1. Introduction

The future of the currently vacant former Dennys Lascelles Wool store, aged more than a hundred and located at 20 Brougham Street, is under dispute between the state government and a property developer (

Figure 1). This building was once part of the old Dennys Lascelles wool store. The store had different parts: the current National Wool Museum Building, which is now a museum and protected for its heritage, and the legendary bow truss building, also heritage listed. Unfortunately, the bow truss building got demolished in the nineties. Now, there's a new TAC building on that spot. As for the building we're talking about, it's been empty for many years. The state government raised opposition against the proposed design reuse plan with the argument that the developer has neglected the building’s contribution to a valuable part of Geelong’s history and identity Tippet (2022). In the meantime, Heritage Victoria declined the inclusion of this building in the Victorian Heritage List and rejected its nomination proposal, although the former wool store is part of an exceptional collection of former wool store buildings located in the Geelong CBD and represents a tangible legacy of the city's role as the wool capital of Victoria (Rowe and Jacobs, 2017).

The founder of this wool store company, Charles John Dennys, has been described as the father of Geelong’s wool industry. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, his company, Dennys Lascelles Austin & Co, established numbers of wool stores concentrated within a city block, strategically positioned between the commercial hub of Geelong and the harbour vicinity in Corio Bay, which not only housing the wool bales but also displaying them for potential buyers (Allom, 1986). Constructed between 1872 and 1926-30, these wool stores covered a substantial portion of the city block in Moorabool and Brougham Streets. Within this complex of buildings, two of them have evaded demolition, one has been adapted into a Geelong National Wool Museum, but the other, as a legacy of the expansion of Dennys Lascelles in the early 1950s, has sat vacant for decades with its future being under a debate and at risk of unresponsive redevelopment.

2. What should we preserve: Authoritative Heritage Discourse ( AHD)

Since the initial stages of acknowledging the imperative for protecting world heritage, historic landscapes generally faced two dominant black-and-white scenarios based on international corporations’ defined scope of heritage. In accordance with their approved rules, regulations, principles, and charters, if a historic landscape were of Outstanding Universal Values (OUV), it would be heritage-listed and enter the process of preserving and showcasing; otherwise, it would be subject to potential demolition and subsequent reconstruction. This approach to heritage has limitations and potentially can lead to counterproductive effects.

In the context of Geelong and specifically the subject case, criteria for the assessment of significance are based on two documents of the Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance (2013) and its Practice Notes. Having undergone several amendments, this charter has shifted its focus from traditional fabric-centred approaches to adopting evolving concepts of heritage, dynamic economic or political conditions, and a wide array of distinct locales (Avrami et al., 2019). However, its overreliance on the intrinsic values of places and focus on preservation still can potentially hinder the advancement of adaptive reuse or developmental projects, besides the challenges associated with its practical implementation (Zancheti et al., 2009).

As such, the scenario in which historical materials are without assigned heritage significance is susceptible to memory and legacy loss, and the buildings are also subject to destruction, which is inapposite with sustainable frameworks. Following the more recent registered conventions and charters, other heritage dimensions have received recognition, and it is not merely monumental and grand tangible buildings but also intangible as a point of history that matters. In this term, current heritage approaches acknowledge both intangible and tangible, as physical landscapes cannot be separated from intangible immaterial people’s experiences (Meskell, 2015). However, buildings like Dennys Lascelles wool store still have not gained the protection layer, and their future fate is trapped amidst debates.

The scenario in which buildings have attained heritage designation and acquired preservation has also prompted specific limitations. This value-based viewpoint of heritage, mostly through the lens of museumification approaches, objectified historical materials and was to recognise them as precious objects that should be preserved and curated carefully. These traditional views of heritagisation provided by earlier conventions and charters have presumed heritage to be aesthetically pleasing static material, non-renewable, fragile, with innate values and concerned with physical preservation (Smith and Akagawa, 2008). Smith (2006) critically called this viewpoint on approaching heritage ‘Authorised Heritage Discourse’ (AHD), Harrison (2013) called it ‘Official Heritage’, and Lesh (2022) called it the value-based model of conservation.

During the last two decades, Critical Heritage Studies (CHS) supporters have examined the range of cases and presented that AHD approach and the mere concentration on tangible aspects of heritage can elicit a myriad of shortcomings, such as (i) consumerist practices in which heritage and memory turn into sell point and industry, (ii) commodification and displacement (social and cultural evacuation of space as a result of gentrification and space cleansing) (iii) inequality and historical denialism, and (iv) hegemonic practices over minority groups during religious and ethnic conflicts by oppressing or empowering them, just to name a few (Smith, 2002; Herzfeld, 2006; Apaydin, 2020). Another drawback, which stems from this tangible and objectified viewpoint ending up with strict physical preservation, is the condition of ignoring the economic pressure for resource development and urban growth in line with sustainability principles.

