1. Introduction

Microalgae are mostly photoautotrophic organisms that vary in size and complexity (Castro and Huber, 2012), which constitute a highly diverse community in terms of species. The complexity of this group is related to the diversity of forms, adaptations developed for life in the pelagic environment, as well as dimensional variations (Harris et al., 2000 and references therein). In addition to being excellent bioindicators of environmental quality (Bere, 2014), these organisms, considered the main aquatic primary producers, constitute the basis of marine trophic webs governing material and energy fluxes in the ocean (Mattei et al., 2021; Sharoni and Halevy, 2022) and play an important ecological role, presenting a utmost part in the process of absorption of atmospheric carbon dioxide and thus contributing to the reduction of the "greenhouse effect" (Herrera and Fernández, 2017; Cavan and Hill, 2021).

Considering the importance of these photosynthetic microorganisms, studies have been performed aiming to explore their economic and ecological potential (Antelo et al., 2010). Among these, the food sector has gained prominence in aquaculture production, using microalgae as a raw material for the nutrition of fish, shellfish, and crustaceans (Bastos et al., 2018; Borone et al., 2018; Cardoso et al., 2019; Silva et al., 2020a). According to the FAO report (2020), global aquaculture production grew by 5.3% between 2001 and 2018, which was dominated by fish production (54.3 million tons), followed by shellfish (bivalve mollusks) with 17.7 million tons and crustaceans (9.4 million tons), which are gastronomic delicacies widely consumed around the world.

Shellfish, the second-placed in global aquaculture production, are a highly profitable category, with mussels, oysters, and scallops being the most commercialized organisms in Brazil and in the world (FAO, 2020). In addition to their economic importance, shellfish are crucial for the balance of aquatic ecosystems, as they are capable of filtering the water through their gills, "cleaning" the environment where they live (Andrade, 2016) by consuming phytoplankton (Richard et al., 2007, Fiddy et al., 2017; Porter et al., 2018) and significantly reducing their populations (top-down control). In coastal environments with intensive shellfish cultivation, these cultured organisms can account for up to 90% of total phytoplankton consumption (Han et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2022).

In this way, shellfish that feed on suspended particles have developed strategies to control the food ingestion process, managing the quantity and nutritive value of the consumed particles, thus optimizing energy gain (Espinosa et al., 2007). Their main source of food is microalgae, especially during larval and juvenile stages (Sipaúba-Tavares and Rocha, 2003), as they are generally rich in macro and micronutrients, bioactive compounds such as amino acids, proteins, lipids, structural and non-structural carbohydrates, minerals, vitamins, antioxidants, and pigments (Batista et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2014; Bennamoun et al., 2015; Cheng et al., 2020), which present the nutritional requirements of different shellfish species.

Among the various phyla that include microalgae, Bacillariophyta (diatoms) can be considered the main food source for filter feeders of the genus Crassostrea, representing about 81% of their diet (Christo et al., 2015). Oysters belonging to this genus are widely commercialized in Brazil, especially in the southern region, and are responsible for the country's highest production of Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg, 1793) (IBGE, 2020).

Unlike the southern region of Brazil, in the northern region, the oyster Crassostrea gasar (Adanson, 1757) is mostly produced through cultivation (Silva et al., 2020b). This species can be found along the Brazilian coast, occurring naturally in estuarine environments and mangrove regions, where they attach themselves to mangrove roots or rocks (Varela et al., 2007; Melo et al., 2010). They are considered euryhaline and eurythermal, and oysters of this genus have a promial chamber that inverts the excurrent water flow from inside the body, which is an adaptation for survival in high-turbidity environments (Galvão et al., 2000), a common characteristic of some Amazonian estuaries (Andrade et al., 2016; Barros et al., 2019; Santos et al., 2020), which makes the development of this species successful in the estuaries of Pará, the main oyster producers in the northern region of Brazil (IBGE, 2020).

The state of Pará has five oyster farms located in the municipalities of Salinópolis, São Caetano de Odivelas, Curuçá, Maracanã, and Augusto Corrêa (Sampaio et al., 2019). Among them, the oyster farming in the municipality of Augusto Corrêa highlight as the most productive, obtaining a profit of around US$ 182,453. 00 (1 US$ dollar = 5.30 R$ Brazilian Real; March 24, 2023) between 2014 and 2019 (IBGE, 2020). The oyster farming in Augusto Corrêa is located in the estuary of the Emboraí Velho River, in the community of Nova Olinda. This estuary is considered a suitable environment for the growth and fattening of oysters, as it presents a set of hydrobiological aspects - salinity, pH, dissolved nutrients, and phytoplankton biomass - favorable for the success of local production (Barros et al., 2019; Sampaio et al., 2019; Reis et al., 2020a). In this community, oyster farming generates income and supports the livelihoods of several families, representing a viable alternative for fishermen and family farmers in the region willing to expand their productive/economic activities (Macedo et al., 2020; Reis et al., 2020a).

Considering the ecological and socioeconomic importance of oysters cultivated in the estuary of the Emboraí Velho River, several studies have been conducted in recent years with the aim of understanding the growth profile, ecology, and reproductive biology of Crassostrea gasar, as well as others focused on socio-environmental and socio-economic analyses (Sampaio et al., 2019; Macedo et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2020a and 2020b; Reis et al., 2020a and 2020b). However, studies developed to obtain information on the feeding biology of these filter-feeding animals cultivated in the Augusto Corrêa oyster farming area are not yet available in the literature. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the diet of oysters cultivated in this environment, focusing on the analysis of microalgae belonging to the diatom group, as they comprise the major part of the food of these organisms, provide bioactive compounds necessary for their development, and have siliceous valves that resist the action of gastric acids even after digestion of the cellular organic material, which facilitates their identification among the residues present in the stomach contents. Additional hydrological determinations (temperature, salinity, dissolved nutrients, etc.), as well as taxonomic and ecological studies on the diatom flora of the Emboraí Velho River estuary were also conducted for comparative purposes. This allowed us to test the hypothesis that locally cultivated oysters feed selectively on organisms of the group based on preferences governed by selection processes described in the literature for other shellfish species.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

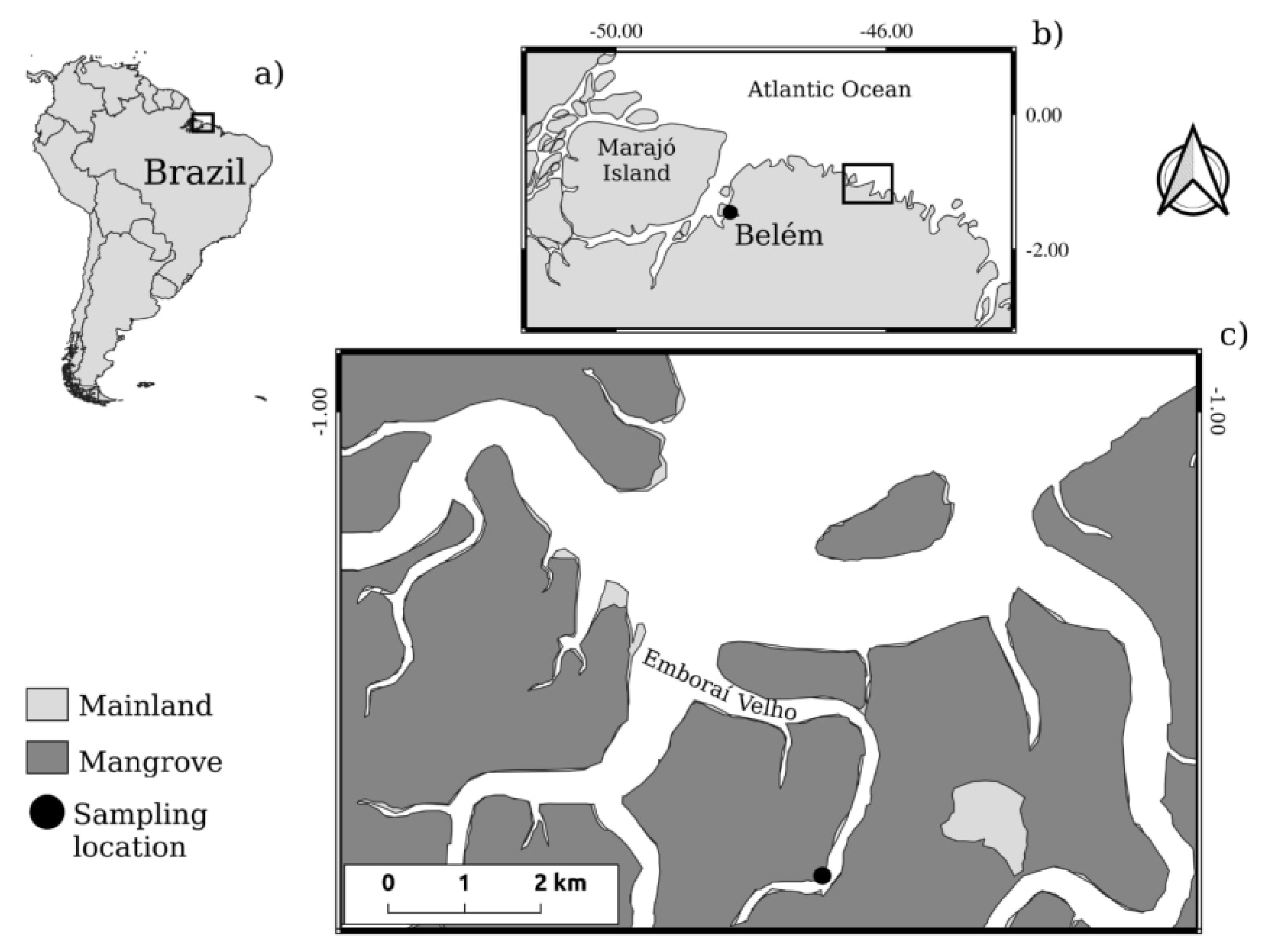

The estuary of the Emboraí Velho River (0° 52' 54” S and 46° 26' 54” W;

Figure 1) is located in the village of Nova Olinda, about 36 km from the municipality of Augusto Corrêa, which belongs to the system of mangroves on the Urumajó Coast, showing a hydrography with wide coastal bays (Sousa et al., 2013). This estuary is located in an “Área de Proteção Ambiental (APA)” (Environmental Protection Area), the Araí-Peroba Extractive Reserve (MMA, 2019).

