1. Introduction

Bacterial infections constitute a significant public health challenge that necessitates the creation of novel and efficient therapeutic approaches [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Modern antibacterial drugs of the 3rd and 4th generation effectively destroy pathogenic bacteria

in vitro conditions. However,

in vivo conditions, they do not penetrate well into the localization sites of the pathogen, primarily into macrophages, where latent forms of pathogens, in particular

Mycobacteria,

Brucellae,

C. Рneumoniae are localized. The low efficiency of the drug delivery forces to take high doses of antibacterial drugs, sometimes for many months, causing significant side effects. The limited efficacy of current antimicrobial therapies stems from several key factors. Poor antibiotic penetration into sites of latent infection and the action of bacterial efflux pumps—proteins that actively remove drugs from cells—are major contributors to treatment failure [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Strategies to increase drug exposure at the site of infection, even at the same or lower dosages, and to enhance targeted drug delivery offer significant potential to improve both the effectiveness and safety of infectious disease treatments [

13].

While extensive research over the past decade has investigated drug-bacteria interactions, a comprehensive understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms remains elusive [

5,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. This study introduces a novel approach leveraging Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), a powerful nanoscale technique for probing molecular interactions, to provide unprecedented insights into the complex interplay between bacterial cells and drug molecules [

19,

20,

21,

22]. This approach overcomes limitations of previous studies by offering a quantitative, real-time assessment of these interactions.

Red fluorescent protein (RFP) is an intracellular fluorophore which is perspective for FRET-based studies due to the bright red fluorescence, minimizing background interference and enhancing signal specificity. This enhanced sensitivity could facilitate the precise study of protein-ligand interactions dynamic, intracellular signaling pathways and other specific cellular processes, providing valuable instrument for various imaging applications [

23,

24,

25,

26], where RFP is mainly used for visualizing protein-protein interactions [

27].

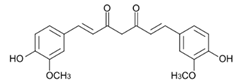

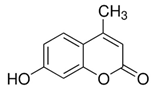

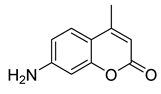

Here we applied the bacteria expressing RFP as the FRET acceptor, and the drug molecule acting as the FRET fluorophore-donor. This configuration allows for the detection of a highly specific signal that indicates the interaction of a drug’s fluorescent molecule with bacterial cells expressing the fluorescent protein. The presence of a FRET signal would directly visualize and demonstrate the proximity of the drug to the bacteria, signifying successful drug delivery a drug distribution. We employed FRET technique to monitoring the interactions of bioactive molecules such as curcumin, 4-methylumbelliferone (MUmb) or 7-Amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) with RFP bacterial cells containing. These compounds exhibit diverse modes of action. For instance, curcumin exhibits both anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties [

17,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Preliminary studies suggest that umbelliferones, including MUmb, AMC and its derivatives [

32,

33,

34,

35], may exhibit antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidative properties. These compounds may serve as adjuvants for antibiotics in the treatment of a variety of bacterial infections, or they can be employed independently to prevent infections.

Consequently, it is crucial to delve into the intricate mechanisms by which these bioactive substances exert their effects on cells. Indeed, the strategic use of adjuvants in conjunction with antibiotics offers a promising approach to combat antibiotic resistance. The key lies in effectively delivering antibiotics to the site of infection, while simultaneously inhibiting the activity of efflux pumps, one of the primary mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. This approach holds great promise in the fight against antibiotic resistance. We employ FRET pairs, where the RFP expression within bacteria is paired with either curcumin, AMC or MUmb serving as the FRET donors. This allows us to visualize the uptake and localization of drugs within the bacterial cells. The FRET pairs presented here enable the detection of a highly specific signal, corresponding to the interaction between the fluorescent drug molecule and bacterial cells that express the RFP.

However, non-optimal donor fluorophore biodistribution can limit this technique, resulting in insufficient FRET signal. Targeted delivery of the fluorescent probe into the bacterial cell is therefore crucial. Employing a smart delivery system, such as polymeric micelles [

18,

36,

37,

38,

39], is necessary to achieve effective intracellular probe localization and enhance FRET.

Polymeric micelles represent nanoscale entities that exhibit advantageous characteristics for drug delivery, including enhanced drug solubility and stability, prolonged circulation times, passive tumor targeting through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect [

40,

41,

42], and the potential for stimuli-responsive drug release. Targeted delivery of antibiotics via micelles offers the potential to reduce systemic toxicity and enhance therapeutic efficacy. Indeed, the inherent properties of polymeric micelles, such as their ability to penetrate biological barriers like cell membranes, biofilms, or specific organelle barrier make them ideal candidates for overcoming challenges posed by resistant infections [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

To enhance selectivity towards bacterial cells, permeability, and retention, we employed our recently developed smart formulations, that based on trigger-responsive polymeric micelles derived from chitosan or heparin conjugated with fatty acid moieties [

37,

44,

50,

51]. Heparin’s antithrombotic properties are advantageous in inflammatory diseases often accompanied by thrombosis [

52], whereas chitosan’s pH sensitivity [

37,

53,

54], stemming from amino group protonation in the slightly acidic microenvironment surrounding bacteria, offers targeted delivery potential.

This study aimed to develop a novel analytical approach based on the FRET technique for visualizing drug distribution dynamics, permeability into bacterial cells, and interaction with cellular components. Via FRET we investigated the delivery of antibacterial drugs such as curcumin, AMC or MUMb and the effect of smart polymer micellar systems on the drug internalization. The findings are significant for elucidating bacterial cell-drug interactions and devising innovative approaches to combat bacterial infections. Importantly, this FRET-based method holds substantial promise as a novel diagnostic tool for the detection and precise identification of bacterial pathogens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

Chitosan lactate (5 kDa, Chit5), oleic acid (OA), lipoic acid (LA), spermine (sp), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), and 4-methylumbelliferone (MUmb) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Curcumin and heparin (low-molecular-weight fractions, 12–14 kDa) were obtained from a commercial pharmacy with a certificate of quality. All other reagents, including salts, acids, and buffer components, were purchased from Reachim (Moscow, Russia).

2.2. Synthesis of Amphiphilic Polymers and Production of Polymeric Micelles

2.2.1. Synthesis of Grafted Conjugates of Heparin and Chitosan

Chit5-OA and Chit5-LA. 20 mg of oleic and lipoic acids were dissolved in 5 ml of a mixture of CH3CN/PBS (4:1, v/v, pH 7.4). 2.5 times the amount of EDC and 1.5 times the amount of NHS in DMSO were added to this mixture. The acid activation process was carried out for 20 minutes at a temperature of 30 °C. After that, pre-dissolved chitosan was added to the reaction mixture (50 mg in 10 mL of 1 mM HCl, followed by pH adjustment to 7). The mixture was incubated for 6 hours at 50 °C. The reaction products were purified using centrifuge filters (3 kDa, 10,000× g, 3 times for 10 minutes), and then dialysis was performed against water for 12 hours (with a cutoff of 6-8 kDa). The degree of chitosan modification was determined by spectrophotometric titration using 2,4,6-trinitrobenzoic sulfonic acid in a sodium-borate buffer (pH 9.2).

Hep-OA. 125 mg of heparin was dissolved in 10 ml of PBS. 2.5 times the amount of EDC and 1.3 times the amount of NHS relative to oleylamine in DMSO were added to the solution. This heparin activation process took place for 20 minutes at 30 °C. Then, pre-dissolved oleylamine (40 mg in 5 mL of CH3CN/PBS (4:1, v/v, pH 7.4)) was added and the mixture was incubated for 6 hours at a temperature of 50 °C. The reaction mixtures were purified using centrifuge filters (10 kDa, 10,000× g, 3 times 10 minutes) and then subjected to dialysis against water for 12 hours (with a cutoff of 12-14 kDa).

Hep-LA. To synthesize heparin conjugate with lipoic acid (Hep-LA), heparin modified with spermine (with a 20% grafting degree) was first obtained, and then the residues of the lipoic acid were gradually added to the amino groups of spermine, similar to the protocol described above.

All samples were lyophilized at a temperature of -60 °C (Edwards 5, BOC Edwards, Crawley, UK).

2.2.2. Production of Micelles

To obtain micelles, amphiphilic conjugates Chit5-LA, Chit5-OA, Hep-OA, and Hep-LA were dissolved in PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.4) at a concentration of 5 mg/ml. A preparation (MUmb or curcumin) in DMSO solvent (10 mg/mL) in a mass ratio of 0.1:1 - 10:1 (polymer/preparation) was added to these solutions. To form micelles and load the drug, the solutions were treated with ultrasound (at 50 °C, 10 minutes), and then extruded through a membrane with a pore size of 200 nm. To remove unrelated drugs, dialysis was performed for 6 hours against PBS (with a 3 kDa cutoff).

2.3. Polymer and Micelle Characterization

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to characterize the chemical structure of the synthesized polymers and micelles. Spectra were recorded using a MICRAN-3 FTIR microscope (Simex, Novosibirsk, Russia) and a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) equipped with a liquid-nitrogen-cooled mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector.

Further structural analysis was performed using ¹H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy at 500 MHz using a Bruker Avance DRX 500 spectrometer (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany). This provided detailed information on the proton environments within the polymer structures, confirming successful conjugation and grafting.