Parallel to the ever-changing world, the requirements of built environments and their societies keep inevitably transforming. Accordingly, the heritage definition, with its dynamic nature, is not exempt from this and ‘Static government-endorsed definitions’ are not well-suited to such fluid circumstances (Fairclough, 2009, p. 34). Heritage advocates in critical heritage studies believe the meaning of the past is constantly redefined in each present setting (Gentry and Smith, 2019). In critical views on AHD, heritage is not a past product to be discovered but rather a contemporary process and action (Tunbridge and Ashworth, 1996; Harvey, 2001; Smith, 2006; Harrison, 2013). In this term, Faro Convention’s main suggestion is to challenge the conventional approach of heritage as a valuable asset to be preserved and to encourage viewing it as a resource to be actively utilised and exploited for various purposes (Fairclough, 2009, p. 41).

However, given the higher preservation status assigned to historic urban areas compared to other parts of the city, it is difficult to implement different strategies except those involving strict preservation (Gravagnuolo et al., 2019), and this results in unsustainability. Therefore, the two conventional scenarios for historical landscapes can potentially result in unsustainability. It must be noted that preserving buildings in their original state encompasses various issues and challenges like inadequate insulation, high embodied carbon, water inefficiency, environmental degradation, and limited adaptability, to name a few. As such, recent studies on curated decay, toxic substances, urban mining, and the circular economy (CE) have brought forth pivotal viewpoints regarding alternative prospects for built heritage. In this manner, waste management and material reuse practices are starting to challenge the conventional notions of heritage that categorise elements of the built environment as either ‘value-bearing’ or ‘of no value’ and encourage a more inclusive and holistic approach to heritage management (Ross and Angel, 2020).

In this term, if we shift from the long-lasting traditional paradigm that development undermines conservation and recognise that the transformative potentials of historical spaces can be consistent with heritage preservation, their future fate can be aligned with the sustainable ethics of not generating waste and heritage decay can be mitigated (Arlotta, 2020; McCarthy and Glekas, 2020). Also, there has been a rising interest in exploring methods for design revolving around the reuse of reclaimed materials due to the magnitude of waste produced from demolition activities, resource scarcity and landfill burden (Ross and Angel, 2020). Adaptive heritage reuse not only ensures the preservation of our historical landscapes but also adapts them to meet the requirements of the present by fostering socially inclusive environments, driving economic growth, and promoting environmental sustainability within cities (Lesh, 2022).

In the meantime, this modification process of making useful responses for the current purpose of buildings can also sacrifice aspects of their historical significance. This can be resolved by recognising and representing the plurality of heritage narratives through innovative heritage approaches like digital heritage. So, this paper intends to bring affect theory as an additional complementary attribute for heritage preservation besides digital theory as a tool to augment the range of choices for preserving various aspects of heritage. This can be applied in the situation of being left with no option other than modifying and removing a part of the heritage in conditions with irresolvable issues like safety concerns, heat waste, unsustainability etc., as the ultimate goal is to make the building functional.

3. Circular City- Recycling, Reuse and Repurpose:

A circular city embraces the principles of the circular economy throughout its urban landscape, forming sustainable systems that optimise resources and eliminate waste. These cities foster local economies by extending product life, reusing, refurbishing, remanufacturing, and recycling while transitioning from linear to circular models. Collaboration across diverse aspects, including humans, businesses, systems, and infrastructure, drives this transformation. In the circular economy, materials circulate without waste, creating resilient and inclusive urban spaces that benefit all residents. The circular city is closely connected with the circular economy, a closed-loop system that uses waste as a resource. As Foster (2020) states:

‘Circular Economy is a production and consumption process that requires the minimum overall natural resource extraction and environmental impact by extending the use of materials and reducing the consumption and waste of materials and energy. The useful life of materials is extended through transformation into new products, design for longevity, waste minimisation, and recovery/reuse, and redefining consumption to include sharing and services provision instead of individual ownership. A CE emphasises the use of renewable, non-toxic, and biodegradable materials with the lowest possible life-cycle impacts. As a sustainability concept, a CE must be embedded in a social structure that promotes human well-being for all within the biophysical limits of the planet Earth.’

