1. Introduction

Architecture and construction are a large part of the material cultural heritage of cities. In particular, townhouses, with their facades filling the streets and squares of historic centres, characterise the urban landscape. Architectural cultural heritage is also a visual expression of many intangible heritage values - the skills and traditions associated with architecture and construction. Without the knowledge passed down from generation to generation, parts of buildings would be at risk of not being able to be conserved or reconstructed.

Architectural heritage is an excellent tool for shaping the identity of a place. Townhouses, which have common and homogeneous features and are the most numerous form of urban development, have great potential for creating a specific genius loci. The consistent use of traditional decoration or building techniques, the revitalisation of historic buildings, the creation of modern buildings on their motifs by adding new but coherent elements, is an opportunity to create places attractive to both tourism and the local community, to revitalise depopulated towns or neighbourhoods, to create jobs and to prevent the population from becoming allochthonous.

However, this part of architectural heritage, despite its high cultural, social and economic values, is often inadequately protected and used. In order to maintain the relevance of historic residential architecture in changing socio-economic conditions, superficial measures such as repairs to building facades are not enough. Traditional construction should be properly combined with modern technologies, allowing housing to adapt to the requirements of modern society, while at the same time not losing the historic substance and its uniqueness, not obliterating tradition, but creating its continuation. In this process, it is necessary to have public understanding of the cultural values of the surrounding buildings and the possibilities and ways to adapt them to modern requirements.

1.1. Research Aim

The aim of the study was to demonstrate the value and potential of residential buildings forming a distinctive cityscape as an important part of the architectural cultural heritage, which can also be an identifier of the city. On the example of selected centres, it was examined whether the unique, traditional and uniform residential buildings filling the streets and squares of cities can be a carrier of historical and social cultural values and a distinguishing feature - a sign of the city, differentiating it from others.

Another research problem was the impact of multifaceted and interdisciplinary activities on revitalisation outcomes. The research highlighted the need to combine multiple factors to consequently maintain the uniqueness of historic buildings combined with meeting the needs of 21st century communities. For each of the examples described, the actions varied and were tailored to local needs.

The need to protect intangible heritage - the ability to perform traditional building and artistic crafts by educating young people in these areas - was also emphasised. In addition, the need to educate local communities and their participation in all decisions was highlighted. Only sustainable actions in the cultural, social and economic fields, as well as in the architectural and urban planning fields, preceded by thorough research and public consultation, can produce a good and lasting effect, serving future generations.

1.2. Literature Review

A number of studies have been written on the architectural heritage of cities, shaping the urban landscape, highlighting identity and “genius loci.” Researchers have considered the meaning of the term “identity” itself, which can be understood and addressed in different ways [

1,

2]. Attention was also drawn to the need to create indicators for measuring place identity to help find a common reference point. These issues were raised by Paulina Dudzik-Deko and Joanna Rzeźnik, among others, describing various research methods and creating their own indicator for measuring place identity [

3]. Cultural architectural heritage has been the subject of interdisciplinary reflection at the boundaries of various academic disciplines, as evidenced by the collective study “Cities’ Identity Through Architecture and Arts”, the aftermath of a conference in which architecture and the arts were discussed as factors influencing urban identity [

4].

Urban revitalization and architectural heritage is an important task for local and regional authorities. The range of activities in this area includes many issues, problems and proposals for solutions [

5]. Also related to architectural heritage is the branding of the city, widely described by researchers such as Beatriz Casais and Patrícia Monteiro [

6]. Often, city-building involves integrating the historic urban fabric into the process of shaping a sustainable city [

7] A considerable number of researchers have considered the above issues using examples of specific cities, or comparing activities in several centers. An interesting study of architecture as a factor in city identification using Barcelona and Boston as examples was conducted by Candace Jones and Silviya Svejenova [

8]. The issue of typological studies in the aspect of revitalization of traditional architecture in Alentejo, Portugal was addressed by Anna Rosado and Miguel Reimão Costa [

9]. Few researchers have been involved in the study of the issue of residential architecture as a factor that can shape the cityscape and be a distinguishing feature of the city. An example of such a study is the one devoted to Herat City [

10].

All the studies, dealing with different aspects of architectural heritage, allowed a broad view of the heritage issues of the centres selected for the research, their characteristic landscape and ways of revitalisation.

The literature on the centres selected for consideration and the typology of residential architecture, its construction and decoration also had a significant place in the research. Of the many studies on framework architecture, it is worth citing the one devoted also to Alsfeld [

11]. An important position on timber frame architecture in various aspects is the collection of studies Gebäude aus Fachwerk Konstruktion – Schäden – Instandsetzung [

12].

The second centre chosen for detailed research is Segovia, with its buildings covered in sgraffito. Many studies have been produced on the history of this decorative technique, for example the work of Alonso Ruis [

13,

14]. There has also been a great deal of research on the historic architecture of Segovia and its unique facade decoration [

15,

16,

17,

18]. It is necessary to mention the most important studies by the Segovia sgraffito expert Alonzo Ruiz [

19,

20,

21].

Another city chosen as a case study is Porto. The traditional architecture of the centre and the problems of revitalisation have been studied by, among others Hugo Santos, Paulo Valença and Eduardo Oliveira Fernandes [

22] and Joaquim Teixeira, Rui Fernandes Póvoas [

23]. Problemami efektywności energetycznej budynków w Porto zajął się Joaquim Flores [

24].

The last resort investigated is the seaside resort of Binz, which has not received numerous studies. Spa architecture was the subject of a book on Barbara Finke i Beatrice Pipia “Landhäuser & Villen am Meer - Rügen und Hiddensee”. Binz architecture is mentioned in an article by Joanna Arlet on the development of resort buildings in Pomerania [

25]. Use of wood in the Baltic architecture on the example of Binz in Rug are described in the article “Use of wood in the Baltic courses architecture on the example of Binz in Ruges” [

26].

A number of conservation studies and reports and municipal or regional documents and ordinances, as well as municipal and private websites and the local press, were very important for the research carried out.

1.3. The Value of Unique, Residential Architectural Ensembles in the Modern World

The need to revitalise places with peculiar features, unique architecture, bringing them up to modern standards and imparting skills and training in traditional building trades seems obvious. However, in an age of globalisation, of separating people by being locked into virtual reality, the space around us is becoming more and more homogenised, and historic buildings, especially residential ones, which are often not considered particularly valuable are deteriorating, being demolished or losing their historic value. Modern residential architecture is rarely an identifier of place, especially in smaller, provincial towns. Residential neighbourhoods built in the 20th or 21st century, regardless of the region, are similar to each other and do not have their own distinct identity. Therefore, the study of places where this identity exists, where a kind of genius loci is present, is necessary for the preservation of the traditions and ’roots’ of local communities, the diversity of the architectural landscape and sustainable development.

Investigating the factors and activities that favour the preservation of local identity, the historical context of places where it is preserved and the methods by which a balance between tradition and modernity is achieved is still relevant. Identifying good models, including in relation to the revitalisation of sequences of locally distinctive housing, helps in efforts to care for architectural heritage. Such studies also show the various opportunities that caring for the cultural architectural heritage offers for local communities such as improved housing conditions, tourism development and the creation of new jobs, improved communication and others. Also valuable are examples of the restoration of intangible heritage in the form of training of craftsmen and the operation of companies using traditional techniques. In addition, showing the joint activities of local communities in the field of revitalisation, developing their creativity and satisfaction with the great results achieved, can be an incentive for similar activities in other places. And yet, there is still much to be done in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

Urban centres with diverse functions, geographic locations, strongly distinctive local, traditional residential architectural features characterising the urban landscape, and in which various revitalisation activities were taking place, were selected for the study. These included the German cities of Alsfeld and Binz, the Spanish city of Segovia and the Portuguese city of Porto. The cities were analysed visually and contextually in terms of their history, building traditions and the specifics of the revitalisation measures undertaken. In addition, through a nomothetic analysis, it was possible to determine which steps contributed to the successes achieved.

Analysis of the case study

2.1. Alsfeld - Half-Timbered European Model City

The small town of Alsfeld, located in Hesse, is regarded as a model town with half-timbered buildings. The bourgeois timber-framed houses dominate the town’s landscape, building up its identity. This technique is a traditional way of building in Hessen, but the number of preserved buildings, almost entirely filling the streets of Alsfeld, sets the town apart. Thanks to a building tradition that has been preserved for centuries, it is possible to trace the development of timber construction here from the late Middle Ages to the 19th century [

27].

Figure 1

The residential buildings in Alsfeld are consistent not only because of the cultivated technique, but also because of the similar building dimensions and roof forms. On the other hand, the individual buildings are distinguished by the colour scheme used, with the dominant vivid or muted colours of the wooden elements. In addition, many woodcarving decorations have been preserved on the facades of the houses, ranging from friezes of various forms, columns and sculptures of great artistic value. There are acanthus leaves, pearl and string ornament, decorations with floral and animal motifs. On the pile caps of many houses, inscriptions can be found, usually indicating who built the building or lived in it and when.

Figure 2 On one of the most interesting houses, belonging to the master baker Jost Stumpf (Markt 6, erected in 1609), an inscription reads: "This is the richest decorated house in Alsfeld". The house is indeed still distinguished today by its rich decoration with carved corner posts with figures representing a man, naked women and the owner himself in elegant period dress.