The degree of deacetylation in the chitosan (Chit5) was determined using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy on a Jasco J-815 CD spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). This analysis revealed a deacetylation degree of (92 ± 3)%.

The particle dimensions and surface charges were determined using the Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS system (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK), which employs a HeNe laser (5 mW, 633 nm) as the light source. The measurements were conducted in a temperature-controlled cell at 25 degrees Celsius. The fluctuations in the light scattering intensity were analyzed using the autocorrelation function, which was obtained with the Malvern Correlator K7032-09.

Morphological characterization of the polymeric micelles, including size and shape analysis, was performed using atomic force microscopy (AFM) with an NT-MDT NTEGRA II AFM microscope (NT-MDT Spectrum Instruments, Moscow, Russia). AFM imaging allowed for a direct visual comparison of the morphology of the grafted chitosan-based micelles to that of unmodified chitosan, providing insights into the effects of modification on micelle formation and structure. This visual confirmation complemented the data obtained from other techniques, providing a comprehensive characterization of the synthesized materials.

2.4. Fluorescence and Absorption Spectra of Bioactive Molecules in the UV/vis Range

UV/vis spectra of drug solutions (free form or micellar) in PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.4) were recorded on the AmerSham Biosciences UltraSpec 2100 pro device (Cambridge, UK). Fluorescence spectra of drug solutions (free form or micellar) in PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.4) were recorded using a Varian Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at 37 °C.

2.5. Microbiological Studies

2.5.1. Bacterial Culture and Preparation

Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) CGSC#12504 (F-, lon-11, Δ(ompT-nfrA)885, Δ(galM-ybhJ)884, λDE3 [lacI, lacUV5-T7 gene 1, ind1, sam7, nin5], Δ46, [mal+]K-12(λS), hsdS10) was used throughout this study. Overnight cultures (18–20 h, 37 °C, 120 rpm) were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (pH 7.2) to a cell density of approximately 4–7 × 10⁸ CFU/mL, as determined by both optical density (OD₆₀₀) measurement and plate counting.

2.5.2. Bacterial Transformation

Chemically competent

E. coli cells were transformed with the pRed plasmid, encoding red fluorescent protein (RFP) cloned into the pQE30 vector (Qiagen). The pRed plasmid was kindly provided by A.P. Savitsky (Institute of Biochemistry, Russian Academy of Science, Moscow, Russia). Transformation followed a standard protocol [

55].

2.5.3. Visualization of Petri Dishes with E. coli Expressing RFP and Interaction with Drugs Using the FRET Technique

RFP Expression Visualization

Following transformation and incubation (18 h at 37 °C, followed by a 2-day maturation period at 4 °C to enhance RFP fluorescence), E. coli colonies (10⁷ CFU/0.5 mL) were plated onto LB agar and imaged using a UVP BioSpectrum imaging system (UVP, Upland, CA, USA). Excitation and emission wavelengths were set at λex, max = 480 nm and λem = 485–655 nm, respectively. This provided a macroscopic visual confirmation of RFP expression.

Visualization of interactions of E. coli expressing RFP with drugsE. coli expressing RFP (10⁷ CFU/0.5 mL) were spread onto 20 mL agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 18 h, followed by 48 h at 4°C for RFP maturation. Six 9 mm wells per plate were loaded with 75 µL of 0.1 mg/mL MUmb, AMC, or curcumin (free or micellar formulations) and incubated for 12 h. Fluorescence images were acquired using a UVP BioSpectrum imaging system (UVP, Upland, CA, USA) to detect FRET from the drug to RFP (λex, max = 380 nm; λem = 485–655 nm).

2.5.4. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Fluorescence emission spectra of RFP-expressing E. coli suspensions (4 × 10⁸ CFU/mL) were acquired using a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrometer (Agilent Technologies). Excitation wavelength was fixed at λex = 520 nm. This provided quantitative data on RFP expression levels.

2.5.5. Interaction of Bioactive Molecules with E. coli

The interaction of bioactive molecules (MUmb, curcumin) with E. coli was investigated using both 96-well plates and sterile 2 mL Eppendorf tubes. All experiments were performed using a bacterial density of 5 × 10⁷ CFU/mL and a drug concentration of 0.1 mg/mL in a 50:50 (v/v) mixture of LB broth and PBS (pH 7.4, 0.01 M) at 37 °C. Real-time kinetic fluorescence measurements (λex = 520 nm; λem = 550, 580 nm) were performed using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices) with Costar black/clear-bottom 96-well plates. Measurements were taken at the initiation of the interaction and at subsequent time points over 1-2 days to monitor the interaction kinetics.

2.5.6. Assessment of Antibacterial Activity

The antibacterial activity of the bioactive compounds MUmb, AMC, and curcumin against E. coli was evaluated using a broth microdilution assay. An overnight E. coli culture (grown as described in section 2.5.1, yielding approximately 4-7 x 10⁸ CFU/mL) was diluted to a working concentration of 5 x 10⁶ CFU/mL. 200 µL of this diluted culture was added to each well of a 96-well plate. 50 µL of serially diluted bioactive compounds were then added to the wells, establishing a range of concentrations for analysis. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the optical density (OD₆₀₀) at various time points. To determine the inhibitory concentration (IC), the number of colony-forming units (CFU) was also determined using both OD₆₀₀ measurements and plate counts after appropriate dilutions, ensuring accuracy and consistency. The relationship between CFU and the concentration of each bioactive compound was modeled using a Boltzmann sigmoidal function (Origin software): CFU = (Control CFU) / (1 + exp(([X] – IC₅₀) / k)), where [X] represents the concentration of the bioactive compound, IC₅₀ represents the half-maximal inhibitory concentration, and k is a constant describing the steepness of the curve. The IC₅₀ and IC₉₀ values, representing the concentrations at which 50% and 90% inhibition of bacterial growth are observed, respectively, were then determined by fitting this equation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Article design

The design of this work encompasses several key aspects:

1. Synthesis of polymeric micelles based on Chit-OA, Chit-LA, Hep-OA, and Hep-LA micelles. Infrared (IR) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic data confirming their structure are presented. The size and morphological characteristics of the micelles, as measured by atomic force microscopy (AFM), are discussed.

2. Drug interaction with micelles: physico-chemical characterization of the interaction between curcumin, MUMb and AMC and micelles, including binding constants and stoichiometry. IR and NMR spectroscopic data confirm the successful integration of the drugs into the micelles, the size and morphology, as assessed by AFM

3. Visualization of the interaction of micelles with bacteria using AFM. Analysis of morphological changes.

4. FRET analysis of micellar drug interaction with bacteria expressing RFP. Demonstration of RFP (acceptor) fluorescence enhancement and quenching the fluorescence of drugs (donor). Quantification of the interaction.

5. Discussion of the advantages of the developed FRET technique and the prospects of using polymer micelles for the delivery of antibacterial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory drugs.

3.2. The synthesis and Spectral Analysis of Chitosan (Chit) and Heparin (Hep) Polymeric Micelles Functionalized with Oleic (OA) and Lipoic (LA) Acid Moieties

The polymers (chitosan and heparin) were functionalized with either oleic acid residues for enhanced solubility or lipoic acid residues to impart redox sensitivity to the micelles (

Figure 1a). The formation of these micelles occurred in two stages: grafting of polymers and subsequent formation of micellar systems using an extruder.

Firstly, amphiphilic polymers were synthesized, based on polycationic or polyanionic components and hydrophobic moieties. The synthesis of chitosan and heparin modified by fatty acid is illustrated in

Figure S1. The synthesis process is based on activating the carboxyl group of either lipoic or oleic acid, followed by forming a bond with the amine group of chitosan via carbodiimide approach, denoted as M1 and M2. For heparin, the process is reversed, with the carboxyl group from heparin interacting with the amino group from oleyl-amine following a similar mechanism, designated as M3. To create the conjugate of heparin and lipoic acid, Hep-LA (M4), it is necessary to introduce a spermine spacer to the polymer’s amino functionality. This method effectively allows for the attachment of hydrophobic residues to the polymer backbone, resulting in the formation of amphiphilic structures crucial for micelle formation.

The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy method was employed to validate the successful synthesis of amphiphilic polymers. The analysis of the acquired spectra unveiled critical modifications in the structure of the engineered biopolymers.

Figure 1b presents the FTIR spectra of chitosan (Chit5), oleic acid (OA), lipoic acid (LA), and their conjugated products (Chit5-LA and Chit5-OA). A reduction in the signal strength at 1710 cm⁻¹, attributed to oscillations in the carboxyl group of acids, is coupled with the emergence of absorption peaks at 1660 and 1560 cm⁻¹ corresponding to oscillations in the amide functional group (Amide I and II), indicating the formation of an acid-crosslinking amide bond in chitosan. Additionally, there is a decline in the intensity of a band in the 3600–3200 cm⁻¹ range linked to fluctuations in N-H bonds. A modification in the profile of C-O-C glycoside moieties in chitosan reveals the formation of micellar structures featuring hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions, accompanied by a transformation in the conformational state of polymer chains.