Hence, the existing building stocks, whether historic, partially demolished or heritage, are considered resources for a circular city. Considering the city of Geelong as a case, where the city and its surroundings are changing as large businesses close and are replaced by luxury residences, hotels, and new office buildings, among other things. As a result, the once-industrial town and its associated architecture are quickly fading from city dwellers’ memories. As a result of development, the disappearance of visible and intangible memories raises concerns about voids or untold histories in the city’s industrial past and heritage. While much of Geelong’s CBD is being reshaped for the twenty-first century with new buildings, refurbished structures, alleyways, and new activities, certain areas of the CBD continue to be gaps/voids with empty, abandoned buildings, dark alleys, and vacant lots. In this context, a circular economy could be used as a strategy to mitigate this consumption by preserving and reusing historic buildings rather than demolishing and rebuilding them.

Heritage economics examines cultural heritage assets as integral components of a city’s cultural capital within the context of urban conservation. In such contexts, a heritage asset is perceived as more than an entity possessing mere economic value; it encapsulates cultural significance. This amalgamation of cultural and economic value imparts enduring worth over time, generating a continuum of services, consumable or utilisable in the production of additional goods and services (Throsby, 2001).

When we aim to match old historical assets with new needs and uses, the adaptive reuse of cultural heritage often requires making significant interventions (Douglas, 2006; Bullen and Love, 2011). Thoughtful use of materials and people to take care of, maintain, and make use of heritage assets creates a lasting flow of valuable things and services. This makes adaptive reuse a meaningful part of the creative economy. As stated by Ost (2021).

‘Heritage conservation is the economic process of providing and investing additional resources in cultural capital to keep it generating cultural and economic values in the future.’

In the context of Geelong, the fate of industrial vacancies predominantly ends in abandoned sites waiting to be demolished or transformed if not listed as heritage. However, as architecture, these buildings are the only tangible evidence, the paramount query that reminiscences the historic narrative of the city and the place. Certainly, the importance of preserving historic buildings to maintain their historical, aesthetic, and architectural value is widely recognised.

One approach to preserve these values is by skilfully using the existing structure of the buildings. This means restoring, recycling, and repurposing old buildings while also safeguarding their unique architectural features and traditional methods that make them environmentally sustainable. However, this presents a challenge in two directions.

Firstly, if a building is considered a heritage site and protected by certain regulations (AHD), how can we make changes to it without losing its historical significance? Especially when we need to adapt it to new functions and roles in a fast-changing world. Sometimes, this even requires changing the infrastructure around the building to suit its new purpose.

On the other hand, if the building isn’t officially recognised as a heritage site, how can we keep the intangible historical and urban values it holds, whether we decide to tear it down or completely renovate it to match today’s needs? This is a challenge we’re grappling with right now. In our case, the core of this issue revolves around the Denny Lascelles wool store. The portion with heritage status was completely demolished, while the remaining part isn’t officially recognised as heritage and is seemingly viewed as a basic abandoned structure, open to demolition and reconstruction, as we explained at the beginning of this paper.

In a previous study (Rashid et al., 2021), the team tried to uncover and revive the story of the missing section using digital tools. Now, in this paper, we’re further investigating the potential of today’s digital tools and the concept of ‘affective heritage.’ We’re doing this within the context of a circular city, aiming to safeguard the city’s architecture and cultural capital.

4. Affect and Heritage:

‘Adaptive reuse’ prioritises new purposes over conserving original heritage, especially when defined by the ‘authorised heritage discourse’ (AHD) (Smith and Campbell, 2017). We explore how a broader heritage definition can overcome AHD limitations while preserving historical value. This paper introduces ‘affective heritagisation,’ where existing building value mediates between program needs and heritage, fostering a symbiotic relationship between architecture and history.

According to David Lowenthal, heritage is a celebratory aspect of history, not an in-depth investigation. Our Geelong ‘Wool Store Precinct’ subtly celebrates the wool industry, avoiding ‘heritagization’ and ‘commodification’ (Micieli-Voutsinas and Person, 2020; Thouki, 2022). Carman (2003), an archaeologist, explains heritage’s emergence from categorisation, influenced by curatorial agendas, which Denny Lascelles does not fit with.

Tolia-Kelly et al. (2016) state heritage engagements are primarily emotional responses to triggers like pain, joy, nostalgia, and belonging. Zeisel (2006) underscores understanding human perception for appropriate built environment design, beneficial for heritage maintenance on the Denny Lascelles Wool store and similar projects.

‘Heritagisation,’ a term from the late 20th Century, transforms history into exhibits for cultural tourists. Fluid definitions challenge this concept and the dominant ‘authorised heritage discourse’ (Smith and Waterton, 2012). ‘Heritagisation’ is a dynamic process, evolving based on research, discourse, cultural values, and various group involvement (Kolesnik and Rusanov, 2020)

‘Affect Theory’ explains how experiences impact us physically and mentally. Tolia-Kelly et al. (2016) note heritage engagements are primarily emotional responses. Fielding (2022) expands this beyond emotions, involving mundane interactions, information, and others’ reactions, affecting perception. For Fielding, affect theory in heritage is more than emotional manipulation; it’s about how understanding and reacting to the past impact present life. Affective heritagization suggests heritage through materiality, space, culture, and history.

