1. Introduction

The analysis of backward air mass trajectories has emerged as a pivotal tool in atmospheric sciences, enabling researchers to identify and trace pollutant pathways, determine source regions, and assess their impacts on air quality. Models such as HYSPLIT [

1] and FLEXPART [

2] integrate meteorological data to compute air mass trajectories, providing valuable insights into the dynamics of pollution transport.

One of the key advantages of back-trajectory analysis is its ability to track the relationships between emission sources and receptor locations over long distances, rendering it highly beneficial for the study of transboundary air pollution. This utility is demonstrated in research examining the impacts of air pollution in remote regions such as the Arctic or the Mediterranean [

3,

4]. Back-trajectories are also effective in identifying episodic pollution events, wherein specific sources substantially contribute to elevated pollutant concentrations. For example, in urban settings, back-trajectory analysis has been utilized to ascertain the impact of emissions originating from industrial zones, transportation networks, and adjacent regions on local air quality [

5], identify sources of pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls in Chicago [

6] and halogenated greenhouse gases in the European Union [

7]. Furthermore, it has been instrumental in the examination of seasonal variations in pollutant sources, as varying meteorological conditions can modify the trajectories and mixing of air masses, consequently leading to distinct pollution profiles across different seasons [

8].

Despite notable advancements in understanding air pollution, significant gaps persist, particularly in regions with dense urbanization and industrialization. In Southern Italy, for instance, elevated temperatures and sea breezes exacerbate the transport of particulate matter from nearby industrial areas, worsening urban air quality [

9,

10,

11]. The most recent European Air Quality Status report [

12] reveals that, despite improvements in overall air quality, a significant portion of the urban population in the Mediterranean region continues to be exposed to dangerous levels of fine particulate matter, with 96% of European urban areas exceeding the guidelines established by the World Health Organization [

13].

The Mediterranean basin, often exposed to transboundary pollution from Europe, Northern Africa, and local sources, presents a complex case for air quality studies. Previous studies have explored the impacts of Saharan dust transport on particulate matter [

14,

15] and the contributions of transboundary pollution to Mediterranean air quality [

16,

17]. However, limited research has focused on integrating long-term, high-resolution trajectory analyses with detailed assessments of local emission influences and seasonal transport variations within the central Mediterranean region. This study addresses these gaps by providing an integrated analysis of air mass transport and PM

10 concentrations at the Pomigliano d’Arco monitoring site, located near Naples in Southern Italy, over a six-year period (2018–2023), thereby ensuring a representative dataset for examining temporal and spatial trends. We applied advanced backward trajectory analysis, cluster analysis, and residence time analysis to identify dominant pollutant transport pathways and their seasonal dynamics. Our study includes the integration of long-term trajectory data with local emission influences, a detailed assessment of the role of residence time in pollutant accumulation, and the identification of transboundary pollution patterns in a highly urbanized setting.

By bridging the knowledge gap between local and regional pollutant dynamics, this research provides critical insights into the atmospheric processes driving PM10 concentrations in the central Mediterranean, offering evidence-based guidance for mitigation strategies and regulatory improvements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Atmospheric Measurements

The data for this study were collected within the MonAir Project, which focuses on characterizing particulate matter in the urban environment of Pomigliano D’Arco, a highly urbanized and industrialized municipality east of Naples, Southern Italy (see

Figure 1). Sampling and measurements were conducted on the rooftop of the City Hall building. Each sampling session lasted 24 hours, with a daily air volume of 54.7 m

3. Measurements spanned from January 2018 to December 2023. 24-hour PM

10 concentration determinations (midnight to midnight) were performed using a low-volume gravimetric sampler equipped with a 10

m cut-off inlet. The instrument, a dual-channel beta attenuation monitor (SWAM5a Dual Channel Monitor, FAI Instruments, Italy), operated at a flow rate of 2.3 m

3h

−1. A 47 mm diameter quartz microfiber filter was used for collection. The instrument is TÜV- and CERT-certified as a beta monitor and complies with EU equivalence criteria for PM measurements, following EN 12341 and EN 14907 reference methods [

18].

2.2. The Backward Trajectory Method

In this work, ten-day (240-hour) backward trajectories were determined through the numerical integration of trajectory equations. The calculation of backward air mass trajectories was conducted using the HYSPLIT 5.3.2 model (developed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Air Resources Laboratory (ARL), see

https://www.ready.noaa.gov/HYSPLIT.php, [

1,

19].

Airmass histories were based on the use of the 3-hourly meteorological data coming from the NCEP’s GDAS (The National Center for Environmental Prediction, Global Data Assimilation System). The NCEP collects meteorological data and performs computational analyses to generate weather forecasts four times daily. After analysis, data are converted from their initial spectral coefficient format into lat-long regular grids, at a

resolution, from sigma levels to mandatory pressure levels, and archived at the ARL. This process ensures that the data is formatted in a way that can be effectively used for predicting and understanding atmospheric conditions over time. Further information about this system is available on the ARL website (

https://www.ready.noaa.gov/gdas1.php).

Backward trajectories started from the monitoring site in Pomigliano d’Arco, hereafter referred to as PdA, (40.907165N, 14.392612E), during the period from January 2018 to December 2023. Each air mass history was composed of an ensemble of 75 trajectories, with starting points uniformly distributed between 100 meters and 1950 meters above ground level at PdA. These trajectories were launched every six hours, resulting in four trajectory ensembles for each 24-hour sampling period. At 5-minute intervals along each trajectory, the three-dimensional position of the trajectory segment, temperature, humidity, and the height of the mixed layer were recorded.

2.3. Cluster Analysis

Cluster analysis was used to identify groups of airflow patterns that influenced the air quality at the PdA site. The HYSPLIT cluster analysis option was employed on the computed backward trajectories [

20]. The clustering of trajectories was executed utilizing the total spatial variance (TSV) method, wherein clusters were aggregated through the minimization of the TSV, specifically, the sum of all within-cluster variances.

The clustering process initiated by assigning each trajectory to an individual `cluster’. Subsequently, the two clusters exhibiting the lowest increase in TSV were aggregated to form a pair, and the two clustered trajectories were replaced by their mean trajectory for further calculation. This process continued until the final merging of the last two clusters, resulting in the aggregation of all trajectories into a single cluster. The optimal number of clusters was ascertained by selecting the initial variation in the TSV between clusters that exceeded 30% within the last ten combinations. In this work, seven clusters were retained for the final analysis.

To determine the frequency of each air mass pattern over the analyzed period, and to avoid the potential for erroneous interpretations by assigning the same day to multiple airflow patterns, we exploited the concept of `core-day’ for identifying persistent airflow days [

21]. Initially, the entire dataset underwent a classification procedure. Subsequently, if the majority of ensemble members corresponding to a particular day were categorized within the same cluster, the assignment was deemed robust, designating that day as a `core-day’. Conversely, if the day did not meet these criteria, it was excluded from further analysis due to the assignment’s higher sensitivity to variability in the input data. A `core-day’ was characterized by a condition whereby at least 50% of the trajectories reaching PdA on a given day are assigned to the same cluster [

22,

23]. Application of this criterion revealed 1050 persistent days, accounting for 71% of the entire sampling period.

2.4. Residence Time Analysis

Residence time analysis (RT), originally introduced by [

24,

25], and subsequently refined by [

26], was employed to quantify the duration air masses spend over specific regions prior to reaching the PdA site.

The RT method overlays a grid on the region of interest and calculates the frequency and duration of trajectory endpoints within each grid cell. The result is a probability density function (

pdf) that identifies regions where air masses are more likely to accumulate or stagnate. The ridges of high probability in the

pdf effectively delineate dominant pathways, enabling the inference of which regions are most influential in contributing to pollutant concentrations [

24].

The derivation of the

pdf governing the residence time analysis is provided in

Appendix A. Let

denote the

pdf of residence times at a distance

r and direction

from the receptor. Following [

27],

can be decomposed into `directional frequency’ and `potential accumulation’ components (see equations (

A3) and (

A4)). The directional frequency represents the occurrence rate of transport between a source at (

) and the receptor per unit arc length. Potential accumulation, defined as the inverse transport speed, indicates the average time air parcels reside over a unit radial length: the slower an air parcel moves over a region, the longer the time emissions in that region can accumulate in the air parcel.

