Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

23 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- i.

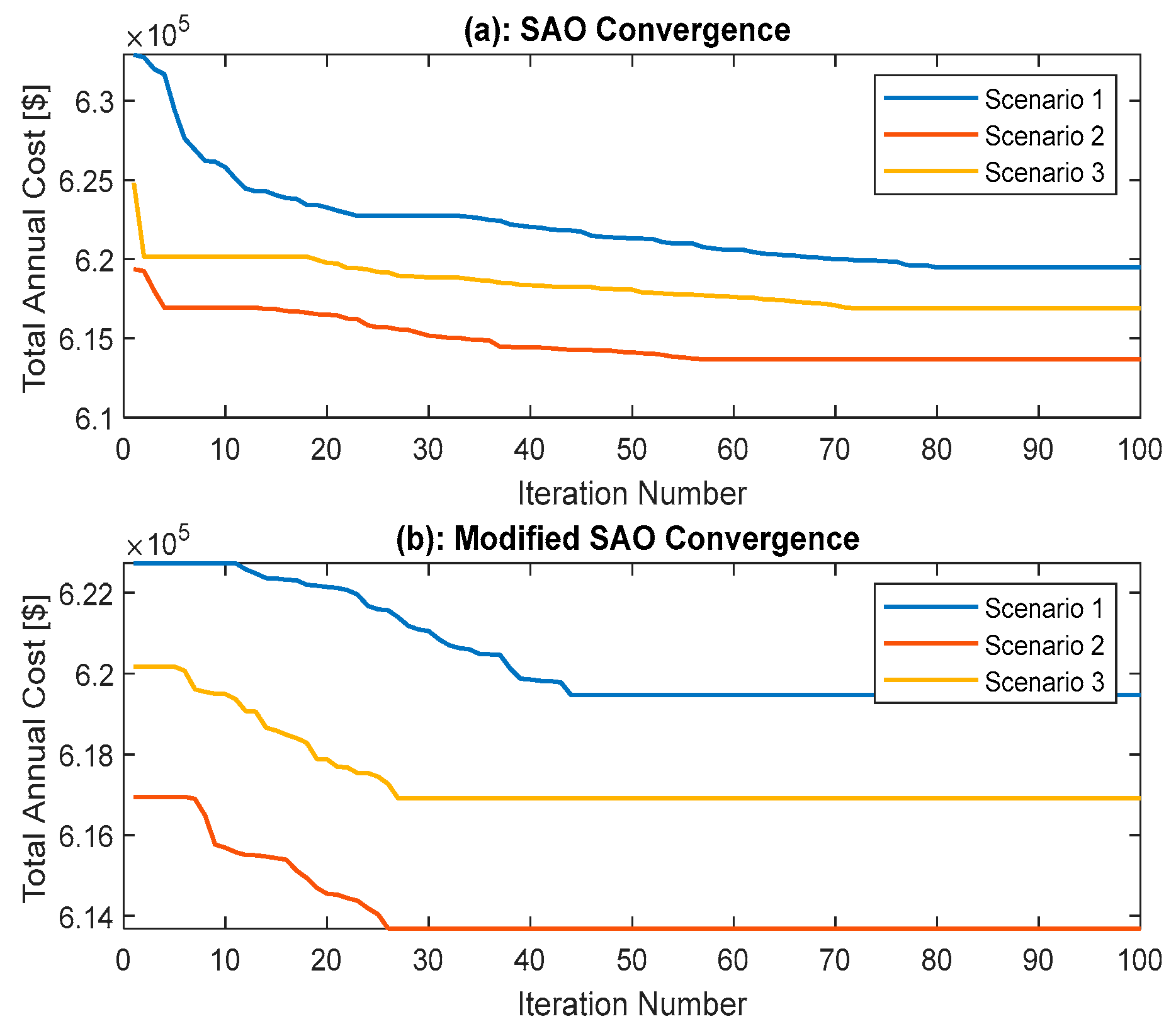

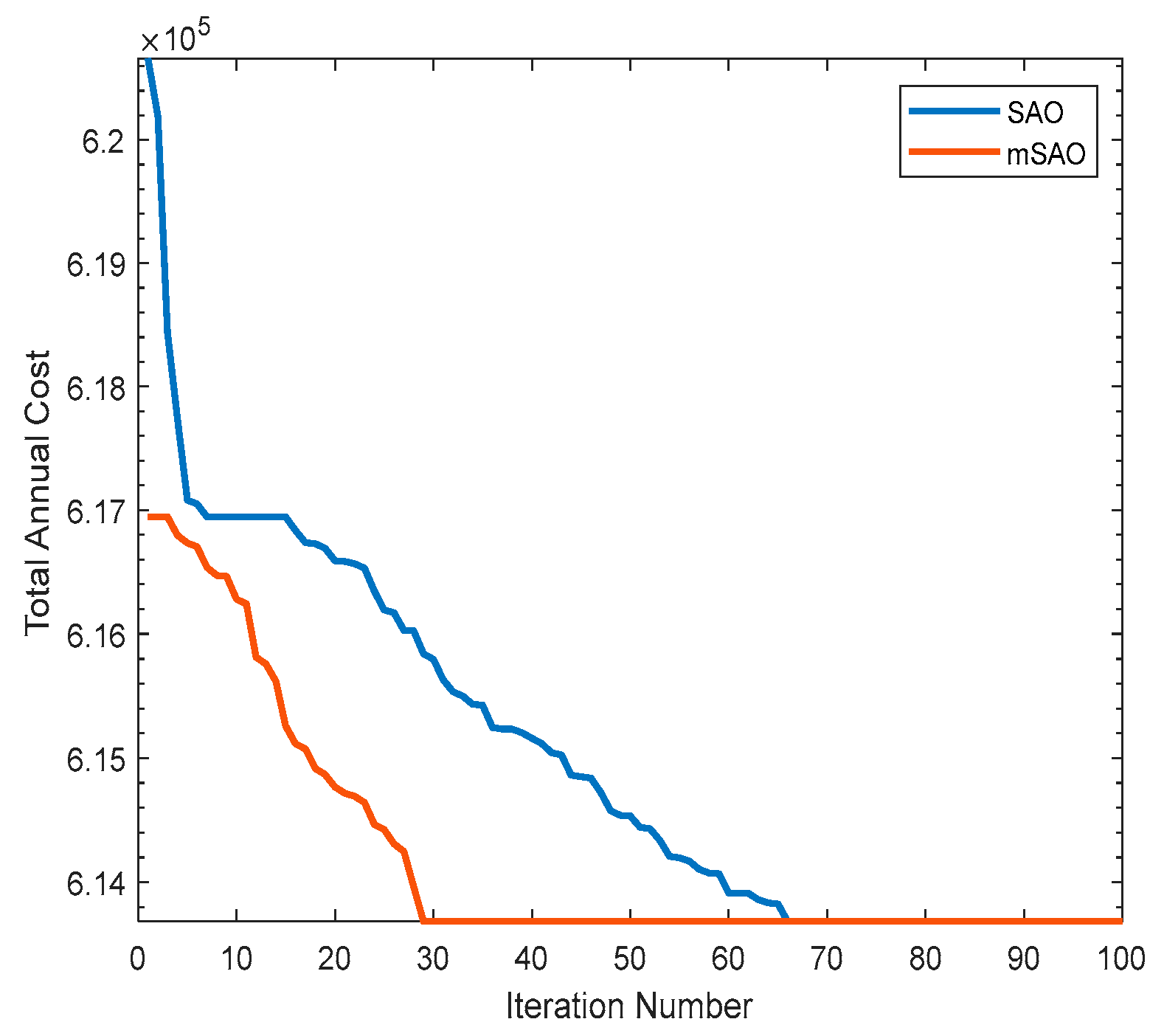

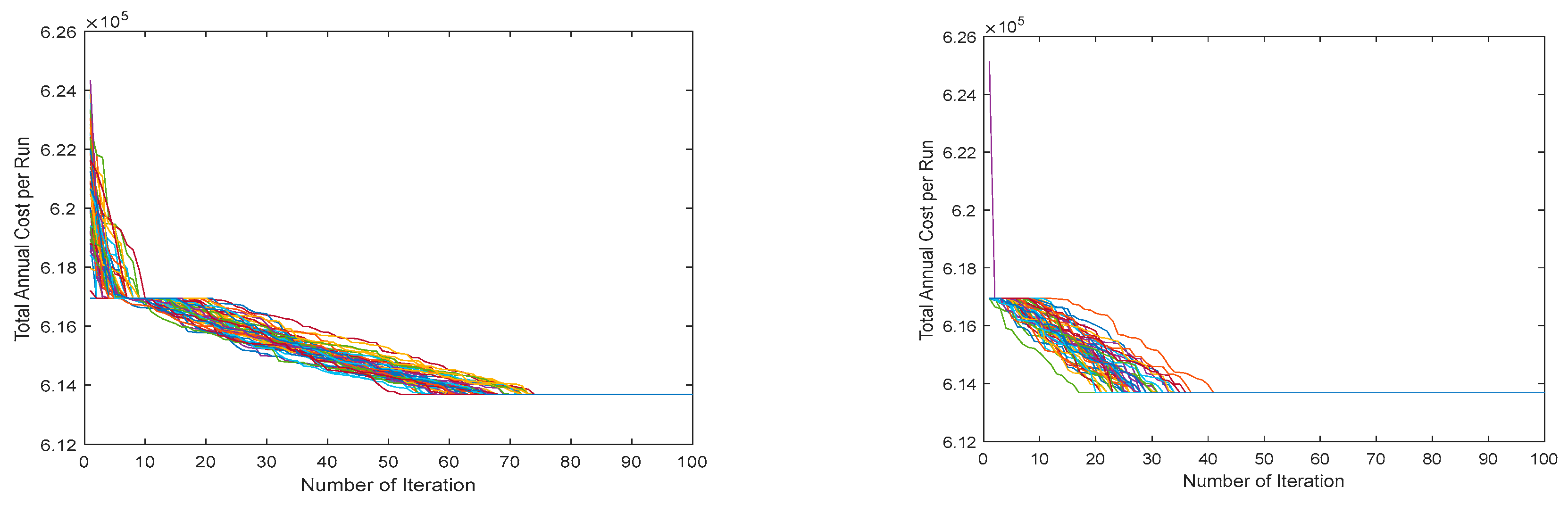

- The paper presents a modified version of the Smell Agent Optimization (SAO) algorithm, which uses a time-dependent approach to adapt the control parameters dynamically as the algorithm progresses. This modification improves convergence and search efficiency, addressing the limitations of the original SAO algorithm.

- ii.

