1. Introduction

L-arginine promotes intestinal growth and development and maintains the immune barrier function of the intestine including thymotropic effects[

1] and enhancement of cellular activity of lymphokine-activated killer cells[

2]. Based on these effects, L-arginine is important as a special nutrient combined with enteral nutrition preparations to maintain the normal structure and physiological function of the gastrointestinal tract and to prevent intestinal inflammation[

3,

4].

Enteral nutrition preparations consist of substances designed to provide nutritional support via the gastrointestinal tract[

5]. They contain nutrients that require minimal chemical digestion or need no digestion[

6]. Administering enteral nutrition effectively enhances blood flow to the gastric mucosa and helps maintain the barrier function of the gastrointestinal lining, as well as the health of the intestinal flora, all of which contribute to the recovery of gastrointestinal function[7-9]. These preparations are primarily composed of nitrogen sources, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, minerals, and fiber. With its high nutrient density, multi-targeted functional activity and good processing characteristics, silkworm pupa protein has been confirmed by many studies as a potential high-quality EN candidate[

10,

11], especially for metabolic diseases and intestinal inflammation adjuvant therapy[

12]. Its mechanism of action covers metabolic regulation[

13], immune enhancement and barrier repair, which is in line with the development trend of “nutrition-function integration” of modern EN preparations.

Diabetes mellitus, a multifactorial metabolic disorder characterized by chronic hyperglycemia and systemic inflammation, underscores the critical interplay between nutrient metabolism and immune dysregulation. Gastrointestinal symptoms are very common in diabetic patients, up to 75% of the total cases[

14,

15]. Conventional therapeutic strategies often prioritize glycemic control through pharmacological modulation of insulin signaling or glucose absorption[

16,

17], yet these approaches frequently overlook the bidirectional interaction between metabolic homeostasis and mucosal immunity[

18,

19]. Emerging evidence highlights the potential of bioactive enteral nutrition (EN) formulations to synergistically address both metabolic dysfunction and immune imbalance—a paradigm termed "immunometabolic modulation"[

20]. Notably, specialized EN formulations enriched with immunonutritional components (e.g., antioxidant peptides, prebiotic fibers, and anti-inflammatory amino acids) may exert dual therapeutic effects.

In this study, a self-made enteral nutrition preparation was formulated using silkworm chrysalis protein as the nitrogen source, alongside tapioca starch and corn starch as energy-providing sugars, and oligofructose and isomaltose. Additionally, fish oil and olive oil were included as fat sources to supply calories and essential fatty acids. A variety of vitamins, minerals, and specific nutrients such as arginine were also added. The preparation was tested on a mouse model of small intestinal inflammation induced by LPS, and the results demonstrated that it possesses significant intestinal antibacterial properties. Furthermore, the preparation exhibited robust intestinal anti-inflammatory and protective effects.

2. Results

2.1. Histopathological manifestations

Shown in , Control Group (CG,

Figure 1) demonstrated intact intestinal architecture with clearly defined mucosal layer, submucosa, and muscularis propria. Villus structures remained intact without observable damage. LPS Group (LG) exhibited significant pathological alterations including prominent inflammatory cell infiltration within villus structures, thinning of muscularis layer, progressive separation between muscularis and submucosal layers and villus detachment and necrotic changes. These findings confirm the successful establishment of intestinal inflammatory injury. Low- and High-Dose Enteral Nutrition Groups (ELG/EHG) showed partial improvement characterized by decreased villus detachment and separation between submucosal and muscular layers. Medium-Dose Enteral Nutrition Group (EMG): Displayed optimal protective effects against inflammatory injury with relatively higher villus integrity and distinct stratification of mucosal and submucosal layers.

2.2. Blood parameters

As shown in

Table 2, the WBC and PLT in the LG, ELG, EMG, and EHG groups were significantly lower than those in the CG group (P < 0.05), and at the same time, they were significantly higher than those in the LG group in the ELG, EMG, and EHG groups (P < 0.05), with the highest values of WBC and PLT in the EMG group. Compared with the CG group, the RBC values in the LG, ELG, and EHG groups were reduced and produced significant differences (P < 0.05), and there was no significant difference with the EMG group. HGB values were significantly higher in the ELG and EMG groups compared to the LG group (P < 0.05), and the difference with EHG was not significant.

