Introduction

Movement is a physical activity. This is the basis of life, this is the expression of living. To the human being, human movement has been the focus of attention for study and analysis down through the ages. With this purpose, experts of different fields have classified human movements into different categories in order to understand their nature and scope, and to explain their utility and purpose in a better way. Physical educators are very much concerned with human movement because the core programme of this area is planned to utilise human movement as the educational medium. On the way to classifying human movements, . F. Williams, a lifetime proponent of physical education, has mentioned, to an important degree, the distinction to be drawn between natural motor movements that are present in racial motor activities of ‘man and the artificial creations in ‘Systems of Movements.

H. M. Barrow has classified human activities into general type and highly specialised pattern. J. P. Thomas has grouped the physical education activities under three heads : natural activities, naturalised activities and artificial activities. The general activities as classified by Thomas and the general type activities as mentioned by Barrow are the same as general motor activities mentioned by Williams. They are fundamental and universal in nature. They have been a part of behaviour of humankind and their prehuman ancestors for countless ages in their inescapable struggle for existence and survival (Barrow & Thomas, 1983).

At present, a number of individuals from the fields other than physical education are also associated with the task of unfolding the complex nature of human movement. This interdisciplinary effort has developed a number of specialised branches within the purview of physical education and sports science; to name a few of which are Sports Pedagogy, Sports Psychology, Sports Sociology, Exercise & Sports Physiology, Sports Medicine, Sports Anthropometry, Biomechanics of Sports, Sports Statistics, Sports Management etc.

Running and jumping are two natural activities which individuals learn in the process of physical growth and development in the early stages of life. They are two fundamental locomotor activities. Though as a natural process, every normal grown up person can run and jump, all are not equally efficient in performing these activities. Some can run faster, jump further or higher in comparison with others inspite of their similar body structure and shape. Individuals also differ in quality of movements in these activities. Because of these basic differences in performance ability, one feels proud and satisfied for being recognised by others when he proves himself superior to others either in his speed of running or in jumping ability. This very fact has provided these two activities the unique place in the field of competitive sports from remote past till to-day. Thus, when we look back to the history of Olympic games, the earliest form of recognised competition the human beings had, we can see that these two activities were two important events there (Williams, 1939).

Same is the case for Olympic games of modern era. Importance of supremacy in performance ability in these activities has been emphasised even in the Olympic motto where the first two words are ‘Citius’ and ‘Altius’ meaning faster and higher respectively.

In most of the games also, running and jumping are used as the basic threads. For example, running is one of the basic elements in the movement structure of football, cricket, hockey, tennis, handball etc., jumping is an essential element of volleyball and netball, and both are used as components of basketball games. So, for teaching and learning, coaching, and practicing most of the games, due emphasis is given to the performance ability in running and jumping.

Leaving the fields of physical education and competitive sports, when we consider the fundamental processes of locomotion, we see that every individual performs these activities in day-to-day living. Therefore, irrespective of age and sex, irrespective of the field of work, it is required for all to be efficient in running and jumping with varying degrees of perfection.

As the basic locomotor movement, each of these activities has get a specific purpose. Running is a process of advancement in a particular direction. The purpose here is to cover a required distance as fast as possible. To draw a distinction between this process and walking, another process of locomotion, Scott has mentioned that running is a faster process. Secondly, in each complete cycle, walking has a double contact phase when both feet touch the ground simultaneously. In running, this phase is absent. On the contrary, it has a flying phase in each cycle when both feet come off the ground.

For analysing the action of running and jumping, the general tenden:y is to focus attention on the details of leg movements ignoring what arns and other parts of the body are doing. This is perhaps due to the fact that the driving leg plays the main role in deriving the required ground reaction force in these activities. So, its movement has been considered as the prima-y movement in running and jumping. But Glenn Cunningham, the great miler once said that his arms were more tired than his legs at the end of a race. Chi Cheng, the famous athlete who had either equalled or bettered seven world records, once said, “It is a misconception that you run only with year legs. Running is done with the whole body. It is very important for a sprinter to have a strong body and arms.

Biomechanics has been defined as the study of the movement of living things using the science of mechanics. The mechanics is a branch of physics that is concerned with the description of motion and how forces create motion. Forces acting on living things can create motion, be a healthy stimulus for growth and development, or overload tissues, causing injury. Biomechanics provides conceptual and mathematical tool that are necessary for understanding how living things move and how. Kinesiology professionals might improve movement or make movement safer (Knudson, 2007).

