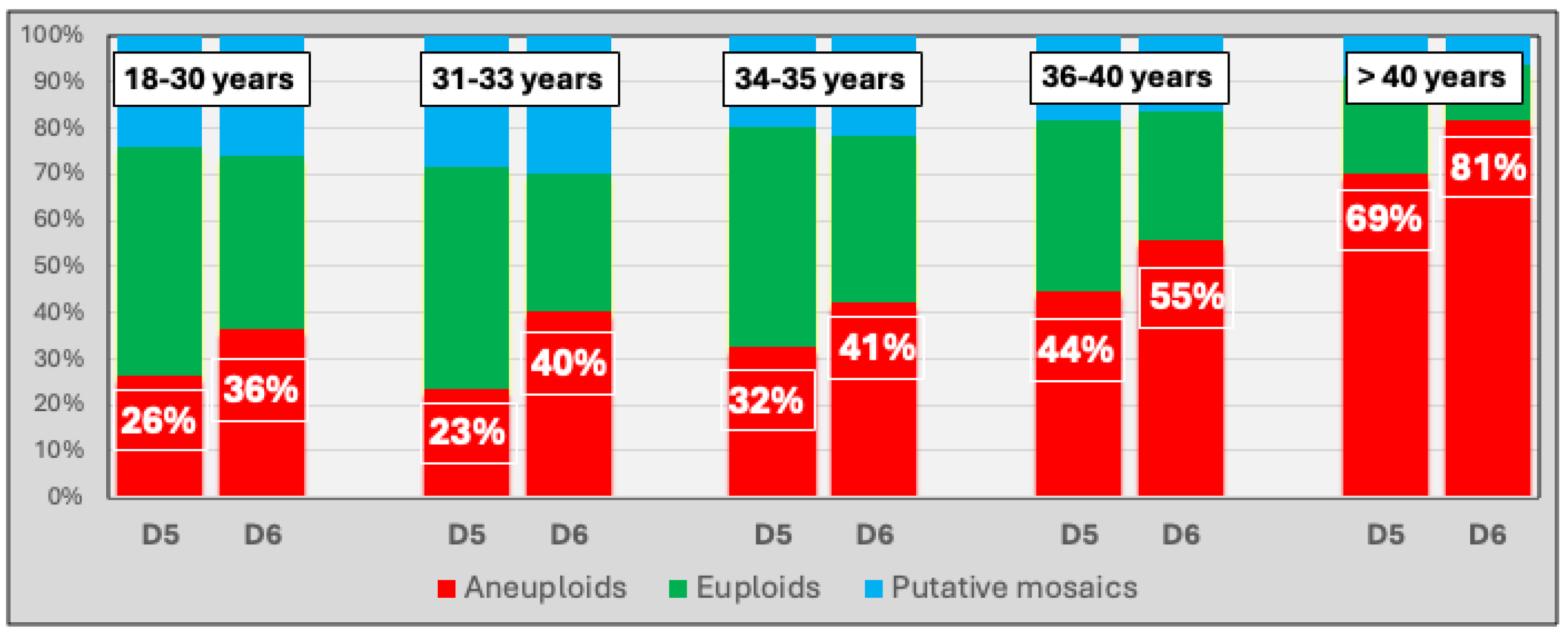

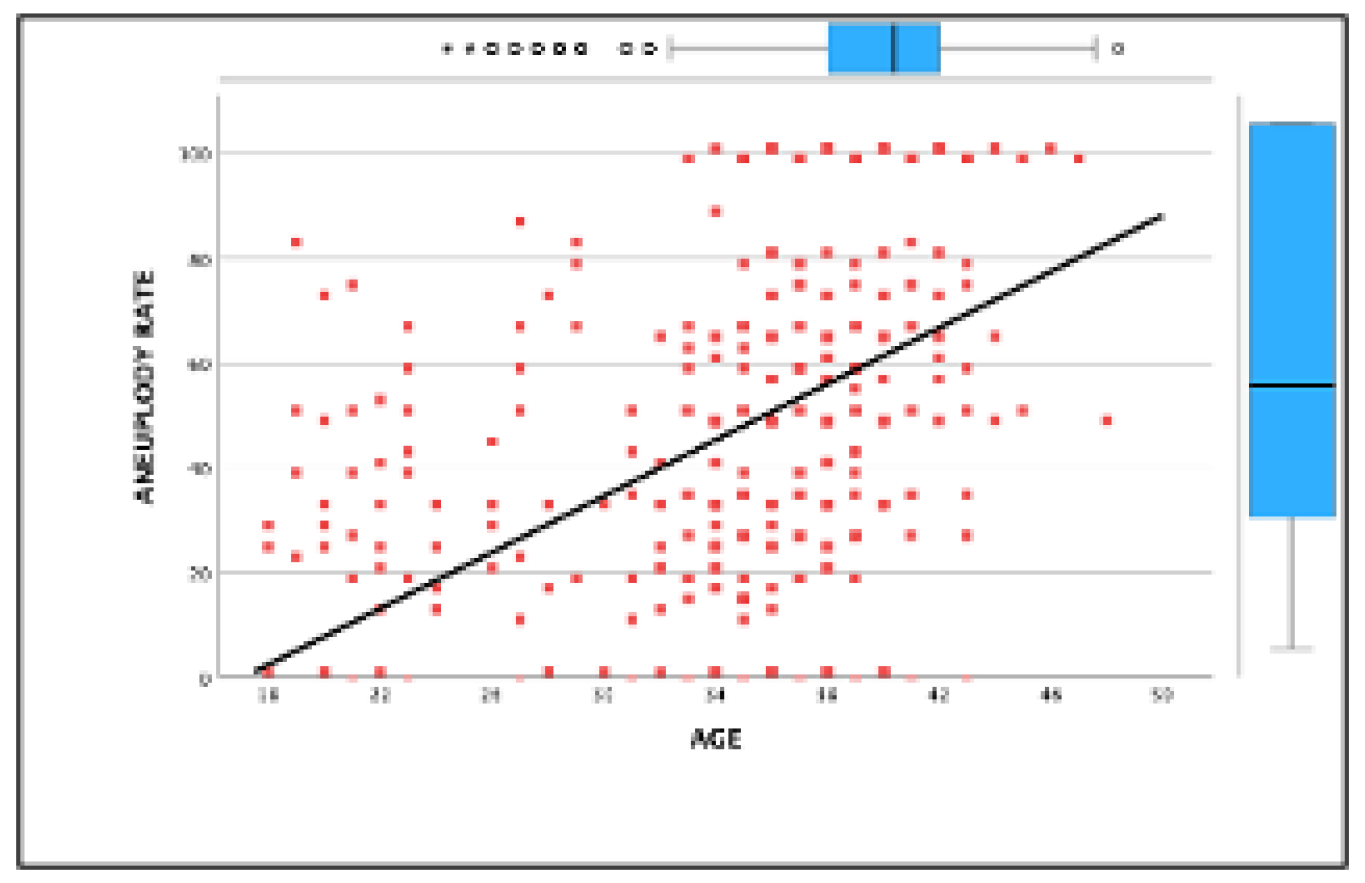

Background and Objectives: This study investigates the impact of maternal age and blastocyst development stage on aneuploidy rates. It evaluates the effectiveness of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) in improving clinical outcomes in in vitro fertilization (IVF). While PGT-A is often recommended for older patients, this study highlights its value across all maternal age groups in optimizing embryo selection. Methods: A retrospective observational study was conducted, analyzing 691 IVF cycles with PGT-A and 2,577 biopsied blastocysts between January 2019 and December 2023 at a single reproductive center. Patients were stratified into five age groups (<30, 31–33, 34–35, 36–40, >40 years), and blastocyst biopsies were performed on days 5 or 6 for genetic testing. Primary outcomes included euploidy and aneuploidy rates, while secondary outcomes assessed embryo availability and pregnancy complications. Results: The overall euploidy rate was 34.5%, declining with age from 43.6% (<30 years) to 15.9% (>40 years), while aneuploidy rates peaked at 75.43% (>40 years). Blastocysts biopsied on day 5 showed higher euploidy rates than on day 6 (40.16% vs. 27.92%, p<0.001). PGT-A cycles demonstrated superior ongoing pregnancy rates compared to cycles without genetic testing, with the most significant benefit observed in patients aged 36–40 (OR: 2.16, 95% CI: 1.07–4.35). However, all age groups benefited from PGT-A in reducing failed transfers due to non-viable embryos. Conclusions: This study underscores the universal utility of PGT-A in IVF, demonstrating its effectiveness in enhancing clinical outcomes and embryo selection, not only among older patients but across all maternal age groups. These findings highlight PGT-A as a valuable tool for optimizing IVF success regardless of patient age.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Ovarian Stimulation and Embryo Procedures

2.3. Laboratory Protocols

2.4. Blastocyst Grading and Biopsy Procedure

2.5. Frozen-Thawed Embryo Transfer Protocol

2.6. Endometrial Preparation

2.7. Embryo Transfer and Pregnancy Outcomes

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study#

Strengths of the Study:

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Attestation statement

- The authors hereby certify that none of the subjects included in this trial were concurrently participating in any other clinical trials.