2.3. Cytokine Profiling in Intestinal Tissues

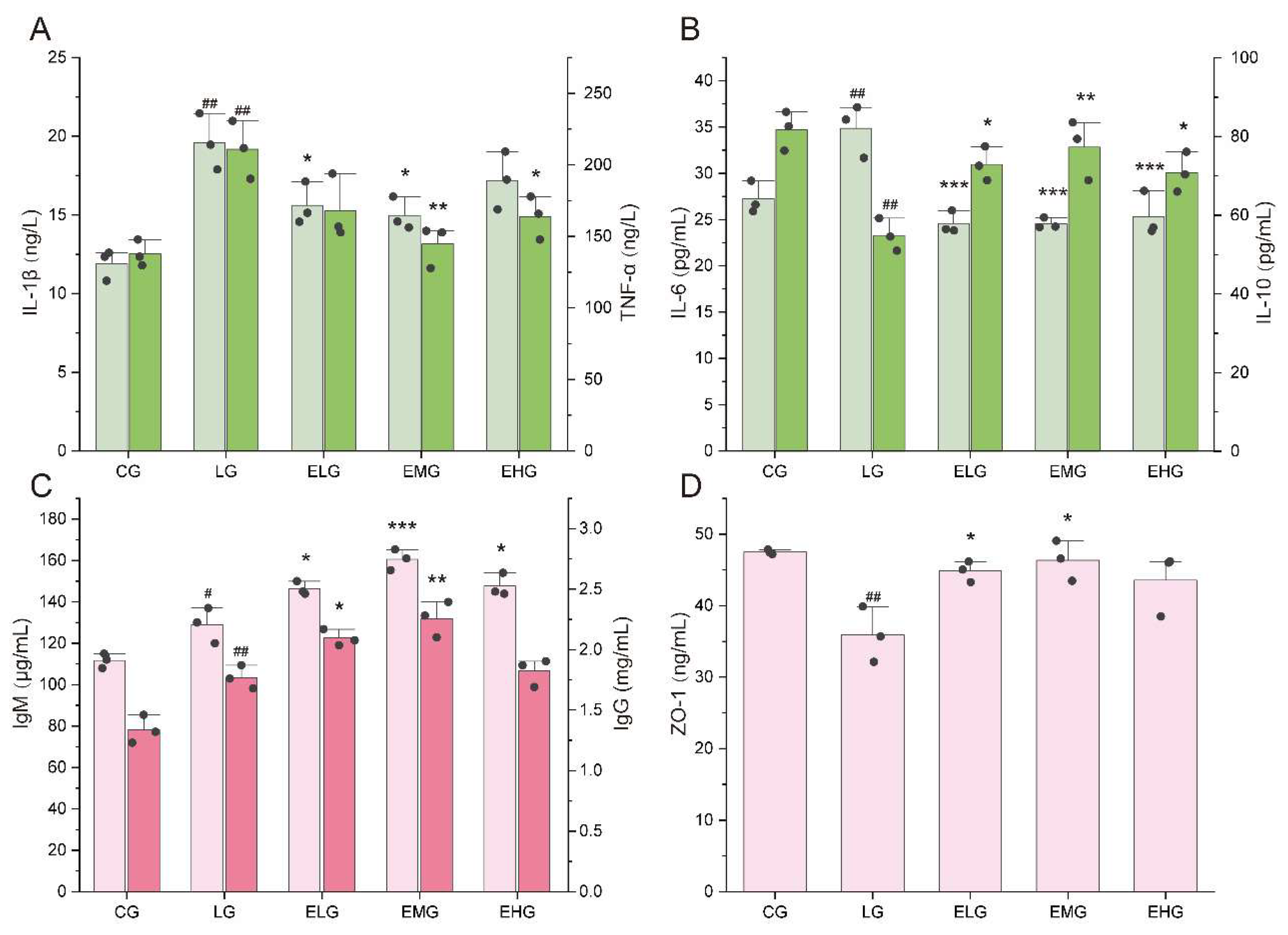

As illustrated in

Figure 2A and 2B, significant alterations in inflammatory cytokine levels were observed across experimental groups. Comparing LPS Group (LG) with Control Group (CG), Pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 witnessed a significant increase. IL-1β increased from 11.91 ng/L (CG) to 19.60 ng/L (LG) (P < 0.001), TNF-α rose from 137.70 ng/L to 210.90 ng/L (P < 0.01), IL-6 elevated from 27.22 pg/mL to 34.85 pg/mL (P < 0.01). For anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 decreased from 81.73 pg/mL (CG) to 54.92 pg/mL (LG) (P < 0.01). These findings confirm pronounced intestinal inflammation in the LG group.

