Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field and Data

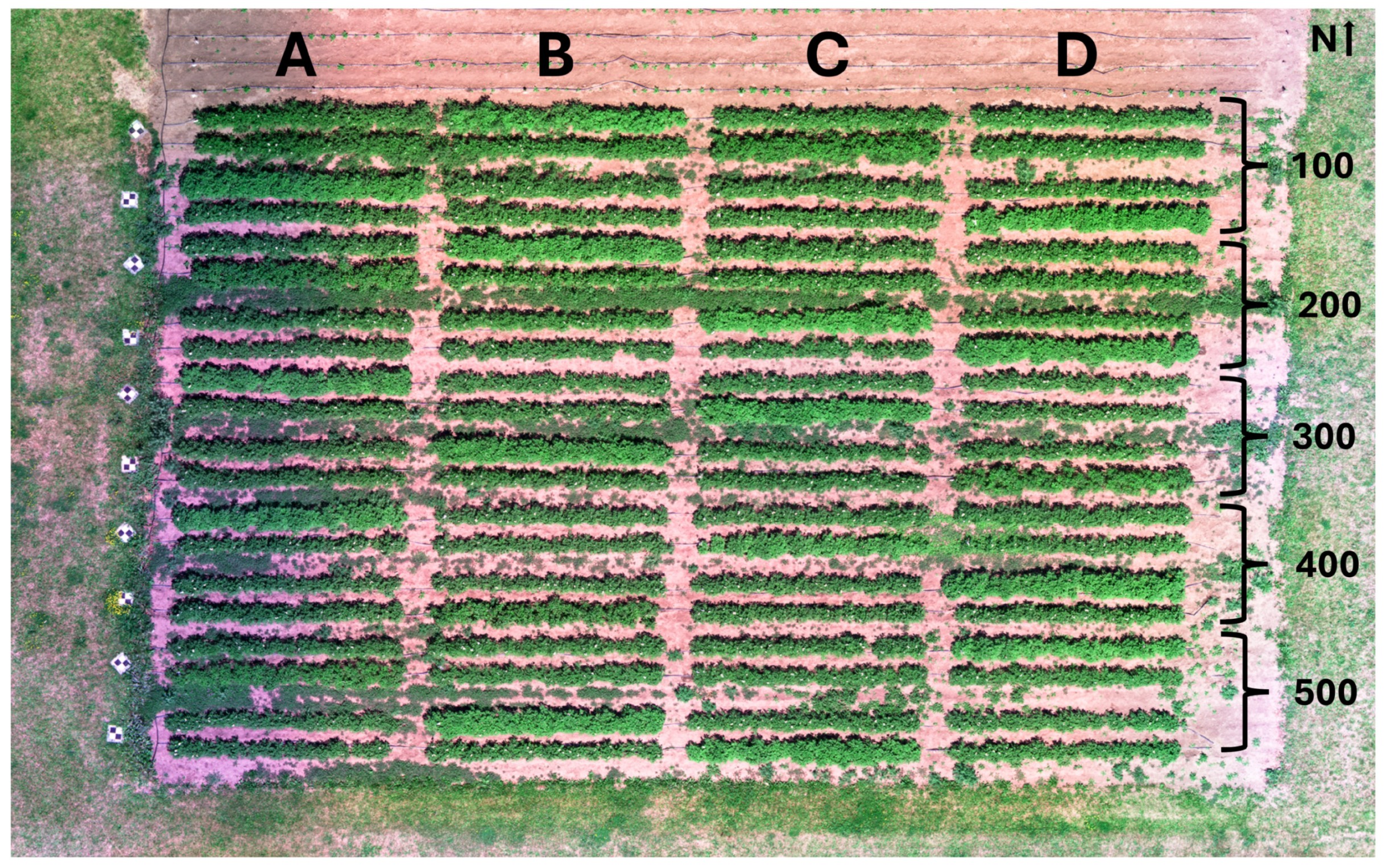

2.1.1. Experimental Field

| Treatment | Block 100 | Block 200 | Block 300 | Block 400 | Block 500 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 - 50% PVY | 104 D | 201 B | 302 C | 401 A | 504 C |

