Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.2. Area of Study

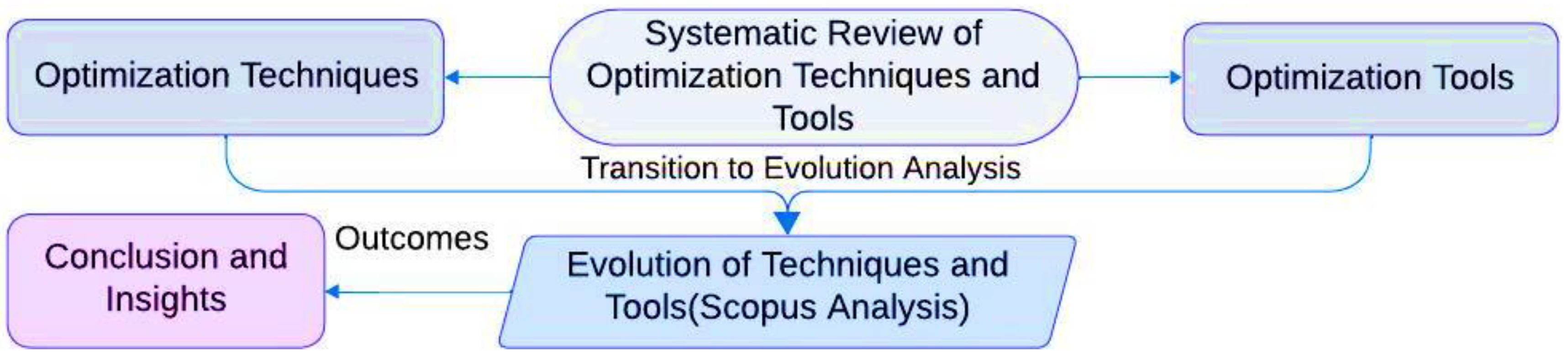

2. Systematic Review of OT and ST

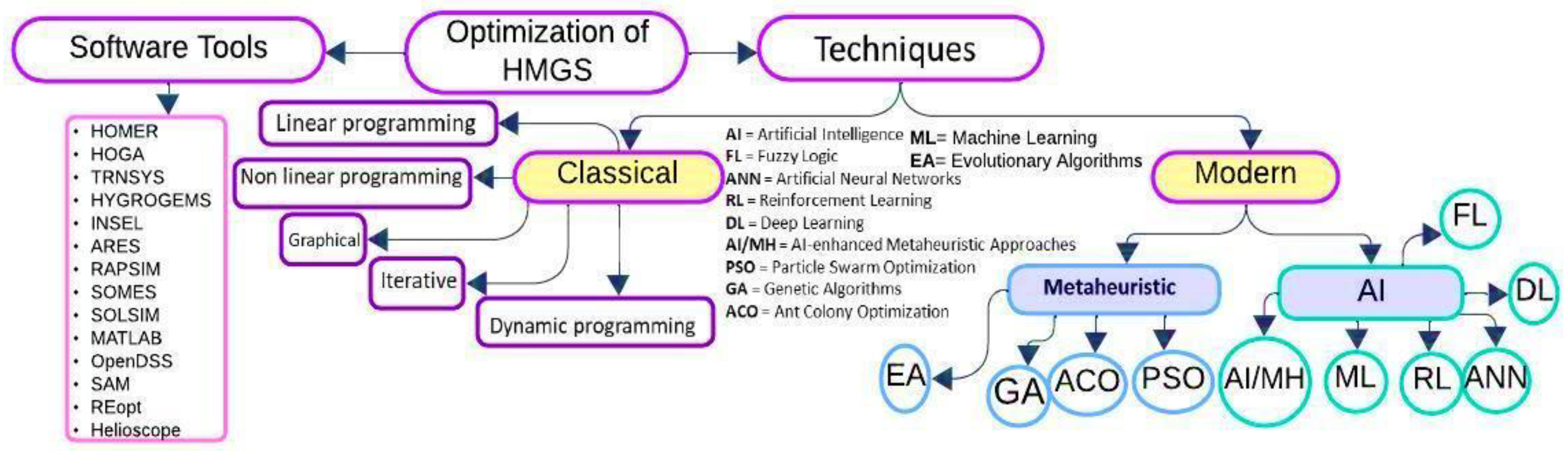

2.1. Optimization Techniques

2.1.1. Classical Techniques

2.1.2. Modern Optimization

- AI in HMGS Optimization:

- Reinforcement Learning:

- Fuzzy Logic:

- Deep Learning:

- Artificial Neural Networks:

- AI-enhanced Metaheuristic (AI/MH):

- b. Metaheuristic techniques in HMGS Optimization:

- Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): PSO is a metaheuristic that seeks solutions by optimizing particle placements based on natural social behavior. PSO is commonly used to assess HMGS, as indicated by its inclusion in several researches. For example, ref [37] identifies optimum system topologies and component sizes while considering dependability, cost, and environmental effect, and for enhancing energy management systems in MGs with optimized artificial networks for improved performance and renewable integration as illustrated in reference [38]. Furthermore, ref. [39] emphasizes PSO's application in designing and optimizing a smart DC MG's multi-objective function for a HMGS of SPV, WT, and biogas-based IC engine generators, with the goal of maximizing power availability while lowering costs, demonstrating PSO's superior performance in cost reduction and high availability when compared to other algorithms.

- Genetic Algorithm (GA): is a metaheuristic inspired by natural selection that use selection, crossover, and mutation to develop solutions toward optimality, has been widely utilized in various studies to evolve candidate solutions towards optimality. For example, in ref. [40], GA improves HMGSs in order to reduce energy production costs while increasing dependability and environmental advantages. Ref. [41] demonstrates GA's use in designing energy management systems for MGs, with an emphasis on maximizing profit from energy exchanges and minimizing system complexity for improved smart grid integration. Another application of GA, as detailed in ref. [42], is optimizing a hybrid SPV/WT, addressing the loss of load probability (LLP) and system cost by selecting optimal capacities for the SPV array, wind turbine, and battery, optimizing the SPV array tilt angle, and determining the ideal inverter size, demonstrating GA's versatility in addressing complex optimization challenges in HMGSs.

- Ant Colony Optimization (ACO): is a metaheuristic inspired by ant foraging behavior that efficiently solves discrete optimization problems such as routing and scheduling. ACO shows adaptability in HMGS optimization across several studies: Ref. [43]investigates the use of ACO for supervisory control in alternative energy distributed generation MGs, aiming to improve dispatch management while taking environmental and economic factors into account. Ref. [44] uses ACO for maximum power point tracking (MPPT) to enhance power quality in islanded MGs by optimizing HRESs units. Lastly, Ref. [45] applies ACO to energy management system (EMS) in MGs, concentrating on cost-efficient scheduling and demonstrating significant cost savings over standard EMS and PSO approaches, demonstrating ACO's efficiency in complicated, multi-objective optimization tasks inside HMGS.

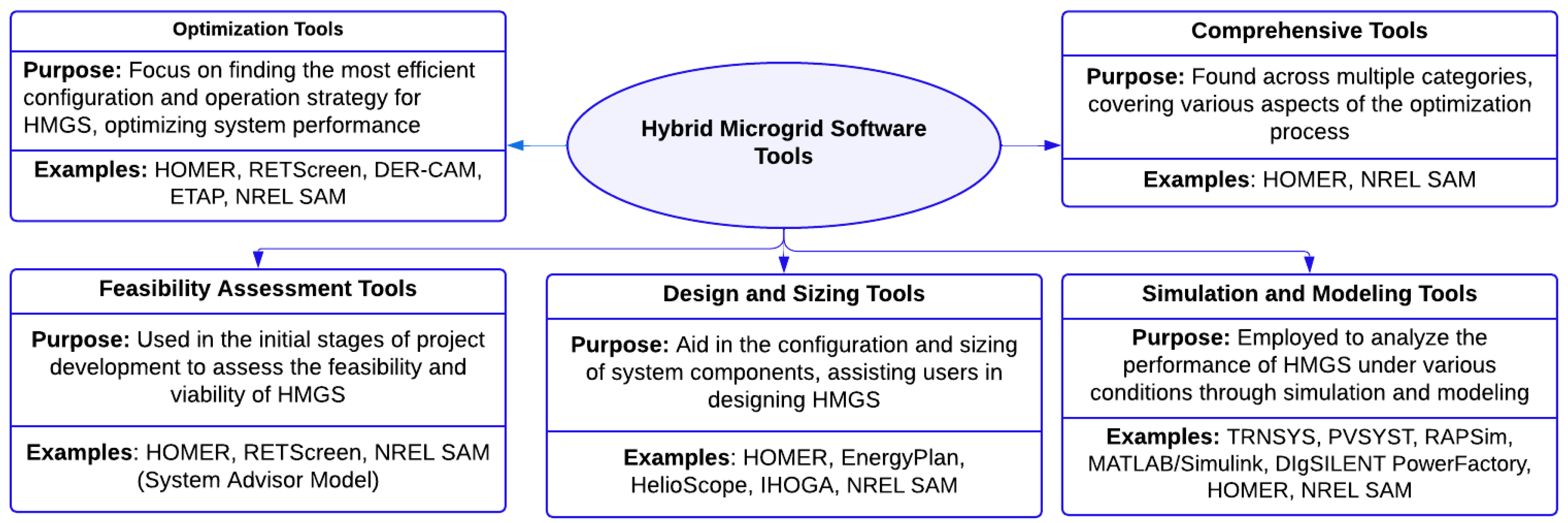

2.2. ST for HMGS Optimization

- Feasibility Assessment Tools: Used in the initial stages to assess the viability and potential of HMGS designs.