The RT analysis can also be refined to assess variations in transport pathways with PM concentrations. To this end, we compute the ratio:

where

is the

pdf of residence times for selected events, while

corresponds to all events. The ratio

identifies key source regions and transport dynamics contributing to pollution extremes. If

, residence times in the region (

) exceed the expected average, suggesting a preferential transport pathway. Conversely,

indicates shorter residence times relative to the baseline.

We conducted a residence time analysis for trajectories associated with high and low PM10 concentrations, specifically when corresponds to events above the 80th percentile and when it corresponds to events below the 20th percentile at the receptor site. This approach quantitatively assesses deviations in residence time distributions under specific conditions, offering insights into atmospheric transport mechanisms. Additionally, comparing across regions provides a direct measure of their relative contributions to high/low concentrations at the receptor.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of PM10 Concentrations

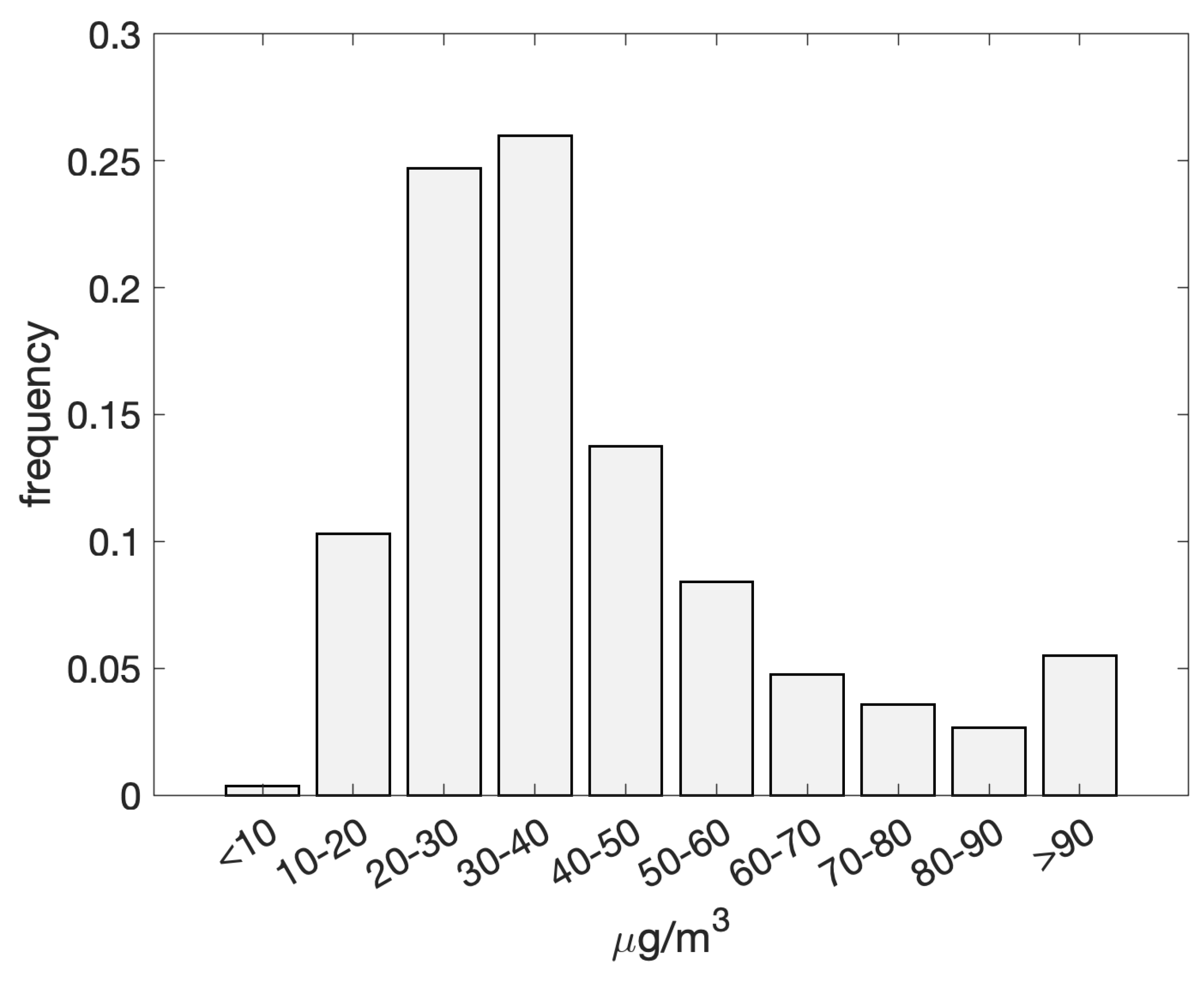

The distribution of daily PM

10 concentrations recorded at the PdA monitoring site over the six-year period (2018–2023) is shown in

Figure 2. The total number of valid data points amounts to 1,620. Concentration levels display a pronounced peak within the 30–40

g/m

3 range, occurring in over 25% of cases, followed by the 20–30

g/m

3 range. As concentrations rise, the frequency exhibits a monotonic decline; nonetheless, a significant secondary peak is detected for occurrences exceeding 90

g/m

3, with over 5% of concentrations above this threshold.