| T2 - PVY+ Plants, PVY- Tubers | 101 B | 203 C | 301 A | 402 C | 501 D |

| T3 - Uma Control | 103 A | 204 D | 303 B | 404 D | 503 B |

| T4 - DRN Control | 102 C | 202 A | 304 D | 404 B | 502 A |

2.1.2. UAV and Hyperspectral Camera

2.1.3. Hyperspectral Dataset

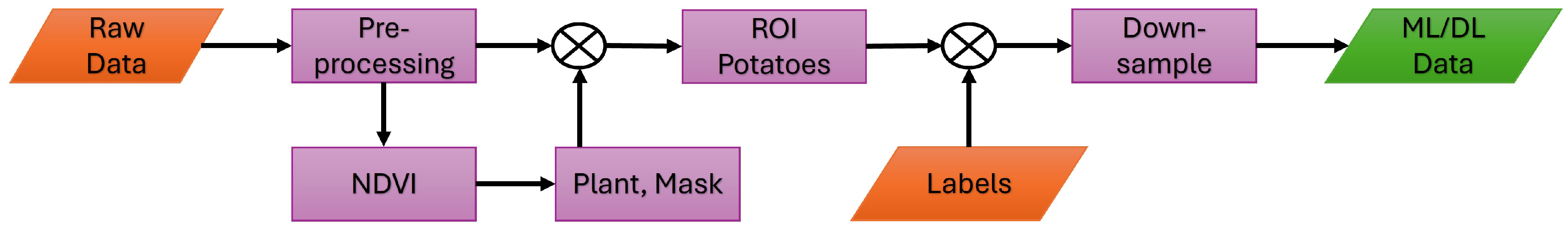

2.2. Data Processing

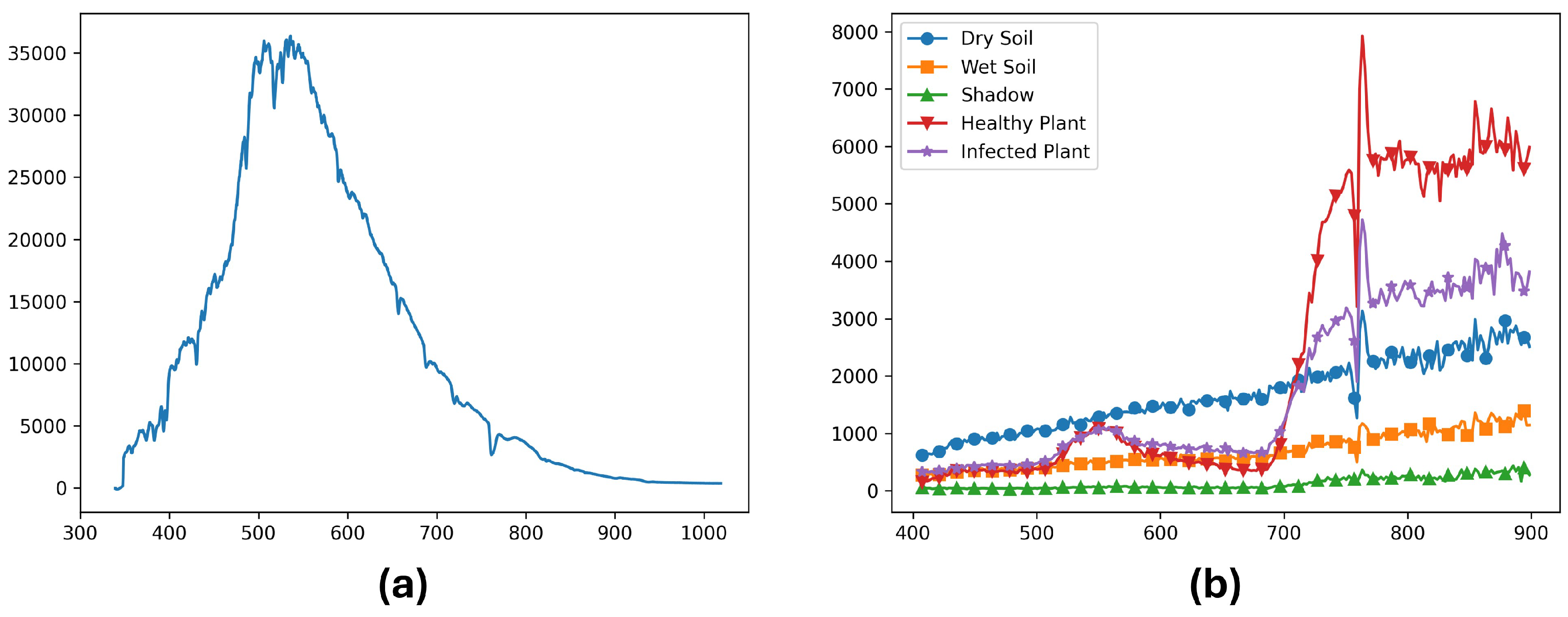

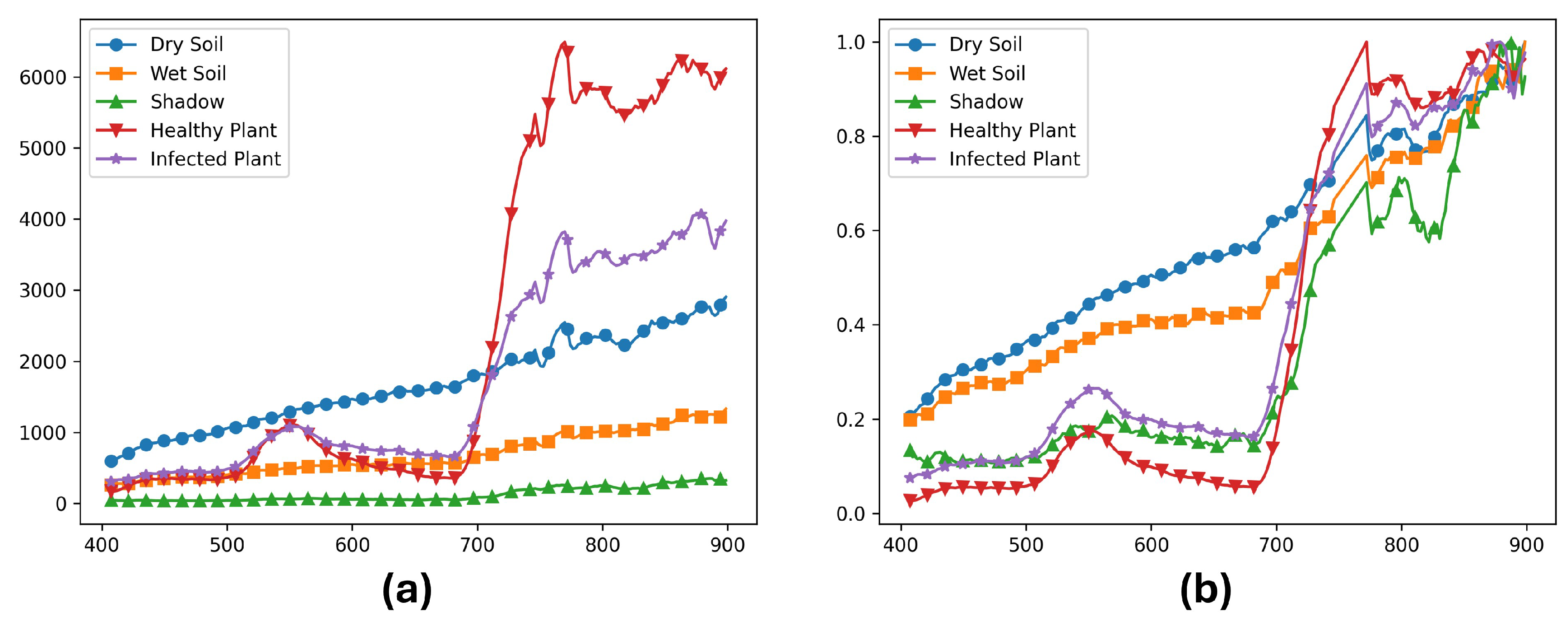

