1. Introduction

This article provides an overview of the current situation regarding the digital transformation of the heritage sector and examines the challenges and opportunities associated with assessing the impact of digital cultural heritage initiatives in Europe. When taking stock of academic research concerning digital culture and heritage, it becomes visible that this is a complex notion not conforming to a singular definition that would encompass all its facets and provide comprehensive reasons why it is important. Recent academic research has, among other issues, delved into various aspects of digital cultural heritage, including digital humanities and digital heritage in AI environment [

1], linked data and cultural heritage [

2], cultural heritage data from the perspective of digital humanities [

3], crowdsourcing and heritage [

4], cultural heritage on social media [

5], etc. Lian and Xie point out that the main current themes concerning digital heritage related research cover issues of relevant technological innovation and its application, information management and technical support, and digitization and preservation of cultural heritage [

6]. While such studies highlight the use and potential of digital tools in cultural heritage, the specific impact of digital cultural heritage projects on broader cultural, social or economic contexts remains a relatively unexplored area [

7].

However, the evolving role of cultural heritage institutions nowadays is closely tied to their ability to create a meaningful impact on society. Clearly communicating the value of digital collections and demonstrating their impact to decision-makers, funders and users is becoming essential to justify current activities and secure continued support for their development and upkeep [

8]. Equally important is that performing internal self-evaluations should allow heritage institutions to check if they are on the right track. Yet, the question remains: How can the success of digital cultural heritage resources and projects be measured, and against which underpinning values should they be evaluated?

In approaching this subject, we consider that culture is “collective memory, dependent on communication for its creation, extension, evolution and preservation” [

9] (p.19). This implies that whenever we discuss culture, communication is always implicit, as our collective knowledge has always been communicated and preserved through the existing cultural communication structures with technologies playing a crucial role in enabling and facilitating those processes [

10]. In other words, the ability to acquire, share, and innovate knowledge is essential for the preservation and development of any culture [

11]. The digital context has paved the way for numerous collaborative and creative processes, with data now serving as a valuable resource for education, arts, etc., while enabling us to share and preserve our cultural memory. Vast amounts of data about human society and culture, both present and past, have become a new frontier for digital initiatives in institutions worldwide. This is the reason why we consider digital heritage to be truly important and where we find its value – in considering it as knowledge resource that should be used in the development of creativity and creating an enabling environment for empowering citizens.

In recent decades, digital culture and digital cultural heritage has gained a more prominent place in the political agenda of the European Union (EU). EU considers cultural heritage as a strategic resource for sustainable development, and this encompasses digital heritage as well. Ambitiously, the European Commission [

12] (p. 8) set the goals for the digital future: “by 2030, Member States should digitise in 3D all monuments and sites that are considered to be cultural heritage at risk, and 50% of the most physically visited cultural and heritage monuments, buildings and sites.” The official EU discourse has shifted from focusing on “preservation” and “access” to emphasizing “digital transformation”. The digitization of cultural heritage has been seen as central to transforming it into new knowledge resources, unlocking opportunities for the development of new services and content [

13]. Moreover, the potential of digital cultural heritage to drive job creation across various economic sectors has been placed in the focus of policymakers, and expectations have been raised that providing access to and enabling the reuse of digital content can generate additional revenue streams for cultural heritage institutions [

14].

However, ensuring that digitized content reaches its intended audience is a challenging endeavor. In practice, heritage institutions strive to balance their missions of preserving and providing access to our shared heritage with the opportunities and challenges brought by the digital age, emphasizing the significance of their collections by digitizing them for both preservation and accessibility [

11]. Cultural heritage institutions are increasing their digital offers with an aim to enhance user experience and attract new audiences. It is evident that participatory practices have become increasingly valuable in the digital heritage sector, transforming public engagement with cultural heritage institutions [

15].

2. Materials and Methods

This paper explores the complex landscape of impact assessment (IA) for digital cultural heritage initiatives within the European Union. Based on a desk research methodology, the research provides a systematic review encompassing: 1) relevant EU-funded projects focused on (digital) heritage impact assessment, with particular attention paid to their outputs such as reports, guidelines, frameworks, and toolkits; 2) relevant academic literature on the subject of impact assessment for digital cultural heritage, identified through a multi-faceted search approach using traditional academic databases, the AI-powered research platform scite.ai, and Google Scholar, with keywords including “impact of digital cultural heritage”, “evaluation of digital cultural heritage” and “impact assessment framework for cultural heritage”; and 3) the current EU policy framework related to digital cultural politics, and the digital transformation of cultural heritage institutions, including key initiatives like Europeana and the Data Space for Cultural Heritage.

This three-pronged approach aimed to ensure a comprehensive and contextualized understanding of the challenges and opportunities associated with measuring the impact of digital cultural heritage within the evolving European policy landscape. Furthermore, during the research on impact assessment frameworks, several other crucial and interconnected concepts emerged, including digital maturity, accountability, resilience, and sustainability. These concepts were considered essential to the broader understanding of the relevance of impact assessment and, consequently, were further explored through a combination of EU policy documents and academic literature to establish their interrelationships within the context of digital cultural heritage.