In the FTIR spectra of heparin and its derivatives with LA and OA (

Figure 1c), prominent bands are observed at 1250 cm⁻¹, corresponding to S=O oscillations in sulfate groups SO₃⁻), and in the frequency range between 1100 and 1000 cm⁻¹, representing C-O-C vibrations. Incorporating LA and OA into heparin results in the emergence of Amide I and Amide II bands, indicating the formation of C(=O)-NH amide bonds. FTIR spectra of conjugate exhibit signals for both initial components and newly introduced functional groups, generally confirming the successful modification of chitosan and heparin through the incorporation of fatty acids.

Table 1 presents the physico-chemical characteristics of amphiphilic conjugates based on chitosan and heparin modified with oleic acid or lipoic acid residues. It demonstrates the effect of the type of polymer and modifying fatty acid on the properties of the conjugates obtained and their ability to micelle formation. It can be seen that the degree of modification of chitosan (Chit5) by both lipoic (LA) and oleic (OA) acids is quite high (22-25%), which indicates the effectiveness of the inoculation reaction. The average molecular weight of one polymeric structural unit for both conjugates (M1 and M2) is 6.4-6.8 kDa. Positive values of the zeta potential (+12 - +15 mV) confirm the cationic character of the obtained chitosan-based micelles. The critical micelle formation concentration (CMC, determined using fluorescent pyrene probe) for Chit5-OA (M2) is lower than for Chit5-LA (M1) (0.16 µg/mL versus 0.31 µg/mL), which indicates easier micelle formation in the case of conjugate with oleic acid.

In the case of heparin Hep, the degree of modification by both OA and LA acids is lower (10-13%) than that of chitosan. This may be due to the peculiarities of the heparin structure and the lower availability of reaction centers. The average molecular weight of the structural unit for Hep-OA (M3) and Hep-LA (M4) conjugates is significantly higher (14 kDa), due to the higher molecular weight of the initial heparin. Negative values of the zeta potential (–7 - –10 mV) confirm the anionic character of heparin-based micelles. CMC for Hep-LA (M4) is higher than for Hep-OA (M3) (0.45 µg/mL versus 0.28 µg/mL), which indicates easier micelle formation in the case of heparin conjugate with oleic acid. Specifically, this is due to the more pronounced disparity between the hydrophobic and hydrophilic components of the micelles, which is attributed to the presence of the sulfo group.

In general, the data obtained indicates the successful synthesis of amphiphilic conjugates based on chitosan and heparin, capable of forming micelles under physiological conditions. Differences in CMC for different conjugates may be related to differences in the hydrophobic-hydrophilic balance of molecules and may affect the efficiency of drug loading and delivery.

3.3. Preparation and Characterization of Micellar Formulations of Bioactive Molecules and Adjuvants

The incorporation of bioactive molecules (curcumin, 4-methylumbelliferon (MUmb), and 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC)) into polymeric micelles based on chitosan and heparin modified with oleic or lipoic acid residues was carried out using ultrasound treatment followed by extrusion through a membrane with 200 nm pores. This method makes it possible to effectively encapsulate hydrophobic molecules in the core of micelles (

Table 2). The type of micelle significantly impacts the degree of drug incorporation for all three substances. Across all micelle types, MUmb exhibits the highest incorporation percentage, consistently exceeding 17% (expressed in mass percentages). This suggests a strong interaction between MUmb and all four micellar structures in hydrophobic core. Curcumin demonstrates lower incorporation degree, ranging from 3.5% (for Hep-LA) to 13% (for Chit5-OA). This variability implies that the interaction between curcumin and the micelles is highly dependent on the specific micellar structure. The solubilization of curcumin requires a long fatty acid residue to create more hydrophobic environment and it is possible to stabilize the chitosan-curcumin complex due to the formation of hydrogen bonds.

AMC shows moderate incorporation percentages, generally ranging between 13% and 21%, suggesting a relatively consistent interaction with the different micelles, although less pronounced than MUmb, due to the presence of an amino group in AMC and the possibility of repulsion from chitosan cationic chains, and vice versa by stabilization in heparin micelles. OA-containing micelles consistently show high incorporation for curcumin and MUmb, while LA-containing micelles shows low curcumin incorporation. Micelles with a charge opposite to that of the drug’s charged groups are necessary to maintain their stability. This underscores the significance of nature and makeup of polymeric micelles in determining the optimal level of drug loading.

The characterization of the inclusion of curcumin in micelles was carried out by FTIR and NMR spectroscopy.

Figure 2a shows the IR spectra of curcumin in free form and loaded into M1-M4 polymer micelles. The inclusion of curcumin in micelles is confirmed by changes in the characteristic absorption bands. There is a broadening and displacement of bands corresponding to v(C=C) oscillations in the composition of aromatic rings (1505 --> 1507-1510 cm-1; 1600 --> 1602-1603 cm-1), which indicates a change in its environment during encapsulation in the hydrophobic core of micelles. On the other hand, the intensity ratio of peaks I1625/I1505 = I(v(C=O))/I(v(C=C)) changes, which characterizes the change in the microenvironment of carbonyl groups of curcumin in the direction of increasing the degree of hydration due to interaction with polymer hydrophilic chains. This is further confirmed by a low-frequency shift in the oscillation band of the carbonyl groups of curcumin.

NMR spectroscopy provides data complementary to FTIR spectroscopy.

1H NMR spectra of Hep-OA micelles in D₂O (

Figure 2b) show heparin proton signals in the range of 3.0-4.5 ppm, as well as oleic acid proton signals in the range of 0.8-2.5 ppm. The presence of signals in the 5.3 ppm region corresponds to a proton with a double bond in oleic acid (low intensity).

1H NMR spectra of Hep-OA micelles loaded with curcumin (

Figure 2c), in addition to Hep-OA signals, contain signals of curcumin protons. Characteristic signals of aromatic protons of curcumin are observed in the region of 6.4; 6.8-7.0 and 7.3-7.5 ppm, and the signals of the methoxy groups are about 3.8 ppm. The appearance of these signals clearly confirms the successful encapsulation of curcumin. The low intensity of curcumin signals is associated with the limited solubility of curcumin in micelles (up to 0.5 mg/ml) and the NMR spectroscopy requirements for sample concentration (about 10 mg/ml). The observed broadening of the signals of curcumin protons may be due to the limitation of their mobility within the micellar structure.

Thus, the effective encapsulation of aromatic medicinal biomolecules (using curcumin as an example) into polymer micelles is shown.

3.4. Visualization of the Polymeric Micelles and Its Interaction with E. coli Using AFM

Figure 3ab shows atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of empty Hep-OA micelles (a) and Hep-OA micelles loaded with curcumin (b). AFM makes it possible to visualize the morphology of micelles, determine their size, and evaluate sample homogeneity. The images of empty Hep-OA micelles (

Figure 3a) show formations that are far from spherical in shape, with a wide size distribution from 100 to 800 nm. This may indicate the aggregation of micelles and the absence of a well-defined structure in the absence of a loaded substance. The inclusion of curcumin leads to a significant change in the morphology of micelles (

Figure 3b). Characterization of the curcumin-loaded Hep-OA micelles revealed a uniform population of spherical particles with a size distribution ranging from 65 to 120 nm. Importantly, no significant aggregation was detected, indicating a high degree of micellar stability and homogeneity. This uniform size and lack of aggregation are crucial factors for ensuring consistent drug delivery and predictable biological interactions.

This change in morphology and decrease in particle size when loaded with curcumin can be explained by the factor that curcumin, being a hydrophobic molecule, is localized in the core of micelles, stabilizing their structure and contributing to the formation of more compact spherical formations. Thus, curcumin plays an important role not only as an encapsulated substance, but also as a structure-forming agent that affects the morphology and size of Hep-OA micelles. Reducing the size and increasing the homogeneity of micelles when loaded with curcumin is an important for increasing the efficiency of drug delivery, as it improves their pharmacokinetic properties and bioavailability.

To visualize the micelles interaction with

E. coli, atomic force microscopy (AFM) was employed.

Figure 3c-f provides visual evidence of the interaction of

E. coli bacterial cells with the polymeric micelles under study, obtained using atomic force microscopy (AFM).

Figure 3c shows an AFM magnified image of a single

E. coli cell after pre-incubation with curcumin-loaded Hep-OA micelles. The image shows the adsorption of micelles on the surface of a bacterial cell. This indicates the interaction of micelles with the bacterial cell wall, which is important for the subsequent penetration of curcumin into the cell.

Figure 3d-f demonstrate the interaction of several

E. coli cells in a large field with empty Chit-LA micelles. In

Figure 3d, spherical micelle particles are visible when focused on the mica. This confirms that Chit-LA micelles retain their morphology and are not destroyed by interaction with bacteria.

Figure 3e (height signal) and 3f (magnitude signal) provide additional information about the topography and mechanical properties of the sample. Micelles are partially visible on the surface of bacterial cells. Based on the analysis of the available data, chitosan presented in the form of Chit-LA micelles exhibits remarkable properties in its interaction with

E. coli cells. Upon contact with bacteria, chitosan maintains its morphological integrity, indicating its durability and potential as a delivery agent for pharmaceuticals. While heparin also exhibits a strong interaction with cells, the adhesion of chitosan is more stable due to electrostatic forces. Consequently, it can be inferred that chitosan may prove to be a more advantageous option in this context, albeit heparin possesses its own unique advantages.

