Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

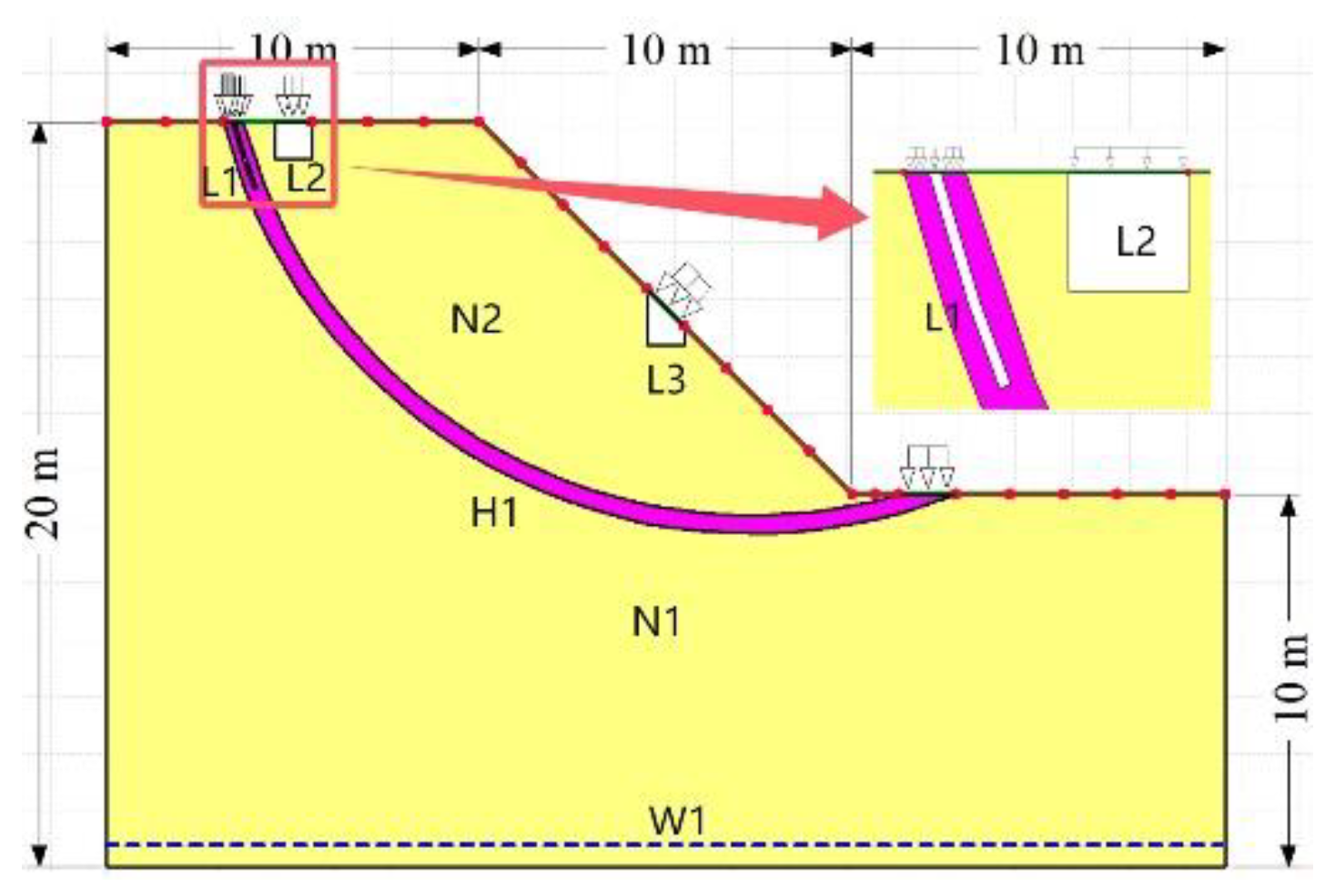

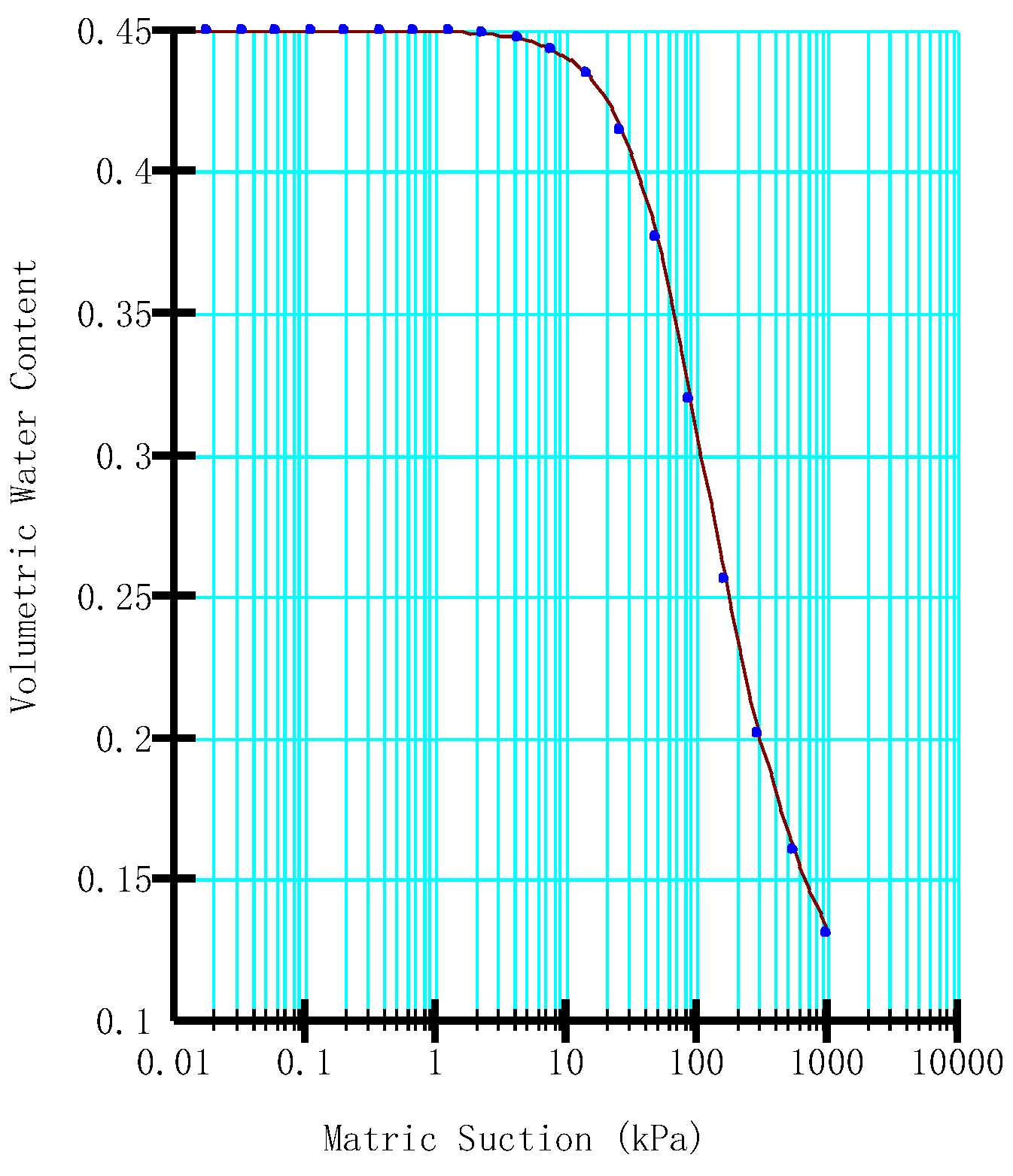

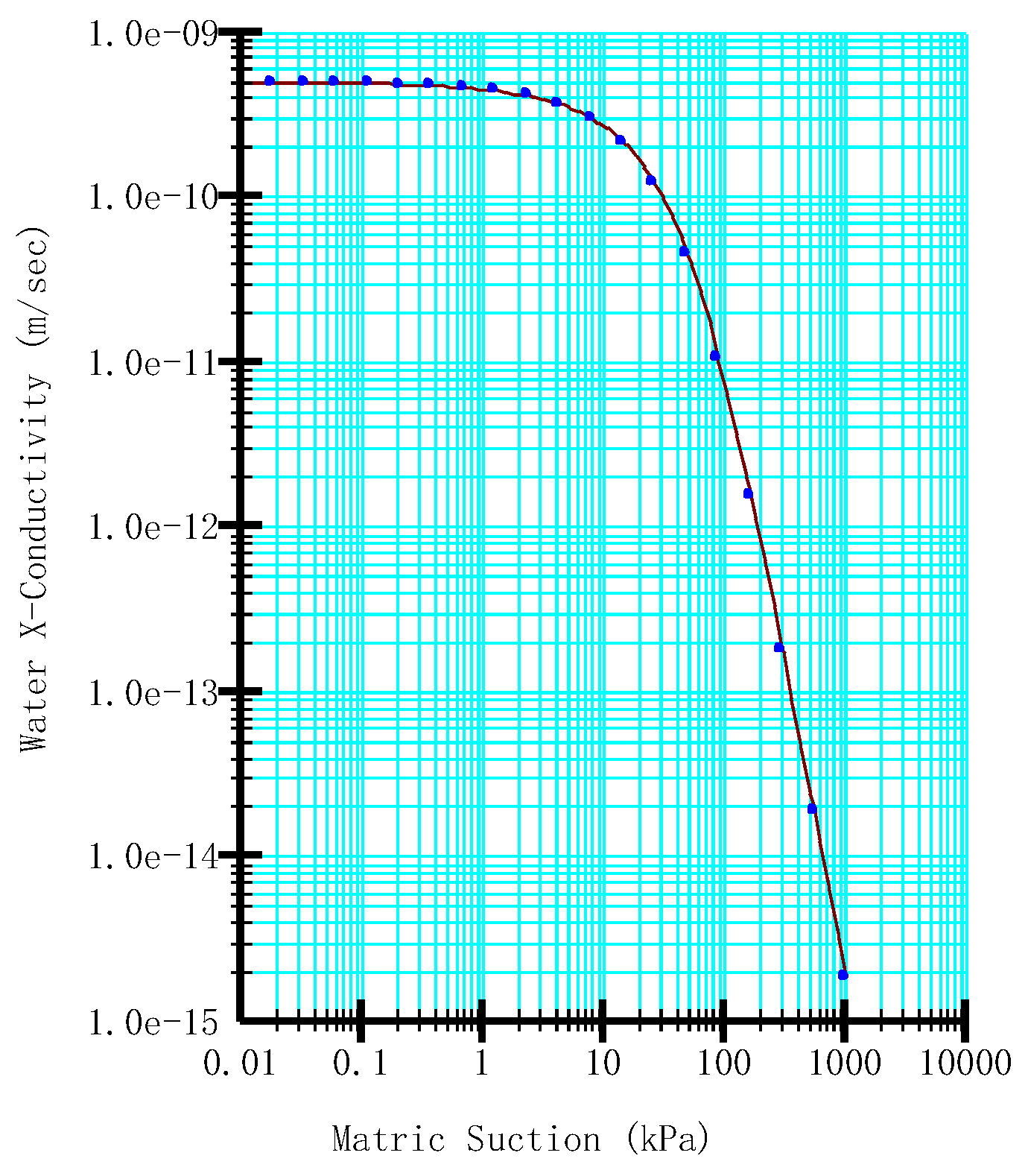

2. Materials and Methods

2.2. XGBoost

2.3. SVR

2.4. PSO Algorithm

2.5. Adaptive Weighting Combination Model

3. Results and Discussion

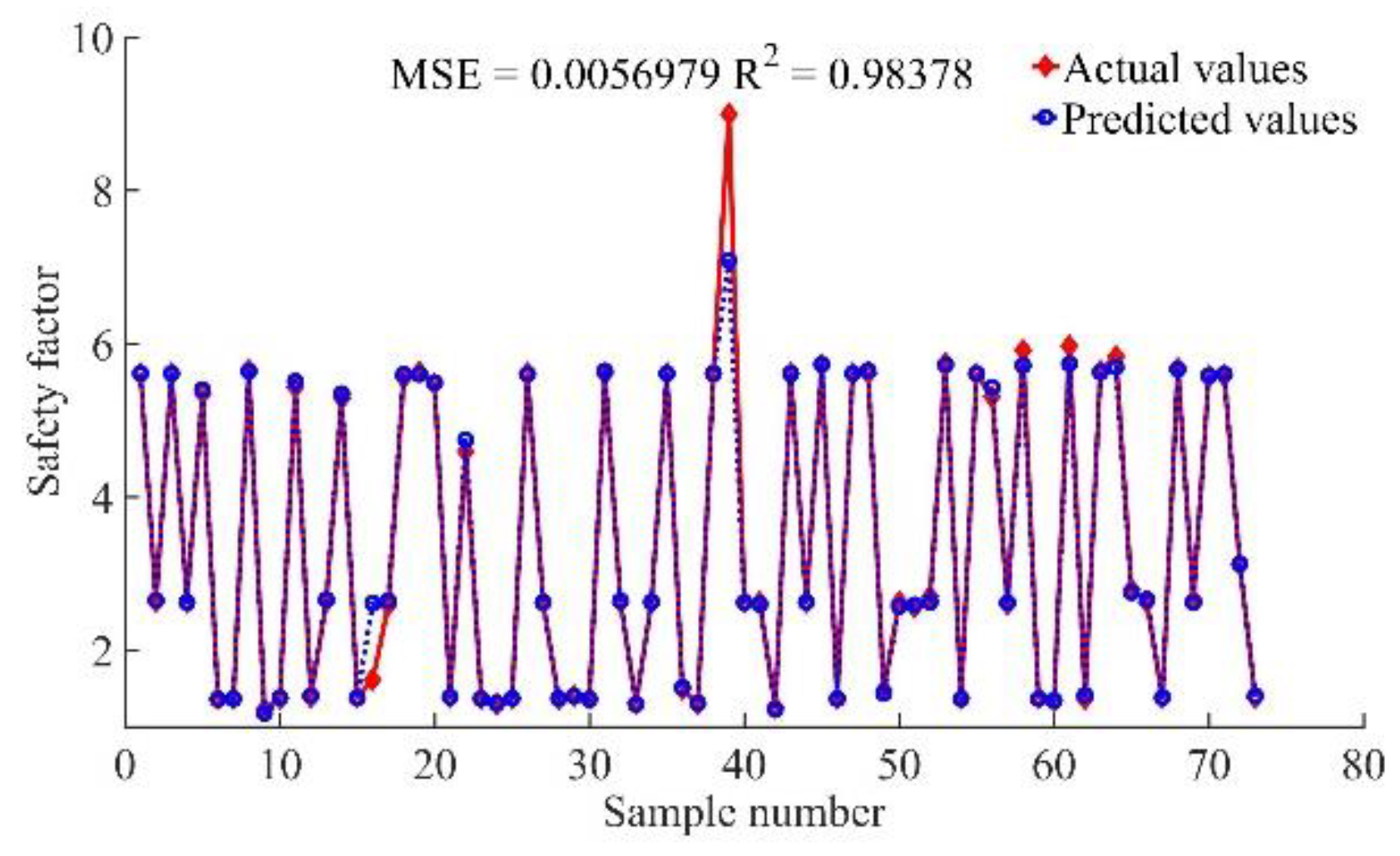

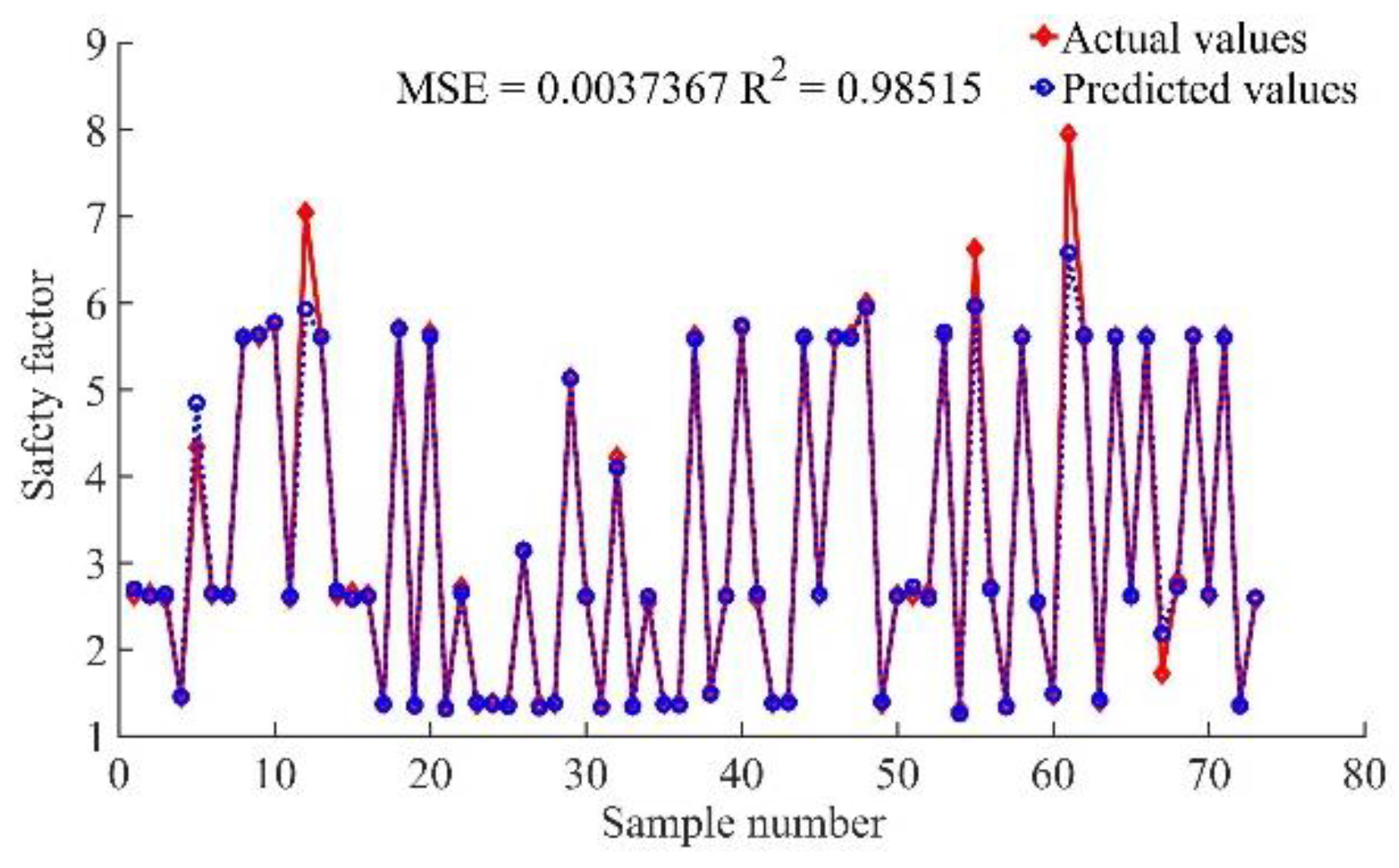

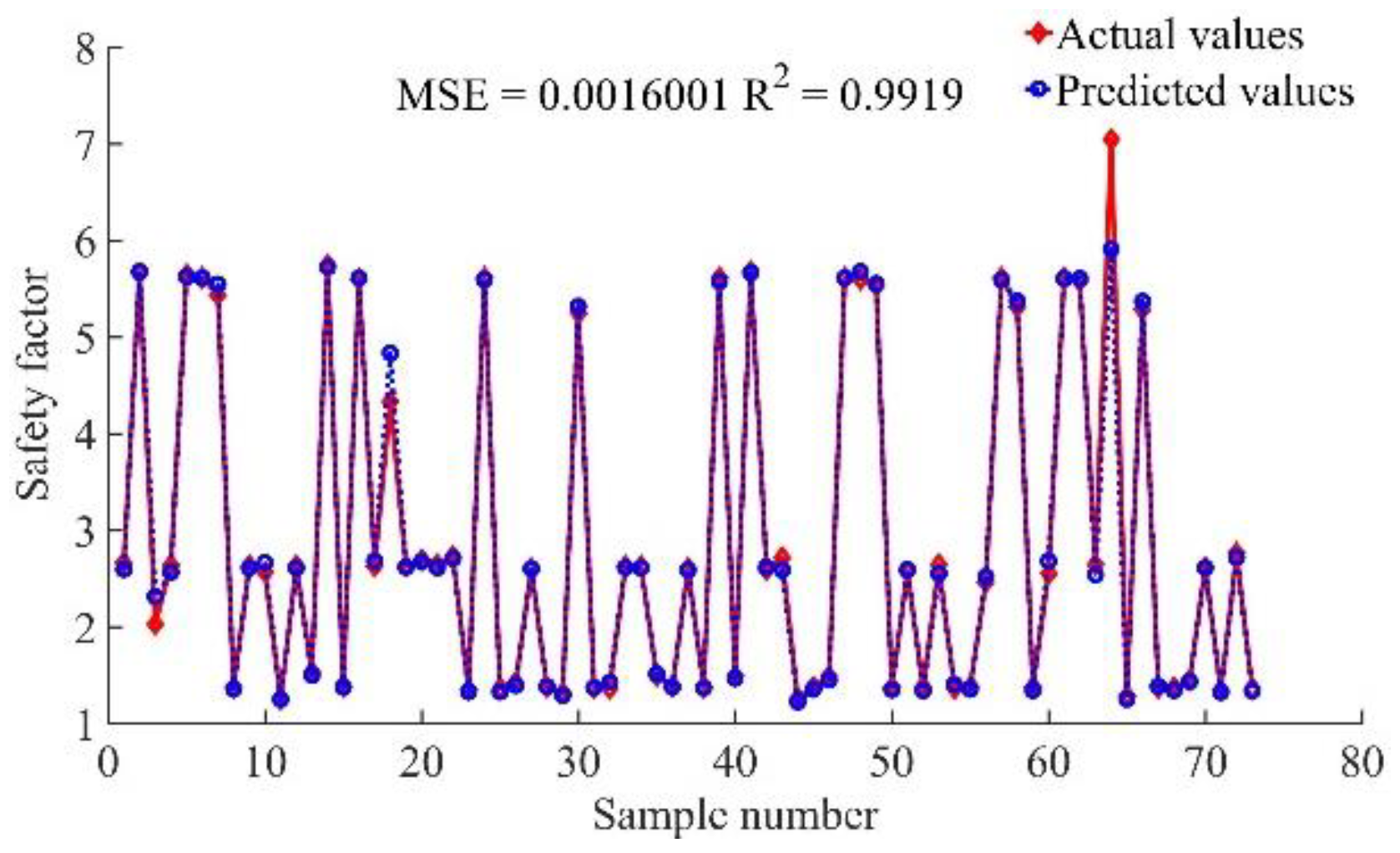

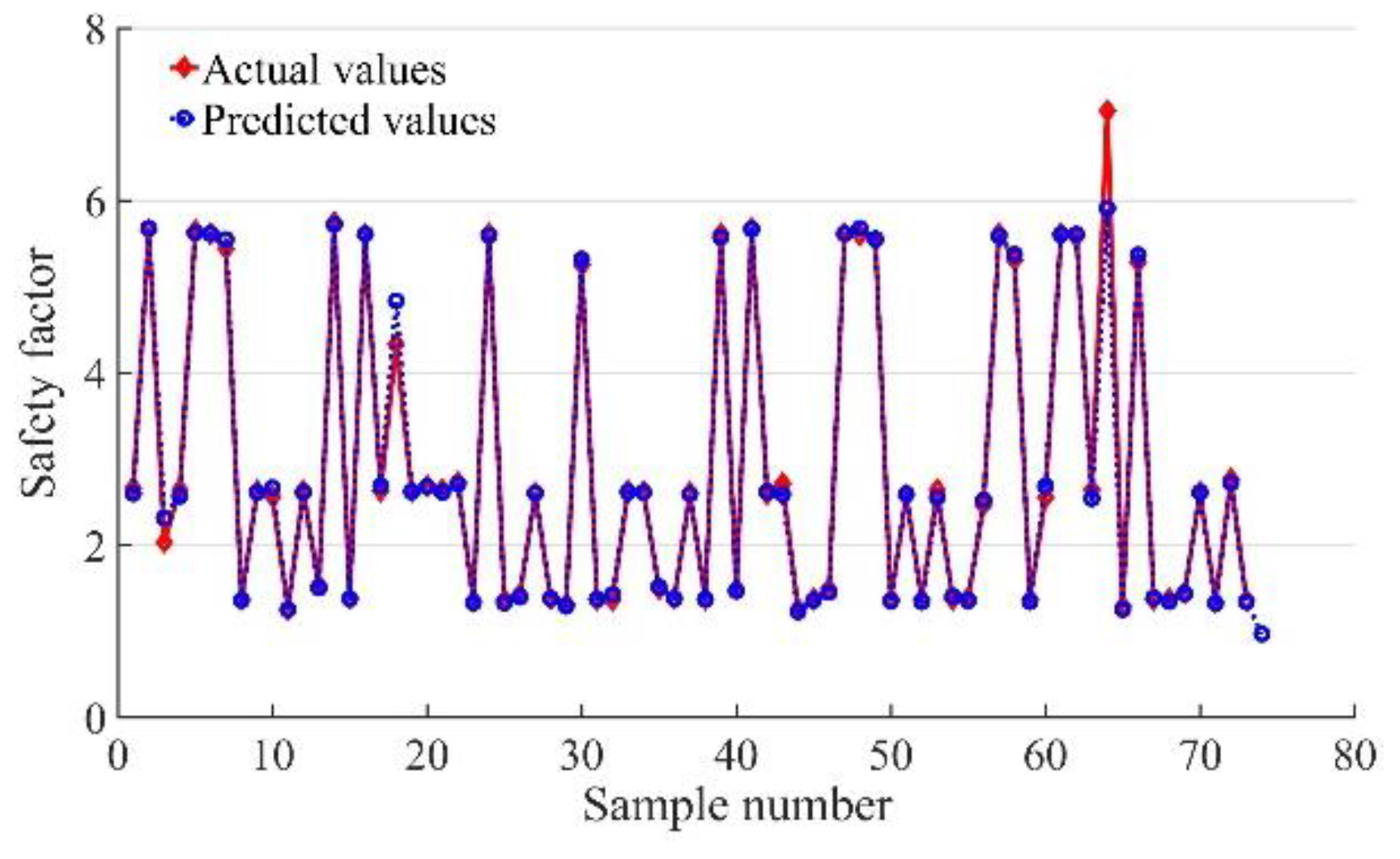

3.1. Comparison of Prediction Results of PSO-SVR, XGBoost, and XGBoost-PSO-SVR

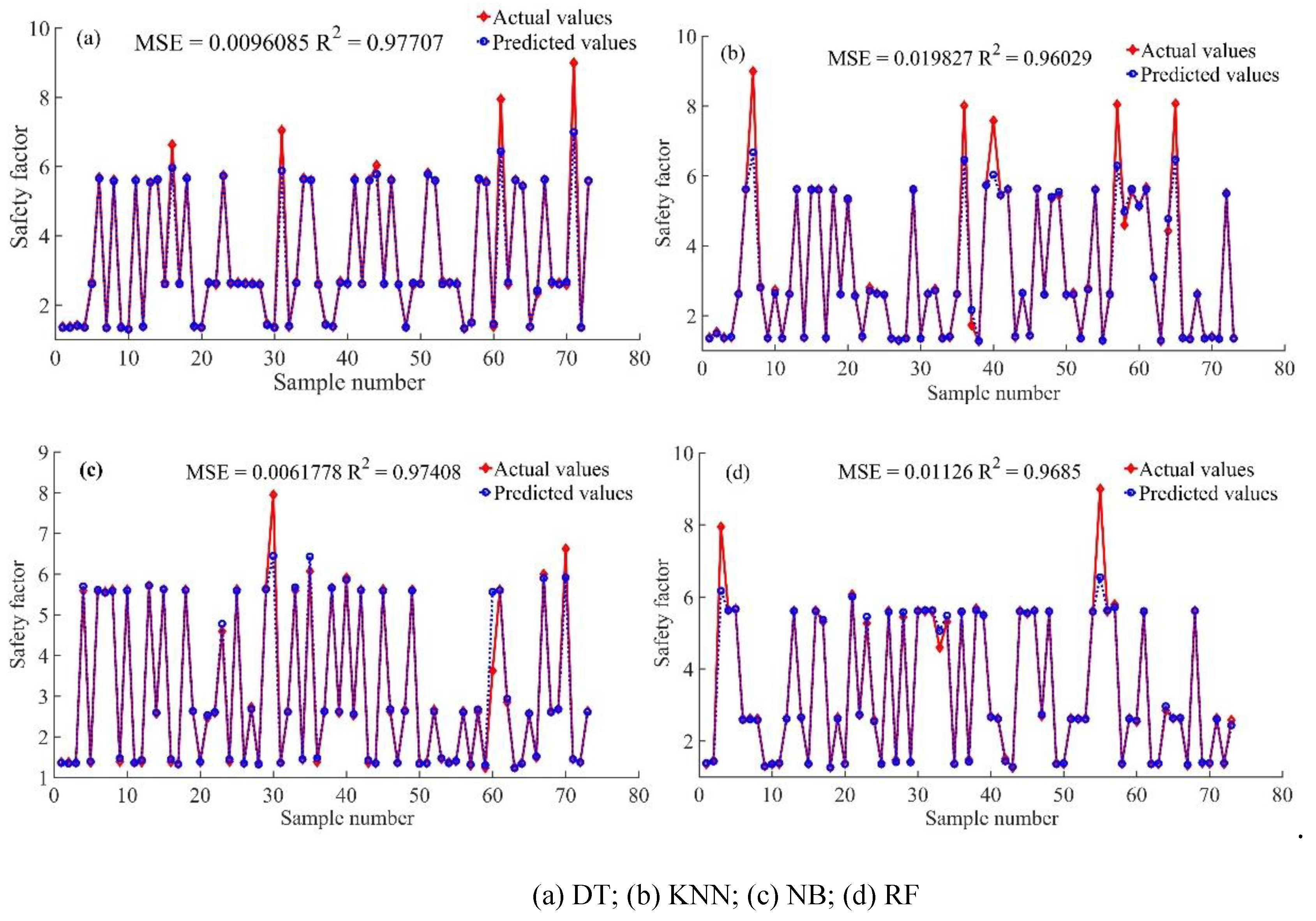

3.2. Comparison of Prediction Results of XGBoost-PSO-SVR with Other Machine Learning Models

4. Justification

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| NB | Naive Bayes |

| RF | Random Forest |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

References

- Yang, X.; Zhu, P.; Dou, X.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ding, B. Resurrection deformation characteristics and stability of Jiangdingya ancient landslide in Zhouqu, Gansu Province. Geological Bulletin of China 2024, 43, 947–957. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G.; Liu, W.; Yan, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Du, G.; Xiong, H.; Wang, M.; Yu, T. Reactivation characteristics and river blocking outburst