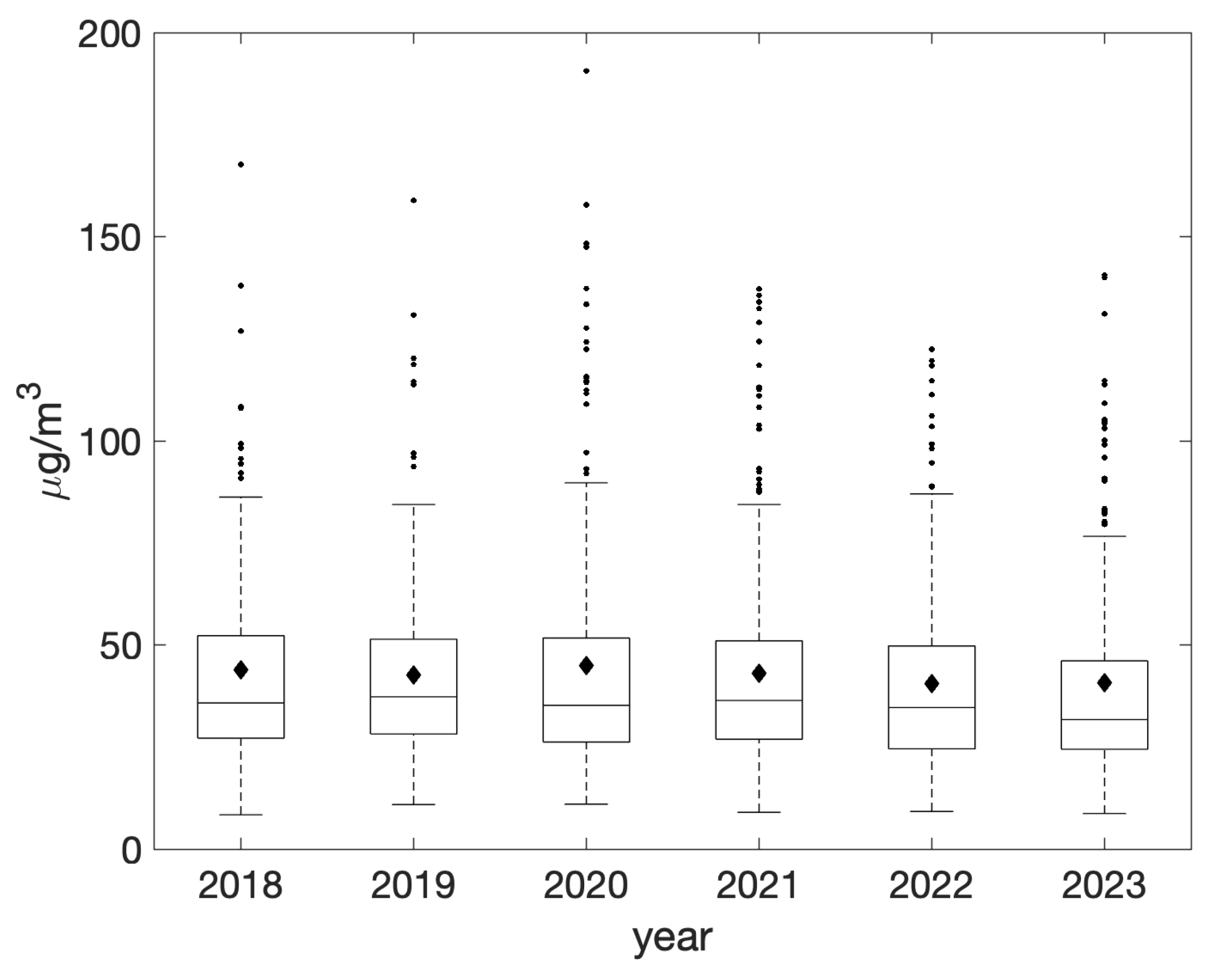

Throughout the analyzed period, annual averages consistently exceeded the EU limit of 40

g/m

3, with a maximum of 44.9

g/m

3 recorded in 2020 (

Figure 3). It is noteworthy that annual averages have demonstrated a consistent decrease, reaching a minimum value of 40.7

g/m

3 in 2023. Nevertheless, these concentrations persisted at levels considerably exceeding the annual average objective of 20

g/m

3 advocated by the new EU directive, which aims to be attained by 2030 [

28].

The maximum and minimum number of days exceeding the EU daily threshold of 50 —which should not be surpassed more than 35 times per year—occurred in 2019 and 2023, with 98 and 78 days, respectively.

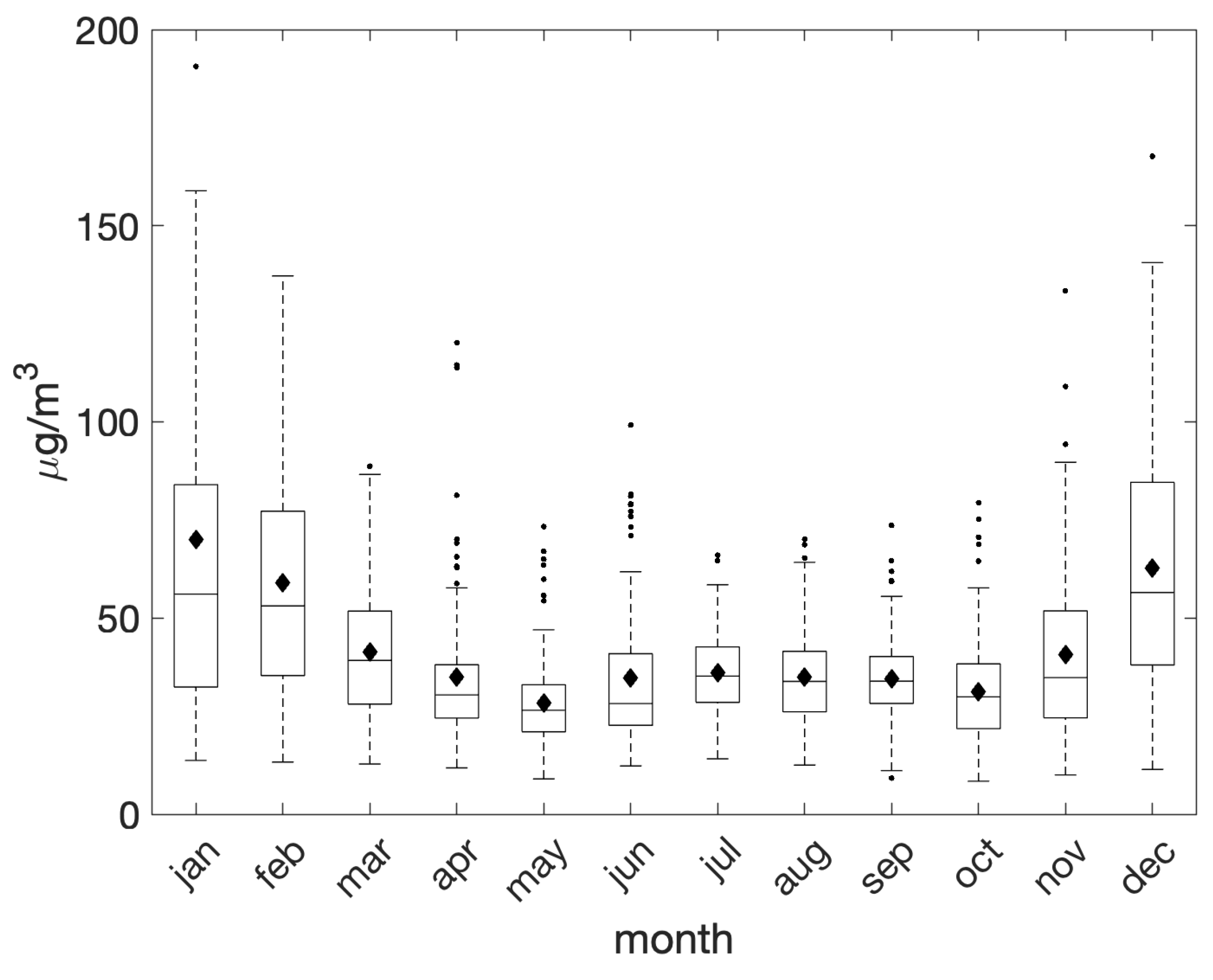

The monthly average PM

10 concentrations exhibited a pronounced peak during the winter months (December, January, and February),

Figure 4, consistently exceeding the mean level of 55

across all three months. This trend is followed by a gradual decline, with the lowest concentrations recorded in May, and a slight increase during the summer months, probably due to the enhanced photochemical activity and secondary aerosol formation prompted by elevated temperatures and sunlight [

29]. However, considerable monthly variability in the frequency of exceedance days was observed, with a notable concentration of anomalies during the winter months.