Biomechanics is therefore not kinesiology (which is often another name for physical education). There are numerous titles of books that are confusing, especially since the title suggest more than the definition of biomechanics that was stated earlier. Examples include, but are limited to, Fundamentals of Sports Biomechanics, The Mechanics of Athletics, Scientific Principles of Coaching, Biomechanical Analysis of Sport, Biomechanics of Sports Techniques, Biomechanics of Human Motion, and Mechanical Kinesiology. Athletes use biomechanics as a way to improve their form. By improving their form, they will better optimize their performance levels that could be the difference between winning the gold and not even making the final. Today video analyses are necessary for elite athletes. It is this way that they can watch themselves and point out even the smallest mistake and can then work hard to rectify them. A sprint race can be over in as little as 10 seconds. The athletes’ biomechanical form must be near perfect to perform at the elite level where 1/100 of second makes a huge difference. The process of getting out the blocks as quickly as possible and into a desirable position to promote absolute speed and power has turned into an art form for some sports biomechanics specialists (Coh, M. and Tomazin, K. 2006).

The History of sports biomechanics is partly the history of kinesiology. The word kinesiology was first used in the late 19th century and become popular during the 20th century, where the word biomechanics did not become popular until the 1960s. The roots of the word kinesiology give it definition as the study of movement, but in its present day usages, kinesiology is defined as the study of human movement. For many years, the term kinesiology was used to describe that body of knowledge concerned with the structure and function of muscular-skeletal system of the human body. Later the study of the mechanical principal applicable to human movement because widely accepted as an integral part of kinesiology. Later still the term was used quite literally to encompass aspects of all the sciences that impinge in any way on human movement. (McGinnis, Peter M., 2005).

At this point it because clear that kinesiology had quite lost its usefulness to describe specifically that part of the science of movement concerned with either the muscularskeletal system of the mechanical principal applicable to human movement. Several new term were suggested as substitutes and anthropomechanics, anthro kinetics, biodynamic, biokinetics, homokinetics, and kinathropology all had their proponents. Ultimately, there emerged one trem that gained much wider acceptance than other. That term was biomechanics. (Uppal, A.K., 2009).

Biomechanics is the study of forces and their effects on living systems, whereas exercise and sports biomechanics is the study of forces and their effects on humans in exercise and sports. Biomechanics may be a useful tool for physical educators, coaches, exercise scientists, athletic trainers, physical therapists, and others involved in human movement. Application of Biomechanics may lead to performance improvement of the reduction and rehabilitation of injury through improved technics, equipment, or training. (McGinnis, Peter M., 2005).

The laws governing motion indicate that motion is modified by a number of external environmental forces. Whether these forces are of help or these are hindrances, depends upon the prevailing conditions and the nature of motion. The problem in sports is to learn how to take maximum advantage of these external environmental forces under prevailing condition.

Biomechanics may be defined as the science, which deals with the application of mechanical laws to living being especially to the locomotor system. The sports biomechanics may also be defined as the science, which examine the internal and external forces acting on the athlete and the athletic implements in use and the effects produced by these forces.‖ A good knowledge of biomechanics will enable you to evaluate techniques used in unfamiliar sports skills as well as to better evaluate new techniques in sports that you are familiar with.

This biomechanical analysis may be qualitative or quantitative. A Qualitative Biomechanical Analysis relies on subjective observation of the performance, whereas a Quantitative Biomechanical Analysis uses actual measurements to quantify certain mechanical parameters of the performance. Practitioners (coaches, teachers, and clinicians) use this or some similar procedure to evaluate the movement or performance of their students, athlete, or clients. (McGinnis, Peter M., 2005).

Performance in the 100 m sprint is influenced by a multitude of factors including starting strategy, stride length, stride frequency, physiological demands, biomechanics, neural influences, muscle composition, anthropometrics, and track and environmental conditions. The sprint start, the accelerative phase of the race, depends greatly on muscular power. Three considerations of the sprint start are reaction time (time to initiate response to the sound of the starting gun), movement time (onset of response until end of movement) and response time.

Running is a result of stride length and stride frequency. While stride length can be greatly limited by an individual‘s size and joint flexibility, stride frequency can be affected by muscle composition, neuromuscular development, and training. Although 100 m sprint world record times have progressed drastically, there is limited evidence for how technology has contributed to such improvement. As such, human physiology and physique combine to be the most influential determinants of improved sprint performance. (Mendoza, L. and Schöllhorn, W. (1993)

Unlike other track-and-field sprints, such as the 200 m or 400 m event, the 100 m sprint does not involve a curve of the track. Thus, running technique involves purely linear movement, and no centrifugal or centripetal (outward and inward radial) forces. Given recent world record accomplishments in the male 100 m sprint event, we thought that a review of this event, and the multiple determinants to 100 m sprint performance would be a timely addition to the scientific and coaching literature within athletics. Consequently, the purpose of this review is to identify the features of the 100 m sprint that make it such an iconic event, and summarize the multi-faceted determinants to sprint running performance so that understanding and commentary on performance can be based on science rather than speculation or personal bias.( Lee Brown Schot, P. K. and Knutzen, K. M. (1992).

