1. Introduction

In Portugal, the Decree-Law no. 117/2024, of December 30 [

1] aims to guide land use planning to meet the growing need for housing. The amendments were approved as part of the “Building Portugal Program”, which aims to promote the construction of public and affordable housing, due the negative trend in its construction in recent decades. So, the Decree-Law no. 117/2024 decree-law also amends the RJIGT, legal regime [

2], making it possible, on an exceptional basis, to create construction areas on land that is compatible with existing urban areas. The changes introduced are precisely in line with the General Basis Law for Public Land Policy, approved by Law no. 31/2014, of May 30 [

3]. Then, these changes are delegated to local authorities to designate the reclassification of their land use. The flexibility of Decree-Law no. 117/2024 raises the question of the technical capacity of municipalities to do this task.

On the other, at municipal level, and with the urban planning regulatory change underway (Simplex [

4]), a broader discussion on how urban planning is rigorously assessed and managed should be held. Since, the Diretor Master Plan (PDM) often have a decision-making role that is very much geared towards the political administration of the territory, the local authorities are focusing on urban management and overlook strategic issues, however the housing demands and current legal frame should be considered [

1,

2].

The Urban Regeneration Operations (ORU) are compounded by several Urban Rehabilitation Areas (ARU), comprehending central and historical areas, peripheral zones, green zones, etc., their delimitation is decided by municipal technicians, considering their urban features and size. The ORU are supported with strategic plans: the Strategic Urban Development Plan (PEDU), the Strategic Urban Rehabilitation Plan (PERU), and the Urban Rehabilitation Action Plan (PARU). The ORU aim to support housing and urban spatial planning through i) the identification of territorial and urban characteristics; ii) measures for new and renovated housing; iii) increasing public and green spaces.

Therefore, ongoing discussions increasingly emphasize the need for the PDM to change its traditional role in strategic urban management and take an active role in meeting the needs of today's society. Note that, Nuno Portas [

6] had a very clear idea about the role of communities, especially those excluded from civic participation in the creation of urban and local policies. It is up to the local authorities and their technical teams to create the models that will make this happen! Some questions arise related to urban planning, housing promotion and the communities’ quality of life: What effective value can we give to the strategic planning acts that municipalities have launched year after year in their various territories? What role do local communities play in solving local and regional housing problems? How do the communities engage in the process, and what awareness do they have of such an important territorial planning process? Will the urban and housing policies defined by political parties, which are increasingly detached from a holistic understanding of territories and echoed in an increasingly less engaging press, truly be effective? Do the monitoring process of the URA remains to be done in housing promotion at local level?

This analysis aims to demonstrate that local authorities fail to effectively utilize the strategic plans of ORU, not fully leveraging their objectives to promote and manage housing in response to recent national legal change [

1]. In addition, the General Basis Law for Public Land Policy [

3] does not define homogeneous criteria to the Regional Land-Use Plan (PROT) for all regions in Portugal. The PROT is conceived according to each region and does not allow a national uniformization in the reclassification of the urban land at the intermediate level. Therefore, the municipal authorities oversee land reclassification, without tighter control from regional authorities. Indeed, our urban territories, highly diversified and embedded in landscapes and environments that are complex, generate relevant information for the construction of sectoral policies, particularly to strengthen strategic thinking about territorial development in its holistic vision. This study target to show how the ARU and ORU tools have, in general, can support the local technicians with knowledge that should be more effectively used in defining local housing promotion and management to response to housing demands.

2. Materials and Methods

This study identifies the municipal tools their organization and contents. More focus is done the ORU aims and plans. Inside the ARU amylases, especial attention is given to the building stock: state of conservation, housing conditions, rehabilitation work, and housing promotion initiatives. The comparative analysis method aims to present the main findings from the analyses of ARU and ORU for each case study: Aru from Belmonte, Soure, Penacova, villages belonging to the Coimbra district; ARU from Historic Centre from Vila Real city; and ARU from Devesas, from Vila Nova de Gaia city. The study highlights the limitations of ARU and the building stock analyses. Among the five case studies, the ARU of the Historic Centre of Vila Real is discussed in detail, focusing on the implementation of the ELHs [

5], as it is the ARU that has successfully adopted these strategies. Then, the discussion section considers the housing conditions of social buildings, the profile of vulnerable residents, and the criteria and assessment tools used by municipal technicians to implement the EHL in the ARU of the Historic Centre of Vila Real.

3. Results

The national regulations and tools [

1,

2,

3] support the municipal management tools, that are compounded by the different plans and operations, inside the three main tools: PDM; Detailed Urban Plan (PP); and ORU. The execution and improvement of these tools oversee the municipal technicians. This section aims to show the role of municipal plans and local management strategies, especially regarding assessing the housing stock in urban areas and historic centres, highlighting how these instruments can be adjusted to promote affordable and decent housing within urban areas.

3.1. Municipal Plans and Local Management Strategies

In this study is essential to underline that PDM, in Portugal, have been revised in recent years in diverse municipalities, updating their land-use plans, zoning plans, built and archaeological heritage plans, as well as, the existing situation plan, with a typological survey. The ORU are being updated, but more slowly within municipal procedures, since the delimitation of the ARU and the respective strategic plans need to be adjusted to an in-depth analysis of the building stock and the public space involved. In addition, the municipal management is under services digital transition, with digital simplification of the procedures [

4]. The municipal plans, ORU and ARU are being integrated in digital platforms and geoportals to easily be access by both technicians and citizens. There is a need to cross-check information in the data shared on digital platforms [

7].