2.2.1. Preprocessing

2.2.2. ELISA Test

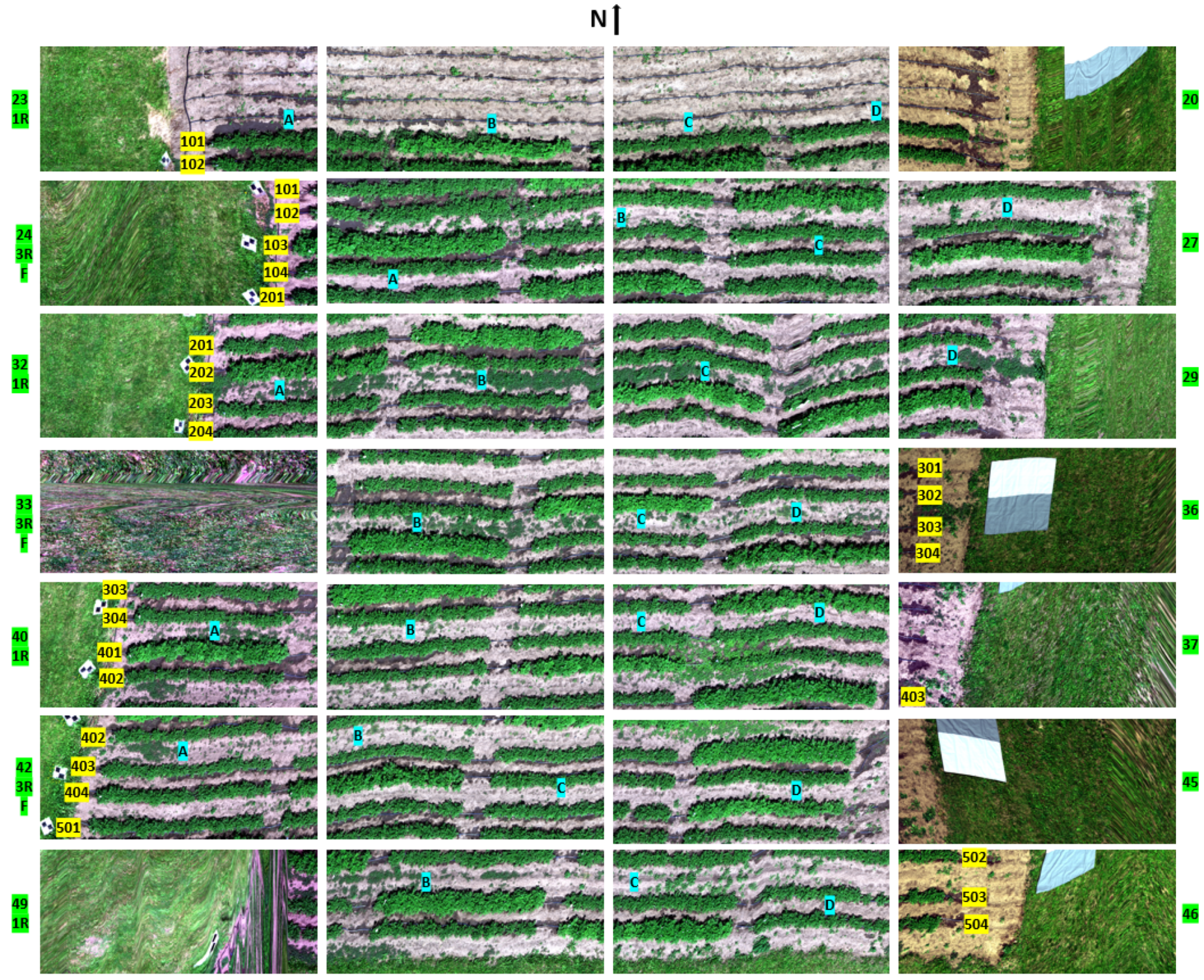

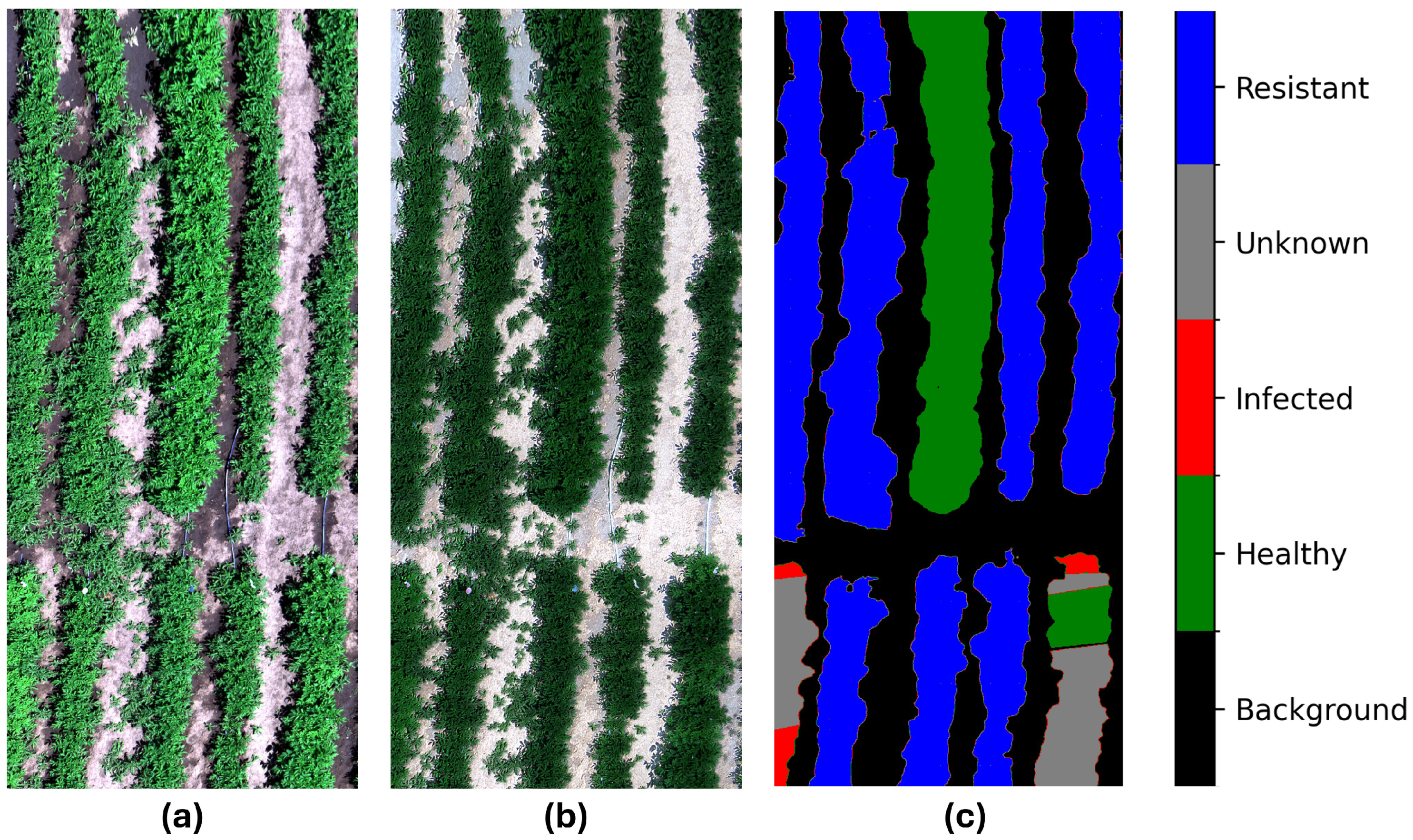

2.2.3. Labeling

2.3. Machine Learning and Deep Learning

2.3.1. Support Vector Machine

2.3.2. Decision Tree

2.3.3. k-Nearest Neighbors

2.3.4. Logistic Regression

2.3.5. Neural Network

2.3.6. Convolutional Neural Network

2.3.7. Hyperparameter Optimizations