The sport of Athletics is an exclusive collection of sporting events that involve competitive running, jumping, throwing, and walking. The most common types of athletics competitions are track and field, road running, cross country running, and race walking. History of Athletics: The history of athletics its roots in human prehistory. The first recorded organized athletics events at a sports festival are the Ancient Olympic Games. At the first Games in 776 BC in Olympia, Greece, only one event was contested: the stadion footrace and the first Olympic winner was Koroibos. In later years further running competitions have been added. Also in the Ancient Olympic pentathlon, four of the events are part of the track and field we have even today.

Athletics events were also present at the Pan-Hellenic Games in Greece around this period, and they become known to Rome in 200 BC. In the middle Ages new track and field events began developing in parts of Northern Europe. The stone put and weight throw competitions popular among Celtic societies were precursors to the modern shot put and hammer throw events. Also the pole vault was popular in the Northern European Lowlands in the 18th century. Organized athletics are traced back to the Ancient Olympic Games from 776 BC. The rules and format of the modern events in athletics were defined in Western Europe and North America in the 19th and early 20th century, and were then spread to other parts of the world. Most modern top level meetings are conducted by the International Association of Athletics Federations and its member federations. The athletics meeting forms the backbone of the Summer Olympics. The foremost international athletics meeting is the IAAF World Championships in Athletics, which incorporates track and field, marathon running and race walking. Other top level competitions in athletics include the IAAF World Cross Country Championships and the IAAF World Half Marathon Championships. Athletes with a physical disability compete at the Summer Paralympics and the IPC Athletics World Championships. It is frequently said that sprinters are born and not made, and although research indicates that this is true, ―an average sprinter can become top class with the right training and competition.

The shortest existing competition in outdoor track and field running events is the 100 m sprint. As in any sprint race, the primary objective of the 100 m sprint is to cover the designated distance in the shortest time possible. Historically, the race has been recognized as a focal component of track and field, as the man and woman who owns the gender-specific world record in the 100 m sprint also traditionally carries the prominent title of ―world‘s fastest athlete‖. As compared to other sprinting events, the relative simplicity of the 100 m sprint makes it ideal for studying the elements of sprint running.

Many factors led to the improvement of various factors of performance as well as the total performance of the athlete. Performance recorded before 1948 were run without block, on rather poor (by today‘s standard), in resilient tracks. Cleary starting blocks, light weight shoes, composition track surfaces, new starting techniques and modern training programs have resulted in improved times from early track and field history Modern competitions in athletics, took place for the first time in the 19th century. Usually they were organized by educational institutions, military organizations and sports clubs as competitions between rival establishments. In these competitions the hurdling were introduced for the first time. Also, in the 19th century the first national associations have been established and organized the first national competitions. In 1880 the Amateur Athletic Association of England start organizing the annual AAA Championships while in United States in 1876 took place for the first time the USA Outdoor Track and Field Championships first by the New York Athletic Club. In 1912 the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) was established, becoming the international governing body for athletics, having the amateurism as one of its founding principles for the sport. The first continental track and field competition was the 1919 South American Championships followed by the European Athletics Championships in 1934.

Running is a cyclic movement in which two consecutive strides make up a complete cycle of movement. It is an athletic event in itself and at the same time important in numerous other sports. Scientific investigations have been playing an increasingly important role in the training of athletics to attain excellence in performance in different spheres of sports. Athletics concentrates on the development of speed, flexibility, strength, ability, endurance etc. as a part of preparation of their respective sport game. (Henry, F. M. (1952).

Whether one is a sprinter or a distance runner, you need speed and the stamina both, which is the ability to endure, to hang in there. Obviously a sprinter needs more speed than stamina and vice-versa. Speed depends not only on a considerable amount of anaerobic activity but also on the resiliency and responsiveness of the circulatory system, reaction time, flexibility and strength.