Adaptive reuse of historical buildings prioritises new programs over heritage preservation, sparking tension between conflicting priorities, especially within the ‘authorised heritage discourse.’ This discourse perceives heritage as ‘material, non-renewable, and fragile.’ To reconcile these concerns, the concept of ‘affective heritagization’ emerges, recognising the active role of existing structures in balancing programmatic needs and heritage significance. Focusing on the Dennys Lascelles Wool store, this research highlights the importance of ‘historic narrative’ in crafting a meaningful heritage experience.

Memory encompasses information storage and recall, while nostalgia triggers emotional responses from physical and non-physical cues. Despite negative connotations, nostalgia can deepen engagement with history. For successful adaptive reuse and experience-centred architecture, emotions like nostalgia must be understood.

The Dennys Lascelles Wool store offers a model for heritage projects that emphasise the spatial and textural facets of the original structure, foregoing ‘heritagization’ and ‘commodification.’ This approach prioritises an affective architectural experience, redirecting public learning towards emotional heritage understanding.

Heritage discourse has evolved into dynamic understandings, with affect theory exploring how experiences impact us. Affective heritagization proposes heritage through emotional triggers, fostering personal engagements. Ultimately, heritage emerges from interactions with material culture, shaping current social and political narratives.This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

5. Discussion: Digital heritage and affective preservation

This study critically explores the potential of digital technology to address ‘affective heritage,’ which simultaneously preserves building memories and repurposes them within the context of the circular economy. Grounded in the notion that architecture offers insights into human nature, values, and culture (Prakash and Scriver, 2007), the project employs digital tools to meticulously reconstruct Geelong’s wool industry history for widespread dissemination. The concept of ‘Virtual heritage’ enables non-invasive monument restoration through immersive multimedia experiences (Abdelmonem, 2017), effectively benefiting conservators, historians, archaeologists, and urban designers by ensuring the preservation of historical buildings within the principles of the circular economy. While 3D models considerably aid in the restoration process, capturing intangible values remains a notable challenge for architectural historians.

The study takes a comprehensive approach by effectively integrating digital technologies to capture both tangible and intangible memories (Richards and Duif, 2019). Understanding a building’s significance within the present context but devoid of traditional interactions poses a unique challenge (Abdelmonem, 2015). Although architecture inherently encapsulates collective memories, the process of engagement with them can be intricate and nuanced (Connerton, 1989). The study itself revolves around the concept of ‘Affective Heritage’, which seeks to broaden heritage understanding by meticulously examining historic structures to holistically capture human experiences. The ultimate goal of the endeavour is to bridge temporal gaps, enabling present-day individuals to form a profound connection with the past, thereby shaping collective memory and fostering cultural preservation.

