Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

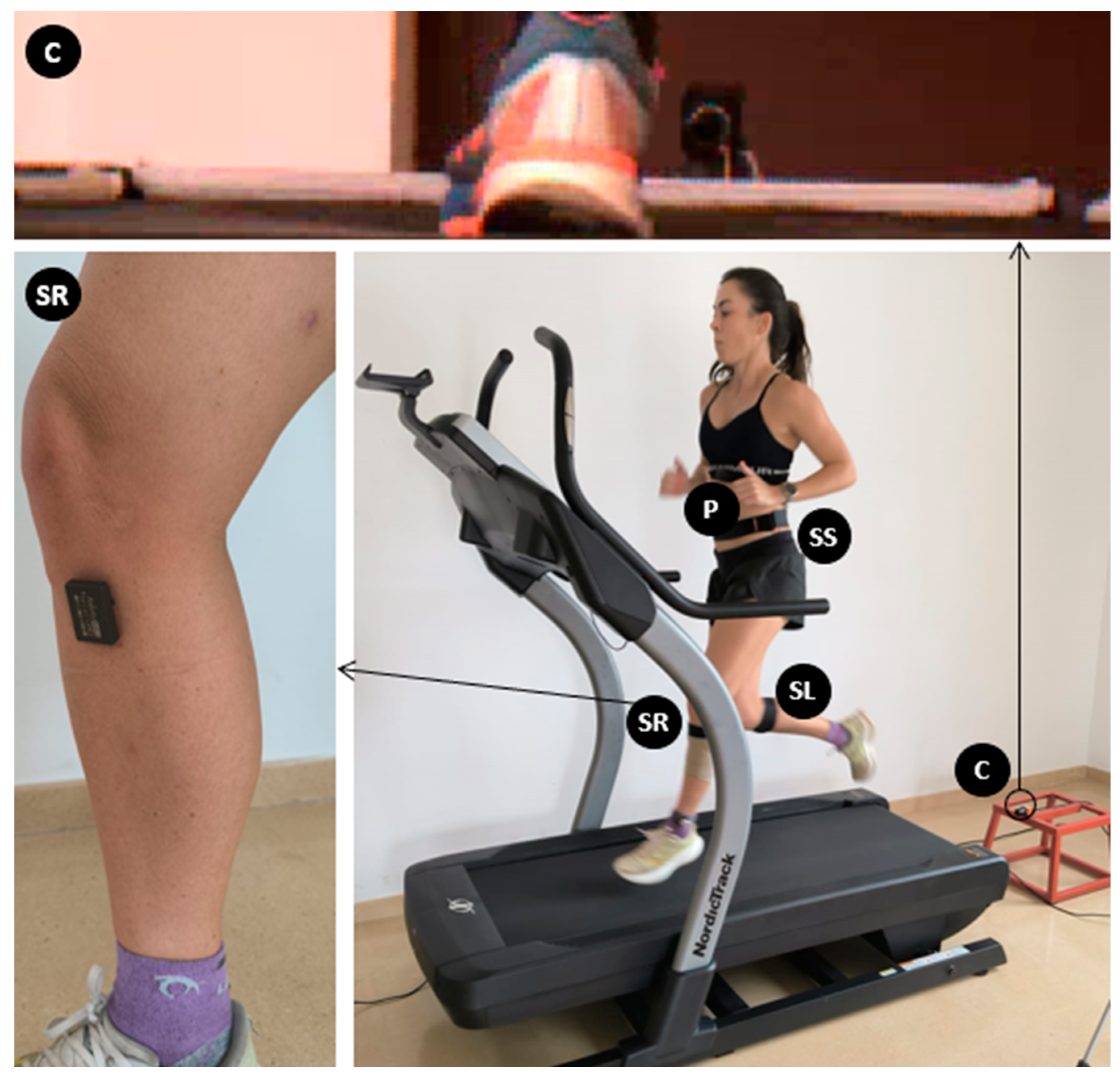

2.3. Procedures and Instruments

Acceleration Spikes Asymmetries Analysis

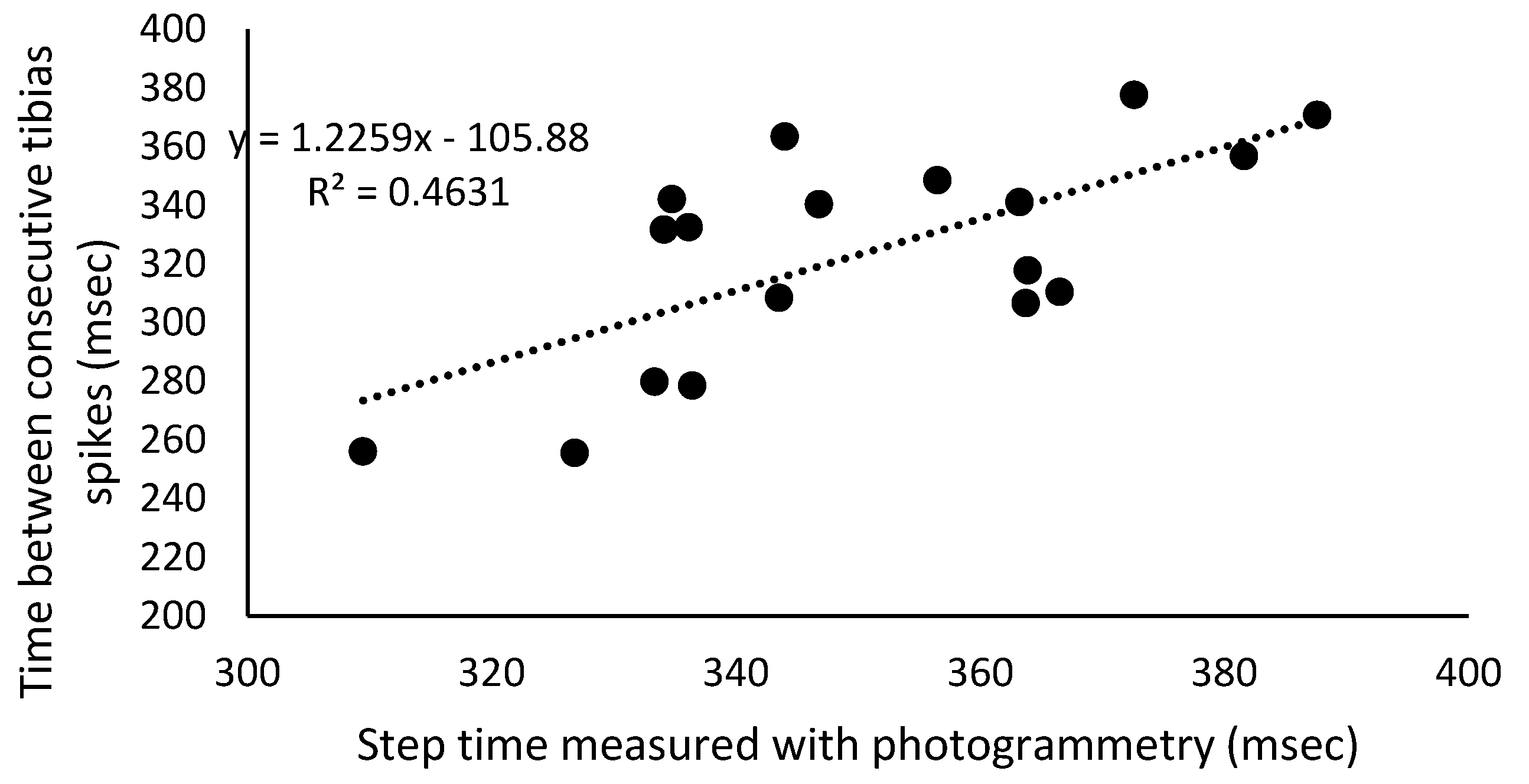

Kinematic-Temporal Analysis

2.4. Data and Statistical Analysis

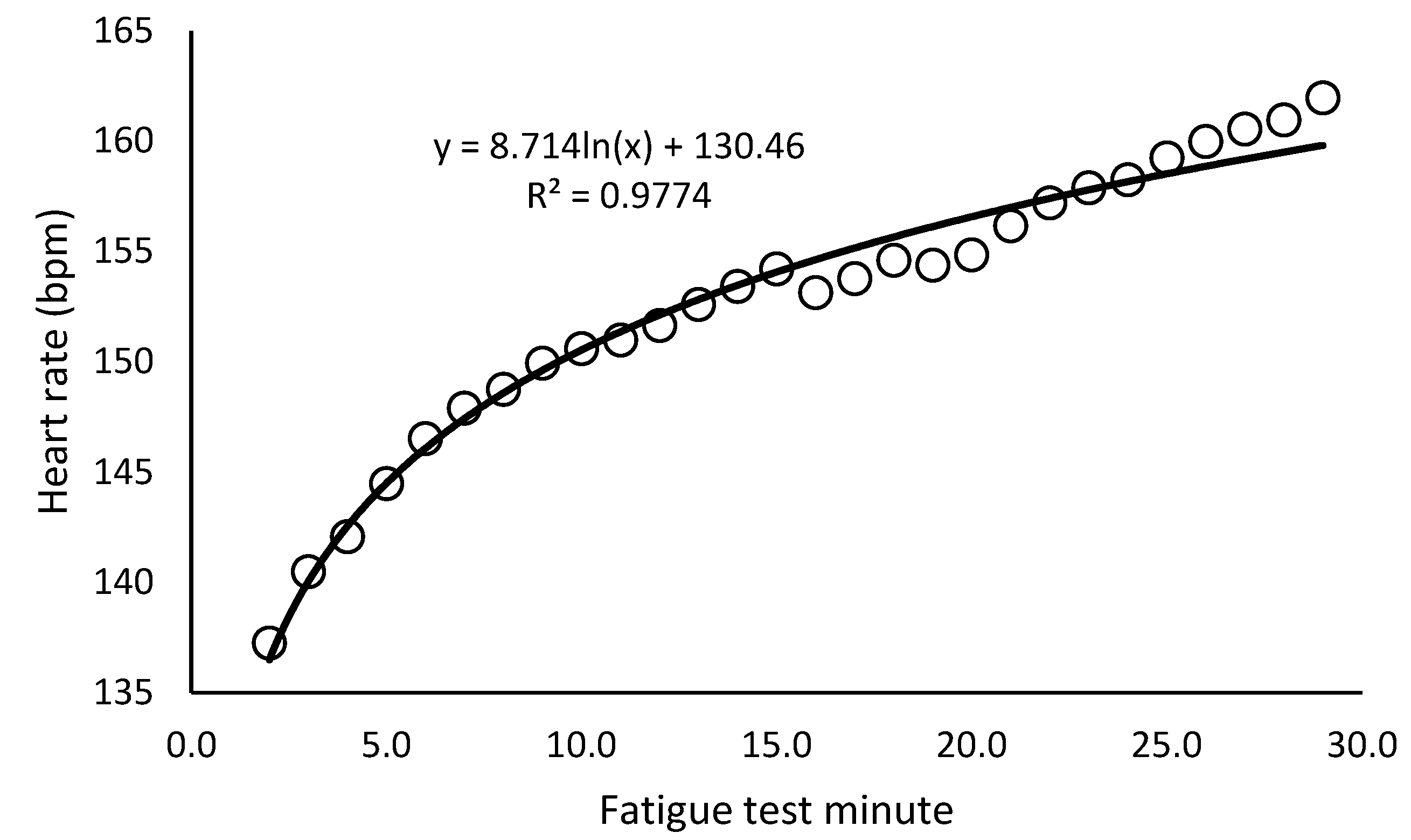

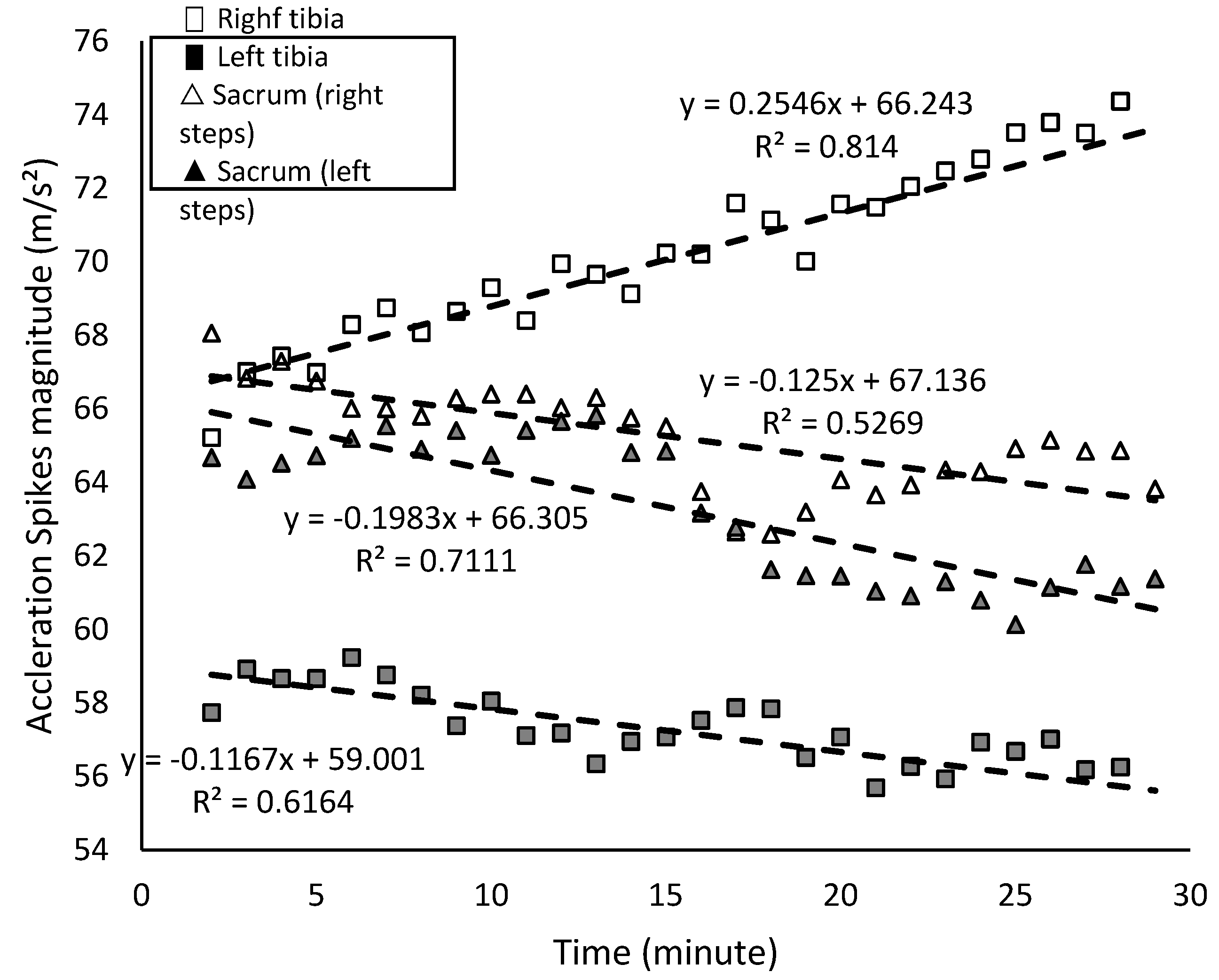

3. Results

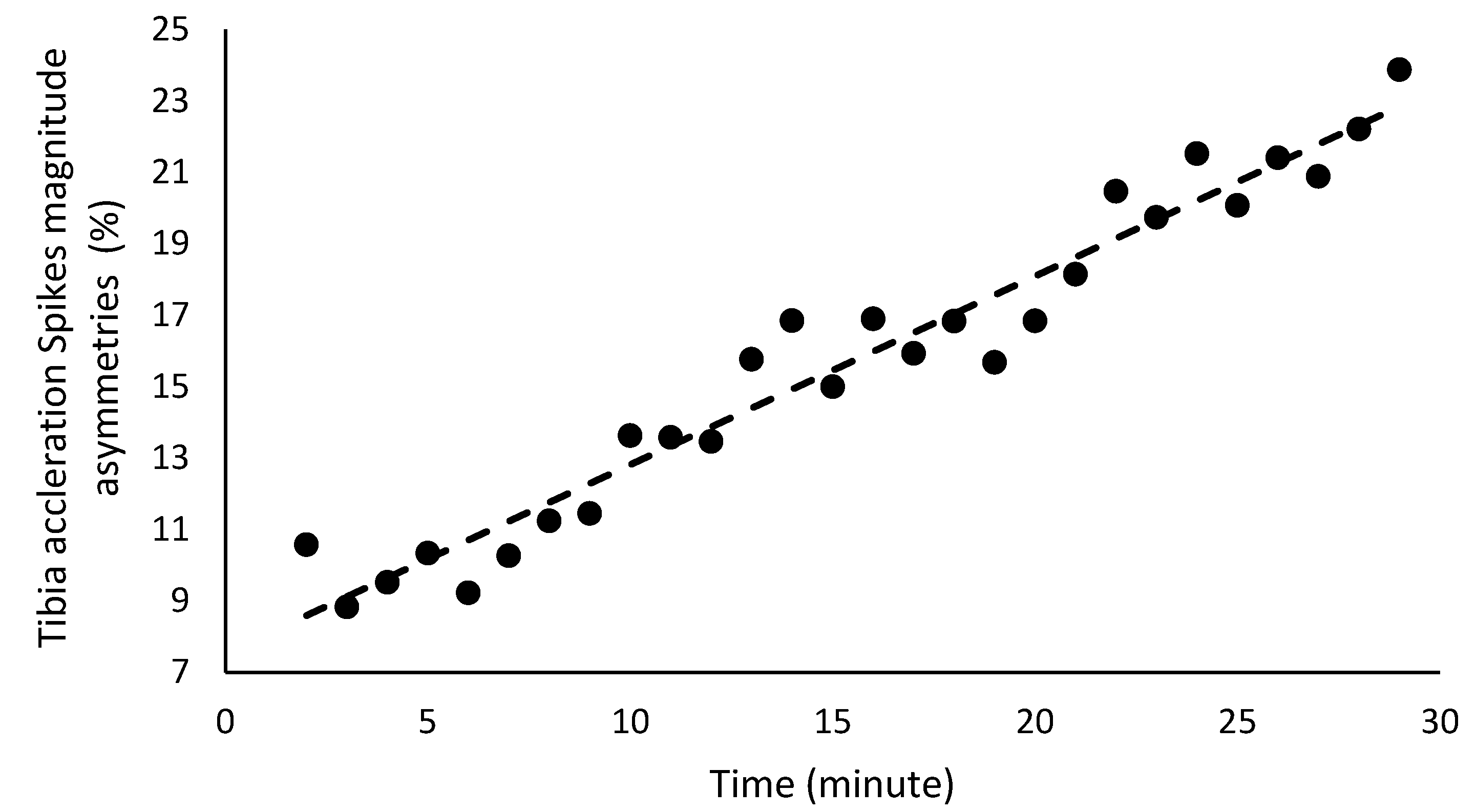

3.1. Asymmetries and Acceleration Spikes Trend in the Fatigue Test

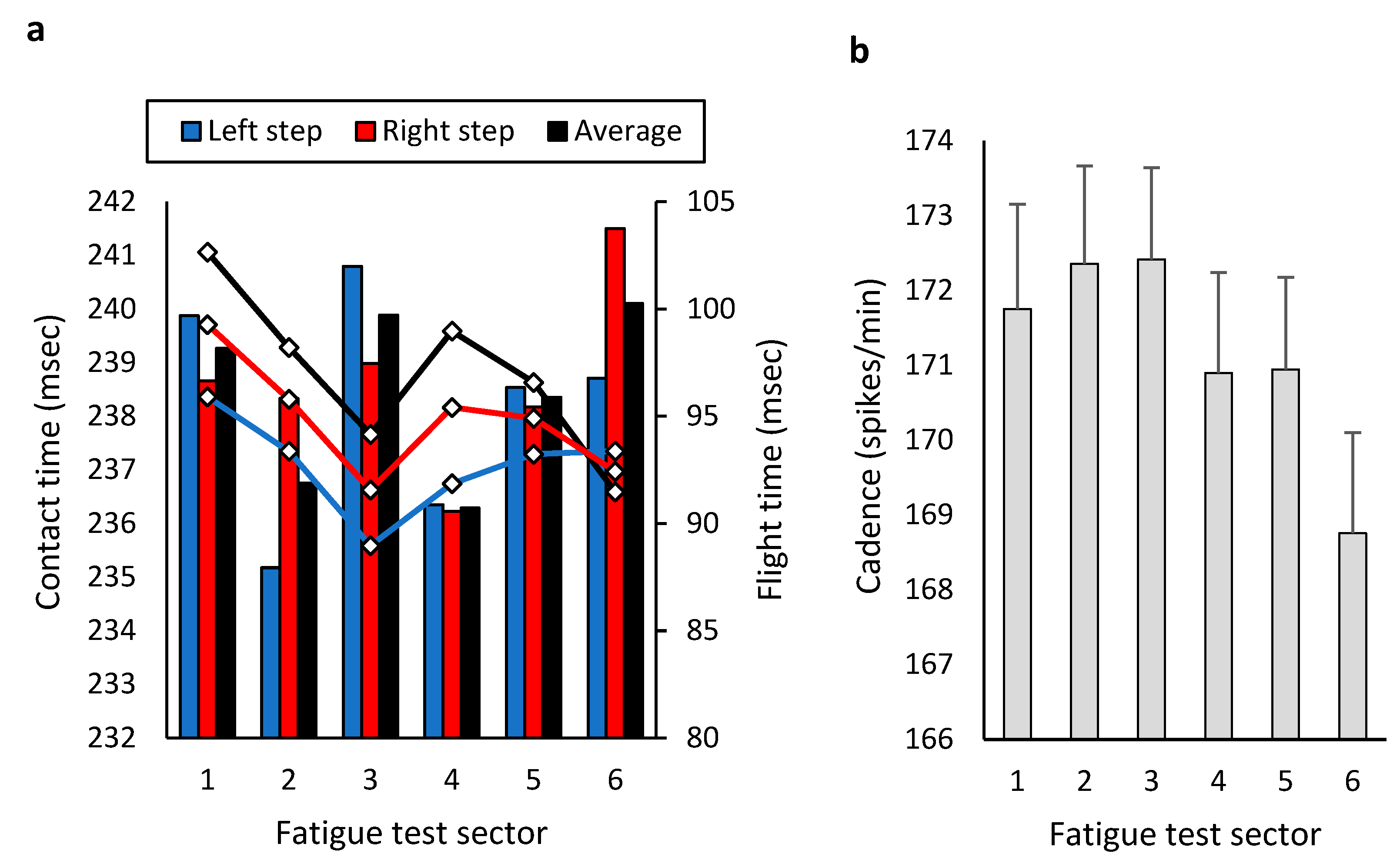

3.2. Kinematics Differences Between Sectors in the Fatigue Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krishan, K.; Kanchan, T.; DiMaggio, J.A. A Study of Limb Asymmetry and Its Effect on Estimation of Stature in Forensic Case Work. Forensic Science International 2010, 200, 181.e1–181.