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 The storeys were separated by string friezes and all wooden elements were kept in red, green and yellow. The colourful townhouses create a unique character for the city’s buildings, its identity, which demonstrates the cultural value of the architectural heritage as well as influencing social and economic development.

Alsfeld, whose history dates back to the turn of the 8th and 9th centuries, was already a significant urban centre in the 13th century, located at the crossroads of trade routes. In the following century, the town began to develop as a centre for cloth production and trade. The golden age of Alsfeld came in the 16th century. At that time, many burgher houses were built, in timber-frame construction, many of which still survive today. The development of the town came to an end with the 30-year war and the destruction it brought with it. The town lost its importance, the population decreased by more than half, bringing an end to its development and a crisis that lasted almost until the end of the 19th century. Some revival only came after the railway line was brought in in 1870. Paradoxically, the delayed industrialisation of the town resulted in the architecture and urban layout being preserved in their historic form from the heyday [

28,

29].

Today, there are around 400 half-timbered houses in Alsfeld, built between the 14th and 19th centuries. Prominent among them is the town hall building, with its stone ground floor and timber-framed superstructure, considered one of the most important half-timbered buildings in south-west Germany. However, the characteristic townscape is formed by rows of timber-framed townhouses [

27].

Figure 5 In addition to its building tradition, Alsfeld boasts a pioneering tradition of historic preservation, dating back to 1878. It was then that the town councillors decided to demolish the town hall, but a protest by the citizens’ committee and the district council prevented this. This is noteworthy because in the 19th century, the demolition of old buildings was common, and in Alsfeld it provoked sharp criticism. The next step was the enactment of the local building statute (Ortsbau-Statut) in 1900, which was supplemented two years later by the Protection of Monuments Act. The beginning of the 20th century saw an upturn in the town’s fortunes, at which time many of the town’s institutions were erected, and half-timbered houses were renovated and their structure exposed [

27]. This resulted, among other things, in a great interest in the city among tourists. In 1938, a motorway was built running around the town, with two exits, facilitating access from other regions. The town did not suffer significant damage during the Second World War, and work continued after 1945 to protect the monuments. Between 1947 and 1974, 57 half-timbered houses were uncovered and 65 were restored. In 1963, councillors passed a new town charter which stated: "The historic centre of the district town of Alsfeld is a magnificent monument of medieval and Renaissance architecture, which has happily survived to the present day. The preservation and maintenance of the old townscape is therefore a special duty of the municipal authorities." This year also saw the establishment of local regulations for the preservation of the historic city centre, which were exemplary for Hesse at the time. In 1967, a framework urban development plan was drawn up with the aim of maintaining the old town as a centre for business, administration and culture. It also included provisions relating to the modernisation of the housing stock. Further local regulations for the preservation of the facades and buildings that characterise the townscape were introduced in 1978. Restrictions were introduced on advertising, shop fronts, window and door design, facades, the use of plasterwork, etc. However, these were implemented to a very limited extent [

27]. Thanks to these efforts, in 1973 Alsfeld was selected by the Council of Europe for a ‘pilot programme for the preservation of monuments worthy of protection’. Within the framework of the ‘Future for our Past’ campaign, Alsfeld, as one of 51 cities, served as a special example of European cultural heritage and exemplary conservation policy. As a result, Alsfeld has held the title of ‘European Model City for Historic Preservation’ since 1975, which has helped the city to become internationally recognised [

30].

Unfortunately, further conservation efforts have not always been appropriate. Funding for historic preservation, as well as the funding programme set up by the city in subsequent years, focused on the renovation of the building envelope such as roofs, windows and the restoration of timber framing. As a consequence, many buildings have suffered from massive encroachments to enlarge shop areas and exhibition areas, and renovations have been abandoned in many, leading to structural damage to the buildings.

Efforts to protect the historic centre of Alsfeld were not resumed until 2016. Based on previous experiences, this time an integrated urban development concept was created, taking into account very broad measures in the cultural, social and economic fields. The city was analysed as a whole on different levels such as general infrastructure, demography, social policy, trade, communication, etc. Major renovation needs for historic townhouses were identified. All interested groups were involved in the work: residents, local stakeholders, municipal employees and the department of monument protection. Meetings and presentations were held, well received by the local community, and all information was posted on the city’s website. The result was the construction of a modern urban regeneration plan, providing an impetus not only for the renovation of the historic building fabric, but also for the development and strengthening of the old town as a residential and commercial location. Care was taken to surround the historic centre, promote tourism and infrastructure for the local community, as well as education and guidance on the restoration of traditional timber-frame houses. Different funding modules were created to suit the varied needs of renovation [

11,

31]. The measures implemented and continued have produced very good and lasting results, affecting both the state of the cultural heritage, the identity of the place and the coherent and sustainable image of the city [

32].

Alsfeld is a unique example of a city where historic preservation has a long tradition. Looking back, not all measures were successful, but lessons were learned and mistakes were not repeated. Thanks to the implementation of a new, broad and interdisciplinary programme for the preservation of the historic centre, which includes measures that go far beyond the protection of monuments in the strict sense of the term, Alsfeld today impresses with homogenous, beautifully maintained buildings that create a unique townscape.

2.2. Segovia - the Sgraffito Tradition - Diversity in Unity

The historic centre of Segovia is distinguished by the unique ‘lace’ design of its building facades. This impression was given by covering the façades with geometric, artistic sgraffito. Eminent Segovia sgraffito expert Rafael Ruiz called it ‘la piel de Segovia’ - the skin of Segovia [

33] - highlighting the widespread use of this technique and its influence on the cityscape. It is a good example of an ever-living tradition, influencing considerable architectural integrity and stemming from the city’s interesting multicultural history.

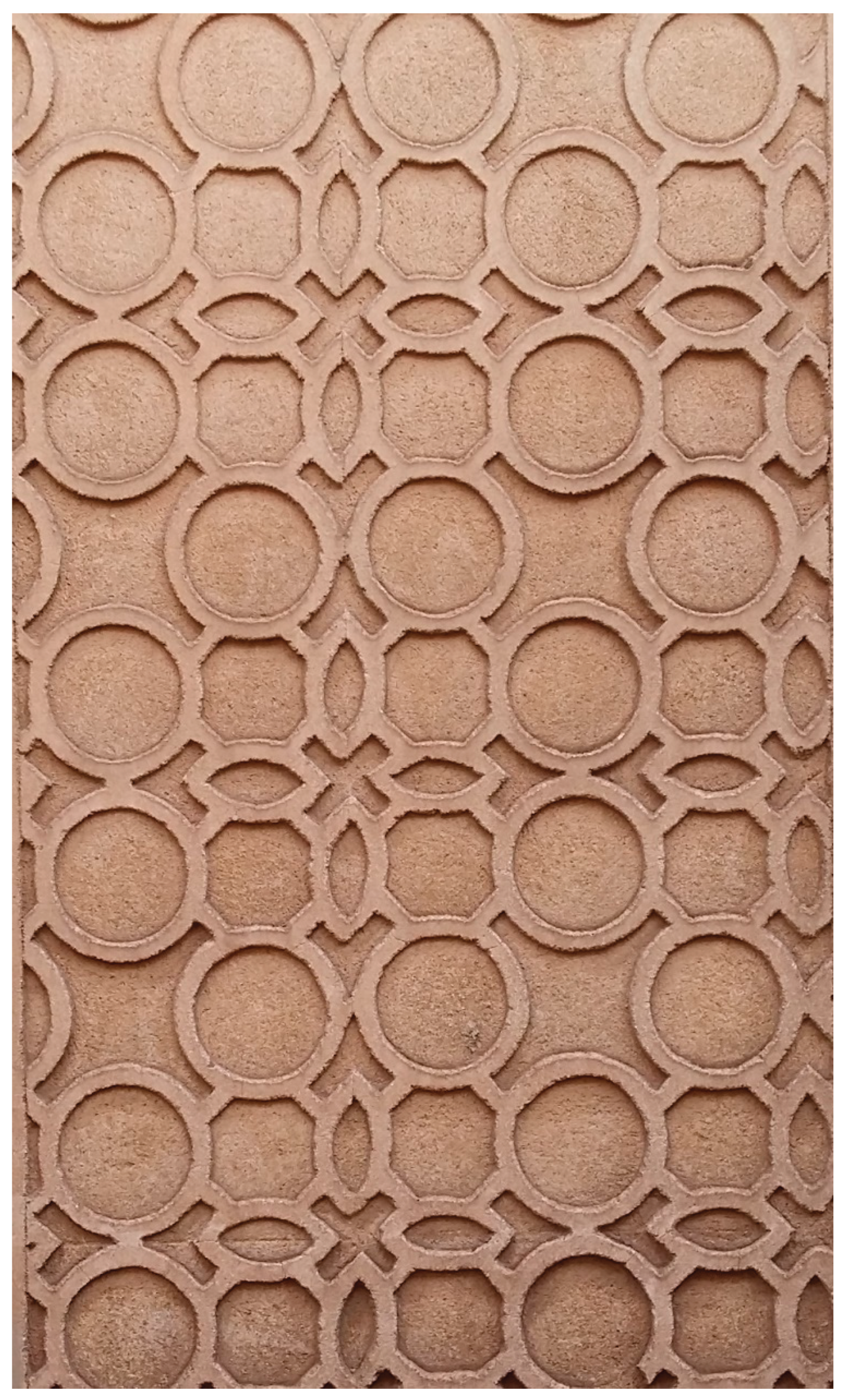

Figure 6

The sgraffito technique has been known since antiquity and used in many countries. Segovia is distinguished by the continuity of the tradition of decorating buildings with this technique

1 and its numerous applications on the facades of buildings filling the streets and squares of the city. In addition, Segovia’s characteristic use of geometric, ’lacy’ combinations of patterns and their variation determines the uniqueness of the cityscape.

