1. Introduction

Pouteria campechiana (Kunth), commonly known as canistel, kanisté, and yellow sapote, is a fruit species of the Sapotaceae family that has been valued since pre-Hispanic times in Central America and Mexico for its nutritious fruits, it’s potential in traditional medicine and ornamental [

1]. The fruits of

P. campechiana are globose in shape, yellow when ripe, and contain one to five large seeds. The seeds are oval-shaped with a conspicuous hilum, dark brown in color, and have a shiny appearance [

2]. They are generally propagated by seeds, which germinate within 3 to 6 weeks [

3]. The seeds are recalcitrant, so they should be sown as soon as possible after being extracted from the fruit. Seed viability can be over 90% when fresh but decreases to 14% after 20 days [

5]. They have a high starch content in the endosperm.

P. campechiana [

6] seeds are rich in starch [

2], a polysaccharide that serves as an indispensable energy reserve during germination and is pivotal for the initial development of seedlings [

5].

The study of the microstructure and content of starch granules in

P. campechiana seeds is of relevance for a deeper understanding of the biological processes occurring during germination and for the potential applications of these starches in the food and pharmaceutical industry. Recent research has demonstrated that starches derived from

P. campechiana seeds possess distinctive structural and digestive properties that could be harnessed in the development of functional and health-promoting food additives [

2].

One of the most intriguing findings of the study is the identification of

P. campechiana as an unconventional and underutilized starch source, yet one that possesses properties that can be exploited in industry [

6]. Recent studies have reported the structural properties of starch isolated from both the pulp and seeds of immature fruit. This starch displays textural, physicochemical, and plasticizing characteristics that distinguish it from other commonly utilized starches [

7]. However, the relationship between germination and changes in microstructure and starch granule content has not yet been evaluated. Despite the importance of starch in germination, there is a lack of studies on the structural and starch content changes in

P. campechiana during the seed germination process. This gap in knowledge limits the ability to develop efficient strategies for seed conservation and their potential in the industry. It has been proposed that

P. campechiana seed starch may have potential as a food additive due to its low cost and high resistant starch content, which is particularly relevant in the formulation of health-promoting foods [

8]. Furthermore,

P. campechiana seeds, which are typically discarded as a by-product, could not only reduce waste but also provide an accessible and valuable source of starch.

Despite the importance of starch in the germination process, there is a paucity of studies examining the structural and starch content changes that occur in P. campechiana during germination. This deficit of knowledge constrains the capacity to devise efficacious strategies for seed conservation and its potential in the industry.

Accordingly, the objective of this study was to delineate the alterations in microstructure and starch content within the endosperm cells of P. campechiana seeds throughout the germination process. This was undertaken to ascertain the morphological and physiological characteristics that could potentially influence the cultivation and conservation practices of this species. It is hoped that this study will contribute to the existing knowledge about P. campechiana starches, which could have practical applications in the food, agricultural, and pharmaceutical industries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The plant material was obtained from fruit collected in the state of Morelos, Mexico. Semi-ripe fruit with a green-yellow color were selected [

9]. These fruit were numbered, weighed, and their equatorial and polar diameters were measured. The pulp was removed from each fruit, and the seeds were cleaned and characterized (weight, equatorial, and polar diameters).

2.2. Sample Preparation

The seeds were cleaned, disinfected, and manually scarified before inducing germination in 1-liter plastic pots filled with inert agrolite substrate. They were placed on movable beds in a greenhouse covered with treated white plastic, semi-acclimatized with fans (average temperature of 30°C, and watered with 300 ml of potable water every third day until the final sample was collected. Seed samples were taken 3, 33, 50, 74, 98, and 130 days after sowing. Each seed was cut into three parts (basal, central, and distal), and the basal part was used. Samples were fixed by immersion in jars with a 10:1 volume ratio of the fixing solution (FAA: Formaldehyde 37-40% (J.T. Baker), glacial acetic acid (SIGMA), ethanol 96% (Fermont), distilled water) at concentrations of 10:50:5:35, respectively [

10], for 48 hours. The fixation process aims to preserve the tissues by halting autolysis, allowing the tissues to remain unchanged after subsequent treatments [

11]. Ideally, the tissues harden slightly without fragmenting, maintaining their structure similar to their in vivo state [

12].

After fixation, the seeds were washed with distilled water for 30 minutes and dehydrated using an alcohol gradient, starting with low alcohol concentrations (35, 50, 70, 85, and 100%). Each concentration was applied for 24 hours. The dehydrated samples were placed in embedding cassettes to prepare paraffin blocks. Sections were obtained from each sample using a microtome and immediately transferred to a distilled water bath at 40°C before being placed on slides (Corning). They were left at room temperature in a plastic slide tray (KALTEK) to remove moisture.

2.3. Staining and Microscopy

The samples were stained with toluidine blue by applying 1% toluidine drops directly onto the non-deparaffinized sample for 2 minutes, followed by washing with distilled water. The samples were deparaffinized in an oven at 60°C for 30 minutes and then immersed in absolute xylene for 20 minutes. After drying for 24 hours, the samples were mounted in synthetic resin (60% xylene), and applied drop by drop before placing the coverslip. This technique produces a metachromatic reaction, meaning it can stain different structures in different colors [

10]. Finally, the samples were mounted with resin and observed under an optical microscope (Nikon Eclipse model 80i).

2.4. Image Analysis

Microphotographs were subjected to digital image analysis using ImageJ software version 1.54j to count the visible starch granules per field. First, the measurement scale was standardized according to the images. Then, the micrographs were segmented using the Color Threshold tool to separate the pigmented starch granules. After segmentation, the images were converted to binary format and edited to differentiate granules from other pigmented objects. The sequence in ImageJ was: Edit > Fill > Draw > Clear outside. Finally, quantitative analysis was performed using Analyze > Analyze particles, specifying circularity values between 0.5 and 1 to ensure only starch granules were counted.