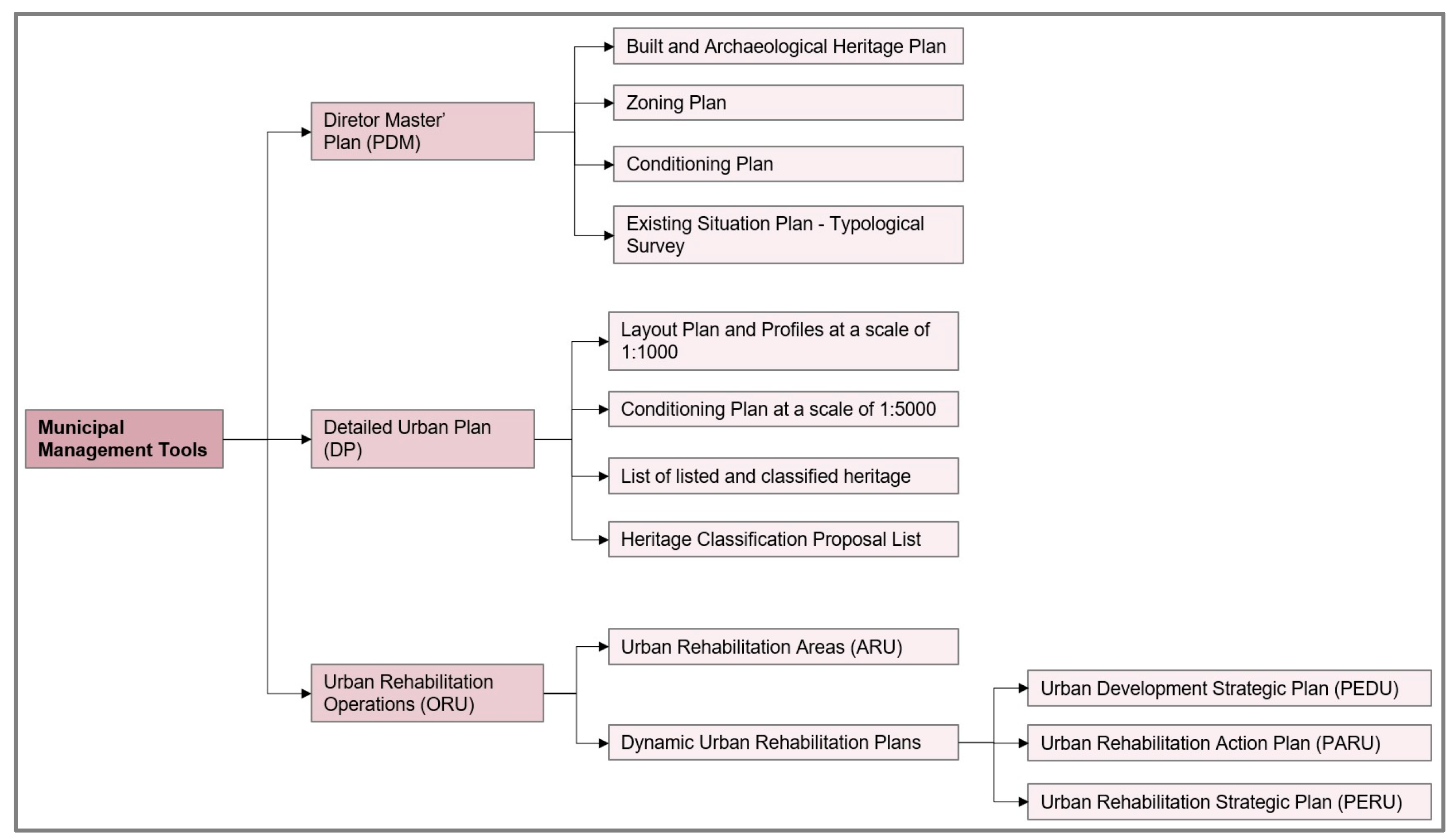

The Detailed Plans (PP) are created with urban planning concerns, focused mainly on urban requalification, particularly with a greater emphasis on public spaces. Still, there is little focus on improving housing quality. This is due to the lack of a targeted assessment of the building and housing stock, which would identify the actual rehabilitation needs and allow Detailed Plans to be adjusted to local realities. On the other hand, ARUs are defined within ORUs, and Urban Rehabilitation Dynamics Plans are incorporated, namely: i) PEDU; ii) PARU; iii) PERU (see

Figure 1). These plans focus on priority intervention areas, considering the urban features and characteristics of the territory.

3.2. ORU’ Strategic Plans

Since 2009, Urban Rehabilitation legislation [

8] has been strengthened, focusing on the integrated intervention of the existing urban fabric. The delimitation of ARU arises from the need to protect urban areas with especial intervention and/or classification requirements due to the presence of buildings with heritage attributes to be preserved; the degradation and poor habitability conditions of the buildings; the lack of infrastructure supporting housing and the population; the need to renew public spaces and various roadways. The objective of ORU within the delimited and classified ARU are allowing to: i) the implementation of national policies and regulations at the municipal level; ii) the enhancement of the urban consolidation around the city’s historic centre through urban regeneration; iii) the consolidation of the city’s urban life through the requalification of green spaces, urban spaces, and collective-use facilities, thereby boosting part of this territory that is part of the ecological structure; iv) the promotion of urban features quality through functional integration and economic diversity; v) the provision of fiscal incentives, including Value Added Tax (VAT) and Municipal Property Tax (IMI) applied to the buildings’ property owners, when living permanently in the buildings.