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

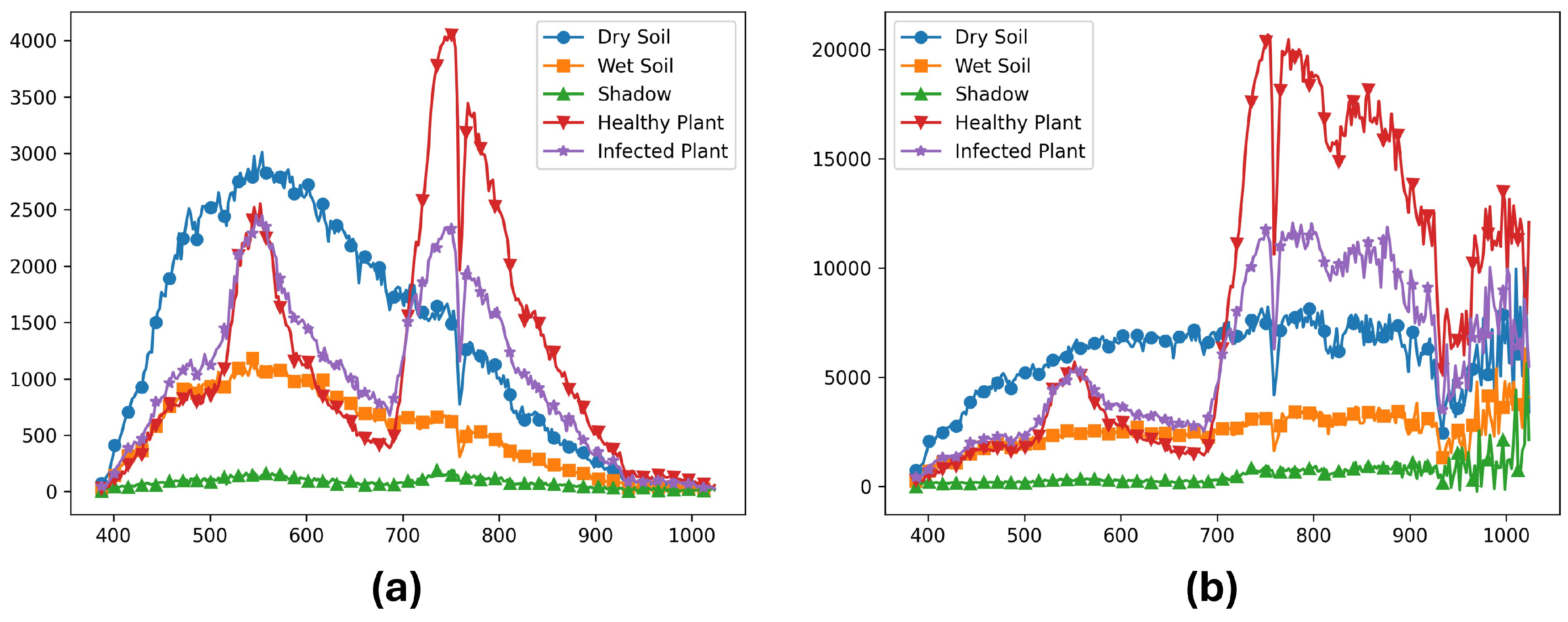

2.5. Band Selections

2.6. Workflow

3. Results

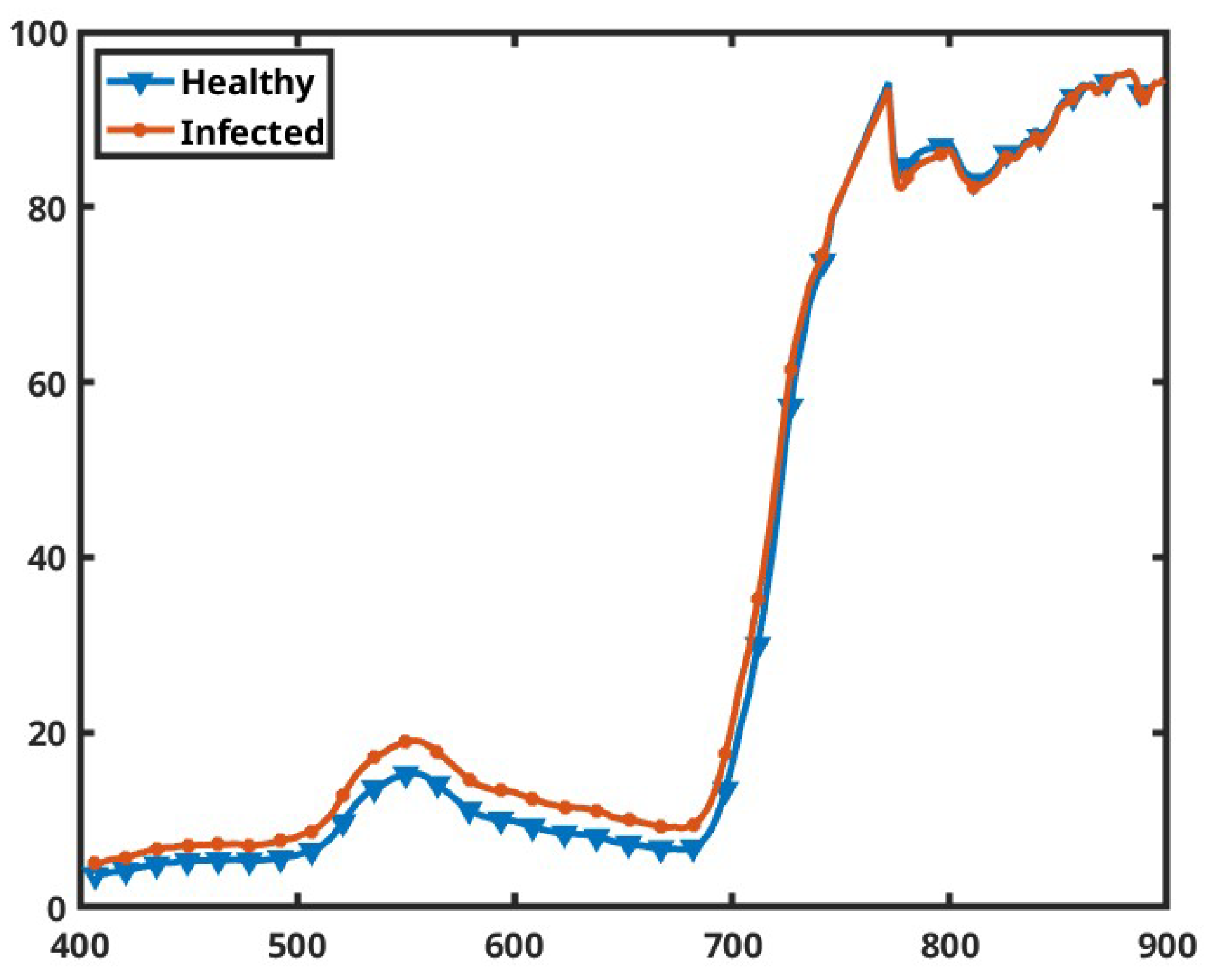

3.1. Dataset

3.2. Model Architectures and Optimizations

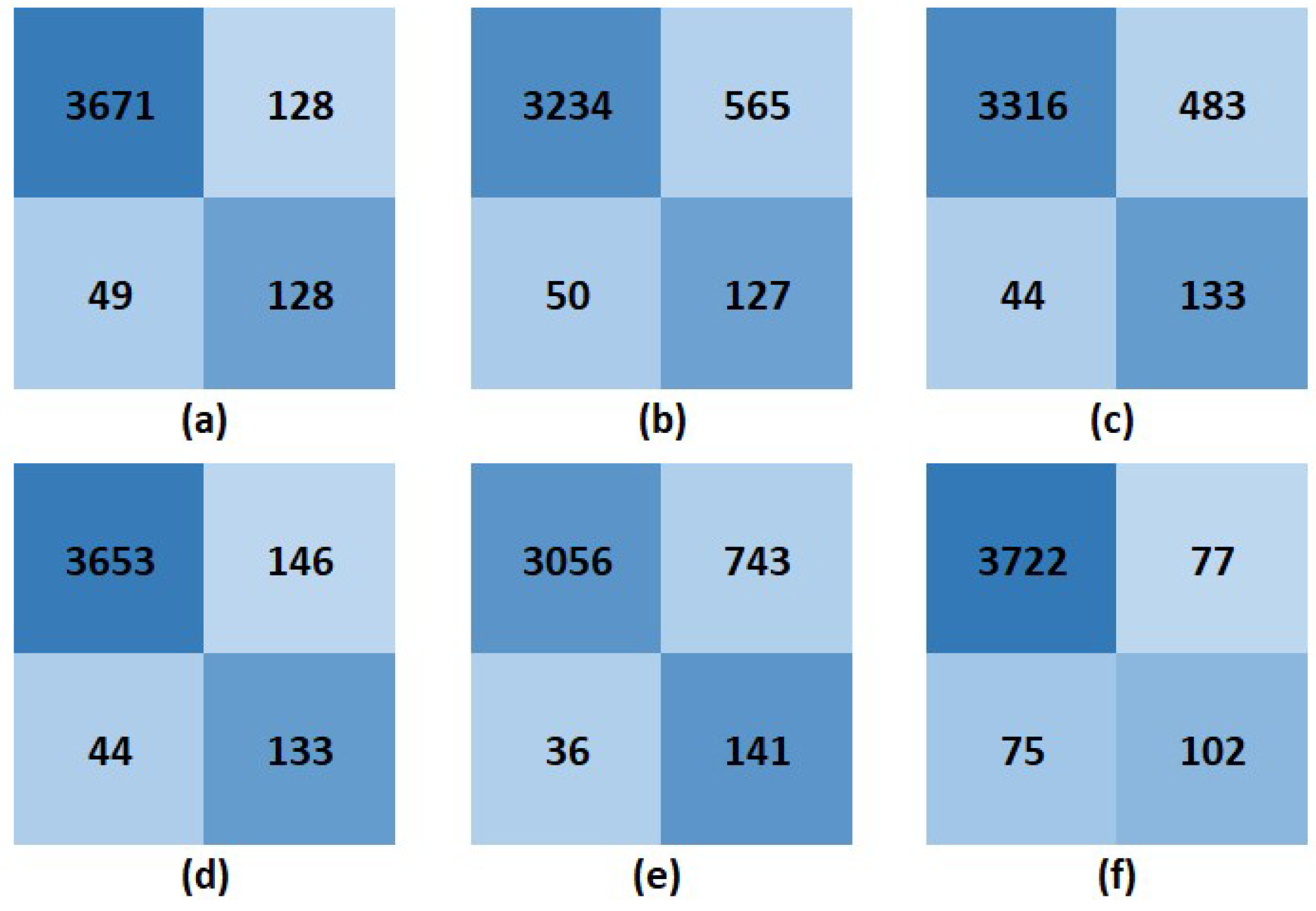

3.3. Model Performances

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | 0.956 | 0.966 | 0.987 | 0.977 |