The tradition of using sgraffito in Segovia dates back to the 15th century

Figure 7, and in the following years it was continued, developed and adapted to current needs. In this way, sgraffito became an element that gave coherence to Segovia architecture, influencing the unification of the facades of buildings built in different constructions and different historical periods. The "Segovia plaster" was written about in 1909. Francisco de Alcántara: "….although it is not exclusive to Segovia, here one can find most of the old specimens and it is still used as a durable finish capable of accepting different decorations.

Analysing the forms of decoration found on the facades of residential buildings, one can observe their evolution, from irregular shapes reminiscent of a drop of water to circles and their fragments, variously positioned among each other, other geometrical figures, stylised floral forms - tendrils, rosettes, fish scales. From these initial simple models, a great many sgraffito sequences were created by enriching and differentiating the motifs. In Segovia alone, 169 different models were found, and as many as 664 in the whole province [

18]. The most numerous group is sgraffito with geometric ornaments, which were made with stencils in the 19th and 20th centuries. By varying the juxtaposition of figures, reversing the positioning of the stencils in a continuous series, alternating, according to horizontal or vertical symmetry, or using different arrangements of figures, a lot of heterogeneous combinations were gained.

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10

Differences can also be seen in the layout of the sgraffito decoration on the facades of individual buildings. Whole facades or selected parts were covered, usually from the second storey upwards, leaving the ground floor area plain. The richer solutions had separate borders around the window openings, other models were used on each storey, and sometimes the storeys and corners were separated by separate strips. Another important factor was the depth of the relief, affecting the chiaroscuro and plasticity of the façade. Here, too, the individual developments differed from one another. A similar role was played by the colour contrast of the individual plaster layers, which also differentiated the buildings. The variety of Segovinian sgraffito was also influenced by the use of different technical variants such as embossed and scratched sgraffito, consisting of two or more layers, made with different materials and with different tools. Finally, different stencils were used, for example, made of metal or stone [

19]. The variety of effects produced by the use of different sgraffito techniques in Segovia makes the seemingly unified facades of the buildings significantly different, resulting in a very interesting and unprecedented solution in terms of the entire city center.

The origins of Segovia are linked to a Celtic settlement that was conquered by the Romans in 80 BC

2. The subsequent history of the town was linked to the Visigoths and Moors, who left their mark on the local culture. In 1079, conquered by King Alfonso VI, Segovia became a Christian city again. Segovia, until the end of the 16th century, prospered, getting rich from the wool trade and the production of woollen flannel. In the following century, after the plague epidemic, there was a period of significant depopulation of the city and economic decline. It was not until the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century that there was a period of economic and demographic recovery. The periods of economic prosperity and decline were closely linked to the architectural development of the town and the quality of the buildings erected, as well as the use of sgraffito.

The original forms of sgraffito in Segovia are linked to decoration discovered on the wall of a 12th century castle and other buildings of the period [

19]. The 15th century was probably the period when the ’first sgraffito’ begins to separate from the stone base and use forms similar to Gothic tracery such as drops or ’fish bladders’. This type of decoration is preserved in the patio and tower of the Casa de los Picos [

19]. Further development of the technique in the 15th and 16th centuries led to the use of repetitive, regular motifs distributed throughout the facades. The similarity of forms and the few surviving Islamic sgraffito may indicate the influence of Islamic art [

15,

20].

The 17th century saw a slump in the town’s economy, which was associated with a decline in the technical level of private construction and the use of cheap, perishable materials. This resulted in the destruction of masonry and a gradual deterioration of the appearance of the buildings [

18]. The issue of tidying up the buildings and repairing the facades was only raised at a session of the Town Council in 1856 [

36]. Among the facades renovated in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, those covered with sgraffito were the best. They were often combined with stucco or painted elements. Stencils were most often used and the decoration was placed over the entire façade.

Today, sgraffito in Segovia is a technique that has fallen out of favour, but it is still used in the restoration of old buildings and some modern constructions that try to preserve the traditional style of the region.

Figure 11 Most of the historic buildings have been catalogued as part of the valorisation of the historic part of Segovia in a multi-volume catalogue, part of a report on the environmental sustainability of cities [

37]. With a view to preserving this traditional craft, in 1985 the specialisation "Mural techniques and procedures" was opened at the School of Applied Arts and Artistic Professions in Segovia (Escuela de Artes Aplicadas y Oficios Artísticon de Segovia), in which the sgraffito technique is an essential part of the curriculum [

38]. The college trains staff for the restoration of historic sgraffito, but students also undertake their own creative work. Various initiatives such as conferences and workshops promoting the technique are undertaken at the school. A collaboration with IES Andrés Laguna High School resulted in the design and realisation of a sgraffito on the school’s wall [

39]. Art school students designed and created a sgraffito in the building of the Dirección Provincial de Educación de Segovia [

40]. Thanks to the collaboration with the Segovia City Council and the Provincial Department of Education, another modern sgraffito located in the city centre, on the wall at the foot of the statue of San Juan de la Cruz, was created in 2022, allowing a degraded space to be cleaned up. The author was art school student María Martín Requero [

41].

A new and unusual application of sgraffito was demonstrated by the master of this technique, Julio Barbero at the 3rd International Congress of Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism: Timeless Architecture 2022. The artist demonstrated a QR code made in the sgraffito technique, which can be placed on façades, combining tradition and modernity to tell the story of a building or city. During the demonstration, participants could hear after scanning the code with their phones: "Hello friends. I am a Segovian sgraffito of the latest generation. I am a work that combines Segovia’s traditional past with the technological present, and because of the natural durability of this type of plaster, it will still be there for new generations to enjoy in over 100 years’ time. I am sure that when I am an old man, I will be protected by my heritage as a unique element of our facades." [

42].

Sgraffito in Segovia, present for centuries in the architectural culture of the city, has become an authentic part of its identity and meets the criteria of a unique cultural heritage. This way of decorating buildings, with such intensity and variety of patterns, can only be found in Segovia. Through its original form and its very numerous applications on the façades of a large part of the buildings of the city centre, it is a striking element and associated with Segovia, and is therefore undoubtedly its distinctive feature. Moreover, thanks to the activities of the city authorities, the education of young people, the work of masters of this craft and imaginative initiatives to promote this durable and beautiful technique of façade decoration, sgraffito will form the architectural landscape of the city for centuries to come.

2.3. Porto - the Magic of Historic Windows

The urban fabric of Porto’s historic centre and its many historic buildings are a remarkable testimony to the city’s development over the last thousand years. There are many valuable religious and public buildings in this area, but the distinguishing factor in the streets and squares that make up Porto’s urban landscape is the unique tenement buildings, with facades with numerous window openings. The windows of the historic city centre, with window joinery of fancy divisions, occupy the greater part of the surface area of the facades in the typical small townhouses and contribute to the uniqueness of Porto’s residential architecture.

Figure 12

The series of buildings filling the frontages of the streets and squares, thanks to the considerable glazing of the facades and the unique window joinery, give the impression of a delicate cut-out in the framework of the external walls. The glazing reflects the light beautifully, giving an impression of lightness, further emphasised by the lack of architectural decoration. This highly original, unique window joinery is what makes the facades of Porto’s townhouses unique and the intensity of its occurrence creates a unique townscape. Facades filled with windows with a variety of intricate divisions or divided by a dense grid of small quarters take on a lightness that creates the impression of ’lace paintings’ for the viewer. The convex muntin and the sculptural decorated transom bars add chiaroscuro to the facade plane. This is complemented by the metalwork of the balcony balustrades and the infill of the under-window areas.

Figure 13

Porto is a city with a long history dating back to the 5th century and a long building tradition. Traditional residential buildings in the city have always been characterised by modest façade solutions and a lack of lavish decoration. The oldest type, corresponding to medieval traditions, are buildings with simple facades without balconies. From the 17th century onwards, light wooden structures were replaced by granite in the front walls and balconies were introduced. The layout of the facades did not show major changes over the centuries, which was due to an established, permanent typological matrix. The composition of the facades mainly consisted of the arrangement of openings, which occupied most of the surface area [

23].

The modest façades of 17th-century houses were enhanced in the following century with more varied window woodwork, with curved lines towards the end of the century. In the second half of the 19th century, larger houses were built, with richer stucco decoration. Huge, representative townhouses appeared at the turn of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century. The buildings were covered with rich architectural detailing, in keeping with the fashion of the time, and traditional windows and forms of woodwork were replaced by double-hung windows with large glass panes. However, the Porto-specific forms of window joinery with multiple divisions and curved lines can also be found here. Relatively small buildings with 3-axis facades account for 78% of the total number of residential buildings [

24]. Most of the window frames were made of pine, then painted. The windows were glazed with single panes of glass between 3 and 5mm thick. The same wood was used to make the internal shutters that were originally used in all houses. They served, and still serve, at the same time to provide security, privacy, light and temperature control [

24].

