INTRODUCTION

As a society which has mastered the mass production of plastics. We have been creating waste at a rate approaching 400 megatonnes of plastic waste per year [

4]. Of all of the plastic waste produced by humans, one of the biggest contributors is PET plastic. This makes up 12% of global solid waste [

5]. Despite PET being easily mass-producible, there are very few cost-effective methods to deal with its waste. With the introduction of new biological recycling methods, recycling PET plastic with enzymes has become a viable method [

1,

2]. To use enzymes to digest plastic a bioreactor is required. Bioreactors are vessels used to facilitate biological reactions using enzymes, bacteria, or other biological systems. A bioreactor is a large system which takes time to build, and needs a lot of optimization before it can be constructed and deployed. This is because bioreactor systems are very costly to maintain. Though the plasmid that produces PET hydrolase is naturally found in

Ideonella Sakaiensis, genetic modification allows this enzyme to be produced by other bacterium as well. We wish to study a strain of genetically modified E. Coli. E. Coli is very easy to work with bacteria because it is resilient and easy to produce. This will allow us to produce a sufficient amount of the enzyme for a short-term bioreactor. We also chose to work with batch-style bioreactors because they are easy to maintain. The results of these experiments will be valuable in the prototyping of future bioreactors based on this method of plastic degradation.

METHODS

Materials:

| -Incubator |

-500mL GL45 bottle |

-Deionized water |

| -Microwave |

-LB broth Dry Powder |

-125ml beakers |

| -Petri dishes |

-Sigma Aldrich Ampicillin |

-Agar LB Broth |

| -Micropipettes |

-Antibacterial soap and wipes |

-Inoculating loops |

| -500ml beaker |

-E. Coli: pET21b(+)-Is-PETase was a gift from Gregg Beckham & Christopher Johnson (Addgene plasmid # 112202 ; http://n2t.net/addgene:112202 ; RRID:Addgene_112202) |

Mettler Scale |

| -Parafilm |

Microscope |

|

Over the course of the 5 weeks, we ran a set of 5 batch-style bioreactors. They contained cultures of our genetically modified E. Coli suspended in liquid luria broth. We submerged plastic strips weighing roughly 0.6 grams into each of the bioreactors. Throughout each of the 4 weeks, we would meet 2-3 days to perform different tasks. These consisted of drying/weighing the plastic strips, cleaning the reactors, remaking the liquid cultures, and overall maintenance.

In the first week of the experiment we cultured 2 LB Agar plates with the E. Coli and the antibiotic ampicillin. It was made at a concentration of 100 µg/mL4. We used 2 plates to give ourselves a contingency plan in case 1 plate failed. Also, it allowed us to see how the 2 cultures affected our results. Over the course of the first week, the bacteria grew to the size as shown below. While it was easy to maintain a clean laboratory environment, it was difficult to maintain sterility. After a week of usage, the Agar plates became contaminated with a fungus. This forced us to replate the LB Agar plates weekly for the rest of the experiment.

Figure 1.

One of the first plates of the genetically modified E.Coli. There are small spots of fungal contamination around the plate.

Figure 1.

One of the first plates of the genetically modified E.Coli. There are small spots of fungal contamination around the plate.

In the second week of the experiment we created our first set of the bioreactors. For the 5 batch-style bioreactors, we created the following experimental setup. They consisted of one bioreactor which would be a control. This was placed in the incubator and had no bacteria present. It was labeled with a C. For the other four, the bioreactors were split into categories. For the first category, two bioreactors would be in incubator conditions and the other two would be in room temperature conditions. This gave them the label I or R. The second category was the LB Agar plate from which the bioreactor would receive their bacteria. Each plate was labeled with a 1 or a 2. These bioreactors were labeled as 1R, 1I, 2R, and 2I. We then cut out five 0.6 grams (± 200 milligrams) plastic strips from a PET plastic bottle. We measured all their weights on a Mettler scale which had a margin of error of 0.1 milligrams. After cleaning out the 125ml beakers used for the bioreactors with alcohol soap, we prepared 500ml of liquid luria broth. This was split equally among the 5 beakers. Finally, we introduced the bacteria from the plates into the bioreactors with an inoculating loop. After creating each bioreactor, we covered them with parafilm and poked a single hole through each bioreactor. This prevented contamination and allowed airflow into the bioreactors. Throughout this week, the bacteria grew as shown. Similarly to the LB Agar plates, the bioreactors became contaminated after a week. This forced us to create fresh bioreactors weekly. The plastic strips were cleaned and dried thoroughly for each new batch in our bioreactors.