For intervention groups (ELG/EMG/EHG) comparing with LG group, regarding IL-1β, ELG and EMG exhibited significant reductions to 15.60 ng/L and 14.97 ng/L, respectively (P < 0.05), while EHG showed a non-significant decrease to 17.19 ng/L. For TNF-α level, EMG and EHG demonstrated marked declines to 144.70 ng/L (P < 0.01) and 163.70 ng/L (P < 0.05), respectively, with EHG further decreasing to 167.70 ng/L (non-significant trend). All treatment groups showed robust suppression for IL-6 level, meanwhile, elevated levels were observed in all intervention groups of IL-10 level.

2.4. Immunoglobulin and Tight Junction Protein Level

As demonstrated in Figure 2C and 2D, for LG and CG, immunoglobulin levels in intestine tissue both increased after the injection of LPS solution: level of IgM increased from 111.7 µg/mL (CG) to 129.00 µg/mL (LG) (P < 0.05), IgG rose from 1.34 mg/mL to 1.77 mg/mL (P < 0.01). ZO-1 decreased from 47.49 ng/mL to 35.89 ng/mL (P < 0.01), which may indicate intestinal immune hyperactivation and copromised barrier function in the LG group.

Overall, mucosal immunity was enhanced through upregulated immunoglobulin production (IgM/IgG) and restored intestinal barrier integrity via ZO-1 recovery. Medium-dose (EMG) intervention demonstrated superior efficacy, achieving maximal IgM elevation (22.4% vs LG) and near-normalization of ZO-1 levels (46.35 ng/mL vs CG baseline 47.49 ng/mL).