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, H.; Allard, P.; Prince, F.; Labelle, H. Symmetry and Limb Dominance in Able-Bodied Gait: A Review. Gait & Posture 2000, 12, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.M.; Zifchock, R.A.; Hillstrom, H.J. The Effects of Limb Dominance and Fatigue on Running Biomechanics. Gait & Posture 2014, 39, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zifchock, R.A.; Davis, I.; Higginson, J.; McCaw, S.; Royer, T. Side-to-Side Differences in Overuse Running Injury Susceptibility: A Retrospective Study. Human movement science 2008, 27, 888–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zifchock, R.A.; Davis, I.; Hamill, J. Kinetic Asymmetry in Female Runners with and without Retrospective Tibial Stress Fractures. Journal of Biomechanics 2006, 39, 2792–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, O.N.; Azua, E.N.; Grabowski, A.M. Step Time Asymmetry Increases Metabolic Energy Expenditure during Running. Eur J Appl Physiol 2018, 118, 2147–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pinillos, F.; Cartón-Llorente, A.; Jaén-Carrillo, D.; Delgado-Floody, P.; Carrasco-Alarcón, V.; Martínez, C.; Roche-Seruendo, L.E. Does Fatigue Alter Step Characteristics and Stiffness during Running? Gait & Posture 2020, 76, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhler, F.; Fadillioglu, C.; Stein, T. Fatigue-Related Changes in Spatiotemporal Parameters, Joint Kinematics and Leg Stiffness in Expert Runners During a Middle-Distance Run. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 634258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhler, F.; Stetter, B.; Müller, H.; Stein, T. Stride-to-Stride Variability of the Center of Mass in Male Trained Runners After an Exhaustive Run: A Three Dimensional Movement Variability Analysis With a Subject-Specific Anthropometric Model. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, J.; Verbitsky, O.; Isakov, E.; Daily, D. Effect of Fatigue on Leg Kinematics and Impact Acceleration in Long Distance Running. Human Movement Science 2000, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, I.; Smith, G.A. Preferred and Optimal Stride Frequency, Stiffness and Economy: Changes with Fatigue during a 1-h High-Intensity Run. Eur J Appl Physiol 2007, 100, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, D.R.; Pennuto, A.P.; Trigsted, S.M. The Effect of Exertion and Sex on Vertical Ground Reaction Force Variables and Landing Mechanics. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2016, 30, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzak, K.N.; Putnam, A.M.; Tamura, K.; Hetzler, R.K.; Stickley, C.D. Asymmetry between Lower Limbs during Rested and Fatigued State Running Gait in Healthy Individuals. Gait & Posture 2017, 51, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.-S. Vertical Ground Reaction Force Asymmetry in Prolonged Running. Korean Journal of Applied Biomechanics 2018, 28, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtibaa, K.; Zarrouk, N.; Ryu, J.H.; Racinais, S.; Girard, O. Mechanical Asymmetries Remain Low-to-Moderate during 30 Min of Self-Paced Treadmill Running. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1289172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Fekete, G.; Baker, J.S.; Liang, M.; Xuan, R.; Gu, Y. Effects of Running Fatigue on Lower Extremity Symmetry among Amateur Runners: From a Biomechanical Perspective. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 899818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, D.M.; Dowling, J.J. Mechanical Modeling of Tibial Axial Accelerations Following Impulsive Heel Impact. Journal of Applied Biomechanics 2000, 16, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-García, G.; Vanrenterghem, J.; Molina-Molina, A.; Soto-Hermoso, V.M. Acceleration Spikes and Attenuation Response in the Trunk in Amateur Tennis Players during Real Game Actions. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part P: Journal of Sports Engineering and Technology, 7543. [Google Scholar]