Figure 2.

The E. Coli after a week of incubation.

Figure 2.

The E. Coli after a week of incubation.

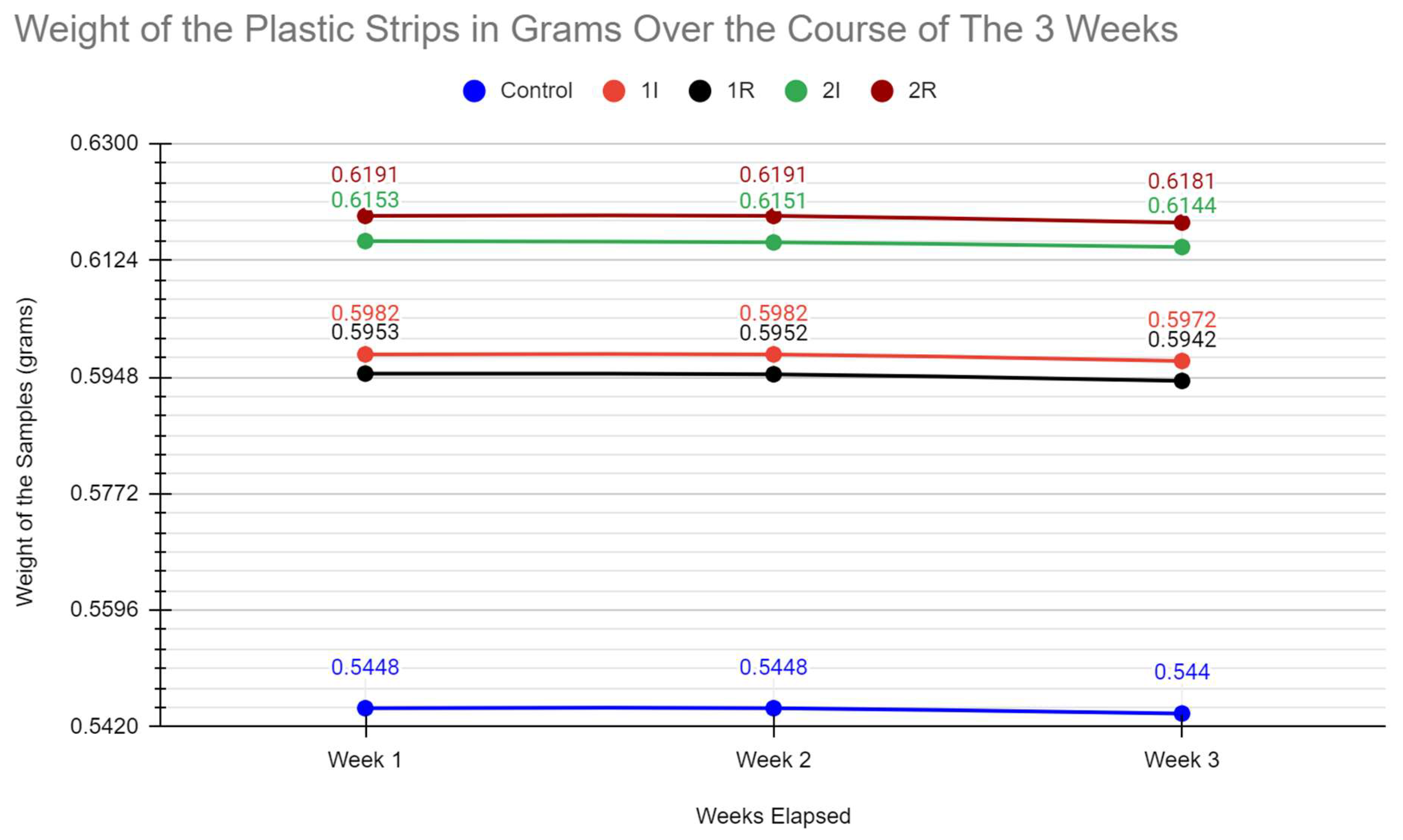

During the 3rd week of our experiments we began weighing each plastic sample and cleaning out the bioreactors. Each plastic sample was removed from its respective bioreactor and then microwaved for a minute. After, it was patted down with a towel to remove residual moisture. They were individually weighed on a scale, and the measurements were recorded. After cleaning all the equipment with alcohol soap and disposing of the liquid culture, we remade each bioreactor and put them back in their growing environments.