3.2. Airflow Paths

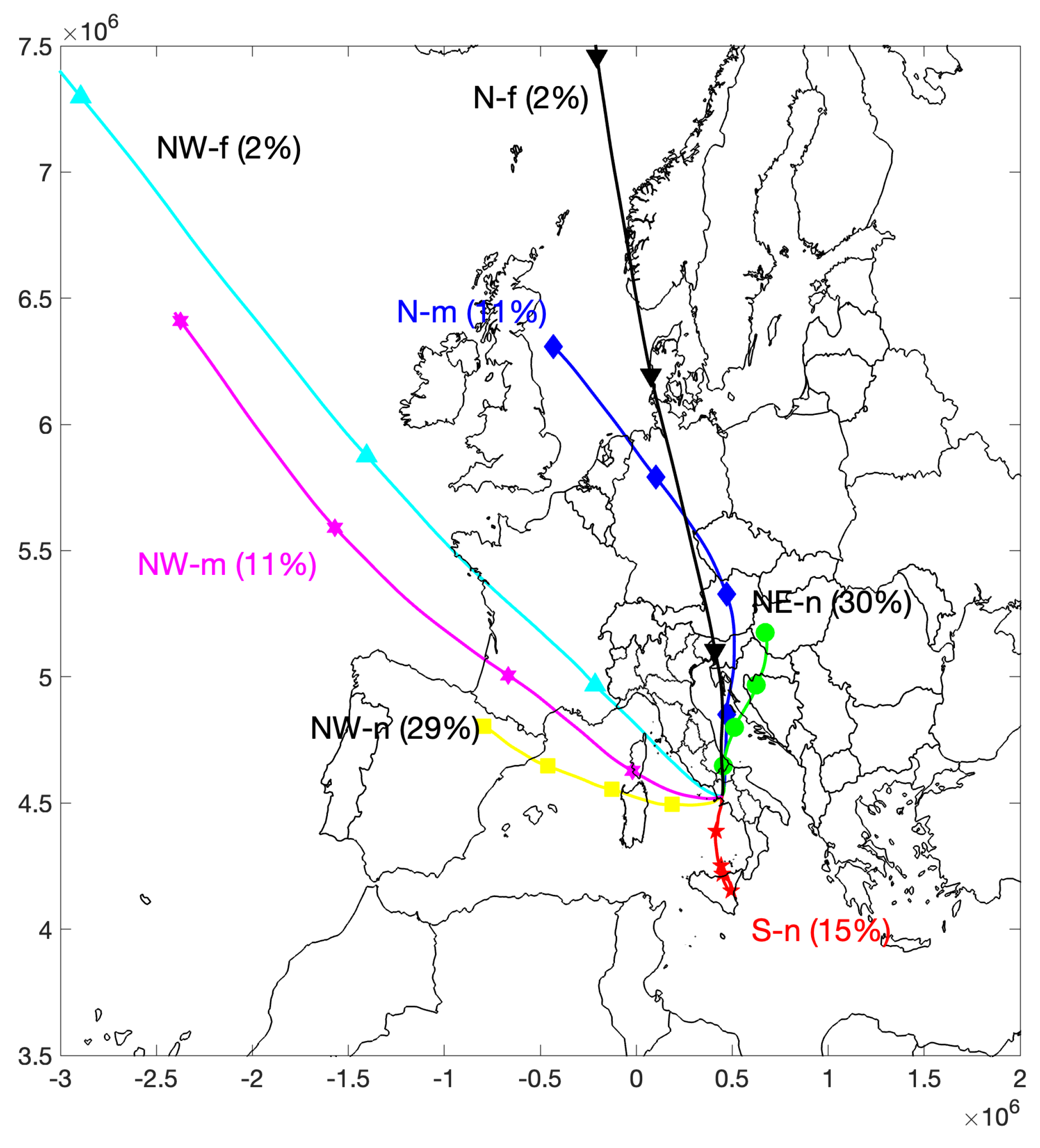

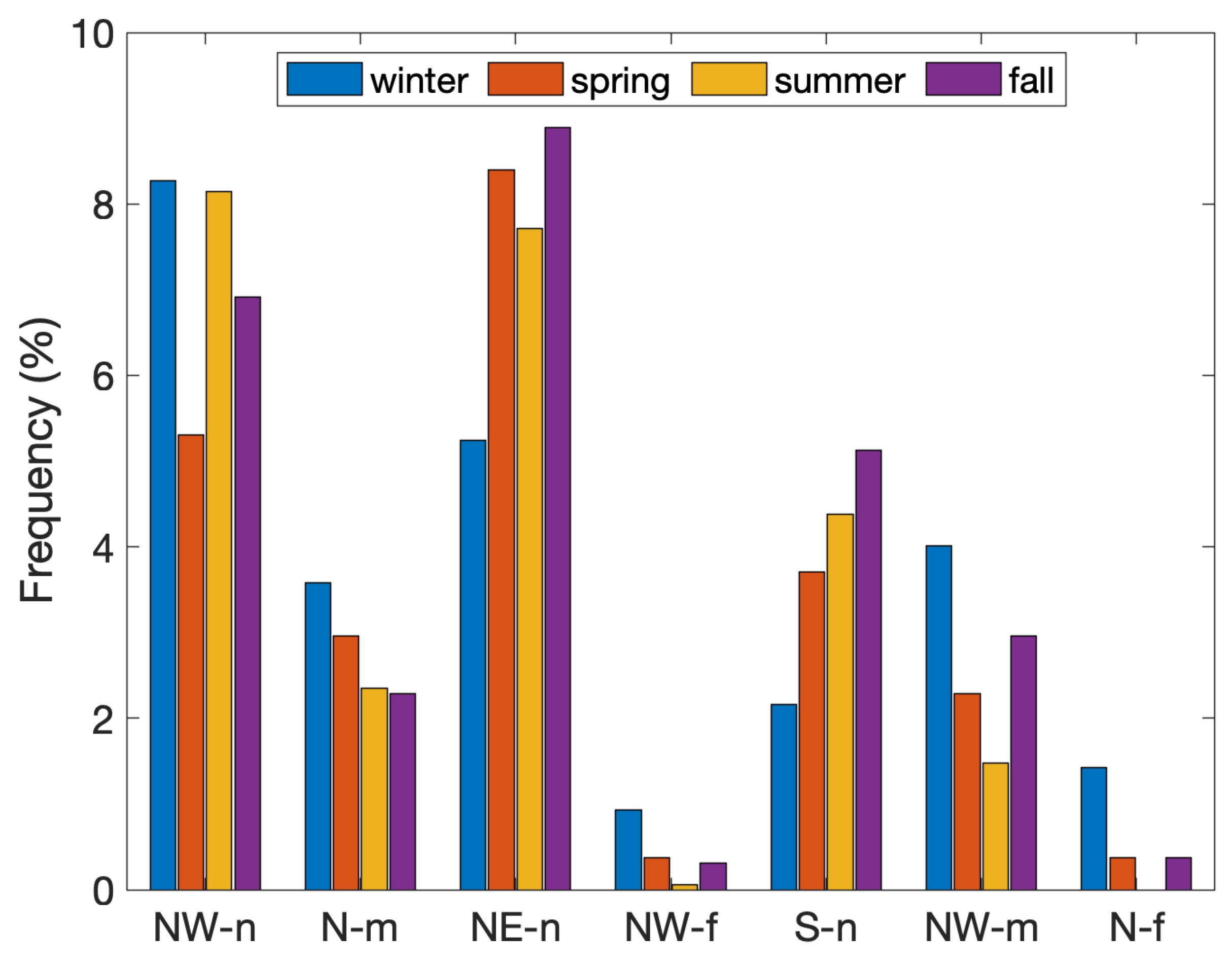

The cluster analysis of backward trajectories identified seven distinct airflow patterns influencing the PdA site, as depicted in

Figure 5, showing their horizontal mean displacements throughout the stated period. The clusters were tagged according to their geographical origin and displacement relative to the source. Three clusters were characterized as northwesterly airflow, designated as NW-f (Northwest-far), NW-m (Northwest-medium), and NW-n (Northwest-nearby), while three additional clusters originated from the north, identified as N-f (North-far), N-m (North-medium), and NE-n (Northeast-nearby). Another cluster was associated with a southerly flow (S-nearby).

Figure 5 also displays the frequencies of occurrence for each cluster. The most frequent occurrences were for the NW-n and NE-n clusters, with frequencies of 29% and 30% respectively. Infrequently, trajectories originated from the N-f and NW-f clusters, whereas the NW-m and N-m clusters showed intermediate frequencies of occurrence.

Figure 6 depicts the seasonal dynamics of airflow trajectories impacting PdA throughout the study period. This figure highlights the differences in the dynamic origin of air masses impacting the site, incorporating local circulations, short-range flows from the north and west, and sporadic long-range transport. These distinct airflow patterns exhibit pronounced seasonal variability. Local circulations have emerged as the dominant feature of airflow patterns, exerting a consistent influence on PdA; these circulations account for a substantial proportion of airflows across all seasons, indicative of the influence of localized meteorological dynamics, such as topographical effects and thermal inversions, prevalent in regions with complex terrain, such as the area surrounding PdA. Specifically, nearby circulations from the north-east maintained a relatively stable influence throughout the seasons, contributing between

of total trajectories in winter and

in fall. This stability underscores the persistent nature of these circulations, likely associated with regional mesoscale weather patterns.

Airflows originating from the south exhibited a notable seasonal variation. During the winter months, southerly trajectories contributed minimally, averaging approximately

. However, these flows increased in frequency during the summer and fall seasons, peaking at around

, likely attributable to the heightened influence of convective processes and alterations in regional pressure gradients during warmer months. In contrast, northerly and north-westerly airflows exhibited a stronger influence during the winter, contributing on average

of the total airflow. This seasonal predominance of northern air masses corresponds with the increased occurrence of cold front passages and high-pressure systems over central and southern Europe during winter, which often facilitate the advection of air masses from northern latitudes [

30].