- Additionally, data about any subjects involved in this study have not been previously published.

- Finally, I confirm that all relevant data will be made available to the journal's editors for review or inquiry upon request.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Abbreviations

| PGT-A | Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies |

| ET | Embryo transfer |

References

- Kang, H.J.; Melnick, A.P.; Stewart, J.D.; Xu, K.; Rosenwaks, Z. Preimplantationgenetic screening: Who benefits? Fertil Steril 2016, 106, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamonkunrot, P.; Samutchinda, S.; Niransuk, P.; Satirapod, C.; Sukprasert, M. The Association between Embryo Development and Chromosomal Results from PGT-A in Women of Advanced Age: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.Q.; Si, C.R.; Yung, S.C.; Hon, S.K.; Arasoo, J.; Ng, S.-C. Analysis of a preimplantation genetic test for aneuploidies in 893 screened blastocysts using KaryoLite BoBs: a single-centre experience. Singap. Med J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viotti, M. Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Chromosomal Abnormalities: Aneuploidy, Mosaicism, and Structural Rearrangements. Genes 2020, 11, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, R.J. Is preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) getting better? How can we know and how do we counsel our patients? Fertil Steril Rep. 2023, 4, 329–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, E.J.; Tao, X.; Ferry, K.M.; Taylor, D.; Treff, N.R.; Scott, R.T. Single embryo transfer with comprehensive chromosome screening results in improved ongoing pregnancy rates and decreased miscarriage rates. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 1217–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, E.J.; Hong, K.H.; Franasiak, J.M.; Scott, R.T. Obstetrical and neonatal outcomes from the BEST Trial: single embryo transfer with aneuploidy screening improves outcomes after in vitro fertilization without compromising delivery rates. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 210, 157.e1–157.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, O.S.; Favetta, L.A.; Deniz, S.; Faghih, M.; Amin, S.; Karnis, M.; Neal, M.S. Potential Costs and Benefits of Incorporating PGT-A Across Age Groups: A Canadian Clinic Perspective. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2024, 46, 102361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellver, J.; Bosch, E.; Espinós, J.J.; Fabregues, F.; Fontes, J.; García-Velasco, J.; Llácer, J.; Requena, A.; Checa, M.A. Second-generation preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy in assisted reproduction: a SWOT analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2019, 39, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushnir, V.A.; Darmon, S.K.; Albertini, D.F.; Barad, D.H.; Gleicher, N. Effectiveness of in vitro fertilization with preimplantation genetic screening: a reanalysis of United States assisted reproductive technology data 2011–2012. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 106, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, R.J. Outcome of in vitro fertilization cycles with preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies: let’s be honest with one another. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112, 1013–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrenetxea, G.; Celis, R.; Barrenetxea, J.; Martínez, E.; Heras, M.D.L.; Gómez, O.; Aguirre, O. Intraovarian platelet-rich plasma injection and IVF outcomes in patients with poor ovarian response: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Hum. Reprod. 2024, 39, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz, I.C.; Gatell, M.C.P.; Vargas, M.C.; Mendive, A.D.; Enedáguila, N.R.; Solanes, M.M.; Canal, B.C.; López, J.T.; Bonet, A.B.; Acosta, M.V.H.d.M. The Embryology Interest Group: updating ASEBIR's morphological scoring system for early embryos, morulae and blastocysts. Med Reprod Embriol Clín 2018, 5, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrenetxea, G.; Romero, I.; Celis, R.; Abio, A.; Bilbao, M. Correlation between plasmatic progesterone, endometrial receptivity genetic assay and implantation rates in frozen-thawed transferred euploid embryos. A multivariate analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 263, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuñez-Calonge, R.; Santamaria, N.; Rubio, T.; Moreno, J.M. Making and Selecting the Best Embryo in In vitro Fertilization. Arch. Med Res. 2024, 55, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.L.E.; de Carvalho, F.A.G. Preimplantation genetic testing: A narrative review. Porto Biomed. J. 2024, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alteri, A.; Arroyo, G.; Baccino, G.; Craciunas, L.; De Geyter, C.; Ebner, T.; Koleva, M.; Kordic, K.; Mcheik, S.; et al. ESHRE guideline: number of embryos to transfer during IVF/ICSI. Hum. Reprod. 2024, 39, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, J.; Ke, X.; Liang, X.; Wang, F. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy optimizes reproductive outcomes in recurrent reproductive failure: a systematic review. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1233962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrenetxea, G.; de Larruzea, A.L.; Ganzabal, T.; Jiménez, R.; Carbonero, K.; Mandiola, M. Blastocyst culture after repeated failure of cleavage-stage embryo transfers: A comparison of day 5 and day 6 transfers. Fertil Steril 2005, 83, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmyttere, S.; De Rycke, M.; Staessen, C.; Liebaers, I.; De Schrijver, F.; Verpoest, W.; et al. Neonatal follow-up of 995 consecutively born children after embryo biopsy for, P.G.D. Hum Reprod 2012, 27, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Jing, S.; Lu, C.F.; Tan, Y.Q.; Luo, K.L.; Zhang, S.P.; et al. Neonatal outcomes of live births after blastocyst biopsy in preimplantation genetic testing cycles: afollow-up of 1,721 children. Fertil Steril 2019, 112, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munné, S.; Kaplan, B.; Frattarelli, J.L.; Child, T.; Nakhuda, G.; Shamma, F.N.; Silverberg, K.; Kalista, T.; Handyside, A.H.; Katz-Jaffe, M.; et al. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy versus morphology as selection criteria for single frozen-thawed embryo transfer in good-prognosis patients: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112, 1071–1079.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiegs, A.W.; Tao, X.; Zhan, Y.; Whitehead, C.; Kim, J.; Hanson, B.; Osman, E.; Kim, T.J.; Patounakis, G.; Gutmann, J.; et al. A multicenter, prospective, blinded, nonselection study evaluating the predictive value of an aneuploid diagnosis using a targeted next-generation sequencing–based preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy assay and impact of biopsy. Fertil. Steril. 2021, 115, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Hong, H.Y.; Zhao, Q.; Nadgauda, A.; Ashrafian, S.; Behr, B.; Lathi, R.B. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy in poor ovarian responders with four or fewer oocytes retrieved. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020, 37, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (years) |