Sprinting is the fullest form of running performed over short distance in which maximum or near maximum effort can be sustained. Sprinting figures in the program of all major athletic championships including the Olympic game, in which the standard sprint event for men and women are the 100m, 200m, 400m, hurdle, as well as 4×100m and well as 4×400m relay. Sprinting is the act of running over a short distance at (or near) top speed. It is used in many sports that incorporate running, typically as a way of quickly reaching a target or goal, or avoiding or catching an opponent. Human physiology dictates that a runner’s near-top speed cannot be maintained for more than 30–35 seconds due to the depletion of Phosphocreatine stores in muscles, and perhaps secondarily to excessive Metabolic glycolysis as a result of Anaerobic glycolysis.

In athletics and track and field, sprints (or dashes) are races over short distances. They are among the oldest running competitions. The first 13 editions of the Ancient Olympic Games featured only one event—the stadion race, which was a race from one end of the stadium to the other. There are three sprinting events which are currently held at the Summer Olympics and outdoor World Championships: the 100 meters, 200 meters, and 400 meters. These events have their roots in races of imperial measurements which were later altered to metric: the 100 m evolved from the 100 yard dash, the 200 m distances came from the furlong (or 1/8 of a mile), and the 400 m was the successor to the 440 yard dash or quarter-mile race. At the professional level, sprinters begin the race by assuming a crouching position in the starting blocks before leaning forward and gradually moving into an upright position as the race progresses and momentum is gained. The set position differs depending on the start. Body alignment is of key importance in producing the optimal amount of force. Ideally the athlete should begin in a 4-point stance and push off using both legs for maximum force production. Athletes remain in the same lane on the running track throughout all sprinting events, with the sole exception of the 400 m indoors. Races up to 100 m are largely focused upon acceleration to an athlete’s maximum speed. All sprints beyond this distance increasingly incorporate an element of endurance. (Steven Cousins and Rosemary Dyson (2004).

In the last four years Usain Bolt improved the world record in the 100 m sprint three times, from 9.74 s to 9.58 s. Over the last 40 years this record has been revised up to thirteen times from 9.95 s to 9.58 s. The improvement equals 0.37 s (from 1968 to 2009) which is an increase in performance of 3.72%. By comparison, during the same time period, the 200 m world record was revised six times from 19.83 s to 19.19 s what amounts to 3.33 %. The acceleration phase is the most important phase in a race. During this phase, after the sprinter has left the blocks, the athlete increases the length of their stride and decreases the amount of strides taken per second. Men usually have a rate of 4.6 strides per second and women a little more with 4.8 strides per second. Professional sprinters reach their highest speed at about the 60-70 meter mark, in a 100 meter race, for men. Professional women sprinters reach their top speeds at 50-60 meters. The acceleration phase differs at different levels of competition .Top runners usually cover 20-30 meters at top speed. Acceleration performance is important for field sport athletes that require a high level of repeat sprint ability. Although acceleration is widely trained for, there is little evidence outlining which kinematic factors delineate between good and poor acceleration. Sprinting is the act of running over a short distance at (or near) top speed. It is used in many sports that incorporate running, typically as a way of quickly reaching a target or goal, or avoiding or catching an opponent. Human physiology dictates that a runner’s near-top speed cannot be maintained for more than 30–35 seconds due to the depletion of Phosphocreatine stores in muscles, and perhaps secondarily to excessive Metabolic acidosis as a result of Anaerobic glycolysis.

The internal and external forces acting on a human body determine how the parts of that body move during the performance of a motor skill. They determine, in short, what is commonly referred to as the performer‘s technique. (Uppal, A.K., 2009).

Sports biomechanics can help an athlete’s workout the technical kink in their armor so that they can take the next development step forward. Biomechanics not only help athletes to perform at maximum performance but can also help athletes avoid injuries and help in the rehabilitation. Technology today has improved in such a way as athletes can see where their deficiencies are, and help build that area to stop from being injured. Doctors can see where an athlete is compensating certain muscles in order to protect others. From that, they can seek out the problem a lot of the time before the athlete realizes there is a problem (McGinnis Peter Merton, 2005).

In general, there are two approaches used to study mechanical aspects of human movement. The quantitative approach involves the use of numbers. This approach helps to eliminate subjective description and relies on data from the use of different instruments. It is a more scientific, publishable, and predictable analysis than the qualitative approach that implies that the movement is described without the use of numbers. This approach is used in coaching and during the teaching of sports skills. Both quantitative and qualitative descriptions play important roles in the biomechanical analysis of human movement. To identify a movement as an economic (Winter David, 2005).

It is very essential to analyze the movement first sometimes it is very difficult for a human to analyze all the movement of various body segments and joint at the same time so, various instrument like still camera, video camera etc are used to analyze various body movements. The best method to analyze or evaluate is called cinematography. This is a quantitative method which is very accurate at the same time costly and time consuming. The role of cinematography in biomechanical research involve from a simple form of recording motor movement to a sophisticated mean of complex analysis of motor efficiency. Over the years, new technique in filming, timing having been perfected to aid the research in achieving accurate time measurement of both simple and complex locomotion patterns (Hall Susan J. 1995).