3.2.1. PEDU

The principal aim of the PEDU plan is to operationalize and create the conditions necessary to ensure the strategic execution defined for the ARU’ territory, considering the investment priorities estimated/ defined in the ORU.

3.2.2. PARU

The PARU plan aims to integrate a set of public projects/actions promoted by the municipalities authorities, as well as a range of private interventions that will be embraced by private sector, gathering the commitment of many property owners within the diverse ARU. The plan also includes objectives such as: enhancing the heritage and cultural identity of the community; boosting tourism attractiveness; and fostering economic and socio-cultural dynamics.

3.2.3. PERU

The PERU plan represents an opportunity to conceive the urban regeneration strategies to consolidate central and peripheric urban areas. This plan also manages the programs and allocation of the financial and human resources necessary for the implementation of the ORU.

3.3. ORU in Diverse Urban Environments

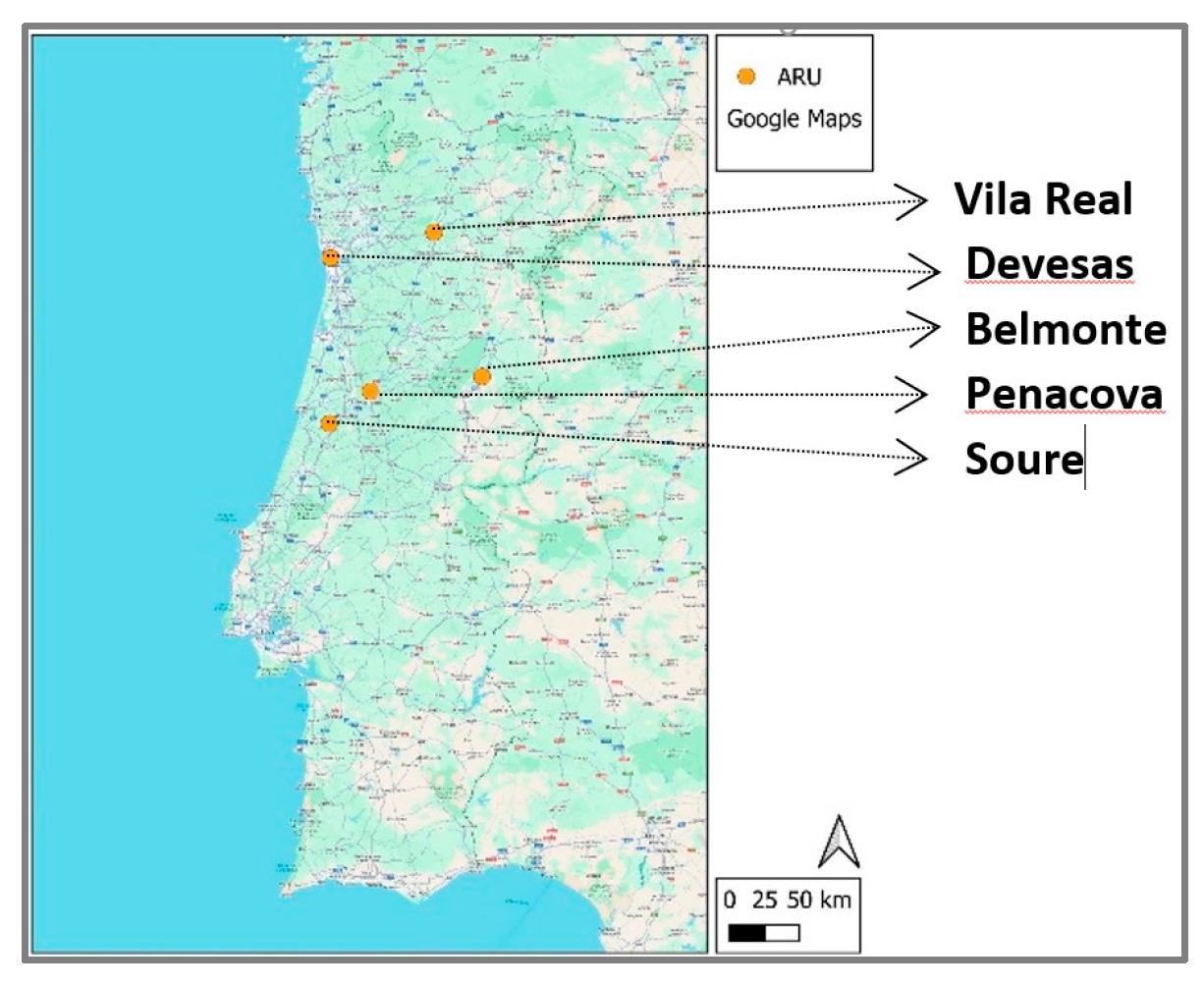

The comparative analysis from five diverse ARU (see

Figure 2), aims to compare the local authorities/ technicians in housing stock management, considering the ORU strategic plans. The analysis is focused on the ORU strategic plans (PEDU, PARU and PERU).

3.3.1. Belmonte

In the ARU of Belmonte village, the ORU strategic plans related to housing are focused on the rehabilitation of the existing housing stock [

9].