Cycles | Biopsied blastocysts n (per cycle) |

Euploids n (%) |

Aneuploids n (%) |

Mosaics1 n (%) |

N.D.2 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-30 | 75 | 445 (5,93) | 194 (43,60) | 132 (29,66) | 109 (24,49) | 10 (2,25) |

| 31-33 | 42 | 199 (4,72) | 80 (40,20) | 58 (29,15) | 56 (28,14) | 5 (2,51) |

| 34-35 | 142 | 585 (4,12) | 242 (41,37) | 211 (36,07) | 118 (20,17) | 14 (2,39) |

| 36-40 | 288 | 1002 (3,48) | 318 (31,74) | 494 (49,30) | 172 (17,17) | 18 (1,80) |

| >40 | 144 | 346 (2,41 | 55 (15,90) | 261 (75,43) | 25 (7,23) | 5 (1,45) |

| Total | 691 | 2577 (3,73) | 889 (34,50) | 1156 (44,86) | 480 (18,63) | 52 (2,02) |

| Day | Biopsied blastocysts | Euploids n (%) |

Aneuploids n (%) |

Mosaics1 n (%) |

N.D.2 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 5* | 1382 | 555 (40,16) | 533 (38,57) | 264 (19,10) | 28 (2,03) |

| Day 6* | 1182 | 330 (27,92) | 617 (52,20) | 211 (17,85) | 24 (2,03) |

| D7 | 13 | 4 (30,77) | 6 (46,15) | 5 (38,46) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 2577 | 889 (34,50) | 1156 (44,86) | 480 (18,63) | 52 (2,02) |

| Biopsied blastocysts |

Patients n |

Embryo availability for ET N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| 1 | 110 | 70 (63,64) | 40 (36,36) |

| 2 | 162 | 59 (36,42) | 103 (63,58) |

| 3 | 119 | 32 (26,89) | 87 (73,11) |

| 4 | 99 | 9 (9,09) | 90 (90,91) |

| 5 | 66 | 2 (3,03) | 64 (96,87) |

| 6 | 42 | 0 (0,00) | 42 (100) |

| 7 | 29 | 1 (3,54) | 28 (96,55) |

| 8 | 20 | 0 (0,00) | 20 (100) |

| 9 | 20 | 0 (0,00) | 20 (100) |

| 10 | 10 | 0 (0,00) | 10 (100) |

| 11 | 7 | 0 (0,00) | 7 (100) |

| 12 | 4 | 0 (0,00) | 4 (100) |

| 13 | 2 | 0 (0,00) | 2 (100) |

| 14 | 1 | 0 (0,00) | 1 (100) |

| PGT-A (euploid embryos) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) |