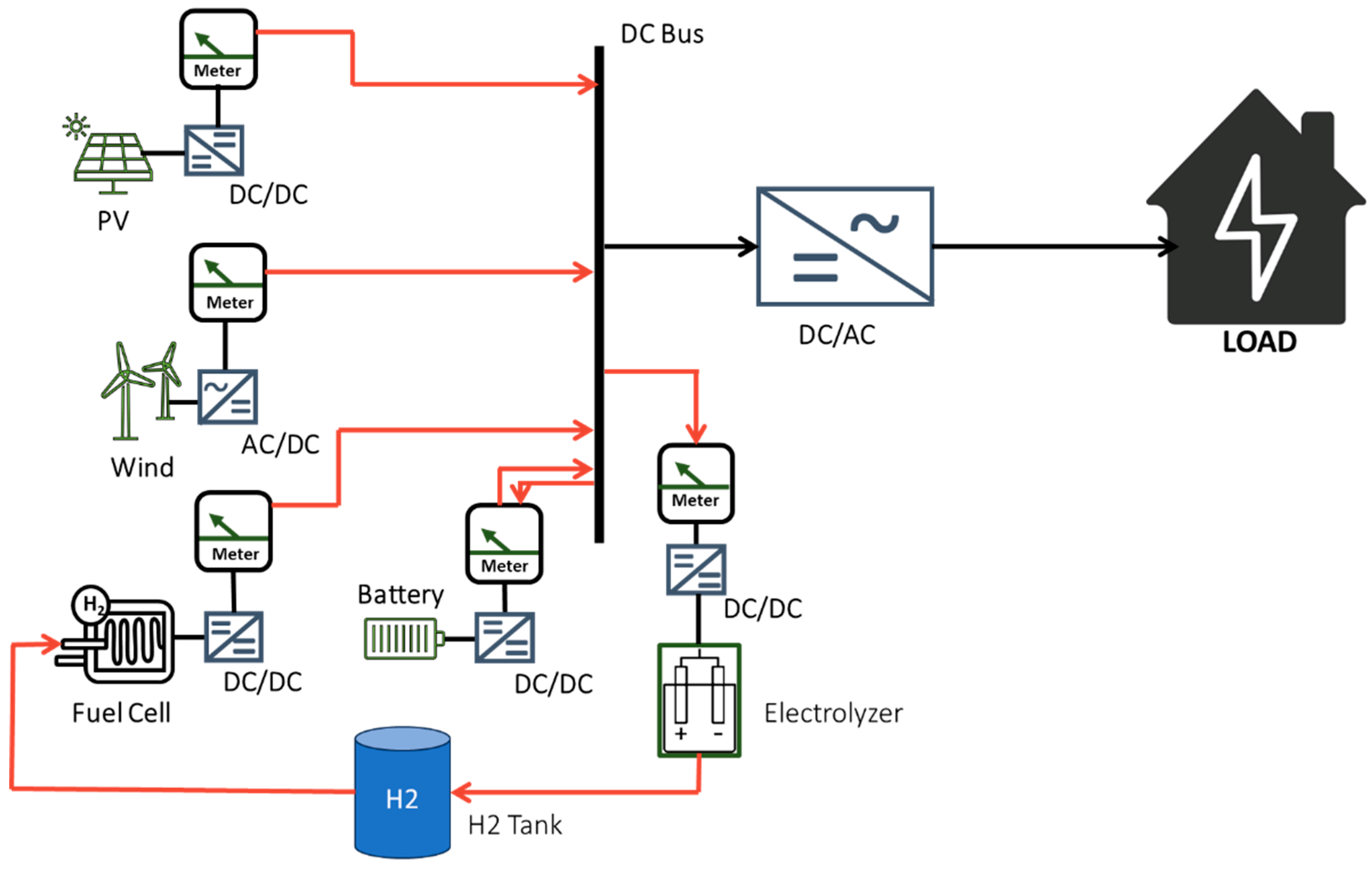

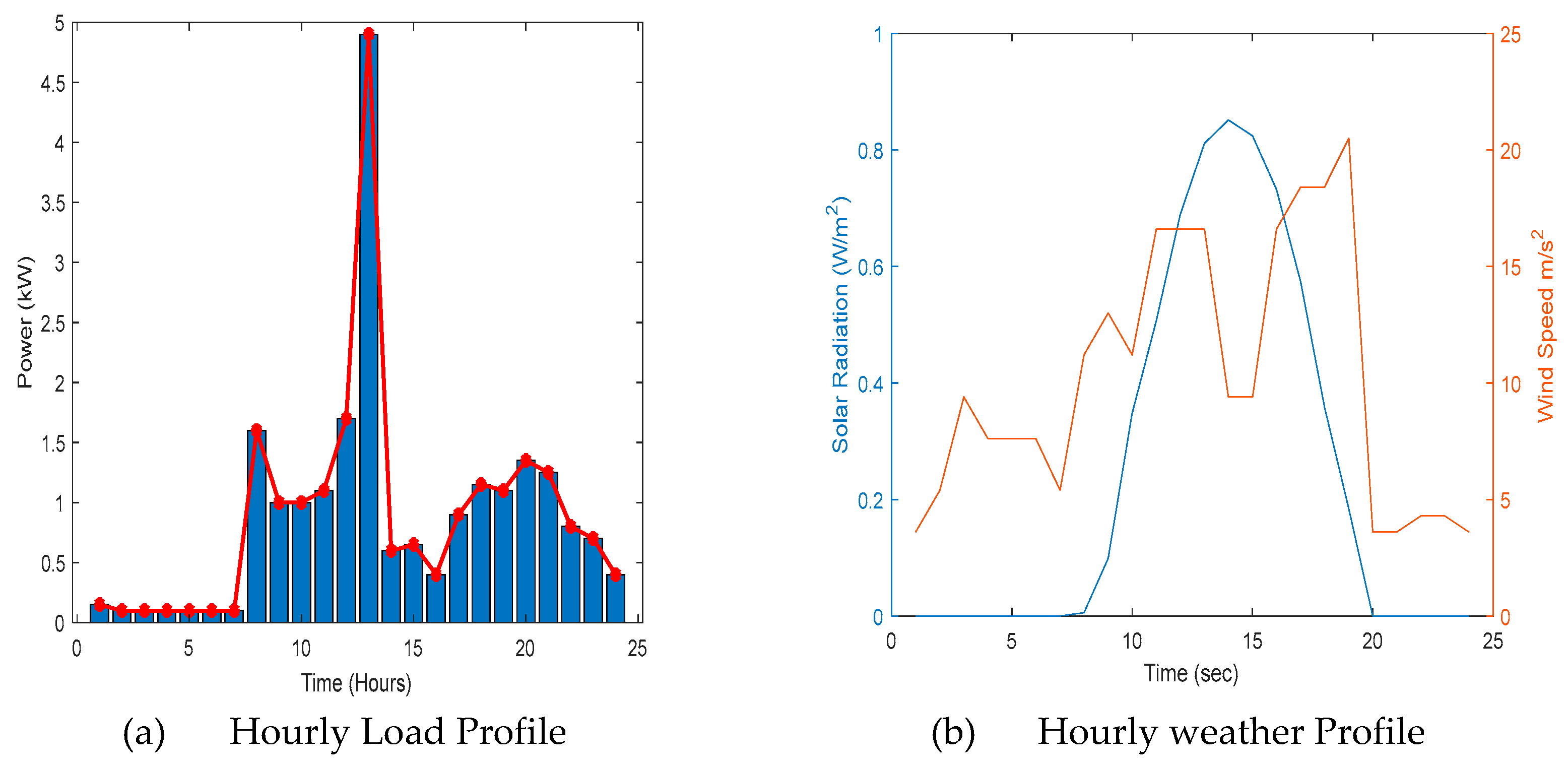

- The paper applies both the modified and standard SAO algorithms to design a hybrid renewable energy system (HRES) for an isolated residential building, in Annaba Algeria. The system includes photovoltaic panels, wind turbines, fuel cells, batteries, and hydrogen storage, all integrated with a DC-bus microgrid.

- iii.