2.5. CD4+ T Lymphocyte Infiltration Analysis

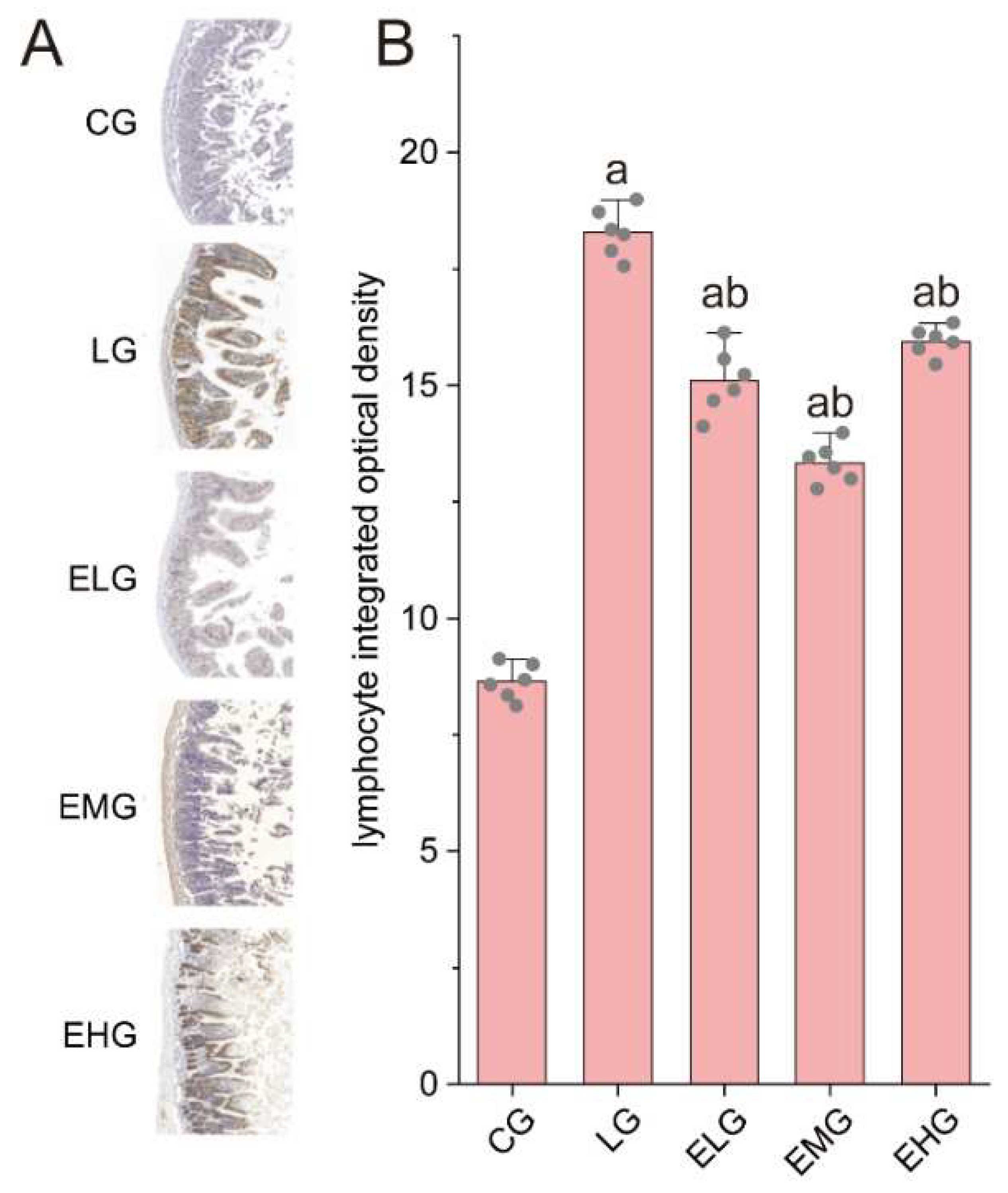

As shown in

Figure 3A, immunohistochemical staining revealed distinct patterns of CD4+ T lymphocyte distribution across experimental groups. The Control Group (CG, Figure 3A) exhibited sparse CD4+ T lymphocytes with weak positivity, while the LPS Group (LG, Figure 4b) displayed dense accumulation of brown or yellow stained CD4+ T cells in mucosal and submucosal layers, consistent with LPS-induced inflammatory infiltration and barrier dysfunction. In contrast, intervention groups (ELG/EMG/EHG) showed marked reductions in CD4+ T lymphocyte density, with cells localized predominantly in mucosal regions.

Quantitative analysis (

Figure 3B) confirmed these observations: Integrated optical density (IOD) values for CD4+ T cells increased significantly from 8.64 ± 0.38 (CG) to 18.29 ± 0.52 in LG (P < 0.05). All treatment groups demonstrated attenuated IOD values compared to LG. These data may be a sign of silkworm pupa protein enteral nutrition formulation effectively suppressed CD4+ T lymphocyte proliferation, with the medium-dose group (EMG) exhibiting the most pronounced anti-inflammatory effects.