Human movement performance can be enhanced in many ways. Effective movement involves anatomical factors, neuromuscular skills, physiological capacities, and psychological/cognitive abilities. Most Kinesiology professionals prescribe technique changes and give instructions that allow a person to improve perfonnance. Biomechanics is most useful in improving perfonnance in sports or activities where technique is the dominant factor rather than physical structure or physiological capacity. Since biomechanics is essentially the science of movement technique, biomechanics is the main contributor to one of the most important skills of kinesiology professional (Knudson Duan, 2007).

Movements of the human body are produced by the contraction of muscles. However, these movements are also influenced by external forces such as gravity, friction, fluid resistance and reaction forces that are evoked through ground contact or upon impact with other bodies. The study of these physical quantities lies within a branch of physics known as mechanics. Specifically in sports biomechanics, one applies the principles of mechanics in the analysis of human movement. Such an approach will benefit professionals in the health, fitness, sports and coaching industries as they will be better able to answer fundamental questions such as: • Which technique is best? • Is a technique appropriate to the participant or is it specific to the elite athlete? • What is wrong with a performance? • How should one correct a technique?8 In most cases, a brief consideration of the anatomical and mechanical factors that contribute to the movement are sufficient to enable the practitioner to perfonn a valid qualitative analysis to resolve these problems and not resort to guesswork. If pursued further, there are more powerful tools of quantitative analysis that can be used to resolve problems of greater complexity or even general problems that are recurrently faced by the practitioner (Michael K, & T. John, 2005).

A common goal in many sports is to throw, kick, or hit a ball as far as possible. To reach this goal is simple: you apply all the force you have to the ball. But that’s not all. You also have to choose the best launch angle. The angle plays an important role in determining the distance that flying objects travel.

The term ‘gait analysis’ is a generic one referring to the study of the intricate motions and patterns associated with the limbs and the body (as a whole) involved during various acts of locomotion. While the work documented in this dissertation discusses the gait of human locomotion, it should be noted that gait studies are frequently carried out by researchers for various other purposes as well, some of which are the study of locomotion of the equine family and the gait of humanoid robots. The human body is a complex system, and the mechanics associated with the bones, muscles and joints that allow bipedal motion are a remarkable topic for study. In order to record, study, analyze, replicate and rectify the motion of the human body, the biomechanical analyses of the contributions of individual segments of the body towards the locomotion are performed, encompassed by the term ‘gait analysis.’ The practical applications of gait analysis of human locomotion are immense.

