1. Introduction and Literature Review

Change orders are a common occurrence in construction projects, irrespective of their size. However, their impacts can be particularly severe and unpredictable in large-scale projects. If not managed effectively, change orders can lead to substantial project disruptions such as claims, disputes, project halts, significant delays, and cost overruns. These disruptions can negatively impact all project stakeholders, including contractors, owners, and other involved parties. Given the critical importance of managing change orders, numerous studies have focused on analyzing the effects of change orders from various perspectives, aiming to better understand their causes, consequences, and potential mitigation strategies.

Several studies have highlighted the significant impacts of change orders on construction projects, particularly regarding delays, cost overruns, disputes, and other performance metrics. A fuzzy logic model was developed [

1]. In a study, a hybrid deep learning model combining convolutional neural networks (CNN) and recurrent neural networks (RNN) was utilized [

2]. Similarly, in another study, an event tree analysis model was developed to predict the cost implications of change orders, highlighting the financial challenges change orders can impose [

3]. The factors affecting project performance due to change orders have been categorized into four groups: project definition, stakeholder, execution, and performance and control [

4]. However, these models were often constrained to specific project types or regions and did not comprehensively address the financial impact on contractors. In a study on Saudi Arabian contractors, the causes of change orders were examined in which key causes were identified as: owner modifications, design errors, and unforeseen site conditions, leading to project delays and increased costs [

4]. The major causes and effects of change orders were similarly reviewed in a study, in which it was identified that the owner-initiated changes and design errors are the two primary reasons that contribute to cost and schedule overruns [

5]. While these studies provided valuable insights into the causes of change orders, their applicability is often limited by their regional focus, which restricts the generalizability of their findings.

Regarding project financing and cash flow, numerous studies have examined the impact of financial planning and cash flow variations in construction projects. These studies primarily addressed issues related to cash flow fluctuations and their effects on project delays, as well as the development of cash flow models for both small and large construction projects, without directly linking these fluctuations to change orders as a major contributing factor. For instance, the effects of cash flow variations on the performance of construction projects were investigated [

6]. It was concluded that such variations had a statistically significant impact on project outcomes, highlighting the importance of effective cash flow management in construction projects without addressing anything related to change order impacts. A cash flow management model was proposed, emphasizing the need for practical and accessible tools to help contractors manage cash flow effectively [

6]. The challenges of cash flow management faced by small- and medium-sized construction firms were explored. It was identified that delayed payments from clients and inadequate financial management pose challenges in maintaining a stable cash flow [

7]. A cash flow forecasting model was developed related to managing cash flow at the project portfolio level, providing insights into the complexities of maintaining financial stability across multiple projects [

8]. The relationship between cash flow management and project performance was examined by emphasizing the critical role of cash flow control in ensuring project success [

9]. Many other simulation techniques for cost management have been highlighted elsewhere [

10].

Although these studies provide important insights into cash flow management, including forecasting, risk analysis, and optimization, they often fail to comprehensively address the direct effects of change orders on cash flow. Change orders can have a severe impact on contractors’ cash flow, leading to financial instability and affecting their ability to sustain project profitability. Unfortunately, most of these studies did not tackle the impact of change orders on contractors’ cash flow specifically.

In Saudi Arabia, which is currently experiencing a massive construction boom across various sectors in alignment with Vision 2030’s goals for excellence and economic diversification, many large-scale projects are facing significant challenges. Recent studies have shown that major delays and cost overruns often affect construction projects [

11]. The poor management of change orders has been identified as a critical factor contributing to project disruptions [

12]. The impact of change orders on construction projects is severe, particularly in Saudi Arabia [

11]. Additionally, financial hardships faced by Saudi contractors due to lack of proper tools to assess the long-term financial implications of change orders have been regularly reported [

13]. In a study, it was revealed that 40% of contractors in Saudi Arabia suffered financial failure due to poor cash flow management [

14].

These findings motivated this study in developing a quantitative index model to enhance the understanding of change order impacts in the Saudi Arabian context. This proposed model is referred to as Change Order Impact Index (COII). This shows a significant gap regarding the impact of change orders on cash flow, particularly in terms of providing contractors with proactive tools to assess both short-term and long-term effects. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by developing a quantitative index model to evaluate the impact of change orders on contractors’ cash flow. By using Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Multi Attribute Utility Theory (MAUT), this Change Order Impact Index (COII) will offer contractors an effective tool for managing financial risks and ensuring overall project success.

2. Research Methodology Phases

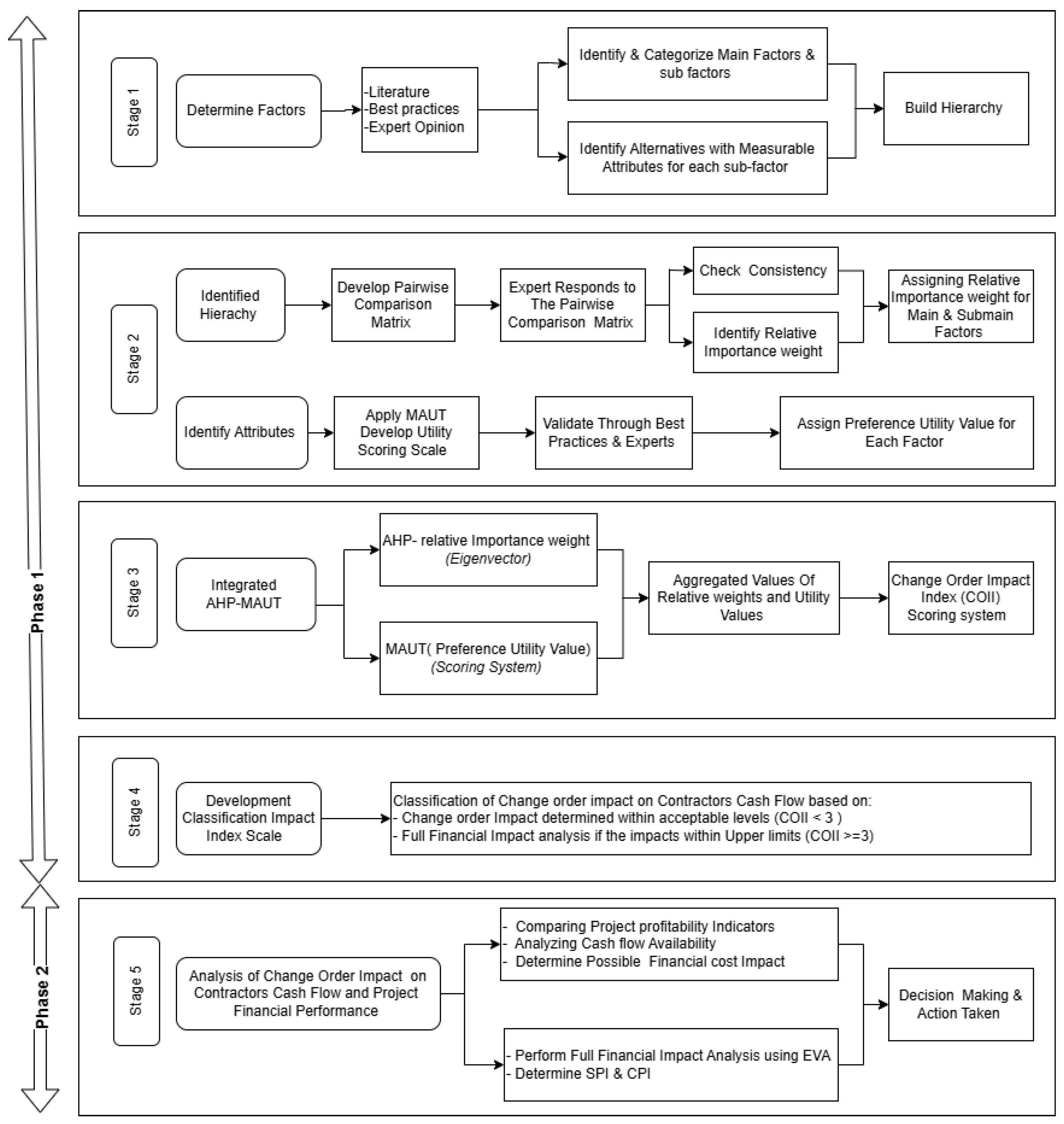

The research methodology, depicted in

Figure 1, is divided into two phases. The first phase involves developing a classification impact index model for change orders, concentrating on their potential effects on project cash flow. This phase considers a wide array of factors that influence project financing and affect the financial performance of the project, in addition to contractors’ cash flow. These elements are then systematically organized into a hierarchy, categorizing them into main and sub-main factors. The Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) is then employed to evaluate the relative importance of these factors, followed by verification of the consistency and reliability of the derived weights.

In the second phase of the methodology, the focus shifts to developing a quantifying index that measures the impact of change orders on contractors’ cash flow. This process involves a comprehensive integration of the relative weights determined in the first phase with specifically assigned utility values. These elements are combined to produce a unified, singular quantifying index. This index is designed to facilitate a proactive and thorough evaluation of the potential impacts that change orders could have on the cash flow of a construction project, providing contractors with a valuable tool for advanced planning and effective financial management.

2.1. Stages of Phase One

Phase one of the research methodology is divided into four stages, as shown in

Figure 1. These stages are designed to achieve the research objectives in a systematic manner.

2.1.1. First Stage

In the first stage, the task is to pinpoint and categorize the factors that are linked to how change orders affect project cash flow, organizing them into main and secondary elements. This categorization is essential for establishing a hierarchical structure that delineates the connections between the overall objective, the criteria, and the sub-criteria. Within this framework, each subfactor is broken down into options that possess quantifiable attributes. These measurable attributes refer to utility scores, which provide a concrete and quantifiable means of assessing the impact of each factor, thereby facilitating a structured and objective evaluation of the influence of change orders on the cash flow of construction projects.

2.1.2. Second Stage

In the second stage, the relative importance of each main and subfactor in the previously developed hierarchical model is quantified using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). This process entails pairwise comparisons to establish the relative priorities of these factors at each hierarchical level. The AHP method allows for the calculation of the weight of each factor by systematically comparing it against others in the same category, thus providing detailed quantitative insights into its contribution to the impact of change orders on project cash flow. Following this, the unity value for each factor is determined based on an extensive review of relevant literature, industry standards, and expert feedback. The multi-attribute utility method is then utilized to assign a utility value to each factor, reflecting its significance or score level. This method incorporates a range of attributes for each factor, ensuring a thorough and precise evaluation of their respective impacts within the project’s framework.

2.1.3. Third Stage

In the third stage, the integration of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Multi-Attribute Utility Theory (MAUT) is utilized. This combined approach forms the basis for constructing the Change Order Impact Index (COII). The phase concentrates on employing MAUT for determining the preference utility values for each attribute of the subfactors. By melding AHP with MAUT, the study effectively establishes a robust model that quantifies the impact of change orders, as represented by the COII, ensuring a detailed and multi-dimensional evaluation of change orders’ effects on construction projects.

2.1.4. Fourth Stage

The fourth stage involves developing a scale for the classification impact index, intended to categorize the likely effects of change orders on project cash flow. This development makes use of the Change Order Impact Index (COII), which was determined in the study’s third stage.