A critical component of the research involves a comparative analysis of six impact assessment frameworks, including the Balanced Value Impact Model (BVI), the Europeana Impact Playbook, the Change Impact Assessment Framework, Impactomatrix, the MOI Framework, and the SoPHIA Model. These frameworks are evaluated based on their proposed methodologies, specific thematic focus, and the inclusion (or lack thereof) of proposed indicators.

A critical lens was applied throughout the analysis, allowing for a nuanced understanding of the interplay between policy, practice, and conceptual IA frameworks. The analysis focuses on the strengths and limitations of each framework and assesses their suitability for the current capacities and needs of cultural heritage institutions. The insights gained through the reviewed literature, project outputs, and the analysed IA frameworks enabled us to identify key challenges and propose directions for developing more standardized and holistic approaches to impact assessment for digital cultural heritage, emphasizing the need to move beyond data collection to demonstrating meaningful change and long-term sustainability.

3. Results

3.1. Digital Transformation and Data Policies

When the discourse shifted from digitisation and digitalisation to digital transformation, the issue of sustainability became more prominently the focus of both policymakers and heritage practitioners. However, this is not a straightforward issue. Digital transformation goes beyond the operational aspects of cultural heritage institutions; it reshapes their way of thinking. It is not only about technology and resources but also about the people and skills involved [

16]. It is about turning digital cultural assets into products and services that make a meaningful impact on society while ensuring the long-term sustainability of digital resources.

Digitalisation implies the preservation of cultural heritage for future generations (cultural memory objective), as well as reducing costs and energy consumption associated with physical visits to cultural heritage sites (environmental sustainability objective), and this is clearly recognised in The Recommendation of 10.11.2021 on a Common European Data Space for Cultural Heritage [

12]. Nevertheless, heritage sector needs to be mindful of the fact that digital infrastructure has a significant environmental impact. Digitisation is inextricably linked to augmenting the volume of digital data. As the volume of data exponentially increases, it raises energy consumption due to the needed infrastructure, which has significant ramifications for environmental impact. The recently introduced concept of digital sobriety seeks to advocate for reducing the environmental impact of digital projects. This, among other things, entails minimising energy usage throughout the digitisation process, implementing efficient storage solutions, establishing sustainable practices for digital archive management, etc. [

15]. To strike a necessary balance, developing metrics to evaluate the cultural sector’s performance, including its contribution to ecological sustainability is becoming necessity.

Policies play a crucial role in shaping how the cultural sector adapts its communication methods [

11,

17] and data issues are increasingly becoming the subject of European digitisation policies, influencing the creation, distribution and consumption of digital content. The numerous EU strategies around data such as Open Data Strategy [

18], Open Data Directive [

19] or the Copyright Directive [

20] – which aim to regulate data issues (or content), etc. – are at the very core of cultural sector policies. The convergence of digital and sustainability issues is at the core of European Strategy for Data: “… making more data available and improving the way in which data is used is essential for tackling societal, climate and environment-related challenges, contributing to healthier, more prosperous and more sustainable societies” [

21].

The Recommendation of 10.11.2021 on a Common European Data Space for Cultural Heritage [

12] highlights the importance of data in cultural heritage and points towards the EU’s future direction. The openness of mediatized memory has been described as offering an alternative memory boom, characterized by an unfinished past and a revitalized future (Lunenfeld 2011 as cited in [

22]). Linking policy with practice, platforms like Europeana and DARIAH EU drive digital transformation of the sector, facilitating access, reuse, and sharing of digitized heritage. Europeana, a central access point to European online heritage, is seen as the cornerstone for creating the “common data space” for cultural heritage sector and serves as a platform for reusing and sharing digitized heritage materials. In addition to competence pooling from the heritage sector, transforming cultural content to social and economic assets, and informing EU digital cultural policy, Europeana plays a role in fostering the European citizenship by promoting European identity through its rich repository of cultural content [

23]. In 2021, Europeana provided access to 52 million cultural heritage assets, 45% of which could have been reused in various sectors [

12]. Evidently, the value of data is in its openness for use and reuse. To support the use and reuse of digital resources, DARIAH EU serves as a platform to support digitally enabled research in the arts and humanities, facilitating the exchange of knowledge in digital humanities regarding content, methods, tools, and technologies. It assists researchers in utilizing these resources for building, analyzing, and interpreting digital materials while ensuring adherence to best practices, as well as to methodological and technical standards [

3].