Window openings, where sliding windows were assembled, had a shape of a standing rectangle with proportions close to 1:2 or a little bit wider and they were placed in granite frames. They were most often filled with thick net of tiny, rectangular panes divided with muntin bars. They appeared in two varieties with different sizes of pane’s area.

Figure 14

Double-leaf windows were framed with stone bands, most often straight ones, however, in later buildings profiled bands were used closed with a part of arch or prominent, profiled section of the cornice, often additionally decorated with, for example, keystones. Usually window sashes were divided into 4 equal panes. The mostly decorated part was upper sash separated with richly ornamented transom bar. Transom was usually in the shape of a semi-circle or its part or a rectangle. There were also transoms closed with a sharp arch. Fields of transom were divided with muntin bars in the shape of parts of arches running from the middle upward to the sides creating three panes, sometimes, a spacer in the form of a full arch was added. There are also wing divisions into small rectangular quarters.

Rails and cover strips were enriched with carving decoration with different images. The most frequent images included acanthus leaves referring to antique ornaments, kimations, tooth or pearl ornaments. What is more, different plant images were introduced, twisted spiral columns, rosettes, interwoven lines referring to Manueline decorations, fan forms and many others. In windows with transom closed with a sharp arch divisions with parts of arch into smaller ones were applied.

Due to introduction of balconies in numerous buildings the most frequent form of window was French window, preceded by decorative openwork balustrades. Double-leaf French window was horizontally divided with muntin into 2, 3, or 4 stripes of double quarters or they were glazed with so called, big glass. Under the glazing, at the bottom, there were full wooden panels, smooth ones or with carving decoration with plant images placed in medallions.

Figure 15.

Porto, example of French window with rich decoration of window joinery from the historic center of Porto.

Figure 15.

Porto, example of French window with rich decoration of window joinery from the historic center of Porto.

The historic centre of Oporto was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996 and covers an area of around 50 hectares, with a population of around 13,000 inhabitants spread over 1,796 buildings

3. Although it has been subject to conservation efforts since 1974, when the CRUARB (Commissariat for the Urban Renewal of the Ribeira and Barredo Areas) was set up, very little has been achieved. Neither have the various incentives created by the central government been able to halt the process of destruction that has been progressing as a result of neglect, fuelled by the freezing of rents by a 1950 law [

23].

Although the historic centre of Oporto was declared a National Monument in 2001, in addition additional protective instruments such as the 2006 Resolution of the Council of Ministers and the 2008 Regulatory Code of the Porto City Council were enacted, the improvement of housing has been slow. The City Council created a special Urban Area Management Unit.

A survey carried out in 2005 by the newly created Porto Vivo urban regeneration association showed that only 4 per cent of buildings in the old city centre were in a reasonable state of preservation; 50 per cent were in poor condition and a further 46 per cent required ’profound intervention’. According to the 2008 Management Plan for the Historic Centre, the state of preservation of the buildings was as follows: 25 per cent good, 36 per cent medium, 32 per cent poor and 4 per cent dilapidated, with the remaining 4 per cent in the process of being worked on. However, it was only with the passing of the Rent Act in 2012 - a law that allowed rents to be raised and tenants to be terminated - that the interest of investors and property owners really improved. Renovation work slowly took off and the property trade began to move. Porto Vivo data from 2013 confirms the positive developments, showing that 69 per cent of the building stock in the area is now in good condition, with only 3 per cent still in need of deep intervention [

43]. The old town is bustling with activity, with numerous building projects under construction and new restaurants, shops and bars opening every month.

A large proportion of the buildings in the historic centre, which are small townhouses, are in private hands. The remainder is owned by the state, the city, the church and other organisations, including the Porto Vivo SRU (Sociedade de Reabilitação Urbana da Baixa Portuense, S.A.). The World Heritage Management Plan for Porto’s historic centre includes a study of the state of preservation, the creation and implementation of a revitalisation action plan and a programme for their monitoring. Due to the complexity of implementing such a management plan, a special Urban Area Management Unit has been created, responsible for solving the current problems in the Historic Centre of Porto, the aforementioned Porto Vivo, SRU: Sociedade de Reabilitação Urbana da Baixa Portuense, S.A. A new city brand was created in September 2014. Beatriz Casais and Patrícia Monteiro carried out a survey of residents’ involvement in the creation of the city logo and their views on related City Council activities. It emerged that residents would have liked to have had more input into this work, and that the strategy created was aimed more at attracting tourists than strengthening residents’ attachment to the city [

6].

The result of all the above-mentioned activities - legislation, the regeneration plan and the efforts of the local authorities and community - is a beautiful historic centre, rich in buildings of high historic and cultural value. Preserving the original window frames or making identical copies of them, introducing elements that improve thermal efficiency in a way that does not compromise the harmony and stylistic qualities of the front facades is noteworthy and commendable here.

Figure 16. It allows for the preservation of building traditions and the survival of distinctive elements of residential architecture, thus preserving the cultural heritage and unique landscape of the city. However, maintaining the unique, universal value of the area in the long term will require planned and thoughtful management and increased public participation. The historic windows are very important part of a historic buildings, unfortunately underestimated in residential architecture all the time A very large proportion of historic window joinery is deteriorating and is often replaced, with mass-produced windows of other materials. Porto is an example of a city where attention to detail such as historic windows has translated into a beautiful, unique cityscape. The process of revitalisation here has been a long one and is not yet complete, but the effects are already visible in much of the oldest neighbourhoods.

2.4. Binz - Wooden Verandas and Fretworks

Binz is the largest seaside resort city on the island of Rügen and is a well-preserved example of a "white town" with lots of wooden architectural details and decoration, giving the whole place its individual character. Wide, wooden verandas, balconies or loggias became a dominant element on the facades of the villas and guest houses. They were arranged in very different configurations, often spanning the entire width of the façade as well as side elevation, sometimes placed between the avant-corpses or on either side of them. Most form risers of several storeys, covered by a separate roof in the last storey. The frame structure of the verandas was based on posts and beams forming the frame of the veranda, supported between storeys by the lasts of the ceiling beams. The woodcarving decoration was placed on swords and braces. Between these elements, as well as in the under-window areas and above the javelins, lace-cut panels were placed. The wooden elements were painted in light colours, usually white [

26].

Figure 17 and

Figure 18a,b

Made of wood, balconies, loggias, verandas, gables, half-timbered constructions of the upper parts of buildings or whole storeys, combined with various architectural elements, referring to different stylistic formations, create a perfect conglomerate of forms, matching each other and the surrounding nature despite their great diversity. With similar building dimensions, the use of wood and woodcarving decoration, and the unification of the buildings through the use of white, which dominates the facades, it makes the street frontages look harmonious, and the timber fretwork ornaments give them an unreality that allows a break from reality and encourages relaxation. Together with a few accents in the form of a few villas with different forms and the spa house to prevent fatigue and add expression, the whole resort development creates a unique townscape, further emphasised by the blue of the sea along which the main promenade extends.

Figure 19 and

Figure 20

Binz, like most seaside resorts, does not have a long history. Until the middle of the 19th century it was a small village of 149 inhabitants. In the second half of the 19th century, with the development of tourism and the fashion for trips to the bathing resorts, summer visitors began to flock to Binz. Consequently, the village cottages were extended by enlarging attics and adding wooden verandas and porches. In 1876 the first hotel was built, followed by new buildings along the Strandpromenade, which ran along the beach. The first hotel right on the beach - the Strandhotel - was built in 1880 by Wilhelm Klünder. The greatest building boom occurred between 1890 and 1910 [

44].

The villas and guesthouses built at the time, with rooms for summer visitors, were given the fashionable forms of resort architecture that was emerging at the time. Due to the growing popularity of outdoor recreation and its importance for the health of the human organism, the facades of the buildings featured rows of wooden verandas, loggias and balconies, which were a characteristic feature of the architecture of the holiday resorts. Most of the buildings in Binz had a simple body, enriched beyond the verticals of the verandas with avant-corpses, bay windows, attics and turrets, which gave them a lightness and a specific character [

25].

After the Second World War, refugees from destroyed towns came to Binz, which did not suffer from warfare. The buildings were adapted for year-round use and the originally open verandas were built over, which was left to the renovations carried out from 2022 onwards.

In 1953, Binz, which was on the territory of the former DDR, was hit by the "Aktion Rose". Hotels and guesthouses in the seaside resorts on the Baltic coast, especially on Rügen, were nationalised and more than 400 entrepreneurs were imprisoned for alleged offences against the ’Protection of Public Property and Other Social Property Act’ (VESchG) [

45]. In the 1970s, a prefabricated housing estate was built nearby, but it did not obscure the silhouette of the town [

46].