The climate in this region is equatorial hot and humid, with a minimum air temperature of 19°C and a maximum of 27°C, with annual rainfall ranging from 2,500 to 3,000 mm, relative air humidity ranging from 70% to 97% and average wind speed around 0.8 m s-1 (averages of the last 40 years; INMET, 2020). Semidiurnal macro tides are typical in the northeast region of Pará, with a variation of 5-6 m during spring tide and 3.5-4.5 m during neap tide (Barbosa et al., 2015).

The Emboraí Estuary is considered shallow, with an average depth of approximately 5 meters. Although it shows high turbidities (= 409.2 UNT; Sousa et al., 2013), it is considered a productive estuary in terms of chlorophyll-a concentrations (maximum around 15.04 ± 6.21 mg m-3), also presenting high phytoplanktonic abundances (Barros et al., 2019).

2.2. Climatology

The historical average rainfall values for the last 40 years (1978-2018), as well as for the study year (2019), were obtained from the National Institute of Meteorology of Pará (INMET-PA), from the Tracuateua-Pará meteorological station (01º 04' 00" S and 46º 54' 00" W), situated 60 km from Nova Olinda Village.

2.3. Field Procedures

The campaigns were performed in April and June (rainy season), and September and December 2019 (dry season), at a fixed station (1º 03' 16.37" S and 46º 26' 51.14" W) located in the oyster farming area of the Emboraí Estuary, during spring tides.

2.3.1. Oyster Collection for Gut Content Studies

The oysters used for this study were collected in the suspended table cultivation area during low tide, when the individuals are commonly exposed. A total of 15 specimens of the species Crassostrea gasar were collected per campaign, totaling 60 samples. The selected individuals had average heights of 94 ± 4.1 mm and widths of 64 ± 0.8 mm and were classified as medium-sized oysters (80-99 mm), which are widely commercialized in the region (Sampaio et al., 2019). All collected organisms were measured using an analog caliper (Vonder, 150 mm).

After collection from the cultivation area and the development of the necessary measurements, all the body tissues of the mollusks were removed from inside their shells and stored in 100 ml plastic containers filled with 4% formalin solution (neutralized with borax) to preserve the integrity of the samples during transportation to the laboratory, where analyses of all the collected material were subsequently performed.

2.3.2. Estuarine Diatoms

For comparative purposes between the diatoms found in the oyster’s gut content and those identified in the estuarine cultivation area, samples were collected every 3 hours in a nychthemeral cycle, in the subsurface of the water column (~1m), through a Niskin oceanographic bottle (3 L). After each collection, the samples were placed in properly labeled 600 ml plastic containers and immediately fixed with Lugol's solution (Potassium Iodide – 1%), in a volume of 1 ml of fixative for 100 ml of the sample.

2.3.3. Hydrological Variables and Phytoplanktonic Biomass (Chlorophyll-a)

In order to complement this study, Hydrological (physical and chemical variables) and phytoplanktonic biomass data were obtained simultaneously with diatom identification studies. Water temperature, salinity and turbidity were recorded in situ with the aid of CTDO (model XR-420) coupled with a turbidity sensor, while for the other hydrological variables (pH, concentrations of dissolved nutrients - nitrate-NO3-, nitrite -NO2-, orthophosphate-PO₄³⁻ and silicate-SiO2), as well as for chlorophyll-a concentrations, additional subsurface water samples (~1m) were collected using Niskin bottles. The collected samples were stored in plastic flasks of 600 ml, previously acidified, and then placed in a container with ice for further analysis in the laboratory.

2.4. Laboratory Procedures

2.4.1. Analysis of the Gut Contents of Oysters

The digestive tract of the collected oysters was extracted from the inside of the body of the mollusks with the aid of a Zeiss stereo microscope (Stemi 2000), through a lateral incision with a scalpel blade to remove its content. After removing the gut contents, the material was stored in 100 ml plastic containers and preserved in neutralized formaldehyde.

Afterwards, the tissue bleaching process was performed, immersing them in sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) for 24 hours. At the end of this process, the NaClO residues from the samples were removed by washing them 3 times with distilled water, and from then on, the next step began - the acidic degradation of the organic matter.

For the degradation of the organic matter of the gut contents, adaptations of the methods (Supplementary material SI) described by Christensen (1988), Hasle and Fryxell (1970) and Simonsen (1974) were used. This cleaning process is suitable for the diatom groups, since, due to the siliceous composition of their valves, they are resistant to the action of the acids used.

For the latter process, sulfuric (H2SO4), hydrochloric (HCl) and oxalic (C2H2O4) acids, and potassium permanganate (KMnO4) were manipulated in a fume hood. The KMnO4 and C2H2O4 crystals were weighed on a precision scale and then diluted. After preparing the solutions, they were added to each sample using the protocol presented in the supplementary material (SI).

After this procedure, the samples were used to the preparation of permanent slides according to Müller-Melchers and Ferrando (1956). A heated metal plate was employed for samples evaporation of the residual water, obtaining only the valves of the diatoms on the coverslip. Subsequently, Naphrax (High Resolution, Diatom Mountant) was used to fix the coverslip on the slide in order to promote adhesion between them. Through these slides, called permanent slides, it was possible to identify the diatoms present in the samples through their morphological structures, since the frustules were free of organic matter.

2.4.2. Analysis of the Diatoms of the Estuary

To determine the composition and abundance (number of cells L-1) of the estuarine diatoms, qualitative and quantitative analyses were performed. For this last analysis, 7 ml aliquots were prepared following the Utermöhl sedimentation method (Utermöhl, 1958).

After the sedimentation process (24 hour), the taxa were identified and counted in the entire chamber using a binocular inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Axiovert), with a magnification of 400x.

Classification of the taxa identified from the samples extracted from the guts of the oysters, as well as from the samples obtained from the water column of the estuary, was determined according to Round et al. (1990), Hasle et al. (1996), Tomas (1997), Cupp (1943) and Silva-Cunha (1990). The ecological classification of the species was based on the studies of Moreira Filho et al. (1990), Moreira et al. (1994) and Souza-Mosimann (2001). The taxonomic nomenclatures of the identified species were confirmed from the international database ALGAEBASE (

www.algaebase.org; Guiry and Guiry, 2021).

2.4.3. Hydrological Variables and Phytoplanktonic Biomass

In the laboratory, the pH values were determined using a Hanna electronic pH meter (HI 2221). Dissolved nutrients (NO3-, NO2-, PO₄³⁻ and SiO2) were analysed according to the methods described by Strickland and Parsons (1972) and Grasshoff et al. (1983). For the analysis of chlorophyll-a concentrations, aliquots of 300 ml of water were filtered using a vacuum pump and glass fiber filters (Machery-Nagel GF 1 0.7 µm, 47 mm). After filtration, the filters were placed in aluminum foil envelopes, duly labeled, and stored in a freezer until the moment of analysis. The determination of chlorophyll-a concentrations was performed spectrophotometrically according to the method described by Parsons and Strickland (1963) and UNESCO (1966).

2.5. Data Processing

After the end of the laboratory analyses, density, relative abundance (RA) and frequency of occurrence (FO) of the identified species were calculated. Relative abundance was calculated according the following equation: RA = (n x 100) / N (Koening and Lira, 2005), where: “n” represents the number of organisms of a particular species in a sample, and “N” represents the total number of species found in the sample. The result was expressed as a percentage, considering the categories: dominant (> 70%), abundant (≤ 70% and > 40%), not very abundant (≤ 40% and > 10%) and rare (≤ 10%). The frequency of occurrence of taxa was calculated using the equation: FO = (p x 100) / P, where “p” is the number of samples containing a particular species; and “P” the total number of samples analyzed (Mateucci and Colma, 1982). For FO, the following categories were established: very frequent (≥ 75 %), frequent (< 75% and ≥ 50%), infrequent (< 50% and ≥ 25%) and sporadic (< 25%).

Based on the values obtained, assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were tested for both abiotic and biological data, using the Lilliefors (Conover, 1998) and Cochran (Underwood, 1997) tests, respectively. For variables considered non-normal, log transformation (x+1) was used to obtain distributions close to normality. For data with homogeneous variances, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied, followed by the HSD Tukey post-hoc test when significant differences (p<0.05) were observed between the studied variables. However, for non-homogeneous variables, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney (U) and/or Kruskal-Wallis (H) tests were applied (Zar, 1999). All analyses were performed with the aid of the STATISTICA 8.0 program. Hierarchical agglomerative analysis of similarity (Cluster Analysis) was used to investigate similarities among the samples, based on the Bray–Curtis similarity index and fourth root transformed density data, and run in the PRIMER statistical package, version 6.1.6 (Clarke and Warwick 1994). A SIMPER (Similarity/distance percentages) analysis was conducted to identify the species that had the greatest influence on the formation of groups in the cluster analysis. Additionally, a similarity analysis (ANOSIM) was employed to assess the statistical significance of the differences observed between the groups identified in the dendrogram. Both of these analyses were performed using PRIMER 6.1.6.

