Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Legislative Framework

1.2. Need for Complementary Air Quality Indicators

1.3. Research Objectives and Contributions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Air Quality Data

2.3. Definition and Calculation of the Proposed Indicators

2.2.1. Excess Concentration (EC)

2.2.2. Episode Index (EI)

2.2.3. Toxic Load Index (TLI)

3. Results

3.1. Measured Annual Mean Concentrations Compared with Current and Future Limit Value

3.1.1. Annual Mean Concentrations of PM10

3.1.2. Annual Mean Concentrations of PM2.5

3.2. Daily Exceedances Relative to Current and Future Daily Limit Values for PM10 and PM2.5

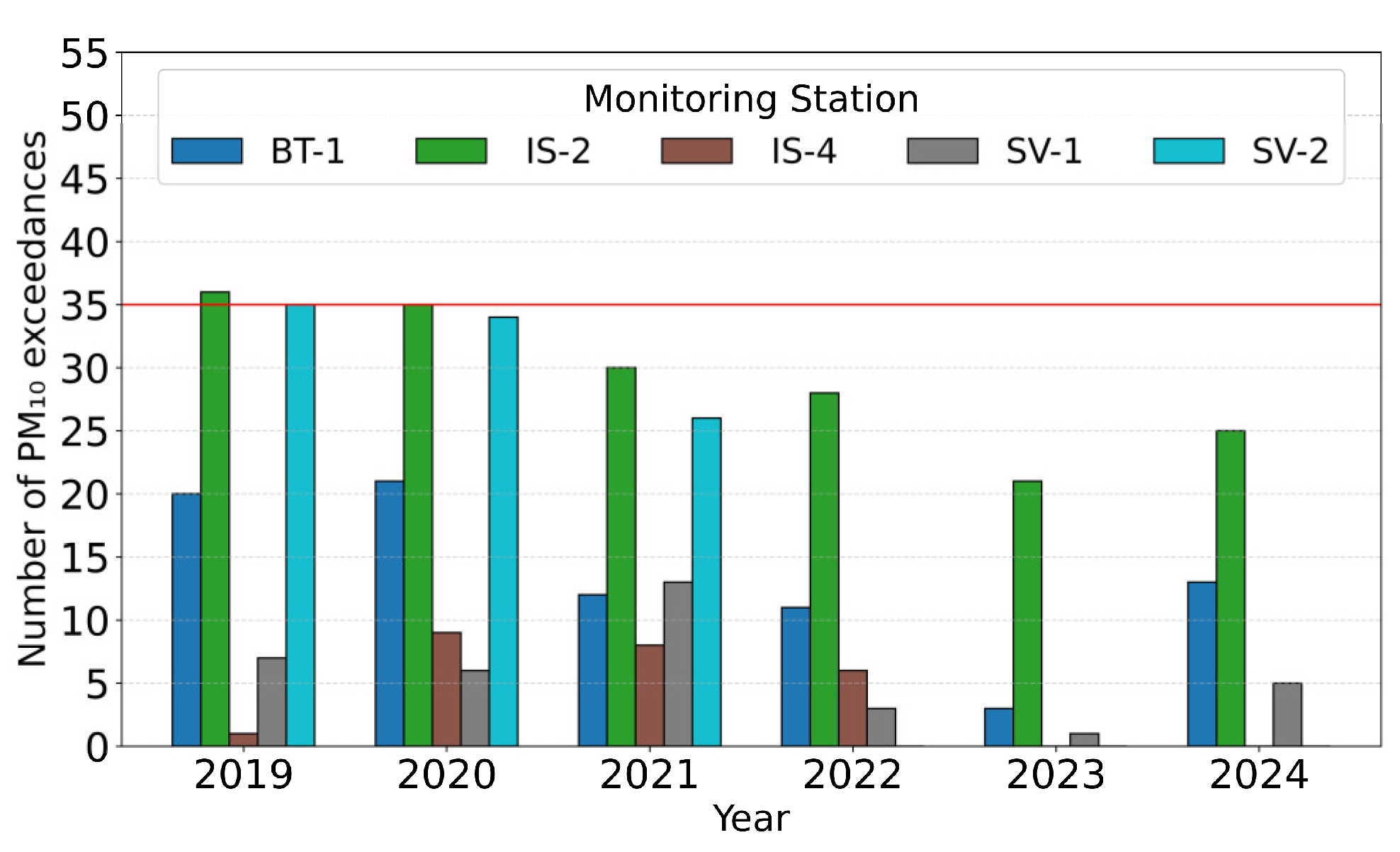

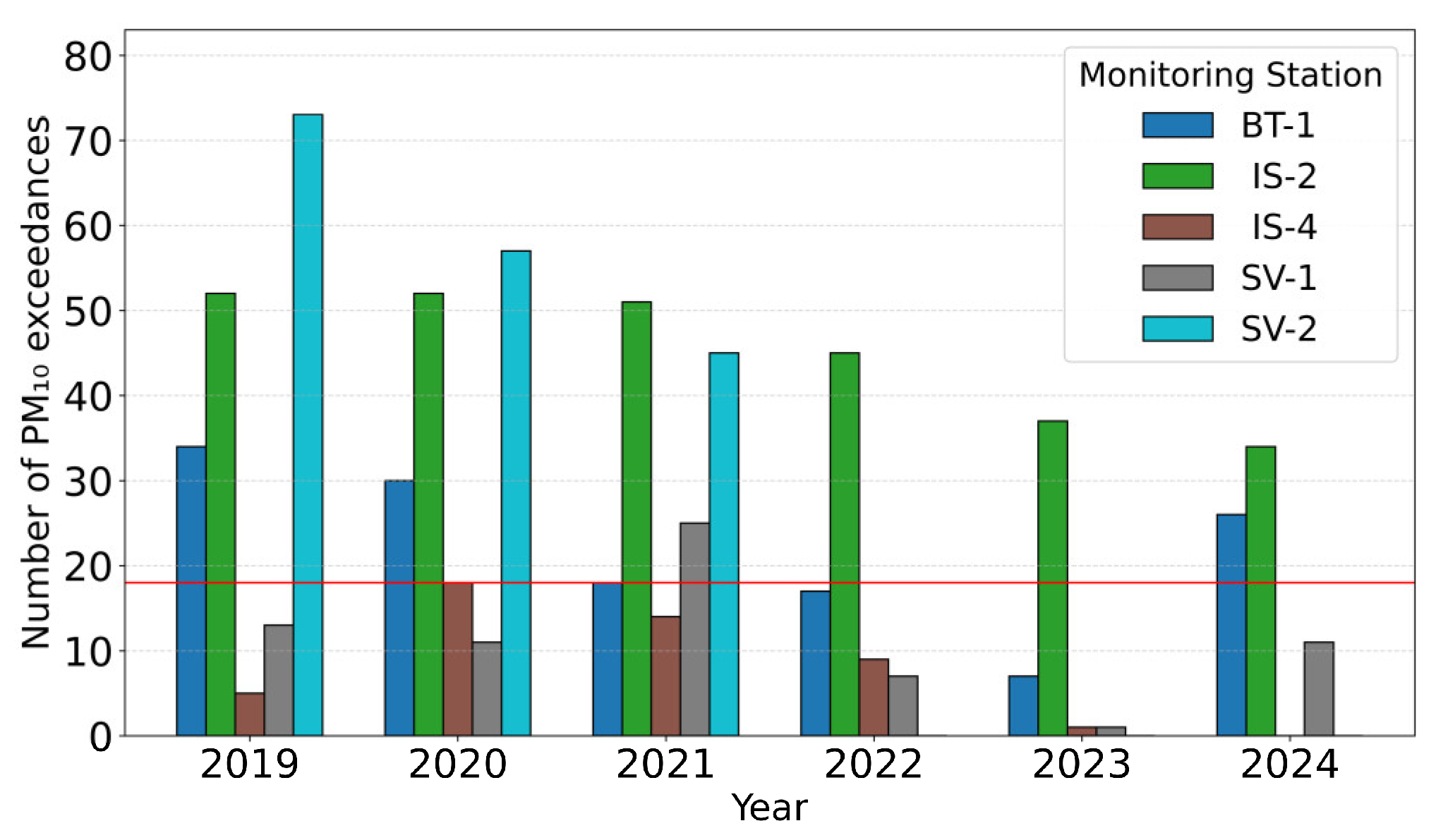

3.2.1. Analysis of Daily Exceedances for PM10

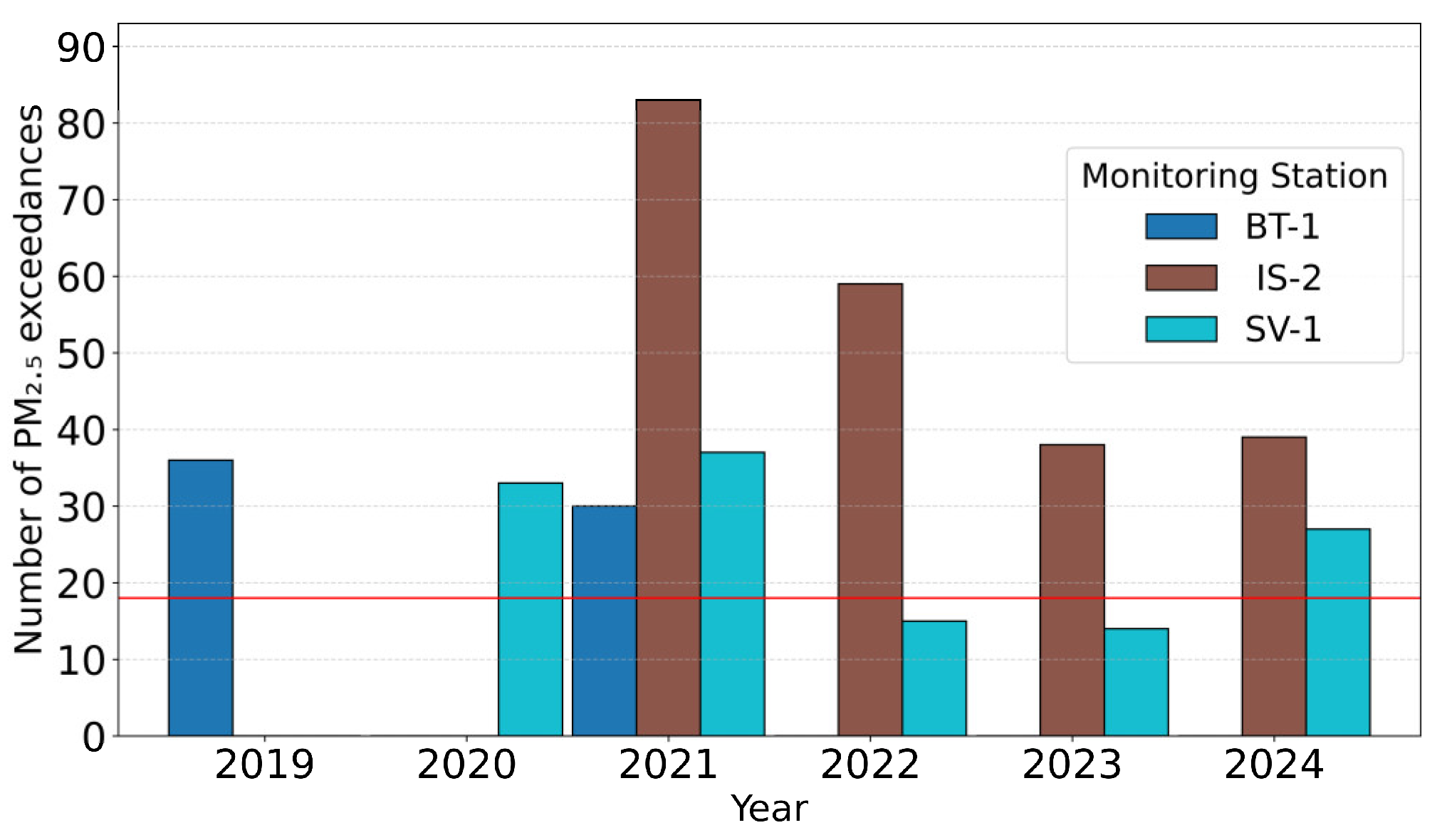

3.2.2. Analysis of Daily Exceedances for PM2.5

3.3. Proposed Supplementary Indicators for PM10 and PM2.5