2.6. Secretory IgA (sIgA) Immunohistochemical Analysis

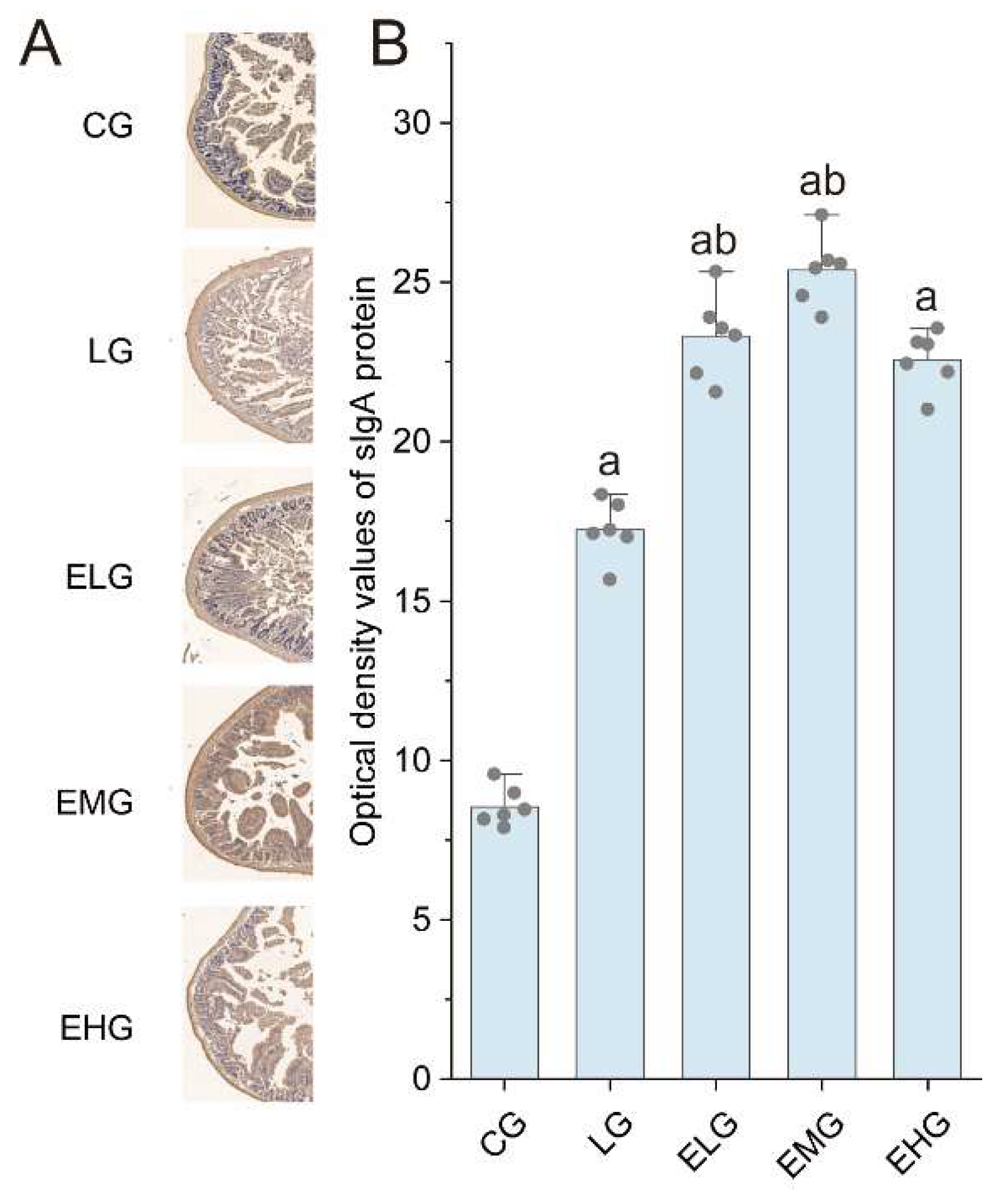

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the Control Group (CG) exhibited baseline sIgA protein distribution with characteristic brown-yellow staining, while the LPS Group (LG) displayed marked sIgA upregulation (P < 0.05 versus CG), consistent with LPS-induced mucosal immune hyperactivation. Intervention groups (ELG/EMG/EHG) demonstrated dose-dependent enhancement of sIgA expression, exceeding LG levels.

Quantitative analysis (Table 4-6) confirmed these observations: Integrated optical density (IOD) values for sIgA increased from 8.55 ± 0.62 (CG) to 17.23 ± 0.93 in LG (P < 0.05). All treatment groups exhibited further elevation(P < 0.05 versus LG).

3. Discussion

Enteral nutrition preparations are a set of substances that can provide nutritional support through the gastrointestinal route by entering some nutrients into the patient's body that require only chemical digestion or no digestion. When enteral nutrition is given, the blood flow into the gastric mucosa is effectively increased, and the barrier function of the gastrointestinal mucosa as well as the intestinal flora can be maintained, which promotes the recovery of the gastrointestinal function. Enteral nutrition preparations are mainly composed of nitrogen sources, sugars, fats, vitamins, minerals, and fiber.

Silkworm pupae protein is rich in a wide variety of amino acids, with an essential-to-nonessential amino acid ratio that surpasses the amino acid reference pattern proposed by WHO/FAO[

21,

22]. Moreover, silkworm pupae protein exhibits significant physiological properties, including the promotion of cell proliferation, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities[

23]. Fish oil, which is abundant in EPA and DHA, has been widely utilized as an immunomodulator[

24,

25]. Evidence from animal models and clinical trials has demonstrated that long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids can reduce inflammatory responses associated with inflammatory bowel disease and enhance intestinal immunity[

26]. Olive oil, known for its excellent nutritional and sensory qualities, contains low levels of free fatty acids and has been shown to reduce inflammation risk in the body. Additionally, arginine plays a critical role in enhancing immune function, supporting growth and development, protecting intestinal mucosa, and promoting metabolism, making it an essential component in clinical nutritional therapy[

27,

28].