3. Results

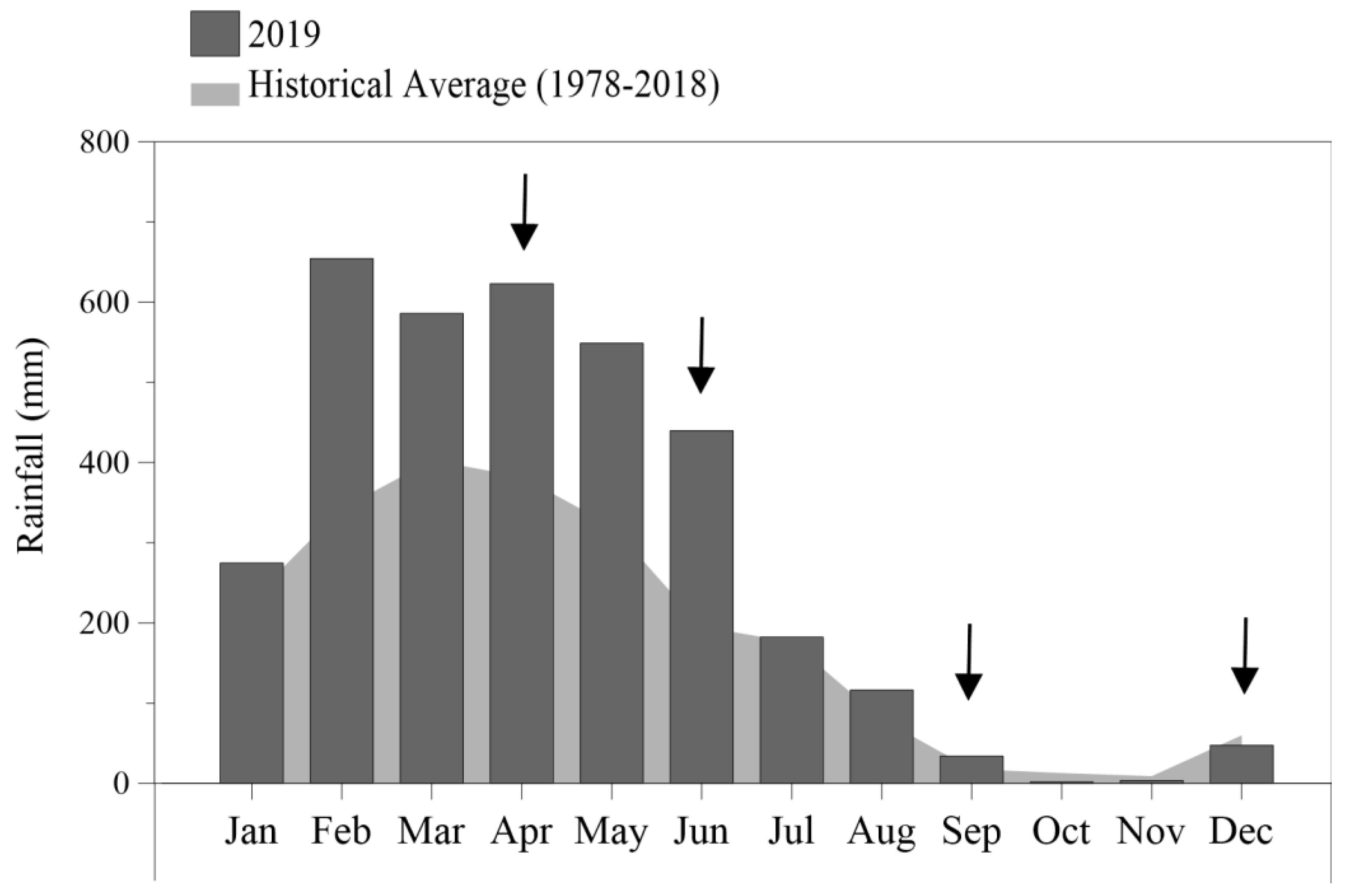

3.1. Rainfall

The rainfall records of the last 40 years (1978-2018), as well as the year of study (2019), showed a well-defined seasonality, with a period of higher rainfall incidence in the first semester (January to July) and a less rainy period in the second semester (August to December). Analyzing the values obtained by the historical average, variations from 8.9 mm in November to 402.9 mm in March were observed. Among the months of collection, September had the lowest precipitation values (34 mm), while in April maximum values of 623.2 mm were observed. During the year of study, rainfall values above the historical average (52%) were recorded, as shown in

Figure 2. However, large-scale atmospheric events such as La Niña, have not been confirmed according to publicly available NOAA (2023) data.

3.2. Biological Variables

3.2.1. Diatom Flora in Oyster Gut Contents

The diatoms that were part of the diet of the oysters analyzed during this study were comprised of 61 taxa, of which 37.70% were centric and 62,30% pennate diatoms. The identified taxa were distributed in 2 subphyla, 3 classes, 8 subclasses, 22 orders, 4 suborders, 35 families, 40 genera, 45 species, and 16 morpho-species (Supplementary material SII).

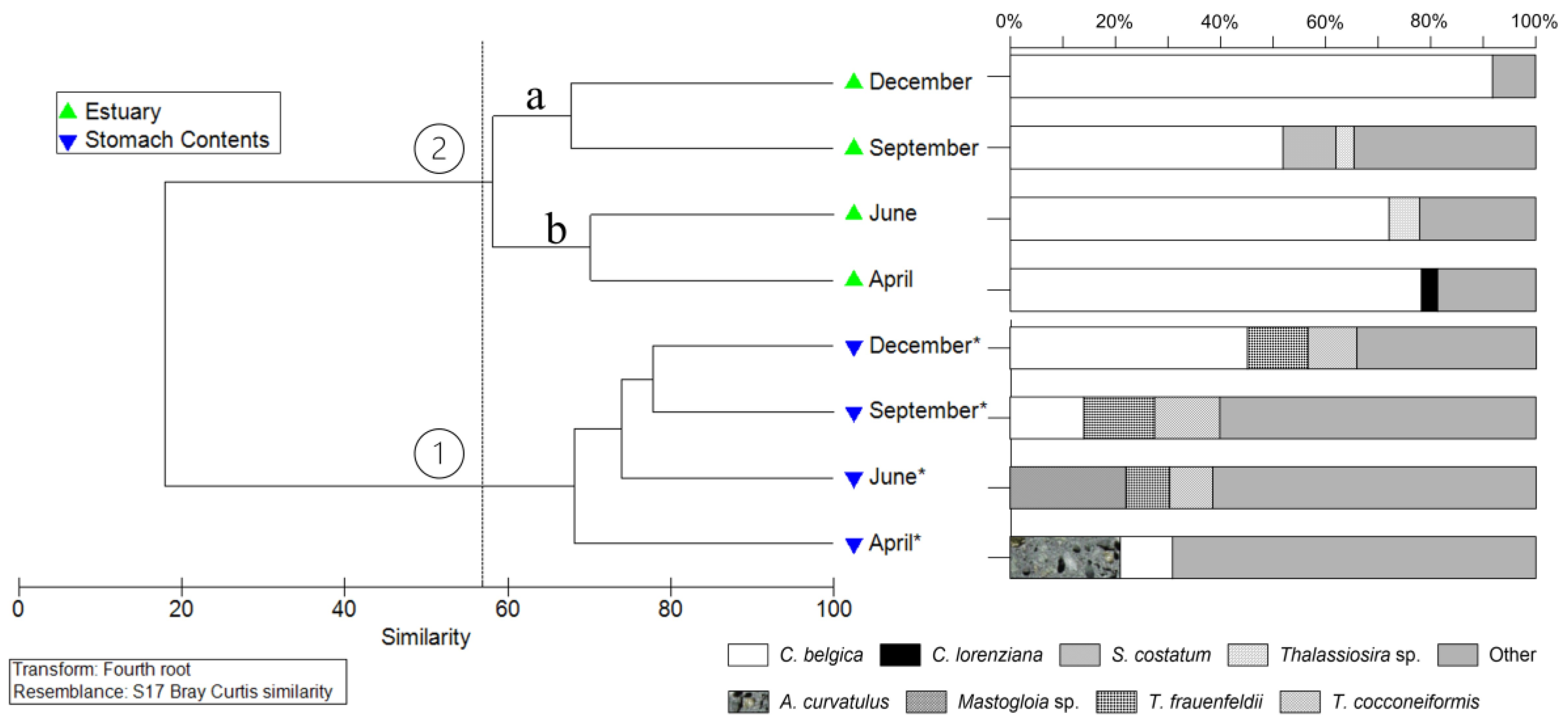

The species

Cymatosira belgica Grunow was the most representative in the analysis of the gut samples, with relative abundances of 13.9% in September and 45.1% in December. Conversely, the maximum relative abundances (

Figure 3) recorded among the less abundant taxa were 20.90% for

Actinocyclus curvatulus Janisch (April), 14.7% for

Thalassiosira sp. (April), 13.4% for

Thalassionema frauenfeldii Grunow (September) and 12.5% for

Tryblioptychus cocconeiformis Grunow (September). These, as well as other taxa considered less representative during the study period, are listed in supplementary material SII.

Cymatosira belgica, Thalassiosira sp., Tryblioptychus cocconeiformis, and Cyclotella litoralis Lange & Syvertsen were very frequent (species with frequencies >70%; See Mateucci and Colma, 1982) throughout the study period. In this same category were included Thalassionema frauenfeldii in June, September, and December, while Navicula sp. during the months of April, June, and September. Cocconeis sp., as well as Nitzschia rigida M. Peragallo during the months of June and September. The species Tryblionella granulata Grunow, in turn, was considered very frequent in April and September. Actinocyclus curvatulus M. Peragallo, in the months of April and June, Psammodictyon panduriforme W. Gregory, Thalassionema nitzschioides, and Diploneis bombus Ehrenberg, in the month of September, showed a similar pattern. Mastogloia sp. and Gyrosigma balticum Ehrenberg were a very frequent taxa in the month of June. The other identified taxa, which were considered frequent or sporadic, are listed, together with the organisms previously mentioned, in supplementary material SII.