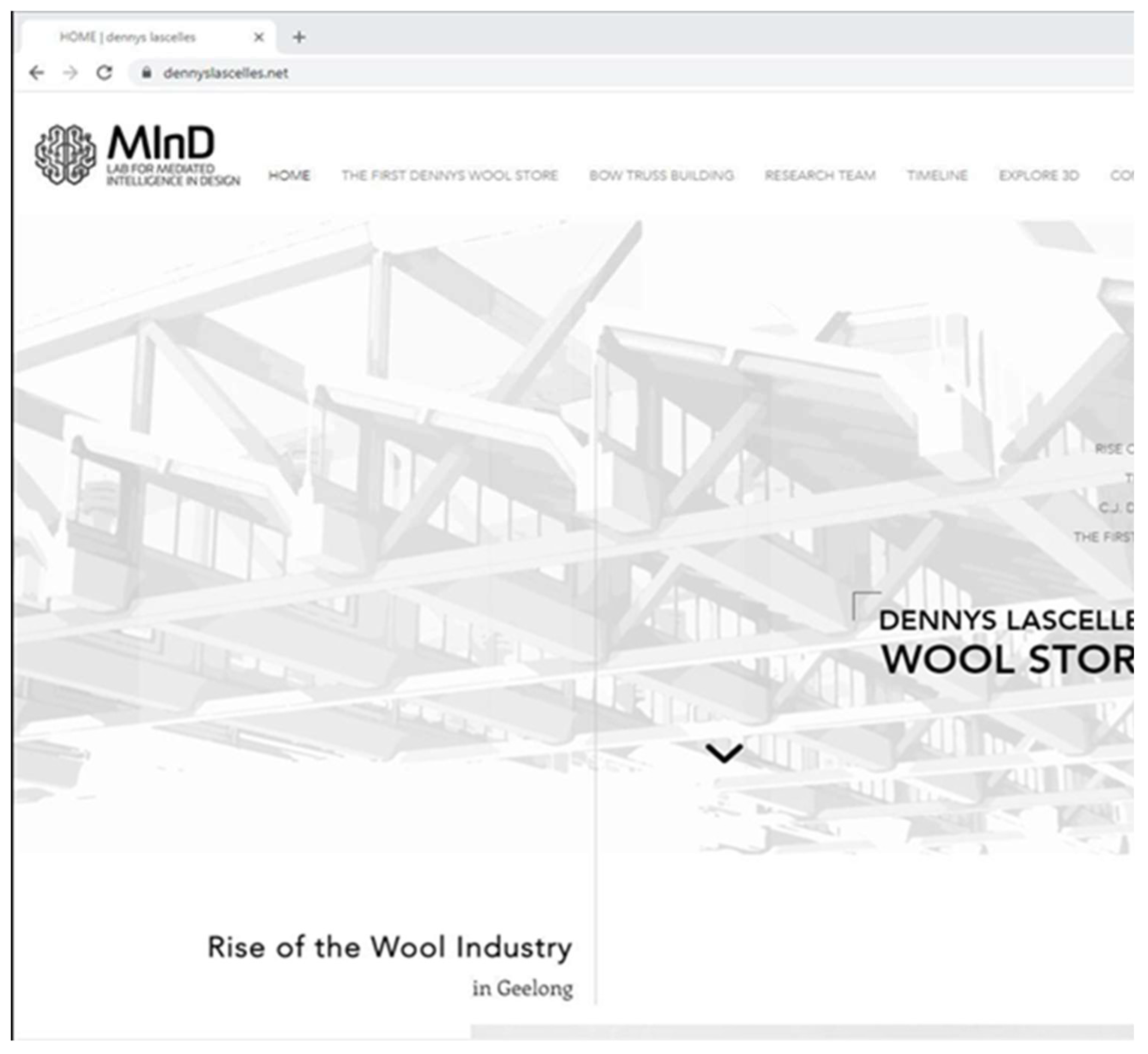

The study takes a critical stance by investigating the challenges surrounding the reconstruction of the lost architectural narrative of the Bow truss building, the primary structure within the Dennys Lascelles Wool Store complex. Despite the building’s heritage listing, it faced demolition, thereby disconnecting current citizens of the city of Geelong from its original architecture and historical significance as an initial study proposed a virtual diachronic model of the building, which views architecture as a dynamic process (Rashid and Antlej, 2020) and employs a linked open database to meticulously reconstruct the historical trajectory of the site. This approach effectively bridges the gap between the tangible and intangible aspects of heritage. The project is carried out through five distinct stages: data collection, identification of historical narratives, creation of a digital model, development of a user-friendly storyboard, and dissemination of findings via an interactive website (

Figure 2) (Rashid et al., 2021).

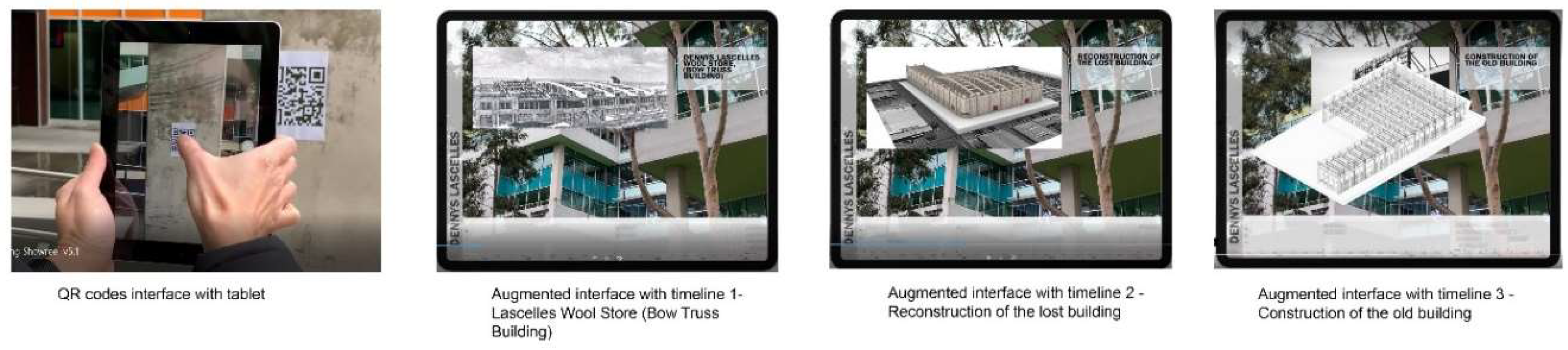

The first part of the study conclusively affirms the pivotal role that architecture and digital tools play in effectively preserving heritage while ensuring public engagement. The introduction of an Augmented Reality (AR) experiment utilising QR codes for virtual walking tours is particularly noteworthy (

Figure 3). The study's limited surveys yielded positive responses, which significantly underscore AR's potential for engaging users with historical spaces (Rashid et al., 2021). The project's ongoing innovation revolves around the intricately intertwined narratives, promoting an inclusive heritage experience that actively involves the community. As technology continues to advance rapidly, the study envisions a future where architectural interfaces play an instrumental role in disseminating heritage while promoting engagement with architecture.