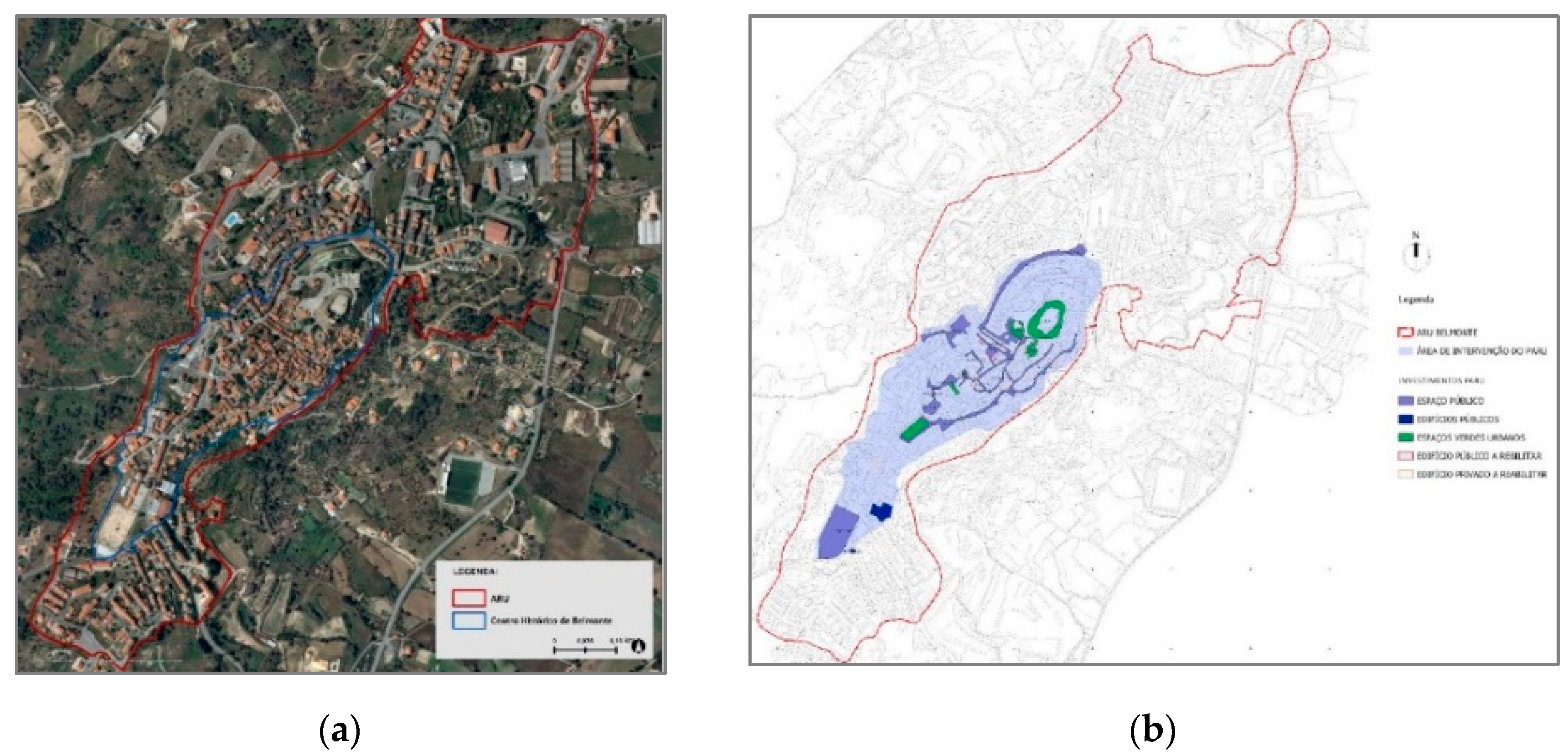

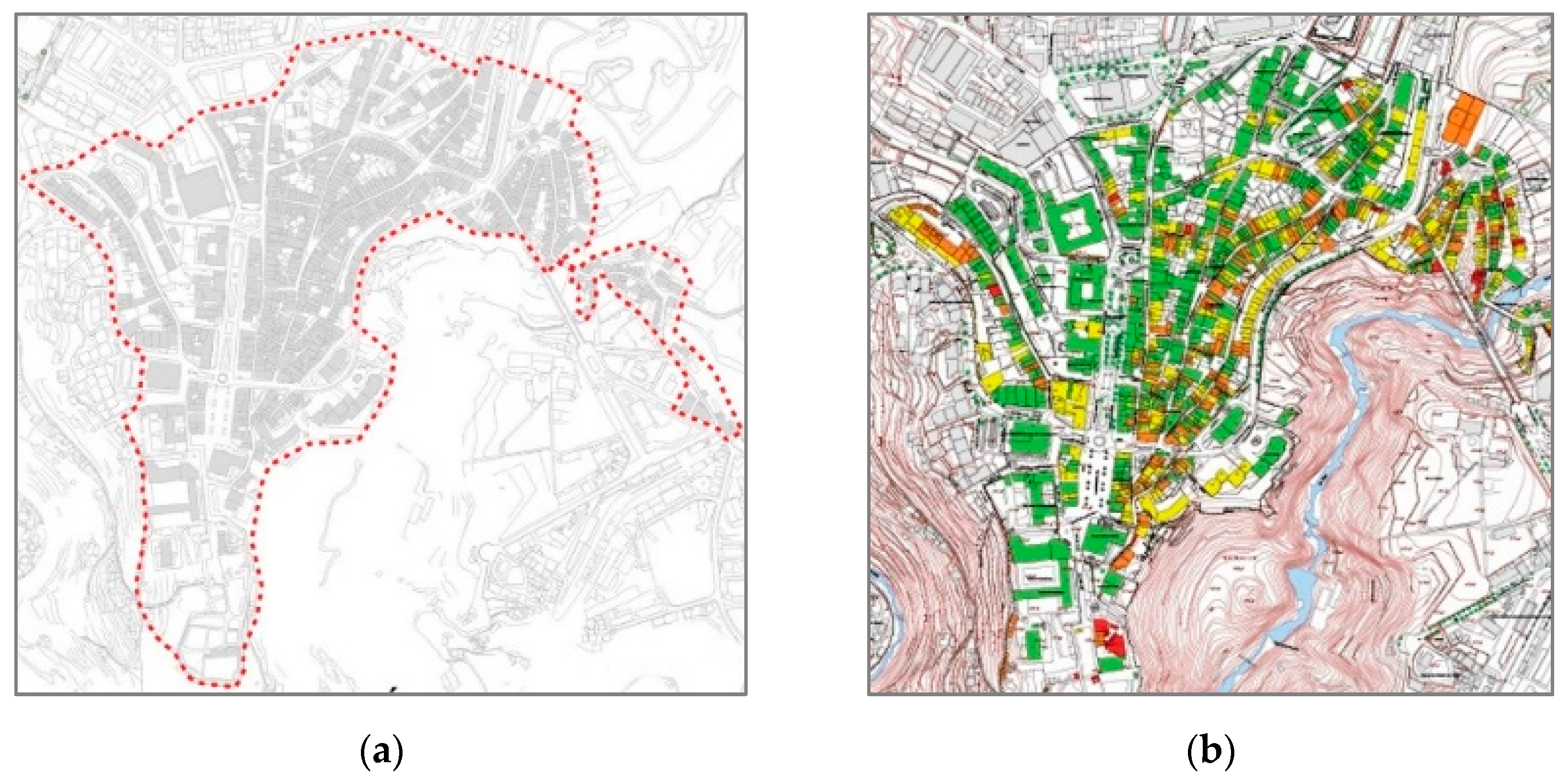

Figure 2 shows the delimitation of the ARU of Belmonte.

Figure 3.

Delimitation of the ARU and Historic Centre of Belmonte (pp. 35 and 48 [

9]) as: (

a) Delimitation on the aerial Orto map; (

b) PARU strategy for the Historic Centre.

Figure 3.

Delimitation of the ARU and Historic Centre of Belmonte (pp. 35 and 48 [

9]) as: (

a) Delimitation on the aerial Orto map; (

b) PARU strategy for the Historic Centre.

The strategic plans from the ORU, PARU is focused on the discharge of IMI for a period of three years for urban buildings or individual units, as well as for permanent housing for residence or rental purposes. The target groups are the residents and owners, that will do rehabilitation works in their houses. However, the PARU plan lacks from a holistic management strategy for housing rehabilitation (e.g., there is no quantified analyses about safety and housing conditions of existing buildings).