ET | PPT n (%)1 |

Gestations n (%)1 |

Ongoing gestations n (%)1 |

Miscarriages n (%)2 |

Ectopic pregnancies n (%)2 |

|

| 18-30 | 21 | 14 (66,67) | 12 (57,14) | 10 (47,62) | 2 (16,67) | 0 (0) | |

| 31-33 | 99 | 62 (62,63) | 58 (58,59) | 47 (47,47) | 10 (17,24) | 2 (3,45) | |

| 34-35 | 128 | 70 (54,69) | 57 (44,53) | 49 (38,28) | 8 (14,04) | 4 (7,02) | |

| 36-40 | 385 | 210 (54,55) | 194 (50,39) | 148 (38,44) | 43 (22,16) | 3 (1,55) | |

| >40 | 84 | 44 (52,38) | 26 (30,95) | 20 (23,81) | 6 (23,08) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 717 | 400 (48,40) | 347 (48,40) | 274 (38,21) | 69 (19,88) | 9 82,59) | |

| PGT-A (transferable embryos) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) |

ET | PPT n (%)1 |

Gestations n (%)1 |

Ongoing gestations n (%)1 |

Miscarriages n (%)2 |

Ectopic pregnancies n (%)2 |

|

| 18-30 | 24 | 14 (58,33) | 12 (50,00) | 10 (41,67) | 2 (16,67) | 0 (0) | |

| 31-33 | 120 | 75 (62,50) | 69 (57,50) | 56 (46,67) | 12 (17,39) | 2 (2,90) | |

| 34-35 | 151 | 83 (54,97) | 67(44,37) | 57 (37,75) | 10 (14,93) | 5 (7,46) | |

| 36-40 | 454 | 244 (53,74) | 225 (49,56) | 169 (37,22) | 49 (21,78) | 4 (1,78) | |

| >40 | 90 | 46 (31,11) | 28 (31,11) | 22 (24,44) | 6 (22,43) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 839 | 462 (47,79) | 401 (47,79) | 314 (37,43) | 79 (19,70) | 11 (2,74) | |

| No PGT-A | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) |

ET | PPT n (%)1 |

Gestations n (%)1 |

Ongoing gestations n (%)1 |

Miscarriages n (%)2 |

Ectopic pregnancies n (%)2 |

|

| 18-30 | 61 | 30 (49,18) | 25 (40,98) | 20 (32,79) | 5 (20,00)) | 0 (0) | |

| 31-33 | 89 | 44 (49,44) | 39 (43,82) | 28 (31,46) | 11 (28,21) | 0 (0) | |

| 34-35 | 39 | 19 (48,72) | 17 (43,59) | 10 (25,64) | 7 (41,18) | 0 (0) | |

| 36-40 | 49 | 19 (38,78) | 17 (34,69) | 11 (22,45) | 6 (35,29) | 0 (0) | |

| >40 | 8 | 2 (25,00) | 2 (25,00) | 1 (12,50) | 1 (50,00) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 246 | 114 (46,34) | 100 (28,46) | 100 (28,46) | 30 (30,00) | 0 (0) | |

| Age (years) |

Euploid* vs. No PGT-A | PGT-a** vs, No PGT-A | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | Δ % | OR (95% CI) | Δ % | ||

| 18-30 | 1,86 (0,68-5,11) | +45,23% | 1,46 (0,55-3,87) | +27,08% | |

| 31-33 | 1,97 (1,08-3,57) | +50,89% | 1,91 (1,07-3,38) | +48,35% | |

| 34-35 | 1,80 (0,81-4,01) | +49,30% | 1,72 (0,78-3,80) | +45,28% | |

| 36-40 | 2,16 (1,07-4,35 | +71,22% | 2,05 (1,02-4,11) | +65,79% | |

| >40 | 2,19 (0,25-18,87) | +90,48% | 2,26 (0,26-19,4 | +95,52% | |

| Total | 1,55 (1,13-2,13) | +34,26% | 1,50 (1,10-2,05) | +31,52% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).