- Design and Sizing Tools: Aid in configuring and sizing system components to ensure they meet design requirements.

- Simulation and Modeling Tools: Analyze system performance under various conditions and predict behavior during operation.

- Optimization Tools: Focus on improving the system's performance by finding the most cost-effective and energy-efficient operational strategies.

- Comprehensive Tools: Integrate multiple functions, offering a holistic approach to designing, simulating, and optimizing HMGSs.

- Net Present Cost (NPC): Evaluates total lifetime costs, including installation, maintenance, and operational expenses, providing a comprehensive assessment of overall costs.

- Net Present Value (NPV): Assesses the profitability of a system by comparing the present values of costs and revenues, helping to determine the project’s economic feasibility.

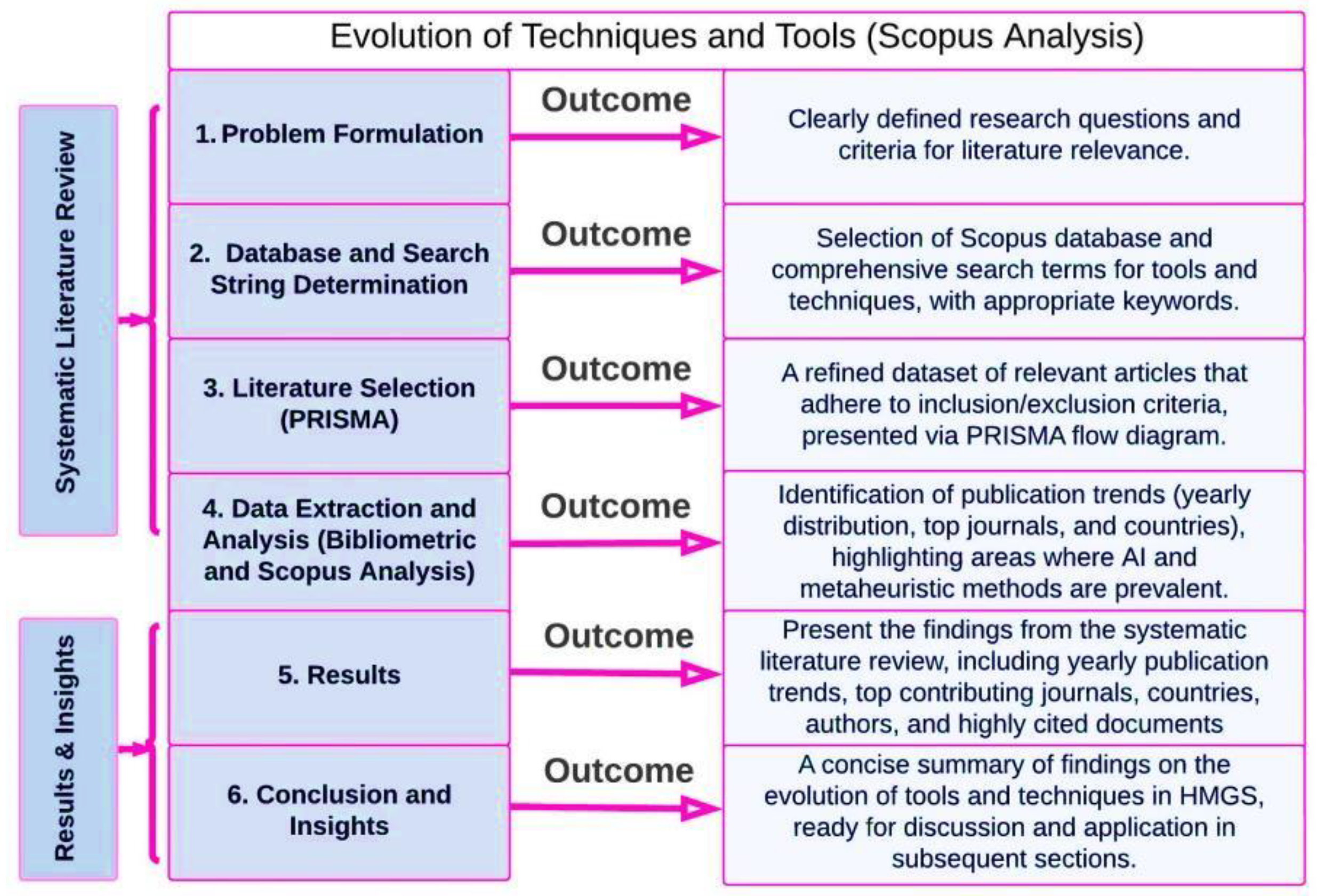

3. Evolution of Techniques and Tools (Scopus Analysis)

- Defined research questions and objectives.

- Established criteria for selecting relevant literature.

- Outlined potential conclusions based on findings.

- Selected Scopus as the primary database.

- Identified relevant keywords to ensure a comprehensive search.

- Developed a focused search string aligned with the study’s objectives.

- Applied the PRISMA methodology to screen and select relevant articles.

- Excluded unrelated studies, books, and non-English publications.

- Extracted insights from selected studies.

- Analyzed trends, gaps, and emerging areas of focus in the field.