3.2.2. Diatoms of the Emboraí Estuary

In the estuarine water samples collected during the present study, 123 taxa belonging to the diatoms group were recorded, which were distributed in 2 subphyla, 3 classes, 8 subclasses, 26 orders, 4 suborders, 42 families, 65 genera, 81 species and 42 morpho-species (Supplementary material SIII). Of these, 35.77% consisted of centric diatoms and 64.23% of pennate diatoms.

The species

Cymatosira belgica was present in all analyzed samples, representing a dominant species (> 70%) throughout the study period, except in September. Its relative abundance was 78.20% in April, 72.10% in June, 51.90% in September and 91.80% in December (

Figure 3). Due to the dominance of this species, the other identified taxa reached low values of relative abundance, being considered rare. Recorded taxa are shown in supplementary material SIII.

Among the organisms identified Cymatosira belgica, Thalassiosira sp., Thalassionema nitzschioides, Paralia sulcata Ehrenberg, Cymatosira lorenziana Grunow, Navicula delicatula Cleve were very frequent (>70%) throughout the study period. Thalassionema frauenfeldii and Campylodiscus sp. were included in this category during the months of June, September and December. The morphospecies Navicula sp.1 and the species Diploneis bombus were among the most frequent organisms during the months of April, June and December (Supplementary material SIII). Tryblionella granulata Grunow and Nitzschia sp.1 displayed a similar trend during the rainy season (April and June), whereas Thalassiosira subtilis Ostenfeld and Skeletonema costatum Cleve, in the dry period (September and December). The species identified in the months of study are listed in supplementary material SIII.

Cluster Analysis based on density of species from gut content and estuarine ecosystem (

Figure 3) showed the formation of two well separated groups at a level of 57% similarity (global ANOSIM R = 0.967, p <0.05). The first group (group 1) was represented by samples obtained from the gut content of

C. gasar with similarity of 71.5%. This group presented the highest density of

C. belgica (December),

A. curvatulus (April) and

Mastogloia sp. (June) and lower densities of

T. frauenfeldii and

T. cocconeiformis in June.

Nitzschia obtusa,

Nitzschia sp.1, and

Cyclotella littoralis (SIMPER (Sim/SD) = 18.7; 17.1; 15.3, respectively) were the main species responsible for the formation of this clade.

With a similarity of 61,8%, the second group (group 2) was comprised by samples collected from the estuarine environment. In addition, it was also possible to verify a marked seasonality in the estuarine system, since samples from the dry period (September and December) grouped separated (2a) from those from the rainy period (2b; April and June). Species such as Navicula delicatula (SIMPER (Sim/SD) = 14.3), Cymatosira belgica (SIMPER (Sim/SD) = 13.6) and Ditylum brightwellii (SIMPER (Sim/SD) = 13.5) significantly influenced the composition and structure of this group.

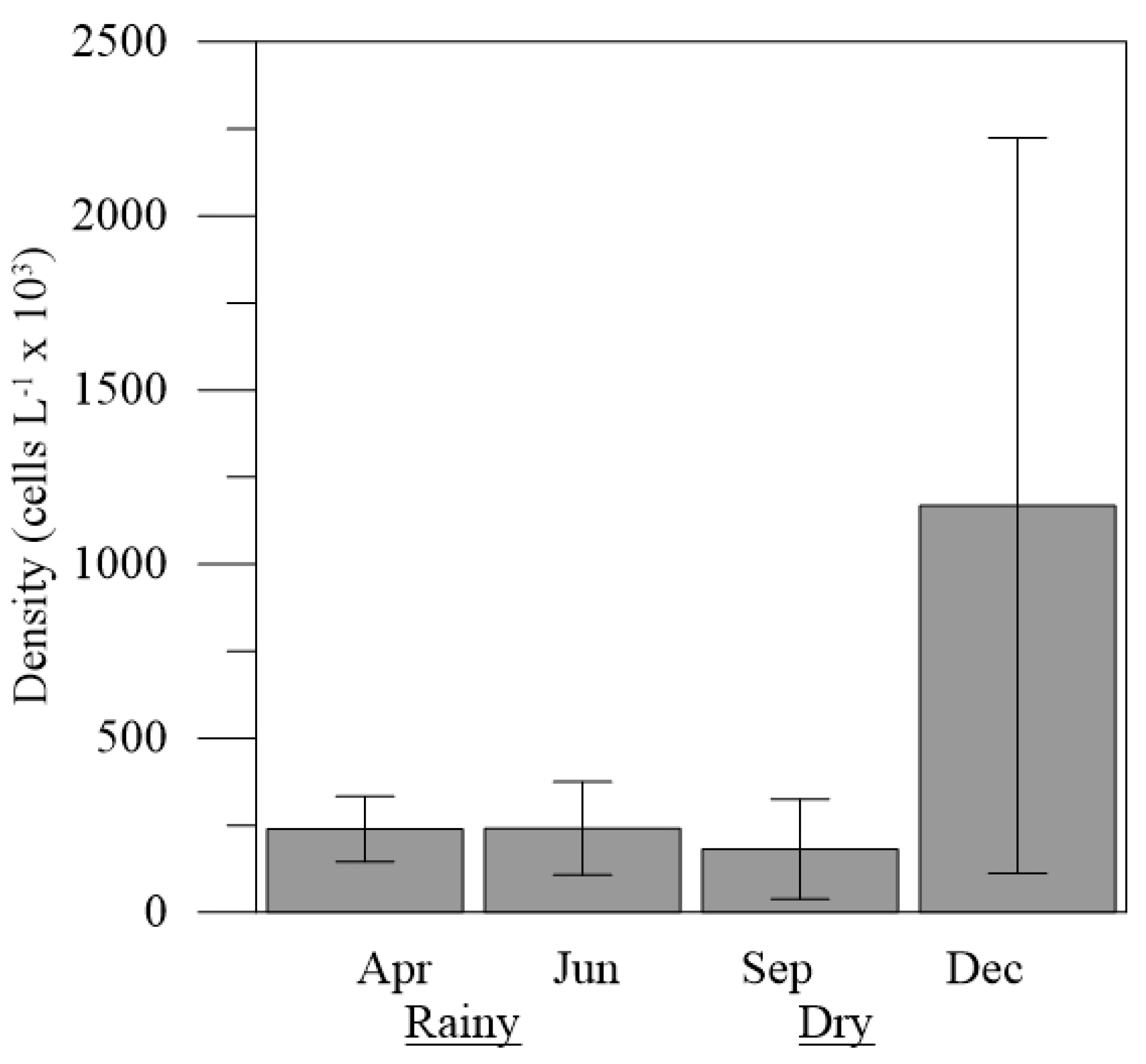

The total density of the diatoms identified in the samples from the Emboraí Estuary showed averages that varied between 181.57±135.23 x 10

3 cells L

-1 (September) and 1,167.70±995.63 x 10

3 cells L

-1 (December), with values significantly higher observed in December (H = 4.35; p<0.05;

Figure 4).