CD4+ T-lymphocytes and CD8+ T-lymphocytes are present in the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract of the organism and reflect the immunity of the organism. CD4+ T lymphocytes are the main effector cells when the organism suffers from enteritis[

29], and in this study, we found that LPS led to the proliferation of large numbers of CD4+ T lymphocytes, and the feeding of mice with enteral nutritional preparations reduced the proliferation of large numbers of CD4+ T lymphocytes, and maintained the stability of the microenvironment of the small intestine.

Diarrhea is a typical symptom of intestinal inflammation, and we found that, the enteral nutrition preparation group was possibly able to slow down LPS-induced diarrhea and weight loss. Blood tests revealed that intraperitoneal injection of LPS resulted in downregulation of blood parameters while feeding the enteral nutrition preparation with silkworm pupa protein components elevated WBC, RBC, HGB and PLT levels in mice.

Intestinal sIgA, together with other immune factors in the intestine, participates in immunosurveillance, immunostabilization and immunoregulation through multiple pathways to ensure the normal physiological function of the intestine[30-32]. sIgA is an important antibody protein in the development and regression of neonatal gastroenteropathies, stress ulcers[

33], and other diseases. In this study, we found that LPS led to an increase in the expression of a large number of sIgA proteins, and sIgA could be further elevated and intestinal immunity could be improved after mice were fed with enteral nutrition preparations.

In conclusion, it can be seen that L-arginine-rich silkworm pupa protein component enteral nutrition preparation is an excellent nutritional efficacy regulation of food, can effectively alleviate LPS-induced inflammation in the small intestine of mice, reduce the inflammatory damage of small intestinal tissues, restore intestinal immune function, and protect the intestinal microenvironmental homeostasis, which provides ideas for the prevention and treatment of intestinal inflammation, improve intestinal health as well as scientific basis for the development of food formulations for special medical purposes.

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Silkworm pupa protein-based enteral nutrition preparations

The enteral nutrition preparations used in this study were formulated with the ingredient described in

Table 1. The preparation process involved thoroughly mixing the components to achieve a homogenous blend. The resulting mixture was stored at -20°C until further use.

4.2. Mice treatments

All mice experiments were conducted according to the guidelines of the Committee on Laboratory Animal Care and Use of Shanghai Ocean University. To induce gut inflammation, the mice were injected with LPS intraperitoneally[

34,

35] at a dose of 5 mg/kg. Throughout the experimental period, mice had free access to food and fresh water, and were kept at 22–25℃ with a humidity of 30%–40% and a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle.

Fifty C57BL/6 mice were randomly divided into 5 groups of 10 mice each: Control Group(CG), Negative control group or LPS Group (LG), Enteral High-dose Group (EHG), Enteral Medium-dose Group (EMG), Enteral Low-dose Group (EHG). In both CG and LG, mice were fed with normal treat for 2 weeks and then injected with sterile saline (CG) or LPS solution (LG). After feeding with enteral nutritional preparation (EHG) or 50 % enteral nutrition and 50 % normal chow (EMG) or 25 % enteral nutrition and 75 % normal chow (ELG) for 2 weeks, three groups of mice were injected with LPS solution described above.

4.3. Tissue collection and histological analyses

After 4 h of injecting LPS solution or sterile saline, all mice were sacrificed for sampling. For histological analyses, about 3 cm segment of the distal ilea was excised, then transferred in buffered 10% formaldehyde to ensure complete fixation. After fixation at 4°C for 12 hours, proceed with paraffin embedding and cut into 3- to 5- μm sections. The resulting sections were stained with H&E and other histological analysis methods.

4.4. Immunohistochemistry

3- to 5- μm sections was used for immunohistochemistry with the following monoclonal antibodies anti-CD4 (ServiceBio, Wuhan, China) and anti-sIgA (ServiceBio).

Tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, 80%, and 70%) followed by distilled water. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) using microwave irradiation. Sections were heated at medium power for 10 min, incubated without heating for an additional 10 min, and then treated at medium-low power for 7 min. After cooling to room temperature, slides were washed three times (5 min each) in PBS with gentle shaking. Non-specific binding sites were blocked with appropriate serum for 1 hr at room temperature. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate was applied to visualize immunoreactivity, and the reaction was monitored microscopically until optimal signal-to-background contrast was achieved.

4.5. Quantification of labeled cells

Representative fields of CD4 and sIgA staining were photographed with a digital camera. The number of positive cells was analyzed by integrating optical density values using Image J Fiji distribution[

36,

37]. Results are presented as the relative optical density.