| DT | 0.845 | 0.851 | 0.985 | 0.913 |

| KNN | 0.868 | 0.873 | 0.987 | 0.926 |

| LR | 0.952 | 0.962 | 0.988 | 0.975 |

| FNN | 0.804 | 0.804 | 0.988 | 0.887 |

| CNN | 0.962 | 0.980 | 0.980 | 0.980 |

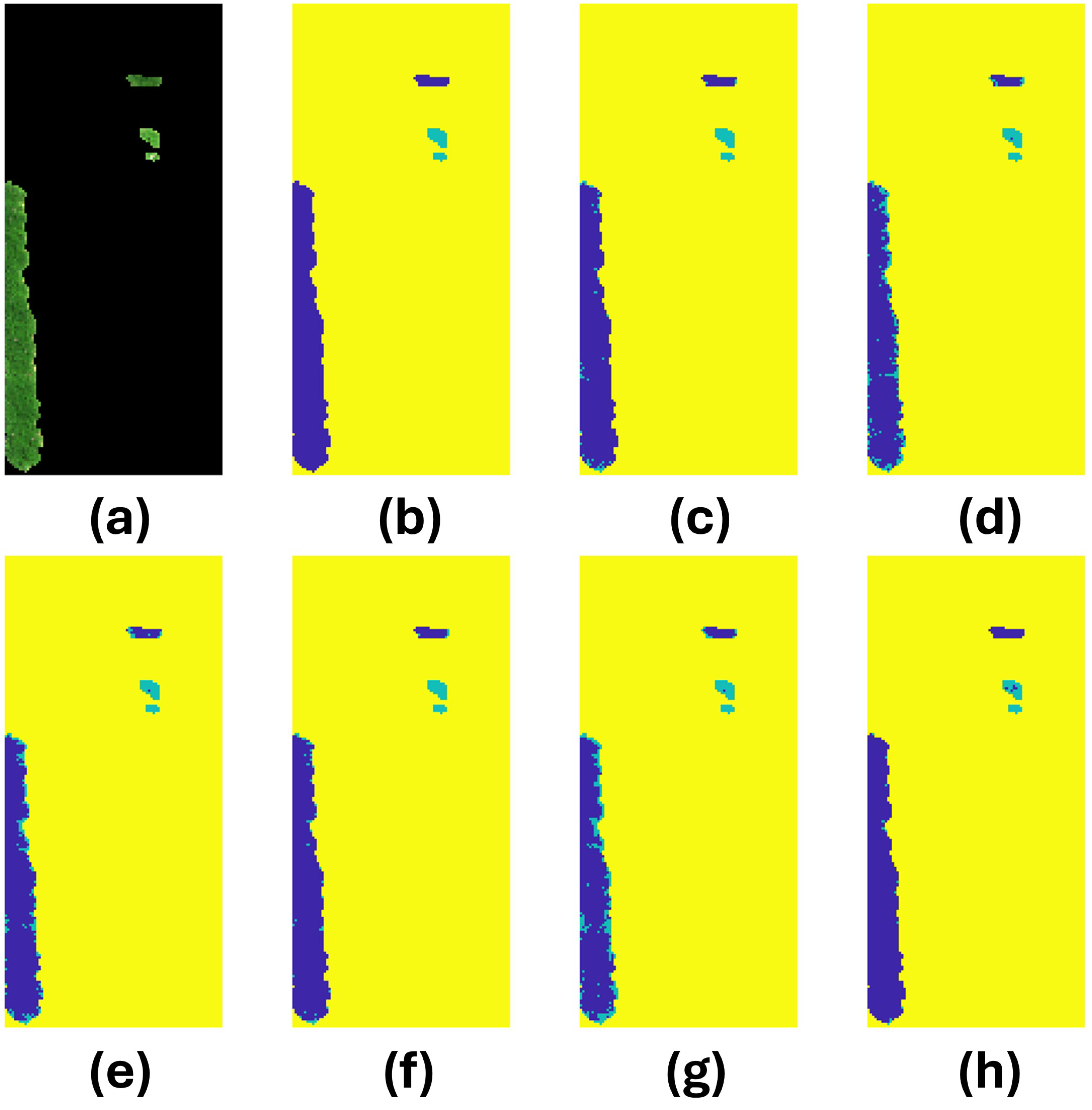

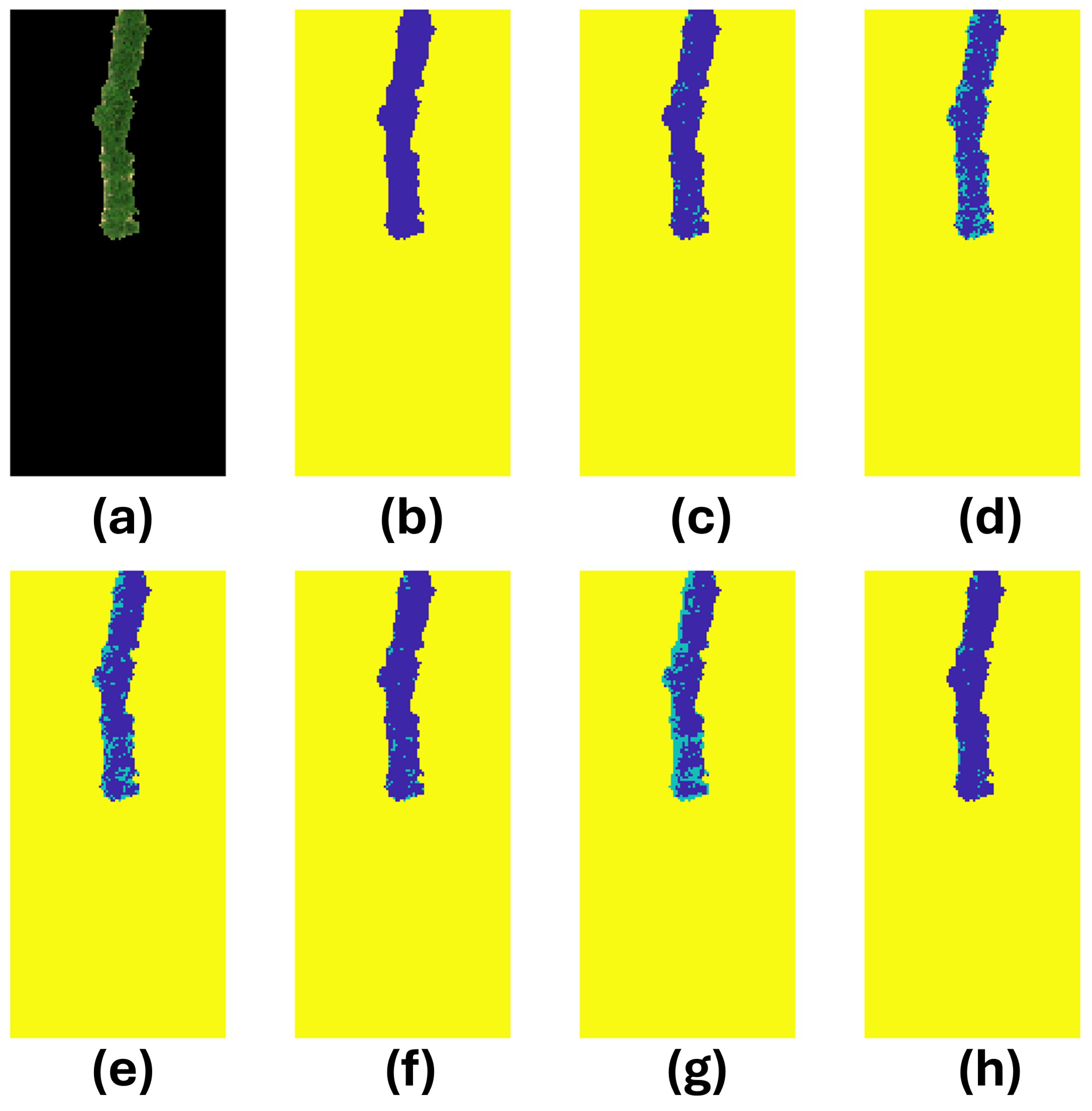

3.4. Prediction Analysis

| Image | Model | Accuracy | # True Infected | # Predicted Infected | # Correct Infected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | SVM | 0.936232 | 54 | 40 | 36 |

| DT | 0.817391 | 69 | 30 | ||

| KNN | 0.886957 | 61 | 38 | ||

| LR | 0.933333 | 53 | 42 | ||

| FNN | 0.84058 | 77 | 38 | ||

| CNN | 0.904348 | 23 | 22 | ||

| 31 | SVM | 0.935018 | 57 | 49 | 26 |

| DT | 0.894103 | 95 | 32 | ||

| KNN | 0.8929 | 92 | 30 | ||

| LR | 0.927798 | 53 | 25 | ||

| FNN | 0.880866 | 118 | 38 | ||

| CNN | 0.942238 | 29 | 19 | ||

| 39 | SVM | 0.969717 | 66 | 111 | 66 |

| DT | 0.876851 | 247 | 65 | ||

| KNN | 0.902423 | 209 | 65 | ||

| LR | 0.969717 | 111 | 66 | ||

| FNN | 0.839166 | 303 | 65 | ||

| CNN | 0.987887 | 74 | 61 | ||