3.3. Residence Time Analysis

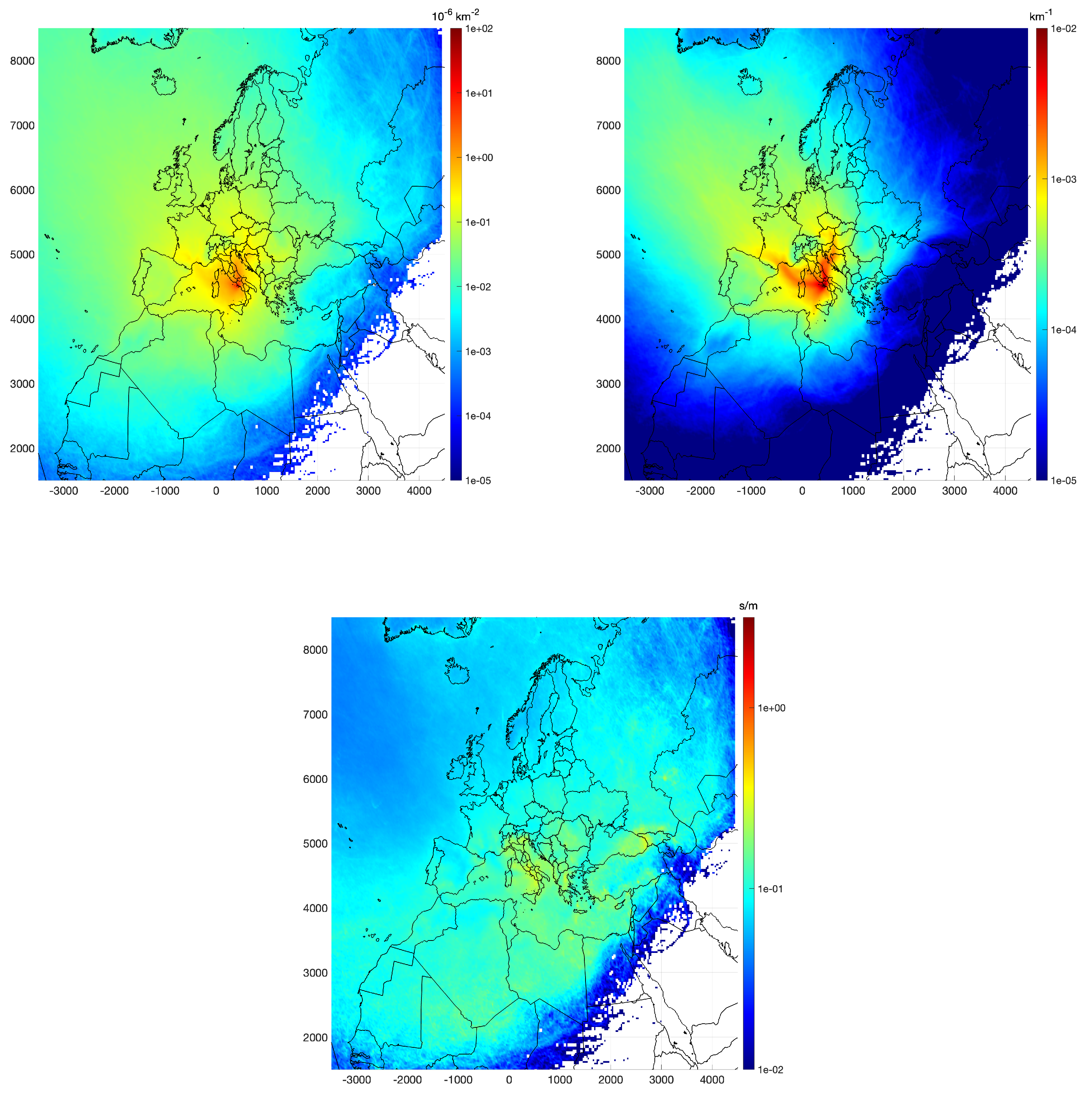

As described in

Appendix A, a probability map can be constructed and projected onto the Earth’s surface. To this end, trajectory endpoints were used to estimate the residence time (RT) probability map onto a regular

km grid resolution (in UTM33 coordinates). To ensure the reliability of the analysis, uncertainties from the ensemble were addressed by the bootstrap method [

31], by resampling the sample data (with replacement) among all trajectories belonging to the 75 members of each ensemble and performing inference about a sample from resampled data. Retention of the

values for the residence time was conditioned on the cells with a mean value exceeding twice the estimated standard deviation.

The residence time calculation was conducted for three distinct sets of trajectories. A comprehensive residence time analysis was executed for the whole 6-year period. Subsequently, a second analysis focused on the subset of trajectories that reached PdA when PM

10 concentrations exceeded the 80th percentile of the time series, and thirdly, a subset of trajectories when PM

10 concentrations were below the 20th percentile. The RT

pdfs derived from each of these analyses (and their decomposition into directional and accumulation potential, see equation

A7), provide insights into the geographical areas where air parcels influencing the receptor site most likely spent their time prior to the arrival at PdA during average, high and low pollution events.

Figure 7 represents the

pdf for RT on a logarithmic color scale for the whole set of trajectories. As depicted, the predominant directions of arrival are from the northeasterly and westerly directions, corroborating the findings already found from cluster means in

Figure 5, which reflect a similar pattern. This is consistent with a predominant influence of air masses originating from the northeastern part of Europe and from the western Mediterranean basin to PdA, usually associated with localized atmospheric circulations, including cyclonic or anti-cyclonic patterns and low wind conditions. The sharp gradient in residence times observed along geographical boundaries, such as the Alpine region, indicates the role of topography in modulating air mass transport pathways, potentially acting as a barrier to long-range advection, with little to no transport through this boundary. Lower residence times in areas such as northern Europe and southeastern regions of the Mediterranean basin contribute less frequently to the air composition at the receptor site during the analyzed period. The southeastern regions of the Mediterranean basin often exhibit nonsignificant values. Furthermore, the distribution underscores the influence of the central Mediterranean as a source or reservoir of atmospheric pollutants, with implications for air quality at this receptor site. High RT values in this region, due to the prevalence of nearby circulation patterns, point to stagnation events that enhance pollutant accumulation or recirculation.

The spatial patterns in the RT and transport directional frequency are quite similar (

Figure 7). Therefore, the RT is predominantly due to the frequency at which trajectories traverse a given area prior to reaching the receptor. The distribution of accumulation potential exhibits considerable heterogeneity, with the most elevated values located within a band across the Italian peninsula, ranging from over 0.1 to 0.5 s/m, corresponding to effective airmass transport velocities of approximately 2 to 10 m/s. Notably, accumulation potentials are also observed over the Balkan region and the northern sector of the Saharan desert in areas identified by [

32] as source regions in northern Africa.