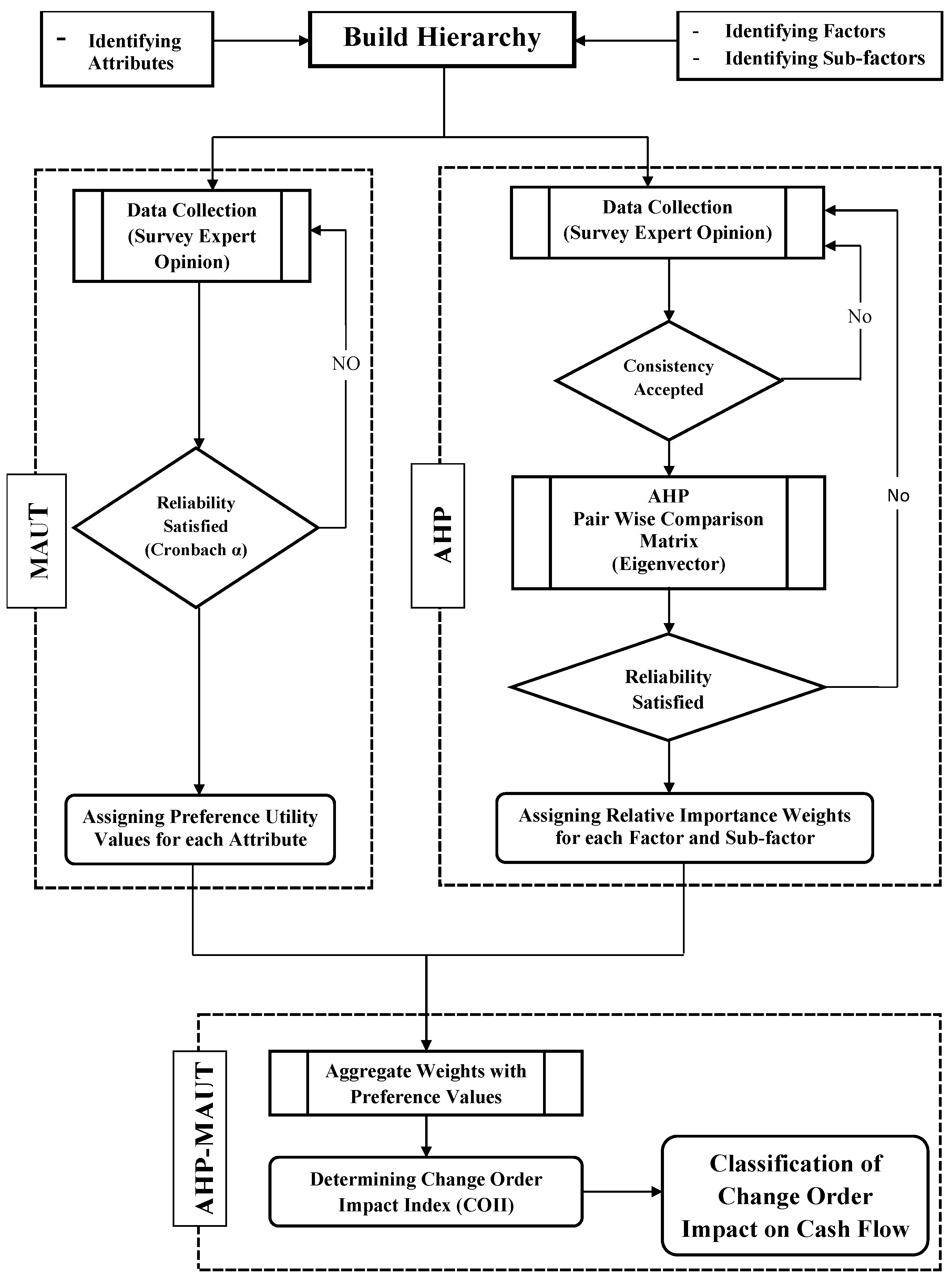

The completion of the first four stages represents the accomplishment of the research’s initial phase one, which is centered on developing a model for classifying the impact of change orders on project cash flow. This phase encapsulates the creation and refinement of an index model to systematically evaluate how change orders affect the financial flow of construction projects. The methodology for phase one and its four stages is shown in

Figure 2.

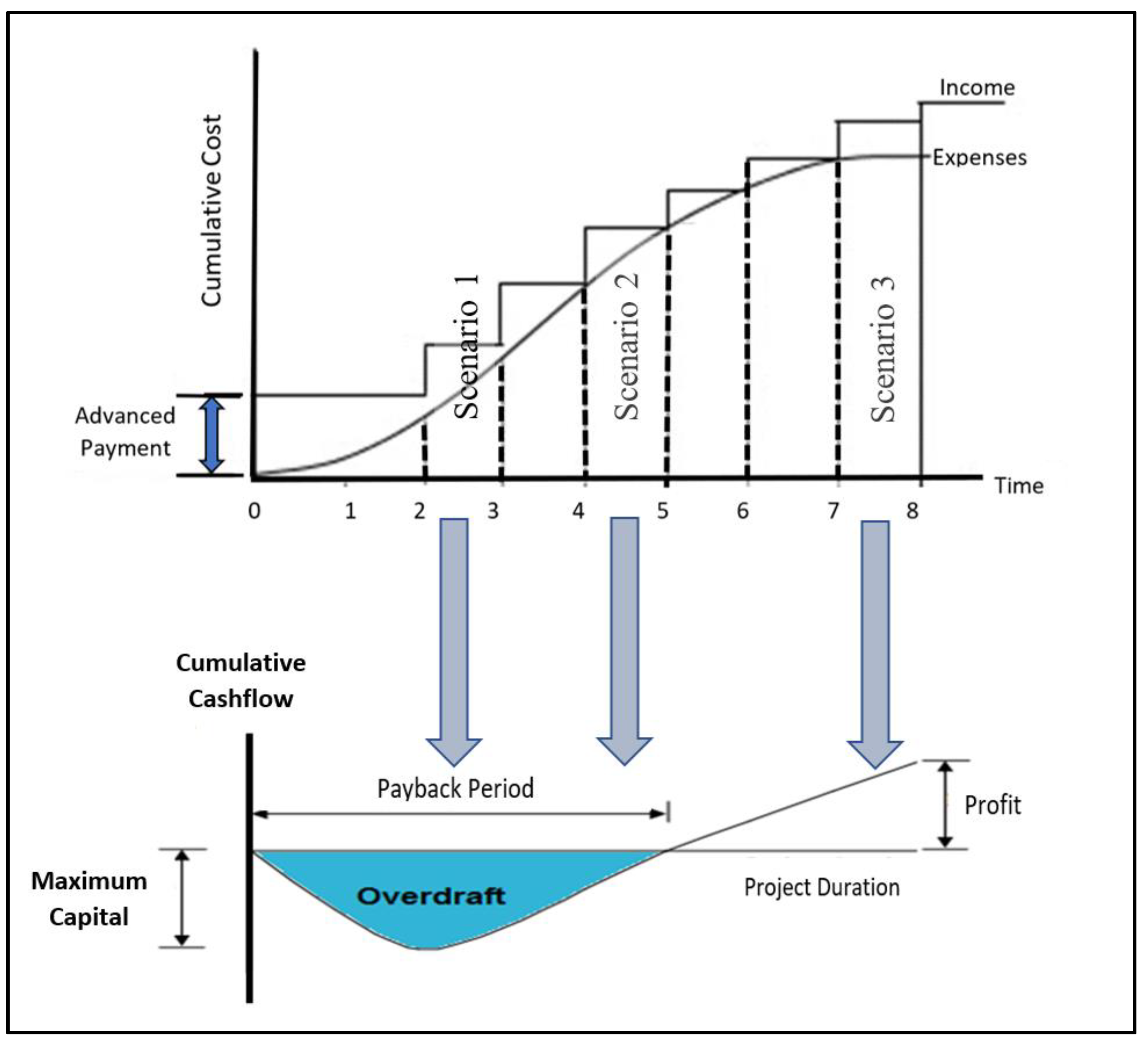

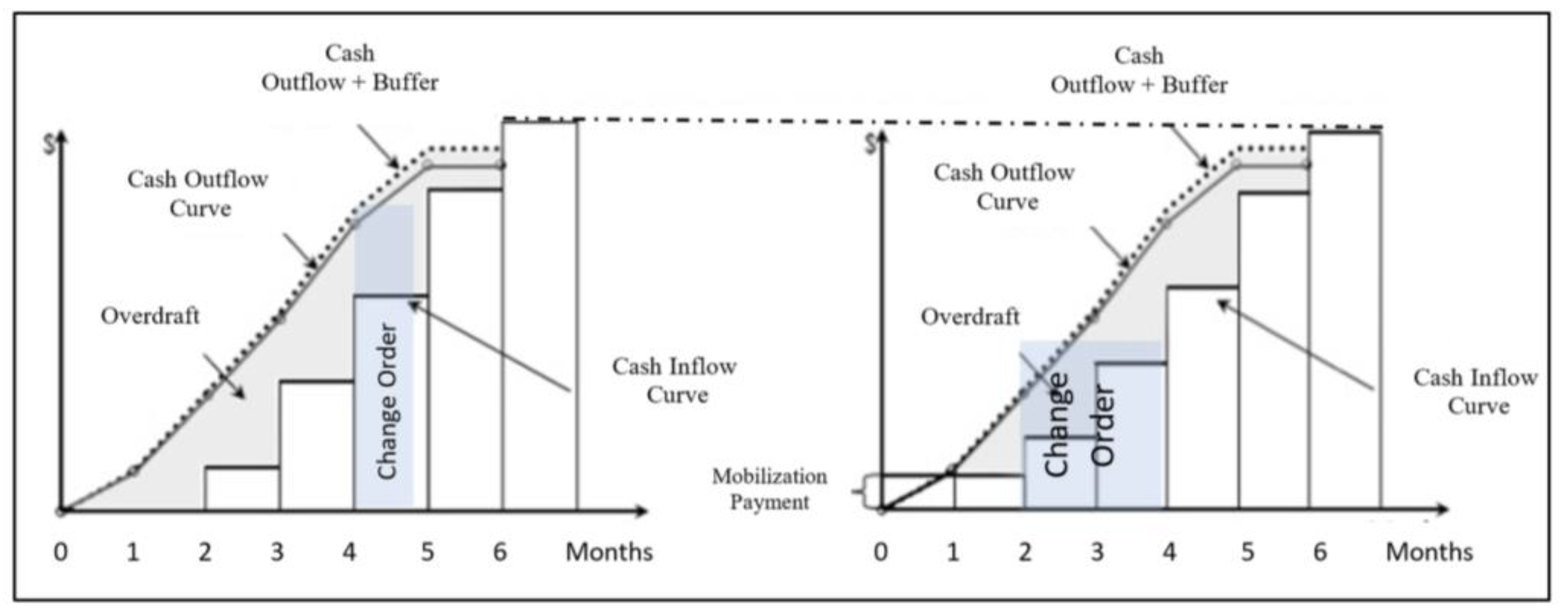

2.2. Stage Five of Phase Two

In the second phase, the change order impact on the project’s financial performance is evaluated based on the imposed change order. This phase is important if the COII value is relatively high and can jeopardize the financial performance of the construction project. After this phase, the contractor will not only have a clear understanding of the impact of the change order on their cash flow but also its impact on the overall financial performance of the project.

This phase will provide the contractors with different scenarios to predict and mitigate different impacts of the change order on the project financial and schedule performance and therefore provide the contractor with a powerful tool to communicate these impacts among stakeholder and provide clear justifications to negotiate or to litigate these impacts proactively.

In this phase, the profitability indicators along with the schedule performance index (SPI) and cost performance index (CPI) are utilized to quantify these impacts. The Eared Value Analysis (EVA) in then used to evaluate different scenarios to mitigate possible impacts on the overall project performance. The analysis also considers aspects such as the availability of cash liquidity and the financial impact associated with the timing of the change orders. A crucial part of this phase is the timing analysis, which correlates with the project’s S-curves. These curves depict the relationship between time and project finances, encompassing both inflows and outflows of funds impacted by the imposed change order. This section is further explained in the model analysis section.