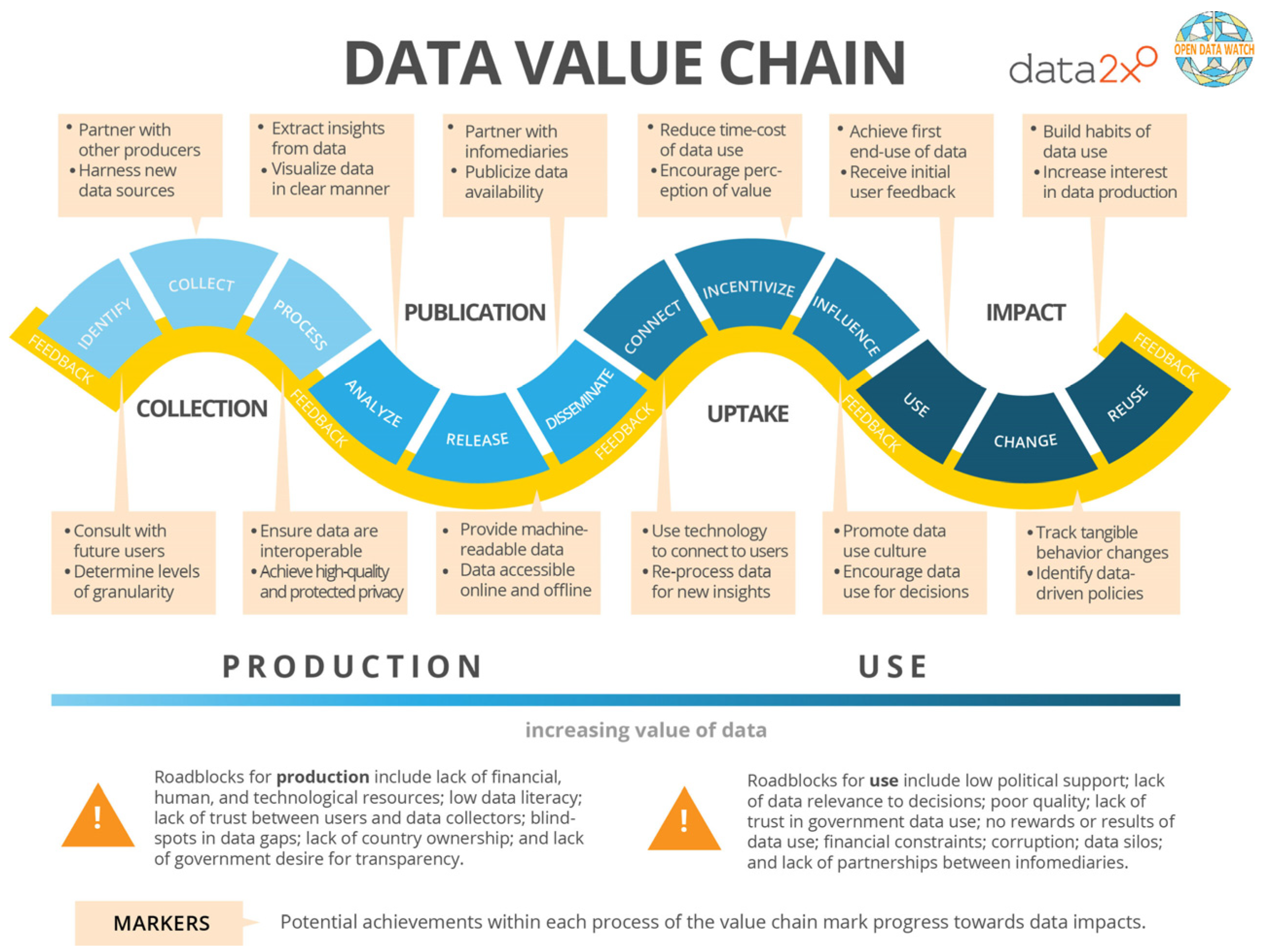

It has been suggested that the success of (digital) technology should be measured by its openness to unanticipated uses—that is, its ability to enable change (Lunenfeld 2011 as cited in [

22]). The data value chain proposed by the Open Data Watch (

Figure 1) points towards a crucial step between data use and reuse – the “change” step. This step emphasizes the importance of tracking tangible behavioural changes resulting from data utilisation. This framework provides a comprehensive view of the data lifecycle, from initial collection to the ultimate impact of data reuse. How to translate this into an evaluation grid for heritage institutions remains an issue to be resolved.

3.2. Managing Digital Change Responsibly: Key Concepts

In the context of the permanent social crisis we are facing, it is essential to highlight concepts that make up the framework for managing cultural heritage institutions today—namely, accounting, resilience, and sustainability are closely interrelated concepts relevant to cultural heritage management [

24], particularly in today’s digitally infused reality in which we still did not fully reach digital maturity.

The Recommendation of 10.11.2021 on a common European data space for cultural heritage [

12] set to maximize the opportunities created by the digital transformation and encourage Member States to help cultural heritage organisations to become more accountable, resilient and sustainable in the future. It underlines that the Member States and cultural heritage institutions should take a “holistic approach” when planning digitisation. This involves considering “the purpose of the digitisation, the target user groups, the highest quality affordable, the digital preservation of the digitised cultural heritage assets, including aspects such as formats, storage, future migrations, continuing maintenance and the necessary long-term financial and staffing resources”[

12].

