1. Introduction

Tennis is a sport characterized by repetitive unilateral movement patterns and high-intensity effort in which limb asymmetries play an important role

[1,2,3]. A lack of balance between limbs or muscle groups is called interlimb asymmetry [

4]. Asymmetries can be caused by repetitive asymmetrical movements [

5], injuries, or anatomical asymmetries [

6]. During a tennis match, players typically run between 8-15 meters and perform an average of 3-4 change of direction (COD) at each point, alongside other high-intensity actions, such as accelerations, decelerations, and jumps [

1].

Recent studies have suggested that interlimb asymmetries may negatively affect the performance of high-intensity tasks, particularly those involving COD [

7,

8]. In this regard, one study found that jumping asymmetries were associated with decrements in sprint and jump performance among elite youth athletes [

9]. Furthermore, this study suggested that an asymmetry of 12.5% during a single-leg countermovement jump (SLCMJ) is related to reduced acceleration in youth female soccer players [

10]. Asymmetries between 10-15% can also increase the risk of injury [

11]. The most common injuries for tennis players are the lower limbs (39-59%), followed by the upper limbs (20-40%) and trunk (11-30%) [

12,

13]. Therefore, it is important to control asymmetries in tennis players to mitigate injury risks.

On the other hand, a systematic review and meta-analysis showed that asymmetries appear to present a weak negative impact on COD and sprint performance but not on vertical jump [

14]. Raya-Gonzalez et al. also concluded that there was not significant relationship between inter-limb asymmetries and physical performance measures, at least in elite youth soccer players [

15]. Despite findings suggesting that asymmetries may have a minor negative impact on COD and sprint performance, it is necessary to consider the different contexts within various sports [

16]. The absence of significant correlation in some studies could imply that other factors, such as individual technique, muscle strength, and neuromuscular adaptation, may play a more critical role in performance than asymmetries themselves. Therefore, although some studies have indicated that asymmetries may not substantially affect all aspects of sports performance, it is essential to investigate this phenomenon across different sports, such as individual ones, to achieve a more comprehensive understanding.

Bailey et al. observed that females produced significantly greater interlimb asymmetries than males in unilateral and bilateral jump variables [

17]. In addition, the researchers concluded that weaker athletes displayed more asymmetry than stronger athletes. This suggests that addressing strength imbalances may help reduce performance asymmetries in female athletes [

2]. Neuromuscular training programs seems to be an optimal tool for reducing asymmetries, according to Madruga-Parera et al. [

7].

In male tennis players, Villanueva-Guerrero et al. found significant negative relationships between CMJ and COD asymmetry with unilateral HJ variables (r = -0.30 to -0.53). In addition, CMJ asymmetry showed a significant relationship with CMJR (r = 0.49) and COD180R (r = 0.29), and COD asymmetry showed a significant relationship with COD180L (r=0.40) [

18]. Moreover, other recent research found significant negative relationships between CODS asymmetry and SLCMJ performance in both limbs (r = -0.50; r = -0.53) and CODS performance in both limbs (r = 0.50; r = 0.63) [

7,

9,

11]. Therefore, interlimb asymmetries during CODS were associated with reduced performance in jumps and CODS tests, and CMJ and COD imbalances were associated with reduced performance in HJs.

Some authors have analyzed the association between physical performance and asymmetries in male tennis players [

7,

9,

11,

18]. However, to the best of the author’s knowledge, no such study has been conducted on female tennis players. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the correlation between inter-limb asymmetries and physical performance variables in adolescent female tennis players.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty-five adolescent female tennis players (age: 13.29 ± 0.98 years; height: 162.91 ± 6.02 cm; body mass: 52.52 ± 7.31 kg; body mass index: 19.75 ± 2.21kg/m2) agreed to participate in the study. A preliminary power analysis was performed using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.3, from Düsseldorf, Germany) to determine the required number of participants. Given the study design, which examines variations within a single group, an effect size of 0.5, significance level (alpha) of 0.05, and desired power of 80%, we determined that 23 participants were needed. The study ultimately included 25 participants, yielding a statistical power of 84%.