German reunification in 1990 opened up new opportunities. Many of the nationalised villas and guesthouses were returned to their former owners. The following years became a period of renovation and reconstruction. Many new buildings were also constructed, both on the outskirts and in the centre of the village. Streets and pavements were repaired and the seafront promenade was extended, and a new pier was opened in 1994, replacing the one destroyed during the war. Further work to clean up and enrich the infrastructure of Binz was carried out after 2000, including the opening of the spa park [

46]. A brilliantly fitting modern touch is the Rescue Tower, one of 50 shell structures created by Ulrich Müther. The oval white ’tower’ with its panoramic windows is a great contrast to the greenery and traditional architecture of the resort. The tower serves a variety of functions from the Binz registry office to a small concert hall [

47].

Of great importance for the preservation of the cultural heritage of the resort was the "Regulation on the monuments of the Hauptstraße / Strandpromende Putbuser Straße and Bahnhofstraße in the Baltic resort of Binz" issued by the district administrator of K. Kassner and published on 10 June 2002 [

48].The ordinance concerned the protection of the urban layout and the appearance of structures and constructions in the said area, which is a historic part of the locality. It emphasised the need to preserve as much of the original historical substance as possible, to preserve the urban layout, the layout of the courtyards-gardens and buildings, as well as the silhouettes of the buildings and their dimensions. The document emphasises that "the alignment of historic buildings, together with natural conditions, leads to spatial forms that are interrelated in ways that can be experienced through visual relationships. The sea has a particular influence on the shaping of space". Importantly, the regulation enshrines the protection not only of the urban layout of streets and squares, but also of the traditional structure of the plot with its development. The importance of the architectural, structural and decorative elements of the historic buildings, which are representative of Binz’s architectural heritage, is also emphasised. The silhouette of the locality visible from the water and from the pier was also protected. With the entry into force of the aforementioned ordinance, the listed historic area became subject to the provisions of the Historic Preservation Act, which entailed the control of any work carried out in the historic centre.

Arguably, the ordinance has had a huge impact on preserving or restoring the coherence and uniqueness of the town’s landscape, preserving its silhouette undisturbed by the multi-storey hotels, in some localities erected almost on the beaches and destroying not only the cultural architectural heritage but also the entire environment. The local community can be proud of the result, and this is underlined by a gallery of photographs of Binz from the DDR period set up on the promenade, showing dilapidated boarding houses and villas, next to which the renovated originals can be seen. Today, the town impresses with its beautifully restored and harmonised buildings, with openwork panels with fretwork decoration, blending beautifully with the coastal landscape. The architects of the early 20th century intended the loggias and verandas of the pensions and hotels in Binz to be an extension of the room, a kind of link to the surrounding nature. While resting comfortably on a deckchair, one could take in the fresh air. They were also the equivalent of theatre lodges, where the stage was the promenade with a "performance" played by strolling holidaymakers against a backdrop of sea and dune vegetation as "theatrical decoration". On the other hand, the buildings, viewed from the beach, pier or sea, were the calling card of the resort and were meant to catch the eye of potential visitors. And it is this unique landscape of Binz that has been preserved, a tangible and intangible heritage at the same time. Despite the great variety of forms, enriched by rows of verandas, loggias or balconies, the houses still look very coherent and harmonious, retaining their individual charm.

3. Results and Discussion

The analysis of the case studies has shown that the traditional, unique and well-preserved residential architecture filling the streets and squares of the towns builds the townscape and its specific genius loci. In spite of the separate building traditions, the different forms of decoration or architectural elements used, the different size, function and history of the centres surveyed, the compact and harmonious street frontages filled with townhouses or guest houses, as in the case of Binz, give the towns their unique character. At the same time, the variety of patterns, colours or other details in a given place ensures that the architecture is not boring and that each townhouse or tenement stands out from its neighbour. As a result, the overall impression is one of uniformity and, on closer inspection, diversity.

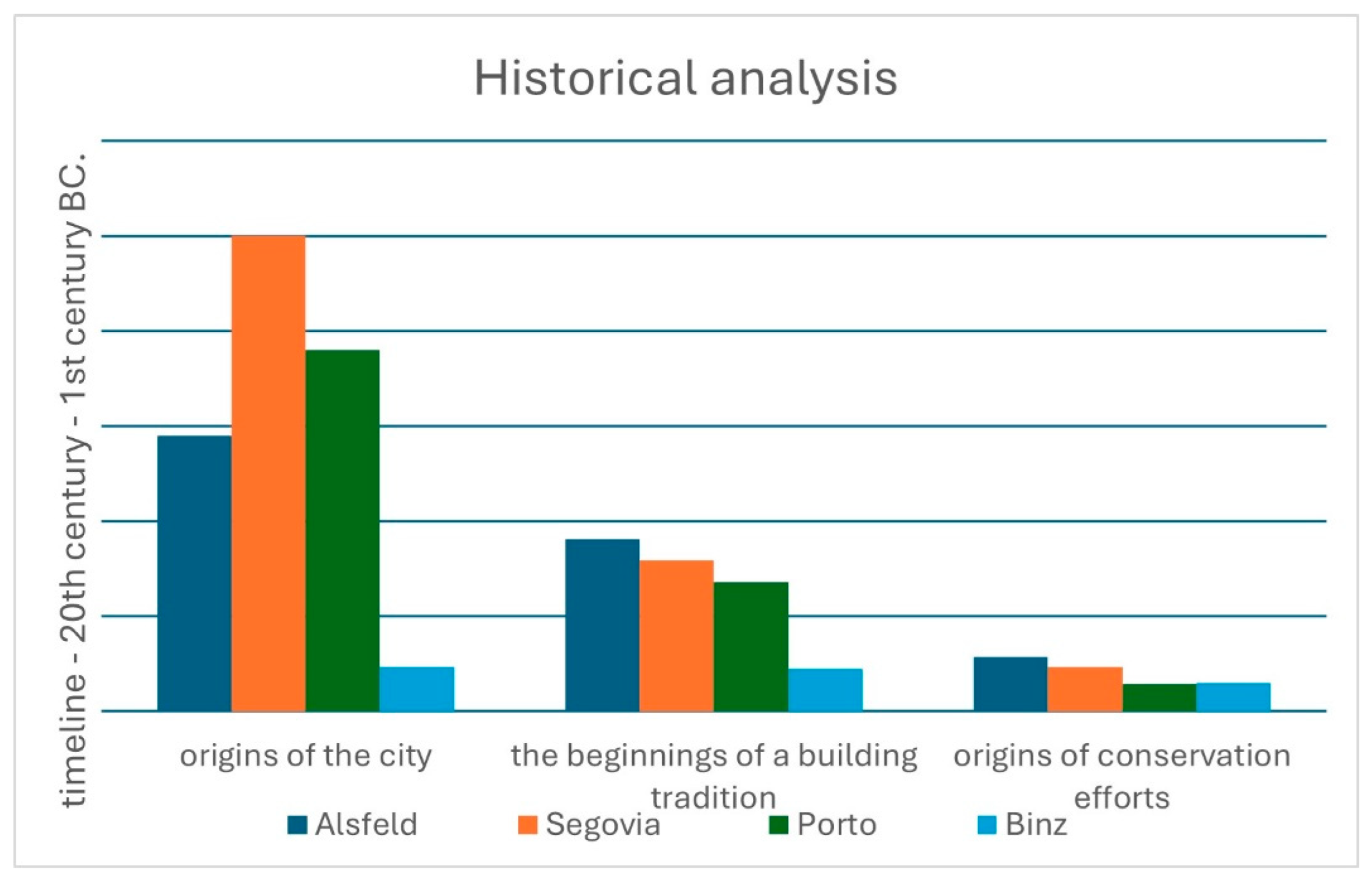

Each of the case studies included brief analyses of the histories of the selected centres, which demonstrated their diversity in terms of both the origins of the towns, the beginnings of their traditional residential architecture and their interest in historic preservation, including unique features of local architecture. The juxtaposition of these data on a timeline is included in the chart below.

Figure 21.

Historical analysis.

Figure 21.

Historical analysis.

The study showed that the residential architecture of both cities with a very long history, as in the case of Segovia, and those existing for only just over 100 years, such as Binz, can be an element that builds the identity and landscape of a city and influences its sustainability.

The residents’ respect for architectural monuments and the undertaking of conservation measures have been important in keeping the townhouses in good condition. Among the centres surveyed, Alsfeld has the longest tradition of historic preservation, where work in this field has been going on for more than 200 years. The long period of action and learning from mistakes has meant that this city has gathered the most experience in this field, which has led to very good results. The history of the revitalisation of Alsfeld can serve as an example to other centres of good actions, but also of mistakes made, which can protect other cities from them. However, the example of Binz, whose revitalisation started relatively recently, shows that it was possible to recreate the unique architectural character of the resort in spite of much destruction. Examples of the most important historic preservation measures in the surveyed centres are shown in

Table 1.

The analysis of the studies of the selected cities showed how important it is for the search for place identity to find the identifiers of the cityscape and to act consistently in the field of their authentication, conservation and visual highlighting against the background of urban architecture. In each of the cities studied in the group of residential buildings, other factors accounted for their uniqueness. The most important characteristics of each centre’s identifiers are summarised in

Table 2.

In two of the centres, the buildings identifying the city dominated the streets and squares, in the other two it was the predominant element in the development, but this was also sufficient to create identity and genius loci. In all centres, the homogeneity of the buildings was enriched by distinctive elements, which greatly enriched the architectural expression of the cities (

Table 2).