According to Thomas & Lamm, accountability is “an important component of ensuring pragmatic legitimacy for cultural enterprises that create value, respect the principles of sustainability (moral legitimacy), follow their mission, and deliberate and implement strategies (cognitive legitimacy)” [

25]. Especially in the digital environment, accountability is an important aspect for public institutions. In other words, data is “the raw material for accountability” [

26].

Resilience and sustainability are related but distinct concepts: resilience emphasizes short-term adaptability, while sustainability ensures long-term viability. Cultural resilience represents the ability of a cultural system to withstand adversity, adapt, and evolve [

27]. UN Brundtland Commission has defined sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [

28]. This broad definition points to heritage sector’s responsibility to ensure that heritage resources which is our inheritance from past generations remains a legacy we pass on to the future [

29]. By making efficient management choices and assuming responsibility for their outcomes (being accountable), it is expected that organisations can foster both their resilience and sustainability [

24].

Translating these concepts to the digital context points to the importance of the term digital maturity: “An individual’s or an organisation’s ability to use, manage, create and understand digital, in a way that is contextual (fit for their unique setting and needs), holistic (involving vision, leadership, process, culture and people) and purposeful (always aligned to the institution’s social mission)” [

30]. Digital transformation is evidently a challenging process. Digitizing cultural heritage brings profound changes for heritage institutions, requiring them not only to adopt digital technologies but also to adapt to the digital landscape [

31]. This involves reconsidering the representation, meaning, and, most importantly, the value of digital heritage and its impact on the community.

However, in practice it does not seem that we have reached the maturity point yet. Tanner points out that the assumptions continue to pervade that all digital things are innovative, that agile development can substitute planning, and that if competitors (or Google) are doing something, it is imperative to do it [

32]. On the other hand, the case study by Marsh and others suggests that the impact concerning digitising collections can be defined by the question “What is meaningful and to whom?” [

33] Thus, cultural heritage institutions need to consider their digital activities in the context of their social missions and potential value for their users’ communities and try to make sense of how digital context supports or hinders this.

3.3. From Digitalisation to Impact: Approaches and Challenges

Impact is usually described as something that brings change [

33,

34]. According to Tanner and Deegan [

34], impact can be defined as “the measurable outcomes arising from the existence of a digital resource that demonstrate a change in the life or life opportunities of the community for which the resource is intended”. The concept of impact is rather complex. It can be tangible or intangible, positive or negative. It happens at multiple levels and magnitudes/scales. Moreover, the impact happens over time (e.g., short-term impact or long-term impact) [

33]. Impact can range from individuals to communities or general society and can have various aspects, from social to economic [

35].

By its very nature, the impact is difficult to assess. Most cultural heritage institutions can obtain figures on how much they have spent on their web services, how many visitors visit their site, or how the visitors navigate through their site. However, they struggle with how to relate, for example, high engagement rates to an exact measure of impact. The impact of digital cultural heritage is assessed by evaluating the value of the changes it generates. For this, it is necessary to have assessment tools or frameworks that would enable meaningful evaluations.

Various evaluation methods are used today, including impact assessment (IA). In general, evaluation processes refer to broader approaches that assess a project’s overall performance, effectiveness, and efficiency during or after implementation. In contrast, impact assessment focuses on the specific, long-term effects and outcomes of a project.

Impact assessment is defined in literature as “research that requires setting questions and choosing methods to answer them” (ISO 2014 as cited in [

36]); “process of identifying the future consequences of a current or proposed action” [

37]; “a tool to foster understanding of how strategic decisions about digital resources may be fostering change within our communities.” [

32]; or simply “thinking before acting” (Morrison-Saunders 2018 as cited in [

38]). These definitions emphasize the complex, layered process involved in impact assessment, which demands careful planning and execution. From the definitions above, we can conclude that impact involves an intervention that creates change where the effects of the intervention/project/resource are assessed in relation to its intended purpose and the potential needs of its stakeholders [

39]. It reflects the difference between what would have occurred naturally and what resulted from a specific action or project.

Impact assessment has been first introduced in the heritage sector in the 1980s focusing on UNESCO’s World Heritage sites [

38] but has gained more prominence in recent years. Heritage IA is closely linked to the concept of cultural capital, which includes the economic value of heritage assets [

40], as well as the connection to the history of landscapes and communities, meaning the cultural values derived from heritage [

41]. Additionally, cultural and social values are created through community involvement and everyday participation. Nevertheless, it’s difficult to assign a tangible sense of value to a digital resource or project.

Measuring impact supports an evidence-based approach to managing heritage. Evidence of (digital) impact can be inferred from various sources, including output data, user satisfaction measures, or performance indicators [

7]. Thus, impact assessment involves both quantitative and qualitative methods and indicators. In this regard, Shaw [

8] argues that a comprehensive assessment of digital collections requires a multi-faceted approach, combining statistics, surveys, user studies, usability testing, and web analytics. Yet, Tanner [

32] remarks that, so far, primary measures of digital heritage have predominantly focused on web statistics, anecdotal information, or evaluations of outputs, such as the quantity of digitised materials, rather than assessing the value and change derived from these efforts.