Tennis players from two distinct academies participated in this study, all adhering to a structured training program that was consistent in both volume and methodology. This program comprised four 90-minute sessions focused on technical and tactical skills, along with two sessions dedicated to physical training each week. During the data collection period, all players were free from injury. Before participation, written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and was approved by the University Ethics Committee (approval no. 46/2/22-23).

2.2. Procedures

All physical performance tests were conducted on the same day during the players’ usual training times (18:00) under favorable weather conditions. Because these assessments are part of the Academy’s regular program, all players were already familiar with the procedures. Testing took place on a hard tennis surface with players wearing appropriate tennis shoes.

Before beginning the tests, players performed a warm-up protocol based on the Rise, Activate, Mobilise, and Potentiate (RAMP) system [

19]. This was followed by three practice runs for each test to ensure test readiness. A 3-min rest period was provided between the final practice run and the start of the first test to optimize performance. The tests were performed in the following sequence: unilateral vertical jumps, bilateral vertical jumps, unilateral HJs, bilateral HJs, 180º change of direction, and a 20-m sprint. For unilateral tests, the right leg was tested first, followed by the left leg. Between each race, a 3-min break was given to the players to allow them time to rest and hydrate.

2.2.1. The Bilateral and Unilateral Countermovement Jump Tests

The jumping height was measured using a vertical contermovement jump (CMJ) in centimeters with a flight time calculated by OptoJump (Microgate, Bolzano, Italy) as described elsewhere [

18].Each test was executed 3 times, separated by 45 s of passive recovery in between. The best jump was recorded and used for analysis. The same criteria were used to assess CMJ right (CMJR) and CMJ left (CMJL).

2.2.2. The Bilateral and Unilateral Horizontal Jump Tests

The jumping length was measured using a HJ test. To calculate the distance, it was used a standard measuring tape (30m M13; Stanley, New Britain, EEUU) and is described elsewhere [

18]. Each HJ: HJ to the right (HJR), HJ to the left (HJL), and bilateral HJ (HJ) was performed twice with a 45-s rest in between. The best result was recorded and used for analysis.

2.2.3. The 20-m Sprint

Running top speed of the tennis players was evaluated by a 20-m sprint time. The timing was performed using double-beam photoelectric cells (Witty, Micrograte, Bolzano, Italy). The timing gates were situated 1.5 m apart and at a height of 0.75 m. Each player was behind the starting line 0.5 m before the first marker and started the sprint at their own discretion (no external sign). Measurements were performed twice with a 2-min recovery between each attempt. A faster mark was recorded and used for analysis.

2.2.4. The 180º COD Test

Players performed a 10-m sprint test with a 180º COD measured by Photoelectric cells (Witty, Micrograte, Bolzano, Italy), which is described elsewhere [

18]. The 180º COD was repeated twice with the right (180CODR) and twice with the left leg (180CODL), and 2 min of between-repetition recovery was allowed. The best mark for each variant was recorded to calculate the mean time and statistical analysis.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, SPSS software (Version 28.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used. First, the Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to assess the normality of all variables. Subsequently, a one-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed to identify systematic bias between the means of asymmetry in performance variables. Lower limb asymmetries were expressed as percentages (%) using the equation of Bishop et al. [

4]. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to determine the correlation between limb asymmetries (%) and physical performance. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Additionally, the kappa coefficient was employed to measure the consistency of the direction of asymmetry between tests, which can be interpreted as follows: poor (≤0), slight (0.01-0.20), fair (0.21-0.40), moderate (0.41-0.60), substantial (0.61-0.80), almost perfect (0.81-0.99) and perfect [

20].

3. Results

Descriptive data on the physical performance and asymmetries of female tennis players are presented in

Table 1.

Table 2 presents Pearson’s correlations between interlimb asymmetry scores and performance tests. Significant relationships were found between CMJ Asymmetry and the variables HJR (r=-0.47) and HJL (r=-0.44). In addition, significant relationships were found between HJ Asymmetry and the variables CMJR (r=-0.60) and CMJL (r=-0.54), HJR (r=-0.64), HJL (r=-0.67), CMJ (r=-0.55) and HJ (r=-0.52). On the other hand, no significant relationships were found between COD Asymmetry and the variables of jumping speed, speed, and change in direction.