simulation analysis of Sela ancient landslide in the upper reaches of Jinsha River. Acta Geologica Sinica, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Yin, Y.; Tie, Y.; Sa, L.; Gao, Y.; He, Y.; Zhao, H. Deformation characteristics and reactivation mechanism of giant ancient landslide in Wumeng mountain area: a case study of the Daguan ancient landslide. Chinese Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Frink, N.T.; Pirzadeh, S.Z.; Parikh, P.C.; Pandya, M.J.; Bhat, M.K. Resurrection mechanism of retrogressive ancient landslide under cutting action: an example of an ancient landslide on National Way S206. Science Technology & Engineering 2023, 23, 15002–15009. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio, B.; Guido, A.; Domenico, A.; Piero, F.; Matteo, G.; Gilberto, P. Landslide susceptibility analysis with artificial neural networks used in a GIS environment. Advances in Science, Technology and Innovation 2024, 18, 291–294. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Yin, B. Formation and evolution mechanism of the ancient landslide and stability evaluation of the accumulation body in Jiangdingya, Zhouqu County, Guansu Province. Bulletin of Geological Science and Technology 2024, 43, 266–278. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Cao, J.; Guo, C.; Liu, J.; Yang, Z.; Wei, C.; Wu, R. Developmental characteristics and stability simulation of Yangpo Village large-scale ancient landslides in Minxian County,Gansu Province. Geological Bulletin of China 2024, 43, 1869–1880. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Z.; Guo, C.; Wu, R.; Jian, W.; Ni, J.; Zhang, Y.; Min, Y. Development Characteristics and Stability Evaluation of the Shadingmai Large-scale Ancient Landslide in the Upper Reaches of Jinsha River,Tibetan Plateau. Geoscience 2024, 38, 451–463. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Xiao, Q.; Peng, Y.; Li, C.; Qiu, Q. Stability analysis and engineering control plan optimization for secondary landslide of Gaokanzi in Enshi Xintang. Journal of Shenyang University: Natural Science 2020, 32, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Chang, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, W.; Lu, X.; Liu, H. Mechanistic analysis of loess landslide reactivation in northern Shaanxi based on coupled numerical modeling of hydrological processes and stress strain evolution: A case study of the Erzhuangke landslide in Yan’an. The Chinese Journal of Geological Hazard and Control 2023, 34, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Cheng, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, N.; Zhang, P. Deformation and instability analysis of the transformed secondary landslide—a case