4. Systematic Review Framework and Results

4.1. Problem Formulation

4.2. Database and Search String Determination

4.2.a. OT

4.2.b. ST

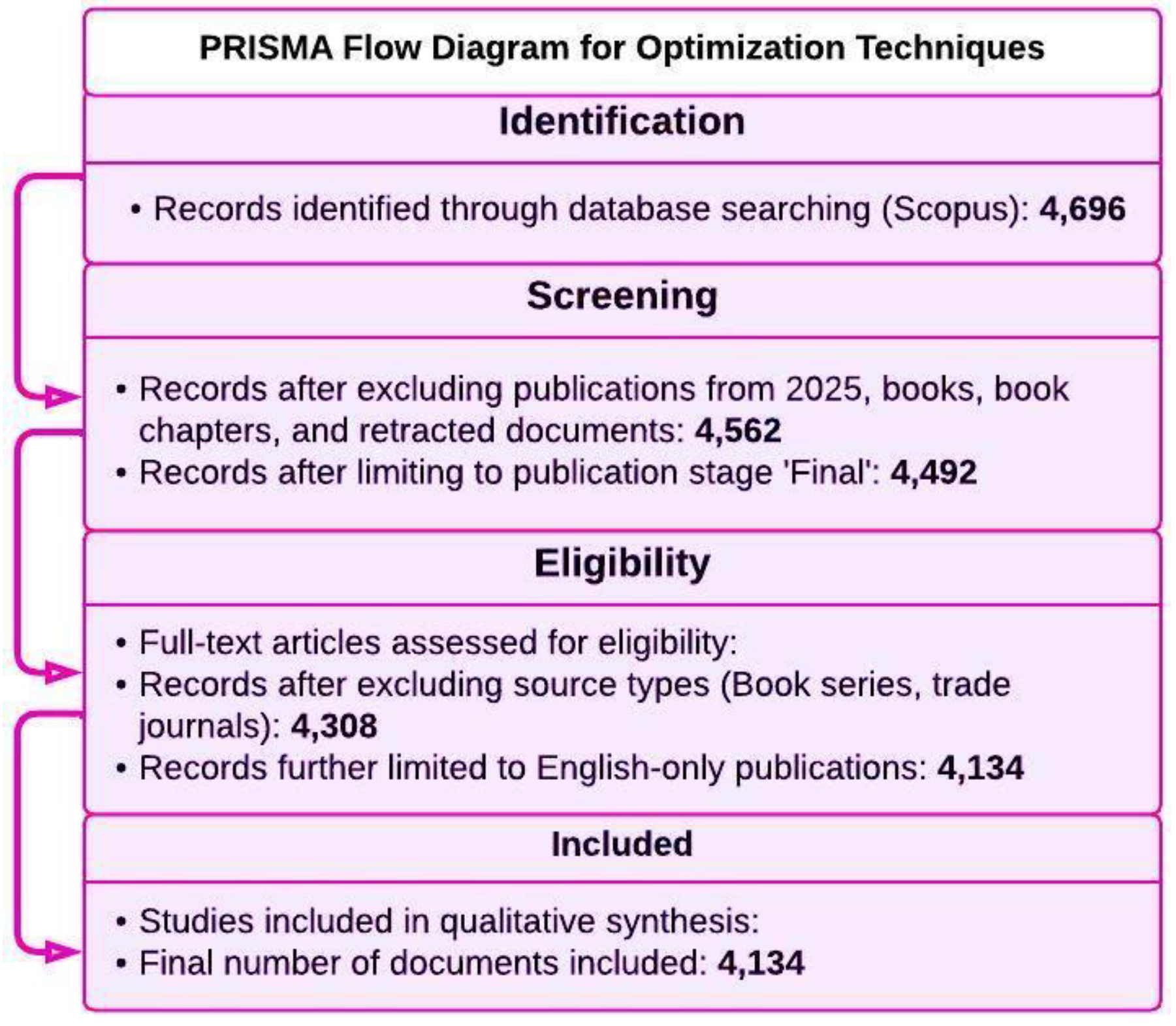

4.3. Literature Selection (PRISMA Analysis)

4.3.a. Optimization Techniques

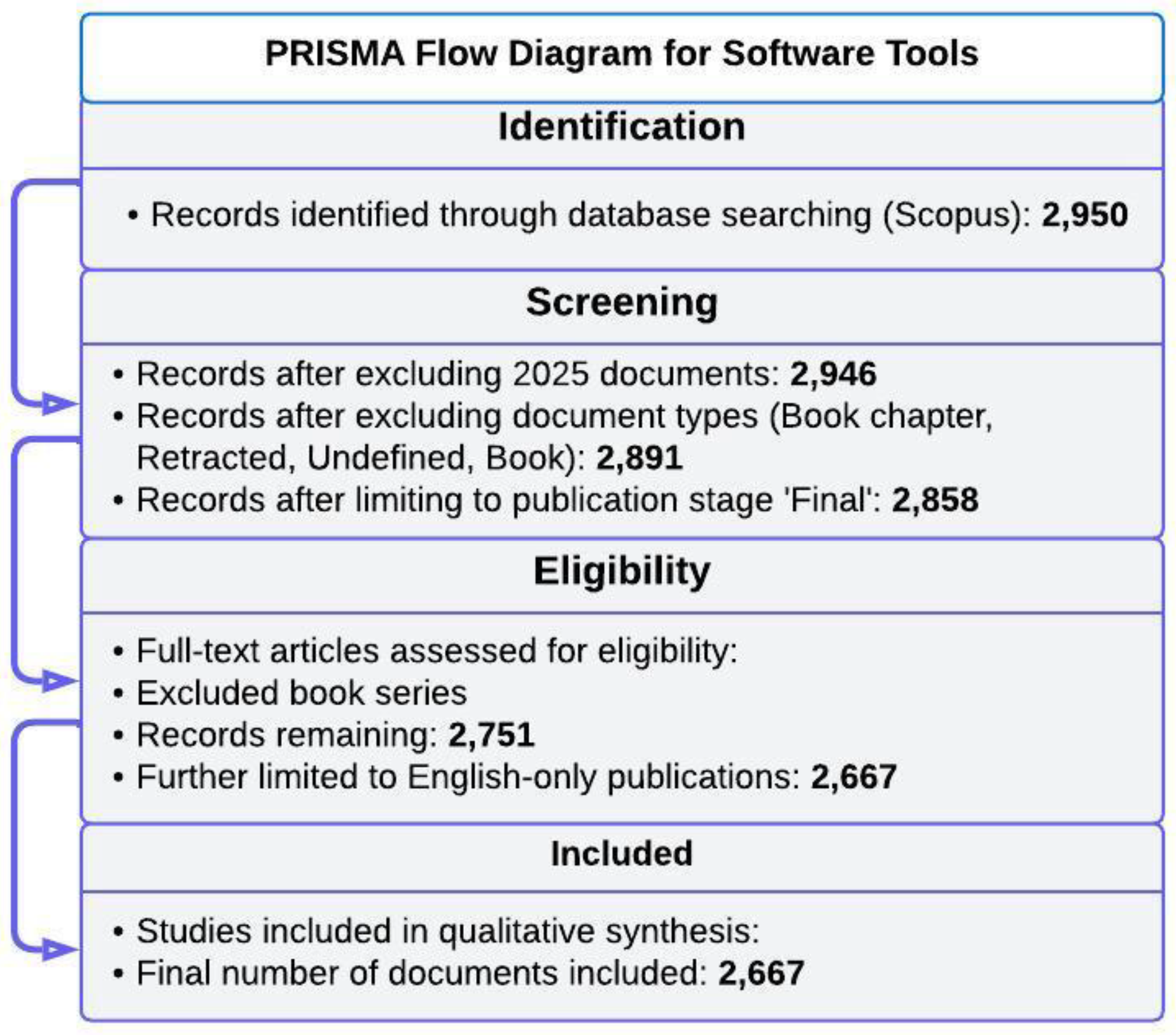

4.3.b. ST

5. Results