3.3. Hydrological Variables and Phytoplankton Biomass (Chlorophyll-a)

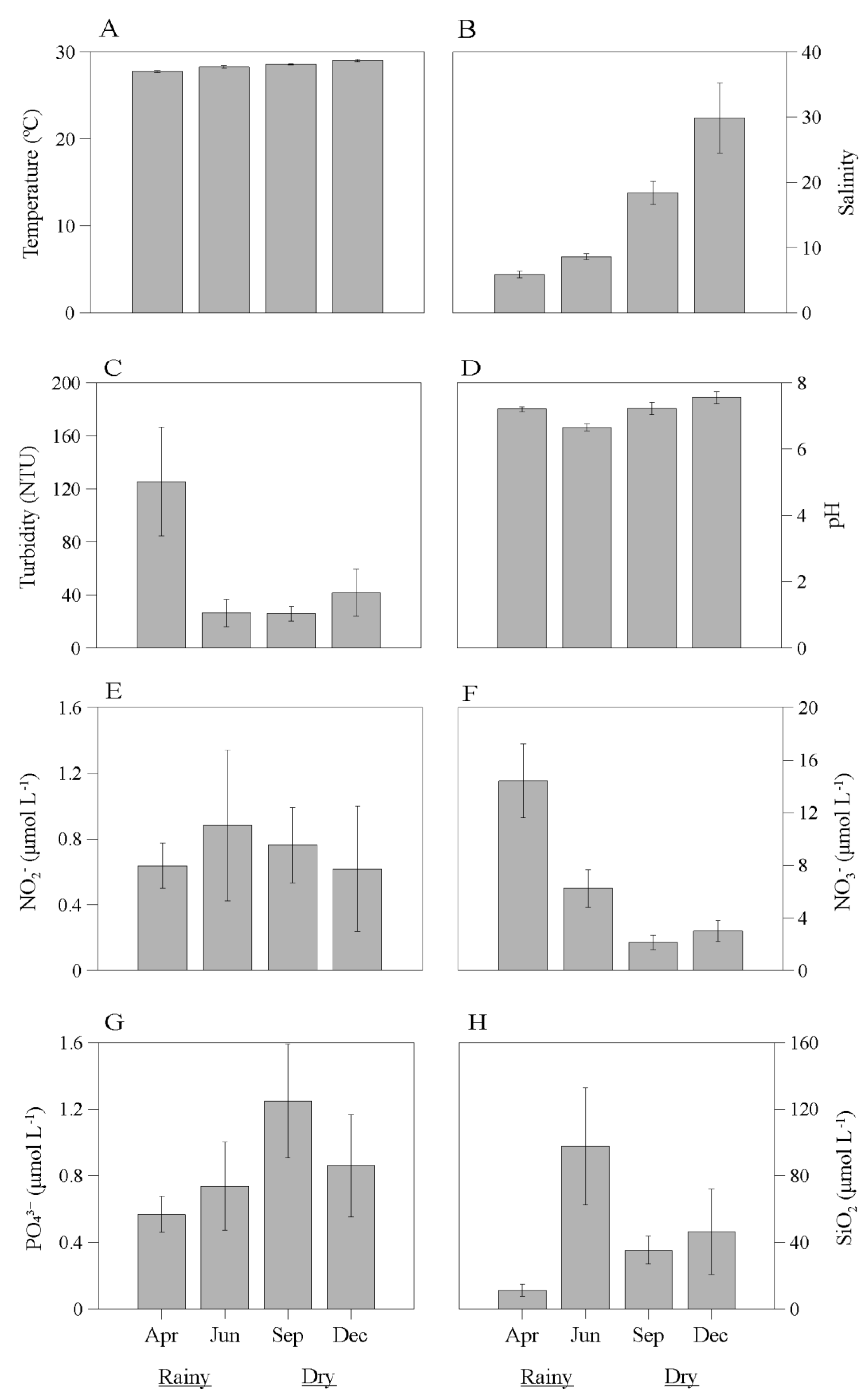

Water temperature showed mean values ranging from 27.7 ± 0.1 ºC (April) to 29 ± 0.1 ºC (December), with significantly higher values observed for the latter month (H = 31.66; p<0.05) (

Figure 5A). Salinity values showed monthly differences, with significantly higher values in December (F = 116.01; p<0.05), and mean values ranging from 5.9 ± 0.5 (April) to 29.9 ± 5.4 (December). Significant seasonal differences were also observed, with higher salinities recorded in the dry season (F = 91.96; p<0.05) (

Figure 5B).

Water turbidity had averages ranging from 25.8 ± 5.6 (September) to 125.6 ± 41.2 (April), with more turbid waters recorded in April (F = 5.56; p<0.05) (

Figure 5C). The pH ranged from slightly acidic to alkaline, with significant differences and higher values (H = 27.34; p<0.05) in December, with mean values ranging from 6.7 ± 0.1 (June) to 7.6 ± 0.2 (December) (

Figure 5D).

Nitrite concentrations were higher in June (H = 2.93; p<0.05) and had mean values ranging from 0.62 ± 0.38 μmol L

-1 (December) to 0.88 ± 0.46 μmol L

-1 (June) (

Figure 5E). Nitrate concentrations, in turn, were significantly higher in April (F = 109.39; p<0.05), with average values ranging from 2.1 ± 0.5 μmol L

-1 (September) to 14.4 ± 2.8 μmol L

-1 (April). Significant seasonal differences were also recorded for this variable, with higher values during the rainy season (F = 86.92; p<0.05) (

Figure 5F).

Mean orthophosphate concentrations ranged from 0.57 ± 0.11 μmol L

-1 (April) to 1.25 ± 0.34 μmol L

-1 (September), with significantly higher values observed in September (F = 9.16; p<0.05) and during the dry season (F = 14.33; p<0.05) (

Figure 5G). In June, the highest silicate concentrations were registered (F = 23.18; p<0.05). Mean values for this nutrient ranged from 11.2 ± 3.6 μmol L

-1 (April) to 97.6 ± 35.2 μmol L

-1 (June).

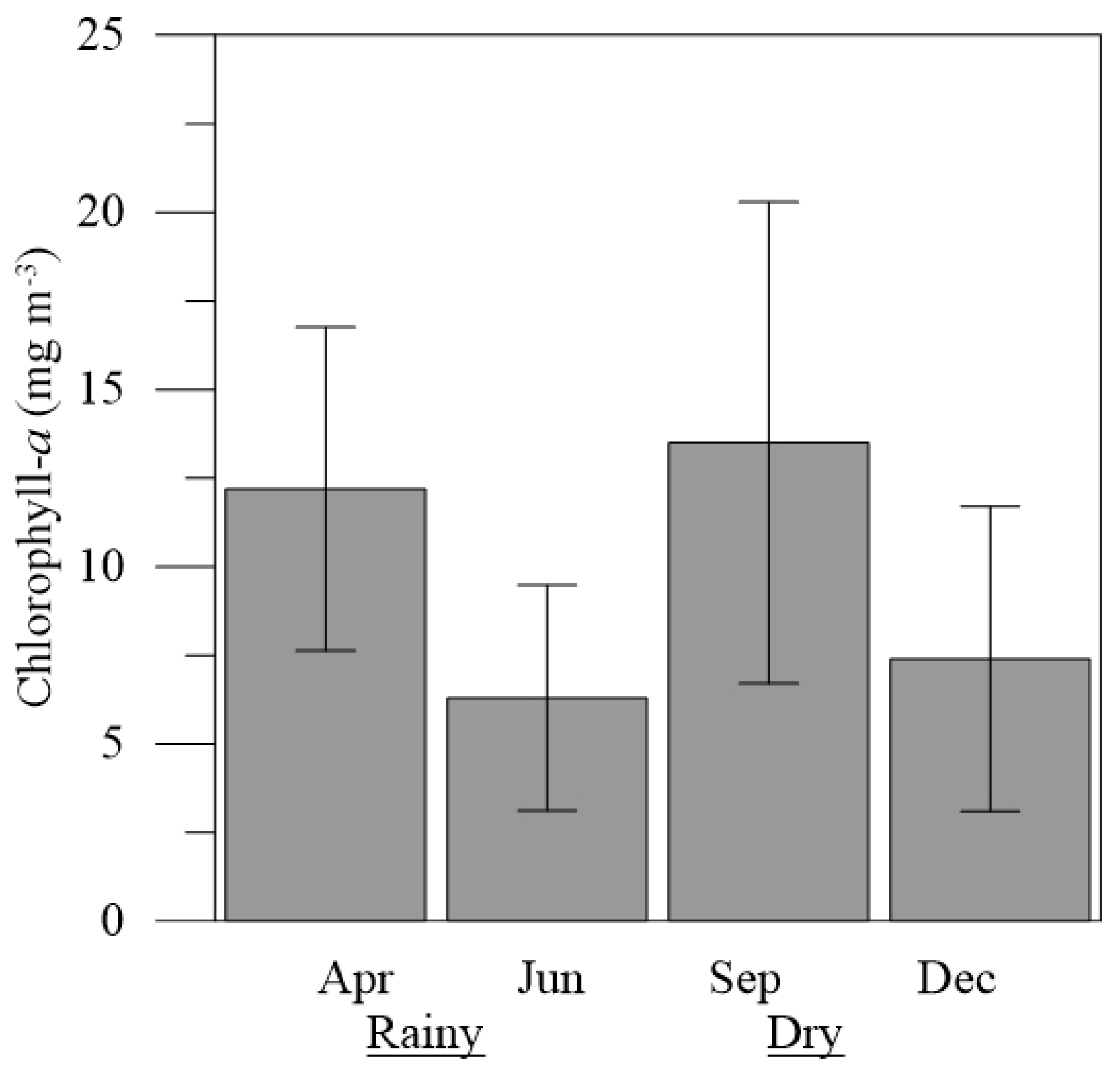

Chlorophyll-

a concentrations showed averages ranging from 6.3 ± 3.2 mg m

-3 (June) to 13.5 ± 6.8 mg m

-3 (September), the latter being significantly higher than those recorded in the other months studied (H = 9.36; p<0.05) (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

The rainfall regime showed a well-defined seasonality, with the fluctuations of hydrological variables such as temperature, salinity, turbidity, pH, and dissolved nutrients strongly influenced by climatological dynamics in the estuaries of the Pará coast. Previous studies conducted in the northern region of Brazil (Andrade et al., 2016; Souza et al., 2019; Santos et al., 2020), as well as in the estuary under study (Barros et al., 2019), also showed this same pattern (strong seasonal variations), demonstrating the importance of this variable on the local phytoplanktonic dynamics (Oliveira et al., 2022). Other factors such as marine currents, tidal regimes, and river input are also considered determinants for the distribution of the biota in these Amazonian coastal ecosystems (Magalhães et al., 2013; Abreu et al., 2017; Costa et al., 2018; Souza et al., 2019; Santos et al., 2020).

The results obtained demonstrated that Cymatosira belgica contributed significantly to the oysters' food composition, as evidenced by the abundance analysis (Supplementary material II), which showed that it was the most abundant and one of the most frequent species in the studied stomachs during the dry period (September and December). The dissimilarity in the composition of diatom flora in the estuarine waters and the stomach contents of the studied oysters also demonstrated both their ability to remove large amounts of phytoplankton from the environment, and to select particles of different sizes, weights, and chemical compositions (Jones et al., 2002; Adite et al., 2013; Costa et al., 2021).

Feeding experiments indicate that oyster larvae (Crassostrea virginica) exhibit a preference for small phytoplanktonic organisms over their larger counterparts in natural estuarine communities. However, within the small phytoplankton fraction (<10 µm), there appears to be minimal selective behavior (Fritz et al., 1984). For C. gigas in turn, picoplankton (<5 µm), seems not to represent a valuable trophic resource due to its poor carbon resource (Dupuy et al., 2000), the same being observed for C. virginica in regard to picocyanobacteria (Weissberger and Glibert, 2021). The studies of Cognie et al., (2001), conversely, showed that for C. gigas preferences can include a range of size with larvae consuming mainly the small and the largest available cells. Nevertheless, the size and shape of the cells apparently do not seem to explain the selective behavior observed. According to these last authors, despite unchanged retention rates, filtration altered assemblage composition, revealing the intricate feeding dynamics in oyster ecosystems.