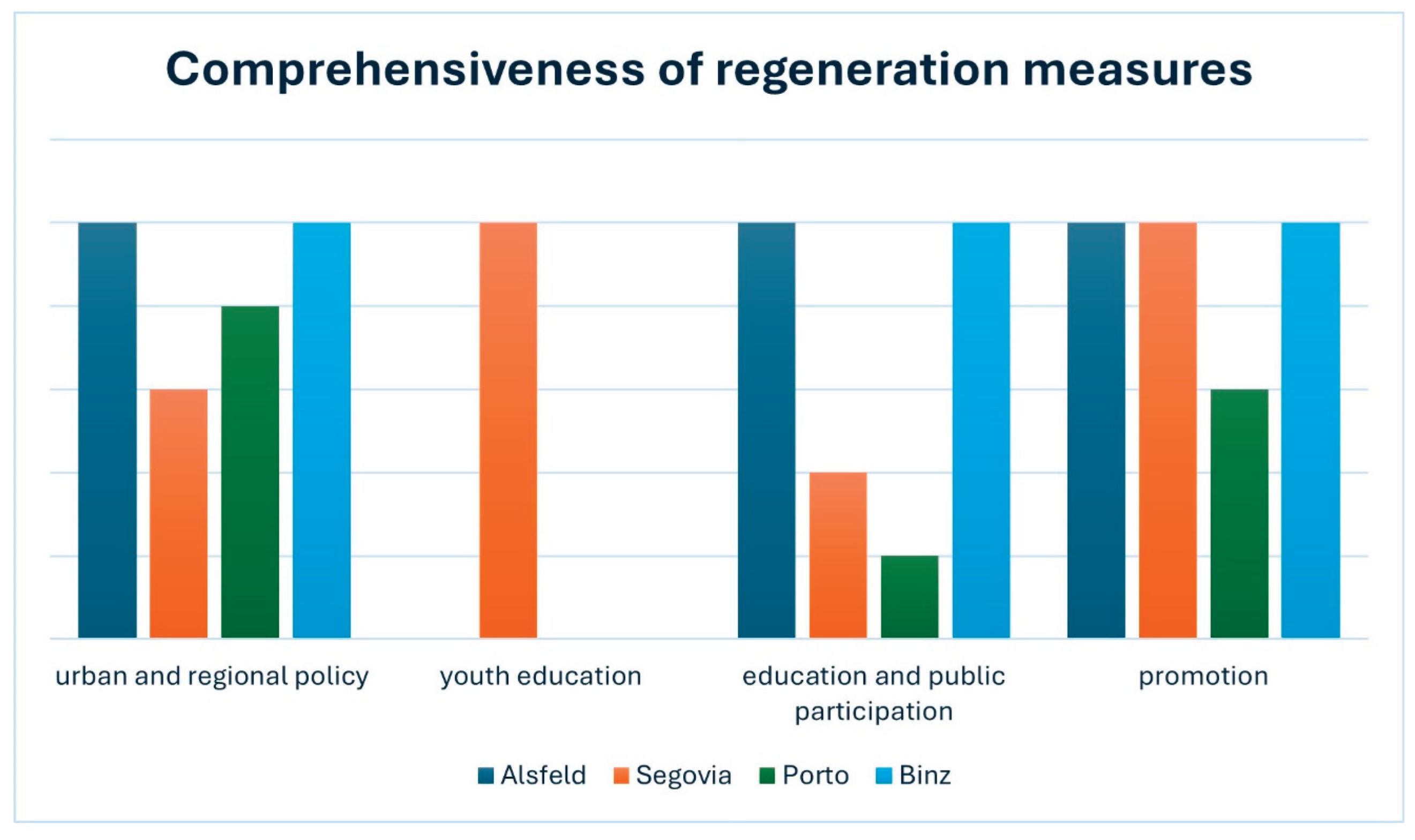

Comparative research has shown that despite the variety of activities undertaken in the spheres of education, urban and regional policy, public participation, they have everywhere been carried out quite extensively and covered different areas of life. The experiences of the studied centres, showing different approaches to revitalisation processes, indicate that any superficial actions, e.g. concerning only the renovation of building facades, do not produce lasting results. The research has shown that only balanced actions in the cultural, social and economic and architectural-urban fields, preceded by thorough, interdisciplinary research and public consultation, can produce a good and lasting effect, serving the city and its community for many generations. The need to involve members of the local community, who must be aware of and accept the measures taken, has also been demonstrated. This is very important especially when revitalising residential buildings, which are usually privately owned. In addition, public education is very important - showing ways of adapting tenement houses and flats to modern standards while preserving historic values, favourable proposals for financial solutions and comprehensive planning of the project within the entire historic area.

On the basis of the contextual analysis of the selected urban centres, it was shown that there is a relationship between the care for the tangible architectural cultural heritage in the form of traditional local residential architecture and the intangible heritage in the form of the cultivation of skills and professions associated with traditional architecture. Revitalisations of timber-framed buildings, sgraffito or laubzeg decoration were carried out by masters in their crafts. Unfortunately, it is only in Segovia that training of young students in the art of sgraffito takes place.

The nomothetic analysis made it possible to identify the most important reasons that led to the success of revitalisation activities in all analysed centres. Adequate municipal policies and high levels of activity in revitalisation activities came to the fore. In all centres, local authorities and organisations were actively involved, but these activities were not always fully thought through. Alsfeld can be cited as the best example, where after years of experience, a broad spectrum urban development concept was created. Binz is also a good example, where good legal solutions have prevented the destruction of the resort’s character and guided its development. National regulations are also of great importance. Here, the best example is Porto, where the process of revitalising tenements only started after the abolition of the law prohibiting landlords from raising rents and evicting non-paying tenants. Housing fees were so low that landlords were unable to maintain the buildings, which were falling into disrepair.

Also important are the activities of municipal authorities and local organisations to promote the cities, carried out in all the centres surveyed. These are mainly information on the architectural heritage with films, interactive city plans and suggestions for guided tours as in Alsfeld, for example. An interesting idea for the promotion of sgrafitto in Segovia, with the inclusion of new technologies, is the production of a barcode in this technique, to be placed on buildings, which, when scanned with a phone, conveys information about the building, for example. In Porto, the local authorities have paid a lot of attention to the creation of the city’s brand, helping with promotion. A summary of various examples of activities in the field of regeneration is shown in

Table 3.

On the basis of the analysis of the individual city studies, the comprehensiveness of revitalisation measures was assessed. In accordance with the categories in

Table 3, points were awarded for the various measures, which made it possible to estimate the comprehensiveness of the work, as shown in the chart below.

Figure 22.

Comprehensiveness of regeneration measures.

Figure 22.

Comprehensiveness of regeneration measures.

A final aspect highlighted is the specific activities that also influence the revitalisation process. It has been shown that the different needs of cities generate different factors influencing the revitalisation process. Therefore, it is very important to look at the individual conditions, needs and constraints of each revitalised city. Examples of specific activities carried out in the studied centres are shown in

Table 4

Examples of the revitalisation of historic areas are plentiful and no small number of research papers have been produced on the subject. They usually cover one or two centres. However, the specificity of the topic requires continuing research, showing different examples and discussing them. This greatly broadens the spectrum of measures and ideas that can be matched to individual cases and used as proven models.

The study was limited to four selected centres, which significantly limits its scope. However, even such a fragmented research work, allows comparisons to be made, highlights the importance of the topic and can contribute to the ongoing or yet to be planned revitalisation processes. Also important in the context of the studies carried out by various researchers is the emphasis on the architectural qualities of housing, which is most often overlooked in research or treated marginally. The identity of a city should be based on the unique character of the local culture, and it is precisely the residential buildings that are not only an architectural heritage, but also testify to the material culture of the places and its inhabitants. Therefore, further comparative research in this field is needed, culminating in a publication summarising the subject based on a much larger number of examples, from different continents.

4. Conclusions

The research has shown the very high value of historic, residential architecture which, together with the urban layout, is an important element of the architectural cultural heritage. The facades of the townhouses stretching along the streets of the towns and localities, through their peculiar features, form an urban landscape with great historical and monumental value. It is therefore worth protecting places where this type of architectural heritage has not been disturbed by incongruous and disfiguring building additions. It is also advisable to plan new buildings in such a way that they incorporate traditional elements well-transformed into the language of contemporary architecture alongside contemporary forms. Only then can the harmony of the urban landscape and the genius loci of the place be preserved. Despite the distinctiveness of the traditions and cultural values of cities in different regions, certain general principles in the field of monument protection recur. These were also demonstrated by the research carried out.

evitalisation programmes for historic areas consisting mainly of residential buildings should:

- include large-scale, interdisciplinary activities, often going beyond the protection of historic buildings alone

- include communication, economic and other solutions to the needs of the local community

- be based on broad public consultation, encouraging residents to take action

- be accepted by the local community and stakeholders

- create a willingness to act and a sense of pride in their local area

- provide good access to information about the programme and the opportunities it offers

- include favourable financing conditions for private property owners

- contain clear and concise terms for the conservation and regeneration project

The policy of local authorities in cooperation with organizations for the protection of historical monuments and conservation services should be consistent; clearly expressed in ordinances and resolutions; and harmonize with the ordinances of regional or state authorities. It is also advisable to consider which of the existing ordinances or laws are conducive to historic preservation; and which should be changed

Each city or town has different building traditions, a different degree of historic architecture preservation and different opportunities. Therefore, it is not possible to create a universal historic preservation programme. However, based on general principles and good models, it is easier to create your own local projects. It should be remembered that the awareness of tradition, of cultural roots is very important for people and helps them to survive in the unified, increasingly virtual, modern world. And yet the closest thing we have is residential architecture. Therefore, it is very important to conduct research showing its historic values, its potential for creating identity, landscape and the brand of a city or town. For this reason, it is also useful to look for townscape identifiers among this architectural group.