3. Data Collection and Analysis

To construct the COII model, a substantial amount of data is required, focusing on various factors that affect the financial performance of a project and the cash flow of contractors. These factors should be organized into categories and then structured hierarchically. As detailed in the methodology section, it’s essential to assign a relative weight to each factor to reflect its impact on the contractor’s cash flow. For each factor, a standardized utility scale and a corresponding utility score need to be established. These scores, combined with the factors’ relative weights, are aggregated to develop the COII index. The section highlights the data collection processes used in the development of this model.

3.1. Factors Affecting the Contractors Cash Flow and Project Financial Performance

An extensive literature review was conducted to identify key factors influencing contractors' cash flow and financial performance in construction projects. Several studies have highlighted critical issues such as cost and time overruns, ineffective cash flow models and fluctuations in client financial statuses [

6]. Payment delays, cost escalations, scheduling inaccuracies, and the impact of change orders have been identified as significant factors [

5,

6,

15]. Additionally, late payments, lengthy claim resolution processes, loan repayments, consultant directives, and interest rate changes have been identified as significant challenges impacting cash flow [

6]

Broader economic conditions, project duration, accounts payable and receivable, construction costs, retention practices, loan repayments, and tax considerations have also been identified as major influences on financial performance [

16]. Contractor performance has been linked to factors such as experience, resource management, financial stability, and client relationships [

17]. A framework integrating financial and non-financial elements, such as project costs, adherence to schedules, contractual compliance, and risk management strategies, has been proposed to comprehensively assess financial performance [

17].

The impacts of different contract types, such as lump-sum and unit price contracts, on cash flow have been explored [

3]. The significant effects of change orders, particularly their timing, scope, and complexity, on financial outcomes have been analyzed [

2]. Effective project management practices, such as monitoring schedules, resource allocation, and clear communication, have been found to be crucial for enhancing cash flow [

7]. Financial risk management has also been highlighted as important for reducing financial uncertainties and stabilizing cash flow [

9].

Further studies have identified factors causing delays in Saudi Arabian construction projects, such as ineffective project management, design changes, financial constraints, and labor shortages [

12]. Factors influencing change orders in Saudi Arabia's oil and gas sector, including design errors, scope modifications, client demands, and unforeseen site conditions, have been identified [

4]. Contractor selection criteria, including technical competence, past performance, financial capacity, and project management skills, have been found to be critical to the success of public projects [

18]. Key performance factors during the implementation phase of construction projects in Iraq, including project planning, risk management, resource availability, and stakeholder engagement, have been identified [

19]. Causal relationships between various delay factors, such as poor planning, lack of coordination, financial issues, and contractor inexperience, have been analyzed [

20]. The positive impact of effective change order management on project success has been demonstrated [

1]. The effects of change orders on timelines, costs, and project outcomes have been assessed using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) [

21].

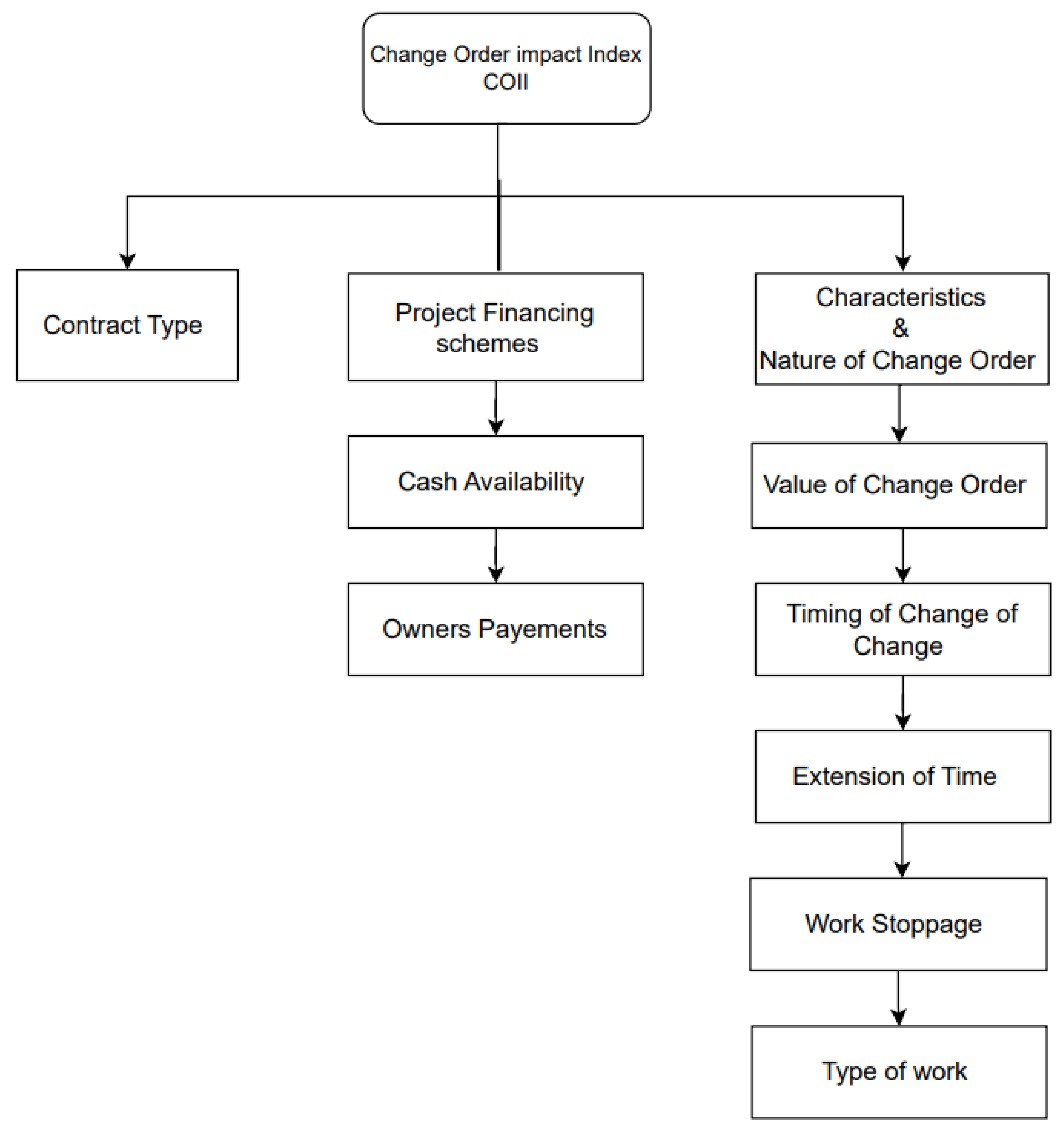

Based on the findings from these studies and extensive interviews and surveys with local experts, it has been determined that contract type, project financing schemes, and the characteristics and nature of change orders are the primary factors affecting contractor cash flow. Specifically, cash availability and owner payments are identified as subfactors for project financing schemes, while the value of change orders, timing of change orders, extension of time, work stoppage, and type of work are categorized as subfactors under change order characteristics. The factors and subfactors considered in this study and organized into main and subfactors hierarchy as shown in

Figure 3.

3.2. Factors Utility Values

For each selected factor, specific attributes that contribute to the overall financial performance and therefore affect the contractors cash flow will be measured to assess their impact. The attributes considered in this study for the factors and subfactors are shown in

Table 1.

In order to develop the classification impact index model, necessary data regarding the relative weights of the main and subfactors were collected through a survey sent to contractors, consultants, and experienced construction practitioners in the industry via a questionnaire. The respondents of this survey are shown in

Table 2. Utility values were obtained from best practices, standards, and previous studies.

4. Data Analysis and Model Development

In this section, data collected from the questionnaire surveys are analyzed and interpreted. The findings are also discussed to give better reflections on the proposed study.

4.1. The Sample Characteristics

The first part of the survey form is designed to gather general information about respondents, including the name of their organization, type of organization, job/position, education level, years of experience, industry experience, and the most common types of contracts used in their projects. This section aims to provide an understanding of the background and experience of the respondents.