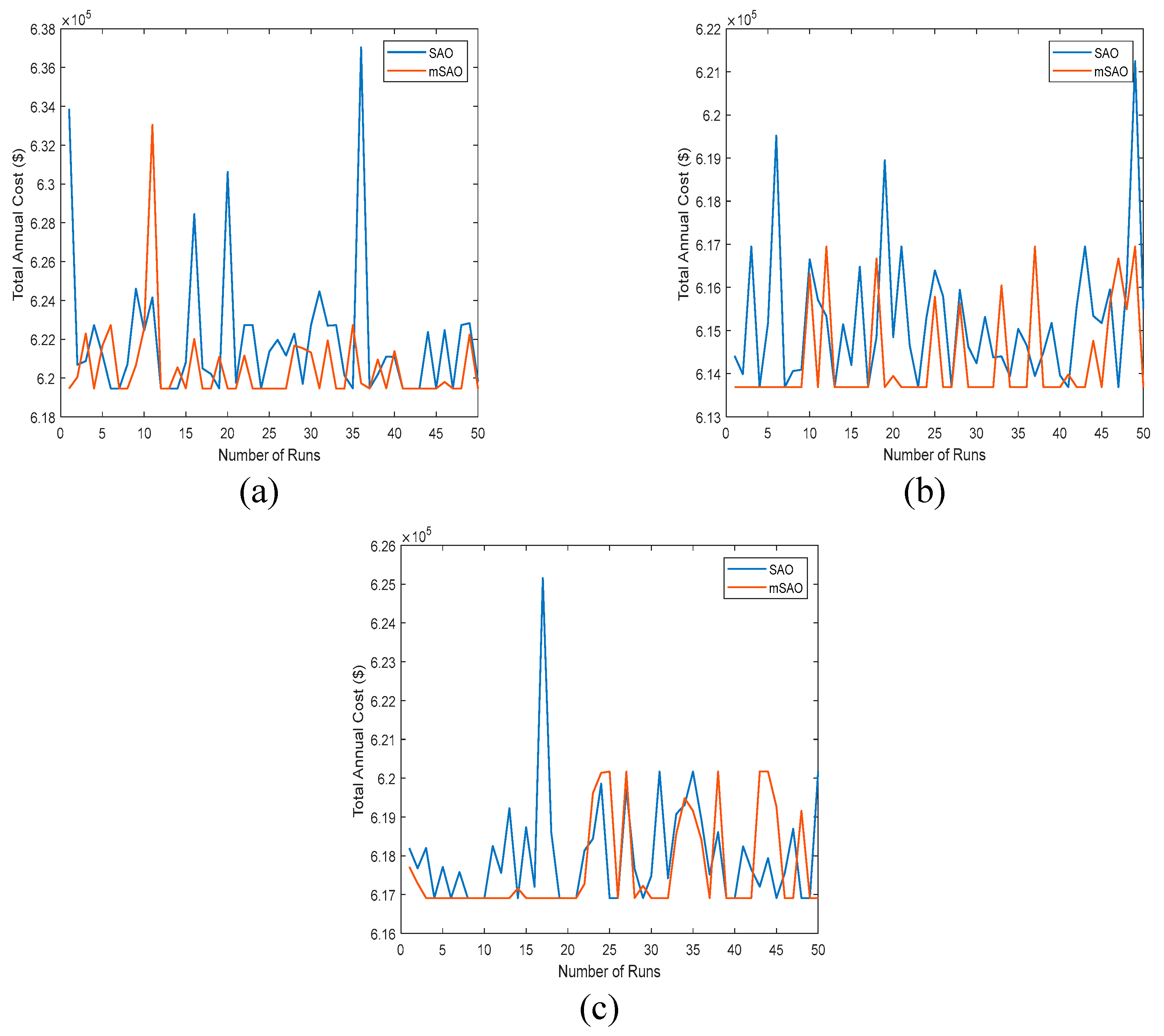

- Through simulations, the paper proved that, modified SAO (mSAO) outperformed the standard SAO in terms of economic performance, reducing the total annual cost (TAC) to approximately $614288.8 and the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) to $0.013/kWh, compared to the TAC, $615217 and the LCOE, $0.077/kWh achieved by the SAO, ensuring optimal power delivery and maximizing project profitability over the HRES lifetime.