Table 3 presents the levels of agreement for the asymmetry scores obtained using the kappa coefficient. The results showed fair levels of agreement between the CMJ test and the 180COD test (-0.28) and slight levels between CMJ and HJ (0.09), HJ and 180COD (-0.05).

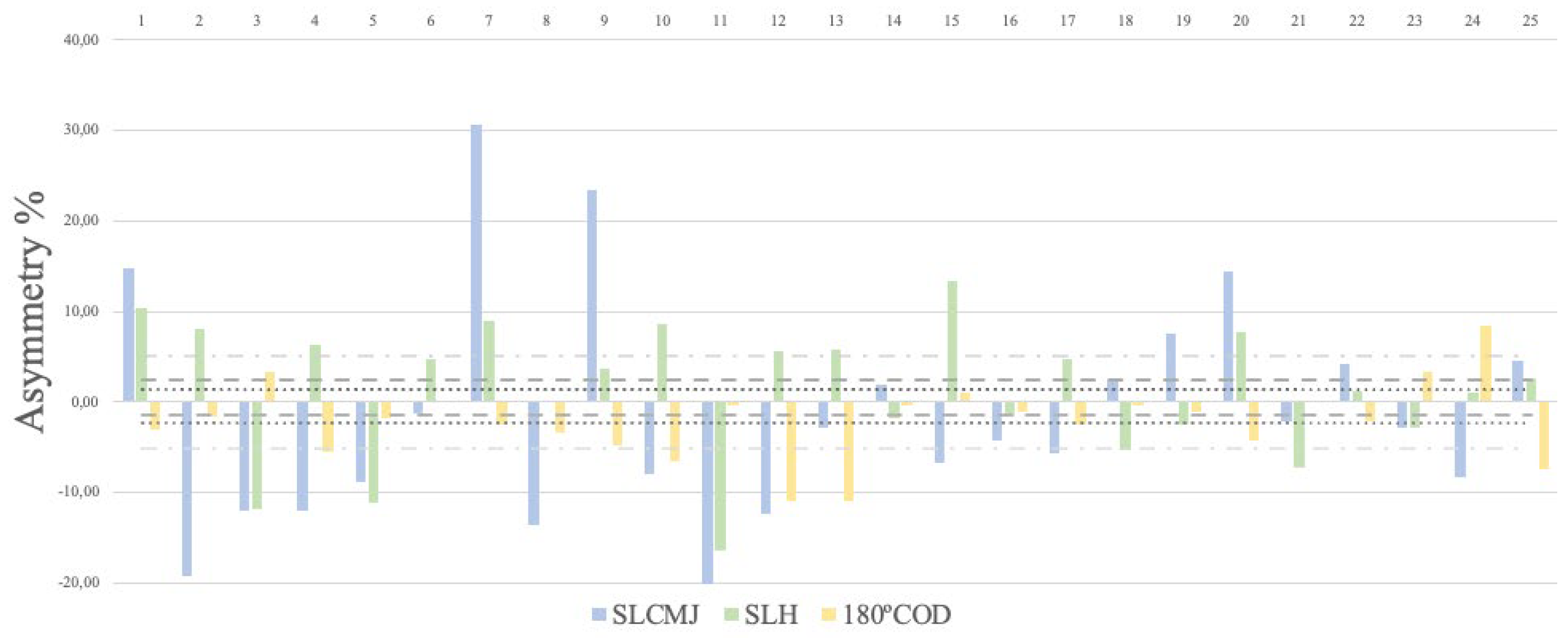

Figure 1 shows the discrepancies between the limbs for CMJ, HJ, and COD, highlighting the variability in both magnitude and direction of asymmetry in the study population.

4. Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to determine the correlation between inter-limb asymmetries and physical performance variables in adolescent female tennis players. The findings indicate significant negative correlations between HJ Asymmetry and all bilateral and unilateral jump variables (r=-0.52 to -0.64). Moreover, negative correlations were found between CMJ Asymmetry and unilateral HJs, both with the right leg (r=-0.47) and the left leg (r=-0.44). This means that as HJ asymmetry increases, performance in bilateral and unilateral jump tests (both bilateral and unilateral) decreases. Furthermore, the performance of unilateral HJs decreased with increasing CMJ asymmetry. The strong negative correlations suggest that significant imbalances between legs are associated with lower jump performance. However, no significant relationships were found between COD Asymmetry and any physical performance variables. Additionally, asymmetries between the jump and COD tests rarely favored the same side, indicating the task-specific nature of the asymmetry.

The SLCMJ showed the greatest asymmetries among the different tests (7.00 ± 10.50%), which is consistent with the findings of previous studies [

7,

9,

11,

18]. These data are fundamental, as they highlight possible imbalances in lower extremity function that could predispose tennis players to injury and reduce their performances. The CMJ showed significant negative correlations with unilateral HJs (HJR and HJL), which is interpreted as indicating that HJ performance decreases as CMJ asymmetry increases. This relationship provides information to understand how vertical power asymmetries affect lateral and forward movement skills, which are essential for tennis performance [

21]. In contrast, no correlation was found between the vertical jumps studied (CMJR, CMJL and CMJ), as observed in other studies and the 180COD [

10,

18].

Significant differences were observed in unilateral HJ asymmetries (6.03± 6.03%). This value is higher than those reported in similar studies of tennis players (4.14± 3.72%) [

7,

9,

11] and (3.97± 4.18%) [

18]. These asymmetries are particularly relevant in tennis because of the demands of rapid lateral movements, sudden directional changes, and rapid acceleration [

22]. Horizontal jump asymmetry had a significant negative correlation with vertical and HJs in both unilateral and bilateral variants (r = -0.52 to -0.67). Greater asymmetry in the HJ test results in lower performance for all types of jumps evaluated in this study, contrary to Villanueva-Guerrero et al., [

18]. Reducing asymmetries in the HJ should be a priority because doing so can improve vertical jumping performance, which is important for actions such as serves and smashes.

The 180COD test showed smaller asymmetries (1.93 ±4.39) compared to both vertical and HJs, which is consistent with recent studies on tennis players [

4,

7,

9,

11,

18,

23] and female team sports players [

24]. This lower asymmetry in COD performance is logical given the nature of tennis, which requires frequent and rapid changes of direction between both legs that should perform equally well to maintain agility and balance on the court [

25]. In addition, no differences were found between the asymmetry in COD and performance variables, which means that COD asymmetry is not directly related to jump and sprint performance. One study only observed significant associations between COD asymmetry and HJ, but not between other variables, such as CMJ sprint performance [

18]. This lack of correlation implies that COD performance is more dependent on overall coordination and the ability to decelerate and accelerate efficiently than on power and strength metrics that are more critical for jumps and sprints [

26]. Consequently, while addressing asymmetries in jumping might improve explosive power, focusing on improving COD skills might improve COD speed and thus match performance, both of which are key to success in tennis.

Regarding the results of the Kappa’s analysis, only one agreement was found between the asymmetries in the CMJ and COD180 tests. There is a negative value between them, indicating an inverse relationship, which means that if CMJ asymmetry increases, the asymmetry in COD180 tends to decrease, or vice versa. These results may help professionals understand that training programs aiming on reducing asymmetry in one variable might not necessarily benefit from reduced asymmetry in another variable.