The basic elements in measuring impact are indicators or data we interpret. Tanner proposes that indicators are the most critical part of the impact assessment because they measure progress toward set goals [

32] and should reveal the change triggered by the project/action that is being evaluated. They are usually specifically developed depending on the proposed action. For example, Fukuyama and Tanner proposed a set of 13 potential indicators for the UK Web Archive (UKWA) which can be used for UKWA, but also other web archiving organisations [

36]. To be usable, they must be specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and timely (SMART) and must meet quality criteria. This means that the functionality of each indicator needs to be evaluated against established benchmarks for effective and ineffective indicators [

36]. Finally, for indicators to be useful, they must be set as opposed to some baseline values that have been registered before the project has begun, and against which change can be measured. Tanner underscores that the digital domain is a challenging environment for identifying suitable indicators due to the limited availability of historical data, i.e. the absence of effective baselines, which can hinder meaningful analysis [

32].

To successfully perform an impact assessment, the initial step is deciding what will be monitored and how: what data sources are relevant and available to serve as indicators, which are the relevant questions for qualitative analysis, which methods will be used [

39]. All said above indicates that this is not a simple task and requires some underpinning models that would provide the framework for the IA analysis.

3.4. Exploring EU Initiatives for Impact Assessment and the Challenges of Measurement

As argued above, the adaptability of content to different types of audiences is as important for the heritage sector, as well as the increase of its engagement with digitised cultural heritage. To achieve this, we concur with Shaw’s claim that the development and preservation of high-quality digital collections that respect community standards and follow best practices is a complex and resource-intensive endeavour and engaging in their meaningful assessment further compounds this complexity [

8].

The heritage sector is increasingly aware of the need to evaluate the success of its projects and the impact they have achieved on the community they serve. However, they lack knowledge and skills to fully embrace this practice. To support the heritage sector in reaching digital maturity, Culture24’s flagship collaborative action research program

Let’s Get Real since 2010 provides a capacity building that enables better understanding of what impact means in the context of digital heritage. The first edition addressed the question “How to Evaluate Online Success” by exploring what success looks like for different organizations and the tools available to measure it [

42]. Subsequent editions focused on various aspects of digital activities, such as aligning digital practice with social purpose, assessing whether institutions’ content is “fit for purpose”, fostering deeper human connections through digital channels, and understanding and measuring digital engagement. Such in-depth exploration helped participating organizations better understand what impact means for them, by enabling them to measure their online performance more accurately and meaningfully and thus reaching better informed decisions regarding their online activities [

42].

To assess the present state of development of tools for impact assessment of (digital) heritage projects we have conducted a desk review of recent project reports that have aimed at proposing new frameworks or methods of evaluating the impact in the heritage domain. We analysed six impact assessment frameworks: the Balanced Value Impact Model (BVI), the Europeana Impact Playbook, the Change Impact Assessment Framework, Impactomatrix, the Museums of Impact Framework (MOI), and the Social Platform for Holistic Heritage Impact Model (SoPHIA); looking into their methodologies, thematic focus, and the presence or absence of proposed indicators and tried to detect challenges of measurement. We shall present our findings in the table below.

4. Discussion

Starting from the different premises, six examples described above provide various frameworks that enable heritage institutions to rethink what impact means for them in the context of their missions by providing them with tools that helps them asking relevant questions and choosing methods to answer them. While the first four examples focus exclusively on heritage in a digital context, the last two examples are addressing heritage sector in general but are still relevant for the digital heritage projects and resources.

IA frameworks such as the SoPHIA Model, MOI Framework, and Change Impact Assessment Framework primarily emphasize tangible outcomes like knowledge creation, creativity, innovation, sustainability, etc. directly addressing the scope of impact through their thematic focus. In contrast, the BVI Model and the Europeana Impact Playbook, which is based on it, focus on the fundamental values that drive these outcomes. For instance, the BVI Model utilizes five Value Lenses to guide impact assessment, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of the core values linked to digital cultural heritage experiences. Meanwhile, Impactomatrix appears to integrate elements of both approaches.

While those IA frameworks provide different lenses on variety of impact areas and provide general guidelines for potential applications of the framework, only some of them have developed a concrete methodology guiding the assessment plan that facilitates implementing the specific approach that depends on the needs of the specific heritage institution. This highlights a key challenge: effectively translating the framework into concrete evaluation action within the unique context of each institution by deciding on evaluation goals and timeframe, research methods to be used, adequate indicators that need to be collected and interpreted, etc. This leads us to the conclusion that standards for IA concerning digital heritage are not yet agreed upon.

We can conclude that despite decades of continuous investment in the development of digital cultural resources within an ever-evolving digital landscape, there is still no clear consensus on how to assess the impact of digital heritage resources and projects. The European Commission [

12] highlights the need for a “holistic approach” for Member States and cultural heritage institutions when planning digitization initiatives. This is reflected in the IA frameworks described, which take a broader view of the wider implications of such efforts. However, progress is hindered by a combination of factors: financial constraints often limit the resources available for IA, a lack of skilled personnel and institutional understanding poses a significant barrier, and the complexity of digital heritage projects makes effective assessment a challenging process.