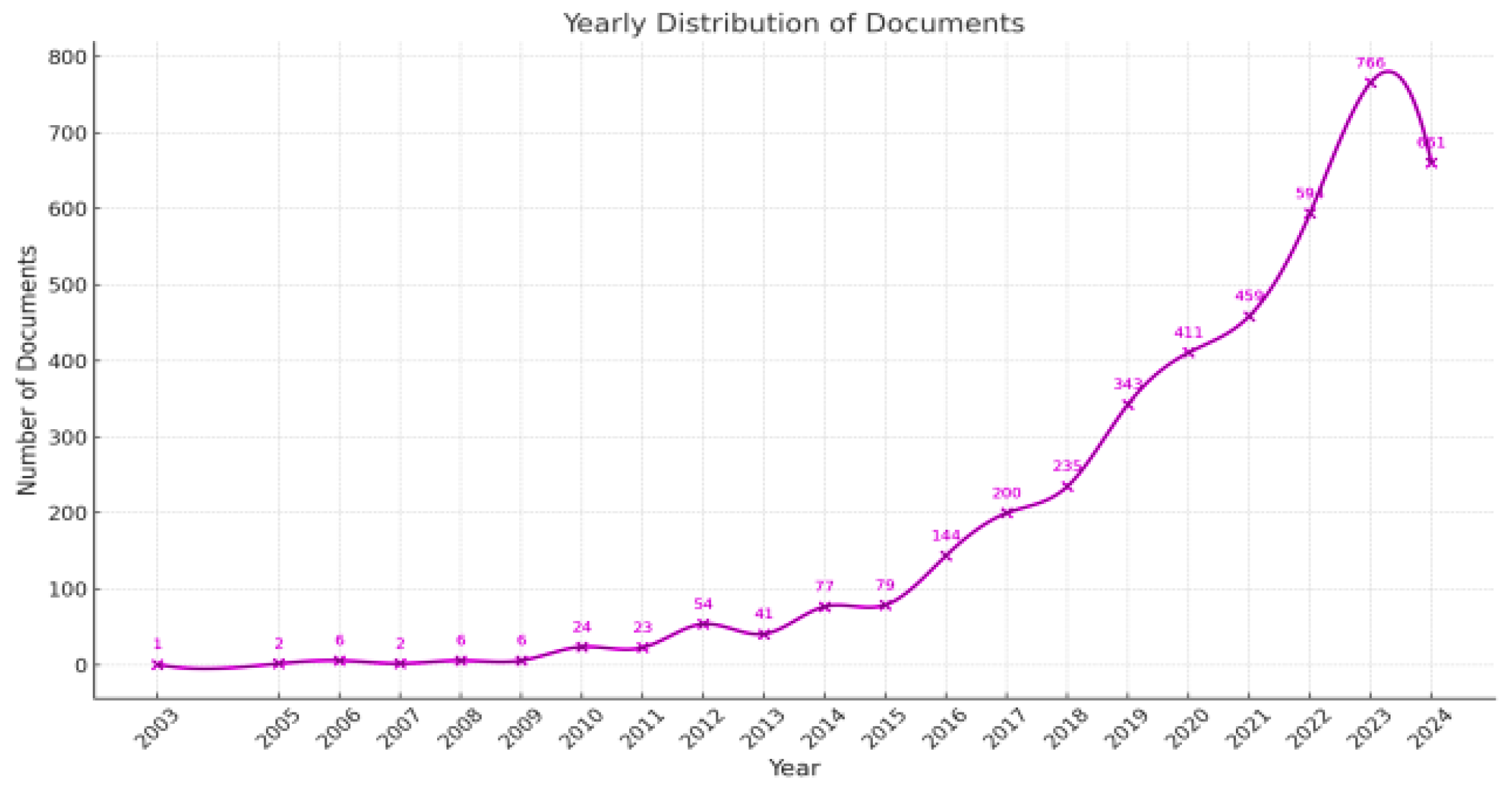

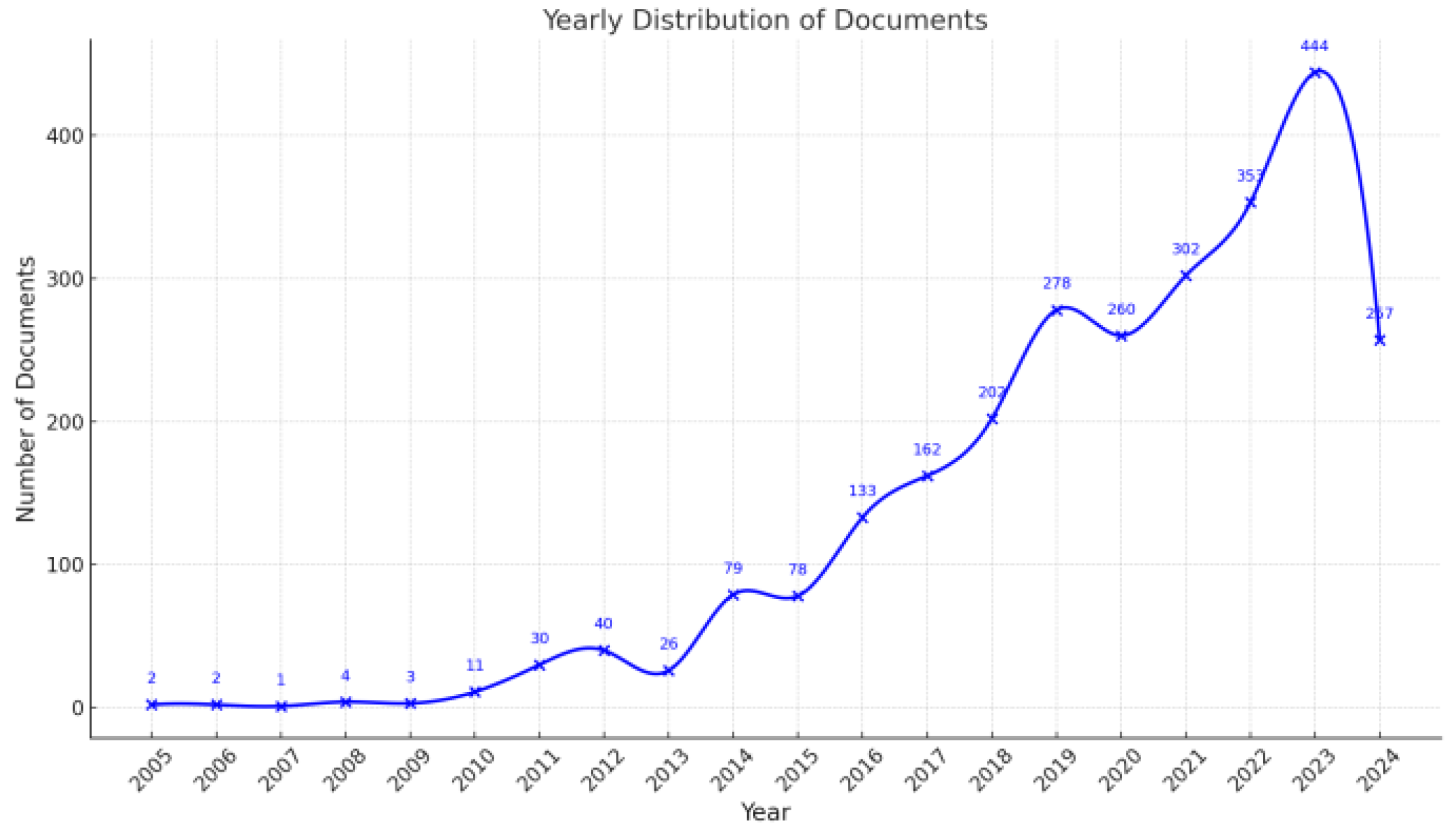

5.1. Yearly Distribution of Documents

5.1.a. Optimization Techniques

- Classical techniques: =16.87% (=697, =4,134)

- Artificial Intelligence-based techniques: =36.01% (=1,489, =4,134)

- Metaheuristic techniques: =47.12% (=1,848, =4,134)