Other studies confirm the effect of top-down control of phytoplankton by oysters in many in subtropical and tropical estuaries worldwide (Porter et al. 2018; Jiang et al., 2019; Pan et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2022 and references therein), however, the limits of this control were and are still debatable for a long time (Pomeroy et al., 2006). According to Li et al., (2012), phytoplankton removal by Crassostrea virginica oyster nursery in a natural ecosystem can vary on short- (minutes to hours) to long-term (seasonal) timescales, depending on oyster responses to environmental variation, such as diurnal temperature and dissolved oxygen cycles, wind-driven turbulence, and the presence of harmful algae. However, overall, oyster nurseries appear not have a large impact on the abundance of phytoplankton in the water.

The analyzed oysters were collected from suspended cultivation structures, and it is suggested that the considerable relative abundance and frequency of occurrence of benthic diatoms (tychoplankton) of the genera Actinocyclus, Cocconeis, Cyclotella, Cymatosira, Diploneis, Navicula, and Tryblioptychus in the stomach contents (Supplementary material II) is due to the sediment resuspension processes from the bottom to the surface. The resuspension of benthic organisms was also recorded by other authors in estuarine waters of other Amazon coastal environments (Matos et al., 2011, 2012, 2016; Cavalcanti et al., 2018), corroborating this result and demonstrating the importance of high local hydrodynamics on the sediment-water column interactions and on the organisms that inhabit these ecosystems (Oliveira et al., 2022; Oliveira et al., 2023). The occurrence of species from these genera was recorded by other authors in the stomach contents of shellfish (Muñetón-Gómez et al., 2010; Dué et al., 2012; Christos et al., 2015; Estrada-Gutiérrez et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2023), thus demonstrating their nutritional importance for these filter-feeding animals.

The species C. belgica (benthic marine diatom) considered in the present study as the main food source for oysters, is a species capable of forming filamentous colonies of rectangular cells and has small spines in its morphological structure (Garcia, 2016; Guiry and Guiry, 2021). Recognized as a cosmopolitan species, it prefers sandy and muddy environments and occasionally occurs in the plankton (Tomas, 1997). The morphological characteristics of this species can be an important factor for the feeding of oysters, as their cells have small dimensions (Garcia, 2016) and do not present structures such as setae and prominent spines, which are harmful and interfere negatively in the ingestion and absorption of cells by these filter organisms (Affe and Santana, 2016). Actinocyclus curvalatus was the second most abundant in gut content of C. gasar in April (rainy period). Species of this genus are small in size and characterized morphologically by the absence marginal siliceous spines (Belcher and Swale, 1979), inhibiting sediment surrounds of freshwater (Idei et al., 2012), brackish and marine environments (WoRMS, 2020). These morphological and ecological features may have favored its ingestion during the rainy season, a period of greater resuspension of sediments and associated epibenthic diatoms.

The morphospecies Thalassiosira sp. was the third most abundant, being present in all stomachs analyzed, as well as in samples collected in the estuary. Species of this genus are typical of marine waters, with at least 12 species found in freshwater environments (Moreira Filho et al., 1990, Guiry and Guiry, 2021). However, although the identification of organisms of this species is often associated with the need to use scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the identified species may possibly come from coastal waters, since the waters in the studied environment ranged from mesohaline (5.0-18.0) to polyhaline (18.0-30.0) during the study period (see Montagna et al., 2013). The organisms of this genus reached higher relative abundances during the rainy months, suggesting a greater contribution of euryahline species in this period. The greater availability of silicate, nitrite and nitrate in the rainy season may also have favored their development and, consequently, their high density. Thalassiosira is a genus of centric, cosmopolitan diatoms, consisting of discoid, solitary or colonial cells held together by valves that form separated or grouped chains in mucilage masses (Round et al., 1990; Guiry and Guiry, 2021). These structural characteristics suggest that they can be easily ingested by oysters, as reported by other authors in previous studies on the stomach contents of bivalves (Kasim and Mukai, 2009). Nutritionally, species of this genus are rich in lipids and carbohydrates (Mata et al., 2010), essential components for the growth and reproduction of oysters (Ren et al., 2000).

The pennate diatom Thalassionema frauenfeldii, the fourth most abundant in the composition of gut content of oysters, occurred in both seasonal periods (Supplementary material II). However, high contributions were recorded during the dry period, since it is a typical species of pelagic marine environments (Moreira Filho et al., 1990), preferring more saline waters, as observed in this seasonal period in the present study. This organism has a solitary or colonial life habit (star or fan shape), with elongated cells surrounded by tiny spines (Cupp, 1943). Like Cymtosira belgica and Thassiosira sp., Thalassionema frauenfeldii does not have ornamentations considered harmful to oysters, which favors their ingestion, as recorded for representatives of this genus in previous studies developed in other estuarine and marine ecosystems (Christo et al., 2015).

The tychoplankton and marine species Tryblioptychus cocconeiformis (Moreira Filho et al., 1990) was present in the stomach contents analyzed during all months of the study (Supplementary material II). Water turbidity in the rainy season and high salinity values in the dry season may have favored the occurrence of this species in both seasonal periods. The morphological characteristics of this organism, such as: tangentially wavy circular and elliptical valves and absence of setae and thorns (Garibotti et al., 2011), can be considered attributes that contribute to their ingestion by oysters. The study by Estrada-Gutiérrez et al. (2017), corroborates not only the occurrence of this species in the food composition of oysters of the genus Crassostrea, but also its greater contribution in the months of the dry period, which, according to the author, is directly related to the highest salinity values recorded in their study.

The cluster analysis corroborated the accentuated seasonality recorded by other authors throughout the Amazon estuaries (see references above). The group represented by samples from the estuarine environment was clearly divided into two different subgroups, which included separately the months of the dry period (2a) and the rainy period (2b). The formation of these groups was governed by the contribution of different species, which are adapted to different environmental conditions resulting from local seasonality. The group 1, in turn, showed a different pattern with samples of the dry period joining together wits samples from June (rainy period), thus suggesting that gut content of C. gasar is not necessarily affected by seasonality of diatom composition in the environment. This result supports the suggestion that C. gasar selectively feeds on the diatoms present in the estuary.

5. Conclusions

Our results indicate that cultivated oysters feed on diatoms identified in the estuary with selectivity in the ingestion process, as the main species recorded in the gut contents were not similar to the most abundant and frequent species found in the estuary during the same months of the present study.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Barbara Silva, Luci Pereira and Rauquírio Costa; Data curation, Barbara Silva; Formal analysis, Barbara Silva, Antonio de Oliveira, João Pinheiro and Brenda Silva; Funding acquisition, Rauquírio Costa; Investigation, Barbara Silva, Antonio de Oliveira, João Pinheiro, Brenda Silva, Luci Pereira and Rauquírio Costa; Methodology, Barbara Silva, Antonio de Oliveira, João Pinheiro, Brenda Silva, Remo Costa and Luci Pereira; Project administration, Rauquírio Costa; Software, Remo Costa; Supervision, Rauquírio Costa; Validation, Barbara Silva; Writing – original draft, Barbara Silva, Antonio de Oliveira, João Pinheiro, Brenda Silva, Remo Costa, Luci Pereira and Rauquírio Costa. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed by the National Council of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq, Brazil; #425872/2016-5) and in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brazil (CAPES). The first author is grateful to CAPES for the concession of a scholarship - Finance Code 001. Pereira LCC (#309491/2018-5 and #314037/2021-7), and Costa RM (#311782/2017-5 and # 314040/2021-8) would also like to thank CNPq, and CAPES (#88881.736742/2022-01) for their research grants.

References

- Abreu CHMD, Cunha AC (2016) Qualidade da água e índice trófico em rio de ecossistema tropical sob impacto ambiental. Eng Sanit e Ambient 22: 45-56.

- Adite A, Sonon1 SP, Gbedjissi GL (2013) Feeding ecology of the mangrove oyster, Crassostrea gasar (Dautzenberg, 1891) in traditional farming at the coastal zone of Benin, West Africa. Nat Sci 5: 1238-1248.

- Affe HMJ, Santana RMC (2016) Fitoplâncton em áreas de cultivo de ostras na Baía de Camamu, Brasil: Investigação da ocorrência de microalgas potencialmente nocivas. Novas Edições Acadêmicas.

- Andrade GJPO (2016) Maricultura em Santa Catarina: a cadeia produtiva gerada pelo esforço coordenado de pesquisa, extensão e desenvolvimento tecnológico. Rev Eletr de Exten 13: 204-217.

- Andrade MP, Magalhães A, Pereira LCC, Flores-Montes MJ, Pardal EC, Andrade TP, Costa RM (2016) Effects of a La Niña event on hydrological patterns and copepod community structure in a shallow tropical estuary (Taperaçu, Northern Brazil). J Mar Syst 164: 128-143.

- Antelo FS, Anschau A, Costa JA, Kalil SJ (2010) Extraction and purification of C-phycocyanin from Spirulina platensis in conventional and integrated aqueous two-phase systems. J Braz Chem Soc 21: 921-926.

- Barbosa ICC, Müller RCS, Alves CN, Berrêdo JF, Souza Filho PW (2015) Composição Química de Sedimento de Manguezal do Estuário Bragantino (PA)-Brasil. Rev Virtual Quim 7: 1087-1101.