The first part of the study conclusively affirms the pivotal role that architecture and digital tools play in effectively preserving heritage while ensuring public engagement. The introduction of an Augmented Reality (AR) experiment utilising QR codes for virtual walking tours is particularly noteworthy (

Figure 3). The study's limited surveys yielded positive responses, which significantly underscore AR's potential for engaging users with historical spaces (Rashid et al., 2021). The project's ongoing innovation revolves around the intricately intertwined narratives, promoting an inclusive heritage experience that actively involves the community. As technology continues to advance rapidly, the study envisions a future where architectural interfaces play an instrumental role in disseminating heritage while promoting engagement with architecture.

The ongoing reactivation project unveils a novel narrative, intricately weaving an inclusive heritage experience accessible through a user-friendly interface. This fusion of narratives offers an immersive journey that rekindles cultural memories via spatial and non-linear storytelling, thus infusing heritage with enduring 'Affect.' Concurrently, the project envisions repurposing buildings to align with circular economy principles. Amidst the rapid evolution of digital technology, the paper posits that the realm of 'affective heritage' holds the key to engaging with vanished structures and bygone eras. This approach stands not in contrast but rather in tandem with physical preservation endeavours, broadening the horizons of heritage conservation and dissemination, ensuring a sustainable circular future.

The team is also delving into more effective digital tools to capture the historic building like ‘Digital Twin’. Dezen-Kempter et al. (2020) has observed that the application of Digital Twins (DT) in Heritage involves creating intelligent 3D models (HBIM) that manage and enhance information accessibility. According to Nagakura and Woong-ki (2014), digital historical models aid building investigations cost-effectively, unlike physical artifacts stored in labs or museums. Technologies like photogrammetry and 3D laser scanning efficiently generate these models (Nagakura et al., 2015). Augmented Reality (AR) further aids interaction with these models, enhancing understanding and social engagement (Nagakura and Woong-ki, 2017). In future study anticipates exploring combining the Digital Twin with the Human-Building Interaction (HBI) through architectural interfaces and augmented digital content (Khoo et al., 2018), drawing parallels to prior instances such as the BIX façade and the tower of winds media façade. Foreseeing forthcoming technological strides and the evolving landscape of human-computer interaction (HCI), the study envisions historic building façades or interior walls as conduits for disseminating the building's historical essence, enriching user engagement sans the reliance on mobile devices and augmented technology. Khoo et al. (2018) research demonstrates the potential of integrating mobile spherical robots and projected digital visual contents as architectural interfaces for the existing built environment. In addition, as current artificial intelligence (AI) technologies continue to evolve, their integration into HBI and digital heritage preservation has given the opportunity to intelligent, adaptive, and responsive building interfaces that optimise human experience, history and culture in digital heritage (Luther et al., 2024). This development with AI also enables multi-modal HBIs, including voice, gesture, and touch-based controls that offer more intuitive and flexible ways for users to interact with the digital heritage superimposed on the physical built environment to enhance the user experience and knowledge (Murphy et al., 2023). The ever-evolving digital landscape with current AI technologies potentially ensures a multifaceted understanding of heritage, effectively guaranteeing its continuity within a sustainable and circular future. The project's findings and the anticipated future developments underscore the remarkable potential of affective heritage in reshaping heritage preservation and dissemination.

With the ever-changing digital world, we can better understand and keep heritage alive, ensuring it continues into the future. This project's discoveries and upcoming changes show that affective heritage, using digital tools, can play a big role in preserving and sharing heritage. In the end, this way of thinking suggests that affective heritage, using digital technology, could be a guide for protecting heritage in contemporary circular cities. This modern perspective combines technology, history, and how people connect to create a story where heritage not only survives but also thrives, adapting to the present while holding onto its cultural roots.

6. Conclusions

The fate of Geelong's Dennys Lascelles Wool Store exemplifies the delicate balance between heritage preservation and the circular economy's imperatives. Traditional preservation models fall short, unable to reconcile historical significance with adaptive reuse demands. Enter 'affective heritagization' with contemporary digital technologies: a paradigm that interweaves emotional connections with architectural legacy, fostering a more comprehensive understanding of heritage. This dynamic approach harmonises with the circular city concept, aligning heritage preservation with sustainable resource utilisation with advanced digital technologies.