This indicates that understanding the impact of digital resources and demonstrating the change they have produced remains a challenge. As the data value chain (

Figure 1) illustrates, the ultimate goal of data use is to achieve change (through reuse), which aligns with the fundamental understanding that impact is realized through meaningful change. This principle is well-reflected in the IA models presented in

Table 1. The point is that, by identifying the value of that change or by describing it as a concrete outcome, cultural heritage institutions aim to demonstrate the true significance and effectiveness of their digital efforts.

The described examples of IA frameworks developed in the recent time point to the fact that the heritage sector increasingly understand the importance of demonstrating the impact of their activities and resources on the communities they are serving. However most cultural institutions have not yet mastered the IA tools and methods to appropriate it in their work, as even with several existing IA frameworks in place, current assessments of digital heritage in majority of heritage institutions predominantly rely on metrics like web statistics and the quantity of digitized materials, overlooking the crucial need to evaluate the true value and impact of these efforts. Ultimately, at this point the key benefit of utilizing IA frameworks is the valuable learning process inherent in the evaluation itself.

To translate proposed frameworks into practical applications and strengthen the sector, achieving digital maturity and enhancing digital skills in the heritage field is essential. This requires a strategic approach that extends beyond merely sharing information on the topic. Navigating this complex landscape demands digitally literate leadership to ensure that heritage professionals acquire the necessary digital competencies and can effectively adapt to ongoing changes. Cultivating these skills across the entire team requires dedicated time and resources. In essence, cultivating a digitally literate workforce, investing in resources, and conducting evaluations thorough impact assessment frameworks are all crucial elements for building resilience in cultural heritage institutions and ensuring their sustainability.

Finally, as sustainability is becoming an integral part of EU politics, (digital) cultural heritage, impact assessment frameworks should enable lenses through which digital cultural heritage initiatives can be evaluated, not only for achieving their short-term objectives but also fostering long-term sustainability and thus contributing to the preservation and vitality of cultural heritage in the digital age. It is clear that the impact assessment of digital cultural resources is relevant for decision making processes in culture and are equally of interest for the policy makers as such assessments provide relevant data for evidence-based policy making that we are striving for.

When conducting this research, it became clear that comprehensive literature specifically addressing digital cultural heritage IA is not abundantly present. While IA frameworks are emerging in the recent years, they remain in an initial stage. Although they provide a good starting point, substantial research is still needed. Further research, including more case studies, is needed to fully evaluate the effectiveness and applicability of these IA frameworks, as a comprehensive understanding of digital initiatives requires exploring not only measurable outcomes but also the less tangible, value-driven impacts and their long-term sustainability implications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.U; methodology, A.U.; investigation, B.L.H.; resources, B.L.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L.H; writing—review and editing, A.U; supervision, A.U; project administration, A.U.; funding acquisition, A.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan 2021-2026, NextGeneration EU program, through the project CULTMED— – Interdisciplinary Research on Cultural and Media Policies and Practices: Developmental and Democratic Potentials (December 31, 2023 – December 31, 2027). This funding was provided under the Program Agreement (Class: 643-02/23-01/00016, Reg. No.: 533-03-23-0002, dated 8 December 2023) between the Ministry of Science, Education and Youth and the Institute for Development and International Relations (IRMO), Zagreb, Croatia. The specific allocation for this project was outlined in the Decision on Allocation of Financial Resources (IRMO, Class: 402-03/23 01/17, Reg. No.: 251-768-04-23-5, dated 11 December 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EU |

European Union |

| DARIAH |

Digital Research Infrastructure for the Arts and Humanities |

| IA |

Impact Assessment |

| BVI |

Balanced Value Impact |

| SoPHIA |

Social Platform for Holistic Heritage Impact Assessment |

| MOI |

Museums of Impact |

| 3D |

Three-dimensional |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Breathnach, C.; Margaria, T. Digital Humanities and Cultural Heritage in AI and IT-Enabled Environments. In Bridging the Gap Between AI and Reality. AISoLA 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Steffen, B., Ed.; Springer: Cham, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.; Heravi, B. Linked Data and Cultural Heritage: A Systematic Review of Participation, Collaboration, and Motivation. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasovac, T.; Chambers, S.; Tóth-Czifra, E. Cultural Heritage Data from a Humanities Research Perspective: A DARIAH Position Paper; 2020. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-02961317/document (accessed on February 3, 2025).

- Navarrete, T. Crowdsourcing the Digital Transformation of Heritage. In Digital Transformation in the Cultural and Creative Industries. Production, Consumption and Entrepreneurship in the Digital and Sharing Economy; Massi, M., Vecco, M., Lin, Y., Eds.; 2020; pp. 99–116.