In general, the AFM data indicate the interaction of the studied polymer micelles with E. coli bacterial cells. Visualization of this interaction is an important step for understanding the mechanisms of drug delivery using micelles and optimizing their composition to increase the effectiveness of therapy.

3.5. Fluorescence Studies of Drug Encapsulation in Polymeric Micelles

Curcumin, MUmb, and AMC were selected as model bioactive molecules and suitable fluorescence donors for RFP-based FRET studies.

Figure 4a shows the fluorescence emission spectra of curcumin, MUmb, and AMC both in free form and encapsulated within Chit5-OA micelles, alongside the emission spectrum of the RFP acceptor in

E. coli cells. The data reveals that encapsulation into the micelles minimally alters the spectral profiles of MUmb and AMC, primarily resulting in a reduction of fluorescence intensity. However, Chit5-OA micelles significantly alter the curcumin emission spectrum, leading to a substantial increase in spectral overlap between the curcumin (donor) emission and the RFP (acceptor) excitation (

Figure 4a). This enhanced spectral overlap suggests a significant improvement in the efficiency of FRET when curcumin is delivered via Chit5-OA micelles.

Figure 4b-e illustrate the fluorescence spectra of curcumin in its free form and within various micellar formulations. In Chit5-LA micelles (

Figure 4b), an increased fluorescence intensity at 535-540 nm is observed with minimal spectral profile alteration, indicating enhanced solubility and a minor change in the curcumin’s microenvironment. In Chit5-OA micelles (

Figure 4c), a dramatic spectral shift occurs: a new peak emerges at 485 nm (compared to the 535 nm peak in free curcumin), representing a significant change in the spectral profile. This profound alteration highlights curcumin’s high sensitivity to the hydrophobic microenvironment of micelle core. This sensitivity, coupled with the fact that the critical micelle concentration (CMC) is approximately 25-50 µg/mL, makes polymeric micelles a promising delivery system for curcumin in analytical approaches involving cells and proteins, enabling studies of release kinetics and other related parameters. Curcumin inclusion into OA-containing micelles (Chit5-OA and Hep-OA,

Figure 4c and 4d) indicates a sharp change in the curcumin microenvironment and its transition to the hydrophobic core of micelles, which is consistent with previously published data on the dependence of the spectral characteristics of curcumin on the solvent [

56]. An increase in the fluorescence intensity also indicates to an increase in the solubility of curcumin (up to 0.15 mg/mL) in the presence of micelles. As shown above, the loading of curcumin into Chit-OA and Hep-OA micelles was maximal. The dissociation constants of curcumin complexes with micelles Chit5-OA and Hep-OA are estimated as 10 and 3 µM, correspondingly.

Curcumin’s fluorescence spectra show less pronounced changes in case of LA-containing micelles (Figures 4b and 4e). While a slight fluorescence intensity increase is observed, the emission maximum shift is less significant than in oleic acid micelles. This suggests curcumin solubilization (up to 0.1 mg/mL) within these micelles, but with less alteration of its microenvironment. The shorter length and terminal thiol group of lipoic acid, imparting less hydrophobicity compared to oleic acid, likely leads to curcumin occupying not only the hydrophobic core but also more hydrophilic regions of the lipoic acid micelles. This is supported by estimated dissociation constants of ~20 and 8 µM for curcumin complexes with Chit5-LA and Hep-LA micelles, correspondingly.

The discussion initially focused on curcumin due to its inherent interest as a bioactive molecule and its complex behavior within the micellar systems. However, to validate the observed effects and investigate the generality of FRET efficiency modulation by micelles, the study expanded to include MUmb and AMC. These compounds were chosen as they offer superior fluorescence quantum yields compared to curcumin, representing more established fluorophores for FRET applications. Furthermore, AMC, possessing additional anti-inflammatory properties, presents a promising candidate for drug delivery. The inclusion of MUmb and AMC allows for a comparative analysis of FRET efficiency across different fluorophores, ensuring robustness of the findings and expanding the potential therapeutic applications of this micellar drug delivery system.

Figure 5 illustrates the interaction of 4-methylumbelliferone (MUmb) with the polymeric micelles studied. The fluorescence spectra of MUmb in free form and in the Chit5-LA and Hep-OA micellar systems (Figs. 5a and 5b) demonstrate changes in fluorescence intensity upon addition of polymers. When the fluorophore is incorporated into the micelles, fluorescence quenching is observed; in the case of OA-containing polymers, a stronger quenching is observed than in the case of LA. The sigmoidal curves character of the dependence of the intensity of MUmb fluorescence on the polymer concentration (

Figure 5c) is typical for binding processes. The linearization of these curves in Hill coordinates (

Figure 5d,

Table 3) allowed us to determine the physico-chemical parameters of the interaction of MUmb with micelles, including the apparent dissociation constant (

Kd), the binding constant (

KA) and the Hill coefficient (n).

KA is the concentration of the ligand at which half saturation is achieved, and the Hill coefficient (n) characterizes the cooperativeness of binding.

The obtained values of –lg Kd show that MUmb interacts more efficiently with heparin-based micelles (Hep-OA and Hep-LA) than with chitosan- micelles (Chit-LA and Chit-OA) by about an order of magnitude in terms of constants. The Hill coefficient (n) for all systems is close to 1, which implies the absence of cooperativity in the binding of MUmb to micelles and the stoichiometry of 1 amphiphilic polymer to 1 MUmb molecule. A slight excess of the n value for Hep-OA and Hep-LA (1.20 and 1.35, respectively) may indicate some positive cooperativeness. High R-square values (close to 1) for all linearizations confirm the adequacy of the Hill model for describing the interaction of MUmb with the micelles.

The fluorescence data indicate the effective incorporation of MUmb into the polymer micelles, but unlike curcumin, we observe fluorescence quenching (due to the incorporation of MUmb in the micellar core) as opposed to ignition (due to the solubilization of curcumin). This opens up prospects for using these systems as carriers for the delivery of MUmb, curcumin and other hydrophobic drugs.

3.6. FRET Technique for Monitoring the Interaction of Fluorophores with Bacterial Cells Express RFP

3.6.1. Visualization of the Interaction of Cells with Drugs

The proposed FRET based technique to investigate the interaction between fluorophores and bacterial cells expressing red fluorescent protein (RFP) represents a powerful approach for evaluating the permeability of biologically active molecules into the cells. The experimental design depicted in

Figure 6a involves incubating RFP - bacterial cells with fluorophores or the micelles form, followed by the acquisition of fluorescence spectra compared to cells without incubation with fluorophore. The efficacy of FRET is determined by the activation of RFP fluorescence, which is influenced by the permeability of the bioactive molecules within the cell membrane and their level of interaction with RFP.

The Petri dish experiment, employing bacteria expressing RFP, provided a visual (fluorescence detection) platform to assess the permeability of AMC, MUmb, and curcumin – both free and encapsulated within micelles (

Figure 6b-d;

Table 4). The RFP-expressing bacteria served as a dynamic backdrop, highlighting the diffusion of fluorescent compounds.

Table 4 presents RFP fluorescence intensity measurements from a Petri dish assay using

E. coli expressing RFP to assess the cellular permeability of drugs. The data show variable effects of the different formulations on RFP fluorescence intensity (as quantitative values of FRET).

Curcumin, despite its known bioactivity, exhibited low fluorescence signal, due to its inherently low quantum yield. The weakly expressed fluorescent halo around the curcumin-containing wells (

Figure 6d) suggests poor membrane permeability in its free form, highlighting a necessitates a delivery system for its therapeutic application.

In contrast, both MUmb (

Figure 6c) and AMC (

Figure 6d) demonstrated a clear fluorescent halo, indicating successful penetration into the surrounding bacterial medium. This suggests that these compounds, at least in their free forms, possess greater intrinsic membrane permeability than curcumin. Crucially, the experiment also revealed a striking dependence on the micelle type: MUmb achieved maximal penetration when delivered via chitosan micelles (the diameter of the diffusion is about 30 mm vs 25 mm for other formulations), while AMC showed superior performance with heparin micelles (the diameter of the diffusion is about 25 mm vs 20-21 mm for other formulations).

This differential response to micelle type strongly implies that the choice of carrier system is paramount for optimizing drug delivery. The specific chemical interactions between the micelle material and the bacterial membrane appear to play a crucial role, and these results highlight the potential for targeted drug delivery approaches by selecting micelles with enhanced compatibility with specific cell types. This simple Petri dish assay thus offers a powerful visual and quantitative method for assessing the efficacy of different drug delivery strategies.

3.6.2. Spectral Analysis of the Interaction of Cells with Drugs

The analysis of the fluorescent spectra in

Figure 7 provides more detailed information on the interaction between drugs and cells in a more formal context. In this segment, we could determine how various conditions and the composition of micelles impact the fluorescent properties of the drugs under investigation.