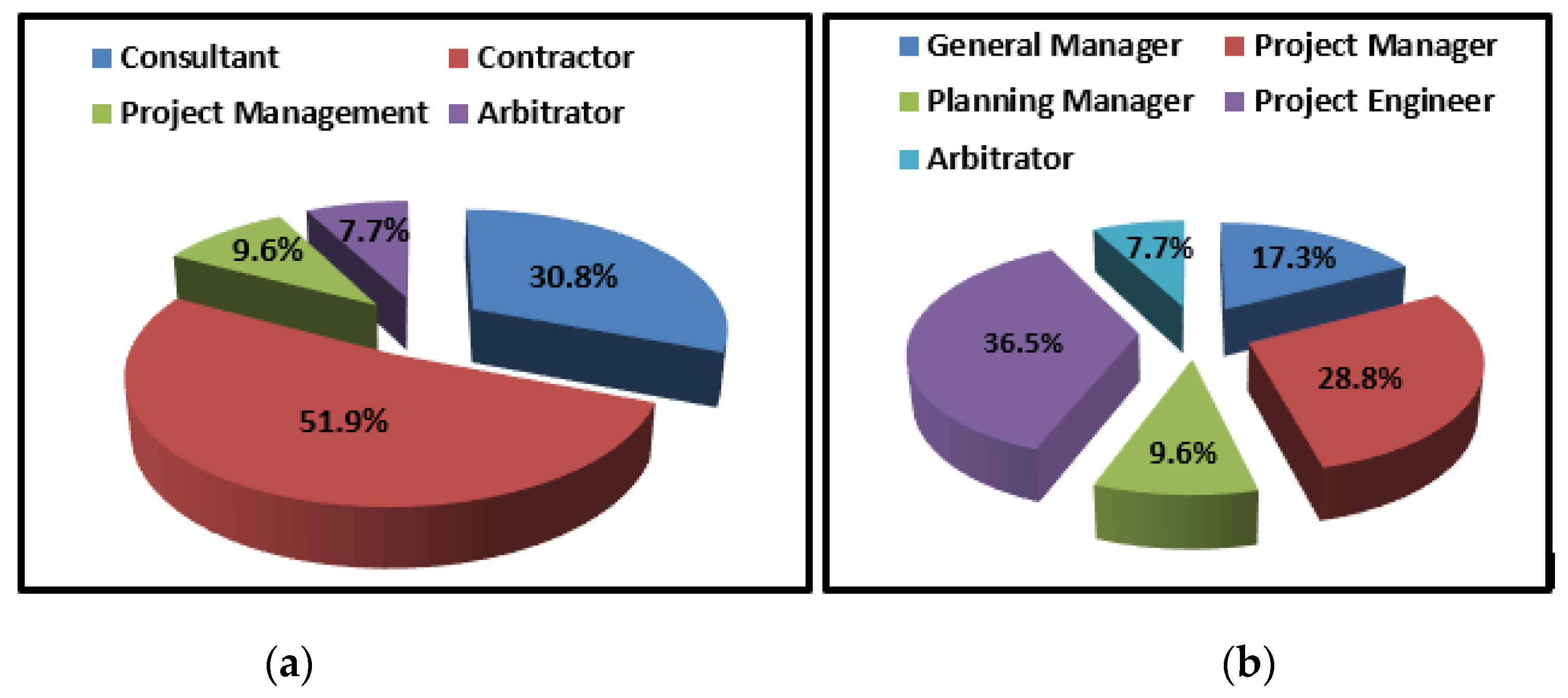

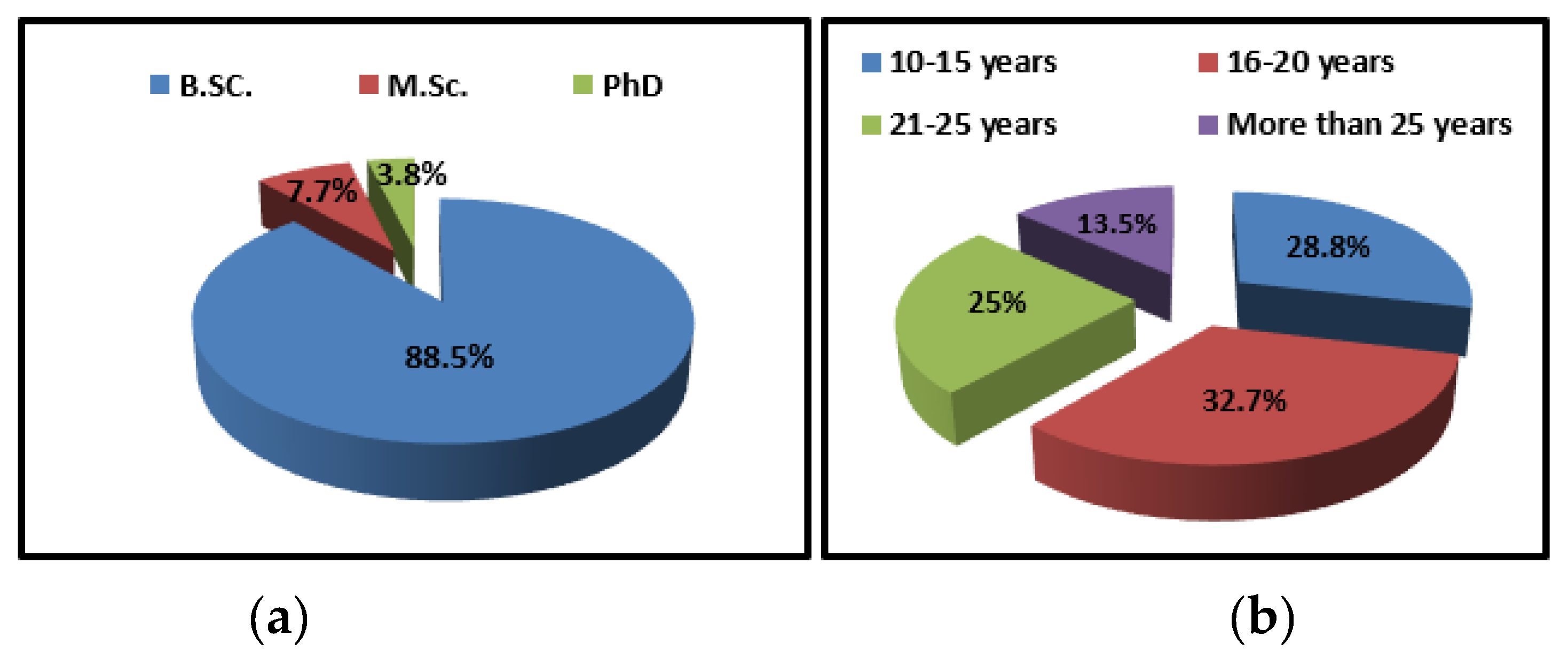

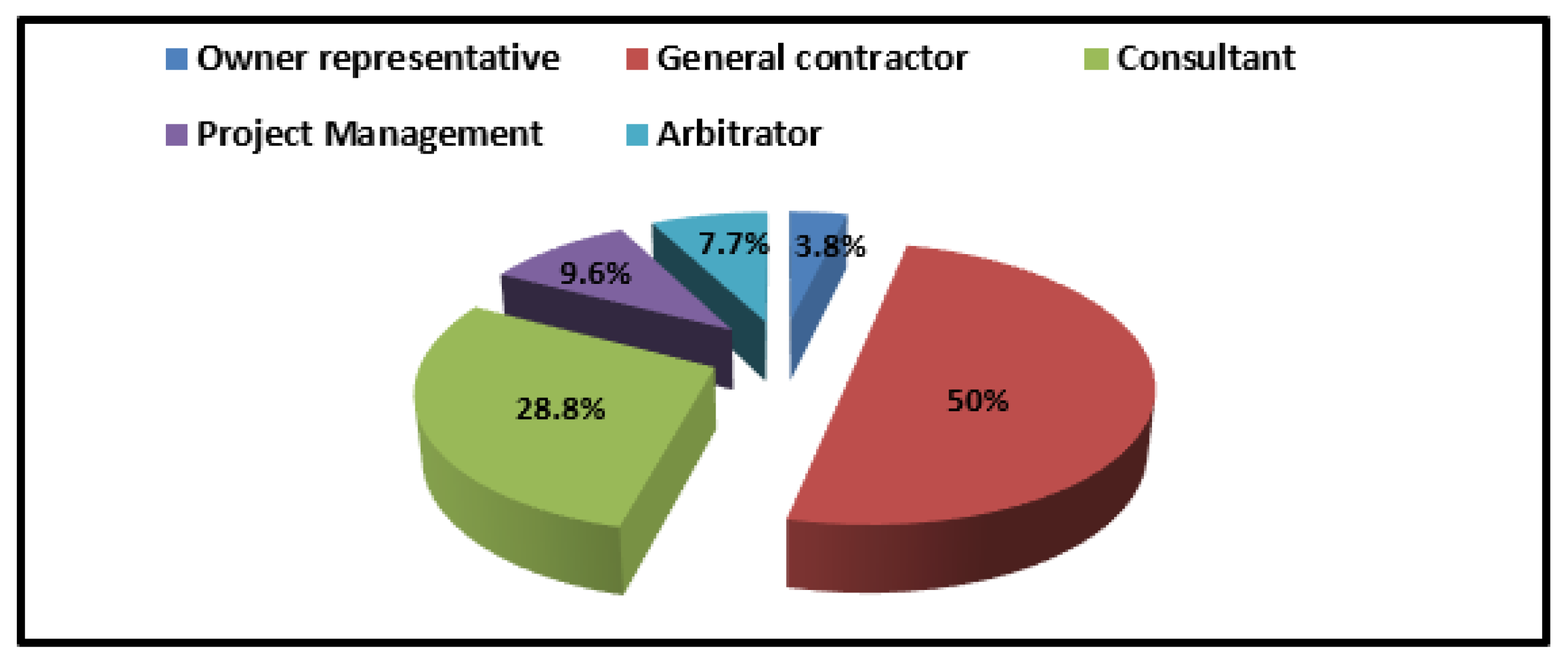

As shown in

Figure 4a, the types of organizations that respondents work for include contracting companies (51.9%), consultant offices (30.8%), project management offices (9.6%), and arbitration offices (7.7%). Additionally,

Figure 4b provides insight into respondents’ job positions within these organizations, with 36.5% working as project engineers, 28.8% as project managers, 17.3% as general managers, 9.6% as planning managers, and 7.7% as arbitrators.

The Academic Qualifications of participants are shown on

Figure 5a distributed as 88.5% of respondents holds B.Sc. degree, 7.7% holds M.Sc. degree and 3.8% holds PhD degree. Moreover,

Figure 5b shows the experience level among the participants, where 28.8% have experiences between 10 and 15 years, 32.7% between 16 and 20 years, 25% between 21 and 25 years and 13.5% more than 25 years of experience.

Figure 6, titled “Industry Previous Experience,” shows respondents’ prior experience in the construction industry, indicating that 50% have experience in contracting, 28.8% in consulting, 9.6% in project management, 7.7% in arbitration, and 3.8% as owner representatives.

4.2. Determining Relative Weights

The relative importance weights for main and sub-main factors were calculated from data collected through pairwise comparison matrices from the distributed surveys. Out of 120 surveys sent, only 52 met the necessary criteria for inclusion in this study. This is mainly due the complex nature of the pairwise comparison matrix, leading to numerous surveys being either incomplete or not meeting consistency standards, with a consistency ratio exceeding 10% as stipulated by AHP guidelines. The relative weights for the main factors are referred to as Level 1 (W1), while the relative weights for subfactors are referred to as Level 2 (W2). Finally, the overall relative weight (W3) is the multiplication product of W1*W2. These relative importance weights for factors and subfactors considered in this research are shown in

Table 3.

4.3. Data Reliability

Reliability refers to the consistency and stability in the results of a test or scale. The reliability of expert responses is verified using Cronbach’s alpha approach. Cronbach’s alpha is a coefficient typically known as the coefficient of reliability that measures internal consistency. Cronbach’s alpha is the most widely applied estimator of reliability. Cronbach’s alpha is the ratio of the true variance to the total variance of the measurement and a function of several observations, variance and covariance and is determined using Equation (1).

where:

n: number of points.

Vi: variance of scores for each point.

V: total variance of overall points.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of reliability has (0–1) scale value. The higher the score, the more reliable the data. A value of (0.70) or greater is typically considered to be acceptable. Typical values for Cronbach’s alpha and their interpretations are summarized in

Table 4.

Main Factors Relative Weight Data Reliability

To verify a respondent’s reliability, each variance is measured against the overall variance using Cronbach’s alpha. The reliability of for the main and subtractors are calculated and ranged from 0.75–0.91 showing high reliability for these weights. The reliability for main factors and sub factors are shown in

Table 5 and

Table 6 respectively.

4.4. Determining Utility Values

In this section, the identified attributes for each subfactor are evaluated using the MAUT technique. Each attribute is given a utility value in terms of its contribution toward the change order impact on contractor’s cash flow. The utility value is represented on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 represents minimal impact on the contractor’s cash flow and 5 reflects severe impact on the contractor’s cash flow. The utility value for each subfactor is obtained from standards, best practices, and previous studies. These values along with their score interpretations are illustrated in the following sections.

4.4.1. Cash Availability

Cash availability is a critical factor impacting contractor cash flow in construction projects. Several studies have highlighted the importance of effective cash flow management in mitigating financial risks and ensuring project success [

6,

9]. It has been researched that while advanced payments are beneficial for contractors, they do not necessarily guarantee positive project cash flow but success of any project depends on organizational management and project performance [

22].

Payment delays, change orders, and project financing schemes are significant factors affecting cash flow [

16,

23,

24,

25]. Effective project management practices, such as schedule monitoring and resource allocation, are crucial for maintaining positive cash flow [

7]. Additionally, the timely resolution of claims and the implementation of robust financial risk management strategies are vital for stabilizing cash flow [

9,

26]. In a study it was concluded that contractors' limited access to finance, particularly bank loans, poses a major barrier to project performance [

27]. A study defined 19 key indicators, including 17 financial and 2 non-financial, to evaluate and model contractor liquidity based on multiple discriminate analyses [

28]. Understanding the interplay of these factors and implementing appropriate strategies can significantly improve a contractor's financial performance and overall project success.

To assess the impact of cash availability on contractor cash flow, a scoring system has been developed. This system assigns a score from 1 to 5, where 1 indicates minimal impact and 5 signifies severe impact. A score of 1 reflects a scenario of ample cash reserves, while a score of 2 suggests a moderately complex financial situation. A score of 3 indicates reliance on bank loans, which can have mixed effects on financial stability. A score of 4 represents a heightened financial risk, warranting further investigation. Finally, a score of 5 signifies reaching loan limits, which can have severe implications for the contractor's financial health. This scoring system provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the financial stability of construction projects. The utility values and their impact interpretations are shown in

Table 7.

4.4.2. Owners Payments

The status of owner payments significantly influences a contractor’s cash flow. Timely payments from owners are essential for maintaining the financial health of construction projects. Delays in payments disrupt cash flow, leading to financial strain, project delays, and quality issues [

23,

24]. Effective cash flow management, including accurate forecasting and risk assessment, is critical to addressing these challenges.