2. Configuration of the System Under Study

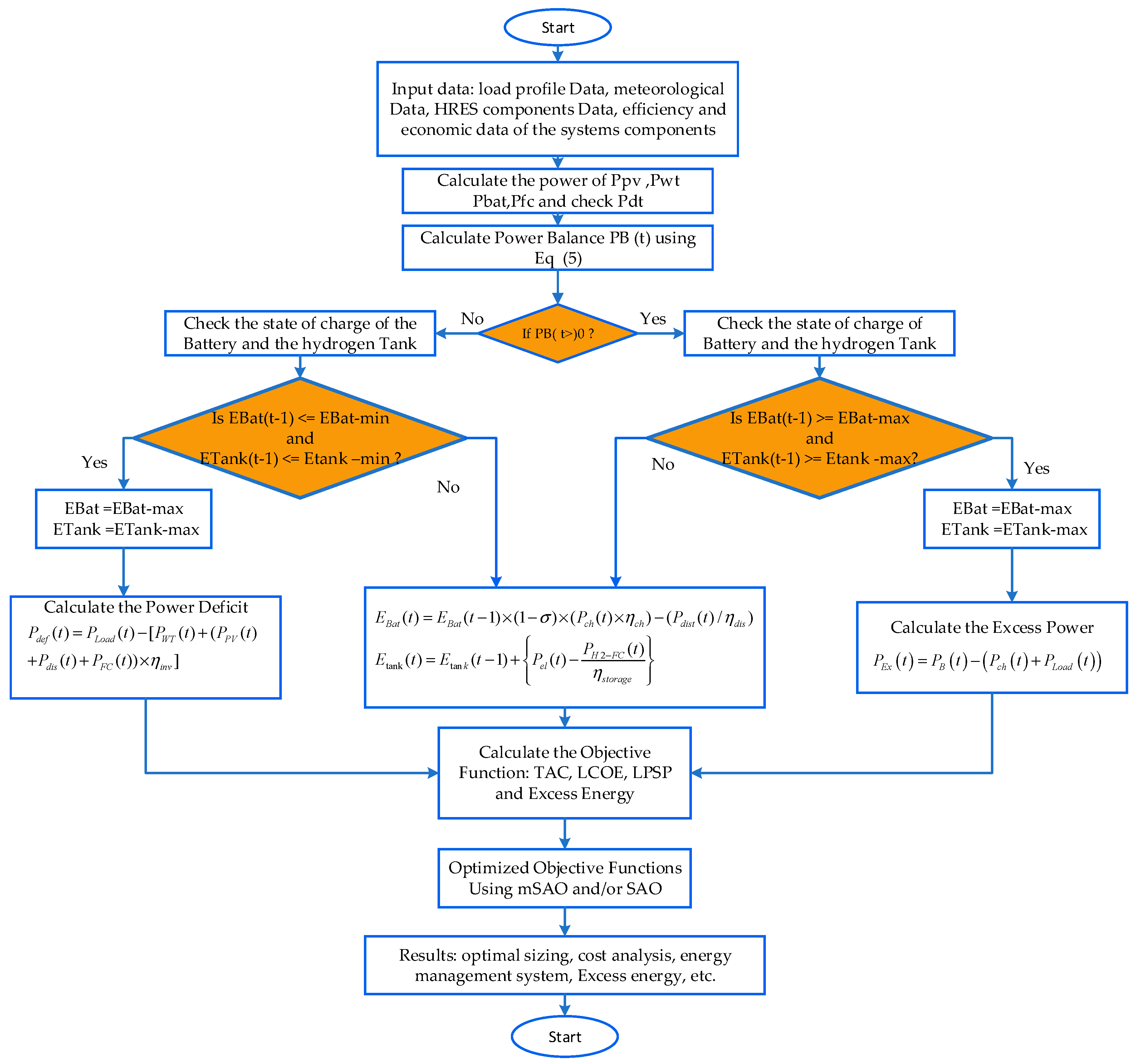

2.1. System Modeling

- A.

- PV model

- B. Wind turbine model

- C. Energy Storage

- Charging mode, when there is excess energy i.e :

- Discharging mode, when there is deficit energy i.e:

- D. Inverter model

2.2. Problem Formulation

2.2.1. Objective Function

2.2.2. Different Constraints

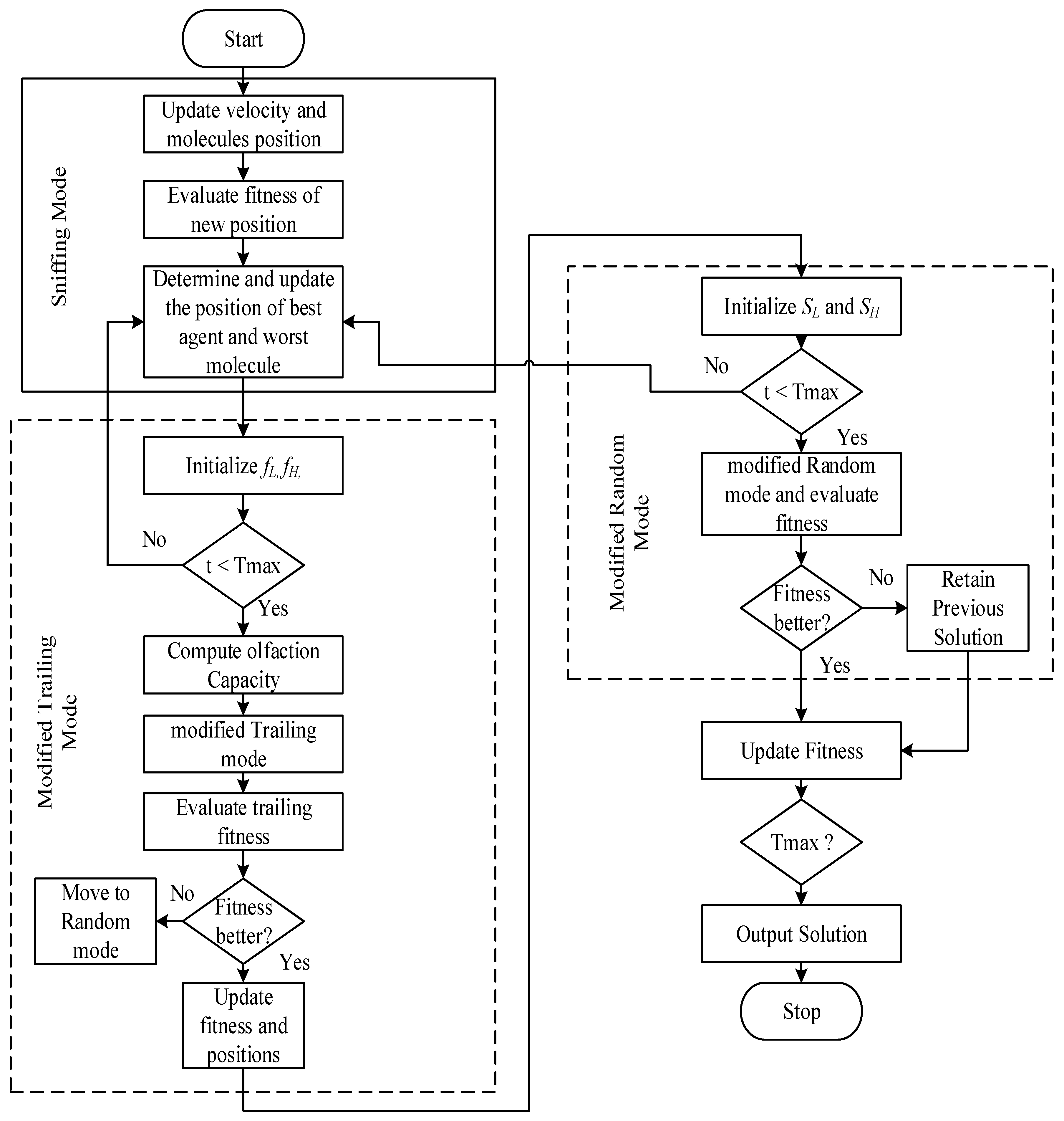

3. Optimization Approaches for Microgrid Energy Management

3.1. Smell Agent Optimizer

- Sniffing Mode: Initial exploration of the search space.

- 2.

- Trailing Mode: Agents follow the best solution found.

- 3.

- Random Mode: Random exploration to avoid local optimal.

3.2. Modified Smell Agent Optimizer (mSAO)

4. Multisource Model Energy Management Strategy

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Optimization Technique Analysis

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

|

Lower limit of solar panels number Upper limit of solar panels number Number of wind turbine Lower limit number of WT Upper limit number of WT Power balance Energy consumed to charge the batteries Energy supplied from the batteries to the load Fuel cells power output power Fuel cells rating power Amount of hydrogen generated Amount of hydrogen generated and stored Energy consumed by fuel cell to generate power Inverters rating power Energy available at (t) in the batteries Energy available in the batteries at (t-1) Nominal capacity of the batteries |

Battery self-discharge rate Efficiency of the solar panel Battery charging system efficiency Battery discharging efficiency Electrolyzer efficiency Fuel cells efficiency SOC state of charge of battery SOC min state of charge minimal of battery Upper limit of batteries capacity Energy available at (t) in the tank Energy available in the tank at (t-1) Hydrogen minimum permissible energy Nominal capacity hydrogen tank Lower limit number of hydrogen tank Upper limit number of hydrogen tank Lower limit number of Fuel cell Upper limit number of Fuel Cell Lower limit number of Electrolyzer Upper limit number of Electrolyzer Batteries minimum permissible energy Maximal capacity of the batteries Lower limit of batteries capacity |