3.3.2. Penacova

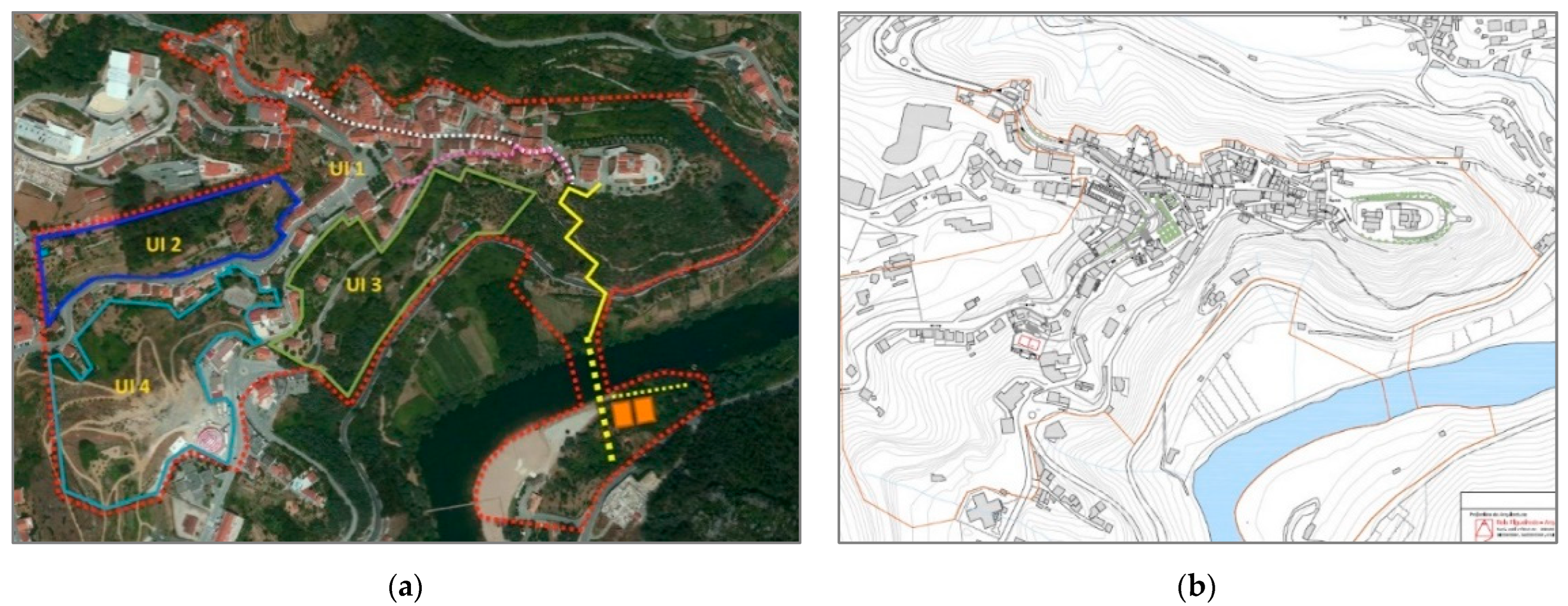

In the ARU of Penacova village, the ORU strategies plans are recognizing the need to reduce the IMT by 80% for the acquisition of urban buildings or individual units intended for permanent housing in the Intervention Unit (UI)1 area; and by 50% in the UI2 and UI3 areas [

10].

Figure 3 illustrates both the boundaries of the ARU and the boundaries of the UIs. The strategies presented in ORU from Penacova do not present differentiated management strategies for the existing built stock.

3.3.3. Soure

In the ARU of Soure village, the ORU strategies [

11] are awarded of housing stock are focused on developing solutions for access to decent housing, as a study on the condition of buildings is conducted (see

Figure 4, but without any strategic plan to prioritize strategic works, considering the level of state of conditions of the buildings. The tax benefits offered are related to the discharge of IMT for the first permanent rehabilitated housing to the owners that apply to the rehabilitation works in inside of the ARU’ buildings.

3.3.4. Historic Centre of Vila Real

In the ARU of the historic centre of Vila Real city, and considering the ORU strategies related to housing, a study on the condition of the buildings has been performed (see

Figure 5). The ORU strategic plans promotes housing rehabilitation and construction. In the areas with vulnerable residents the ELH program [

3] is conducted, encouraging the participation of local communities. It also provides social support actions to the vulnerable residents [

12].

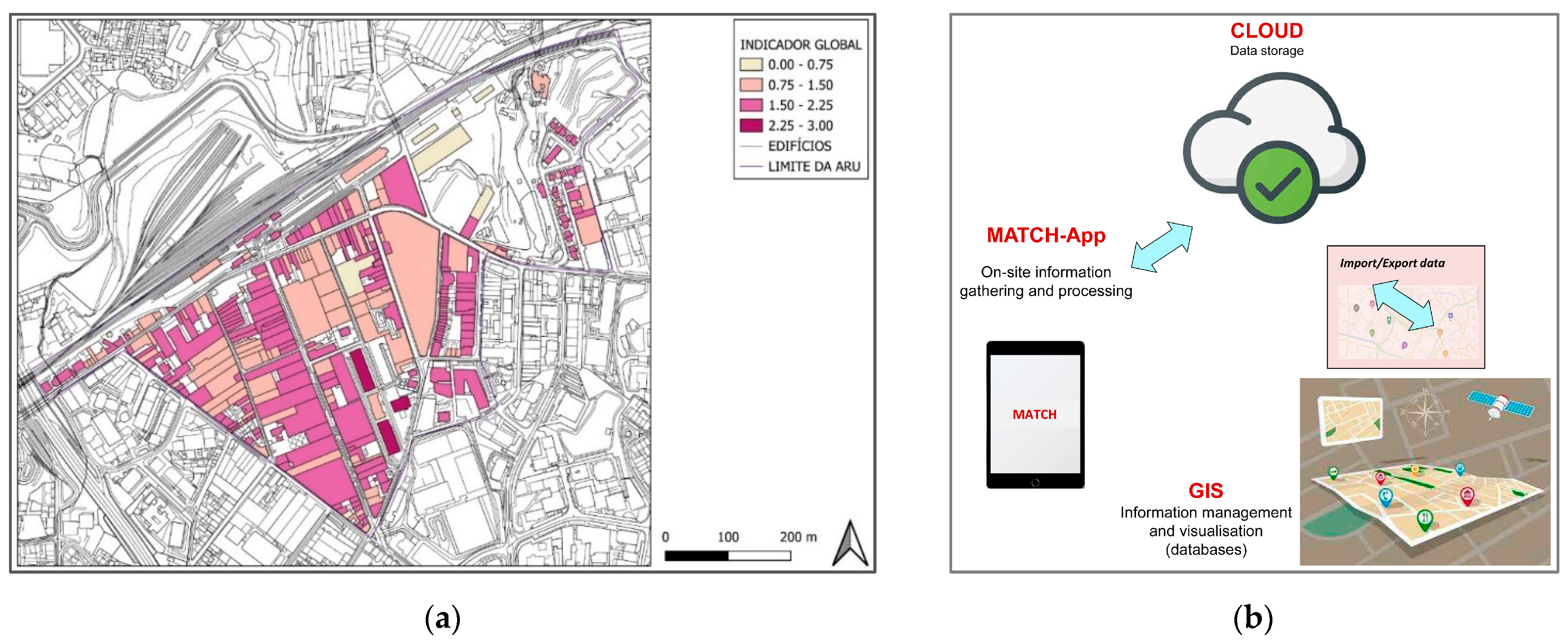

3.3.5. Devesas in Vila Nova de Gaia

The assessment of the ARU of Devesas in Vila nova de Gaia city, is part of a pilot project being developed in between GaiUrb (Municipal office) and Institute for Sustainable Construction (ICS) from FEUP, with the elaboration of two technical reports [

13,

14] and supported by an ongoing research project, that aims to implement the digital assessment at municipal level to support the stakeholders with holistic and accurate information to the decision-making. The MATCH statistical procedures are supported in previous work done and used in city centre of Porto [

15]. The MATCH-App tool is a holistic tool that assess the existing housing stock in five dimensions, identifying and quantifying the: 1- heritage attributes; 2- safety conditions; 3- habitability conditions; 4- residential satisfaction; 5- public space. The data collected by MATCH and processed in GIS (Geographical Information System) will be made available on the GaiUrb geoportal (

Figure 6), supporting ORU plans.