Contractual provisions, such as those outlined in FIDIC contracts, play a pivotal role in managing payment terms and resolving disputes [

29,

30]. Adherence to these provisions helps ensure timely payments and reduces financial risks. Additionally, delayed payments can negatively impact worker productivity, which is vital for the overall success of projects [

31].

To quantify the impact of payment delays, a scoring system is developed. This system assigns a score ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 represents timely payments and 5 indicates significant delays, as illustrated in

Table 8. By using this scoring system, contractors can assess the severity of payment delays and implement proactive measures to mitigate their effects. The scoring system, aligned with FIDIC clauses, provides an effective framework for evaluating how payment timing influences the financial stability of construction projects. However, it is also essential to consider external economic factors and market conditions, as they can have a significant impact on cash flow dynamics.

4.4.3. Contract Types

Contract types significantly influence contractors’ cash flow, with varying levels of financial risk associated with each type. The choice of contract type plays a key role in defining a contractor’s financial risk profile. Lump sum contracts, while providing cost certainty for the owner, can expose contractors to significant financial risks in unforeseen circumstances. Unit price contracts offer greater flexibility but require precise cost management and accurate measurement to avoid disputes. Cost-plus contracts transfer much of the risk to the owner but may lead to cost overruns if not properly controlled. Timely owner payments are critical to sustaining contractor cash flow and minimizing the negative effects of delays, as highlighted [

23,

24]. Provisions in FIDIC contracts [

29,

30] play a crucial role in managing payment terms and resolving disputes. Furthermore, understanding the impact of delayed payments on workforce productivity is vital for project success [

31]. Effective cash flow management, supported by accurate forecasting and risk assessment, is indispensable for reducing financial risks. Cash Flow Risk Index (CFRI) was introduced to assess risks impacting cash flow, aiding informed decisions for improved outcomes and financial stability [

9]. A scoring system was developed to assess these impacts on a scale of 1 to 5. This scoring framework, along with its interpretations, provides contractors with a comprehensive tool to manage cash flow and effectively navigate project risks based on the contract type. The scores and their corresponding interpretations are presented in

Table 9.

4.4.4. Change Order Values

The potential impact of change order values on contractor cash flow can be comprehensively understood by integrating a Multi-Attribute Utility Theory (MAUT) scoring system with relevant FIDIC clauses. This approach enables contractors to anticipate the financial implications of change orders based on their value and the associated contractual conditions. For instance, minor change orders might have minimal impact, while significant changes can lead to substantial disruptions or severe financial challenges. By associating these scenarios with specific FIDIC clauses, contractors can gain insights into how contractual terms affect cash flow, enhancing their ability to manage risks and maintain financial stability amid project modifications. This scoring system, presented in

Table 10, offers a structured approach to assessing the impact of change order values on cash flow, ranging from minimal to severely impactful scenarios within the context of FIDIC contractual terms. The framework is supported by insights from studies conducted [

8,

30,

32].

4.4.5. Timing of Change Orders

The timing of change orders has a significant impact on contractor cash flow and overall project financial performance. Several studies revealed [

11,

21] .

The possible effects of change order timing on contractor cash flow are presented in

Table 11.

4.4.6. Time Extension

Time extensions related to change orders significantly impact contractor performance and cash flow, as evidenced by numerous studies [

21,

33,

34,

35]. These extensions often result in increased overhead and labor costs, payment delays, and disruptions to workflows, which collectively hinder project timelines and financial stability. Insights from Purnus and Bodea [

8] further support these findings, emphasizing that effective financial planning and cash flow analysis are essential for mitigating the risks associated with change orders.

The financial impact of time extensions on contractors’ cash flow can be systematically evaluated using structured methodologies. For instance, tools like the Multi-Attribute Utility Theory (MAUT) framework, as discussed in prior research, provide a comprehensive method for assessing these impacts. Within this context, the Time Extension Impact Score and its Interpretation are systematically represented in

Table 12. This table offers a clear breakdown of the severity of time extensions on contractor cash flow and performance, serving as a practical guide for contractors to evaluate and mitigate risks.

4.4.7. Addition, Omission, and Rework

Addition, omission, and rework significantly impact the performance of construction projects and the cash flow of contractors, creating complexities that demand precise evaluation and management. A structured scoring system, ranging from 1 (no impact) to 5 (critical impact), provides contractors with a practical tool to assess the financial implications of these changes. This methodology enables better risk management and financial planning, ensuring that contractors can effectively navigate the challenges posed by change orders. The significance of these impacts and the necessity for their quantification are emphasized by research conducted in numerous studies [

6,

11,

26,

34,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. These studies collectively highlight the critical role of robust change management practices in mitigating the adverse effects of addition, omission, and rework on project performance and contractor cash flow. The interpretations of the impact of these actions on contractors’ cash flow are comprehensively detailed in

Table 13.

4.4.8. Work Stoppage

Work stoppages in construction contracts are often governed by FIDIC clauses, which provide a structured framework for managing and mitigating their impact. These clauses are instrumental in determining the extent to which stoppages affect a project, particularly in terms of the contractor’s cash flow. The levels of work stoppages, associated scores, and their impact on the contractor’s cash flow are controlled by relevant FIDIC clauses. A score of 1 corresponds to no stoppage, as per FIDIC Clause 14.1, which ensures timely payments to maintain continuity. A score of 2 represents minor stoppages, aligning with Clause 20.1, which addresses claims and disputes that may cause brief interruptions. Moderate stoppages, scored as 3, are linked to Clause 8.4, which provides time extensions for delays due to employer actions or unforeseen conditions. Significant stoppages, scored at 4, are governed by Clause 19, which deals with force majeure events disrupting project progress. The most severe stoppages, assigned a score of 5, relate to Clause 69, which addresses substantial non-performance or default, potentially leading to termination. These scores and their impact interpretations on the contractor’s cash flow are shown in

Table 14. This structured approach helps contractors understand and quantify the impact of work stoppages on their cash flow, guided by the FIDIC clauses.

The impact of work stoppages on contractor performance and cash flow is supported by studies highlighting the importance of frameworks like FIDIC clauses. Some studies emphasize challenges from change orders affecting costs and schedules [

41,

42], while others press the need for structured approaches to mitigate delays and disruptions [

33,

35]. Additionally, the risk management's role in addressing unforeseen conditions, reinforcing the relevance of FIDIC’s provisions for managing stoppages effectively has also been highlighted [

43]. These studies highlight the critical role of effective risk management and communication in mitigating the adverse effects of work stoppages caused by change orders.

4.5. Change Order Impact Index Calculation

The Change Order Impact Index (COII) is determined by integrating the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) and the Multi-Attribute Utility Theory (MAUT) techniques. In this approach, the relative importance weight for main factors (Wi) and relative importance weight for subfactors (Vij) is calculated using AHP and then multiplied by the utility score (Pvij) for each factor, as determined by MAUT. The COII is mathematically computed by summing the products of the weights and utility values for all factors.

The relative importance weight represents the significance of the main factors, as illustrated in

Figure 3. These main factors include Contract Type, Project Financing Schemes, and Characteristics and Nature of Change Order, with respective weights of 0.44, 0.30, and 0.26. The relative importance weights for the subfactors associated with each main factor are depicted in the hierarchy in

Figure 2. The utility score reflects the status of each subfactor, as shown in

Table 2. The utility scores for these factors are detailed in

Table 7,

Table 8,

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11,

Table 12,

Table 13 and

Table 14 .

where:

COII: Change order impact index.

Wi: Relative weight of criteria main factors i.

Vij: Weight of subfactor j within the i factor.

PVij: Utility score for subfactor j within main factor i

4.5.1. Change Order Impact Index Interpretation

The proposed classification COII scale is divided into four different categories as presented in

Table 15, ranging numerically from 1 to 5, and linguistically from minor to severe. These values are determined based on their impact on the change order impact index.

4.5.2. Change Order Impact Index Analysis

According to the developed Change order Impact Index (COII), as presented in

Table 15, if the COII value is greater than three, further analyses on the possible impact of the change order are needed to mitigate its effect on the contractor’s cash flow. This is illustrated in Phase Two of the Methodology section. In this section, the COII analysis is thoroughly investigated, and analyses are conducted according to different profitability indicators, aiming to provide contractors with a proactive tool to mitigate such change orders with minimal impacts on their financial status and cash flow. In addition, the analysis provides a transparent tool for project stakeholders to communicate and resolve predicted impacts proactively. A detailed analysis of the project profitability indicators impacted by such change orders is shown in

Figure 7.

The change order impact analysis begins with calculating the Change Order Impact Index (COII) value. If this value exceeds three, as indicated in

Table 3, further investigation and analysis must be conducted to determine the exact impacts on the contractor’s cash flow, as well as the time and cost variations affecting the overall performance of the project. At this stage, a detailed financial analysis is required, measured against the contractor’s financial status in relation to the project’s progress. This allows the contractor to accurately identify all potential impacts on cash flow, as well as the project’s schedule and budget.

In this phase, the contractor calculates the precise impact by using the Schedule Performance Index (SPI) to assess how the change order affects the project schedule. This assessment is then compared to the project S-curve, enabling adjustments to be made with minimal disruption and negative consequences. The contractor aims to avoid implementing change orders during periods when cash flow is financed through loans with interest charges or when overdraft conditions occur, as these financial stages present heightened risks. Over-drafting, which occurs when additional funds are withdrawn beyond the available balance, is typically accompanied by high interest rates and financing complications that can significantly increase the overall cost burden for the contractor.

To mitigate such risks, the contractor seeks to avoid change orders during these financially sensitive periods, thereby reducing financing complications and avoiding increased interest payments. This is particularly important when negative drafts are occurring, as the interest and other associated costs are higher when cash flow is already strained. To navigate these challenges, the contractor considers different scenarios to assess their overall impacts, focusing on avoiding overdraft periods and other financial difficulties. By defining various potential scenarios, the contractor is better equipped to negotiate with the project owner to minimize the effects of change orders, ensuring the least possible impact on both the project and the contractor’s cash flow, as depicted in

Figure 8.