To obtain micrographs of the starch granules, a solution was prepared using. To prepare a starch suspension in water and observe its granules under a microscope, a small amount flour from the basal part of the seed mixed with distilled water (1/20) mixing well until a homogeneous suspension was obtained. Then, a drop of this suspension was placed on a clean slide and carefully covered with a coverslip to prevent the formation of air bubbles. For observation, an optical microscope was used, starting with a 10X magnification to locate the granules and then increasing to 40X to examine their shape and structure in greater detail. The starch granules appeared as oval or polygonal structures, with variations in size depending on the starch source. The morphostructure of the cells was described based on size and shape, and for the study of starch granules, the selected variables were area and circularity.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Measurements of the sizes and morphological characteristics of the granules were obtained using ImageJ software. Statistical analyses of size distributions and averages were performed with IBM SPSS 20. For multivariate element analysis, Minitab 17 software was used

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Endosperm Cells

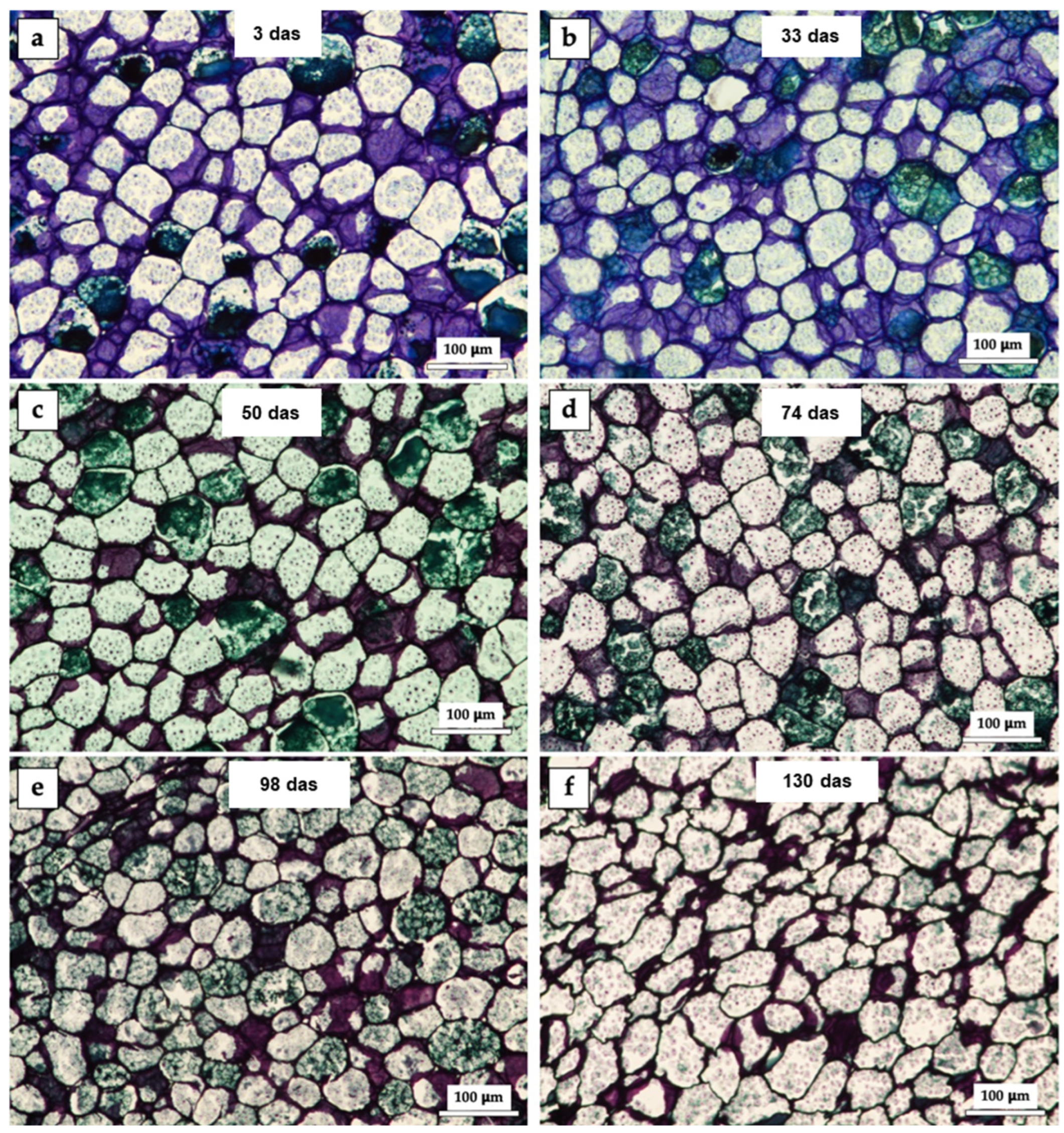

Differences in cell shape and appearance at each stage were evident (

Figure 1). Cells had an average diameter of 60 µm and mostly circularity greater than 0.7 (in an interval from 0 to 1, where 0 is a polygon and 1 is a circle). A change in cell density and compaction was observed over time. In the first micrographs (

Figure 1a,b), the starch granules appear larger and more defined, while in later micrographs (

Figure 1e,f), a reduction in their size and greater compaction can be observed. Dots stained blue in different shades were observed, which correspond to starch granules agglomerated in the endosperm cells as an energy reserve [

13]. As reported [

14], the red or purple hues observed in the stained samples indicate a high degree of metachromasia, attributable to the presence of a substantial quantity of pectin in that structure. Conversely, the dominance of blue hues is indicative of ortocromasia, characterized by a reduced pectin content. Staining with toluidine blue highlights specific tissue components, such as starch and cell walls. Over time, variations in color intensity were observed, which could be related to changes in the tissue’s chemical composition.

Figure 1a–f show the physical changes in histological cross-sections of

P. campechiana seed endosperm at 10x magnification. 3 days after sowing (das), a purple color predominated in the cell structures because the metachromatic dye toluidine blue turns deep purple when a significant amount of pectin is present. Some bright green staining was also observed, indicating lignified cell walls [

15]. At 33 das (

Figure 1b), the purple color was still predominant due to the action of pectin in the cell wall. The micrograph in

Figure 1c shows the change at 50 das, where the green color predominates in the stained structures, indicating lignification of the secondary walls as germination progresses, that is, the walls have thickened.