5.1.b. ST

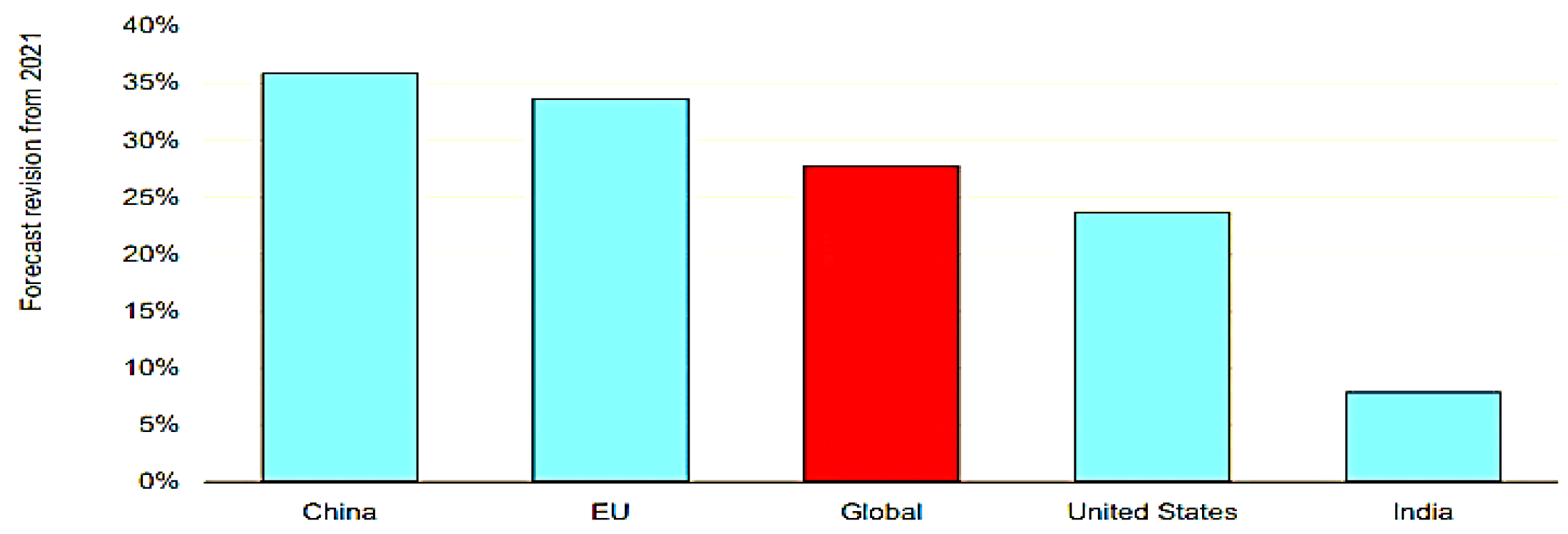

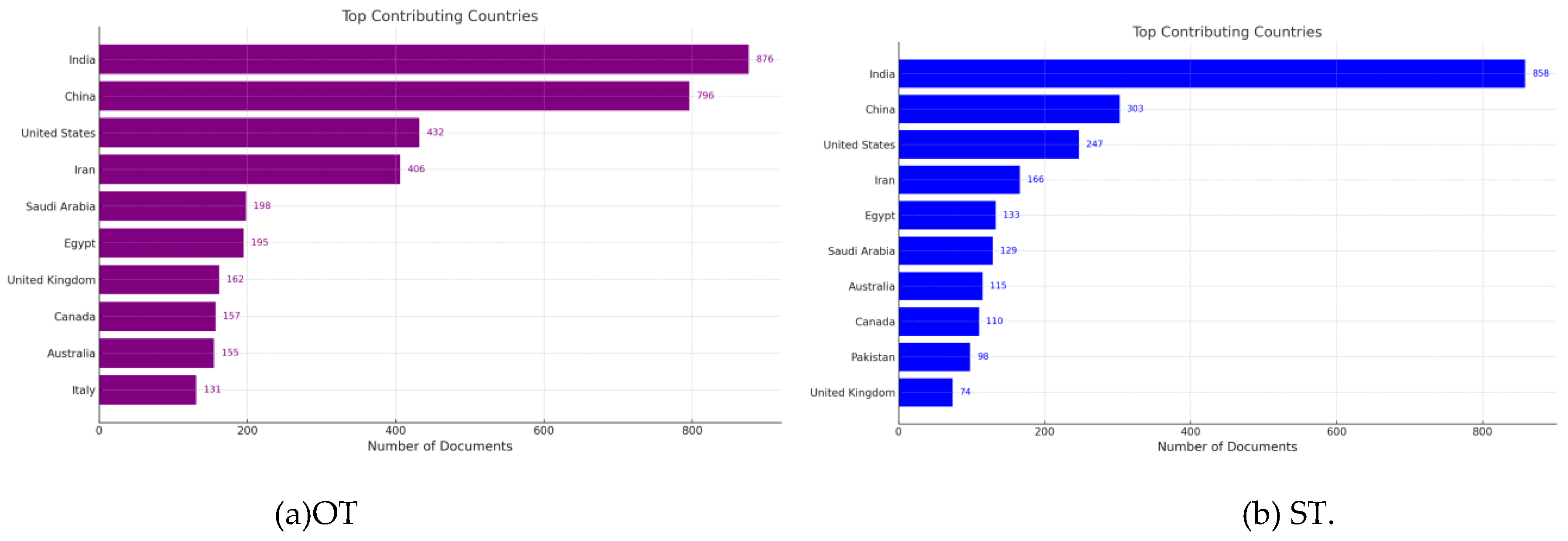

5.2. Top Contributing Countries

5.3. Top Cited Documents

5.3.a. Top Cited Documents in OT

5.3.b Top Cited Documents in ST

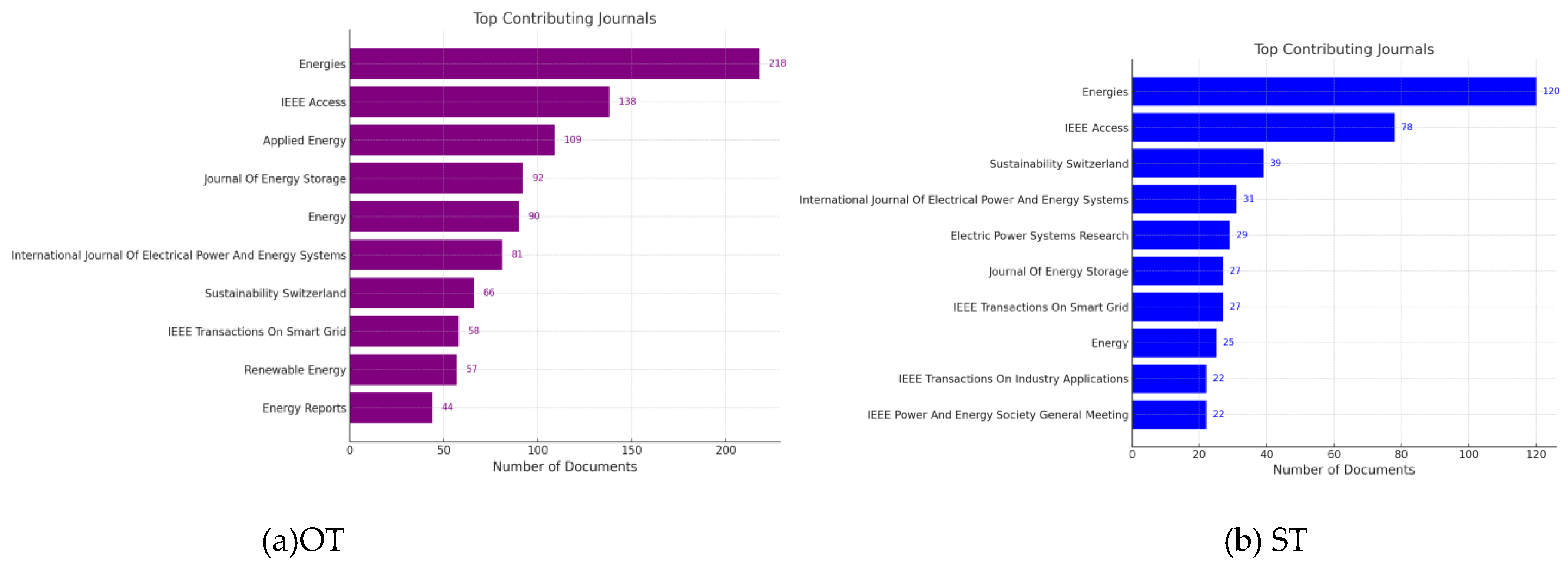

5.4. Top Contributing Journals

5.5. Top Contributing Authors

6. Conclusion and Insights

6.1. Overview of Key Findings

- OT: Advanced methodologies, such as AI-driven approaches, metaheuristics, and MILP, play a pivotal role in improving energy efficiency, reliability, and sustainability by addressing challenges like resource intermittency, load management, and cost optimization.

- ST: Tools like HOMER, MATLAB, and SAM are indispensable for designing, optimizing, and evaluating HMGS configurations, enabling researchers to analyze complex systems under diverse conditions.

6.2. Trends and Implications

6.3. Gaps and Opportunities

- Regional Disparities: Limited exploration of HMGS in low-resource settings and regions with unique energy challenges.

- Emerging Technologies: Greater research is needed into the integration of blockchain, quantum computing, and IoT into MG management.

- Cybersecurity and Data Privacy: Ensuring energy data security and privacy is crucial as AI and connected tools dominate HMGS systems.

6.4. Final Takeaways

- The transformative potential of combining advanced OT with versatile ST.

- The contributions of leading researchers and journals in pushing the boundaries of HMGS innovation.

- The need for continued research into emerging technologies and their integration into energy systems.

7. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iea, “Renewables 2022,” 2022, Accessed: Dec. 10, 2022. [Online]. Available: www.iea.org.

- M. K. Deshmukh and S. S. Deshmukh, “Modeling of hybrid renewable energy systems,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 235–249, Jan. 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. Shivarama Krishna and K. Sathish Kumar, “A review on hybrid renewable energy systems,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 52, pp. 907–916, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Tahir, J. K. A. Tahir, J. Ordóñez, and J. Nieto, “Exploring Evolution and Trends: A Bibliometric Analysis and Scientific Mapping of Multiobjective Optimization Applied to Hybrid Microgrid Systems,” Sustain. 2024, Vol. 16, Page 5156, vol. 16, no. 12, p. 5156, Jun. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. A. Tahir, J. K. A. Tahir, J. Nieto, C. Díaz-López, and J. Ordóñez, “From diesel reliance to sustainable power in Iraq: Optimized hybrid microgrid solutions,” Renew. Energy, vol. 238, p. 121905, Jan. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Fathima and K. Palanisamy, “Optimization in microgrids with hybrid energy systems – A review,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 45, pp. 20 May; 15. [CrossRef]

- S. Hartono, Budiyanto, and R. Setiabudy, “Review of microgrid technology,” 2013 Int. Conf. Qual. Res. QiR 2013 - Conjunction with ICCS 2013 2nd Int. Conf. Civ. Sp., pp. 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. Jha, N. P. Jha, N. Sharma, V. K. Jadoun, A. Agarwal, and A. Tomar, “Optimal scheduling of a microgrid using AI techniques,” Control Standalone Microgrid, pp. 297–336, Jan. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Arar Tahir, M. K. Arar Tahir, M. Zamorano, and J. Ordóñez García, “Scientific mapping of optimisation applied to microgrids integrated with renewable energy systems,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 145, Feb. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Calinescu, C. Chekuri, M. Pál, and J. Vondrák, “Maximizing a monotone submodular function subject to a matroid constraint,” SIAM J. Comput., vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 1740– 1766, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Askarzadeh, “A novel metaheuristic method for solving constrained engineering optimization problems: Crow search algorithm,” Comput. Struct., vol. 169, pp. 1–12, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. O. Mete and Z. B. Zabinsky, “Stochastic optimization of medical supply location and distribution in disaster management,” Int. J. Prod. Econ., vol. 126, no. 1, pp. 76–84, Jul. 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. Metters, “Quantifying the bullwhip effect in supply chains,” J. Oper. Manag., vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 1997. [CrossRef]

- J. Ward, P. J. J. Ward, P. J. Hobbs, P. J. Holliman, and D. L. Jones, “Optimisation of the anaerobic digestion of agricultural resources,” Bioresour. Technol., vol. 99, no. 17, pp. 7928–7940, Nov. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Baquero, J. L. F. Baquero, J. L. Martínez, and R. Cantón, “Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in water environments,” Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 260–265, Jun. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Beume, B. N. Beume, B. Naujoks, and M. Emmerich, “SMS-EMOA: Multiobjective selection based on dominated hypervolume,” Eur. J. Oper. Res., vol. 181, no. 3, pp. 1653–1669, Sep. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Tsikalakis and N. D. Hatziargyriou, “Centralized control for optimizing microgrids operation,” IEEE Trans. Energy Convers., vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 241–248, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Y. M. Atwa, E. F. Y. M. Atwa, E. F. El-Saadany, M. M. A. Salama, and R. Seethapathy, “Optimal renewable resources mix for distribution system energy loss minimization,” IEEE Trans. Power Syst., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 360–370, Feb. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Jiang, J. R. Jiang, J. Wang, and Y. Guan, “Robust unit commitment with wind power and pumped storage hydro,” IEEE Trans. Power Syst., vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 20 May; 12. [CrossRef]

- Cagnano, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Experimental results on the economic management of a smart microgrid,” 20th IEEE Mediterr. Electrotech. Conf. MELECON 2020 - Proc., pp. 459–463, Jun. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. A. Bhuiyan, A. F. A. Bhuiyan, A. Yazdani, and S. L. [CrossRef]

- J. -H. Zhu, H. Ren, J. Gu, X. Zhang, and C. Sun, “Economic dispatching of Wind/ photovoltaic/ storage considering load supply reliability and maximize capacity utilization,” Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 147, p. 10 8874, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Jabari, M. F. Jabari, M. Zeraati, M. Sheibani, and H. Arasteh, “Robust Self-Scheduling of PVs-Wind-Diesel Power Generation Units in a Standalone Microgrid under Uncertain Electricity Prices,” J. Oper. Autom. Power Eng., vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 152–162, Apr. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Introduction to Linear Optimization.

- M. H. Amrollahi and S. M. T. Bathaee, “Techno-economic optimization of hybrid photovoltaic/wind generation together with energy storage system in a stand-alone micro-grid subjected to demand response,” Appl. Energy, vol. 202, pp. 66–77, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- “Applied Dynamic Programming - Richard, E. Bellman, Stuart E Dreyfus - كتب Google.” https://books.google.es/books?hl=ar&lr=&id=ZgbWCgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA3&dq=R.+Bellman,+%22Dynamic+Programming,%22+Princeton+University+Press,+1957.&ots=yg_fO3owFu&sig=i69XETEkYVak1DhWciYOlgEX__E#v=onepage&q=R. Bellman%2C %22Dynamic Programming%2C%22 Princeton University Press%2C 1957.&f=false (accessed Nov. 06, 2023).