Author Contributions

D.B-K design of the work, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, execution of photos, have drafted the work. M.K. design of the work, have drafted the work or substantively revised it.

Funding

The research was partly funded by the Bydgoszcz University of Science and Technology research fund.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ information

D.B-K. DSc conservator and heritage expert, assistant professor at Bydgoszcz University of Science and Technology, Department of Architecture, research interests history of residential architecture, urban regeneration processes, urban landscape research. M.K. PhD architect, assistant professor at Bydgoszcz University of Science and Technology, Department of Architecture, research interests, urban regeneration, public participation in the revitalisation process.

References

- Włodarczyk M. The identity of architecture over time. Czas Tech. 108(4-A/2):461–5.

- Kalandides A. The problem with spatial identity: revising the ‘sense of place’. J Place Manag Dev. 2011;4(1):28–39.

- Dudzik-Deko P, Rzeźnik J. The Architectural Place Identity – an Authorial Proposal of a Measurement Indicator. Stud Miej. 2022;43:83–96.

- Mahgoub Y, Cavalagli N, Versaci A, Bougdah H, Serra-Permanyer M, editors. Cities’ Identity Through Architecture and Arts, ed. Yasser Mahgoub [Internet]. 1st ed. Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Public policy on city center revitalization based on the Town Centre Management concept. E- Mentor. 5(92):36–44.

- Casais B, Monteiro P. Residents’ involvement in city brand co-creation and their perceptions of city brand identity: a case study in Porto. Place Brand Public Dipl. 2019 Dec 1;15(4):229–37. [CrossRef]

- Dembicka - Niemiec A. Revitalization Actions as a Tool to Shape a Sustainable City (A Case Study of Opole Voivodeship, Poland). Stud Miej. (24):9–21.

- Jones C, Svejenova S. The Architecture of City Identities: A Multimodal Study of Barcelona and Boston. In: Höllerer MA, Daudigeos T, Jancsary D, editors. Multimodality, Meaning, and Institutions [Internet]. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2017 [cited 2024 Dec 3]. p. 203–34. (Research in the Sociology of Organizations; vol. 54B). [CrossRef]

- Rosado A, Reimão Costa M. The Contribution of Typological Studies to the Integrated Rehabilitation of Traditional Buildings: Heritage Enhancement of Urban Centres in Inner Alentejo, Portugal. Architecture. 2024 Jan 5;4(1):35–45. [CrossRef]

- Alavi SF, Tanaka T. Analyzing the Role of Identity Elements and Features of Housing in Historical and Modern Architecture in Shaping Architectural Identity: The Case of Herat City. Architecture. 2023 Sep 19;(3):548–77. [CrossRef]

- Der Fachwerk Triennale 22 Katalog. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutsche Fachwerkstädte e.V.; 2022.

- Beckmann EM, Sutthoff LJ, editors. Gebäude aus Fachwerk Konstruktion – Schäden – Instandsetzung Dokumentation zum 27. Kölner Gespräch zu Architektur und Denkmalpflege in Brauweiler, 12. November 2018 Mitteilungen aus dem LVR-Amt für Denkmalpflege im Rheinland [Internet]. 2019. LVR-Amt für Denkmalpflege im Rheinland; [cited 2024 Dec 4]. (Mitteilungen aus dem LVR-Amt für Denkmalpflege im Rheinland; vol. 34). Available from: https://denkmalpflege.lvr.de/media/denkmalpflege/publikationen/online_publikationen/Heft34_Fachwerk_230519_bf.pdf.

- Ruiz A. Fenómenos de difusión y asimilación del esgrafiado en la arquitectura mediaval, moderna y contenproánea. In: Chaves Martín MÁ, editor. Ciudad y artes visuales, Grupo de Investigación Arte. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid; 2016. p. 11–34. (Arquitectura y Comunicación en la Ciudad Contemporánea).

- Ruiz A. Esgrafiado: historia de un revestimiento mural. De la Antigüedad al Renacimiento. Segovia: Diputación Provincial de Segovia; 2020.

- Lozoya, J. de Contreras y Lopez de Ayal, Marques de J. La Casa Segoviana. Madrid: Hauser y Menet; 1921.

- Ruiz H. La ciudad de Segovia. Segovia: Excelentisimo Ayuntamiento De Segovia; 1986.

- Peñalosa y Contreras LF. Los esgrafiados segovianos. Segovia: la Cámara Oficiial de la Propiedad Urbana de la Provincia de Segovia; 1971.

- Puente Robles de la A. El esgrafiado en Segovia y provincia. Modelos y tipologías. Leon-Madrid: Libreria Anticuaria Camino de Santiago; 1990.

- Ruiz A. El Esgrafiado Segoviano. Segovia: Asociación Para El Desarrollo Rural De Segovia Sur; 2000.

- Alonso RR. UN NOVEDOSO ENFOQUE DEL ESGRAFIADO MUDÉJAR Y DE LA PINTURA “DE LO MORISCO” EN SEGOVIA. [cited 2024 Dec 3]; Available from: https://www.academia.edu/14658394/UN_NOVEDOSO_ENFOQUE_DEL_ESGRAFIADO_MUD%C3%89JAR_Y_DE_LA_PINTURA_DE_LO_MORISCO_EN_SEGOVIA.

- Ruiz A. El esgrafiado en los ámbitos islámico y mudéjar. De las relaciones entre grafito, inciso, yesería y esgrafiado, Discurso de inauguración del curso 2014-2015. Estud Segovianos Bol Real Acad Hist Arte San Quirce Asoc Inst Esp. 2015;LVII(114):19–71.

- Santos H, Valença P, Oliveira Fernandes F. UNESCO’s Historic Centre of Porto: Rehabilitation and Sustainability. Energy Procedia. 2017;(133):86–94. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira J, Fernandes Póvoas R. The Importance of Design in Porto’s Ancient Buildings Interventions. Characterization of the Pathological Context through a Constructive Model. In 2011. p. 1–8. Available from: https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/handle/10216/54833.

- The investigation of energy efficiency measures in the traditional buildings in Oporto World Heritage Site. 2014; p. 128–31.

- Arlet J. Half-Timbered Resort Architecture from the Turn of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries in Fore Pomerania and Western Pomerania: In Search of a Style. Przestrz Forma. 2022 Nov 16;(51):241–62. [CrossRef]

- Bręczewska-Kulesza D, Wieloch G. Use of wood in the Baltic courses architecture on the example of Binz in Ruges. Ann WULS - SGGW For Wood Technol. 2019;107:104–14. [CrossRef]

- Städtebaulicher Denkmalschutz Denkmalgebiet Alsfeld Altstadtsanierung 2.0 Bericht, Kassel 26.06.2018 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 2]. Available from: https://static.werdenktwas.de/domain/149/fs/download/ISEKAlsfeldBericht.pdf.

- Jäkel H. Kleine illustrierte Geschichte der Stadt Alsfeld. Alsfeld: Geschichts- u. Museumsverein; 1997.

- Nicolai M. Alsfelder Stadtgeschichte, Jahrestage. Alsfeld: Geschichts- u. Museumsverein; 2016.

- Jäkel H. Alsfeld. Europäische Modellstadt. Historische Altstadt von gestern, Denkmalpflege und Sanierung heute. Lebendige Stadtmitte von morgen. Ein Beitrag zum Europäischen Denkmalschutzjahr 1975. Alsfeld: Geschichts- und Museumsverein Alsfeld; 1975.

- Stadt Alsfeld. Städtebaulicher Denkmalschutz Denkmalgebiet Altstadt [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.projektstadt.de/projekt/stadt-alsfeld.

- Altstadtsanierung 2.0 Lebendige Zentren. Förderung: Private Sanierungsmaßnahmen [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 3]. Available from: https://alsfeld-altstadtsanierung.de/page/foerderung.

- A.M. Esgrafiados, la piel de Segovia. El Día de Segovia [Internet]. 2021 domingo, de abril de; Available from: https://www.eldiasegovia.es/noticia/z946a96c4-e8d8-684c-f53756ce0bf739bc/202104/esgrafiados-la-piel-de-segovia.

- Alcántara de F. El Imparcíal. Galas Arquit. 1909.

- Barrio Gozalo M, and others. Historia de Segovia. Segovia: Caja de Ahorros y Monte de Piedad de Segovia, Obra cultural D. L.; 1987.

- Chaves Martin MA. Intervenciones en el patrimonio monumental de Segovia durante el siglo XIX. Asoc Cult Plaza Mayor Segovia. 2006;(1):1–20.

- PEAHIS Plan Especial de las áreas históricas de Segovia [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 2]. Available from: http://peahis.segovia.es/doc06.html.