Moreover, the cost performance index will also be calculated to examine the impact on the project cost and evaluate different financing scenarios on how to accommodate the change order with minimal financial impacts, as illustrated in

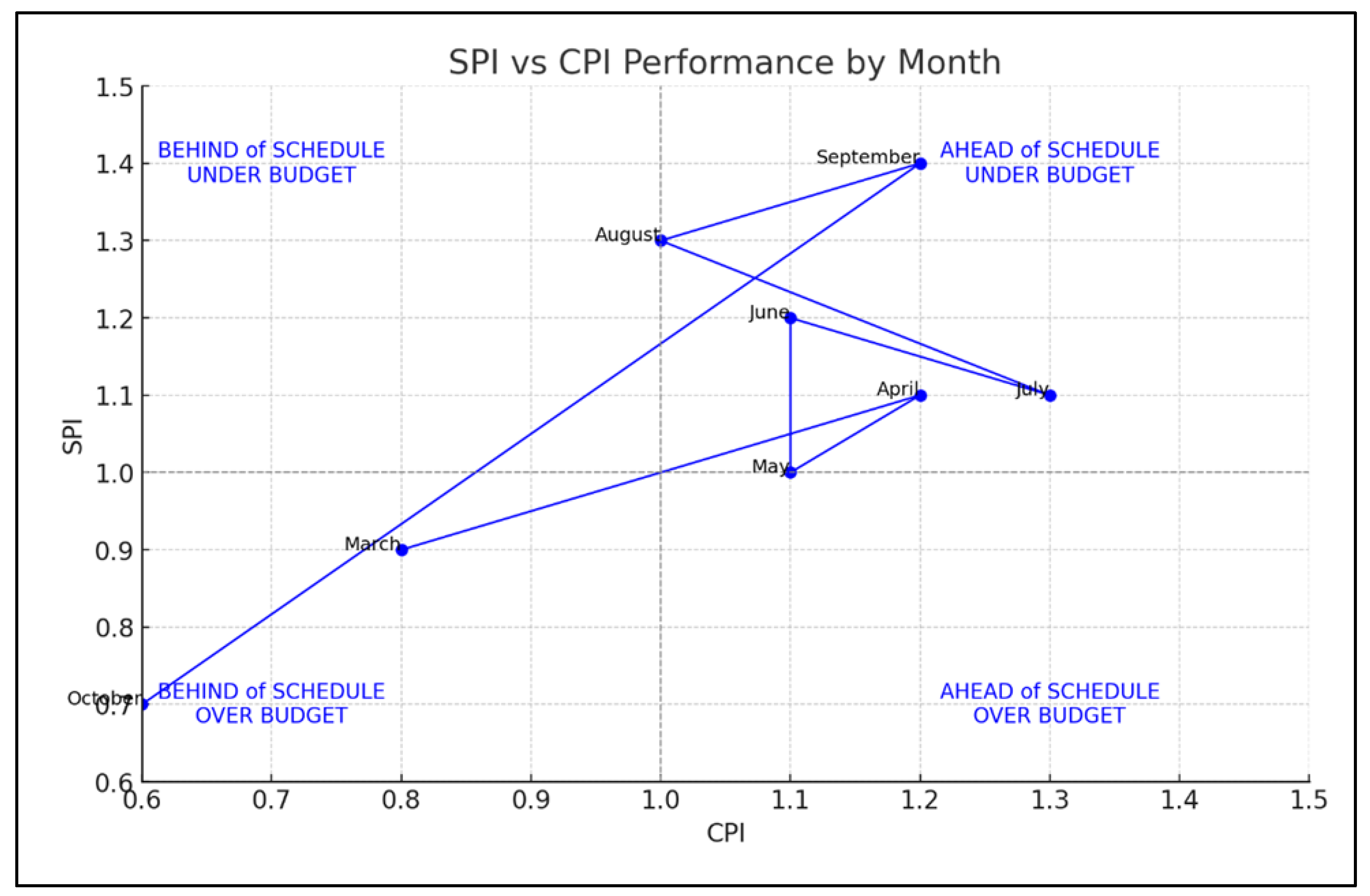

Figure 9. These scenarios are well defined, and their impacts do not severely affect the contractor’s performance related to financial and schedule obligations. Rather, they can be claimed and resolved through negotiations or arbitrations. These impacts and all possible scenarios will be reflected on the overall contractor’s performance, and are quantified in terms of cost and time using earned value (EV).

Earned Value (EV) analysis is used to quantify the impact of change orders, effectively reflecting their influence on project timing through the Schedule Performance Index (SPI) and on project cost through the Cost Performance Index (CPI), as illustrated in

Figure 10. The position of the point on the EV graph indicates overall project performance: a point in the first quadrant suggests favorable schedule and cost performance (positive SPI, positive CPI); the second quadrant indicates schedule delays but controlled costs (negative SPI, positive CPI); the third quadrant reflects both delays and budget overruns (negative SPI, negative CPI); and the fourth quadrant indicates the schedule is on track while costs are exceeding the budget (positive SPI, negative CPI). This comprehensive visualization enables contractors to evaluate the impacts of change orders and effectively communicate them to stakeholders, providing a basis for dispute resolution or arbitration when necessary. Depending on the severity and expected impact of a change order, the contractor can use this evaluation to justify acceptance or rejection, forming the basis for any subsequent dispute resolution or litigation.

4.6. Model Validation

The developed methodology and classification model were explained to contractors and experienced construction practitioners in the industry. After presenting the models and explaining how they work and can be used to classify and predict the possible impact of change orders in contractor’s cash flow, the experts were asked to evaluate the applicability and validation of the developed model and methodology. The evaluation is based on a set of questions that are listed to be answered by (20) experts with minimum experience not less than 10 years.

Table 16 illustrated the scale used (based on researcher point of view) to classify the results of experts evaluations.

As presented, experts were asked to indicate their level of agreement with the questions regarding the developed model and the impact analysis of change orders impact on contractor’s cash flow as per the following rating scale shown in

Table 17.

Table 18 shows the expert responses based on their level of agreement on the applicability and validation of the developed model and the impact analysis. The results demonstrated high support for the developed model and the impact analysis of change orders with a mean of (4.28). Experts were satisfied with the developed model and impact analysis. They also appreciate the fact that the developed model and impact analysis can be used to predict, evaluate and analyze the impact of change orders on contractor’s cash flow in Saudi Arabian Construction Projects.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Change orders significantly affect the cash flow of contractors and subcontractors, primarily through unforeseen cost increases, delayed payments, and project schedule changes. While numerous studies have focused on predicting cash flow in construction projects, there is a notable gap in research specifically evaluating the impact of change orders on contractors’ cash flow. This distinction is critical, as change orders can lead to additional expenses beyond initial budgets, cause lengthy delays in payment processing and approval, and result in project timeline extensions that disrupt planned cash flow patterns. The need to understand and address these specific challenges highlights the importance of this research area.

Numerous studies have revealed that a substantial portion of disputes and claims in the construction industry can be traced back to the improper handling of change orders. This issue often arises from the conflicting perspectives of contractors and project owners, frequently resulting in many critical change orders being contested through disputes and legal proceedings. These studies also highlight the need for decision-support tools that can aid contractors in accurately assessing the impact of change orders on project cash flow, an area this research aims to address. The developed The Change Order Impact Index (COII) developed in this research provides a specific and targeted approach to assessing the impacts of change orders on contractors’ cash flow. This approach differs from existing studies, which predominantly focus on predicting cash flow during the design phase or forecasting overall project financial requirements. This approach differs from existing studies, which predominantly focus on predicting cash flow during the design phase or forecasting overall project financial requirements. Previous studies have used machine learning and reinforcement learning methods to address cash flow challenges during the planning and design stages [

16,

44]. A cash flow model was developed to manage financial risks specific to construction projects [

44] and a deep reinforcement learning model was developed to optimize the resource and cash flow management in real time [

16]. Moreover, studies developed cash flow forecasting through the application of wavelet transforms and neural networks, as well as multi-series forecasting frameworks [

45,

46]. Building Information Modelling (BIM) [

47]. Cash flow is an important parameter and the actual profit of the contractor is based on its accurate calculation. A study suggests to use BIM based models to extract initial parameters like quantity take off, scheduling, and cost estimates. After which cash flow can be accurately measured using project costs incurred [

47]. Cash flow prediction accuracy was further refined by leveraging a genetic algorithm-enhanced neural network for enterprise free cash flow [

48]. These approaches primarily focus on the pre-construction or planning stages, aiming to enhance prediction and mitigate risks early in the project lifecycle.

In contrast, the COII developed in this research uniquely addresses the challenges arising during the construction phase, focusing specifically on how change orders directly impact cash flow, timing, and project costs after the project has commenced. Unlike traditional cash flow models that emphasize initial financial projections or risk forecasts, the COII provides an ongoing evaluation that captures the real-time financial consequences of change orders. This focus allows for a more nuanced understanding of the specific disruptions caused by change orders, offering a quantifiable means to assess how they affect both schedule performance and cost performance.

The COII’s use of Earned Value (EV) analysis to combine the Schedule Performance Index (SPI) and Cost Performance Index (CPI) provides a powerful visual and analytical tool for contractors. This approach enables contractors to effectively communicate with project stakeholders about the real-time impacts of change orders on both project timing and profitability, an aspect that earlier cash flow prediction models did not explicitly address. Several researchers utilized techniques like fuzzy logic, Monte Carlo simulations, and linear programming to analyze cash flow trends, they predominantly provided broad predictions [

49,

50,

51,

52]. These approaches lacked a detailed focus on how individual project changes affect financial health during the construction phase. The developed model in this study is more comprehensive, offering real-time insights into project performance, enabling contractors to proactively and reactively manage change orders, and effectively communicate the financial implications to stakeholders.

Furthermore, the COII model integrates AHP and MAUT, which allows for the assessment of both qualitative and quantitative factors, accommodating the diverse nature of data encountered during the construction phase. This integration sets it apart from previous models, which often relied on a single data type and did not address the complex interplay of various factors that affect cash flow when change orders are introduced.

By categorizing the impact of change orders into minor, moderate, significant, and severe levels, the COII provides actionable insights that support scenario analysis. This enables contractors to develop strategies to avoid financially risky periods, such as times when overdrafting occurs and interest payments amplify the financial burden. This kind of targeted scenario analysis was not covered in previous studies, which were more focused on general cash flow management rather than the specific challenges posed by change orders.

The practical implications of this research are substantial for both contractors and project owners. Contractors can use the COII to make informed decisions on whether to accept or reject a change order, depending on its projected impact on cash flow and project performance. This tool not only predicts the immediate financial impact of change orders but also supports proactive financial planning, which is crucial for avoiding disputes and ensuring smoother project execution. In comparison, earlier studies primarily aimed to forecast overall cash flow requirements without providing the detailed, scenario-based insights that COII offers, especially in response to specific project changes.

In summary, while past studies have largely concentrated on predicting cash flow at the design and planning phases using various advanced techniques, this research bridges a significant gap by focusing specifically on change orders during the construction phase. The COII model serves as both a predictive tool and a communication framework that enhances transparency and supports strategic decision-making, making it a vital addition to existing financial management tools in construction.

The study’s key findings emphasize the critical role of the Change Order Impact Index (COII) in quantifying the financial impacts of change orders on contractors’ cash flow in construction projects. By using Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Multi-Attribute Utility Theory (MAUT), the COII model effectively prioritizes and weights factors like project financing schemes, contract type, and change order characteristics. The integration with Earned Value Analysis (EVA) further enhances its practical application, enabling contractors to assess both cost and schedule impacts in real-time. These findings underscore the COII’s importance as a proactive financial tool, particularly relevant for large-scale projects in Saudi Arabia, where change orders frequently disrupt cash flow. The model offers contractors a structured approach to manage risks, improving financial stability and supporting more informed decision-making.