- Hu, L.; Olivieri, M. Cultural Heritage on Social Media: The Case of the National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo Da Vinci in Milan. In Digital Transformation in the Cultural and Creative Industries. Production, Consumption and Entrepreneurship in the Digital and Sharing Economy; Massi, M., Vecco, M., Lin, Y., Eds.; 2020; pp. 211–223.

- Lian, Y.; Xie, J. The Evolution of Digital Cultural Heritage Research: Identifying Key Trends, Hotspots, and Challenges through Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego, À. Measuring the Impact of Digital Heritage Collections Using Google Scholar. Information Technology and Libraries 2020, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.F. Making Digitization Count: Assessing the Value and Impact of Cultural Heritage Digitization. Proc. IS&T Archiving 2016. [CrossRef]

- Foresta, D.; Mergier, A.; Serexhe, B. The New Space of Communication, the Interface with Culture and Artistic Activities; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Uzelac, A. How to Understand Digital Culture: Digital Culture – A Resource for a Knowledge Society. In Digital Culture: The Changing Dynamics; Uzelac, A., Cvjetičanin, B., Eds.; Institut za razvoj i međunarodne odnose (IRMO): Zagreb, 2008; pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Uzelac, A.; Obuljen Koržinek, N.; Primorac, J. Access to Culture in the Digital Environment: Active Users, Re-use and Cultural Policy Issues. Medijska istraživanja 2016, 22, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation (EU) 2021/1970 of 10 November 2021 on a common European data space for cultural heritage. Official Journal of the European Union, 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32021H1970 (accessed on February 5, 2025).

- Kuzman Šlogar, K.; Žugić Borić, A. (Eds.) Digital Humanities & Heritage; Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research: Croatia, 2024; Available online: https://www.ief.hr/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DHH-proceedings_PDF.pdf (accessed on February 2, 2025).

- EIF-KEA. Market analysis of the CCs in EUROPE; 2021. Available online: https://keanet.eu/wp-content/uploads/ccs-market-analysis-europe-012021_EIF-KEA.pdf (accessed on February 5, 2025).

- Drabczyk, M.; Dimou, A.; de Koning, J.; Mafredini, F.; Svorc, J.; Peeters, R. Comprehensive Guide of the Benefits, Opportunities, Risks and Gaps in the Management of Cultural Heritage Digitisation; REEVALUATE, a European Union Horizon Research and Innovation programme, 2024. Available online: https://reevaluate.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/REEVALUATE-D1.1-Comprehensive-guide-of-the-benefits-opportunities-risks-gaps-in-the-management-of-CH-digitisation_final.pdf (accessed on February 5, 2025).

- Finnis, J.; Kennedy, A. Guide to Digital Transformation in Cultural Heritage Building Capacity for Digital Transformation Across the Europeana Initiative Stakeholders; 2022. Available online: https://digipathways.co.uk/resources/guide-to-digital-transformation-in-cultural-heritage/ (accessed on February 2, 2025).

- Uzelac, A.; Primorac, J.; Lovrinić Higgins, B. Digital Cultural Policy in Croatia. Searching for a Vision. In Digital Transformation and Cultural Policies in Europe; Hylland, O.M., Primorac, J., Eds.; Routledge: 2024; pp. 119–140. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Open Data. An Engine for Innovation, Growth and Transparent Governance. COM(2011) 882 final, 2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0882:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on February 5, 2025).

- Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on open data and the re-use of public sector information (recast). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019L1024 1 (accessed on February 5, 2025).

- Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC (Text with EEA relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/790/oj (accessed on February 5, 2025).

- European Commission. European Strategy for Data; 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0066 (accessed on February 5, 2025).

- Hoskins, A. Lundby, K., Ed.; 29. The Mediatization of Memory. In Mediatization of Communication; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Boston, 2014; pp. 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurro, C.; Plets, G.; Verheul, J. Digital Heritage Infrastructures as Cultural Policy Instruments: European and the Enactment of European Citizenship. International Journal of Cultural Policy 2023, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliacani, M.; Toscano, V. Accounting for Cultural Heritage Management. Resilience, Sustainability and Accountability; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.E.; Lamm, E. Legitimacy and Organizational Sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics 2012, 110, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEAG. A World that Counts: Mobilising the Data Revolution for Sustainable Development; The United Nations Secretary-General’s Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable Development, 2014. Available online: http://www.undatarevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/A-World-That-Counts.pdf (accessed on February 2, 2025).

- Holtorf, C. Embracing Change: How Cultural Resilience Is Increased Through Cultural Heritage. World Archaeology 2018, 50, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Brundtland Commission. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; UN-Dokument A/42/427; Geneva, 1987.

- SoPHIA Consortium. Deliverable D3.1: Toolkit for Stakeholders, 2021.

- Finnis, J.; Kennedy, A.; The Digital Transformation Agenda and GLAMs. A Quick Scan Report for Europeana Culture24; 2020. Available online: https://pro.europeana.eu/files/Europeana_Professional/Publications/Digital%20transformation%20reports/The%20digital%20transformation%20agenda%20and%20GLAMs%20-%20Culture24%20findings%20and%20outcomes.pdf (accessed on February 2, 2025).