Digital innovation emerges as a vital conduit, bridging heritage and contemporary experiences. By immersing individuals in virtual and augmented heritage journeys, these platforms restore buildings' stories, rekindling their essence within the community. Architectural interfaces with augmented experience and mobile technologies further amplify the engagement, ensuring heritage's resonance amid modernity. The introduction of current AI technological advancement will also further enhance the immersive experience of lost heritage that overcomes the shortcomings to address previous limitations and providing more accurate representations and narrative. This AI innovation will further offer deeper insights, richer storytelling, and more engaging user interactions, eventually bridging the gap between past and present with realistic representation and experience.

In sum, the Dennys Lascelles Wool Store's trajectory echoes the broader dialogue on heritage and sustainability. Affective heritage, fueled by digital augmentation, pioneers an inclusive path forward. This paradigm shifts not only safeguards lost heritage but also propels a circular city vision where the past and present harmoniously coexist, enriching our shared urban tapestry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MMR and CKK. MMR.; Literature Review, MMR, CKK and DM; investigation, MMR, CKK, and DM.; resources, MMR and CKK.; data curation, CKK.; writing—original draft preparation MMR, DM and CKK.; writing—review and editing, CKK.; visualization, CKK; supervision, MMR and CKK; project administration, MMR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data and contributions are presented and included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdelmonem, M. The Architecture of Home in Cairo: Socio-Spatial Practice of the Hawari's Everyday Life, ed. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmonem, M. Architectural and urban heritage in the digital age: Dilemmas of authenticity, originality and reproduction. International Journal of Architectural Research: ArchNet-IJAR 2017, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allom, L., Sanderson Pty. Ltd.Jacobs . Former Dennys Lascelles Woolstore : conservation management plan, ed., The Geelong Regional Commission. 1986.

- Apaydin, V. Heritage, memory and social justice: reclaiming space and identity, in V. Apaydin (ed.), Critical Perspectives on Cultural Memory and Heritage, UCL Press, UK, 2020, pp. 84–97.

- Arlotta, A.I. Locating heritage value in building material reuse. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 2020, 10, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrami, E., Macdonald, S.M., Randall and Myers, D. Values in heritage management : emerging approaches and research directions, Getty Publications virtual library, First edition. ed., The Getty Conservation Institute, 2019.

- Bullen, P.A. and Love, P.E.D. Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. Structural Survey 2011, 29, 411–421.

- Carman, J. Archaeology and Heritage : an Introduction, ed., Continuum International Pub. Group. 2003.

- Connerton, P. How societies remember, Themes in the social sciences, ed., Cambridge University Press. 1989.

- Dezen-Kempter, E.L.O.I.S.A. , Mezencio, D.L., Miranda, E.D.M., de Sãi, D.P., and Dias, U.L.I.S.S.E.S. Towards a digital twin for heritage interpretation, in D. Holzer, W. Nakapan and A. Globa (eds.),Re: Anthropocene, Design in the Age of Humans: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA 2020), pp. 183–191.

- Douglas, J. Building adaptation, Second edition. ed., Butterworth-Heinemann.2006.

- Fairclough, G. New heritage frontiers, in D. Thérond (ed.), Heritage and beyond, Council of Europe publishing. 2009.

- Fielding, A. Going Deeper than ‘Emotional Impact’: Heritage, Academic Collaboration and Affective Engagements, History. 2022, pp.107.

- Foster, G. Circular economy strategies for adaptive reuse of cultural heritage buildings to reduce environmental impacts, Resources. Conservation and Recycling 2020, 152, 1045–07. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, K. and Smith, L. Critical heritage studies and the legacies of the late-twentieth century heritage canon. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2019, 25, 1148–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Gravagnuolo, A. , Angrisano, M. and Fusco Girard, L. Circular Economy Strategies in Eight Historic Port Cities: Criteria and Indicators Towards a Circular City Assessment Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3512. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Heritage : critical approaches, ed., Routledge, 2013.

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography, ed., Edinburgh University Press, 2001.

- Herzfeld, M. Spatial cleansing: Monumental vacuity and the idea of the west. Journal of Material Culture 2006, 11, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS Australia . The Burra Charter: the Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance, Australia ICOMOS, Melbourne, Australia, 2013.

- Khoo, C. , Wang, R. and Globa, A. Prototyping a human-building interface with multiple mobile robots, Proceedings of the 23rd CAADRIA Conference, Beijing, China. 2018, pp.525-534.