Although the developed COII is intended for large-scale projects, it can also be used for small to medium-sized projects. The COII model can be adapted by modifying the factors considered and simplifying the analysis to accommodate less complex project environments. While the comprehensive approach of COII is especially valuable for managing the complexities of larger projects, simpler and more direct tools might suffice for smaller projects. Nonetheless, the model remains flexible and can be scaled according to the specific requirements of different project types and sizes. Although, the COII model, is developed for the Saudi Arabian construction context, it can be modified to accommodate other countries’ rules and regulations, as well as different industries. Adapting the model would require consideration of variations in legal frameworks, contract types, and cultural factors. Regulatory differences can affect the financial impact of change orders, requiring adjustments to model parameters. Additionally, the prevalence of certain contract types, such as lump-sum or cost-plus, may vary, influencing the weights and utility values used. Cultural differences in risk management and negotiation styles may also necessitate recalibrating utility scores. Addressing these factors would enhance the model’s adaptability and effectiveness in diverse contexts. The developed COII model could be enhanced by incorporating more precise data and advanced artificial intelligence techniques if such data becomes available. The AHP-MAUT framework was selected for this study due to its flexibility in accommodating combined data sources, including expert-based inputs, making it well-suited to the available information.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Naji K, Gunduz M, Naser A. The Effect of Change-Order Management Factors on Construction Project Success: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. J Constr Eng Manag 2022;148. [CrossRef]

- Demiss B, Elsaigh W. Application of novel hybrid deep learning architectures combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN): construction duration estimates prediction considering preconstruction uncertainties. Engineering Research Express 2024;6:032102. [CrossRef]

- Heravi G, Charkhakan M. Predicting Change by Evaluating the Change Implementation Process in Construction Projects Using Event Tree Analysis. Journal of Management in Engineering 2015;31. [CrossRef]

- Alkhalifah S, Tuffaha F, Al Hadidi L, Ghaithan A. Factors influencing change orders in oil and gas construction projects in Saudi Arabia. Built Environment Project and Asset Management 2023;13:430–52. [CrossRef]

- Zangana H, Bazeed S, Ali N, Abdullah D. Navigating Project Change: A Comprehensive Review of Change Management Strategies and Practices. Indonesian Journal of Education and Social Sciences 2024;3:166–79. [CrossRef]

- Tarawneh S, Almahmoud AF, Hajjeh H. Impact of cash flow variation on project performance: contractors’ perspective. Engineering Management in Production and Services 2023;15:73–85. [CrossRef]

- Koopman K, Cumberlege R. Cash flow management by contractors. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2021;654:012028. [CrossRef]

- Purnus A, Bodea C-N. Financial Management of the Construction Projects: A Proposed Cash Flow Analysis Model at Project Portfolio Level. Organization, Technology & Management in Construction: An International Journal 2015;7:1217–27. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud H, Ahmed V, Beheiry S. Construction Cash Flow Risk Index. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2021;14:269. [CrossRef]

- Alashwal AM, Chew MY. Simulation techniques for cost management and performance in construction projects in Malaysia. Built Environment Project and Asset Management 2017;7:534–45. [CrossRef]

- Alzara M. Exploring the Impacts of Change Orders on Performance of Construction Projects in Saudi Arabia. Advances in Civil Engineering 2022;2022. [CrossRef]

- Alajmi AM, Ahmed Memon Z. A Review on Significant Factors Causing Delays in Saudi Arabia Construction Projects. Smart Cities 2022;5:1465–87. [CrossRef]

- Shash A, Qarra A Al. Cash Flow Management of Construction Projects in Saudi Arabia. Project Management Journal 2018;49:48–63. [CrossRef]

- Abdulghafour A, Salman K. Delays of construction projects in Makkah from the point of view of the consultant. Journal of Umm Al-Qura University for Engineering and Architecture 2023;14:122–34. [CrossRef]

- Alkhattabi L, Alkhard A, Gouda A. Effects of change orders on the budget of the public sector construction projects in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Results in Engineering 2023;20:101628. [CrossRef]

- Jiang C, Li X, Lin J-R, Liu M, Ma Z. Adaptive control of resource flow to optimize construction work and cash flow via online deep reinforcement learning. Autom Constr 2023;150:104817. [CrossRef]

- Xiao H, Proverbs D. Factors influencing contractor performance: an international investigation. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2003;10:322–32. [CrossRef]

- Adejoh A, Asebiomo M, Ogunbode E, Oyewobi L, Sani M, Isa R, et al. Influence of Contractor Selection Criteria on Critical Success Factors of Public Project Delivery in Abuja. Environmental Technology and Science Journal 2023;13:86–98. [CrossRef]

- Zamim S. Identification of crucial performance measurement factors affecting construction projects in Iraq during the implementation phase. Cogent Eng 2021;8. [CrossRef]

- Jahangoshai Rezaee M, Yousefi S, Chakrabortty R. Analysing causal relationships between delay factors in construction projects. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 2021;14:412–44. [CrossRef]

- Gunduz M, Mohammad K. Assessment of change order impact factors on construction project performance using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Technological and Economic Development of Economy 2019;26:71–85. [CrossRef]

- Omopariola E, Windapo A, Edwards D, Aigbavboa C, Yakubu SU-N, Obari O. Modelling the domino effect of advance payment system on project cash flow and organisational performance. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2023;31:59–78. [CrossRef]

- Chadee A, Ali H, Gallage S, Rathnayake U. Modelling the Implications of Delayed Payments on Contractors’ Cashflows on Infrastructure Projects. Civil Engineering Journal 2023;9:52–71. [CrossRef]

- Bissoon S, Outridge D. Delayed payments impacts on planned cash flow of small and medium contractors for a special purpose company. Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering & Technology (IConETech-2020), Faculty of Engineering, The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine; 2020, p. 313–24. [CrossRef]

- Cui Q, Hastak M, Halpin D. Systems analysis of project cash flow management strategies. Construction Management and Economics 2010;28:361–76. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y, Skibniewski M. Cash and Claim: Data-Based Inverse Relationships between Liquidity and Claims in the Construction Industry. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction 2020;12. [CrossRef]

- Chiang Y, Cheng EWL. Construction loans and industry development: the case of Hong Kong. Construction Management and Economics 2010;28:959–69. [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Lee H-S, Park M. Contractor Liquidity Evaluation Model for Successful Public Housing Projects. J Constr Eng Manag 2018;144. [CrossRef]

- El-adaway I, Fawzy S, Burrell H, Akroush N. Studying Payment Provisions under National and International Standard Forms of Contracts. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction 2017;9. [CrossRef]

- hyari khaled hesham. Payment procedures under FIDIC construction contract. Proceedings of International Structural Engineering and Construction 2022;9. [CrossRef]

- Roja Z, Kalkis H, Roja I, Zalkalns J, Sloka B. Work strain predictors in construction work. Agronomy Research 2017;15. [CrossRef]

- Marulanda A, Neuenschwander M. Contractual time for completion adjustment in the FIDIC Emerald Book. Tunnels and Underground Cities: Engineering and Innovation meet Archaeology, Architecture and Art, CRC Press; 2019, p. 4494–500. [CrossRef]

- Moselhi O, Assem I, El-Rayes K. Change Orders Impact on Labor Productivity. J Constr Eng Manag 2005;131:354–9. [CrossRef]

- Choi K, Lee HW, Bae J, Bilbo D. Time-Cost Performance Effect of Change Orders from Accelerated Contract Provisions. J Constr Eng Manag 2016;142. [CrossRef]

- Khuder S, Ibrahim A, Eedan O. Adopting a Method for Calculating the Impact of Change Orders on the Time it Takes to Complete Bridge Projects. Iraqi Journal of Civil Engineering 2022;15:52–8. [CrossRef]

- Dabirian S, Ahmadi M, Abbaspour S. Analyzing the impact of financial policies on construction projects performance using system dynamics. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2023;30:1201–21. [CrossRef]

- Omopariola E, Windapo A, Edwards D, Chileshe N. Attributes and impact of advance payment system on cash flow, project and organisational performance. Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction 2022;27:306–22. [CrossRef]

- Ismaeil E, Sobaih A. A Proposed Model for Variation Order Management in Construction Projects. Buildings 2024;14:726. [CrossRef]

- Mofleh Alshehhi HS. The impact of risk management on the performance of construction projects. 2024: Proceedings of Social Science and Humanities Research Association (SSHRA), Global Research & Development Services; 2024, p. 114–5. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y. Risk Analysis and Research for Construction Projects. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences 2023;19:181–7. [CrossRef]

- Oladapo AA. A quantitative assessment of the cost and time impact of variation orders on construction projects. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology 2007;5. [CrossRef]

- Al Maamari A, Khan F. Evaluating the Causes and Impact of Change Orders on Construction Projects Performance in Oman. International Journal of Research in Entrepreneurship & Business Studies 2021;2:41–50. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Yuan H. Factors affecting contractors’ risk attitudes in construction projects: Case study from China. International Journal of Project Management 2011;29:209–19. [CrossRef]

- Zayed T, Liu Y. Cash flow modeling for Construction projects. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2014;21. [CrossRef]

- Söylen Z, Mammadova F, Fasounaki M, Özmen Aİ, İnce G. Cash Flow Forecasting Based on Wavelet Transform and Neural Networks. 2023 8th International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK), IEEE; 2023, p. 306–11. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Y, Tu K. A Robust Forecasting Framework for Multi-Series Cash Flow Prediction. 2023 6th International Conference on Information Communication and Signal Processing (ICICSP), IEEE; 2023, p. 898–902. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Grobler F. Preparing a Construction Cash Flow Analysis Using Building Information Modeling (BIM) Technology. Journal of Construction Engineering and Project Management 2013;3:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Yan M, Bai L. Prediction of Enterprise Free Cash Flow Based on a Backpropagation Neural Network Model of the Improved Genetic Algorithm. Information (Switzerland) 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Taylan O, Bafail AO, Abdulaal RMS, Kabli MR. Construction projects selection and risk assessment by fuzzy AHP and fuzzy TOPSIS methodologies. Appl Soft Comput 2014;17:105–16. [CrossRef]

- Cheng M-Y, Hoang N-D, Wu Y-W. Cash flow prediction for construction project using a novel adaptive time-dependent least squares support vector machine inference model. Journal of Civil Engineering and Management 2015;21:679–88. [CrossRef]

- Peleskei C, Dorca V, Munteanu R, Munteanu R. Risk Consideration and Cost Estimation in Construction Projects Using Monte Carlo Simulation. Management (18544223) 2015;10.

- Barbosa P, Pimentel P. A linear programming model for cash flow management in the Brazilian construction industry. Construction Management and Economics 2001;19:469–79. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Research Stages.

Figure 1.

Research Stages.

Figure 2.

Change Order Impact Index Model Development.

Figure 2.

Change Order Impact Index Model Development.

Figure 3.

Factors and Subfactors For COII.

Figure 3.

Factors and Subfactors For COII.

Figure 4.

Type of Respondents’ Organization and Job Position.

Figure 4.

Type of Respondents’ Organization and Job Position.

Figure 5.

Academic Qualifications and Years of Experience.

Figure 5.

Academic Qualifications and Years of Experience.

Figure 6.

Respondents Previous Experience.

Figure 6.

Respondents Previous Experience.

Figure 7.

Change Order Impact Analysis.

Figure 7.

Change Order Impact Analysis.

Figure 8.

Change Order Timing and Value Impact with Overdraft.

Figure 8.

Change Order Timing and Value Impact with Overdraft.

Figure 9.

Change Order Impact on Project Payments.

Figure 9.

Change Order Impact on Project Payments.

Figure 10.

EV for Different Change Order Impacts for different Scenarios.

Figure 10.

EV for Different Change Order Impacts for different Scenarios.

Table 1.

Utility Attributes for Different Factors.

Table 1.

Utility Attributes for Different Factors.

| Main Factors |

Subfactors |

Attributes |

| Project Financing Schemes |

Cash Availability |

Cash is available |

| % Cash Available and % Bank Loans |

| Bank Loans |

| Loan Limit Achieved |

| Owner’s Payments |

Extremely Delays |

| Moderately Delays |

| No Delays |

| Contract Type |

Unit Price |

| Lump Sum |

| Cost Plus a Fixed Fee |

| Cost Plus Percentage of Cost |

| Guaranteed Maximum Price |

| Target Price Plus a Fee |

| Characteristics and Nature of Change Order |

Value Of Change Order |

>0% ≤5% |

| >5% ≤10% |

| > 10% ≤15% |

| >15% ≤20% |

| >20% |

| Timing of Change Order |

<0% (Before construction) |

| >0% ≤25% |

| > 25% ≤50% |

| >50% ≤75% |

| >75% ≤100% |

| Extension of Time |

Extremely Sufficient |

| Sufficient |

| Moderately Sufficient |

| Not Sufficient |

| Work Stoppage |

Stoppage |

| No Stoppage |

| Type of Work |

Addition |

| Omission |

| Rework |

Table 2.