- Barros FAL, Andrade MP, Silva TRC, Pereira LCC, Costa RM (2019) Composição e mudanças espaciais e temporais da diversidade e densidade do mesozooplâncton em um estuário amazônico (Emboraí Velho, Pará, Brasil). Bol Mus Para Emílio Goeldi Sér Ciênc Nat 14: 307-330.

- Bastos P, Vieira GC, dos Reis IMM, Costa RL, Lopes GR (2018) Comportamento alimentar de paralarvas do polvo Octopus vulgaris Tipo II (Cuvier, 1797) alimentadas com artêmia enriquecida com microalgas e suplementada com DHA. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec 70: 628-632.

- Batista AP, Gouveia L, Bandarra NM, Franco JM, Raymundo A (2013) Comparação de perfis de biomassa microalgal como novo ingrediente funcional para produtos alimentícios. Algal Res 2: 164-173.

- Belcher JH, Swale EMF (1979) English freshwater records of Actinocyclus normanii (Greg.) Hustedt (Bacillariophyceae). Br Phycol J 14:225–229.

- Bennamoun L, Afzal MT, Léonard A (2015) Drying of alga as a source of bioenergy feedstock and food supplement–A review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 50: 1203-1212.

- Bere T (2014) Ecological preferences of benthic diatoms in a tropical river system in São Carlos-SP, Brazil. Tropical Ecol 55: 47-61.

- Cardoso C, Gomes R, Rato A, Joaquim S, Machado J, Gonçalves JF, Afonso C (2019) Elemental composition and bioaccessibility of farmed oysters (Crassostrea gigas) fed different ratios of dietary seaweed and microalgae during broodstock conditioning. Food Sci Nutr 7: 2495-2504.

- Castro P, Huber ME (2012) Biologia marinha. AMGH Editora, Porto Alegre.

- Cavalcanti LF, Azevedo-Cutrim ACG, Oliveira ALL, Furtado JA, Araújo BDO, Sá AKDDS, Cutrim MVJ (2018) Structure of microphytoplankton community and environmental variables in a macrotidal estuarine complex, São Marcos Bay, Maranhão-Brazil. Braz J Oceanogr 66: 283-300.

- Cavan EL, Hill SL (2021) Commercial fishery disturbance of the global ocean biological carbo. Glob Chang Biol 28: 1212-1221.

- Cheng P, Zhou C, Chu R, Chang T, Xu J, Ruan R, Yan X (2020) Effect of microalgae diet and culture system on the rearing of bivalve mollusks: Nutritional properties and potential cost improvements. Algal Res 51: 102076.

- Christensen T (1988) Alger i naturen og i laboratoriet. Københavns Universitets, Institut for sporeplanter, 137 pp.

- Christo SW, Ivachuk CS, Veroneze F, Ferreira-Jr AL, Absher TM (2015) Descrição alimentar e estágio de maturação de Crassostrea brasiliana comercializadas no mercado municipal de Paranaguá, Paraná, Brasil. Braz J Aquat Sci Tech 19: 1-9.

- Cognie B, Barillé L, Rincé Y (2001) Selective feeding of the oyster Crassostrea gigas fed on a natural microphytobenthos assemblage. Estuaries 24: 126–134.

- Conover WJ (1998) Estatística não paramétrica prática. John Wiley & Sons.

- Costa KG, Azevedo SS, Pereira LCC, Costa RM (2018) Variabilidade temporal do zooplâncton no sistema estuarino do Rio Paracauari (Ilha do Marajó, Pará). Trop Oceanogr 46: 53-69.

- Costa LCO, Silva PLH da, Abreu PC (2021) Biofloc removal by the oyster Crassostrea gasar as a candidate species to an Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) system with the marine shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture 540: 736731.

- Cupp EE (1943) Marine plankton diatoms of the west coast of North America. Bulletin of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

- Dué A, Costa SMM, Silva Filho EA, Guedes ÉAC (2012) Itens alimentares de Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828) (Bivalvia: Ostreidae) cultivadas em um estuário tropical, no Nordeste do Brasil. Bioikos – Título não-Corrente 24: 83-93.

- Dupuy C, Vaquer A, Lam-Höai T, Rougier C, Mazouni N, Lautier J, Collos Y, Le Gall S (2000). Feeding rate of the oyster Crassostrea gigas in a natural planktonic community of the Mediterranean Thau Lagoon. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 205: 171–184.

- Espinosa EP, Barillé L, Allam B, (2007) Use of encapsulated live microalgae to investigate pre-ingestive selection in the oyster Crassostrea gigas. Journal of Exp Mar Biol Ecol 343: 118-126.

- Estrada-Gutiérrez KM, Siqueiros-Beltrones DA, Hernández-Almeida OU (2017) New records of benthic diatoms (Bacillariophyceae) for Mexico in the Nayarit littoral found in gut contents of Crassostrea corteziensis (Mollusca: Bivalvia). Rev Mex Biodiver 88: 985-987.

- FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (2020) Sustainability in action. Available at: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca9229en/ (accessed on 1 mar 2021).

- Fiddy SP, Priscilla D, Laurent B, Gastineau R, Jacquette B, Figiel A, Morançais M, Tremblay R, Mouget J-L, Cognie B (2017) Cell size-based, passive selection of the blue diatom Haslea ostrearia by the oyster Crassostrea gigas. J Molluscan Stud 83: 145–152.

- Fritz LW, Lutz RA, Foote MA, van Dover CL, Ewart JW (1984) Selective feeding and grazing rates of oyster (Crassostrea virginica) larvae on natural phytoplankton assemblages. Estuaries 7: 513–518.

- Galvão MN, Pereira OM, Machado IC, Henriques MB (2000) Estuário de Cananéia, SP (25 S; 48 W). Bol Inst Pesc 26: 147-162.

- Garcia M (2016) Taxonomia, morfologia e distribuição de Cymatosiraceae (Bacillariophyceae) nos litorais de Santa Catarina e Rio Grande do Sul. Biot Neotrop 16.

- Garibotti IA, Ferrario ME, Almandoz GO, Castaños C (2011) Ciclo sazonal de diatomáceas na Baía de Anegada, sistema estuarino de El Rincón, Argentina. Diatom Res 26: 227-241.

- Grasshoff K, Ehrhardt M, Kremling K (1983) Methods of Seawater Analysis. Second, Revised and Extended Edition. Verlag Chemie.

- Guiry MD, Guiry, GM (2021) AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication. National University of Ireland, Galway. Available at: http://www.algaebase.org. (accessed on: 3 April 2021).

- Han DY, Chen Y, Zhang CL, Ren Y, Xue Y, Wan R (2017) Evaluating impacts of intensive shellfish aquaculture on a semi-closed marine ecosystem. Ecol Model 359: 193–200.

- Harris R, Wiebe P, Lenz J, Skjoldal HR, Huntley M (2000) ICES Zooplankton Methodology Manual. Academic Press.

- Hasle GR, Syvertsen EE, Steidinger K, Tangen K, Tomas C, (1996) Identificação de Diatomáceas e Dinoflagelados Marinhos. Elsevier.

- Hasle R, Fryxell GA (1970) Diatoms: cleaning and mounting for light and electron microscopy. Trans Am Micros Soc 89: 469-474.

- Herrera JS, Fernández DR (2017) Uso potencial de microalgas para mitigar los efectos de las emisiones de dióxido de carbono. Rev Invest 10: 153-164.

- Huang H, Chen S, Xu Z, Wu Y, Mei L, Pan Y, Yan X, Zhou C (2023) Comparative metabarcoding analysis of phytoplankton community composition and diversity in aquaculture water and the stomach contents of Tegillarca granosa during months of growth. Mar Pollut Bull 187: 114556.

- IBGE, Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2020) Available at: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/pa/pesquisa/18/16458 (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Idei M, Osada, K, Sato S, Toyoda K, Nagumo T, Mann DG (2012) Gametogenesis and auxospore development in Actinocyclus (Bacillariophyta). PLoS ONE 7: e41890.

- INMET, Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia. Normas climatológicas (2020) Available at: https://portal.inmet.gov.br/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Jones AB, Perston NP, Dennison WC (2002) The efficiency and condition of oysters and macroalgae used as biological filters of shrimp pond effluent. Aquac Res 33: 1-19.

- Kasim M, Mukai H (2009) Food sources of the oyster (Crassostrea gigas) and the clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) in the Akkeshi-ko estuary. Plankton Benthos Res 4: 104-114.

- Kumar K, Dasgupta CN, Das D (2014) Cell growth kinetics of Chlorella sorokiniana and nutritional values of its biomass. Bioresour Technol 167: 358-36.

- Li Y, Meseck SL, Dixon MS, Rivara K, Wikfors GH (2012) Temporal Variability in Phytoplankton Removal by a Commercial, Suspended Eastern Oyster Nursery and Effects on Local Plankton Dynamics. J Shellfish Res 31: 1077-1089.

- Macedo ARG, Silva ADS, Sousa NDC, Silva FD, Barros FAL, Suhnel S, Silva OLL, Nunes ESCL, Cordeiro CAM, Fujimoto RY (2020) Crescimento e viabilidade econômica da ostra nativa Crassostrea gasar (Adanson, 1757) cultivadas em dois sistemas. Custos e Agrone On Line 16: 282-312.

- Koening ML, Lira CGD (2005) O gênero Ceratium Schrank (Dinophyta) na plataforma continental e águas oceânicas do Estado de Pernambuco, Brasil. Acta Bot Bras 19: 391-397.

- Luo X, Pan K, Wang L, Li M, Li T, Pang B, Kang J, Fu J, Lan W (2022) Anthropogenic Inputs Affect Phytoplankton Communities in a Subtropical Estuary. Water 14: 636.