These results are related to those reported in a study, where lignification is regulated in space and time, and there is also a variation in lignification, which depends on the plant species, age, tissue and whether the walls are primary or secondary [

16]. Another report mentions that the lignin content in the tegument of

Araucaria angustifolia is higher compared to levels reported for seeds of other tree species [

17].

At 74 das (

Figure 1d), the predominant color is green, and the cell structure is polygonal rather than circular. At 98 das (

Figure 1e), the staining is like that observed previously. There are no evident changes in the structures. However, at 130 das (

Figure 1f), the changes are obvious. This is because the cut is less stained because of the degradation of the structures and the use of the energy reserve for the development of the seedling [

18,

19]. These reserves are mobilised during germination into the growing seedling, resulting in increased metabolic activities, which in turn lead to chemical changes in macromolecules. Increased enzyme activity in seeds during germination is often associated with the modification and generation of new compounds. [

20].

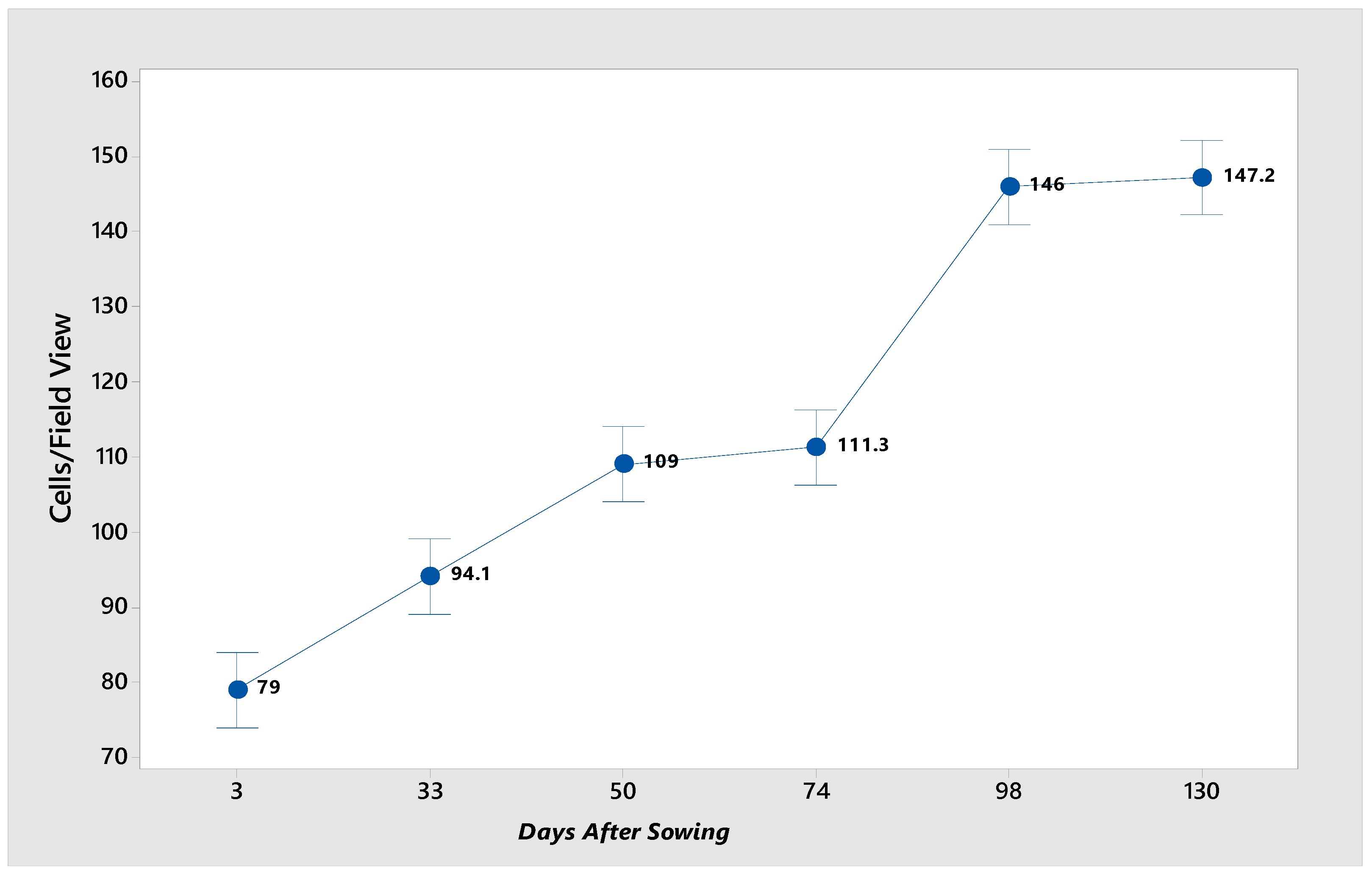

The cell count per field (

Figure 2) revealed that as germination and seedling development proceeded, the number of cells increased by the growth in biomass resulting from cell division. At the onset of germination, the seed undergoes rapid water absorption, increasing in cell size. At 74 das, a notable decline in cell number was observed, potentially due to reduced water absorption or unfavorable environmental conditions that impede metabolic activity within the seed. Additionally, the cells at the initial stage of germination possess a substantial starch reserve, contributing to their larger size.

It is hypothesized that the cells (

Figure 1a–f) adopt a polyhedral shape; however, during the initial stages of germination, they are observed to be relatively rounded in the plane. With time, because of the degradation of structures and starch, they transform shape, becoming polygonal.

A study has determined the morphological characterization of starch from different natural sources such as maize, cassava and potato. In the case of maize starch, the perimeter shape was different, as the large granules had an irregular polygonal shape and the small granules had a circular shape. With respect to cassava starch, the shape reported was regular elliptical or circular for all its dimensions; the small granules of potato starch presented circular shapes, while the large granules presented elliptical and sometimes irregular shapes [

21].