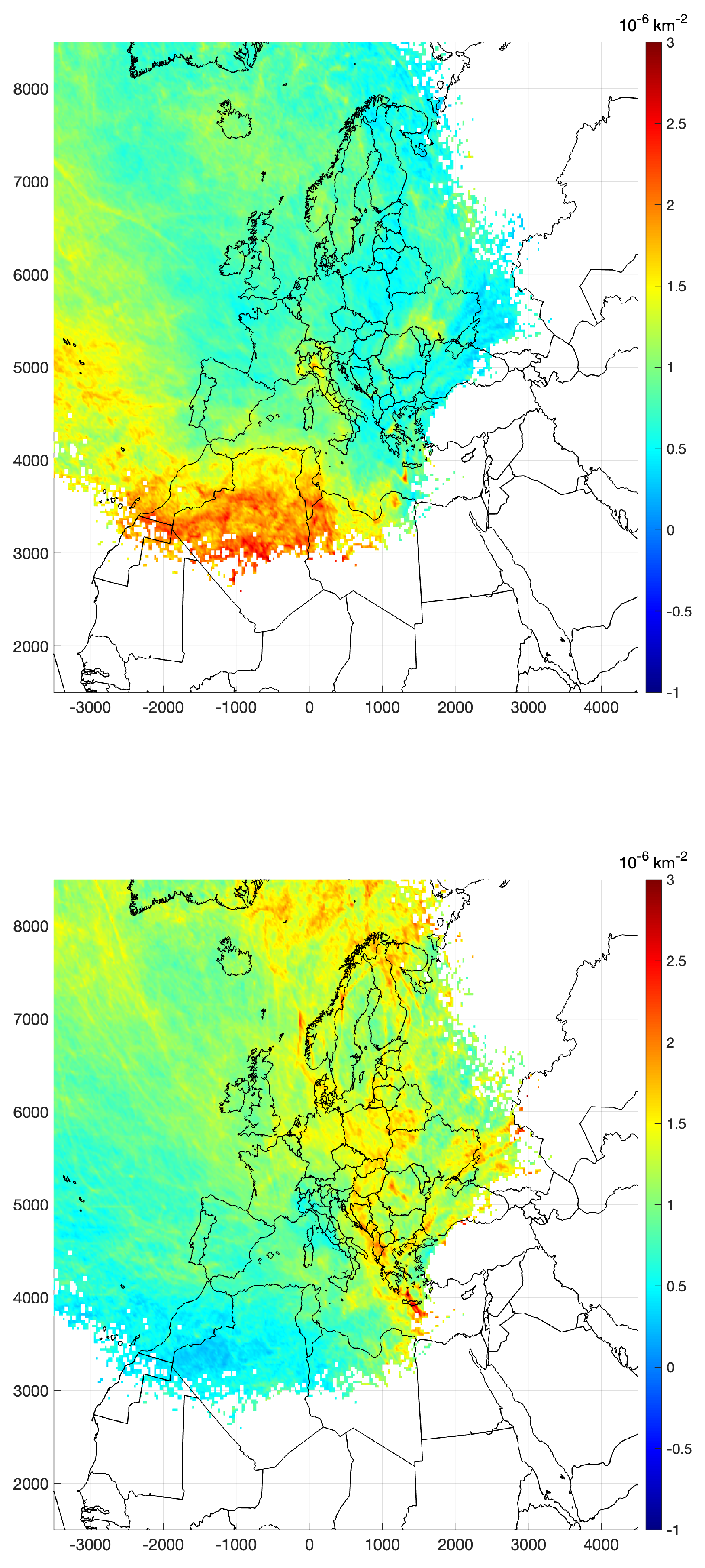

Finally,

Figure 8 provides the ratio of residence times during high and low pollution events. In particular, the ratio of the conditional probability (refer to equation

1) was computed for events during which the concentrations at the PdA site exceeded the 80th percentile or fell below the 20th percentile. Two prominent features are available from this figure: during high pollution events, the regions contributing to emissions are located in the southeastern part of the domain, mainly from the Saharan region; nearby Italian regions, especially from Northern Italy and from the Tirrenian coast, also contribute to high pollution loads. Given that the residence time analysis pertains solely to the duration the entire trajectory resides on, the source-receptor analysis attributes a high conditional probability to segments traversing the Atlantic coasts. The maximum of the conditional probability east of the Canary Islands and the Morocco coastline is associated with trajectories passing first over the Atlantic Ocean and then northeastward over North Africa, where dust is actually mobilized, toward the Mediterranean basin, in agreement with [

33]. Consequently, the observed maximum can be perceived as a potential artifact, attributing artificial emission sources to regions where several back-trajectories associated with high concentration events have traversed prior to reaching the actual source region.

During episodes of low pollution, atmospheric circulation is characterized by air mass trajectories originating from the northern European or northwestern Atlantic regions. As depicted in

Figure 8, these trajectories from the Northern sector are typically associated with low PM mass loading, which is likely due to their correlation with low emission levels and elevated wind velocities.

4. Discussion

This study advances the understanding of particulate matter (PM

10) transport dynamics in the Mediterranean region by integrating backward trajectory analysis, cluster analysis, and residence time analysis to investigate air mass pathways and their contributions to PM concentrations at the Pomigliano d’Arco (PdA) site, offering insights into the interplay of local emissions, regional transport mechanisms, and meteorological conditions. While earlier research has predominantly examined remote or rural locations in the Mediterranean basin [

3,

15], this work highlights the compounded effects of local emissions and regional transport in a densely populated and industrialized region.

The analysis of PM concentrations during the period 2018-2023 clearly shows the high PM loads at this receptor. The distinctive characteristics of this site are evident in the distribution of daily data, which predominantly shows values concentrated in the range of 20–40

g/m

3, and a slow and gradual decline in the frequency at higher concentration levels, accompanied by occurrences of extreme values exceeding 90

g/m

3. When compared to other urban and industrialized regions, PM

10 levels at PdA are notably high. For instance, annual averages at PdA exceed those reported for similarly industrialized areas such as Milan and Turin in Northern Italy, where averages range between 30 and 40

g/m

3 [

34]. In Mediterranean urban centers such as Barcelona and Athens, PM

10 levels are typically lower, averaging around 25–35

g/m

3, reflecting differences in local emission sources and regional meteorological influences [

35]. These findings highlight the unique challenges posed by the combination of local emissions, complex topographical features, and transboundary pollutant transport at the PdA site in Southern Italy.

Variations in daily values throughout the year are indicative of seasonal fluctuations in emission sources and synoptic/local meteorological conditions (e.g., [

34]). The monthly variations in PM

10 concentrations exhibit a pronounced increase during the colder months. This phenomenon at the PdA station can be ascribed to a heightened dependence on residential heating, coupled with reduced atmospheric dispersion due to temperature inversions, which confine pollutants near the surface level [

36,

37]. Furthermore, the increase in concentrations observed during the summer can likely be attributed to enhanced photochemical activity and the formation of secondary aerosols driven by elevated temperatures and sunlight, thereby exacerbating urban pollution [

29].

The identification of seven distinct airflow patterns exemplifies the interplay of synoptic-scale meteorological conditions influencing the region. These patterns are governed by synoptic phenomena, notably including the extended subtropical anticyclone of the Atlantic (Azores) and the North Atlantic Oscillation [

15,

38,

39,

40]. Predominantly, local circulations prevail throughout the year, primarily originating from the northeastern and western directions. Although less frequent, southerly circulations denote the impact of cyclonic activity within the Mediterranean and the advection of air masses from North Africa [

41]. More specifically, during spring, large amounts of mineral particles are transported, mainly from the Sahara desert towards the Mediterranean and Europe [

14]. The transport is facilitated by the prevailing south-southwesterly winds induced by depressions advancing eastwards along the North African coast. In the summer months, the transport of Saharan dust within the western and central Mediterranean basin occurs because of thermal lows situated either over northwestern Africa or the Iberian Peninsula [

14,

42]. In contrast, the highest frequencies of the fast northerly and westerly patterns occur in winter, associated with stronger pressure gradients and enhanced zonal flow typical of the winter season, leading to rapid transport of air masses from distant regions [

43].

The interaction between local topographical features and the proximity to the Mediterranean sea leads to the formation of nearby circulation patterns, influenced by thermal contrasts, thereby increasing the complexity of airflow in this region. Elevated PM

10 concentrations are observed under these regional circulation patterns, particularly from the NE-n and NW-n directions. These results align with prior research indicating that regional circulation patterns exert a considerable influence on air quality in urban areas across the Mediterranean [

44]. This influence is further corroborated by the frequency analysis of exceedance days where PM

10 concentrations exceeed the EU’s daily limit of 50

g/m

3. Specifically, these nearby circulation patterns are responsible for 75% of the days with elevated pollution levels, highlighting the role of slow-moving air masses originating near Naples in facilitating pollutant accumulation [

45].