| 43 | SVM | 0.957382 | 0 | 56 | 0 |

| DT | 0.786149 | 281 | 0 | ||

| KNN | 0.806697 | 254 | 0 | ||

| LR | 0.952816 | 62 | 0 | ||

| FNN | 0.70624 | 386 | 0 | ||

| CNN | 0.959665 | 53 | 0 |

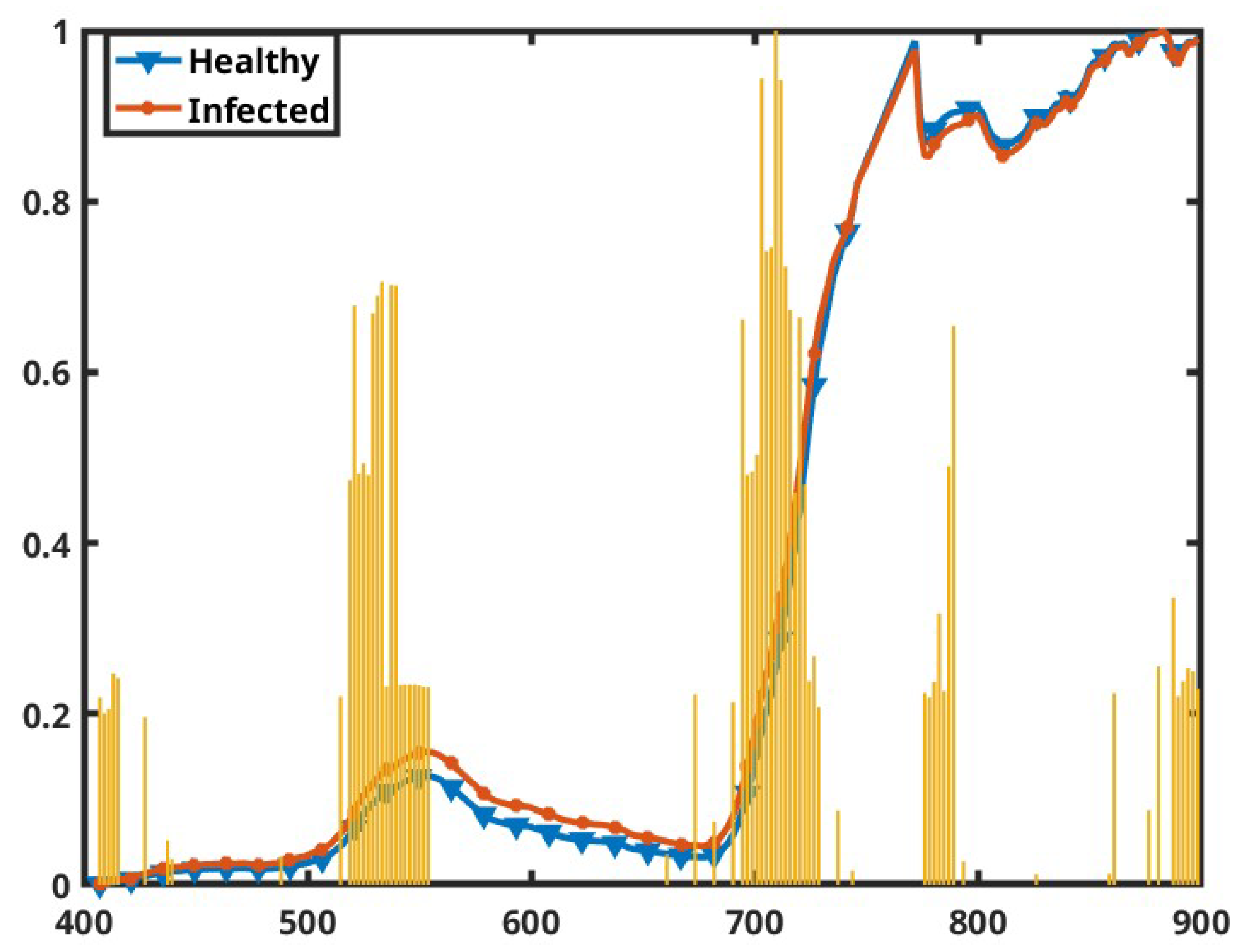

3.5. Feature Importance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGL | Above Ground Level |

| BART | Bozeman Agricultural Research and Teaching |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CVAT | Computer Vision Annotation Tool |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| DRN | Dark Red Norland |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| FNN | Feed-forward Neural Network |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HSI | Hyperspectral Imaging |

| IC | Immunochromatography |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| KNN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MRMR | Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance |

| NCA | Neighborhood Component Analysis |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| NN | Neural Network |