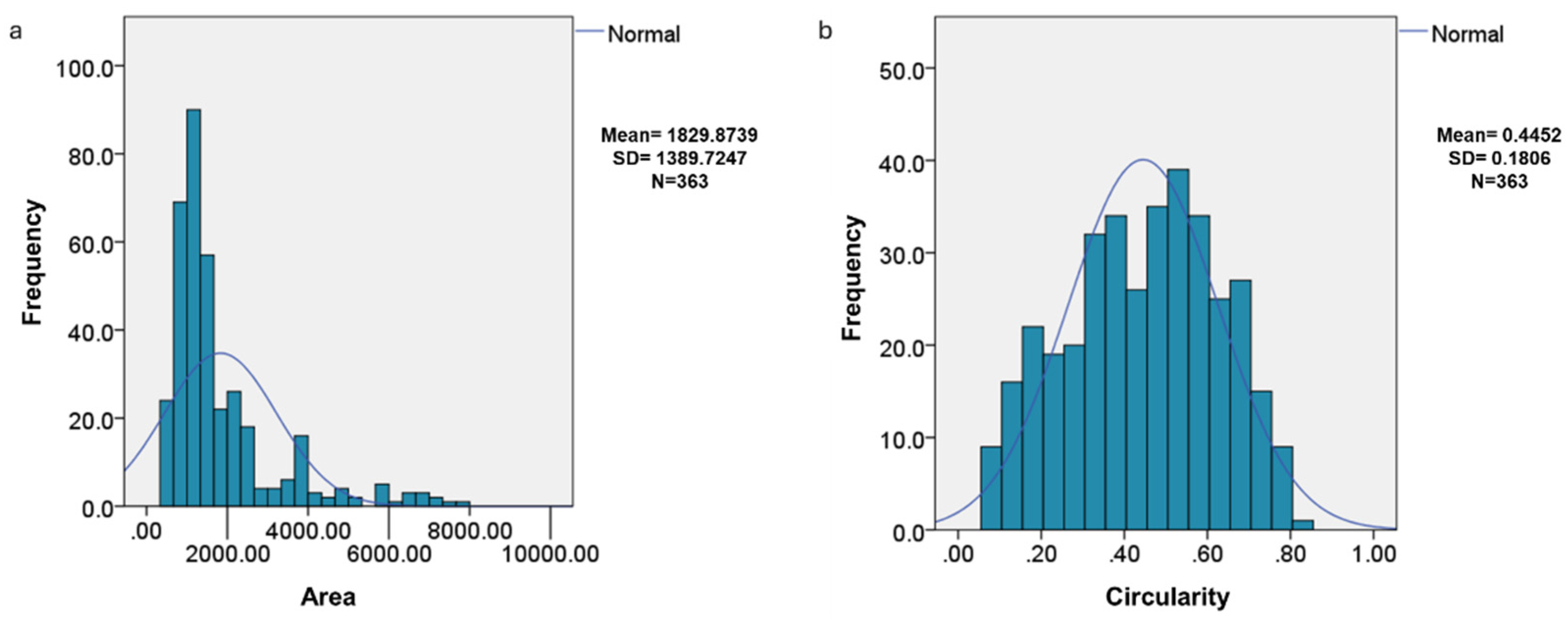

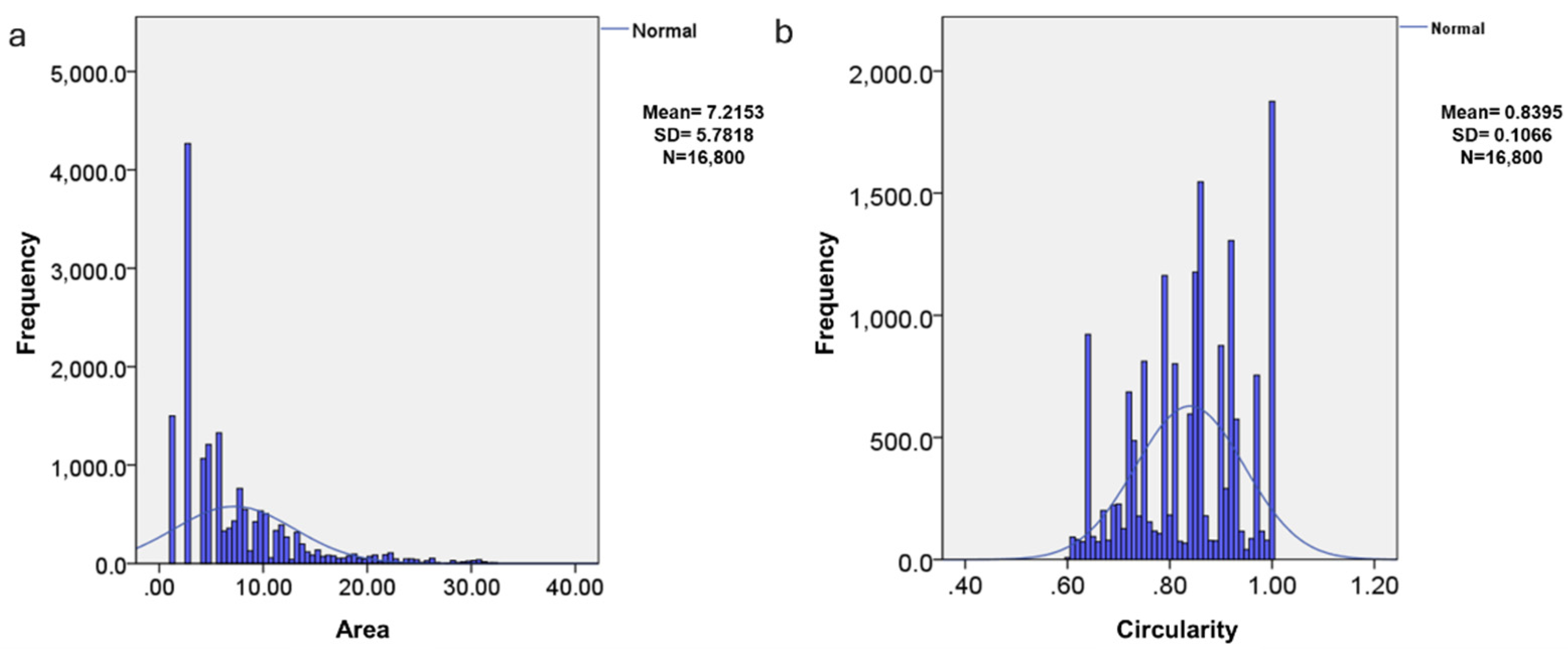

The distribution of the area and circularity of the endosperm cells was not normal (

Figure 3), which is related to the high variability that occurs in biological data matrices. Circularity indicates that the structures are not completely spherical, with an average of 0.4452, which implies that many have irregular shapes. The difference in the distributions of area and circularity indicate biological processes in which the structures change in size and shape over time.