Significant differences in asymmetry values among different physical performance tests were identified among adolescent female tennis players. Several athletes exhibited more than 10% asymmetry in SLCMJ, highlighting notable lower limb power imbalances. On the other hand, most players demonstrated asymmetries within the ±10% range in the SLH and 180COD tests, indicating better balance in these specific movements. These results are in accordance with women´ soccer [

27] and male tennis players [

18]. The asymmetries observed in the SLCMJ can be attributed to the unilateral nature of tennis, which involves frequent and intense use of one leg over the other during serves, forehands, and backhands. Furthermore, for players who use their forehand to cover most of the court, may require higher acceleration to the forehand side [

28] side . In addition, tennis involves fewer vertical movements, mainly in serves, than lateral (70%) and forward (20%) [

21], leading to more pronounced asymmetries in the SLCMJ test. In contrast, the smaller asymmetries in the SLH and 180COD tests suggest that athletes have developed a relatively balanced ability to change direction and perform lateral movements, which are essential for effective court coverage in tennis. These lateral movements and CODs are more common in tennis, which could explain the more symmetry performance in these tests. It is vital to communicate these results and findings to strength and conditioning coaches so they can implement training programs aimed at reducing limb asymmetries to below 10%, which is considered a low-risk range for injuries [

11,

29,

30]. Furthermore, understanding gender differences, the impact of specific tennis skills and the use of advanced technology to assess asymmetries can provide more valuable insights for optimizing performance and preventing injuries.

Some limitations were found in this study. First, a larger sample size will provide more information and enhance the generalizability of the results. Second, since the study is cross-sectional, it only shows a specific moment in the season. It is recommended to conduct longitudinal studies to understand how asymmetries change during training and competition during a competitive season.

5. Conclusions

This study aims to analyze lower limb asymmetries in relation to performance variables in adolescent female tennis players. It was found that the asymmetries in CMJ and HJ were important indicators of performance loss in jump tests. Additionally, the lack of a significant correlation between the 180COD and the performance tests suggests that COD asymmetries do not influence jump performance or speed. These results highlight the need for continued research and evaluation of how asymmetries affect the performance of adolescent female tennis players, as well as the creation of specific training programs to improve physical performance and reduce the risk of injury.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, N.M.-A. and E.M.-P.; Data Curation, O.V.-G., S.C.-M. and E.M.-P.; Formal Analysis, V.E.V.Á. and E.M.-P.; Investigation, N.M.-A. and O.V.-G.; Methodology, N.M.-A., O.V.-G. and E.M.-P.; Supervision, S.C.-M., V.E.V.Á. and E.M.-P.; Writing—Original Draft, N.M.-A. and S.C.-M.; Writing—Review and Editing, O.V.-G., V.E.V.Á. and E.M.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and was approved by the University Ethics Committee (approval no. 46/2/22-23).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided informed consent. In addition, written permission to publish this document was acquired from both the subjects and their guardians.

Data Availability Statement

The data from this research can be made available by the corresponding author following a justified request. Due to privacy concerns, the data are not accessible to the public.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fernandez-Fernandez, J.; Sanz-Rivas, D.; Mendez-Villanueva, A. A review of the activity profile and physiological demands of tennis match play. Strength & Conditioning Journal 2009, 31, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chapelle, L.; Bishop, C.; Clarys, P.; D’Hondt, E. International vs. national female tennis players: a comparison of upper and lower extremity functional asymmetries. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2022, 62, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kekelekis, A.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Moore, I.S.; Rosemann, T.; Knechtle, B. Risk Factors for Upper Limb Injury in Tennis Players: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, C.; Read, P.; Lake, J.; Chavda, S.; Turner, A. Interlimb asymmetries: Understanding how to calculate differences from bilateral and unilateral tests. Strength & Conditioning Journal 2018, 40, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, N.H.; Nimphius, S.; Weber, J.; Spiteri, T.; Rantalainen, T.; Dobbin, M.; Newton, R. Musculoskeletal asymmetry in football athletes: a product of limb function over time. Medicine Science Sports Exercise 2016, 48, 1379–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.R.; Sanfilippo, J.L.; Binkley, N.; Heiderscheit, B.C. Lean mass asymmetry influences force and power asymmetry during jumping in collegiate athletes. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2014, 28, 884–891. [Google Scholar]

- Madruga-Parera, M.; Bishop, C.; Fort-Vanmeerhaeghe, A.; Beltran-Valls, M.R.; Skok, O.G.; Romero-Rodríguez, D. Interlimb asymmetries in youth tennis players: Relationships with performance. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2020, 34, 2815–2823. [Google Scholar]