The increase in the fluorescence intensity of RFP fluorescence by approximately 40% upon the addition of free curcumin suggests its penetration into the cells and interaction with RFP (

Figure 7a). However, the employment of micellar formulations markedly enhances this effect. There is a significant difference in the efficacy of FRET for various types of micelles, namely Chit5-LA, Chit5-OA, Hep-OA, and Hep-LA. This variation indicates the influence of both the polymer type and the modifying fatty acid on the permeability. Micelles based on chitosan with oleic acid, Chit5-OA, exhibit a remarkable enhancement of RFP (115%). This suggests a superior ability of these micelles to penetrate bacterial cells owing to their effective solubilization of curcumin. Curcumin in Hep-LA micelles exhibit a remarkable degree of RFP enhancement, approximately 700 %. This can be due to the electrostatic interactions between heparin and the positively charged RFP. Besides, the heparin facilitates the process of drug penetration into the cell. Chit5-LA and Hep-OA demonstrate an intermediate level of efficiency, with 50 % and 75 % RFP activation, respectively.

Micellar curcumin’s intracellular fate involves: 1) membrane binding; 2) endocytosis (type depends on micelle properties); 3) curcumin release (mechanisms include lysosomal acidification or enzymatic degradation); and 4) intracellular distribution (including potential mitochondrial targeting due to curcumin’s hydrophobicity).

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) allowed us to investigate the penetration of drugs into bacterial cells and the kinetics of fluorescence penetration, contingent upon the presence and composition of micelles.

Figure 7b presents the data on the FRET dynamics of MUmb over a period of two hours and 48 hours, revealing an increase in FRET efficacy over time, indicative of a gradual accumulation of fluorescent molecules within cells.

After two hours of incubation, micelle penetration remained relatively slow, reaching a maximum of approximately 15%. This limited penetration may be attributed to the prolonged interaction of MUmb-loaded micelles with cellular structures and their slower diffusion rates compared to free MUmb. Furthermore, the encapsulation of MUmb within the micellar matrix may limit its immediate bioavailability. A control experiment using free MUmb clarified the contribution of micellar encapsulation to the observed slower penetration rate.

Following 48 hours of incubation, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) is predominantly driven by fluorophores that have successfully internalized in the cells. For most micelle types, the FRET efficiency reaches a plateau at approximately 0.3, significantly surpassing the performance of non-micellar MUmb, which exhibits an efficiency of 0.1 and practically fails to penetrate bacterial cells and the drug interacts poorly with RFP without micelles. This observation underscores the efficacy of micellar drug delivery in enhancing the intracellular distribution of therapeutic agents.

In summary, we are indeed observing FRET, particularly for curcumin (as shown in

Figure 7a). In micelles, the intensity of FRET is enhanced, possibly due to the concentration enhancement effect. In solution, we could not detect FRET, as we noted in our earlier article [

57]; it is only observable in cells and micellar systems. Our results highlight that the type of polymer used (either chitosan or heparin) and the modifying fatty acid (such as oleic or lipoic) significantly influence the permeability of these micellar formations into bacterial cells. Micelles containing lipoic acid residues result in an average higher FRET efficiency compared to OA-containing micelles. This is due to the smaller size of the former and the greater hydrophilicity, which is important for interaction with RFP. Heparin-based micelles exhibit the best permeability, which makes them promising for drug delivery into bacterial cells. The high efficiency of Chit5-OA also deserves attention. Therefore, both types of these micelles can be used to deliver other hydrophobic drugs, including anticancer drugs, antibiotics, and antiviral agents.

3.7. Antibacterial Activity of Curcumin, MUmb, and AMC in Free Form and in Micelles as Independent Substances and Adjuvants for Antibiotics

The employment of polymeric micelles as nano-carriers for the transportation of curcumin, MUMb, and AMC presents promising avenues in the battle against infections. These compounds are known for their anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties; however, their limited solubility in aqueous solutions and rapid metabolic degradation pose constraints on their clinical application. The micellar delivery system addresses significant challenges by enhancing solubility, increasing bioavailability, and facilitating the controlled release of active components. Regarding the inhibition of efflux proteins, we are developing a formulation that simultaneously incorporates an antibiotic agent and an adjuvant to suppress the activity of efflux pumps, which are one of the primary mechanisms of multidrug resistance. This approach aims to improve the efficacy of antibiotic treatments by overcoming one of the key barriers to their effectiveness.

So, the antimicrobial activity of curcumin, MUmb and AMC were assessed both in their free form and incorporated into various micellar systems, including Chit5-LA, Chit5-OA, Hep-OA, and Hep-LA. Additionally, their combined effects with moxifloxacin were explored. The findings are presented in

Table 5, which illustrates the percentage of viable cells following treatment with the samples at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL.

A comprehensive analysis of the data presented in

Table 5 reveals that all three substances exhibit antimicrobial activity with comparable efficacy values. Notably, the encapsulation within micelles significantly influences their potency. For instance, curcumin demonstrates the highest activity in Hep-OA (M3), owing to the enhanced solubility and cellular penetration of these particles. Conversely, MUMb exhibits the most pronounced effect in Chit5-OA (M2), which is attributed to its solubilization through OA residues. These findings underscore the critical importance of selecting the appropriate micelle type for the successful delivery and controlled release of each compound.

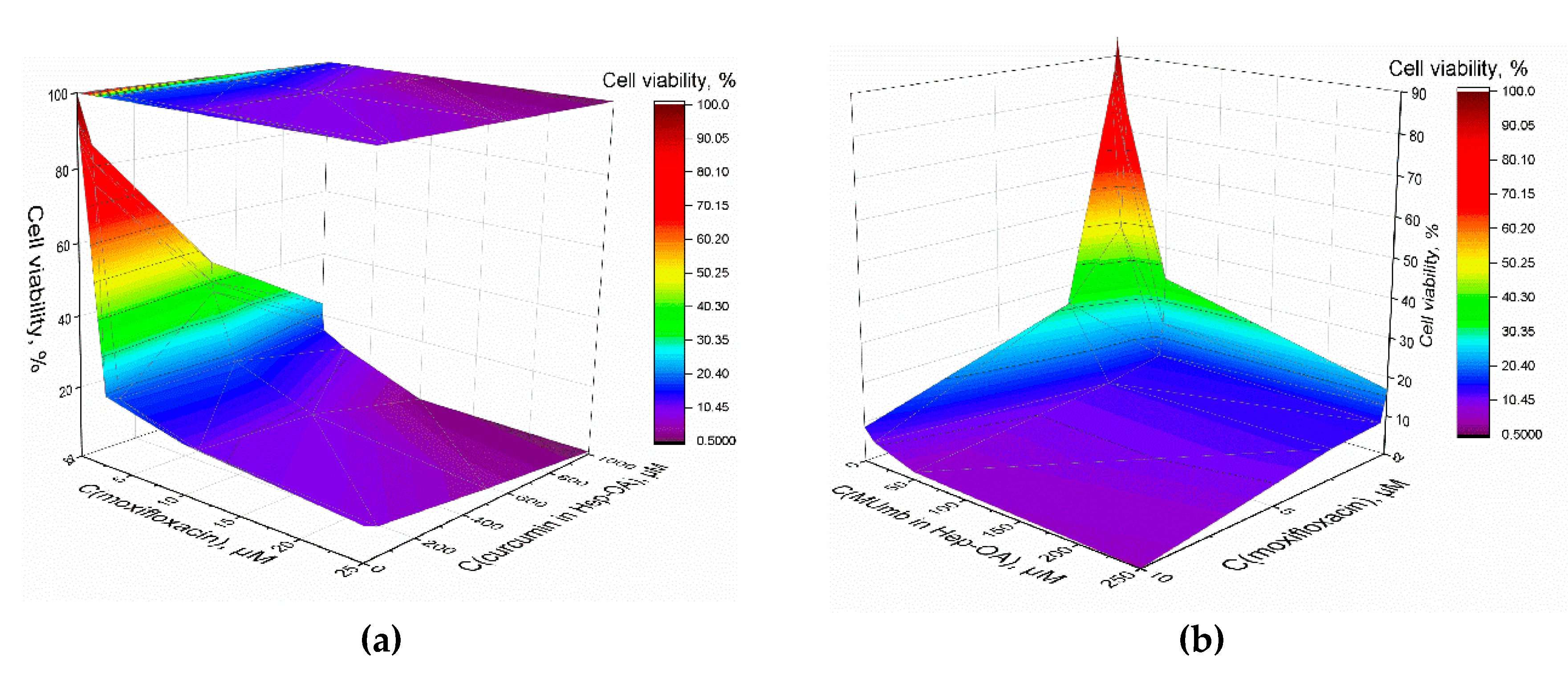

Furthermore, we explored the synergistic impact of the combined application of curcumin, MUmb, and moxifloxacin, as depicted in 3D diagrams (

Figure 8ab), that show the dependence of bacterial cell viability on the concentrations of moxifloxacin and each of the adjuvants. The most important feature is a significant increase in the antibacterial effect of moxifloxacin at low concentrations (up to 5 µM – pharmacological relevant values) in the presence of curcumin and MUmb. This enhancement reaches an impressive 40-50%, which indicates the high effectiveness of combination therapy. At low concentrations of moxifloxacin its intrinsic antibacterial activity is limited. However, the addition of curcumin or MUmb significantly increases the effectiveness of moxifloxacin, leading to a significant decrease in bacterial cell viability. This means that curcumin and Mumb don’t just add their effects to moxifloxacin. They act together and make antibacterial effect better.