of the RK24 landslide in Yuqing-Kaili expressway. Science Technology and Engineering 2020, 20, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Dai, Z.; Jian, W. Cloud model for stability evaluation of recently failed soil slopes based on weight inversion of influencing factors. The Chinese Journal of Geological Hazard and Control 2023, 34, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, X.; Sun, R.; Gu, H.; Fu, Y.; Qiu, Y. Stability analysis of unsaturated soil slopes with cracks under rainfall infiltration conditions. Computers and Geotechnics 2024, 165, 105907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, X.; Liang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X. A case study for analysis of stability and treatment measures of a landslide under rainfall with the changes in pore water pressure. Water 2024, 16, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Ren, W.; Xu, W.; Cai, S.; Li, L. A Modified Method for Evaluating the Stability of the Finite Slope during Intense Rainfall. Water 2024, 16, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Pan, M.; Gao, M.; Min, C.; Li, Y.; Nian, T. Multi-factor risk assessment of landslide disasters under concentrated rainfall in Xianrendong National Nature Reserve in southern Liaoning Province. Bulletin of Geological Science and Technology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wu, R.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J.; Qi, C.; Deng, P.; Li, Y. Development characteristics and reactivation deformation mechanism of the Lumai landslide in Shannan City, Xizang. The Chinese Journal of Geological Hazard and Control 2024, 35, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- LI, T.; Yuan, S.; Xu, J.; Hu, X.; Li, P. Two different types of models for stability assessment of rainfall triggered shallow landslides——discuss with the paper risk assessment of Shallow Loess Landslides. Mountain Research 2023, 41, 916–925. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, A.N.; Medeiros, S.; Allan, E.; Santos, D.S.; Denise, D.F. Assessment of mine slopes stability conditions using a decision tree approach. REM - International Engineering Journal 2023, 76, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Abdessamad, Jari1. ; Achraf, K.; Soufiane, H.; Elmostafa, B.; Sabine, M.; Amine, J.; Hassan, M.; Abderrazak, E.; Ahmed, B. Landslide susceptibility mapping using multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM), statistical, and machine learning models in the Aube Department, France. Earth 2023, 4, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feezan, A.; Tang, X.; Qiu, J.; Piotr, W.; Mahmood, A.; Irfan, J. Prediction of slope stability using Tree Augmented Naive-Bayes classifier: modeling and performance evaluation. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering 2022, 19, 4526–4546. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Cui, Y.; Xu, C.; Ma, S. Application of coupling physics–based model TRIGRS with random forest in rainfall-induced landslide-susceptibility assessment. Landslides 2024, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossat, E.; Aristidi, E.; Azouit, M.; Vernin, J.; Agabi, A.; Trinquet, H. Landslide susceptibility evaluation model based on XGBoost. Science Technology & Engineering 2022, 22, 10347–10354. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.K.; Pani, S.K.; Padhy, S.; Dash, S.; Acharya, A.K. Application of machine learning models for slope instabilities prediction in open cast mines. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering 2023, 11, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, F.; Li, P.; Zhan, T.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y. Risk prediction model of collapse and rockfall based on XGBoost and its application in highway engineering in complex mountain area. Transportation technology and management 2024, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Hou, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Sun, G. Slope displacement prediction using MIC-XGBoost-LSTM model. China Journal of Highway and Transport 2024, 37, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W.; Yang, X.; Feng, Y.; Yang, L.; Wei, J. Slope deformation prediction of SSA-SVR model based on GNSS monitoring. Safety and Environmental Engineering 2024, 31, 160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Ma, L.; Ren, K.; Wang, X. Slope stability coefficient prediction and variable analysis based on Support Vector Machine. Journal of Water Resources and Architectural Engineering 2023, 21, 172–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Xiong, J.; Xing, H.; Ning, X. Research on carbon emission prediction method of expressway construction based on XGBoost-SVR combined model. Journal of Central South University (Science and Technology) 2024, 55, 2588–2599. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Y.; Cui, X.; Cui, J. Deformation prediction of open-pit mine slope based on ABC-GRNN combined model. Coal Geology & Exploration 2023, 51, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. Study on stability prediction of high cutting slope based on GM-RBF combination model. Building Structure 2021, 51, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H. Study on instability mechanism of gently inclined soil slope and treatment method of gravel-blind ditch. Southwest University of Science and Technology 2021.