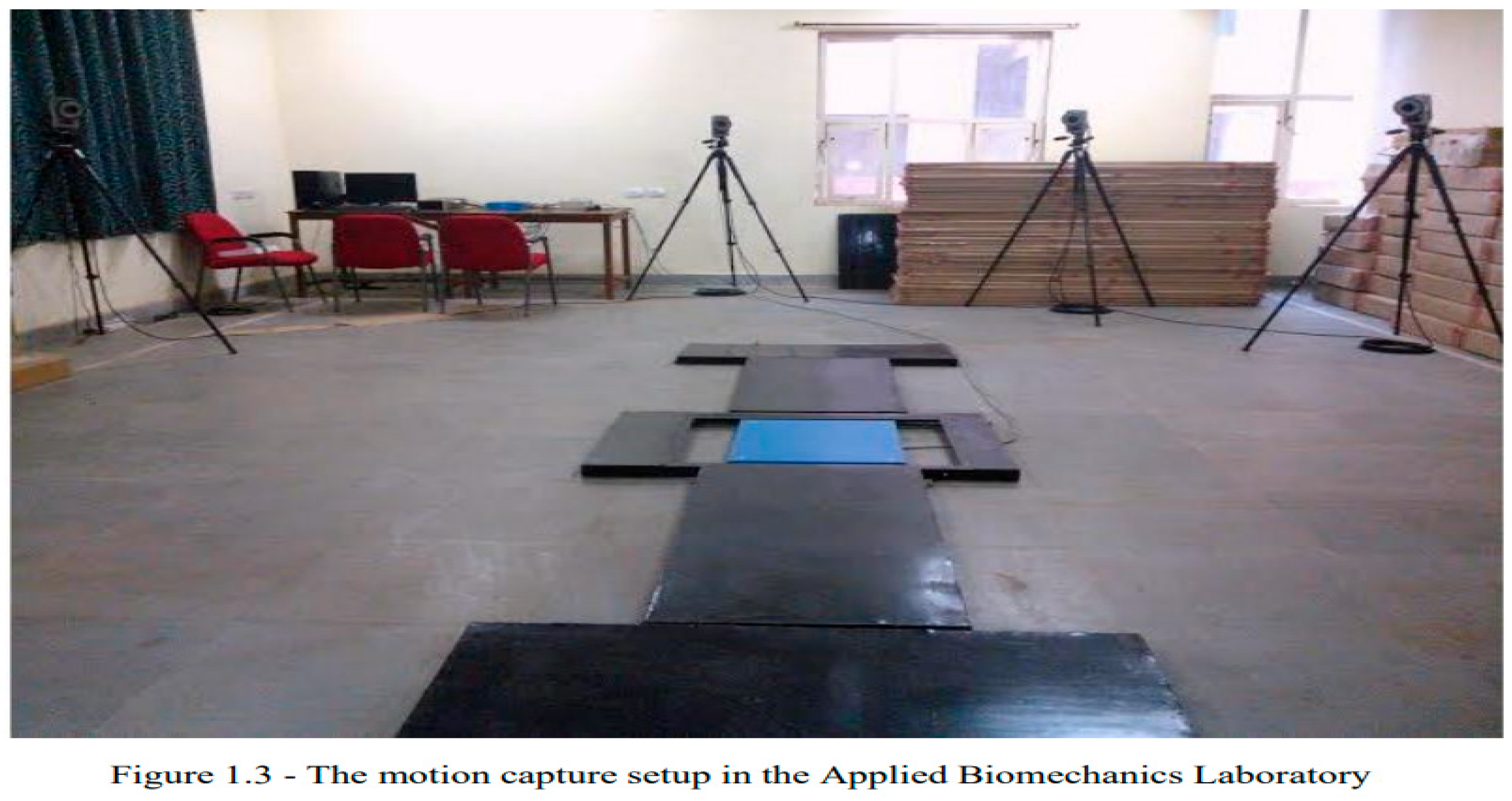

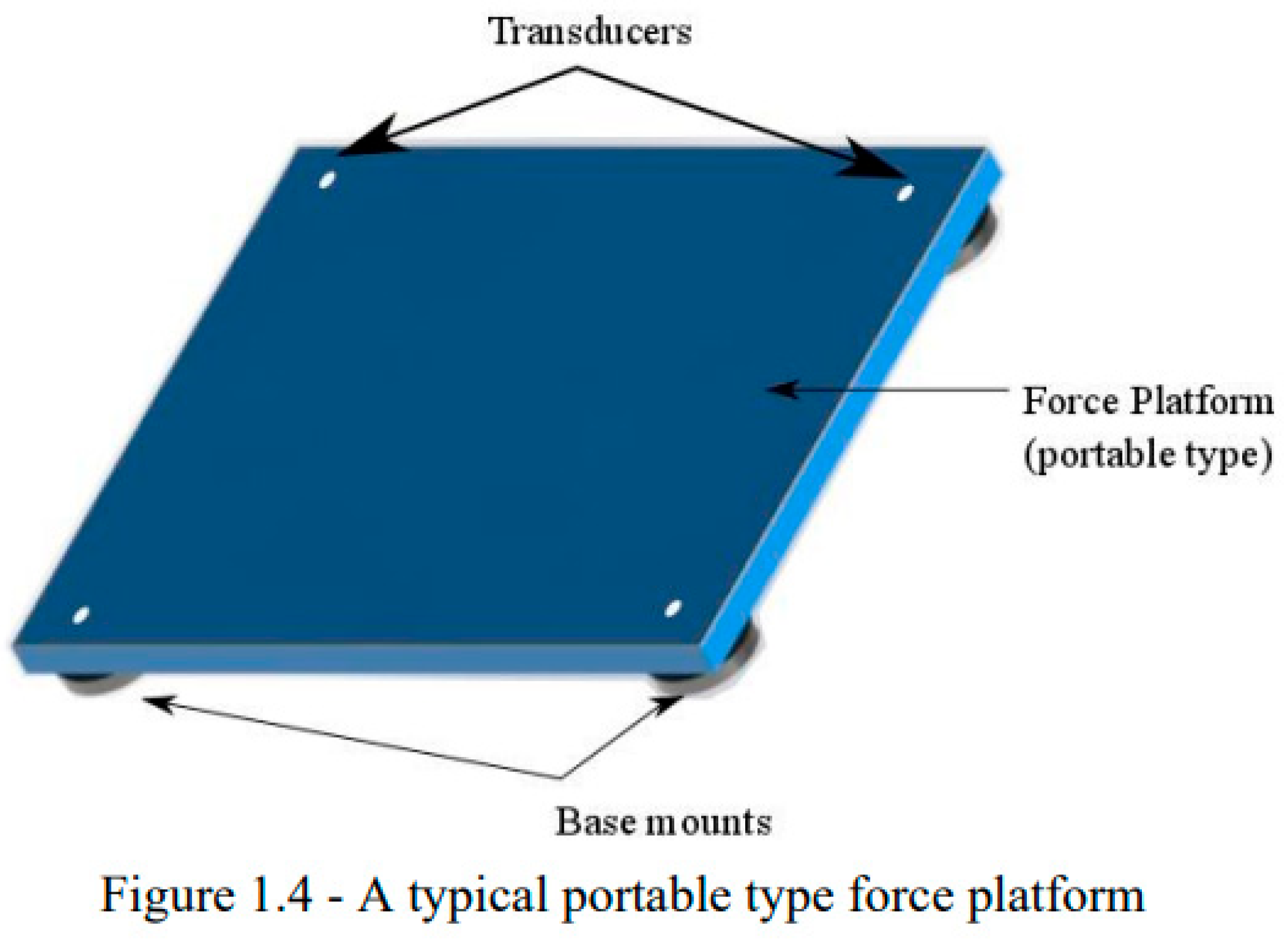

Although gait analysis is now considered as a piece of standard clinical equipment in major hospitals and research institutions, the study of human locomotion originated as early as the nineteenth century Several early publications by the German researchers Christian Wilhelm Braune and Otto Fischer elucidate the biomechanics pertaining to the human locomotion under loaded and unloaded conditions, As the technology for photography and cinematography developed, researchers began using it for understanding the human (and animal) gait, in the early 1900s. The development and commercialization of videography led to increased use of this equipment to study the kinematics of the human locomotion. The use of other electronic instruments in conjunction with the camera system led to the current state of gait analysis technology as seen today. The motion analysis systems of the present day comprise high-speed cameras specialised to record 3- dimensional (3-D) locations of the passive retro-reflective markers (RRMs) placed on the external anatomical locations corresponding to respective joints and other positions of a participant’s body. Besides these, force platforms designed to record the components of ground reaction forces are also used. Further, electromyography (EMG) setups may also be connected to synchronously acquire muscle signals. Thus, the present technology allows the user to acquire kinematic, kinetic as well as EMG signals from the intended segments of the participants’ body with ease. (Harland, M.J. and Steele, J.R, 2007)