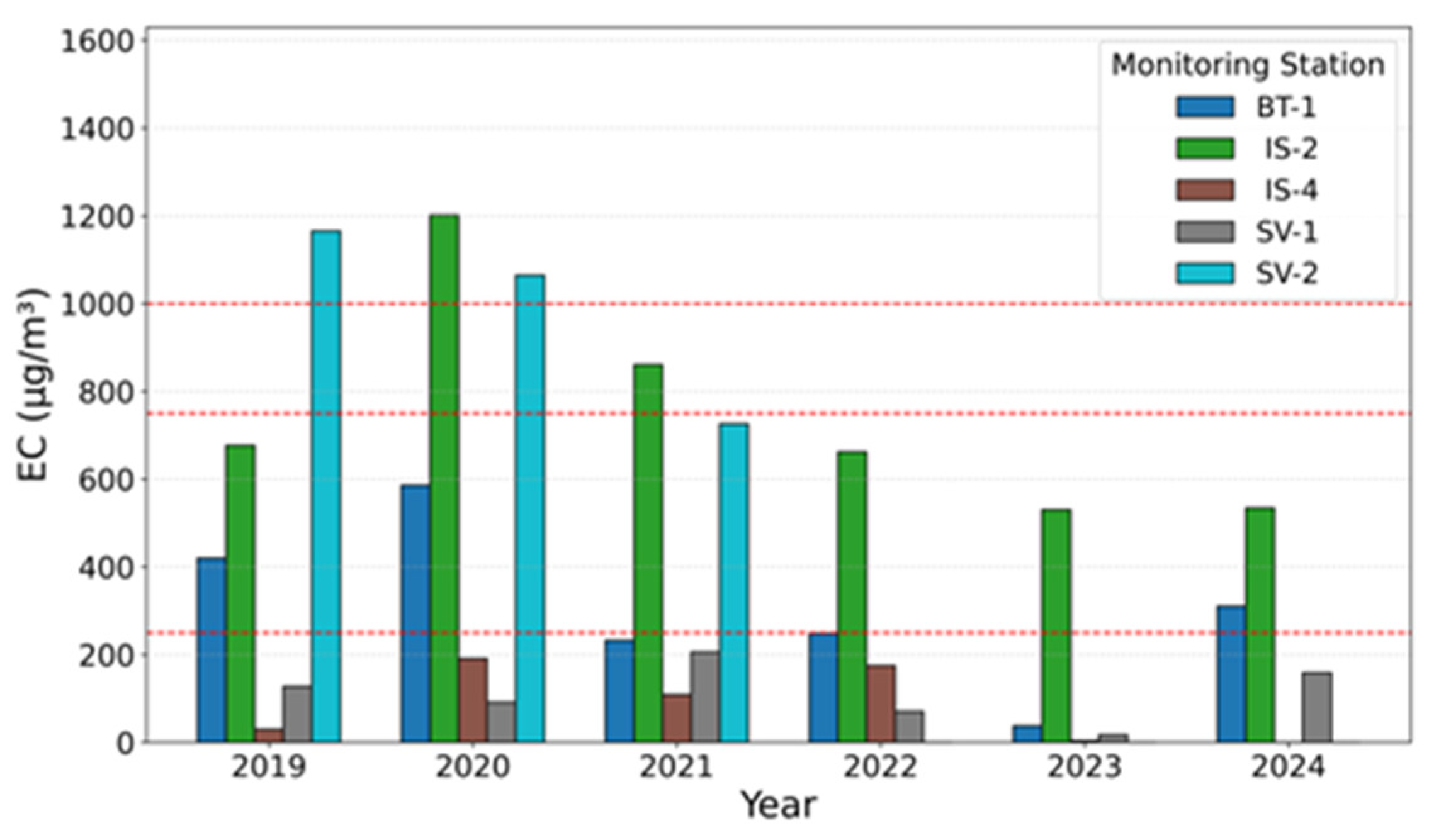

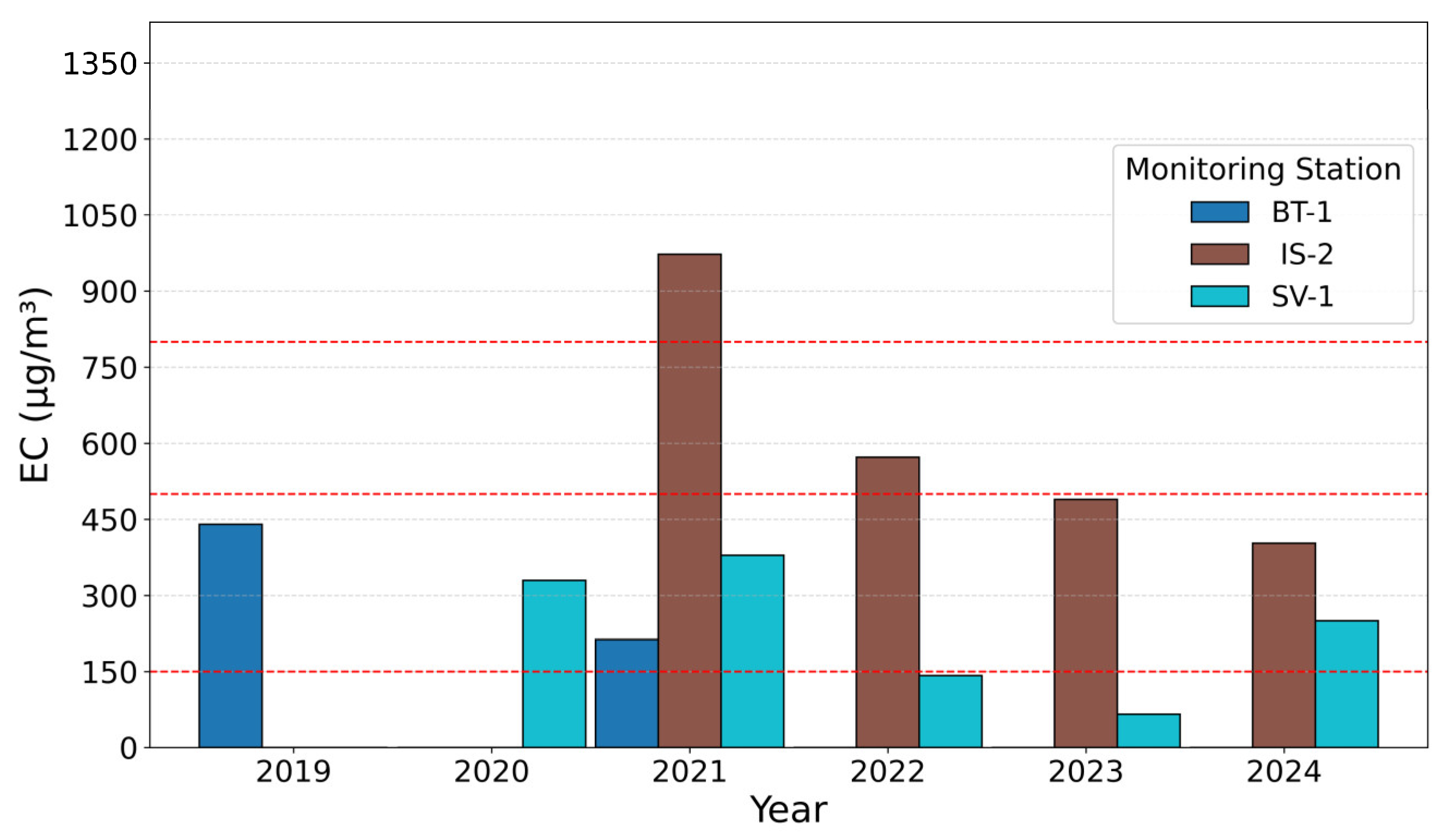

3.3.1. Excess Concentration

3.3.2. Episode Index (EI)

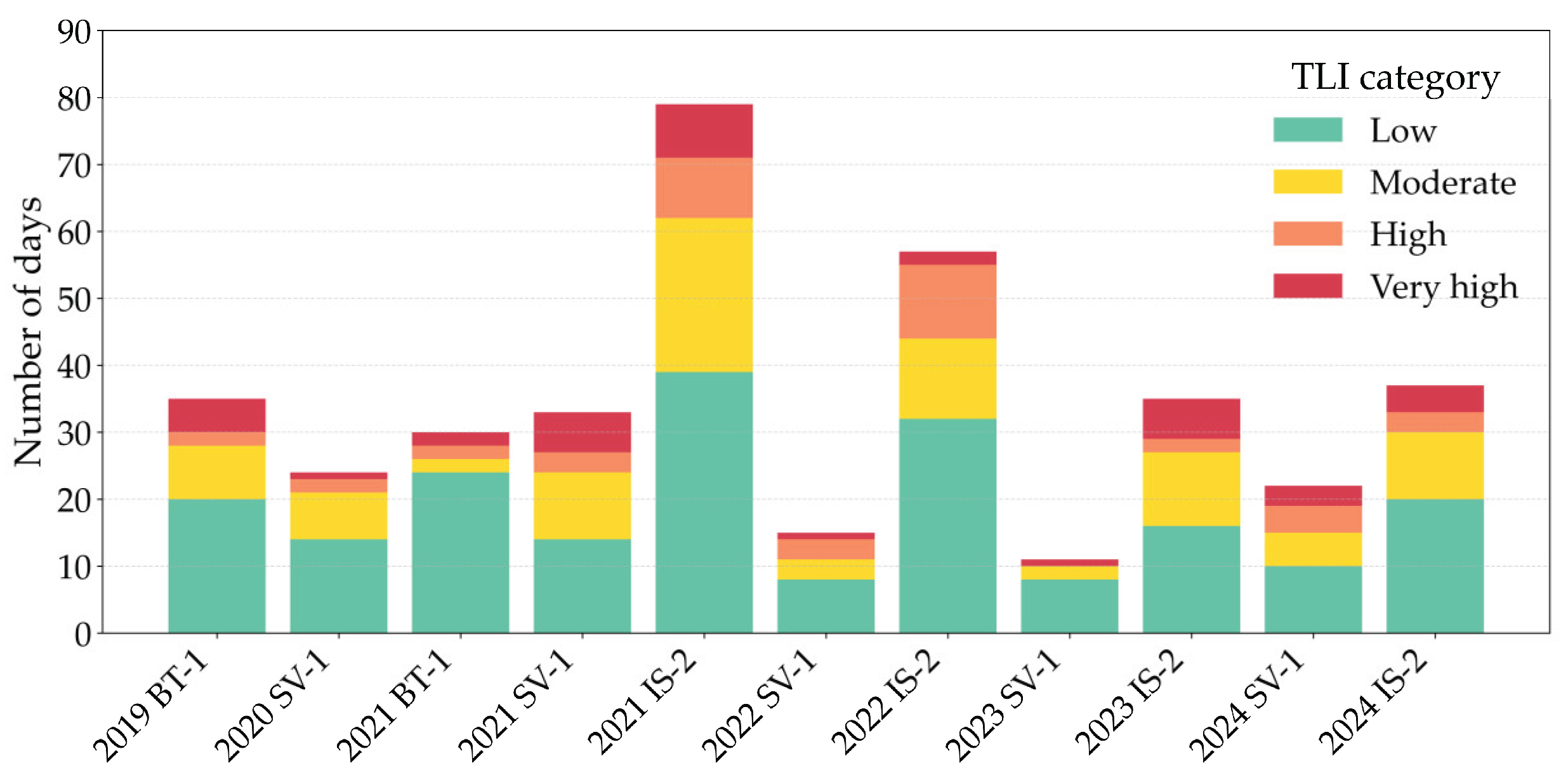

3.3.3. Toxic Load Index (TLI)

4. Discussion

4.1. Compliance with Future Standards

4.2. Analysis and Relevance of the Proposed Additional Indicators

4.2. Relevance to Public Policy Development

4.3. Recommendations for Reducing Particulate Matter

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AQG | Air Quality Guidelines |

| EC | Excess Concentration |

| EI | Episode Index |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| TLI | Toxic Load Index |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| LEZ | Low emission zone |

References

- István, P. The European Environment-State and Outlook 2020. Knowledge for Transition to a Sustainable Europe; 2020; Vol. 60. [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO global air quality guidelines. Coastal And Estuarine Processes 2021, 1–360. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate-General for Environment. 2025 Environmental Implementation Review Country Report – ROMANIA.

- Philip, S.; Martin, R.V.; Snider, G.; Weagle, C.L.; Van Donkelaar, A.; Brauer, M.; et al. Anthropogenic fugitive, combustion and industrial dust is a significant, underrepresented fine particulate matter source in global atmospheric models. Environmental Research Letters 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Heuvel, R.; Staelens, J.; Koppen, G.; Schoeters, G. Toxicity of urban PM10 and relation with tracers of biomass burning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oficial, J. 2024/2881. 2024, 2881, 1–70.

- Directiva 2008/50/CE. Directiva 2008/50/CE a parlamentului European si a Consiliului din 21 mai 2008 privind calitatea aerului înconjurător si un aer mai curat pentru Europa. Jurnalul Oficial al Uniunii Europene.

- Pražnikar, Z.J.; Pražnikar, J. The effects of particulate matter air pollution on respiratory health and on the cardiovascular system. Zdravstveno Varstvo 2012, 51, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, H.W. Impact of long-term exposure to ambient air pollution on the incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Research 2021, 194, 110703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taj, T.; Poulsen, A.H.; Ketzel, M.; Geels, C.; Brandt, J.; Christensen, J.H.; et al. Exposure to PM2.5 constituents and risk of adult leukemia in Denmark: A population-based case–control study. Environmental Research 2021, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres. Aires2011_Review of the UK Air Quality Index COMEAP.