- Magalhães A, Nobre DSB, Bessa RSC, Pereira LCC, Costa, RM (2013) Diel variation in the productivity of Acartia lilljeborgii and Acartia tonsa (Copepoda: Calanoida) in a tropical estuary (Taperaçu, Northern Brazil). Jour Coast Res 65: 1164-1169.

- Mata TM, Martins AA, Caetano NS (2010) Microalgae for biodiesel production and other applications: a review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 14: 217-232.

- Mattei F, Buonocore E, Franzese PP, Scardi M (2021) Global assessment of marine phytoplankton primary production: Integrating machine learning and environmental accounting models. Ecol Model 45: 109578.

- Matos AP (2017) The impact of microalgae in food science and technology. J Am Oil Chem Soc 94: 1333-1350.

- Matos JB, Oliveira SMD, Pereira LCC, Costa RM (2016) Structure and temporal variation of the phytoplankton of a macrotidal beach from the Amazon coastal zone. An Acad Bras Cienc 88: 1325-1339.

- Matos JB, Silva NISD, Pereira LCC, Costa RMD (2012) Caracterização quali-quantitativa do fitoplâncton da zona de arrebentação de uma praia amazônica. Acta Bot Bras 26: 979-990.

- Matos JB, Sodré DKL, Costa KG, Pereira LCC, Costa RM (2011) Spatial and temporal variation in the composition and biomass of phytoplankton in an Amazonian estuary. J Coast Res SI64: 1525-1529.

- Matteucci SD, Colma A (1982) Metodología para el estudio de la vegetación. Secretaria General de la Organización de los Estados Americanos. Washington, EUA.

- Melo AGC de, Varela ES, Beasley CR, Schneider H, Sampaio I, Gaffney PM, Tagliaro CH (2010) Molecular identification, phylogeny and geographic distribution of Brazilian mangrove oysters (Crassostrea). Genet Mol Biol 33: 564-572.

- MMA, Ministério do Meio Ambiente (2019) Available at: https://www.mma.gov.br/ (Aacessed on 5 July 2019).

- Montagna P, Palmer TA, Pollack JB (2012). Hydrological changes and estuarine dynamics. Springer, New York.

- Moreira Filho H, Valente-Moreira IM, Souza-Mosimann RMD, Cunha JA (1990) Avaliação florística e ecológica das diatomáceas (Chrysophyta, Bacillariophyceae) marinhas e estuarinas nos Estados do Paraná, Santa Catarina e Rio Grande do Sul. Estu de Biol 25: 5-48.

- Muñetón-Gómez MDS, Villalejo-Fuerte M, Gárate-Lizarraga I (2010) Gut content analysis of Anadara tuberculosa (Sowerby, 1833) through histological sections. CICIMAR Oceánides 25: 143-148.

- Müller-Melchers FC, Ferrando HJ (1956) Técnica para el estudio de las diatomeas. Boletim do Instituto Oceanográfico 7: 151-160.

- Oliveira ARG, Odebrecht C, Pereira LCCP, Costa RM (2022) Phytoplankton variation in an Amazon estuary with emphasis on the diatoms of the Order Eupodiscales. Ecohydrol Hydrobi 22: 55–74.

- Oliveira ARG, Queiroz JBM, Pardal EE, Pereira LCCP, Costa RM (2023) How does the phytoplankton community respond to the effects of La Niña and post-drought events in a tide-dominated Amazon estuary? Aquat Sci 85.

- Pan K, Lan W, Li T, Hong M, Peng X, Xu Z, Lio W, Jiang H (2021). Control of phytoplankton by oysters and the consequent impact on nitrogen cycling in a subtropical bay. Sci Total Environ 796: 149007.

- Parsons TR, Strickland JDH (1963) Discussion of spectrophotometric determination of marine-plant pigments, with revised equations for ascertaining chlorophylls and carotenoids. J Mar Res 21: 155-163.

- Pomeroy LR, D’elia CF, Schaffner, LC (2006) Limits to top-down control of phytoplankton by oysters in Chesapeake Bay. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 325: 301-309.

- Porter ET, Franz H, Lacouture R (2018) Impact of Eastern oyster Crassostrea virginica biodeposit resuspension on the seston, nutrient, phytoplankton, and zooplankton dynamics: A mesocosm experiment. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 586: 21–40.

- Reis RDSC, Brabo MF, Rodrigues RP, Campelo DAV, Veras GC, Santos MAS, Bezerra AS (2020a) Aspectos socioeconômicos e produtivos de um empreendimento comunitário de ostreicultura em uma reserva extrativista marinha no litoral amazônico, Pará, Brasil. Int J Dev Res 10: 35072-35077.

- Reis RDSC, Silva Costa AT, Rodrigues RP, Campelo DAV, Veras GC, Brabo MF (2020b) Aspectos tecnológicos de um empreendimento de ostreicultura em uma reserva extrativista marinha na Amazônia. Rev em Agro e Meio Amb 13: 1263-1279.

- Ren JS, Ross AH, Schiel DR (2000) Functional descriptions of feeding and energetics of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas in New Zealand. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 208: 119-130.

- Richard SF, Denise LB, Roger IEN, Kemp WM, Luckenbach M (2007) Effects of oyster population restoration strategies on phytoplankton biomass in Chesapeake Bay: A flexible modeling approach. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 336: 43–67.

- Round FE, Crawford RM, Mann DG (1990) The Diatoms: Biology and Morphology of the Genera. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Sampaio DS, Tagliaro CH, Schneider H, Beasley CR (2019) Oyster culture on the Amazon mangrove coast: asymmetries and advances in an emerging sector. Rev Aquac 11: 88-104.

- Santos ASD, Sousa PHC, Melo NFACD, Mesquita KFC, Pereira JAR, Santos MDLS (2020) Distribuição espaçotemporal dos parâmetros abióticos e bióticos em um Estuário Amazônico (Brasil). Arqu de Ciênc do Mar 53: 82-97.

- Sharoni S, Halevy I (2021) Geologic controls on phytoplankton elemental composition. Proc of the Nat Aca of Scie 119: e2113263118.

- Silva OLL, Macedo ARG, Nunes ESCL, Campos KD, Araújo LCC, Tiburço X, Pinto ASO, Joele MRSP, Ferreira MS, Silva ACR, Raices RCL, Cruz AG, Juen L, Rocha R.M (2020b) Effect of environmental factors on the fatty acid profiles and physicochemical composition of oysters (Crassostrea gasar) in Amazon estuarine farming. Aquac Res 51: 2336-2348.

- Silva OLL, Veríssimo SMM, Rosa AMBP, Iguchi YB, Nunes ESCL, Moraes CM, Cordeiro CAM, Xavier DA, Pinto ASO, Joele MRSP, Brito JS, Juen L, Rocha RM (2020a) Effect of environmental factors on microbiological quality of oyster farming in Amazon estuaries. Aquac Rep 18: 100437.

- Silva-Cunha MGG, Eskinazi-Leça E (1990) Catálogo das diatomáceas (Bacillariophyceae) da plataforma continental de Pernambuco. SUDENE, Recife.

- Simonsen R (1974) The Diatom Plankton of the Indian Ocean Expedition of R/V “Meteor” 1964-1965. Meteor Forsc: Reihe D, Biologie 19: 1-107.

- Sipaúba-Tavares LH, Rocha O (2003) Production of plankton (phytoplankton and zooplankton) for feeding aquatic organisms. Rima, São Carlos, 106 pp.

- Sousa JA, Cunha KN, Nunes ZMP (2013) Influence of seasonal factors on the quality of a tidal creek on the Amazon coast of Brazil. J Coast Res 65: 129-134.

- Souza-Mosimann RM, Laudares-Silva R, Roos-Oliveira AM (2001) Diatomáceas (Bacillariophyta) da Baía Sul, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brasil, uma nova contribuição. INSULA Rev de Botân 30: 75-106.

- Souza ERO, Abrunhosa FA, Martinelli-Lemos JM (2019) Distribuição da densidade larval do caranguejo Petrolisthes armatus (Gibbes, 1850) (Decapoda: Porcellanidae) no estuário de Curuçá, Amazônia brasileira. Bio Amaz 9: 27-31.

- Strickland JDH, Parsons TR (1972) A Practical handbook of seawater analysis. Bulletin Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Canadá, pp. 1-211.

- Tomas CR (1997) Identifying Marine Phytoplankton. Elsevier. Academic Press, Cambridge.

- Underwood AJ (1997) Experiments in Ecology: Their Logical Design and Interpretation using Analysis of Variance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- UNESCO (1966) Determination of photosynthetic pigments in sea-water. Imprimerie Rolland, Paris.

- Utermöhl H (1958) Zur Vervollkommung der quantitativen phytoplankton-methodik. Schweizerbart, Stuttgart, 38 pp.

- Moreira IMV, Filho HM, Cunha JA (1994) Diatomáceas (Chrysophyta, Bacillariophyceae) em biótopo de manguezal do rio Perequê, em Pontal do Sul, Paranaguá, Estado do Paraná, Brasil. Acta Biol Paran 23: 55-72.

- Varela ES, Beasley CR, Schneider H, Sampaio I, Marques-Silva NDS, Tagliaro CH (2007) Molecular phylogeny of mangrove oysters (Crassostrea) from Brazil. J Molluscan Stud 73: 229-234.

- Weissberg E, Glibert P (2021) Diet of the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, growing in a eutrophic tributary of Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, USA. Aquac Rep 20: 100655.

- World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) (2020) An authoritative classification and catalogue of marine names. https://www.marinespecies.

- Zar JH (1999) Biostatistical Analysis. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.Supplementary material I - Permanent slide preparation protocol. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).