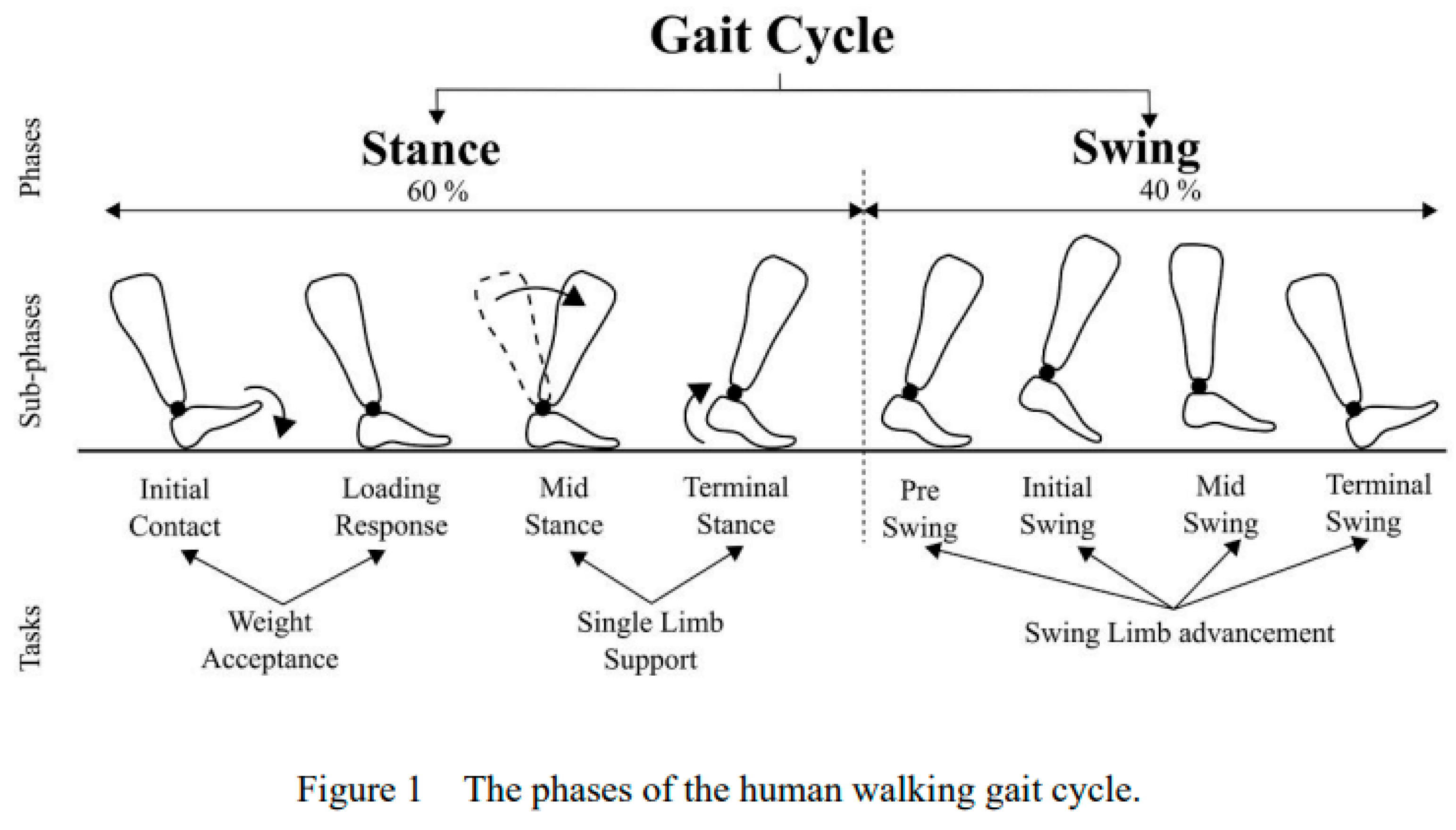

Phases of the human gait The human walking gait cycle is generally demarcated as beginning with the heel strike of a foot and ending with the subsequent heel strike of the same foot. The gait cycle is further divided into the stance phase and the swing phase constituting 60% and 40% of the gait cycle, respectively (

Figure 1) The stance phase is the part of the gait cycle where the foot (in consideration) is in contact with the ground, while during the swing phase, the foot is off the ground.

The stance phase of the gait cycle consists of the following sub-phases

- (a)

Heel contact – This sub-phase defines the beginning of the gait cycle and is the phase where the heel of the foot makes initial contact with the ground surface. The heelcontact (or heel strike) phase, as seen in the vertical ground reaction force (GRF) curve, usually includes a notch mark on the ascent of the slope.

- (b)

(b) Loading response – The loading response phase follows the heel contact phase and continues to approximately 12 % of the gait cycle. In this sub-phase, the entire weight of the body gradually shifts upon the foot in consideration. Graphically, this phase includes the first peak of the vertical GRF pattern

- (c)

Mid-stance – This sub-phase is indicative of the beginning of the single support phase (or single limb support) and continues up to about 30% of the gait cycle. This phase corresponds to the trough or depression in the vertical GRF pattern.

- (d)

Terminal stance (Push-off) – The terminal stance, as the name suggests, establishes the end of the stance phase and is also known as the push-off phase. The foot exerts a push force on the ground towards the posterior direction and thus the body moves forward, owing to the generated GRF. The push-off phase ends with the lifting of the forefoot from the ground surface, also called as toe-off. The push-off phase corresponds to the second peak in the vertical GRF pattern of a healthy gait.

The swing phase of the gait cycle begins after terminal stance phase and consists of the following sub-phases:

- (e)

Pre-swing – The terminal stance phase initiates the pre-swing phase of the foot in which there is a weight transfer with increased ankle plantarflexion, knee flexion, and reduction of hip extension. Meanwhile, the opposite foot enters heel contact and loading response phases.

- (f)

Initial swing – The initial swing phase is characterised by increased knee flexion, and hip flexion, a combination of which lifts the foot and advances the limb. There is complete ankle dorsiflexion. Simultaneously, the opposite limb enters early mid-stance.

- (g)

Mid-swing – This phase begins as the swinging foot is opposite the stance limb and ends when the tibia is in a vertical position. The mid-swing phase occurs at approximately 75% to 87 % of the gait cycle.

- (h)

Terminal swing – This phase starts with the vertical position of the tibia and ends with the heel-strike of the foot on the ground surface.

The swing phase of the human gait is terminated with the heel contact of the same foot and the next gait cycle starts.