Appendix A.1

| Component systems | Parameters | Specifications |

| PV | Nominal Pv power Pr-Pv Pv cost CPv Surface area A Pv efficiency ηPV Pv lifetime |

120 W $216 1.07 m2 12% 20 years |

| Wind Turbine | Nominal Wt power Pr-Wt Vcut-in Vcut-out Vr CWind Maintenance cost CMntWind Wt lifetime |

1 kW 3 m/s 20 m/s 9 m/s $1804 $100 20 years |

| FC | Nominal FC power FC efficiency (ηFC) FC lifetime FC cost (CFC) Replacement cost (CMnt-FC) |

3 kW 50% 5 years $20000 $1400 |

| Battery | Energy capacity (Eb,u) Maximum discharge power (b,max) Maximum charge power (Pb,min) Maximum SoCb minimum SoCb Capital Cost (CCb) Equivalent full cycles (Ncycles,b) Maintenance cost (Com;b) |

1000 Wh 1000 W 1000 0.9 0.24 2000 $ 471 5% CCb $/year |

| Electrolyzer | Nominal electrolyzer power Electrolyzer efficiency (hEle) Electrolyzer lifetime Electrolyzer cost (CEle) Replacement cost (CMnt-Ele) |

3 kW 74% 5 years $20000 $1400 |

| H2Tank | Reservoir tanks cost (CHT) Nominal capacity of hydrogen tank |

$2000 0.3 kW |

| Converter | Power converter inverter efficiency (η conv/inv) Converter/inverter lifetime Converter/inverter cost |

3 kW 95% 10 years $1583 |

| Other parameters | Interest rate of project i lifespan of the project n |

5% 20 years |

Appendix A.2

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

| Number of Smell Molecules | N | 50 |

| Number of the decision variable | D | 4 |

| Temperature | T | 3 |

| Mass | m | 2.4 |

| Boltzman’s constant | K | 1.38× |

| Maximum iteration | itr | 100 |

References

- De Vito, S., et al. Electric Transmission and Distribution Network Air Pollution. Sensors . (20240.24(2): 587.

- Sharaf MA, Armghan H, Ali N, Yousef A, Abdalla YS, Boudabbous AR, Mehdi H, Armghan A. Hybrid control of the DC microgrid using deep neural networks and global terminal sliding mode control with the exponential reaching law. Sensors. 2023 Nov 22;23(23):9342.

- Thirunavukkarasu GS, Seyedmahmoudian M, Jamei E, Horan B, Mekhilef S, Stojcevski A. Role of optimization techniques in microgrid energy management systems—A review. Energy Strategy Reviews. 2022 Sep 1;43:100899.

- Lo WL, Chung HS, Hsung RT, Fu H, Shen TW. PV Panel Model Parameter Estimation by Using Particle Swarm Optimization and Artificial Neural Network. Sensors. 2024 May 9;24(10):3006.

- Biliyok AS, Tijani SA. Improved Smell Agent Optimization Sizing Technique Algorithm for a Grid-Independent Hybrid Renewable Energy System. InRenewable Energy-Recent Advances 2022 Oct 12. IntechOpen.

- Drici M, Houabes M, Salawudeen AT, Bahri M. Optimum design of an off-grid PV/WT/FC/battery based microgrid for sustainable and cost-effective energy optimization. Studies in Engineering and Exact Sciences. 2024 Jul 3;5(2):e5438-.

- Shuang Wang , Abdelazim G. Hussien , Sumit Kumar, Ibrahim AlShourbaji and Fatma A. Hashim . A modified smell agent optimization for global optimization and industrial engineering design problems.Journal of Computational Design and Engineering, 2023, 10,2147–2176. [CrossRef]

- Mariye Jahannoosh , Saber Arabi Nowdeh , Amirreza Naderipour , Hesam Kamyab , Iraj Faraji Davoodkhani , Jiří Jaromír Klemeš .New Hybrid Meta-Heuristic Algorithm for Reliable and CostEffective Designing of Photovoltaic/Wind/Fuel Cell Energy System Considering Load Interruption Probability.journal of Cleaner Production . [CrossRef]

- Khan A, Javaid N. Optimal sizing of a stand-alone photovoltaic, wind turbine and fuel cell systems. Computers & Electrical Engineering. 2020 Jul 1;85:106682.

- Mohammed S, Sha’aban YA, Umoh IJ, Salawudeen AT, Ibn Shamsah SM. A hybrid smell agent symbiosis organism search algorithm for optimal control of microgrid operations. Plos one. 2023 Jun 7;18(6):e0286695.

- M. M. Muhammad, J. Usman, I. Mustapha, M. U. M. Bakura and A. T. Salawudeen .An independent framework for off-grid hybrid renewable energy design using optimal foraging algorithm (ofa). journal of engineering, technology & environment 2021, www.azojete.com.ng.

- Ali S, Hayat K, Hussain I, Khan A, Kim D. Optimization of Distributed Energy Resources Operation in Green Buildings Environment. Sensors. 2024 Jul 22;24(14):4742.

- Yan Cao , Hui Yao , Zhijie Wang , Kittisak Jermsittiparsert , Nasser Yousefi ,‘’Optimal Designing and Synthesis of a Hybrid PV/Fuel cell/Wind System using Meta-heuristics’’, Energy Reports 6 (2020) 1353–1362. [CrossRef]

- Xing X, Jia L. Energy management in microgrid and multi-microgrid. IET Renewable Power Generation. 2023 Oct 30.

- Chalal L, Saadane A, Rachid A. Unified Environment for Real Time Control of Hybrid Energy System Using Digital Twin and IoT Approach. Sensors. 2023 Jun 16;23(12):5646.

- Alhumade H, Rezk H, Louzazni M, Moujdin IA, Al-Shahrani S. Advanced energy management strategy of photovoltaic/PEMFC/lithium-ion batteries/supercapacitors hybrid renewable power system using white shark optimizer. Sensors. 2023 Jan 30;23(3):1534.

- Mbouteu Megaptche CA, Kim H, Musau PM, Waita S, Aduda B. Techno-Economic Comparative Analysis of Two Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems for Powering a Simulated House, including a Hydrogen Vehicle Load at Jeju Island. Energies. 2023 Nov 29;16(23):7836.