- García-Pérez, J.A.; Pérez-Soriano, P.; Llana Belloch, S.; Lucas-Cuevas, Á.G.; Sánchez-Zuriaga, D. Effects of Treadmill Running and Fatigue on Impact Acceleration in Distance Running. Sports Biomechanics 2014, 13, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A.; Dillon, S.; O’Connor, S.; Whyte, E.F.; Gore, S.; Moran, K.A. Relative and Absolute Reliability of Shank and Sacral Running Impact Accelerations over a Short- and Long-Term Time Frame. Sports Biomechanics 2024, 23, 3074–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J.; Bates, B.; Dufek, J.; Hreljac, A. Characteristics of Shock Attenuation during Fatigued Running. Journal of Sports Sciences 2003, 21, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbitsky, O.; Mizrahi, J.; Voloshin, A.; Treiger, J.; Isakov, E. Shock Transmission and Fatigue in Human Running. Journal of Applied Biomechanics 1998, 14, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voloshin, A.S.; Mizrahi, J.; Verbitsky, O.; Isakov, E. Dynamic Loading on the Human Musculoskeletal System —Effect of Fatigue. Clinical Biomechanics 1998, 13, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M., Jonathan H. Doust, A. A 1% Treadmill Grade Most Accurately Reflects the Energetic Cost of Outdoor Running. Journal of Sports Sciences 1996, 14, 321–327. [CrossRef]

- Karatzanos, E.; Paradisis, G.; Zacharogiannis, E.; Tziortzis, S.; Nanas, S. Assessment of Ventilatory Threshold Using Near-Infrared Spectroscopy on the Gastrocnemius Muscle during Treadmill Running. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 2010, 40, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohrmann, C.; Harms, H.; Kappeler-Setz, C.; Troster, G. Monitoring Kinematic Changes With Fatigue in Running Using Body-Worn Sensors. IEEE Trans. Inform. Technol. Biomed. 2012, 16, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzi, U.H.; Stergiou, N.; Kurz, M.J.; Hageman, P.A.; Heidel, J. Nonlinear Dynamics Indicates Aging Affects Variability during Gait. Clinical Biomechanics 2003, 18, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.R.; Snow, R.; Agruss, C. Changes in Distance Running Kinematics with Fatigue. Journal of Applied Biomechanics 1991, 7, 138–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.D. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences; Brooks/Cole Pub. Co: Pacific Grove, 1996; ISBN 978-0-534-23100-2. [Google Scholar]