3.2. Starch

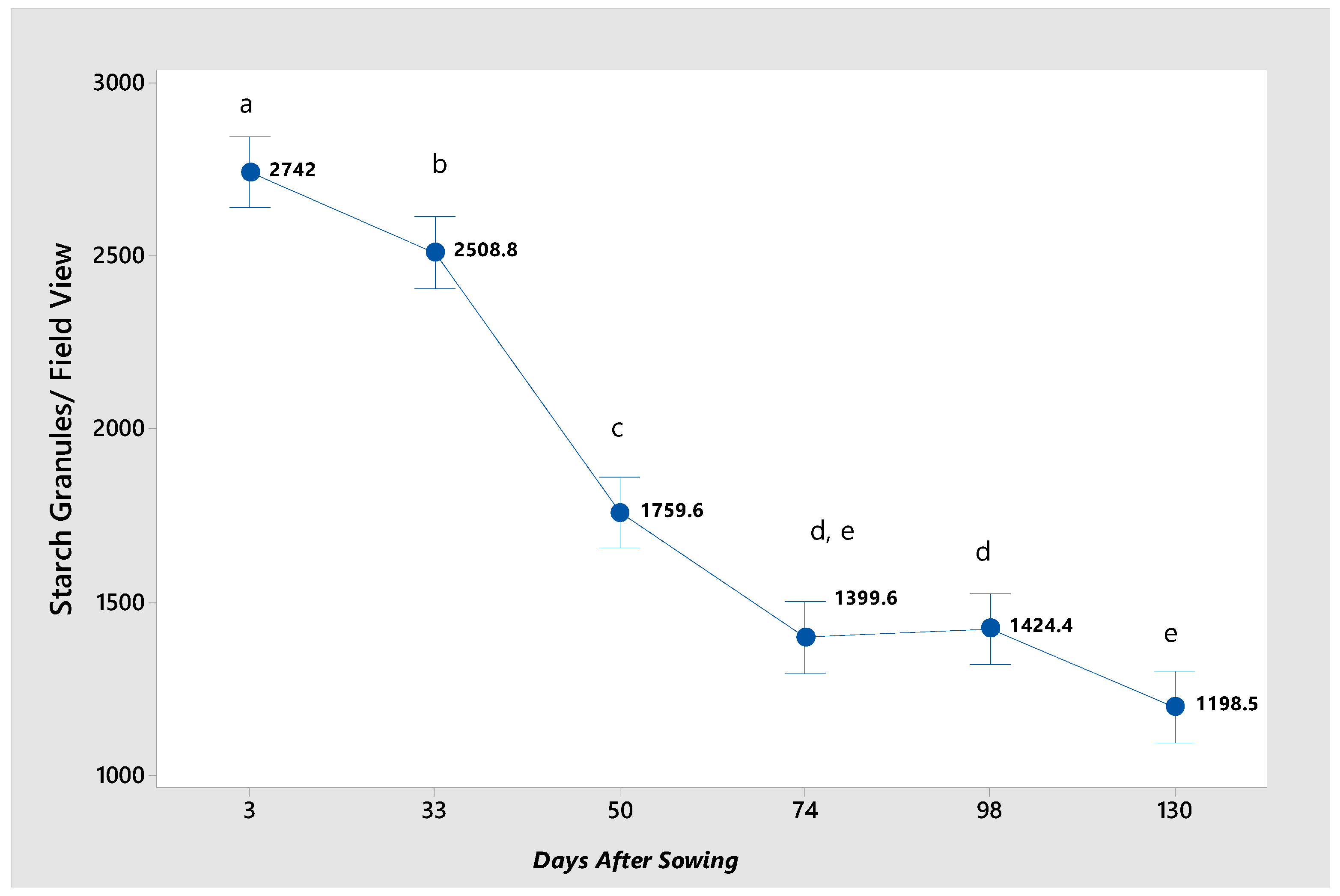

In

Figure 1a–f, the blue to purple-colored dots are indicative of the starch granules present within the cell structure at the various germination stages. In the early stages of germination, the starch granules appear more separated and with a well-defined structure. As time progresses, their density and distribution change, possibly indicating a process of starch degradation or conversion. The greatest concentration of starch granules is observed at 3 and 33 das (

Figure 4). At 50 das, the starch granule content decreases drastically, likely because, at this stage of germination, the plant has already developed true leaves and requires more energy to complete the metabolic process in which the mobilization of this energy reserve occurs [

22]. At 74 das, the starch granule content decreases, primarily due to the continued mobilization of reserves for utilization in plant development. In the final two stages of germination, the number of starch granules remains low, depleting the starch reserve. However, it is not entirely exhausted, as the plant has initiated photosynthesis and is producing starch for further development.

The size and shape of the starch granules vary according to the germination stage of the seed (

Figure 5). Like what was observed in the cells, their distribution is abnormal. This is due to the great variability of the granules in the different germination stages [

23] and the source from which they are obtained [

24]. The distribution is right-skewed, with most areas concentrated in lower values and a long tail extending towards higher values, indicating many small structures (

Figure 5a). The structures have circularity values close to 1, indicating a tendency towards more spherical shapes (

Figure 5b).

The general shape of starch granules from

P. campechiana seeds is circular and round, but the size varies considerably. In

Figure 6a the granules of different sizes are observed, and in

Figure 6b with polarized light, where the characteristic birefringence of starch can be appreciated, and the Maltese cross can be seen.

Figure 6c,d correspond to micrographs at 50 das, in bright field and polarized light respectively, the granules have different sizes and shapes, less circular than at 3 das.