- Abdelwahab SA, El-Rifaie AM, Hegazy HY, Tolba MA, Mohamed WI, Mohamed M. Optimal Control and Optimization of Grid-Connected PV and Wind Turbine Hybrid Systems Using Electric Eel Foraging Optimization Algorithms. Sensors. 2024 Apr 7;24(7):2354.

- Ali S, Hayat K, Hussain I, Khan A, Kim D. Optimization of Distributed Energy Resources Operation in Green Buildings Environment. Sensors. 2024 Jul 22;24(14):4742.

- Rullo P, Braccia L, Luppi P, Zumoffen D, Feroldi D. Integration of sizing and energy management based on economic predictive control for standalone hybrid renewable energy systems. Renewable energy. 2019 Sep 1;140:436-51.

- Akbar Maleki . Modeling and optimum design of an off-grid PV/WT/FC/diesel hybrid system considering different fuel prices. Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies 2018, 13, 140–147.

- Maleki A, Pourfayaz F, Rosen MA. A novel framework for optimal design of hybrid renewable energy-based autonomous energy systems: A case study for Namin, Iran. Energy. 2016 Mar 1;98:168-80.

- Amoussou I, Tanyi E, Fatma L, Agajie TF, Boulkaibet I, Khezami N, Ali A, Khan B. The optimal design of a hybrid solar PV/Wind/Hydrogen/Lithium battery for the replacement of a heavy fuel oil thermal power plant. Sustainability. 2023 Jul 25;15(15):11510.

- Salawudeen AT, Mu’azu MB, Yusuf A, Adedokun AE. A Novel Smell Agent Optimization (SAO): An extensive CEC study and engineering application. Knowledge-Based Systems. 2021 Nov 28;232:107486.

- Douak M, Settou N. Techno-economical optimization of pv/wind/fuel cell hybrid system in Adrar region (Algeria). International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning. 2021 Feb;16:175-80.

- Shafiullah M, Refat AM, Haque ME, Chowdhury DM, Hossain MS, Alharbi AG, Alam MS, Ali A, Hossain S. Review of recent developments in microgrid energy management strategies. Sustainability. 2022 Nov 9;14(22):14794.

- Salawudeen AT, Mu’azu MB, Sha’aban YA, Adedokun EA. On the development of a novel smell agent optimization (SAO) for optimization problems. In2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technology and its Applications (ICTA 2018), Minna 2018 Sep 5.

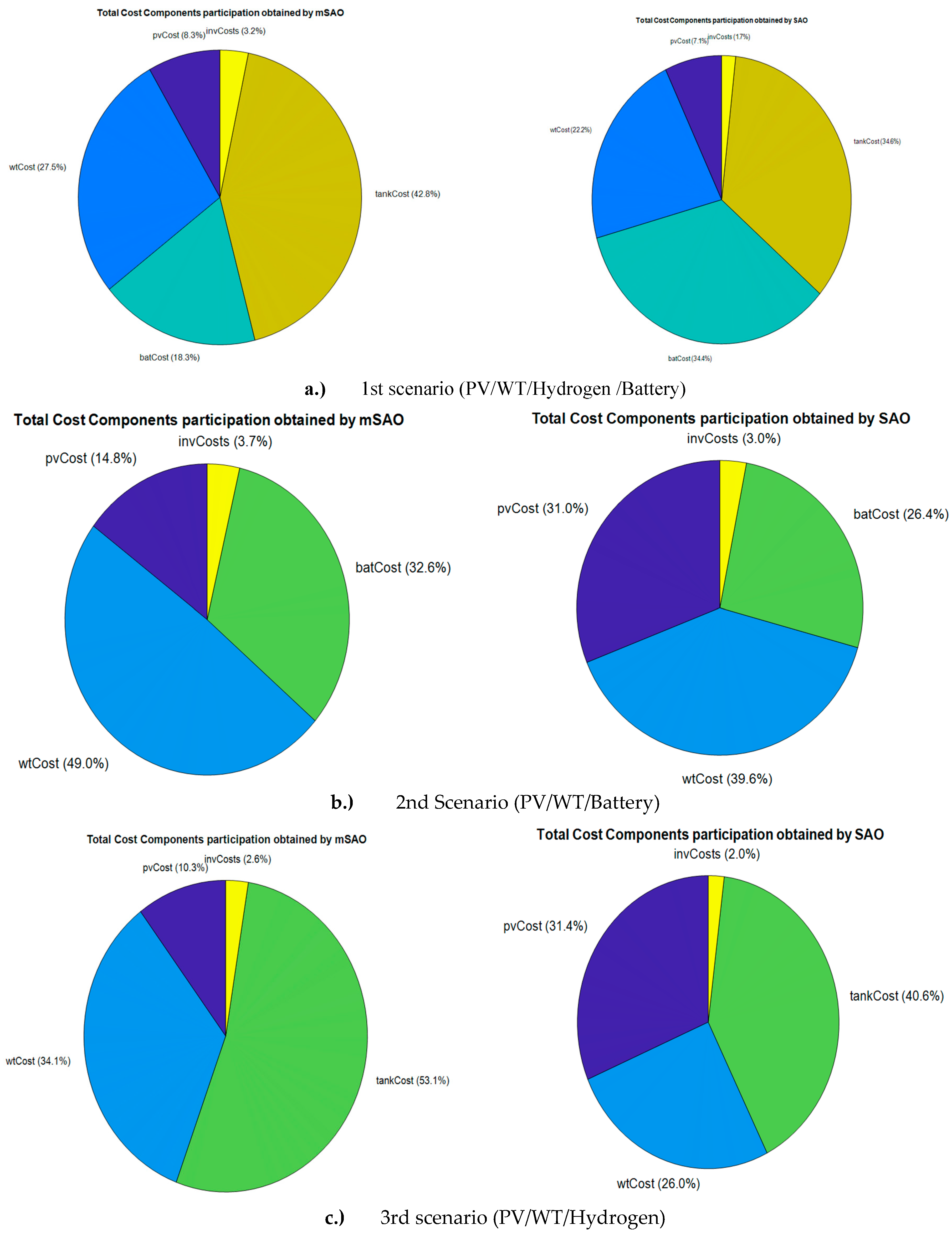

| Metrics | Scenario 1 (All Components) | Scenario 2 (No Hydrogen) | Scenario 3 (No Battery) | ||||

| SAO | mSAO | SAO | mSAO | SAO | mSAO | ||

| NPV | 8 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 20 | 5 | |

| NWT | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| NBat | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | -- | -- | |