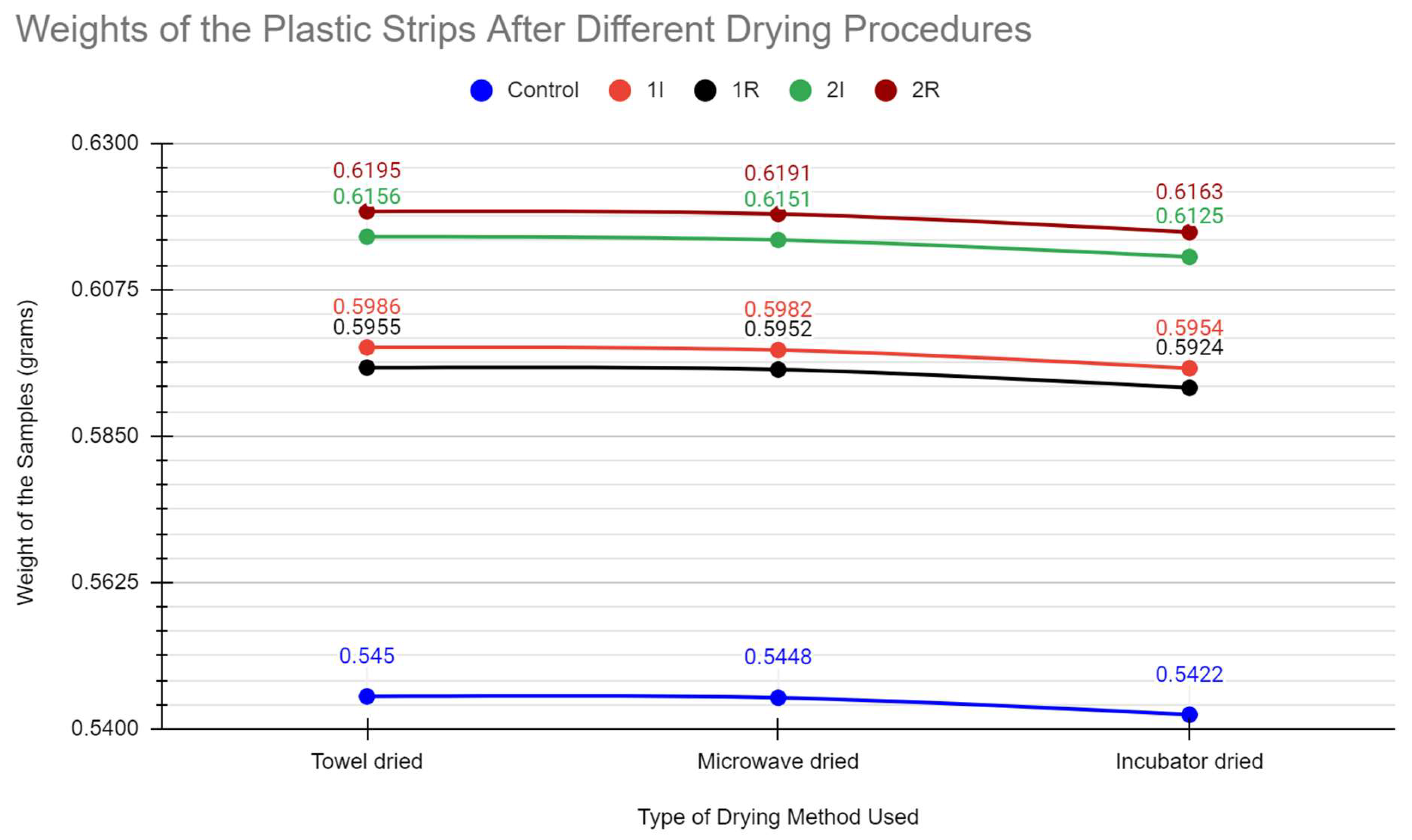

During the 4th week of our experiments, we repeated the same process of weighing and drying each plastic sample. However, comparing the weights of the prior 2 weeks, we realized the increased porosity of the plastic samples would increase the water weight of them as the enzymes digested the plastic. To see if this created a significant enough extra variable, we performed a set of 3 different drying methods and weighed the plastic samples after each method. We first patted them down, microwaved them for a minute, and then we left the plastic samples in the incubator to dry for a day. Before we finished the day and remade the bioreactors, we conducted in-vitro staining on our sample of the E. Coli and the contaminant found in our LB Agar cultures. We confirmed the presence of our E. Coli, and an unknown fungus as shown below. We then remade each bioreactor, and put them back in their growing environments.

Figure 3.

The red bacteria is confirmed to be the gram-negative E. Coli. This can be seen from its red coloringby the stainings.

Figure 3.

The red bacteria is confirmed to be the gram-negative E. Coli. This can be seen from its red coloringby the stainings.