- Rabita, G.; Couturier, A.; Dorel, S.; Hausswirth, C.; Le Meur, Y. Changes in Spring-Mass Behavior and Muscle Activity during an Exhaustive Run at V ̇ O2max. Journal of Biomechanics 2013, 46, 2011–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanno, M.; Willwacher, S.; Epro, G.; Brüggemann, G.-P. Positive Work Contribution Shifts from Distal to Proximal Joints during a Prolonged Run. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2018, 50, 2507–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellis, E.; Zafeiridis, A.; Amiridis, I.G. Muscle Coactivation Before and After the Impact Phase of Running Following Isokinetic Fatigue. Journal of Athletic Training 2011, 46, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrick, T.R.; Dereu, D.; Mclean, S.P. Impacts and Kinematic Adjustments during an Exhaustive Run. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2002, 34, 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalitsios, C.; Nikodelis, T.; Mavrommatis, G.; Kollias, I. Subject-Specific Sensitivity of Several Biomechanical Features to Fatigue during an Exhaustive Treadmill Run. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vial, S.; Cochrane Wilkie, J.; Anthony, M.; Turner, M.; Blazevich, J. Fatigue Does Not Increase Limb Asymmetry or Induce Proximal Joint Power Shift during Sprinting in Habitual, Multi-Speed Runners 2021.

- Hanley, B.; Tucker, C.B. Gait Variability and Symmetry Remain Consistent during High-Intensity 10,000 m Treadmill Running. Journal of Biomechanics 2018, 79, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, J.; Shields, K.J.; Nhean, H.; Ramsey, J.; Adams, C.; Richards, G.A. Fatigue Effects on Peak Plantar Pressure and Bilateral Symmetry during Gait at Various Speeds. Biomechanics 2023, 3, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, O.; Brocherie, F.; Morin, J.-B.; Millet, G.P. Lower Limb Mechanical Asymmetry during Repeated Treadmill Sprints. Human Movement Science 2017, 52, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, O.; Li, S.N.; Hobbins, L.; Ryu, J.H.; Peeling, P. Gait Asymmetries during Perceptually-Regulated Interval Running in Hypoxia and Normoxia. Sports Biomechanics 2024, 23, 918–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, O.; Millet, G.P.; Micallef, J.-P. Constant Low-to-Moderate Mechanical Asymmetries during 800-m Track Running. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1278454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, O.; Racinais, S.; Couderc, A.; Morin, J.-B.; Ryu, J.H.; Piscione, J.; Brocherie, F. Asymmetries during Repeated Treadmill Sprints in Elite Female Rugby Sevens Players. Sports Biomechanics 2023, 22, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, T.; Bini, R.; Arndt, A. Running after Cycling Induces Inter-Limb Differences in Muscle Activation but Not in Kinetics or Kinematics. Journal of Sports Sciences 2021, 39, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Mei, Q.; Fekete, G.; Baker, J.S.; Gu, Y. The Effect of Prolonged Running on the Symmetry of Biomechanical Variables of the Lower Limb Joints. Symmetry 2020, 12, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanshammar, K.; Ribom, E.L. Differences in Muscle Strength in Dominant and Non-Dominant Leg in Females Aged 20–39 Years – A Population-Based Study. Physical Therapy in Sport 2011, 12, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height [cm] | 153 | 190 | 172.8 | 9.0 |

| Weight [kg] | 47.3 | 88.6 | 68.9 | 11.2 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 20.2 | 27.6 | 22.9 | 2.1 |

| FM [%] | 8.3 | 22.8 | 14.7 | 4.1 |

| FFM [kg] | 36.6 | 72.8 | 55.9 | 9.5 |

| Body water [%] | 55.6 | 67.2 | 62.0 | 3.4 |

| Resting heart rate [lpm] | 53 | 84 | 63.2 | 8.5 |

| Systolic blood pressure [mmHg] | 91 | 170 | 119.9 | 16.4 |

| Diastolic blood pressure [mmHg] | 61 | 92 | 71.7 | 8.8 |

| BMI: Body mass index; FM: Fat mass; FFM: Free Fat Mass | ||||

| Asymmetries (%) | Mean ± SD | Pearson r | Slope | Intercept | t | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tibia acceleration spikes (%) | 16 ± 5 | 0.98 | 0.55 | 7.7 | 25.59 | <0.001 |

| Sacrum acceleration spikes (%) | 4 ± 2 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 2.9 | 1.88 | 0.0714 |

| Attenuation (%) | -15 ± 281 | -0.02 | -0.81 | -2.1 | -0.1 | 0.7291 |

| SD: Standard Deviation | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).