- Navarrete, T. Chapter 12: Digital Cultural Heritage. In Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage; Rizzo, I., Mignosa, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: 2013; pp. i-i.

- Tanner, S. Delivering Impact with Digital Resources: Planning Strategy in the Attention Economy; Facet Publishing: London, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, D.E.; Punzalan, R.L.; Leopold, R.; Butler, B.; Petrozzi, M. Stories of Impact: The Role of Narrative in Understanding the Value and Impact of Digital Collections. Archival Science 2015, 16, 327–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, S.; Deegan, M. Measuring the Impact of Digitized Resources: The Balanced Value Model. 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHeritage), 2013; 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, K. Exploring Digital Libraries: Foundations, Practice, Prospects. Facet Publishing: London, 2014.

- Fukuyama, J.; Tanner, S. Impact Assessment Indicators for the UK Web Archive. Performance Measurement and Metrics 2021, 23, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partidário, M.; den Broeder, L.; Croal, P.; Fuggle, R.; Ross, W. Impact Assessment; International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA): Fargo, ND, USA, 2012; Available online: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/eia/documents/WG2.1_apr2012/Fastips_1_What_is_IA.pdf (accessed on February 3, 2025).

- Court, S.; Jo, E.; Mackay, R.; Murai, M.; Therivel, R. Guidance and Toolkit for Impact Assessments in a World Heritage Context; UNESCO, 2022. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidance-toolkit-impact-assessments/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Tišma, S.; Uzelac, A.; Franić, S. Cjelovita procjena učinka intervencija u području kulturne baštine - SoPHIA model; Jesenski i Turk: Zagreb, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Chapter 23: Assessment of Value in Heritage Regulation. In Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage; Rizzo, I., Mignosa, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: 2013; pp. 456–469.

- Beel, D.; Wallace, C.D. Gathering Together: Social Capital, Cultural Capital and the Value of Cultural Heritage in a Digital Age. Social & Cultural Geography 2018, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnis, J.; Chan, S.; Clements, R. How to Evaluate Online Success? A New Piece of Action Research. In Museums and the Web 2011: Proceedings; Trant, J., Bearman, D., Eds.; Archives & Museum Informatics: Toronto, 2011; Available online: https://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2011/papers/how_to_evaluate_online_success_a_new_piece_of_.html (accessed on February 5, 2025).

- Tanner, S. Measuring the Impact of Digital Resources: The Balanced Value Impact Model; 2012. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/30677096.pdf (accessed on February 3, 2025).

- Tanner, S.; Europeana – Core Service Platform. MILESTONE EMS26: Recommendation Report on Business Model, Impact and Performance Indicators; 2016. Available online: https://pro.europeana.eu/files/Europeana_Professional/Projects/Project_list/Europeana_DSI/Milestones/europeana-dsi-ms26-recommendation-report-on-business-model-impact-and-performance-indicators-2016.pdf (accessed on February 3, 2025).

- Tanner, S. Using Impact as a Strategic Tool for Developing the Digital Library via the Balanced Value Impact Model. Library Leadership and Management 2016, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europeana Foundation. Europeana Impact Playbook Phase One: Impact Design; 2017. Available online: http://impkt.tools (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Europeana Foundation. Europeana Impact Playbook Phase Two: Assess ;2020. Available online: http://impkt.tools (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Europeana Foundation. Europeana Impact Playbook Phase Three; 2021. Available online: http://impkt.tools (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Europeana Foundation. Europeana Impact Playbook Phase Four, V.1; 2022. Available online: http://impkt.tools (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Tartari, M.; Manfredini, F.; Pilati, F.; Sacco, P.L. Change Impact Assessment Framework; inDICEs, a European Union Horizon Research and Innovation programme, 2023.

- Sacco, P.L.; Ferilli, G.; Tavano Blessi, G. From Culture 1.0 to Culture 3.0: Three Socio-Technical Regimes of Social and Economic Value Creation through Culture, and Their Impact on European Cohesion Policies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEMO. “New Tool Moi Framework Helps Museums Increase Their Social Impact”. 2022. Available online: https://www.ne-mo.org/news-events/article/new-tool-moi-framework-helps-museums-increase-their-social-impact/ (accessed on February 2, 2025).

- MOI (Museums of Impact). Facilitator’s Guidelines; 2022. Available online: https://www.ne-mo.org/fileadmin/Dateien/public/Partner_Projects/2019-2022_MOI_Framework/MOI-Guidelines_for_facilitators.pdf (accessed on February 2, 2025).

- Marchiori, M.; Anastasopoulos, N.; Giovinazzo, M.; Mc Quaid, P.; Uzelac, A.; Weigl, A.; Zipsane, H. (Eds.) An Innovative Holistic Approach to Impact Assessment of Cultural Interventions: The SoPHIA Model; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-88-15-29973-4. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).