- Withey, J.R. A critical review of the health effects of atmospheric particulates. Toxicology and Industrial Health 1989, 5, 519–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunekreef, B.; Forsberg, B. Epidemiological evidence of effects of coarse airborne particles on health. European Respiratory Journal 2005, 26, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, D.E.; Euler, G.L.; Moore, J.K.; Petersen, F.; Hodgkin, J.E.; Magie, A.R. Applications of a method for setting air quality standards based on epidemiological data. Journal of the Air Pollution Control Association 1989, 39, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pini, L.; Giordani, J.; Gardini, G.; Concoreggi, C.; Pini, A.; Perger, E.; et al. Emergency department admission and hospitalization for COPD exacerbation and particulate matter short-term exposure in Brescia, a highly polluted town in northern Italy. Respiratory Medicine 2021, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Joo, H.S.; Lee, K.; Jang, M.; Kim, S.D.; Kim, I.; et al. Differential toxicities of fine particulate matters from various sources. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Zanobetti, A.; Koutrakis, P.; Schwartz, J.D. Associations of fine particulate matter species with mortality in the united states: A multicity time-series analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives 2014, 122, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DRAGOI (ONIU), L.; BREABĂN, I.G.; CAZACU, M.-M. 2017–2020 trends of particulate matter PM10 concentrations in the cities of Suceava and Botoșani. Present Environment and Sustainable Development 2023, 17, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăgoi (Oniu), L.; Cazacu, M.-M.; Breabăn, I.-G. Analysis of the PM2.5/PM10 Ratio in Three Urban Areas of Northeastern Romania. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suceava, P. mun. PCA Municipiul Suceava 2023_2027.Pdf.