Breakdown details of the research sample.

Table 2.

Breakdown details of the research sample.

Type of

Participants |

No. of Forms Send |

No. of Forms

Responded to |

% of

Responding |

% Out of 52 Returned Forms of Response |

| Arbitrators |

8 |

4 |

50 |

8 |

| Consultants |

40 |

16 |

40 |

31 |

| Contractors |

60 |

27 |

45 |

52 |

| Project Managers |

12 |

5 |

42 |

9 |

| Total |

120 |

52 |

43 |

100 |

Table 3.

Relative Weights for Factors and Subfactors.

Table 3.

Relative Weights for Factors and Subfactors.

| Main Factors |

Subfactors |

Level 1

(W1) |

Level 2

(W2) |

Final Weight

(W1 × W2) |

| Project Financing Schemes |

Cash Availability |

0.44 |

0.56 |

0.246 |

| Owner’s Payments |

0.44 |

0.194 |

| Contract Type |

--------- |

0.30 |

1 |

0.3 |

| Characteristics and Nature of Change Order |

Value of Change Order |

0.26 |

0.30 |

0.078 |

| Timing of Change Order |

0.22 |

0.057 |

| Extension of Time |

0.15 |

0.039 |

| Work Stoppage |

0.28 |

0.073 |

| Type of Work |

0.05 |

0.013 |

Table 4.

Cronbach’s Alpha and Its Interpretation.

Table 4.

Cronbach’s Alpha and Its Interpretation.

| Cronbach’s Alpha |

Interpretation |

| 0.9 and greater |

High Reliability |

| 0.8–0.89 |

Good Reliability |

| 0.7–0.79 |

Acceptable Reliability |

| 0.65–0.69 |

Marginal Reliability |

| 0.5–0.64 |

Minimal Reliability |

Table 5.

Reliability of Main Factors.

Table 5.

Reliability of Main Factors.

| Main and Subfactors |

Reliability |

| Project Financing Schemes |

0.91 |

| Contract Type |

0.82 |

| Characteristics and Nature of Change Order |

0.88 |

Table 6.

Reliability of Subfactors.

Table 6.

Reliability of Subfactors.

| Subfactor Attributes |

Reliability |

| Cash Availability Attributes |

0.89 |

| Owner’s Payments Attributes |

0.87 |

| Contract Type Attributes |

0.81 |

| Value of Change Order Attributes |

0.85 |

| Timing of Change Order Attributes |

0.91 |

| Extension of Time Attributes |

0.86 |

| Work Stoppage Attributes |

0.75 |

| Type of Work Attributes |

0.79 |

Table 7.

Utility Score and Interpretation for Cash Availability Subfactor.

Table 7.

Utility Score and Interpretation for Cash Availability Subfactor.

| Utility |

Score |

Score Interpretation |

| Cash is Available |

1 |

High cash availability positively impacts cash flow, allowing easy financial management and investment in new projects. |

| % Cash Available |

2 |

The impact depends on the total cash pool; higher percentages are generally positive but less beneficial if the total is small. |

| Bank Loans |

3 |

Bank loans are a common business practice but imply future cash outflows for repayments, potentially affecting cash flow. |

| % Bank Loans |

4 |

High reliance on bank loans indicates potential cash flow stress and adds interest costs, negatively impacting cash flow. |

| Loan Limit Achieved |

5 |

Reaching the loan limit suggests a critical cash flow situation, severely limiting financial flexibility and response capability. |

Table 8.

Owners Payment Status and Its Impact Utility Values Interpretations.

Table 8.

Owners Payment Status and Its Impact Utility Values Interpretations.

| Payment Status |

Score |

Interpretation of Impact on Contractor’s Cash Flow |

| No Delays |

1 |

Minimal impact with on-time payments ensuring steady cash flow. |

| Minor Delays |

2 |

Low impact due to slight delays within permissible FIDIC limits. |

| Moderate Delays |

3 |

Moderate impact, necessitating short-term financial adjustments. |

| Significant Delays |

4 |

High impact with considerable delays causing substantial strain. |

| Extreme Delays |

5 |

Critical impact, severe delays leading to legal disputes and financial distress. |

Table 9.

Contract Type Utility Scores and Impact Interpretation.

Table 9.

Contract Type Utility Scores and Impact Interpretation.

| Contract Type |

Score |

Impact Interpretation on Contractor Cash Flow |

| Cost Plus a Fixed Fee |

1 |

Offers financial stability by covering all costs plus a fixed fee, minimizing unexpected financial risks. |

| Unit Price |

2 |

Provides flexibility and incentives for cost efficiency but carries some risk with inaccurate cost estimations. |

| Target Price Plus a Fee |

2 |

Incentivizes meeting or under-running target costs, with financial risk if targets are not met. |

| Lump Sum |

3 |

Ensures payment certainty but includes the risk of bearing cost overruns within certain limits. |

| Guaranteed Maximum Price |

3 |

Limits cost exposure, but the contractor bears the risk of overruns up to the maximum price. |

| Cost Plus Percentage of Cost |

4 |

Covers all costs but may lead to inefficiencies and lower profit margins due to lack of strong cost-control incentives. |

| (Hypothetical High-Risk Contract) |

5 |

Represents a high-risk scenario where the contractor bears major unforeseen costs or substantial penalties. |

Table 10.

Change Order Value and Score Interpretations.

Table 10.

Change Order Value and Score Interpretations.

| Change Order Value |

Score |

Interpretation Impact on Contractor’s Cash Flow |

| >0% to ≤5% |

1 |

Minimal impact, likely manageable within the initial budget as per Clause 13.1. |

| >5% to ≤10% |

2 |

Moderate impact, with transparency and negotiation options as outlined in Clauses 13.3 and 13.4. |

| >10% to ≤15% |

3 |

Noticeable impact, involving negotiation and potential delays, as per Clauses 52.3 and 14.1. |

| >15% to ≤20% |

4 |

Substantial disruption, with complex compensation claims and potential for contract termination, as per Clauses 14.2 and 20.1. |

| >20% |

5 |

Severely impactful, indicating drastic changes that may require contract renegotiation or legal recourse. |

Table 11.

Change Order Time Impact on the Contractor’s Cash Flow.

Table 11.

Change Order Time Impact on the Contractor’s Cash Flow.

| Change Order Timing |

Score |

Detailed Impact Interpretation |

| Before construction (Completion <0%) |

1 |

Minimal Impact: Changes can be integrated with minimal adjustments to planning and budgeting, resulting in negligible financial disruption. |

| Completion between 0% and 25% |

2 |

Low Impact: Early-stage changes generally require minor modifications to the project plan and budget, causing low financial strain. |

| Completion between 25% and 50% |

3 |

Moderate Impact: Mid-project changes necessitate notable adjustments in resource allocation and may lead to moderate financial and scheduling challenges. |

| Completion between 50% and 75% |

4 |

High Impact: Changes in this advanced stage can cause significant project disruptions, leading to considerable cost overruns and potential delays, heavily impacting cash flow. |

| Completion between 75% and 100% |

5 |

Maximum Impact: Late-stage changes typically result in substantial disruptions, severe cost overruns, and extensive delays, severely affecting the contractor’s cash flow and possibly the project’s viability. |

Table 12.

Time Extension Impact Score and Its Interpretation.

Table 12.

Time Extension Impact Score and Its Interpretation.

| Time Extension |

Score |

Interpretation of Impact on Contractor’s Cash Flow |

| Extremely Sufficient |

1 |

Least Impact: Minimal or no negative impact on cash flow, efficient resource management, potential cost savings. |

| Sufficient |

2 |

Low Impact: Adequate additional time for comfortable resource adjustment, manageable impacts on financial health. |

| Moderately Sufficient |

3 |

Moderate Impact: Some relief with noticeable impact; partial offset of financial challenges. |

| Not Sufficient |

4 |

High Impact: Inadequate extra time for significant mitigation, leading to considerable financial strain. |

| Critically Insufficient |

5 |

Greatest Impact: Severely insufficient time extension, causing substantial financial difficulties and potentially jeopardizing project viability. |

Table 13.

Addition Omission and Rework Impact Interpretations.

Table 13.

Addition Omission and Rework Impact Interpretations.

| Action |

Score |

Interpretation of Impact on Contractor’s Cash Flow |

| Addition |

|

|

| |

1 |

Full coverage by budget or client funds, no financial strain. |

| |

2 |

Slight increase in scope, minimal financial strain. |

| |

3 |

Noticeable extension in scope, moderate budget adjustments and cash flow challenges. |

| |

4 |

Significant scope extension, major budget overruns and cash flow issues. |

| |

5 |

Drastic scope change, severe budget and cash flow crises. |

| Omission |

|

|

| |

1 |

No financial loss, possible reduction in project costs without affecting profitability. |

| |

2 |

Minor reduction in project scope, slight positive or neutral effect on cash flow. |

| |

3 |

Moderate reduction in scope, impacting profitability but not critically. |

| |

4 |

Large-scale scope reduction, negatively impacting profitability and cash flow. |

| |

5 |

Substantial scope reduction, severely affecting financial viability. |

| Rework |

|

|

| |

1 |

Minor rework with negligible cost implications, no disruption to timeline. |

| |

2 |

Small amount of extra work, slightly impacting budget and schedule. |

| |

3 |

Significant rework, additional time and resources needed, affecting schedule and budget. |

| |

4 |

Extensive rework leading to major delays and cost overruns, significantly affecting financial health. |

| |

5 |

Critical rework necessitating extensive additional work, causing major project delays and budget crises. |

Table 14.

Work Stoppage Impact Interpretations on Contractor’s Cash Flow.

Table 14.

Work Stoppage Impact Interpretations on Contractor’s Cash Flow.

| Stoppage Level |

Score |

Impact on Contractor’s Cash Flow |

| No Stoppage |

1 |

Minimal impact; cash flow remains stable due to uninterrupted progress. |

| Minor Stoppage |

2 |

Slight disruption, but generally manageable within the project’s financial structure. |

| Moderate Stoppage |

3 |

Noticeable impact, necessitating financial adjustments and careful project management. |

| Significant Stoppage |

4 |

Major disruptions leading to substantial financial strain and requiring strategic handling. |

| Severe Stoppage |

5 |

Critical impact, potentially leading to serious financial challenges and project instability. |

Table 15.

Change Order Impact Index (COII) Scale and Interpretations.

Table 15.

Change Order Impact Index (COII) Scale and Interpretations.

| COII Numerical Value |

COII Linguistic |

Interpretations |

| ≥1 COII <2 |

Minor Impact |

The change order will have positive or no impact on the project cash flow. |

| ≥2 COII <3 |

Moderate Impact |

The change order might affect the project cash flow negatively. However, before claiming, perform impact analysis. |

| ≥3 COII <4 |

Significant Impact |

The change order will affect the project cash flow significantly. However, its impact should be analyzed. |

| ≥4 COII ≤5 |

Severe Impact |

The change order would affect the project cash flow severely. However, it needs to be claimed with thorough impact analysis. |

Table 16.

Scale Mean Values Classification.

Table 16.

Scale Mean Values Classification.

| Index |

<2.5 |

2.5–3.49 |

3.5–5 |

| Classification |

Weak |

Moderate |

High |

Table 17.

Rating Scale of Experts Evaluation.

Table 17.

Rating Scale of Experts Evaluation.

| Level of Agreement |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Moderately Agree |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

| Rating Scale |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

Table 18.

Frequencies of Experts Responses, Mean, Percentage and Classification for Developed Model and Impact Analysis.

Table 18.