| PBS | Phosphate Buffer Saline |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PVY | Potato Virus Y |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SVD | Singular Value Decomposition |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SWIR | Shortwave Infrared |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles |

| UMA | Umatilla |

| Vis-NIR | Visible and Near-Infrared |

References

- Crosslin, J.M. PVY: An old enemy and a continuing challenge. American journal of potato research 2013, 90, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glais, L.; Bellstedt, D.U.; Lacomme, C. Diversity, characterisation and classification of PVY. Potato virus Y: biodiversity, pathogenicity, epidemiology and management, 2017; pp. 43–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wani, S.; Saleem, S.; Nabi, S.U.; Ali, G.; Paddar, B.A.; Hamid, A. Distribution and molecular characterization of potato virus Y (PVY) strains infecting potato (Solanum tuberosum) crop in Kashmir (India). VirusDisease 2021, 32, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupuis, B.; Nkuriyingoma, P.; Ballmer, T. Economic impact of potato virus Y (PVY) in Europe. Potato Research 2024, 67, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glais, L.; Chikh Ali, M.; Karasev, A.V.; Kutnjak, D.; Lacomme, C. Detection and diagnosis of PVY. Potato virus Y: Biodiversity, pathogenicity, epidemiology and management, 2017; pp. 103–139. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, T.D.; Nie, X.; Singh, M. RT-PCR and real-time RT-PCR methods for the detection of potato virus Y in potato leaves and tubers. Plant Virology Protocols: New Approaches to Detect Viruses and Host Responses, 2015; pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Tiwari, R.K.; Sundaresha, S.; Kaundal, P.; Raigond, B. Potato viruses and their management. In Sustainable management of potato pests and diseases; Springer, 2022; pp. 309–335.

- Afzaal, H.; Farooque, A.A.; Schumann, A.W.; Hussain, N.; McKenzie-Gopsill, A.; Esau, T.; Abbas, F.; Acharya, B. Detection of a potato disease (early blight) using artificial intelligence. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhou, J.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Y.; Pan, B.; Zhang, Z. A review of remote sensing for potato traits characterization in precision agriculture. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 871859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslemkhani, C.; Hassani, F.; Azar, E.N.; Khelgatibana, F. Potential of spectroscopy for differentiation between PVY infected and healthy potato plants. Crop Prot 2019, 8, 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, R.C. Prediction of yield and diseases in crops using vegetation indices through satellite image processing. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Technology and Engineering Management Society (TEMSCON LATAM). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mukiibi, A.; Machakaire, A.; Franke, A.; Steyn, J. A Systematic Review of Vegetation Indices for Potato Growth Monitoring and Tuber Yield Prediction from Remote Sensing. Potato Research, 2024; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Khojastehnazhand, M.; Khoshtaghaza, M.H.; Mojaradi, B.; Rezaei, M.; Goodarzi, M.; Saeys, W. Comparison of visible–near infrared and short wave infrared hyperspectral imaging for the evaluation of rainbow trout freshness. Food Research International 2014, 56, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesar, S.; Whitaker, B.; Zidack, N.; Nugent, P. Hyperspectral remote sensing approach for rapid detection of potato virus Y. In Proceedings of the Photonic Technologies in Plant and Agricultural Science. SPIE, Vol. 12879; 2024; pp. 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.; Li, Y.; Song, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Song, L.; Bai, B.; Tu, K.; Lan, W.; Pan, L. Study on black spot disease detection and pathogenic process visualization on winter jujubes using hyperspectral imaging system. Foods 2023, 12, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Vinatzer, B.A.; Li, S. Hyperspectral imaging analysis for early detection of tomato bacterial leaf spot disease. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 27666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.; Sagan, V.; Maimaitiyiming, M.; Maimaitijiang, M.; Bhadra, S.; Kwasniewski, M.T. Early detection of plant viral disease using hyperspectral imaging and deep learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.K.; Burks, T.; Frederick, Q.; Qin, J.; Kim, M.; Ritenour, M.A. Citrus disease detection using convolution neural network generated features and Softmax classifier on hyperspectral image data. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 1043712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Al-Sarayreh, M.; Irie, K.; Hackell, D.; Bourdot, G.; Reis, M.M.; Ghamkhar, K. Identification of weeds based on hyperspectral imaging and machine learning. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 11, 611622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Prabhu, A.; Solanki, V. Automating Weed Detection Through Hyper Spectral Image Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Optimization Computing and Wireless Communication (ICOCWC). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.; Huang, Y.; Chunjiang, Z.; Xiu, W. Identification of seedling cabbages and weeds using hyperspectral imaging. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 2015, 8, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yin, T. Advancements in Hyperspectral Imaging for Assessing Nutritional Parameters in Muscle Food: Current Research and Future Trends. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Z.; Lin, C.; Hu, Y.; Liu, L. Estimation of soil nutrient content using hyperspectral data. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, V.X.; Dhandapani, S.; Ang Jie, R.; Philip, V.S.; Teo Ju Teng, M.; Zhang, S.; Park, B.S.; Olivo, M.; Dinish, U. Early detection of N, P, K deficiency in Choy Sum using hyperspectral imaging-based spatial spectral feature mining. Frontiers in Photonics 2024, 5, 1418246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshkabilov, S.; Stenger, J.; Knutson, E.N.; Küçüktopcu, E.; Simsek, H.; Lee, C.W. Hyperspectral image data and waveband indexing methods to estimate nutrient concentration on lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) cultivars. Sensors 2022, 22, 8158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Nie, J.; Nan, T.; Huang, L.; Yang, J. Nutrient content prediction and geographical origin identification of red raspberry fruits by combining hyperspectral imaging with chemometrics. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022, 9, 980095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, N.; Whitworth, M.B.; Fisk, I.D. Protein content prediction in single wheat kernels using hyperspectral imaging. Food chemistry 2018, 240, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; He, X.; Cheng, X.; Li, P.; Luo, H.; Tian, Z.; Guo, H. Exploiting hierarchical features for crop yield prediction based on 3-d convolutional neural networks and multikernel gaussian process. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2021, 14, 4476–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qu, Y.; Ma, F.; Lv, Q.; Zhu, X.; Guo, G.; Li, M.; Yang, W.; Que, B.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Integrating high-throughput phenotyping and genome-wide association studies for enhanced drought resistance and yield prediction in wheat. New Phytologist 2024, 243, 1758–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, S.; Wendel, A.; Underwood, J. Ground based hyperspectral imaging for extensive mango yield estimation. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 157, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Biswas, A.; Hong, Y.; Chen, S.; Hu, B.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Li, S. Enhancing soil profile analysis with soil spectral libraries and laboratory hyperspectral imaging. Geoderma 2024, 450, 117036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, M.; Shi, X. Hyperspectral imaging for high-resolution mapping of soil carbon fractions in intact paddy soil profiles with multivariate techniques and variable selection. Geoderma 2020, 370, 114358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Qiu, Z.; He, Y. Transfer learning strategy for plastic pollution detection in soil: Calibration transfer from high-throughput HSI system to NIR sensor. Chemosphere 2021, 272, 129908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Tong, R.; Li, Q. Hyperspectral imaging analysis for the classification of soil types and the determination of soil total nitrogen. Sensors 2017, 17, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffel, L.M.; Delparte, D.; Whitworth, J.; Bodily, P.; Hartley, D. Evaluation of artificial neural network performance for classification of potato plants infected with potato virus Y using spectral data on multiple varieties and genotypes. Smart Agricultural Technology 2023, 3, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polder, G.; Blok, P.M.; De Villiers, H.A.; Van der Wolf, J.M.; Kamp, J. Potato virus Y detection in seed potatoes using deep learning on hyperspectral images. Frontiers in plant science 2019, 10, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Duan, H. Classification of hyperspectral images by SVM using a composite kernel by employing spectral, spatial and hierarchical structure information. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.; Shafri, H.Z.; Habshi, M. A comparison between support vector machine (SVM) and convolutional neural network (CNN) models for hyperspectral image classification. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publishing, Vol. 357; 2019; p. 012035. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Cheng, L.; Yong, B. Spectral-similarity-based kernel of SVM for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhao, X.; Yang, D.; Bai, Y. Hyperspectral image classification with SVM and guided filter. EURASIP Journal on Wireless Communications and Networking 2019, 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. Hyperspectral image classification based on convolutional neural network and random forest. Remote sensing letters 2019, 10, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Q. Fast spatial-spectral random forests for thick cloud removal of hyperspectral images. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2022, 112, 102916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Zhang, Y. Exploiting spectral–spatial information using deep random forest for hyperspectral imagery classification. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2021, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cao, G.; Li, X.; Wang, B.; Fu, P. Active semi-supervised random forest for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Yan, L.; Fang, H.; Zhong, S.; Liao, W. HSI-DeNet: Hyperspectral image restoration via convolutional neural network. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2018, 57, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Li, B.; Chen, H. Multi-scale 3D deep convolutional neural network for hyperspectral image classification. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). IEEE; 2017; pp. 3904–3908. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Fang, L.; Ghamisi, P. Deformable convolutional neural networks for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2018, 15, 1254–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayesha, S.; Hanif, M.K.; Talib, R. Overview and comparative study of dimensionality reduction techniques for high dimensional data. Information Fusion 2020, 59, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M. Early detection of virus infections in potato by aphids and infrared remote sensing. SLU, Dept. of Crop Production Ecology, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Griffel, L.; Delparte, D.; Edwards, J. Using Support Vector Machines classification to differentiate spectral signatures of potato plants infected with Potato Virus Y. Computers and electronics in agriculture 2018, 153, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Han, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Jiang, L.; Huang, K.; Wang, H.; Guo, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Classification models for Tobacco Mosaic Virus and Potato Virus Y using hyperspectral and machine learning techniques. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1211617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AgEagle Aerial Systems. Altum-PT Camera. https://ageagle.com/drone-sensors/altum-pt-camera/. Accessed: 2024-12-20.