4.5. Blood parameter Analysis

Blood samples were collected after 4 h of injecting LPS solution or sterile saline. Retro-orbital bleeding under anesthesia was adopted. Approximately 0.5-1.0 mL of blood was obtained from each mouse using a syringe. The collected blood samples were immediately transferred into EDTA-coated tubes to prevent coagulation. The samples were then gently mixed and stored on ice.

Hematological parameters, including white blood cell (WBC) count, red blood cell (RBC) count, blood platelet (PLT) count, and hemoglobin (HGB) concentration, were measured using an automated blood cell analyzer (BC-2800Vet, Mindray Animal).

4.6. Quantification of Inflammatory Cytokines and Immune Mediators by ELISA

Small intestine tissue samples described above were retrieved from storage at −80 °C and allowed to equilibrate at 4 °C for 10 minutes. Approximately 1 g of tissue was weighed and homogenized in 9 mL of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) using a mechanical tissue homogenizer, with all procedures performed under ice-cold conditions to minimize protein degradation. The homogenate was centrifuged at 4 °C for 20 minutes at 1,000g. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was carefully collected for immediate analysis, while residual aliquots were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent assays. IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IgM, IgG, PepT1, GLUT2, FATP4 elisa kit from Winter Song Boye Biotechnology (Beijing, China) were used according manufacturer instructions.

4.7. Statistical analysis

All data obtained from assays were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and t-test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference between the two intergroup groups, with P<0.05 indicating that the data were different and statistically significant. The GraphPad Prism (Version 9.0) and self-made python script that imports the matplotlib and scipy libraries was used for data analysis[

38,

39].

Funding

This research was funded by the Shanghai Frontiers Research Center of the Hadal Biosphere [NO. 34050002], the National Natural Science Foundation of China under [NO. 82173731], and Spain funding agency MEMORIA TÉCNICO-ECONÓMICA under [NO. HIDROXIDEN 2023].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barbul, A.; Wasserkrug, H.L.; Sisto, D.A.; Seifter, E.; Rettura, G.; Levenson, S.M.; Efron, G. Thymic stimulatory actions of arginine. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 1980, 4, 446–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbul, A.; Sisto, D.; Wasserkrug, H.; Efron, G. Arginine stimulates lymphocyte immune response in healthy human beings. Surgery 1981, 90, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yao, K.; Guan, S.; Li, T.; Huang, R.; Wu, G.; Ruan, Z.; Yin, Y. Dietary L-arginine supplementation enhances intestinal development and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in weanling piglets. British Journal of Nutrition 2011, 105, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhotnik, I.; Mogilner, J.; Krausz, M.M.; Lurie, M.; Hirsh, M.; Coran, A.G.; Shiloni, E. Oral arginine reduces gut mucosal injury caused by lipopolysaccharide endotoxemia in rat. Journal of Surgical Research 2004, 122, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B.; Roehl, K.; Betz, M. Enteral nutrition formula selection: current evidence and implications for practice. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 2015, 30, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnuson, B.L.; Clifford, T.M.; Hoskins, L.A.; Bernard, A.C. Enteral nutrition and drug administration, interactions, and complications. Nutrition in clinical practice 2005, 20, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Yin, W.; Gao, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y. The effects of early enteral nutrition on the nutritional statuses, gastrointestinal functions, and inflammatory responses of gastrointestinal tumor patients. American Journal of Translational Research 2021, 13, 6260. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Hou, M.; Wu, X.; Bao, L.; Dong, P. Impact of enteral nutrition on postoperative immune function and nutritional status. Genet Mol Res 2015, 14, 6065–6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Z.-H. Early enteral infusion of traditional Chinese medicine preparation can effectively promote the recovery of gastrointestinal function after esophageal cancer surgery. Journal of thoracic disease 2011, 3, 249. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; He, K.; Velickovic, T.C.; Liu, Z. Nutritional, functional, and allergenic properties of silkworm pupae. Food Science & Nutrition 2021, 9, 4655–4665. [Google Scholar]