This enhanced antibacterial efficacy may be attributed to several mechanisms:

1. Inhibition of efflux pumps. Both curcumin [

11,

58], umbelliferones [

59] and coumarins [

60] have the ability to inhibit bacterial efflux pumps. These pumps are responsible for expelling antibiotics from bacterial cells, thereby reducing their effectiveness. By blocking these pumps, moxifloxacin can exert its action more effectively.

2. Increased membrane permeability. The use of micellar formulations, particularly those incorporating oleic acid, presumably, enhances the permeability of bacterial membranes. Micellar effect was shown by us earlier in the work [

51].

3. Modification of microbial environment. The presence of micelles alters the microenvironment within bacterial cells, potentially amplifying the effects of moxifloxacin.

The synergistic interaction between curcumin and moxifloxacin represents a valuable finding. By enhancing the efficacy of existing antibiotics through combined therapy, we can mitigate the risk of antibiotic resistance and broaden the range of available treatments for infections resistant to conventional approaches. This is particularly significant in the context of the worldwide problem of antibiotic resistance. These data contribute to advancements in personalized medicine, enabling the selection of optimal drug combinations and delivery systems that maximize therapeutic outcomes while minimizing adverse reactions.

4. Conclusions

FRET-based platform allows quantitative evaluation of intracellular delivery of bioactive compounds (AMC, MUmb, and curcumin) into bacterial cells using polymeric micelles, leveraging the inherent properties of RFP expressed in E. coli. Typically, assessment of intracellular delivery could include a fluorophore, loaded in delivery vehicle, with subsequent analysis using confocal microscopy, or other relevant method. However, fluorescence can be quenched by non-specific interaction with intracellular proteins, or the fluorophore can absorb on the cell surface instead of intracellular de-livery, which is very difficult to distinguish by spectroscopic methods. The use of test compound (or drug) as FRET donor, and RFP as acceptor, allows for direct visualization via FRET effect only when the interaction takes place inside the cell, making it a much more specific approach.

The FRET effect was robust throughout three different donor compounds and dif-ferent compositions of the polymeric micelle, enabling the possibility to select the most efficient vehicle. This assay visually demonstrated superior cell membrane permeability for polymeric formulations of AMC and MUmb, and poorly for curcumin. Specifically, a 18-30% increase in fluorescence AMC intensity was observed for curcumin delivered via Hep-OA and Hep-LA micelles compared to free drug, indicating the enhanced FRET efficiency. The optimal micelle type varied depending on the drug: MUmb showed maximal penetration with chitosan micelles, while AMC exhibited the highest penetration with heparin micelles. The molecular explanation for that difference is unclear, but the result emphasizes the importance of carrier selection in optimizing delivery.

Interestingly, we have observed FRET effect inside the E.coli cells at concentrations, which are normally not sufficient to yield such effect in-situ, indicating that cell mem-brane may play an important role in facilitating the spatial proximity of the donor organic molecules with the RFP fluorescence acceptor epitope. AFM imaging confirmed micelle-bacteria interactions at the nanoscale, revealing nanoscale observations: uniform micelle distribution on the bacterial surface, a specific number (30-50) of micelles bound per bacterium cell.

Furthermore, micellar formulations exhibited enhanced antibacterial activity compared to free drugs, with Hep-OA micelles demonstrating the most significant reduction in E. coli viability. Synergistic effects were observed when combining curcumin and MUmb with moxifloxacin, resulting in a remarkable 40-50% increase in efficacy, particularly at low (≤5 µM) moxifloxacin concentrations. This synergistic effect suggests that curcumin and MUmb not only contribute additively but also potentiate moxifloxacin action, potentially allowing for a 2-3 -fold reduction in moxifloxacin concentration to achieve the same antibacterial effect.

In conclusion, this novel approach—combining the sensitivity and precision of FRET with the simplicity of a Petri dish assay for real-time visualization, and incorporating antibacterial activity assessments—provides a robust platform for optimizing micelle-based drug delivery systems and evaluating antimicrobial efficacy. The significant advance lies in the direct visualization and quantitative measurement of intra-cellular drug delivery, providing critical mechanistic insights into micellar interactions with bacteria at the nanoscale, which is not achievable with traditional methods. This method holds considerable promise for advancing targeted therapies against bacterial infections.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1. The schemes of synthesis of amphiphilic polymers: Chit5-LA, Chit5-OA, Hep-OA and Hep-LA.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.V.K. and I.D.Z.; methodology, I.D.Z., N.G.B. and E.V.K.; formal analysis, I.D.Z.; investigation, I.D.Z., N.G.B. and E.V.K.; data curation, I.D.Z., N.G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, I.D.Z.; writing—review and editing, E.V.K.; project supervision, E.V.K.; funding acquisition, E.V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Funds of the State Assignments of the M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, 121041500039-8.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The work was performed using the equipment FTIR microscope MICRAN-3 (Simex, Novosibirsk, Russia), FTIR spectrometer Bruker Tensor 27 (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany), Jasco J-815 CD Spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan), AFM microscope NTEGRA II (NT-MDT Spectrum Instruments, Moscow, Russia) of the program of Moscow State University development.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Deusenbery, C.; Wang, Y.; Shukla, A. Recent Innovations in Bacterial Infection Detection and Treatment. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 695–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Biondo, C. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance: The Most Critical Pathogens. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacGowan, A.; Macnaughton, E. Antibiotic Resistance. Med. (United Kingdom) 2017, 45, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigangirova, N.A.; Lubeneс, N.L.; Zaitsev, A. V.; Pushkar, D.Y. Antibacterial Agents Reducing the Risk of Resistance Development. Klin. Mikrobiol. i Antimikrobn. Himioter. 2021, 23, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Lu, W.; Qin, X.; Liang, S.; Niu, C.; Guo, J.; Xu, Y. Hydrogen Sulfide-Sensitive Chitosan-SS-Levofloxacin Micelles with a High Drug Content: Facile Synthesis and Targeted Salmonella Infection Therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalhoff, A. Global Fluoroquinolone Resistance Epidemiology and Implictions for Clinical Use. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellewell, L.; Bhakta, S. Chalcones, Stilbenes and Ketones Have Anti-Infective Properties via Inhibition of Bacterial Drug-Efflux and Consequential Synergism with Antimicrobial Agents. Access Microbiol. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyfakh, A.A.; Bidnenko, V.E. ; Lan Bo Chen Efflux-Mediated Multidrug Resistance in Bacillus Subtilis: Similarities and Dissimilarities with the Mammalian System. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991, 88, 4781–4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, B. Bacterial Efflux Systems and Efflux Pumps Inhibitors. Biochimie 2005, 87, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bambeke, F.; Balzi, E.; Tulkens, P.M. Antibiotic Efflux Pumps. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000, 60, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshra, K.A.; Shalaby, M.M. Efflux Pump Inhibition Effect of Curcumin and Phenylalanine Arginyl β- Naphthylamide (PAβN) against Multidrug Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolated from Burn Infections in Tanta University Hospitals. Egypt. J. Med. Microbiol. 2017, 26, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.; Uniyal, A.; Tiwari, V. A Comprehensive Review on Pharmacology of Efflux Pumps and Their Inhibitors in Antibiotic Resistance. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 903, 174151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosanchuk, J.D.; Lin, J.; Hunter, R.P.; Aminov, R.I. Low-Dose Antibiotics: Current Status and Outlook for the Future. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, J.D.; Kleinekathöfer, U.; Winterhalter, M. How to Enter a Bacterium: Bacterial Porins and the Permeation of Antibiotics. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 5158–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, B.; Christophersen, L.; Thomsen, K.; Sønderholm, M.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Høiby, N.; Moser, C. Antibiotic Penetration and Bacterial Killing in a Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm Model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 2057–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Li, C.; Jia, Y. Bioconjugated Nanoparticles for Attachment and Penetration into Pathogenic Bacteria. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 10328–10337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.H.N.; Hiebner, D.W.; Fulaz, S.; Vitale, S.; Quinn, L.; Casey, E. Synthesis and Self-Assembly of Curcumin-Modified Amphiphilic Polymeric Micelles with Antibacterial Activity. J. Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripodo, G.; Perteghella, S.; Grisoli, P.; Trapani, A.; Torre, M.L.; Mandracchia, D. Drug Delivery of Rifampicin by Natural Micelles Based on Inulin: Physicochemical Properties, Antibacterial Activity and Human Macrophages Uptake. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 136, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Review of FRET Biosensing and Its Application in Biomolecular Detection. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2023, 15, 694–709. [Google Scholar]