- H. Moradi, M. H. Moradi, M. Esfahanian, A. Abtahi, and A. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Lim, B. S. J. Y. Lim, B. S. How, G. Rhee, S. Hwangbo, and C. K. Yoo, “Transitioning of localized renewable energy system towards sustainable hydrogen development planning: P-graph approach,” Appl. Energy, vol. 263, p. 114635, Apr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Kuznetsova, Y.-F. E. Kuznetsova, Y.-F. Li, C. Ruiz, E. Zio, G. Ault, and K. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Kyriakarakos, D. D. G. Kyriakarakos, D. D. Piromalis, A. I. Dounis, K. G. Arvanitis, and G. [CrossRef]

- L. Wen, K. L. Wen, K. Zhou, S. Yang, and X. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Mohanty, S. S. Mohanty, S. Pati, · Sanjeeb, and K. Kar, “Persistent Voltage Profiling of a Wind Energy-Driven Islanded Microgrid with Novel Neuro-fuzzy Controlled Electric Spring,” J. Control. Autom. Electr. Syst., vol. 34, pp. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Singh, L. R. Singh, L. Ding, D. K. Raju, R. S. Kumar, and L. P. Raghav, “Demand response of grid-connected microgrid based on metaheuristic optimization algorithm,” Energy Sources, Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff., Oct. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. M. D. Ross, D. M. M. D. Ross, D. Turcotte, M. Ross, and F. Sheriff, “Photovoltaic hybrid system sizing and simulation tools: Status and Needs Optimal Design and Energy Management for Northern and Remote Microgrids View project Dave Turcotte Natural Resources Canada PHOTOVOLTAIC HYBRID SYSTEM SIZING AND SIMULATION TOOLS: STATUS AND NEEDS,” 2001, Accessed: Aug. 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228496269.

- T. Hasan, K. T. Hasan, K. Emami, R. Shah, N. M. S. Hassan, V. Belokoskov, and M. Ly, “Techno-economic Assessment of a Hydrogen-based Islanded Microgrid in North-east,” Energy Reports, vol. 9, pp. 3380–3396, Dec. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “HOMER - Hybrid Renewable and Distributed Generation System Design Software.” https://www.homerenergy.com/ (accessed Jul. 03, 2023).

- “NSRDB | TMY.” https://nsrdb.nrel.gov/data-sets/tmy (accessed Jul. 03, 2023).

- S. Singh, M. S. Singh, M. Singh, and S. C. Kaushik, “Feasibility study of an islanded microgrid in rural area consisting of PV, wind, biomass and battery energy storage system,” Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 128, pp. 178–190, Nov. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Ahmad et al., “Techno economic analysis of a wind-photovoltaic-biomass hybrid renewable energy system for rural electrification: A case study of Kallar Kahar,” Energy, vol. 148, pp. 208–234, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Abdin and W. Mérida, “Hybrid energy systems for off-grid power supply and hydrogen production based on renewable energy: A techno-economic analysis,” Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 196, pp. 1068–1079, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Shezan, “Design and demonstration of an islanded hybrid microgrid for an enormous motel with the appropriate solicitation of superfluous energy by using iHOGA and matlab,” Int. J. Energy Res., vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 5567–5585, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- “iHOGA / MHOGA – Simulation and optimization of stand-alone and grid-connected hybrid renewable systems.” https://ihoga.unizar.es/en/ (accessed Jul. 06, 2023).

- M. Żołądek, A. M. Żołądek, A. Kafetzis, R. Figaj, and K. Panopoulos, “Energy-Economic Assessment of Islanded Microgrid with Wind Turbine, Photovoltaic Field, Wood Gasifier, Battery, and Hydrogen Energy Storage,” Sustain. 2022, Vol. 14, Page 12470, vol. 14, no. 19, p. 12470, Sep. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, N. Matera, C. Cornaro, G. Oliveti, P. Romagnoni, and L. De Santoli, “EnergyPlus, IDA ICE and TRNSYS predictive simulation accuracy for building thermal behaviour evaluation by using an experimental campaign in solar test boxes with and without a PCM module,” Energy Build., vol. 212, p. 109812, Apr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “TRNSYS 18,” Accessed: Jul. 14, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://sel.me.wisc.edu/trnsyshttp://software.cstb.fr.

- X. Wang et al., “Decarbonization of China’s electricity systems with hydropower penetration and pumped-hydro storage: Comparing the policies with a techno-economic analysis,” Renew. Energy, vol. 196, pp. 65–83, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Lund, J. Z. H. Lund, J. Z. Thellufsen, P. A. Østergaard, P. Sorknæs, I. R. Skov, and B. V. Mathiesen, “EnergyPLAN – Advanced analysis of smart energy systems,” Smart Energy, vol. 1, Feb. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Pochacker, T. M. Pochacker, T. Khatib, and W. Elmenreich, “The microgrid simulation tool RAPSim: Description and case study,” 2014 IEEE Innov. Smart Grid Technol. - Asia, ISGT ASIA 2014, pp. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “RAPSim - Microgrid Simulator download | SourceForge.net.” https://sourceforge.net/projects/rapsim/ (accessed Jul. 15, 2023).

- M. Mukhtar et al., “Effect of Inadequate Electrification on Nigeria’s Economic Development and Environmental Sustainability,” Sustain. 2021, Vol. 13, Page 2229, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 2229, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- “RETScreen.” https://natural-resources.canada.ca/maps-tools-and-publications/tools/modelling-tools/retscreen/7465 (accessed Jul. 15, 2023).

- M. Alam, K. M. Alam, K. Kumar, and V. Dutta, “Analysis of lead-acid and lithium-ion batteries as energy storage technologies for the grid-connected microgrid using dispatch control algorithm,” Stud. Comput. Intell., vol. 916, pp. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Nithyanandam, J. K. Nithyanandam, J. Stekli, and R. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Home - System Advisor Model - SAM.” https://sam.nrel.gov/ (accessed Jul. 15, 2023).

- “Microgrid Protection Using Communication-Assisted Digital Relays | IEEE Journals & Magazine | IEEE Xplore.” https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5352304 (accessed Nov. 24, 2024).

- “Simulink - Simulation and Model-Based Design - MATLAB.” https://www.mathworks.com/products/simulink.html (accessed Nov. 24, 2024).

- “Multiobjective Intelligent Energy Management for a Microgrid | IEEE Journals & Magazine | IEEE Xplore.” https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6157610 (accessed Nov. 20, 2024).

- A. Moghaddam, A. A. Moghaddam, A. Seifi, T. Niknam, and M. R. Alizadeh Pahlavani, “Multi-objective operation management of a renewable MG (micro-grid) with back-up micro-turbine/fuel cell/battery hybrid power source,” Energy, vol. 36, no. 11, pp. 6490–6507, Nov. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Bevrani, F. Habibi, P. Babahajyani, M. Watanabe, and Y. Mitani, “Intelligent frequency control in an AC microgrid: Online PSO-based fuzzy tuning approach,” IEEE Trans. Smart Grid, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 1935– 1944, 2012. [CrossRef]

- T. Ahmad et al., “Artificial intelligence in sustainable energy industry: Status Quo, challenges and opportunities,” JCPro, vol. 289, p. 125834, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Morais, P. H. Morais, P. Kádár, P. Faria, Z. A. Vale, and H. M. Khodr, “Optimal scheduling of a renewable micro-grid in an isolated load area using mixed-integer linear programming,” Renew. Energy, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 151–156, Jan. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Suganthi, S. L. Suganthi, S. Iniyan, and A. A. Samuel, “Applications of fuzzy logic in renewable energy systems – A review,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 48, pp. 585–607, Aug. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J. Wu, Y. Zhou, and N. Jenkins, “Peer-to-peer energy sharing through a two-stage aggregated battery control in a community Microgrid,” Appl. Energy, vol. 226, pp. 261–276, Sep. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Distributed Intelligent Energy Management System for a Single-Phase High-Frequency AC Microgrid | IEEE Journals & Magazine | IEEE Xplore.” https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/4084646 (accessed Nov. 20, 2024).

- H. Borhanazad, S. H. Borhanazad, S. Mekhilef, V. Gounder Ganapathy, M. Modiri-Delshad, and A. Mirtaheri, “Optimization of micro-grid system using MOPSO,” Renew. Energy, vol. 71, pp. 295–306, Nov. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez and, K. Bhattacharya, “Optimal planning and design of a renewable energy based supply system for microgrids,” Renew. Energy, vol. 45, pp. 7–15, Sep. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Badal, P. R. Badal, P. Das, S. K. Sarker, and S. K. Das, “A survey on control issues in renewable energy integration and microgrid,” Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst., vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–27, Dec. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Abdin and W. Mérida, “Hybrid energy systems for off-grid power supply and hydrogen production based on renewable energy: A techno-economic analysis,” Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 196, pp. 1068–1079, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. C. Ou and C. M. Hong, “Dynamic operation and control of microgrid hybrid power systems,” Energy, vol. 66, pp. 314–323, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. Yu, X. X. Yu, X. She, X. Zhou, and A. Q. Huang, “Power management for DC microgrid enabled by solid-state transformer,” IEEE Trans. Smart Grid, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 954–965, Mar. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Li, R. J. Li, R. Xiong, Q. Yang, F. Liang, M. Zhang, and W. Yuan, “Design/test of a hybrid energy storage system for primary frequency control using a dynamic droop method in an isolated microgrid power system,” Appl. Energy, vol. 201, pp. 257–269, Sep. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Ji, J. Y. Ji, J. Wang, J. Xu, X. Fang, and H. Zhang, “Real-Time Energy Management of a Microgrid Using Deep Reinforcement Learning,” Energies 2019, Vol. 12, Page 2291, vol. 12, no. 12, p. 2291, Jun. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Self-Adaptive Virtual Inertia Control-Based Fuzzy Logic to Improve Frequency Stability of Microgrid With High Renewable Penetration | IEEE Journals & Magazine | IEEE Xplore.” https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8731984 (accessed Nov. 24, 2024).