- Kolesnik, A. and Rusanov, A. Heritage-As-Process and its Agency: Perspectives of (Critical) Heritage Studies, Higher School of Economics Research Working paper Series, 198, 2020.

- Lesh, J. Frozen in times, we’ve become blind to ways to build sustainability into our urban heritage, The conversation. 2022. Available online: https://theconversation.com/frozen-in-time-weve-become-blind-to-ways-to-build-sustainability-into-our-urban-heritage-187284 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- McCarthy, T.M.; Glekas, E.E. Deconstructing heritage: enabling a dynamic materials practice, Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 2020, 10, 16–28.

- Meskell, L. Global heritage: a reader, Blackwell Readers in Anthropology: 12, ed., Wiley Blackwell, 2015.

- Micieli-Voutsinas, J. and Person, A.M. Affective Architectures: More-Than-Representational Geographies of Heritage, 1st ed. ed., Routledge, 2020.

- Murphy, C. , Carew, P.; Stapleton, L. A human-centred systems manifesto for smart digital immersion in Industry 5.0: a case study of cultural heritage. AI & Society 2023, 39, 2401–2416. [Google Scholar]

- Nagakura, T., Tsai, D. and Pinochet, D. Digital Heritage Visualizations of the Impossible: Photogrammetric Models of Villa Foscari and Villa Pisani at Bagnolo, Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Cultural Heritage and New Technologies, Vienna. 2015.

- Nagakura, T. and Woong-ki, S. (2014) Ramalytique: Augmented Reality in Architectural Exhibitions, in M. d. S. Wien (ed.), Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Cultural Heritage and New Technologies, Vienna, pp. 1–20.

- Nagakura, T. and Woong-ki, S. AR Mail from Harbin, Proceedings of SIGGRAPH 2017: 44th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Los Angeles, California, United States of America, 2017.

- Ost, C. Revisiting Heritage Conservation in its Social and Economic Background, in Proceedings of LDE Heritage Conference on Heritage and the Sustainable Development Goals, edited by U. Pottgiesser, Fatoric, S., Hein, C., de Maaker, E., Roders, A.P., Delft, The Netherlands, 2021, pp.282–289.

- Prakash, V. and Scriver, P. Colonial modernities : building, dwelling and architecture in British India and Ceylon, The architext series, ed., Routledge, 2007.

- Rashid, M. , Khoo, C.K., Kaljevic, S.; Pancholi, S. Presence of the Past: Digital Narrative of the Dennys Lascelles Concrete Wool Store; Geelong, Australia. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.M.; Antlej, K. Geospatial platforms and immersive tools for social cohesion: the 4D narrative of architecture of Australia’s Afghan cameleers. Virtual Archaeology Review 2020, 11, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. and Duif, L. Small cities with big dreams : creative placemaking and branding strategies, ed., Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2019.

- Ross, S.; Angel, V. Heritage and waste: introduction. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 2020, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, D. and Jacobs, W. Former Dennys Lascelles Woolstore Heritage Assessment, 2017.

- Smith, L. Uses of heritage, 1st ed., Routledge, 2006.

- Smith, L. and Akagawa, N. Intangible heritage, 1st ed., Routledge., 2008.

- Smith, L.; Campbell, G. ‘Nostalgia for the future’: memory, nostalgia and the politics of class. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2017, 23, 612–627. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. and Waterton, E. Constrained by Commonsense: The Authorized Heritage Discourse in Contemporary Debates, The Oxford Handbook of Public Archaeology, 2012.

- Smith, N. New Globalism, New Urbanism: Gentrification as Global Urban Strategy. Antipode 2002, 34, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thouki, A. Heritagization of religious sites: in search of visitor agency and the dialectics underlying heritage planning assemblages. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2002, 28, 1036–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, C.D. Economics and culture, ed., Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Tippet, H. Heritage queries on peanut-shaped tower, Geelong Advertisor, Geelong, Victoria, Australia. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tolia-Kelly, D.P. , Waterton, E. and Watson, S. Heritage, Affect and Emotion : Politics, practices and infrastructures, in Critical Studies in Heritage, Emotion and Affect, ed., Taylor and Francis, 2016.

- Tunbridge, J.E. and Ashworth, G.J. Dissonant heritage : the management of the past as a resource in conflict, ed., Chichester, J. Wiley, New York, 1996.

- Zancheti, S.M. , Hidaka, L.T.F., Ribeiro, C.; Barbara, C. Judgement and validation in the burra charter process: introducing feedback in assessing the cultural significance of heritage sites. City and Time 2009, 4, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel, J. (2006) Inquiry by design: Environment/behavior/neuroscience in architecture, interiors, landscape, and planning, ed., W W Norton & Co, New York, NY, US.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).