- JARESERIJMAN, E.; JOVIN, T. Imaging Molecular Interactions in Living Cells by FRET Microscopy. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006, 10, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; He, B.; Tao, J.; He, Y.; Deng, H.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Y. Application of Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) Technique to Elucidate Intracellular and In Vivo Biofate of Nanomedicines. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019, 143, 177–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.C.; Fan, Z.; Crouch, R.A.; Sinha, S.S.; Pramanik, A. Nanoscopic Optical Rulers beyond the FRET Distance Limit: Fundamentals and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6370–6404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajar, B.T.; Wang, E.S.; Zhang, S.; Lin, M.Z.; Chu, J. A Guide to Fluorescent Protein FRET Pairs. Sensors (Switzerland) 2016, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subach, F. V.; Zhang, L.; Gadella, T.W.J.; Gurskaya, N.G.; Lukyanov, K.A.; Verkhusha, V. V. Red Fluorescent Protein with Reversibly Photoswitchable Absorbance for Photochromic FRET. Chem. Biol. 2010, 17, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaner, N.C.; Campbell, R.E.; Steinbach, P.A.; Giepmans, B.N.G.; Palmer, A.E.; Tsien, R.Y. Improved Monomeric Red, Orange and Yellow Fluorescent Proteins Derived from Discosoma Sp. Red Fluorescent Protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 1567–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, R.E.; Tour, O.; Palmer, A.E.; Steinbach, P.A.; Baird, G.S.; Zacharias, D.A.; Tsien, R.Y. A Monomeric Red Fluorescent Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99, 7877–7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbakova, D.M.; Subach, O.M.; Verkhusha, V. V. Red Fluorescent Proteins: Advanced Imaging Applications and Future Design. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10724–10738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Guerra, J.; Palomar-Pardavé, M.; Romero-Romo, M.; Corona-Avendaño, S.; Guzmán-Hernández, D.; Rojas-Hernández, A.; Ramírez-Silva, M.T. On the Curcumin and Β-Cyclodextrin Interaction in Aqueous Media. Spectrophotometric and Electrochemical Study. ChemElectroChem 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Kasoju, N.; Goswami, P.; Bora, U. Encapsulation of Curcumin in Pluronic Block Copolymer Micelles for Drug Delivery Applications. J. Biomater. Appl. 2011, 25, 619–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, P.; Mishra, B.; Mudavath, S.L.; Patel, R.R.; Chaurasia, S.; Sundar, S.; Suvarna, V.; Monteiro, M. Mannose-Conjugated Curcumin-Chitosan Nanoparticles: Efficacy and Toxicity Assessments against Leishmania Donovani. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Xiao, L.; Qin, W.; Loy, D.A.; Wu, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Q. Preparation, Characterization and Antioxidant Properties of Curcumin Encapsulated Chitosan/Lignosulfonate Micelles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 281, 119080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Majedy, Y.; Kadhum, A.A.; Ibraheem, H.; Al-Amiery, A.; Moneim, A.A.; Mohamad, A.B. A Systematic Review on Pharmacological Activities of 4-Methylumbelliferon. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2018, 9, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Majedy, Y.K.; Al-Amiery, A.A.; Kadhum, A.A.H.; Mohamad, A.B. Antioxidant Activities of 4-Methylumbelliferone Derivatives. PLoS One 2016, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medimagh-Saidana, S.; Romdhane, A.; Daami-Remadi, M.; Jabnoun-Khiareddine, H.; Touboul, D.; Jannet, H. Ben; Hamza, M.A. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of Novel Coumarin Derivatives from 4-Methylumbelliferone. Med. Chem. Res. 2015, 24, 3247–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhu, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Xu, X.; Yin, W.; Sima, Y.; Xu, S. Antioxidative Properties of 4-Methylumbelliferone Are Related to Antibacterial Activity in the Silkworm (Bombyx Mori) Digestive Tract. J. Comp. Physiol. B Biochem. Syst. Environ. Physiol. 2014, 184, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raval, N.; Maheshwari, R.; Shukla, H.; Kalia, K.; Torchilin, V.P.; Tekade, R.K. Multifunctional Polymeric Micellar Nanomedicine in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 126, 112186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Ezhov, A.A.; Dobryakova, N. V.; Kudryashova, E. V. Disulfide Cross-Linked Polymeric Redox-Responsive Nanocarrier Based on Heparin, Chitosan and Lipoic Acid Improved Drug Accumulation, Increased Cytotoxicity and Selectivity to Leukemia Cells by Tumor Targeting via “Aikido” Principle. Gels 2024, 10, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ping, Q.; Zhang, H.; Shen, J. Preparation of N-Alkyl-O-Sulfate Chitosan Derivatives and Micellar Solubilization of Taxol. Carbohydr. Polym. 2003, 54, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, R.; Jin, X.; Li, N.; Ju, C.; Sun, M.; Zhang, C.; Ping, Q. The Mechanism of Enhancement on Oral Absorption of Paclitaxel by N-Octyl-O-Sulfate Chitosan Micelles. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 4609–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotta, S.; Aldawsari, H.M.; Badr-Eldin, S.M.; Nair, A.B.; YT, K. Progress in Polymeric Micelles for Drug Delivery Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganta, S.; Devalapally, H.; Shahiwala, A.; Amiji, M. A Review of Stimuli-Responsive Nanocarriers for Drug and Gene Delivery. J. Control. Release 2008, 126, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, S.; Gorzelanny, C.; Moerschbacher, B.; Goycoolea, F.M. Physicochemical Characterization of FRET-Labelled Chitosan Nanocapsules and Model Degradation Studies. Nanomaterials 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Han, J.; Zhao, F.; Pan, X.; Tian, B.; Ding, X.; Zhang, J. Redox-Sensitive Micelles Based on Retinoic Acid Modified Chitosan Conjugate for Intracellular Drug Delivery and Smart Drug Release in Cancer Therapy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 215, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Ezhov, A.A.; Ferberg, A.S.; Krylov, S.S.; Semenova, M.N.; Semenov, V. V.; Kudryashova, E. V. Polymeric Micelles Formulation of Combretastatin Derivatives with Enhanced Solubility, Cytostatic Activity and Selectivity against Cancer Cells. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Araújo, M.; Novoa-Carballal, R.; Andrade, F.; Gonçalves, H.; Reis, R.L.; Lúcio, M.; Schwartz, S.; Sarmento, B. Novel Amphiphilic Chitosan Micelles as Carriers for Hydrophobic Anticancer Drugs. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 112, 110920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaucher, G.; Satturwar, P.; Jones, M.C.; Furtos, A.; Leroux, J.C. Polymeric Micelles for Oral Drug Delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2010, 76, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junnuthula, V.; Kolimi, P.; Nyavanandi, D.; Sampathi, S.; Vora, L.K.; Dyawanapelly, S. Polymeric Micelles for Breast Cancer Therapy: Recent Updates, Clinical Translation and Regulatory Considerations. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Sirvi, A.; Kaur, S.; Samal, S.K.; Roy, S.; Sangamwar, A.T. Polymeric Micelles Based on Amphiphilic Oleic Acid Modified Carboxymethyl Chitosan for Oral Drug Delivery of Bcs Class Iv Compound: Intestinal Permeability and Pharmacokinetic Evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 153, 105466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Chen, M.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Polymeric Micelles Drug Delivery System in Oncology. J. Control. Release 2012, 159, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Kudryashova, E. V Smart Polymeric Micelles System, Designed to Carry a Combined Cargo of L-Asparaginase and Doxorubicin, Shows Vast Improve- Ment in Cytostatic Efficacy. 2024, 4, 1–26.

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Streltsov, D.A.; Belogurova, N.G.; Kudryashova, E. V. Chitosan or Cyclodextrin Grafted with Oleic Acid Self-Assemble into Stabilized Polymeric Micelles with Potential of Drug Carriers. Life 2023, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, R.S. The Role of Low-Molecular-Weight Heparins as Supportive Care Therapy in Cancer-Associated Thrombosis. Semin. Oncol. 2006, 33, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Liu, M.; Yang, X.; Zhai, G. The Design of PH-Sensitive Chitosan-Based Formulations for Gastrointestinal Delivery. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Su, Z.; Ma, G. A Thermo- and PH-Sensitive Hydrogel Composed of Quaternized Chitosan / Glycerophosphate. 2006, 315, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Panja, S.; Aich, P.; Jana, B.; Basu, T. How Does Plasmid DNA Penetrate Cell Membranes in Artificial Transformation Process of Escherichia Coli? Mol. Membr. Biol. 2008, 25, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chignell, C.F.; Bilskj, P.; Reszka, K.J.; Motten, A.G.; Sik, R.H.; Dahl, T.A. SPECTRAL AND PHOTOCHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF CURCUMIN. Photochem. Photobiol. 1994, 59, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Ezhov, A.A. Intermolecular FRET Pairs as An Approach to Visualize Specific Enzyme Activity in Model Biomembranes and Living Cells. 2024, 340–356.

- Negi, N.; Prakash, P.; Gupta, M.L.; Mohapatra, T.M. Possible Role of Curcumin as an Efflux Pump Inhibitor in Multi Drug Resistant Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. J. Clin. Diagnostic Res. 2014, 8, DC04–DC07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altınöz, E.; Altuner, E.M. Observation of Efflux Pump Inhibition Activity of Naringenin, Quercetin, and Umbelliferone on Some Multidrug-Resistant Microorganisms. 2021, 11486. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.L.A.R.; Pereira, R.L.S.; Rocha, J.E.; Farias, P.A.M.; Freitas, T.S.; de Lemos Caldas, F.R.; Figueredo, F.G.; Sampaio, N.F.L.; Ribeiro-Filho, J.; Menezes, I.R. de A.; et al. In Vitro and in Silico Evidences about the Inhibition of MepA Efflux Pump by Coumarin Derivatives. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 182, 106246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(a) Schematics of polymer micelles and structures of modified chitosans and heparins. (b) FTIR spectra of chitosan, lipoic acid, oleic acid, and chitosan grafted with oleic acid or lipoic acid residues – M1 and M2. (c) FTIR spectra of heparin, lipoic acid, oleic acid, and heparin grafted with oleic acid or lipoic acid residues – M3 and M4.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematics of polymer micelles and structures of modified chitosans and heparins. (b) FTIR spectra of chitosan, lipoic acid, oleic acid, and chitosan grafted with oleic acid or lipoic acid residues – M1 and M2. (c) FTIR spectra of heparin, lipoic acid, oleic acid, and heparin grafted with oleic acid or lipoic acid residues – M3 and M4.