- L. Luo et al., “Optimal scheduling of a renewable based microgrid considering photovoltaic system and battery energy storage under uncertainty,” J. Energy Storage, vol. 28, p. 101306, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Wu, X. H. Wu, X. Liu, and M. Ding, “Dynamic economic dispatch of a microgrid: Mathematical models and solution algorithm,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 63, pp. 336–346, Dec. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Kerdphol, F. S. T. Kerdphol, F. S. Rahman, Y. Mitani, K. Hongesombut, and S. Küfeoğlu, “Virtual inertia control-based model predictive control for microgrid frequency stabilization considering high renewable energy integration,” Sustain., vol. 9, no. 2017; 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Wang, D. P. Wang, D. Wang, C. Zhu, Y. Yang, H. M. Abdullah, and M. A. Mohamed, “Stochastic management of hybrid AC/DC microgrids considering electric vehicles charging demands,” Energy Reports, vol. 6, pp. 1338–1352, Nov. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Nurunnabi, N. K. Roy, E. Hossain, and H. R. Pota, “Size optimization and sensitivity analysis of hybrid wind/PV micro-grids- A case study for Bangladesh,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 150120–15 0140, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Dawood, G. M. Shafiullah, and M. Anda, “Stand-Alone Microgrid with 100% Renewable Energy: A Case Study with Hybrid Solar PV-Battery-Hydrogen,” Sustain. 2020, Vol. 12, Page 2047, vol. 12, no. 5, p. 2047, Mar. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Baghaee, M. R. Baghaee, M. Mirsalim, G. B. Gharehpetian, and H. A. Talebi, “A generalized descriptor-system robust H∞ control of autonomous microgrids to improve small and large signal stability considering communication delays and load nonlinearities,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 92, pp. 63–82, Nov. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Shen, Q. L. Shen, Q. Cheng, Y. Cheng, L. Wei, and Y. Wang, “Hierarchical control of DC micro-grid for photovoltaic EV charging station based on flywheel and battery energy storage system,” Electr. Power Syst. Res., vol. 179, p. 106079, Feb. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. H. Marzebali, M. M. H. Marzebali, M. Mazidi, and M. Mohiti, “An adaptive droop-based control strategy for fuel cell-battery hybrid energy storage system to support primary frequency in stand-alone microgrids,” J. Energy Storage, vol. 27, p. 101127, Feb. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Yuan, M. A. C. Yuan, M. A. Haj-Ahmed, and M. S. Illindala, “Protection Strategies for Medium-Voltage Direct-Current Microgrid at a Remote Area Mine Site,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl., vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 2846–2853, Jul. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Kumar, S. N. M. Kumar, S. N. Singh, and S. C. Srivastava, “Design and control of smart DC microgrid for integration of renewable energy sources,” IEEE Power Energy Soc. Gen. Meet. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||||||

| Ref. | SPV | WT | Energy storage | DG | Other sources | Optimization Focus | Key Findings | |

| [21] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | LCOE, LCOH | Investigated the sizing and economic evaluation of an HMGS SPV-WT-DG-battery system in islanded mode. Results demonstrated reduced life cycle cost with low LPSP, outperforming HOMER in cost-effectiveness. | |

| [22] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | Economic, reliability | Developed a multi-objective dispatching model using the MSIIO technique, optimizing energy storage utilization. Achieved 4.18% higher economic gains and 82.83% capacity utilization, outperforming PSO and differential evolution. | |

| ||||||||

| [23] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | Revenue Maximization, cost reduction | Applied a risk-aware mixed integer nonlinear optimization approach to manage stochastic energy sources. Optimized DG, SPV, and WT operations under market price uncertainties, achieving cost minimization through fuel savings and energy sales. Enhanced energy dispatch and load-generation balance with robust scheduling techniques, including cubic spline interpolation. | |

| ||||||||

| [25] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | Cost Reduction, Efficiency Improvement | Modeled and optimized MG components using MILP, integrating demand response programming for standalone systems. Results demonstrated reduced mismatch, cost savings, and lower battery requirements via load scheduling. Validation performed with HOMER and GAMS using the CPLEX solver. | |

| ||||||||

| [27] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | MT, FC | Cost and emission minimization | Optimized standalone MG energy scheduling using advanced dynamic programming, achieving enhanced efficiency, reduced fuel costs, and decreased emissions. Implemented an optimal energy management system with a constrained single-objective model, minimizing operational and emission costs. Inclusion of battery storage significantly lowered total costs and emissions, demonstrating system feasibility through simulation. | |

| ||||||||

| [28] | Renewable Electricity: Produced from localized HRES.-Non-renewable Electricity: Generated from fossil fuels | Biogas, Hydrogen Generation, Potential Energy Carriers(ammonia, urea) | LCOE, CO2 reduction | Proposed a method for converting surplus renewable electricity, CO₂, and biogas into sustainable hydrogen using a P-graph graphical optimization approach. Scenarios with 20%, 30%, and 40% demand increments showed annual cost increases of 32%, 27%, and 35%, respectively. Transition to non-renewable electricity began at 20% hydrogen demand, with natural gas usage starting at 40%. Sustainability was enhanced through Pareto-frontier and TOPSIS analyses, optimizing the balance between environmental and economic factors. | ||||

| Ref. | SPV | WT | Energy storage | DG | Other sources | Optimization Method | Optimization Focus | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [29] | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | Reinforcement Learning | Optimize battery scheduling, maximize battery and wind utilization, reduce grid dependence | Applied a 2-step-ahead reinforcement learning algorithm for optimized battery scheduling, addressing wind power uncertainties and mechanical failures to reduce grid reliance. Demonstrated a refined strategy for improved decision-making in MG energy management. |

| [30] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | H₂ Production, Desalination, Heating/Cooling | Fuzzy Logic, Grey Prediction Algorithms | Intelligent demand side management | Utilized a multi-agent system with grey prediction for demand management in polygeneration MGs, maintaining effective operation even when demand exceeded design specifications. Optimized within capital constraints, ensuring adaptability for future conditions. |

| [31] | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | EVs | DRNN-LSTM for forecasting, PSO for load dispatch | Optimal load dispatch with forecasting integration | Applied DRNN-LSTM model, outperforming MLP and SVM in forecasting SPV output and residential load. PSO optimized load dispatch, achieving an 8.97% daily cost reduction through peak load shifting. Coordinated EV charging contributed to cost savings and stability. |

| [32] | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ANN-Based Fuzzy Controller | Voltage stability in wind-fed isolated MG | The ANN-based fuzzy controller effectively maintained voltage stability in variable wind conditions, achieving stable system performance with acceptable THD levels. It successfully managed power distribution between critical and non-critical loads, ensuring near-nominal voltage throughout the system. |

| [33] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | BWO | Optimal MG energy management with DRPs | The stochastic day-ahead EMS, using price-driven DRPs, optimized cost and energy coordination by incorporating a flexible price elasticity model for realistic customer responses. The BWO algorithm determined optimal resource scheduling in a 3-feeder MG system, effectively addressing renewable intermittency through stochastic scenario generation. |

| Ref. | SPV | WT | Energy storage | DG | Other sources | Optimization Focus | Key Findings | Software tool | Software description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [35] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | LCOE, LCOH | Assessed HMG for green hydrogen production on a remote island. Scenario analysis revealed 80% RES as most cost-effective. | HOMER | Hybrid Optimization of Multiple Energy Resources (HOMER) was developed in 1993 by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) [36]. It is designed to model and simulate various RESs, and it excels in cost analysis and sensitivity analysis, with integration capabilities for Typical Meteorological Year (TMY2) data for weather and solar radiation, or user-provided data [37]. HOMER employs a proprietary simulation-based approach for optimization, using sensitivity analysis and a search algorithm to identify the lowest-cost system configurations across various input variables. It is widely used for the economic and technical assessment of large-scale HESs. Strength: Excellent for optimizing component sizing and conducting thorough cost analyses, with advanced sensitivity analysis capabilities. Weakness: May not capture all dynamics of complex system behavior without precise, customized input data. |

| [38] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | biomass | Size, LCOE | Proposed SPV-WT-biomass-storage system to meet remote area needs. ABC algorithm shortened simulation time vs HOMER and PSO. | HOMERABC PSO |

|

| [39] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | biomass | Size, LCOE | HMGS for a 50 MW power plant in Pakistan; profitable with national grid integration, ideal for regions with frequent power outages. | HOMER | |

| [40] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | LCOE | Techno-economic assessment for off-grid HMGS in the USA, Canada, and Australia; evaluated SPV-WT-battery with hydrogen storage. Minimum COE achieved with integrated SPV-WT-battery, electrolyzer, and hydrogen tank, reducing costs to 0.50 $/kWh compared to non-battery configurations at 0.78 $/kWh. | HOMER | |

| [41] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | Cost, size | Assessed thermal energy storage in an islanded HMGS; DG contributed to higher COE. | IHOGA | IHOGA, developed by researchers at the University of Zaragoza, Spain, is designed for simulating and optimizing RES-based electric power systems. It has two versions: IHGO for systems up to 5 MW and MHOGA for larger systems without capacity limits. IHOGA’s library includes diverse components like SPV, WT, batteries, hydropower turbines, and various generators. It calculates NPC, LCOE, NPV, IRR, and battery lifespan, using genetic algorithms to improve system efficiency and reduce costs over successive iterations [42]. Strength: Effective genetic algorithm for optimizing cost and sizing in HES. Weakness: Computationally intensive; may require fine-tuning for complex systems. |