- Primaria municipiului Iasi. Plan Integrat De Calitate a Aerului Pentru Municipiul Iasi Pentru Indicatorii Dioxid De Azot Și Oxizi De Azot (NO2/NOX) Și Particule in Suspensie.

- Lu, F.; Xu, D.; Cheng, Y.; Dong, S.; Guo, C.; Jiang, X.; et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the adverse health effects of ambient PM2.5 and PM10 pollution in the Chinese population. Environmental Research 2015, 136, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, X. Ratio of PM 2. 5 to PM 10 Mass Concentrations in Beijing and Relationships with Pollution from the North China Plain. 2020, No. Xia 2014.

- Cariolet, J.M.; Colombert, M.; Vuillet, M.; Diab, Y. Assessing the resilience of urban areas to traffic-related air pollution: Application in Greater Paris. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 615, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazacu, M.M. , Şchiopu, C.E., Rădulescu, C.M., Falotă, D., Bodnariu, A.I., Politică publică alternativă pentru măsurarea, îmbunătățirea şi păstrarea calităţii aerului ambiental: Propunere de politică publică dezvoltată în cadrul proiectului „Politici publice alternative în domeniul calității aerului”, ISBN: 978-606-48-1175-2, StudIS, Iasi, Romania, 2024.

- Wu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Gbaguidi, A.; Tang, X.; Zhou, W. Numerical study of the effect of traffic restriction on air quality in beijing. Scientific Online Letters on the Atmosphere 2010, 6 A, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yu, Y. Effect of short-term regional traffic restriction on urban submicron particulate pollution. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China) 2017, 55, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Progiou, A.; Liora, N.; Sebos, I.; Chatzimichail, C.; Melas, D. Measures and Policies for Reducing PM Exceedances through the Use of Air Quality Modeling: The Case of Thessaloniki, Greece. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, H.; Perry, L. Trends in clean air legislation in Europe: Particulate matter and low emission zones. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 2010, 4, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fensterer, V.; Küchenhoff, H.; Maier, V.; Wichmann, H.E.; Breitner, S.; Peters, A.; et al. Evaluation of the impact of low emission zone and heavy traffic ban in Munich (Germany) on the reduction of PM10 in ambient air. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2014, 11, 5094–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrys, J.; Peters, A.; Soentgen, J.; Wichmann, H.E. Low emission zones reduce PM10 mass concentrations and diesel soot in German cities. Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association 2014, 64, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Pollutant |

Averaging period |

Directive 2008/50/EC* | Directive (EU) 2024/2881** |

WHO, 2021 Recommended |

| Limit value | AQG level | |||

|

PM2.5 µg/m3 |

Calendar year | 25 | 10 | 5 |

| 1 day | - | 25 not to be exceeded more than 18 times per calendar year |

15 not to be exceeded more than 3-4 times per calendar year |

|

|

PM10 µg/m3 |

Calendar year | 40 | 20 | 15 |

| 1 day | 50 not to be exceeded more than 35 times per calendar year |

45 not to be exceeded more than 18 times per calendar year |

45 not to be exceeded more than 3-4 times per calendar year |

|

| Pollutant | Averaging period | Directive (EU) 2024/2881 |

| PM2.5 | 1 day | 50 µg/m3 |

| PM10 | 1 day | 90 µg/m3 |

| Station | Latitude | Longitude | Altitude | ||||

| Suceava | SV-1 | 47.649259°N | 26.249009°E | 376 m | |||

| SV-21 | 47.668825°N | 26.281403°E | 289 m | ||||

| Botosani | BT-1 | 47.739945°N | 26.658999°E | 167 m | |||

| Iasi | IS-2 | 47.150951°N | 27.581920°E | 42 m | |||

| IS-41 | 47.213306°N | 27.611074°E | 186 m | ||||

| Categorie | EC annual (µg/m3) | Interpretation criteria. | |

| PM10 | PM2.5 | ||

| Low | <250 | <150 | Less than 18 daily exceedances or low-magnitude daily exceedances |

| Moderate | 251–750 | 151–500 | Frequent moderate daily exceedances, slightly above the value limit and/or occasional high exceedances |

| High | 751–1000 | 501–800 | Frequent daily exceedances and/or high daily concentration levels |