4. Discussion

The historic centres have been abandoned over the past few decades, turning into aging and degraded areas, the opportunity now arises to regenerate them through the rehabilitation of their buildings, giving new life to these neighbourhoods, promoting the creation of decent and affordable housing. Even before the pandemic, difficulties in accessing housing were already evident, and these difficulties worsened with its arrival, and further deteriorated with the onset of the war in Ukraine. The consequences of these events quickly affected the global economy, resulting in a significant rise in inflation and interest rates, impacting everyone, especially the most disadvantaged families. This context led to an increase in the number of households considered vulnerable, making it necessary to broaden the range and scope of support for these families through an expansion of supply and the creation of better housing conditions, aiming to respond to the different realities and needs presented. The focus is on a diversity of housing types to try to cover and provide the best response to various needs: from T1 to T4; from units in multifamily buildings to single-family homes.

Therefore, the Local Housing Strategy [

3] is an instrument that defines the intervention method in housing policy matters, and considering the need for its alignment with the Municipality's Strategic Urban Development Plan, the actions foreseen in the Integrated Action Plan for Disadvantaged Communities (PAICD), and the PARU, the definition of its objectives and implementation plan is based on a comprehensive diagnosis of the existing housing needs in the territory, prioritizing a dynamic focused on the rehabilitation of the built environment and rental housing. Thus, in line with the framework of the New Generation of Housing Policies (NGHP), approved by the Resolution of the Council of Ministers no. 50-A/2018, of May 2, municipalities play a crucial role in assessing and diagnosing the situations of housing deprivation and quality in their territories, leading to the preparation of their ELH. This document will define the intervention strategy in housing policy matters, outlining all financial support to be granted in their territories under this program. By prioritizing support for situations of inadequate and uninhabitable housing, as well as increasing the public housing supply, the targets and objectives to be achieved during its implementation period are defined, based on three main principles:

Rehabilitation of units or buildings of social housing – rehabilitating existing units already designated for social housing.

Increase in the public housing supply – as the provision of quality, affordable housing is a problem for many municipalities, it emerges as one of the main priorities, through the acquisition and rehabilitation of residential units and buildings, the acquisition and rehabilitation of units and buildings for housing purposes, and the purchase of land for the construction of buildings or housing developments.

Support for direct beneficiaries in accessing to the “1.º Direito– Housing Access Support Program” – promoting the improvement of living conditions for people living in inadequate conditions with no financial capacity to afford decent and adequate housing or even to invest in improvements to their homes; Assisting in the application process for direct beneficiaries who may apply for this support (private owners of units or urban buildings, intended for primary and permanent residence) for rehabilitation, acquisition, or construction under a self-promotion scheme, provided they meet the eligibility requirements for the mentioned program. In addition, to these principles, municipalities also foresee a municipal program to support rental housing and relocation in social housing. The aim is to create the necessary conditions to ensure access to adequate housing for households living in inadequate conditions, whose financial situation prevents them from accessing better solutions, while also contributing to the regeneration of historic centres.

Moreover, it is crucial to note that municipal authorities are not using all potential of the ARU and ORU plans; as well as the Urban Rehabilitation Companies (SRU) are not supporting the Local Housing Strategies (ELH) [

5] that should consider affordable and decent houses for citizens supported by the PRR. Besides, the ARU plans display the evaluation of the building stock, which can be an add-value to a greater investment in housing, especially in smaller-scale urban areas. Therefore, the strong effort put into ARU classification, and their proposed preservation, dynamization and revitalization (ORU) are often forgotten when they are followed by proposals for massive construction; and the residential potential that the ARU have when they have been classified for more than 10 years is underestimated. It is worth mentioning that, in many cases, existing tax incentives for the rehabilitation of local housing are insufficient to encourage property owners to rehabilitate buildings in a way that improves their habitability conditions and the quality of life for residents. Furthermore, there are no urban rehabilitation guidelines based on technical knowledge supported by traditional techniques and “in situ” expertise specific to each ARU, which would enable sustainable interventions (economically, socially, and environmentally). The lack of appropriately designed local measures leads to conflicting situations: on one hand, it fosters rampant real estate speculation with uncontrolled planning, and on the other hand, it results in the degradation of buildings occupied by vulnerable residents, where owners fail to carry out necessary maintenance. Thus, there is a clear lack of management and monitoring of ARU, that could be supported by flexible rehabilitation criteria and tools tailored to local and territorial realities.

5. Conclusions

The ARU should be understood as urban areas that need to be inhabited, and whose housing management and promotion should go beyond fiscal incentives and/or generic intervention actions that are not suited to the local housing realities, nor to the built heritage that needs to be protected, inventoried, and classified.