- Ličen, U.; Kozinc, Ž. The influence of inter-limb asymmetries in muscle strength and power on athletic performance: a review. Montenegrin Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Fort-Vanmeerhaeghe, A.; Bishop, C.; Buscà, B.; Aguilera-Castells, J.; Vicens-Bordas, J.; Gonzalo-Skok, O. Inter-limb asymmetries are associated with decrements in physical performance in youth elite team sports athletes. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0229440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.; Read, P.; McCubbine, J.; Turner, A. Vertical and horizontal asymmetries are related to slower sprinting and jump performance in elite youth female soccer players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2021, 35, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.; Turner, A.; Maloney, S.; Lake, J.; Loturco, I.; Bromley, T.; Read, P. Drop jump asymmetry is associated with reduced sprint and change-of-direction speed performance in adult female soccer players. Sports 2019, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, G.D.; Renstrom, P.A.; Safran, M.R. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal injury in the tennis player. British journal of sports medicine 2012, 46, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjelm, N.; Werner, S.; Renstrom, P. Injury risk factors in junior tennis players: a prospective 2-year study. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 2012, 22, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, K.T.; Pearson, L.T.; Hicks, K.M. The effect of lower inter-limb asymmetries on athletic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos one 2023, 18, e0286942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raya-González, J.; Bishop, C.; Gómez-Piqueras, P.; Veiga, S.; Viejo-Romero, D.; Navandar, A. Strength, jumping, and change of direction speed asymmetries are not associated with athletic performance in elite academy soccer players. Frontiers in psychology 2020, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.; Turner, A.; Read, P. Effects of inter-limb asymmetries on physical and sports performance: a systematic review. J Sports Sci 2018, 36, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.A.; Sato, K.; Burnett, A.; Stone, M.H. Force-production asymmetry in male and female athletes of differing strength levels. International journal of sports physiology and performance 2015, 10, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva-Guerrero, O.; Gadea-Uribarri, H.; Villavicencio Álvarez, V.E.; Calero-Morales, S.; Mainer-Pardos, E. Relationship between Interlimb Asymmetries and Performance Variables in Adolescent Tennis Players. Life 2024, 14, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, I. Warm up revisited–the ‘ramp’method of optimising performance preparation. UKSCA Journal 2006, 6, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Viera, A.J.; Garrett, J.M. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam med 2005, 37, 360–363. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, K. Characteristics and significance of running speed. 2007.

- Kovacs, M.S. Movement for tennis: The importance of lateral training. Strength & Conditioning Journal 2009, 31, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Šarabon, N.; Smajla, D.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Bishop, C. Strength, jumping and change of direction speed asymmetries in soccer, basketball and tennis players. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos’ Santos, T.; Thomas, C.; Jones, P.A.; Comfort, P. Assessing asymmetries in change of direction speed performance: Application of change of direction deficit. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2019, 33, 2953–2961. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, O. La fatiga neuromuscular en el tenis:¿ La mente sobre los músculos? ITF Coaching & Sport Science Review 2014, 22, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Washif, J.A.; Kok, L.-Y. Relationships between vertical jump metrics and sprint performance, and qualities that distinguish between faster and slower sprinters. Journal of Science in Sport and Exercise 2022, 4, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roso-Moliner, A.; Lozano, D.; Nobari, H.; Bishop, C.; Carton-Llorente, A.; Mainer-Pardos, E. Horizontal jump asymmetries are associated with reduced range of motion and vertical jump performance in female soccer players. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation 2023, 15, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, D.; Sundar, B. Training for Lateral Acceleration. ITF Coaching & Sport Science Review 2021, 29, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liddle, N.; Taylor, J.M.; Chesterton, P.; Atkinson, G. The effects of exercise-based injury prevention programmes on injury risk in adult recreational athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports medicine 2024, 54, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madruga-Parera, M.; Bishop, C.; Lake, J.; Brazier, J.; Romero-Rodriguez, D. Jumping-based asymmetries are negatively associated with jump, change of direction, and repeated sprint performance, but not linear speed, in adolescent handball athletes. Journal of Human Kinetics 2020, 71, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).