- Sadat, A.; Biswas, T.; Cardoso, M.H.; Mondal, R.; Ghosh, A.; Dam, P.; Nesa, J.; Chakraborty, J.; Bhattacharjya, D.; Franco, O.L. Silkworm pupae as a future food with nutritional and medicinal benefits. Current Opinion in Food Science 2022, 44, 100818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, J.; Ma, A.; Feng, D.; He, Y.; Yan, W. Effects of silkworm pupa protein on apoptosis and energy metabolism in human colon cancer DLD-1 cells. Food Science and Human Wellness 2022, 11, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weixin, L.; Lixia, M.; Leiyan, W.; Yuxiao, Z.; Haifeng, Z.; Sentai, L. Effects of silkworm pupa protein hydrolysates on mitochondrial substructure and metabolism in gastric cancer cells. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology 2019, 22, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talley, N.J.; Young, L.; Bytzer, P.; Hammer, J.; Leemon, M.; Jones, M.; Horowitz, M. Impact of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetes mellitus on health-related quality of life. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2001, 96, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talley, N.J.; Howell, S.; Jones, M.P.; Horowitz, M. Predictors of turnover of lower gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetes mellitus. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2002, 97, 3087–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolar, M. Glycemic control and complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus. The American journal of medicine 2010, 123, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.S.; Islahudin, F.; Paraidathathu, T. Factors associated with good glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of diabetes investigation 2014, 5, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szendroedi, J.; Chmelik, M.; Schmid, A.I.; Nowotny, P.; Brehm, A.; Krssak, M.; Moser, E.; Roden, M. Abnormal hepatic energy homeostasis in type 2 diabetes. Hepatology 2009, 50, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaarala, O.; Atkinson, M.A.; Neu, J. The “perfect storm” for type 1 diabetes: the complex interplay between intestinal microbiota, gut permeability, and mucosal immunity. Diabetes 2008, 57, 2555–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Pan, T.; Wang, S.; Li, P.; Men, Y.; Tan, R.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, Y. Immunometabolism modulation, a new trick of edible and medicinal plants in cancer treatment. Food chemistry 2022, 376, 131860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelli, M.; Franza, L.; Pignataro, G.; Ojetti, V.; Covino, M.; Piccioni, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Franceschi, F. Interaction between lipopolysaccharide and gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersoug, L.G.; Møller, P.; Loft, S. Gut microbiota-derived lipopolysaccharide uptake and trafficking to adipose tissue: implications for inflammation and obesity. Obesity Reviews 2016, 17, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nature methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Computing in science & engineering 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Tang, L.; Tong, L.; Liu, H. Silkworms culture as a source of protein for humans in space. Advances in Space Research 2009, 43, 1236–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food, J.; Organisation, A.; Committee, W.H.O.A.H.E. Energy and protein requirements. In Proceedings of FAO Nutrition Meetings Report Series.

- Cao, T.-T.; Zhang, Y.-Q. Processing and characterization of silk sericin from Bombyx mori and its application in biomaterials and biomedicines. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2016, 61, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnardottir, H.H.; Freysdottir, J.; Hardardottir, I. Dietary fish oil decreases the proportion of classical monocytes in blood in healthy mice but increases their proportion upon induction of inflammation. The Journal of nutrition 2012, 142, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C. Fatty acids and immune function: relevance to inflammatory bowel diseases. International reviews of immunology 2009, 28, 506–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammatory processes and inflammatory bowel diseases. Molecular nutrition & food research 2008, 52, 885–897. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, R.; Rieckmann, J.C.; Wolf, T.; Basso, C.; Feng, Y.; Fuhrer, T.; Kogadeeva, M.; Picotti, P.; Meissner, F.; Mann, M. L-arginine modulates T cell metabolism and enhances survival and anti-tumor activity. Cell 2016, 167, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Teng, J.L.; Botelho, M.G.; Lo, R.C.; Lau, S.K.; Woo, P.C. Arginine metabolism in bacterial pathogenesis and cancer therapy. International journal of molecular sciences 2016, 17, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Km, M. The lineage decisions of helper T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002, 2, 933–944. [Google Scholar]

- Brandtzaeg, P. Secretory IgA: designed for anti-microbial defense. Frontiers in immunology 2013, 4, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corthesy, B. Role of secretory IgA in infection and maintenance of homeostasis. Autoimmunity reviews 2013, 12, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favre, L.; Spertini, F.o.; Corthésy, B. Secretory IgA possesses intrinsic modulatory properties stimulating mucosal and systemic immune responses. The Journal of Immunology 2005, 175, 2793–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finamore, A.; Peluso, I.; Cauli, O. Salivary stress/immunological markers in crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).