Figure 6e,f correspond to micrographs at 98 das, where the granules vary considerably in size. At all stages of germination, the hilum of the granules is concentric, indicating radially symmetric granule growth.

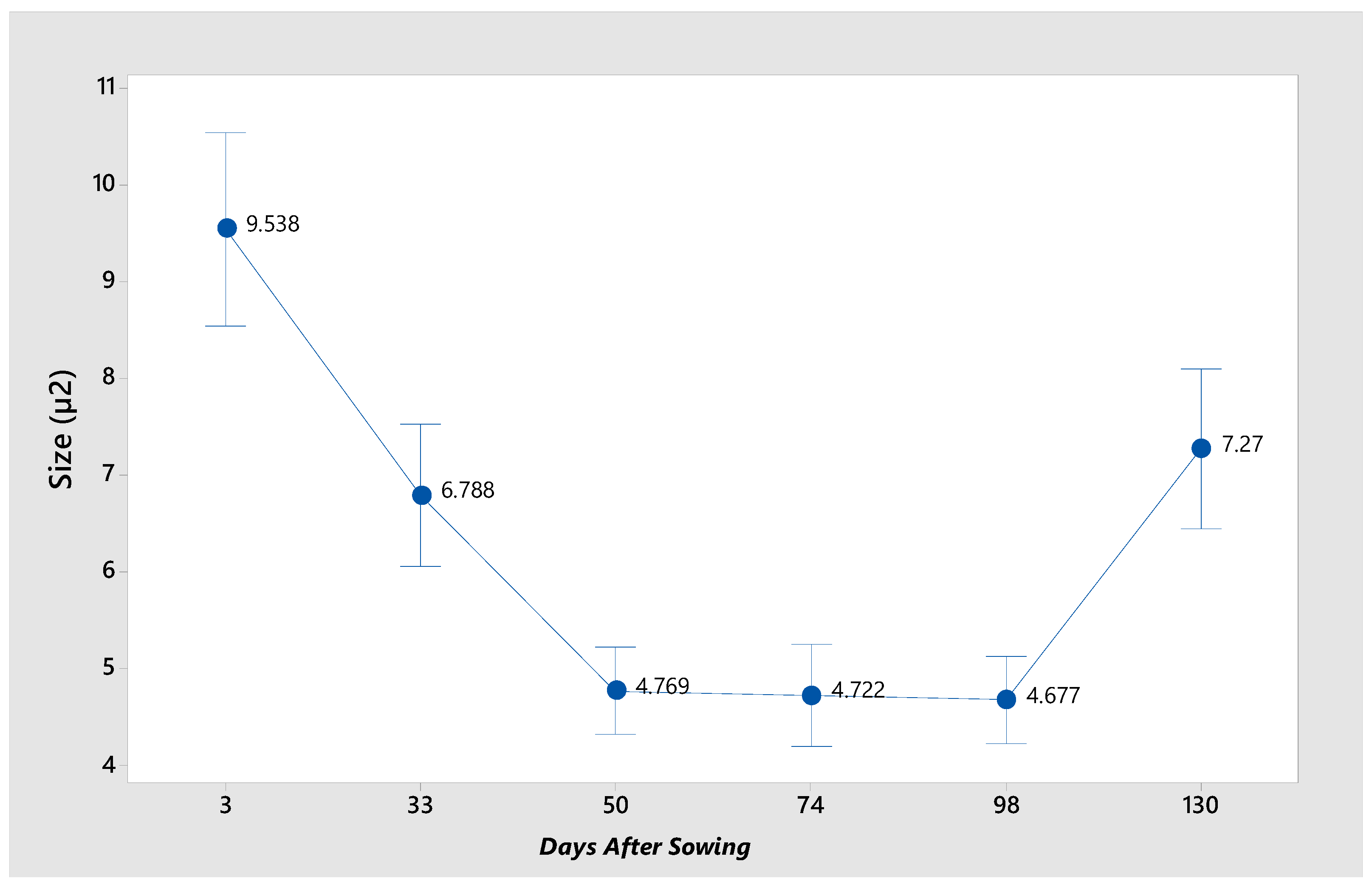

Figure 7 illustrates the mean for each stage, demonstrating the variability of granule size. At 3 das, the largest granules are observed with a mean of 9.53 µm², while at 33 and 130 das, no significant difference in size is evident. Conversely, at 50, 74, and 98 das, the smallest granules are identified.

There is a study in which the morphology of starch granules in the pulp and seed of immature fruits of

Pouteria campechiana is reported. Small granules with smooth surface were observed, in the starch of the pulp and seed the malt cross was observed, thus confirming the semi-crystalline structure of the starch. Larger granules (11 µm) were observed compared to those of the seed (8 µm) [

2]. Similar data were reported for the determination of starch granules from seed (14. 38 µm) and pulp (15.28 µm) [

7].