The temporal and spatial distribution of residence times play a pivotal role in shaping the transport of pollutants and their potential accumulation in the region. The highest residence times are observed in proximity to the central Mediterranean area, indicating dominant local circulations. This finding highlights the importance of local sources in contributing to the regional air quality. Furthermore, elevated residence times are present along pathways extending to Northern Africa and Southeastern Europe, suggesting that long-range transport mechanisms also play a significant role during specific periods. The influence of the Sahara, particularly during dust episodes, aligns with prior studies demonstrating its impact on particulate matter concentrations in the Mediterranean basin [

35,

46].

Seasonal differences in the backward trajectories emphasize the interplay between meteorological conditions and pollutant transport. During the summer months, air masses originating from Northern Africa were more prevalent, consistent with the enhanced desert dust transport typical of this season. In contrast, the winter period exhibited a higher frequency of trajectories from Europe, reflecting the influence of continental sources and synoptic-scale weather patterns. These results corroborate findings from similar studies conducted in the Mediterranean region [

16,

17]. The analysis also revealed that residence times are inversely related to the transport speed of air masses. Regions with higher residence times correspond to slower-moving air masses, allowing for greater accumulation of pollutants. This observation underscores the role of stagnant atmospheric conditions in exacerbating air quality issues. Areas with shorter residence times, typically associated with faster-moving air masses, exhibited lower pollutant concentrations, indicating efficient dispersion and dilution mechanisms. In terms of air quality, the residence time patterns imply that emissions from anthropogenic or natural sources within the highlighted high-RT regions are likely to have a significant impact on pollutant levels at the receptor site.

5. Conclusion

This backward trajectory analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of the atmospheric transport processes affecting the PdA site in a central Mediterranean region. Local circulations and long-range transport from Northern Africa and Europe are the primary contributors to the observed air quality patterns. Seasonal variations in trajectory origins reflect the dynamic nature of atmospheric circulation and its implications for pollutant transport.

The implications of this study are significant for air quality management in the Mediterranean region. The identification of the central Mediterranean and Northern Africa as key contributors to high PM

10 levels underscores the need for transboundary policies that address both local emissions and regional transport. Furthermore, the findings emphasize the importance of targeted interventions during periods of stagnation, such as reducing emissions from industrial and residential heating sources in winter. These results complement the observations of Putaud et al. [

34], who highlighted the need for localized emission control measures, by providing specific evidence from an urban-industrial context, i.e. by emphasizing both local and transboundary actions to mitigate particulate matter pollution. In the case of the PdA site, long-term strategies should integrate urban planning and sustainable development practices to mitigate PM

10 pollution, balancing approaches that combine regulatory enforcement, technological innovation, public awareness, and transboundary collaboration. Such strategies not only address the immediate challenge of PM

10 pollution but also contribute to the broader goals of environmental sustainability and public health protection.

Finally, this study opens new avenues for future research. The integration of residence time analysis with chemical transport models, such as WRF-Chem or CAMx, could enhance source apportionment by quantifying the relative contributions of natural and anthropogenic sources. Additionally, the potential impacts of climate change on atmospheric circulation patterns and pollutant transport warrant further investigation, as shifting synoptic conditions may alter the dynamics of PM10 accumulation in the Mediterranean basin.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R., Marco T.; methodology, A.R., Marco T.; validation, A.R. and E.C.; formal analysis, A.R.; investigation, A.G., M.A., Maria T.; resources, A.R., M.A. and Marco T.; data curation, A.R., E.C., A.G. and Maria T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G., A.R., E.C., M.A., Maria T. and Marco T.; writing—review and editing, A.R.; funding acquisition, Marco T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Municipality of Pomigliano d’Arco, under the MONAIR project.

Data Availability Statement

Data and software analysis may be available from authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Municipality of Pomigliano D’Arco (NA) for supporting the MONAIR project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. The Probability Density Function associated with Residence Time

The two-dimensional residence time (RT) depends on how frequently air mass trajectories pass over a grid cell and the time they remain within it. As outlined in [

24] and [

27], in the case of straight trajectories moving at constant speed,

u, and duration,

, the probability density function for RT in polar coordinates, (

), assumes the following form

where

indicates the density of trajectories from direction

. The expression takes the form

where

denotes the mean density of trajectories spanning from 0 to

, and

represents the density per unit radiant.

is the maximum distance traveled, on the assumption of a rectilinear trajectory and constant speed.

f can be conceptualized as comprising two distinct components: the transport directional frequency and the accumulation potential. The transport directional frequency quantifies the likelihood of air mass transport occurring between a source and receptor per unit arc length, equivalent to

which decreases with distance due to the spread of trajectories over a larger area. The accumulation potential quantifies the time air parcels spend over a specific region, inversely related to transport speed:

This measure encapsulates the extent to which emissions originating from a specific region contribute to the accumulation of pollutants in air parcels. Indeed, as the velocity of an air parcel’s movement over a region decreases, the duration during which emissions from that region accumulate within the air parcel increases. Given these two definitions,

f can be expressed as

In its discrete form,

is averaged over the arc length of each grid cell, and the resulting value quantifies the frequency of trajectory crossings relative to the grid cell area.

where

has unit of [m

−1]; index

i runs over all trajectories, whose number is

T;

is unit if trajectory

t traverses grid cell

, 0 otherwise;

L is a length scale where

is the area of the grid cell. Similarly, the discrete accumulation potential is derived as the mean time trajectories reside within a cell, normalized by the grid cell’s radial length:

where

where

is the discrete accumulation potential for grid cell

;

is the number of trajectory segment endpoints in grid cell

for trajectory

t;

is the average number of trajectory segment endpoints per trajectory in the grid cell

, and

is the time interval between each trajectory segment endpoint.

These parameters are combined to estimate the

pdf for residence time at grid cell

as:

References

- Stein, A.F.; Draxler, R.R.; Rolph, G.D.; Stunder, B.J.; Cohen, M.D.; Ngan, F. NOAA’s HYSPLIT atmospheric transport and dispersion modeling system. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2015, 96, 2059–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakels, L.; Tatsii, D.; Tipka, A.; Thompson, R.; Dütsch, M.; Blaschek, M.; Seibert, P.; Baier, K.; Bucci, S.; Cassiani, M.; et al. FLEXPART version 11: Improved accuracy, efficiency, and flexibility. Geoscientific Model Development 2024, 17, 7595–7627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, J.D.; Martinez, D.A.; Kuhns, H.; Davidson, C.I.; Jaffrezo, J.L.; Harris, J.M. Air mass trajectories to Summit, Greenland: A 44-year climatology and some episodic events. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 1997, 102, 26861–26875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tositti, L.; Riccio, A.; Sandrini, S.; Brattich, E.; Baldacci, D.; Parmeggiani, S.; Cristofanelli, P.; Bonasoni, P. Short-term climatology of PM10 at a high altitude background station in southern Europe. Atmospheric Environment 2013, 65, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Wu, C. Investigation of source locations and contributions using an integrated trajectory-source apportionment method with multiple time resolution data. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2017, 14, 1781–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.K.; Holsen, T.M.; Hopke, P.K. Comparison of hybrid receptor models to locate PCB sources in Chicago. Atmospheric environment 2003, 37, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, S.; Schaub, D.; Stemmler, K.; Folini, D.; Hill, M.; Hofer, P.; Buchmann, B.; Simmonds, P.G.; Greally, B.R.; O’Doherty, S. Halogenated greenhouse gases at the Swiss High Alpine Site of Jungfraujoch (3580 m asl): Continuous measurements and their use for regional European source allocation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2004, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lyu, B.; Bai, Y. Aerosol vertical profile variations with seasons, air mass movements and local PM2.5 levels in three large China cities. Atmospheric Environment 2020, 224, 117329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merico, E.; Cesari, D.; Gregoris, E.; Gambaro, A.; Cordella, M.; Contini, D. Shipping and air quality in Italian port cities: state-of-the-art analysis of available results of estimated impacts. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chianese, E.; Tirimberio, G.; Appolloni, L.; Dinoi, A.; Contini, D.; Di Gilio, A.; Palmisani, J.; Cotugno, P.; Miniero, D.V.; Dusek, U.; et al. Chemical characterisation of PM10 from ship emissions: A study on samples from hydrofoil exhaust stacks. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrodangelo, A.; Bove, M.C.; Forello, A.C.; Crova, F.; Bigi, A.; Brattich, E.; Riccio, A.; Becagli, S.; Bertinetti, S.; Calzolai, G.; et al. A PM10 chemically characterized nation-wide dataset for Italy. Geographical influence on urban air pollution and source apportionment. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 908, 167891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Europe’s air quality status 2024. Technical report, European Environment Agency, 2024.