| NTank | 3 | 2 | -- | -- | 2 | 2 | |

| NConv | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Total annual cost ($) | Best | 619464.6 | 619464.6 | 613685.5 | 613685.5 | 616910.5 | 616910.5 |

| Average | 622376.4 | 620531.7 | 615217 | 614288.8 | 618031 | 617649.1 | |

| Std | 3.568e-3 | 1.914e-3 | 1.558e-3 | 1.111e-3 | 1.446e-3 | 1.212e-3 | |

| Time (s) | 2.877019 | 4.263277 | 2.958071 | 2.854077 | 2.969879 | 2.851904 | |

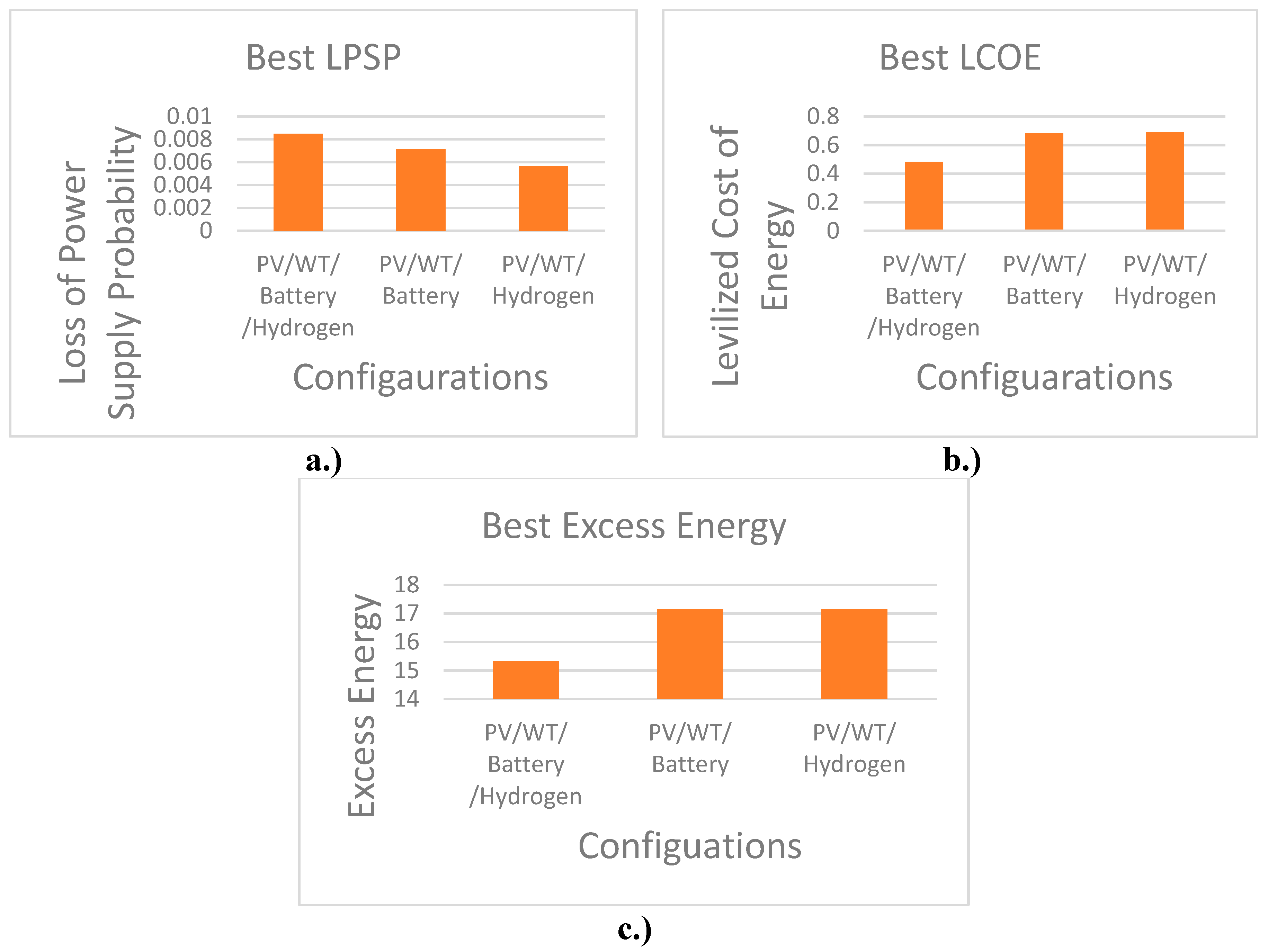

| Configuration | Index | SAO | mSAO | |

| PV/WT/ Battery /Hydrogen | LCOE | Best | 0.1845914141 | 0.4827999716 |

| Average | 0.6713710701 | 0.6985542546 | ||

| StD | 0.1153515723 | 0.5468124717 | ||

| LPSP | Best | 0.293372621 | 0.0084838478 | |

| Average | 0.380106609 | 0.0143923633 | ||

| StD | 0.0027696684 | 0.0714469320 | ||

| Excess Energy |

Best | 16.135833379 | 15.340319148 | |

| Average | 16.417603078 | 17.163953138 | ||

| StD | 2.7668380982 | 0.4253515836 | ||

| PV/WT/ Battery | LCOE |

Best | 0.3509501639 | 0.6830423606 |

| Average | 0.6868477489 | 0.7108991366 | ||

| StD | 0.0772454915 | 0.0133358999 | ||

| LPSP |

Best | 0.29337183 | 0.0071446932 | |

| Average | 0.31491137 | 0.0122269890 | ||

| StD | 7.8178237e-04 | 0.0774712029 | ||

| Excess | Best | 13.157611860 | 17.140715003 | |

| Average | 17.078775557 | 17.304232841 | ||

| StD | 0.7833305552 | 0.0774712029 | ||

| PV/WT/ Hydrogen | LCOE | Best | 0.3997548128 | 0.6866308822 |

| Average | 0.6853173504 | 0.7175898792 | ||

| StD | 0.0712544499 | 0.0098690281 | ||

| LPSP | Best | 0.29239547 | 0.0056768049 | |

| Average | 0.31260406 | 0.0104951486 | ||

| StD | 6.4520347e-04 | 0.0714469320 | ||

| Excess Energy |

Best | 14.120005570437 | 17.140715003 | |

| Average | 17.068731687154 | 17.321551245 | ||

| StD | 0.6331719103384 | 0.0567680495 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).