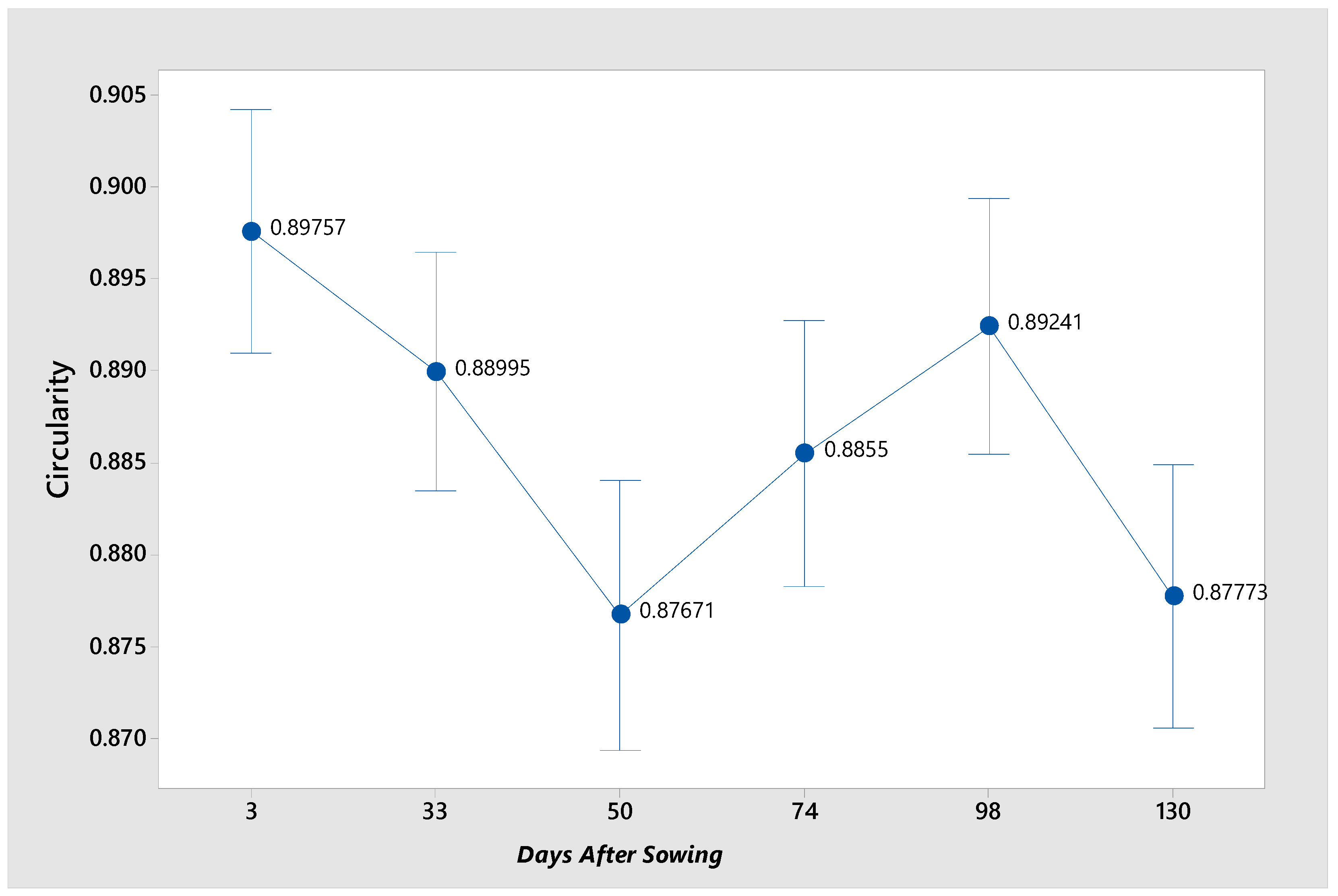

Additionally, an elemental analysis was conducted to ascertain the circularity of the granules (

Figure 8). The starch granules of

P. campechiana seeds were observed to be circular, as depicted in the micrographs. It can be assumed that these granules are perfectly round. The shape of the granules remains consistent throughout the entirety of the germination process, exhibiting no variation across the six stages.

These results are related to those reported for quinoa (

Chenopodium quinoa Willd), where large changes in morphology, crystalline structure, and physicochemical properties of starch were observed during germination. An increased number of pores due to enzymatic action and starch degradation was also observed in the germinated quinoa seeds. In addition, the molecular size of starch-forming amylose and amylopectin gradually increased in the germination process [

26].

Another study investigated the synergistic effect of germination and NaCl on the microstructure and physicochemical properties of wheat starch using the application of a 60 mmol/L NaCl solution. The results obtained showed that the germination process is very important, as it significantly influenced the variations in granule size, crystallinity, lamellar order, chemical composition, as well as the microstructure of wheat starch. In addition, hydrogen bond breakage and the degree of branching occurred [

27].

4. Conclusions

The seed endosperm cells of P. campechiana exhibit considerable variability in size and shape throughout the germination period. At the onset of germination, the cells are circular in the plane. As germination progresses, they transform, becoming polyhedral and polygonal in the plane. The number of cells per field increases as germination progresses. This change in shape and increase in number is due to the degradation of starch, which is contained in the cells as an energy reserve.

The starch granules exhibited considerable variability in size across the evaluated stages of germination. In general, they were observed to be relatively small in comparison to other major sources, such as corn. The granules were observed to be circular in plan and round in appearance, with a concentric hilum. During the germination process, there is a reduction in starch content, accompanied by a variation in size between each stage. The shape of the granules is consistently circular throughout the germination process. It is important to mention that starches from different plant sources have different amounts of amylose and amylopectin and therefore a crystalline structure of type A, B or C, which is why the starch granule morphology, thermal properties and swelling rates are unique to each plant source.

Due to their spherical shape and diminutive size, these granules demonstrate enhanced water absorption capacity, which facilitates swelling and gelatinization. It can therefore be concluded that starch from P. campechiana seeds can be exploited and used in the food industry as a raw material to encourage fruit development and the propagation of this underutilized species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.M.G.-V, S.E.-L., T.R.-G., and J.F.P.-B.; methodology, D.T.-M.,M.R.-M, M.C.G.-C and K.M.G.-V; investigation, J.F.P.-B, S.E.-L., T.R.-G. and K.M.G.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M.G.-V. and S.E.-L.; writing—review and editing, , J.F.P.-B., K.M.G.-V, S.E.-L. and T.R.-G.; visualization, S.E.-L., T.R.-G, and J.F.P.-B., funding acquisition, S.E.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado (SIP), Program BEIFI of Instituto Politécnico Nacional México, for their support in carrying out the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- González, C. J. G. Algunas ideas sobre la presencia del zapote en el culto a Xipe Tótec. Estudios Mesoamericanos. 2004, (6), 38-47.

- Agama-Acevedo, E.; Bello-Pérez, L.A.; Pacheco-Vargas, G.; Nuñez-Santiago, M. C.; Evangelista-Lozano, S.; Gutiérrez T. J. Starches Isolated from the Pulp and Seeds of Unripe Pouteria campechiana Fruits as Potential Health-Promoting Food Additives. Starch. 2022, 75: 2200089. [CrossRef]

- Crane, J. H.; Balerdi, C. F. ‘Canistel Growing in the Florida Home Landscape Planting a Canistel Tree’, 2016, 1–6.