- Funke, C.N.; Tran, L.T.; Karasev, A.V. Screening Three Potato Cultivars for Resistance to Potato Virus Y Strains: Broad and Strain-Specific Sources of Resistance. American Journal of Potato Research 2024, 101, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondakova, O.; Butenko, K.; Skurat, E.; Drygin, Y.F. Molecular diagnostics of potato infections with PVY and PLRV by immunochromatography. Moscow University Biological Sciences Bulletin 2016, 71, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Santos-Rojas, J. Detection of potato virus Y in primarily infected mature plants by ELISA, indicator host, and visual indexing. Canadian plant disease survey 1983, 63, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Vision Aerial. Vector Hexacopter Drone. https://visionaerial.com/vector/. Accessed: 2024-12-18.

- Resonon. Pika L Hyperspectral Imaging Camera. https://resonon.com/Pika-L. Accessed: 2024-12-18.

- Resonon. Hyperspectral Imaging Software. https://resonon.com/software. Accessed: 2024-12-18.

- DJI. Matrice 600 - Product Support. https://www.dji.com/support/product/matrice600. Accessed: 2024-12-20.

- Liang, S. Quantitative remote sensing of land surfaces; John Wiley & Sons, 2005.

- Schowengerdt, R.A. Remote sensing: models and methods for image processing; elsevier, 2006.

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M.J. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Analytical chemistry 1964, 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Tang, L.; Hupy, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Shao, G. A commentary review on the use of normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) in the era of popular remote sensing. Journal of Forestry Research 2021, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, M.S.; Singh, M.; Nanayakkara, U.; Pelletier, Y.; Nie, X.; Wattie, D. Monitoring current-season spread of Potato virus Y in potato fields using ELISA and real-time RT-PCR. Plant Disease 2013, 97, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Somerville, T. Evaluation of the enzyme-amplified ELISA for the detection of potato viruses A, M, S, X, Y, and leafroll. American Potato Journal 1992, 69, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CVAT.ai. CVAT: Computer Vision Annotation Tool. https://www.cvat.ai/. Accessed: 2024-12-20.

- Hearst, M.A.; Dumais, S.T.; Osuna, E.; Platt, J.; Scholkopf, B. Support vector machines. IEEE Intelligent Systems and their applications 1998, 13, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, A.J.; Feudale, R.N.; Liu, Y.; Woody, N.A.; Brown, S.D. An introduction to decision tree modeling. Journal of Chemometrics: A Journal of the Chemometrics Society 2004, 18, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, G.; Silva, D.F.; et al. How k-nearest neighbor parameters affect its performance. In Proceedings of the Argentine symposium on artificial intelligence. Citeseer; 2009; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum, D.G.; Dietz, K.; Gail, M.; Klein, M.; Klein, M. Logistic regression; Springer, 2002.

- Goodfellow, I. Deep learning, 2016.

- Aloysius, N.; Geetha, M. A review on deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 international conference on communication and signal processing (ICCSP). IEEE; 2017; pp. 0588–0592. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, L.; Li, H.; Shang, W.; Ma, L. An empirical study of the impact of hyperparameter tuning and model optimization on the performance properties of deep neural networks. ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology (TOSEM) 2022, 31, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shami, A. On hyperparameter optimization of machine learning algorithms: Theory and practice. Neurocomputing 2020, 415, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesar, S.B.; Whitaker, B.M.; Maher, R.C. Machine Learning Analysis on Gunshot Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2024 Intermountain Engineering, Technology and Computing (IETC). IEEE; 2024; pp. 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Bayes, T. An essay towards solving a problem in the doctrine of chances. Biometrika 1958, 45, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M.; Lapalme, G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Information processing & management 2009, 45, 427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, D.M. Evaluation: from precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.16061, arXiv:2010.16061 2020.

- Salimi, A.; Ziaii, M.; Amiri, A.; Zadeh, M.H.; Karimpouli, S.; Moradkhani, M. Using a Feature Subset Selection method and Support Vector Machine to address curse of dimensionality and redundancy in Hyperion hyperspectral data classification. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science 2018, 21, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jović, A.; Brkić, K.; Bogunović, N. A review of feature selection methods with applications. In Proceedings of the 2015 38th international convention on information and communication technology, electronics and microelectronics (MIPRO). Ieee; 2015; pp. 1200–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Motoda, H. Computational methods of feature selection; CRC press, 2007.

- Peng, H.; Long, F.; Ding, C. Feature selection based on mutual information criteria of max-dependency, max-relevance, and min-redundancy. IEEE Transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2005, 27, 1226–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golugula, A.; Lee, G.; Madabhushi, A. Evaluating feature selection strategies for high dimensional, small sample size datasets. In Proceedings of the 2011 Annual International conference of the IEEE engineering in medicine and biology society. IEEE; 2011; pp. 949–952. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Motoda, H. Feature selection for knowledge discovery and data mining; Vol. 454, Springer science & business media, 2012.

- Tuncer, T.; Ertam, F. Neighborhood component analysis and reliefF based survival recognition methods for Hepatocellular carcinoma. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2020, 540, 123143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).