| [43] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | biomass | Cost, feasibility | Evaluated HMGS for tourist regions in Europe, achieving 99% user demand coverage with RES in Gdansk, Poland, and 43% surplus in Agkistro, Greece." | TRNSYS | TRNSYS, developed in 1975 by France, Germany, and the United States, is a transient systems simulation tool used across various energy applications, including biomass, cogeneration, hydrogen fuel cells, wind and SPV systems, high-temperature solar, and geothermal heat pumps. It requires minimal data and computational resources, making it suitable for preliminary assessments [44,45]. Strength: High-fidelity transient simulation ideal for detailed technical system analysis. Weakness: Economic optimization is not the primary focus and may need additional modules for financial assessment. |

| [46] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | BiomassHydropower | CO2 reduction | Decarbonization study for Sichuan Province: scenarios showed energy storage significantly reduced operational costs while requiring high investment, demonstrating feasibility for hydropower-rich regions | EnergyPlan | EnergyPLAN, developed by Aalborg University’s Sustainable Energy Planning Research Group in Denmark in 2000, is a deterministic simulation tool for modeling national energy systems including power, heating, cooling, industry, and transportation [47]. Strength: Effective for strategic policy scenario analysis. Weakness: Primarily a simulation tool, requiring additional software for detailed optimization. |

| [48] | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | Modeling and simulation | Demonstrated RAPSim for optimal DG placement in an MG, considering SPV output variability influenced by solar radiation and time-dependent factors. Showcased software’s capabilities in data output, scenario management, and temporal/weather simulation. | RAPSim | Developed at Alpen Adria University Klagenfurt, RAPSim is an open-source tool for RES simulation in grid-connected and off-grid MGs. It prioritizes power production estimation for each source before conducting power flow analysis [49]. Strength: Detailed simulation for RES with scenario management. Weakness: Lacks built-in economic and sensitivity analysis; may require additional tools for comprehensive assessments. |

| [50] | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | techno-economic, feasibility | Assessed the viability of a 500 kW SPV MG across 12 sites in Nigeria, including a techno-economic analysis. Findings showed economic feasibility at all sites, with payback periods ranging from 6.3 to 7.4 years based on NPC, internal rate of return, and payback period metrics. | RETScreen | Developed by Canada’s Ministry of Natural Resources, RETScreen is a publicly available tool for assessing the costs and benefits of RE technologies worldwide. Released in 1998, RETScreen is particularly useful for on-grid feasibility analysis [51]. Strength: Comprehensive feasibility analysis, covering financial viability and risk assessment. Weakness: Limited in optimization capabilities; primarily focused on project feasibility rather than detailed system design. |

| [52] | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | LCOE, feasibility | Evaluated a grid-connected MG with SPV and energy storage, comparing lead-acid (LA) and lithium-ion (LI) batteries. Findings showed that LI batteries are more feasible with an LCOE of 6.75, compared to 10.6 for LA. | NREL SAM | The System Advisor Model (SAM), developed by NREL and Sandia National Laboratories, provides a robust platform for techno-economic analysis across various RES, including CST, SPV, WT, fuel cells, biomass, and geothermal. It offers insights into CST technologies and RES globally, available as a free, versatile tool for technical and financial assessments [53,54]. Strength: Highly versatile for techno-economic analysis and performance modeling across diverse RES. Weakness: Broad capabilities may lack the specificity found in dedicated optimization tools. |

| [55] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | MG protection using communication-assisted digital relays | Proposed a protection scheme using digital relays with communication networks. Demonstrated detection of high-impedance faults in a high-penetration HMGS. Simulated in MATLAB/Simulink's SimPowerSystems toolbox. | MATLAB/ Simulink |

MATLAB/Simulink, developed by MathWorks, is a high-performance environment for technical computing and simulation, extensively used for modeling, simulating, and analyzing dynamic systems, including MGs [56]. It enables integration with toolboxes like SimPowerSystems for RE applications, grid modeling, and fault detection in MGs [55]. Strength: Flexible and highly customizable, with extensive libraries for RES modeling and advanced fault analysis. Weakness: Requires expertise for custom implementation; computationally intensive for large-scale simulations. |

| Ref. | Authors | Journal | Year | Citations |

| [57] | Chaouachi, A., Kamel, R.M., Andoulsi, R., Nagasaka, K. | IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics | 2013 | 575 |

| [58] | Moghaddam, A.A., Seifi, A., Niknam, T., Alizadeh Pahlavani, M.R. | Energy | 2011 | 540 |

| [59] | Bevrani, H., Habibi, F., Babahajyani, P., Watanabe, M., Mitani, Y. | IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid | 2012 | 519 |

| [60] | Ahmad, T., Zhang, D., Huang, C., Song, Y., Chen, H. | Journal of Cleaner Production | 2021 | 483 |

| [61] | Morais, H., Kádár, P., Faria, P., Vale, Z.A., Khodr, H.M. | Renewable Energy | 2010 | 476 |

| [62] | Suganthi, L., Iniyan, S., Samuel, A.A. | Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews | 2015 | 435 |

| [63] | Long, C., Wu, J., Zhou, Y., Jenkins, N. | Applied Energy | 2018 | 422 |

| [61] | Ramli, M.A.M., Bouchekara, H.R.E.H., Alghamdi, A.S. | Renewable Energy | 2018 | 421 |

| [64] | Chakraborty, S., Weiss, M.D., Simões, M.G. | IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics | 2007 | 403 |

| [65] | Borhanazad, H., Mekhilef, S., Gounder Ganapathy, V., Modiri-Delshad, M., Mirtaheri, A. | Renewable Energy | 2014 | 393 |

| Ref. | Authors | Journal | Year | Citations |

| [55] | Sortomme, E., et al. | IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery | 2010 | 513 |

| [66] | Hafez, O., Bhattacharya, K. | Renewable Energy | 2012 | 489 |

| [38] | Singh, S., et al. | Energy Conversion and Management | 2016 | 383 |

| [25] | Amrollahi, M.H., Bathaee, S.M.T. | Applied Energy | 2017 | 340 |

| [67] | Badal, F.R., et al. | Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems | 2019 | 332 |

| [39] | Ahmad, J., et al. | Energy | 2018 | 282 |

| [68] | Abdin, Z., Mérida, W. | Energy Conversion and Management | 2019 | 268 |

| [69] | Ou, T.-C., Hong, C.-M. | Energy | 2014 | 221 |

| [70] | Yu, X., et al. | IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid | 2014 | 206 |

| [71] | Li, J., et al. | Applied Energy | 2017 | 202 |

| Rank | Journal Name | Number of Documents | High-Cited Article | Citation Count |

| 1 | Energies | 218 | [72] | 186 |

| 2 | IEEE Access | 138 | [73] | 172 |

| 3 | Applied Energy | 109 | [63] | 422 |

| 4 | Journal of Energy Storage | 92 | [74] | 244 |

| 5 | Energy | 90 | [58] | 540 |

| 6 | International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems | 81 | [75] | 179 |

| 7 | Sustainability Switzerland | 66 | [76] | 127 |

| 8 | IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid | 58 | [59] | 519 |

| 9 | Renewable Energy | 57 | [61] | 476 |

| 10 | Energy Reports | 44 | [77] | 100 |

| Rank | Journal name | Number of documents | High-cited article | Citation count |

| 1 | Energies | 120 | [77] | 148 |

| 2 | IEEE Access | 78 | [78] | 125 |

| 3 | Sustainability Switzerland | 39 | [79] | 154 |

| 4 | International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems | 31 | [80] | 130 |

| 5 | Electric Power Systems Research | 29 | [81] | 81 |

| 6 | Journal of Energy Storage | 27 | [82] | 59 |

| 7 | IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid | 27 | [70] | 206 |

| 8 | Energy | 25 | [39] | 282 |

| 9 | IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications | 22 | [83] | 142 |

| 10 | IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting | 22 | [84] | 48 |

| Rank | Author | No. of publications | Key Focus Areas |

| 1 | Guerrero, J.M. | 35 | Distributed control, HMGS optimization, and intelligent energy management. |

| 2 | Gharehpetian, G.B. | 19 | Robust control, fault management, and resilient microgrid operation. |

| 3 | Dey, B. | 18 | Multi-objective optimization, renewable integration, and cost minimization in MGs. |

| 4 | Ustun, T.S | 15 | Cybersecurity, distributed control, and load frequency stability in MGs. |

| 5 | Marzband, M. | 15 | Stochastic optimization, demand response, and energy management in smart MGs. |

| Rank | Author | No. of publications | Key Focus Areas |

| 1 | Guerrero, J.M. | 24 | Application of HOMER and MATLAB for hybrid systems, renewable integration, and grid stability. |

| 2 | Baghaee, H.R. | 21 | Fault-tolerant distributed control and resilience in islanded MGs. |

| 3 | Shahnia, F. | 19 | Stability analysis, system coupling, and optimization in sustainable MGs. |

| 4 | Gharehpetian, G.B. | 18 | Fault management, robust distributed systems, and islanded MG controls. |

| 5 | Ghosh, A. | 14 | Cooperative energy storage control, harmonic mitigation, and voltage regulation in MGs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).