- Duarte, O.; Villagrán L. ‘Efecto de la escarificación, remojo en ácido giberélico, posición de siembra y edad de la semilla en germinación y conformación de plántulas de canistel (Pouteria campechiana Baehni)’. Proceedings of the Interamerican Society for Tropical Horticulture. 2002, 46: 14-16.

- Awang-Kanak, F.; Abu Bakar, M. F. ‘Canistel— Pouteria campechiana (Kunth) Baehni’, En: Rodrigues S.; De Oliveira Silva, E.; Sousa de Brito, E. Exotic Fruits. Brazil: Academic Press. 2018, 107–111. [CrossRef]

- Alcázar-Alay, S. C.; Meireles, M. A. (2015) ‘Physicochemical properties, modifications, and applications of starches from different botanical sources’, Food Science and Technology, 35(2), pp. 215–236. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, F.; Zhu, K.; Wu, G. Multi-scale supramolecular structure of Pouteria campechiana (Kunth) Baehni seed and pulp starch. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022, 124: 107284. Part A, ISSN 0268-005X, . [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, F.; Zhu, K.; Huang, C. A novel underutilized starch resource - Lucuma nervosa A.DC seed and fruit. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021, 120: 106934, ISSN 0268-005X, . [CrossRef]

- Evangelista-Lozano S.; Robles-Jimarez H.R.; Briones-Martínez R.; Escobar-Arellano S.L.; Pérez-Barcena J.F. ‘Análisis Proximal de Frutos de Pouteria campechiana (Kunth Baehni)’. En: Durán, H.D,; Tzintzun, C.O.; Grimaldo-Juárez, O.; González-Mendoza, D.; Ceceña-Durán, C.; Cervantes D.L.; Michel, L.C.; Ruiz, A.C. Compendio Científico en Ciencias Agrícolas y Biotecnología. OmniaScience (Omnia Publisher SL): Terrassa, Barcelona, España. 2019, 1:85-90. DOI: . [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Zapotitla, E. Técnicas aplicadas al estudio de la anatomía vegetal, 1ra edición. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México, 2005, ISBN: 9703231314.

- Reig-Armiñana, J.; García-Breijo, F. Técnicas De Histología Vegetal. En Laboratorio técnicas de histología vegetal. Universidad Politécnica de Valencia. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Cediel, J. F.; Cárdenas, M. H.; Chuaire L.; Payán C. Manual de histología tejidos fundamentales. (1ra edición). Universidad del Rosario editorial; 2009. ISBN-10: 9588378893.

- Zhao, L.; Pan, T.; Cai, C.; Wang, J.; Wei, C. Application of whole sections of mature cereal seeds to visualize the morphology of endosperm cell and starch and the distribution of storage protein. Journal of Cereal Science, 2016, 71, 19-27. Elsevier Ltd., 71, pp. 19–27. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, V. C.; Leitão, C. A. E. Utilisation of Toluidine blue O pH 4.0 and histochemical inferences in plant sections obtained by free hand, Protoplasma. Protoplasma. 2020, 257(3), pp. 993–1008. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T. P.; Feder, N.; McCully, M. E. Polychromatic staining of plant cell walls by toluidine blue O, Protoplasma, 1964, 59(2), pp. 368–373. [CrossRef]

- Grabber J.H. How do lignin composition, structure, and cross-linking affect degradability? A review of cell wall model studies. Crop Science, 2005, 45(3), 820-831. [CrossRef]

- Affonso-Sampaio, D.; Dos Santos-Abreu, H.; Silveira-Augusto, L.D.; Da Silva, B.; Marcela-Ibanez, C. Perfil lignoídico del tegumento de semillas de Araucaria angustifolia. Bosque, 2016, 37(3), 549-555. [CrossRef]

- Bernal, L.; Barajas, E. M. Una nueva visión de la degradación del almidón. Revista del Centro de Investigación. Universidad La Salle, 2006, 7(25), 77-90.

- Kossmann, J.; Lloyd, J. Understanding and Influencing Starch Biochemistry. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 2000, 19(3), 171–226. [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Aguirre, J. C.; Quintero-Castaño, V. D.; Beltrán-Bueno, M.; Rodríguez-García, M. E. Study of the changes on the physicochemical properties of isolated lentil starch during germination. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2024, (267), . [CrossRef]

- Medina, J. A.; Salas, J. C. Morphological Characterization of Native Starch Granule: Appearance, Shape, Size and its Distribution (2008).. Revista de Ingeniería, (27), 56-62.

- Doria, J. Generalidades sobre las semillas: su producción, conservación y almacenamiento. Cultivos Tropicales, 2010, 31(1), 00.

- Medina, J. A.; Salas, J. C. Caracterización morfológica del granulo de almidón nativo: Apariencia, forma, tamaño y su distribución. Revista de Ingeniería, 2008, (27), 56-62.

- Casarrubias-Castillo, M.; Méndez-Montealvo, G.; Rodríguez-Ambriz, S.; Sánchez-Rivera L.; Bello-Pérez, L.A. Diferencias estructurales y reológicas entre almidones de frutas y cereales. Agrociencia, 2012, 46(5), 455-466.

- Agama-Acevedo, E.; Bello-Pérez, L.A.; Pacheco-Vargas, G.; Nuñez-Santiago, M.C.; Evangelista-Lozano, S.; Gutiérrez, T.J. Starches Isolated from the Pulp and Seeds of Unripe Pouteria campechiana Fruits as Potential Health-Promoting Food Additives. Starch—Stärke 2023, 75, . [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Cong T.; Menghan, S.; Qinping, Z.; Bangwei, Z.; Hongliang C.; Guixing, R.; Xiushi Y.; Peiyou, Q. Effect of germination treatment on the structural and physicochemical properties of quinoa starch. Food Hydrocolloids, 2021, (115), . [CrossRef]

- Ningjie, L.; Yining, P.; Dongyang, Y.; Xueling, Z.; Zipeng, L.; Jiaying, S. Effect of NaCl stress germination on microstructure and physicochemical properties of wheat starch. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2025, (297). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).