| Very high | >1000 | >800 | Severe pollution or extreme episodes |

| Categorie | EI (µg/m3) | Interpretation criteria. | ||

| PM10 | PM2.5 | PM10 | PM2.5 | |

| High | 1-25 | 1-25 | 2–3 days with 90–100 µg/m3 | 2–3 days, with values slightly above 50 µg/m3 |

| Very high | 26–100 | 26–100 | 3–4 days with 100–115 µg/m3 | 3–4 days with 60–70 µg/m3 |

| Extremely high | >101 | >101 | Long episodes and/or episodes with high peaks (>115 µg/m3). | Long episodes and/or episodes with high peaks (>75-90 µg/m3). |

| Categorie | TLI (µg/m3) | Interpretation criteria |

| No risk | 0 | PM2.5 below LV, insignificant toxic load |

| Low | 0.1 – 5 | Slightly exceeded or lower PM2.5/PM10 |

| Moderate | 5.1 – 12 | Significant exceedance and high proportion of PM2.5 |

| High | 12.1 – 20 | Severe pollution with toxic composition |

| Very high | > 20 | Critical episode, major toxicological risk |

| Year | BT-1 | IS-2 | IS-4 | SV-1 | SV-2 |

Directive 2008/50/EC |

Directive (EU) 2024/2881 |

| PM10 | |||||||

| µg/m3 | µg/m3 | µg/m3 | µg/m3 | µg/m3 | LV | LV | |

| 2019 | 27.30 | 32.10 | 20.22 | 22.60 | 32.87 | 40 µg/m3 | 20 µg/m3 |

| 2020 | 25.15 | 30.43 | 20.68 | 20.75 | 30.51 | ||

| 2021 | 23.27 | 30.73 | 20.47 | 22.29 | 28.54 | ||

| 2022 | 21.70 | 29.60 | 18.34 | 17.88 | - | ||

| 2023 | 20.72 | 27.18 | 18.62 | 18.53 | - | ||

| 2024 | 26.23 | 27.53 | - | 21.39 | - | ||

| Year | BT-1 | IS-2 | SV-1 |

Directive 2008/50/EC |

Directive (UE) 2024/2881 |

| PM2.5 | |||||

| µg/m3 | µg/m3 | µg/m3 | LV | LV | |

| 2019 | 13.34 | - | - | 25 µg/m3 | 10 µg/m3 |

| 2020 | - | - | 14.47 | ||

| 2021 | 13.74 | 20.21 | 15.14 | ||

| 2022 | - | 18.02 | 12.12 | ||

| 2023 | - | 14.91 | 11.23 | ||

| 2024 | - | 15.50 | 13.75 | ||

| Station | Period | Duration (days) | Average exceedance (µg/m3) |

EI (µg/m3) |

|

| SV-2 | 08-01-2020 | 10-01-2020 | 3 | 22.11 | 66.33 |

| IS-2 | 09-01-2020 | 10-01-2020 | 2 | 6.56 | 13.11 |

| SV-2 | 25-01-2020 | 28-01-2020 | 4 | 8.89 | 35.56 |

| IS-2 | 25-01-2020 | 28-01-2020 | 4 | 6.42 | 25.68 |

| BT-1 | 26-11-2020 | 27-11-2020 | 2 | 7.69 | 15.37 |

| IS-2 | 26-11-2020 | 28-11-2020 | 3 | 8.61 | 25.83 |

| IS-2 | 24-02-2021 | 26-02-2021 | 3 | 23.34 | 70.03 |

| Station | Period | Duration (days) | Average exceedance (µg/m3) |

EI (µg/m3) |

|

| BT-1 | 06-12-2019 | 08-12-2019 | 3 | 28.12 | 84.36 |

| SV-1 | 26-01-2020 | 27-01-2020 | 2 | 4.85 | 9.7 |

| BT-1 | 26-11-2020 | 27-11-2020 | 2 | 17.45 | 34.9 |

| SV-1 | 26-11-2020 | 27-11-2020 | 2 | 5.07 | 10.14 |

| SV-1 | 19-01-2021 | 20-01-2021 | 2 | 7.15 | 14.3 |

| IS-2 | 23-02-2021 | 26-02-2021 | 4 | 26.46 | 105.82 |

| BT-1 | 13-11-2021 | 14-11-2021 | 2 | 16.64 | 33.28 |

| IS-2 | 15-03-2022 | 16-03-2022 | 2 | 8.97 | 17.94 |

| IS-2 | 09-02-2023 | 11-02-2023 | 3 | 22.58 | 67.74 |

| IS-2 | 29-12-2023 | 30-12-2023 | 2 | 7.61 | 15.22 |

| IS-2 | 06-11-2024 | 08-11-2024 | 3 | 15.22 | 45.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).