- WHO. Air quality, energy, and health. Technical report, World Health Organization, 2021.

- Barnaba, F.; Gobbi, G. Aerosol seasonal variability over the Mediterranean region and relative impact of maritime, continental and Saharan dust particles over the basin from MODIS data in the year 2001. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2004, 4, 2367–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkikas, A.; Houssos, E.; Hatzianastassiou, N.; Papadimas, C.; Bartzokas, A. Synoptic conditions favouring the occurrence of aerosol episodes over the broader Mediterranean basin. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2012, 138, 932–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querol, X.; Tobías, A.; Pérez, N.; Karanasiou, A.; Amato, F.; Stafoggia, M.; García-Pando, C.P.; Ginoux, P.; Forastiere, F.; Gumy, S.; et al. Monitoring the impact of desert dust outbreaks for air quality for health studies. Environment international 2019, 130, 104867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrıguez, S.; Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Kallos, G.; Kakaliagou, O. Saharan dust contributions to PM10 and TSP levels in Southern and Eastern Spain. Atmospheric Environment 2001, 35, 2433–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrino, C.; Giusto, M.; Sargolini, T.; Calzolai, G.; Canepari, S. Assessment of the link between atmospheric dispersion and chemical composition of PM10 at 2-h time resolution. Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draxler, R. HYSPLIT4 user’s guide NOAA Tech. Technical report, NOAA Air Resources Laboratory, Silver Spring, MD, 1999. Memo. ERL ARL-230.

- Draxler, R.; Stunder, B.; Rolph, G.; Stein, A.; Taylor, A. HYSPLIT tutorial, 2012.

- Cape, J.; Methven, J.; Hudson, L. The use of trajectory cluster analysis to interpret trace gas measurements at Mace Head, Ireland. Atmospheric Environment 2000, 34, 3651–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, A.; Giunta, G.; Chianese, E. The application of a trajectory classification procedure to interpret air pollution measurements in the urban area of Naples (Southern Italy). Science of the Total Environment 2007, 376, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccio, A.; Chianese, E.; Agrillo, G.; Esposito, C.; Ferrara, L.; Tirimberio, G. Source apportion of atmospheric particulate matter: a joint Eulerian/Lagrangian approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2014, 21, 13160–13168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbaugh, L.L.; Malm, W.C.; Sadeh, W.Z. A residence time probability analysis of sulfur concentrations at Grand Canyon National Park. Atmospheric Environment 1985, 19, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirot, R.L.; Wishinski, P.R. Visibility, sulfate and air mass history associated with the summertime aerosol in northern Vermont. Atmospheric Environment (1967) 1986, 20, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohl, A. Computation, accuracy and applications of trajectories—A review and bibliography. Atmospheric Environment 1998, 32, 947–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schichtel, B.A.; Gebhart, K.A.; Barna, M.G.; Malm, W.C. Association of airmass transport patterns and particulate sulfur concentrations at Big Bend National Park, Texas. Atmospheric Environment 2006, 40, 992–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of European Union. Directive 2024/2881 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2024 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe, 2024.

- Zhang, R.; Wang, G.; Guo, S.; Zamora, M.L.; Ying, Q.; Lin, Y.; Wang, W.; Hu, M.; Wang, Y. Formation of urban fine particulate matter. Chemical reviews 2015, 115, 3803–3855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rüdisühli, S.; Sprenger, M.; Leutwyler, D.; Schär, C.; Wernli, H. Attribution of precipitation to cyclones and fronts over Europe in a kilometer-scale regional climate simulation. Weather and Climate Dynamics 2020, 1, 675–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R.J.; Efron, B. An introduction to the bootstrap; Vol. 57, Monographs on statistics and applied probability, Chapman and Hall, Inc., 1993; pp. 1–436.

- Prospero, J.M.; Ginoux, P.; Torres, O.; Nicholson, S.E.; Gill, T.E. Environmental characterization of global sources of atmospheric soil dust identified with the Nimbus 7 Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) absorbing aerosol product. Reviews of geophysics 2002, 40, 2–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelevich, P.; Ganor, E.; Alpert, P.; Kishcha, P.; Stupp, A. Predominant transport paths of Saharan dust over the Mediterranean Sea to Europe. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putaud, J.P.; Van Dingenen, R.; Alastuey, A.; Bauer, H.; Birmili, W.; Cyrys, J.; Flentje, H.; Fuzzi, S.; Gehrig, R.; Hansson, H.C.; et al. A European aerosol phenomenology–3: Physical and chemical characteristics of particulate matter from 60 rural, urban, and kerbside sites across Europe. Atmospheric Environment 2010, 44, 1308–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querol, X.; Pey, J.; Pandolfi, M.; Alastuey, A.; Cusack, M.; Pérez, N.; Moreno, T.; Viana, M.; Mihalopoulos, N.; Kallos, G.; et al. African dust contributions to mean ambient PM10 mass-levels across the Mediterranean Basin. Atmospheric Environment 2009, 43, 4266–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janhäll, S.; Olofson, K.F.G.; Andersson, P.U.; Pettersson, J.B.; Hallquist, M. Evolution of the urban aerosol during winter temperature inversion episodes. Atmospheric Environment 2006, 40, 5355–5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, J.; Ding, A.; Liao, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, T.; Xue, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, B. Aerosol and boundary-layer interactions and impact on air quality. National Science Review 2017, 4, 810–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xoplaki, E.; González-Rouco, J.F.; Luterbacher, J.; Wanner, H. Mediterranean summer air temperature variability and its connection to the large-scale atmospheric circulation and SSTs. Climate dynamics 2003, 20, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xoplaki, E.; González-Rouco, J.; Luterbacher, J.; Wanner, H. Wet season Mediterranean precipitation variability: influence of large-scale dynamics and trends. Climate dynamics 2004, 23, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krichak, S.; Alpert, P. Signatures of the NAO in the atmospheric circulation during wet winter months over the Mediterranean region. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2005, 82, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, S.; Karacostas, T.; Sánchez, J.L.; Retalis, A.; Pytharoulis, I.; Homar, V.; Romero, R.; Zanis, P.; Giannakopoulos, C.; Bühl, J.; et al. Reviews and perspectives of high impact atmospheric processes in the Mediterranean. Atmospheric Research 2018, 208, 4–44. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimas, C.; Hatzianastassiou, N.; Mihalopoulos, N.; Querol, X.; Vardavas, I. Spatial and temporal variability in aerosol properties over the Mediterranean basin based on 6-year (2000–2006) MODIS data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2008, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, I.F.; Bigg, G.R.; Davies, T.D. Climatology of cyclogenesis mechanisms in the Mediterranean. Monthly Weather Review 2002, 130, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Moreno, T.; Viana, M.; Castillo, S.; Pey, J.; Rodríguez, S.; Artiñano, B.; Salvador, P.; Sánchez, M.; et al. Spatial and temporal variations in airborne particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5) across Spain 1999–2005. Atmospheric Environment 2008, 42, 3964–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallos, G.; Kotroni, V.; Lagouvardos, K.; Papadopoulos, A. On the long-range transport of air pollutants from Europe to Africa. Geophysical Research Letters 1998, 25, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkikas, A.; Hatzianastassiou, N.; Mihalopoulos, N.; Katsoulis, V.; Kazadzis, S.; Pey, J.; Querol, X.; Torres, O. The regime of intense desert dust episodes in the Mediterranean based on contemporary satellite observations and ground measurements. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2013, 13, 12135–12154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).