Figure 2.

(a) FTIR spectra of curcumin in free form and loaded into polymer micelles M1-M4. PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). (b)-(c) 1H NMR spectra of Hep-OA micelles in D2O and Hep-OA micelles loaded with curcumin in D2O. T = 37 °C.

Figure 2.

(a) FTIR spectra of curcumin in free form and loaded into polymer micelles M1-M4. PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). (b)-(c) 1H NMR spectra of Hep-OA micelles in D2O and Hep-OA micelles loaded with curcumin in D2O. T = 37 °C.

Figure 3.

AFM images of (a) Hep-OA empty micelles and (b) Hep-OA micelles loaded with curcumin. (c) AFM image of single E. coli cell pre-incubated with Hep-OA micelles loaded with curcumin. (d)-(f) AFM images of E. coli cells pre-incubated with Chit-LA empty micelles: (d) Focusing on the substrate reveals spherical micellar particles. (e) Height signal. (f) Magnitude signal.

Figure 3.

AFM images of (a) Hep-OA empty micelles and (b) Hep-OA micelles loaded with curcumin. (c) AFM image of single E. coli cell pre-incubated with Hep-OA micelles loaded with curcumin. (d)-(f) AFM images of E. coli cells pre-incubated with Chit-LA empty micelles: (d) Focusing on the substrate reveals spherical micellar particles. (e) Height signal. (f) Magnitude signal.

Figure 4.

(a) FRET pairs. Normalized fluorescent emission spectra of FRET donors: curcumin, MUmb, AMC in free form and in micellar Chit5-OA formulations. Normalized fluorescent spectra of FRET acceptor RFP in E. coli cells. Fluorescent spectra of curcumin in free form and in micellar formulations: (b) Chit5-LA, (c) Chit5-OA, (d) Hep-OA, (e) Hep-LA. PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

Figure 4.

(a) FRET pairs. Normalized fluorescent emission spectra of FRET donors: curcumin, MUmb, AMC in free form and in micellar Chit5-OA formulations. Normalized fluorescent spectra of FRET acceptor RFP in E. coli cells. Fluorescent spectra of curcumin in free form and in micellar formulations: (b) Chit5-LA, (c) Chit5-OA, (d) Hep-OA, (e) Hep-LA. PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

Figure 5.

Fluorescent spectra of MUmb in free form and in micellar formulations: (a) Chit5-LA, (b) Hep-OA. (c) Curves of the dependence of the maximum intensity of MUmb fluorescence on the concentration of the added polymer. (d) Linearization of (c) curves in Hill coordinates. PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

Figure 5.

Fluorescent spectra of MUmb in free form and in micellar formulations: (a) Chit5-LA, (b) Hep-OA. (c) Curves of the dependence of the maximum intensity of MUmb fluorescence on the concentration of the added polymer. (d) Linearization of (c) curves in Hill coordinates. PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

Figure 6.

(a) Experimental scheme for studying the interaction of fluorophores with bacterial cells expressing RFP using the FRET technique. (b)-(d) Petri dish experiment using bacteria expressing red fluorescent protein (RFP) as a visual platform for assessing the permeability of 0.1 mg/ml formulations of AMC, MUmb, and curcumin, both free and encapsulated in micelles. Fluorescence detection on a bioluminescent visualizer. For curcumin, a DMSO sample with a concentration of 1 mg/ml was also used as a positive control. The negative control was PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

Figure 6.

(a) Experimental scheme for studying the interaction of fluorophores with bacterial cells expressing RFP using the FRET technique. (b)-(d) Petri dish experiment using bacteria expressing red fluorescent protein (RFP) as a visual platform for assessing the permeability of 0.1 mg/ml formulations of AMC, MUmb, and curcumin, both free and encapsulated in micelles. Fluorescence detection on a bioluminescent visualizer. For curcumin, a DMSO sample with a concentration of 1 mg/ml was also used as a positive control. The negative control was PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

Figure 7.

(a) Fluorescent spectra of a suspension of E. coli bacteria (5×107 CFU/mL) with added curcumin in various concentrations and compositions. (b) The effectiveness of FRET between MUmb and red protein as a function of the time of micelle type and concentration of the amphiphilic polymer. PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

Figure 7.

(a) Fluorescent spectra of a suspension of E. coli bacteria (5×107 CFU/mL) with added curcumin in various concentrations and compositions. (b) The effectiveness of FRET between MUmb and red protein as a function of the time of micelle type and concentration of the amphiphilic polymer. PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

Figure 8.

The effect of curcumin and MUmb on the synergistic enhancement of the antibacterial activity of moxifloxacin against E. coli cells. The initial values were 2×107 CFU/mL. T = 37 °C.

Figure 8.

The effect of curcumin and MUmb on the synergistic enhancement of the antibacterial activity of moxifloxacin against E. coli cells. The initial values were 2×107 CFU/mL. T = 37 °C.

Table 1.

The physicochemical characteristics of amphiphilic conjugates derived from chitosan and heparin, with oleic or lipoic acid residues attached. The parameters of micellar solutions in a phosphate-buffered saline solution (0.01 M, pH 7.4) at a temperature of 37°C are given.

Table 1.

The physicochemical characteristics of amphiphilic conjugates derived from chitosan and heparin, with oleic or lipoic acid residues attached. The parameters of micellar solutions in a phosphate-buffered saline solution (0.01 M, pH 7.4) at a temperature of 37°C are given.

| Designation * |

Chemical formula ** |

Polymer modification degree per glycoside unit, % |

Hydrodynamic diameter, nm*** |

ζ-potential, mV**** |

| M1 |

Chit5-LA |

25 ± 3 |

180 ± 40 |

+12 ± 2 |

| M2 |

Chit5-OA |

22 ± 4 |

250 ± 60 |

+15 ± 1 |

| M3 |

Hep-OA |

13 ± 2 |

160 ± 20 |

–7 ± 1 |

| M4 |

Hep-LA |

10 ± 2 |

125 ± 10 |

–10 ± 1.5 |

Table 2.

The maximal degree of incorporation of substances into micelles is expressed in mass percentages.

Table 3.

Physico-chemical parameters of the inclusion of MUmb in polymeric micelles. PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

Table 3.

Physico-chemical parameters of the inclusion of MUmb in polymeric micelles. PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

| Micelles |

Chit-LA |

Chit-OA |

Hep-OA |

Hep-LA |

| – lg KA

|

3.16 ± 0.09 |

3.09 ± 0.30 |

5.65 ± 0.26 |

6.71 ± 0.42 |

| – lg Kd

|

3.75 ± 0.19 |

3.79 ± 0.65 |

4.69 ± 0.43 |

4.97 ± 0.62 |

| n |

0.84 ± 0.02 |

0.81 ± 0.06 |

1.20 ± 0.05 |

1.35 ± 0.08 |

| R-square |

0.998 |

0.984 |

0.994 |

0.989 |

Table 4.

RFP fluorescence intensity in a Petri dish experiment using bacteria expressing red fluorescent protein (RFP) as a visual platform for assessing the permeability of 0.1 mg/mL formulations of AMC, MUmb, and curcumin, both free and encapsulated in micelles. For curcumin, a DMSO sample with a concentration of 1 mg/mL was also used as a positive control. The negative control was PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

Table 4.

RFP fluorescence intensity in a Petri dish experiment using bacteria expressing red fluorescent protein (RFP) as a visual platform for assessing the permeability of 0.1 mg/mL formulations of AMC, MUmb, and curcumin, both free and encapsulated in micelles. For curcumin, a DMSO sample with a concentration of 1 mg/mL was also used as a positive control. The negative control was PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

| RFP fluorescence intensity, a.u. |

|---|

| Form / Compound |

MUmb |

AMC |

Curcumin |

| In PBS |

180±11 |

174±8 |

132±4 (in PBS) / 178±10 (in DMSO) |

| In Chit5-LA (M1) |

226±8 |

133±4 |

135±5 |

| In Chit5-OA (M2) |

208±10 |

146±7 |

148±7 |

| In Hep-OA (M3) |

188±5 |

205±11 |

149±5 |

| In Hep-LA (M4) |

195±13 |

228±15 |

144±6 |

| Control (RFP only) |

183±7 |

124±3 |

125±4 |

Table 5.

The effect of different drug formulations on E. coli cells viability (%). The initial values were 2×107 CFU/mL. T = 37 °C.

Table 5.

The effect of different drug formulations on E. coli cells viability (%). The initial values were 2×107 CFU/mL. T = 37 °C.

| Sample 0.1 mg/mL |