- Ren, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, N.; Wu, R.; Liu, X. Mobilized strength of sliding zone soils with gravels in reactivated landslides. Rock and Soil Mechanics 2021, 42, 863–873. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K. Stability prediction of reservoir slope based on GWO-XGBoost-SHAP. Sichuan Water Resources 2024, 45, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Hou, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Sun, G. Research on slope displacement prediction based on MIC-XGBoost-LST model. China Journal of Highway and Transport 2024, 37, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J.; Wei, X.; Wang, F. Slope reliability analysis based on MABC-SVR. Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology (Natural Science Edition) 2020, 52, 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Dai, S.; Zheng, J. Subsidence prediction of high-fill areas based on InSAR monitoring data and the PSO-SVR model. The Chinese Journal of Geological Hazard and Control 2024, 35, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Pei, H.; Song, H.; Zhu, H. Prediction of slope displacement based on PSO-SVR-NGM combined with Entropy Weight Method. Journal of Engineering Geology 2023, 31, 949–958. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE Service Center. Proc IEEE int Conf on Networks. IEEE, NJ. 1995, 1942-1948.

- Eberhart, R.; Kennedy, J. A new optimizer using particle swarm theory. Nagoya: Mhs95 Sixth International Symposium on Micro Machine & Human Science. IEEE 1995, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Li, Y.; Shan, C.; Xue, X.; Yang, H. Research on slope stability based on improved PSO-BP neural network. Journal of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Engineering 2023, 43, 854–861. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, M.; Wang, P.; Liang, J.; Guo, D. Slope stability analysis model based on PSO-RVM. Science Technology and Engineering 2023, 23, 8370–8376. [Google Scholar]

| Group | H /m |

β /(︒) |

c /kPa |

φ /(︒) |

γ /(kN·m-3) |

Tr /d |

Ir /(mm·d-1) |

Dm /m |

Lm /m |

St /% |

Sf /% |

| Ⅰ | 5 | 22.5 | 79.5 | 17.25 | 17.0 | 1 | 10 | 0.05 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| Ⅱ | 10 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| Ⅲ | 15 | 67.5 | 50.5 | 15.75 | 18.0 | 3 | 50 | 0.15 | 3 | 15 | 15 |

| Combination |

H /m |

β /(︒) |

c /kPa |

φ /(︒) |

γ /(kN·m-3) |

Tr /d |

Ir /(mm·d-1) |

Dm /m |

Lm /m |

St /% |

Sf /% |

| 1 | 7.5 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| 2 | 8.0 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| 3 | 8.5 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| 4 | 9.0 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| 5 | 9.5 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| 6 | 10.0 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| 7 | 10.5 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| 8 | 11.0 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| 9 | 11.5 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| 10 | 12.0 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| 11 | 12.5 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| 12 | 10.0 | 56.25 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| ∙∙∙ | ∙∙∙ | ∙∙∙ | ∙∙∙ | ∙∙∙ | ∙∙∙ | ∙∙∙ | ∙∙∙ | ∙∙∙ | ∙∙∙ | ∙∙∙ | ∙∙∙ |

| 120 | 10.0 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 12 |

| 121 | 10.0 | 45 | 65 | 16.50 | 17.5 | 2 | 25 | 0.10 | 2 | 10 | 12.5 |

| Combination | Safety factor | Combination | Safety factor | Combination | Safety factor |

| 1 | 3.120 | 12 | 2.783 | 23 | 2.461 |

| 2 | 2.993 | 13 | 2.726 | 24 | 2.495 |

| 3 | 2.843 | 14 | 2.688 | 25 | 2.528 |

| 4 | 2.847 | 15 | 2.654 | 26 | 2.562 |

| 5 | 2.803 | 16 | 2.641 | 27 | 2.595 |

| 6 | 2.629 | 17 | 2.629 | 28 | 2.629 |

| 7 | 2.459 | 18 | 2.612 | 29 | 2.662 |

| 8 | 2.341 | 19 | 2.602 | 30 | 2.695 |

| 9 | 2.030 | 20 | 2.594 | 31 | 2.728 |

| 10 | 1.867 | 21 | 2.586 | 32 | 2.761 |

| 11 | 1.724 | 22 | 2.579 | 33 | 2.793 |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

| eta | 0.2 | subsample | 0.8 |

| min_child_weight | 1 | colsample_bytree | 0.8 |

| max_depth | 5 | colsample_bylevel | 1 |

| gamma | 0 | alpha | 1 |

| max_delta_step | 0 | scale_pos_weight | 1 |

| Machine learning model | MSE | R2 |

| DT | 0.0096 | 0.9771 |

| KNN | 0.0198 | 0.9603 |

| NB | 0.0062 | 0.9741 |

| RF | 0.0113 | 0.9685 |

| XGBoost-PSO-SVR | 0.0016 | 0.9919 |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

| H /m | 38 | Ir /(mm·d-1) | 31.525 |

| β/(︒) | 32.2 | Dm /m | 0.65 |

| c /kPa | 25 | Lm /m | 2.5 |

| φ/(︒) | 24 | St /% | 20 |

| γ/(kN·m-3) | 18.8 | Sf /% | 10 |

| Tr /d | 4 | - | - |

| Machine learning model | Predicted value | Stability state | Simulation results | Deviation |

| XGBoost-PSO-SVR | 0.966 | Unstable | 0.988 | 0.022 |

| XGBoost | 1.005 | Under stable | 0.017 | |

| PSO-SVR | 0.958 | Unstable | 0.030 | |

| DT | 1.009 | Under stable | 0.021 | |

| KNN | 0.955 | Unstable | 0.033 | |

| NB | 1.024 | Under stable | 0.036 | |

| RF | 1.017 | Under stable | 0.029 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).