- CFGM en Revestimientos Murales [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 2]. Available from: https://easdsegovia.com/estudios/revestimientos-murales/.

- Provincial de Educación de Segovia. Finalizan las I Jornadas de Esgrafiado y Diseño en colaboración con el IES Andrés Laguna [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 3]. Available from: https://easdsegovia.com/finalizan-las-i-jornadas-de-esgrafiado-y-diseno-en-colaboracion-con-el-ies-andres-laguna/.

- Diseño y elaboración de un esgrafiado en el interior de la Dirección Provincial de Educación de Segovia [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 1]. Available from: https://easdsegovia.com/category/murales/.

- Quirce osé A. Un moderno esgrafiado segoviano homenajea a San Juan de la Cruz. Tribuna Segovia [Internet]. 2024 Mar 23 [cited 2024 Dec 1]; Available from: https://www.tribunasegovia.com/noticias/356398/un-moderno-esgrafiado-segoviano-homenajea-a-san-juan-de-la-cruz.

- Segovia, escenario de la presentación del esgrafiado del siglo XXI, que aúna tradición y nuevas tecnologías [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 4]. Available from: https://segovia.es/actualidad/noticias/segovia-escenario-de-la-presentacion-del-esgrafiado-del-siglo-xxi-que-auna.

- Lorenz T. How a law change is helping Porto discover its revival instinct. Financial Times [Internet]. 2015 Jul 23; Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/a54481f0-2b00-11e5-acfb-cbd2e1c81cca.

- Finke B, Pipia B. Landhäuser & Villen am Meer - Rügen und Hiddensee. CULTURCON Medien; 2009. (ArchitekTOUR - Mecklenburg-Vorpommern).

- Aktion ROse. In Wikipedia; Available from: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aktion_Rose.

- Binz. In: Wikipedia [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 4]. Available from: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binz#Fischer-_und_Bauerndorf.

- The escape tower in BINZ. Rugebinz.de [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ruegenbinz.de/en/He-rescue-storm-in-binz/.

- Kassner, K. Verordnung über den Denkmalbereich Hauptstraße I-Strandpromende Putbuser Straße - Bahnhofstraße im Ostseebad Binz [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2024 Sep 10]. Available from: https://www.lk-vr.de/media/custom/3034_795_1.PDF?1560416845.

| 1 |

The turbulent history of Spain and Segovia, and the economic crises that haunted the city from the 17th century onwards, caused periods of abandonment of sgraffito. But after they were resolved, it became a very popular technique again. More on the history of Segovia [ 16]. |

| 2 |

More on the history of Segovia among other things [ 16, 35]. |

| 3 |

More on the revitalisation of Porto’s historic centre [ 22]. |

Figure 1.

Alsfeld, Marktplatz - timber-framed townhouses.

Figure 1.

Alsfeld, Marktplatz - timber-framed townhouses.

Figure 2.

Alsfeld, Am Kreuz 5 – house built in 1623 by Johannes Oppels with inscription and rope frieze.

Figure 2.

Alsfeld, Am Kreuz 5 – house built in 1623 by Johannes Oppels with inscription and rope frieze.

Figure 3.

Alsfeld, Markt Platz 6 / Meinert Gasse – house built in 1609 by Jost Stumpf., corner with sculptural decoration.

Figure 3.

Alsfeld, Markt Platz 6 / Meinert Gasse – house built in 1609 by Jost Stumpf., corner with sculptural decoration.

Figure 4.

Alsfeld, Marktplatz 6 / Meinert Gasse – house built in 1609 by Jost Stumpf., decorative friezes and a fragment of an inscription.

Figure 4.

Alsfeld, Marktplatz 6 / Meinert Gasse – house built in 1609 by Jost Stumpf., decorative friezes and a fragment of an inscription.

Figure 5.

Alsfeld, Obere Fulder Gasse - timber-framed townhouses.

Figure 5.

Alsfeld, Obere Fulder Gasse - timber-framed townhouses.

Figure 6.

Segovia, buildings covered with sgraffito decoration on the 2nd and 3rd floors - stylised floral motifs and wheel motif with cinder pieces.

Figure 6.

Segovia, buildings covered with sgraffito decoration on the 2nd and 3rd floors - stylised floral motifs and wheel motif with cinder pieces.

Figure 7.

Segovia, Palacio del Conde Alpuente, Plaza Platero Oquendo 3, example of sgrafitto on a building erected in the 15th century.

Figure 7.

Segovia, Palacio del Conde Alpuente, Plaza Platero Oquendo 3, example of sgrafitto on a building erected in the 15th century.

Figure 8.

Segovia, a tenement with sgraffito decoration different on each storey and with bands of border.

Figure 8.

Segovia, a tenement with sgraffito decoration different on each storey and with bands of border.

Figure 9.

Segovia, an example of sgraffito decoration with floral and geometrical motifs.

Figure 9.

Segovia, an example of sgraffito decoration with floral and geometrical motifs.

Figure 10.

Segovia, an example of sgraffito decoration with simple with wheel motif.

Figure 10.

Segovia, an example of sgraffito decoration with simple with wheel motif.

Figure 11.

Segovia, Plaza del Corpus 1 i Calle Isabela Catolica 7, houses with sgrafitto decoration with a shell motif, made during renovations in the 20th century.

Figure 11.

Segovia, Plaza del Corpus 1 i Calle Isabela Catolica 7, houses with sgrafitto decoration with a shell motif, made during renovations in the 20th century.

Figure 12.

Porto, townhouses on Praça de Almeida Garrett.

Figure 12.

Porto, townhouses on Praça de Almeida Garrett.

Figure 13.

Porto, example of a facade with French windows and balconies from the area of the historic center of Porto.

Figure 13.

Porto, example of a facade with French windows and balconies from the area of the historic center of Porto.

Figure 14.

Porto, an example of sliding windows solutions from the area of the historic center of Porto.

Figure 14.

Porto, an example of sliding windows solutions from the area of the historic center of Porto.

Figure 16.

(

a,

b) Comparison of the facade of a tenement house with original windows (

Figure 16a) and computer simulation with contemporary windows on the top floor (

Figure 16b).

Figure 16.

(

a,

b) Comparison of the facade of a tenement house with original windows (

Figure 16a) and computer simulation with contemporary windows on the top floor (

Figure 16b).

Figure 17.

Binz, Strandpromenade with guest houses and villas.

Figure 17.

Binz, Strandpromenade with guest houses and villas.

Figure 18.

(a,b) Binz, examples of fretwork decorations.

Figure 18.

(a,b) Binz, examples of fretwork decorations.

Figure 19.

Binz Margaretenstrasse 17, example of a guesthouse with uncovered verandas.

Figure 19.

Binz Margaretenstrasse 17, example of a guesthouse with uncovered verandas.

Figure 20.

Binz, Schillerstrasse 9, example of a guesthouse with built-up verandas.

Figure 20.

Binz, Schillerstrasse 9, example of a guesthouse with built-up verandas.

Table 1.

The most important activities in the field of preservation of housing historic substance.

Table 1.

The most important activities in the field of preservation of housing historic substance.

| |

Alsfeld |

Segovia |

Porto |

Binz |

| history of monuments preservation |

late 19th century

1902 - Protection of Monuments Act

1975 European Model City for the Preservation of Historical Monuments |

mid-19th century tidying up of facades - increased use of sgraffito |

1996 - UNESCO

2001 National Monument |

Revitalisation after German reunification |

Table 2.

Factors influencing the cityscape.

Table 2.

Factors influencing the cityscape.

| Elements affecting the townscape |

Alsfeld |

Segovia |

Porto |

Binz |

| urban landscape identifiers |

dominance

fachwerk buildings, approximate townhouse dimensions |

predominance facades with sgraffito decoration in geometric and fanciful forms |

predominance townhouse with large glazed facades

window woodwork with multiple divisions and carved decoration |

dominance

houses with wooden verandas

laubzeg decoration

similar building dimensions

white façade colour |

| elements to distinguish individual objects |

colouring of wooden parts of buildings, woodcarving decorations, inscriptions on the entablature |

variation in patterns and thickness of plaster layers in sgraffito decoration, forms of facade covering, colours |

varied forms of window joinery divisions with fancy designs, varied carving decoration |

use of various architectural elements

varied motifs of laubzeg decoration |

Table 3.

Analysis of activities in the field of revitalisation.

Table 3.

Analysis of activities in the field of revitalisation.

| Category of revitalisation measures |

Alsfeld |

Segovia |

Porto |

Binz |

| urban and regional policy |

municipal statutes and development plans including monuments

2016 - new, very broad revitalisation programme |

building inventory

promotion of sgraffito |

municipal plans and ordinances, establishment of regeneration management institutions and associations

e.g. 1974 CRUARB |

return of property to former owners after German reunification

County Administrator’s Decree on Monuments Binz 2002 |

| youth education |

- |

Teaching techniques and wall procedures

Escuela de Artes Aplicadas y Oficios Artísticon de Segovia |

- |

- |

| education and public participation |

strong participation of the local community

education of tenement owners on renovation |

organisation of conferences and events promoting the sgrafitto technique |

participatory activities too limited according to residents |

financial support

close supervision of conservation |

| promotion |

city website - information about regeneration, good models, maps with descriptions of the most interesting monuments, films |