Figure 4.

The contaminated areas were confirmed to have a gram-positive organism. We believed this to be some form of fungi.

Figure 4.

The contaminated areas were confirmed to have a gram-positive organism. We believed this to be some form of fungi.

At the final week of testing there was a complication in our incubator. Both LB Agar plates we were using were dried out. Plate 1 was too compromised to recover a clean culture from, so we made a culture called 1’ from the bacterial stock. We were able to rehydrate plate 2 and made a new culture from that plate which we labeled 2’. For this week, we conducted the same tasks as we did during the first week of the experiment. Once we weighed all of the plastic strips, we were finished running the bioreactors. We terminated both cultures and cleaned out all of the equipment with alcohol soap.

RESULTS

The data obtained from the tests appears to show a slow degradation of the plastic. We determined this through the changes in mass for the plastic strips in the bioreactors as compared to the changes in mass for the control. We did not see any major degradation in the plastic strips because of factors such as the low surface area and the slow acting nature of the enzyme. One result which was not expected was the increase in mass upon weighing the plastic strips straight from towel drying. The mass of these pieces would go down to normal after a more thorough drying technique was performed. This also was in conjunction with our observation that the strips which experienced the largest increase in mass also experienced the greatest decrease upon fully drying. These results pointed to porosity as an important variable. The porosity of the plastic pieces would increase their water retention potential. Under this theory, the plastic strips with the greatest porosity were also those which experienced the most enzymatic degradation. The increase in porosity by the enzymatic digestion would complicate our weighing procedure.

Of significant note is the changes to the bioreactor 1I. Plate 1 remained the most pure throughout our experiment. As such, this bacteria had a better ability to produce the PET hydrolase enzyme. Within the incubator, it was expected to thrive and yield the best results in change of mass. However, purely based on the changes in mass from the start to the end, it was beaten by 2I. However, the porosity theory supports 1I being the best bioreactor. Through all the drying procedures, 1I had a greater change in mass compared to 2I. This calls into question whether the mass of 1I could be accurately compared to 2I with the moisture it had accumulated.

DISCUSSION

While we were able to derive pretty significant results from our study, we were very limited in our facilities. The experiment was performed in the closet of a high school biology laboratory with a budget of $500. We did not have access to the types of fabrication technology and testing equipment that the best hold as standard. However, despite our environment, the bioreactors were able to run and degrade the PET plastic. This shows the capabilities of Enzyme based recycling in lower fidelity environments. This means that there is a great possibility for enzyme based recycling in an industrial setting. Even while we were performing our experiment, the field of enzyme-based recycling skyrocketed. Many new microorganisms and enzyme development procedures have been developed. The fact that we were able to find any significant decreases in mass was amazing. Within the low fidelity environment of our lab, it was very unlikely for us to be able to sense any changes. The fact that the changes beat the margin of error for our scale shows the potential of PET hydrolase. It is important for future studies to try using different types of bioreactors which retain the enzymes in the bioreactors. This will allow for a specific amount of the enzyme to be used on a plastic sample. Using this standard will help minimize the effects of variables such as contamination and porosity.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the North Hunterdon Education Fund for providing us the funds to pursue this research project, and Mrs.Gallo for providing us advice and guidance during our experimentation. We would also like to thank Dr.Hal S. Alper for providing us insight and giving us a framework to build our research upon.

References

- Shosuke, Yoshida; et al. ,A bacterium that degrades and assimilates poly(ethylene terephthalate). Science 2016, 351, 1196–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H. , Diaz, D.J., Czarnecki, N.J. et al. Machine learning-aided engineering of hydrolases for PET depolymerization. Nature 2022, 604, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Characterization and engineering of a plastic-degrading aromatic polyesterase. Austin HP, Allen MD, Donohoe BS, Rorrer NA, Kearns FL, Silveira RL, Pollard BC, Dominick G, Duman R, El Omari K, Mykhaylyk V, Wagner A, Michener WE, Amore A, Skaf MS, Crowley MF, Thorne AW, Johnson CW, Woodcock HL, McGeehan JE, Beckham GT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018, 115, E4350–E4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Chamas, Hyunjin Moon, Jiajia Zheng, Yang Qiu, Tarnuma Tabassum, Jun Hee Jang, Mahdi Abu-Omar, Susannah L. Scott, and Sangwon Suh. Degradation rates of plastics in the environment. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2020, 8, 3494–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyathiar P, Kumar P, Carpenter G, Brace J, Mishra DK. Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Bottle-to-Bottle Recycling for the Beverage Industry: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).