On the other hand, ELH can be understood as an anchor for the survival and rebirth of ARU, promoting their rehabilitation and the retention of residents, reintegrating them into the life of their communities, by attracting new families from different age groups, creating more inclusive and diverse cities, where the life and essence of these residential areas are restored.

Thus, the strategies of ORU should include flexible guidelines and intervention plans, based on digital databases with data measured through a systematic assessment and monitoring system “in situ”, of the housing stock and built environment. Furthermore, this data could be coordinated between the State and local authorities, creating a future support line originating from the PRR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Cilísia Ornelas and Carlos Figueiredo; methodology, Cilísia Ornelas; EHL investigation, Ana Morgado; ARU resources, Carlos Figueiredo; data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review, editing, and funding acquisition by Cilísia Ornelas. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work carried out by the author Cilísia Ornelas* is funded by FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology, Portugal, co-financed by the European Social Fund, namely through the Scientific Employment Stimulus Program, with reference: 2021.01733.CEECIND”with DOI 10.54499/2021.01733.CEECIND/CP1679/CT0015 (

https://doi.org/10.54499/2021.01733.CEEIND/ CP1679 /CT0015); and financially supported by Programmatic funding – “UIDP/04708/2020 with DOI 10.54499/UIDP/04708/2020 (

https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/04708/2020) of the CONSTRUCT - Instituto de I&D em Estruturas e Construções - funded by national funds through the FCT/MCTES (PIDDAC).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vila Nova de Gaia Municipality Administration for allowing the use of the graphic material used in the manuscript, as well as all the contributions made by local technicians. Special credits go to Institute for Sustainable Construction (ICS-FEUP) which collaborated, with the main author of this paper, on the work carried out in the Devesas ARU in Vila Nova de Gaia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARU |

Urban Rehabilitation Areas |

| ELH |

Local Housing Strategies |

| IMI |

Municipal Property Tax |

| IMT |

Municipal Transaction Tax |

| MATCH |

Monitoring and Assessment Tool for Cultural Heritage |

| NGHP |

New Generation of Housing Policies |

| ORU |

Urban Rehabilitation Operations |

| PAICD |

Action Plan for Disadvantaged Communities |

| PARU |

Urban Rehabilitation Action Plan |

| PEDU |

Urban Development Strategic Plan |

| PERU |

Urban Rehabilitation Strategic Plan |

| PDM |

Diretor Master Plan |

| PROT |

Regional Land-Use Plan |

| PRR |

Recovery and Resilience Plan |

| RJIGT |

Legal Regime for Land Management Instruments |

| SRU |

Urban Rehabilitation Companies |

| UI |

Intervention Units |

| VAT |

Value Added Tax |

References

- Presidency of the Council of Ministers. (2024). Decree-Law no. 117/2024, 30th December, Amends Legal Framework for Territorial Management Instruments, approved by Decree-Law no. 80/2015, 14th May, Lisbon: Diário da República: Series I (252) 1-8.

- Ministry of the Environment, Spatial Planning and Energy. (2015). Decree-Law no. 80/2015: Legal Framework for Territorial Management Instruments – RJIGT, Lisbon: Diário da República, series I (93) 2459-2512.

- Assembly of the Republic. (2014). Law no. 31/2014, 30th May, law on the general bases of public policy on soil, spatial planning and urbanism, Lisbon: Diário da República, Series I (104) 2988-3003.

- https://www.defesa.gov.pt/pt/adefesaeeu/simplex.

- Ordinance 230. (2018). 1.º Direito - Support Programme for Access to Housing, Decree-Law 37/2018, Lisboa: Diário da República, Series I (158) 4216-4223.

- Portas, Nuno. (1986). “O Processo SAAL entre o Estado e o Poder Local” In Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, no. 18, 19 e 20.

- CCDRC/ DSOT. (2019). “Guia Orientador da Revisão do PDM”. (Coord. Bento, Maria & Santos, Carla). www.ccdrc.pt.

- Assembly of the Republic. (2012). Law no. 32/2012, 14th August, makes the first amendment to Decree-Law 307/2009 of 23 October, which establishes the legal framework for urban rehabilitation, and the 54th amendment to the Civil Code, approving measures to speed up and boost urban rehabilitation.

- Belmonte Municipality. (2021). Delimitation of the Belmonte ARU and Belmonte ORU - Strategic Urban Rehabilitation Programme, Território XXI, https://www.cm-belmonte.pt.

- Penacova Municipality and Parish. (2015). Proposal for the Delimitation of the Urban Rehabilitation Area (ARU), Descriptive and Justifying Memorandum. www.cm-penacova.pt.

- Soure Municipality. (2018). Strategic Urban Rehabilitation Programme, https://www.cm-soure.pt/.

- Vila Real Municipality. (2017). Proposal for the Delimitation of the Historic Centre Urban Rehabilitation Area, http://www.cm-vilareal.pt.

- ICS-FEUP. (2023). Application of the MATCH Tool to the Devesas Quarter, Vila Nova de Gaia Portugal, Phase 1 Report.

- ICS-FEUP. (2024). Application of the MATCH Tool to the Devesas Quarter, Vila Nova de Gaia Portugal, Phase 2 Report.

- Cilísia Ornelas; Fernanda Sousa; João Miranda Guedes; Isabel Breda-Vázquez. (2023). "Monitoring and Assessment Heritage Tool: Quantify and classify urban heritage buildings". [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).